Abstract

Purpose

Pudendal neuralgia (PN) is a painful and disabling condition, which reduces the quality of life as well. Pudendal nerve infiltrations are essential for the diagnosis and the management of PN. The purpose of this study was to compare the effectiveness of finger-guided transvaginal pudendal nerve infiltration (TV-PNI) technique and the ultrasound-guided transgluteal pudendal nerve infiltration (TG-PNI) technique.

Methods

Forty patients who underwent PNI for the diagnosis of PN were evaluated. Thirty-five of these 40 patients, who were diagnosed as PN, underwent a total of 70 further unilateral PNI. All the patients underwent PNI for twice after the first diagnostic PNI, 1 week apart.

Results

In the ultrasound (US)-guided TG-PNI group, the success rate was 68.8% (11 of 16) in both “pain in the sitting position” and “pain in the region from the anus to the clitoris.” The success rate of blocks in the US-guided TG-PNI group was 75% (12 of 16) in terms of pain during/after intercourse. In the finger-guided TV-PNI group, the success rate was 84.2% in both “pain in the sitting position” and “pain in the region from the anus to the clitoris.” The success rate of blocks in the fingerguided TV-PNI group was 89.5% (17 of 19) in terms of pain during/after intercourse. There was no statistically significant difference in the success rate of the 3 assessed conditions between the 2 groups (P>0.05).

Conclusions

The TV-PNI may be an alternative to US-guidance technique as a safe, simple, effective approach in pudendal nerve blocks.

Keywords: Anesthesia, obstetrical; Ultrasonography, interventional; Neuralgia; Nerve block; Pelvic pain; Pudendal nerve

INTRODUCTION

Pudendal neuralgia (PN) is a painful neuropathic condition for which current prevalence is unknown due to often going underrecognized by gynecologists. PN typically presents as unilateral severe sharp and burning pain, numbness, or paranesthesia on the anatomic pathways of the pudendal nerve [1]. The most common causes for PN include pudendal nerve injury during vaginal procedures, stretching and compression of the pudendal nerve during vaginal delivery, and prolonged sitting position [2,3].

As in many neuropathic syndromes, there is currently no gold standard diagnostic test for assessing PN [4]. In 2006, the Nantes criteria were described by a multidisciplinary working party to describe the clinical diagnostic criteria, and a standard approach was created for PN diagnosis. According to the Nantes criteria, patients should fulfil all 5 essential criteria without meeting any of the exclusion criteria. The 5 essential diagnostic criteria were defined as, 1: pain in the anatomic territory of the pudendal nerve, 2: that is worsened by sitting, 3: the patient is not woken at night by the pain, 4: no objective sensory loss on clinical examination, and 5: positive anesthetic pudendal nerve block [5].

Pudendal nerve infiltration (PNI), which was defined as an essential step, is performed for diagnostic purposes and as an important treatment modality in patients with PN [6-11]. This approach aims for long-term relief of pain, as in all forms of nerve entrapment syndromes, by treating a possible inflammatory component, it also provides neuroprotection to the central nervous system and reduces spontaneous ectopic activity of the affected nerve [12,13].

Image-guided or finger-guided PNIs can be performed according to the experience of the physician, adequate equipment presence, and patient choice. Over the past 20 years, studies have described the PNI techniques [14-20], but a limited number of studies have compared the efficacy of image-guided PNI techniques [21]. To the best of our knowledge, there are no studies comparing the finger-guided transvaginal PNI (TVPNI) and ultrasound (US)-guided transgluteal PNI (TG-PNI) for the evaluation of pain relief in patients with PN. We hypothesized that the finger-guided TV technique is effective as US-guided TG-PNI when performed to relieve pain in patients with PN. The primary outcome of the present study was to evaluate the changes of mean visual analogue scale (VAS) scores based on the mean daily maximum pain intensity score during the week before day 0 (D0), day 7 (D7), day 21 (D21), and day 180 (D180). Secondly, the postblock complication rate was evaluated in overall blocks. Secondary outcome included the comparison of the success rates of both 2 techniques (from D0 to D180).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

We confirm that the present study runs in concordance with the Declaration of Helsinki principles and the guidelines of the International Committee of Medical Journal. The study was approved by the ethics committee of Kocaeli University Hospital (registration number KÜ GOKAEK-2017/14.31 2017/294). The study was registered to www.ClinicalTrials.gov (Clinical Trial registration number: NCT03973983, date of trial registration: June 2, 2019).

Study Design and Patient Selection

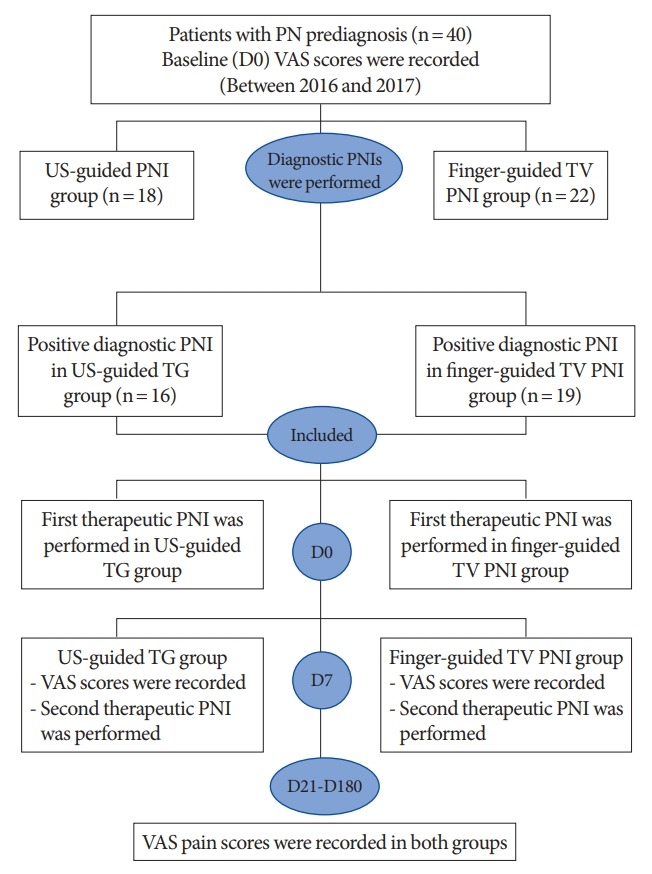

This retrospective study was conducted with self-referred patients who underwent PNIs with for a therapeutic purpose in University of Health Sciences, Derince Training and Research Hospital between November 2016 and September 2017. The patients in the cohort were screened for possible inclusion in the study using inclusion and exclusion criteria. A total of 40 patients received a prediagnosis (according to the first 4 Nantes criteria) of unilateral PN by a senior neuropelveologist (AK). Informed consent was obtained from each patient before the treatment. Thirty-five of 40 patients (87.5%) had a 50% reduction in pain intensity while in the sitting position after the diagnostic PNI and fulfilled the 5 essential Nantes criteria. Following the first diagnosis of PN, the patients underwent PNIs for twice, 1 week apart, whether transvaginal or transgluteal according to the physician’s decision or preference of the patient. We detected that 19 patients underwent finger-guided TV-PNI and 16 patients received US-guided TG-PNI. All patients’ data were retrieved from both the hospital database and the patients’ International Pelvic Pain Society assessment forms (Fig. 1). In diagnostic PNI negativity, virgin and/or sexual inactive patients were excluded from the study.

Fig. 1.

Flowchart summarizing retrieved. PN, pudendal neuralgia; VAS, visual analogue scale; US, ultrasound; TV, transvaginal; PNI, pudendal nerve infiltration; TG, transgluteal; D0, baseline; D7, 1 week after the first block; D21, 3 weeks after the second block; D180, 6th month after the blocks completed.

Data Collection

The following parameters were analyzed in all patients: age, body mass index (BMI), duration of pain, past obstetric-gynecologic history, side of pain. The pain intensity was assessed through face-to-face interviews 4 times: before the treatment, at 1 week after the initial therapeutic block, at 3 weeks after the second therapeutic block, and 6 months after the treatment was completed. Pain intensity was evaluated based on 3 parameters: 1: pain in the region from the anus to the clitoris, 2: pain while sitting, 3: pain during/after intercourse. Postblock complications were evaluated: ecchymoses at the injection side, temporary foot drop, and numbness along the sciatic nerve distribution.

Pain intensity was evaluated using a 10-cm VAS system. Patients were asked to rate their pain from 0=no pain to 10=worst pain [22]. The PNIs were classified into 2 groups as successful and unsuccessful. Clinical success rates of the pudendal nerve blocks were analyzed individually for TG-PNI and TV-PNI based on 3 parameters previously mentioned (clinical success rate for the pain in the region from the anus to the clitoris, clinical success rate for pain while sitting, clinical success rate for pain during/after intercourse). Improvement of more than 50% of the initial pain at 6 months after the PNIs completed was considered as clinical success (D0 to D180) [11].

Description of the PNI Techniques

Before the PNI procedures, standard 3-lead electrocardiogram, pulse oximetry, and noninvasive blood pressure monitors were applied, and venous access was established. All PNIs were conducted in the operating room without any anesthesia. In both groups, the patients received the same dose of a mixture of local anesthetic (8 mL of 0.5% bupivacaine and 2 mL of 8 mg dexamethasone) using a 20-gauge, 12-cm needle (Uniplex, Pajunk® GmbH, Geisingen, Germany). The function of a positive PNI was assessed 30 minutes after the block using sensory tests with both pinprick and alcohol swab tests.

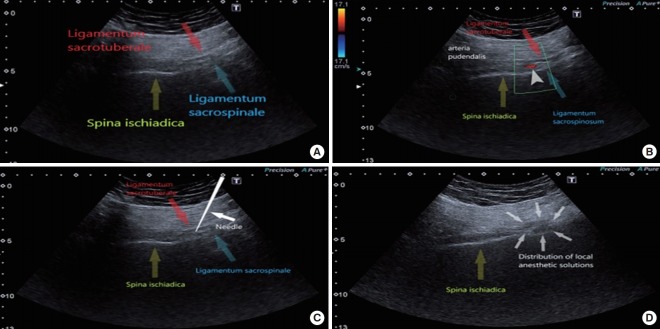

US-Guided Transgluteal PNI Technique

The patients were placed in the prone position. The skin was cleaned with an aseptic technique using a 10% povidone-iodine solution and a transparent plastic sheath was used for sterile probe preparation. Scanning was performed under real-time US (HD 15 Philips, Bothell, WA, USA) with a 2- to 5-MHz curved array transducer. Scanning was performed in transverse planes in order to visualize the ischium forming the lateral border of the sciatic notch. The ischium appeared as a gradually lengthening hyperechoic line by moving the US probe in a cephalad-caudal direction and it was widest at the ischial spine level. The ischial spine was also verified with visualization of the pudendal artery, and the sacrospinous and sacrotuberous ligaments. The sacrospinous ligament appeared as a hyperechoic line in continuity with the ischial spine, with lower echogenicity than bone. Similarly, the sacrotuberous ligament was observed on US image as a light hyperechoic line deep to the gluteus maximus muscle and appeared parallel and superior to the sacrospinous ligament (Fig. 2A). At this level, color Doppler was used to localize the internal pudendal artery pulsations in close proximity to the ischial spine (Fig. 2B). Localization of the pudendal nerve was targeted in the plane between these 2 ligaments. Under US guidance, the needle was inserted from the medial aspect of the probe and advanced in line with the US probe to the medial aspect of the internal pudendal artery (Fig. 2C). When the needle passed through the sacrotuberous ligament, a ‘click’ was usually felt and a small volume (1–2 mL) of dextrose 5% solution was administered to recognize the plane between the sacrotuberous and sacrospinous ligaments, and to accentuate the pudendal nerve appearance; the solution appeared as a hypoechoic collection. Afterwards, a mixture of local anesthetic was administered, and the sufficiency of local anesthetic spread around the nerve during injection was reassessed with US (Fig. 2D).

Fig. 2.

(A) Anatomical landmarks of the pudendal nerve block on the ultrasound (US) image (spina ischiadica, ligamentum sacrospinale, ligamentum sacrotuberale). The sacrospinous and sacrotuberous ligaments are seen as hyperechoic specular reflectors. (B) Anatomical landmarks of the pudendal nerve block on the US image (spina ischiadica, ligamentum sacrospinale, ligamentum sacrotuberale). Figure presents internal pudendal artery on the color Doppler image. (C) Anatomical landmarks of the pudendal nerve block on the US image (spina ischiadica, ligamentum sacrospinale, ligamentum sacrotuberale). Ultrasound image shows pudendal nerve block at the level of ischial spine. (D) Anatomical landmarks of the pudendal nerve block on the US image (spina ischiadica, ligamentum sacrospinale, ligamentum sacrotuberale). Ultrasound image shows the anaesthetic agent spreading between the sacrospinous and sacrotuberous ligaments.

Finger-Guided Transvaginal PNI Technique

Patients were placed in the supine lithotomy position and the vaginal asepsis was provided using a 10% povidone-iodine solution. The sacrospinous ligament was palpated by the index and middle fingers for guiding the needle through the vagina. The needle was advanced over the same route with the other hand while still palpating the sacrospinous ligament (Fig. 3). The needle was directed 10 mm posterior and medial to the ischial spine at a depth of 10 mm. The mixture of local anesthetic was applied following the negative aspiration test, which confirmed the absence of iatrogenic damage of the pudendal vessels.

Fig. 3.

The figure shows technique of the finger-guided transvaginal pudendal nerve infiltration. The patient was placed in the lithotomy position, and the physician places an index and middle fingers into the vagina and place the tips of these fingers on the ischial spine. Then the needle was advanced through the vaginal mucosa via the finger guide toward the sacrospinous ligament. The needle was directed 10 mm posterior and medial to the ischial spine at a depth of 10 mm.

Statistical Analysis

For statistical analysis, the chi-square test was used to compare categorical variables in the finger-guided-transvaginal and USguided PNI groups, and the Mann-Whitney U-test was used to compare the means in the same groups. Repeated-measures 2-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) within groups test was performed to analyze the change over time in VAS score measurements, which was repeated 4 times at different periods for each pain parameter (pain while sitting, pain in the region from the anus to the clitoris, and pain during/after intercourse) in the 2 groups. All analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics ver. 20.0 (IBM Co., Armonk, NY, USA). Significance testing was 2-sided at an α of 0.05.

A power analysis using the G power computer program indicated that the power of the study was 0.95 with a total sample of 35, alpha at 0.05, and medium effects using repeated-measures ANOVA within factors [23].

RESULTS

A total of 35 patients underwent unilateral PNI with a total of 70 injections; 16 patients underwent US-guided PNI, and 19 underwent finger-guided transvaginal PNI.

Table 1 shows the detailed patient characteristics, obstetric history, VAS scores of the diagnostic PNI, and pain characteristics. No significant differences were observed between the patients in the 2 groups in terms of patient age, BMI, parity, type of delivery, and duration of pain and side of pain. The mean duration of pain was 56.4 weeks in the US-guided TG-PNI group and 61.5 weeks in the finger-guided TV-PNI group (P=0.257). In both groups, all patients had pain relief while in the sitting position 30 minutes after the diagnostic PNI, and the mean VAS pain scores were 3.1±2.0 and 3.3±1.7, respectively (P=0.935).

Table 1.

Comparison of demographic and clinical characteristics of the patients between the 2 groupsa)

| Group | Block procedure | Number | Mean± SD | No. (%) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (yr) | US-guided TG | 16 | 37.5 ± 6.8 | - | 0.924 |

| Finger-guided TV | 19 | 37.2 ± 13.5 | - | ||

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | US-guided TG | 16 | 27.8 ± 4.3 | - | 0.448 |

| Finger-guided TV | 19 | 25.5 ± 5.3 | - | ||

| Parity | US-guided TG | 16 | 2.3 ± 1.1 | - | 0.893 |

| Finger-guided TV | 19 | 2.1 ± 1.0 | - | ||

| Duration of pain start (mo) | US-guided TG | 16 | 56.4 ± 12.1 | - | 0.257 |

| Finger-guided TV | 19 | 61.5 ± 26.0 | - | ||

| VAS score of the diagnostic PNI | US-guided TG | 16 | 3.1 ± 2.0 | - | 0.935 |

| Finger-guided TV | 19 | 3.3 ± 1.7 | - | ||

| History of vaginal delivery | US-guided TG | 16 | - | 10 (62.5) | 0.315 |

| Finger-guided TV | 19 | - | 8 (42.1) | ||

| Right-sided pain | US-guided TG | 16 | - | 8 (50.0) | |

| Finger-guided TV | 19 | - | 10 (52.6) | ||

| Left-sided pain | US-guided TG | 16 | - | - | |

| Finger-guided TV | 19 | - | - |

SD, standard deviation; US, ultrasound; TG, transgluteal; TV, transvaginal; VAS, visual analogue scale; PNI, pudendal nerve infiltration.

P-values are for baseline differences between the 2 groups at the 0.05 significance level.

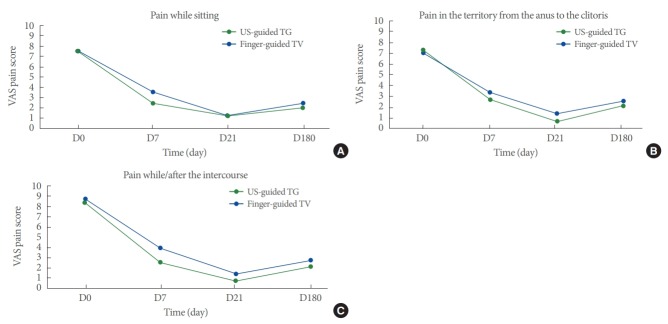

Table 2 shows the change in mean VAS pain scores while sitting, in the region from the anus to the clitoris, and during/after intercourse over time. Although the change in mean VAS scores over time was greater in the finger-guided TV-PNI group than in the US-guided TG-PNI group, the difference was not statistically significant. The mean VAS pain scores in all 3 parameters (while sitting, in the region from the anus to the clitoris, and during/after intercourse) decreased significantly in both groups with time (P<0.001 for all). The difference in VAS scores between baseline and endpoint was found to be statistically significant in all 3 parameters in both block groups (Fig. 4A-C).

Table 2.

The change in mean VAS scores of the pain while sitting, in the territory from anus to the clitoris and while/after the intercourse over time in 2 block groupsa)

| Variability of pain according to situation and time | US-guided TG |

Finger-guided TV |

F (P-value)b) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean±SD | P-value | Mean±SD | P-value | ANOVA within groups | ANOVA between groups | |

| VAS score of the pain while sitting | ||||||

| Baseline (D0) | 7.44 ± 1.09 | 7.53 ± 1.02 | 112.19 (0.000) | 0.76 (0.390) | ||

| 1 Week after first block (D7) | 3.56 ± 2.07 | 2.47 ± 2.09 | ||||

| 3 Weeks after second block (D21) | 1.19 ± 2.04 | 1.26 ± 1.3 | ||||

| 6th month after the blocks completed (D180) | 2.44 ± 2.19 | 2 ± 1.89 | ||||

| Change from baseline to endpoint (D0–D180) | 5.00 ± 2.33 | 5.52 ± 2.2 | ||||

| 95% CI of mean change | 3.75 ± -6.24 | 0.000 | 4.46 ± -6.58 | 0.000 | ||

| VAS score of the pain in the territory from the anus to the clitoris | ||||||

| Baseline (D0) | 7.06 ± 1.91 | 7.32 ± 2.31 | 74.38 (0.000) | 0.67 (0.421) | ||

| 1 Week after first block (D7) | 3.38 ± 2.09 | 2.68 ± 2.49 | ||||

| 3 Weeks after second block (D21) | 1.44 ± 2.16 | 0.74 ± 0.93 | ||||

| 6th month after the blocks completed (D180) | 2.56 ± 2.45 | 2.16 ± 2.04 | ||||

| Change from baseline to endpoint (D0–D180) | 4.50 ± 3.23 | 5.16 ± 2.54 | ||||

| 95% CI of mean change | 2.78 ± -6.22 | 0.000 | 3.93 ± -6.38 | 0.000 | ||

| VAS score of the pain while/after the intercourse | ||||||

| Baseline (D0) | 8.75 ± 1.81 | 8.42 ± 1.61 | 111.99 (0.000) | 2.63 (0.115) | ||

| 1 Week after first block (D7) | 3.94 ± 2.59 | 2.53 ± 2.5 | ||||

| 3 Weeks after second block (D21) | 1.38 ± 2.19 | 0.74 ± 0.99 | ||||

| 6th month after the blocks completed (D180) | 2.75 ± 2.6 | 2.11 ± 2.16 | ||||

| Change from baseline to endpoint (D0–D180) | 6.00 ± 2.90 | 6.32 ± 2.47 | ||||

| 95% CI of mean change | 4.46 ± -7.54 | 0.000 | 5.12 ± -7.5 | 0.000 | ||

VAS, visual analogue scale; US, ultrasound; TG, transgluteal; TV, transvaginal; SD, standard deviation; CI, confidence interval.

Student t -test. Significance testing was 2-sided at an α of 0.05.

Repeated-measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) (2-way) test: A power analysis using the G power computer program indicated that the power of this study is 0.95 with a total sample of 35, alpha at 0.05 and medium effects using repeated-measures of ANOVA within factors.

Fig. 4.

(A) The mean change of VAS scores from baseline to endpoint of 2 groups for pain while sitting position. Horizontal axis shows VAS score, vertical axis shows overtime. (B) The mean change of VAS scores from baseline to endpoint of 2 groups for the pain in the territory from anus to the clitoris. Horizontal axis shows VAS score, vertical axis shows overtime. (C) The mean change of VAS scores from baseline to endpoint of 2 groups for pain while/after the intercourse. The x-axis shows overtime and y-axis shows VAS score. D0, baseline; D7, 1 week after the first block; D21, 3 weeks after the second block; D180, 6th month after the blocks completed.

The clinical success rates (greater than 50% reduction of pain) of pudendal nerve blocks for pain in the territory from the anus to the clitoris, for pain with sitting, and for pain while/after the intercourse at the 6th month after the blocks were completed (D180) is shown in Table 3. In the US-guided TG-PNI group, the success rate was 68.5% (11 of 16) in both “pain in the sitting position” and “pain in the region from the anus to the clitoris.” The success rate of blocks in the US-guided TG-PNI group was 75% (12 of 16) in terms of pain during/after intercourse. In the finger-guided TV-PNI group, the success rate was 84.2% in both “pain in the sitting position” and “pain in the region from the anus to the clitoris.” The success rate of blocks in the fingerguided TV-PNI group was 89.5% (17 of 19) in terms of pain during/after intercourse. The global assessment of success rates of all pudendal nerve blocks (TV-PNI+TG-PNI) was 77.1% (27 of 35) in both “pain in the sitting position” and “pain in the region from the anus to the clitoris.” Also, the success rate of all pudendal nerve blocks (TV-PNI+TG-PNI) was 82.9% (28 of 35) in terms of pain during/after intercourse. There was no statistically significant difference between the TV-PNI and TGPNI groups in the success rates of blocks in terms of pain in the region from the anus to the clitoris, pain in the sitting position, and pain during/after intercourse (P>0.05 for all).

Table 3.

Clinical success rate at 6th month after the blocks completed (D180)

| Variable | US-guided transgluteal | Finger-guided transvaginal | Global assessment | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pain with sitting | 0.42 | |||

| ≤ 50% | 5 (31.3) | 3 (15.8) | 8 (22.9) | |

| > 50% | 11 (68.8) | 16 (84.2) | 27 (77.1) | |

| Pain in the territory from the anus to the clitoris | 0.42 | |||

| ≤ 50% | 5 (31.3) | 3 (15.8) | 8 (22.9) | |

| > 50% | 11 (68.8) | 16 (84.2) | 27 (77.1) | |

| Pain while/after the intercourse | 0.38 | |||

| ≤ 50% | 4 (25.0) | 2 (10.5) | 6 (17.1) | |

| > 50% | 12 (75.0) | 17 (89.5) | 29 (82.9) |

Values are presented as number (%).

US, ultrasound.

Temporary foot drop and numbness along the sciatic nerve distribution was reported in 8 blocks (8 of 70) as a temporary adverse effect following PNI. Five occurred after US-guided TG blocks and 3 after finger-guided transvaginal blocks. None of the patients in either group had adverse effects of injections such as ecchymosis and intravascular uptake of local anesthetics.

DISCUSSION

The main finding of this study was the US-guided TG-PNI technique was not superior to the finger-guided TV-PNI in terms of clinical success. These 2 techniques were also similar with regards to PNI related complications.

As in any of neuropathic pain, pharmacologic agents (nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medications, gabapentin, pregabalin, tricyclic antidepressants, and muscle relaxants) and physical therapy may be beneficial as a curative option. When these treatment modalities fail, PNI should be considered for providing diagnostic information as well as pain relief as a minimally invasive, nonsurgical therapeutic option [24]. The pudendal nerve is situated in the deepest area in the pelvis and it makes the PNI technically difficult if transperineal or transgluteal approaches are preferred. For this reason, it usually requires imaging guidance to target the injection site such as US [14,25], computed tomography (CT) [26,27], fluoroscopy [21,28], and magnetic resonance [15].

US-guided TG-PNI has been described to reach the pudendal nerve in the plane between the sacrotuberous and sacrospinous ligaments. This technique has many advantages such as visualization of the substantial structures (pudendal artery and the sciatic nerve) without radiation exposure it enables realtime images [16]. However, finger-guided TV-PNI should be kept in mind as a PNI option with the advantages of familiarity for gynecologists and obstetricians as an essential part of obstetric anesthesia [29]. Finger-guided blocks in women are easily performed via a vaginal approach by palpation the ischial spines and the injection is targeted slightly medially and posteriorly to the ischial spines [30]. In literature, there are no reports comparing transvaginal and US-guidance approaches in pain relief procedures. Using a transvaginal approach for performing PNI is well-known by gynecologists, even though this technique is usually ignored by algologists, physical medicine, and interventional radiologists.

A clear understanding of the pudendal nerve anatomy is crucial for diagnosis and achieving a satisfactory response to PNI. The pudendal nerve runs in an anatomic plane formed by the sacrospinous and sacrotuberous ligament, after that it travels in a ventrocaudal direction to enter the perineal region [31,32]. The sacrospinous ligament can be palpated during pelvic examinations and painful points can give clues for determining the pudendal nerve entrapment area. Finger-guided transvaginal blocks are easily performed and a preferable way for gynecologists via a vaginal approach, similar to the pudendal nerve block performed during obstetric anesthesia. Additionally, it can be applied at the same session during pelvic examinations in an office setting [33]. Moreover, US-guided pudendal nerve blocks can allow identification of the ischial spine, and sacrospinous and sacrotuberous ligaments. It can be performed transgluteally; the pudendal vessels are identified using Doppler imaging and the injection is placed targeting the area of the pudendal nerve [14]. The advantages of US are related that it is a reproducible approach, real-time visualization of spreading of the injected solution and ionizing radiation is not utilized [20,34]. Nonetheless, the difficulty in visualizing the pudendal nerve and need of an experienced radiologist are disadvantages of the US-guided technique. Gruber et al. [17] reported that pudendal nerves were visualized just less than half of all cases using a convex US probe. In our experience, visualization of the pudendal nerve using US is generally difficult because it is situated deep within the body and surrounded by fatty tissue, in addition to having anatomic variants.

Although, PNI is commonly used for diagnostic purposes [11,35], it may also be performed as a therapeutic procedure in patients with refractory PN [6]. According to our study, it was observed that patients who underwent pudendal nerve block had significant pain relief for a long period in both groups. At the 6th month follow-up visits, the VAS scores increased slightly, but did not reach the baseline pain scores for all 3 parameters (pain with sitting, regional pain, pain during/after intercourse). In the present study, the success rates for the overall sample was 77.1% pain relief in the sitting position, 77.1% for regional pain relief from the anus to the clitoris, and 82.9% for pain relief during/after intercourse. In the US-guided TG-PNI group, one patient whose VAS pain score increased above 7 points at 6th month was treated successfully with a botulinum toxin injection. The mean change of VAS scores baseline to endpoint was higher in the TV-PNI group. We think that some of the pain was produced by superficial pelvic floor muscle spasm innervated by the pudendal nerve and TV-PNI also provides relaxation to these muscles. Similar to our results, Fanucci et al. [9] showed an improvement in pain intensity in 92.6% of patients using CT-guided PNI at the 6-month follow-up. Another previous study reported the efficacy of the CT-guided technique with a mean VAS score of 3.2 at the 6-month follow-up [6]. However, the CT-guided technique requires a radiologic facility and an experienced radiologist, and it exposes the patient to radiation.

In the literature, there is no current consensus about PNI protocols and treatment intervals. In most injection protocols a series of 3 injections are performed 2 to 6 weeks apart [9,15]. As described in other neuropathic pain conditions, memory effect is an important mechanism in the development of PN, and based on our clinical experience, PNI is effective if it is repeated twice at 1-week intervals. In a recent prospective trial, the pain improvement rate of patients was assessed at 3 months after infiltration in a single block using local anesthesia and 26% of patients had improved results [11]. Fanucci et al. [9] reported that 78% of patients had significant pain relief 24 hours after the injection with a clinical efficacy of 92% at 12 months with repeated regimens. Thoumas et al. [36] reported on 200 infiltrations with repeated injections but they failed to describe the final outcome in terms of pain relief. McDonald and Spigos [37] achieved an improvement of symptoms in 75% of a small sample of patients treated with 5 infiltrations repeated once a month. In our study, the mean VAS scores in all 3 parameters (while sitting, regional pain, and pain during/after intercourse) significantly decreased in both groups with time (P<0.001 for all) after the first and second PNI. The differences in the results are confusing but may be explained by differences in the techniques performed (type of steroid and local anesthetics injected, repeated dose intervals). Nevertheless, transvaginal nerve block did not demonstrate superiority over the transgluteal technique in none of the 3 parameters (while sitting, regional pain, and pain during/after intercourse) (P>0.05), but the transvaginal route could be preferable for gynecologists because of familiarity with vaginal procedures.

There is no research in the literature comparing the response in patients with painful sexual intercourse to pudendal nerve block treatment. Although pain during/after intercourse is not an essential criterion for PN, we demonstrated excellent improvement in VAS scores. We think that pain is mostly localized on the sacrospinous ligament during penile penetration and it creates an effect like the Tinel sign depending on the pressure, and triggers pain in the hours following intercourse.

There were no significant complications in either of the 2 groups. Temporary adverse effects following nerve blocks occurred in 8 patients with reports of temporary foot drop and numbness along the sciatic nerve distribution. This complication occurred in the 5 of the 32 blocks of US-guided TG-PNI group, and 3 of the 38 blocks in the finger-guided TV-PNI group. Fanucci et al. [9] reported transient block of the sciatic nerve in 40% of patients using CT-guidance. Needle placement under US guidance may reveal a lateral spread of injectate toward the sciatic nerve. Due to the use of the pudendal artery as a landmark, the inferior gluteal artery sometimes looks like the pudendal artery and this may result in sciatic nerve block.

The strengths of our study are the well-established standardization of the patients, and excellent postblock follow-up according to the neuropelveologic concept by a senior experienced physician. This study reflects our clinical preliminary results in PNI with 2 different techniques; long-term follow-up results will be introduced in the future.

There are several limitations to this study. However, the most significant limitation of this study was the lack of randomization because of the retrospective design. We tried to overcome this disadvantage by limiting confounding factors between the 2 groups. In the TV-PNI group, the change in mean VAS scores over time was more than the US-guided TG-PNI group, but this difference did not reach conventional levels of statistical significance. We think that this is the result of having a relatively small sample size in both groups. Finally, randomized, controlled, blind studies are necessary to elaborate on the comparison of the efficacy and safety of the approaches, as well as the timing of repeat-dose regimens of these approaches.

In conclusion, TV-PNI may be an alternative to US-guidance technique as a safe, simple, effective approach in pudendal nerve blocks.

Acknowledgments

Preliminary results of this study have been presented as an oral presentation at the 15th Pain Congress with International Participation 2018, Antalya.

Footnotes

Research Ethics

The study was approved by the ethics committee of Kocaeli University Hospital (registration number: KÜ GOKAEK-2017/14.31 2017/294). The study was registered to www.ClinicalTrials.gov (Clinical Trial registration number: NCT03973983, date of trial registration: June 2, 2019). Informed consent was obtained from each patient before the treatment.

Conflict of Interest

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTION STATEMENT

·Full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis: HGA, AK, TU, GB, IC, MY

·Study concept and design: HGA, AK, GB

·Acquisition of data: HGA, AK, GB, IC

·Analysis and interpretation of data: HGA, GB, MY

·Drafting of the manuscript: GB, HGA

·Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: AK, TU

·Statistical analysis: MY

·Obtained funding: NONE

·Administrative, technical, or material support: NONE

·Study supervision: NONE

REFERENCES

- 1.Ramsden CE, McDaniel MC, Harmon RL, Renney KM, Faure A. Pudendal nerve entrapment as source of intractable perineal pain. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2003;82:479–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Roth TM. Management of persistent groin pain after transobturator slings. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2007;18:1371–3. doi: 10.1007/s00192-007-0365-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baessler K, Schüssler B, Burgio KL, Moore K, Stanton SL. Pelvic floor re-education: principles and practice. 2nd ed. London: Springer-Verlag; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Treede RD, Jensen TS, Campbell JN, Cruccu G, Dostrovsky JO, Griffin JW, et al. Neuropathic pain: redefinition and a grading system for clinical and research purposes. Neurology. 2008;70:1630–5. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000282763.29778.59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Labat JJ, Riant T, Robert R, Amarenco G, Lefaucheur JP, Rigaud J. Diagnostic criteria for pudendal neuralgia by pudendal nerve entrapment (Nantes criteria) Neurourol Urodyn. 2008;27:306–10. doi: 10.1002/nau.20505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kastler A, Puget J, Tiberghien F, Pellat JM, Krainik A, Kastler B. Dual site pudendal nerve infiltration: more than just a diagnostic test? Pain Physician. 2018;21:83–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vancaillie T, Eggermont J, Armstrong G, Jarvis S, Liu J, Beg N. Response to pudendal nerve block in women with pudendal neuralgia. Pain Med. 2012;13:596–603. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4637.2012.01343.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Khoder W, Hale D. Pudendal neuralgia. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 2014;41:443–52. doi: 10.1016/j.ogc.2014.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fanucci E, Manenti G, Ursone A, Fusco N, Mylonakou I, D’Urso S, et al. Role of interventional radiology in pudendal neuralgia: a description of techniques and review of the literature. Radiol Med. 2009;114:425–36. doi: 10.1007/s11547-009-0371-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Filler AG. Diagnosis and treatment of pudendal nerve entrapment syndrome subtypes: imaging, injections, and minimal access surgery. Neurosurg Focus. 2009;26:E9. doi: 10.3171/FOC.2009.26.2.E9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Labat JJ, Riant T, Lassaux A, Rioult B, Rabischong B, Khalfallah M, et al. Adding corticosteroids to the pudendal nerve block for pudendal neuralgia: a randomised, double-blind, controlled trial. BJOG. 2017;124:251–60. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.14222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yamada A, Tanaka E, Niiyama S, Yamamoto S, Hamada M, Higashi H. Protective actions of various local anesthetics against the membrane dysfunction produced by in vitro ischemia in rat hippocampal CA1 neurons. Neurosci Res. 2004;50:291–8. doi: 10.1016/j.neures.2004.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Weinschenk S. Neural therapy—A review of the therapeutic use of local anesthetics. Acupunct Relat Ther. 2012;1:5–9. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Peng PW, Tumber PS. Ultrasound-guided interventional procedures for patients with chronic pelvic pain - a description of techniques and review of literature. Pain Physician. 2008;11:215–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schelhorn J, Habenicht U, Malessa R, Dannenberg C. Magnetic resonance imaging-guided perineural therapy as a treatment option in young adults with pudendal nerve entrapment syndrome. Clin Neuroradiol. 2013;23:161–3. doi: 10.1007/s00062-012-0146-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rofaeel A, Peng P, Louis I, Chan V. Feasibility of real-time ultrasound for pudendal nerve block in patients with chronic perineal pain. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2008;33:139–45. doi: 10.1016/j.rapm.2007.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gruber H, Kovacs P, Piegger J, Brenner E. New, simple, ultrasoundguided infiltration of the pudendal nerve: topographic basics. Dis Colon Rectum. 2001;44:1376–80. doi: 10.1007/BF02234801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bendtsen TF, Parras T, Moriggl B, Chan V, Lundby L, Buntzen S, et al. Ultrasound-guided pudendal nerve block at the entrance of the pudendal (Alcock) canal: description of anatomy and clinical technique. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2016;41:140–5. doi: 10.1097/AAP.0000000000000355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Weinschenk S, Hollmann MW, Strowitzki T. New perineal injection technique for pudendal nerve infiltration in diagnostic and therapeutic procedures. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2016;293:805–13. doi: 10.1007/s00404-015-3812-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Abdi S, Shenouda P, Patel N, Saini B, Bharat Y, Calvillo O. A novel technique for pudendal nerve block. Pain Physician. 2004;7:319–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bellingham GA, Bhatia A, Chan CW, Peng PW. Randomized controlled trial comparing pudendal nerve block under ultrasound and fluoroscopic guidance. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2012;37:262–6. doi: 10.1097/AAP.0b013e318248c51d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Boonstra AM, Schiphorst Preuper HR, Balk GA, Stewart RE. Cutoff points for mild, moderate, and severe pain on the visual analogue scale for pain in patients with chronic musculoskeletal pain. Pain. 2014;155:2545–50. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2014.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Faul F, Erdfelder E, Lang AG, Buchner A. G*Power 3: a flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behav Res Methods. 2007;39:175–91. doi: 10.3758/bf03193146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Elkins N, Hunt J, Scott KM. Neurogenic pelvic pain. Phys Med Rehabil Clin N Am. 2017;28:551–69. doi: 10.1016/j.pmr.2017.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hong MJ, Kim YD, Park JK, Hong HJ. Management of pudendal neuralgia using ultrasound-guided pulsed radiofrequency: a report of two cases and discussion of pudendal nerve block techniques. J Anesth. 2016;30:356–9. doi: 10.1007/s00540-015-2121-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wadhwa V, Scott KM, Rozen S, Starr AJ, Chhabra A. CT-guided perineural injections for chronic pelvic pain. Radiographics. 2016;36:1408–25. doi: 10.1148/rg.2016150263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mamlouk MD, vanSonnenberg E, Dehkharghani S. CT-guided nerve block for pudendal neuralgia: diagnostic and therapeutic implications. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2014;203:196–200. doi: 10.2214/AJR.13.11346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lee SH, Lee CJ, Lee JY, Kim TH, Sim WS, Lee SY, et al. Fluoroscopy-guided pudendal nerve block and pulsed radiofrequency treatment: a case report. Korean J Anesthesiol. 2009;56:605–8. doi: 10.4097/kjae.2009.56.5.605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kobak AJ, Evans EF, Johnson GR. Transvaginal pudendal nerve block; a simple procedure for effective anesthesia in operative vaginal delivery. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1956;71:981–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Norris MC. Obstetric anaesthesia. 2nd ed. Washington, DC: Lippincott William & Wilkins; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schraffordt SE, Tjandra JJ, Eizenberg N, Dwyer PL. Anatomy of the pudendal nerve and its terminal branches: a cadaver study. ANZ J Surg. 2004;74:23–6. doi: 10.1046/j.1445-1433.2003.02885.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Robert R, Labat JJ, Bensignor M, Glemain P, Deschamps C, Raoul S, et al. Decompression and transposition of the pudendal nerve in pudendal neuralgia: a randomized controlled trial and long-term evaluation. Eur Urol. 2005;47:403–8. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2004.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ford JM, Owen DJ, Coughlin LB, Byrd LM. A critique of current practice of transvaginal pudendal nerve blocks: a prospective audit of understanding and clinical practice. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2013;33:463–5. doi: 10.3109/01443615.2013.771155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Choi SS, Lee PB, Kim YC, Kim HJ, Lee SC. C-arm-guided pudendal nerve block: a new technique. Int J Clin Pract. 2006;60:553–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-1241.2006.00836.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Antolak S, Jr, Antolak C, Lendway L. Measuring the quality of pudendal nerve perineural injections. Pain Physician. 2016;19:299–306. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Thoumas D, Leroi AM, Mauillon J, Muller JM, Benozio M, Denis P, et al. Pudendal neuralgia: CT-guided pudendal nerve block technique. Abdom Imaging. 1999;24:309–12. doi: 10.1007/s002619900503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.McDonald JS, Spigos DG. Computed tomography-guided pudendal block for treatment of pelvic pain due to pudendal neuropathy. Obstet Gynecol. 2000;95:306–9. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(99)00520-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]