Abstract

The study aims were to determine the distance covered by goalkeepers during matches in the context of game duration and result, to identify the area of their most frequent activity, and to assess goalkeepers’ involvement in games finished with a win, draw, or loss. The investigation was based on two innovative tools: the goalkeeper’s activity index (GAI) and an analysis of 5-min periods. A video tracking system was used to monitor 17 goalkeepers from Polish National League teams during 15 matches. The GAI was applied to assess their involvement in the game. Elite goalkeepers covered 72.7%, 25.8%, and 2.5% of the distance during the game by walking/jogging, running, and sprinting, respectively. The distances covered in lost, won, and drawn matches turned out similar (mean ± SD: 4800 ± 906 m, 4696 ± 1033 m, and 4660 ± 754 m, respectively). There were no significant differences between the distances covered in the first and second halves. The area of most frequent activity was the middle sector of the penalty area between the goal and penalty area lines. ANOVA results showed that in drawn matches, goalkeepers’ activity significantly differed in mean values of the GAI in comparison with that in won and lost games (p = 0.034, p = 0.039, respectively). It was noted that goalkeepers tended to intervene more often in games where their team was winning rather than in those with a losing result. Their direct involvement in defending the goal was the lowest in drawn games.

Keywords: Football, Video analysis, Activity profile, Performance index, Match outcome

INTRODUCTION

Goalkeepers play a special role in the modern football game. They are required not only to defend the goal, but also to actively cooperate with their partners both during defending and attacking. Therefore, their motor activity in the context of various tactical situations should be considered in detail [1,2]. Accurate analyses are required by modern team games in order to rationally manage the players’ training process with the aim of ultimately improving performance [3,4,5]. Establishing a performance/activity profile of the player is among the elements [6]. To achieve this, special image-processing systems, automatic and semi-automatic recording of players’ movements, and satellite navigation have been employed for time-motion and notation analysis [7,8,9,10,11,12,13]. Currently, systems composed of multiple cameras that allow the encoding of action with the ball and automatically register the players’ movement are often used [14,15,16,17,18]. These research tools, however, are expensive and require specialized operation.

The activity profile of a player, considered as the distance covered in the game and the time needed to complete it, as well as velocity and acceleration, indirectly characterizes their game involvement. Therefore, it is necessary to monitor the goalkeepers on the pitch by tracking their activity. Many studies have used the aforementioned systems to track whole teams, players of particular formations and sports levels, among others [16,19,2,18,20]. The results obtained by Dellal et al. [2] showed that players’ activity could depend on the game result. For instance, players did not undertake the same activity when their team was winning compared with a losing situation. The activity profile of goalkeepers has received less attention, although it could have a major influence on game outcomes [21]. In this context, Di Salvo et al. [22] analysed the distance covered by goalkeepers from English Premier League teams and Condello et al. [23] conducted a similar study on non-professional goalkeepers. Condello’s work quantified the intensity of movements, their durations, and distances covered in terms of continuous and rapid changing of activity type.

On the other hand, Padulo et al. [24] focused on forward and lateral actions along with changes of direction in goalkeepers in order to assess their individual match performance. The results of their study were designed to constitute a valuable material for the coach. In turn, Liu et al. [25] examined 15 match performance indicators of elite goalkeepers considering three situational variables (opposition, outcome, and location). The results indicated that high-level team goalkeepers did not show differences in their match performance indicators during contests won, drawn, and lost, but the actual distances covered and the quality of these movements across matches with different outcomes (won, drawn, and lost) are unknown. Specifically, the involvement of the goalkeeper in terms of the time and frequency of actions and their locality remains unspecified.

Hence, the purpose of this study was to determine the time-motion characteristics of goalkeepers during official games played at the professional level: distance covered in the situation of game won, drawn, and lost. Moreover, goalkeepers’ involvement in the context of the time and frequency of actions and place where these were taken for games won, drawn, and lost were studied.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Subjects

A total of 17 male goalkeepers from 15 teams of the Polish National League (the highest tier in Poland) were monitored over 15 matches (6 won, 5 drawn, 4 lost) during the 2011/2012 season (games 1–7 were played in the first round, games 8–15 in the second round). Their average age was 25.0 ± 5.1 years (mean ± SD), and they had practice experience in soccer of 4–18 years at the highest level of their age category. The athletes’ height ranged from 186.0 to 196.0 cm (189.9 ± 3.3 cm) and body mass from 82.5 to 96.0 kg (86.9 ± 4.5 kg). Written informed consent was obtained from the players to use their match data. The University Institutional Review Board approved this study.

Data collection and analyses

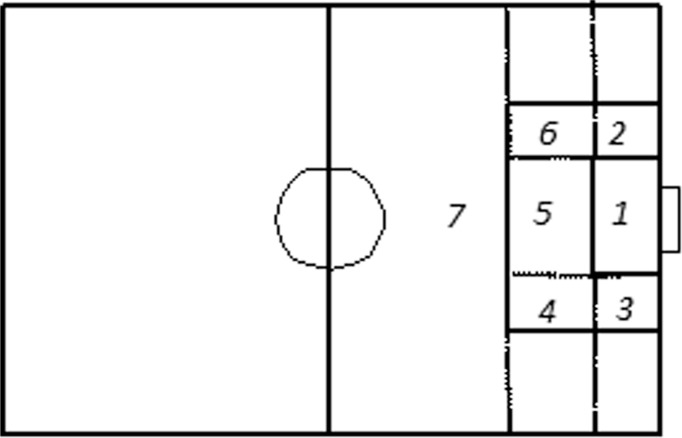

All matches were played on a heated and irrigated natural grassy pitch with artificial lighting. The pitch dimensions were 105 × 68 m, which meets the UEFA requirements. The goalkeepers’ movements were recorded during the entire match by two cameras (NEX-VG30EH Interchangeable Lens Full HD Camcorder, Sony Corp., Japan) with the sampling rate of 60 Hz at the resolution of 1920 × 1080 [26]. One camera was fixed on a tripod and placed under the tribunes, on the extension of the centre line of the pitch, 15 m from the side line, at the height of about 12 m. The axis of the camera was directed at the centre of the halfway line so that the recordings covered the entire field of play on the half of the court on the side of the studied goalkeeper. The footage from this fixed camera served to indicate the goalkeeper’s position on the pitch throughout the match. The other camera was mobile and recorded the goalkeeper’s actions in close-up. The coordinates of the image were converted into actual coordinates by using the algorithm described by Aschenbrenner et al. [27] with an average error of the actual position of about 3–5% and the transposition error below 3%. The algorithm does not require knowledge of the coordinate position of the camera but only the real dimensions of the observed object. The distance covered by the player and the velocity of his movements were calculated using AS4 software [27]. Match analyses distinguished four categories of motion (standing, from 0 to < 0.4 km/h; walking/jogging, from 0.4 to ≤ 12 km/h; low-/moderate-/high-speed running, from > 12 to < 23 km/h; sprinting, ≥ 23 km/h), which allowed for a comparison with the study by Di Salvo et al. [18] on goalkeepers’ activity. The total time, distance covered, and speed were obtained for each category. The data were noted on an observation sheet. Sectors of actions were marked by symbols (Figure 1).

FIG. 1.

The analysed sectors of the goalkeepers’ actions.

The data were analysed for the following time intervals: the whole match, and the first and the second halves of the game at 5-min intervals. The data were further separated on the basis of the match result. The extra time added by the referee to each half was omitted when analysing the 5-min intervals in order to standardize the playing time to 90 min (each 45 min gave nine 5-min slots). To assess the goalkeeper’s involvement in the game in 5-min intervals, the goalkeeper’s activity index (GAI) [28,29]) was applied. It was calculated in accordance with the following formula:

| GAI = (vi/vav + d.ri/d.rav + f.ii/f.iav)/3 |

where: GAI = goalkeeper’s activity index; v i = mean speed in the time interval i; v av = mean speed in the whole match; d.r i = distance covered (sprint and running speed only) in the time interval i; d.r av = distance covered (sprint and running speed only) in the whole game multiplied by the time interval I and divided by the duration of the game; f.i i = frequency of actions performed in the time interval i; f.i av = frequency of actions performed in the whole game.

The GAI was constructed on the basis of our own observations and consultations with soccer experts. It was assumed, for example, that an increase in activity would be situational, driven by the game outcome, and characterized by increased velocity (v i /v av), longer distance covered (d.r i /d.r av), and/or higher frequency of actions (f.i i /f.i av). Mean GAI values above 1.0 indicate higher levels of activity in a time interval in comparison with the mean activity in the whole game [28,29].

Statistical analysis

All data were reported as mean ± SD. To verify the hypothesis about a lack of differences in the goalkeepers’ activity in each time interval, Pearson’s chi-square test was applied to examine each variable across the three match categories (win, loss, draw). Differences in mean velocity, distance covered, and GAI were verified with one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05. The statistical analysis was performed using the Statistica for Windows software, version 10.0 (StatSoft, Inc., Tulsa, OK, USA).

RESULTS

The data of the goalkeepers’ activity during the first and the second halves of matches and during whole matches are displayed in Table I. The goalkeepers moved more frequently (p = 0.045) sprinting (≥ 23 km/h) in the second half compared with the first half (mean ± SD: 0.14 ± 0.1 min and 0.11 ± 0.0 min, respectively). They also sprinted significantly more frequently in matches lost (0.29 ± 0.1 min) than in those drawn or won (0.20 ± 0.0 min, p = 0.022 and 0.23 ± 0.0 min, p = 0.39, respectively). The players spent significantly less time standing during matches lost (17.8 ± 8.7 min) in comparison with matches drawn (37.2 ± 6.7 min; p = 0.019) or won (23.6 ± 4.0 min; p = 0.030).

Table I.

Time-motion analysis of the goalkeepers’ activity in official games

| Match | n | Time [min] | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Standing | Walking/jogging | Running | Sprinting | |||

| 1st half | All | 30 | 11.3 ± 5.6 | 35.5 ± 5.8 | 1.8 ± 0.4 | 0.11* ± 0.0 |

| L | 8 | 11.3 ± 5.9 | 36.1 ± 2.3 | 1.8 ± 0.8 | 0.11 ± 0.0 | |

| D | 14 | 14.6 ± 6.5 | 39.2 ± 3.7 | 1.8 ± 0.5 | 0.17 ± 0.1 | |

| W | 8 | 11.4 ± 3.3 | 34.9 ± 6.3 | 1.9 ± 0.4 | 0.11 ± 0.0 | |

| 2nd half | All | 30 | 12.7 ± 5.8 | 36.5 ± 5.3 | 1.8 ± 0.7 | 0.14* ± 0.1 |

| L | 9 | 12.0 ± 5.4 | 35.7 ± 4.0 | 2.1 ± 1.0 | 0.11 ± 0.1 | |

| D | 12 | 8.6 ± 5.5 | 40.2 ± 2.7 | 1.9 ± 0.2 | 0.27 ± 0.2 | |

| W | 9 | 15.4 ± 4.9 | 35.4 ± 7.1 | 1.4 ± 0.8 | 0.10 ± 0.1 | |

| Whole match | All | 30 | 24.0 ± 10.4 | 72.0 ± 9.3 | 3.6 ± 0.9 | 0.25 ± 0.1 |

| L | 10 | 17.8* ± 8.7 | 72.0 ± 8.7 | 3.8 ± 1.3 | 0.29* ± 0.1 | |

| D | 10 | 37.2* ± 6.7 | 73.6 ± 9.2 | 3.4 ± 0.3 | 0.20* ± 0.0 | |

| W | 10 | 23.6* ± 4.0 | 71.2 ± 0.3 | 3.5 ± 0.4 | 0.23* ± 0.0 | |

Data are presented as mean ± SD

significant differences at p < 0.05.

Note: time spent for each walking/running gait in whole matches and in the first and second halves, for all games and by the outcome: loss (L), draw (D), and win (W) (mean ± SD). The extra time was included in time-motion analysis (the mean duration of the analysed games was found to be nearly 100 min).

Goalkeepers covered 72.7%, 24.8%, and 2.5% of the distance during a given game by walking/jogging, running, and sprinting, respectively (Table II). A significantly longer distance was covered by running (1233 ± 571 m, p = 0.045) and sprinting (133 ± 89 m, p = 0.39) when losing relative to drawing. On average, the longest distance was covered in matches lost, although the greatest distance covered (in any one game) occurred when winning (6189 m) and the shortest when losing (3850 m).

Table II.

Distance covered with different velocities and the average speed during all matches and by the outcome

| Match | n | Distance [m] | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Walking/jogging | Running | Sprinting | Total | ||

| L | 10 | 3434 ± 595 | 1233* ± 571 | 133* ± 89 | 4800 ± 906 |

| D | 10 | 3503 ± 600 | 1062* ± 168 | 95* ± 14 | 4660 ± 754 |

| W | 10 | 3417 ± 770 | 1174 ± 252 | 105 ±18 | 4696 ± 1033 |

| All | 30 | 3441 ± 597 | 1175 ± 371 | 114 ± 55 | 4730 ± 835 |

Data are presented as mean ± SD

significant differences at p < 0.05.

Note: the data are representative for all matches and by the outcome: loss (L), draw (D), and win (W) (mean ± SD).

Table III shows the characteristics of goalkeepers’ actions, considering the average number of actions performed in the first and second halves and in whole matches, as per the won, lost, and drawn games, along with the mean time between successive interventions.

Table III.

The number of actions performed by goalkeepers and the time spent between the actions

| Match | Number of actions [n] | Time between actions [min] | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1st half | All | 18 ± 4 | 2.4 ± 0.4 |

| L | 17 ± 3 | 2.4 ± 0.5 | |

| D | 16 ± 3 | 2.6 ± 0.4 | |

| W | 19 ± 7 | 2.4 ± 0.4 | |

| 2nd half | All | 18 ± 4 | 2.6 ± 0.6 |

| L | 18 ± 7 | 3.2 ± 1.4 | |

| D | 19 ± 3 | 2.5 ± 0.5 | |

| W | 19 ± 2 | 2.4 ± 0.2 | |

| Whole match | All | 36 ± 4 | 2.5 ± 0.3 |

| L | 36 ± 7 | 2.5 ± 0.6 | |

| D | 34 ± 3 | 3.1 ± 0.1 | |

| W | 37 ± 7 | 2.4 ± 0.3 | |

Note: the data are representative for whole matches and for the first and second halves, for all games and by the outcome: loss (L), draw (D), and win (W) (mean ± SD).

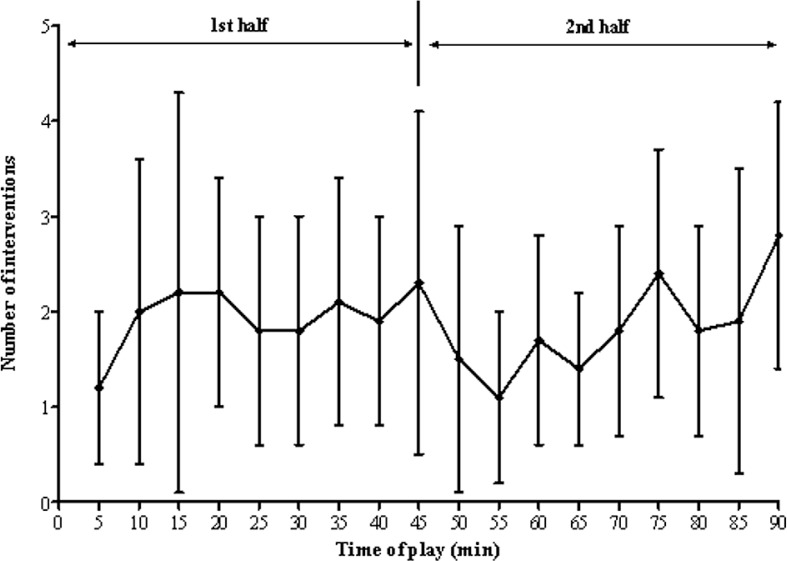

The goalkeepers were also found to have performed most interventions (in 5-min intervals) between the 10th and the 15th min of matches, at the end of the first half (between the 40th and the 45th min), and towards the end of the game (about the 75th and the 90th min) (Figure 2). In total, there were 38 goals scored in the observed 15 matches, including three penalty goals and one own goal.

FIG. 2.

Average number of interventions (mean ± SD) performed by goalkeepers in 5-minute intervals

The extra time added by the referee to each half was omitted when analysing the 5-min intervals in order to standardize the playing time to 90 min (each 45 min gave nine 5-min slots).

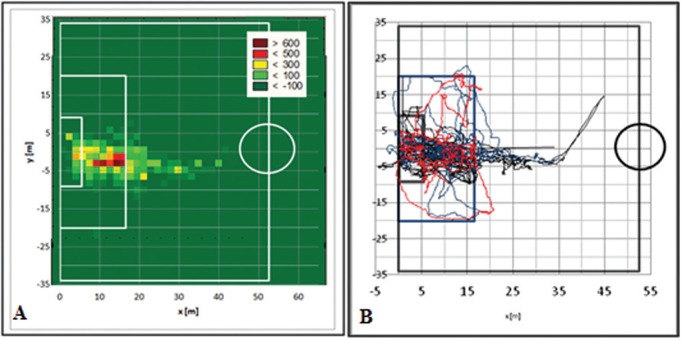

The subjects moved mostly in the middle zone of the penalty area, in sectors 1 and 5 (Figure 3). They moved much less outside the penalty box, in sector 7, and occasionally in sectors 2 and 3. The lowest number of actions occurred in the side sectors, 4 and 6, generally during defensive displays.

FIG. 3.

The goalkeepers’ movements in several zones of the pitch during the matches analysed: (A) goalkeepers’ sectors with action frequencies represented in pseudo-colour to discriminate the target of the actions <100/> 600 (all games averaged); (B) diagram based on the goalkeepers’ movements in one half of a match (a sample).

Similar GAI values characterized goalkeepers during both the first and second halves of games and in the won and lost matches (1.03 ± 0.25 and 1.02 ± 0.29, respectively). However, in drawn games, the mean values of GAI were significantly lower (0.91 ± 0.22) than in the lost (p = 0.039) and won ones (p = 0.34). Mean GAI values in the 5-min intervals, as in the case of the mean number of interventions (cf. Figure 2), were the highest in the middle of the first halves (between the 10th and the 25th min 1.09 ± 0.17), at the end of the first halves (between the 40th and the 45th min, 1.07 ± 0.37), and towards the end of the game (about the 75th and the 90th min of the game, 1.05 ± 0.27 and 1.22 ± 0.26, respectively). The value of GAI in the last 5-min interval of the game differed significantly from that observed for most 5-min time intervals (0.004 ≤ p ≤ 0.045), with the exception of intervals between the 15th and the 25th min, the 40th and the 45th min, and the 75th and the 80th min. No statistically significant differences were found for the mean values of this index between won and lost matches or between the first and the second halves.

DISCUSSION

Research describing the match kinematics and effectiveness of goalkeepers is rare. Yet, the comprehensive assessment of team activity is only possible if all players are considered, including those in the goalkeeping position. Therefore, the analysis of goalkeepers’ kinematics in the situational context is crucial to grasp the individual and collective behaviour, training preparation, recovery protocols, and match strategies. The present study has shown that the motor activity of goalkeepers is lower than that of other players. The distance covered by goalkeepers with the highest velocity is several times shorter than the distance covered in other playing positions [2,18,30,31]. The mean total distance covered by a goalkeeper during a match was 4730 ± 835 m (Table II). This value is lower by over 800 m (5611 ± 613 m) than the one indicated by Di Salvo et al. [22] and higher by over 500 m (4183 m) than that found by Soroka and Bergier [32]. Hence, one can assume that goalkeepers cover half of the distance compared with field players. Actions such as running and sprinting were registered more often in won games than in drawn ones, in second halves of matches, in the last two quarters of both game halves than in other periods, and in the central area of the penalty box and penalty area when it comes to the location. Drawn matches were also characterized by fewer interventions of goalkeepers compared with those won or lost. In terms of sprinting, the analysed goalkeepers were much more active in matches lost than in those drawn and won. Such behaviour patterns reflect involvement in the game. On the other hand, lack of activity (standing) was also lower in matches lost than in the won and drawn ones (Table I). Similar conclusions were reached by Szwarc et al. [33], Lago-Peñas and Dellal [34], and Soroka and Bergier [32].

As demonstrated in Table II, the goalkeepers spent 96.2% of the game time standing or walking/jogging, 3.6% running at low/moderate/high speed, and only 0.2% sprinting. This is in line with other studies [23,22,30], which showed that top-class goalkeepers covered 73% of the distance during the game (3441 ± 597 m) by walking and jogging, 25% (1175 ± 371 m) by low-/moderate-/high-speed running, and 2% (114 ± 55 m) by sprinting.

The difference arises from activity profiling across four ranges of intensities in this study, similar to Di Salvo et al. [18], who appointed five ranges to analyse players on the pitch (standing, walking, jogging, from 0 to 11 km/h; low-speed running, from 11.1 to 14 km/h; moderate-speed running, from 14.1 to 19 km/h; high-speed running, from 19.1 to 23 km/h; sprinting, > 23 km/h). The adopted division reflects the specific nature of a goalkeeper’s game. Moving at a speed of up to 12 km/h (standing, walking, jogging) means low involvement of the goalkeeper in the game; moving at speeds from > 12 to < 23 km/h (low-/moderate-/high-speed running) indicates their preparation to intervene, while activity at speeds ≥ 23 km/h (sprinting) accompanies actions in limited time and space, under pressure: in attacking, it initiates counterattack actions; in defence, it acts against goal loss or creates a situation to score a goal.

A detailed analysis of the number of interventions in 5-min time sequences (Figure 2) indicates a rise in goalkeepers’ activity between the 10th and 15th min of the match, at the end of the first half of the game, and around the 75th and the 90th min. We believe that the increased activity of goalkeepers’ actions in the last phases of both match halves is closely related to typical tactical situations when players seek to change the game status, creating situations to score goals [18,35,36,37]. On the other hand, the increased goalkeepers’ activity between the 10th and 15th min of the match seems difficult to explain.

The analysis of goalkeepers’ actions with regard to different pitch zones (Figure 3) emphasized the greatest activity in the middle zone of the penalty box (about 80% of scored goals, including 20% from the goal area) [38,39,40,41], i.e. between the lines of the goal area and the penalty box (sectors 1 and 5), and much less frequent activity outside the penalty box (sector 7).

The value of the tested goalkeepers’ GAI was similar for the first and the second part of the playing time (1.01 and 1.00, respectively) and differed slightly depending on the competition result. The lowest GAI value was found in drawn matches and the highest when winning (0.91 and 1.03, respectively). Significant differences were observed between the mean values of GAI in drawn matches and won and lost matches, thus indicating that goalkeepers’ direct involvement in the game was the lowest in drawn matches.

Regarding the distance covered and the velocity of actions, high values of the SD of GAI components, especially for the frequency of interventions, confirm the data obtained by other authors (e.g. Armatas et al. [36]). The conclusions show that the number and efficiency of actions creating goal-scoring situations are diverse and depend on many factors. These primarily cover the planned strategy and the level of players’ skills (motor features, technical and tactical skills, team play, etc.).

Limitations

Here we report an inexpensive match-analysis tool combining a simple video set-up and image analysis using our own (freeware) software. However, the accuracy of our data was dependent on the position of each camera and the reference area. Owing to technical constraints, it was not feasible to place the camera as high as possible and closer to the goalkeeping area. Another problem was to capture rapid changes in the athletes’ direction and speed. Our software for analysing raw data was equipped with filters for smoothing random errors when tracking an athlete’s motion on the screen. This did, however, require some manual adjustments by the operator to reduce reading error. The accuracy of our tools also depended on the reliability and accuracy of the operator; therefore, to eliminate individual errors, it is recommended to have the same person to read video data, which could be problematical with multiple games. All games used in our analysis were played exclusively at the stadium of the Arka Gdynia team, which helped to address any variability due to different pitch and stadium orientations. Finally, only one goalkeeper was recorded per match because of constraints associated with the availability of cameras and equipment. Recording two goalkeepers simultaneously (from opposing teams) would have improved the robustness of the match-outcome results.

Importantly, it was not our goal to determine the influence of the goalkeeper’s motor activity on the result, but rather to track changes in movement patterns over time. Some patterns and similarities were sought in selected situations. Their closer research and determination will explain the conditions of the goalkeeper’s game. On the basis of this study, it is possible to draw some practical conclusions in guiding the motor training and tactical preparation of a goalkeeper.

Perspectives

To ensure the quality of data extracted, one could place a camera as high as possible and close to the centre of a pitch/goalkeeper activity area; the use of two or more fixed cameras may increase precision (but also costs). The fine-tuning of algorithms that convert screen coordinates into real values could also be improved. More data on individual athletes would provide additional novelty and allow us to develop position-specific algorithms for more in-depth comparisons (e.g. within-person patterns), a level of analysis not yet performed [22,24]. An additional area of research may be the analysis of a goalkeeper’s game with detailed division into fragments in different tactical situations, for example, positional attack of one’s own team in specific game phases, possession of the ball, passing from attacking to defending, defending, and passing from defending to attacking.

CONCLUSIONS

In a match, goalkeepers cover half of the distance covered by athletes from the playing field, but the profile of their motor activity is similar to that observed for the other positions. Their involvement in the game is higher in the second halves of matches and in the last stages of each part of the game. In lost matches, they show higher activity than in matches won or drawn. The determination of specific requirements for goalkeepers considering their motor activity and involvement in the game depending on the time and result enables rational management of the preparation process for matches.

Conflict of interest declaration

This statement is to certify that all authors have seen and approved the manuscript being submitted. We warrant that the article is the authors’ original work. We warrant that the article has not received prior publication and is not under consideration for publication elsewhere. On behalf of all co-authors, the corresponding author shall bear full responsibility for the submission.

All authors agree that author list is correct in its content and order and that no modification to the author list can be made without the formal approval of the Editor-in-Chief.

The authors have no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Hughes MD, Bartlett RM. The use performance indicators in performance analysis. J Sport Sci. 2002;20:739–754. doi: 10.1080/026404102320675602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dellal A, Chamari C, Wong DP, Ahmaidi S, Keller D, Barros ML, Carling C. Comparison of physical and technical performance in European professional soccer match-play: The FA Premier League and La Liga. Euro J Sport Sci. 2011;11:51–59. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chelly MS, Hermassi S, Aouadi R, Khalifa R, Van den Tillaar R, Chamari K, Shephard RJ. Match analysis of elite adolescent team handball players. J Strength Cond Res. 2011;25(9):2410–2417. doi: 10.1519/JSC.0b013e3182030e43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Arruda AF, Carling C, Zanetti V, Aoki MS, Coutts AJ, Moreira A. Effects of a very congested match schedule on body-load impacts, accelerations, and running measures in youth soccer players. Int J Sports Physiol Perform. 2015;10(2):248–252. doi: 10.1123/ijspp.2014-0148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kempton T, Sirotic AC, Rampinini E, Coutts AJ. Metabolic power demands of rugby league match play. Int J Sports Physiol Perform. 2015;10(1):23–28. doi: 10.1123/ijspp.2013-0540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hughes C. The winning formula. London: William Collins Sons & Co Ltd; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Reilly T, Thomas V. A motion analysis of work rate in different positional roles in professional football match play. J Hum Mov Stud. 1976;2:87–89. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kuzora P, Erdmann WS. Computer program for research of team games. In: Erdmann WS, editor. Locomotion ’98. Proceedings. 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hermoso VMS. ISBS 2002, Caceres-Extremadura-Spain: Photogrammetric system for movement analysis in team sports. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shiokawa M, Takahashi K, Kan A, Usui KOS, Choi CS, Deguchi T. Computer analysis of a soccer game by the DLT method focusing on the movement of the players and the ball. V World Congress of Science and Football; 2003; Lisbon-Portugal. Book of Abstract:267. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vandenbroucke N, Macaire L, Postaire JG. Color image segmentation by pixel classification in an adapted hybrid color space Application to soccer image analysis. Comput Vis Image Und. 2003;90(2):190–216. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Figuero PJ, Leite NJ, Barros RML, Cohen I, Medioni G. Tracking soccer players using the graph representation; Proceedings of the 17th International Conference on Pattern Recognition (ICPR).2004. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Iwase S, Saito H. Parallel tracking of all soccer players by integrating detected positions in multiple view images; Proceedings of the 17th International Conference on Pattern Recognition (ICPR); 2004; Cambridge-UK. pp. 751–754. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Figueroa PJ, Leite NJ, Barros RML. Background recovering in outdoor image sequences: An example of soccer players segmentation. Image Vision Comput. 2006;24(4):363–374. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Figueroa PJ, Leite NJ, Brros RML. Tracking soccer players aiming their kinematical motion analysis. Comput Vis Image Und. 2006;101:122–135. 2. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Barros RML, Misuta MS, Menezes RP, Figueroa PJ, Moura FA, Cuhna SA, Leite NJ. Analysis of the distances covered by First Division Brazilian soccer players obtained with an automatic tracking method. J Sport Sci Med. 2007;6:233–242. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Di Salvo V, Collins A, Mc Neill B, Cardinale M. Validation of Prozone®. A new video-based performance analysis system. Int J Perf Anal Spor. 2006;6(1):108–119. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Di Salvo V, Baron R, Tschan H, Calderon Montero FJ, Bachl N, Pigozzi F. Performance Characteristics According to Playing Position in Elite Soccer. Int J Sports Med. 2007;28(3):222–227. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-924294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bradley PD, Di Mascio M, Peart D, Olsen P, Sheldon B. High intensity activity profiles of elite soccer players at different performance levels. J Strength Cond Res. 2010;24(9):2343–2351. doi: 10.1519/JSC.0b013e3181aeb1b3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Di Salvo V, Baron R, Gonzalez Haro G, Gormasz H, Pigozzi F, Bachl M. Sprinting analysis of elite soccer players during European Champions League and UEFA Cup matches. J Sport Sci. 2010;28:1489–1494. doi: 10.1080/02640414.2010.521166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liu H, Gómez MA, Lago-Peñas C. Match Performance Profiles of Goalkeepers of Elite Football Teams. Int J Sports Sci Coach. 2015;10(4):669–682. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Di Salvo V, Benito PJ, Calderón FJ, Di Salvo M, Pigozzi F. Activity profile of elite goalkeepers during football match play. J Sport Med Phys Fit. 2008;48:443–446. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Condello G, Lupo C, Cipriani A, Tessitore A. Activity profile of a non-professional goalkeeper during official matches. Annals of Researchin Sport and Physical Activity. 2011;2:94–95. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Padulo J, Haddad M, Ardigò L P, Chamari K, Pizzolato F. High frequency performance analysis of professional soccer goalkeepers: a pilot study. J Sport Med Phys Fit. 2014;55:557–562. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liu H, Gómez MA, Lago-Peñas C, Arias-Estero J, Stefani R. Match Performance Profiles of Goalkeepers of Elite Football Teams. Int J Sports Sci Coach. 2015;10(4):669–682. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Padulo J, D’Ottavio S, Pizzolato F, Smith L, Annino G. Kinematic analysis of soccer players in shuttle running. Int J Sports Med. 2012;33:459–462. doi: 10.1055/s-0032-1304641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Aschenbrenner P, Lipińska P, Erdmann WS. Application of the AS-4 software in research on players’ kinematics on a large area in 3D coordinates as an alternative to commercial programs. Baltic Journal of Health and Physical Activity. 2012;4:172–179. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Erdmann WS. Kinematics of tactics of men’s 1500 m freestyle swimming at 2008 US Olympic Team Trials Finals. Research Yearbook (Jedrzej Sniadecki Academy of Physical Education and Sport) 2008;14(2):92–98. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lipinska P, Erdmann WS. Kinematics of tactics in the Men’s 1500 m freestyle swimming final at the Beijing 2008 Olympic Games; ISBS-Conference Proceedings Archive; 2009; pp. 467–470. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Carling C, Le Gall F, Dupont G. Analysis of repeated high intensity running performance in professional soccer. J Sport Sci. 2012;30:325–336. doi: 10.1080/02640414.2011.652655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Di Salvo V, Pigozzi F, González-Haro C, Laughlin MS, De Witt JK. Match performance comparison in top English soccer leagues. Int J Sports Med. 2013;34:526–532. doi: 10.1055/s-0032-1327660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Soroka A, Bergier J. The relationship among the somatic characteristics, age and covered distance of football players. Human Movement. 2011;12:353–360. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Szwarc A, Lipińska P, Chamera M. The efficiency model of goalkeeper’s actions in soccer. Baltic Journal of Health and Physical Activity. 2010;2:132–138. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lago-Peñas C, Dellal A. Ball possession strategies in elite soccer according to the evolution of the match-score: The influence of situational variables. J Hum Kinet. 2010;25:93–100. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Abt GA, Dickson G, Mummery WK. Goal scoring patterns over the course of a match: An analysis of the Australian National Soccer League. In: Spinks W, Reilly T, Murphy A, editors. Science and Football IV. London: Routledge; 2002. pp. 107–111. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Armatas V, Yiannakos A, Sileloglou P. Relationship between time and goal scoring in soccer games: Analysis of three world cups. Int J Perf Anal Spor. 2007;7:48–58. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Szwarc A, Kromke K, Lipińska P. The efficiency of football players in one-against- one game in the aspect of situational factors of a sports fight. Archives of Budo. 2012;8:1–12. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sainz de Baranda P, Ortega E, Palao J. Analysis of goalkeepers’ defence in the World Cup in Korea and Japan in 2002. Eur J Sport Sci. 2008;8:127–134. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hrćiarik P, Perâćik P. In: Prskalo I, Novak D, editors. The analysis of the game performance of goalkeepers in the U-19 European Championships qualifier matches; Physical Education in the 21st Century – Pupils’ Competencies, Proceedings Book of 6th FIEP European Congress, 18–21 June 2011, Poreć, Croatia; 2011; Poreć: Hrvatski Kineziološki Savez; pp. 593–603. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Armatas V, Yiannakos A. Analysis and evaluation of goals scored in 2006 World Cup. J Sport Health Sci. 2010;2:119–128. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wright C, Atkins S, Polman R, Jones B, Lee S. Factors Associated with Goals and Goal Scoring Opportunities in Professional Soccer. Int J Perf Anal Spor. 2011;11(3):438–449. [Google Scholar]