Abstract

Background: Primary spinal cord melanocytoma is an extremely rare condition and the pathogenesis of melanocytomas remains unclear. The diagnosis and treatment of primary spinal cord melanocytomas does not have a standard method. Case presentation: We present a case of a 73-year-old male who presented with a six-month history of progressive numbness and weakness in his lower extremities without gatism. Spinal magnetic resonance image (MRI) revealed a spinal cord tumor at the level of T10-T11. At surgery, the spinal cord was covered with black-brown neoplastic tissue. There were no metastatic lesions. At one year after surgery, the patient is still alive. Conclusions: The diagnosis of melanocytoma needs to take a comprehensive consideration and surgical resection is still the best treatment.

Keywords: Melanocytoma, spinal cord, primary

Introduction

Primary spinal cord melanocytoma is a rare lesion which originates from melanocytes in leptomeninges. Compared to the metastatic lesions, primary melanocytomas has an incidence of 1 per million [1]. To the best of our knowledge, the pathogenesis of melanocytomas remains unclear. The epidemiological data indicate that sex, race and geography may affect the incidence of melanocytic neoplasms in body and histopathologic features [2]. We present a 73-year-old man with a six-month history of progressive numbness and weakness in his lower extremities. The diagnosis requires exclusion of a primary cutaneous or ocular lesion, as in rare instances melanoma may metastasize to the spinal cord [3,4]. To date, no systematic diagnostic strategy has yet been formed. Surgical resection and radiotherapy have been used to treat melanocytoma [5]. We report a case of this uncommon lesion and also describe the molecular footprint that characterizes it.

Case presentation

Introduction of medical history

A 73-year-old male patient was admitted to the hospital for lower extremity numbness and weakness with a 6-month history. In the past 6 months, the patient felt numbness of his lower limbs, which was heavier under the knee joint, both feet were cold, and walking was unsteady. The numbness and weakness of the lower limbs were progressively aggravated, so that there was a sudden numbness in the lumbosacral region 3 months previously, followed by paralysis of the lower extremities, and loss of feeling, but without gatism. This relieved after about one hour, and the latter episode was repeated twice. The patient came to our hospital with unbearable symptoms.

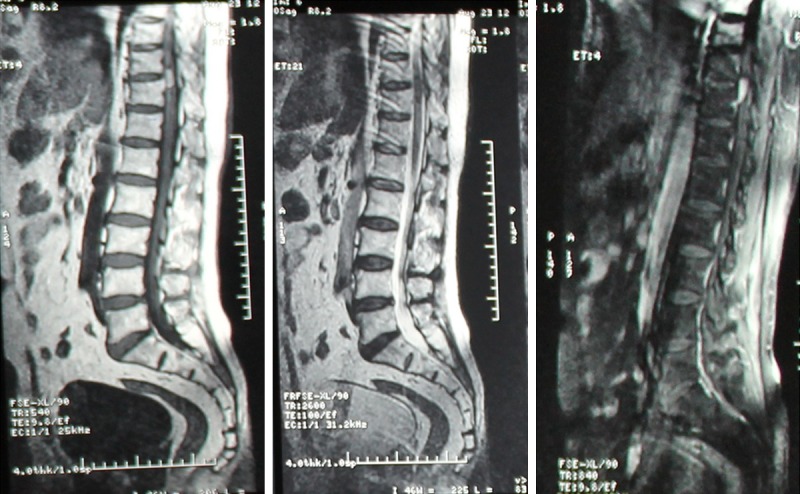

Manifestation of spinal MRI

After admission to the hospital, the spinal MRI revealed on the left side of the inner canal of the vertebral plane, a spinal cord tumor about the size of 1.5 cm*1.5 cm, located at the level of T10-T11, that was hyperintense on T1-weighted imaging and hypointense on T2-weighted imaging, significantly enhanced after T1 enhancement, and the spinal cord was compressed at the corresponding segment (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Spinal magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). The lesion showed hyperintense on T1-weighted imaging, on T2-weighted imaging and on T1 enhancement phase imaging.

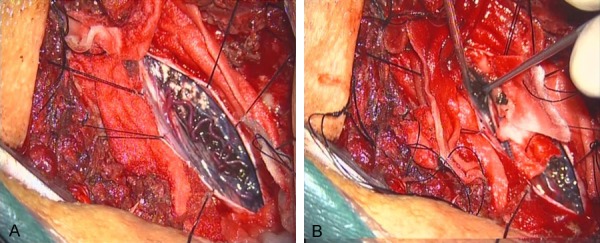

Intraoperative condition

No obvious contraindication was found, and surgical resection was used to treat the lesion. Fully exposed T10-11 by longitudinal incision of dura mater, showed tortuous blood vessels on the surface of the spinal cord, with black granular substance deposition. He underwent complete microsurgical resection (Figure 2A, 2B).

Figure 2.

A. Intraoperative photographs showing the pigmented lesion with tortuous blood vessels coming near the surface of the spinal cord. B. Myelotomy was required to expose the tumor surface.

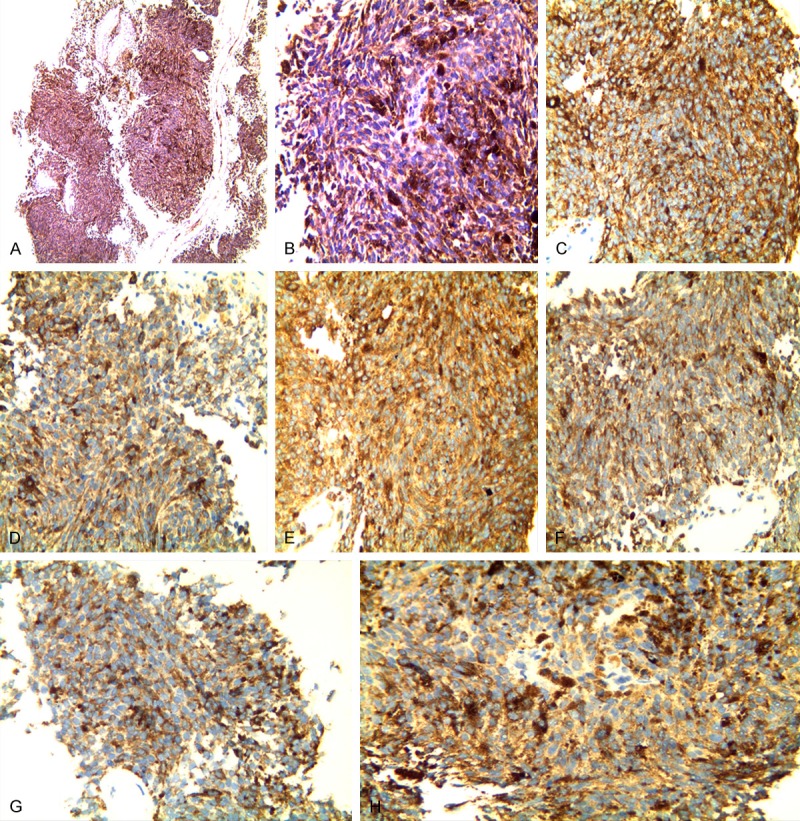

Pathological examination

The resection specimen underwent pathological examination with HE staining (Figure 3A, 3B). A large number of melanin granules were deposited in the tumor cells, the morphology of the cells was consistent, and small nucleoli could be seen in some cells. Immunohistochemically, these histiocytes were positive for HMB45 (+++), S-100 (+++), vimentin (+), Ki-67 (++), CK (-), CD99 (-) (Figure 3C-H).

Figure 3.

A, B. Histopathologic examination (100×, 400×) reveals a large number of melanin granules deposited. C-H. Immunohistochemically, these histiocytes were positive for HMB45 (+++), S-100 (++), vimentin (+), Ki-67 (+), CK (-), and CD99 (-).

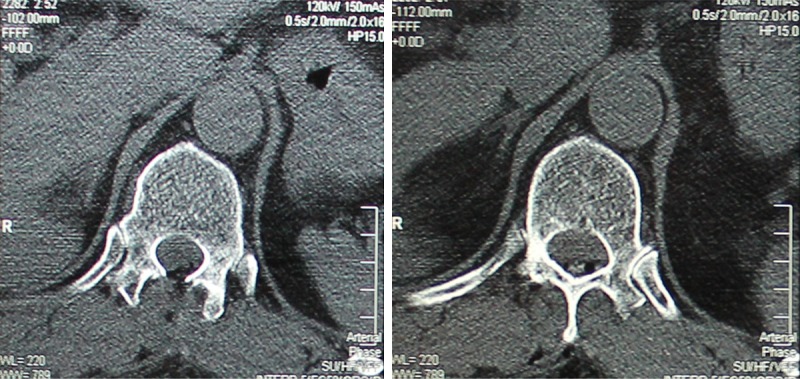

Postoperative condition

Consultation with dermatologists and ophthalmologists suggested that there were no melanocytic lesions in other parts of the patient. Therefore, a diagnosis of primary melanocytoma was made. The neurologic symptoms of lower extremity numbness and asthenia were gradually improved after operation. One month after surgery, review of spinal CT showed a good recovery (Figure 4). The patient did not receive other treatments. After a year of follow-up, he is still alive.

Figure 4.

Spinal CT showed a good recovery one month after surgery.

Discussion

According to the classification of central nervous system tumors by the World Health Organization in 2016, melanocytic neoplasms are classified as melanocytosis, melanocytomas, melanoma and melanosis. Limas and Tito reported the first case of spinal melanocytomas in 1972 [6]. Because of its rare incidence and variable pres entation, the diagnosis and therapy of melanocytomas may be neglected or overlooked. Melanocytoma is generally a benign lesion, and melanoma is a malignant lesion, but contrary to the malignant lesion, melanocytoma has a lower incidence [7]. The pathogenesis of CNS primary melanocytomas remains unknown so far. Rajmohan et al. believed that mutations in GNAQ and GNA11 play a role in melanocytic lesions [8]. Shanthi et al. reported that the tumor occurs commonly in the fifth decade and with higher incidence in females than males clinically [9]. It usually occurs in the thoracic spine and infratentorial region [10], such as the area of the cerebellopontine angle [11]. Lin et al. reported that melanocytoma also can be located in the anterior cranial fossa [12].

The diagnosis of melanocytoma needs to take a comprehensive consideration of clinical manifestations, imaging manifestations and postoperative pathology. The common clinical manifestations of spinal melanocytomas include spinal cord segmental nerve function surgery, including hypothyroidism and motor dysfunction, which can lead to severe limb paralysis [6]. The imaging findings of melanocytomas were as follows: On CT, a nonspecific appearance was seen similar to meningioma, with clear margin and homogeneous enhancement. But on MRI, the signal intensity of melanocytomas is closely related to the quantity of melanin. Only when it is shown that the mass is uniform with hyperintense on T1-weighted imaging and hypointense on T2-weighted imaging, the diagnosis of melanocytoma can probably be established.

Immunohistochemically, compared with other antibodies, HMB45 and S-100, Ki-67 are sensitive antibody for melanocytic lesions, and are usually strongly positive [13,14].

There is still a lack of standard treatment for melanocytomas. Urrets-Zavalia et al. proposed that bevacizumab can also be used in treatment for melanocytoma [15]. Because melanocytoma is a malignant lesion, surgical resection is considered the best treatment.

Disclosure of conflict of interest

None.

References

- 1.Wagner F, Berezowska S, Wiest R, Gralla J, Beck J, Verma RK, Huber A. Primary intramedullary melanocytomas in the cervical spinal cord: case report and literature review. Radiol Case Rep. 2015;10:1010. doi: 10.2484/rcr.v10i1.1010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Erdei E, Torres SM. A new understanding in the epidemiology of melanoma. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther. 2010;10:1811–23. doi: 10.1586/era.10.170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gallego-Pinazo R, Dolz-Marco R, Vila-Arteaga J, Marí Cotino JF, España-Gregori E. Optic nerve melanocytomas. Arch Soc Esp Oftalmol. 2016;91:e83. doi: 10.1016/j.oftal.2016.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Moscarella E, Ricci R, Argenziano G, Lallas A, Longo C, Lombardi M, Alfano R, Ferrara G. Pigmented epithelioid melanocytomas: clinical, dermoscopic and histopathological features. Br J Dermatol. 2016;174:1115–7. doi: 10.1111/bjd.14322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rades D, Heidenreich F, Tatagiba M, Brandis A, Karstens JH. Therapeutic options for meningeal melanocytomas. Case report. J Neurosurg. 2001;95(Suppl):225–31. doi: 10.3171/spi.2001.95.2.0225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sen R, Sethi D, Goyal V, Duhan A, Modi S. Spinal meningeal melanocytomas. Asian J Neurosurg. 2011;6:110–112. doi: 10.4103/1793-5482.92176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sen R, Sethi D, Goyal V, Duhan A, Modi S. Spinal meningeal melanocytomas. Asian J Neurosurg. 2011;6:110–112. doi: 10.4103/1793-5482.92176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Murali R, Wiesner T, Rosenblum MK, Bastian BC. GNAQ and GNA11 mutations in melanocytomas of the central nervous system. Acta Neuropathol. 2012;123:457–459. doi: 10.1007/s00401-012-0948-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shanthi V, Ramakrishna BA, Bheemaraju VV, Rao NM, Athota VR. Spinal meningeal melanocytomas: a rare meningeal tumor. Ann Indian Acad Neurol. 2010;13:308–310. doi: 10.4103/0972-2327.74192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dorwal P, Mohapatra I, Gautam D, Gupta A. Intramedullary melanocytomas of thoracic spine: a rare case report. Asian J Neurosurg. 2014;9:36–39. doi: 10.4103/1793-5482.131068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Phang I, Elashaal R, Ironside J, Eljamel S. Primary cerebellopontine angle melanocytomas: review. J Neurol Surg Rep. 2012;73:25–31. doi: 10.1055/s-0032-1311756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lin B, Yang H, Qu L, Li Y, Yu J. Primary meningeal melanocytomas of the anterior cranial fossa: a case report and review of the literature. World J Surg Oncol. 2012;10:135. doi: 10.1186/1477-7819-10-135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Clarkson K, Sturdgess I, Molyneux A. The usefulness of tyrosinase in the immunohistochemical assessment of melanocytic lesions: a comparison of the novel T311 antibody (anti-tyrosinase) with S-100, HMB45, and A103 (anti-melan-A) J Clin Pathol. 2001;54:196–200. doi: 10.1136/jcp.54.3.196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Uguen A, Talagas M, Costa S, Duigou S, Bouvier S, De Braekeleer M, Marcorelles P. A p16-Ki-67-HMB45 immunohistochemistry scoring system as an ancillary diagnostic tool in the diagnosis of melanoma. Diagn Pathol. 2015;10:195. doi: 10.1186/s13000-015-0431-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Urrets-Zavalia JA, Crim N, Esposito E, Correa L, Gonzalez-Castellanos ME, Martinez D. Bevacizumab for the treatment of a complicated posterior melanocytomas. Clin Ophthalmol. 2015;9:455–459. doi: 10.2147/OPTH.S80152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]