Abstract

Although prior studies showed that patients with cirrhosis have a lower risk of developing liver metastases, appropriate workup of incidental liver masses in cirrhotic liver is important for a correct diagnosis. Here we present a case of newly diagnosed liver cirrhosis with multifocal hepatic lesions, which was initially categorized as a LI-RADS (Liver Imaging Reporting and Data System) 5 lesions. Scintigraphy with 111In-pentetreotide (Octreoscan) indicated a suspected thyroid nodule, later confirmed to represent medullary thyroid carcinoma lesion. The most relevant imaging finding of this rare form of thyroid malignancy is reviewed in this presentation.

Keywords: LI-RADS, octreoscan, cirrhosis, hepatocellular carcinoma, medullary thyroid cancer

Medullary thyroid carcinoma is a neuroendocrine tumor originating from the parafolicullar cells (C cells). The most relevant imaging finding of this rare form of thyroid malignancy is reviewed in this presentation.

CASE REPORT

A 54-y-old woman, with history of alcohol abuse, was referred to the liver tumor clinic after a routine physical examination showing elevated liver enzymes (aspartate aminotransferase 86 U/L; alanine aminotransferase 46 U/L; alkaline phosphatase 325 U/L) and an abdominal ultrasound with evidence of cirrhosis, portal hypertension, and liver lesions. The patient denied any abdominal pain, weight loss, nausea, or diarrhea.

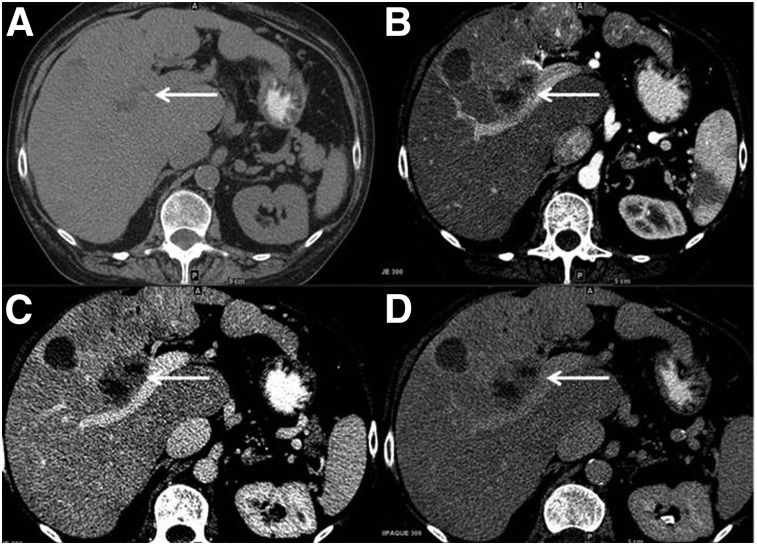

Multiphasic contrast CT study (Fig. 1) showed multifocal liver lesions with partial necrosis. For instance, a 3.1-cm mildly heterogeneous segment-5 lesion demonstrated arterial enhancement in the late arterial phase and washout in the portal-venous phase and delayed phase. This satisfied the Liver Imaging Reporting and Data System (LI-RADS) 5 criteria suggestive of a diagnosis of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). Additional labwork showed normal α-fetoprotein level, high carcinoembryonic antigen (7,113.5 ng/mL), CA19-9 (93 U/mL), and chromogranin A (915 ng/mL) levels. Core liver biopsy showed neuroendocrine carcinoma of unknown primary site and cirrhosis. Upper and lower endoscopies were negative.

FIGURE 1.

Multiphasic contrast CT study shows multifocal liver lesions with partial necrosis. (A) A 3.1-cm mildly heterogeneous segment-5 lesion seen on noncontrast axial CT demonstrates minimal arterial enhancement seen in late arterial phase (B) with washout and subtle capsule seen in the portal-venous (C) and delayed phases (D).

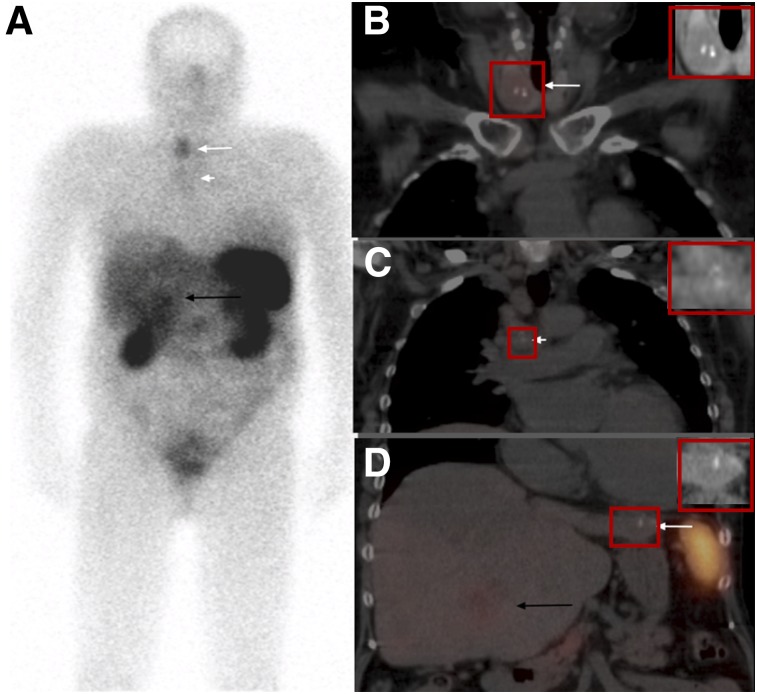

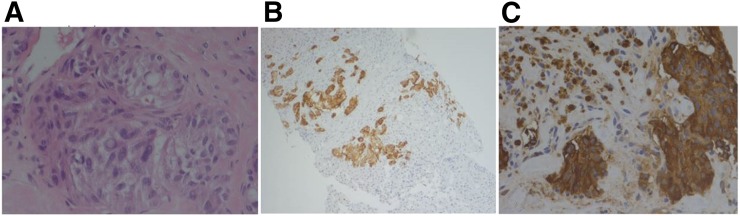

Subsequent 111In-pentetreotide study (Fig. 2) demonstrated prominent focal uptake in a heterogeneous thyroid nodule with dense, coarse calcifications within; mild uptake in mediastinal lymph nodes (also containing dense calcifications); and heterogeneous liver uptake more prominent in one of the segment-5 lesions. There was also a coarse calcification seen in one of the liver lesions. Given 111In-pentetreotide scan findings, metastatic medullary thyroid cancer was suspected. Additional immunohistochemistry performed on the previously obtained core liver biopsy showed that the neoplastic cells were positive for thyroid transcription factor-1 and calcitonin, consistent with metastatic medullary thyroid carcinoma. Cytologic impression for right thyroid nodule fine-needle aspiration showed medullary thyroid cancer (Fig. 3). The patient tested negative for RET gene mutation (usually associated with multiple endocrine neoplasia type 2).

FIGURE 2.

111In-pentetreotide scan identifies focal uptake in thyroid nodule. (A) Whole-body images (anterior view) show uptake in right thyroid nodule (long white arrow), mild uptake in mediastinal lymph nodes (short white arrow), and heterogeneous liver uptake more prominent in segment-5 lesion (black arrow). (B–D) Fused coronal SPECT/CT images show focal thyroid uptake corresponding to a heterogeneous low attenuation thyroid nodule with dense, coarse calcifications within (arrow in B), mild uptake in mediastinal lymph nodes also containing dense calcifications (arrow in C), and heterogeneous liver uptake due to multiple liver lesions more prominent within one of the lesions in segment 5 (black arrow in D). Small calcification in left lobe of the liver lesion is also seen (white arrow on image D).

FIGURE 3.

Histopathologic examination of core liver biopsy (A) shows liver parenchyma largely replaced by neoplastic cells infiltrating in nests and single cells with epithelioid to spindled morphology. Cytologic features include variation in nuclear size and shape with stippled chromatin, intranuclear inclusions, relatively low mitotic rate, and necrosis. Immunostains were positive for chromogranin (B) and calcitonin (C) secretion, consistent with metastatic medullary thyroid carcinoma. Nonneoplastic liver biopsy (not shown) was remarkable for fibrosis and nodularity suggestive of cirrhosis and negative for increased iron. Cytologic impression for fine-needle aspiration of right thyroid nodule also showed medullary thyroid cancer.

DISCUSSION

Medullary thyroid carcinoma is a neuroendocrine tumor of the parafollicular cells (C cells), which secrete calcitonin and also carcinoembryonic antigen. Somatostatin receptor scintigraphy is an important tool in staging of neuroendocrine tumors; however, regarding liver lesions seen in this case, the study could not differentiate between neuroendocrine tumors and HCC given that previously published studies showed that in advanced HCC cases, 111In-pentetreotide study can also be positive.

Several studies indicate that cirrhotic liver reduces the risk of hepatic metastases (1). LI-RADS categories reflect estimated probability for a lesion to be HCC (2). Hypervascularity in the late arterial phase and rapid washout in the portal-venous phase and especially in the delayed phase satisfy the LI-RADS 5 criteria for diagnosis of HCC and give a good sensitivity for HCC detection. However, recent studies showed that an interpreter is more likely to perceive washout in a nodule with a capsule than a nodule without a capsule, despite the absence of objective evidence of washout or significant arterial enhancement (3).

Metastases from neuroendocrine tumor are hypervascular and commonly show washout and can be assigned as LI-RAD 5, resulting in a false-positive diagnosis of HCC. Therefore, attention to any atypical features is important in correct classification of these lesions. In the current case, there was only mild arterial enhancement. Also, the presence of calcification, which is relatively infrequent in nonfibrolamellar HCC, might have been a clue that this was not a typical case of HCC and that the lesions must have been categorized as LI-RADS M. There were coarse calcifications with a similar morphology in a thyroid nodule and in several mediastinal lymph nodes, which were also initially overlooked. Coarse calcifications are less specific for malignancy compared with microcalcifications and can be seen in multinodular goiter secondary to dystrophic calcifications in benign thyroid nodules; however, when present in a solitary thyroid nodule they carry a higher risk of being malignant. Dense and irregular coarse thyroid calcifications may coexist with microcalcifications in papillary thyroid cancer (which only in exceedingly rare cases metastasize to the liver), and they are the most common type of calcifications in medullary thyroid carcinomas (4). Incidence of calcified metastasis in the mediastinal lymph nodes, liver, and lung at the initial presentation has been described in patients with medullary thyroid carcinomas, and this feature needs not to be confused with granulomatous disease when searching for a neuroendocrine primary site (5).

CONCLUSION

Although prior studies showed that patients with cirrhosis have a lower risk of developing liver metastases, appropriate workup of incidental liver masses in cirrhotic liver is important for a correct diagnosis. If metastases from neuroendocrine tumors are suspected, molecular imaging using somatostatin receptor scintigraphy represents an important diagnostic tool for detection of the primary lesion, for staging and restaging of these patients.

DISCLOSURE

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

REFERENCES

- 1.Dahl E, Rumessen J, Gluud LL. Systematic review with meta-analyses of studies on the association between cirrhosis and liver metastases. Hepatol Res. 2011;41:618–625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shah A, Tang A, Santillan C, et al. Cirrhotic liver: what’s that nodule? The LI-RADS approach. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2016;43:281–294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sofue K, Sirlin CB, Allen BC, et al. How reader perception of capsule affects interpretation of washout in hypervascular liver nodules in patients at risk for hepatocellular carcinoma. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2016;43:1337–1345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hoang JK, Lee WK, Lee M, et al. US features of thyroid malignancy: pearls and pitfalls. Radiographics. 2007;27:847–860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ganeshan D, Paulson E, Duran C, et al. Current update on medullary thyroid carcinoma. AJR. 2013;201:W867–W876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]