Acute esophageal perforations are traditionally managed surgically, although minimally invasive approaches, including esophageal clipping, stent placement, suturing, and endoluminal vacuum therapy (EndoVAC), have been reported.1, 2, 3 The EndoVAC approach, which relies on a modification of the wound-VAC technique, has been used to treat esophageal perforations and leaks with success.4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9 These cases, often reported in the surgical literature, have demonstrated healing of the perforation or leak while avoiding the morbidity and mortality associated with surgery.4 Although clips, stent placement, and suturing are often considered as initial options for treating esophageal perforations, their role can be limited, with large perforations not amenable to clipping or not adequately covered with stent placement (secretions, debris, and food may leak “around” the stent into the perforation); additionally, suturing is dependent on local expertise.

The EndoVAC technique was initially developed by Weidenhagen et al10 to treat anastomotic leaks after rectal surgery. The EndoVAC assembly involves modification of the traditional woundVAC equipment (KCI, San Antonio, Tex, USA). The woundVAC sponge is cut to a size that matches the perforation and is then attached to a nasogastric tube before being placed adjacent to or within the perforation. The EndoVAC sponge is replaced frequently and facilitates healing over a 2-week to 3-week period depending on the size of the perforation. In this case, we demonstrate its success in treating a patient who was critically ill from Boerhaave syndrome. EndoVAC therapy to treat esophageal perforation is best performed as part of a multidisciplinary team, with cardiothoracic surgery and gastroenterology services working together to ensure adequate response to therapy. Alternative nutrition is generally provided by a percutaneous gastric or gastrojejunal tube. Some patients who are doing well clinically while tolerating percutaneous feeding may be discharged home, with repeated visits to the endoscopy suite for EndoVAC exchanges.

The major advantages of EndoVAC therapy are avoidance of the morbidity and mortality associated with surgery. Given the endoscopic placement of this device, gastroenterologists are ideally prepared to assemble and place the EndoVAC. In this video, we describe the steps involved in assembling and placing the EndoVAC device (Video 1, available online at www.VideoGIE.org).

Case Report

A 49-year-old man with a history of alcohol abuse presented because of a concern for esophageal rupture. After heavy alcohol consumption and associated vomiting, he experienced severe retrosternal chest pain. He was found by emergency medical personnel to have severe dyspnea. Upon his arrival at the hospital, a chest radiograph showed a small left pneumothorax. In the setting of continued respiratory distress, he was intubated and admitted to the medical intensive care unit. An interval chest radiograph showed an enlarging left pneumothorax with subcutaneous emphysema, and a chest tube was placed. Given the need for a higher level of care and a concern for Boerhaave syndrome, he was life-flighted to our tertiary care medical center approximately 40 hours after the start of his symptoms. On arrival, he was hypotensive, requiring vasopressor support, which was concerning for septic shock.

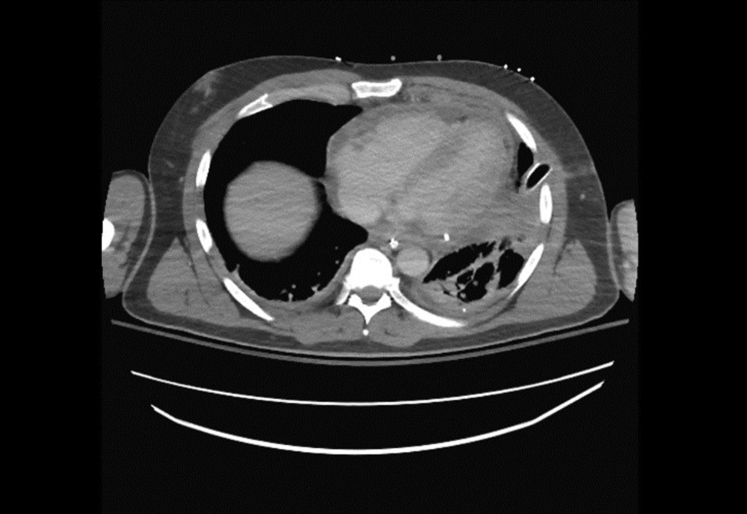

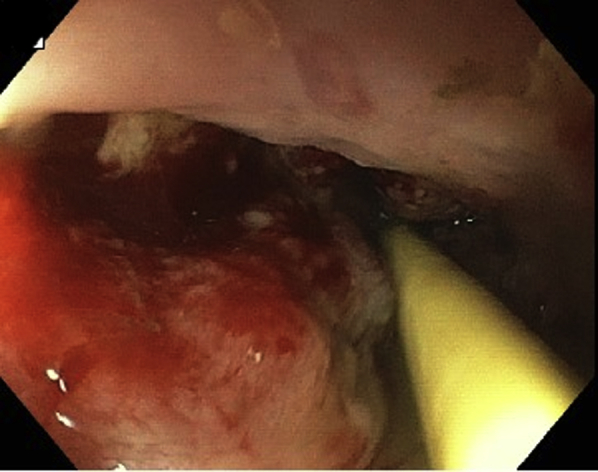

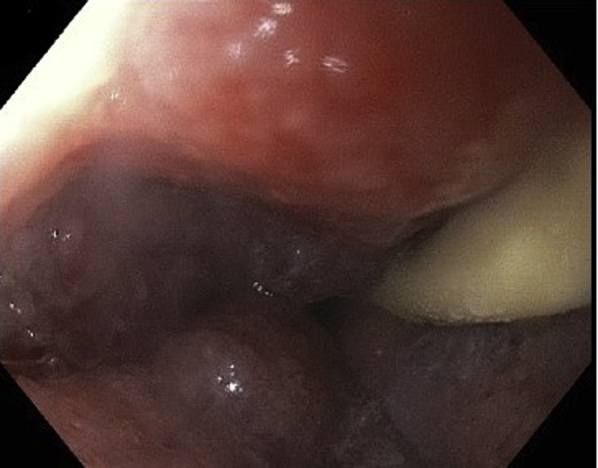

CT of the chest with oral contrast material through the nasogastric tube (Fig. 1) confirmed the diagnosis of esophageal perforation. EGD identified an approximately 3-cm linear perforation in the distal esophagus (Fig. 2). Given his presentation >24 hours since the initial event and his unstable clinical status, the decision was made to proceed with EndoVac therapy of his esophageal perforation.

Figure 1.

CT of chest showing esophageal perforation just proximal to the gastroesophageal junction with extravasation of contrast material into the mediastinum.

Figure 2.

EGD view showing 3-cm linear perforation at 39 to 41 cm, and a nasogastric feeding tube.

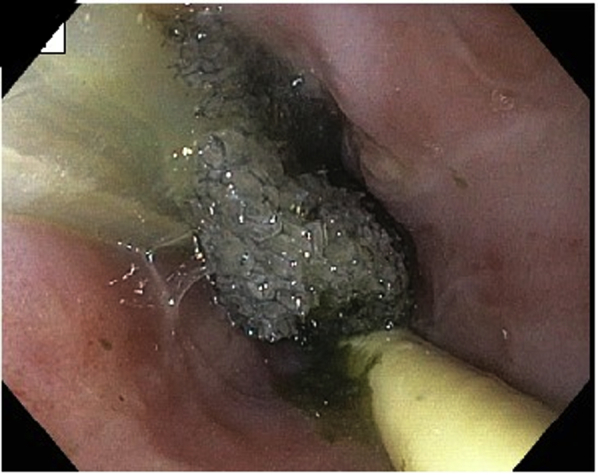

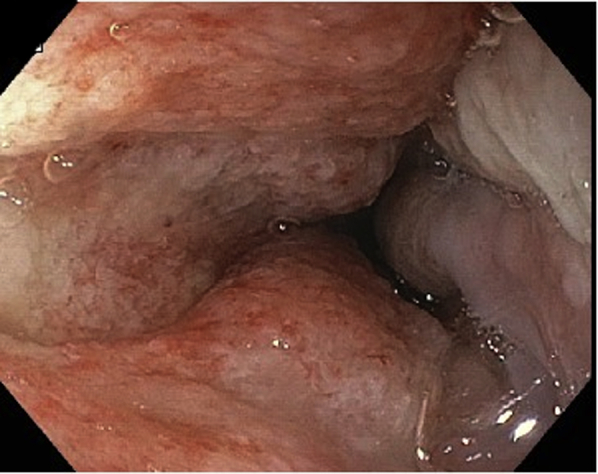

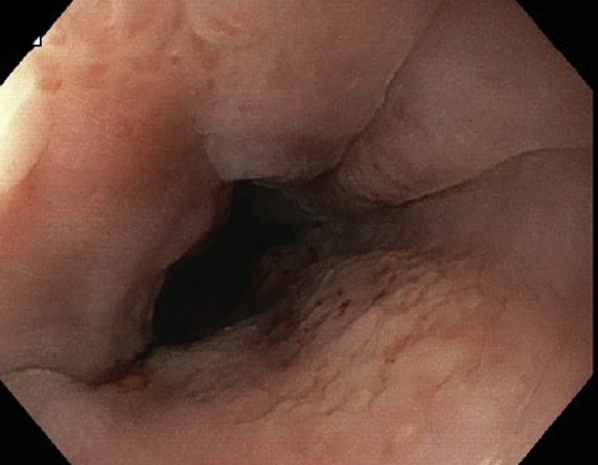

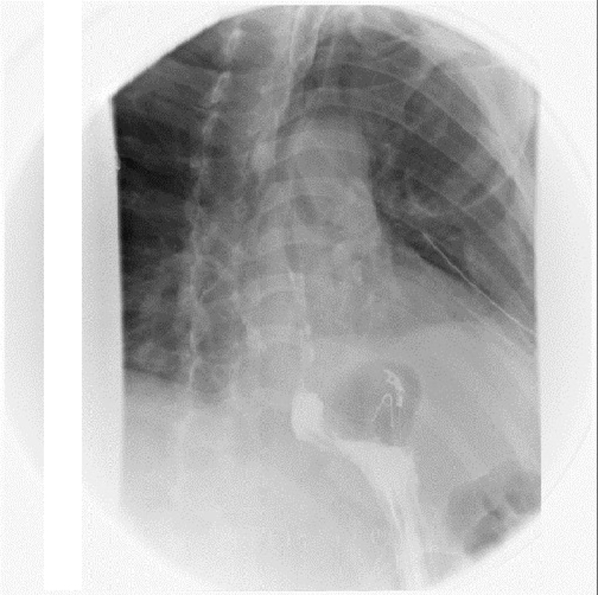

The EndoVAC procedure was repeated every 3 to 4 days (Fig. 3) for a total of 6 EndoVAC sessions over 3 weeks. During this time, the patient was given nothing by mouth and was fed through a Dobhoff tube and then PEG-J. Granulation tissue was noticed during placement of the fourth EndoVAC (Fig. 4). Follow-up EGDs (Figs. 5 and 6), chest CT (Fig. 7), and barium swallow (Fig. 8) confirmed complete healing of the esophageal perforation.

Figure 3.

EGD view showing placement of the EndoVAC; nasogastric feeding tube remains in place.

Figure 4.

EGD view showing granulation tissue, fourth EndoVAC; nasogastric feeding tube remains in place.

Figure 5.

EGD view at 3 weeks showing healthy granulation tissue at site of previous perforation; nasogastric feeding tube has been replaced by gastrojejunal feeding tube.

Figure 6.

EGD view showing healed esophageal perforation.

Figure 7.

CT of chest showing no leakage of contrast material.

Figure 8.

Barium swallow showing no leakage of contrast material.

Acknowledgement

Supported by a Robert W. Summers grant from the American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy.

Disclosure

All authors disclosed no financial relationships relevant to this publication.

Footnotes

If you would like to chat with an author of this article, you may contact Dr Ketwaroo at gyanprakash.ketwaroo@bcm.edu.

Supplementary data

EndoVAC therapy of acute esophageal perforation.

References

- 1.Brangewitz M., Voigtländer T., Helfritz F.A. Endoscopic closure of esophageal intrathoracic leaks: stent versus endoscopic vacuum-assisted closure: a retrospective analysis. Endoscopy. 2013;45:433–438. doi: 10.1055/s-0032-1326435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Biancari F., D’Andrea V., Paone R. Current treatment and outcome of esophageal perforations in adults: systematic review and meta-analysis of 75 studies. World J Surg. 2013;37:1051–1059. doi: 10.1007/s00268-013-1951-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chen A., Kim R. Boerhaave syndrome treated with endoscopic suturing. VideoGIE. 2019;4:118–119. doi: 10.1016/j.vgie.2018.12.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Leeds S.G., Burdick J.S., Fleshman J.W. Endoluminal vacuum therapy for esophageal and upper intestinal anastomotic leaks. JAMA Surg. 2016;151:573–574. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2016.0255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Heits N., Stapel L., Reichert B. Endoscopic endoluminal vacuum therapy in esophageal perforation. Ann Thorac Surg. 2014;97:1029–1035. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2013.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Still S., Mencio M., Ontiveros E. Primary and rescue endoluminal vacuum therapy in the management of esophageal perforations and leaks. Ann Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2018;20:173–179. doi: 10.5761/atcs.oa.17-00107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.de Moura D.T.H., Brunaldi V.O., Minata M. Endoscopic vacuum therapy for a large esophageal perforation after bariatric stent placement. VideoGIE. 2018;3:346–348. doi: 10.1016/j.vgie.2018.08.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mennigen R., Senninger N., Laukoetter M.G. Endoscopic vacuum therapy of esophageal anastomotic leakage. Gastrointest Endosc. 2015;82:397. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2015.02.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Watson A., Zuchelli T. Repair of upper-GI fistulas and anastomotic leakage by the use of endoluminal vacuum-assisted closure. VideoGIE. 2019;4:40–44. doi: 10.1016/j.vgie.2018.09.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Weidenhagen R., Spelsberg F., Lang R.A. New method for sepsis control caused by anastomotic leakage in rectal surgery: the Endo-VAC. Colorectal Dis. 2003;5:1–4. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

EndoVAC therapy of acute esophageal perforation.