Abstract

Introduction:

At present, the main treatment of gastric cancer is surgical resection combined with radiotherapy and chemotherapy, the most important part of which is radical gastrectomy. Laparoscopic radical gastrectomy for advanced gastric cancer is difficult to operate, and whether it can achieve the same curative effect with the laparotomy is still controversial.

Materials and Methods:

This study retrospectively analysed the clinical data of 269 gastric cancer patients surgically treated by our medical team from May 2011 to December 2015 for comparative analysis of the clinical efficacy of laparoscopic-assisted radical gastrectomy and traditional open radical gastrectomy.

Results:

The laparoscopic surgery group had longer duration of surgery, less intra-operative blood loss, shorter post-operative exhaust time, shorter post-operative hospital stay and shorter timing of drain removal. The average number of harvested lymph nodes in the laparoscopic surgery group was 22.9 ± 9.5 per case. And in the laparotomy group the average number was 23.3 ± 9.9 per case. The difference had no statistical significance. With the increase of the number of laparoscopic surgical procedures, the amount of intra-operative blood loss gradually decreases, and the duration of surgery is gradually reduced.

Conclusion:

Laparoscopic radical gastrectomy is superior to open surgery in the aspects of intra-operative blood loss, post-operative exhaust time, post-operative hospital stay and timing of drain removal. With the number of laparoscopic radical gastrectomy cases increased, the duration of surgery is shortened and the amount of intra-operative blood loss will decrease.

Keywords: Gastric cancer, laparoscopic surgery, learning curves

INTRODUCTION

Gastric cancer is the fourth highest incidence among all the malignant tumours, and it is the second cause of death from cancer.[1] At present, the main treatment of gastric cancer is surgical resection combined with radiotherapy and chemotherapy, the most important part of which is radical gastrectomy (D2).[2] In 1991, Goh et al. reported the first laparoscopic-assisted distal gastrectomy, and in 1997, Goh et al. reported laparoscopic-assisted radical gastrectomy (D2) for advanced gastric cancer.[3] After >10 years of development, laparoscopic surgery of gastric cancer is becoming increasingly diverse, surpassing the common type of traditional surgery.[4] Laparoscopic radical gastrectomy for advanced gastric cancer is difficult to operate, and whether it can achieve the same curative effect with the laparotomy is still controversial.[5,6] This study retrospectively analysed the clinical data of 269 gastric cancer patients surgically treated by our medical team from May 2011 to December 2015 for comparative analysis of the clinical efficacy of laparoscopic-assisted radical gastrectomy and traditional open radical gastrectomy.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Clinical data

We collected the clinical data of patients with advanced gastric cancer who underwent D2 radical gastrectomy in our medical team from May 2011 to December 2015. The operations were completed by the same surgeon.

Exclusion criteria

Advanced tumour with local infiltration or non-radical surgery because of distant metastasis

Multiple organ resection or conversion from laparoscopic surgery to open approach

Pre-operative chemotherapy or immunotherapy

Re-operation due to tumour recurrence or remnant gastric cancer.

Surgical method

Laparotomy patients were prepared in the supine position, and upper abdominal midline incision about 15 cm was used.[7] Patients who underwent laparoscopic surgery were placed in the supine position with the legs apart. The surgeon stood on the patient's left side, with the first assistant on the patient's right and the camera operator between the patient's legs. After division of ligaments and dissection of lymph nodes (LNs), an upper abdominal midline incision about 6 cm was used for specimen removal and gastrointestinal reconstruction.

Laparoscopic surgery group

The patient, under general anaesthesia, was prepared in the supine position with the legs apart. The peritoneal cavity was insufflated with CO2 at a pressure of 10–12 mmHg before five trocars of 5–12 mm in diameter were introduced. The diameters and positions of the trocars are as follows: 10 mm in the umbilicus, through which a laparoscope is introduced, 12 mm at left mid-axillary line below the costal margin, 5 mm at left mid-clavicular line at the umbilicus, 5 mm at right mid-clavicular line below the costal margin and 10 mm at right mid-clavicular line 2–3 cm above the umbilicus. All trocars are inserted at a handbreadth distance between them to avoid interference of the laparoscopic instruments. The surgical approach is determined after abdominal exploration. In laparoscopic distal gastrectomy, the greater omentum is divided in the avascular area starting from the superior border of the transverse colon near its midpoint using the ultrasonic scalpel. The division is extended toward the right until reaching the hepatic flexure and then toward the left to reach the splenic flexure. Superior mesenteric vein (SMV), right colic vein, right gastroepiploic vein (RGEV) and the Henle's trunk are exposed. The dissection of No. 14v LNs is accomplished by removing the fatty lymphatic tissue around Henle's trunk and the SMV. After severing RGEV and right gastroepiploic artery at the root, the lymphatic and fatty tissue in the infra-pyloric area is dissected and removed en bloc. The No. 6 LNs are then dissected. After severing the left gastroepiploic vessels at the root, the No. 4sb LNs and the No. 4d LNs are dissected. The splenic artery is exposed before the dissection of the No. 11p LNs. After the exposure of the common hepatic artery and the celiac trunk, the No. 7 LNs lying around the left gastric vessels in the gastropancreatic fold outside the lesser omentum are dissected, the No. 8 LNs are removed from the anterosuperior and posterior sides of the common hepatic artery and then the No. 9 LNs located at the roots of the left gastric artery, common hepatic artery and splenic artery around the celiac artery are also dissected. The No. 8a LNs located anterosuperior to the common hepatic artery are also dissected and the No. 12a LNs are cleared after the exposure of the right gastric artery and the proper hepatic artery. The right gastric artery is severed at the root. The No. 1 LNs and the No. 3 LNs are dissected after the separation of the gastric lesser curvature. At this point, laparoscopic instruments are withdrawn, and upper abdominal midline incision about 6 cm is used for the procedure of Billroth I or Billroth II anastomosis.

For laparoscopic proximal gastrectomy, the pre-operative preparation and anaesthesia methods are the same as stated above. The greater and the lesser curvature sides of the stomach are fully dissociated, during which the left gastric vessels, left gastroepiploic vessels and gastric short blood vessels are severed. Moreover, the No. 1, 2, 3, 4sa, 4sb, 7, 8a, 9, 10, 11 and 12a LNs are dissected. The oesophagus is mobilised up to about 5 cm. After withdrawing the laparoscopic instruments, an upper abdominal midline incision about 6 cm is used for oesophagogastric anastomosis.

For laparoscopic total gastrectomy, the pre-operative preparation and anaesthesia methods are the same as stated above. The greater and the lesser curvature sides of the stomach are fully dissociated, and the right and left gastroepiploic vessels, gastric short blood vessels as well as the right and left gastric vessels are severed at the root, during which the dissection of the No. 1, 2, 3, 4sa, 4sb, 4d, 5, 6, 7, 8a, 9, 10, 11p, 11d, 12a and 14v LNs is accomplished. The oesophagus is mobilised up to about 5 cm. After withdrawing the laparoscopic instruments, an upper abdominal midline incision about 6 cm is used for the transection of the duodenum and the oesophagus, and then, a Roux-en-Y anastomosis between oesophagus and jejunum is performed. The nasogastric tube is placed in the jejunal afferent loop while the nasointestinal tube is placed in the jejunum distal to the stoma site.

Laparotomy group

The patient, in general anaesthesia, is placed in the supine position with legs separated. An upper abdominal midline incision about 15 cm is used for the whole procedure. For radical distal gastrectomy, the greater and the lesser curvature sides of the stomach are fully dissociated while the corresponding blood vessels are severed, and the No. 1, 3, 4d, 4sb, 5, 6, 7, 8a, 9, 10, 11p, 12a and 14v LNs are dissected. After the transection of the duodenum and stomach, conventional Billroth I or Billroth II anastomosis is performed.

For radical proximal gastrectomy, the greater and the lesser curvature sides of the stomach are fully dissociated, and the corresponding blood vessels are severed, during which the No. 1, 2, 3, 4sa, 4sb, 7, 8a, 9, 10, 11 and 12a LNs are dissected. Moreover, oesophagogastric anastomosis is performed after the transection of the oesophagus and stomach.

For total gastrectomy, the corresponding blood vessels are severed during the dissociation of the greater and the lesser curvature sides of the stomach, and the No. 1, 2, 3, 4sa, 4sb, 4d, 5, 6, 7, 8a, 9, 10, 11p, 11d, 12a and 14v LNs are dissected. After the transection of the duodenum and the oesophagus, a Roux-en-Y anastomosis between oesophagus and jejunum is performed.

Observed indicators

All the patients started drinking water after anal exhaust. Moreover, the patients were discharged when they could intake liquid diet and all the blood indexes reached in the range of normal level. The following indicators were observed: operation time, intra-operative blood loss, the number of LNs dissected, gastrointestinal function recovery time, drainage tube removal time, post-operative hospital stay, post-operative complications (duodenal stump fistula, anastomotic leakage, post-operative bleeding, obstructive complications, traumatic pancreatitis, acute cholecystitis, incision-related complications, pulmonary-related complications, etc.).[8]

Statistical analysis

All analyses were conducted with Statistical Package for the Social Sciences software, version 19.0 (IBM, Armonk, New York, USA). Measurement data were expressed as mean ± standard deviation and analysed using independent samples t- test. The Chi-square test was applied to compare qualitative data. A P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

According to the statistical results, there was no significant difference in sex, age, body mass index, anastomosis and tumour stage among the patients in the two groups (P > 0.05) [Table 1]. Compared to the laparotomy group, the laparoscopic surgery group had longer duration of surgery (P < 0.05), less intra-operative blood loss (P < 0.05), shorter post-operative exhaust time (P < 0.05), shorter post-operative hospital stay (P < 0.05) and shorter timing of drain removal (P < 0.05). The average number of harvested lymph nodes in the laparoscopic surgery group was 22.9 ± 9.5 per case. And in the laparotomy group the average number was 23.3 ± 9.9 per case. The difference had no statistical significance (P > 0.05) [Table 2].

Table 1.

The comparative patient information of laparoscopic radical gastrectomy and open radical gastrectomy

| Groups | Gender | Age | BMI | Anastomosis | Tumor stage | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | Female | Distal | Total | Proximal | I | II | III | |||

| Laparotomy group | 113 | 33 | 61.1±10.2 | 25.5±2.5 | 62 | 74 | 10 | 17 | 16 | 113 |

| Laparoscopic surgery group | 92 | 31 | 58.9±10.6 | 25.7±2.4 | 63 | 51 | 9 | 45 | 21 | 57 |

| P | 0.668 | 0.082 | 0.327 | 0.31 | P>0.05 | |||||

BMI: Body mass index

Table 2.

The clinical data of laparoscopic radical gastrectomy and open radical gastrectomy

| Parameters | Laparotomy group | Laparoscopic surgery group | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Duration of surgery (min) | 235±47 | 285±59 | <0.05 |

| Intra-operative blood loss (ml) | 146±43 | 94±48 | <0.05 |

| Post-operative exhaust time (day) | 3.8±0.8 | 2.4±0.8 | <0.05 |

| Post-operative hospital stay (day) | 18±8 | 15±6 | <0.05 |

| Timing of drain removal (day) | 11.6±2.5 | 10.2±1.9 | <0.05 |

| Number of harvested LNs |

23.3±9.9 | 22.9±9.5 | >0.05 |

LNs: Lymph nodes

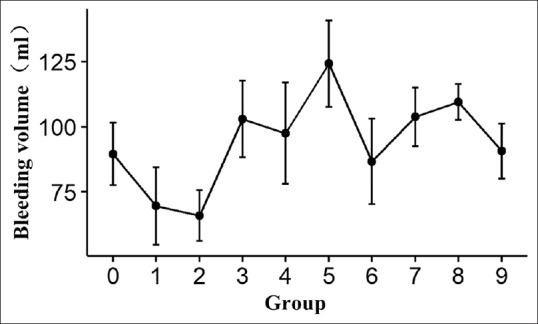

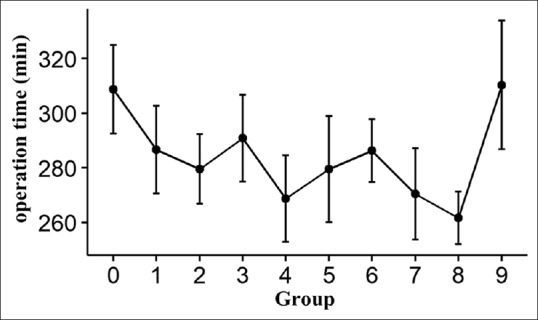

Figures 1 and 2 reveal the trends of changes in intra-operative blood loss and duration of surgery in the laparoscopic surgery group. With the increase of the number of laparoscopic surgical procedures, the amount of intra-operative blood loss gradually decreases, and the duration of surgery is gradually reduced.

Figure 1.

The trends of changes in intra-operative blood loss

Figure 2.

The trends of duration of surgery in the laparoscopic surgery group

DISCUSSION

At present, surgery is still the most effective means of treating gastric cancer.[9] With the development of minimally invasive technique, laparoscopic radical gastrectomy has been widely used in the treatment of early gastric cancer and achieved a good therapeutic effect.[10] Japanese gastric cancer treatment guidelines 2014 (ver. 4) has clearly defined that for patients with Stage Ic gastric cancer suitable for distal gastrectomy, laparoscopic surgery can be used as a routine treatment option.[11] Traditional laparotomy has a high incidence of complications, high mortality and varying degrees of decline in quality of life. Therefore, any treatment that can improve these deficiencies may provide a better treatment option for gastric cancer. Currently, the application of minimally invasive technique in treating gastric cancer mainly includes two aspects: endoscopic resection of tumour and laparoscopic surgery.[12] Endoscopic mucosal resection has been recommended by the National Comprehensive Cancer Network Guidelines as a standard treatment for some early gastric cancer;[13] the application of endoscopic submucosal dissection made endoscopic treatment of larger intra-mucosal carcinoma possible.[14] However, most of the gastric cancer cases in China have already reached an advanced stage when initially diagnose.[15] Considering the limitations of the patient population, laparoscopic surgery undoubtedly has a more extensive application prospects.[16] A number of randomised controlled trials have confirmed the reliability and safety of this surgical approach in the treatment of early gastric cancer.[17,18] Although the treatment of advanced gastric cancer with laparoscopic minimally invasive surgery is still controversial, one needs to overcome huge surgical challenges, especially when the tumour volume is large or the tumour has involved multiple organs.[19] However, the results of the existing study confirmed that in the treatment of local advanced gastric cancer, laparoscopic-assisted radical gastrectomy has a safe and reliable short-term efficacy, and its post-operative survival rate was not significantly different from that of traditional open surgery.[20,21] This study shows that laparoscopic radical gastrectomy is superior to open surgery in the aspects of intra-operative blood loss, post-operative exhaust time, post-operative hospital stay and timing of drain removal. As for LN dissection, there is no significant difference between the two surgical methods.

As the development trend of surgery in the future, more and more gastrointestinal surgeons seek to master laparoscopic surgery technique for gastric cancer.[22] Learning curve refers to the relationship between technical experience and outcome variables in the course of developing new surgery.[23,24] After a certain amount of surgical practice, the efficacy of the surgery is significantly improved compared to the initial stage of learning and the surgeon masters the operation technique and that is when the learning curve is completed. Like other laparoscopic surgeries, one must experience a rather difficult learning curve process to gradually master the technical essentials of laparoscopic gastrectomy.[25,26] Unlike laparoscopic colorectal surgery, laparoscopic radical gastrectomy is more complicated technically due to the complexity of the anatomical structure around the stomach, and more surgical experience is needed to accomplish the learning curve.[27,28] Kim et al. and Jin et al. reported, respectively, that the learning curve of laparoscopic surgery for gastric cancer is 50 cases and 40 cases, and the learning curve of laparoscopic gastric bypass surgery for morbid obesity is 100 cases.[29,30]

This study shows that duration of laparoscopic surgery, which is longer than that of open surgery, can be shortened gradually with the richening of surgical experience and the improvement of instruments and equipment. In our study, intra-operative blood loss in laparoscopic surgery group increased initially and then decreased with the increase of the number of cases, which indicates that intra-operative blood loss will decrease with the richening of surgical experience. When it comes to the duration of surgery, it showed a trend of shortening first and then prolonging with the increase of the number of cases, which may be related to the extent of the procedure. We assume that the duration of surgery shortened with the improvement of surgeon's skills while repeating the procedure, and later, the surgeon dissected LNs on a larger scale and became more careful to prevent extra damage, which eventually caused the prolongation of the surgery time. This study shows that with the number of laparoscopic radical gastrectomy cases increased, the duration of surgery is shortened and the amount of intra-operative blood loss will decrease, which may due to the improvement of surgeon's proficiency as well as the improvement of teamwork. Laparoscopic radical gastrectomy is safe and feasible, which can achieve the same results with laparotomy in the aspect of LN dissection.

CONCLUSION

Laparoscopic radical gastrectomy is superior to open surgery in the aspects of intra-operative blood loss, post-operative exhaust time, post-operative hospital stay and timing of drain removal. With the number of laparoscopic radical gastrectomy cases increased, the duration of surgery is shortened and the amount of intra-operative blood loss will decrease.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Torre LA, Bray F, Siegel RL, Ferlay J, Lortet-Tieulent J, Jemal A, et al. Global cancer statistics, 2012. CA Cancer J Clin. 2015;65:87–108. doi: 10.3322/caac.21262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hwang JE, Ki MS, Kim K, Jung SH, Shim HJ, Bae WK, et al. The optimal chemotherapeutic regimen in D2-resected locally advanced gastric cancer: A propensity score-matched analysis. Oncotarget. 2017;8:66559–68. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.16301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Goh PM, Alponat A, Mak K, Kum CK. Early international results of laparoscopic gastrectomies. Surg Endosc. 1997;11:650–2. doi: 10.1007/s004649900413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bhandarkar DS, Katara AN, Mittal G, Shah R, Udwadia TE. Prevention and management of complications of laparoscopic splenectomy. Indian J Surg. 2011;73:324–30. doi: 10.1007/s12262-011-0331-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kinoshita T, Kaito A. Current status and future perspectives of laparoscopic radical surgery for advanced gastric cancer. Transl Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;2:43. doi: 10.21037/tgh.2017.04.05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhang F, Lan Y, Tang B, Hao Y, Shi Y, Yu P, et al. Comparative study of laparoscopy-assisted and open radical gastrectomy for stage T4a gastric cancer. Int J Surg. 2017;41:23–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2017.01.116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Akiyama S, Kodera Y, Koike M, Kasai Y, Hibi K, Ito K, et al. Small incisional esophagectomy with endoscopic assistance: Evaluation of a new technique. Surg Today. 2001;31:378–82. doi: 10.1007/s005950170166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sano T. Evaluation of the gastric cancer treatment guidelines of the Japanese gastric cancer association. Gan To Kagaku Ryoho. 2010;37:582–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Can MF, Yagci G, Cetiner S. Systematic review of studies investigating sentinel node navigation surgery and lymphatic mapping for gastric cancer. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2013;23:651–62. doi: 10.1089/lap.2012.0311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhang H, Sang J, Liu F. Recognition of specialization of minimally invasive treatment for gastric cancer in the era of precision medicine. Zhonghua Wei Chang Wai Ke Za Zhi. 2017;20:847–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Japanese Gastric Cancer Association. Japanese gastric cancer treatment guidelines 2014 (ver 4) Gastric Cancer. 2017;20:1–9. doi: 10.1007/s10120-016-0622-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jeong IH, Kim JH, Lee SR, Kim JH, Hwang JC, Shin SJ, et al. Minimally invasive treatment of gastric gastrointestinal stromal tumors: Laparoscopic and endoscopic approach. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2012;22:244–50. doi: 10.1097/SLE.0b013e31825078f2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ajani JA, D'Amico TA, Almhanna K, Bentrem DJ, Chao J, Das P, et al. Gastric cancer, version 3.2016, NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2016;14:1286–312. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2016.0137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kim H, Kim JH, Lee YC, Kim H, Youn YH, Park H, et al. Growth patterns of signet ring cell carcinoma of the stomach for endoscopic resection. Gut Liver. 2015;9:720–6. doi: 10.5009/gnl14203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen W, Zheng R, Zhang S, Zhao P, Zeng H, Zou X, et al. Annual report on status of cancer in China, 2010. Chin J Cancer Res. 2014;26:48–58. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.1000-9604.2014.01.08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kitagawa Y, Fujii H, Mukai M, Kubo A, Kitajima M. Current status and future prospects of sentinel node navigational surgery for gastrointestinal cancers. Ann Surg Oncol. 2004;11:242S–4S. doi: 10.1007/BF02523637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Deng Y, Zhang Y, Guo TK. Laparoscopy-assisted versus open distal gastrectomy for early gastric cancer: A meta-analysis based on seven randomized controlled trials. Surg Oncol. 2015;24:71–7. doi: 10.1016/j.suronc.2015.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li HZ, Chen JX, Zheng Y, Zhu XN. Laparoscopic-assisted versus open radical gastrectomy for resectable gastric cancer: Systematic review, meta-analysis, and trial sequential analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Surg Oncol. 2016;113:756–67. doi: 10.1002/jso.24243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Etoh T, Shiraishi N, Inomata M. Notes on laparoscopic gastrointestinal surgery-current status from clinical studies of minimally invasive surgery for gastric cancer. J Vis Surg. 2017;3:14. doi: 10.21037/jovs.2017.01.12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Xie D, Yu C, Liu L, Osaiweran H, Gao C, Hu J, et al. Short-term outcomes of laparoscopic D2 lymphadenectomy with complete mesogastrium excision for advanced gastric cancer. Surg Endosc. 2016;30:5138–9. doi: 10.1007/s00464-016-4847-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hao Y, Yu P, Qian F, Zhao Y, Shi Y, Tang B, et al. Comparison of laparoscopy-assisted and open radical gastrectomy for advanced gastric cancer: A retrospective study in a single minimally invasive surgery center. Medicine (Baltimore) 2016;95:e3936. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000003936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Marchesi F, De Sario G, Cecchini S, Tartamella F, Riccò M, Romboli A, et al. Laparoscopic subtotal gastrectomy for the treatment of advanced gastric cancer: A comparison with open procedure at the beginning of the learning curve. Acta Biomed. 2017;88:302–9. doi: 10.23750/abm.v%vi%i.6541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhao LY, Zhang WH, Sun Y, Chen XZ, Yang K, Liu K, et al. Learning curve for gastric cancer patients with laparoscopy-assisted distal gastrectomy: 6-year experience from a single institution in Western China. Medicine (Baltimore) 2016;95:e4875. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000004875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kang SY, Lee SY, Kim CY, Yang DH. Comparison of learning curves and clinical outcomes between laparoscopy-assisted distal gastrectomy and open distal gastrectomy. J Gastric Cancer. 2010;10:247–53. doi: 10.5230/jgc.2010.10.4.247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Choi YY, Song JH, An JY. Reply: Factors favorable to reducing the learning curve of laparoscopic gastrectomy for gastric cancer. J Gastric Cancer. 2016;16:128–9. doi: 10.5230/jgc.2016.16.2.128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yao H, Huang Q, Zhu Z, Liang W. Laparoscopy-assisted D2 radical distal gastrectomy for gastric cancer (Billroth II anastomosis) Chin J Cancer Res. 2013;25:451–2. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.1000-9604.2013.07.02. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Moon JS, Park MS, Kim JH, Jang YJ, Park SS, Mok YJ, et al. Lessons learned from a comparative analysis of surgical outcomes of and learning curves for laparoscopy-assisted distal gastrectomy. J Gastric Cancer. 2015;15:29–38. doi: 10.5230/jgc.2015.15.1.29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hu WG, Ma JJ, Zang L, Xue P, Xu H, Wang ML, et al. Learning curve and long-term outcomes of laparoscopy-assisted distal gastrectomy for gastric cancer. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2014;24:487–92. doi: 10.1089/lap.2013.0570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kim CY, Nam BH, Cho GS, Hyung WJ, Kim MC, Lee HJ, et al. Learning curve for gastric cancer surgery based on actual survival. Gastric Cancer. 2016;19:631–8. doi: 10.1007/s10120-015-0477-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jin SH, Kim DY, Kim H, Jeong IH, Kim MW, Cho YK, et al. Multidimensional learning curve in laparoscopy-assisted gastrectomy for early gastric cancer. Surg Endosc. 2007;21:28–33. doi: 10.1007/s00464-005-0634-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]