Abstract

We report the case of a 56-year-old man presenting several episodes of body image distortions with a sensation of having a horn growing on his forehead, as a unicorn, corresponding to the Alice in Wonderland syndrome. Brain single-photon emission computed tomography with technetium-99m hexamethylpropyleneamine oxime showed hypoperfusion of the visual primary cortex, expanding to the temporo-occipital junction bilaterally but predominantly on the right side.

Keywords: Alice in Wonderland syndrome, brain single-photon emission computed tomography, technetium-99m hexamethylpropyleneamine oxime

INTRODUCTION

Alice in Wonderland syndrome (AIWS) is described as self-experienced paroxysmal body image illusions involving distortions of the size, mass, or shape of the patient's own body or its position in space, often occurring with depersonalization and derealization. Lippman[1] first described this syndrome in 1952 in seven patients experiencing migraines accompanied by body image distortions. Only 3 years later did Todd[2] name this syndrome after Lewis Carroll's famous book “Alice's Adventures in Wonderland,” including in the definition several manifestations experienced by Alice in the book such as visual illusions which introduced confusion into the nosology. The mechanisms underlying this rare syndrome are little known. We present the case of a patient presenting this syndrome who underwent brain single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) with technetium-99m (Tc-99m) hexamethylpropyleneamine oxime (HMPAO) and discuss the results.

CASE REPORT

We present the case of a 56-year-old man with a history of migraine without and with (visual) aura presenting several episodes of body image distortions corresponding to the AIWS.

He experienced several episodes of unusual auras preceding typical migrainous headache. The aura lasted 5 min. The course of the crisis was stereotyped, with occurrence mostly at night before getting asleep of episodes of body image distortion with the sensation of having a horn growing on his forehead, as a unicorn, being aware of its unreal nature, but with a feeling of panic, followed by the onset of intense migraine headache. These episodes occurred regularly during periods of symptomatic phases altering with periods of calm. The patient reported, moreover, no visual or phasic disturbance, or paresthesia. Neurological examination was normal.

Brain magnetic resonance imaging and electroencephalogram were normal.

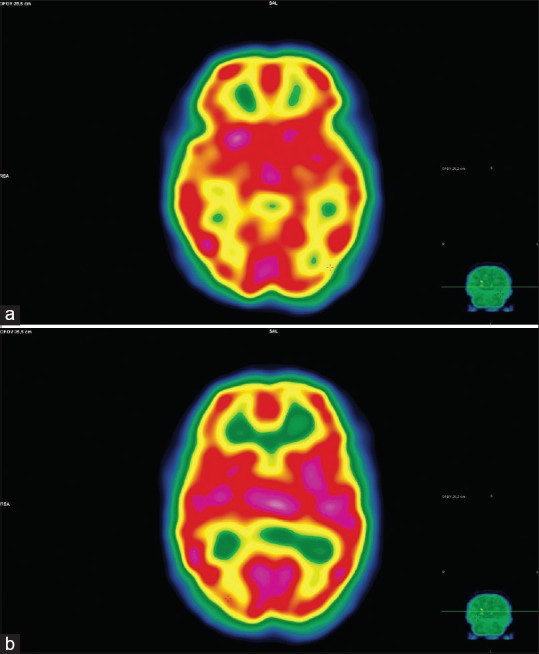

HMPAO SPECT showed moderate hypoperfusion of the primary visual cortex expanding to the temporo-occipital junction bilaterally but predominantly on the right side [Figure 1a and b].

Figure 1.

(a and b) Hexamethylpropyleneamine oxime single-photon emission computed tomography shows moderate hypoperfusion of the primary visual cortex, expanding to the temporo-occipital junction bilaterally but predominantly on the right side

DISCUSSION

In 2002, the AIWS was precisely redefined, describing one obligatory symptom (somesthetic perceptual disturbances) and multiple accessory symptoms including visual illusions, depersonalization, and derealization.[3]

The mechanisms underlying this rare syndrome have been explored using various perfusion and functional imaging techniques. Recently, Morland et al. reported brain SPECT findings in a case with localized perfusion defect affecting the frontoparietal opercula of the nondominant hemisphere.[4]

Some brain perfusion studies[5,6] using single-photon emission tomography have been conducted in children at the acute phase of an “AIWS,” but children felt visual illusions (metamorphopsia) rather somatosensory ones: Gencoglu et al.[5] reported brain Tc-99m HMPAO SPECT results in a case that presented episodes of micropsia and macropsia but without somesthetic perceptual disturbances, showing hypoperfusion in the right frontal and frontoparietal regions. In Kuo's study,[6] Tc-99m HMPAO SPECT brain scans were performed in patients presenting metamorphopsia during the acute stage of AIWS. The decreased cerebral perfusion areas in all patients were localized in “the temporal lobe, occipital lobe, and the adjacent area of the perisylvian fissure, all of which are close to the visual pathway and the associated visual cortex.”

Hung et al.[7] in a SPECT study reported hypoperfusion of the occipital cortex.

In Brumm's ferromagnetic resonance study,[8] a child presenting micropsia showed reduced activation in primary and extrastriate visual cortical regions but increased activation in parietal lobe cortical regions as compared with a matched control participant.

Together with some rare previous neuroimaging reports, our results suggest that AIWS could be linked to functional impairment of the occipital cortex (hypoperfusion of primary visual cortex). There was no involvement of the frontoparietal regions in our case. Although many questions remain, our results implicate dysfunctional neurophysiological processing in occipital regions in AIWS.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent forms. In the form the patient(s) has/have given his/her/their consent for his/her/their images and other clinical information to be reported in the journal. The patients understand that their names and initials will not be published and due efforts will be made to conceal their identity, but anonymity cannot be guaranteed.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Lippman CW. Certain hallucinations peculiar to migraine. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1952;116:346–51. doi: 10.1097/00005053-195210000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Todd J. The syndrome of Alice in wonderland. Can Med Assoc J. 1955;73:701–4. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Podoll K, Ebel H, Robinson D, Nicola U. Obligatory and facultative symptoms of the Alice in wonderland syndrome. Minerva Med. 2002;93:287–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Morland D, Wolff V, Dietemann JL, Marescaux C, Namer IJ. Robin wood caught in wonderland: Brain SPECT findings. Clin Nucl Med. 2013;38:979–81. doi: 10.1097/RLU.0000000000000230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gencoglu EA, Alehan F, Erol I, Koyuncu A, Aras M. Brain SPECT findings in a patient with Alice in wonderland syndrome. Clin Nucl Med. 2005;30:758–9. doi: 10.1097/01.rlu.0000182278.13389.a3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kuo YT, Chiu NC, Shen EY, Ho CS, Wu MC. Cerebral perfusion in children with Alice in Wonderland syndrome. Pediatr Neurol. 1998;19:105–8. doi: 10.1016/s0887-8994(98)00037-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hung KL, Liao HT, Tsai ML. Epstein-barr virus encephalitis in children. Acta Paediatr Taiwan. 2000;41:140–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brumm K, Walenski M, Haist F, Robbins SL, Granet DB, Love T, et al. Functional magnetic resonance imaging of a child with Alice in wonderland syndrome during an episode of micropsia. J AAPOS. 2010;14:317–22. doi: 10.1016/j.jaapos.2010.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]