Abstract

Objective:

To evaluate factors associated naturalistically with adherence to a mobile headache diary.

Background:

Self-monitoring (keeping a headache diary) is commonly used in headache to enhance diagnostic accuracy and evaluate the effectiveness of headache therapies. Mobile applications are increasingly used to facilitate keeping a headache diary. Little is known about factors associated with adherence to mobile headache diaries.

Methods:

In this naturalistic longitudinal cohort study, people with headache (n = 1,561) registered to use Curelator Headache ® (now called N1-Headache ®), an application that includes a mobile headache diary, through their physician (coupon), or directly through the website or app store using either a paid or free version of the application. Participants completed baseline questionnaires and were asked to complete daily recordings of headache symptoms and other factors for at least 90 days. Baseline questionnaires included headache characteristics and migraine disability. Daily recordings included headache symptoms and anxiety ratings. Adherence to keeping the headache dairy was conceptualized as completion (kept the headache diary for 90 days), adherence rate (proportion of diary days completed 90 days after registration), and completion delay (the number of days past 90 days after registration required to complete 90 days of headache diary).

Results:

The majority of participants reported migraine as the most common headache type (90.0%), and reported an average of 30.8 headache days/90 days (SD = 24.2). One-third of participants completed 90 days of headache diary (32.4%). Endorsing higher daily anxiety scores [8/10 OR = 0.97 (95% CI = 0.96, 0.99); 10/10 OR = 0.96 (95% CI = 0.91, 0.99)] was associated with lower odds of completion, whereas higher age [OR = 1.04 (95% CI = 1.03, 1.05)], and downloading the app paid vs. free [OR = 4.27 (95% CI = 2.62, 7.06)], paid vs. coupon [OR = 2.43, 95% CI = 1.41, 4.26)], or through a physician coupon vs. free [OR = 1.75 (95% CI = 1.27, 2.42) were associated with higher odds of completion. The median adherence rate at 90 days was 0.34 (IQR = 0.10-0.88), indicating that half of participants kept 34 or fewer days 90 diary days after registration. Endorsing high daily anxiety scores [5/10 OR = 0.98 (95% CI = 0.97, 1.00); 8/10 OR = 0.96 (95% CI = 0.94, 0.98); 10/10 OR = 0.96 (9% CI = 0.92, 0.98)] and higher age [OR = 1.05 (95% CI = 1.04, 1.07)] were associated with lower odds of adhering at 90 days, whereas downloading the app paid vs. free [OR = 9.63 (95% CI = 4.61, 25.51)], paid vs. coupon [OR = 2.39, 95% CI = 1.27, 5.10)], or through a physician coupon vs. free [OR = 4.01 (95% CI = 2.54, 7.26) were associated with higher odds of adhering at 90 days. Among completers, the median completion delay was 6.0 days (IQR = 2.0-15.0). Among completers, endorsing high daily anxiety scores [9/10 OR = 1/06 (95% CI = 1.01, 1.12)] and younger age [OR = 0.98 (95% CI = 0.97, 1.00)] was associated with completion delay; downloading the app through physician coupon vs. free [OR = 0.40 (95% CI = 0.22, 0.71)] or paid vs. free [OR = 0.38 (95% CI = 0.20, 0.72)] was associated with lower odds of completing 90 diary days in 90 calendar days.

Conclusion:

This naturalistic observational study confirmed evidence from clinical observation and research: adherence to mobile headache diaries is a challenge for a significant proportion of people with headache. Endorsing higher levels of daily anxiety, younger age, and downloading the app for free (vs. either paying for the self-monitoring app or receiving a physician referral coupon) were associated with poorer adherence to keeping a mobile headache diary.

Keywords: Adherence, Headache, Self-Monitoring, Anxiety, mHealth, eHealth

Introduction

Self-monitoring is commonly used to monitor health behaviors and disease activity. A Pew Research study of adults living in the United States found that 69% reported tracking a health indicator, and that those with chronic diseases were more likely to track (1). When used consistently in people with chronic diseases, self-monitoring has been associated with reductions in disease severity and disease-related disability (2–6). Unfortunately, adherence to self-monitoring is generally inadequate across disease states. Further, willingness to self-monitor differs between chronic diseases, and adherence is markedly low in headache patients compared to other patient populations (7).

Self-monitoring, or keeping a “headache diary,” is common in headache disorder research and practice (8). Clinical trials designed to evaluate the efficacy of preventive migraine therapies rely on headache diary metrics to assess primary and secondary outcomes. Failure to adhere to a headache dairy in the context of clinical trials interferes with obtaining accurate estimates of efficacy and could hamper scientific understanding of the efficacy of preventive agents. For example, a recent trial of amitriptyline in adolescents with migraine found that adherence to amitriptyline was 90% when only considering completed headache diary days, but 79% when considering missing diary days as skipped doses (9). This example highlights the significant problem missing diary days can present in analyzing and interpreting clinical trials for preventive migraine agents.

In clinical practice, many neurologists recommend patients keep a headache dairy to enhance diagnostic accuracy and evaluate the effectiveness of headache therapies. Some patients with headache disorders may continue to self-monitor headache activity, other symptoms, exposures, or behaviors in order to identify personally factors related to headache onset, warning signs, or to track adherence to headache management strategies. In these naturalistic clinical settings, missing diary days can interfere with clinician and patient interpretation of the results of headache self-monitoring, potentially leading to inaccurate diagnosis, misunderstanding of the clinical efficacy of a new treatment regimen, and erroneous patient beliefs regarding factors related to their headaches.

Despite the importance of adherence to keeping a headache dairy for both research and clinical applications, very few studies have explicitly evaluated adherence to headache diaries. Available data suggest adherence to headache diaries is mixed. Overall estimates of adherence to paper diaries range from 83-95%, and around 90% for outpatient electronic monitoring; the majority of studies had relatively small sample sizes and included either patients from a single practice or from a randomized clinical trial (10). Recent advances in technology and the subsequent cultural ubiquity of smartphones have changed the ease with which self-monitoring can be integrated into a patient’s life, and provided new avenues to evaluate and promote adherence to self-monitoring. In the extant adherence to headache diary literature, adherence to electronic diaries tends to be somewhat higher than adherence paper diaries (10). Further, electronic diaries provides a more reliable estimate of headache activity compared to paper diaries because of a closer proximity between the act of recording and the timeframe being assessed (11). It should be noted that the majority of research evaluating adherence to headache diaries has occurred in the context of randomized clinical trials. Naturalistic studies analyzing adherence to headache diaries in pain conditions yield significantly lower rates. For example, a recent study evaluating a 5-question daily pain self-monitoring app in 90 chronic pain patients found that, on average, participants completed 38.8% of daily assessments, and approximately one-quarter of participants (26.7%) recorded 90 daily assessments in a 3 month period (12). Little is known about adherence to mobile headache diaries in a naturalistic context, using the patient’s own electronic device, rather than in the context of a larger study where the devices were provided and adherence closely monitored by study staff. This is particularly important as headache diaries increasingly move to personal electronic devices in both research and clinical contexts. Understanding rates of adherence to headache diary in a naturalistic context allows us to understand the reliability of electronic headache diaries; understanding predictors of adherence to headache diary self-monitoring is the first step to improving the quality of evidence used across the field in both research and clinical contexts.

Evidence suggests that certain subgroups may be at higher risk for non-adherence to headache diaries; identification of subgroups at risk for non-adherence can provide guidance for tailoring interventions to improve adherence in research, clinical practice, or in the headache diary applications themselves. A clinical study evaluating completion of paper headache diaries mailed to patients prior to their first visit in a headache center found that 93% returned diaries that were sufficiently completed to facilitate an accurate diagnosis (13). Interim analysis of an ongoing randomized clinical trial evaluating a behavioral migraine treatment found similar average adherence to electronic headache diaries as identified in previous trials (13% for two months of monitoring, 20% for four months of monitoring), but also found that a small number of participants (7 out of 38) accounted for a disproportionate amount of missing days (14). In the chronic pain literature, higher complexity of pain problems and taking more medication were associated with higher rates of adherence to a self-monitoring app (15); however, little is known about characteristics of people with headache that may be associated with adherence to electronic headache diaries. Understanding factors associated with adherence to electronic headache diaries can help identify subgroups of patients less likely to adhere, and aid in intervention development to improve adherence, to electronic headache diaries.

Anxiety is a psychiatric symptom characterized by worry and heightened arousal common in headache disorders (16–18). Evidence regarding the role of anxiety in adherence to medication and appointment-keeping is mixed. The majority of studies suggesting anxiety is associated with poorer adherence, while a few have found that anxiety is a protective factor for adherence (19–22). This is consistent with a well-established phenomenon known as the Yerkes-Dodson Law, which predicts that performance will increase with physiological or mental arousal until a certain optimal point after which additional arousal results in decreased performance (23). When applied to the context of adherence to a headache diary, the Yerkes-Dodson Law would suggest that both very low and very high levels of anxiety may be associated with poorer adherence to headache self-monitoring, the first because the patient is not concerned enough about headache to self-monitor, and the second because the patient is so overwhelmed with worry about headache that they may not want to engage in self-monitoring. Thus, existing theory and empirical literature in other diseases support evaluating different levels of anxiety and their relationships with adherence to headache self-monitoring.

The current study aims to describe user adherence to a smartphone-based headache diary, and to evaluate the relationships between level of anxiety and adherence to the electronic headache diary between individuals. The mobile health platform used in this study, Curelator Headache®, involves users tracking headache symptomatology and exposure to more than 70 emotional, dietary and environmental factors, including anxiety level (0-10), for at least 90 days. There are three types of accounts: coupon, paid and free (Figure 1). The set of users with paid and coupon account types are incentivized to enter data for 90 days because only after 90-days of data entry do they receive a series of maps (24) showing their individualized factors associated with 1) increased risk of headache attack occurrence, 2) decreased risk of headache attack occurrence, and 3) factors not associated with headache attack occurrence.

Figure 1.

User flow of Curelator Headache®. Users download the app with 3 different types of accounts (free, coupon, and paid). Users then register and complete the 1-time onboarding questionnaire. Users then enter daily data headache symptoms and potential trigger factors. After 90 days, paid and coupon users get personalized maps of risk factors.

We aimed to describe adherence to the electronic headache diary in several ways:

Proportion of consented participants who completed 90 diary days (completion).

Number of complete days of data at the 90th diary day (adherence rate).

Extra days needed to reach 90 complete days of diary data (completion delay).

We aimed to evaluate anxiety level between individuals in relation to the adherence outcomes described above.

Methods

Study Design

This is a naturalistic longitudinal cohort study using data from a commercial electronic headache diary (Curelator Headache® now called N1-Headache®) to evaluate adherence to electronic headache diary over 90 days in people with headache.

Participants

Potential participants registered to use Curelator Headache® a) directly through a physician ‘coupon referral’ program, b) via the Curelator website or c) the App Store (iOS users only) (Figure 1). Inclusion criteria were a) registered for the Curelator Headache® diary from October 2014 to October 2016, as a two-year time frame allowed for the app to be on the market long enough to collect users who registered for the paid version of the app as well as the free and coupon referral versions; b) completion of at least 4 diary days, as we were interested in adherence to the electronic headache diary among people who had made at least a minimal commitment to keeping the diary; c) if an active user (e.g., has used the app within the past 30 days), the participant must have reached the 90th diary day, which is necessary to allow for classification of the primary outcome variable (being classified as a “completer” or “non-completed,” as described below) d) reported age and gender, as these descriptive statistics are foundational to the analyses; e) reported a date of birth corresponding with an age of 18 or older, as factors associated with adherence to keeping an electronic headache diary in children likely differs from factors associated with adherence in adults. The app is only available in English, thus its users are mainly native English speakers. At download and registration, users explicitly gave consent for use of anonymized collected data for research purposes.

Procedures

Patients learn about Curelator through 1) direct internet channels (e.g., app store, search, social media), 2) patient associations or support groups, or 3) medical providers. One hundred ten providers participated in the coupon referral program described above, and these providers had 550 patients enrolled in the app. Approximately 59% of patients who were given a coupon at these practices registered for the app.

After the registration process in the app, participants completed the onboarding process by completing baseline questionnaires used to customize the daily diary (such as identifying whether participants smoked, consumed alcohol, or experienced menstrual bleeding) and to establish a clinical baseline for their headaches (type of headache, diagnosis, frequency, severity and MIDAS disability) and medication (both headache-related and other). Participants then completed the electronic headache diary daily for up to 90 days. Daily diary questions included headache symptoms (18 questions) and exposure to 81 putative migraine risk factors (Figure 1; Supplemental Table). Putative risk factors included emotions, sleep qualities, environmental and weather, lifestyle, diet, substance use, travel, and up to three personalized triggers selected by each participant. Participants had the option to set an alert to remind them to fill out the headache diary each day. Each diary entry took participants approximately 2-3 minutes to complete. For participants who completed 90 days of diary (consecutively, or non-consecutively), factors associated with N=1 attack onset were determined, and participants received maps visualizing these relationships (24).

Measures

Participant Characteristics

At registration, participants select either “Female”, “Male” or “Other” to signify gender. Participants report date of birth at registration; age for each participant on October 1st, 2016 is then estimated from the reported date of birth. Account type (free, paid, or coupon) was indicated automatically during account registration.

In the baseline questionnaire, participants indicated the type(s) of headache from which they believe they suffer: migraine, tension-type headache, cluster headache and/or other. If migraine was selected above, participants were asked whether they had a physician diagnosis of migraine. Participants completed the Migraine Disability Assessment (MIDAS), a five-item questionnaire designed to assess migraine-related disability (25). The MIDAS has demonstrated good internal consistency (α = 0.76) and criterion validity with daily diary-assessed disability (r = 0.63) (25).

Adherence to Self-Monitoring

Table 1 summarizes the adherence to electronic headache dairy outcomes considered in this paper. Participants entering any amount of diary data on 90 separate days were defined as “completers”; participants who did not enter diary data on 90 separate days were “non-completers”. Adherence rate was defined as the proportion diary days fully completed 90 days after registration. For completers, completion delay was defined as the number of days extra days needed to reach 90 diary days entered (i.e., number of days in the study – 90, when 90 diary days was reached).

Table 1.

Description of Adherence Outcome Variables and Analysis Strategy

| Name | Definition | Variable type | Cohort | Model |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Completion | Completed 90 diary days | Binary (completers/non-completers) | Total Sample | Logistic |

| Adherence Rate | (Number of complete days of data at 90 days)/90 | Numerical continuous [0,1] | Total Sample | Ordinal logistic regression |

| Completion Delay | Extra days needed to reach 90 complete days of data | Numerical discrete [0-640) | Completers | Hurdle Negative Binomial |

Anxiety

Anxiety was assessed daily using the following item: “How nervous/anxious/worried have you felt today?”. Response options were coded on an 11-point Likert scale ranging from 0 (not at all) to 10 (a lot). For each participant, the percentage of days (up to 90 complete days of data entry) on which a participant endorsed each anxiety score was computed, resulting in eleven anxiety variables (Anxiety 0, Anxiety 1, Anxiety 2, etc). For example, the variable “Anxiety 3” indicates the percentage of days on which the participant endorsed a score of “3” on the 0-10 anxiety scale. This method of analyzing the day-level anxiety variable allowed us to analyze multiple diary day ratings of anxiety with a minimal loss of range in the assessment of anxiety. Sensitivity analyses for the primary outcome (completion) aggregated this variable in two ways 1) proportion of mild (1-3) moderate (4-6) and severe (7-10) anxiety ratings; and 2) mean anxiety rating.

Statistical methods

The Einstein IRB approved the analyses reported in this manuscript (2017-8530). All study variables were described. Three different analyses assessed the relationship between anxiety and each of the three adherence outcomes. Complete data was required for each analysis, therefore cases missing data were removed from each analysis. Collinearity was assessed using the Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) and by inspecting the Spearman correlation among the anxiety variables; models were probed to identify variables responsible for any collinearity, which were removed.

Completion was evaluated using a logistic regression with age, gender, account type and anxiety variables as covariates in the full model. The sample was randomly divided into a training sample (1,357 participants) and a testing sample (312 participants) to test the robustness of the model created using the training sample (26). In the training sample, the full model was estimated and improved stepwise aiming to minimize the AIC (Akaike’s Information Criterion). A deviance table and Wald’s tests evaluated the quality and significance of the model. The McFadden pseudo R2 evaluated goodness of fit. Likelihood ratio tests evaluated the role of anxiety in the model. In the testing sample, the predictive ability of the model was evaluated using an Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curve. In order to further evaluate the robustness of our findings, we also conducted sensitivity analyses evaluating anxiety as proportion of mild (1-3) moderate (4-6) and severe (7-10) anxiety ratings, and as a single number describing the average of all anxiety scores within each participant.

Adherence rate was evaluated using an ordered logit model. Descriptive analysis of adherence rate indicated grouping the response variable into three intervals [0,0.25), [0.25,0.75) and [0.75,1.00], resulting into an ordered categorical variable. As above, the full model was estimated and improved stepwise aiming to minimize the AIC. Likelihood ratio tests were used to evaluate the significance of each variable in the model. The presence of scale (or dispersion) effects were evaluated; scale effects account for the variability of adherence rate considered as a continuous variable. Significant scale effects were included in the final model.

Completion delay exhibited over-dispersion as well a high number of zero observations; ultimately, the Hurdle Negative Binomial (HNB) model was selected. The HNB has two components; one component models zeros vs. larger counts (binomial) and the other models positive counts (negative binomial). As above, the full model was estimated and improved stepwise aiming to minimize the AIC. A likelihood ratio test evaluated whether the hurdle component was needed, and whether anxiety variables were significant.

All analyses were performed using R version 3.4.1 (2017-06-30) (27). All tests were two-tailed with α set at .05.

Results

Four thousand two hundred and seven participants registered to use Curelator Headache ® between October 2014 and October 2016 (Figure 2). Users who were still actively monitoring headache diary days during the first 90 days period (n = 478) were not able to be classified as adherent or non-adherent on any outcome in this study, and were therefore excluded. Participants who downloaded the app and registered, but completed three or fewer complete days of data, were removed from the study sample (1,861). Participants who were removed show low variability in anxiety scores: 70% recorded the same anxiety score each day. There were significantly more men in the group with three or fewer complete days in the removed sample (14.9%) compared to the retained sample (12.1%), p =.013. People in the group with three or fewer complete days were also slightly younger (M age = 28.2) than the retained sample (M age = 33.7), p < .001. Proportion of people removed from the analysis differed by account type (p < .001); the paid group had the highest proportion of people retained for analysis (93.9% vs. 6.1%), followed by the coupon group (81.5% vs. 18.5%); fewer than half people in the free group were retained for analysis (41.3% vs. 58.7%), all ps < .001.

Figure 2.

Participant flow diagram.

Selected statistical models need complete data, thus participants without age information were removed from the dataset. Age was not reported in 172 of the 1,868 participants with >3 tracked days. Gender was not related to reporting age, p =.09. Proportion of people who reported age information differed by account type (p < .001). Age was reported by the vast majority of people in both the coupon (99.1%) and paid groups (96.9%), which did not differ from each other, p = .340. Age was reported by a smaller proportion of people in the free group (88.4%) compared to both the coupon (p < .001) and paid groups (p = .004). Finally, data for the 135 participants younger than 18 years of age were removed.

Therefore, of the 4,207 participants, 40.3% met criteria for these analyses, resulting in a final sample of 1,561 (Figure 2). The majority of participants were female (88.1%) and recruited through free account (74.2%), with 17.9% from coupon referral and 7.9% from paid account. Participant age ranged from 18 to 80 years old (M = 39.0, SD = 13.2). More than half of participants reported full-time employment (59.3%), and 10.1% were students. On average, participants completed 43.9 (SD = 35.6) of 90 diary days (Table 2). About half of these participants were from the United States and England, and the rest from Canada, Australia and other countries.

Table 2.

Participant Characteristics at Baseline

| N (%) or M (SD) N = 1,561 |

|

|---|---|

| Age | 39.0 (13.2) |

| Gender | |

| Female | 1,376 (88.1%) |

| Male | 182 (11.7%) |

| Other | 3 (0.2%) |

| Account Type | |

| Coupon | 279 (17.9%) |

| Paid | 123 (7.9%) |

| Free | 1,159 (74.2%) |

| Physician Diagnosis of Migraine | |

| Yes | 1,246 (79.8%) |

| No | 315 (20.2%) |

| Headache Days (past 3 months) | 30.8 (24.2) |

| Completed Diary Days (out of 90) | 43.9 (35.6) |

Ninety percent of participants reported migraine as their most common headache type, and the majority (79.8%) reported a physician diagnosis of migraine. At baseline, participants retrospectively reported an average of 30.8 (SD=24.2) headache days in the past three months, and an average headache pain severity of 6.4 (SD=1.8) out of 10. The majority of participants (67.5%) reported severe migraine-related disability (MIDAS Score ≥ 21). The average number of doctor visits reported in the last three months (excluding emergency room) was 1.7 (SD=3.6).

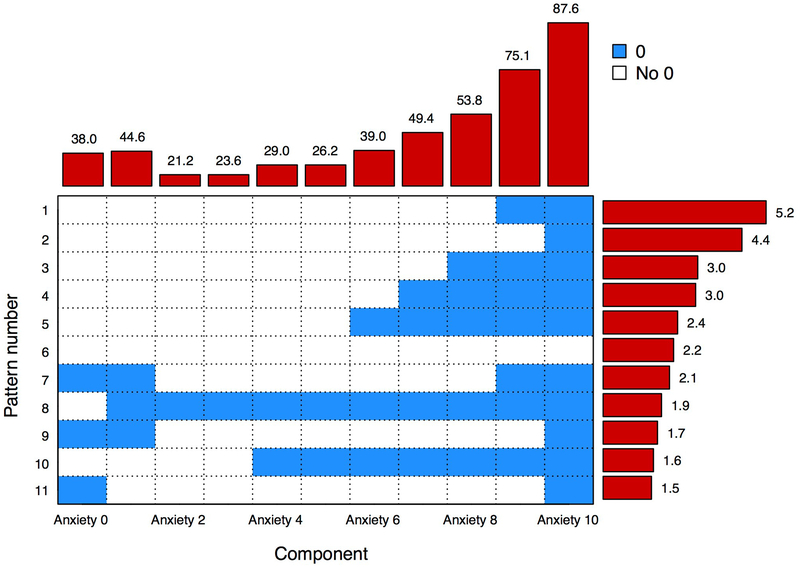

Regarding daily ratings of anxiety, the most commonly used scores were at the lower end of the 0-10 scale (78.8% of participants reported a 2, and 76.4% reported a 3, at least once), whereas the least commonly used scores were at the upper end of the scale [87.6% of participant never reported a 10; 75.1% never reported a 9; and approximately half never reported an 8 (53.8%) or a 7 (49.4%)]. Figure 3 describes the 11 most common patterns of observed and unobserved anxiety scores; this figure represents 29.0% of the participants and includes marginal barplots displaying percentage of unobserved values by component (top) and percentage of occurrence of the pattern (right).

Figure 3.

Summary of the 11 most frequent patterns of anxiety scores. This figure represents 29.0% of users. Barplots on the margins display percentage of unobserved values by component (top) and percentage occurrence of the patterns in the data set (right).

Completion

Of the 1,561 participants, 505 completed 90 days of self-monitoring (32.4%).

The final logistic regression model for completion included age, account type and the percentage of anxiety scores 3, 5, 8 and 10 (Table 3). The McFadden R2 statistic of the model is low (0.10), indicating the model was only slightly better than the null model; however, the likelihood ratio tests comparing the model with and without the anxiety variables indicate that the model with anxiety has a better fit, p < .001.

Table 3:

Logistic Regression Evaluating Completion (n = 1,561)

| Completed | Non-Completed | Odds Ratio | 95% CI | p-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M (SD) or N (%) | M (SD) or N(%) | Lower | Upper | |||

| Intercept | 0.14 | 0.09 | 0.22 | <.001 | ||

| Anxiety 3 | 12.6 (14) | 11.9 (9.2) | 0.99 | 0.98 | 1.00 | 0.079 |

| Anxiety 5 | 12.1 (13.7) | 9.6 (9.5) | 0.99 | 0.97 | 1.00 | 0.010 |

| Anxiety 8 | 5.6 (10.5) | 3.3 (5.2) | 0.97 | 0.96 | 0.99 | 0.004 |

| Anxiety 10 | 1.5 (6.8) | 0.4 (2.4) | 0.96 | 0.91 | 0.99 | 0.049 |

| Age | 36.7 (12.8) | 43.9 (12.6) | 1.04 | 1.03 | 1.05 | <.001 |

| Account Type | ||||||

| Coupon | 168 (60.2) | 111 (39.8) | ||||

| Paid | 42 (34.1) | 81 (65.9) | ||||

| Free | 846 (73) | 313 (27) | ||||

| Coupon vs Free | 1.75 | 1.27 | 2.42 | 0.001 | ||

| Paid vs. Free | 4.27 | 2.62 | 7.06 | <0.001 | ||

| Paid vs. Coupon | 2.43 | 1.41 | 4.26 | 0.002 | ||

Note. Anxiety scores indicate the percentage of diary days (up to 90 days) on which the participant endorsed a particular score (e.g., Anxiety 3 = percentage of diary days on which the participant endorsed a score of “3” on a 0-10 scale).

Adjusting for age and account type, a higher percentage of anxiety 8 and 10 were significantly associated with lower odds of completion (p = .004 and.049). Adjusting for other variables in the model, higher age was associated with higher odds of completion (OR = 1.04, p < .001). Adjusting for other variables in the model, coupon (coupon vs. free OR = 1.75, p < .001) and paid account types (paid vs. free OR = 4.27, p < .001) were associated with higher odds of completion than the free account type; the paid account type (paid vs. coupon OR = 2.43, p < .001) was associated with higher odds of completion than the coupon account type.

The proportion of completers was similar in the training (32.4%) and test sets (31.7%). In the test set (n = 312), model sensitivity was 90% and specificity 25.7%. The model had an accuracy of 69.2% (95% CI = 63.8 – 74.3), and an area under the curve of 0.73. The model was not significantly better at predicting completion than simply predicting the most common class (one-sided test, p = .295).

Sensitivity analyses evaluating anxiety as three aggregated variables (mild = 1-3; moderate = 4-6; severe = 7-10) and as a single variable representing the average of all anxiety ratings made by each participant found similar results to those described above. Both models retained age and account type as significantly related to completion. In the model evaluating three aggregated anxiety variables, only the severe variable was significantly associated with completion, such that a greater proportion of “high” anxiety scores was associated with lower odds of completion [OR = 0.30 (95% CI = −.14-0.60), p = .001]. In the model evaluating average anxiety score, higher average anxiety was associated with lower odds of completion [OR = 0.86 (95% CI = 0.81, 0.92), p < .001].

Adherence Rate

The median adherence rate at 90 days was 0.34 (IQR = 0.10, 0.88); in other words, half of participants tracked 34 or fewer days 90 days after tracking. The natural bimodal distribution of adherence rate was modeled via an ordered logit model after cutting adherence rate into three intervals: [0.00,0.25), e.g., no days to one-quarter of days of self-monitoring at 90 days, n = 678; [0.25,0.75), e.g., one-quarter to three-quarters of days of self-monitoring at 90 days, n = 364; and [0.75,1.00], e.g., three-quarters to all days of self-monitoring at 90 days, n = 516.

In the final model, age, account type, gender and percentage of anxiety scores 5, 8 and 10 were associated with adherence rate (Table 5). A significant scale effect of age (p = .003) was also included in the final model. Adjusting for the other variables in the model, higher percentage of anxiety scores of 5, 8 or 10 were all associated with lower adherence rate categories (ps =.010, >.001 and .006). Higher age was associated with higher adherence rate categories (p < .001). Adjusting for other variables in the model, coupon (coupon vs. free OR = 4.03, p < .001) and paid account types (paid vs. free OR = 9.63, p < .001) were associated with higher adherence rate categories than the free account type; additionally, the paid account type (paid vs. coupon OR = 2.39, p = .012) was associated with higher adherence rate categories than coupon. A likelihood ratio test indicated that the model improved with the addition of anxiety variables (p<0.001).

Table 5.

HNB Model Evaluating Completion Delay (n = 496)

| Completion Delay [N(%)] | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | > 0 | Odds Ratio | 95% CI |

p-value | |||||

| [1, 10) | [10, 30) | [30, 89) | >90 | Lower | Upper | ||||

| Count model | |||||||||

| Intercept | 21.21 | 12.01 | 37.47 | <.001 | |||||

| Anxiety 9 | 44.6 (12.7) | 43.7 (12.1) | 41.6 (11.1) | 33.2 (6.4) | 1.06 | 1.01 | 1.12 | 0.012 | |

| Age | 1.0 (2.8) | 1.5 (3.3) | 1.8 (2.6) | 5.6 (8.6) | 0.98 | 0.97 | 1.00 | 0.007 | |

| Zero hurdle Model | |||||||||

| Intercept | 9.17 | 6.29 | 13.36 | <.001 | |||||

| Account Type | |||||||||

| Coupon | 24 (21.6) | 87 (78.4) | |||||||

| Paid | 18 (22.5) | 62 (77.5) | |||||||

| Free | 30 (9.8) | 275 (90.2) | |||||||

| Coupon vs. Free | 0.40 | 0.22 | 0.71 | 0.002 | |||||

| Paid vs. Free | 0.38 | 0.20 | 0.72 | 0.003 | |||||

| Paid vs. Coupon | 0.95 | 0.48 | 1.90 | 0.885 | |||||

Note. Anxiety scores indicate the percentage of diary days (up to 90 days) on which the participant endorsed a particular score (e.g., Anxiety 9 = percentage of diary days on which the participant endorsed a score of “9” on a 0-10 scale.

Completion Delay

The median completion delay was 6.0 days (IQR = 15.0-2.0). Only 14.3% of participants completed the 90 days of self-monitoring in 90 days; an additional 87.7% completed the 90 days of self-monitoring within 120 days. Completion delay ranged from 0 to 533 days; one participant took more than 20 months to complete 90 diary days. The distribution of completion delay is highly right skewed with high levels of dispersion and a high frequency of participants with completion delay=0 days. Eight outliers (participants taking more than 200 days to finish 90 diary days) and one participant who did not report gender were removed from the analysis, resulting in an analysis sample of 496.

In the final model, percentage of anxiety scores of 9 and age were associated with completion delay, and account type was associated with completion delay = 0 (e.g., completing 90 days of tracking in 90 days) (Table 4). Adjusting for other variables in the model, a higher percentage of anxiety 9 scores was associated with higher completion delay (OR =1.06, p = .012), and higher age associated with lower completion delay, (OR = 0.98, p = .007). Adjusting for other variables in the model, coupon (coupon vs. free OR = 0.39, p =.002) and paid account types (paid vs. free OR = 0.38, p = .003) were associated with lower odds of having a completion delay above 0 (e.g., taking longer than 90 days to complete 90 days of self-monitoring), compared to the free account type.

Table 4.

Ordered Logit Model Evaluating Adherence Rate (n = 1,558)

| Adherence Rate | Odds Ratio | 95% CI | p-value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [0.00, 0.25) | [0.25, 0.75) | [0.75,1] | |||||

| M (SD) or N (%) | M (SD) or N (%) | M (SD) or N (%) | Lower | Upper | |||

| Anxiety 5 | 12.4 (15.2) | 11.3 (10.2) | 9.8 (9.7) | 0.98 | 0.97 | 1.00 | 0.010 |

| Anxiety 8 | 6.3 (11.8) | 4.2 (5.9) | 3.3 (6.5) | 0.96 | 0.94 | 0.98 | <.001 |

| Anxiety 10 | 1.7 (7.8) | 1.0 (4.7) | 0.5 (2.4) | 0.96 | 0.92 | 0.98 | 0.006 |

| Age | 35.6 (12.4) | 38.8 (12.5) | 43.7 (13.2) | 1.05 | 1.04 | 1.07 | <.001 |

| Account type | |||||||

| Coupon | 74 (26.5) | 80 (28.7) | 125 (44.8) | ||||

| Paid | 20 (16.3) | 22 (17.9) | 81 (65.9) | ||||

| Free | 584 (50.5) | 262 (22.7) | 310 (26.8) | ||||

| Coupon vs. Free | 4.03 | 2.54 | 7.26 | <.001 | |||

| Paid vs. Free | 9.63 | 4.61 | 25.51 | <.001 | |||

| Paid vs Coupon | 2.39 | 1.27 | 5.10 | 0.012 | |||

| Gender | |||||||

| Male | 77 (42.3) | 45 (24.7) | 60 (33) | ||||

| Female | 601 (43.7) | 319 (23.2) | 456 (33.1) | ||||

| Male vs. Female | 0.67 | 0.40 | 1.03 | 0.080 | |||

| Scale coefficient | |||||||

| Age | 1.01 | 1.00 | 1.02 | 0.006 | |||

Discussion

This naturalistic longitudinal cohort study confirmed evidence from clinical observation and research: adhering to electronic headache diaries is a challenge for a significant proportion of people with headache. Of the potential participants who downloaded the app during the study period, almost half (44.2%) completed fewer than four diary days. Of the participants who were included in the study sample (who completed at least 4 diary days), only one-third completed 90 diary days. At the 90-day mark, half of participants in the study sample tracked approximately one-third of diary days or fewer. However, among participants who eventually completed 90 diary days, the vast majority (87.7%) completed within 120 days, and half required less than one additional week past the 90-day mark to complete 90 diary days. Thus, for a subset of people with headache, adherence to the electronic headache diary was high. The rates of electronic headache dairy adherence observed among all the participants in this study were similar to those described in both clinical research (12) and commercial (15) chronic pain self-monitoring apps. The rates of electronic headache dairy adherence observed among participants who were “completers” were higher, and more consistent with the rest of the headache literature, which predominantly includes data from clinical trials. These results highlight 1) the wide range of adherence to electronic headache diaries across people with headache, and 2) the importance of understanding factors associated with adherence to electronic headache diaries, particularly as these diaries are increasingly used in naturalistic and clinical settings where the patient population is more diverse than the population which participates in clinical trials.

Participants who used a provider coupon code completed the headache diary monitoring period at higher rates, and took less time to complete the require days of headache diary entry, than people who received the app for free. This is consistent with previous literature which suggests greater incentives lead to higher adherence. Participants with a provider coupon had several incentives to adherence to the electronic headache diary compared to participants who received the app for free: 1) providers could monitor adherence; 2) providers could receive diary data; and 3) participants could receive maps showing associations between tracked factors and migraine occurrence (24). This is consistent with research regarding social desirability, which suggests that people want to be perceived as “good patients” by their providers, and may be more likely to adhere to various provider recommendations when providers have direct access to adherence information (28, 29). Future research should design randomized trials to explicitly evaluate differing types and levels of incentives to identify those most effective at improving adherence to electronic headache diary.

Participants in this study who paid for access to the application completed the headache diary monitoring period at higher rates, and took less time to complete the require days of headache diary entry than people who did not pay for access to the application, regardless of whether or not they had a physician code. Thus, adherence differences across account types were not merely due to incentives. Although these results are inconsistent with the literature which suggests increases in out-of-pocket costs reduce adherence to a variety of health care interventions (31, 31), they are consistent with social exchange theory, which suggests that increased investment in a treatment would improve adherence. Financial investment could result in greater motivation to adherence to electronic headache diary in people who paid for the app compared to people who received the app for free (32). Future studies should evaluate the impact of various types and amounts of investments (money, time) on adherence to electronic headache diaries.

In this study, frequently endorsing high levels of feeling “nervous/anxious/worried” was associated with poorer adherence to electronic headache diaries across outcomes evaluated. This is consistent with the literature that suggests high levels of anxiety may be a barrier to adherence. People with headache who present with frequent feelings of anxiety may be an at-risk population for non-adherence to electronic headache diaries. In the participants evaluated (age range 18 to 80 years old) younger age was associated with poorer adherence to electronic headache diaries across all outcomes evaluated. This is consistent with the broader chronic disease literature [e.g., self-monitoring of blood glucose in diabetes (33)], although it should be noted that headache disorders generally afflict a greater proportion of younger people than the majority of chronic diseases commonly studied. High quality data obtained from an adherent headache diary is essential for accurate headache disorder diagnosis, treatment planning, and outcome evaluation. If data quality is associated with a patient variable such as anxiety or age, these patient subgroups could be at risk of receiving suboptimal assessment and care. Future studies should evaluate whether clinically significant levels of anxiety are associated with adherence to headache self-monitoring, and methods to improve adherence to headache self-monitoring in these groups. For example, methods to reduce anxiety such as embedded stress management tools could be evaluated to improve adherence to electronic headache diaries. Alternately, methods designed specifically to improve adherence (such as increasing incentives or reducing the burden of diary entries) could target individuals with high anxiety.

Limitations

This is an observational study and cannot infer causality. This study evaluated participants who downloaded the application and met inclusion criteria. We did not require a physician confirmed headache diagnosis (either confirmed by the physician or self-reported by participant), therefore participants included may not have had a physician-diagnosed headache disorder. However, as headache diary applications become more prevalent, people with problematic headache attacks may use these apps throughout their journey in approaching and receiving healthcare; understanding how people with problematic headache naturalistically use headache diaries is relevant to people working with patients with headache.

This study used a specific electronic headache diary application (Curelator Headache ® now calles N1-Headache ®), which includes specific features that could influence adherence, including incentives like maps describing factors associated with headache attack onset and a user experience that allows for quick diary entries once learned; therefore, results may not generalize to other electronic headache diaries with difference incentives and entry methods. This study evaluated adherence to a very specific set of headache diary goals related to monitoring 90 days, and may not generalize to briefer or lengthier periods of keeping a headache diary, or other self-monitoring goals.

Not all factors evaluated are conducive to randomization (anxiety); however, future studies should consider randomized trial designs to explicitly evaluate the role of incentives and investments in adherence to headache self-monitoring. These studies should also take into account age and anxiety to identify whether certain types of incentives or investments may enhance adherence to self-monitoring more for certain types of people with headache.

This study used a non-clinical question to evaluate daily variation in anxiety. This brief question allowed us to query participants regarding anxiety every day during a headache diary, which would not have been possible with a longer measure of anxiety. However, is limited in that it has not been validated against clinical measures of anxiety. Certain levels of endorsed anxiety showed different relationships with the variety of adherence to self-monitoring outcomes evaluated. We chose to evaluate proportion of each anxiety score used to retain as much variability in the day-level anxiety variable as possible. These results could also be in part a result of an over-fitted model; however, we mitigated this possibility by using the AIC to select covariates for final model, which penalizes over-fitting, and verification of the primary analysis using a test set did not detect over-fitting. Further, sensitivity analyses with the primary outcome variable of completion told the same story as the main models presented: high levels of anxiety, regardless of how anxiety was aggregated for the purpose of analysis, were associated with lower odds of completion. Future studies should consider using clinical measures of anxiety to evaluate the relationship between the presence or absence of anxiety disorders (such as generalized anxiety disorder and panic disorder) and their relationships with adherence to keeping an electronic headache diary.

This study was specifically interested in the role of anxiety and incentives on adherence to an electronic headache diary because the broader behavioral medicine literature supported these hypotheses, and this study is limited to the variables evaluated. Hypotheses related to headache clinical characteristics (e.g., headache days/month) were not evaluated in this study, and could provide important areas for future research.

This study limited itself to evaluating adults, and found that higher age was associated with higher adherence to an electronic headache diary; however, mobile health devices that include self-monitoring are frequently used with children and adolescents (34). Future studies should evaluate differences in adherence to app-based headache diaries across the children/adolescents and adults, and identify potential mechanisms to improve adherence to headache diaries in the pediatric population.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements:

We would like to acknowledge Alec Mian, Steve Donoghue, and Abigail Lofchie for their invaluable assistance with the preparation of this paper. We would like to acknowledge all of the users and providers who have participated in collecting these data.

Funding: This study was supported by Curelator Headache ® and a training grant from the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke awarded to the first author (K23 NS096107 PI:Seng).

Abbreviations:

- M

mean

- SD

standard deviation

- IQR

interquartile range

- MIDAS

Migraine Disability Assessment

- VIF

Variance Inflation Factor

- AIC

Akaike’s Information Criterion

- ROC

Receiver Operating Characteristic

- HNB

Hurdle Negative Binomial

- OR

Odds Ratio

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Statement: Elizabeth K. Seng, Ph.D. has received funding from the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (K23 NS096107 PI:Seng) and served as a consultant for GlaxoSmithKline and Eli Lilly. Pablo Prieto, Gabriel Boucher and Marina Vives-Mestres, Ph.D., are employees of Curelator™.

References

- 1.Fox S, Duggan M. Tracking for health Washington, DC: Pew Research Center; 2013. http://www.pewinternet.org/2013/01/28/tracking-for-health/. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Karter AJ, Ackerson LM, Darbinian JA, D’Agostino RB Jr, , Ferrara A, Liu J, et al. Self-monitoring of blood glucose levels and glycemic control: the Northern California Kaiser Permanente Diabetes registry. Am J Med. 2001;111(1):1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Burke LE, Wang J, Sevick MA. Self-monitoring in weight loss: a systematic review of the literature. J Am Diet Assoc. 2011;111(1):92–102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vanwormer JJ, French SA, Pereira MA, Welsh EM. The impact of regular self-weighing on weight management: a systematic literature review. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2008;5:54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Malanda UL, Welschen LM, Riphagen II, Dekker JM, Nijpels G, Bot SD. Self-monitoring of blood glucose in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus who are not using insulin. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;1:Cd005060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mairs L, Mullan B. Self-Monitoring vs. Implementation Intentions: a Comparison of Behaviour Change Techniques to Improve Sleep Hygiene and Sleep Outcomes in Students. Int J Behav Med. 2015;22(5):635–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Huygens MW, Swinkels IC, de Jong JD, Heijmans MJ, Friele RD, van Schayck OC, et al. Self-monitoring of health data by patients with a chronic disease: does disease controllability matter? BMC Fam Pract. 2017;18(1):40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Armstrong L, Gossard G. Taking an integrative approach to migraine headaches. J Fam Pract. 2016;65(3):165–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kroon Van Diest AM, Ramsey R, Kashikar-Zuck S, Slater S, Hommel K, Kroner JW, et al. Treatment Adherence in Child and Adolescent Chronic Migraine Patients: Results from the Cognitive Behavioral Therapy and Amitriptyline Trial. Clin J Pain. 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ramsey RR, Ryan JL, Hershey AD, Powers SW, Aylward BS, Hommel KA. Treatment adherence in patients with headache: a systematic review. Headache. 2014;54(5):795–816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Krogh AB, Larsson B, Salvesen O, Linde M. A comparison between prospective Internet-based and paper diary recordings of headache among adolescents in the general population. Cephalalgia. 2016;36(4):335–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jamison RN, Jurcik DC, Edwards RR, Huang CC, Ross EL. A Pilot Comparison of a Smartphone App With or Without 2-Way Messaging Among Chronic Pain Patients: Who Benefits From a Pain App? Clin J Pain. 2017;33(8):676–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tassorelli C, Sances G, Allena M, Ghiotto N, Bendtsen L, Olesen J, et al. The usefulness and applicability of a basic headache diary before first consultation: results of a pilot study conducted in two centres. Cephalalgia. 2008;28(10):1023–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Singer AB. Mindfulness practice and perceived stress: a secondary analysis of a randomized controlled trial of mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for migraine. New York, NY: Yeshiva University; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rahman QA, Janmohamed T, Pirbaglou M, Ritvo P, Heffernan JM, Clarke H, et al. Patterns of User Engagement With the Mobile App, Manage My Pain: Results of a Data Mining Investigation. JMIR mHealth uHealth. 2017;5(7):e96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Seng EK, Seng CD. Understanding migraine and psychiatric comorbidity. Current opinion in neurology. 2016;29(3):309–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Smitherman TA, Davis RE, Walters AB, Young J, Houle TT. Anxiety sensitivity and headache: diagnostic differences, impact, and relations with perceived headache triggers. Cephalalgia. 2015;35(8):710–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Smitherman TA, Kolivas ED, Bailey JR. Panic disorder and migraine: comorbidity, mechanisms, and clinical implications. Headache. 2013;53(1):23–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Campos LN, Guimaraes MD, Remien RH. Anxiety and depression symptoms as risk factors for non-adherence to antiretroviral therapy in Brazil. AIDS Behav. 2010;14(2):289–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tucker JS, Burnam MA, Sherbourne CD, Kung FY, Gifford AL. Substance use and mental health correlates of nonadherence to antiretroviral medications in a sample of patients with human immunodeficiency virus infection. Am J Med. 2003;114(7):573–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Guo Y, Ding XY, Lu RY, Shen CH, Ding Y, Wang S, et al. Depression and anxiety are associated with reduced antiepileptic drug adherence in Chinese patients. Epilepsy Behav. 2015;50:91–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bautista LE, Vera-Cala LM, Colombo C, Smith P. Symptoms of depression and anxiety and adherence to antihypertensive medication. Am J Hypertens. 2012;25(4):505–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Price JS. Evolutionary aspects of anxiety disorders. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2003;5(3):223–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Donoghue S, Mian A, Peris F, Boucher G, Albert M. A new digital platform (Curelator Headache TM) to identify possible migraine triggers and warning signs in individuals and test triggers for causality. Cephalalgia. 2015;35(6S):40. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stewart WF, Lipton RB, Dowson AJ, Sawyer J. Development and testing of the Migraine Disability Assessment (MIDAS) Questionnaire to assess headache-related disability. Neurology. 2001;56(6 Suppl 1):S20–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hastie T, Tibshirani R, Friedman J. The elements of statistical learning: data mining, inference, and prediction Springer Series in Statistics. New York: Springer Science; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Team RC. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Campbell C, Scott K, Skovdal M, Madanhire C, Nyamukapa C, Gregson S. A good patient? How notions of ‘a good patient’ affect patient-nurse relationships and ART adherence in Zimbabwe. BMC Infec Dis. 2015;15:404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wagner G, Miller LG. Is the influence of social desirability on patients’ self-reported adherence overrated? J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2004;35(2):203–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Aziz H, Hatah E, Makmor Bakry M, Islahudin F. How payment scheme affects patients’ adherence to medications? A systematic review. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2016;10:837–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wanders JO, Veldwijk J, de Wit GA, Hart HE, van Gils PF, Lambooij MS. The effect of out-of-pocket costs and financial rewards in a discrete choice experiment: an application to lifestyle programs. BMC Public Health. 2014;14:870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nord WR. Social exchange theory: an integrative approach to social conformity. Psychol Bull. 1969;71(3):174–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mostrom P, Ahlen E, Imberg H, Hansson PO, Lind M. Adherence of self-monitoring of blood glucose in persons with type 1 diabetes in Sweden. BMJ Open Diabetes Res Care. 2017;5(1):e000342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Brannon EE, Cushing CC. A systematic review: is there an app for that? Translational science of pediatric behavior change for physical activity and dietary interventions. J Pediatr Psychol. 2015;40(4):373–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.