Abstract

TET2 is among the most frequently mutated genes in hematological malignancies, as well as in healthy individuals with clonal hematopoiesis. Inflammatory stress is known to promote the expansion of Tet2-deficient hematopoietic stem cells, as well as the initiation of pre-leukemic conditions. Infection is one of the most frequent complications in hematological malignancies and antibiotics are commonly used to suppress infection-induced inflammation, but their application in TET2 mutation-associated cancers remained underexplored. In this study, we discovered that Tet2 depletion led to aberrant expansion of myeloid cells, which was correlated with elevated serum levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines at the pre-malignant stage. Antibiotics treatment suppressed the growth of Tet2-deficient myeloid and lymphoid tumor cells in vivo. Transcriptomic profiling further revealed significant changes in the expression of genes involved in the TNF-α signaling and other immunomodulatory pathways in antibiotics-treated tumor cells. Pharmacological inhibition of TNF-α signaling partially attenuated Tet2-deficient tumor cell growth in vivo. Therefore, our findings establish the feasibility of targeting pro-inflammatory pathways to curtail TET2 inactivation-associated hematological malignancies.

1. Introduction

Ten-eleven Translocation 2 (TET2), a 5-methylcytosine dioxygenase, is frequently mutated in myeloid and lymphoid malignancies1–4. TET2 mutations are found in approximately 60% patients with chronic myelomonocytic leukemia (CMML)5–7 and in 10–83% of patients with T cell lymphomas8, 9. However, TET2 mutations are also detected in healthy individuals with clonal hematopoiesis10, suggesting that additional factors might be required to promote the malignant transformation of TET2-defective blood cells. Although Tet2-deficent mice show increased numbers of hematopoietic stem progenitor cells (HSPCs) and myeloid bias during HSPCs lineage specification, they seldom develop hematological malignancies1, 8, 11–13. Other factors, such as additional genetic defects14–18 and immunostimulation19, 20, are required to promote the full blown tumors. Therefore, these additional factors might serve as alternative therapeutic targets to treat cancers associated with TET2 mutations.

Deregulation of innate immunity and inflammatory signaling is closely associated with the occurrence of hematological malignancies21. Pro-inflammatory signals, arising from the tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), Toll-like receptors (TLRs) and/or interferon (IFN) pathways, can alter the proliferation, differentiation and self-renewal of HSPCs22, 23. Under pathophysiological conditions, epidemiological studies have revealed a strong positive correlation between autoimmune disorders and the incidence of myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS)24. Autoimmune phenotypes are also frequently observed in patients with T cell lymphomas25. Under inflammatory stress induced by lipopolysaccharides (LPS) or abnormal interleukin-6 (IL-6) production by microbiota19, 20, Tet2 deficient murine HSPCs exhibit a growth advantage, suggesting that inflammatory signaling could promote the malignant transformation of Tet2-deficient preleukemic HSPCs. Conversely, TET2-depleted malignant cells per se tend to enhance immune response and induce inflammation in the host.

Infection is one of the most frequent complications in patients with hematological malignancies, such as CMML and lymphoma26. Antibiotics are commonly used in cancer patients to fight against pathogen invasion and to attenuate the inflammatory response under pathological conditions. However prolonged treatment with antibiotics tends to disrupt the gut microbiota homeostasis and impair normal hematopoiesis27, 28. The therapeutic potential of antibiotics in the treatment of TET2-defective malignancies remains largely underexplored. In this study, we use CMML-like or CD4+ lymphoma derived from Tet2-deficient mice as the model systems to investigate whether and how antibiotic treatment impinges on tumor progression in vivo.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animal models and adoptive cell transfer

Animal studies were approved by the Institutional Animal Care Use Committee (IACUC) of the Institute of Biosciences and Technology, Texas A&M University. The Tet2KO mouse strain was reported previously12. CD45.1 recipient mice (B6.SJL-Ptprca Pepcb/BoyJ) were purchased from the Jackson Laboratory (Stock No: 002014). CMML-like (Gr1+Mac1+) cells were enriched in the bone marrow of Tet2KO mice and CD4+ lymphoma (CD4+) cells were purified from the spleen of Tet2KO mice. 2×106 cells were resuspended in 200 μl PBS and retro-orbitally injected into sub-lethally irradiated CD45.1 recipient mice (6–8 weeks old, female). The reconstitution efficiency of tumor cells was assessed by examining the CD45.2+ cells from peripheral blood in the recipient mice 3 weeks after adoptive cell transfer.

2.2. Antibiotics and inhibitors

Mice were fed with water for 10 days with an antibiotics cocktail containing the following: 1 g/L ampicillin (cat#: 45000–612), 0.5 g/L vancomycin (cat#: 97062–554), 1g/L neomycin (cat#: 97061–908) and 1 g/L metronidazole (cat#: BT134695; VWR) as previously reported27. Flavoring (20 g/L grape flavored Kool-Aid Drink) was added in the drinking water for all groups. The TNF-α inhibitor CC4047 (also called pomalidomide; Cat#:S1567) was purchased from Selleckchem and dissolved in 2% DMSO+30% PEG 300+2% Tween 80+ddH2O. The inhibitor was administered by intraperitoneal injection at a dose of 7mg / kg mice every day for 10 consecutive days.

2.3. Histological analysis

All collected tissues were fixed in 10% neutral-buffered formalin for 24 hrs at 4 °C. The tissue blocks were embedded in the paraffin after specimens treated with gradient alcohol dehydration. 7 μm-thick slices were cut for Hematoxylin and Eosin (H&E) staining. IHC staining was performed using the ImmPRESSTIM polymer detection system (Vector Laboratories) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Anti-CD3 (Abcam ab16669, 1:150) was used. All the slides were analyzed under a Nikon upright microscope.

2.4. Flow cytometry analysis

Bone marrow was harvested by flushing two femurs and two tibias. Cells were re-suspended in FACS buffer (PBS with 0.1% BSA, 2 mM EDTA) and incubated with anti-CD16/32 (ThermoFisher Scientific 14-0161-82, 1:200) for 15 min on ice. Cells were then incubated with indicated antibodies for 30 min at 4 °C in the dark, followed by washing with FACS buffer twice. For mouse lineage analysis in spleen and bone marrow, Mac-1 (ThermoFisher Scientific M1/70, 1:200) and Gr-1 (ThermoFisher Scientific RB6-8C5, 1:200) cells were used to define the myeloid lineage; CD4 (ThermoFisher Scientific GK1.5, 1:200) and CD8 (ThermoFisher Scientific 5H10-1, 1:200) were used to define the T cell lineage; B220 (ThermoFisher Scientific RA3–6B2, 1:200) and CD19 (ThermoFisher Scientific eBio1D3, 1:200) were used to define the B cell lineage; Ter119 (BioLegend Ter119, 1:100) and CD71 (BioLegend RI7217, 1:50) were used to define the erythroid lineage. For the bone marrow hematopoietic progenitor stem cell (HSPCs) analysis, a panel of biotin-conjugated antibodies against Ter-119 (BioLegend Ter119, 1:50), Gr1 (BioLegend RB6–8C5, 1:50), Mac-1 (BioLegend M1/70, 1:50), B220 (BioLegend RA3–6B2, 1:50), CD3 (BioLegend 17A2, 1:50) surface antigens were mixed as a cocktail for lineage labeling. A panel of antibodies containing Lin-biotin cocktail, Streptavidin-eFluor®450 (ThermoFisher Scientific 48-4317-82, 1:400), c-Kit APC (ThermoFisher Scientific 2B8, 1:200), Sca-1 PE/Cy7 (ThermoFisher Scientific D7, 1:200), CD150 PE (BioLegend TC15-12F12.2, 1:100) and CD48 FITC (BioLegend HM48–1, 1:100) were used for LSK/HSC labeling. A panel of antibodies containing Lin-biotin cocktail plus biotin-conjugated CD127 (ThermoFisher Scientific A7R34, 1:50), streptavidin-eFluor®450 (ThermoFisher Scientific 48-4317-82, 1:400), c-Kit APC (ThermoFisher Scientific 2B8, 1:200), Sca-1PE/Cy7 (ThermoFisher Scientific D7, 1:200), CD16/32-PE (ThermoFisher Scientific 93, 1:200) and CD34 FITC (ThermoFisher Scientific RAM34, 1:200) were used for CMP/GMP/MEP labeling.. Flow cytometry analysis was performed using LSRII (BD Biosciences) and data were analyzed with the FlowJo10 software package (FlowJo,LLC)

2.5. ELISA

Blood cells were collected by retro-orbital sinus puncture into 1.5 ml eppendorf tubes. Blood was allowed to clot at room temperature for 60 min before spinning at 3000 rpm for 15min at 4 °C. IFN gamma was measured by mouse IFN gamma ELISA Ready-set-go kit (ebioscience™, 88–7314), IL-1 beta was measured by eBioscience™ Mouse IL-1 beta ELISA Ready-SET-Go Kit (eBioscience™, 501129749), TNF alpha was measured by eBioscience™ Mouse TNF alpha ELISA Ready-SET-Go Kit (ebioscience™, 50-112-8954), IL-6 was measured by eBioscience™ Mouse IL-6 beta ELISA Ready-SET-Go Kit (ebioscience™, 50-172-18). The signal was detected using BioTek Cytation 5 Instrument at 450 nm (Fisher Scientific).

2.6. Real-time quantitative PCR (qPCR)

Total RNA was isolated from the RNeasy mini kit (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions, followed by reverse transcription using an AmfiRivert Platinum One cDNA Synthesis Master Mix (GenDEPOT). Real-time PCR (RT-PCR) was performed by using amfiSure qGreen Q-PCR Master Mix reagents (GenDEPOT) and LightCycler 96 real-time PCR system (Roche). Data were analyzed using the LightCycler software. The gene expression level was normalized to Gapdh. Primer sequences used for real-time RT-PCR were listed below:

Nfkbia forward: TGCCTGGCCAGTGTAGCAGTCTT

Nfkbia reverse: CAAAGTCACCAAGTGCTCCACGAT

Sgk1 forward: TCCTGAGGATGGGACATTTTCA

Sgk1 reverse: CTGCTCGAAGCACCCTTACC

Traf1 forward: CACTCCAGTTCTGTTTCCT

Traf1 reverse: CATATCCACTCTCTCTTCTCAC

Tnfaip2 forward: AGGAGGAGTCTGCGAAGAAGA

Tnfaip2 reverse: GGCAGTGGACCATCTAACTCG

B4galt1 forward: CACCACCACTGGACTGTTGT

B4galt1 reverse: ATGGGATGATGATGGCCACC

Nfil3 forward: TTCCCCCTCACGGACCAGGGA

Nfil3 forward: CATGGCGTCTTTCTTCTCGTCCGG

Gapdh forward: TCAACAGCAACTCCCACTCTTCCA

Gapdh reverse: ACCCTGTTGCTGTAGCCGTATTCA

2.7. Western blotting

Cells were lysed with TNTE buffer (150 mM NaCl, 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 0.5% Triton X-100, 5mM EDTA) supplemented with a protease inhibitor cocktail (GenDEPOT) and phosphatase inhibitor tablet (Sigma), and incubated on ice for 15 min. Cell debris was removed by centrifuging at 13,000 rpm for 10 min at 4°C. The protein was quantified by a Pierce BCA protein assay kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Samples were mixed with SDS sample buffer at 95°C for 15 min. Proteins were detected by using the West-Q Pico Dura ECL kit (GenDEPOT). Primary antibodies used for immunoblotting: Anti-Gapdh (Sigma G9545, 1:3000), Anti-Phospho-NF-κB p65 (Ser536) (Cell Signaling Technology 93H1 cat# 3033, 1:1000) Rabbit mAb, and Anti-NF-κB p65 (Cell Signaling Technology D14E12, cat# 8242, 1:1000) XP® Rabbit mAb.

2.8. Feces collection and bacterial culture

Fresh feces (2–3 pellets / mice) were collected from individual mice in an autoclaved chamber and dissolved in 1.5 ml PBS. The mixture were left on the bench for 20–30 min to allow debris to settle. Then the supernatant (50 μl) was gently transferred from each fecal homogenate onto a LB agar plate and incubated at 37 °C overnight.

2.9. RNA-seq library construction and data analysis

Total RNA was extracted from cells (n = 2 per condition) using the RNeasy mini kit (Qiagen) following manufacturer’s instructions. Poly A tail enriched RNA was enriched using a Poly(A)Purist Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific), followed by RNA-seq library preparation using an Ultra directional RNA library prep kit for Illumina (NEB) per manufacturer’s instruction. RNA-seq was performed using the Illumina Nextseq500 with the 75 bp single-ended running mode. The reads were mapped to mm10 using Bowtie2 with default parameters. The RefSeq gene annotation was obtained from the UCSC genome database. The number of reads mapped to each gene was counted using HTSeq (-m intersection-nonempty, -s no, -t exon, -i gene_id, http://www.huber.embl.de/users/anders/HTSeq/) with uniquely mapped reads as input. RPKM values were calculated with the raw read counts across all genes. The differentially expressed genes among the experimental groups were identified with negative binomial tests for pairwise comparisons between corresponding groups by employing the Bioconductor package DESeq2 using a corrected p value ≤ 0.05 and fold change thresholds of >= 2 or <= 0.5. GSEA function were used to analyze the function of significantly differentially expressed genes between two conditions. The Pearson correlation were used to compare reproducibility of all the analyzed samples. For the heat maps, row-wise scaled RPKM values across all samples were plotted using the function heatmap.2 in the R package gplots (www.r-project.org).

2.10. Accession numbers

The RNA-seq datasets have been deposited into GEO under the accession number GSE129886.

3. Results

3.1. Tet2 deficiency leads to variegated outcomes in the murine hematological system

Upon genetic ablation of Tet2, we observed spontaneous occurrence of hematological malignancies in Tet2 knockout (Tet2KO) mice, which exhibited a median survival of ~340 days (red curve, Figure S1A). By comparison, no gross abnormalities were observed in wild-type (WT) mice with the same genetic background during the 600-day experimental window. As revealed by histopathological and flow cytometry analyses, Tet2KO mice (n = 40) developed a wide spectrum of hematological malignancies, including myeloid (73%), T cell (23%), and B cell (4%) malignancies (Figure S1B). We further carried out histological analyses on major organs collected from Tet2KO mice before disease onset (disease free, DF), and Tet2KO mice which had developed T cell lymphoma or CMML (Figure S1C). In Tet2KO mice with lymphoma, we observed disruption of the lymph node structure as well as CD3+ tumor cell infiltration in the liver (Figure S1C, middle panel). In Tet2KO mice with CMML, we observed significantly increased numbers of monocytes and immature blood cells in the peripheral blood (Figure S1C, right panel). To further characterize the malignant phenotypes, we performed flow cytometric analysis to identify the affected cell types in Tet2KO mice (Figure S1D–F). In Tet2KO mice with CMML, we observed a significant expansion of Gr1+Mac1+ myeloid cells in both bone marrow and spleen, along with notable extramedullary hematopoiesis marked by an increase of CD71+Ter119+ erythroid cells in peripheral lymphoid tissues (Figure S1E–F). In Tet2KO mice with lymphoma, we observed a pronounced augmentation of CD4+ T cells in both bone marrow and spleen. No appreciable pathological phenotypes were found in Tet2KO mice before disease onset (< 6-months-old; Figure S1C, Figure S2A–C). Clearly, genetic depletion of Tet2 in mice led to the development of various hematological malignancies, a finding that concurs with recent observations reported by others group29.

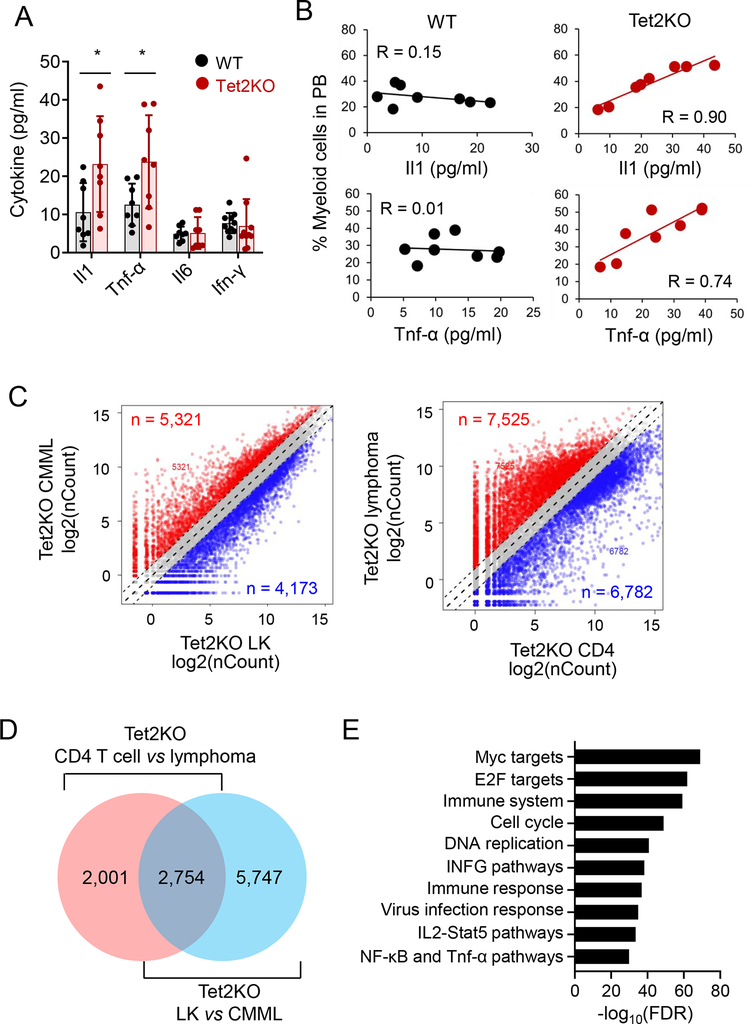

3.2. Positive correlation between serum cytokine levels and myeloid expansion in Tet2KO mice

Bacterial translocation-induced IL-6 production has been recently shown to promote the expansion of Tet2KO myeloid cells and drive pre-leukemic myeloproliferation19. To examine the correlation between cytokine production and myeloid expansion in Tet2KO mice, we measured the level of key pro-inflammatory cytokines, including IL-1, TNF-α, IL-6 and IFN-γ, in the serum of age- (16 weeks old) and gender-matched WT and Tet2KO mice before tumor onset. We observed significant upregulation of IL-1 and TNF-α levels in Tet2KO mice compared with the WT group (Figure 1A). Next, we measured the percentage of Gr1+Mac1+ myeloid cells in the peripheral blood obtained from both WT and Tet2KO mice, with the goal of establishing the correlation between serum cytokine levels and myeloid cell expansion. We observed a strong positive correlation between the IL1 or TNF-α levels and the percentage of myeloid cells in the peripheral blood for the Tet2KO group but not the WT group (Figure 1B). These data are consistent with the previously reported correlation between chronic inflammatory conditions and myeloid malignancies30.

Figure 1. Tet2KO malignant cells displayed an abnormal innate immune phenotype.

(A) Serum cytokine levels (IL-1, TNF-α, IL-6 and IFN-γ) measured in the peripheral blood of WT and Tet2KO mice. (n = 8 mice per group, * p < 0.05, by two-tailed Student’s t-test)

(B) The correlation between the percentage of myeloid cells (Mac1+Gr1+) and serum cytokine levels (IL-1 and TNF-α) in WT and Tet2KO mice.

(C) Scatter plot of the RNA-seq expression data to identify differentially expressed genes (DEGs) in Tet2KO LK vs CMML (Mac1+Gr1+cKithigh) cells (left), and Tet2KO CD4+ T cells vs CD4+ lymphoma cells (right).

(D) Comparison of differentially expressed genes (DEGs) between CD4+ T cells from disease-free Tet2KO mice and Tet2KO CD4+ lymphoma cells, or between Lin-Kit+ cells from disease-free Tet2KO mice and Tet2KO CMML-like cells.

(E) GSEA analysis of overlapping DEGs (n = 3,039) depicted in panel (C).

In order to identify the pathways that are important to promote the malignant transformation of Tet2-deficient blood cells, we next compared the transcriptome profiles of Tet2-deficient non-cancerous (Tet2KO lin−cKit+ (LK) or CD4+ T cells, isolated from mice < 6 months old and disease free) and tumor tissues (Tet2KO lin−cKit+Mac1+Gr1+ CMML-like or CD4+ lymphoma cells) using RNA-seq (Figure S3A). We identified a total of 8,501 differentially expressed genes (DEGs) between Tet2KO LK cells and Tet2KO CMML-like cells, and 4,755 DEGs between Tet2KO CD4+ T cells and Tet2KO lymphoma cells (Figure 1C). In order to identify the common affected genes by Tet2 deletion, we identified total of 2,754 overlapped DEGs between tumor-free and malignant cells (Figure 1D). Further Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA) showed that the top identified DEGs included Myc and E2F target genes, as well as genes associated with key immunoinflammatory signaling pathways (Figure 1E), including the TNF pathways. Together, both phenotypic and transcriptomic analysis results converged to implicate inflammatory signaling as a key culprit responsible for the pathogenesis of Tet2 inactivation-associated hematological malignancies.

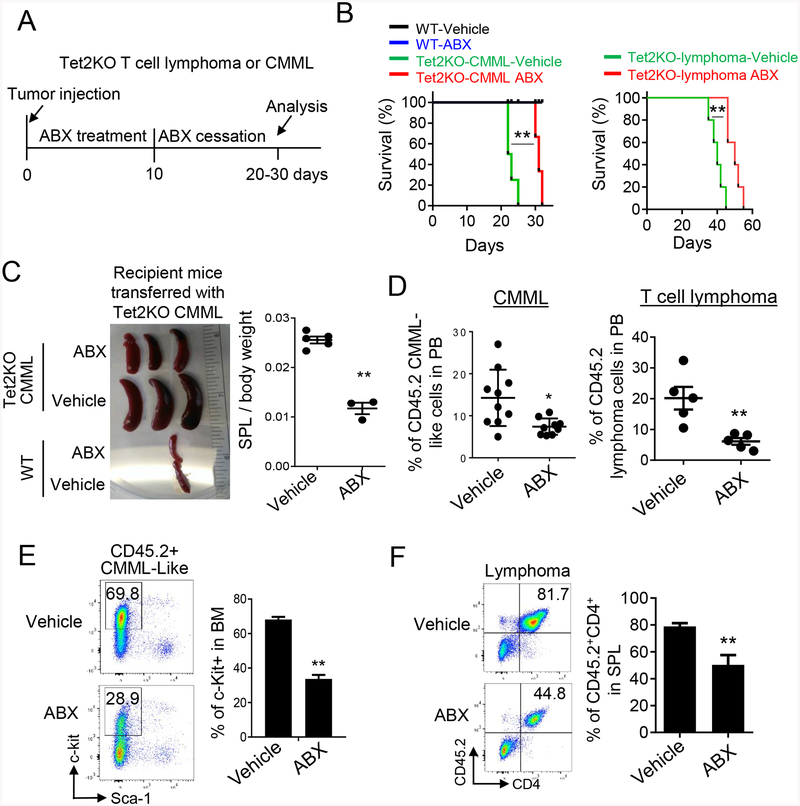

3.3. Antibiotic treatment suppresses the growth of Tet2 deficient hematological malignant cells

Tet2-deficient mice have been reported to exhibit bacterial translocation and aberrant inflammatory responses due to impaired small intestinal barrier function19. We reasoned that antibiotics might suppress translocated bacteria-induced immune response, and therefore hold promise to ameliorate infection in patients with hematological malignancies. To test this idea in vivo, we adoptively transferred Tet2KO CD4+ T cell lymphoma or Mac1+Gr1+ CMML-like tumor cells into sub-lethally irradiated CD45.1 recipient mice, followed by the treatment of a four-antibiotic cocktail (ABX treatment) of vancomycin, neomycin, ampicillin, and metronidazole (VNAM) in the drinking water (Figure 2A). After 10 day ABX treatment, we switched back to normal drinking water without the antibiotics cocktail and monitored the survival of each group (Figure 2A). Mice transferred with the same type of tumor cells without ABX treatment were used as control. To confirm the effectiveness of antibiotic treatment, we collected the feces of the mice with and without ABX treatment and performed aerobic culture of the supernatant collected from feces. No bacterial were observed in mice treated with the antibiotic cocktail (Figure S4A). Most notably, antibiotic treatment prolonged the survival of recipient mice (Figure 2B). By contrast, recipient mice transferred with WT cells showed no difference before and after ABX treatment (Figure 2B). Upon ABX treatment, we also observed a significant reduction of the spleen size of recipient mice transferred with Tet2KO CMML-like cells (Figure 2C), which is consistent with previous publication in ABX treated WT mice27. To further confirm that antibiotic treatment suppressed Tet2-deficient CMML-like or lymphoma cell growth, we analyzed the percentage of CD45.2+ tumor cells in the peripheral blood of recipient mice 10 days after antibiotic withdrawal. We observed a strong reduction of CD45.2+ CMML-like or lymphoma cells in the antibiotic treatment group, when compared with the untreated group (Figure 2D). In parallel, we observed a strong reduction of CD45.2+lin−c-Kit+Sca1− CMML-like cells or CD45.2+CD4+ lymphoma cells isolated from the bone marrow or spleen of recipient mice treated with ABX (Figure 2E–F). As control, no significant difference of Lin- HSPCs and downstream lineages in the bone marrow was observed in recipient mice transferred with WT bone marrow cells, in the presence or absence of ABX treatment 10 days after antibiotics withdrawal (Figure 3A–B, Figure S4B). This finding implies that the suppressive effect from antibiotic treatment is specific to Tet2KO malignant cells. In parallel, we monitored the effect of antibiotic treatment on the AF9 murine AML cell line transduced with a retrovirus encoding MLL-AF9 into lin-cKit+ murine bone marrow cells. No suppressive effect was observed in recipient mice transferred with AF9 murine AML cells upon ABX treatment (Figure 3C). To further investigate whether the antibiotic treatment directly suppresses Tet2-deficient malignant cells, we cultured Tet2KO CMML-like cells in methylcellulose with and without ABX treatment. We did not observe a significant difference in the total cell numbers between the ABX treated and untreated groups (Figure 3D). These results suggest that the observed suppressive effect is not due to direct toxicity imposed by the antibiotics per se.

Figure 2. Antibiotics cocktail (ABX) treatment suppresses the growth of Tet2KO tumor cells in vivo.

(A) Schematic of the experimental design and the timeline of antibiotics (ABX) treatment in CD45.1 recipient mice transferred with Tet2KO CMML or CD4+ lymphoma cells.

(B) (left) Kaplan-Meier survival curves of CD45.1 recipient mice transferred with WT (Mac1+Gr1+ myeloid cells) and Tet2KO CMML-like tumor cells treated with or without the VNAM antibiotics cocktail (ABX, n = 4 mice in the CMML group; n = 5 mice in the lymphoma group). (right) Kaplan-Meier survival curves of CD45.1 recipient mice transferred with Tet2KO CD4+ lymphoma cells treated with or without the VNAM antibiotics (ABX) cocktail (n = 4 mice). (** p < 0.001, long-rank test).

(C) Representative images of spleens (left) and statistical analysis (right) on the ratio of spleens/total body weight in recipient mice transferred with WT (Mac1+Gr1+ myeloid cells) or Tet2KO CMML-like tumor cells 26 days after cell injection.

(D) (left) The percentage of CD45.2+ Tet2KO CMML-like cells ((CD45.2+Lin−cfKit+Sca1+)) in the peripheral blood of CD45.1+ recipient mice treated with and without the VNAM antibiotics cocktail for 21 days after cell injection (n = 10 mice per group, * p < 0.05, by two-tailed Student’s t-test). (right) The percentage of CD45.2+CD4+ Tet2KO lymphoma cells in the spleen of CD45.1 recipient mice treated with and without the VNAM antibiotics cocktail at 36 days after lymphoma cell injection. (n = 5 mice per group, ** p < 0.005, two-tailed Student’s t-test).

(E) Representative flow cytometry (left) and statistical analysis results (right) of CD45.2+c-Kit+Sca-1+ Tet2KO CMML-like cells in the bone marrow of CD45.1 recipient mice treated with and without the VNAM antibiotics cocktail at 26 days after cell injection. (n = 3 mice per group, ** p < 0.005, by 2-tailed student’s t test).

(F) Representative flow cytometry (left) and statistical analysis results (right) of CD45.2+CD4+ Tet2KO T cell lymphoma cells in the spleen of CD45.1 recipient mice treated with and without the VNAM antibiotics cocktail at 36 days after cell injection. (n = 3 mice per group, ** p < 0.005, by 2-tailed student’s t test).

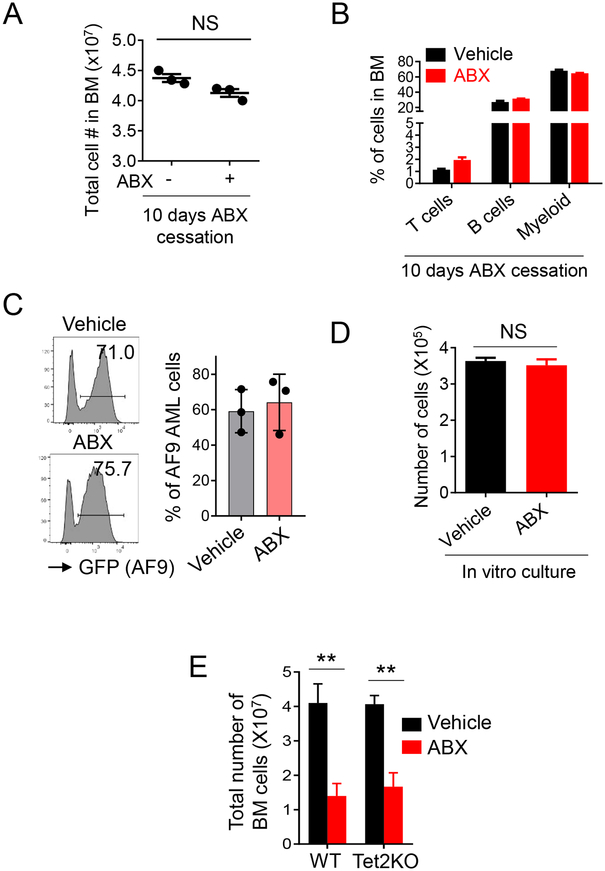

Figure 3. ABX treatment has no effects on normal hematopoiesis and AML cells bearing WT Tet2 in vivo after treatment withdrawal.

(A) The numbers of total bone marrow cells measured in CD45.1 recipient mice treated with and without the VNAM antibiotics cocktail at 26 days after CMML-like cell injection. (n = 3 mice per group)

(B) The percentage of T cells (CD4+ and CD8+), B220+CD19+ B cells and Gr1+Mac1+ myeloid cells in bone marrow cells measured in CD45.1 recipient mice treated with and without antibiotics at 26 days after Tet2KO CMML-like cell injection. (n = 3 mice per group)

(C) Flow cytometry profiles (left) and representative statistical analysis (right) of GFP+ AF9 AML cells measured in the bone marrow of CD45.1 recipient mice treated with and without the VNAM antibiotics cocktail at 20 days after AML cell injection. (n = 5 mice per group).

(D) Quantification of the numbers of Tet2KO CMML-like cells with and without the VNAM antibiotics cocktail treatment (25 mg/ml ampicillin, neomycin and metronidazole, 12.5 mg/ml vancomycin) for 7 days (n = 3 experiments per group). CMML-like cells were cultured in vitro with the MethoCult medium.

(E) Statistical analysis of the numbers of total bone marrow cells in normal WT and Tet2KO mice treated the VNAM antibiotics cocktail for 10 days. (n = 3 mice per group, ** p < 0.005, by 2-tailed student’s t test)

Antibiotics treatment has been shown to suppress normal hematopoiesis in mice27. We therefore examined how ABX treatment impinged on hematopoiesis in disease-free Tet2KO mice. A similar suppressive effect of antibiotics treatment was noted in both the WT and Tet2KO groups (Figure 3E). Consistent with earlier studies, antibiotics treatment reduced the total cell number in the bone marrow isolated from either WT or Tet2KO mice (Figure 3E). We also observed a reduction in the cell number of hematopoietic progenitors, including LSK (Lin−Sca1+cKit+), and myeloid progenitors (Figure S4C–D) in both WT and Tet2 deficient mice treated with antibiotics cocktail. These findings indicate that Tet2-deficient hematopoietic cells in disease-free mice behave that same as normal hematopoietic cells upon treatment with the antibiotics cocktail.

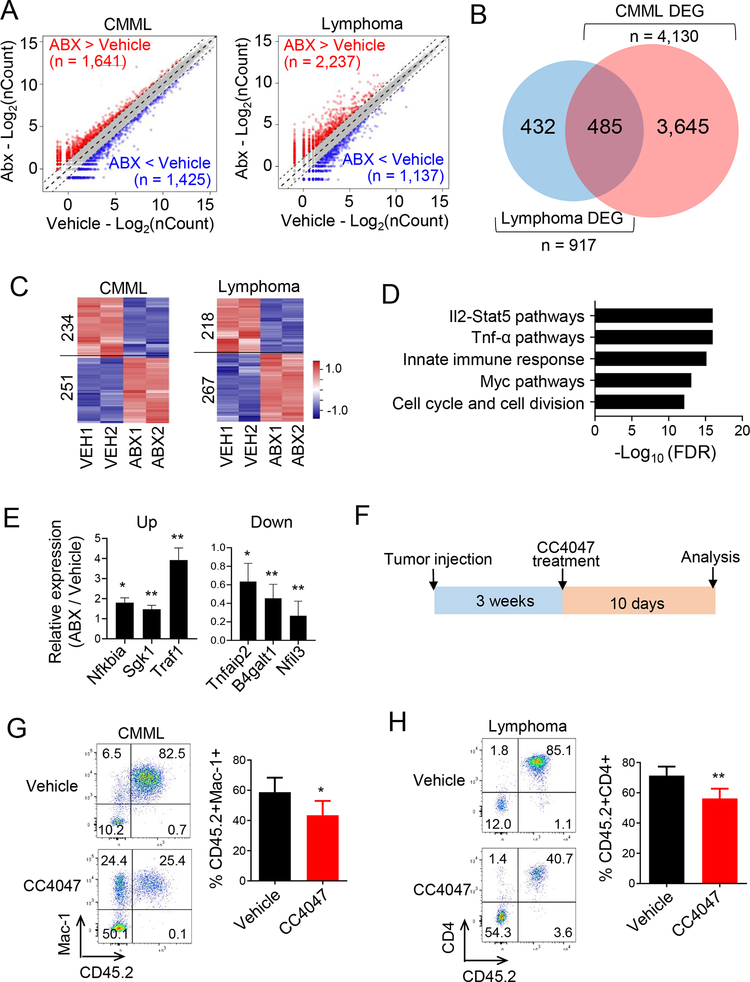

3.4. Antibiotic treatment suppresses TNF-α signaling in Tet2-deficient hematological malignancies

To identify the signaling pathways that contribute to ABX-induced tumor suppressive effect, we performed unbiased transcriptome analysis on Tet2-deficient CMML-like and lymphoma cells isolated from recipient mice treated with or without ABX. From the RNA-seq datasets, over 1,000 DEGs were identified from between the antibiotic treated and untreated groups (Figure 4A, Figure S5A). A comparison of DEGs between the CMML vs WT and lymphoma vs WT groups further revealed 485 overlapping genes that were altered after ABX treatment in both cancer types (Figure 4B, Table S1). GSEA further unveiled that these overlapping genes were closely associated immunomodulation processes, especially those involving the IL2-STAT5 and TNF-α pathways (Figure 4C–D, Figure S5B). These data are well aligned with the serum cytokine ELISA analysis results, in which upregulation of TNF-α was positively correlated with myeloid cell expansion in Tet2KO mice (Figure 1B). With real-time quantitative PCR, we further confirmed dysregulation of key genes involved in TNF-α signaling pathways in tumor cells isolated from the recipient mice after ABX treatment (Figure 4E).

Figure 4. Antibiotics treatment suppresses immune related signaling pathways in Tet2KO malignant cells.

(A) Scatter plot of the RNA-seq expression data to identify differentially expressed genes (DEGs) in Tet2KO CMML-like cells (left) and Tet2KO CD4+ lymphoma cells (right) between the vehicle and the antibiotics cocktail treatment (ABX) groups.

(B) Venn diagram showing the overlapping DEGs identified from the Tet2KO CMML-like and lymphoma groups treated with and without the VNAM antibiotics cocktail.

(C) Heatmap representation of DGEs identified in Tet2KO CMML (left) or CD4+ lymphomas treated with and without the VNAM antibiotics cocktail.

(D) GSEA analysis of overlapping DEGs identified in both the Tet2KO CMML and CD4+ lymphoma groups treated with and without the VNAM antibiotics cocktail.

(E) Use of qPCR to determine the relative expression of selected DEGs involved in the TNF-α pathway (ABX-over-vehicle ratio). (n = 3, * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.005, by two-tailed Student’s t-test).

(F) Experimental design of recipient mice transferred with Tet2KO CMML-like or CD4+ lymphoma cells treated with TNF-α inhibitor, CC4074 (also named as Pomalidomide), (7 mg/kg mice every day for 10 days) in vivo.

(G) Representative flow cytometry (left) and statistical analysis (right) of CD45.2+ Tet2KO CMML-like cells measured in the peripheral blood of CD45.1 recipient mice treated with and without CC4074 at 30 days after tumor cell injection. (n = 4 mice per group, * p < 0.05, by two-tailed Student’s t-test).

(H) Representative flow cytometry (left) and statistical analysis (right) of CD45.2+ Tet2KO lymphoma cells measured in the peripheral blood of CD45.1 recipient mice treated with and without CC4074 at 30 days after tumor cell injection. (n = 4 mice per group, ** p < 0.005, by two-tailed Student’s t-test).

To further confirm that TNF-α signaling pathway is a major target during antibiotic treatment in vivo, we treated recipient mice transferred with Tet2KO CMML-like or lymphoma tumor cells with a TNF-α inhibitor, CC4047 (Figure 4F). We observed a partial suppression of tumor growth in recipient mice treated with CC4047 for 10 days (Figure 4G–H). Immunoblot analysis further confirmed the decrease of the phosphorylated NF-κB p65 level, a downstream target of TNF-α in the CC4047 treated group (Figure S5C), thereby suggesting an efficient suppression of the TNF-α signaling pathway. These data demonstrated that the growth of Tet2-deficient hematological malignant cells partially depend on TNF-α signaling, and that antibiotic treatment suppresses tumor growth by altering TNF-α signaling.

4. Discussion

In the current study, we observed the development of different types of hematological malignancies in aged Tet2KO mice. Clearly, Tet2 deficiency increases the risk of malignant transformation in the hematopoietic system. Although it is still unclear how Tet2-deficient HSPCs are transformed to malignant cells, several studies have documented that Tet2-deficient HSPCs exhibit a growth advantage when responding to inflammatory stress20 and that the incidence of Tet2/3 deficient T cell lymphoma requires TCR signaling31. In the current study, we further observed a strong positive correlation between myeloid expansion and the serum pro-inflammatory cytokine levels in Tet2KO mice, but not in WT mice, suggesting that the inflammatory signaling might stimulate the expansion of Tet2KO HSPCs and ultimately lead to uncontrolled proliferation of Tet2-deficient cells.

To seek potential molecular mechanisms, we subsequently the gene expression profiles in two types of Tet2-deficient malignant tumor cells (CMML-like and T cell lymphoma cells) by using LK and CD4+ T cells as controls, respectively. We found genes involved in inflammation and cytokine signaling pathways are significantly altered in malignant cells. It still remains unclear how serum pro-inflammatory factors (Il-1 and TNF-α) are upregulated in Tet2-deficient mice. Previous studies reported that Tet2 depletion in mice tends to disrupt the intestinal barrier to cause aberrant bacterial translocation and cytokine production19. We therefore performed antibiotics treatment to reduce infection-mediated inflammatory response in recipient mice transferred with Tet2KO tumor cells. We observed that antibiotics treatment could suppress normal hematopoiesis in both WT and Tet2KO mice during the treatment. 10 days after antibiotics cessation, WT HSPCs could recover from hematopoiesis, which is consistent with an earlier report27. By comparison, the suppressive effect remained persistent in Tet2-deficient hematological malignant cells even after antibiotics withdrawal. Additionally, antibiotics treatment alone has no effect on MLL-AF9 AML cells, suggesting that antibiotics-mediated suppressive effect is specific to Tet2 deficient leukemia and lymphoma cells. This observation is consistent with previous report that inflammatory factors, such as TNF-α, favor Tet2-deficient clonal hematopoiesis30. Mechanistically, results from our RNA-seq and pharmacological inhibition studies point to the TNF-α signaling pathway as an important target to suppress tumor growth. At the current stage, it still remains unsolved how TNF-α signaling is activated and how antibiotic treatment suppresses TNF-related pathways in TET2-mutant malignancies in vivo. Based on a previous study32, hematological neoplasms- associated mutations within TET2 might alter its catalytic activity and result in impaired DNA methylation and hydroxymethylation in the genome. The dysregulation of the TNF-α signaling observed in Tet2-deficient malignant cells might partially arise from abnormal DNA methylation and/ or hydroxymethylation. Regardless, our findings establish that suppressing inflammatory pathways with antibiotics might benefit the clinical management of patients bearing hematological malignancies with somatic TET2 mutations.

Supplementary Material

Variegated hematological malignant phenotypes were observed in aged Tet2-deficient mice;

Serum cytokine production is positively correlated with myeloid expansion in Tet2KO mice;

Antibiotics treatment suppresses the growth of Tet2-deficient hematological malignancies in vivo;

The suppressive effect of antibiotics on Tet2-deficient neoplasms is partially mediated by inhibiting the TNF signaling pathway.

6. Acknowledgements

We are grateful for Dr. Jianjun Shen and the MD Anderson Cancer Center next-generation sequencing core at Smithville (CPRIT RP120348 and RP170002), and the Epigenetic core in Institute of Biosciences and Technology at the Texas A&M University. This work was supported by grants from Cancer Prevention and Research Institute of Texas (RR140053 to YH, to RP170660 to YZ, RP180131 to DS), the John S. Dunn Foundation Collaborative Research Award (to YH and YZ), the National Institute of Health grants (R01HL134780 and R01HL146852 to YH, R01GM112003 and R01CA232017 to YZ, R01AI136917 to KYK), the Welch Foundation (BE-1913 to YZ), the American Cancer Society (RSG-18-043-01-LIB to YH, RSG-16-215-01-TBE to YZ), and by an allocation from the Texas A&M University start-up funds (YH and DS).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

The original work reported herein has not been published previously and is not under consideration for publication elsewhere. The authors declared there is no conflicts of interest.

7. References

- 1.Delhommeau F, Dupont S, Della Valle V, James C, Trannoy S, Masse A, et al. Mutation in TET2 in myeloid cancers. N Engl J Med 2009. May 28; 360(22): 2289–2301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lemonnier F, Couronne L, Parrens M, Jais JP, Travert M, Lamant L, et al. Recurrent TET2 mutations in peripheral T-cell lymphomas correlate with TFH-like features and adverse clinical parameters. Blood 2012. August 16; 120(7): 1466–1469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tefferi A, Lim KH, Levine R. Mutation in TET2 in myeloid cancers. N Engl J Med 2009. September 10; 361(11): 1117; author reply 1117–1118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Couronne L, Bastard C, Bernard OA. TET2 and DNMT3A mutations in human T-cell lymphoma. N Engl J Med 2012. January 5; 366(1): 95–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Itzykson R, Kosmider O, Renneville A, Gelsi-Boyer V, Meggendorfer M, Morabito M, et al. Prognostic score including gene mutations in chronic myelomonocytic leukemia. J Clin Oncol 2013. July 1; 31(19): 2428–2436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tefferi A, Lim KH, Abdel-Wahab O, Lasho TL, Patel J, Patnaik MM, et al. Detection of mutant TET2 in myeloid malignancies other than myeloproliferative neoplasms: CMML, MDS, MDS/MPN and AML. Leukemia 2009. July; 23(7): 1343–1345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Grossmann V, Kohlmann A, Eder C, Haferlach C, Kern W, Cross NC, et al. Molecular profiling of chronic myelomonocytic leukemia reveals diverse mutations in >80% of patients with TET2 and EZH2 being of high prognostic relevance. Leukemia 2011. May; 25(5): 877–879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Quivoron C, Couronne L, Della Valle V, Lopez CK, Plo I, Wagner-Ballon O, et al. TET2 inactivation results in pleiotropic hematopoietic abnormalities in mouse and is a recurrent event during human lymphomagenesis. Cancer cell 2011. July 12; 20(1): 25–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chiba S. Dysregulation of TET2 in hematologic malignancies. Int J Hematol 2017. January; 105(1): 17–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Busque L, Patel JP, Figueroa ME, Vasanthakumar A, Provost S, Hamilou Z, et al. Recurrent somatic TET2 mutations in normal elderly individuals with clonal hematopoiesis. Nat Genet 2012. November; 44(11): 1179–1181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Moran-Crusio K, Reavie L, Shih A, Abdel-Wahab O, Ndiaye-Lobry D, Lobry C, et al. Tet2 loss leads to increased hematopoietic stem cell self-renewal and myeloid transformation. Cancer cell 2011. July 12; 20(1): 11–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ko M, Bandukwala HS, An J, Lamperti ED, Thompson EC, Hastie R, et al. Ten-Eleven-Translocation 2 (TET2) negatively regulates homeostasis and differentiation of hematopoietic stem cells in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2011. August 30; 108(35): 14566–14571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Li Z, Cai X, Cai C, Wang J, Zhang W, Petersen BE, et al. Deletion of Tet2 in mice leads to dysregulated hematopoietic stem cells and subsequent development of myeloid malignancies. Blood 2011. July 29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang X, Su J, Jeong M, Ko M, Huang Y, Park HJ, et al. DNMT3A and TET2 compete and cooperate to repress lineage-specific transcription factors in hematopoietic stem cells. Nat Genet 2016. September; 48(9): 1014–1023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zang S, Li J, Yang H, Zeng H, Han W, Zhang J, et al. Mutations in 5-methylcytosine oxidase TET2 and RhoA cooperatively disrupt T cell homeostasis. J Clin Invest 2017. August 01; 127(8): 2998–3012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shih AH, Jiang Y, Meydan C, Shank K, Pandey S, Barreyro L, et al. Mutational cooperativity linked to combinatorial epigenetic gain of function in acute myeloid leukemia. Cancer Cell 2015. April 13; 27(4): 502–515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Muto T, Sashida G, Oshima M, Wendt GR, Mochizuki-Kashio M, Nagata Y, et al. Concurrent loss of Ezh2 and Tet2 cooperates in the pathogenesis of myelodysplastic disorders. J Exp Med 2013. November 18; 210(12): 2627–2639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cortes JR, Ambesi-Impiombato A, Couronne L, Quinn SA, Kim CS, da Silva Almeida AC, et al. RHOA G17V Induces T Follicular Helper Cell Specification and Promotes Lymphomagenesis. Cancer Cell 2018. February 1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Meisel M, Hinterleitner R, Pacis A, Chen L, Earley ZM, Mayassi T, et al. Microbial signals drive pre-leukaemic myeloproliferation in a Tet2-deficient host. Nature 2018. May; 557(7706): 580–584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cai Z, Kotzin JJ, Ramdas B, Chen S, Nelanuthala S, Palam LR, et al. Inhibition of Inflammatory Signaling in Tet2 Mutant Preleukemic Cells Mitigates Stress-Induced Abnormalities and Clonal Hematopoiesis. Cell Stem Cell 2018. December 6; 23(6): 833–849 e835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ganan-Gomez I, Wei Y, Starczynowski DT, Colla S, Yang H, Cabrero-Calvo M, et al. Deregulation of innate immune and inflammatory signaling in myelodysplastic syndromes. Leukemia 2015. July; 29(7): 1458–1469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.King KY, Goodell MA. Inflammatory modulation of HSCs: viewing the HSC as a foundation for the immune response. Nat Rev Immunol 2011. September 9; 11(10): 685–692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pietras EM. Inflammation: a key regulator of hematopoietic stem cell fate in health and disease. Blood 2017. October 12; 130(15): 1693–1698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dalamaga M, Petridou E, Cook FE, Trichopoulos D. Risk factors for myelodysplastic syndromes: a case-control study in Greece. Cancer Causes Control 2002. September; 13(7): 603–608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cortes JR, Palomero T. The curious origins of angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma. Curr Opin Hematol 2016. July; 23(4): 434–443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Khayr W, Haddad RY, Noor SA. Infections in hematological malignancies. Dis Mon 2012. April; 58(4): 239–249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Josefsdottir KS, Baldridge MT, Kadmon CS, King KY. Antibiotics impair murine hematopoiesis by depleting the intestinal microbiota. Blood 2017. February 09; 129(6): 729–739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yan H, Baldridge MT, King KY. Hematopoiesis and the bacterial microbiome. Blood 2018. August 9; 132(6): 559–564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pan F, Wingo TS, Zhao Z, Gao R, Makishima H, Qu G, et al. Tet2 loss leads to hypermutagenicity in haematopoietic stem/progenitor cells. Nat Commun 2017. April 25; 8: 15102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Abegunde SO, Buckstein R, Wells RA, Rauh MJ. An inflammatory environment containing TNFalpha favors Tet2-mutant clonal hematopoiesis. Exp Hematol 2018. March; 59: 60–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tsagaratou A, Gonzalez-Avalos E, Rautio S, Scott-Browne JP, Togher S, Pastor WA, et al. TET proteins regulate the lineage specification and TCR-mediated expansion of iNKT cells. Nat Immunol 2017. January; 18(1): 45–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ko M, An J, Bandukwala HS, Chavez L, Aijo T, Pastor WA, et al. Modulation of TET2 expression and 5-methylcytosine oxidation by the CXXC domain protein IDAX. Nature 2013. May 2; 497(7447): 122–126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.