Abstract

Importance:

Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (BPPV) is a common cause of acute dizziness. Strong evidence exists for diagnosing BPPV using the Dix-Hallpike Test (DHT) and treating it with the canalith repositioning maneuver (CRM). Despite this, both are infrequently used in the emergency department (ED).

Objective:

As an early method to evaluate a BPPV-focused educational intervention, we evaluated whether an educational intervention improved ED provider performance on hypothetical stroke and BPPV cases delivered by vignette.

Design:

A randomized, controlled, educational intervention study in ED physicians. The intervention aimed to promote the appropriate use of the DHT and CRM. A BPPV vignette, a stroke-dizziness (safety) vignette, and vignette scoring schemes (higher scores indicating more optimal care) used previously established vignette methodology.

Setting:

We recruited participants at the exhibitor hall of an emergency medicine annual meeting.

Participants:

We recruited 48 emergency physicians. All were board certified or residency trained and board eligible. All were engaged in the active practice of emergency medicine. None were trainees.

Interventions:

Intervention group: a narrated, educational presentation by computer followed by the clinical vignettes. Control group: Received no educational intervention and completed the clinical vignettes – intended to mirror current clinician practice.

Main outcome measure:

Primary endpoint: total score (out of 200 points) on a vignette-based scoring instrument assessing the performance of history, physical, and diagnostic testing on hypothetical stroke and BPPV cases.

Results:

The efficacy threshold was crossed at the interim analysis. The intervention group had higher performance scores compared with controls (113.2 versus 68.6, p<0.00001). BPPV and safety sub-scores were both significantly higher in the intervention group. Sixty-two percent of the intervention group planned to use the DHT versus 29% of controls. After the vignette described characteristic BPPV nystagmus, 100% of the intervention group planned to use the CRM versus 17% of controls.

Conclusions and relevance:

The educational intervention increased provider performance in dizziness vignettes, including more frequent appropriate use of the DHT/CRM. These findings indicate the intervention positively influenced planned behavior. Future work is needed to implement and evaluate this intervention in clinical practice.

Introduction

Dizziness is a common presenting complaint in emergency departments.1 A broad spectrum of conditions can manifest as dizziness2 ranging from self-limited disorders to serious life threatening posterior circulation stroke.3, 4 One specific form of dizziness that commonly prompts patients to seek care is benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (BPPV).5, 6 The gold standard diagnostic test for BPPV is the Dix-Hallpike test (DHT), in which a positive finding is indicated by a characteristic transient nystagmus triggered by lying down to a head extended back position.7, 8 The treatment for BPPV is the evidence-based canalith repositioning maneuver (CRM), which is highly effective and only takes minutes to perform.9, 10 The use of the Dix-Hallpike test and CRM have several advantages including the rapid identification of BPPV without need for additional testing, and the ability to initiate quick and effective treatment. Clinical trials specific to emergency medicine have validated their use in this patient population.11

Despite the evidence in favor of the frequent use of the simple, low-cost Dix-Hallpike test to screen for BPPV and the CRM to treat it, these procedures are rarely used in routine emergency medicine practice.6, 12, 13 Reasons that ED physician underuse these include relying on the history of present illness (HPI) – rather than the exam – to diagnose BPPV, misconceptions about the characteristic BPPV nystagmus, and prior negative experiences using the DHT/CRM.13 The negative experiences likely stem from applying the DHT/CRM in patients who do not have BPPV, which relates back to providers relying on the HPI to guide the care and misconceptions about the BPPV characteristic nystagmus.13 These issues likely result from outdated training on the approach to dizziness in the ED.13–16

Our team has initiated a BPPV-focused implementation project aimed at increasing appropriate use of the DHT/CRM within EDs.13 An important part of this project is the development of educational materials to address previously identified barriers and facilitators to DHT and CRM use.[cite] The educational materials incorporate up-to-date evidence, emphasize the critical components of the exam, and de-emphasize the HPI elements that substantially overlap various causes of dizziness. In the current study, we aimed to evaluate the materials’ impact on physician planned care using a vignette method previously validated against both clinical observation and chart review of physicians in practice. This vignette method allows us to obtain early information about the potential effects and safety of the intervention. We will use the results of this vignette research to inform subsequent implementation and evaluation in clinical practice.

Methods

Study Design

This was a randomized, controlled, educational intervention study that included residency trained or board-certified emergency physicians practicing in the United States. Using a multidisciplinary panel (emergency medicine, neurology, otolaryngology), we developed two simulated clinical vignettes and scoring rubrics. We followed previously validated vignette-based research methodology (supplemental material).17, 18 In this prior work, Peabody and colleagues found similar measurements of quality of care in the ambulatory setting when directly comparing vignettes, chart abstraction, and observation of standardized patients. We designed one vignette to be a typical BPPV presentation, enabling evaluation of participant’s approach to the diagnosis and management of BPPV, while a second vignette described a stroke-dizziness presentation. The intent of the stroke-dizziness vignette was to evaluate the safe use and interpretation of the BPPV test and treatment, and the possibility that education about BPPV could improve safe practices even in non-BPPV presentations. Briefly, clinicians responded in each vignette to sequential open-ended questions from 5 domains. They were first presented with brief information about the reason for the visit, and then asked regarding what elements of the history would be important. Then after additional information about the history was revealed, they were asked about what elements of physical examination would be performed. Then, after physical exam findings were revealed, they were asked about what types of diagnostic and lab testing they would perform. Finally, after the results of these tests were given, the respondents were asked to give their final diagnosis, disposition, and treatment plan. The scenario instruments were pilot-tested on an emergency physician with experience in acute stroke and clinical trials prior to implementation and slight adjustments were made based on feedback. Participants were randomized to receive educational intervention or no education prior to responding to the vignettes. Since our focus was on physicians in practice, we did not provide a control educational intervention such as a handout or book chapter. As such, the control group was intended to estimate how that group of physicians would approach the case in routine clinical practice. The current investigation aimed to assess for and address knowledge gaps in emergency department dizziness care in order to plan a future intervention that would include didactics and potentially other educational strategies such as hands-on training.

Study Population

We recruited practicing emergency physicians at the 2014 Annual Meeting of the American College of Emergency Physicians in Seattle, Washington. Emergency physicians were eligible to participate if they practiced in the United States and had completed an Emergency Medicine Residency, or were board certified by the American Board of Emergency Medicine. We provided participants with a $50 cash incentive.

Development of Study Materials

Initially, we conducted semi-structured interviews of emergency physicians to understand the knowledge, attitudes and behaviors regarding dizziness care processes.13 This work revealed that the majority of ED physicians were not aware of the BPPV evidence base, that they typically over-emphasized information from the history of present illness when making decisions, failed to perform nystagmus assessments and/or harbored misconceptions about nystagmus, and generally had tried the DHT and CRM in the past, but had negative experiences with them. A multi-disciplinary panel (emergency medicine, neurology, otolaryngology, internal medicine, experimental psychologist, and implementation scientist) then developed an educational intervention that used the framework of the Theory of Planned Behavior to address these issues with the goal of increasing behavioral intent for doing DHT and CRM.19

Randomization

Using randomization.com, we developed a sequence of 96 codes in blocks of four. Each block contained four groups including the combinations of vignette order (dizziness-stroke first versus BPPV first) and intervention (received intervention versus did not receive). A separate investigator, not involved with data collection, generated the sequence. After a participant agreed to the study, their vignette order and intervention status was revealed and he or she was directed to a computer. The computer either immediately started the vignettes for the control group (if randomized to no education) or delivered the educational intervention (if randomized to receive education) before showing the vignettes.

Study Interventions

The educational intervention was a PowerPoint presentation that presented evidence-based BPPV content, and included narration, video examples of characteristic nystagmus patterns, and video demonstrations of the Dix-Hallpike test and CRM. The educational intervention was delivered individually to each physician using laptop computers with noise cancelling headphones in the exhibit hall within the conference location. It lasted about 10 minutes.

Study Measurements Endpoints/Outcome

The participants gave free text responses to scenarios and questions from the vignette (supplemental material). The participants needed to answer questions and could not go backward to adjust prior responses. As an example, the patient’s chief complaint would be given and then a free text question asks “what elements of the history would you take?”

Study team members blinded to the treatment group assignment reviewed and scored the responses. The multi-disciplinary clinician panel, comprised of three neurologists, an emergency physician, and an otolaryngologist, developed a score sheet for the BPPV case and the dizziness-stroke case following the Peabody scoring methods.17, 18 When scoring responses, no partial credit was given. All points were assigned when evidence of the action was available in the participant responses. As an example, 40 points were given for admitting the stroke case to the hospital or observation (and zero points were given for discharging the patient from the ED) and this was counted as part of the safety subscale. The final total score was thus a combination of a “BPPV subscore” and a “safety subscore.” The BPPV score emphasized appropriate BPPV-focused planned actions (e.g., using the Dix-Hallpike test and the CRM in the BPPV case). The safety score emphasized safe planned actions (e.g., general neurological exam in both cases, and head imaging, admission, and not diagnosing BPPV in the stroke-dizziness vignette). The number of points (relative weights) for each clinical action (history taking, examination, management and disposition) were reviewed by the multidisciplinary committee iteratively and the group reached consensus on the weightings via a series of meetings. A maximum of 200 points could be assigned (Tables 1 and 2), with higher scores indicating more optimal care. Two investigators initially scored ten respondents and discussed any disagreements. A third investigator, also blinded to the intervention group assignment, adjudicated any disagreements that the two initial reviewers could not resolve. We pre-specified that a single study team member could score the remaining responses after achieving 85% agreement with the second investigator.

Table 1:

Scoring for the BPPV care process items (BPPV score)

| Weight | |

|---|---|

| (TOPIC 1) Look for patterns of nystagmus at rest (which would render BPPV unlikely) | |

| Nystagmus Generic Mention [In BPPV case] | 4 |

| Nystagmus Generic Mention [In stroke case] | 4 |

| Spontaneous nystagmus mention [In BPPV case] | 8 |

| Spontaneous nystagmus mention [In stroke case] | 8 |

| Gaze-evoked nystagmus generic [In BPPV case] | 8 |

| Gaze-evoked nystagmus generic [In stroke case] | 8 |

| (TOPIC 2) Perform the DHT when appropriate & know what constitutes a +DHT for BPPV | |

| Any mention to perform DHT [In BPPV case] | 4 |

| Any mention to perform DHT [In stroke case] | 4 |

| DHT nystagmus (assess for nystagmus on DHT) [In BPPV case] | 4 |

| DHT nystagmus (assess for nystagmus on DHT) [In stroke case] | 4 |

| DHT TRIGGERED nystagmus (mention to assess for TRIGGERED nystagmus) [In BPPV case] | 3 |

| DHT TRIGGERED nystagmus (mention to assess for TRIGGERED nystagmus) [In stroke case] | 3 |

| DHT TRANSIENT nystagmus [In BPPV case] | 8 |

| DHT TRANSIENT nystagmus [In stroke case] | 8 |

| DHT to EACH SIDE [In BPPV case] | 1 |

| DHT to EACH SIDE [In stroke case] | 1 |

| (TOPIC 3) Make a diagnosis of BPPV in the correct clinical context | |

| ‘Did list BPPV as the #1 diagnosis’ [In BPPV case] | 5 |

| ‘Did NOT list BPPV as the #1 diagnosis’ [In stroke case] | 5 |

| (TOPIC 4) Perform the Epley if the DHT is positive for triggered & transient nystagmus | |

| ‘Did perform the Epley (or refer for Epley)” [In BPPV case] | 7 |

| ‘Did NOT perform the Epley (or refer for Epley)” [In stroke case] (less points) | 3 |

| TOTAL | 100 |

Table 2:

Scoring for the safety items of vignettes (safety score)

| Weight | |

|---|---|

| (TOPIC 1) Did not worsen HPI information gathering regarding neurologic symptoms. | |

| ‘Did ask about ‘any other symptoms’ | 0.5 |

| ‘Did ask about any unilateral face, arm, or leg weakness (inclusive of ‘any weakness or any focal symptoms’). | 1 |

| “Did ask about changes in speech’ | 1 |

| ‘Did ask about sensory symptoms (numbness, tingling)’ | 1 |

| ‘Did ask about visual changes’ | 0.5 |

| TOTAL TOPIC 1 | |

| (TOPIC 2) Did not worsen planned Neuro examination. ‘ | |

| ‘Did generic neurologic exam’ [In BPPV case] | 1 |

| ‘Did generic neurologic exam’ [In stroke case] | 1 |

| ‘Did exam for asymmetric facial weakness (or CN exam or NIHSS)’ [In BPPV case] | 1 |

| ‘Did exam for asymmetric facial weakness’ [In stroke case] | 1 |

| “Did exam for speech/language disturbance’ [In BPPV case] | 1 |

| “Did exam for speech/language disturbance’ [In stroke case] | 1 |

| ‘Did exam for weakness’ [In BPPV case] | 1 |

| ‘Did exam for weakness’ [In stoke case] | 1 |

| ‘Did exam of visual fields’ [In BPPV case] | 1 |

| ‘Did exam of visual fields’ [In stroke case] | 1 |

| ‘Did sensory exam’ [In BPPV case] | 1 |

| ‘Did sensory exam’ [In stroke case] | 1 |

| ‘Did coordination assessment’ [In BPPV case] | 1 |

| ‘Did coordination assessment’ [In stroke case] | 1 |

| ‘Did gait assessment’ [In BPPV case] | 1 |

| ‘Did gait assessment’ [In stroke case] | 1 |

| TOTAL TOPIC 2 | |

| (TOPIC 3) Did not fail to order head imaging in correct clinical context (do not order unnecessary tests?). | |

| ‘Did order head imaging’ [In stroke case] | 20 |

| (TOPIC 4) Admit appropriate patients to hospital | |

| ‘Did admit patient to the hospital’ [In stroke case] | 40 |

| (TOPIC 5) Also including other safety issues here | |

| ‘Did NOT list BPPV as #1 diagnosis’ [In stroke case] | 20 |

| TOTAL | 100 |

We collected additional information after the vignettes via a survey with Likert-based responses to elicit the respondents’ behavioral intentions regarding future BPPV patients and their predicted level of confidence in future evaluation of patients. Like the main analysis, we summarized the proportions responding to each question by treatment versus control group. Given the small sample size and the multiple categories, we did not perform formal hypothesis testing on the secondary outcomes.

Sample Size and Statistical Analysis

We used means and variances observed from prior vignette work in other disease settings to estimate sample size needed. Mean vignette scores from previous work ranged from 65.1 to 76.3 per vignette out of 100 total with standard deviations of 5.4 to 9.3.17 Assuming 90% power and significance levels from 0.01 to 0.05 we used an effect size of a 15% higher score in the intervention group. A total sample size for both groups of 14 to 54 was estimated. We inflated this to 96 total subjects as we were investigating original vignettes in a novel disease area and it was unclear whether the variance estimates from the prior vignette based studies would apply to our work.

Prior to the enrollment of any subjects, we defined pre-specified boundaries for a planned interim analysis after 48 individuals. The purpose of the interim analysis was to enable the study team to learn early on whether the intervention as measured with this scoring system was effective, futile, or not yet clear. The pre-specified boundaries for the interim analysis, determined using the Hwang-Shih-DeCani spending function methods in the gsDesign package of R, were as follows: efficacy threshold, p ≤0.003; futility threshold, p ≥ 0.2622; uncertainty range, p>0.003 to <0.2622.20, 21 Based on interim analysis, the final analysis threshold for efficacy was determined to be p≤0.022. Because we were interested in the hypothesis of intervention being superior to control, we employed a one-sided test at the alpha level of 0.025. Our planned pre-specified primary analysis was the comparison of the total scores for the intervention versus control groups using a Student’s t test. We also specified analyses of the safety score and the BPPV score to ensure that the BPPV score was not increasing at the expense of safely diagnosing and treating the patient described in the stroke vignette. No adjustments for multiple comparisons were pre-specified.

Sensitivity Analyses

We fit a linear regression model with an indicator variable for treatment group, and planned to add meaningful covariates from inspection of baseline covariates across the treatment and control groups, to ensure that confounders did not change the results.

Human Subjects Protection

The University of Michigan Institutional Review Board (IRBMED) reviewed this protocol and determined it to be exempt research under CFR 46.101.

Results

Study Population

We recruited 48 subjects. They were mostly male, and many had recently completed residency (Table 3). Over 70% of the intervention group had completed residency since 2001, versus about 40% of the control group. A large proportion of both groups were faculty at EM residencies.

Table 3:

Characteristics of the participants

| Count | % | Count | % | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 20 | 83.3% | 17 | 70.8% |

| Female | 4 | 16.7% | 7 | 29.2% | |

| Faculty at EM Residency Currently | Yes | 14 | 60.9% | 17 | 70.8% |

| No | 9 | 39.1% | 7 | 29.2% | |

| Ethnicity | Not Hispanic | 20 | 83.3% | 22 | 70.8% |

| Hispanic | 0 | 0 | 1 | 4.2% | |

| Not Disclosed | 4 | 16.7% | 1 | 4.2% | |

| Race | American Indian / Alaska Native | 1 | 4.2% | 0 | 0% |

| Asian | 2 | 8.3% | 3 | 12.5% | |

| Black or African American | 1 | 4.2% | 0 | 0% | |

| White | 19 | 79.2% | 21 | 87.5% | |

| Not disclosed | 1 | 4.2% | 0 | 0% | |

| Residency Graduation Year | 1980 or earlier | 0 | 0% | 1 | 4.2% |

| 1981–1990 | 8 | 33.3% | 1 | 4.2% | |

| 1991–2000 | 6 | 25% | 5 | 20.8% | |

| 2001 – 2012 | 10 | 41.7% | 17 | 70.8% |

Primary Endpoint Analysis

We analyzed the data as per the planned interim analysis. The p-value for the primary outcome was lower than the threshold pre-defined, and therefore the study was stopped after 48 subjects. The intervention group had a significantly higher combined score of 113.2 (SD 29.1) versus 68.6 (SD 36.4) for the control group (p<0.0001). The intervention group had significantly higher scores on both the BPPV and safety sub-scores. The difference in scores was principally due to a higher proportion of detailed nystagmus assessments prior to any positional testing, much higher intent to perform the DHT (63% vs 29% for the BPPV case), more accurate BPPV diagnosis, more frequent appropriate use of the CRM (100% vs 17% for the BPPV case once the vignette described characteristic BPPV nystagmus), and safer care in identifying and managing the stroke-dizziness case. (Table 4, eTable 1). Both the control and intervention groups had low rates of describing the characteristic triggered and transient BPPV nystagmus (0%−8%, eTable 1). The proportion of participants who sent the stroke case home was not higher in the intervention group (29%) versus the control group (58%); each of the other individual safety items is shown in eTable 2.

Table 4:

Main results

| Intervention mean (SD) (n=24) | Control mean (SD) (n=24) | Mean Difference | 95% confidence interval of difference | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BPPV Subscore (maximum =100) | 41.2 (17.0) | 23.2 (11.6) | 18 | 11 –25.1 | 0.0001 |

| Safety Subscore (maximum = 100) | 72.0 (26.4) | 45.5 (32.8) | 26.5 | 9.2 – 43.8 | 0.002 |

| Combined Score (maximum = 200) | 113.2 (29.1) | 68.6 (36.4) | 44.6 | 25.5 – 63.8 | <0.00001 |

Vignette scores comparing group randomized to benign paroxysmal peripheral vertigo (BPPV) intervention to group randomized to control. (Higher scores equal better performance).

Sensitivity Analysis of Primary Endpoint

We included the continuous variable for years since completion of residency into the linear regression model, and the parameter estimate for change in the primary outcome in the treatment versus the control group did not change. We additionally added an interaction term (years since residency times treatment group) into the model which was not significant.

Secondary Analyses

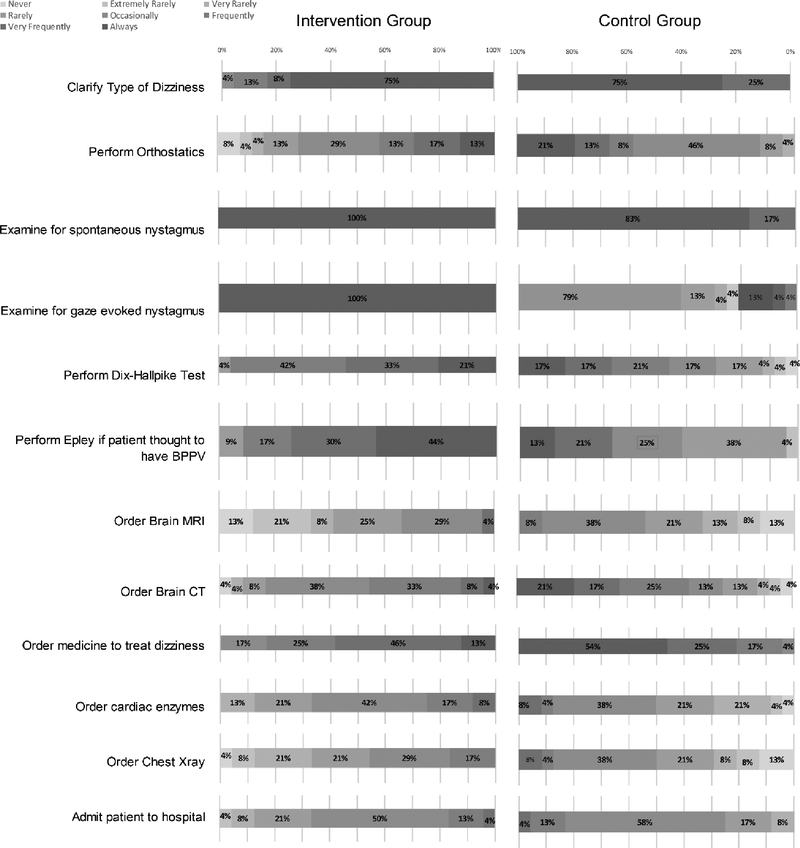

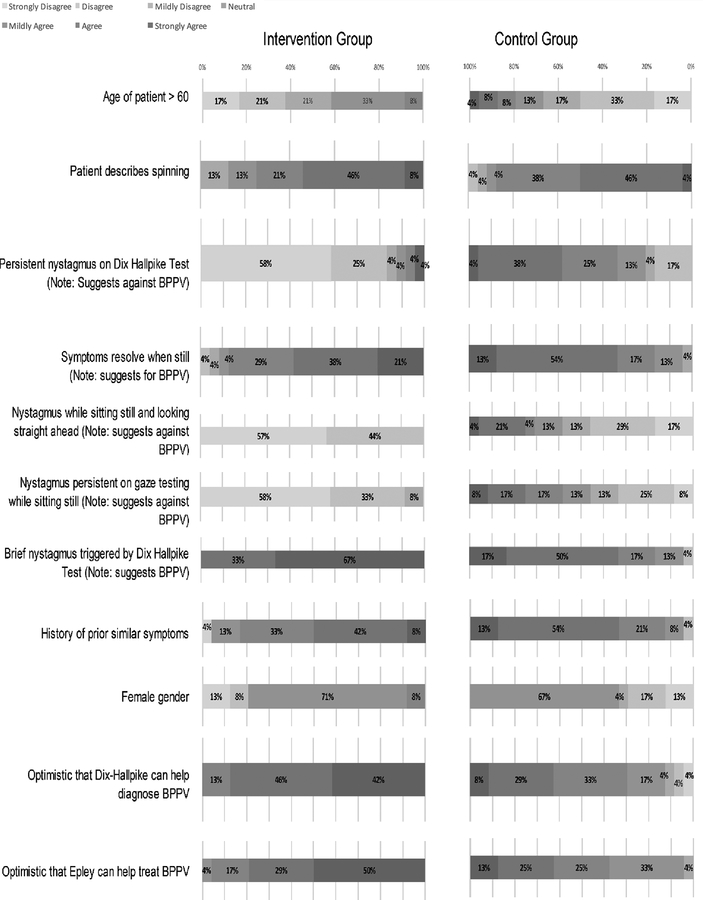

On the post-vignette survey, high proportions of both groups reported examining patients for spontaneous and gaze evoked nystagmus (Figure 1 / eTable 3). All but one of the 24 (96%) intervention group subjects reported that they would frequently, very frequently or always use the Dix-Hallpike test when they suspected BPPV in the future, versus 13 out of the 24 (54%) in the control group. Similarly, intervention group participants more frequently endorsed an intent to use the Epley maneuver in the future, for suspected BPPV, compared with the control group (22/24 versus 8/24). Regarding perceived clinician importance of dizziness risk factors (Figure 2 /eTable 4), all members of the intervention group correctly disagreed with BPPV being associated with the presence of gaze nystagmus while sitting still; less than half (11) of the control group disagreed with this association. More intervention group participants strongly agreed with the characteristic pattern of BPPV nystagmus (66.7% vs 16.7%). The intervention group expressed more optimism (eTable 6) regarding the helpfulness of the Dix-Hallpike test (24/24) than did the control group (17/24).

Figure 1:

Participant reported future approach to patients with dizziness. Participants were asked to indicate how frequently they anticipate doing each specified activity in future dizziness visits when there is not a clear cause after the history and general examination.

Figure 2:

Participant level of agreement with factors important to “ruling-in” a diagnosis of Benign Paroxysmal Positional Vertigo, and optimism regarding postional testing and treatment

Discussion

In this vignette-based randomized controlled trial, emergency physicians randomized to an educational intervention that promoted appropriate BPPV care had better planned performance scores compared with controls. We utilized a validated technique for assessing clinical practice actions in a given patient oriented scenario. These results indicate that the concepts, content, and delivery form of the intervention were compelling enough to influence the planned behavior of emergency physicians. This positive finding supports future studies to implement the tool into clinical practice and then assess its impact on actual evaluation and management measures.

The better performance in the intervention group was the result of several factors including higher frequency of DHT use, more accurate diagnosis, and more frequent and appropriate use of the CRM. The intervention group also had a higher proportion of detailed nystagmus assessments prior to positional testing, in addition to more frequent investigation into symptoms, more detailed neurological exam, more appropriate use of head imaging and hospital admission.

On the other hand, several activities did not differ as much as we intended. Namely, reporting that one would look for spontaneous nystagmus before performing the Dix-Hallpike was only reported by about one-third of the intervention group. In addition, only two participants (both in intervention group) reported they would look for triggered, transient, nystagmus to rule in BPPV. The implications of this are not clear. It is possible the intervention did not convey this information well enough. However, the intervention group did have much stronger appropriate agreement with the correction pattern of BPPV nystagmus when this was specifically queried in the post-vignette questionnaire.

To our knowledge, this is the first study to develop and assess a BPPV-focused intervention on ED providers or any other practitioners. The test and the treatment for BPPV are evidence-based and concordant with practice guideliness9, 10, 22, yet are vastly underused and misinterpreted by ED providers.12, 13, 16 We previously identified several barriers to the use of the DHT and CRM that the educational intervention was designed to address.13 Development of the intervention was guided by input from a multi-disciplinary panel and Theory of Planned Behavior.

The mechanism by which DHT and CRM improve BPPV specific performance is straightforward because these are the clearly specified steps to identify and treat it. On the other hand, the mechanism by which these could improve safe care and identify serious causes of dizziness may be less intuitive. We believe this is because of the many misconceptions about BPPV, which results in underuse, misuse, and misinterpretation of the DHT.13 Increasing optimal use and interpretation of the DHT and CRM will result in improved classification of dizziness presentations with respect to BPPV-status. Improved classification of BPPV status would then lead to better performance in positive BPPV cases, and improved safety performance in negative BPPV cases, due to appropriately heighted consideration of other potentially serious causes.

The findings of this study may be generalizable to clinical practice, even though we focused on a vignette-based clinical scenario to further refine the intervention. Our overall goal is to use this intervention to change physician practice, by increasing appropriate use of the DHT and CRM. We focused the development process on emergency physicians; we believe these findings would also be applicable to mid-level providers such as physician assistants and nurse practitioners but confirmation would require further study. Secondary analyses revealed that behavioral intention differed between the groups: emergency physicians receiving the educational intervention indicated more optimism and had high intention to use both the Dix-Hallpike test and CRMs in the future compared to physicians who did not receive the education.

This study has several limitations. We used a vignette-based method that was previously validated against standardized patients in various clinical conditions.18 However, these dizziness vignettes have not been validated against actual clinical practice nor specifically for acute vertigo. Future work will focus on changing actual medical care in the emergency department. We focused only on board certified or eligible emergency physicians from the United States; practice patterns and risk tolerance are likely to vary across other countries. There was an unintended imbalance between intervention and control groups: the majority of the control group were more recent graduates of emergency residencies compared to individuals in the intervention group. However, sensitivity analyses did not reveal any difference in the primary outcome after adjusting for years since graduation. In addition, it is not clear that individuals reporting more time since graduation versus less would be more responsive to the educational intervention. We assessed practice intentions immediately after participants completed the intervention, and thus reliability of the information and performance scores over a longer time period are not known. Future work will need to examine how lasting improvements are and how well they are adopted into actual practice. In addition, we recruited from the vendor exhibitor hall at a national emergency medicine meeting. It is likely that visitors to such exhibit halls are not necessarily representative of all practicing emergency physicians. The scoring system we used was developed iteratively by expert panel prior to data analysis. It is possible that different weightings would change the results. When assessing the responses to the individual items, and the large difference across groups on many of them, it appears unlikely that the overall conclusions would be meaningfully changed by altering the weights given to each item. Finally, we did not assess hands-on training methods during this investigation and given the physical nature of the maneuvers some form of physical training is likely needed in future educational interventions focused on BPPV.

We showed that providing practicing physicians a short educational intervention increased performance on ED dizziness vignettes and their willingness to use the Dix-Hallpike test and CRM. Future work is needed to implement and evaluate this intervention into clinical practice.

Supplementary Material

Key points.

Question:

Can a targeted educational intervention safely increase emergency physician use of positional testing and canalith repositioning maneuvers for benign paroxysmal positional vertigo in vignette-based clinical scenarios?

Findings:

The intervention safely and significantly increased the appropriate use of positional testing and increased the number of physicians who planned to use those maneuvers in the future.

Meaning:

The vignette based study demonstrated the educational intervention could increase intention to use positional testing in the emergency department. An adapted version of this intervention will be tested to determine whether it can change clinical practice.

Acknowledgments

Financial Support

This study was funded by the National Institutes of Health - the National Institute of Deafness and other Communication Disorders (R01 DC012760).

Footnotes

Data Access and Responsibility

Drs. Kerber and Meurer have access to the data and both take complete responsibility for the accuracy of the analyses and reports in this manuscript. We placed the analytic dataset from this study in the University of Michigan Deep Blue institutional archive at the following persistent link: https://doi.org/10.7302/Z2222RQC.

Potential Conflicts of Interest

No authors have any conflicts of interest to report.

References

- 1.Kerber KA, Meurer WJ, West BT and Mark Fendrick A, Dizziness presentations in US emergency departments, 1995–2004, Academic Emergency Medicine, 2008, 15(8):744–750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nedzelski J, Barber H and McIlmoyl L, Diagnoses in a dizziness unit, The Journal of otolaryngology, 1986, 15(2):101–104. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kerber KA, Brown DL, Lisabeth LD, Smith MA and Morgenstern LB, Stroke among patients with dizziness, vertigo, and imbalance in the emergency department, Stroke, 2006, 37(10):2484–2487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kerber KA, Meurer WJ, Brown DL, Burke JF, Hofer TP, Tsodikov A, Hoeffner EG, et al. , Stroke risk stratification in acute dizziness presentations: A prospective imaging-based study, Neurology, 2015, 85(21):1869–1878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kim J-S and Zee DS, Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo, New England Journal of Medicine, 2014, 370(12):1138–1147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.von Brevern M, Radtke A, Lezius F, Feldmann M, Ziese T, Lempert T and Neuhauser H, Epidemiology of benign paroxysmal positional vertigo: a population based study, Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry, 2007, 78(7):710–715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dix M and Hallpike C, The pathology, symptomatology and diagnosis of certain common disorders of the vestibular system: SAGE Publications, 1952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bhattacharyya N, Gubbels SP, Schwartz SR, Edlow JA, El-Kashlan H, Fife T, Holmberg JM, et al. , Clinical Practice Guideline: Benign Paroxysmal Positional Vertigo (Update), Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery, 2017, 156(3_suppl):S1–S47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brown MD, Is the Canalith Repositioning Maneuver Effective in the Acute Management of Benign Positional Vertigo?, Annals of Emergency Medicine, 2011, 58(3):286–287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hilton MP and Pinder DK, The Epley (canalith repositioning) manoeuvre for benign paroxysmal positional vertigo, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chang AK, Schoeman G and Hill M, A randomized clinical trial to assess the efficacy of the Epley maneuver in the treatment of acute benign positional vertigo, Academic Emergency Medicine, 2004, 11(9):918–924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kerber KA, Burke JF, Skolarus LE, Meurer WJ, Callaghan BC, Brown DL, Lisabeth LD, et al. , Use of BPPV processes in emergency department dizziness presentations: a population-based study, Otolaryngology--Head and Neck Surgery, 2013, 148(3):425–430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kerber KA, Forman J, Damschroder L, Telian SA, Fagerlin A, Johnson P, Brown DL, et al. , Barriers and facilitators to ED physician use of the test and treatment for BPPV, Neurology: Clinical Practice, 2017, 7(3):214–224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stanton VA, Hsieh Y-H, Camargo CA Jr, Edlow JA, Lovett P, Goldstein JN, Abbuhl S, et al. , Overreliance on Symptom Quality in Diagnosing Dizziness: Results of a Multicenter Survey of Emergency Physicians, Mayo Clinic Proceedings, 2007, 82(11):1319–1328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Newman-Toker DE, Stanton VA, Hsieh Y-H and Rothman RE, Frontline providers harbor misconceptions about the bedside evaluation of dizzy patients, Acta oto-laryngologica, 2008, 128(5):601–604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kerber KA, Morgenstern LB, Meurer WJ, McLaughlin T, Hall PA, Forman J, Mark Fendrick A, et al. , Nystagmus Assessments Documented by Emergency Physicians in Acute Dizziness Presentations: A Target for Decision Support?, Academic Emergency Medicine, 2011, 18(6):619–626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Peabody JW, Luck J, Glassman P, Dresselhaus TR and Lee M, Comparison of Vignettes, Standardized Patients, and Chart Abstraction, Jama, 2000, 283(13):1715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Peabody JW, Luck J, Glassman P, Jain S, Hansen J, Spell M and Lee M, Measuring the Quality of Physician Practice by Using Clinical Vignettes: A Prospective Validation Study, Annals of Internal Medicine, 2004, 141(10):771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ajzen I, The theory of planned behavior, Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 1991, 50(2):179–211. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hwang IK, Shih WJ and De Cani JS, Group sequential designs using a family of type I error probability spending functions, Statistics in medicine, 1990, 9(12):1439–1445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Anderson K, gsdesign: Group sequential design, R package version, 2014:29–3. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bhattacharyya N, Gubbels SP, Schwartz SR, Edlow JA, El-Kashlan H, Fife T, Holmberg JM, et al. , Clinical Practice Guideline: Benign Paroxysmal Positional Vertigo (Update), Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery, 2017, 156(3_suppl):S1–S47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.