Abstract

Materials synthesized by organisms, such as bones and wood, combine the ability to self-repair with remarkable mechanical properties. This multifunctionality arises from the presence of living cells within the material and hierarchical assembly of different components across nanometer to micron scales. While creating engineered analogs of these natural materials is of growing interest, our ability to hierarchically order materials using living cells largely relies on engineered 1D protein filaments. Here, we lay the foundations for bottom-up assembly of engineered living material composites in 2D along the cell body using a synthetic biology approach. We engineer the paracrystalline surface-layer (S-layer) of Caulobacter crescentus to display SpyTag peptides that form irreversible isopeptide bonds to SpyCatcher-modified proteins, nanocrystals, and biopolymers on the extracellular surface. Using flow cytometry and confocal microscopy, we show that attachment of these materials to the cell surface is uniform, specific, and covalent, and its density can be controlled based on the location of the insertion within the S-layer protein, RsaA. Moreover, we leverage the irreversible nature of this attachment to demonstrate via SDS-PAGE that the engineered S-layer can display a high density of materials, reaching 1 attachment site per 288 nm2. Finally, we show that ligation of quantum dots to the cell surface does not impair cell viability and this composite material remains intact over a period of two weeks. Taken together, this work provides a platform for self-organization of soft and hard nanomaterials on a cell surface with precise control over 2D density, composition, and stability of the resulting composite, and is a key step towards building hierarchically ordered engineered living materials with emergent properties.

Living organisms hierarchically order soft and hard components to create biominerals that have multiple exceptional physical properties1. For example, the hierarchical structure of nacre creates its unusual combination of stiffness, toughness, and iridescence. Genetically manipulating living cells to arrange synthesized materials into engineered living materials (ELMs)2,3 opens a variety of applications in bioelectronics4, biosensing5, smart materials6, and catalysis3–7. Many of ]these approaches use surface display of 1D protein filaments8–11 or membrane proteins12,13 to arrange materials, while cell display methods that hierarchically order materials in 2D with controlled spatial positioning and density have yet to be fully developed. This gap limits the structural versatility and degree of control available to rationally engineer ELMs.

Surface-layer (S-layer) proteins offer an attractive platform to scaffold materials in 2D on living cells due to their dense, periodic structures, which form lattices on the outermost surface of many prokaryotes14 and some eukaryotes15. These monomolecular arrays can have hexagonal (p3, p6)16–17, oblique (p1, p2)18–19, or tetragonal (p4)20 geometries and play critica roles in cell structure21–22, virulence23, protection24, adhesion25, and more. Recombinant S-layer proteins can replace the wild-type lattice in native hosts, or can be isolated and recrystallized in vitro, on solid supports, or as vesicles26. These have been used for a number of applications26,27, including bioremediation28 and therapeutics29 on cells.

To date, only two S-layer proteins have solved atomic structures, allowing for sub- nanometer precise positioning of attached materials: SbsB of Geobacillus stearothermophilus PV7218 and RsaA of Caulobacter crescentus CB1530. Of these two S-layer proteins, there is a well-established toolkit for the genetic modification of C. crescentus, as it has been studied extensively for its dimorphic cell cycle31. Additionally, C. crescentus is a Gram-negative, oligotrophic bacterium that thrives in low-nutrient conditions, and while a strict aerobe, can survive micro-aeration32. Together, this makes C. crescentus particularly suitable as an ELM chassis. RsaA forms a p6 hexameric lattice with a 22-nm unit cell (Figure 1a,b) at an estimated density of 45,000 monomers per bacterium33 and is amenable to peptide insertions34. Specific protein domains have been inserted in RsaA to bind lanthanide metal ions35 or viruses29. However, engineered RsaA variants currently lack the ability to assemble a variety of materials, in an irreversible fashion, and with well-characterized density - all key features needed for ELMs.

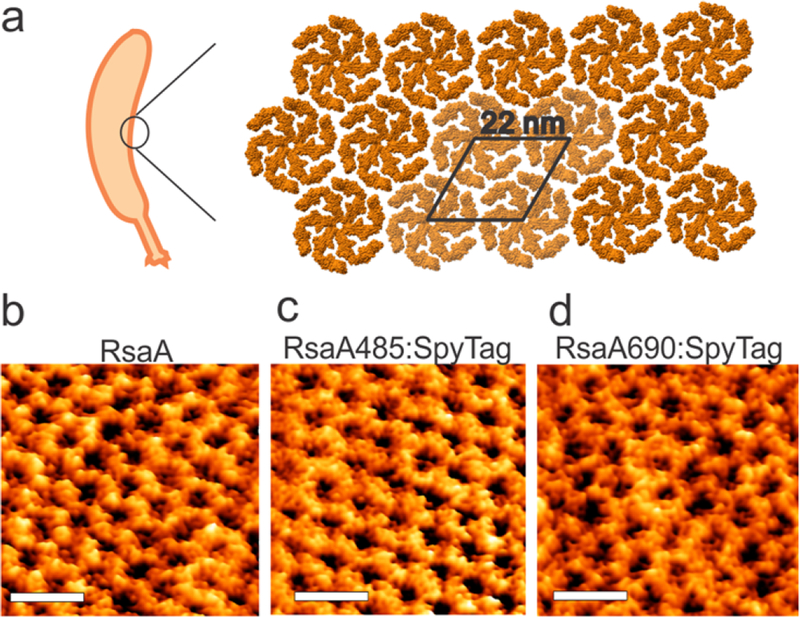

Figure 1.

RsaA forms a 2D hexameric lattice on the surface of C. crescentus. (a) Structure of the RsaA lattice.30 (b) High resolution AFM images of the wild-type RsaA lattice (strain MFm111), (c) RsaA485:SpyTag (strain MFm 118), (d) RsaA690:SpyTag (strain MFm 120) on the surface of C. crescentus cells. In all three cases, a well-ordered, hexagonal protein lattice is observed. The unit cell length (center-to-center distance between adjacent hexagons) is 22 ± 1 nm, which is the same as reported in literature. Scale bar is 40 nm. See Methods for experimental details of AFM.

Here we engineer RsaA as a modular docking point to ligate inorganic, polymeric, or biological materials to the cell surface of C. crescentus without disrupting cell viability. This 2D assembly system is specific, stable, and allows for control over the density of attached materials without the use of chemical cues, achieving a maximal coverage of ~25% of all possible sites, the highest density of cell-surface displayed proteins reported to our knowledge. This work forms the foundation for a new generation of hierarchically assembled ELMs.

Results and Discussion

Design and Construction of Caulobacter crescentus S-layer variants for surface display

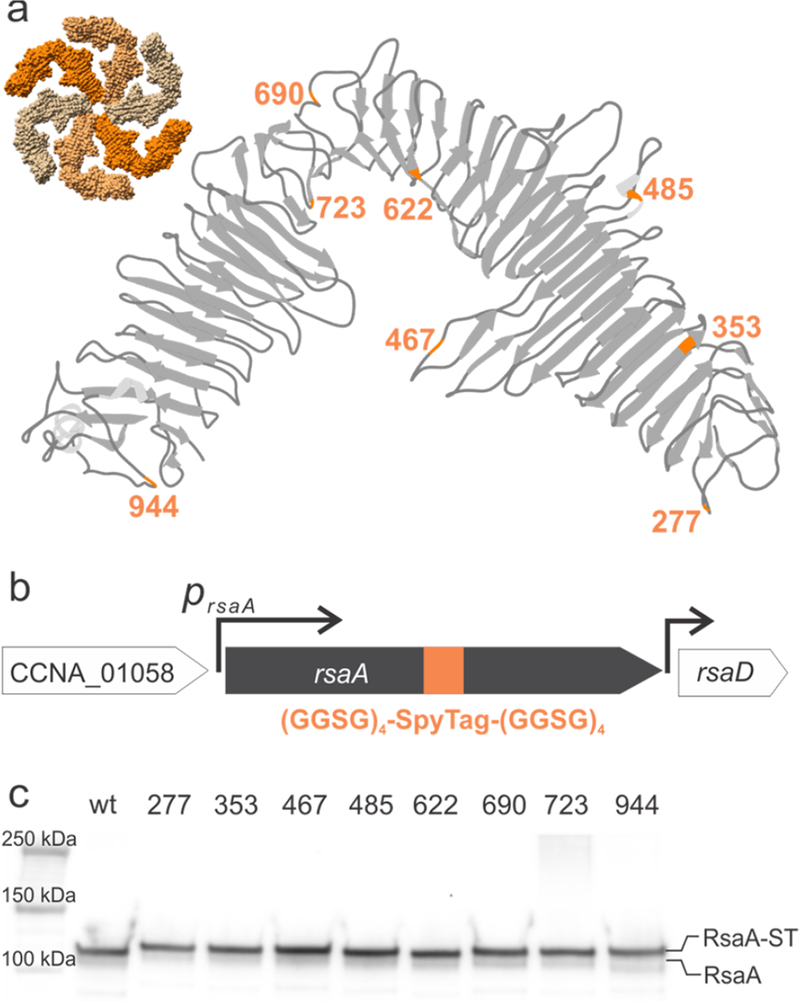

To display materials on the surface of C. crescentus cells, we designed a genetic module that meets four criteria: (i) a solution-exposed peptide that drives (ii) specific, stable, a stoichiometric attachment (iii) with tunable occupancy and (iv) that does not disrupt RsaA coverage. We hypothesized that varying the location of the binding peptide within RsaA might affect its solution accessibility leading to strains that have a range of occupancy. Therefore, we selected a panel of locations arrayed across the entire RsaA monomer (Figure 2a) to insert the peptide. Smit and colleagues previously identified two sites, at amino acid positions 723 and 944, that allowed for surface display of peptides34, so we started with these positions. We then selected six additional sites that are known to be susceptible to proteolytic cleavage presumably by the previously characterized S-layer Associated Protease (sapA)36. We hypothesized these additional sites, immediately following amino acid positions 277, 353, 467, 485, 622, and 690, might be accessible in a ΔsapA strain which we created (abbreviated as CB15NΔsapA). All subsequent engineering to the eight positions within rsaA was done in this background.

Figure 2.

Design and expression of RsaA-SpyTag in C. crescentus. (a) Ribbon diagram of the RsaA monomer structure30 indicating SpyTag insertion sites (orange). Inset shows a space-filling model of the RsaA hexamer. (b) Design of engineered C. crescentus strains expressing RsaA-SpyTag. SpyTag flanked by upstream and downstream (GGSG)4 spacers was directly inserted into the genomic copy of rsaA. (c) Immunoblot with anti-RsaA antibodies of C. crescentus strains whole cell lysate. The band corresponding to RsaA increases in molecular weight from wild-type RsaA (lane 2) to RsaA-SpyTag at each insertion site (lanes 3–10).

To achieve specific, stoichiometric, and irreversible conjugation to RsaA, we employed the split-protein system SpyTag-SpyCatcher37,38, which forms an isopeptide bond between the SpyCatcher protein and SpyTag peptide. The RsaA S-layer can accommodate insertion of large peptide sequences29,35, which suggested that the 45-mer SpyTag peptide sequence, flanked on each side by a (GSSG)4 flexible linker for accessibility, may be integrated and displayed without disrupting S-layer assembly. This modified lattice should then allow the formation of a covalent isopeptide bond between any material displaying the SpyCatcher partner protein and the SpyTag on the cell surface.

Since expression of RsaA from a p4-based plasmid in an ΔrsaA background formed a lattice structure indistinguishable from genomically-expressed RsaA (Figure 1b, we initially constructed p4-based plasmids39 that constitutively express RsaA-SpyTag fusions (Table S2) and transformed them into C. crescentus JS403839. Examination of the cell surface of two of these plasmid-bearing strains by AFM confirmed that RsaA-SpyTag was expressed and showed that the RsaA-SpyTag formed a S-layer lattice with the same nanoscale ordering as wild-type RsaA (Figure 1b–d). However, we observed significant growth defects, morphological changes, and unstable RsaA expression in all of the plasmid-bearing strains (Figure S1). For this reason, we integrated SpyTag and its linkers directly into the genomic copy of rsaA (Figure 2b) in the CB15NΔsapA background (Table S1). We notate these strains based on the SpyTag insertion site, e.g. rsaA690:SpyTag denotes insertion of the SpyTag and (GSSG)4 linkers immediately after amino acid 690. No growth defects or morphological changes are apparent in any of the engineered strains, implying that our genomic insertions do not affect cell viability, and therefore these strains were used for the rest of the study. These observations suggest the more regulated genomic expression of recombinant rsaA, a highly-transcribed gene, sidesteps growth impairments. SDS-PAGE analysis of RsaA-SpyTag expression of wild-type (CB15NΔsapA) and engineered cells (rsaA:SpyTag variants) shows the expected band for wild-type RsaA at 110 kDa (Figure 2c), in line with the observed migration of RsaA on SDS-PAGE40,30. Moreover, all eight engineered proteins have comparable expression levels to wild-type RsaA and show the small increase in molecular weight associated with SpyTag and its linkers (Figure 2c). These observations demonstrate that successful expression of SpyTag within RsaA at a range of different positions does not adversely affect RsaA expression levels.

Engineered S-layers specifically display proteins ligated to the cell surface

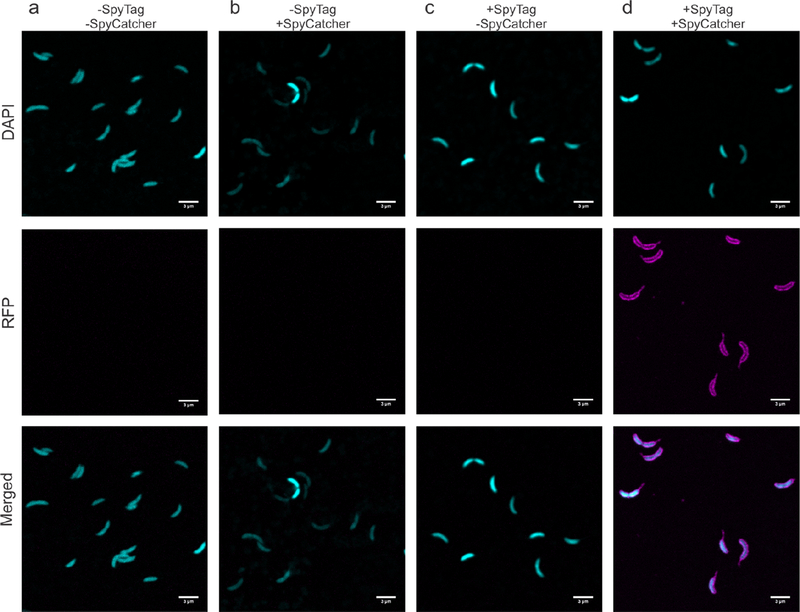

To explore accessibility of the SpyTag peptide on the C. crescentus cell surface, we engineered and purified a fusion of SpyCatcher and mRFP141,42,43. We incubated the wild-type and engineered rsaA690:SpyTag strains with the fluorescent SpyCatcher-mRFP1 protein or mRFP1 alone, washed away unbound protein, and visualized mRFP1 attachment to individual cells via confocal microscopy (Figure 3). No significant mRFP1 fluorescence is apparent in controls that used C. crescentus expressing wild-type RsaA or mRFP1 without SpyCatcher (Figure 3 a–c), indicating no significant non-specific binding of mRFP1 to the cell surface. When SpyTag is displayed on RsaA and SpyCatcher-mRFP1 is present, bright and uniform fluorescence is observed along the morphologically-normal, curved cell surface, including the stalk which is covered by the S-layer lattice17,30,33 (Figure 3d). These observations indicate engineering SpyTag into RsaA enables specific binding of a SpyCatcher fusion protein to the extracellular surface, and furthermore illustrates that engineering SpyTag into the S-layer does not substantially affect the morphology of C. crescentus.

Figure 3.

SpyCatcher protein fusions ligate specifically to the surface of C. crescentus expressing RsaA-SpyTag. (a−d) Confocal fluorescence images of C. crescentus cells visualized in DAPI and RFP channels. Cells expressing wild-type RsaA incubated with (a) mRFP1 or (b) SpyCatcher-mRFP1. Cells expressing RsaA690-SpyTag with (c) mRFP1 or (d) SpyCatcher-mRFP1. Only when the SpyCatcher-mRFP1 probe is introduced to cells displaying SpyTag (d) is RFP fluorescence tightly associated with the cell membrane observed, including the stalk region. Scale bar = 3 μm.

Density of attached materials is controlled by insertion location

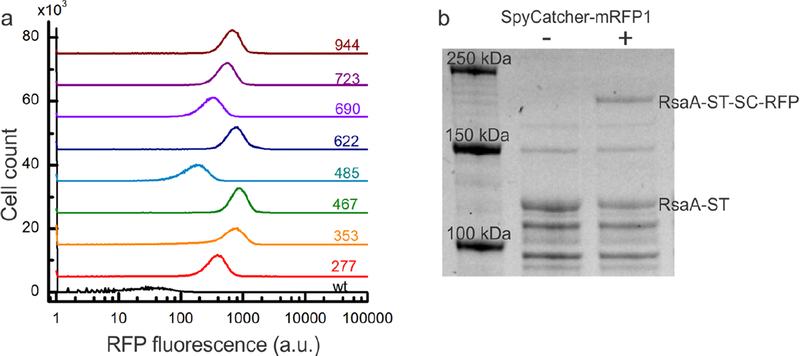

Having demonstrated specific display of proteins on the surface, we turned to the hypothesis that the solution-accessibility of the eight insertion locations within the RsaA monomer would allow us to vary the density of attached materials. To quantify this relative accessibility, we again incubated the engineered strains with SpyCatcher-mRFP1, washed away unbound protein, and measured the fluorescence intensity per cell with flow cytometry. The engineered strains show a >100-fold increase in fluorescent signal (Figure 4a) over the wild-type control, indicating that all eight positions can ligate significant amounts of SpyCatcher fusion protein. Among the eight engineered strains, there is a ~5-fold variation in the levels of ligation (Table 1), with rsaA467:SpyTag and rsaA485:SpyTag showing the highest and lowest densities of binding, respectively. These results unveil six new permissive insertion sites within RsaA and show that the amount of protein bound to the cell surface can be controlled by utilizing these different insertion points. To test that the fusion protein is irreversibly conjugated to RsaA-SpyTag, we incubated strain rsaA467:SpyTag, which showed the highest fluorescence by flow cytometry, with SpyCatcher-mRFP1, boiled the sample for 10 minutes with SDS and 2-mercaptoethanol, and visualized covalent attachment by SDS-PAGE (Figure 4b). The band corresponding to RsaA- SpyTag (Figure 4b) decreases in intensity while the band corresponding to the RsaA-SpyTag- SpyCatcher-mRFP1 assembly appears in as little as 1 hour and increases over 24 hours. Subsequent immunoblotting of this reaction with anti-RsaA polyclonal antibodies confirms that the assembly band contains RsaA (Figure S2). These observations indicate the binding is covalent. We leveraged the formation of this covalent bond to quantify the absolute density of SpyCatcher-mRFP1 displayed on the C. crescentus cell surface. The density of the RsaA band decreases by 23 ± 5% (n = 6, refer to Methods for the details of this calculation), indicating that nearly a quarter of the rsaA467:SpyTag protein is ligated to SpyCatcher-mRFP1 after 24 hours. Based on the estimate of 45,000 RsaA monomers per cell, this translates to >11,000 copies of SpyCatcher-RFP displayed on the cell surface, an average density of 1.5 SpyCatcher-RFPs per RsaA hexamer, or 1 SpyCatcher-RFP per 288 nm2. Combining this information with the flow cytometry data, we calculated the percentage of the RsaA lattice that is covalently modified can be controlled over a range from 4–23% by varying the engineered location (Table 1, refer to Methods for the details of this calculation). These results provide quantitative information on how to utilize position-dependent insertion of SpyTag in RsaA to tune the density of attached materials and thus substantially improve our ability to rational engineer ELMs. To explore the diversity of structures that can be created at the cell surface using SpyCatcher-SpyTag ligation, we tested the capacity of engineered bacteria to conjugate CdSe/ZnS semiconductor quantum dots (QDs)46,47. SpyCatcher-functionalized QDs were generated through attachment of a heterobifunctional PEG linker molecule to an amphiphilic polymer encapsulating the QD surface. Subsequent incubation with SpyCatcher-Ser35Cys single cysteine mutant protein yielded QDs with surface-displayed SpyCatcher protein. We incubated PEGylated QDs and SpyCatcher-conjugated QDs (see Supporting Information) with wild-type and rsaA690:SpyTag strains, performed a wash, and visualized individual cells via confocal microscopy. There is significant QD fluorescence along the cell body in samples containing SpyCatcher-QDs and the engineered strain, while there is no significant fluorescence with the wild-type strain (Figure 6) or the PEGylated QDs. This demonstrates that hard nanomaterials can also be specifically attached to the engineered RsaA lattice.

Figure 4.

SpyCatcher protein fusions covalently bind to RsaA-SpyTag with variable occupancy according to the SpyTag location. (a) Flow cytometry histograms of RFP fluorescence per cell for strains expressing wild-type RsaA (black) and RsaA-SpyTag (colored lines) incubated with SpyCatcher-mRFP1 for 1 h. Baselines are offset for clarity. All eight strains displaying RsaA-SpyTag show an increase in the intensity of RFP fluorescence over the negative control with their intensity varying based on where SpyTag is inserted within RsaA. (b) SDS-PAGE of whole cell lysates from the rsaA467:SpyTag strain incubated for 24 h without (lane 2) and with (lane 3) SpyCatcher-mRFP1 protein. Appearance of a higher molecular weight band only in the reaction containing SpyCatcher-mRFP1 indicates covalent binding to RsaA-SpyTag.

Table 1.

Normalized and Absolute Levels of SpyCatcher-mRFP1 Ligation

| location of SpyTag insertion | absolute intensity of bound SpyCatcher-mRFP1, Iloc (mean ± SEM) |

relative SpyCatcher-mRFP1 binding, Iloc, rel (mean ± SEM) |

percentage of RsaA-SpyTag covalently modified (%), Ploc (percentage, SEM) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 277 | 373.9 ± 3.6 × 10−01 | 0.43 ± 5.5 × 10−04 | 9.9 ± 2.4 |

| 353 | 606.8 ± 8.5 × 10−01 | 0.70 ± 1.1 × 10−03 | 16.0 ± 4.9 |

| 467 | 871.6 ± 7.3 × 10−01 | 1.00 ± 1.2 × 10−03 | 23.0 ± 2.0 |

| 485 | 170.3 ± 2.3 × 10−01 | 0.20 ± 3.2 × 10−04 | 4.5 ± 1.3 |

| 622 | 778.1 ± 8.6 × 10−01 | 0.89 ± 1.2 × 10−03 | 20.5 ± 5.4 |

| 690 | 316.3 ± 3.3 × 10−01 | 0.36 ± 4.9 × 10−04 | 8.3 ± 2.1 |

| 723 | 536.0 ± 4.8 × 10−01 | 0.61 ± 7.5 × 10−04 | 14.1 ± 3.3 |

| 944 | 668.9 ± 6.1 × 10−01 | 0.77 ± 9.6 × 10−04 | 17.6 ± 4.2 |

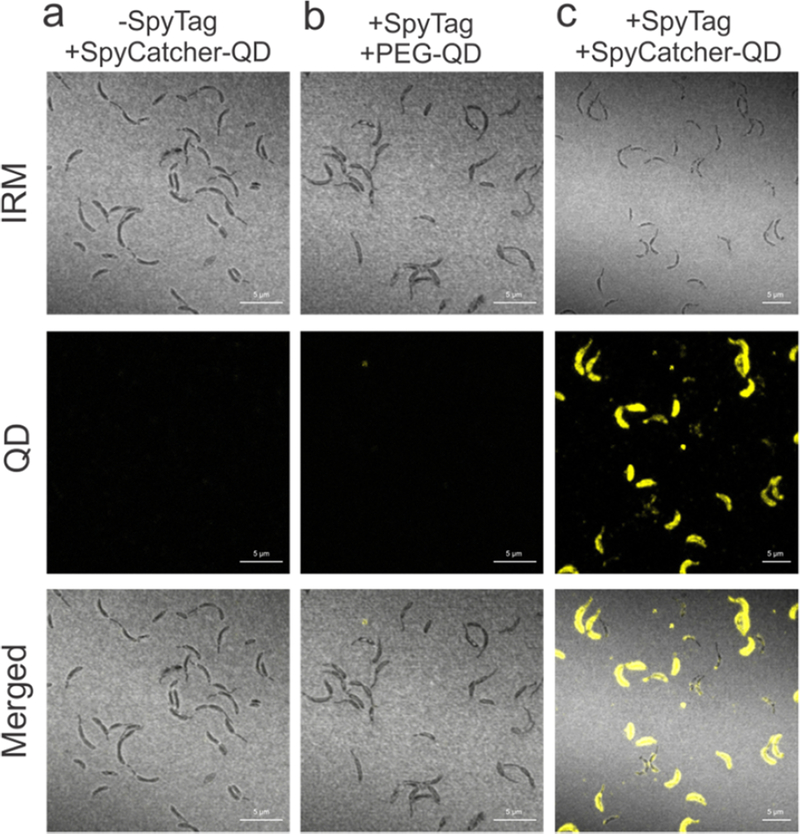

Figure 6.

Engineered RsaA assembles inorganic nanocrystals on the C. crescentus cell surface. (a–c) Interference reflection microscopy (IRM) and confocal fluorescence images of C. crescentus cells incubated with QDs. Cells expressing (a) wild-type RsaA incubated with SpyCatcher-QDs and (b) expressing RsaA690:SpyTag incubated with PEG-QDs. (c) Cells expressing RsaA690:SpyTag incubated with SpyCatcher-QDs show QD fluorescence along the cell surface, indicating specific assembly of SpyCatcher-QDs by the engineered strain. Scale bar = 5 μm.

Nanoparticle attachment does not affect cell viability

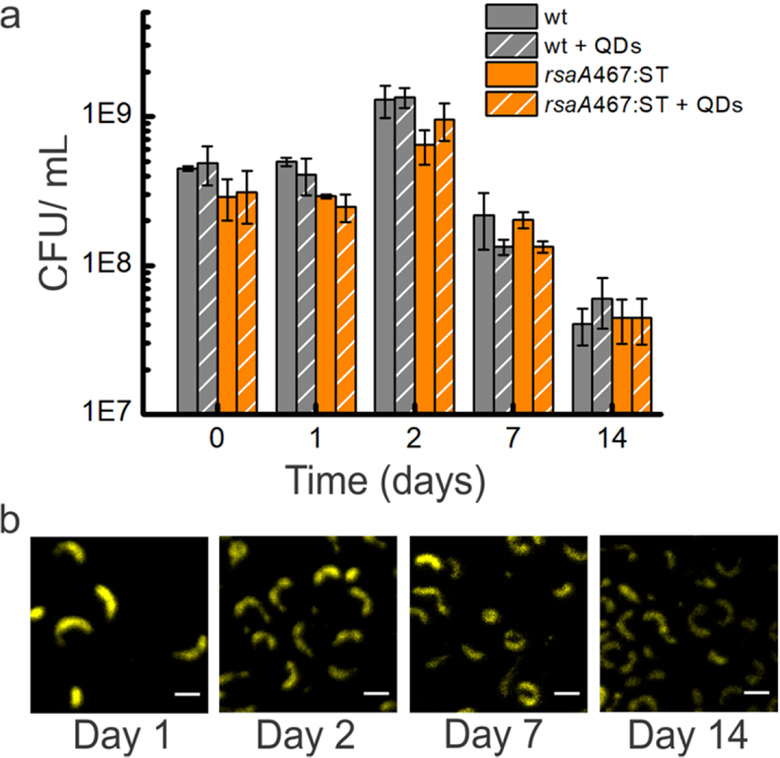

Finally, we explored the effect of coating the surface of the C. crescentus cells with nanoparticles on their viability, as this is key to creating hybrid living materials that remain metabolically active over time48. We incubated control wild-type (CB15NΔsapA) and engineered rsaA467:SpyTag cells with or without SpyCatcher-QDs for two weeks, sampled the cultures periodically, and enumerated the living cells (CFU/mL). We also imaged the samples using confocal microscopy to determine whether the SpyCatcher-QDs remained stably bound to the engineered S-layer. Under all conditions, the total cell numbers decrease over the two week duration, which is expected since nutrients are not replenished (Figure 7a). More importantly, the number of viable cells in the wild-type culture without QDs is not significantly different from the wild-type with unbound SpyCatcher-QDs, the rsaA467:SpyTag culture without QDs, or the rsaA467:SpyTag culture with QDs (Figure 7a). These results indicate that neither unbound SpyCatcher-QDs in the wild-type culture nor surface-bound SpyCatcher-QDs on the engineered cells affect viability, and there is no notable difference in viability between the wild-type and engineered cells. One possible interpretation of this cell viability is that the S-layer acts as an effective barrier, preventing disruption of the outer cell membrane, fulfilling one of its key evolutionary roles49–51. Imaging reveals that SpyCatcher-QDs remain attached to the cell surface over two weeks (Figure 7B) and non-specific binding of SpyCatcher-QDs on the surface of wild-type cells is not observed (Figure S5), once again highlighting the specificity and stabilityof the SpyTag-SpyCatcher system on S-layers. We do note that QD fluorescence is attenuated over time. This change could be due to a variety of factors including cleavage of any of the bonds between RsaA and the core QD or turnover of the RsaA protein, but is most likely loss of intrinsic QD fluorescence, which gradually decreases when SpyCatcher-QDs are incubated in M2G buffer over two weeks (Figure S6). Nonetheless, these results demonstrate that engineered RsaA can be used to generate stable living materials that require cells to remain viable for extended periods of time.

Figure 7.

Engineered C. crescentus with ligated SpyCatcher-QDs remain viable over 2 weeks. (a) Viability of CB15NΔsapA (wild-type) and CB15NΔsapA rsaA467:SpyTag strains incubated without or with SpyCatcher-QDs (+ QD) was assessed by quantifying colony forming units/mL (CFU/mL) as described in the Methods section. Data shown represent mean ± standard deviation of three replicates per condition. The CFU/mL of cells with SpyCatcher-QDs is very similar to that of cells grown without SpyCatcher-QDs. (b) Confocal images of rsaA467:Spytag + SpyCatcherQD show QD fluorescence over the two week duration indicating sustained attachment of SpyCatcher- QDs to the engineered strain. Scale bar = 3 μm.

Advancement of RsaA S-layer as a platform for controlled material assembly

In summary, we show that the S-layer of C. crescentus, RsaA, is a versatile platform for cell surface attachment of proteins, biopolymers, and inorganic materials when combined with the Spy conjugation system. We demonstrate that eight sites are available for peptide insertion within RsaA and that the insertion location tunes the attachment density. Ligation to the RsaA- SpyTag lattice is highly specific and covalent, with the absolute level of density of RsaA- displayed proteins reaching ~25% of the total RsaA, or 1 site per 288 nm2, which is the highest density of cell-surface displayed proteins reported to our knowledge. Moreover, we show that QD-C. crescentus composites assembled via RsaA-SpyTag form engineered living materials that persist for at least two weeks. In the following, we discuss possible reasons for the site- dependent variation in attachment density, specific applications for cell-display using the RsaA platform, and the broader opportunities it opens in the area of ELMs. We observed that the relative ligation efficiency varies ~5-fold across the eight permissive sites, with rsaA467:SpyTag affording the densest array of SpyCatcher-mRFP1. This variance is not due to protein expression levels, which do not vary significantly between strains (Figure 2c), and is unlikely to be caused by disruption to the S-layer lattice as our findin indicate that SpyTag insertions to not alter the structure on the nanometer scale (Figure 1b–d) but may be due to solvent-accessibility within the RsaA, steric clashes between sites on nearby RsaA monomers, or a combination of these factors. The most efficient binding site, RsaA467:SpyTag, is in an unstructured loop in a gap in the hexamer (Figure 2a), potentially giving more freedom for the SpyTag peptide to access a SpyCatcher-fusion. Since RsaA485:SpyTag and RsaA690:SpyTag are in an alpha-helix and a calcium-binding pocket, respectively (Figure 2a), these insertions could be causing local disruption in structure, leading to the lower occupancy we observe (Table 1). Additionally, position 277 is located near the pore of the hexamer, resulting in the five neighboring positions being between 1.4 and 2.8 nm away. Since the entire engineered linkage to mRFP1, i.e. (GSSG)4-SpyTag-SpyCatcher-mRFP1, is roughly 2.9 by 2.5 by 15 nm in dimensions, it is likely that some of the neighboring sites are sterically inaccessible once a single mRFP1 is bound. Further investigation will be required to untangle these possibilities.

Engineered C. crescentus opens new possibilities for hierarchical assembly of hybrid living materials

The engineered S-layer system described here offers immediate opportunities for engineering enzyme cascades on cells and encapsulation in hydrogels. By eliminating the need for direct fusion of enzymes to the S-layer, we avoid potential enzyme activity inhibition caused by expressing the protein in tandem with the S-layer monomer52. In addition, the varied ligation density and SpyTag spatial positioning engineered in our strains provides flexibility to attach enzymes in the most ideal pattern. As another potential application, bacterial cells are frequently encapsulated in hydrogels to enhance their stability as probiotics53, as adjuvants to plant growth in agriculture54, or as biostimulants in wastewater treatment55. Typically, no specific adherence mechanism is engineered between bacterial cells and the hydrogel, and many factors can affect gel stiffness56, including number or type of cells and media content. By using direct attachments between the S-layer and hydrogel polymers, we may achieve more stability and unique mechanical properties due to the sheer number of covalent crosslinks the between the engineered S-layer and the hydrogel matrix. Our work more broadly introduces several foundational aspects useful for engineering ELMs. First, our results (Figure 3, 5, 6) suggest any material on which SpyCatcher can be conjugated can be self-assembled on the modified 2D S-layer lattice, thus avoiding the labor-intensive reengineering of RsaA with peptides designed for specific targets. This makes our strain a versatile starting point for building an array of ELMs. Second, while ELMs with impressive functionality have been assembled via 1D curli fiber proteins and the type III secretion apparatus57, the 2D structure of the S-layer lattice yields another dimension of spatial control. Because hierarchical ordering underlies the exceptional physical properties of many natural biocomposites, the ability to regulate spacing of different components in multiple dimensions is key to rationally designing predictable ELMs. Third, we can attach materials densely to the cell surface; here we demonstrate ligation of ~11,000 copies of a protein to the C.crescentus cell surface, or 1 attached protein per 288 nm2. This is the highest density of surface arrayed proteins reported in a bacterium to our knowledge. Being able to access high densities is important because it ensures well-ordered structures while the ability to tune density may result in control over material properties. Lastly, the combined robustness of the covalent SpyCatcher-SpyTag system, the RsaA S-layer, and C. crescentus enables long-term persistence of the assembled structure and cell viability in an ELM even under low aeration and nutrient conditions. We envision this robustness will enable ELMs that can function in nutrient- poor environments with minimal intervention. Thus, the RsaA platform described here offers a modular, stable platform for assembling materials densely in 2D that opens new possibilities for constructing ELMs.

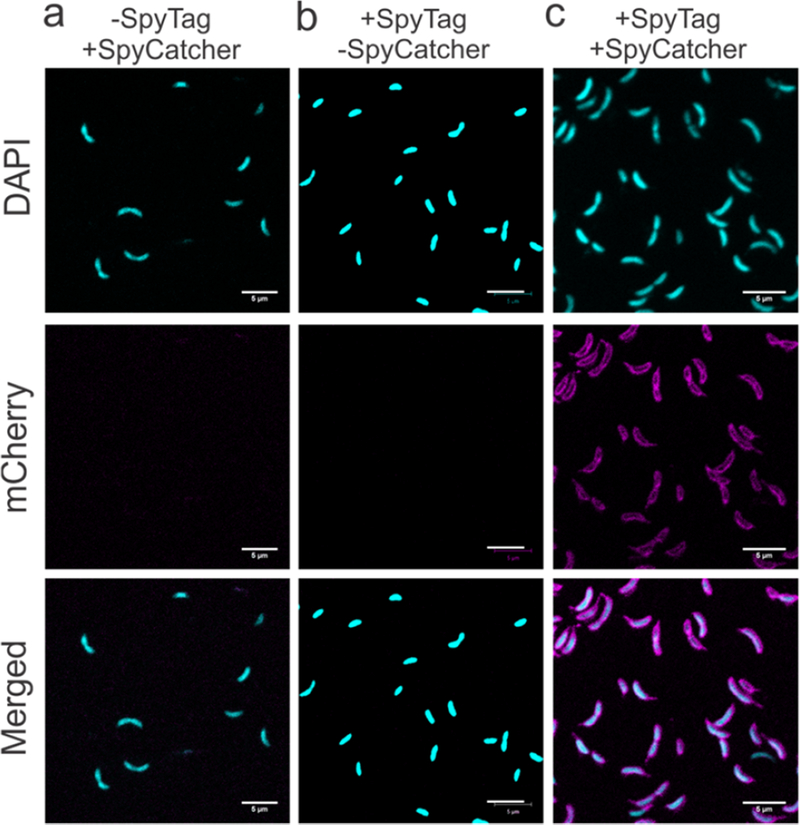

Figure 5.

Engineered RsaA assembles biopolymers on the C. crescentus cell surface. (a–c) Confocal fluorescence images of C. crescentus cells incubated with ELP-mCherry fusion proteins visualized in DAPI and mCherry channels. Cells expressing (a) wild-type RsaA incubated with SpyCatcher-ELP-mCherry and (b) expressing RsaA690:SpyTag incubated with ELP-mCherry. Only the rsaA690:SpyTag strain incubated with SpyCatcher-ELP-mCherry (c) shows signal along the cell membrane in the mCherry channel, indicating specific assembly on the cell surface. Scale bar = 5 μm.

Conclusions

In closing, hierarchically ordered hybrid materials could allow for the rational design of materials with the emergent properties seen in natural materials. A bottom-up approach towards these engineered living materials is controlled attachment of materials to the cell surface in 2D, which we achieved by engineering the C. crescentus S-layer with the Spy conjugation system for specific attachment of hard, soft, and biological materials at controllable densities. This modular base could lead to higher ordered materials that combine the functions of inorganic materials with the self-assembly and self-healing properties of living cells for applications that span medicine, infrastructure, and devices.

Methods

Strains:

All strains used in this study are listed in Table S1. C. crescentus strains were grown in PYE media at 30 °C with aeration. E. coli strains were grown in LB media at 37 °C with aeration. When required, antibiotics were included at the following concentrations: For E. coli, 50 μg/ml ampicillin, 20 μg/ml chloramphenicol, 30 μg/ml kanamycin. For C. crescentus, 10 μg/ml (liquid) or 50 mg/ml (plate) ampicillin, 2 μg/ml (liquid) or 1 μg/ml (plate) chloramphenicol, 5 μg/ml (liquid) or 25 μg/ml (plate) kanamycin. Diaminopimelic acid (DAP) was supplemented at 300 μM and sucrose at 3% w/v for conjugation and recombination methods respectively. All chemicals were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich or VWR.

Plasmid Construction:

A list of all strains, plasmids, and primers used in this study is available in Tables S1–3. Details on construction of p4B expression plasmids, pNPTS138 integration plasmids, and protein purification plasmids can be found in Supporting Information. Plasmids were introduced to E. coli using standard transformation techniques with chemically competent or electrocompetent cells, to C. crescentus using conjugation via E. coli strain WM3064.

Genome Engineering of C. crescentus:

The (GGSG)4-SpyTag-(GGSG)4 sequence was integrated into the genomic copy of rsaA using a 2-step recombination technique and sucrose\ counterselection. The pNPTS- rsaA(SpyTag) integration plasmids were conjugated into C. crescentus CB15NΔsap and plated on PYE with kanamycin to select for integration of the plasmid. Successful integrants were incubated in liquid media overnight and plated on PYE supplemented with 3% (w/v) sucrose to select for excision of the plasmid and sacB gene, leaving the SpyTag sequence behind. Colonies were then spotted on PYE with kanamycin plates to confirm loss of plasmid-borne kanamycin gene. Integration of the SpyTag sequence and removal of the sacB gene was confirmed by colony PCR with OneTaq Hot Start Quick-Load 2x Master Mix with GC buffer (New England BioLabs) using a Touchdown thermocycling protocol with an annealing temperature ranging from 72°−62°C, decreasing 1° per cycle. Successful RsaA-SpyTag protein expression was confirmed by band shift in whole cell lysate in Laemmli buffer and 0.05% 2-mercaptoethanol on a BioRad Criterion Stain-free 4–20% SDS-PAGE. The gel was UV-activated for 5 minutes before imaging on a ProteinSimple FluorChem E system. As RsaA was migrating higher than expected, western blot was performed for confirmation. A Bio-Rad Trans-Blot Turbo system with nitrocellulose membrane was used to transfer protein from the SDS-PAGE gel and the membrane incubated in ThermoFisher SuperBlock buffer for 1 hr. The protein of interest was first labeled during a 30 min incubation with Rabbit-C Terminal Anti-RsaA polyclonal antibody58 (Courtesy of the Smit lab. 1:5000 in TBST, Tris-Buffered Saline with 0.1–0.05% Tween-20), followed by another 30 min incubation with Goat-Anti Rabbit-HRP (Sigma-Aldrich. 1:5000 in TBST). BioRad Precision Plus Protein Standards (Bio-Rad) were labeled with Precision Protein StrepTactin-HRP conjugate antibodies (Bio-Rad. 1:5000 in TBST). HRP fluorescence was activated with Thermo-Fisher SuperSignal West Pico Chemiluminescent Substrate and imaged in chemiluminescent mode. TBST washes were performed between each incubation step. The relative molecular weight ofbands quantified against the BioRad Precision Plus Protein Standards using ProteinSimple’sAlphaView software.

Monitoring Ligation of SpyCatcher-fusions to C. crescentus:

For flow cytometry experiments, cells were grown at 25°C to mid-log phase and cells containing the pBXMCS-2-RFP plasmid were induced for 1–2 hours with 0.03% xylose to serve as a positive control. A population of ~108 cells (determined by optical density measurement where OD600 at 0.05 contains 108 cells) were harvested by centrifugation at 8,000 RCF for 5–10 minutes and resuspended in PBS+0.5mM CaCl2. Using the cell density as determined by OD600 and assuming assuming 4.5×104 RsaA monomers/cell, we added SpyCatcher-mRPF1 to a final molar ratio of 1:20 - RsaA protein to SpyCatcher-mRFP1 . The reaction was then incubated for 1 hour at room temperature with rotation. All samples were protected from light with aluminum foil during the procedure and washed twice with 1ml of PBS+0.5mM CaCl2 buffer prior to imaging to remove any unbound protein. Cells were diluted to 106 cells/ml and analyzed on a BD LSR Fortessa. Data on forward scatter (area and height), side scatter, and PE Texas Red (561mm laser, 600 LP 610/20 filter) was collected. A total of 150,000 events for each strain was measured over three experiments.

For each strain, the total population was gated using scatter measurements to remove events corresponding to aggregates and debris. All events from the resulting main population were used to create histograms of the fluorescence intensity of bound SpyCatcher-mRPF1 for each strain expressing RsaA (wild-type control) or RsaA-SpyTag (Figure 4A). These fluorescence intensity values were also used to calculate the absolute intensity of bound of SpyCatcher-mRFP1 for RsaA-SpyTag insertion location (Iloc) shown in Table 1. The relative SpyCatcher-mRFP1 binding (Iloc,rel) was calculated by normalizing (Iloc) by the absolute intensity at location 467:

| (1) |

For confocal microscopy, cells were grown to mid-log phase and ~108 cells (again determined by OD600 measurement) harvested by centrifugation at 8,000 RCF for 5–10 minutes. They were then resuspended in PBS+0.5mM CaCl2 and, as in the flow cytometry experiments, a 1:20 ratio of RsaA protein to fluorescent probe, i.e. mRFP1, SpyCatcher-mRFP1, SpyCatcher- ELP-mCherry, or ELP-mCherry was added. The reaction was then incubated for 1 hour at room temperature with rotation for the mRFP1 probes and 24 hours at 4 °C for the ELP-mCherry probes. 2×107 cells were incubated with 100nM QDs for 24 hours at 4 °C with rotation. All samples were protected from light with aluminum foil during the procedure and washed twice with 1ml of buffer prior to imaging to remove any unbound protein. After the wash, cells with fluorescent probes were stained with 1 μM DAPI ((4’,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole). All samples were spotted onto agarose pads (1.5% w/v agarose in distilled water) and mounted between glass slides and glass coverslips. Immersol 518F immersion oil with a refractive index of 1.518 was placed between the sample and the 100x oil immersion objective (Plan-Apochromat, 1.40 NA) prior to imaging. Fluorescence and IRM was collected using a Zeiss LSM 710 confocal microscope (Carl Zeiss Micro Imaging, Thornwood, NY) with the Zen Black software. A 561nm laser used for RFP/mCherry excitation and 405nm for DAPI. For IRM, a 514nm laser was reflected into the sample using a mBST80/R20 plate, then the reflected light collected and imaged onto the detector. Images were false colored and brightness/contrast adjusted using ImageJ59.

To quantify the binding of SpyCatcher-mRFP1 to RsaA-SpyTag, the same procedure was used as above except with a 1:2 ratio of RsaA to RFP was used and incubation for 24 hours at 4 °C with rotation. The reaction was visualized on a BioRad Criterion Stain-free 7.5% SDS-PAGE in Laemmli buffer with 0.05% 2-mercaptoethanol and the molecular weight of bands quantified against BioRad Precision Plus Protein Standards using Protein Simple’s AlphaView software. The measurements were made in triplicate on two separate occasions and all six results averaged for the final percentage reported. For each experiment, the density of bands was measured using ImageJ59. Background subtraction was applied to the entire image and the background-subtracted integrated density within an equal area was determined for each RsaA- SpyTag protein band. The integrated density of the bands from triplicate reactions lacking SpyCatcher were averaged to give Iunreact. To calculate the percentage of RsaA467:SpyTag ligated to SpyCatcher-mRFP1 for each experiment, we calculated the difference in density between each RsaA-SpyTag band from reactions with SpyCatcher-mRFP1 (Ireact,1, Ireact,2, Ireact,3) relative to the unreacted control (Iunreact) and normalized this value by the unreacted control (Iunreact):

| (2) |

The reported value (P467) is an average of the two experiments. We then used the absolute percentage of ligation at location 467 (P467) and the relative binding of SpyCatcher-mRFP1 at each location to calculate the percentage of ligation for all the insertion positions 475:

| (3) |

The values of Ploc are shown in Table 1.

Cell viability assay:

Cell viability in the presence of SpyCatcher-QDs was determined using the viable plate count method. Approximately 4×108 mid-log phase cells (day 0) (cell number determined by OD600 measurement) were first incubated with 100 nM SpyCatcher-QDs in M2G buffer (1X M2 salts without NH4Cl to prevent extensive cell growth, 1 mM MgSO4, 0.5 mM CaCl2, 2% glucose) for 24 hours at 4 °C with rotation to allow QD ligation to the cell surface. Post-binding (day 1), the cultures were transferred to a 25 °C humidified incubator and left stationary for two weeks. Cultures were sampled at different time points (days 2, 7, and 14), serially diluted, and titered on PYE agar plates (0.2% peptone, 0.1% yeast extract, 1 mM MgSO4, 0.5mM CaCl2, 1.5% agar), which were incubated at 30 °C for two days. Colonies on the plates were counted and cell viability was quantified by enumeration of Colony Forming Units/mL as follows:

At the culture was placed on it. An 18 × 18 mm coverslip was then placed on the pad, and the trapped cells were imaged and processed using as outlined above

In situ atomic force microscope (AFM) imaging:

Mid-log cultures of C. crescentus JS4038 carrying p4B-rsaA600, p4B-rsaA600690: (GGSG)4-spytag-(GGSG)4, or p4B-rsaA600690: (GGSG)4-spytag-(GGSG)4, were harvested at 8000 rpm for 5 minutes and the pellet resuspended in PBS + 5mM CaCl2 buffer. The JS4038 strain is defective in capsular polysaccharide synthesis. This is necessary for AFM imaging as the the capsular polysaccharide layer obscures the S-layer lattice. The cells were washed three times to remove any debris. 100 μL of the washed cell culture was applied to a poly-L-lysine coated glass coverslip (12 mm cover glasses, BioCoat from VWR) which was pre-mounted onto a metal punk. The sample was incubated at room temperature for 1 hr to allow sufficient cell attachment and then 1 mL of PBS + 5mM CaCl2 buffer was used to wash away unbound cells from the glass surface. 50 μL of PBS + 5mM CaCl2 buffer was added to the resulting glass surface, and the sample was transferred onto the sample stage for imaging. In situ AFM imaging was performed on a Bruker Multimode AFM using PeakForce Tapping mode in liquid. An Olympus Biolever-mini cantilever (BL-AC40TS) was used for high resolution imaging. The following set of parameters was normally employed to ensure the best image quality: 0.2 to 0.5 Hz scanning rate, 512 × 512 scanning lines, 15 nm peak force amplitude, and 50 to 100 pN peak force setpoint.

Further methods on plasmid construction, protein purification, and QD synthesis can be found in the Supporting Information.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgement:

We are indebted to Prof. John Smit and Dr. John Nomellini for helpful conversations and starting materials. We also thank Dr. Francesca Manea for her contributions to the S-layer research at the Molecular Foundry and Dr. Andrew Hagen for the gift of the pARH356 plasmid. This work was supported by the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (Engineered Living Materials Program, C.M.A-F.) and National Institutes of Health award R01NS096317 (B.E.C.) Work at the Molecular Foundry was supported by the Office of Science, Office of Basic Energy Sciences, of the U.S. Department of Energy under Contract No. DE-AC02-05CH11231.

REFERENCES

- (1).Mann S (2001) Biomineralization: Principles and Concepts in Bioinorganic Materials Chemistry, Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- (2).Chen AY, Zhong C, and Lu TK (2015) Engineering Living Functional Materials. ACS Synth. Biol 4 (1), 8–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Nguyen PQ, Courchesne N-MD, Duraj-Thatte A, Praveschotinunt P, and Joshi NS (2018) Engineered Living Materials: Prospects and Challenges for Using Biological Systems to Direct the Assembly of Smart Materials. Adv. Mater 30 (19), e1704847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Chen AY, Deng Z, Billings AN, Seker UOS, Lu MY, Citorik RJ, Zakeri B, and Lu TK (2014) Synthesis and Patterning of Tunable Multiscale Materials with Engineered Cells. Nat. Mater 13, 515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Zhou AY, Baruch M, Ajo-Franklin CM, and Maharbiz MM (2017) A Portable Bioelectronic Sensing System (BESSY) for Environmental Deployment Incorporating Differential Microbial Sensing in Miniaturized Reactors . PLoS One 12 (9), e0184994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Gerber LC, Koehler FM, Grass RN, and Stark WJ (2012) Incorporating Microorganisms into Polymer Layers Provides Bioinspired Functional Living Materials. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 109 (1), 90–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Lee SY, Choi JH, and Xu Z (2003) Microbial Cell-Surface Display. Trends Biotechnol. 21 (1), 45–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Nussbaumer MG, Nguyen PQ, Tay PKR, Naydich A, Hysi E, Botyanszki Z, and Joshi NS (2017) Bootstrapped Biocatalysis: Biofilm-Derived Materials as Reversibly Functionalizable Multienzyme Surfaces. ChemCatChem 9 (23), 4328–4333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Nguyen PQ, Botyanszki Z, Tay PKR, and Joshi NS (2014) Programmable Biofilm-Based Materials from Engineered Curli Nanofibres. Nat. Commun 5, 4945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Seker UOS, Chen AY, Citorik RJ, and Lu TK (2017) Synthetic Biogenesis of Bacterial Amyloid Nanomaterials with Tunable Inorganic–Organic Interfaces and Electrical Conductivity. ACS Synth. Biol 6 (2), 266–275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Zhong C, Gurry T, Cheng AA, Downey J, Deng Z, Stultz CM, and Lu TK (2014) Strong Underwater Adhesives Made by Self-Assembling Multi-Protein Nanofibres. Nat. Nanotechnol 9, 858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Nicolay T, Vanderleyden J, and Spaepen S (2015) Autotransporter-Based Cell Surface Display in Gram-Negative Bacteria. Crit. Rev. Microbiol 41 (1), 109–123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Daugherty PS (2007) Protein Engineering with Bacterial Display. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol 17 (4), 474–480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Messner P, Schaffer C, Egelseer E-M, and Sleytr UB (2010) Occurrence, Structure, Chemistry, Genetics, Morphogenesis, and Functions of S-Layers In Prokaryotic Cell Wall Compounds: Structure and Biochemistry (KoÖnig H, Claus H, and Varma A, Eds.) pp 53–109, Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg. [Google Scholar]

- (15).Roberts K, Grief C, Hills GJ, and Shaw PJ (1985) Cell Wall Glycoproteins: Structure and Function. J. Cell Sci 2, 105–127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Lembcke G, Baumeister W, Beckmann E, and Zemlin F (1993) Cryo-Electron Microscopy of the Surface Protein of Sulfolobus Shibatae. Ultramicroscopy 49 (1), 397–406. [Google Scholar]

- (17).Smit J, Engelhardt H, Volker S, Smith SH, and Baumeister W (1992) The S-Layer of Caulobacter Crescentus: Three-Dimensional Image Reconstruction and Structure Analysis by Electron Microscopy. J. Bacteriol 174 (20), 6527–6538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Baranova E, Fronzes R, Garcia-Pino A, Van Gerven N, Papapostolou D, Peh́au-Arnaudet G, Pardon E, Steyaert J, Howorka S, and Remaut H (2012) SbsB Structure and Lattice Reconstruction Unveil Ca2+ Triggered S-Layer Assembly. Nature 487 (7405), 119–122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Messner P, Pum D, and Sleytr UB (1986) Characterization of the Ultrastructure and the Self-Assembly of the Surface Layer of Bacillus Stearothermophilus Strain NRS 2004/3a. J. Ultrastruct. Mol. Struct. Res 97 (1–3), 73–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Norville JE, Kelly DF, Knight TF, Jr, Belcher AM, and Walz T (2007) 7A Projection Map of the S-Layer Protein sbpA Obtained with Trehalose-Embedded Monolayer Crystals. J. Struct. Biol 160 (3), 313–323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Wildhaber I, and Baumeister W (1987) The Cell Envelope of Thermoproteus Tenax: Three-Dimensional Structure of the Surface Layer and Its Role in Shape Maintenance. EMBO J 6 (5), 1475–1480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Pum D, Messner P, and Sleytr UB (1991) Role of the S Layer in Morphogenesis and Cell Division of the Archaebacterium Methanocorpusculum Sinense. J. Bacteriol 173 (21), 6865–6873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Kern J, and Schneewind O (2010) BslA, the S-Layer Adhesin of B. Anthracis, Is a Virulence Factor for Anthrax Pathogenesis. Mol. Microbiol 75 (2), 324–332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Koval SF, and Hynes SH (1991) Effect of Paracrystalline Protein Surface Layers on Predation by Bdellovibrio Bacteriovorus. J. Bacteriol 173 (7), 2244–2249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Åvall-Jaäs̈kelaïnen S, Lindholm A, and Palva A (2003) Surface Display of the Receptor-Binding Region of the Lactobacillus Brevis S-Layer Protein in Lactococcus Lactis Provides Nonadhesive Lactococci with the Ability to Adhere to Intestinal Epithelial Cells. Appl. Environ. Microbiol 69 (4), 2230–2236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Sleytr UB, Schuster B, Egelseer E-M, and Pum D (2014) S-Layers: Principles and Applications. FEMS Microbiol. Rev 38 (5), 823–864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Ilk N, Egelseer EM, and Sleytr UB (2011) S-Layer Fusion Proteins construction Principles and Applications. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol 22 (6), 824–831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Patel J, Zhang Q, McKay RML, Vincent R, and Xu Z (2010) Genetic Engineering of Caulobacter Crescentus for Removal of Cadmium from Water. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol 160 (1), 232–243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Farr C, Nomellini JF, Ailon E, Shanina I, Sangsari S, Cavacini LA, Smit J, and Horwitz MS (2013) Development of an HIV-1 Microbicide Based on Caulobacter Crescentus: Blocking Infection by High-Density Display of Virus Entry Inhibitors. PLoS One 8 (6), e65965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (30).Bharat TAM, Kureisaite-Ciziene D, Hardy GG, Yu EW, Devant JM, Hagen WJH, Brun YV, Briggs JAG, and LÖwe J (2017) Structure of the Hexagonal Surface Layer on Caulobacter Crescentus Cells. Nat. Microbiol 2, 17059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (31).Laub MT, Shapiro L, and McAdams HH (2007) Systems Biology of Caulobacter. Annu. Rev. Genet 41, 429–441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (32).Crosson S, McGrath PT, Stephens C, McAdams HH, and Shapiro L (2005) Conserved Modular Design of an Oxygen Sensory/signaling Network with Species-Specific Output. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 102 (22), 8018–8023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (33).Amat F, Comolli LR, Nomellini JF, Moussavi F, Downing KH, Smit J, and Horowitz M (2010) Analysis of the Intact Surface Layer of Caulobacter Crescentus by Cryo-Electron Tomography. J. Bacteriol 192 (22), 5855–5865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (34).Bingle WH, Nomellini JF, and Smit J (1997) Cell-Surface Display of a Pseudomonas Aeruginosa Strain K Pilin Peptide within the Paracrystalline S-Layer of Caulobacter Crescentus. Mol. Microbiol 26 (2), 277–288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (35).Park DM, Reed DW, Yung MC, Eslamimanesh A, Lencka MM, Anderko A, Fujita Y, Riman RE, Navrotsky A, and Jiao Y (2016) Bioadsorption of Rare Earth Elements through Cell Surface Display of Lanthanide Binding Tags. Environ. Sci. Technol 50 (5), 2735–2742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (36).Gandham L, Nomellini JF, and Smit J (2012) Evaluating Secretion and Surface Attachment of SapA, an S-Layer-Associated Metalloprotease of Caulobacter Crescentus. Arch. Microbiol 194 (10), 865–877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (37).Zakeri B, Fierer JO, Celik E, Chittock EC, Schwarz- Linek U, Moy VT, and Howarth M (2012) Peptide Tag Forming a Rapid Covalent Bond to a Protein, through Engineering a Bacterial Adhesin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 109 (12), E690–E697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (38).Reddington SC, and Howarth M (2015) Secrets of a Covalent Interaction for Biomaterials and Biotechnology: SpyTag and SpyCatcher. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol 29, 94–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (39).Lau JHY, Nomellini JF, and Smit J (2010) Analysis of High-Level S-Layer Protein Secretion in Caulobacter Crescentus. Can. J. Microbiol 56 (6), 501–514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (40).Nomellini JF, Duncan G, Dorocicz IR, and Smit J (2007) S-Layer-Mediated Display of the Immunoglobulin G-Binding Domain of Streptococcal Protein G on the Surface of Caulobacter Crescentus: Development of an Immunoactive Reagent. Appl. Environ. Microbiol 73 (10), 3245–3253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (41).Hagen A, Sutter M, Sloan N, and Kerfeld CA (2018) Programmed Loading and Rapid Purification of Engineered Bacterial Microcompartment Shells. Nat. Commun 9 (1), 2881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (42).Bedbrook CN, Kato M, Ravindra Kumar S, Lakshmanan A, Nath RD, Sun F, Sternberg PW, Arnold FH, and Gradinaru V (2015) Genetically Encoded Spy Peptide Fusion System to Detect Plasma Membrane-Localized Proteins In Vivo. Chem. Biol 22 (8), 1108–1121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (43).Campbell RE, Tour O, Palmer AE, Steinbach PA, Baird GS, Zacharias DA, and Tsien RY (2002) A Monomeric Red Fluorescent Protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 99 (12), 7877–7882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (44).Muiznieks LD, Reichheld SE, Sitarz EE, Miao M, and Keeley FW (2015) Proline-Poor Hydrophobic Domains Modulate the Assembly and Material Properties of Polymeric Elastin: Role of Domain 30 in Elastin Assembly and Material Properties. Biopolymers 103 (10), 563–573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (45).Sun F, Zhang W-B, Mahdavi A, Arnold FH, and Tirrell DA (2014) Synthesis of Bioactive Protein Hydrogels by Genetically Encoded SpyTag-SpyCatcher Chemistry. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 111 (31), 11269–11274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (46).Wichner SM, Mann VR, Powers AS, Segal MA, Mir M, Bandaria JN, DeWitt MA, Darzacq X, Yildiz A, and Cohen BE (2017) Covalent Protein Labeling and Improved Single- Molecule Optical Properties of Aqueous CdSe/CdS Quantum Dots. ACS Nano 11 (7), 6773–6781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (47).Mann VR, Powers AS, Tilley DC, Sack JT, and Cohen BE (2018) Azide-Alkyne Click Conjugation on Quantum Dots by Selective Copper Coordination. ACS Nano 12 (5), 4469–4477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (48).Sakimoto KK, Wong AB, and Yang P (2016) Self- Photosensitization of Nonphotosynthetic Bacteria for Solar-to- Chemical Production. Science 351 (6268), 74–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (49).Rothfuss H, Lara JC, Schmid AK, and Lidstrom ME (2006) Involvement of the S-Layer Proteins Hpi and SlpA in the Maintenance of Cell Envelope Integrity in Deinococcus Radiodurans R1. Microbiology 152 (9), 2779–2787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (50).Gerbino E, Carasi P, Mobili P, Serradell MA, and Goḿez-Zavaglia A (2015) Role of S-Layer Proteins in Bacteria. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol 31 (12), 1877–1887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (51).Schultze-Lam S, Harauz G, and Beveridge TJ (1992) Participation of a Cyanobacterial S Layer in Fine-Grain Mineral Formation. J. Bacteriol 174 (24), 7971–7981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (52).Küpcü, S., Mader, C., and Saŕa, M. (1995) The Crystalline Cell Surface Layer from Th2013cus L111–69 as an Immobilization Matrix: Influence of the Morpho- logical Properties and the Pore Size of the Matrix on the Loss of Activity of Covalently Bound Enzymes. Biotechnol. Appl. Biochem 21 (3), 275–286. [Google Scholar]

- (53).Martín MJ, Lara-Villoslada F, Ruiz MA, and Morales ME (2015) Microencapsulation of Bacteria: A Review of Different Technologies and Their Impact on the Probiotic Effects. Innovative Food Sci. Emerging Technol 27, 15–25. [Google Scholar]

- (54).Schoebitz M, López MD, and Roldań A (2013) Bioencapsulation of Microbial Inoculants for Better Soil–plant Fertilization. A Review. Agron. Sustainable Dev 33, 751. [Google Scholar]

- (55).Herrero M, and Stuckey DC (2015) Bioaugmentation and Its Application in Wastewater Treatment: A Review. Chemosphere 140, 119–128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (56).Kandemir N, Vollmer W, Jakubovics NS, and Chen J (2018) Mechanical Interactions between Bacteria and Hydrogels. Sci. Rep 8 (1), 10893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (57).Azam A, and Tullman-Ercek D (2016) Type-III Secretion Filaments as Scaffolds for Inorganic Nanostructures. J. R. Soc., Interface 13 (114), 20150938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (58).Toporowski MC, Nomellini JF, Awram P, and Smit J (2004) Two Outer Membrane Proteins Are Required for Maximal Type I Secretion of the Caulobacter Crescentus S-Layer Protein. J. Bacteriol 186 (23), 8000–8009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (59).Schneider CA, Rasband WS, and Eliceiri KW (2012) NIH Image to ImageJ: 25 Years of Image Analysis. Nat. Methods 9 (7), 671–675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.