Soybean meiocyte-specific small RNAs display a positive association with the coding region of genes that are transcriptionally upregulated during meiosis.

Abstract

Meiosis is a critical process for sexual reproduction. During meiosis, genetic information on homologous chromosomes is shuffled through meiotic recombination to produce gametes with novel allelic combinations. Meiosis and recombination are orchestrated by several mechanisms including regulation by small RNAs (sRNAs). Our previous work in Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana) meiocytes showed that meiocyte-specific sRNAs (ms-sRNAs) have distinct characteristics, including positive association with the coding region of genes that are transcriptionally upregulated during meiosis. Here, we characterized the ms-sRNAs in two important crops, soybean (Glycine max) and cucumber (Cucumis sativus). Ms-sRNAs in soybean have the same features as those in Arabidopsis, suggesting that they may play a conserved role in eudicots. We also investigated the profiles of microRNAs (miRNAs) and phased secondary small interfering RNAs in the meiocytes of all three species. Two conserved miRNAs, miR390 and miR167, are highly abundant in the meiocytes of all three species. In addition, we identified three novel cucumber miRNAs. Intriguingly, our data show that the previously identified phased secondary small interfering RNA pathway involving soybean-specific miR4392 is more abundant in meiocytes. These results showcase the conservation and divergence of ms-sRNAs in flowering plants, and broaden our understanding of sRNA function in crop species.

Meiosis is a specialized cell division in sexually reproducing eukaryotes that generates gametes. In meiosis, the meiotic mother cell divides twice after one round of premeiotic DNA replication to produce haploid germline cells. A key difference between meiosis and mitosis is that meiosis includes a process called “meiotic recombination,” whereby genetic information is shuffled between homologous chromosomes to generate novel allelic combinations in the daughter cells. Decades of studies in plants, animals, and fungi have enabled a basic understanding of the mechanisms that mediate meiotic recombination (Ma, 2006; Osman et al., 2011; Hunter, 2015; Wang and Copenhaver, 2018), but many questions still remain.

Epigenetic features including nucleosome position, histone modification, and DNA methylation have also been reported to affect the frequency and distribution of meiotic crossovers (COs; Choi et al., 2013, 2018; Underwood et al., 2018) at local and genome-wide scales. COs are not distributed evenly along chromosomes, but instead cluster in small regions called “CO hotspots.” COs favor an open-chromatin environment marked by low nucleosome density, reduced cytosine methylation, and methylation at Lys 4 of the histone H3 tail in all eukaryotes studied (Borde et al., 2009; Baudat et al., 2010; Pan et al., 2011; Yelina et al., 2012, 2015; Choi et al., 2018; Underwood et al., 2018). In many metazoans, the SET-domain protein PRDM9 catalyzes H3K4 and H3K36 methylation to designate CO hotspots (Baudat et al., 2010). In species that lack PRDM9, including Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana) and Schizosaccharomyces pombe, CO hotspots positively correlated with the histone H2A variant H2A.Z (Choi et al., 2013; Yamada et al., 2018).

Small RNAs (sRNAs) are another important epigenetic feature that regulate gene expression. Endogenous sRNAs in plants range from 20 to 24 nucleotides (nt) and are mainly categorized into two classes: microRNAs (miRNAs), and small-interfering RNAs (siRNAs; Axtell, 2013; Borges and Martienssen, 2015). Plant miRNAs are typically 20–22 nt in length, and function in posttranscriptional gene silencing through mRNA cleavage or translational repression (Rogers and Chen, 2013). In animals and plants, miRNAs play an important role in male germline and embryonic development (Borges et al., 2011; Conine et al., 2018; Zhao et al., 2018). Another large group of sRNAs in plants constitute the 20 to 24 nt siRNAs, which function primarily in transcriptional gene silencing of viral DNA, transgenes, and transposable elements (TEs; Borges and Martienssen, 2015) through the RNA-directed DNA methylation pathway. In addition, several studies have reported highly conserved tRNA-derived sRNAs (tsRNAs) and rRNA-derived sRNAs (rsRNAs) within a wide range of species, which have diverse biological functions in regulating ribosome biogenesis and translation initiation, and are associated with disease states when disrupted (Chen et al., 2016; Chu et al., 2017; Gebetsberger et al., 2017; Kim et al., 2017). Recently, DNA double-strand break (DSB)-induced sRNAs have been implicated in homologous repair (HR) of DNA damage in plant and vertebrate somatic cells (Francia et al., 2012; Michalik et al., 2012; Wei et al., 2012). Mammalian RNA polymerase II is recruited to somatic DSB sites to synthesize damage-induced long noncoding RNAs (Michelini et al., 2017), which then recruit BRCA1, BRCA2, and RAD51 (D’Alessandro et al., 2018). BRCA1 physically interacts with DROSHA and other components of the DROSHA microprocessor complex and increases the expression of specific miRNAs (Kawai and Amano, 2012). In addition, somatic DSBs in human rDNA have been shown to induce production of substantial levels of either Dicer-dependent or Dicer-independent DSB-induced sRNAs, which contribute to HR (Bonath et al., 2018). Because HR and meiotic recombination share several conserved processes, we wondered whether repair of meiotic DSBs also requires the help of sRNAs. Our previous work in Arabidopsis revealed ∼2,500 meiocyte-specific sRNA (ms-sRNA) clusters that are positively associated with genes preferentially expressed during meiosis including AtRAD51 and Arabidopsis SKP1-LIKE1 (ASK1; Huang et al., 2019). Furthermore, two thirds of the ms-sRNAs are AtSPO11-1-dependent, suggesting a potential role in meiotic DSB repair (Huang et al., 2019). However, little is known about ms-sRNAs in other plant species, or the potential roles that other sRNA classes play in plant meiocytes.

Soybean (Glycine max) is a major source of oil and protein consumed by humans and farm animals. It is among ∼17,000 species of legumes in the family Fabaceae (Group et al., 2016). Cucumber (Cucumis sativus) is a globally important vegetable crop in the Cucurbitaceae family (Group et al., 2016). Both Fabaceae and Cucurbitaceae are in the nitrogen-fixing clade (Group et al., 2016) and belong to the Rosids group, which also includes Arabidopsis (Brassicaceae), and comprises ∼40% of eudicots. Eudicots account for ∼70% of all angiosperms. Therefore, to test whether ms-sRNAs with similar characteristics to those found in Arabidopsis (Huang et al., 2019) exist in Rosids or eudicots, we analyzed the sRNA profiles in meiocytes from soybean and cucumber. We found that ms-sRNAs in soybean meiocytes are also enriched on genic regions and have a positive association with genes that are upregulated in meiosis, including soybean CENTROMERE SPECIFIC HISTONE3 (GmCENH3) and soybean ARGONAUTE4 (GmAGO4). In addition, we found that miR390 and miR167 are conserved among the three species and are preferentially expressed in meiocytes. We also discovered three novel miRNAs and three phased secondary small interfering RNA-associated genes (PHAS genes) in cucumber, as well as three meiocyte-specific PHAS genes in soybean. Furthermore, our data demonstrate that the soybean-specific miR4392-phased secondary small interfering RNA (phasiRNA) pathway is active in soybean meiocytes, but not leaves.

RESULTS

Identification of miRNAs Preferentially Expressed in Arabidopsis, Soybean, and Cucumber Meiocytes

To comprehensively profile meiocyte sRNAs from soybean and cucumber, we used a microcapillary meiocyte isolation method (see “Materials and Methods” for details). To ensure that the isolated meiocytes were undergoing meiosis, we examined chromosome spreads from both soybean and cucumber samples, and observed a mixture of all meiotic stages (Supplemental Figs. S1 and S2). We sequenced two biological replicates from each library (Supplemental Table S1), and obtained leaf sRNA data from public databases. We compared these to our previously published Arabidopsis meiocyte and leaf datasets (Huang et al., 2019). The correlation coefficients between the two soybean and cucumber meiocyte biological replicates is 0.87 and 0.96, respectively (Supplemental Table S2). By comparing our mapped sRNA reads to annotated genomic features, we were able to divide them into four groups: miRNAs, tsRNAs, rsRNAs, and other sRNAs. Of 341,931,242 raw reads from 12 sRNA libraries, 56.7% (193,736,065) were genome-matched, of which 15- to 35-nt reads included 8.6% (16,617,245) miRNAs, 4.6% (8,923,232) tsRNAs (from 25- to 35-nt), 5.5% (10,616,898) rsRNAs, and 14.3% (27,660,302) other reads (Supplemental Table S1).

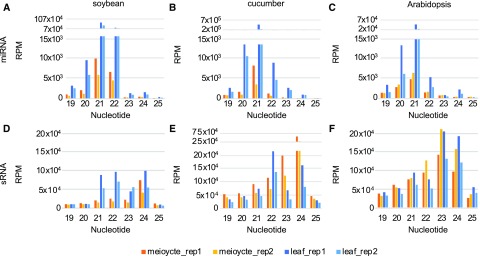

We normalized the sRNA abundance of each library to reads per million (RPM) and analyzed the read size distribution for the four sRNA categories. Soybean, cucumber, and Arabidopsis meiocyte and leaf miRNAs have a major peak at 21-nt (Fig. 1, A–C). Soybean has a smaller peak at 22-nt (Fig. 1A), whereas cucumber and Arabidopsis have a smaller peak at 20-nt (Fig. 1, B and C). Meiocyte miRNAs have a lower abundance than those in leaves in all three species (Fig. 1, A–C). After filtering rsRNAs, tsRNAs, miRNAs, and other annotated sRNAs, both soybean and cucumber meiocyte sRNAs have a dominant peak at 24-nt (Fig. 1, D and E) in contrast to the 23-nt peak in Arabidopsis (Fig. 1F). After applying the same filter to the leaf data, soybean has multiple peaks from 21- to 24-nt and cucumber has two peaks at 22- and 24-nt (Fig. 1, D and E). We also analyzed the read size distribution of tsRNAs and rsRNAs in the three species. Meiocyte rsRNAs are relatively low in abundance and have a uniform read size distribution from 15- to 35-nt except for a subtle small peak at 20 nt in all three species (Supplemental Fig. S3, A–C). Cucumber also has two additional peaks at 15- and 16-nt. Soybean and Arabidopsis have distinct meiocyte tsRNA peaks at 32- and 33-nt (Supplemental Fig. S3, A–C), which contrasts with cucumber that has low tsRNA abundance from 25- to 35-nt (Supplemental Fig. S3E; Supplemental Table S1).

Figure 1.

Size distribution of miRNAs and filtered sRNAs in soybean, cucumber, and Arabidopsis. A, Mappable miRNA size (19–25-nt) distribution from soybean. Each sample has two biological replicates. sRNA abundance was normalized in RPMs. B, Size distribution of mappable miRNAs from cucumber. C, Size distribution of mappable miRNAs from Arabidopsis (Huang et al., 2019). D, Size distribution of mappable sRNAs after filtering annotated sRNA from soybean. E, Size distribution of mappable sRNAs after filtering annotated sRNA from cucumber. F, Size distribution of mappable sRNAs after filtering annotated sRNA from Arabidopsis.

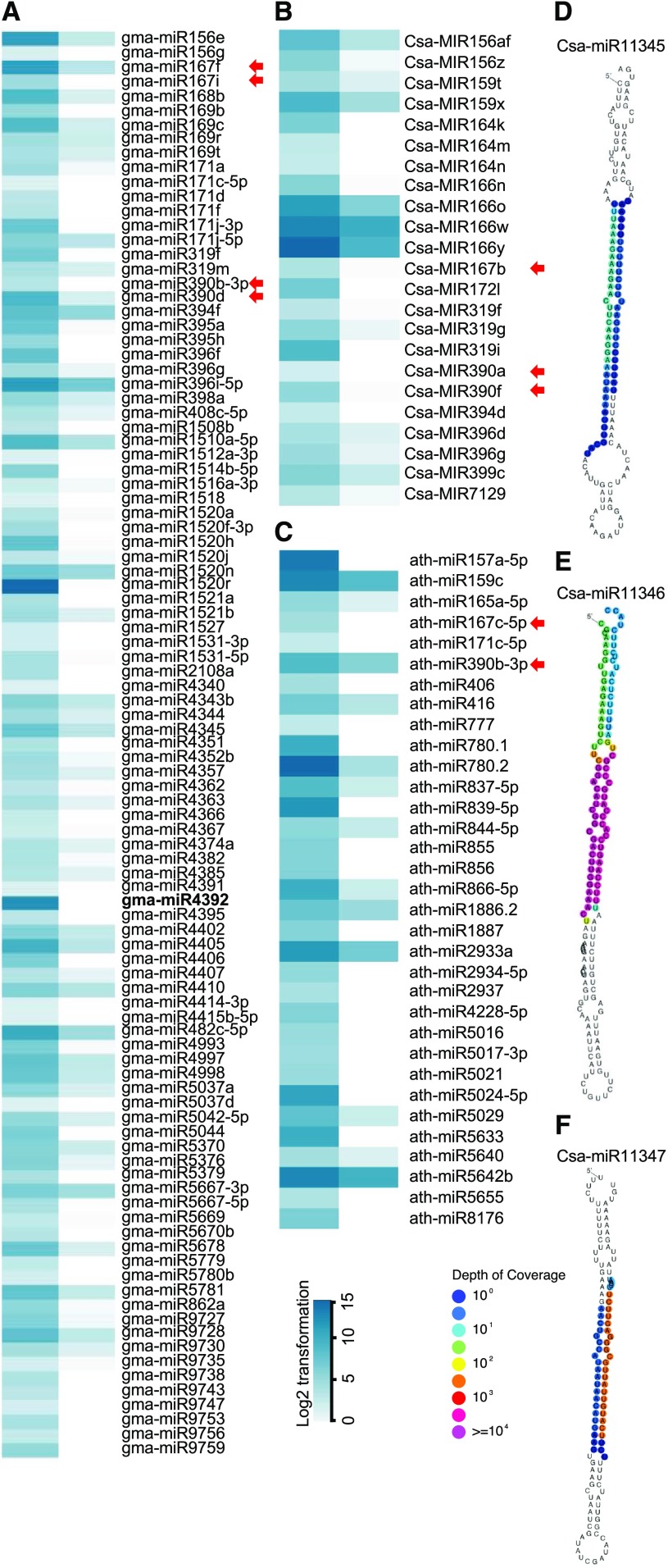

Prior analysis of Arabidopsis miRNA biogenesis loss-of-function mutants revealed a defect in meiotic chromatin morphology (Oliver et al., 2017). However, the role of specific miRNAs in meiocytes remains unclear. We identified 230 and 101 mature miRNAs from soybean and Arabidopsis meiocytes, respectively, which accounts for 30% (230/756) and 24% (101/428) of the known miRNAs in each species. The 230 soybean meiocyte miRNAs correspond to 212 miRNA gene loci and 156 miRNA families, whereas the 101 Arabidopsis meiocyte miRNAs correspond to 92 miRNA gene loci and 83 miRNA families. In cucumber meiocytes, we identified 121 conserved mature miRNAs from 26 miRNA families. Compared to leaves, meiocytes express fewer miRNAs (230 versus 293 in soybean, 101 versus 207 in Arabidopsis, and 121 versus 142 in cucumber; Fig. 2, A–C; Supplemental Datasets S1–S3). However, we identified 99 (29%), 23 (10%), and 33 (15%) miRNAs in soybean, cucumber, and Arabidopsis meiocytes, respectively, that are preferentially expressed in meiocytes (defined as 4-fold greater abundance in meiocytes than in leaves; Fig. 2, A–C). Of these, miR390 (which triggers TAS3 gene family tasiRNA production; Montgomery et al., 2008) and miR167 both show enrichment in meiocytes in all three species (Fig. 2, A–C). Interestingly, both miRNAs in Arabidopsis target AUXIN RESPONSIVE FACTOR (ARF) genes to regulate ovule and anther development, and their mutants have reduced fertility (Fahlgren et al., 2006; Wu et al., 2006). miR390 and miR167 are also two of the 20 secondary siRNA-triggering miRNAs reported in Arikit et al. (2014). Furthermore, miR4392, a known soybean-specific phasiRNA trigger, is enriched in soybean meiocytes (Fig. 2A; Supplemental Dataset S1).

Figure 2.

miRNAs preferentially expressed in soybean, cucumber, and Arabidopsis meiocytes. A, Heatmap showing the expression profiles of 99 miRNAs preferentially expressed in soybean meiocytes. B, Expression profiles of 23 conserved miRNAs preferentially expressed in cucumber meiocytes. C, Expression profiles of 33 Arabidopsis miRNAs preferentially expressed in meiocytes. D to F, Secondary structure of predicted miRNA Csa-miR11345 (D), Csa-miR11346 (E), and Csa-miR11347 (F). Blue color from light to dark in (A) to (C) corresponds to miRNA abundance from low to high RPM. Original RPM values were transformed to log2(RPM+1) for normalization. Red arrows indicate miR390 and miR167 families conserved among the three species. A soybean-specific phasiRNA trigger miR4392 in soybean is in bold. Depth of coverage for (D) to (F) from deep blue to pink represents read coverage from low to high.

Using the 2018 criteria for annotating plant miRNAs established by Axtell and Meyers (2018), we identified one novel miRNA from cucumber meiocytes (Csa-miR11345) and two from leaves (Csa-miR11346 and Csa-miR11347; Fig. 2, D–F). The target prediction analyzer psRNATarget found 105, 87, and 83 candidate target genes for Csa-miR11345, Csa-miR11346, and Csa-miR11347, respectively, in the cucumber genome using a mismatch parameter of “2” (Table 1; Supplemental Dataset S4). For Csa-miR11345, the top five candidate target genes include those encoding the DNA binding homeobox and different transcription factors domain-containing protein (CsaV3_6G014620), HASTY1 (CsaV3_2G004460), pelota homolog (CsaV3_2G010350), Arabidopsis pentatricopeptide repeat-containing (PPR) protein At5g18950 homolog (CsaV3_3G008450), and glycosyl transferase (CsaV3_5G035780; Table 1). Gene ontology (GO) analysis found that protein phosphorylation (GO: 0006468, 12/105, P value = 2.6e-2) is enriched in Csa-miR11345-targeted candidates (Supplemental Dataset S5). We found no enriched GO terms among the Csa-miR11346 and Csa-miR11347 predicted target genes.

Table 1. Predicted top5 target genes of three novel miRNAs from cucumber.

| ID | Expectation | Unpaired Energy | Inhibition | Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| csa_miR11345 (UUAAAGAAAGAACUUCAAGGA) | ||||

| CsaV3_6G014620 | 2 | 21.016 | Cleavage | DDT domain-containing protein PTM |

| CsaV3_2G004460 | 3 | 16.077 | Cleavage | Protein HASTY 1 |

| CsaV3_2G010350 | 3 | 9.888 | Translation | Protein pelota homolog |

| CsaV3_3G008450 | 3 | 17.447 | Cleavage | PPR-containing protein At5g18950 |

| CsaV3_5G035780 | 3 | 19.717 | Cleavage | Glycosyl transferase, family 1 |

| csa_miR11347 (UCAUGUUAUUGCGGGAGUUCU) | ||||

| CsaV3_4G033620 | 2 | 20.749 | Cleavage | Early nodulin-like protein |

| CsaV3_3G010020 | 3.5 | 17.08 | Translation | HOPM interactor 7 |

| CsaV3_1G033450 | 4 | 17.754 | Cleavage | PPR |

| CsaV3_2G031260 | 4 | 14.957 | Cleavage | Receptor protein kinase, putative |

| CsaV3_3G000620 | 4 | 20.559 | Cleavage | SKP1-like protein |

| Csa_miR11346 (GGACAUCGGCGACUUGGAAAC) | ||||

| CsaV3_4G002540 | 2.5 | 15.222 | Cleavage | Small G protein signaling modulator 1 isoform X1 |

| CsaV3_4G007160 | 3 | 24.25 | Cleavage | ABC transporter G family member 14 |

| CsaV3_4G030550 | 3 | 16.303 | Cleavage | Phloem lectin |

| CsaV3_4G030560 | 3 | 12.827 | Cleavage | Phloem lectin |

| CsaV3_1G030420 | 3.5 | 16.03 | Cleavage | Beta-1,4-mannosyl-glycoprotein 4-beta-n-acetylglucosaminyltransferase |

Characterization of Soybean and Cucumber sRNA Clusters after miRNA, tsRNA, and rsRNA Filtering

After filtering annotated sRNAs including miRNAs, tsRNAs, and rsRNAs, the predominant sRNA length class in soybean and cucumber meiocytes is 24-nt (Fig. 1, D and E). In soybean, 33,151 and 22,155 sRNA clusters were identified from the two meiocyte libraries, and 27,606 and 19,953 sRNA clusters from the leaf libraries, which yielded 9,352 meiocyte clusters and 13,063 leaf clusters using a conservative minimum overlap of 60% between the two replicates (Table 2). In cucumber, 37,059 and 37,583 sRNA clusters were identified from the two meiocyte libraries, and 33,977 and 32,170 sRNA clusters from the leaf libraries, which yielded 24,777 consensus meiocyte sRNA clusters and 16,613 consensus leaf sRNA clusters (Table 2). Like Arabidopsis, soybean has fewer sRNA clusters in meiocytes than in leaves (Table 2). By contrast, cucumber has more sRNA clusters in meiocytes than in leaves (Table 2).

Table 2. sRNA clusters in this study.

Calculated by the program ShortStack, ≥3 RPM, overlapping >60%.

| Genotype | Cluster No. | Shared Cluster No. |

|---|---|---|

| Soybean meiocyte_rep1 | 33,151 | 9,352 |

| Soybean meiocyte_rep2 | 22,155 | |

| Cucumber meiocyte_rep1 | 37,059 | 24,777 |

| Cucumber meiocyte_rep2 | 37,583 | |

| Arabidopsis meiocyte_rep1 | 14,352 | 6,727 |

| Arabidopsis meiocyte_rep2 | 10,666 | |

| Soybean leaf_rep1 | 27,606 | 13,063 |

| Soybean leaf_rep2 | 19,953 | |

| Cucumber leaf_rep1 | 33,977 | 16,613 |

| Cucumber leaf_rep2 | 32,170 | |

| Arabidopsis leaf_rep1 | 16,692 | 11,753 |

| Arabidopsis leaf_rep2 | 16,329 |

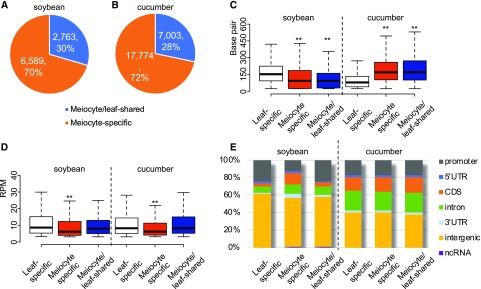

By comparing leaf and meiocyte clusters, meiocyte sRNA clusters can be divided into two groups: ms-sRNA clusters that are absent in the leaf sRNA cluster set, and meiocyte/leaf-shared sRNA (mls-sRNA) clusters. Seventy percent (6,589) of sRNA clusters in soybean and 72% (17,774) in cucumber are ms-sRNA clusters (Fig. 3, A and B). We compared the cluster length and abundance of leaf-specific (ls-, leaf sRNA clusters having no or <60% overlap with meiocyte sRNA clusters), ms-, and mls-sRNA and found that the median length of soybean ms-sRNA (93 bp) and mls-sRNA clusters (92 bp) were significantly shorter than that of the ls-sRNA clusters (152 bp; Mann–Whitney tests, both P values < 2.2e-16; Fig. 3C, left). A similar trend was previously observed in Arabidopsis (Huang et al., 2019). In contrast, the median lengths of cucumber ms- (169 bp) and mls-sRNA clusters (170 bp) were significantly longer than that of the ls-sRNA clusters (79 bp; Mann–Whitney tests, both P values < 2.2e-16; Fig. 3C, right). However, sRNA abundance in the soybean and cucumber ms-sRNA clusters is significantly lower than the other two cluster sets (Mann–Whitney tests, both P values < 2.2e-16; Fig. 3D).

Figure 3.

Characteristics of sRNA clusters in soybean and cucumber meiocytes. A and B, 70% and 72% of sRNA clusters found in meiocytes are meiocyte-specific in soybean and cucumber, respectively. C, sRNA cluster length in soybean and cucumber. D, sRNA cluster abundance in soybean and cucumber (**P value < 2.2e-16 from Mann–Whitney test). E, Genomic feature distributions of sRNA in soybean and cucumber. ncRNA, non-coding RNA; UTR, untranslated region.

Ms-sRNA Clusters in Soybean Tend To Localize with Coding Sequences

Plant-specific RNA polymerase IV-dependent siRNAs, which silence transposons and repetitive DNA to maintain chromatin structure and genome stability, constitute a large fraction of sRNAs in somatic cells (Onodera et al., 2005). Previously, we showed that Arabidopsis ms-sRNAs are distinct in that they are enriched in the coding region of genes (Huang et al., 2019). To test whether other plants have a similar pattern, we compared genomic position of ls-, ms-, and mls-sRNA clusters in soybean and cucumber. In soybean, most clusters in all three groups mapped to intergenic regions (Fig. 3E, first to third columns). For the ls- and mls-sRNA clusters, promoters, introns, and coding sequences (CDSs) are the second to fourth most occupied features (Fig. 3E, first and third columns). Consistent with the pattern we observed in Arabidopsis, CDS-derived reads increased significantly to 14% for the ms-sRNA clusters compared to 4% for the ls-sRNA clusters and 5% for the mls-sRNA clusters in soybean (Fig. 3E, first to third columns). In cucumber, intergenic regions, introns, promoters, and CDSs are the first to fourth most occupied features in all three groups (Fig. 3E, fourth to sixth columns), indicating that the enrichment of ms-sRNA clusters at CDS observed in Arabidopsis and soybean is not shared by cucumber.

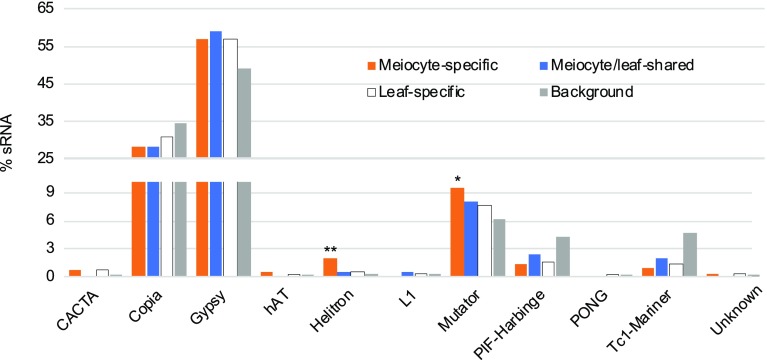

The SoyTE database contains 38,581 TEs annotated in the soybean genome (Du et al., 2010). We compared these TEs to our sRNA clusters and found that 12% (1,216 of 10,512) of ls-sRNA clusters are associated with TEs. In contrast, only 6% (164 of 2,763) mls-sRNA clusters and 5% (306 of 6,589) ms-sRNA clusters map to TEs (both P value < 2.2e-16 by Fisher’s exact test). This is consistent with the previous finding that Arabidopsis ms-sRNA clusters are less frequently associated with TEs (Huang et al., 2019). Of the 11 TE super families in soybean, Gypsy (19,052 members; belonging to the LTR type retrotransposons), Copia (13,318 members; also LTR type retrotransposons), and Mutator (2,373 members; DNA transposon) are the three most abundant (Du et al., 2010). In ms-, mls-, and ls-sRNA clusters that associate soybean TEs, Gypsy (174/96/691), Copia (86/46/375), and Mutator (29/13/91) are also the three most abundant (Fig. 4). Helitron and Mutator elements, while lower in abundance, are significantly overrepresented among TEs associated with ms-sRNA clusters (P value = 7.8e-5 and 0.034 by Fisher’s exact tests) compared with TEs corresponding to mls- (P value = 0.298 and 0.335 by Fisher’s exact tests) and ls-sRNA clusters (P value = 0.195 and 0.081 by Fisher’s exact tests). The enrichment of ms-sRNA clusters with Helitron families is similar to the pattern observed in Arabidopsis (Huang et al., 2019), which may suggest a conserved relationship between ms-sRNA and this class of TEs. Unfortunately, the current annotation of the cucumber genome is not robust enough to enable validation of the pattern.

Figure 4.

Meiocyte sRNAs with homology to TE superfamilies in soybean. Distribution of ms-, mls-, and ls-sRNA clusters among TE superfamilies. **P value = 7.8e-5, and *P value = 0.034 both by Fisher’s exact test.

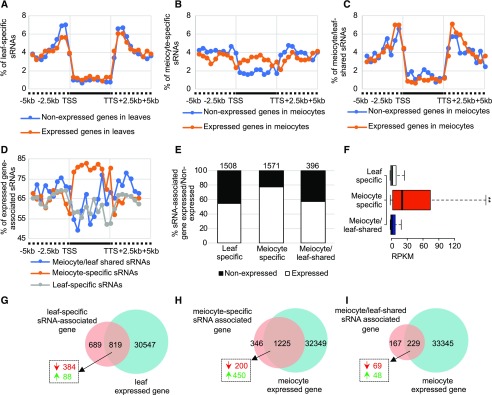

Soybean ms-sRNAs Are Positively Associated with Gene Expression in Meiocytes

To explore the relationship between the coding region-enriched soybean ms-sRNAs (Fig. 3E) and gene expression, we performed mRNA-sequencing (mRNA-seq) on the same samples used for sRNA sequencing (Supplemental Table S3) and obtained 33,574 and 31,366 expressed genes from meiocytes and leaves, respectively. Correlation coefficients between the two biological replicates were 0.96 and 0.99, respectively (Supplemental Table S2). We mapped ms-, mls-, and ls-sRNAs to intervals that included 5 kb upstream of transcription start sites (TSSs), the gene body (from TSS to transcription termination site [TTS]), and 5 kb downstream of TTSs of expressed/nonexpressed genes. We found that ms-sRNAs map more frequently to the gene body region of expressed genes (∼3% of total sRNAs) than those of nonexpressed genes (∼2% of total sRNAs; Fig. 5B). By contrast, ls- and mls-sRNAs map relatively less frequently to gene body regions (∼1% of total sRNAs) of expressed genes and don’t show obvious difference between expressed/nonexpressed gene body regions (Fig. 5, A and C). In leaves, ∼66% of the sRNAs found upstream of TSSs, 58% of those in the gene body, and 64% of those downstream of TTSs are associated with expressed genes (Fig. 5D). The mls-sRNAs have a similar profile (Fig. 5D). Strikingly, whereas the upstream and downstream profiles of the ms-sRNAs also look similar, ∼80% of the ms-sRNAs within the gene body are associated with expressed genes (Fig. 5D).

Figure 5.

Soybean ms-sRNAs are positively correlated with meiotic gene expression. A, Distribution of ls-sRNAs around unexpressed and expressed genes in leaves. Intervals are partitioned into up- and down-stream regions (dashed line) and gene body (solid line) between TSSs and TTSs. B, Distribution of ms-sRNAs around unexpressed and expressed genes in meiocytes. C, Distribution of mls-sRNAs around unexpressed and expressed genes in meiocytes. D, Distribution of mls-, ms-, and ls-sRNAs around expressed genes. E, Histogram of mls-, ms-, and ls-sRNA–associated unexpressed and expressed genes. F, Gene expression value of mls-, ms-, and ls-sRNA–associated genes. **P value < 2.2e-16, Mann–Whitney test. G, Venn diagram showing 19% of differentially expressed genes (dashed box) are upregulated genes (green arrow, [q value < 0.05, log2 (fold change) > 1]) among ls-sRNA–associated genes, as opposed to downregulated (red arrow, [q value < 0.05, log2 (fold change) < −1]). H, Venn diagram showing 69% of the differentially expressed genes (dashed box) among the ms-sRNA–associated genes are upregulated (green arrow, [q value < 0.05, log2 (fold change) > 1]) as opposed to downregulated (red arrow, [q value < 0.05, log2 (fold change) < −1]). I, Venn diagram showing 41% of the differentially expressed genes (dashed box) among the mls-sRNA–associated genes are upregulated (green arrow, [q value < 0.05, log2 (fold change) > 1]) as opposed to downregulated (red arrow, [q value < 0.05, log2 (fold change) < −1]).

Among the soybean gene-body–associated sRNAs we characterized, ms-RNAs map to 1,571 genes, mls-sRNAs map to 396 genes, and ls-sRNAs map to 1,508 genes. Fifty-four percent (819) of ls-sRNA–associated genes and 58% (229) of mls-sRNA–associated genes are expressed (Fig. 5E). Notably, 78% (1,225) of the ms-sRNA–associated genes are expressed (Fig. 5E). Among these three groups, the 1,225 ms-sRNA–associated genes have a significantly higher median gene expression value of 26.2 RPKM (reads per kilobase of exon model mapped RPMs) compared to 4.2 and 4.4 RPKM for the 229 mls-sRNA- and 819 ls-sRNA–associated genes, respectively (both P value < 2.2e-16 by Mann–Whitney tests; Fig. 5F). These observations suggest a positive correlation between ms-sRNAs and gene expression in soybean meiocytes.

Among the 1,225 ms-sRNA–associated genes expressed in meiocytes, 650 are differentially expressed (q value < 0.05, log2 [fold change] < −1 or > 1) between meiocytes and leaves. The majority (450) are upregulated (log2 [fold change] > 1), whereas 200 are downregulated (log2 [fold change] < −1; Fig. 5H). This pattern is the opposite of that observed in the ls-sRNA– and mls-sRNA–associated genes (Fig. 5, G and I). These data suggest that ms-sRNAs are different compared to their somatic cell counterparts and are correlated with the upregulation of meiotically expressed genes.

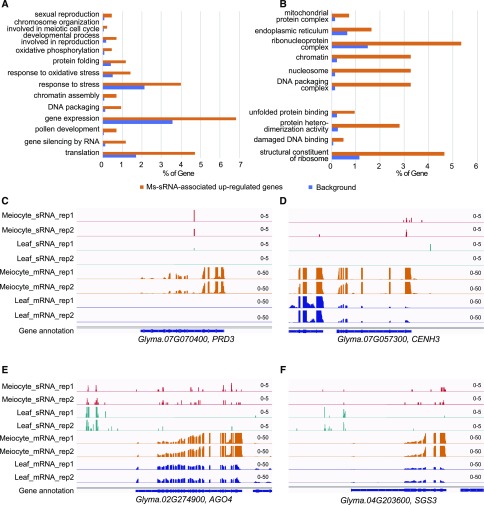

GO Analysis of Upregulated Genes Associated with ms-sRNAs in Soybean

To determine if there are any commonalities among the 450 meiotically upregulated genes associated with ms-sRNAs, we performed GO enrichment analysis (Mi et al., 2019). The results showed enrichment in 17 biological processes, seven molecular functions, and 25 cellular components (false discovery rate q value < 0.05; Fig. 6; Supplemental Datasets S6–S8). The biological process (Fig. 6A) can be subdivided into three groups. There is a chromosome-structure–related group that includes DNA packaging (GO: 0006323, 4/61, P value = 1.5e-3) and chromatin assembly (GO: 0031497, 3/49, P value = 3.4e-3). There is a transcription/translation related group that includes translation (GO: 0006412, 20/933, P value = 5.1e-5), gene silencing by RNA (GO: 0031047, 5/71, P value = 2.9e-4), protein folding (GO: 0006457, 5/217, P value = 2.8e-2), and gene expression (GO: 0010467, 29/1970, P value = 9.0e-4). Of particular note, there is a meiosis-related group that includes the developmental process involved in reproduction (GO: 0003006, 3/88, P value = 3.2e-2), chromosome organization involved in the meiotic cell cycle (GO: 0070192, 1/4, P value = 3.7e-2), and sexual reproduction (GO: 0019953, 2/40, P value = 4.0e-2; Fig. 6A). The enriched molecular functions include structural constituent of ribosome (GO: 0003735, 20/645, P value = 2.5e-7), protein heterodimerization activity (GO: 0046982, 12/148, P value = 4.3e-9), damaged DNA binding (GO: 0003684, 2/26, P value = 1.9e-2), and unfolded protein binding (GO: 0051082, 4/130, P value = 1.9e-2; Fig. 6B). The cellular components can be divided into two groups. The first contains terms related to translation: the ribonucleoprotein complex (GO: 1990904, 23/849, P value = 3.2e-7) and the endoplasmic reticulum (GO: 0005783, 7/359, P value = 2.2e-2). The second is a chromatin-related group (Fig. 6B), consisting of the DNA packaging complex (GO: 0044815, 14/87, P value = 4.7e-14), the nucleosomes (GO: 0000786, 14/82, P value = 2.3e-14), and chromatin (GO: 0000785, 14/112, P value = 1.1e-12).

Figure 6.

ms-sRNA–associated upregulated genes in soybean meiocytes. A, GO term enrichment analysis of the 450 ms-sRNA–associated meiocyte upregulated genes in soybean from categories of biological process. B, GO term enrichment analysis of the 450 ms-sRNA–associated meiocyte upregulated genes in soybean from categories of cellular component and molecular function. C, Snapshot showing that ms-sRNA clusters on meiotic essential gene PRD3 in soybean. D, Snapshot showing that ms-sRNA clusters on meiotic essential gene CENH3 in soybean. E, Snapshot showing that ms-sRNA clusters on sRNA biogenesis gene AGO4 in soybean. F, Snapshot showing that ms-sRNA clusters on sRNA biogenesis gene SGS3 in soybean.

The soybean putative orthologs of PUTATIVE RECOMBINATION INITIATION DEFECTS3 (PRD3) and CENH3 are in the sexual reproduction GO gene set, whereas AGO4 and SUPPRESSOR OF GENE SILENCING3 (SGS3) are in the gene silencing GO gene set. All four genes are (as defined by the analysis) meiotically upregulated and associated with ms-sRNAs (Fig. 6, C–F). PRD3 is a novel plant-specific protein required for meiotic DSB formation (De Muyt et al., 2009). CENH3 encodes a centromere-specific histone H3 variant with an N-terminal domain that is essential for modulating meiotic centromere behavior (Ravi et al., 2011). AGO4 is an AGO protein that mediates siRNA biogenesis (Zilberman et al., 2003) and SGS3 is a key factor in posttranscriptional gene silencing and tasiRNA production (Peragine et al., 2004). However, the cucumber homologs of these genes do not appear to share similar associations (Supplemental Fig. S4). Furthermore, our previous work showed RAD51 and ASK1 are both positively associated with ms-sRNAs in Arabidopsis (Huang et al., 2019). We analyzed the sRNA profiles of their homologs in soybean and cucumber. Soybean has two RAD51 homologs, Glyma.13G175300 and Glyma.17G049800, and we hypothesize that Glyma.13G175300 is the putative ortholog of AtRAD51 in soybean because it is upregulated in meiosis (Supplemental Fig. S5A). No obvious sRNA association was observed for either of the RAD51 copies (Supplemental Fig. S5, A and B). In cucumber, we did observe sRNA accumulation on the putative CsRAD51 gene (CsaV3_1G041430), but there was no difference between leaf and meiocyte sRNA accumulation (Supplemental Fig. S5C). ASK1 belongs to a 23-family member protein family, with ASK1, ASK11, and ASK12 grouped together in one clade (Liu et al., 2004). No ASK counterpart from soybean was found in the same clade with ASK1. In cucumber, CsaV3_3G000620 and CsaV3_5G036070 are the two closest ASK1 homologs, but neither have any sRNA accumulation (Supplemental Fig. S5, D and E). Taken together, these results suggest that ms-sRNAs may share a role in meiotic gene regulation in Arabidopsis and soybean, but the specific genes they regulate may vary between species.

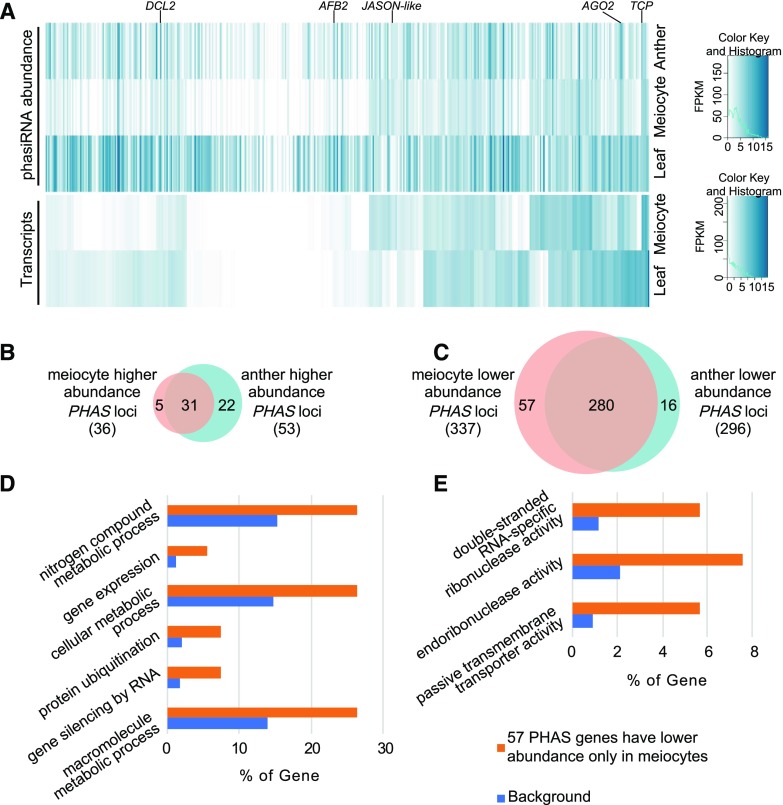

Phased siRNAs in Soybean Meiocytes

PhasiRNAs are a recently discovered class of regulatory RNAs in plants. They are 21–24-nt siRNAs, typically derived from coding regions, triggered by specific miRNAs (Fei et al., 2013). Although their biological role is still obscure, the biogenesis of 24-nt phasiRNAs are coincident with meiosis in angiosperms (Xia et al., 2019). In soybean, previous work identified 452 PHAS loci that overlap protein coding genes (Arikit et al., 2014). We analyzed the expression profile of sRNAs at these loci in soybean meiocytes, and found that 8% (36) of the PHAS loci have higher sRNA expression in meiocytes (>2-fold change in sRNA abundance normalized with fragments per kilobase of transcript per million mapped reads) compared to leaves (Fig. 7, A [the second to third rows] and B; Supplemental Dataset S9). Thirty-one out of 36 (86%) of those PHAS loci also have higher sRNA expression in anthers compared to leaves (Fig. 7B), whereas 5 (14%) have higher sRNA expression only in meiocytes (Fig. 7B). The latter are Glyma.19G251500 (encodes a Ser-type endopeptidase), Glyma.13G125900 (encodes a JASON-like protein, whose homolog in Arabidopsis plays a key role in meiosis II spindle morphology; Fig. 7A), Glyma.15G092500 (encodes a putative TCP family transcription factor), Glyma.20G152000 (encodes an exostosin family protein), and Glyma.03G242500 (its homolog in Arabidopsis encodes a bifunctional dehydroquinate-shikimate dehydrogenase enzyme that catalyzes two steps in the chorismate biosynthesis pathway; Mi et al., 2019). On the other hand, 74% (337) of the PHAS loci have lower sRNA expression in meiocytes compared to leaves (Fig. 7, A [the second to third rows] and C; Supplemental Dataset S9). Two-hundred and eighty of those 337 PHAS loci (83%) have lower sRNA expression in anthers; whereas 57 (17%) have lower sRNA expression only in meiocytes (Fig. 7C). This suggests that soybean meiocytes have similar PHAS gene expression patterns compared to anthers. GO enrichment analysis (Mi et al., 2019) of the 57 low-expression PHAS genes showed the nitrogen compound metabolic process (GO: 0006807, 14/66, P value = 4.9e-2), gene expression (GO: 0010467, 3/5, P value = 4.6e-2), the cellular metabolic process (GO: 0044237, 14/64, P value = 4.5e-2), protein ubiquitination (GO: 0016567, 4/9, P value = 4.3e-2), gene silencing by RNA (GO: 0031047, 4/8, P value = 3.2e-2), and the macromolecule metabolic process (GO: 0043170, 14/60, P value = 2.5e-2) from the GO category biological process (Fig. 7D); and double-stranded RNA-specific RNase activity (GO: 0032296, 3/5, P value = 4.6e-2), endoribonuclease activity (GO: 0004521, 4/9, P value = 4.3e-2), and passive transmembrane transporter activity (GO: 0022803, 3/4, P value = 3.1e-2) from GO category molecular function (Fig. 7E).

Figure 7.

Expression analysis of 452 PHAS genes and their phasiRNA abundance in soybean leaves, meiocytes, and anthers. A, Heatmap of 452 PHAS gene expression levels and phasiRNA abundance in soybean leaves, meiocytes, and anthers. (Right top) Color Key and Histogram is for the sRNA data; (right bottom) Color Key and Histogram is for the mRNA data. DCL2, DICER-LIKE 2, Glyma.09G025300; AFB2, AUXIN SIGNALING F-BOX 2, Glyma.19G100200; JASON-like, Glyma.13G125900; AGO2, Glyma.20G022900; TCP, a TCP transcription factor, Glyma.15G092500. B, Venn diagram shows that the majority of meiocyte higher abundance PHAS genes also show higher abundance in anthers compared to in leaves. C, Venn diagram shows that the majority of meiocyte lower abundance PHAS genes also show lower abundance in anthers compared to in leaves. D, GO term enrichment analysis of the 57 meiocyte-specific lower abundance PHAS genes in soybean from the biological process categories. E, GO term enrichment analysis of the 57 meiocyte-specific lower abundance PHAS genes in soybean from the molecular function categories.

Like classic siRNAs, phasiRNAs repress target transcripts at the posttranscriptional level (Fei et al., 2013). However, our data shows that ms-sRNA clusters, mainly comprised of 24-nt sRNAs in soybean, are positively associated with gene expression (Fig. 5). Based on these discordant observations we asked whether the 452 PHAS genes also have a positive correlation between phasiRNA abundance and gene expression in meiocytes. Among the 36 PHAS loci with higher phasiRNA abundance in meiocytes, 17 are upregulated in meiocytes compared to those in leaves (q value < 0.05, log2 [fold change] > 1), including Glyma.13G125900, a putative JASON-like gene, which maintains the spindle position during meiosis II (Brownfield et al., 2015; Fig. 7A; Supplemental Dataset S9); and two are downregulated (q value < 0.05, log2 [fold change] < −1; Fig. 7A, the fourth and fifth rows; Supplemental Dataset S9). Among the 337 PHAS loci with lower phasiRNA abundance in meiocytes, 30 are upregulated and 140 are downregulated including Glyma.19G100200, AUXIN SIGNALING F-BOX2 (Fig. 7A, the fourth and fifth rows; Supplemental Dataset S9). These results suggest that meiocyte phasiRNAs and ms-sRNAs have similar correlations with meiotic gene expression. However, these correlations are not always consistent. We also observed interesting PHAS loci, like Glyma.15G092500 (a putative TCP family transcription factor), which has higher phasiRNA abundance but lower mRNA transcript level in meiocytes. In contrast, Glyma.09G025300 (DICER-LIKE2) and Glyma.20G022900 (Ago2) have fewer sRNAs, but are upregulated during meiosis (Fig. 7A; Supplemental Dataset S9).

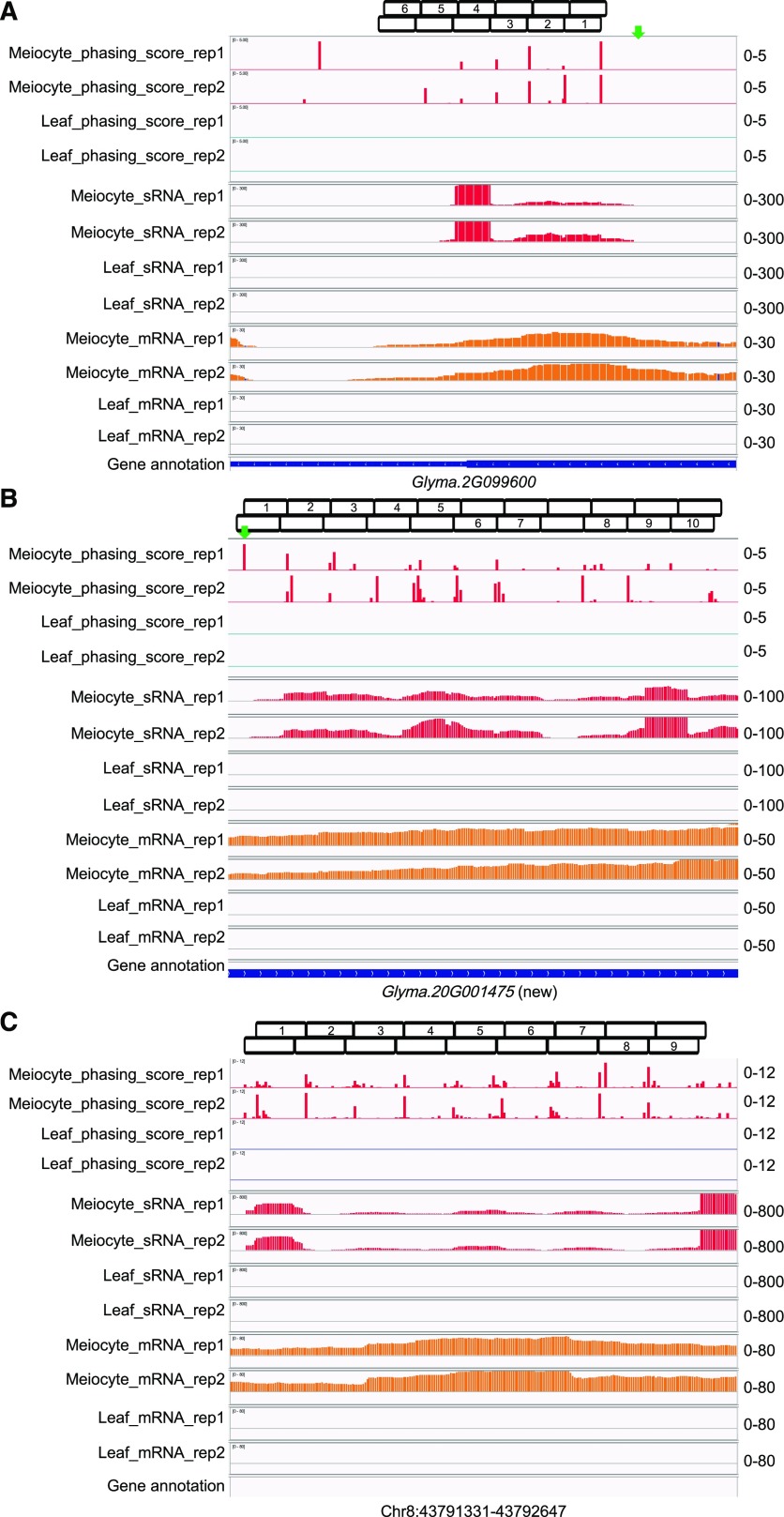

Arikit et al. (2014) previously reported 11 PHAS loci that are preferentially expressed in flower tissues including anthers. Two of these are also in our soybean meiocyte dataset (Fig. 8, A and B). Both loci produce 21-nt phasiRNAs, and are targets of the soybean- and anther-specific miR4392 (Arikit et al., 2014; Ding et al., 2019), which is also the second most abundant miRNA in soybean meiocytes (Supplemental Dataset S1). Notably, both PHAS genes were annotated as intergenic PHAS loci in the previous study (Arikit et al., 2014). One is now annotated as Glyma.2G099600 (Fig. 8A), whereas the other is yet to be annotated. Hence, we tentatively refer to this novel transcript as Glyma.20G001475 (Fig. 8B), because it is situated between Glyma.20G001400 and Glyma.20G001500. We also discovered a novel 24-nt phasiRNA locus at Chr8:43,791,331-43,792,647 that is expressed in meiocytes (Fig. 8C). We used the online tool psRNATarget (http://plantgrn.noble.org/psRNATarget/) to predict targets for the phasiRNA transcribed from these three loci. For the Glyma.2G099600 locus, six 21-nt phasiRNAs were retrieved (Fig. 8A) and the putative targets include a transcription factor (BHLH30, Glyma.02G100700) and a regulator of chromosome condensation (Glyma.10G226900). For Glyma.20G001475, ten 21-nt phasiRNAs were retrieved (Fig. 8B) and the putative targets include a transcription factor (TCP15, Glyma.05G027400), a kinase receptor (Glyma.20G200100), and a PPR protein (Glyma.10G213600). For Chr8 PHAS locus, nine 24-nt phasiRNAs were retrieved (Fig. 8C) and the putative targets include a DNA mismatch repair gene MLH3 (Glyma.11G086300) and a basic helix–loop–helix transcription factor (Glyma.03G240000; Supplemental Dataset S10).

Figure 8.

phasiRNA loci preferentially expressed in soybean meiocytes corresponding with meiocyte-specific transcripts. A, A 21-nt PHAS locus at Glyma.2G099600, which previously was designated as an intergenic PHAS locus. B, A 21-nt PHAS locus corresponds with a meiocyte-specific novel transcript now designated as Glyma.20G001475 (new), which previously was also annotated as an intergenic PHAS locus. C, A 24-nt novel PHAS locus discovered at Chr8: 43,791,331 to 43,792,647 with unconfident transcript. Green arrows in (A) and (B) represent the trigger sites by miR4392. Boxes on top of each screenshot show the phase of each locus. First and second rows of boxes indicate the phasiRNAs from sense and antisense strands, respectively. Numbers indicate the phasing order of phasiRNAs at each locus.

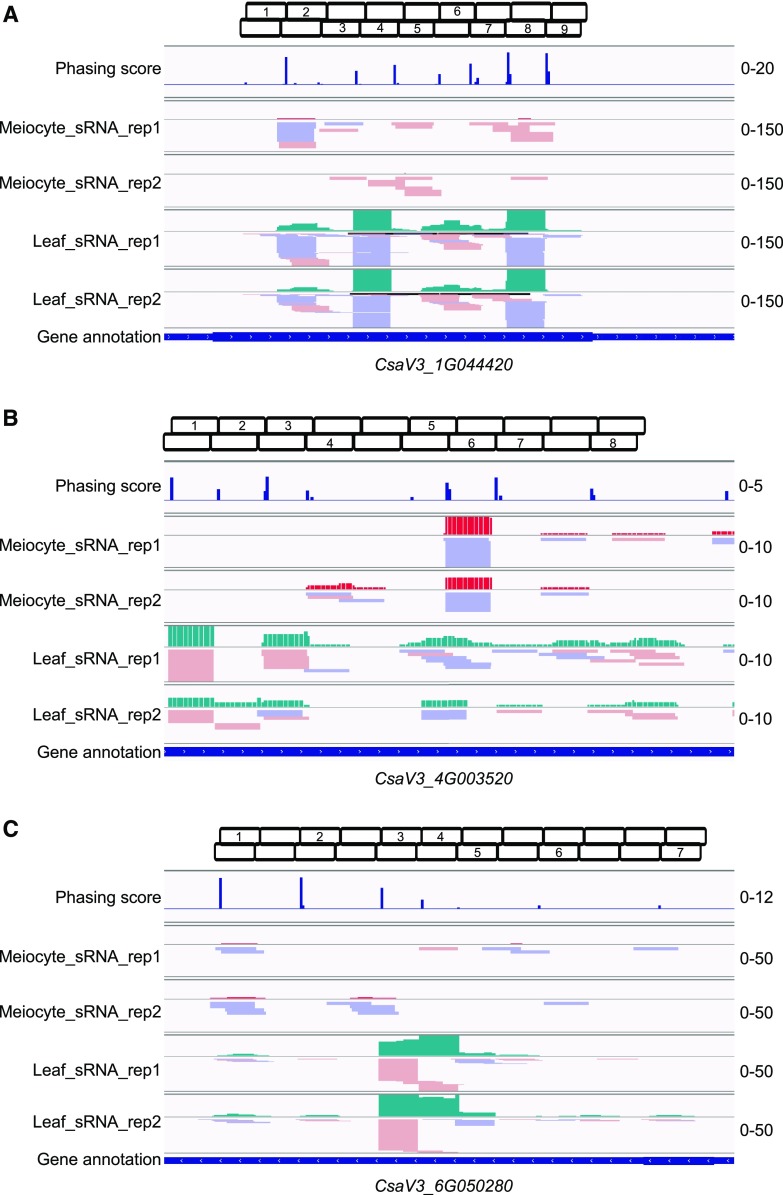

We also identified three PHAS genes from the cucumber genome (Fig. 9). CsaV3_1G044420 is the putative ortholog of Arabidopsis DICER LIKE2 (Fig. 9A), CsaV3_4G003520 encodes a RGA2-like disease resistance protein (Fig. 9B), and CsaV3_6G050280 is annotated as an Auxin-repressed gene (Fig. 9C). Target prediction for the phasiRNAs transcribed from the CsaV3_1G044420 locus, suggests phase-7 phasiRNA (Fig. 9A) targets a DNA mismatch repair MSH7 gene (CsaV3_2G002320), phase-8 phasiRNA (Fig. 9A) targets a MER3-like gene (CsaV3_5G027240), and all the phase-9 phasiRNAs target kinase genes (Fig. 9A; Supplemental Dataset S11). For the CsaV3_4G003520 locus, many meiosis- or DNA repair-related genes, like the BRCA1-associated gene (CsaV3_7G032060), MSH3 (CsaV3_3G017020), MSH7 (CsaV3_2G002320, the same target of phasiRNA from the previous locus CsaV3_1G044420), the DNA polymerase epsilon catalytic subunit (CsaV3_6G014890), the DNA primase large subunit (CsaV3_6G008170), RAD51B (CsaV3_6G021820), and MND1 (CsaV3_1G040040) are predicted as putative targets. For the CsaV3_6G050280 locus phasiRNAs, putative targets include chromatin structure-remodeling complex component SYD (CsaV3_3G014070), histone-Lys n-methyltransferase ATXR3 and ATXR4 (CsaV3_7G003880 and CsaV3_3G038540), and a CO junction endonuclease EME1B-like gene (CsaV3_6G042140; Supplemental Dataset S11). These results suggest a potential role for meiotic phasiRNAs in regulating processes related to meiosis and DNA repair or recombination in cucumber. However, all three PHAS loci have higher sRNA abundance in leaves than in meiocytes (Fig. 9), which is consistent with our findings in soybean that phasiRNAs are less active in meiocytes than in leaves (Fig. 7A).

Figure 9.

21-nt PHAS genes discovered in cucumber. A, A 21-nt PHAS locus at CsaV3_1G044420. B, A 21-nt PHAS locus at CsaV3_4G003520. C, A 21-nt PHAS locus at CsaV3_6G050280. Boxes on top of each screenshot show the phase of each locus. First and second rows of boxes indicate the phasiRNAs from sense and antisense strands, respectively. Numbers indicate the phasing order of phasiRNAs at each locus.

DISCUSSION

We surveyed miRNA profiles in soybean and cucumber, and then compared them to previously published profiles from Arabidopsis. Meiocytes have fewer miRNAs, which are expressed at a lower abundance compared to leaves (Fig. 2B; Supplemental Datasets S1–S3). This suggests a generalized downregulation of miRNA production during meiosis. During meiosis, chromosomes become increasingly condensed, which may obstruct transcription; in turn, this might lower the necessity for the miRNA machinery. This hypothesis is supported by a recent single-cell sequencing study in maize (Zea mays) meiocytes, which revealed a two-step transcriptome reorganization at early prophase before chromosome condensation (Nelms and Walbot, 2019). During this reorganization, there was downregulation of RNA-mediated translation and gene silencing processes, including those mediated by Ago18a, an AGO1 paralog specifically enriched in the tapetum and meiocytes during meiosis (Zhai et al., 2014). Interestingly, our findings differ from those in maize, in which meiocytes have a similar number of up- and downregulated miRNAs (Dukowic-Schulze et al., 2016). A possible explanation for this difference is the existence of the miRNA-triggered 24-nt phasiRNA pathway in monocots (Zhai et al., 2015). On the other hand, mutants of Arabidopsis miRNA-machinery genes have a relaxed meiotic chromatin conformation (Oliver et al., 2017), confirming a broad role for miRNAs in plant meiosis. Previous work in maize (Dukowic-Schulze et al., 2016) and sunflower (Helianthus annuus; Flórez-Zapata et al., 2016) meiocytes, and our results have revealed conserved miRNAs that are preferentially expressed in meiocytes, including miR390 and miR167 (Fig. 2, A–C), and the phasiRNA pathway-related soybean-specific miR4392 (Fig. 8, A and B). Nonetheless, the specific roles of these individual miRNAs in meiocytes require further study.

In Arabidopsis, the majority of ls-sRNA clusters map to TE regions (Huang et al., 2019). TEs have not been as robustly annotated in the soybean or cucumber genomes, which may explain why most sRNA clusters from our data map to intergenic regions (Fig. 3E). As TE annotation in these species improves, a reanalysis of their correlation with sRNA clusters will be valuable. Even with that caveat, our results show that ms-sRNAs in soybean are enriched at genic regions (Fig. 3E), and positively associated with genes that are transcriptionally upregulated in meiocytes (Fig. 5). These data are consistent with our prior observations in Arabidopsis meiocytes (Huang et al., 2019). Taken together, these data hint at a role for ms-sRNAs during meiosis that is shared across species boundaries. However, some of the trends we observed in Arabidopsis and soybean were not seen in cucumber. This may be because the cucumber genome has the least developed annotation, which raises the possibility that more conserved trends may emerge as its annotation improves.

The constitution of TE superfamilies is different in soybean and Arabidopsis: the top three TE superfamilies in soybean are Gypsy, Copia, and Mutator; whereas in Arabidopsis they are Helitron, Mutator, and Gypsy. Nonetheless, ms-sRNAs from both species are enriched at Helitrons, a DNA transposon group that has been reported to overlap DSB hotspots (Choi et al., 2018). Similarly, ms-sRNAs appear to be depleted (although not significantly) at Copia elements, a RNA transposon group that has been reported to have significantly less association with DSB hotspots (Choi et al., 2018). This might suggest a relation between sRNAs and TE-associated DSB hotspots in meiocytes. GO enrichment analysis of ms-RNA–associated upregulated genes also reveals commonalities between soybean and Arabidopsis, like translation (GO: 0006412) and DNA packaging complex (GO: 0044815) functions (Fig. 6). Intriguingly, meiosis-related GO terms like developmental process involved in reproduction (GO: 0003006) and sexual reproduction (GO: 0019953) are enriched specifically in soybean meiocytes (Fig. 6A), suggesting possible differences between the two species that diverged ∼90 million years ago (Grant et al., 2000). However, we failed to observe any specific, essential meiotic genes that have conserved ms-RNA association among Arabidopsis, soybean, and cucumber. This suggests that ms-sRNAs function in broad biological pathways in plant meiosis, but that individual genes are likely to vary in their specific regulatory mechanisms.

PhasiRNA analysis in maize meiocytes reported comparable sRNA abundance in meiocytes and anthers (Dukowic-Schulze et al., 2016). However, our analysis of the previously reported 452 PHAS genes in soybean showed that 37% (169) had lower expression in meiocytes compared to leaves and anthers (Fig. 7A, the first to third rows; Supplemental Dataset S9). This observation is consistent with 19 out of 20 known phasiRNA-triggering miRNAs in soybean (Arikit et al., 2014), which are less abundant in meiocytes than in leaves (Supplemental Dataset S1), indicating that phasiRNAs might not be as prolific as in maize meiocytes. This may be due to the apparent lack of the miR2275/24-nt phasiRNA pathway in soybean (Zhai et al., 2015). Another possibility is that the prior results were based on analysis of anther tissue, which contains multiple cell types, including meiocytes and tapetum. The analysis in maize and rice suggested that 24-nt phasiRNAs, which are produced in tapetum, are also found in meiotic cells (Nonomura et al., 2007; Zhai et al., 2015). Therefore, it is possible that the tapetum is the main source for miRNA-triggered phasiRNAs, which may be imported into meiocytes to regulate gene expression. This would also explain why nine of the 11 previously reported PHAS loci preferentially expressed in soybean flower tissues (Arikit et al., 2014) were not identified in our soybean meiocyte data. The increasing ease of single-cell sequencing might help to resolve this question.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plant Materials

Soybean (Glycine max ‘Huaxia3’) plants (Wang et al., 2014a) were grown for 55 d in a greenhouse, with a 12-h light/12-h dark photoperiod at 25°C. Cucumber (Cucumis sativus ‘Xintaimici’) plants were grown for 45 d in a greenhouse, with 12-h light/12-h dark photoperiod at 25°C/20°C.

Soybean and Cucumber Meiocytes Collections, RNA Extraction, sRNA-Seq, and RNA-Seq

The method for isolating meiocytes from soybean and cucumber is similar to that of Arabidopsis (Wang et al., 2014b; Huang et al., 2019). Staging experiments showed that 2–4-mm flower buds of soybean or cucumber (staminate flower) contain meiocytes from every stage (Supplemental Figs. S1 and S2). Suitable flower buds were placed onto a clean double depression slide. Thirty to 40 anthers undergoing meiosis were dissected in one cavity with 10-μL RNase-free water containing Recombinant RNase inhibitor (2U/μL; Takara). Meiocyte masses were released using forceps and collected in the microchamber of a micromanipulator (Wang et al., 2014b). To verify that meiosis was ongoing in these cell masses, chromosome spreading (Supplemental Figs. S1 and S2) was performed as follows: The fresh collected meiocyte masses were fixed in Carnoy’s fixative solution with ethanol/acetic acid (3:1) for 1 h at room temperature and digested with enzyme mixture of 5% (w/v) cytohelicase (C8274; Sigma-Aldrich), 3% cellulose (F0250; Yakult), and 3% macerozyme (L0021; Yakult) in 10 mm of citrate buffer (pH 4.5) for 5 min at 37°C; then steps were followed as described in Wang et al. (2014b). Thirty to 50 meiocyte masses were collected per slide, transferred to an RNase-free 2.0-mL tube containing 2-mm beads (Zymo Research), and immediately placed in liquid nitrogen. Approximately 200 meiocyte masses are sufficient to extract RNA for one sample. Soybean leaf samples were collected from 4-week–old seedlings during the light period after lights were turned on for 4 h. Total RNA was extracted by Trizol (Thermo Fisher Scientific) following the standard protocol with the exception that samples were frozen in liquid nitrogen and thawed in a 37°C water bath at least four times for better homogeneity. The aqueous phase was transferred into a new tube and 4-μL Dr. GenTLE Precipitation Carrier (Takara) per 400-μL volume was added. sRNA libraries were constructed using the TruSeq Small RNA Library Preparation Kit (Illumina) all starting with 1-μg total RNA. sRNA sequencing was performed via Hiseq 2000 (Illumina) with at least 20 million 1×50 single-end reads for each sample. RNA-seq libraries were constructed using a TruSeq RNA Library Preparation Kit (Illumina) all starting with 1-μg total RNA. Sequencing was performed via Hiseq 2000/3000 (Illumina) with at least 20 million 2×100 pair-end reads for each sample.

Computational Analysis of Sequencing Data

Raw sequencing data were trimmed using the program BBMap (v38.46, Bushnell B.; sourceforge.net/projects/bbmap/) to remove adapters and low-quality reads. Preprocessed data were mapped using the software BowTie (1.2.2; Langmead et al., 2009) to the soybean genome (Department of Energy-Joint Genome Institute [DOE-JGI] Community Sequencing Program 2.1, downloaded from EnsemblPlants [http://plants.ensembl.org/index.html]) or the cucumber genome (Cucumber Chinese Long v3 Genome; http://cucurbitgenomics.org/organism/20) with perfect match to get total mappable reads. tsRNAs or rsRNAs were defined as mappable reads that perfectly matched tRNAs or ribosomal RNAs from each species, respectively. Soybean and Arabidopsis tRNAs were downloaded from GtRNAdb (http://gtrnadb.ucsc.edu/index.html). Cucumber tRNAs and ribosomal RNAs were collected from the Rfam database (Nawrocki et al., 2015). Known soybean and Arabidopsis miRNAs were defined as mappable reads that perfectly matched soybean and Arabidopsis mature miRNAs from the miRbase (v22.1; http://www.mirbase.org), respectively. Cucumber miRNAs were reads that perfectly matched to the plant mature miRNAs in miRbase by the software BowTie (1.2.2; Langmead et al., 2009). miRNAs and sRNAs from each sample were normalized with reads mapped onto ribosomal RNAs; rsRNAs and tsRNAs were normalized with total mapped reads. Names for newly identified cucumber miRNAs are consistent with prior literature standards (Ma et al., 2018). Preferential expression of miRNAs in meiocytes is defined as miRNAs that have more than four times higher abundance in meiocyte than that in leaves. The “other” sRNAs were the genome-mapped sRNAs remaining after filtering all reads identical to known miRNAs, small nucleolar RNAs, small nuclear RNAs and the other annotated RNAs listed in the Rfam database (Nawrocki et al., 2015). sRNA clusters from other sRNAs were obtained using the program ShortStack 3.8.4 (https://github.com/MikeAxtell/ShortStack) with the option “-mincov 1rpm -pad 75” and “0 mismatch” (Johnson et al., 2016). Only ≥3 rpm clusters were retained. To generate comparable results with previously reported Arabidopsis data (Huang et al., 2019), both 23- and 24-nt sRNAs were included in the beginning of sRNA cluster searching. Data correlations were calculated from BAM files using “multiBamSummary” in the software deepTools 2.5.2 (Ramírez et al., 2016).

miRNA and miRNA Target Gene Prediction

Novel miRNAs in meiocytes were predicted by the software ShortStack v3.8.4 (Johnson et al., 2016), and then using the tool BLAST against the mature miRNA dataset from the software miRbase (v22.1; http://www.mirbase.org) to filter out annotated candidates. Valid miRNA and miRNA loci that meet the criteria suggested by Axtell and Meyers (2018) were retained. Briefly, a valid miRNA locus for a 21–22-nt miRNA should have only one miRNA:miRNA* duplex, no secondary stems or large loops within the duplex, <300-nt foldback size, fewer than five mismatched positions within miRNA:miRNA*, >75% of the total reads on the locus coming from miRNA or miRNA*; and be validated in at least two biological replicates. Putative miRNA locus secondary structures were plotted by the program strucVis (https://github.com/MikeAxtell/strucVis). Novel miRNA target gene prediction was performed using an online tool, psRNATarget, against the complementary DNA library Cucumber Chinese Long v3 with default setting (Dai et al., 2018).

Association of sRNA Clusters with Genomic Features

Genomic feature annotations of soybean and cucumber were determined from gff3 files downloaded from the EnsemblPlants database (http://plants.ensembl.org/index.html): Glycine_max.Glycine_max_v2.1.43.gff3 and Cucumis_sativus.ASM407v2.43.chr.gff3. Introns were added by the program GenomeTools 1.5.9 (Gremme et al., 2013) with the command “gt gff3 -sort yes -addintrons yes”. Promoter regions were designated arbitrarily as 1,500 bp ahead of 5′ UTRs. Undefined regions between two genomic features were designated as intergenic regions. All features and inquiry sRNA clusters were converted to FASTA files. Genomic feature occupancy was then determined by BLASTn v2.9.0 (Camacho et al., 2009) with “blastn -task blastn -evalue 0.01 -outfmt “6””. The 38,581 annotated TEs sequences in soybean were downloaded from SoyTE (https://www.soybase.org/soytedb/; Du et al., 2010). TE-associated sRNA clusters were obtained by “blastn -task blastn -evalue 0.01 -outfmt “6””. Only clusters that have 100 “identical matches” were retained.

Gene Expression Analysis and GO Analysis

The mRNA-seq samples were the same samples used for sRNA-seq. RNA-seq libraries were constructed using a TruSeq RNA Library Preparation Kit (Illumina) with 1 μg of total RNA. Sequencing was performed via Hiseq 2000/3000 (Illumina) with at least 20 million of 2×100 pair-end reads for each sample. Adapter trimming was conducted using the program BBMap (v38.46, Bushnell B.; sourceforge.net/projects/bbmap/). The whole genome sequence and annotation were performed with DOE-JGI Community Sequencing Program 2.1. Clean reads were mapped using the software TopHat2 (Trapnell et al., 2012). Differential gene expression analysis was conducted using the program Cufflinks 2.2.1 (Trapnell et al., 2012) with the criteria of log2 fold change ≥ 1 or ≤ −1, q value ≤ 0.05. Expressed genes were defined with at least three reads detected from meiocytes and leaves, respectively. GO analysis was performed by the tool PANTHER (http://www.pantherdb.org; Mi et al., 2019). Illustrations of the sRNA and gene loci were plotted using the software IGV (2.5.0, https://software.broadinstitute.org/software/igv/node/294).

PhasiRNA Analysis

The latest soybean annotation (DOE-JGI Community Sequencing Program v2.1) was used, and the 452 PHAS loci examined in this include the 438 previously identified loci (Arikit et al., 2014). Two soybean meiocyte sRNA datasets were combined for 21- and 24-nt PHAS locus prediction in soybean meiocytes. The four cucumber sRNA datasets used in this study were combined for 21- and 24-nt PHAS locus prediction in cucumber. The nonredundant 21–24-nt sRNAs were mapped to their genomes to remove all reads identical to known miRNAs, small nucleolar RNAs, small nuclear RNAs, and the other annotated RNAs listed in the Rfam database (Nawrocki et al., 2015), and also mapped to the tool Repbase (24.05; Bao et al., 2015) to remove repetitive sequences. Then, the remaining sRNAs were mapped to the soybean and cucumber genomes, respectively, with the software BowTie (1.2.2; Langmead et al., 2009). To increase prediction accuracy, PHAS loci were predicted following an algorithm from the work of Xia et al. (2013) with phasing P value ≤ 0.001, as well as having a ≥30-PhaseScore value predicted by the software ShortStack 3.8.4 (Johnson et al., 2016). Each locus was graphed and visually checked eventually. Plotted phasing scores were first calculated according to the method of Chen et al. (2007), then plotted using the software IGV.

Accession Numbers

The high-throughput sequencing data were deposited at the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) Sequence Read Archive (SRA) under accession numbers PRJNA550139 and PRJNA510650. The soybean leaf sRNA data SRR1451648 and SRR1451649, and soybean anther sRNA data SRR1451604 and SRR1451605 were retrieved from the study of Arikit et al. (2014) and deposited in NCBI SRA. The cucumber leaf sRNA data SRR2045887and SRR2045888 were retrieved from the work of Savory et al. (2012) and deposited in NCBI SRA. More detailed information is presented in Supplemental Table S1.

Accession numbers of the major genes mentioned in this article are AtMIR390B (At2G38325), AtRAD51 (AT5G20850), ASK1 (AT1G75950), GlPRD3 (Glyma.07G070400), GlCENH3 (Glyma.07G057300), GlAGO4 (Glyma.02G274900), GlSGS3 (Glyma.04G203600), GlRAD51a (Glyma.13G175300), GlRAD51b (Glyma.17G049800), GlDCL2 (Glyma.09G025300), GlAGO2 (Glyma.20G022900), JASON-like (Glyma.13G125900), AFB2 (Glyma.19G100200), TCP (Glyma.15G092500), BHLH30 (Glyma.02G100700), regulator of chromosome condensation1 (Glyma.10G226900), TCP15 (Glyma.05G027400), PPR protein (Glyma.10G213600), GlMLH3 (Glyma.11G086300), Glyma.03G240000, Glyma.20G200100, a Ser-type endopeptidase encoding gene (Glyma.19G251500), an exostosin family gene (Glyma.20G152000), a bifunctional dehydroquinate-shikimate dehydrogenase gene (Glyma.03G242500), Glyma.2G099600, CsPRD3 (CsaV3_3G008890), CsCENH3 (CsaV3_7G025320), CsAGO4 (CsaV3_4G017350), CsSGS3 (CsaV3_2G019630), CsRAD51 (CsaV3_1G041430), CsASK1a (CsaV3_3G000620), CsASK1b (CsaV3_5G036070), CsDCL2 (CsaV3_1G044420), RGA2-like (CsaV3_4G003520), CsMSH7 (CsaV3_2G002320), MER3-like (CsaV3_5G027240), CsMSH3 (CsaV3_3G017020), CsRAD51B (CsaV3_6G021820), CsMND1 (CsaV3_1G040040), CsSYD (CsaV3_3G014070), CsATXR3 (CsaV3_7G003880), CsATXR4 (CsaV3_3G038540), EME1B-like (CsaV3_6G042140), CsaV3_7G032060, CsaV3_6G050280, CsaV3_6G014890, CsaV3_6G014620, CsaV3_2G004460, CsaV3_2G010350, CsaV3_3G008450, CsaV3_5G035780, and CsaV3_6G008170.

Supplemental Data

The following supplemental materials are available.

Supplemental Figure S1. DAPI-stained chromosome spreads from soybean male meiocytes.

Supplemental Figure S2. DAPI-stained chromosome spreads from cucumber male meiocytes.

Supplemental Figure S3. Size distribution of rsRNAs and tsRNAs in soybean, cucumber, and Arabidopsis.

Supplemental Figure S4. sRNA distribution around PRD3, CENH3, AGO4, and SGS3 homologs in cucumber.

Supplemental Figure S5. sRNA distribution around RAD51 and ASK1 homologs in soybean and cucumber.

Supplemental Table S1. sRNA-seq data statistics.

Supplemental Table S2. Pearson correlation analyses of soybean sRNA-seq, cucumber sRNA-seq, and soybean mRNA-seq samples.

Supplemental Table S3. Soybean mRNA-seq data statistics.

Supplemental Dataset S1. Evaluation of annotated soybean miRNAs in meiocytes and leaves.

Supplemental Dataset S2. Evaluation of annotated Arabidopsis miRNAs in meiocytes and leaves.

Supplemental Dataset S3. Putative conserved cucumber miRNAs in meiocytes and leaves.

Supplemental Dataset S4. Predicted targets of three novel miRNAs in cucumber.

Supplemental Dataset S5. GO analysis of predicted miR11345 targeting genes.

Supplemental Dataset S6. Enriched GO biological processes from 450 ms-RNA–associated upregulated genes in soybean meiocytes.

Supplemental Dataset S7. Enriched GO molecular functions from 450 ms-RNA–associated upregulated genes in soybean meiocytes.

Supplemental Dataset S8. Enriched GO cellular components from 450 ms-RNA–associated upregulated genes in soybean meiocytes.

Supplemental Dataset S9. sRNA abundance of previously reported 452 PHAS genes normalized in fragments per kilobase of transcript per million mapped reads among leaves, anthers, and meiocytes.

Supplemental Dataset S10. Predicted targets of phasiRNAs from three soybean meiosis PHAS loci.

Supplemental Dataset S11. Predicted targets of phasiRNAs from three cucumber meiosis PHAS loci.

Acknowledgments

We sincerely thank Dr. Rui Xia from the State Key Laboratory for Conservation and Utilization of Subtropical Agro-Bioresources, South China Agricultural University for providing us the script for the phasing analysis.

Footnotes

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31570314, 31870293, and 31600246), the United States National Science Foundation (IOS-1844264), Fudan University, and the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Articles can be viewed without a subscription.

References

- Arikit S, Xia R, Kakrana A, Huang K, Zhai J, Yan Z, Valdés-López O, Prince S, Musket TA, Nguyen HT, et al. (2014) An atlas of soybean small RNAs identifies phased siRNAs from hundreds of coding genes. Plant Cell 26: 4584–4601 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Axtell MJ. (2013) Classification and comparison of small RNAs from plants. Annu Rev Plant Biol 64: 137–159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Axtell MJ, Meyers BC (2018) Revisiting criteria for plant microRNA annotation in the era of big data. Plant Cell 30: 272–284 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bao W, Kojima KK, Kohany O (2015) Repbase Update, a database of repetitive elements in eukaryotic genomes. Mob DNA 6: 11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baudat F, Buard J, Grey C, Fledel-Alon A, Ober C, Przeworski M, Coop G, de Massy B (2010) PRDM9 is a major determinant of meiotic recombination hotspots in humans and mice. Science 327: 836–840 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonath F, Domingo-Prim J, Tarbier M, Friedländer MR, Visa N (2018) Next-generation sequencing reveals two populations of damage-induced small RNAs at endogenous DNA double-strand breaks. Nucleic Acids Res 46: 11869–11882 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borde V, Robine N, Lin W, Bonfils S, Géli V, Nicolas A (2009) Histone H3 lysine 4 trimethylation marks meiotic recombination initiation sites. EMBO J 28: 99–111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borges F, Martienssen RA (2015) The expanding world of small RNAs in plants. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 16: 727–741 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borges F, Pereira PA, Slotkin RK, Martienssen RA, Becker JD (2011) MicroRNA activity in the Arabidopsis male germline. J Exp Bot 62: 1611–1620 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brownfield L, Yi J, Jiang H, Minina EA, Twell D, Köhler C (2015) Organelles maintain spindle position in plant meiosis. Nat Commun 6: 6492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camacho C, Coulouris G, Avagyan V, Ma N, Papadopoulos J, Bealer K, Madden TL (2009) BLAST+: Architecture and applications. BMC Bioinformatics 10: 421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen HM, Li YH, Wu SH (2007) Bioinformatic prediction and experimental validation of a microRNA-directed tandem trans-acting siRNA cascade in Arabidopsis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 104: 3318–3323 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Q, Yan M, Cao Z, Li X, Zhang Y, Shi J, Feng GH, Peng H, Zhang X, Zhang Y, et al. (2016) Sperm tsRNAs contribute to intergenerational inheritance of an acquired metabolic disorder. Science 351: 397–400 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi K, Zhao X, Kelly KA, Venn O, Higgins JD, Yelina NE, Hardcastle TJ, Ziolkowski PA, Copenhaver GP, Franklin FC, et al. (2013) Arabidopsis meiotic crossover hot spots overlap with H2A.Z nucleosomes at gene promoters. Nat Genet 45: 1327–1336 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi K, Zhao X, Tock AJ, Lambing C, Underwood CJ, Hardcastle TJ, Serra H, Kim J, Cho HS, Kim J, et al. (2018) Nucleosomes and DNA methylation shape meiotic DSB frequency in Arabidopsis thaliana transposons and gene regulatory regions. Genome Res 28: 532–546 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu C, Yu L, Wu B, Ma L, Gou LT, He M, Guo Y, Li ZT, Gao W, Shi H, et al. (2017) A sequence of 28S rRNA-derived small RNAs is enriched in mature sperm and various somatic tissues and possibly associates with inflammation. J Mol Cell Biol 9: 256–259 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conine CC, Sun F, Song L, Rivera-Perez JA, Rando OJ (2018) Small RNAs gained during epididymal transit of sperm are essential for embryonic development in mice. Dev Cell 46: 470–480 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Alessandro G, Whelan DR, Howard SM, Vitelli V, Renaudin X, Adamowicz M, Iannelli F, Jones-Weinert CW, Lee M, Matti V, et al. (2018) BRCA2 controls DNA:RNA hybrid level at DSBs by mediating RNase H2 recruitment. Nat Commun 9: 5376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dai X, Zhuang Z, Zhao PX (2018) psRNATarget: A plant small RNA target analysis server (2017 release). Nucleic Acids Res 46: W49–W54 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Muyt A, Pereira L, Vezon D, Chelysheva L, Gendrot G, Chambon A, Lainé-Choinard S, Pelletier G, Mercier R, Nogué F, et al. (2009) A high throughput genetic screen identifies new early meiotic recombination functions in Arabidopsis thaliana. PLoS Genet 5: e1000654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding X, Zhang H, Ruan H, Li Y, Chen L, Wang T, Jin L, Li X, Yang S, Gai J (2019) Exploration of miRNA-mediated fertility regulation network of cytoplasmic male sterility during flower bud development in soybean. 3 Biotech 9: 22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du J, Grant D, Tian Z, Nelson RT, Zhu L, Shoemaker RC, Ma J (2010) SoyTEdb: A comprehensive database of transposable elements in the soybean genome. BMC Genomics 11: 113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dukowic-Schulze S, Sundararajan A, Ramaraj T, Kianian S, Pawlowski WP, Mudge J, Chen C (2016) Novel meiotic miRNAs and indications for a role of phasiRNAs in meiosis. Front Plant Sci 7: 762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fahlgren N, Montgomery TA, Howell MD, Allen E, Dvorak SK, Alexander AL, Carrington JC (2006) Regulation of AUXIN RESPONSE FACTOR3 by TAS3 ta-siRNA affects developmental timing and patterning in Arabidopsis. Curr Biol 16: 939–944 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fei Q, Xia R, Meyers BC (2013) Phased, secondary, small interfering RNAs in posttranscriptional regulatory networks. Plant Cell 25: 2400–2415 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flórez-Zapata NM, Reyes-Valdés MH, Martínez O (2016) Long non-coding RNAs are major contributors to transcriptome changes in sunflower meiocytes with different recombination rates. BMC Genomics 17: 490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Francia S, Michelini F, Saxena A, Tang D, de Hoon M, Anelli V, Mione M, Carninci P, d’Adda di Fagagna F (2012) Site-specific DICER and DROSHA RNA products control the DNA-damage response. Nature 488: 231–235 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gebetsberger J, Wyss L, Mleczko AM, Reuther J, Polacek N (2017) A tRNA-derived fragment competes with mRNA for ribosome binding and regulates translation during stress. RNA Biol 14: 1364–1373 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant D, Cregan P, Shoemaker RC (2000) Genome organization in dicots: Genome duplication in Arabidopsis and synteny between soybean and Arabidopsis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 97: 4168–4173 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gremme G, Steinbiss S, Kurtz S (2013) GenomeTools: A comprehensive software library for efficient processing of structured genome annotations. IEEE/ACM Trans Comput Biol Bioinform 10: 645–656 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Group TAP, Chase MW, Christenhusz MJM, Fay MF, Byng JW, Judd WS, Soltis DE, Mabberley DJ, Sennikov AN, Soltis PS, et al. (2016) An update of the Angiosperm Phylogeny Group classification for the orders and families of flowering plants: APG IV. Bot J Linn Soc 181: 1–20 [Google Scholar]

- Huang J, Wang C, Wang H, Lu P, Zheng B, Ma H, Copenhaver GP, Wang Y (2019) Meiocyte-specific and AtSPO11-1-dependent small RNAs and their association with meiotic gene expression and recombination. Plant Cell 31: 444–464 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunter N. (2015) Meiotic recombination: The essence of heredity. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 7: 7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson NR, Yeoh JM, Coruh C, Axtell MJ (2016) Improved placement of multi-mapping small RNAs. G3 (Bethesda) 6: 2103–2111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawai S, Amano A (2012) BRCA1 regulates microRNA biogenesis via the DROSHA microprocessor complex. J Cell Biol 197: 201–208 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim HK, Fuchs G, Wang S, Wei W, Zhang Y, Park H, Roy-Chaudhuri B, Li P, Xu J, Chu K, et al. (2017) A transfer-RNA-derived small RNA regulates ribosome biogenesis. Nature 552: 57–62 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langmead B, Trapnell C, Pop M, Salzberg SL (2009) Ultrafast and memory-efficient alignment of short DNA sequences to the human genome. Genome Biol 10: R25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu F, Ni W, Griffith ME, Huang Z, Chang C, Peng W, Ma H, Xie D (2004) The ASK1 and ASK2 genes are essential for Arabidopsis early development. Plant Cell 16: 5–20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma C, Yang J, Cheng Q, Mao A, Zhang J, Wang S, Weng Y, Wen C (2018) Comparative analysis of miRNA and mRNA abundance in determinate cucumber by high-throughput sequencing. PLoS One 13: e0190691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma H. (2006) A molecular portrait of Arabidopsis meiosis. Arabidopsis Book 4: e0095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mi H, Muruganujan A, Ebert D, Huang X, Thomas PD (2019) PANTHER version 14: More genomes, a new PANTHER GO-slim and improvements in enrichment analysis tools. Nucleic Acids Res 47(D1): D419–D426 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michalik KM, Böttcher R, Förstemann K (2012) A small RNA response at DNA ends in Drosophila. Nucleic Acids Res 40: 9596–9603 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michelini F, Pitchiaya S, Vitelli V, Sharma S, Gioia U, Pessina F, Cabrini M, Wang Y, Capozzo I, Iannelli F, et al. (2017) Damage-induced lncRNAs control the DNA damage response through interaction with DDRNAs at individual double-strand breaks. Nat Cell Biol 19: 1400–1411 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montgomery TA, Howell MD, Cuperus JT, Li D, Hansen JE, Alexander AL, Chapman EJ, Fahlgren N, Allen E, Carrington JC (2008) Specificity of ARGONAUTE7-miR390 interaction and dual functionality in TAS3 trans-acting siRNA formation. Cell 133: 128–141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nawrocki EP, Burge SW, Bateman A, Daub J, Eberhardt RY, Eddy SR, Floden EW, Gardner PP, Jones TA, Tate J, et al. (2015) Rfam 12.0: Updates to the RNA families database. Nucleic Acids Res 43: D130–D137 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelms B, Walbot V (2019) Defining the developmental program leading to meiosis in maize. Science 364: 52–56 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nonomura K, Morohoshi A, Nakano M, Eiguchi M, Miyao A, Hirochika H, Kurata N (2007) A germ cell specific gene of the ARGONAUTE family is essential for the progression of premeiotic mitosis and meiosis during sporogenesis in rice. Plant Cell 19: 2583–2594 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliver C, Pradillo M, Jover-Gil S, Cuñado N, Ponce MR, Santos JL (2017) Loss of function of Arabidopsis microRNA-machinery genes impairs fertility, and has effects on homologous recombination and meiotic chromatin dynamics. Sci Rep 7: 9280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Onodera Y, Haag JR, Ream T, Costa Nunes P, Pontes O, Pikaard CS (2005) Plant nuclear RNA polymerase IV mediates siRNA and DNA methylation-dependent heterochromatin formation. Cell 120: 613–622 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osman K, Higgins JD, Sanchez-Moran E, Armstrong SJ, Franklin FC (2011) Pathways to meiotic recombination in Arabidopsis thaliana. New Phytol 190: 523–544 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan J, Sasaki M, Kniewel R, Murakami H, Blitzblau HG, Tischfield SE, Zhu X, Neale MJ, Jasin M, Socci ND, et al. (2011) A hierarchical combination of factors shapes the genome-wide topography of yeast meiotic recombination initiation. Cell 144: 719–731 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peragine A, Yoshikawa M, Wu G, Albrecht HL, Poethig RS (2004) SGS3 and SGS2/SDE1/RDR6 are required for juvenile development and the production of trans-acting siRNAs in Arabidopsis. Genes Dev 18: 2368–2379 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramírez F, Ryan DP, Grüning B, Bhardwaj V, Kilpert F, Richter AS, Heyne S, Dündar F, Manke T (2016) deepTools2: A next generation web server for deep-sequencing data analysis. Nucleic Acids Res 44(W1): W160–W165 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ravi M, Shibata F, Ramahi JS, Nagaki K, Chen C, Murata M, Chan SW (2011) Meiosis-specific loading of the centromere-specific histone CENH3 in Arabidopsis thaliana. PLoS Genet 7: e1002121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers K, Chen X (2013) Biogenesis, turnover, and mode of action of plant microRNAs. Plant Cell 25: 2383–2399 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savory EA, Adhikari BN, Hamilton JP, Vaillancourt B, Buell CR, Day B (2012) mRNA-seq analysis of the Pseudoperonospora cubensis transcriptome during cucumber (Cucumis sativus L.) infection. PLoS One 7: e35796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trapnell C, Roberts A, Goff L, Pertea G, Kim D, Kelley DR, Pimentel H, Salzberg SL, Rinn JL, Pachter L (2012) Differential gene and transcript expression analysis of RNA-seq experiments with TopHat and Cufflinks. Nat Protoc 7: 562–578 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Underwood CJ, Choi K, Lambing C, Zhao X, Serra H, Borges F, Simorowski J, Ernst E, Jacob Y, Henderson IR, et al. (2018) Epigenetic activation of meiotic recombination near Arabidopsis thaliana centromeres via loss of H3K9me2 and non-CG DNA methylation. Genome Res 28: 519–531 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L, Cao C, Ma Q, Zeng Q, Wang H, Cheng Z, Zhu G, Qi J, Ma H, Nian H, et al. (2014a) RNA-seq analyses of multiple meristems of soybean: Novel and alternative transcripts, evolutionary and functional implications. BMC Plant Biol 14: 169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Cheng Z, Lu P, Timofejeva L, Ma H (2014b) Molecular cell biology of male meiotic chromosomes and isolation of male meiocytes in Arabidopsis thaliana. Methods Mol Biol 1110: 217–230 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Copenhaver GP (2018) Meiotic recombination: Mixing it up in plants. Annu Rev Plant Biol 69: 577–609 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei W, Ba Z, Gao M, Wu Y, Ma Y, Amiard S, White CI, Rendtlew Danielsen JM, Yang YG, Qi Y (2012) A role for small RNAs in DNA double-strand break repair. Cell 149: 101–112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu MF, Tian Q, Reed JW (2006) Arabidopsis microRNA167 controls patterns of ARF6 and ARF8 expression, and regulates both female and male reproduction. Development 133: 4211–4218 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xia R, Chen C, Pokhrel S, Ma W, Huang K, Patel P, Wang F, Xu J, Liu Z, Li J, et al. (2019) 24-nt reproductive phasiRNAs are broadly present in angiosperms. Nat Commun 10: 627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xia R, Meyers BC, Liu Z, Beers EP, Ye S, Liu Z (2013) MicroRNA superfamilies descended from miR390 and their roles in secondary small interfering RNA Biogenesis in eudicots. Plant Cell 25: 1555–1572 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamada S, Kugou K, Ding DQ, Fujita Y, Hiraoka Y, Murakami H, Ohta K, Yamada T (2018) The histone variant H2A.Z promotes initiation of meiotic recombination in fission yeast. Nucleic Acids Res 46: 609–620 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yelina NE, Choi K, Chelysheva L, Macaulay M, de Snoo B, Wijnker E, Miller N, Drouaud J, Grelon M, Copenhaver GP, et al. (2012) Epigenetic remodeling of meiotic crossover frequency in Arabidopsis thaliana DNA methyltransferase mutants. PLoS Genet 8: e1002844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yelina NE, Lambing C, Hardcastle TJ, Zhao X, Santos B, Henderson IR (2015) DNA methylation epigenetically silences crossover hot spots and controls chromosomal domains of meiotic recombination in Arabidopsis. Genes Dev 29: 2183–2202 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]