Abstract

Background

Delayed cord clamping or cord milking improves cardiovascular stability and outcome of preterm infants. However, both techniques may delay initiation of respiratory support. To allow lung aeration during cord blood transfusion, we implemented an extrauterine placental transfusion (EPT) approach. This study aimed to provide a detailed description of the EPT procedure and to evaluate its impact on the outcome of infants.

Methods

A retrospective analysis was performed comprising 60 preterm infants (220/7 to 316/7 weeks of gestation). Of these, 40 were transferred to the resuscitation unit with the placenta still connected to the infant. In this EPT group, continuous positive airway pressure support was initiated while, simultaneously, placental blood was transfused by holding the placenta 40-50 cm above the infant's heart. The cords of another 20 infants were clamped before respiratory support was started (standard group). Data on the infants' outcome were compared retrospectively. In a subgroup of 22 infants (n = 14 EPT, n = 8 standard), respiratory function monitor recordings were performed and both heart rates and SpO<sub>2</sub> levels in the first 10 min of life were compared between groups.

Results

Although infants in the EPT group were lighter (EPT: 875 ± 355 g, standard: 1,117 ± 389 g; p = 0.02) and younger (266/7 weeks ± 19 days vs. 282/7 weeks ± 18 days; p = 0.045), there was no difference in neonatal outcome, including the incidence of intraventricular hemorrhage, bronchopulmonary disease, and red blood cell transfusions (all p > 0.1). Moreover, no differences in SpO<sub>2</sub> levels and heart rates were observed in the infants whose resuscitations were recorded using a respiratory function monitor.

Conclusions

In this retrospective analysis, EPT had no negative effects on the outcome of the infants, which warrants further evaluation in prospective randomized studies.

Keywords: Very-low-birth-weight infants, Delayed cord clamping, Cord milking, Fetal-to-neonatal transition, Lung aeration

What Is It about?

Delayed cord clamping improves cardiovascular stability and outcome of preterm infants, but may delay initiation of respiratory support. To allow lung aeration during cord blood transfusion, we implemented a novel extrauterine placental transfusion (EPT) approach in which both preterm infants and their placentas are delivered by cesarean section. Then, placental blood is transfused by holding the placenta 40–50 cm above the infant's heart. Simultaneously, lung aeration is supported by continuous positive airway pressure. To assess the impact of this procedure, we compared the outcome of infants <32 weeks' gestation who received EPT to infants who received standard care in this retrospective cohort study.

Introduction

There is growing evidence that delayed cord clamping (DCC) or cord milking (CM) improves the outcome of preterm infants by reducing the risk of intraventricular hemorrhage, necrotizing enterocolitis, and the need for red blood cell transfusion (RBCT) [1, 2, 3]. In part, these positive effects of prolonged placental transfusion might be attributed to better hemodynamic stability during the process of fetal-to-neonatal transition [4]. As shown by recent animal studies, clamping the cord after the lungs have been aerated is beneficial, as placental blood supply during lung aeration improves cardiac output and pulmonary blood flow [5, 6]. In contrast, if the cord is clamped before the lungs are aerated, there may not be sufficient blood available to compensate for the increased pulmonary blood flow. This might jeopardize premature infants in whom low cardiac output (due to insufficient preload) might coincide with hypoxia (due to immaturity of the lungs). Prolonged placental transfusion until the lungs are aerated may protect from such a scenario [7].

However, a technical problem of DCC approaches in preterm infants is that initiation of respiratory support by mask continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) therapy might also be delayed because resuscitation equipment is not routinely available within the immediate vicinity of the mother. Although several centers have implemented mobile resuscitation units that allow respiratory support with intact placental circulation [8, 9, 10], these devices are not yet ready for widespread clinical use. Moreover, the delivery of multiples or short umbilical cords may limit the use of such bedside resuscitation trolleys in very preterm infants [11].

Several years ago, obstetricians in our tertiary care neonatal center implemented a novel approach called “extrauterine placental transfusion” (EPT). The EPT approach comprises both initiation of CPAP support and placental transfusion at the same time. Following this procedure, preterm born infants are delivered by caesarean section with the placenta still attached to the infant via the umbilical cord. Then, placental transfusion is performed up to several minutes by holding the placenta approximately 40-50 cm above the baby's heart while respiratory support by mask CPAP is initiated simultaneously.

However, the EPT approach has not yet been evaluated and its effects are unclear. In this article, we provide a detailed description of the EPT technique, including a video demonstration, and evaluate the safety of this technique by comparing neonatal outcome parameters in a retrospective cohort study of infants born <32 weeks' gestation over a 9-month period in our center who either received EPT or whose cords were clamped before respiratory support was initiated.

Patients and Methods

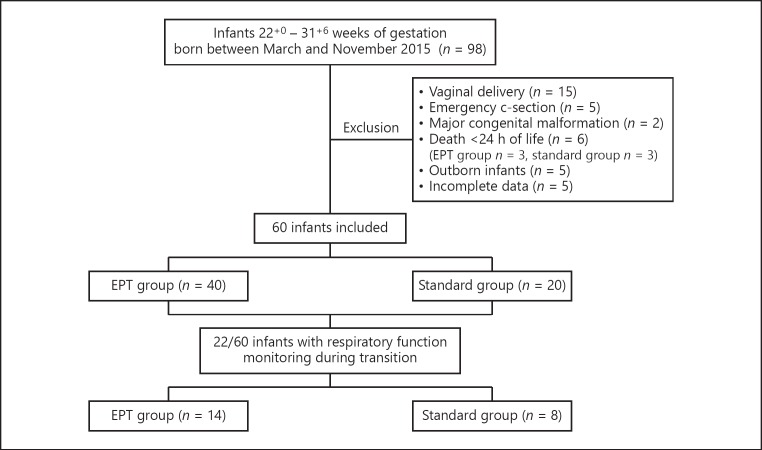

The present trial was approved by the ethics board of the University Hospital of Cologne. For this retrospective cohort study, inborn infants born between March and November 2015 between 220/7 and 316/7 weeks of gestation were eligible. Exclusion criteria were vaginal delivery, emergency caesarean section, major congenital anomalies, or death during the first 24 h of life (Fig. 1). Resuscitation of all infants was performed as described [12] with the exception that FiO2 levels were initially set to 0.21-0.3. Then, during the first 10 min of life, FiO2 levels were adjusted individually, aiming to keep the infant's SpO2 levels >10th percentile of the SpO2 values published by Dawson et al. [13] for infants <32 weeks of gestation.

Fig. 1.

Schematic overview of the patient population of the study.

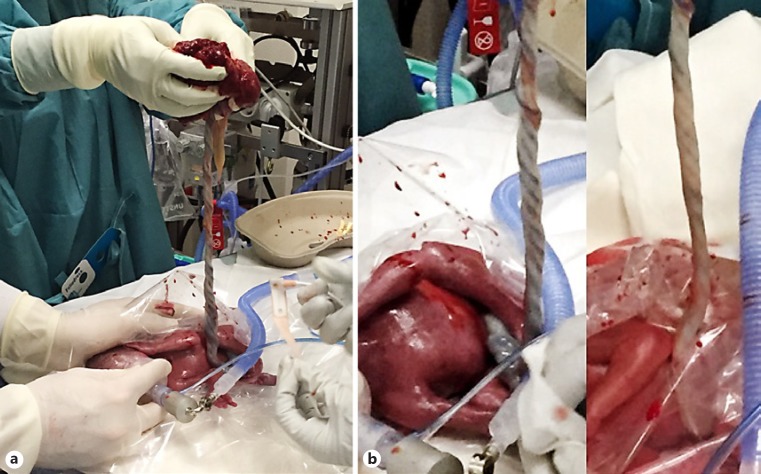

We compared two groups: a standard group and an EPT group. The standard group comprised infants who either received CM or DCC before mask CPAP support was started. Infants in the EPT group were transferred to the resuscitation unit with an intact amniotic sac and the placenta still attached to the infant via the umbilical cord. If their membranes ruptured prior to or during caesarean section, the infants were transferred to the resuscitation bed only with the placenta and intact umbilical cord. Infants in the EPT group then received placental blood transfusion by holding the placenta 40-50 cm over the baby's heart (Fig. 2a; suppl. video file 1; see www.karger.com/doi/10.1159/000488926 for all online suppl. material). Simultaneously, mask CPAP support was started in these babies and umbilical cords were clamped after variable times at the discretion of the neonatologist. This was usually done when infants were breathing regularly and umbilical vessels had visibly collapsed (Fig. 2b). Following this procedure, placental transfusion was sustained while the infants' lungs were aerated, thus supporting the physiological processes of fetal-to-neonatal transition. The time of cord clamping was recorded in the delivery protocols. The EPT technique has been performed for many years in our center as an equivalent alternative standard of care to DCC or CM in infants born <32 weeks of gestation without any evidence of negative effects on the outcome of the babies' mothers.

Fig. 2.

a Picture of the EPT procedure with simultaneous mask CPAP support. b Image of the umbilical cord at the beginning of the EPT procedure (a) and after 5 min of the manoeuver (b). Note the collapsed cord after aeration of the lungs.

Basic patient and outcome data were collected until discharge and included the following parameters: gestational age, birth weight, gender, APGAR scores, time to cord clamping in the EPT group, grade of intraventricular hemorrhage, bronchopulmonary disease, necrotizing enterocolitis or spontaneous intestinal perforation with need of surgery, peak serum bilirubin levels, RBCT during the first 7 and 28 days of life, respectively, and survival until discharge. Bronchopulmonary disease was diagnosed according to the criteria of Walsh et al. [14] at 36 weeks' postmenstrual age. Intraventricular hemorrhage was graded on a scale of 1-4, based on the classification of Papile et al. [15].

In a subgroup of 22 infants, resuscitation procedures were recorded using a respiratory function monitor (NewLifeBox Neo-RSD, Advanced Life Diagnostics UG, Weener, Germany), including a video camera. These recordings comprised pulse oximetric data (SpO2 levels and heart rate) measured by Masimo Radical 7 pulse oximeters (Masimo Corporation, Irvine, CA, USA) on which the first 10 min of life were analyzed and compared between the two cohorts. In this “monitor subgroup,” we defined minute 0 as the time when respiratory support on the resuscitation unit was started.

Management of Red Blood Cell Transfusion

In all patients, transfusion of red blood cells was performed using hematocrit threshold values of the “liberal transfusion threshold group” defined in the “Effects of Transfusion Thresholds on Neurocognitive Outcome of Extremely Low Birth-Weight Infants” study [16] as cutoff values for RBCT. If hematocrit values were not available from lab testing, we alternatively considered hemoglobin values to indicate RBCT. In addition to these thresholds, neonatologists also considered individual parameters such as the infant's clinical condition or the availability of specially prepared extra small packages of red blood cells (80 mL) to indicate RBCT.

Data Analysis

Data analysis was performed using IBM SPSS software, Version 23 for Windows (SPSS Inc.). Variables are described as means (SD), medians (IQR) or absolute and relative frequencies. Differences between groups were compared by a t test for normally distributed data, the Mann-Whitney U test for other metric data, the Wilcoxon test for testing related samples, or Fisher's exact test for categories to test results for statistical significance. A 2-sided p < 0.05 was defined as statistically significant.

Results

Sixty infants met the inclusion criteria and were considered for analysis. Of these, 40 received EPT while another 20 infants comprised the standard group (Fig. 1). Clinical covariates of all infants and outcome data are summarized in Table 1. As shown, gestational age and birth weight were significantly lower in the EPT group while none of the investigated outcome parameters differed significantly between the groups. Five patients in the EPT group had a spontaneous intestinal perforation, as compared to none of the infants in the standard group (Table 1). However, this finding was not statistically significant. An additional lineal regression analysis found no correlation between EPT and necrotizing enterocolitis/spontaneous intestinal perforation (data not shown).

Table 1.

Basis data and outcome parameters of the full study collective

| EPT group (n = 40) | Standard group (n = 20) | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean gestational age (SD), weeks + days | 26 +6 (19 days) | 28 +2 (18 days) | 0.045 |

| Mean birth weight (SD), g | 875 (355) | 1,117 (389) | 0.02 |

| Mean APGAR scores (SD), 1/5/10 min | 5.5/7.2/8.2 (1.8/1.0/0.5) | 6.0/7.5/8.4 (1.4/0.6/0.7) | 0.26/0.25/0.33 |

| Surfactant therapy | 38/40 (95%) + | 20/20 (100%) + | 0.55 |

| LISA | 36/40 (90%) + | 20/20 (100%) + | 0.29 |

| Invasive mechanical ventilation <24 h of life | 3/40 (8%) + | 1/20 (5%) + | 1.00 |

| IVH, all grades | 13/40 (33%) + | 6/20 (30%) + | 0.99 |

| BPD | 12/35 (34%) + | 5/19 (26%) + | 0.94 |

| NEC/SIP with surgery | 5/40 (13%) + | 0/20 1 | 0.12 |

| Mean temperature at admission (SD), ° C | 36.04 (0.89) | 36.29 (0.84) | 0.34 |

| Survival until discharge | 36/40 (90%) + | 19/20 (95%) + | 0.45 |

| Mean hemoglobin in the first 24 h of life (SD), g/dL | 17.10 (3.28) | 17.14 (3.59) | 0.96 |

| Red blood cell transfusion during first 7 days | 8/35 (23%) + | 4/19 (21%) + | 1.0 |

| Red blood cell transfusion during first 28 days | 17/35 (49%) + | 6/19 (32%) + | 0.26 |

| Peak serum bilirubin (SD), mg/dL | 9.06 (2.06) | 10.3 (2.26) | 0.05 |

Tests for statistical significance were done using a t test and Fisher ' s exact test, respectively. EPT, extrauterine placental transfusion; LISA, less invasive surfactant administration; IVH, intraventricular hemorrhage; BPD, bronchopulmonary disease; NEC, necrotizing enterocolitis; SIP, spontaneous intestinal perforation. + n absolute (n relative).

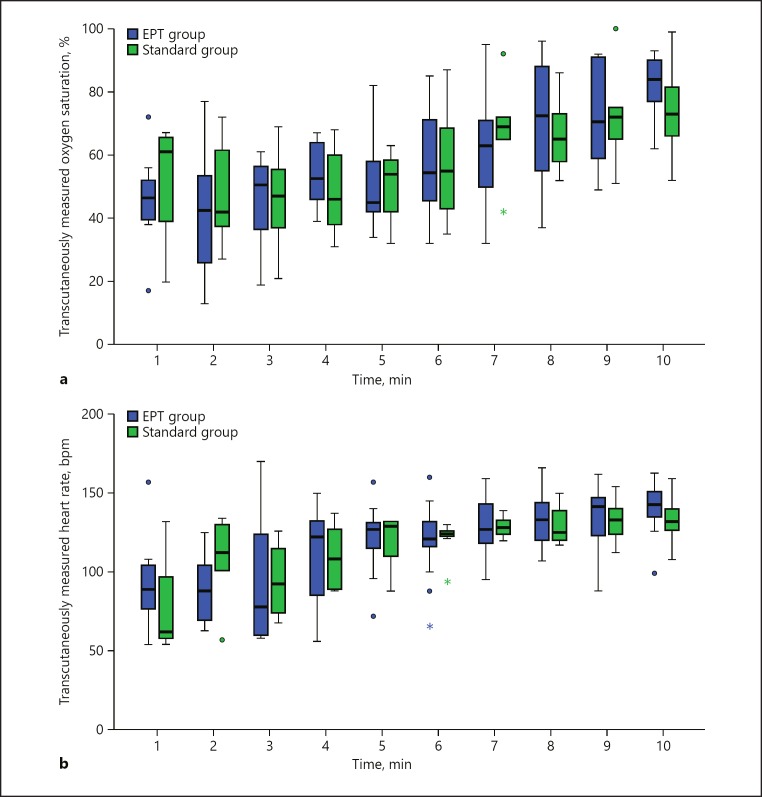

To further analyze whether the EPT procedure might negatively affect an infant's heart rate and oxygen saturation level during transition, we analyzed a subgroup of 22 infants whose resuscitations were recorded using a respiratory function monitor (EPT group n = 14; standard group n = 8). Basic patient characteristics were comparable in both groups (Table 2). The transcutaneously measured oxygen saturation curves of both cohorts during transition are shown in Figure 3a. SpO2 levels did not differ significantly at any time point during the first 10 min of life (all p > 0.1; Table 3). Of note, there was also no difference in the FiO2 levels applied to the infants in the first 10 min of life (data not shown), proving that resuscitation following our standard [12] was performed uniformly in all patients. Similarly, there were no differences in the heart rates of the infants at any time point during transition (all p > 0.1; Table 4; Fig. 3b), thus showing that the EPT procedure neither exerts negative effects on an infant's heart rate nor on oxygenation during transition.

Table 2.

Basic patient characteristics of the subgroup of patients with respiratory function monitor recordings

| EPT group (n = 14) | Standard group (n = 8) | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Birth weight, g | 906 (364) | 1,069 (367) | 0.33 |

| Gestational age, weeks + days | 27+ 3 (19 days) | 27+ 4 (14 days) | 0.84 |

| APGAR 1 min | 6.1 (1.1) | 5.9 (1.1) | 0.59 |

| APGAR 5 min | 7.5 (0.7) | 7.5 (0.5) | 1.00 |

| APGAR 10 min | 8.5 (0.5) | 8.4 (0.5) | 0.59 |

Values are depicted as means (SD). Tests for statistical significance were done using a t test. EPT, extrauterine placental transfusion.

Fig. 3.

a Oxygen saturations during the first minutes of life. Box plots represent the median, IQR, maximum and minimum values. Values more than 1.5 IQRs from the end of the box are labelled as outliers (⚫); values more than 3 IQRs from the box are labelled as extremes (*). b Heart rate during the first minutes of life. Box plots represent the median, IQR, maximum and minimum values. Values more than 1.5 IQRs from the end of the box are labelled as outliers (⚫), values more than 3 IQRs from the box are labelled as extremes (*).

Table 3.

Oxygen saturation during transition of the newborn

| Minutes after birth | Oxygen saturation, % |

p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| EPT group | standard group | ||

| 1 | 46 (16)*/47 (15) + | 52 (22)*/61 (37) + | 0.36 |

| 2 | 41 (18)*/43 (28) + | 46 (20)*/42 (42) + | 0.65 |

| 3 | 46 (14)*/51 (21) + | 46 (17)*/47 (28) + | 1.0 |

| 4 | 54 (10)*/53 (20)+ | 48 (14)*/46 (26) + | 0.43 |

| 5 | 51 (15)*/54 (19) + | 50 (12)*/54 (25) + | 0.75 |

| 6 | 57 (18)*/55 (30) + | 57 (19)*/55 (37) + | 0.96 |

| 7 | 62 (19)*/63 (29) + | 68 (29)*/69 (29) + | 0.56 |

| 8 | 70 (20)*/73 (37) + | 67 (13)*/65 (25) + | 0.62 |

| 9 | 73 (16)*/71 (33) + | 73 (18)*/72 (30) + | 1.0 |

| 10 | 82 (9)*/84 (15) + | 74 (15)*/73 (18)+ | 0.18 |

Transcutaneously measured oxygen saturation during the first 10 min of life. Tests for statistical significance were done using a Mann-Whitney U test. Values are indicated in percent of oxygenated hemoglobin.

Mean (SD), + median (IQR).

Table 4.

Heart rate during transition of the newborn

| Minutes after birth | Heart rate, bpm |

p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| EPT group | standard group | ||

| 1 | 94 (31)*/89 (31) + | 83 (43)*/62 (–)+ | 0.49 |

| 2 | 89 (22)*/88 (62) + | 108 (28)*/112 (41) + | 0.15 |

| 3 | 95 (40)*/78 (69) + | 95 (22)*/92 (46) + | 0.52 |

| 4 | 112 (31)*/122 (55) + | 110 (23)*/108 (41) + | 0.82 |

| 5 | 119 (25)*/127 (27) + | 114 (22)*/128 (44) + | 0.81 |

| 6 | 120 (24)*/121 (28) + | 121 (12)*/124 (6) + | 1.0 |

| 7 | 129 (21)*/127 (30) + | 129 (8)*/128 (14) + | 1.0 |

| 8 | 134 (17)*/133 (27) + | 130 (14)*/125 (26) + | 0.68 |

| 9 | 136 (19)*/141 (26) + | 133 (16)*/133 (29) + | 0.5 |

| 10 | 140 (17)*/143 (21) + | 133 (16)*/132 (24) + | 0.27 |

Transcutaneously measured heart rates during the first 10 min of life. Tests for statistical significance were done using the Mann-Whitney U test. bpm, beats per minute.

Mean (SD), + median (IQR).

Intriguingly, we found that the cords of the EPT infants were clamped late (mean time to cord clamping: 4.8 min [SD 1.4]). No changes in SpO2 levels were observed before or after clamping the cord (mean saturation of 53% [SD 15] a minute before cord clamping vs. 52% [SD 15] a minute after cord clamping [p = 0.55]). In contrast, the mean heart rate of the EPT infants increased from 94 bpm (SD 31) from the minute before clamping to 124 bpm (SD 25) in the minute after cord clamping, which was statistically significant (p = 0.002).

Discussion

While the EPT technique has been described in term infants after vaginal delivery over a century ago [17], the practice of delivering both preterm infants and the placenta by caesarean section to resuscitate infants before clamping the cord was first reported by Peter Dunn [18] in the 1970s. Although he showed a fourfold reduction in neonatal mortality of preterm infants after establishing this approach, the technique was not evaluated further. Moreover, the current practice of noninvasive CPAP support for resuscitation of preterm infants was not common practice in the 1970s [19, 20]. Therefore, the effects of the EPT technique on an infant's transition and outcomes, respectively, when combined with current resuscitation approaches remain elusive.

In this first retrospective cohort study on our EPT approach, we did not observe differences in heart rates and oxygenation during transition or in neonatal outcome in infants who received EPT compared to infants who received CM or DCC.

Limitations

Our findings are, however, limited by several points. First, the data was collected retrospectively and comprised a limited number of infants. Therefore, our results cannot be generalized and further trials with larger patient numbers are needed to fully evaluate the impact of the EPT procedure. Second, the patient cohorts differed significantly with respect to gestational age and birth weight. However, it appears legitimate to underline that patients of the EPT group were significantly lighter and more immature, and therefore were expected to show higher rates of complications. In this respect, it is intriguing that we did not observe differences between groups concerning the frequency of RBCT in the first 7 and 28 days of life. As younger and lighter infants have a relatively higher iatrogenic blood loss, prolonged EPT might have accounted for higher postnatal blood volumes in these babies. Given the rather long time to cord clamping of 4.8 min in EPT patients, this hypothesis is supported by observations from Farrar et al. [21] who measured 24-32 mL/kg of transfused placental blood by continuously weighing infants immediately after birth until the cords were clamped after 2–5 min. While either CM or DCC (≥30 s) is the standard approach for non-EPT infants at our hospital, a thorough comparison of the impact of EPT versus CM/DCC on infants' hematocrit values was not possible in our study since we did not have data on how long DCC (and how many cycles of CM, respectively) had been performed in each infant of the standard group. For further investigations, it will be crucial to record how long cord clamping was delayed after birth and how often cords have been milked, respectively.

Moreover, we did not measure the amount of blood taken in relation to the patient's birth weight as performed in a first randomized trial on DCC [22]. Finally, it should be stressed that although there were established transfusion thresholds at our NICU, “soft” criteria such as infants' clinical conditions were also considered to indicate blood transfusion. Due to these facts, a thorough assessment of the effect of EPT on hematocrit values and RBCT requires a prospective randomized controlled trial.

Despite the limitations of our study, in our opinion the EPT approach warrants further investigation because it may also be performed when CM or DCC is not possible and also in infants in whom placement on a resuscitation trolley to initiate respiratory support with an intact cord is not feasible. This might be the case in both multiple pregnancies and in infants with short umbilical cords. Apart from that, EPT may also be performed in asphyxiated infants. While a recent study by Polglase et al. [23] provides strong evidence that resuscitation with an intact cord mitigates postasphyxia cerebral injury in near-term lambs, current guidelines do not recommend DCC in asphyxiated newborns but instead state that “…infants who are not breathing or crying may require the umbilical cord to be clamped, so that resuscitation measures can commence promptly” [24]. In fact, in a recent study by Katheria et al. [9], 22% of (singleton) infants were not placed on bedside resuscitation trolleys because of the obstetrician's assessment that the infant was too unstable. The same study also challenges the rationale of cord clamping after the initiation of breathing by showing that very-low-birth-weight infants who received respiratory support after the cord was clamped had comparable outcomes to infants who received CPAP/PPV before cord clamping. Yet, the observations of this trial might not be transferred to our study for a couple of reasons. First, both the birth weights and gestational ages of the infants were lower in our trial. Therefore, we cannot conclude that spontaneous breathing without CPAP would have occurred in our more immature infants. Second, it remains unclear to what extent unsupported breaths of very immature infants resulted in aeration of the lungs since the authors did not monitor end-tidal CO2 in infants of the DCC-only group after initiation of CPAP. Third, the mean time to cord clamping was 65 s in the study by Katheria et al. [9] as opposed to more than 240 s in our study, which further impedes the comparability of our approaches.

Finally, a notable finding of our study was the higher rate of intestinal perforations in the EPT group, although it did not differ significantly from the incidence of spontaneous intestinal perforation in the standard group. Even if an increasing incidence of intestinal perforations with lower gestational ages and birth weight [25] is taken into account, an influence of EPT on intestinal perfusion (possibly due to hyperviscosity) cannot be excluded and should be analyzed in a future prospective trial. In contrast, it is reassuring to see that neither the intubation rate in the first 24 h nor the eligibility for less invasive surfactant administration (LISA) was different between the groups. And although infants who passed away in the first 24 h of life were excluded from the trial in order to have full information on the outcome parameter, the finding that 3 infants of each group died at this early age shows that EPT did not have an impact on early mortality or morbidity (<24 h of life).

In conclusion, our nonrandomized retrospective study provides first evidence that EPT is safely feasible in very-low-birth-weight infants. As it approximates a physiological fetal-to-neonatal transition it might have beneficial effects on cardiovascular stability and neonatal outcome, and should therefore be investigated in future controlled trials.

Disclosure Statement

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Backes CH, Rivera B, Haque U, Copeland K, Hutchon D, Smith CV. Placental transfusion strategies in extremely preterm infants: the next piece of the puzzle. J Neonatal Perinatal Med. 2014;7:257–267. doi: 10.3233/NPM-14814034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rabe H, Diaz-Rossello JL, Duley L, Dowswell T. Effect of timing of umbilical cord clamping and other strategies to influence placental transfusion at preterm birth on maternal and infant outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;8:CD003248. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003248.pub3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rabe H, Reynolds G, Diaz-Rossello J. A systematic review and meta-analysis of a brief delay in clamping the umbilical cord of preterm infants. Neonatology. 2008;93:138–144. doi: 10.1159/000108764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Manley BJ, Owen LS, Hooper SB, Jacobs SE, Cheong JLY, Doyle LW, Davis PG. Towards evidence-based resuscitation of the newborn infant. Lancet. 2017;389:1639–1648. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30547-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bhatt S, Polglase GR, Wallace EM, Te Pas AB, Hooper SB. Ventilation before umbilical cord clamping improves the physiological transition at birth. Front Pediatr. 2014;2:113. doi: 10.3389/fped.2014.00113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hooper SB, Polglase GR, Roehr CC. Cardiopulmonary changes with aeration of the newborn lung. Paediatr Respir Rev. 2015;16:147–150. doi: 10.1016/j.prrv.2015.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hutchon DJ. Ventilation before umbilical cord clamping improves physiological transition at birth or “umbilical cord clamping before ventilation is established destabilizes physiological transition at birth. ” Front Pediatr. 2015;3:29. doi: 10.3389/fped.2015.00029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hutchon DJ. Evolution of neonatal resuscitation with intact placental circulation. Infant. 2014;10:58–61. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Katheria A, Poeltler D, Durham J, Steen J, Rich W, Arnell K, Maldonado M, Cousins L, Finer N. Neonatal resuscitation with an intact cord: a randomized clinical trial. J Pediatr. 2016;178:75–80. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2016.07.053. e3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Winter J, Kattwinkel J, Chisholm C, Blackman A, Wilson S, Fairchild K. Ventilation of preterm infants during delayed cord clamping (VentFirst): a pilot study of feasibility and safety. Am J Perinatol. 2016;34:111–116. doi: 10.1055/s-0036-1584521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Georgiadis L, Keski-Nisula L, Harju M, Raisanen S, Georgiadis S, Hannila ML, Heinonen S. Umbilical cord length in singleton gestations: a Finnish population-based retrospective register study. Placenta. 2014;35:275–280. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2014.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mehler K, Grimme J, Abele J, Huenseler C, Roth B, Kribs A. Outcome of extremely low gestational age newborns after introduction of a revised protocol to assist preterm infants in their transition to extrauterine life. Acta Paediatr. 2012;101:1232–1239. doi: 10.1111/apa.12015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dawson JA, Kamlin CO, Vento M, Wong C, Cole TJ, Donath SM, Davis PG, Morley CJ. Defining the reference range for oxygen saturation for infants after birth. Pediatrics. 2010;125:e1340–e1347. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-1510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Walsh MC, Yao Q, Gettner P, Hale E, Collins M, Hensman A, Everette R, Peters N, Miller N, Muran G, Auten K, Newman N, Rowan G, Grisby C, Arnell K, Miller L, Ball B, McDavid G, National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Neonatal Research Network Impact of a physiologic definition on bronchopulmonary dysplasia rates. Pediatrics. 2004;114:1305–1311. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-0204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Papile LA, Burstein J, Burstein R, Koffler H. Incidence and evolution of subependymal and intraventricular hemorrhage: a study of infants with birth weights less than 1,500 gm. J Pediatr. 1978;92:529–534. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(78)80282-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.ETTNO Investigators. The “Effects of Transfusion Thresholds on Neurocognitive Outcome of Extremely Low Birth-Weight Infants (ETTNO)” study: background, aims, and study protocol. Neonatology. 2012;101:301–305. doi: 10.1159/000335030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Várdi P. Placental transfusion an attempt at physiological delivery. Lancet. 1965;286:12–13. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dunn PM. Premature delivery and the preterm infant. Ir Med J. 1976;69:246–254. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lindner W, Vossbeck S, Hummler H, Pohlandt F. Delivery room management of extremely low birth weight infants: spontaneous breathing or intubation? Pediatrics. 1999;103:961–967. doi: 10.1542/peds.103.5.961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Morley CJ, Davis PG, Doyle LW, Brion LP, Hascoet JM, Carlin JB, COIN Trial Investigators Nasal CPAP or intubation at birth for very preterm infants. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:700–708. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa072788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Farrar D, Airey R, Law GR, Tuffnell D, Cattle B, Duley L. Measuring placental transfusion for term births: weighing babies with cord intact. BJOG. 2011;118:70–75. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2010.02781.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rabe H, Wacker A, Hulskamp G, Hornig-Franz I, Schulze-Everding A, Harms E, Cirkel U, Louwen F, Witteler R, Schneider HP. A randomised controlled trial of delayed cord clamping in very low birth weight preterm infants. Eur J Pediatr. 2000;159:775–777. doi: 10.1007/pl00008345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Polglase GR, Blank DA, Barton SK, Miller SL, Stojanovska V, Kluckow M, Gill AW, LaRosa D, Te Pas AB, Hooper SB. Physiologically based cord clamping stabilises cardiac output and reduces cerebrovascular injury in asphyxiated near-term lambs. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2017 doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2017-313657. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wyllie J, Bruinenberg J, Roehr CC, Rudiger M, Trevisanuto D, Urlesberger B, European Resuscitation Council Guidelines for Resuscitation 2015 Section 7. Resuscitation and support of transition of babies at birth. Resuscitation. 2015;95:249–263. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2015.07.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Okuyama H, Kubota A, Oue T, Kuroda S, Ikegami R, Kamiyama M. A comparison of the clinical presentation and outcome of focal intestinal perforation and necrotizing enterocolitis in very-low-birth-weight neonates. Pediatr Surg Int. 2002;18:704–706. doi: 10.1007/s00383-002-0839-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]