Abstract

Background and Aims

Natural dyes and pigments are nontoxic, ecofriendly alternatives to synthetic counterparts and beetroot is one such natural dye. The red color of beetroot derived from betalain pigments confers great advantage to this plant. In this study, the physiochemical and spectrophotometric characteristics of beetroot as well as the histological staining potential of various tissues were carried out to determine its tissue specificity.

Methods

The aqueous and ethanol extracts of beetroot were prepared using distilled water and 95% ethanol, respectively. Spectrophotometry, pH, and concentration of both extracts were determined before histological staining with 10% neutral-buffered formalin-fixed, paraffin-wax-embedded tissue sections. Stained sections were viewed with a photomicroscope.

Results

The aqueous and ethanol extracts of beetroot were slightly acidic and soluble at concentrations of 381.5 mg/100 g and 253.7 mg/100 g fresh beetroot sample, respectively. Both extracts consist of three betalain pigments with absorbances at different spectrophotometric wavelengths, namely betaxanthins (475 nm), betanin (525 nm), and betanidin (575 nm). The maximum absorbance was 0.925 and 0.615 for the aqueous and ethanol extracts, respectively, at a peak wavelength of 525 nm for each extract. Both extracts stained various tissue structures such as muscles, mucins, red blood cells, keratin, and nerve fibers.

Conclusion

Thus, beetroot stain is slightly acidic, contains betalain pigments, stains basic histological tissue structures, and can be used as an ecofriendly alternative to hematoxylin and eosin.

Keywords: Beetroot, Spectrophotometry, Concentration, Betalain, Histology, Tissues, Aqueous extract, Ethanol extract, Beta vulgaris L.

What Is It about?

Beetroot is a nutrient-rich food which has long been used as food colorant and additive because of its red color. Other studies have used beetroot in staining parasites and buccal smears. However, this study analyzed, for the first time, the pH, concentration, and spectrophotometric properties of beetroot dye in order to apply this knowledge to staining of animal tissues. Interestingly, the aqueous and ethanol extracts of beetroot dye stained most basic tissue structures because they are slightly acidic and contain betalain pigments. Thus, this study has contributed to knowledge by providing a scientific background to why different animal tissues are selectively stained by beetroot dye.

Introduction

Beetroot, also known as Beta vulgaris L., is the taproot portion of the beet plant. It belongs to the family Chenopodae [1, 2, 3] and order Caryophyllales [4, 5]. Beetroot has been used as food [6] and as medicinal plant for the treatment of various ailments because of its lipotropic, antioxidant, and antitumor properties [1]. Beetroot has also been widely used industrially as food colorant due to its red color from the pigment betalain mainly from betanin, betanidin, and betaxanthin [4]. Betalains are water-soluble nitrogen-containing indoles derived from the amino acid tyrosine [7]. Betanin is the most abundant of the dyes and was first isolated by Schudel in 1918 [8].

Betanin pigment has been used industrially and in staining of various substances. It has been used in inks and in staining woods [9] as well as in staining wool and thread [6]. Also, it has been used in staining of helminth parasites [3, 10] and ova of intestinal nematodes [2]. Recently, Singnarpi et al. [1] have applied beetroot in cytology for staining of buccal smears and Das et al. [11] have applied beetroot dye as a fluorescent dye in tissue staining. Although beetroot is generally used as food colorant, in staining helminth parasites, and in cytology, little knowledge has been uncovered about the usefulness of beetroot extracts as a potent stain in histology. Hence the desire to explore this natural plant for its tissue-staining properties when compared with hematoxylin and eosin (HE)-stained counterparts as well as to determine the spectrophotometric properties, pH, and concentration of the betalain pigments.

Materials and Methods

Plant Material/Preparation

Beetroots were obtained from Marian market, Calabar. They were identified and authenticated at the Department of Botany, Faculty of Biological Sciences, University of Calabar. The beetroot was washed with water and the skin peeled with a knife.

Procedure for Aqueous and Ethanol Extract Preparation

0.5 g each of the beetroot was weighed with a digital weighing balance and grinded in a mortar by adding 10 mL of distilled water (or 10 mL of ethanol) until complete crushing and extraction of the pigment was achieved. Then, the remaining 5 mL of distilled water (or 5 mL of ethanol) was used to rinse the remaining plant material in the mortar. The solutions were filtered using Wattman No. 1 filter paper into separate beakers and labeled 100% aqueous and 100% ethanol beetroot extracts, respectively.

Preparation of Dilution Series (50, 25, and 12.5%)

Three test tubes each for the 50, 25, and 12.5% dilutions were set up for the aqueous and ethanol beetroot extracts. For the 50% solution, 4 mL of the 100% solution was put in a test tube and 4 mL of distilled water (or ethanol) was added. For the 25% solution, 4 mL of the 50% solution was transferred into a test tube and 4 mL of distilled water (or ethanol) was added. While for the 12.5% solution, 4 mL of the 25% solution was transferred into a test tube and 4 mL of distilled water (or ethanol) was added.

Spectrophotometric Analysis

The wavelength of the UV-Vis spectrophotometer (UV-2502, LaboMed Inc., USA) was set to 450 nm. Distilled water (or ethanol) in a cuvette was used to blank the spectrophotometer, before absorbance of the solution was read at intervals of 25 nm wavelength between 450 and 800 nm for aqueous extracts as well as between 450 and 650 nm for ethanol extracts.

Concentration of Beetroot Dye

Concentration of the fresh beetroot dye (betalain content) in the solvents (distilled wa ter or ethanol) was determined using the formula of Singh et al. [4] and expressed as mg betalain/100 g beetroot powder as follows:

Total betalain content (mg/g) = A × DF × MW × 1,000/ϵL,

where A = absorption value at 525 nm, DF = dilution volume, MW = molecular weight of betalain at 550 g/mol, ϵ = extinction coefficient for betalains at 60,000 L/mol, L = path length of cuvette (1 cm).

pH Measurement

The pH of the aqueous and ethanol solution was determined with the use of a pH meter.

Preparation of Beetroot Stain

The staining solution was prepared using 1,800 g beetroot (blended to powder) dissolved in 600 mL of distilled water or ethanol. The staining solution was filtered and refrigerated at 4°C. Before staining, glacial acetic acid (GAA) was added at a ratio of 1: 2 by adding 0.5 mL of GAA to 1 mL of the staining solution to enhance the staining ability.

Animal Material and Tissue Processing

An albino rat was bought from the Animal House, College of Medical Sciences, University of Calabar. The rat was sacrificed by chloroform inhalation method according to the guidelines of the Animal Ethics Committee, Faculty of Basic Medical Sciences, University of Calabar. Ten tissues were removed, namely heart, brain, small intestine, skin, large intestine, kidney, liver, and lung. The tissues were fixed in 10% neutral-buffered formalin for a duration of 48 h. All tissues were processed with the routine paraffin-wax-embedding method. Tissue sections were cut at 4 µm with a rotary microtome and placed on 2 slides each for beetroot and Cole's HE staining method.

Staining Techniques

Tissue sections were divided into 2 experimental groups A and B. Group A was stained using the beetroot staining solution and Group B using Cole's HE staining method.

Beetroot Staining Method

Tissue sections were dewaxed in xylene and hydrated through descending grades of ethanol and distilled water before staining with beetroot staining solution for 1 h 30 min. The slides were rinsed in tap water, dehydrated, cleared, and mounted using DPX.

Cole's HE Staining Method

Tissue sections were dewaxed in xylene and hydrated through descending grades of ethanol and distilled water before staining with Cole's HE for 10 min, rinsed in water, and counterstained with 1% eosin for 30 min. The slides were rinsed in tap water, dehydrated, cleared, and mounted using DPX.

Results

Table 1 shows the physiochemical properties of the aqueous and ethanol extracts of beetroot. Both extracts appeared dark red in color and maintained dying ability when stored in a refrigerator at 4°C. All extracts showed an acidic pH of 5.5 when examined. The beetroot was soluble in distilled water and ethanol at a concentration of 381.5 mg/100 g and 253.7 mg/100 g, respectively. The spectrophotometric curves of the aqueous extract (Fig. 1) and ethanol extract (Fig. 2) of beetroot showed 3 peaks at 475, 525, and 575 nm. The maximum absorbance was 0.925 for the aqueous extract and 0.615 for the ethanol extract at a peak wavelength of 525 nm for each extract.

Table 1.

Physiochemical properties of the aqueous and ethanol extracts of beetroot

| Properties | Aqueous extract | Ethanol extract |

|---|---|---|

| Color | deep red | red |

| PH | 5.5 | 5.5 |

| Solubility | soluble | soluble |

| Concentration | 381.5 mg/100 g | 253.7 mg/100 g |

Fig. 1.

Spectrophotometric curve of aqueous extract of beetroot.

Fig. 2.

Spectrophotometric curve of ethanol extract of beetroot.

In the photomicrographs, stained tissue sections acquired varying degrees of staining with the beetroot extracts as compared to HE control sections. The color of the extract was absorbed by tissues, but intensity differed based on internal structures present.

Plate 1 (Fig. 3) shows sections of the cerebral cortex and lungs. Figure 3a shows poor staining of nuclei but good staining of nerve fibers with aqueous beetroot extract as compared to the HE-stained section of the cerebral cortex in Figure 3b showing distinct layers and staining of the neuronal cells and neuroglia. Lungs stained with alcohol beetroot extract in Figure 3c show brown staining of nuclei with distinct alveoli spaces, while the HE-stained lung tissue shows prominent alveoli spaces and clear distinction of epithelial cells in Figure 3d.

Fig. 3.

Plate 1: Cerebral cortex and lungs stained with aqueous and ethanol beetroot extracts and HE. a, b Cerebral cortex. Magnification ×100. c, d Lungs. Magnification ×400. ALS, alveoli spaces; BRC, bronchiole.

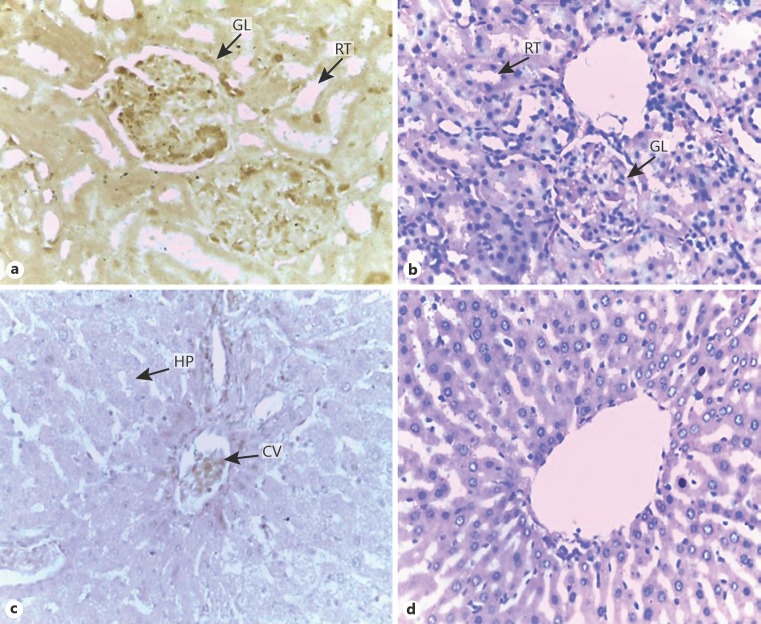

Plate 2 (Fig. 4) shows histology of kidney and liver stained with aqueous and alcohol beetroot extracts. In Figure 4a, the kidney stained with aqueous beetroot extract shows glomeruli and renal tubules. The ground substance and cytoplasm stained light brown and the nuclei deep brown. The HE-stained kidney in Figure 4b shows prominent renal tubules and glomeruli with clear distinction between the basophilic stained nuclei and the eosinophilic cytoplasm. In Figure 4c, the liver stained with alcohol beetroot extract shows light pink stained cytoplasm, poorly stained nuclei with deep brown stain around the central vein, while the HE-stained liver in Figure 4d shows basophilic stained nuclei and eosinophilic cytoplasm.

Fig. 4.

Plate 2: Histology of the kidney and liver stained with aqueous and ethanol beetroot extracts and HE. a–d Magnification ×400. GL, glomerulus; RT, renal tubule; HP, hepatocyte; CV, central vein.

Plate 3 (Fig. 5) shows the histology of large and small intestines stained with aqueous and alcohol beetroot extracts and HE. In Figure 5a, the large intestine stained with aqueous beetroot extract shows brown stained nuclei and cytoplasms in distinct layers comprising the mucous, submucous, muscular, and serosa similar to the deeply stained basophilic nuclei and eosinophilic cytoplasms of the HE-stained large intestine in Figure 5b. In Figure 5c, the small intestine stained with ethanol beetroot extract shows light pink stained nuclei and cytoplasms in the mucous, submucous, muscular, and serosa similar to the deeply stained basophilic nuclei and eosinophilic cytoplasms of the HE-stained small intestine in Figure 5d.

Fig. 5.

Plate 3: Histology of large and small intestines stained with aqueous and ethanol beetroot extracts and HE. a, b Magnification ×100. c, d Magnification ×400. GL, gland; SM, smooth muscle; EPI, epithelium.

Plate 4 (Fig. 6) shows the histology of skin and cardiac muscle stained with ethanol beetroot extract and HE. Distinct epidermis and dermis are observed with skin stained with ethanol beetroot extract in Figure 6a. Deep brown band of epidermal keratin, light pink stained dermis, and brown stained nuclei are seen compared with basophilic nuclei and eosinophilic cytoplasms of HE-stained skin in Figure 6b. Finally, a section of heart in Figure 6c stained with ethanol beetroot extract shows brown stained nuclei and light pink stained cardiac muscle fibers compared with the HE-stained heart which shows prominent cardiac muscle fibers and prominent deeply stained basophilic nuclei in Figure 6d.

Fig. 6.

Plate 4: Histology of skin and cardiac muscle stained with ethanol beetroot extract and HE. a, b Magnification ×100. c, d Magnification ×400. MF, cardiac muscle fiber.

Discussion

The red color of beetroot has drawn several advantages to the beet plant. The betalain pigments responsible for this red color have been used in staining of parasites and ova of nematodes [2, 3, 10]. In this study, the physicochemical and spectrophotometric properties of aqueous and ethanol extracts of red beetroot were determined and adopted in histological staining of various tissues of an albino rat. The betalain concentrations of 381.5 mg/100 g and 253.7 mg/100 g for the aqueous and ethanol extracts, respectively, are within the range of 250–800 mg/100 g reported by Zakharova and Petrova [12].

The aqueous and ethanol extracts of beetroot appeared dark red to red in color and maintained staining ability when stored in a refrigerator at 4°C. This is similar to other reports [10, 13]. Both extracts showed an acidic pH of 5.5 when examined with a pH meter, which is comparable to slightly acidic in [10], pH of 5.2 in [8], and pH 5.4 in [13].

The spectrophotometric curves of the aqueous extract (Fig. 1) and ethanol extract (Fig. 2) of red beetroot showed 3 peaks at 475, 525, and 575 nm. Lillie [14] stated that the presence of more than 1 peak in an absorption curve is an indication of a mixture of more than 1 dye. Each dye in the mixture gives maximum absorption within the range of its complementary color for easy identification. This observation indicates that the extracts have a mixture of 3 pigments, namely yellow betaxanthins (indicaxanthin, the commonest with maximum absorbance at 475 nm); red-purple betacyanin (betanin, the commonest with maximum absorbance at 525 nm); and betanidin with maximum absorbance at 575 nm. This is close to 530 nm reported for betalain [13]. This is also similar to another report [5] which reported a maximum absorbance of near 480, 535, and 542 nm for indicaxanthin, betanin, and betanidin, respectively, using UV-Vis absorption spectrophotometry.

Although the same result was observed for the peak wavelengths for the 3 pigments in the aqueous and ethanol extracts, the absorption curves for both extracts appeared different and this is in agreement with the suggestion by Lillie [14] that the absorption curve of a dye may not be the same in different solvents. Dumbrava et al. [5] also reported different absorption curves for the aqueous and ethanol extracts of red beetroot.

The maximum absorbance was 0.925 for the aqueous extract and 0.615 for ethanol extract at a peak wavelength of 525 nm for each extract. This shows that the concentration of betanin in the aqueous extract is higher than in the ethanol extract. This may be chiefly attributed to the high solubility of betalains in water. This wavelength falls within the range of maximum absorbance of betacyanins of which betanin accounts for 75–95% as observed in [13]. This is, however, contrary to the observation by Dumbrava et al. [5] who reported different peak wavelengths for the aqueous and ethanol extracts.

The mechanism behind the histological staining of different tissues with the beetroot extracts may be attributed to several factors. First, betalains are highly stable due to their chemical compositions. They are nitrogen-containing indoles derived from the amino acid tyrosine [7]. Betalains are vacuolar pigments and obtain their color from the chromophore betalamic acid [5, 15]. Betanidin, the simplest betalain is formed by condensation of cyclo-DOPA with betalamic acid [5]. Betanin (5-O-β-D-glucoside of betanidin) is associated with cyclo-DOPA, and betaxanthin is associated with an amino or an imino compound [15]. Betalains have a functional carboxyl (–COOH) group which reacts with the amino groups of proteins at acidic pH [5].

Second, the histological staining of different tissue structures by betalains of beetroot may be attributed to their physiochemical compositions and spectral properties. The aqueous and ethanol extracts of beetroot had a slightly acidic pH of 5.5 due to the presence of betalamic acid [5], which enabled the staining of basic structures like cytoplasm, nerve fibers, muscle fibers, mucins, keratin, and red blood cells. Betalains have a functional carboxyl (–COOH) group which forms salt with amino, histidine, guanidine (arginine), and citrulline groups of these basic proteins [5]. In the case of keratin, the presence of high sulfur, cysteine plus half cysteine, arginine, and lysine contents is responsible for its prominent demonstration [14]. Also, the majority of nuclei stained pale indicating pH selectivity as nuclei are mostly stained at a pH less than 4.0 as stated by Lillie [14]. This suggests that beetroot may give a better nuclear staining with adequate acidification.

Betalains, particularly betanin (responsible for the red color and the highest concentration in the extracts), have maximum absorbance close to that of eosin (a red synthetic dye) which is between 515 and 518 nm [14]. Thus, the beetroot extracts acted as cytoplasmic stains similar to eosin.

The brown color staining of the beetroot extracts on the tissue structures is similar to that obtained by staining platyhelminths by Kumar et al. [10]. Similar results were reported by Al-mura et al. [3] as brown for scolex, muscle bundles, glycocalyx, calcareous corpuscles and yellow to brown for gravid segments of Taenia species, and elastic tissues of trematodes pink. The brown and pink colors may be attributed to varying reactions with amino groups, principally tyrosine, which is the precursor of betalains [7]. The brown color may also be attributed to the presence of DOPA which gives a brown-black color in tissues [16]. Finally, betanin turns brown in the presence of ammonia and pink in the presence of sodium hydroxide according to Pucher et al. [8]. This nitrogen in betanins may react with the amino groups in the tissue structures to produce this reaction.

Among the tissue structures stained by beetroot, red cells in the central vein of the liver, mucin, and smooth muscle of small and large intestines, and keratin in the epidermis of skin were very prominent. Thus, beetroot can be adopted for staining of these tissue structures.

Conclusion

The aqueous and alcohol beetroot extracts appeared red in color with maximum absorbance at 525 nm with a UV-Vis spectrophotometer. Beetroot dye is stable at 4°C and gave good staining of cytoplasm, muscle fibers, keratin, red blood cells, and mucin but pale nuclear staining. It can be used in histological staining with appropriate modifications.

Statement of Ethics

The rat was handled according to the guidelines of the Animal Ethics Committee, Faculty of Basic Medical Sciences, University of Calabar.

Disclosure Statement

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest. There was no financial support or grant in carrying out this study.

References

- 1.Singnarpi S, Ramani P, Natesan A, Sherlin HJ, Gheena S. Vegetable stain as an alternative to H and E in exfoliative cytology. J Cytol Histol. 2017;8:469. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cheng CW, Suhana MS, Abdullah R. Alternative staining using extracts of hibiscus (Hibiscus rosa-sinnsis L.) and red beet (Beta vulgaris L.) in diagnosing ova of intestinal nematodes (Trichuris trichiura and Ascaris lumbricoides) Eur J Biotech Biosci. 2014;1:14–18. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Al-mura MFA, Hassen ZA, Al-mhanawi BH. Staining technique for helminth parasites by the use of red beet (Beta vulgaris L.) extract. Bas J Vet Res. 2012;11:283–292. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Singh A, Ganesapillai M, Gnanasundaram N. Optimization of extraction of betalain pigments from Beta vulgaris peels by microwave pretreatment. IOP Conf Ser Mater Sci Eng. 2017;263:032004. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dumbrava A, Enache I, Oprea CI, Girtu MA. Toward a more efficient utilization of betalains as pigments for dye-sensitized solar cells. Digest J Nanomat Biost. 2012;7:339–351. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tasneem K, Hage M. Isolation of natural dye from beet root and its application on wool and thread with different mordants at different temperatures. Int J Adv Eng Sci Res. 2016;3:52–62. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bratinova S. European Union JRC Technical Report No. 96974: Provision of scientific and technical support with respect to classification of extracts/concentrates with colouring properties neither as food colours (food additives falling under regulation (EC No 1333/2008) or colouring foods 2015. DOI: 10.2787/608023. pp 1–32. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pucher GW, Curtis LC, Vickery H. The red pigment of the root of the beet (Beta vulgaris) I. The preparation of betanin. J Biol Chem. 1938;123:61–70. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yeniocak M, Goktas O, Colak M, Ozen E, Ugurulu M. Natural colouration of wood material by red beetroot (Beta vulgaris) and determination of colour stability under UV exposure. Maderas Cienc Tecnol. 2015;17:711–722. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kumar N, Mehul J, Das B, Solanki JB. staining of Platyhelminthes by herbal dyes: an ecofriendly technique for the taxonomist. Vet World. 2015;8:1321–1325. doi: 10.14202/vetworld.2015.1321-1325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Das A, De D, Ghosh A, Goswami MM. Improvement in cell imaging by applying a new natural dye from beet root extraction. 2017 https://arxiv.org/pdf/1710.08119.pdf. (accessed March 25, 2018) [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zakharova NS, Petrova TA. Investigation of betalain and betalain oxide in leef beet. Applied Biochem Microbiol. 1997;33:481–484. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Food and Nutrition Paper (FNP) 52 Beet red. Compendium of food additive of the Food and Agriculture Organisation of the United States. 1992 http://www.fao.org/ag/agn/jecfa/additive-052. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lillie RD. ed 9. Baltimore: The Williams and Wilkins Company; 1977. HJ Conn's Biological Stains; pp. pp 340–350. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Castellar R, Obon JM, Alacid M, Fernandez-Lopez JA. Colour properties and stability of Betacyanins from Opuntia fruits. J Agric Food Chem. 2003;51:2772–2776. doi: 10.1021/jf021045h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lyon H, Pigments . A Guide to the Selection and Understanding of Techniques. Berlin: Springer; 1991. Theory and Strategy in Histochemistry; p. p 240. [Google Scholar]