Abstract

Objectives

We evaluated whether the results from portable monitor (PM) devices for the diagnosis of obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), classified into type III and type IV devices by the American Academy of Sleep Medicine, correlated with the results from polysomnography (PSG) testing.

Methods

Sixty-four patients with a sleep-breathing disorder used type III or type IV PM devices at home and were subsequently admitted for testing using PSG. The apnea-hypopnea index (AHI) from each machine was measured, and the AHI component, apnea index (AI), and hypopnea index (HI) were also analyzed.

Results

There was a stronger correlation between the AHI values from PSG testing and those from the type III PM devices (r = 0.92, p < 0.001) than for the data from type IV devices (r = 0.69, p < 0.001). However, the correlation of HI values (type III: r = 0.43, p = 0.024; type IV: r = 0.14, p = 0.41) was poorer than that of the AI values (type III: r = 0.95, p < 0.001; type IV: r = 0.68, p < 0.001). Moreover, the type III PM devices tended to evaluate a patient's condition as less severe than did PSG testing when the AHI value was over 30.

Conclusions

Although type III PM devices outperformed type IV devices as substitutes for PSG, the clinical state must be evaluated for patients suspected of having obstructive sleep apnea.

Keywords: Portable monitor, Out-of-center sleep testing, Obstructive sleep apnea, Polysomnography

What Is It about?

We evaluated whether the results from portable monitor (PM) devices for the diagnosis of obstructive sleep apnea, classified into type III and type IV devices, correlated with the results from polysomnography (PSG) testing. There was a stronger correlation between the apnea-hypopnea index (AHI) values from PSG testing and those from the type III PM devices than for the data from type IV devices. However, the correlation of hypopnea index values was poorer than that of the apnea index values. Moreover, the type III PM devices tended to evaluate a patient's condition as less severe when the AHI value was over 30.

Introduction

Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) affects a large portion of the population [1]. For people between 30 and 60 years of age, the prevalence of OSA is 4% in men and 2% in women [2]. In addition, Heinzer et al. [3] reported that when patients who had diabetes, hypertension, metabolic syndrome, or depression underwent polysomnography (PSG) testing at home, 49.7% of men and 23.4% of women aged ≥40 years had an apnea-hypopnea index (AHI) of ≥15 events per hour according to the American Academy of Sleep Medicine (AASM) 2013 scoring criteria.

Recently, it has been reported that OSA is a risk factor for various diseases, including hypertension [4], cardiovascular disorders [5], diabetes mellitus [6], obesity [7], and stroke [8]. Therefore, it is important to correctly diagnose and treat OSA. As a result, appropriate therapy would not only help prevent these secondary diseases, but also improve worker performance.

PSG testing is considered the gold standard for diagnosing OSA [9]. Although OSA could be diagnosed using PSG with the patient at home, this examination usually requires admission to a hospital or a specialized sleep testing center. Therefore, easy and reliable systems to diagnose OSA have been sought, and several portable monitor (PM) devices have been developed to screen for OSA [10, 11, 12]. PM devices are divided into three classes by the AASM criteria: type II, which has a minimum of seven channels; type III, which has a minimum of four channels; and type IV, which has one or two channels. Using out-of-center sleep testing (OCST), a PM device can be used at home at a reduced cost. The examination is done in a more relaxed and natural environment, compared with that of PSG testing at a hospital. In fact, since 2008, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) in the United States has recommended that PM devices be used for unattended examination at the patient's home to diagnose some OSA cases [13]. Moreover, the International Classification of Sleep Disorders (ed. 3) equated the results of OCST using PM devices with those from PSG testing in 2014 [14]. The Japanese Society of Sleep Research has also allowed the limited use of PM devices instead of PSG testing to diagnose OSA [15]. However, research on which types of PM devices have the best accuracy and correlation with PSG testing is limited [16].

Therefore, in this study we compared the correlation between type III and type IV PM devices with PSG, and evaluated the reliability of these two types of PM devices.

Material and Methods

Subjects

Between April 2011 and March 2016, we evaluated 64 patients at Nishinihon Hospital who exhibited loud snoring or sleep apnea, but had not been diagnosed with central sleep apnea. All patients underwent PM monitoring at home (type III PM, n = 28; type IV PM: n = 36) and were subsequently tested with PSG in a hospital on another occasion. Further clinical information on these patients is shown in Table 1. Informed consent was obtained from these patients for participation in this study, all experiments using humans were conducted in accordance with The Declaration of Helsinki, and the study received approval of the Institutional Review Board of Nishinihon Hospital (Permit No. H28-1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of patients assigned type III or type IV PM devices

| Type III (n = 28) | Type IV (n = 36) | p value type III vs. type IV | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 59.00 (50.25, 68.25) | 55.50 (44.25, 72.50) | 0.56 |

| Male, n (%) | 21 (75.00) | 30 (83.30) | 0.53 |

| Time interval | 27 (21.75, 39.25) | 29 (18.75, 42.25) | 0.93 |

| AHI (PM) | 21.15 (16.95, 40.42) | 32.55 (17.58, 46.32) | 0.18 |

| AHI (PSG) | 29.40 (20.35, 49.72) | 37.20 (21.45, 53.32) | 0.55 |

| AI (PM) | 12.90 (5.75, 19.80) | 24.10 (13.28, 40.02) | 0.003 |

| AI (PSG) | 15.10 (5.68, 29.32) | 20.15 (6.85, 38.50) | 0.85 |

| HI (PM) | 9.75 (6.13, 15.53) | 3.20 (1.70, 5.08) | <0.001 |

| HI (PSG) | 9.05 (4.55, 20.55) | 10.95 (6.63, 15.50) | 0.48 |

Values given as the median (interquartile range), unless otherwise indicated. Time interval represents the duration in days between portable monitor diagnosis (type III or type IV) and PSG testing. AHI, apnea-hypopnea index; AI, apnea index; HI, hypopnea index; PM, portable monitor; PSG, polysomnography.

Portable Monitor Devices and Polysomnography

We used an AASM guided Smart Watch PMP-300E (Fuji-Respironics Inc., Japan) as the type III PM device, and a SAS-2100 (Teijin Inc., Japan) as the type IV PM device (Table 2). After reading the manual or receiving instructions from a technologist on sensor operation, patients wore a PM device at home by themselves for one night. All of the patients were able to perform the examination. The results from the type III PM devices were analyzed by experienced technicians and the type IV PM devices were capable of performing automatic analysis of the results. With PM devices, apnea and hypopnea are diagnosed according to the guidelines of the AASM released in 2007 [17]. Briefly, apnea was identified when both of the following criteria were met: there was a drop in the peak signal excursion by at least 90% of the pre-event baseline, and the duration of this drop was at least 10 s. Hypopnea was diagnosed when all of the following criteria were met: the peak signal excursions dropped by at least 50% of the pre-event baseline, the duration of this drop was at least 10 s, and there was at least 3% oxygen desaturation from the pre-event baseline or the event was associated with arousal.

Table 2.

Parameters measured with PSG and type III or type IV PM devices

| Parameter | PSG | PMP-300E (type III PM device) |

SAS-2100 (type IV PM device) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Electroencephalogram | + | – | – |

| Electrooculogram | + | – | – |

| Electromyogram submentalis | + | – | – |

| Electrocardiogram or pulse rate | + | + | + |

| Air flow | |||

| Oronasal thermal sensor | + | – | – |

| Nasal pressure transducer | + | + | + |

| Respiratory effort | |||

| Piezo sensor | + | – | – |

| G sensor | – | + | – |

| Pulse oximeter | + | + | + |

| Body position | + | + | – |

| Electromyogram anterior tibialis | + | – | – |

PSG, polysomnography; PM, portable monitor.

After evaluation with a PM monitor, the patients underwent PSG testing in our hospital on another night. During this interval between use of the PM devices and PSG testing, the patients remained on the same therapy regimen, with no change in the medications. In addition, they experienced no dramatic weight changes. The PSG system (Sleep Watcher E series®, Teijin Inc., Japan) included an electroencephalogram; an electrooculogram; an electromyogram submentalis; an electromyogram bilateral tibial; an electrocardiogram; and recorded thoracic and abdominal exertion, oxyhemoglobin saturation, body position, and snoring channels (Table 2). Clinical technologists manually scored the sleep stages and respiratory events from all PSG recordings, and apnea or hypopnea was diagnosed according to the AASM 2007 [17] guidelines.

The apnea index (AI) records the number of apnea events per hour, and the hypopnea index (HI) is the number of hypopnea events per hour. The AHI is calculated by adding the AI and HI values. Finally, the patients were diagnosed with OSA if they had an AHI of at least 5.

Statistical Analysis

Our cross-sectional study used a sample size determined by considering the number of outpatients attending Nishinihon Hospital during the survey period. Our data did not have missing values. For the univariate analysis, Wilcoxon rank-sum tests were used for the continuous variables. For categorical variables, Fisher exact tests were performed. The coefficient of determination and Pearson correlation coefficient were evaluated to confirm the relation between the results of each PM device and PSG testing. Pearson partial correlation coefficients were also evaluated, taking into consideration the patient's age and the time interval between use of the PM device and PSG testing. In addition, to check for bias between the results of the two PM devices and PSG testing, Bland-Altman plots were used. These analyses were performed using EZR (Saitama Medical Center, Jichi Medical University, Saitama, Japan), which is a graphical user interface for R (The R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria), and the level of statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

Results

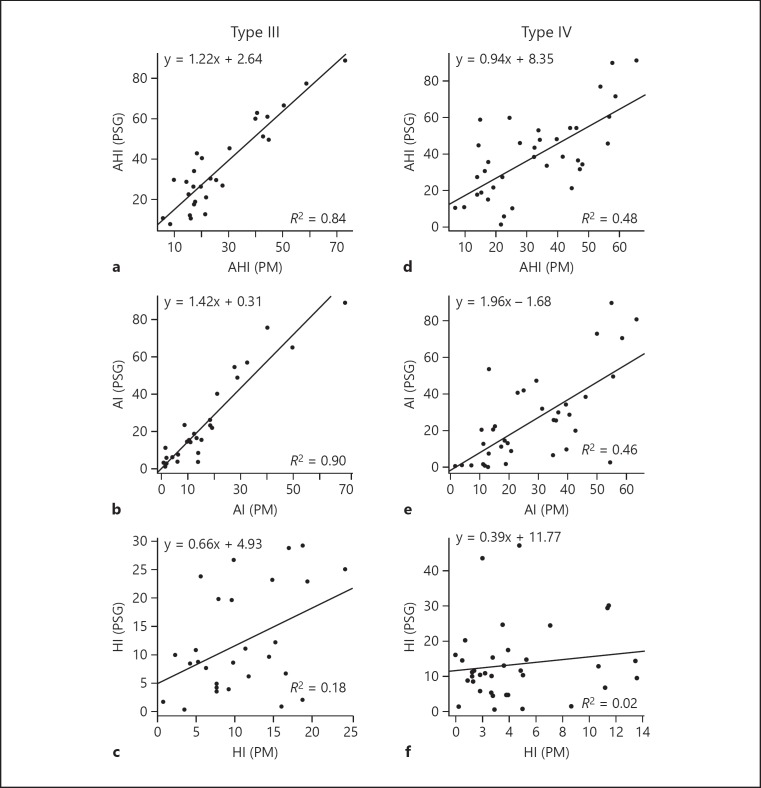

We investigated the Pearson correlation coefficients of AHI between type III and type IV PM devices with PSG (Table 3). For the AHI value, the correlation coefficients were 0.92 (p < 0.001) for the type III PM devices and 0.69 (p < 0.001) for the type IV PM devices. The coefficient of determination was 0.84 for the type III PM devices and 0.48 for the type IV PM devices. Next, we checked the AI and HI values, the components of AHI, and the results were as follows: for the AI values between the type III PM device and PSG testing, the Pearson correlation coefficient was 0.95 (p < 0.001) and the coefficient of determination was 0.90. For the type IV device, these values were 0.68 (p < 0.001) and 0.46, respectively. The HI value between the type III PM devices and PSG testing had a Pearson correlation coefficient of 0.43 (p = 0.024) and a coefficient of determination of 0.18. For the type IV PM devices, the values were 0.14 (p = 0.41) and 0.02, respectively (Table 4; Fig. 1a–f). To remove the influence of variables that could affect the relation between the PM devices and PSG testing, we examined the Pearson partial correlation coefficients, taking into consideration the patient's age and the time interval between use of the PM device and PSG testing. Similar results were obtained: type III PM device and PSG testing: AHI (r = 0.92, p < 0.001), AI (r = 0.94, p < 0.001), HI (r = 0.46, p = 0.017); type IV PM device and PSG testing: AHI (r = 0.68, p < 0.001), AI (r = 0.69, p < 0.001), HI (r = 0.13, p = 0.47).

Table 3.

Pearson correlation coefficients for type III and type IV PM devices

| AHI (PM) | AHI (PSG) | AI (PM) | AI (PSG) | HI (PM) | HI (PSG) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Correlation between type III PM devices and PSG testing | ||||||

| AHI (PM) | 1.00 | 0.92 | 0.93 | 0.94 | 0.22 | – 0.32 |

| AHI (PSG) | 0.92 | 1.00 | 0.85 | 0.92 | 0.2 | – 0.08 |

| AI (PM) | 0.93 | 0.85 | 1.00 | 0.95 | – 0.15 | – 0.48 |

| AI (PSG) | 0.94 | 0.92 | 0.95 | 1.00 | 0.01 | – 0.46 |

| HI (PM) | 0.22 | 0.2 | – 0.15 | 0.01 | 1.00 | 0.43 |

| HI (PSG) | – 0.32 | – 0.08 | – 0.48 | – 0.46 | 0.43 | 1.00 |

| Correlation between type IV PM devices and PSG testing | ||||||

| AHI (PM) | 1.00 | 0.69 | 0.97 | 0.63 | – 0.07 | 0.02 |

| AHI (PSG) | 0.69 | 1.00 | 0.73 | 0.9 | – 0.31 | 0.05 |

| AI (PM) | 0.97 | 0.73 | 1.00 | 0.68 | – 0.3 | – 0.02 |

| AI (PSG) | 0.63 | 0.9 | 0.68 | 1.00 | – 0.35 | – 0.39 |

| HI (PM) | – 0.07 | – 0.31 | – 0.3 | – 0.35 | 1.00 | 0.14 |

| HI (PSG) | 0.02 | 0.05 | – 0.02 | – 0.39 | 0.14 | 1.00 |

AHI (PM), AI (PM), and HI (PM) manifested the result of type III or type IV PM devices; AHI (PSG), AI (PSG), and HI (PSG) manifested the result of PSG. AHI, apnea-hypopnea index; AI, apnea index; HI, hypopnea index; PM, portable monitor; PSG, polysomnography.

Table 4.

AHI, AI, and HI characteristics as a Brand-Altman Plot

| Type III PM device | Type IV PM device | |

|---|---|---|

| AHI (PM) – AHI (PSG) | ||

| Lower limit line | – 26.67 (– 32.88, – 20.45) | – 38.07 (– 47.57, – 28.57) |

| Mean difference | – 8.52 (– 12.11, – 4.93) | – 6.29 (– 11.78, – 0.81) |

| Upper limit line | 9.62 (3.40, 15.84) | 25.48 (15.98, 34.98) |

| AI (PM) – AI (PSG) | ||

| Lower limit line | – 27.54 (– 34.49, – 20.59) | – 32.15 (– 42.59, – 21.71) |

| Mean difference | – 7.26 (– 11.27, – 3.25) | 2.76 (– 3.27, 8.79) |

| Upper limit line | 13.02 (6.07, 19.97) | 37.67 (27.23, 48.10) |

| HI (PM) – HI (PSG) | ||

| Lower limit line | – 18.19 (– 24.00, – 12.39) | – 30.40 (– 36.78, – 24.02) |

| Mean difference | – 1.26 (– 4.61, 2.09) | – 9.06 (– 12.74, – 5.37) |

| Upper limit line | 15.67 (9.87, 21.47) | 12.29 (5.91, 18.67) |

Values as given as means (confidence interval). AHI (PM), AI (PM), and HI (PM) show the results from type III or type IV PM devices; AHI (PSG), AI (PSG), and HI (PSG) show the results of PSG testing. AHI, apnea-hypopnea index; AI, apnea index; HI, hypopnea index; PM, portable monitor; PSG, polysomnography.

Fig. 1.

Linear regression plot with AHI, AI, and HI values for the type III and type IV PM devices, along with AHI, AI, and HI values from PSG testing. The solid line indicates the linear regression. The regression equation and R2 (coefficient of determination) are also displayed. AHI, apnea-hypopnea index; AI, apnea index; HI, hypopnea index; PSG, polysomnography; PM, portable monitor.

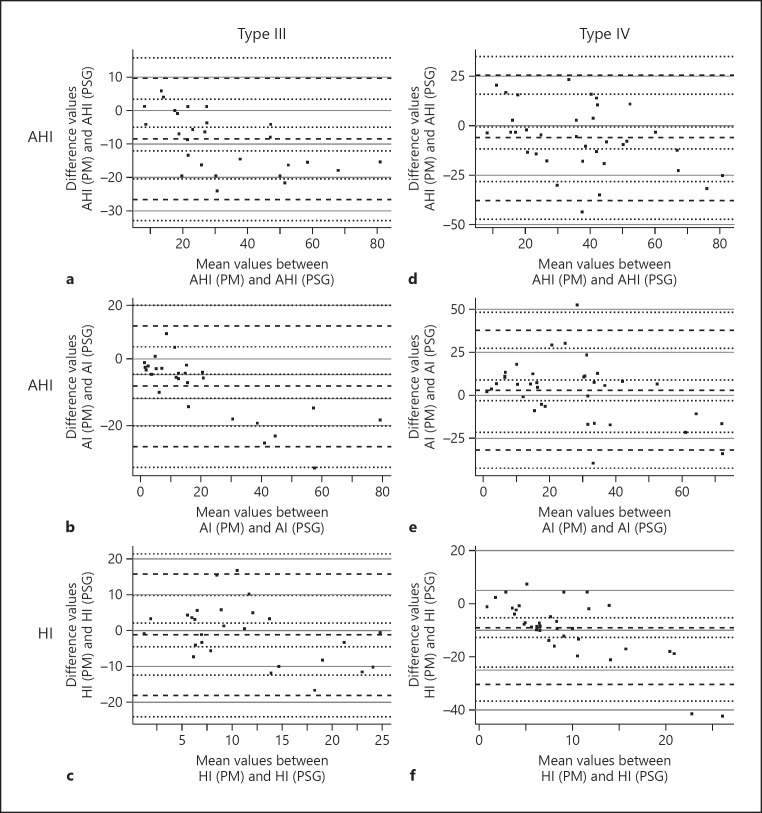

To verify that a specific bias existed in the relation between the two PM devices and PSG, we performed a Bland-Altman analysis (Fig. 2; Table 4). When the AHI score was over 30, the type III PM devices had a tendency to assess the patient's condition as less severe compared with PSG testing (Fig. 2a). The AI and HI values in the type III PM devices also showed the same tendency (Fig. 2c, e). Conversely, there was no obvious bias in the type IV PM devices (Fig. 2d, f). However, the 95% confidence intervals for all components were narrower for the type III PM devices than those for the type IV PM devices (Fig. 2; Table 4).

Fig. 2.

Bland-Altman plot for AHI, AI, and HI values from the type III or type IV PM devices, along with AHI, AI, and HI values from PSG testing. The heavy dashed lines represent the mean values and 2 standard deviations above and below the differences between AHI, AI, and HI values from the PM devices and those from PSG testing, respectively. Light dashed lines represent the 95% confidence intervals with each heavy dashed line. AHI (a), AI (b), and HI (c) values for type III PM devices and PSG testing. The AHI (e), AI (f), and HI (g) values are for type IV PM devices and PSG testing. The AHI (PM), AI (PM), and HI (PM) values show the results of type III or type IV PM devices; the AHI (PSG), AI (PSG), and HI (PSG) values show the result of PSG testing.

Discussion

In the current study, we verified the relationship between PSG testing and two PM devices. We found a stronger correlation for the AHI values from type III PM devices compared with those from type IV PM devices. Generally, type III PM devices monitored air flow, blood oxygenation, body position, movement, and respiratory effects. In contrast, the type IV PM devices monitored only air flow and blood oxygenation. Therefore, the larger correlation between the type III PM devices and PSG testing may reflect the number of monitoring channels. However, the HI component of the AHI value showed poor correlation for both type III and type IV PM devices. While PSG testing uses two airflow sensors, an oronasal thermal sensor, and a nasal pressure transducer, the two PM devices examined here only had nasal pressure transducers. Moreover, the sensitivity for hypopnea with the nasal pressure transducers of the two PM devices was lower than that of PSG testing because of the lower sampling rate [17, 18]. Yagi et al. [19] reported that the correlation of HI between PSG testing and the Apnomonitor 5®, which is a type III PM device was poor compared with the correlation of HI because of the different sensitivity of the oronasal thermistors for detecting airflow. Therefore, the low HI correlation in our study between the two PM devices and PSG testing may also have been affected by the sensitivity for hypopnea.

Next, we created a Bland-Altman plot to check whether a specific bias existed between the results of PSG testing and the two PM devices [20]. With the type III device, when the AHI, AI, and HI values were under 30, 20, and 15, respectively, there was no specific bias. However, when the values were larger, the type III PM devices had a tendency to assess the condition less severely compared with PSG testing. However, the type IV PM devices did not show this tendency, or any other specific bias. Although our study did not test the PM device and perform PSG on the same night, it has been reported that AHI values from type III PM devices are lower than those obtained with PSG testing on the same night in patients with severe OSA [21]. Moreover, the discrepancy in the AHI values between the type III and type IV devices and PSG testing seen in the Bland-Altman plot has also been reported in severe SAS patients [16], and these reports are consistent with the results of our study. Although the tendency of the type III PM devices is to underrate the clinical state of OSA patients, the 95% confidence intervals for the AHI, AI, and HI values in the Brand-Altman plot were in a narrower range compared with those for the type IV PM devices. In addition, the correlation between the type IV PM devices and PSG testing was inferior to that of the type III PM devices. Therefore, type III PM devices may become central to the screening for and diagnosis of OSA.

In Japan's national health care insurance system, additional intervention is not permitted if the AHI value is less than 5 for the OCST according to PM devices. When the AHI values in OCST are over 40, continuous positive airway pressure, which is the therapy for OSA, is indicated even without PSG testing [15]. We should pay attention to the possibility that type III PM devices underestimate the clinical state of severe OSA patients. When the AHI values are in the range of 5 to 40 according to OCST, PSG testing requires admission to a hospital, which is associated with much larger costs. However, our study indicated that accurate diagnosis of OSA by a type III PM device remains difficult because of its low sensitivity for hypopnea. Therefore, re-examination by PSG testing may be important for a precise evaluation of patients with suspected OSA.

Our study has the following limitations. First, PM devices and PSG were not tested on the same night, as already described. We tried to reduce specific bias by using Pearson partial correlation coefficients. However, each device's results may differ from day to day because of patient-related daily variations (e.g., body position, degree of sleep, physical condition). Therefore, if the proportion of patients who had position- or REM-dependent OSA in our study was high, the possibility that the results of the PM devices and PSG would display a discrepancy could not be denied. Second, the patients given a type III PM device were different from those given a type IV PM device. Therefore, although the baseline characteristics of the patients in these two groups were similar, this difference may have partially affected the relationship between PM devices and PSG. Third, the patient sample was small. For all these reasons, prospective studies are needed to verify the diagnostic accuracy of the two PM devices.

Conclusion

We verified the correlation between two PM devices and PSG testing. By applying the classification system from the AASM, we found a strong correlation between the AHI values from PSG testing and those from a type III PM device, but not from a type IV PM device. However, both PM devices showed poor correlation for the HI component of AHI. Moreover, the type III PM devices tended to underestimate the clinical severity of OSA patients. Although PM devices, especially type III PM devices, will be increasingly used instead of PSG testing, the results of PM devices need to be assessed. OSA should then be diagnosed with an understanding of the characteristics and limitations of these devices.

Disclosure Statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. Yumi Hirata (Seven Dreamers Laboratories, Inc.) for technical advice. We also thank Ms. Fukiko Nishizaka and Ms. Nobuko Furushou, along with the other staff members of the physiological laboratory at Nishinihon Hospital for their technical help. We also thank Louis R. Nemzer, PhD, from Edanz Group (www.edanzediting.com/ac) for editing the manuscript.

References

- 1.Young T, Palta M, Dempsey J, Skatrud J, Weber S, Badr S. The occurrence of sleep-disordered breathing among middle-aged adults. N Engl J Med. 1993;328:1230–1235. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199304293281704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nieto FJ, Young TB, Lind BK, Shahar E, Samet JM, Redline S, D'Agostino RB, Newman AB, Lebowitz MD, Pickering TG. Association of sleep-disordered breathing, sleep apnea, and hypertension in a large community-based study. Sleep Heart Health Study. JAMA. 2000;283:1829–1836. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.14.1829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Heinzer R, Vat S, Marques-Vidal P, Marti-Soler H, Andries D, Tobback N, Mooser V, Preisig M, Malhotra A, Waeber G, Vollenweider P, Tafti M, Haba-Rubio J. Prevalence of sleep-disordered breathing in the general population: the HypnoLaus study. Lancet Respir Med. 2015;3:310–318. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(15)00043-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Peppard PE, Young T, Palta M, Skatrud J. Prospective study of the association between sleep-disordered breathing and hypertension. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:1378–1384. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200005113421901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hung J, Whitford EG, Parsons RW, Hillman DR. Association of sleep apnoea with myocardial infarction in men. Lancet. 1990;336:261–264. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(90)91799-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vale J, Manuel P, Oliveira E, Silva E, Melo V, Sousa M, Alelxandre JC, Gil I, Sanchez A, Nascimento E, Tores AS. Obstructive sleep apnea and diabetes mellitus. Rev Port Pneumol. 2006;21:55–60. doi: 10.1016/j.rppnen.2014.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Peppard PE, Young T, Barnet JH, Palta M, Hagen EW, Hla KM. Increased prevalence of sleep-disordered breathing in adults. Am J Epidemiol. 2013;177:1006–1014. doi: 10.1093/aje/kws342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Palomäki H, Partinen M, Erkinjuntti T, Kaste M. Snoring, sleep apnea syndrome, and stroke. Neurology. 1992;42:75–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chesson AL, Berry RB, Pack A. Practice parameters for the use of portable monitoring devices in the investigation of suspected obstructive sleep apnea in adults. Sleep. 2003;26:907–913. doi: 10.1093/sleep/26.7.907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.White DP, Gibb TJ, Wall JM, Westbrook PR. Assessment of accuracy and analysis time of a novel device to monitor sleep and breathing in the home. Sleep. 1995;18:115–126. doi: 10.1093/sleep/18.2.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Man GC, Kang BV. Validation of a portable sleep apnea monitoring device. Chest. 1995;108:388–393. doi: 10.1378/chest.108.2.388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ryan PJ, Hilton MF, Boldy DA, Evans A, Bradbury S, Sapiano S, et al. Validation of British Thoracic Society guidelines for the diagnosis of the sleep apnoea/hypopnoea syndrome: can polysomnography be avoided? Thorax. 1995;50:972–975. doi: 10.1136/thx.50.9.972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Collop NA, Anderson WM, Boehlecke B, Claman D, Goldberg R, Gottlieb DJ, et al. Clinical guidelines for the use of unattended portable monitors in the diagnosis of obstructive sleep apnea in adult patients. Portable Monitoring Task Force of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine. J Clin Sleep Med. 2007;15:737–747. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Daren IL. ed 3. Darien: American Academy of Sleep Medicine; 2014. American Academy of Sleep Medicine: International Classification of Sleep Disorders; pp. pp 53–62. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sasanabe R, Shiomi T. The point of the diagnosis, treatment and connection guidelines of the sleep disordered breathing. Nippon Rinsho. 2013;71:349–355. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Calleja JM, Esnaola S, Rubio JD. Comparison of a cardiorespiratory device versus polysomnography for diagnosis of sleep apnoea. Eur Respir J. 2002;20:1505–1510. doi: 10.1183/09031936.02.00297402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.The AASM Manual for the Scoring of Sleep and Associated Events Rules, Terminology and Technical Specifications. Chicago, American Academy of Sleep Medicine. 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 18.Berry RB, Brooks R, Gamaldo CE, Harding SM, Marcus CL, Vaughn BV, et al. The AASM Manual for the Scoring of Sleep and Associated Events Rules, Terminology and Technical Specifications. Version 2.0. Darien, American Academy of Sleep Medicine. 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yagi H, Nakata S, Tsuge H, Yasuma F, Noda A, Morinaga M, et al. Significance of a screening device (Apnomonitor 5) for sleep apnea syndrome. Auris Nasus Larynx. 2009;36:176–180. doi: 10.1016/j.anl.2008.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Atkinson G, Nevill AM. Statistical methods for assessing measurement error (reliability) in variables relevant to sports medicine. Sports Med. 1998;26:217–238. doi: 10.2165/00007256-199826040-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Flemons WW, Littner MR, Rowley JA, Gay P, Anderson WM, Hudgel DW, et al. Home diagnosis of sleep apnea: a systematic review of the literature. An evidence review cosponsored by the American Academy of Sleep Medicine, the American College of Chest Physicians, and the American Thoracic Society. Chest. 2003;124:1543. doi: 10.1378/chest.124.4.1543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]