Abstract

Background.

The need for earlier recognition of children at risk for neurobehavioral problems associated with prenatal ethanol exposure (PAE) has prompted investigations of biomarkers prognostic for altered fetal development. Here, we examined whether PAE alters the expression of these proteins in human placenta, along with other angiogenesis-related proteins and cytokines in subjects selected from an ENRICH prospective cohort.

Methods.

PAE was ascertained by screening questionnaires, Time-line Follow-back interviews and a panel of ethanol biomarkers at two study visits. After delivery, placental tissue samples were collected for protein analysis.

Results.

No significant differences in the prevalence of substance use, demographic or medical characteristics were observed between the No PAE and PAE groups. PAE was associated with significant reductions in placental expression of VEGFR2 and Annexin-A4, while the levels of VEGFR1 and CCM-3 trended downward. A trend towards higher expression of the cytokines TNF-α and IL-13 was also observed in the PAE group. ROC analyses of the data demonstrated a moderate-to-high degree of diagnostic accuracy for individual placental proteins. Combinations of proteins substantially increased their ability to differentiate between PAE and No PAE subjects.

Conclusions.

These results establish the feasibility of harvesting placental tissue for protein analyses of PAE in a prospective manner. In addition, given the importance of vascular remodeling in both placenta and developing brain, the role of angiogenic and cytokine proteins in this process warrants further investigation for their utility for predicting alterations in brain development, as well as their mechanistic role in PAE-induced pathology.

Keywords: Angiogenesis, Annexin-A4, Cytokines, Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder, Placenta, Prenatal Alcohol Exposure, Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor Receptor 2

INTRODUCTION

It is well-established that alcohol consumption during pregnancy can cause long-term impairments in cognitive function of affected offspring, even in the absence of the physical abnormalities associated with Fetal Alcohol Syndrome (Abel, 1984; Conry, 1990; Hanson, Streissguth, & Smith, 1978; Shaywitz, Cohen, & Shaywitz, 1980; Streissguth, Barr, & Sampson, 1990). However, most prenatal alcohol exposure (PAE)-affected children present with no evidence of functional brain damage. In such cases, the adverse neurobehavioral consequences associated with PAE may not be recognized until much later in development, if ever, thus diminishing the prospect for recognizing causal factors and delaying opportunities for earlier interventions. As such, one critical clinical challenge is to develop more sensitive and reliable methods to predict the functional consequences of PAE. In particular, there is a need to identify prognostic markers of prenatal alcohol effects, easily assessed early in development, to allow for earlier identification of children at risk for longer-term adverse neurobehavioral outcomes.

Over the past decade, one approach for developing biomarkers prognostic of PAE-induced damage has been the identification of novel biochemical species in biomarker tissue sources that are altered by PAE in a manner that would predict functional damage to the fetus. Various biochemical species and processes have been examined either in animal models of PAE or in clinical populations using high-throughput screening procedures such as DNA methylation profiles (Lussier et al., 2018), mRNA expression profiles (Carter et al., 2018; Downing et al., 2012; Rosenberg et al., 2010) miRNA expression profiles (Balaraman et al., 2014; Balaraman et al., 2016; Gardiner et al., 2016) and proteomic approaches (Datta et al., 2008; Davis-Anderson et al., 2017; Ramadoss & Magness, 2012). However, to date, a strategy to identify candidate biomarkers in animal models of PAE that can be related to specific neurobiological consequences and, subsequently, examine these same biomarker candidates in a clinical population has yet to be reported.

Gonzalez, Savage and colleagues have examined the impact of PAE on the expression of angiogenesis-related proteins in placenta and fetal brain as a strategy to facilitate the identification of novel biomarkers that may be prognostic of functional brain damage associated with PAE in children. Using a mouse model of PAE, Lecuyer et al. (2017) observed significant reductions in the expression of placental growth factor (PLGF), and vascular endothelial growth factor receptors (VEGFR1) and (VEGFR2) in placenta at term. These reductions were associated with diminished placental vascular density, as well as reduced fetal cerebral cortical VEGFR1 levels and cerebral microvascular density. Using our rat model of voluntary moderate alcohol consumption during pregnancy, we observed PAE-induced alterations in two placental proteins, namely, Annexin-A4 (ANX-A4) and Cerebral Cavernous Malformation Protein 3 (CCM-3) (Gonzalez et al., in revision). Relative to their potential utility as biomarkers of PAE-induced damage, ANX-A4, which has been associated with alcohol-induced neurotoxicity (Ohkawa et al., 2002; Sohma, Ohkawa, Hashimoto, Sakai, & Saito, 2002; Sohma et al., 2001), was elevated in both rat placenta as well as rat fetal cerebral cortex. CCM-3, which stabilizes the expression and function of VEFGR2 receptors in vascular endothelial cells (He et al., 2010; Louvi, Nishimura, & Gunel, 2014), was reduced in both rat placenta and rat fetal cerebral cortex. The reduction of CCM-3 was associated with reduced cerebral cortical VEGFR2 receptor density as well as reductions in microvascular density (Gonzalez et al., in revision). Collectively, these results suggested that ethanol-induced alterations in placental protein expression may have some utility for predicting PAE-induced alterations in fetal angiogenesis and neurodevelopment.

In the present study, as a follow-up to these preclinical observations, we examined whether these placental protein alterations might also be detected in human placenta. Using samples obtained from a well-established ENRICH cohort (Bakhireva, Lowe, Gutierrez, & Stephen, 2015), we examined placental expression of ANX-A4, CCM-3 and VEGFR2 along with expression of VEGFR1 and five other angiogenesis-related proteins. In addition to angiogenesis-related proteins, alcohol consumption alters cytokine expression in placenta (Svinarich, DiCerbo, Zaher, Yelian, & Gonik, 1998; Terasaki & Schwarz, 2016) as well as in the fetus (Ahluwalia et al., 2000). Cytokines can also influence angiogenesis (Meng et al., 2016; Zhao, Kalish, Wong, & Stevenson, 2018). For these reasons, we also examined the effects of PAE on the expression of six pro-inflammatory cytokines and four anti-inflammatory cytokines using a Meso Scale array assays.

MATERIALS and METHODS

Description of the Parent ENRICH Cohort.

This study utilized data from a subset of participants enrolled into the Ethanol, Neurodevelopment, Infant and Child Health (ENRICH) prospective cohort at the University of New Mexico (UNM). ENRICH has been approved by the UNM Human Research Review Committee (UNM HRRC #12-390). A separate feasibility study of placental protein stability, using de-identified placenta specimens obtained at UNM hospital, which were not part of the ENRICH cohort, was approved as an exemption under Title 45 CFR §46.101. A more detailed description of the ENRICH study methodology is described elsewhere (Bakhireva et al., 2015). Briefly, study participants were recruited from UNM prenatal clinics that provide care to women with substance abuse disorder, general obstetrics clinics and specialty care clinics. The eligibility criteria for the parent cohort were: 1) a singleton pregnancy, 2) gestational age less than 35 weeks at enrollment, 3) the ability to provide written informed consent in English, 4) delivery at UNM hospital and 5) planning to stay in the greater Albuquerque area for the next two years. The ENRICH cohort includes four study visits: Prenatal (Visit 1), at delivery / hospital stay after delivery (Visit 2), neurodevelopmental evaluations of the child at 6 months of age (Visit 3), and neurodevelopmental evaluation at 20 months (Visit 4). To account for the effect of social environment on neurodevelopmental outcomes, the ENRICH cohort includes subjects with opioid use disorder who receive medication assisted therapy (MAT) with methadone or buprenorphine. Thus, the parent cohort includes four study groups: PAE, MAT, PAE+MAT, and healthy controls.

At Visit 1, a structured maternal interview collected detailed information on: 1) demographics (maternal age, gestational age at enrollment, ethnicity, race, educational status, insurance, employment status), 2) medical / reproductive health (pre-pregnancy BMI, chronic medical conditions, pregnancy related complications, use of medications) and, 3) alcohol and other forms of substance use (based on self-report and alcohol biomarkers) during the periconceptional period (one month around the last menstrual period) and during pregnancy. At Visit 2, changes in alcohol consumption patterns were ascertained and information on perinatal outcomes was abstracted from medical records.

Assessment of PAE.

Alcohol use was assessed via alcohol screening questionnaires (AUDIT, TWEAK), and repeated prospective Time-line Follow-back (TLFB) interviews which captured alcohol use around the last menstrual period (TLFB1), 30 days before Visit 1 (TLFB2), 30 days before Visit 2 (TLFB3), as well as alcohol use on “special occasions”. In addition, PAE was confirmed by a panel of alcohol biomarkers: maternal serum gamma-glutamyltransferase (GGT), carbohydrate-deficient transferrin (%dCDT), phosphatidylethanol (PEth), urinary ethyl glucuronide (uEtG) and urinary ethyl sulfate (uEtS), as well as PEth in dried blood spot card (PEth-DBS) obtained from newborns.

Selection of Subjects into Placental Protein Study.

For purposes of the present study, data from the first two ENRICH visits (V1, V2) were utilized. Subjects with PAE (PAE or PAE+MAT) were grouped together and compared to No PAE subjects (MAT and unexposed controls). From the ENRICH cohort, a subset of PAE subjects who met one or more of the following eligibility criteria (regardless of co-exposure with MAT) were selected: 1) an AUDIT score ≥ 8, 2) a total consumption of ≥ 84 drinks during pregnancy (equivalent to at least 7 drinks/week captured by three repeated 4-week TLFB calendars) or 3) a positive test on one or more of the ethanol biomarkers. The following additional exclusionary criteria were applied for purposes of the placental protein study: 1) evidence of placental insufficiency, 2) any placental or umbilical cord abnormalities, 3) maternal diabetes or chorioamnionitis, 4) gestational age at delivery less than 37 weeks. A total of 30 subjects were initially selected that met the eligibility criteria for this study. The placental tissue homogenate preparations from four subjects (two in each group) were noted to be darker in color, likely due to excessive blood contamination of samples, which resulted in spuriously low Western blot data and spuriously high ELISA measures, particularly for the cytokine proteins. These results were considered outliers and removed from the study. Thus, 26 subjects (13 pairs of samples) were included in the final analyses.

Placental Tissue Collection.

Placental core samples were collected, usually within two hours after delivery, though three No PAE and two PAE samples were processed between four and eight hours after delivery. In cases where samples could not be collected immediately, the placenta was refrigerated (at 4 °C) until a study team member could arrive at the hospital to process it. Samples were obtained by grasping the center of a cotyledon with a Pennington clamp to stabilize the tissue, and using a #5 cork borer (1 cm diameter) to obtain full-thickness biopsies. The samples were rinsed in ice-cold saline and blotted to remove excess blood, then placed in a polypropylene tube, flash frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80 °C until analysis.

Using the same tissue collection methodology described above, a preliminary placental protein stability study was conducted for two placental proteins using four samples (2 C-section and 2 vaginally-delivered) that were not part of the ENRICH cohort. Time-zero samples were collected immediately after delivery, rinsed and quickly frozen. These placentae were stored a 4 °C and additional samples collected, rinsed and frozen at six subsequent time points; 1, 2, 4, 8, 12 and 24 hours after delivery.

Western Blotting Procedures.

Protein samples were run in pairs, with two PAE and two No PAE tissue samples thawed and then homogenized in 40 mM Tris pH 8.5 with 1% SDS and protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche), using a Polytron homogenizer (Kinematica, Luzern, Switzerland). The samples were then sonicated at 30 Hz, followed by centrifugation at 14,100 x g at 4 °C for 5 min. The supernatant was then removed, frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80 °C until used for Western blot Analysis. The proteins were quantified using the Pierce BCA Protein Assay Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

For Annexin-A4 (ANX-A4) and Cerebral Cavernous Malformation Protein 3 (CCM-3), 50 μg of protein were loaded into each well of a pre-made 12% SDS polyacrylamide gel and run at 150 volts for 1 hour at room temperature (RT). For Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor Receptor 2 (VEGFR2), 100 μg of protein was used and run on a 7.5% polyacrylamide gel at 120 volts for 2 hours. The proteins were then transferred to a PVDF membrane at 100 volts for 1 hour. Following transfer, the membrane was washed in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) for 5 minutes, followed by blocking with a blocking buffer (LI-COR Biosciences, Lincoln, NE) for one hour at RT. The membranes were then incubated in a solution of blocking buffer, 0.1% Tween-20 along with the primary antibodies: ANX-A4 1:5000 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, TX), CCM-3 1:200 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), or VEGFR2 1:1000 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), as well as β-Actin antibodies at 1:5000 for CCM3 and ANX-A4 (Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA), and at 1:40,000 for VEGFR2 (Sigma-Aldrich Corp, St. Louis, MO) were used. The membranes were incubated overnight at 4 °C for 19 hours (CCM-3 and ANX-A4) or 17.5 hours (VEGFR2). The membranes were rinsed in PBS-Tween 3 x 10 minutes, incubated in the secondary antibodies for the protein of interest at 1:25,000 (LI-COR) and for actin, 1:15,000 (LI-COR), along with blocking buffer, 0.1% Tween-20, and 0.01% SDS for 2 hours at RT. Finally, the membranes were washed 3 x 10 minutes in PBS-Tween, and once more in PBS for 10 minutes. The membranes were scanned and analyzed with the Odyssey Infrared Imaging System (LI-COR) at 700 and 800 nm. The optical densities of the proteins of interest were normalized to β-Actin, which was used as the reference protein. Each sample was run in quintuplicate by a researcher blinded to the study group, with one PAE and one No PAE sample on each gel to minimize batch effects. This process was then repeated by a second study team member who was also blinded to group identity, yielding ten individual measures that were averaged to provide a single value for each protein of interest.

Meso Scale Discovery (MSD) multiplex determination of placental proteins.

Flash frozen human placental samples were homogenized using a Fisher Brand™ disposable pestle system (Fisher Scientific, Hampton, NH). Subsequently, samples processed for cytokine analysis were sonicated (Ultrasonic Processor, Model CV18) five times for 2 sec each in protein buffer (320 mM sucrose, 0.5 μM CaCl2, 1 μM MgCl2 and 0.5 μM NaHCO3) supplemented with protease and phosphatase inhibitors. For the angiogenesis assay, samples were lysed and sonicated in a commercially available Tris buffer (provided in the MSD kit) supplemented with protease and phosphatase inhibitors. The samples were then centrifuged at 4200 x g at 4°C for 10 min. The protein concentration in the supernatant was determined using the Bradford assay (BioRad, Hercules, CA).

Placental angiogenesis-related and cytokine proteins were analyzed with V-PLEX™ immunoassays (Meso Scale Discovery, Gaithersburg, MD) that measure protein concentrations of multiple targets simultaneously. For the angiogenesis proteins, 75 μg of placental lysate or calibrator 9 was loaded onto a Human Angiogenesis Panel 1 multi-spot plate (Catalog # K15190G) and the assay performed per the manufacturer’s protocol. The six angiogenesis-related proteins analyzed were VEGF-A, VEGF-C, VEGF-D, ANGR (Tie-2), VEGFR1 (Flt-1) and β-FGF. For the cytokine proteins, 100 μg of placental lysate or calibrator was loaded onto a Human Pro-inflammatory Panel 1 multi-spot plate (Catalog # K15049D) and the assay performed according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The pro-inflammatory cytokines analyzed were interferon gamma (IFN-γ), interleukin (IL)-1β, IL-2, IL-8, IL-12p70 and tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α). The anti-inflammatory cytokines analyzed were IL-4, IL-6, IL-10 and IL-13. The multiplex assays were read on a Quickplex SQ 120 (Meso Scale Discovery) consistent with our previous reports (Maxwell, Denson, Joste, Robinson, & Jantzie, 2015; Robinson et al., 2016; Yellowhair et al., 2018). Samples with concentrations below the limit of detection were removed from the study, as were those with a coefficient of variation greater than 25%.

Statistical Procedures.

Means and standard deviations were used to describe the continuous variables whereas frequency and percentages were used to describe discrete variables in the sample. T-tests and chi-square tests were used to assess differences for continuous and categorical variables, respectively, in the demographic, maternal-fetal, and substance use data whereas chi-square/fisher exact tests were used for categorical variables. A one-way repeated measures ANOVA was used to analyze the placental protein stability data. The difference in placental protein expression between the PAE and the No PAE groups was assessed using t-tests. Maternal age and gestational age at delivery were examined as potential covariates owing to their difference between study groups. No differences in other covariates between the groups were observed. An improvement in model fit (adjusted R2) was used as a criterion for inclusion of covariate in the model. As a result, maternal age (log transformed) was retained in the final multivariable analyses. Adjusted means and standard error of the placental protein expression between the study groups were calculated. No differences were observed in other covariates between groups. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analyses were conducted to further examine the ability of placental proteins to correctly classify PAE and No PAE subjects. Placental proteins were treated as a “test condition” and our grouping of subjects into PAE and No PAE, based on a combination of self-report and/or established ethanol biomarkers. The area under the curve (AUC) was calculated for individual proteins and for protein combinations, in an unadjusted analyses and then after adjusting for maternal age. All statistical analyses were performed using Stata© Version 14.2 and R version 3.4.

RESULTS

Demographic Characteristics.

The demographic and medical characteristics of the mothers and infants are presented according to the No PAE and PAE groups in Table 1. There were no significant differences between the groups with respect to gestational age at enrollment, race, ethnicity, maternal marital status, education, employment status, health insurance, gravidity, body mass index (BMI), presence of Hepatitis C, infant anthropometric measures, APGAR scores or neonatal complications. However, differences of borderline statistical significance were observed for maternal age (p = 0.056) and gestational age at delivery (p = 0.051).

TABLE 1.

Demographic and Medical Characteristics of the Mother-Infant Dyad by Study Group

| No PAE (n=13) | PAE(n=13) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD | ||

| Maternal age at enrollment (years) | 27.2 ± 3.8 | 30.9 ± 5.4 | 0.056 |

| Gestational age at enrollment (years) | 23.2 ± 8.1 | 23.6 ± 6.8 | 0.88 |

| Gestational age at delivery (weeks) | 38.6 ± 1.1 | 39.5 ± 1.1 | 0.051 |

| Body mass index | 24.5 ± 6.3 | 27.5 ± 6.6 | 0.25 |

| n (%) | n (%) | ||

| Ethnicity (Hispanic/Latina) | 6 (46.2) | 6 (46.2) | 1.00 |

| Race | |||

| White | 12 (92.3) | 13 (100.0) | 1.00 |

| American Indian or Alaskan Native | 1 (7.7) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Marital Status | |||

| Single/separated/divorced | 3 (23.1) | 5 (38.5) | 0.67 |

| Married/cohabitating | 10 (76.9) | 8 (61.5) | |

| Education level | |||

| Less than high-school | 0 (0.0) | 1 (7.7) | 0.64 |

| High-school to some college | 11 (84.6) | 9 (69.2) | |

| College or professional degree | 2 (15.4) | 3 (23.1) | |

| Currently employed | 7 (53.8) | 7 (53.8) | 1.00 |

| Health insurance (Medicaid) | 10 (76.9) | 10 (76.9) | 1.00 |

| Primigravida | 2 (15.4) | 0 (0.0) | 0.48 |

| Hepatitis C | 1 (7.7) | 3 (23.1) | 0.59 |

| Infant characteristics | Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD | |

| Birth weight (g) | 2959 ± 579 | 3034 ± 452 | 0.72 |

| Birth length (cm) | 48.6 ± 2.1 | 48.8 ± 2.5 | 0.81 |

| Occipital-frontal circumference (cm) | 33.8 ± 2.0 | 33.7 ± 1.1 | 0.79 |

| APGAR score 1 minutes | 8.0 ± 0.4 | 7.6 ± 1.3 | 0.31 |

| APGAR score 5 minutes | 9.0 ± 0.0 | 8.8 ± 0.4 | 0.15 |

| n (%) | n (%) | ||

| Respiratory distress | 1 (7.7) | 3 (23.1) | 0.59 |

| Neonatal opioid withdrawal syndrome | 3 (23.1) | 2 (15.4) | 1.00 |

| Neonatal infection requiring antibiotic treatment | 0 (0.0) | 4 (30.8) | 0.10 |

Substance Use.

In accordance with the eligibility criteria, the No PAE group reported minimal alcohol use during the periconceptional period and abstained from alcohol use during pregnancy as determined by both self-report and alcohol biomarkers (Table 2). The mean alcohol use in the PAE group during pregnancy was 0.7 ± 1.1 absolute ounces of alcohol per day (equivalent to ~10 standard drinks/week). The most prevalent ethanol biomarker in the PAE group was material uEtS (46.2%) at Visit 2 and PEth-DBS in the newborn (46.2%). There were no significant differences between groups relative to the use of other substances including MAT, other opioids, tobacco, marijuana or methamphetamines.

TABLE 2.

Alcohol and Substance Use Patterns by Study Group

| No PAE (n=13) | PAE (n=13) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alcohol Use | |||

| Alcohol use 12 months prior to enrollment | |||

| AUDIT: (mean ± SD) | 0.6 ± 0.8 | 13.4 ±13.0 | 0.002 |

| AUDIT ≥ 8: n (%) | 0 (0.0) | 8 (61.5) | 0.002 |

| Alcohol use around last menstrual period | |||

| AA/day (Mean ± SD) | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 2.1 ± 3.1 | 0.02 |

| AA/drinking day (Mean ± SD)a | 1.0 ± 0.7 | 3.7 ± 3.3 | 0.30 |

| Any binge drinking: n(%) | 0 (0.0) | 6 (46.2) | 0.01 |

| Alcohol use (periconceptional and during pregnancy) | |||

| AA/day (Mean ± SD) | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 0.7 ± 1.1 | 0.03 |

| AA/drinking day (Mean ± SD) a | 0.9 ± 0.5* | 4.6 ± 3.6 | 0.19 |

| ≥ 84 drinks per week during pregnancy based on 3 TLFB calendars: n(%) | 0 (0.0) | 6 (46.2) | 0.02 |

| n (%) | n (%) | ||

| Maternal ethanol biomarkers at V1 | |||

| GGT (> 40U/L) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| %dCDT (> 2) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| PEth (≥ 8 ng/ml) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (15.4) | 0.48 |

| Maternal ethanol biomarkers at V2 | |||

| GGT(> 40U/L) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| %dCDT (> 2) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (7.7) | 1.00 |

| PEth (≥ 8 ng/ml) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| uEtG (≥ 38 ng/ml) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | -- |

| uEtS (≥ 7.2 ng/ml) | 0 (0.0) | 6 (46.2)b | 0.005 |

| Newborn PEth-DBS (≥ 25 ng/ml) at birth | 0 (0.0) | 6 (46.2) | 0.01 |

| Maternal Substance Use | |||

| MAT (methadone, buprenorphine): | 7 (53.8) | 6 (46.2) | 1.00 |

| Tobacco | 7 (53.8) | 7 (53.8) | 1.00 |

| Other opioids (heroin/prescription opioids) | 4 (30.8) | 5 (38.5) | 1.00 |

| Marijuana | 3 (23.1) | 5 (38.5) | 0.67 |

| Methamphetamines | 0 (0.0) | 2 (15.4) | 0.48 |

AA/drinking day of subjects who had consumed alcohol during that period

uEtS was available in 12 PAE subjects

two subjects in the No PAE group reported minimal alcohol use in periconceptional period; abstained during pregnancy.

AA - Absolute alcohol; GGT, gamma-glutamyl transferase; CDT, carbohydrate deficient transferrin; PEth, phosphatidylethanol; uEtG, urine ethyl glucuronide, uEtS, urine ethyl sulfate; DBS, dry blood spot

Placental Protein Stability Study.

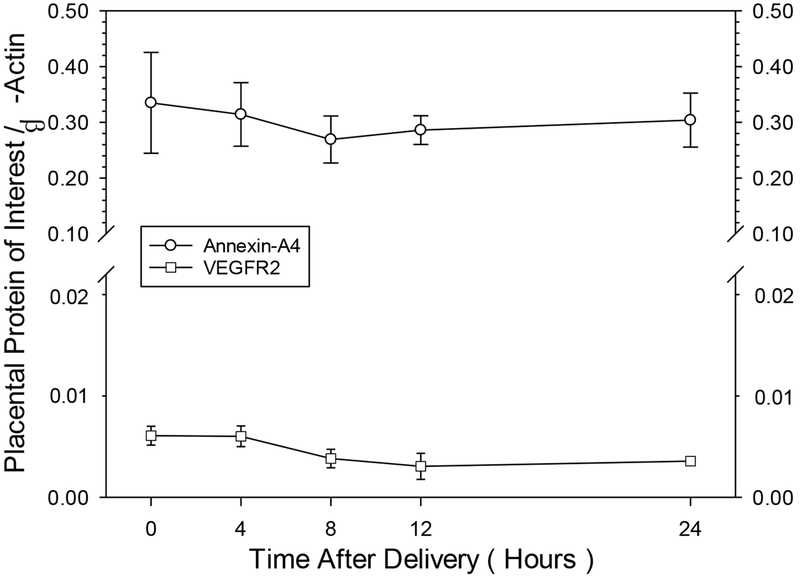

Tissue core samples were collected from four placental specimens at seven different time points after delivery (0, 1, 2, 4, 8, 12 and 24 hours). Results of the one-way repeated measures ANOVA for the two proteins analyzed showed that both VEGFR2, a relatively low abundance protein, and ANX-A4, a relatively high abundance protein, showed no statistically significant reductions in protein level as a function of time, suggesting that these two proteins are relatively stable in placenta for at least one day, if refrigerated after delivery (Figure 1). In the main study, the time of tissue harvest after delivery in the No PAE group (166 ± 61 minutes) was not significantly different from the PAE group (115 ± 39 minutes).

FIGURE 1.

Impact of time of tissue collection after delivery on the stability of two placental proteins. The relatively high abundance Annexin-A4 protein and the lower abundance VEGFR2 protein. Data points represent the mean ± SEM of four samples, from two vaginal and two cesarean deliveries, from non-PAE samples separate from the main study. A one-way repeated-measures ANOVA revealed no statistically significant differences across collection time points for either protein.

Impact of PAE on placental protein expression.

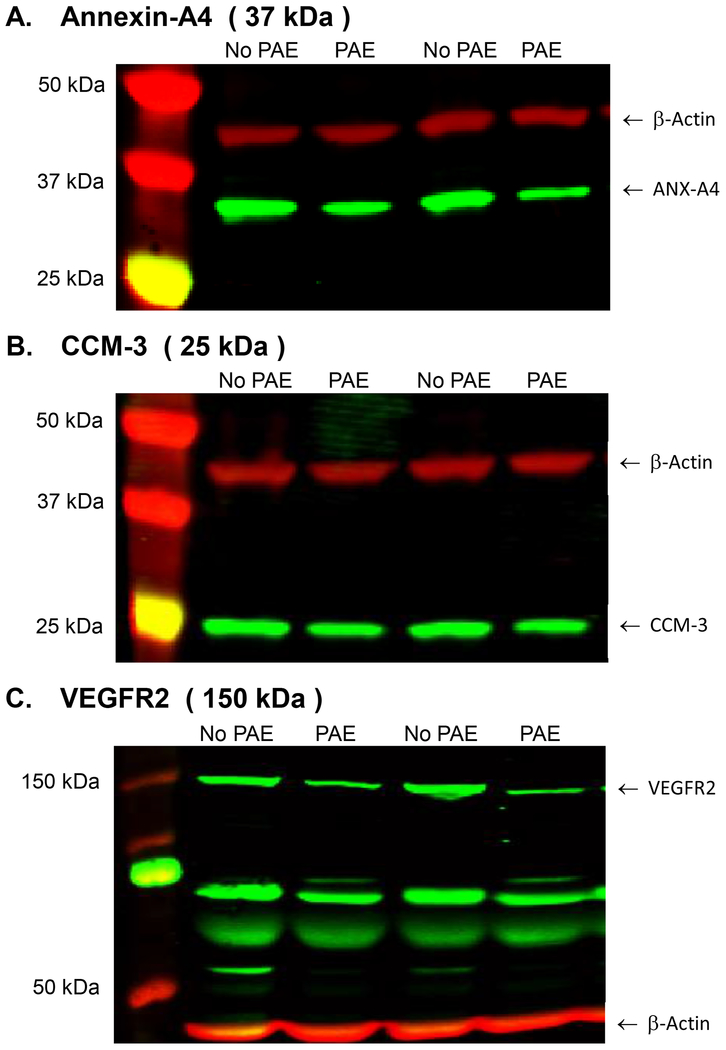

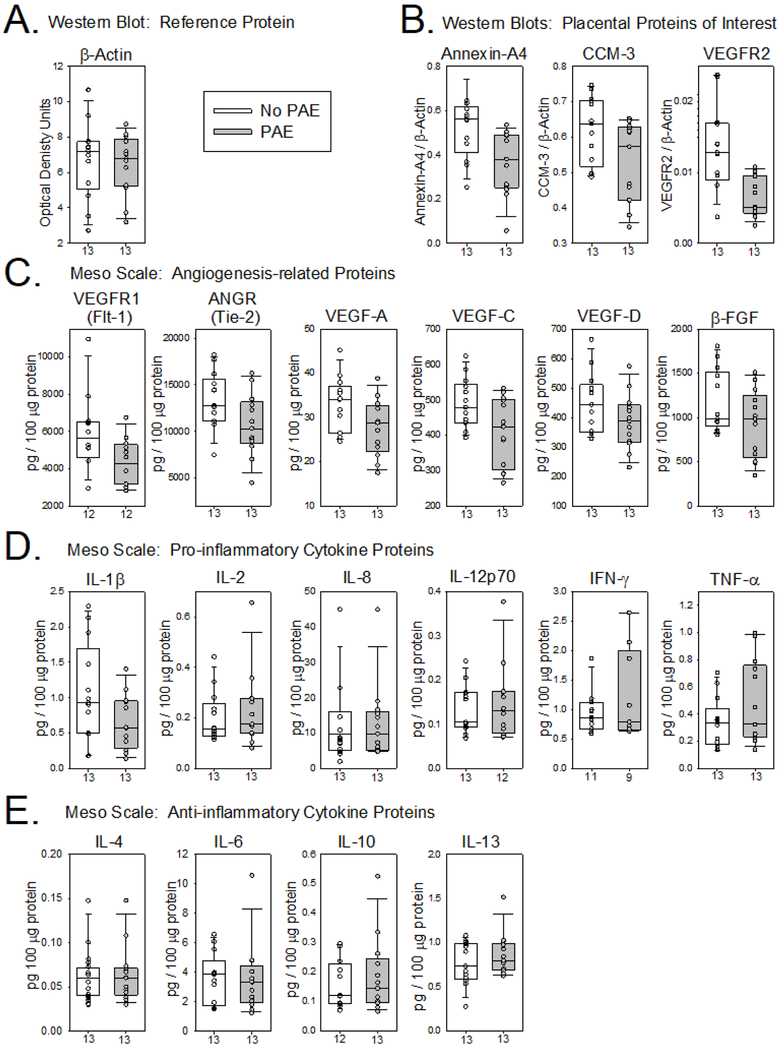

Figure 2 illustrates representative Western blots from placental tissue collected from a No PAE subject and a PAE subject. Reductions in protein were visible for all three proteins of interest measured. A summary of the raw data for all of the placental proteins is presented in Figure 3. The median level of the housekeeping protein β-actin was similar between groups (Figure 3A), suggesting no global alterations in placental protein expression due to PAE. In general, the median values of the three proteins of interest analyzed by Western blot (Figure 3B) and most of the other angiogenesis-related proteins (Figure 3C) trended downward in the PAE group. By contrast, with the exception of IL-1β, which also trended downward (Figure 3D), most of the median values for cytokines were similar between groups (Figure 3D & 3E).

FIGURE 2.

Representative Western blots for three human placental proteins. 2A: Annexin-A4. 2B: CCM-3 2C: VEGFR2. The three proteins of interest are the green bands and β-Actin (45 kDa), the reference protein, is the red band on each blot. The molecular weights for each of the three proteins of interest are indicated above each blot.

FIGURE 3.

Effect of prenatal alcohol exposure on human placental protein expression. The lower and upper boundary of each vertical box plot represent the 25th and 75th percentile, the horizontal bar indicates the median and the error bars represent the 10th and 90th percentile for the raw (unadjusted) placental protein data. Sample sizes are noted on the x-axis under each box plot.

Because maternal age trended higher in the PAE group, the raw placental protein data was adjusted for maternal age and the statistical analyses of the adjusted data is presented in Table 3. PAE was associated with a marked reduction in VEGFR2 protein levels compared to No PAE. A significant reduction in ANX-A4 was observed as well. CCM-3 levels were decreased in the PAE group, but this effect only trended towards significance. Among other angiogenesis-related proteins measured by MesoScale analysis, only VEGFR1 trended downward. The impact of PAE on pro-inflammatory cytokines was variable with TNF-α the only cytokine trending upward. Most of the anti-inflammatory cytokines were slightly increased in the PAE group, but only IL-13 trended higher (Table 3).

Table 3.

Expression of placental proteins by study groups adjusted by maternal age

| Placental | NO PAE (n=13) | PAE (n=13) | p-value* |

|---|---|---|---|

| Protein | Mean (SE) | Mean (SE) | |

| Reference Protein: Western Blot | |||

| β-ACTIN | 6.71 (0.58) | 6.46 (0.58) | 0.770 |

| Angiogenesis-related Proteins: Western Blot | |||

| ANX-A4 | 0.539 (0.042) | 0.354 (0.042) | 0.007 |

| CCM-3 | 0.615 (0.030) | 0.533 (0.030) | 0.077 |

| VEGFR2 | 0.013 (0.001) | 0.007 (0.001) | 0.007 |

| Angiogenesis-related Proteins: Meso Scale | |||

| VEGFR1** | 5846 (510) | 4406 (510) | 0.067 |

| ANGR | 13035(904) | 11026 (904) | 0.143 |

| VEGF-A | 32.1 (1.7) | 28.4 (1.7) | 0.161 |

| VEGF-C | 477 (23) | 423 (23) | 0.119 |

| VEGF-D | 436 (27) | 400 (27) | 0.374 |

| β-FGF | 1116 (98) | 982 (98) | 0.361 |

| Pro-inflammatory Cytokines: Meso Scale | |||

| IL-1β | 0.976 (0.156) | 0.753 (0.163) | 0.354 |

| IL-2 | 0.183 (0.035) | 0.251 (0.035) | 0.193 |

| IL-8 | 8.34 (2.45) | 14.05 (2.45) | 0.125 |

| IL-12p70** | 0.127 (0.020) | 0.157 (0.021) | 0.310 |

| IFN-γ** | 0.916 (0.183) | 1.285 (0.203) | 0.209 |

| TNF-α | 0.306 (0.070) | 0.514 (0.070) | 0.055 |

| Anti-inflammatory Cytokines: Meso Scale | |||

| IL-4 | 0.053 (0.007) | 0.068 (0.007) | 0.185 |

| IL-6 | 3.25 (0.56) | 3.88 (0.56) | 0.450 |

| IL-10** | 0.141 (0.030) | 0.204 (0.029) | 0.161 |

| IL-13 | 0.733 (0.065) | 0.904 (0.065) | 0.088 |

Adjusted for maternal age (log transformed) at delivery

Sample size can vary due to pairwise deletion of the missing data

The results of the ROC analyses demonstrated moderate-to-high ‘diagnostic accuracy’ for individual angiogenesis proteins and cytokines, which further improved upon addition of maternal age in the model (Table 4). Combinations of three or more proteins, organized by function or methodological approach, substantially increased their ability to differentiate between PAE and No PAE subjects (Table 5). Specifically, the combination of anti-inflammatory cytokines yielded an adjusted AUC of 83.3%, whereas the combination of pro-inflammatory cytokines resulted in AUC of 91.9%. The combination of all angiogenesis proteins analyzed by Meso Scale reached an adjusted AUC of 93.5%, whereas the three proteins analyzed by Western Blot had an adjusted AUC of 100%.

Table 4.

Receiver operating curve analysis of individual placental proteins for differentiating PAE and No PAE subjects.

| Protein | AUC (95% CI) Unadjusted | p-value | AUC (95% CI) Adjusted* | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reference Protein: Western Blot | ||||

| β-ACTIN | 53.8 (30.4-77.3) | 0.723 | 71.0 (50.4-91.7) | 0.740 |

| Angiogenesis-related proteins: Western Blot | ||||

| ANX-A4 | 79.3 (61.2-97.3) | 0.024 | 88.8 (75.1-100) | 0.017 |

| CCM-3 | 74.3 (54.7-93.9) | 0.044 | 78.1 (60.2-96) | 0.077 |

| VEGFR2 | 85.5 (69.9-100) | 0.013 | 87.6 (73.6-100) | 0.019 |

| Angiogenesis-related proteins: Meso Scale | ||||

| VEGFR1 | 73.6 (52.7-94.6) | 0.045 | 80.6 (62.6-98.5) | 0.063 |

| ANGR | 72.2 (51.6-92.8) | 0.058 | 78.1 (60.2-96) | 0.140 |

| VEGF-A | 72.2 (52-92.4) | 0.054 | 78.7 (60.4-97) | 0.157 |

| VEGF-C | 72.8 (52.6-92.9) | 0.042 | 78.1 (58.9-97.3) | 0.124 |

| VEGF-D | 67.5 (46.1-88.8) | 0.118 | 75.7 (56.4-95) | 0.357 |

| β-FGF | 66.9 (45.2-88.6) | 0.101 | 77.5 (58.4-96.6) | 0.345 |

| Pro-inflammatory Cytokines: Meso Scale | ||||

| IL-1β | 66.0 (43.8-88.2) | 0.104 | 73.7 (53.0.5-94) | 0.346 |

| IL-2 | 56.2 (32.7-79.7) | 0.531 | 72.2 (52.2-92.2) | 0.186 |

| IL-8 | 57.4 (34.2-80.6) | 0.402 | 76.9 (58.5-95.3) | 0.141 |

| IL-12p70 | 50.0 (25.8-74.2) | 0.601 | 69.9 (48.7-91.1) | 0.291 |

| IFN-γ | 54.0 (25.8-82.3) | 0.280 | 75.8 (53.7-97.9) | 0.216 |

| TNF-α | 62.7 (40.0-85.4) | 0.176 | 77.5 (59.3-95.7) | 0.074 |

| Anti-inflammatory Cytokines: Meso Scale | ||||

| IL-4 | 52.4 (29.1-75.6) | 0.558 | 73.4 (53.6-93.2) | 0.174 |

| IL-6 | 56.2 (32.9-79.5) | 0.924 | 70.4 (49.2-91.6) | 0.428 |

| IL-10 | 52.2 (28.5-76.0) | 0.530 | 75.6 (56.3-95.0) | 0.166 |

| IL-13 | 60.4 (37.0-83.7) | 0.284 | 76.3 (56.9-95.8) | 0.101 |

Adjusted for maternal age (log transformed)

Table 5.

Receiver operating curve analysis of selected placental protein combinations for differentiating PAE and No PAE subjects.

| Placental Protein Group | AUC (95% CI) Unadjusted | AUC (95% CI) Adjusted* |

|---|---|---|

| Angiogenesis-related proteins: Western Blots | ||

| ANX-A4, CCM-3, VEGFR2 | 97.6 (93.1-100.0) | 100 (100-100) |

| Angiogenesis-related proteins: Meso Scale | ||

| VEGFR1, ANGR, VEGF-A, VEGF-C, VEGF-D, β-FGF | 84.0 (68.4-99.7) | 93.5 (83.3-100) |

| Pro-inflammatory Cytokines: Meso Scale | ||

| IL-1β, IL-2, IL-8, IL-12p70, IFN-γ, TNF-α | 85.9 (69.4-100) | 91.9 (79.5-100) |

| Anti-inflammatory Cytokines: Meso Scale | ||

| IL-4, IL-6, IL-10, IL-13 | 75.6 (54.1-97.2) | 83.3 (66.7-100) |

Adjusted for maternal age (log transformed)

DISCUSSION

As summarized in Table 3, the salient observation from this pilot study is that PAE was associated with a significant reduction in the expression of two placental proteins, VEGFR2 and ANX-A4. The levels of the reference protein β-actin were not different between groups, suggesting that PAE did not globally affect protein expression. The expression of two other angiogenesis-related proteins, CCM-3 and VEGFR1, trended downward in placentae from the PAE group. Significant reductions in placental CCM-3 and VEGFR1 have also been observed in rodent models of PAE (Lecuyer et al., 2017). These effects were associated with reduced placental vascular development (Lecuyer et al., 2017). Of particular note, CCM-3, also known as PDCD10, stabilizes and activates VEGFR2 receptors on endothelial cells (He et al., 2010), a critical process in angiogenesis. The reduction in VEGFR2 along with trending reductions in VEGFR1 and CCM-3 observed in the present study suggests that PAE may impair processes involved in vascular remodelling in human placental tissue as well, particularly with increasing maternal age.

In contrast to qualitatively similar patterns of PAE-related alterations in angiogenesis-related proteins in placenta of rodents and humans, opposite effects were observed for placental ANX-A4 expression. ANX-A4 was significantly elevated in rat placenta and fetal cerebral cortex after PAE (Gonzalez et al., in revision). Elevated ANX-A4 appears to be involved in mediating calcium-induced toxicity in a variety of cell types including vascular endothelium, reactive astrocytes, oligodendrocytes, ependymocytes, choroid plexus, and meningothelium (Eberhard, Brown, & VandenBerg, 1994). ANX-A4 expression was also elevated in postmortem brain samples of patients with alcoholism compared with controls (Sohma et al., 2001). Ethanol exposure dose-dependently elevates ANX-A4 expression in rat C6 glioma and human adenocarcinoma A549 cell lines and overexpression of ANX-A4 increased ethanol-induced cytotoxic damage (Ohkawa et al., 2002; Sohma et al., 2002). However, in contrast to the effects of PAE in rat placenta, human placental ANX-A4 levels were significantly reduced in the PAE group compared to the No PAE group (Table 3). The basis for this apparent differential effect may be related to a variety of factors including: 1) variable amounts and/or patterns of alcohol exposure in the preclinical versus clinical studies, 2) the presence of other potentially confounding factors including medical co-morbidities or co-exposure to a variety of other substances that can occur in human studies or, 3) ANX-A4 having different roles in different species. ANX-A4 has been shown to increase in human placenta at term where it has been suggested to have anticoagulant properties (Masuda et al., 2004).

Whereas PAE generally lowered the expression of angiogenesis-related proteins, overall, a pattern of higher levels of both pro-and anti-inflammatory cytokines was observed in placentae from the PAE group with two, TNF-α and IL-13 (Table 3), trending towards significant elevations. Overall, the impact of PAE on cytokine levels in human placenta reported here (Table 3) are consistent with prior preclinical and clinical studies investigating the effects of alcohol on cytokine expression in placenta and in other tissues. Terasaki et al. (2016) observed that one week of moderate PAE increased the expression in mRNA for IL-6 in placenta and increased IL-10, IL-5 and TNF-α mRNA expression in brain collected from mouse fetuses at Gestational Day (GD) 17. Roberson et al. (2012) reported that acute alcohol treatment on GD 8 elevated IL-6, but reduced the levels of IL-13 protein in whole mouse embryos six hours after exposure. Svinarich et al., (1998) reported elevations in IL-6 mRNA in HTR-8/SVneo trophoblast cultures after twenty-four hours exposure to ethanol.

Clinical studies in this area have focused primarily on the effects of PAE on cytokine expression in blood. For example, Ahluwalia et al. (2000) reported significant elevations of IL-6, IL-1β and TNF-α in lymphocytes isolated from cord blood from women who consumed moderate amounts of ethanol during pregnancy. A more recent report by Bodnar et al (2018) reported increased IL-15 and IL-10 protein in plasma collected from alcohol-consuming women during the second trimester. These effects did not persist into the third trimester, whereas elevations in plasma VEGF-D were noted instead. Other plasma cytokines and angiogenesis-related proteins, similar to the proteins assayed in the present placental study, were not different in plasma during either the second or third trimester. Of note, Bodnar and colleagues were unable to detect IL-1β, IL-2, IL-12p70 or IL-13 in their plasma samples, whereas these four cytokines were readily detected in our placental samples (Figure 3D and 3E). Using a constrained principal component analysis procedure, these authors identified an “alcohol exposure network” of enriched cytokines and angiogenesis factors that included IL-15, IL-10, VEGF-D, Flt-1 (VEGFR1) and TNF-α, during the second trimester of pregnancy. This network did not persist into the third trimester (Bodnar et al., 2018). This pattern of activated cytokines and angiogenesis-related proteins in plasma during the second trimester contrasts with the general pattern of elevated cytokines but reduced angiogenesis-related proteins in human placenta in the present placental study (Figure 3 and Table 3). The basis for different patterns of responses is likely attributable to multiple factors including different tissue types and possibly the stage of gestation when samples were collected. In placenta, an elevated cytokine profile accompanied by a profile of repressed angiogenesis proteins (Figure 3) is consistent with observations that elevations in cytokines, such as IFN-γ, IL-10 and TNF-α diminish angiogenesis in co-cultures of human endothelial and trophoblast cells (Sokolov et al., 2017). Taken together, these observations suggest that ethanol may have multiple direct and indirect effects on placental angiogenesis that can lead to diminished placental function.

This pilot project had the dual objectives of establishing the feasibility of this experimental approach and to initiate a translational comparison of PAE-induced alterations in placental protein expression from rodent models of PAE to humans. One methodological factor that could have limited feasibility was the question of placental protein stability after delivery. During the planning stages, there was concern that placental proteins would undergo significant degradation after delivery, thus limiting the ability to interpret the results. This issue was addressed by examining the stability of ANX-A4, a relatively high abundance protein, and VEGFR2, a lower abundance protein, for up to twenty-four hours after delivery. If rinsed in ice-cold saline and refrigerated shortly after delivery, we observed that these two proteins were relatively stable over twenty-four hours (Figure 1), providing evidence that protein degradation does not appear to be a major factor limiting the feasibility of this approach. Nevertheless, in future studies, we anticipate limiting placental tissue harvesting to no more than four hours after delivery.

While we also demonstrated the feasibility of rapidly collecting placental core tissue samples in a prospective manner, one limitation of the core sample technique used is that the sample contained different cell types from across the entire maternal-fetal extent. A more careful dissection of placenta into discrete regions may have resulted in greater group differences and perhaps less variable measures of certain proteins. However, at the onset of planning for these studies, it was reasoned that if placental proteomics were to eventually demonstrate diagnostic utility and become more widely employed, the collection procedure would need to be relatively simple and streamlined for ease of use in clinical settings.

Another limitation in this study was sample size, which affected the statistical analysis of some of the proteins lacking sufficient power to make adequate individual comparisons between the experimental groups. Limited sample size also precluded the prospect of examining whether specific alcohol questionnaires or individual alcohol biomarkers were more sensitive for identifying the PAE group or whether different cut-offs for these measures might increase the utility of these measures. The small sample size also limited the ability to relate dose-response patterns with placental protein expression.

In spite of these limitations, we were encouraged by these results. In particular,the ROC analyses of combinations of proteins (Table 5) suggests the potential utility of examining combinations of placental proteins as biomarkers for the identification of infants with PAE. It is possible that future investigations with larger sample sizes may yield a greater number of placental angiogenesis-related and cytokine proteins altered by PAE. In addition, it will be important to consider other placental proteins affected by alcohol exposure. For example, placental growth factor (PLGF) has been shown to be reduced in both rodent and human placenta and these reductions have been associated with microvascular alterations in both placenta and fetal cerebral cortex (Lecuyer et al. (2017). Such results would facilitate more complex analyses of networks of altered placental proteins, as in Bodnar et al. (2018). Protein network analyses could be more informative than the analysis of individual or small combinations of selected proteins for determining whether patterns of placental proteins altered by PAE are prognostic for adverse developmental outcomes. Further, in addition to expanded studies in placenta, it is possible that combinations of these proteins could be examined in maternal serum where angiogenesis-related proteins were shown to have utility for early detection of patients at risk of preeclampsia (Myatt et al. (2013); Polliotti et al. (2003).

Such data might also provide novel insights about alcohol-related mechanisms of teratology. For example, other studies could also focus on examining the effects of PAE on placental microvasculature and whether the protein alterations observed in the present study correlate with pathological alterations in placental structure or function. Follow-up neurobehavioral studies of the offspring whose mothers were enrolled into this prospective study may shed insights on whether alterations in placental protein expression correlated with adverse neurodevelopmental outcomes. Given that the placenta and brain share many developmental pathways, such studies could provide a more definitive assessment of the utility of biomarker processes in placenta as prognostic indictors of functional brain damage associated with PAE.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors wish to thank Laura Garrison, Alyssa Ortega, Stephen Bishop, and Sonnie Williams for their assistance in the recruiting of patients and collection of placenta samples, data management, IRB approvals, conducting interviews and follow-up with subjects. Additionally, we thank Dr. Jessie Maxwell and Tracylyn Yellowhair for technical assistance in the operation of the MesoScale system, and Dr. Andrea Allan and Dr. Ronald Schrader for assistance with statistical analyses. This work was supported by UL1 TR001449, R01 AA021771, and P50 AA022534.

Grant Support: UL1 TR001449, R01 AA021771, P50 AA022534

REFERENCES

- Abel EL (1984). Prenatal effects of alcohol. Drug Alcohol Depend, 14(1), 1–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahluwalia B, Wesley B, Adeyiga O, Smith DM, Da-Silva A, & Rajguru S (2000). Alcohol modulates cytokine secretion and synthesis in human fetus: an in vivo and in vitro study. Alcohol, 21(3), 207–213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bakhireva LN, Lowe JR, Gutierrez HL, & Stephen JM (2015). Ethanol, Neurodevelopment, Infant and Child Health (ENRICH) prospective cohort: Study design considerations. Adv Pediatr Res, 2(2015). doi: 10.12715/apr.2015.2.10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balaraman S, Lunde ER, Sawant O, Cudd TA, Washburn SE, & Miranda RC (2014). Maternal and neonatal plasma microRNA biomarkers for fetal alcohol exposure in an ovine model. Alcohol Clin Exp Res, 38(5), 1390–1400. doi: 10.1111/acer.12378 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balaraman S, Schafer JJ, Tseng AM, Wertelecki W, Yevtushok L, Zymak-Zakutnya N, … Miranda RC (2016). Plasma miRNA Profiles in Pregnant Women Predict Infant Outcomes following Prenatal Alcohol Exposure. PLoS One, 11(11), e0165081. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0165081 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bodnar TS, Raineki C, Wertelecki W, Yevtushok L, Plotka L, Zymak-Zakutnya N, … Collaborative Initiative on Fetal Alcohol Spectrum, D. (2018). Altered maternal immune networks are associated with adverse child neurodevelopment: Impact of alcohol consumption during pregnancy. Brain Behav Immun. 73(10):205–215. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2018.05.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter RC, Chen J, Li Q, Deyssenroth M, Dodge NC, Wainwright HC, … Jacobson SW (2018). Alcohol-Related Alterations in Placental Imprinted Gene Expression in Humans Mediate Effects of Prenatal Alcohol Exposure on Postnatal Growth. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. doi: 10.1111/acer.13808 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conry J (1990). Neuropsychological deficits in fetal alcohol syndrome and fetal alcohol effects. Alcohol Clin Exp Res, 14(5), 650–655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Datta S, Turner D, Singh R, Ruest LB, Pierce WM Jr., & Knudsen TB (2008). Fetal alcohol syndrome (FAS) in C57BL/6 mice detected through proteomics screening of the amniotic fluid. Birth Defects Res A Clin Mol Teratol, 82(4), 177–186. doi: 10.1002/bdra.20440 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis-Anderson KL, Berger S, Lunde-Young ER, Naik VD, Seo H, Johnson GA, … Ramadoss J (2017). Placental Proteomics Reveal Insights into Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorders. Alcohol Clin Exp Res, 41(9), 1551–1558. doi: 10.1111/acer.13448 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Downing C, Flink S, Florez-McClure ML, Johnson TE, Tabakoff B, & Kechris KJ (2012). Gene expression changes in C57BL/6J and DBA/2J mice following prenatal alcohol exposure. Alcohol Clin Exp Res, 36(9), 1519–1529. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2012.01757.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eberhard DA, Brown MD, & VandenBerg SR (1994). Alterations of annexin expression in pathological neuronal and glial reactions. Immunohistochemical localization of annexins I, II (p36 and p11 subunits), IV, and VI in the human hippocampus. Am J Pathol, 145(3), 640–649. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardiner AS, Gutierrez HL, Luo L, Davies S, Savage DD, Bakhireva LN, & Perrone-Bizzozero NI (2016). Alcohol Use During Pregnancy is Associated with Specific Alterations in MicroRNA Levels in Maternal Serum. Alcohol Clin Exp Res, 40(4), 826–837. doi: 10.1111/acer.13026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanson JW, Streissguth AP, & Smith DW (1978). The effects of moderate alcohol consumption during pregnancy on fetal growth and morphogenesis. J Pediatr, 92(3), 457–460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He Y, Zhang H, Yu L, Gunel M, Boggon TJ, Chen H, & Min W (2010). Stabilization of VEGFR2 signaling by cerebral cavernous malformation 3 is critical for vascular development. Sci Signal, 3(116), ra26. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2000722 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lecuyer M, Laquerriere A, Bekri S, Lesueur C, Ramdani Y, Jegou S, … Gonzalez BJ (2017). PLGF, a placental marker of fetal brain defects after in utero alcohol exposure. Acta Neuropathol Commun, 5(1), 44. doi: 10.1186/s40478-017-0444-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Louvi A, Nishimura S, & Gunel M (2014). Ccm3, a gene associated with cerebral cavernous malformations, is required for neuronal migration. Development, 141(6), 1404–1415. doi: 10.1242/dev.093526 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lussier AA, Morin AM, MacIsaac JL, Salmon J, Weinberg J, Reynolds JN, … Kobor MS (2018). DNA methylation as a predictor of fetal alcohol spectrum disorder. Clin Epigenetics, 10, 5. doi: 10.1186/s13148-018-0439-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masuda J, Takayama E, Satoh A, Ida M, Shinohara T, Kojima-Aikawa K, … Matsumoto I (2004). Levels of annexin IV and V in the plasma of pregnant and postpartum women. Thromb Haemost, 91(6), 1129–1136. doi: 10.1160/TH03-12-0778 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maxwell JR, Denson JL, Joste NE, Robinson S, & Jantzie LL (2015). Combined in utero hypoxia-ischemia and lipopolysaccharide administration in rats induces chorioamnionitis and a fetal inflammatory response syndrome. Placenta, 36(12), 1378–1384. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2015.10.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meng H, Song Y, Zhu J, Liu Q, Lu P, Ye N, … Wu H (2016). LRG1 promotes angiogenesis through upregulating the TGFbeta1 pathway in ischemic rat brain. Mol Med Rep, 14(6), 5535–5543. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2016.5925 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myatt L, Clifton RG, Roberts JM, Spong CY, Wapner RJ, Thorp JM Jr., … Human Development Maternal-Fetal Medicine Units, N. (2013). Can changes in angiogenic biomarkers between the first and second trimesters of pregnancy predict development of pre-eclampsia in a low-risk nulliparous patient population? BJOG, 120(10), 1183–1191. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.12128 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohkawa H, Sohma H, Sakai R, Kuroki Y, Hashimoto E, Murakami S, & Saito T (2002). Ethanol-induced augmentation of annexin IV in cultured cells and the enhancement of cytotoxicity by overexpression of annexin IV by ethanol. Biochim Biophys Acta, 1588(3), 217–225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polliotti BM, Fry AG, Saller DN, Mooney RA, Cox C, & Miller RK (2003). Second-trimester maternal serum placental growth factor and vascular endothelial growth factor for predicting severe, early-onset preeclampsia. Obstet Gynecol, 101(6), 1266–1274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramadoss J, & Magness RR (2012). Alcohol-induced alterations in maternal uterine endothelial proteome: a quantitative iTRAQ mass spectrometric approach. Reprod Toxicol, 34(4), 538–544. doi: 10.1016/j.reprotox.2012.08.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberson R, Kuddo T, Benassou I, Abebe D, & Spong CY (2012). Neuroprotective peptides influence cytokine and chemokine alterations in a model of fetal alcohol syndrome. Am J Obstet Gynecol, 207(6), 499 e491–495. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2012.10.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson S, Winer JL, Berkner J, Chan LA, Denson JL, Maxwell JR, … Jantzie LL (2016). Imaging and serum biomarkers reflecting the functional efficacy of extended erythropoietin treatment in rats following infantile traumatic brain injury. J Neurosurg Pediatr, 17(6), 739–755. doi: 10.3171/2015.10.PEDS15554 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg MJ, Wolff CR, El-Emawy A, Staples MC, Perrone-Bizzozero NI, & Savage DD (2010). Effects of moderate drinking during pregnancy on placental gene expression. Alcohol, 44(7–8), 673–690. doi: 10.1016/j.alcohol.2009.10.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaywitz SE, Cohen DJ, & Shaywitz BA (1980). Behavior and learning difficulties in children of normal intelligence born to alcoholic mothers. J Pediatr, 96(6), 978–982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sohma H, Ohkawa H, Hashimoto E, Sakai R, & Saito T (2002). Ethanol-induced augmentation of annexin IV expression in rat C6 glioma and human A549 adenocarcinoma cells. Alcohol Clin Exp Res, 26(8 Suppl), 44S–48S. doi: 10.1097/01.ALC.0000026975.39372.A5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sohma H, Ohkawa H, Hashimoto E, Toki S, Ozawa H, Kuroki Y, & Saito T (2001). Alteration of annexin IV expression in alcoholics. Alcohol Clin Exp Res, 25(6 Suppl), 55S–58S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sokolov DI, Lvova TY, Okorokova LS, Belyakova KL, Sheveleva AR, Stepanova OI, … Sel’kov SA (2017). Effect of Cytokines on the Formation Tube-Like Structures by Endothelial Cells in the Presence of Trophoblast Cells. Bull Exp Biol Med, 163(1), 148–158. doi: 10.1007/s10517-017-3756-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Streissguth AP, Barr HM, & Sampson PD (1990). Moderate prenatal alcohol exposure: effects on child IQ and learning problems at age 7 1/2 years. Alcohol Clin Exp Res, 14(5), 662–669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Svinarich DM, DiCerbo JA, Zaher FM, Yelian FD, & Gonik B (1998). Ethanol-induced expression of cytokines in a first-trimester trophoblast cell line. Am J Obstet Gynecol, 179(2), 470–475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terasaki LS, & Schwarz JM (2016). Effects of Moderate Prenatal Alcohol Exposure during Early Gestation in Rats on Inflammation across the Maternal-Fetal-Immune Interface and Later-Life Immune Function in the Offspring. J Neuroimmune Pharmacol, 11(4), 680–692. doi: 10.1007/s11481-016-9691-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yellowhair TR, Noor S, Maxwell JR, Anstine CV, Oppong AY, Robinson S, … Jantzie LL (2018). Preclinical chorioamnionitis dysregulates CXCL1/CXCR2 signaling throughout the placental-fetal-brain axis. Exp eurol, 301(Pt B), 110–119. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2017.11.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao H, Kalish FS, Wong RJ, & Stevenson DK (2018). Hypoxia regulates placental angiogenesis via alternatively activated macrophages. Am J Reprod Immunol, e12989. doi: 10.1111/aji.12989 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]