Abstract

To avoid discomfort, health care professionals may hesitate to pursue conversations about end of life with patients. Certain tools have the potential to facilitate smoother conversations in this matter. The objective was to explore the experiences of patients in palliative care in using statement cards to talk about their wishes and priorities. Forty-six cards with statements of wishes and priorities were developed and tested for feasibility with 40 participants, who chose the 10 most important cards and shared their thoughts about the statements and conversation. Data from individual interviews and field notes were analyzed using content analysis. One category describes practical aspects of using the cards including the relevance of the content and the process of sorting the cards. The second category describes the significance of using the cards including becoming aware of what is important, sharing wishes and priorities, and reflecting on whether wishes and priorities change closer to death. The cards helped raise awareness and verbalize wishes and priorities. All statements were considered relevant. The conversations focused not only on death and dying, but also on challenges in the participants' current life situation. For the most ill and frail participants, the number of cards needs to be reduced.

KEY WORDS: cards, communication, palliative care, qualitative research, wishes and priorities

Palliative care aims to attend to the dying person's unique wishes and priorities. If these are known, care planning can be carried through with the patient and family in a flexible way and be used as a benchmark when evaluating care.1-3 Initiating a conversation about wishes and priorities gives patients a voice to define their preferences for dying and death.4 In the absence of these conversations, the possibility of person-centered care may be reduced as the preferences and ideas of patients, their families, and health care personnel (HCP) may vary.5,6

End-of-life care conversations and participating in advance care planning (ACP) have been shown to improve end-of-life care.1,6 Patients and their families often want HCP to initiate such conversations.7 However, HCP sometimes hesitates with concerns such as not knowing how to initiate the conversation and that incorrect timing may cause discomfort to the patients and families, or fear that the conversations may harm the relationships built between the patient/family and the HCP.8 Pollock and Wilson8 argue that this may cause vagueness in the language used in these conversations that can allow both parties to choose either to avoid or to continue the discussion, which may increase the risk of misunderstandings and assumptions.

Tools in the form of cards featuring pictures or statements have been shown to facilitate putting thoughts and feelings into words when tested in various contexts such as in conversations with adults with obesity9 and in healthy people discussing end-of-life issues.10 According to Lankarani-Fard et al,11 cards with relevant statements can help patients in palliative care to verbalize important aspects at end of life that may otherwise be difficult to formulate. However, to increase understanding of the practical use and value of conversations with statement cards, studies are needed to investigate patients' experiences of these conversations.

Therefore, the aim of the study was to explore how patients in specialist palliative care (SPC) experience using cards to talk about their wishes and priorities.

METHODS

Setting and Sampling

Patients were recruited from five SPC units supporting patients at home or in inpatient units in the south of Sweden. A contact nurse from each unit identified potential participants and provided them with verbal and written information about the study. If they expressed interest in participating, the research team provided them with further information by phone within a week, emphasizing the voluntariness to participate. If still interested, an interview was arranged at a time and place of the participants' choosing (at home = 36, research center = 2, inpatient unit = 1, nursing home = 1). Information about the study along with the cards (in a Word-document) was sent by mail or email to each participant a few days before the interview.

Purposive sampling of adults with cognitive and verbal capabilities to participate in a 1-hour conversation was applied. Fifty-nine persons were asked to participate, and 41 agreed. The reasons for nonparticipation were lack of time or energy or “not interested.” One participant agreed to participate but the participant's health deteriorated quickly and was unable to take part in the interview. The 40 participants included 15 women (median age, 71 years; range, 38–85 years) and 25 men (median age, 72; range, 47–87 years). Thirty-nine were born in Sweden, 37 had a cancer diagnosis (other diagnoses were heart failure and kidney failure), and 29 were cohabitants. In the total sample, the average time of death was 3 months (range, 6 days to 15 months) after participating in the study.

Data Collection

Initially, a deck of cards featuring 62 statements was developed. The statements were based on international research,6 the European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer 15 PAL questionnaire,12 the revised Edmonton Symptom Assessment System,13 and the Liverpool Care Pathway.14 They were also based on the Integrated Palliative Care Outcome Scale,15 the Swedish Register of Palliative Care (www.palliativ.se), and Swedish policy documents on palliative care. The statements were also inspired by an ongoing project in Sweden titled the DoBra program,16 in which the “Go Wish” cards11,17 have been translated into Swedish. The statements were worded from the participants' perspective. For example, the survey question, “Have you had as much information as you wanted?” was reworded to “To have as much information as I want.” The deck of cards aimed to cover the essential aspects of palliative care, while including as few cards as possible. To assess the feasibility and content validity of the cards, 2 focus group sessions and 1 patient interview (led by authors U.O.M. and B.H.R.) were performed. Those included 4 patient representatives from the Regional Cancer Centre South (https://www.cancercentrum.se/syd/ [in Swedish]), 8 pensioners from the Swedish National Pensioners Organization (https://www.pro.se/Om-pro/Sprak/Engelska/), and 1 individual interview at an inpatient unit. In response to their comments on the content and suitability of the cards and the time and emotional cost of ranking the cards, 46 cards and 3 blank cards for personal important wishes and priorities were finally included in the set (Appendix).

The Q-sort method18 was chosen for this study, as it is well suited for exploring participant's various opinions on a given subject, such as wishes and priorities. To get a thorough understanding of the feasibility of using the cards in conversations with patients in SPC, the first 10 interviews were tape-recorded and analyzed. The participants were asked to “think aloud”19 their thoughts and feelings on the content and suitability of the cards and the conversation. As the conversations were judged feasible, data collection continued through face-to-face interviews using field notes with the other 30 participants.

Data collection was performed from February 2016 to March 2017. One junior and 1 senior researcher performed the tape-recorded interviews in pairs. In the second phase, U.O.M. and B.H.R. educated 6 nurses and 1 psychologist in palliative care who then performed the interview. Before the interview, informed consent was obtained, and the participants were asked to select the 10 cards most important to them. To facilitate the card sorting process, the interviewer suggested putting the cards in 3 piles: very important, somewhat important, and not important. As vulnerable patients were included and they were asked to talk about a sensitive topic, the first 10 interviews of the card sorting process were tape-recorded to make it possible for the larger research group to gain insights into the ethical and feasible aspects. The analysis of the first 10 interviews showed it both ethical and feasible, but also that, pragmatically, use of detailed field notes was as informative as the tape recordings, and it was decided to use only field notes in the remaining interviews. During the card sorting process, the participants were asked to express their thoughts, feelings, and concerns about (1) the statements, (2) discussing wishes and priorities, and (3) the card sorting process. A family member took part in 7 interviews, mainly as a listening bystander.

Field notes were written immediately after each interview and documented demographic and contextual information, as well as researchers' reflections on participants' emotional and physical manifestations such as tiredness, crying, and laughter, including the ambiance during the interview situation.

Data Analyses

The interviews lasted between 14 and 64 minutes (mean, 42 minutes). The recorded interviews (n = 10) were transcribed verbatim and were, together with the field notes (n = 10 + 30), analyzed using inductive stepwise conventional qualitative content analysis, as previous research on the specific phenomenon was limited.20 The analysis started with 3 authors (U.O.M., C.P., B.H.R.) independently reading all the texts to get an overall understanding of the phenomenon. After comparing their first understanding of the texts as a whole, meaning units related to the aim of the study were identified in the text, coded for content, and grouped into meaningful clusters. All authors thereafter read the meaning units, codes, and clusters and compared and searched for similarities and differences, which formed the basis for developing subcategories and categories. Citations from participants were included.

Ethical Consideration

The study was performed according to the ethical principles of research in the palliative care context21 and supported the participants' integrity and fluctuating condition. Interviewers with experience of caring for severely ill patients performed the interviews. The study was approved by the Regional Ethical Review Board in Lund, Sweden (Dnr: 2015/809, 2016/408). All participants gave informed consent.

RESULTS

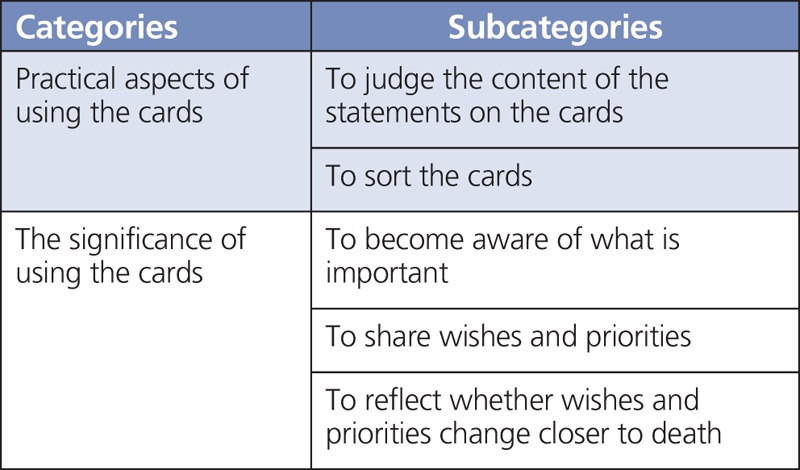

The participants' experiences of using the cards as a conversation tool about wishes and priorities were sorted into 2 categories and 5 subcategories (Table), as described below.

TABLE.

Overview of the Categories and Subcategories When Using Cards as a Conversation Tool

Practical Aspects of Using the Cards

This category describes the participants' judgment of the statements on the cards and the practical aspects of actually sorting the cards into different piles. Although structured in its form, the process varied and was adjusted according to the individual participant's wishes and condition such as physical impairments and/or energy level.

To Judge the Content of the Statements on the Cards

In general, the statements on the cards were perceived as relevant. None of the participants described them as offensive or repulsive, even though some cards called for reflection and discussion, for example, “Not to be a burden to my family” or “To feel that my life is complete.” When a card was perceived as unclear or difficult to understand, a conversation between the participant and interviewer developed. Here, the interviewer, for example, told how other participants had interpreted the statement. Some participants argued that a statement on one card could describe a condition that was a prerequisite for another, such as “To be free from pain” and “To feel at peace.” The statements could also be perceived as being discordant with the participants' serious situation, for example, “To feel at peace,” “To be free from anxiety,” or “To feel that my life is complete.” Others believed that the statements pertained to issues important throughout life, such as “To have my family with me” or “To have my finances in order.” A few participants added their own statements to the blank cards, for example, “To live my life as normally as possible” and “To have fun and enjoy.”

To Sort the Cards

The process of choosing the 10 most important cards varied. For those who had started or completed the process of sorting the cards before the interview, it was a positive experience. Receiving the cards in advance had enabled the participants to exclude cards with statements that they were unwilling to discuss at the moment:

I thought there was a lot about death… these [cards] I removed straight away… why talk about something that is not relevant right now? But of course they should be there; there are those who want to talk about it.

The interviewer suggested putting the cards in 3 piles, but the number of piles varied according to the participants' preferences.

Choosing 10 cards was considered applicable and feasible by most, and the final number of cards participants selected was between 9 and 14. However, for the most ill and frail participants, it was difficult and too strenuous to sort the cards. For instance, it was difficult to hold them in the hand, to keep the cards in memory, or to remember which pile to put them in. For them, there were simply too many cards, as one participant emphatically expressed:

There was a whole darn lot of cards!

The Significance of Using the Cards

The participants described the conversations as somewhat strenuous but necessary, and none of the participants wanted to withdraw from the conversations. Using cards helped to raise awareness of and express wishes and priorities.

To Become Aware of What Is Important

It was frequently expressed by the participants that the cards helped to put thoughts and feelings into words. Some cards also raised awareness of something not thought of before and/or of the importance of having these kinds of conversations:

I think it's a good thing to do it… it may be important to really think about it sometimes: what do I really want from the rest of my life?

Feelings of relief and gratitude were expressed, and on several occasions, the participants were noticeably affected by the conversation. A participant became sad and had to pause the interview, but afterward emphasized the importance and need to put words to problematic subjects and situations:

…there were days when I thought I would die. I had no hope. When I look back on all those days, it affects me… it was scary and lonely… but to talk about it just means putting what happened into words…

Going through the cards opened up conversations. Sometimes a single card embraced an important aspect of their previous or current life or of life in the face of death. A card could have an unexpected association. For example, “Not being short of breath” could call up the claustrophobic feeling of having the nose and mouth covered; “To have a human touch” could symbolize a high quality of life as it might evoke memories of physical contact with children and grandchildren. The conversation and process of choosing 10 cards were described as coming to terms with the most important aspects in life. For one woman, the only important card at the end of the conversation was “To have my family with me.”

To Share Wishes and Priorities

Stories about past and present life situations were generously shared, and feelings of appreciation of having the conversations were expressed. However, it became obvious that the participants perceived that the conversations focused not only on death and dying, but also on their current life situation and the challenges they were facing when struggling to maintain daily routines until time of death:

I think they're [the chosen cards]…, that's what matters to me, the other stuff isn't that important that … not for me anyway… and that's how I want life, otherwise too, just so that I am able to move about and am in a good mood and eat and drink and, like,… live a relatively normal life.

Different views emerged on whether it was beneficial that HCP knew the participants' wishes and priorities. Making their wishes known could enhance the possibility of receiving individualized care, but some participants said it was unnecessary if family members gave the main support. These participants said they preferred discussing their wishes and priorities with family members. They did, however, express a wish to use the cards in conversations with family members in this matter. Where family members were negatively affected by previous experiences of death and dying, the participants perceived any discussion about death with them as challenging. In these cases, the HCP became the obvious conversation partner in end-of-life discussions. Some participants believed that the HCP already knew their preferences, although they had not clearly specified them. The participants felt that the cards should always be introduced by HCP, because you can always say “no thanks” when being asked.

To Reflect Whether Wishes and Priorities Change Closer to Death

During the interviews, discussions about the timing of conversations emerged, and this was considered important if wishes and priorities change during the illness trajectory. For some participants who had lived with the disease for several years, the need for and interest in end-of-life discussions had shifted. Some participants had discussed their wishes and priorities with their family, friends, and/or HCP; others had not, but had the impression that family and HCP already knew what was important to them. For others, the cards started the process:

I've been thinking these days… what's important to me? So, actually, I got a lot out of the cards before you came.

Another important issue was raised: Should the participants describe their wishes and priorities at this current time point, or later when closer to death? One participant suggested that the card sorting should be divided into phases:

…and that's when I began to philosophize on this because, eh, it's actually divided into 2 phases… because you change during the journey… You can say that today I really want to sleep well, but later, when we approach the final stage, then it's totally uninteresting.

However, other participants expressed that the cards covered the entire spectrum from earlier phases, to the current phase, and the future.

DISCUSSION

The results showed that using cards as a tool to initiate and carry through conversations about wishes and priorities with terminally ill patients is both feasible and beneficial. The participants expressed that the cards and card sorting process were useful in facilitating the process of putting thoughts and feelings into words. The conversations aroused memories and brought insight that helped the participants come to an understanding of what was most important. Looking at and sorting the cards for some made it easier to reveal and talk about difficult issues. Even though the conversation evoked feelings of sadness, it was considered important, and the participants expressed their appreciation.

In the present study, the participants received the cards in advance, and this enabled them to choose areas or issues they wanted to talk about or not. To initiate conversation through this approach also enables patients to decide when, how, and with whom to discuss what. This person-centered approach empowered the patients and gave them the opportunity to be in control of the situation. Regardless of whether the statements were immediately understandable or not, the initial discussion of the meaning of the cards served to begin the conversation, which indicates that this is an essential part of using the cards as a conversation tool.

The need and interest to discuss wishes and priorities have been confirmed in recent research in other populations. In a study in healthy adults (n = 68), playing a conversation game about end-of-life issues motivated them to engage in ACP.22 Within 3 months of having played the game, 73% had talked with friends, family, and loved ones about end-of-life issues in general; 27% had played the game again or reviewed the game cards with family and friends; and 20% had updated, reviewed, organized, or created an advance directive. In another study, 37 patients with cystic fibrosis (53% with severe disease)23 reported feeling comfortable talking about ACP topics, but only 2 participants had discussed medical care preferences with HCP. Approximately two-thirds of the participants expressed that the ideal timing to initiate the ACP conversations was when they were generally healthy and had evidence of advancing disease. They also expressed a need for regular reevaluation, which is similar to the results of the present study. Advance care planning conversations about wishes and priorities should be viewed as a process: they may change over time. In a study with 300 patients estimated to be in their last year of life, 19% revised their care preferences before death (usually to less intensive care).24 Using conversation cards gives the patient control of the content of the conversation and can therefore be used in any phase of the disease trajectory and may open up the opportunity to return to these issues repeatedly. The issue of timing needs to be confirmed in future studies.

To our knowledge, this is the first study to explore using cards as a conversational tool in this population, and it shows that patients with palliative care needs can use this tool and need and appreciate the conversations. Alternative tools may be needed, especially in palliative care. Participant-produced photographs were used in one study to explore meaningfulness in the last phase of life,25 and this method was found useful by patients in a phase when their verbal ability decreased and symptom burden and fatigue increased. In the present study, it became obvious that the card sorting process required physical and mental energy. End-of-life discussions with nursing home patients and their relatives may be desirable,7 but changes, such as reducing the number of cards, may need to be made to further facilitate the process for the most ill and frail patients. This aspect needs to be explored in future studies.

The results of this study can be interpreted in line with knowledge about the importance of end-of-life care conversations that have been proved to increase the feeling of safety and decrease feelings of being abandoned in a challenging life situation.6,26 It is hoped that this study may guide HCP in how to initiate and carry through conversations about wishes and priorities in patients with palliative care needs.

Limitations of the Study

The development of the deck of cards was based on solid evidence and was performed in several steps that included experts in the field, as well as patients and patient representatives. This approach enabled a thorough analysis of the feasibility of the content of the cards and the conversation about wishes and priorities. Recruiting and interviewing participants in palliative care can be challenging, and therefore, HCP with experience of palliative care performed the interviews. The interviews were initially performed in pairs to facilitate consistency, and all interviews followed the same instructions for the card sorting process. The participants' differences in age, gender, and time to death have shown that cards may facilitate conversations of wishes and priorities for different individuals and are feasible both a few days and several months before time of death. Future studies are needed to explore the content and conversations according to culture, diagnosis, age, phase of illness, and ethnicity.

CONCLUSIONS

Using cards is an ethical and a feasible method to introduce conversations about wishes and priorities with participants at the end of life. The cards gave the participants the opportunity to express their wishes and priorities but also enabled them to be in control of the situation by choosing the cards they wanted to talk about. This meant they were able to take the conversation in the direction they wanted from the very start, focusing only on the issues they identified as important. They were also able to pinpoint not only what was important, but also what was of most importance to prioritize at end of life.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the participants for so kindly and generously sharing their experiences of using the cards. They also thank the research group and coworkers at the Institute for Palliative Care, Lund University and Region Skåne, Sweden. They are especially grateful to Anna Gannfelt Hansson, Mattias Tranberg, Katarina Ekman, Ann-Mari Bergström, Neda Salehy, and Roy Brander (Lund University and Region Skåne, Sweden) for assistance with recruitment and data collection.

APPENDIX

To meet with clergy or chaplain

To have my family prepared for my death

To have an advocate who knows my values and priorities

To be free from pain

Not being short of breath

To be able to eat and drink

To not feel nausea

To have my financial affairs in order

To feel safe

To have smooth digestion

To feel that my mouth is fresh and clean

To not feel down

To be able to choose place of death

To be able to move around

To have human touch

Not being a burden to my family

To remember personal accomplishments

To prevent arguments by making sure my family knows what I want

To take care of unfinished business with family and friends

To have close friends near

To feel that my life is complete

Not being connected to machines

To say goodbye to important people in my life

To be able to help others

To be mentally aware

To be kept clean

Not dying alone

To be treated the way I want

To trust my doctor

To be able to talk about what death means

To pray

To have my family with me

To have my funeral arrangements made

To be free from anxiety

To know how my body will change

To have someone who will listen to me

To have the energy to do what I want

To be able to sleep well

To have access to all information that I want

To maintain my dignity

To receive help with practical issues

To not have pressure sores

To feel at peace

To have staff I feel comfortable with

To be able to share how I feel with my family and friends

To feel well and comfortable

Blank cards X 3

Footnotes

The study was funded by grants from Kamprad Family Foundation and Mats Paulsson Foundation, Sweden.

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.Brinkman-Stoppelenburg A, Rietjens JA, van der Heide A. The effects of advance care planning on end-of-life care: a systematic review. Palliat Med. 2014;28(8):1000–1025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rietjens JAC, Sudore RL, Connolly M, et al. Definition and recommendations for advance care planning: an international consensus supported by the European Association for Palliative Care. Lancet Oncol. 2017;18(9):e543–e551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sudore RL, Lum HD, You JJ, et al. Defining advance care planning for adults: a consensus definition from a multidisciplinary Delphi panel. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2017;53(5):821–832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Raisio H, Vartiainen P, Jekunen A. Defining a good death: a deliberative democratic view. J Palliat Care. 2015;31(3):158–165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Malhotra C, Farooqui MA, Kanesvaran R, Bilger M, Finkelstein E. Comparison of preferences for end-of-life care among patients with advanced cancer and their caregivers: a discrete choice experiment. Palliat Med. 2015;29(9):842–850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Steinhauser KE, Voils CI, Bosworth H, Tulsky JA. What constitutes quality of family experience at the end of life? Perspectives from family members of patients who died in the hospital. Palliat Support Care. 2015;13(4):945–952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gjerberg E, Lillemoen L, Forde R, Pedersen R. End-of-life care communications and shared decision-making in Norwegian nursing homes—experiences and perspectives of patients and relatives. BMC Geriatr. 2015;15:103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pollock K, Wilson E. Care and communication between health professionals and patients affected by severe or chronic illness in community care settings: a qualitative study of care at the end of life. Health Serv Deliv Res. 2015;3(31). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Matteson CL, Merth TD, Finegood DT. Health communication cards as a tool for behaviour change. ISRN Obes. 2014;2014:579083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Van Scoy LJ, Reading JM, Scott AM, Green MJ, Levi BH. Conversation game effectively engages groups of individuals in discussions about death and dying. J Palliat Med. 2016;19(6):661–667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lankarani-Fard A, Knapp H, Lorenz KA, et al. Feasibility of discussing end-of-life care goals with inpatients using a structured, conversational approach: the Go Wish Card Game. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2010;39(4):637–643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer EORTC QLQ-C15-PAL questionnaire. https://www.eortc.org/app/uploads/sites/2/2018/08/Specimen-C15-PAL-English.pdf. Accesed August 24, 2019.

- 13.Lundh Hagelin C, Klarare A, Furst CJ. The applicability of the translated Edmonton Symptom Assessment System: revised [ESAS-r] in Swedish palliative care. Acta Oncol. 2018;57(4):560–562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brännström M, Fürst CJ, Tishelman C, Petzold M, Lindqvist O. Effectiveness of the Liverpool Care Pathway for the dying in residential care homes: an exploratory, controlled before-and-after study. Palliat Med. 2016;30(1):54–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Beck I, Olsson Möller U, Malmström M, et al. Translation and cultural adaptation of the Integrated Palliative care Outcome Scale including cognitive interviewing with patients and staff. BMC Palliat Care. 2017;16(1):49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lindqvist O, Tishelman C. Going public: reflections on developing the DoBra research program for health-promoting palliative care in Sweden. Prog Palliat Care. 2016;24(1):19–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Menkin ES. Go Wish: a tool for end-of-life care conversations. J Palliat Med. 2007;10(2):297–303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Polit DE, Beck CT. Nursing Research. Generating and Assessing Evidence for Nursing Practice. 10th ed Philadelphia, PA:Wolters Kluwer Health; 2017:275. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhang L, Gallagher R, Lowres N, Orchard J, Freedman SB, Neubeck L. Using the ‘think aloud’ technique to explore quality of life issues during standard quality-of-life questionnaires in patients with atrial fibrillation. Heart Lung Circ. 2017;26(2):150–156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hsieh HF, Shannon SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res. 2005;15(9):1277–1288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gysels M, Evans CJ, Lewis P, et al. MORECare research methods guidance development: recommendations for ethical issues in palliative and end-of-life care research. Palliat Med. 2013;27(10):908–917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Van Scoy LJ, Green MJ, Reading JM, Scott AM, Chuang CH, Levi BH. Can playing an end-of-life conversation game motivate people to engage in advance care planning? Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2017;34(8):754–761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Linnemann RW, Friedman D, Altstein LL, et al. Advance care planning experiences and preferences among people with cystic fibrosis. J Palliat Med. 2019;22(2):138–144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hopping-Winn J, Mullin J, March L, Caughey M, Stern M, Jarvie J. The progression of end-of-life wishes and concordance with end-of-life care. J Palliat Med. 2018;21(4):541–545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tishelman C, Lindqvist O, Hajdarevic S, Rasmussen BH, Goliath I. Beyond the visual and verbal: using participant-produced photographs in research on the surroundings for care at the end-of-life. Soc Sci Med. 2016;168:120–129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Detering KM, Hancock AD, Reade MC, Silvester W. The impact of advance care planning on end of life care in elderly patients: randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2010;340:c1345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]