Abstract

Objective:

To conduct a systematic literature review to assess the conceptualization, application, and measurement of resilience in American Indian and Alaska Native (AIAN) health promotion.

Data Sources:

We searched 9 literature databases to document how resilience is discussed, fostered, and evaluated in studies of AIAN health promotion in the United States.

Study Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria:

The article had to (1) be in English; (2) peer reviewed, published from January 1, 1980, to July 31, 2015; (3) identify the target population as predominantly AIANs in the United States; (4) describe a nonclinical intervention or original research that identified resilience as an outcome or resource; and (5) discuss resilience as related to cultural, social, and/or collective strengths.

Data Extraction:

Sixty full texts were retrieved and assessed for inclusion by 3 reviewers. Data were extracted by 2 reviewers and verified for relevance to inclusion criteria by the third reviewer.

Data Synthesis:

Attributes of resilience that appeared repeatedly in the literature were identified. Findings were categorized across the lifespan (age group of participants), divided by attributes, and further defined by specific domains within each attribute.

Results:

Nine articles (8 studies) met the criteria. Currently, resilience research in AIAN populations is limited to the identification of attributes and pilot interventions focused on individual resilience. Resilience models are not used to guide health promotion programming; collective resilience is not explored.

Conclusion:

Attributes of AIAN resilience should be considered in the development of health interventions. Attention to collective resilience is recommended to leverage existing assets in AIAN communities.

Keywords: american indian, alaska natives, resilience, literature review

Introduction

Some say that Coyote wears a black leather jacket and hightop tennis shoes That Coyote thinks that Rose is a good singer That Coyote eats frybread peanut butter and jelly That Coyote will use you if you don’t watch out That Coyote will teach you if you let him That Coyote is very young the new one That Coyote is a survivor Some say Coyote is a myth Some say Coyote is real

—Harry Fonseca1(p92)

American Indians and Alaskan Natives (AIANs) have shown notable resilience in the face of sociopolitical oppression, hostility, and other forms of adversity. Coyote narratives play a central role in the ways AIAN communities create meaning of collective past, lived experiences, and resilience. In this poem, Fonseca as presented in Lincoln1, reveals a complex character that is at once old and young, wise and vulnerable, uncompromising and adaptable. Such anthropomorphized stories communicate not only shared social realities but also the collective resilience of AIAN people propelling communities forward despite great challenges. The coyote is human potential made tangible in animal form. As American Indian author Thomas King wrote: “When that Coyote dreams, anything can happen.”2(p1) The flexibility, strength, and capacity for hope demonstrated in the coyote narratives are inextricably tied to the concept of resilience.3,4

In this review, we relied on Ungar’s5(p387) definition of resilience as “processes that individuals, families and communities use to cope, adapt and take advantage of assets when facing significant acute or chronic stress, or the compounding effect of both together.” Ungar6 argues that resilience research and theory development require an understanding of the complex interplay between actors (eg, individual, families, and communities) and physical and social ecologies. He6 further advocates that the resources and opportunities of the context should be the primary focus of resilience research, thus supporting public health action that strives to change social determinants of health to improve health outcomes at multiple levels.7 Although resilience tends to be framed as an individual characteristic, Kirmayer et al8(p85) in their research with Indigenous populations in Canada built on Walsh’s9 work in family resilience to highlight the systemic and collective dimensions of community resilience, concluding that “resilience may reside in the durability of interpersonal relationships in the extended family and wider social networks of support.”

Resilience has been fundamental to the very survival of native people in the United States. The integration of this resource into health promotion programming designed specifically for native people could provide innovative approaches to chronic public health challenges. The question that prompted this work was “how has AIAN resilience been documented and leveraged in public health research and intervention designed to improve AIAN health outcomes?” The purpose of this systematic review is to describe the application of AIAN resilience in the public health literature.

American Indians and Alaskan Natives have withstood the legacy of colonization, many phases of federal policies authorizing termination, relocation and assimilation, and rapid socio-economic change impacting subsistence patterns, employment, education, and even value systems. Before 1770s, AIANs lived by intrinsic systems of governance, social norms, cultural practices, and spiritual beliefs. For the next 200 years, AIANs faced termination, reorganization, relocation, and assimilation policies, characterized by treaties that established reservations which required relocation and regulated tribes to a fraction of their traditional homelands, and Bureau of Indian Affairs boarding schools that removed children from families to teach Euro-American values, language, and behaviors.10 In 1975, the passing of the Indian Self-Determination and Education Assistance Act granted tribes authority over the administration of federal funds, giving them greater control over their welfare.11 Over the last 40 years, AIANs have exercised this right through increased tribal direction over education and health-care delivery systems and in the development of culture and language revitalization programs.11,12 Historic and contemporary evidence demonstrates AIANs’ resilience and ability to respond individually and collectively to persistent adversity.

The concept of resilience has been applied to both individual and group capacity to recover from stressors or adversity.13–16 Group capacity is referred to as both “community resilience” and “collective resilience,” often interchangeably.13,14 Given that the literature offering guidance for future research suggests that resilience is linked to shared identity and cultural practice, as well as characteristics of the local social network, “collective resilience” is the term used in this review.15–17

Methods

Data Sources

The review was prepared following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses statement and modified checklist.18 We searched 9 databases (BioMed Central, the Encyclopedia of Social Measurement, Medline/PubMed, EMBASE, Web of Science, EBSCO [PsycINFO and CINAHL], Ovid, the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, and the Campbell Library of the Campbell Collaboration). To maximize the retrieval of potentially relevant articles, we used a combination of free texts, index terms, and truncated terms as appropriate. The following terms and concepts searched were as follows: collective [or] communal resilience and Native American [or] Alaska Native [or] American Indian [or] Indigenous; resilience and psychosocial; resilience and mental health; resilience and chronic disease; and resilience and intervention and Native American [or] Alaska Native [or] Indigenous. Three reviewers (J.A.T., H.C.M., and N.I.T.) conducted the literature searches. Over a total of 6 months, 2 reviewers extracted the data independently and worked collaboratively to develop a single table of outcomes. The third reviewer examined only the identified articles to verify relevance to inclusion criteria.

Study Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

The selection criteria were developed to identify research that purposefully sought to understand and assess resilience through the administration of questions and/or measurements scales. To be included in the review, the article had to (1) be in English; (2) peer-reviewed original research and/or intervention, published from January 1, 1980, to July 31, 2015; (3) identify the target population as predominantly AIANs in the United States; (4) describe a nonclinical intervention or original research that identified resilience as an outcome measure or a resource to guide intervention design or research; and (5) discuss resilience as related to cultural, social, and/or collective strengths. These selection criteria were identified by the review team.

Studies were limited to the United States to avoid overgeneralization of indigenous peoples’ responses to the differential adversity of colonization. In the United States after a period of conflict and warfare, tribes were compelled to enter into formal treaty agreements or to yield to executive orders and endured a unique set of stressors linked to the residential, educational, and governance policies of the US government.19 Our review was limited to nonclinical encounters as the intent was to identify culturally and socially organic concepts of resilience and not resilience that may have been guided in a controlled environment.

Data Extraction

Data were extracted in a standardized format and organized into tables that included authors’ names; year of publication; title of the article; size, age range, and location of sample; study design and methodology; and key findings related to resilience.

Data Synthesis

Following Walker and Avant’s20 method of concept analysis, attributes of resilience that appeared repeatedly in the literature were identified. Similarly, age of the study population was a distinguishing characteristic of the studies. Subsequently, findings were categorized across the lifespan divided by attributes and further defined by specific domains within each attribute.

Results

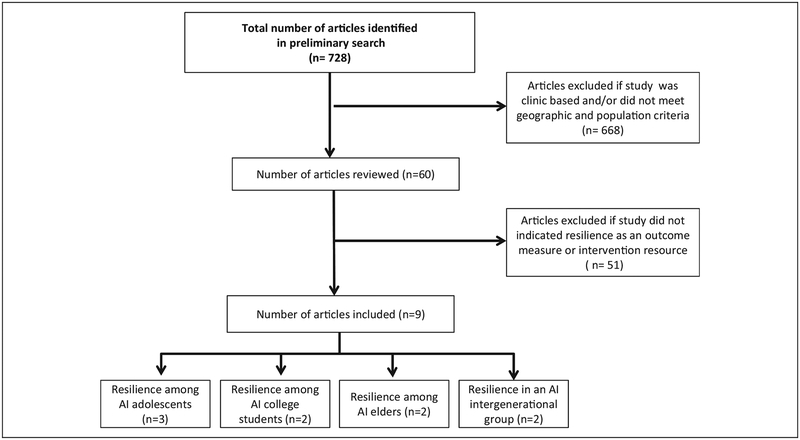

A total of 728 potential articles were identified in the initial search. Figure 1 shows the flow of articles through the systematic review process. Sixty abstracts were selected for a full-text review, and among those studies, 9 articles met the inclusion criteria. Three studies described the work with American Indian (AI) adolescents, 2 with AI college students and 1 with AI elders that yielded 2 articles and 2 explored resilience with AI and Alaska Native (AN) intergenerational groups. Six of the 9 databases yielded 8 of the articles; the ninth article was identified through the citations of another article. Each database yielded 2 to 6 articles. No one database cited all 9 articles.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of inclusion and exclusion of peer-reviewed publications identifying AIAN resilience as a resource or outcome measure. AIAN indicates American Indian and Alaska Native.

No peer-reviewed article extracted from this review of 35 years of scientific literature describing AIAN health behaviors and outcomes addressed collective resilience directly. All studies focused on AIAN personal resilience and indirectly discussed collective resilience through the identification of cultural assets drawn from a shared identity or social assets linked to peers, family, and community. The recurring attributes of AIAN resilience were “social support” and “cultural engagement.” Table 1 provides a checklist of attributes and specific domains identified in each reviewed article.

Table 1.

Attributes Linked to Resilience in AIAN Populations Across the Lifespan.

| Adolescents | College Students | Elders | Intergenerational | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Domains of the Attributes | Waller et al21 | LaFramboise et al22 | Stumblingbear-Riddle et al23 | Montgomery et al24 | Muehlenkamp et al25 | Grandbois and Sanders26,29 | Goodkind et al27 | Wexler28 |

| Social support | ||||||||

| Support-family | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Support-peer | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

| Support-school (administration and faculty) | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||

| Support-community | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Cultural engagement | ||||||||

| Enculturation/strong cultural identity | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Engagement in cultural activities and hearing stories | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

| Spiritual and traditional beliefs | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

| Holistic worldview | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||

| Ability to navigate different cultures | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

| Cultural values help averts assuming a victim identity | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||

Abbreviation: AIAN, American Indians and Alaskan Native.

Social Support

Social support emerged as an attribute of resilience in all selected articles; however, the specific form and level of this support varied across the lifespan.

Adolescents.

In the 3 articles that focused on AI adolescents, family, peer, school, and community emerged as important supports for different reasons. In Waller and colleagues’21 intervention designed to enhance educational resilience, school-based support was tangible in the form of tuition waivers, transportation, and meals. A network of AI faculty, peers, families, and school staff was developed to mirror the social support and mentorship inherent in traditional communities. Reliance on these relationships was identified as a key to overcoming psychosocial barriers to educational achievement.

LaFromboise et al22 and Stumblingbear-Riddle and Romans23 examined academic success as a proxy for resilience in large adolescent samples in reservation (N = 212) and urban (N = 196) settings, respectively. LaFromboise et al22 found correlations between community support, maternal warmth (an element of family support), and increased prosocial behaviors assessed through school involvement, positive educational attitudes, and academic plans or success. LaFromboise et al22(p196) discussion integrated the pros and cons of family connectedness for students but did indicate that family support played a role in academic achievement; “the task for youth in high-risk families was to: (1) avoid becoming overwhelmed by the stresses of the family, (2) maintain compassion for the family yet remain detached from family troubles, (3) develop understanding of the family’s problems, and (4) receive some emotional support from well family members.” Stumblingbear-Riddle and Romans23 identified peer support as the strongest indicator of adolescent resilience highlighting that friends influenced attitudes toward school, academic goals, and grades.

College students.

Montgomery et al24 interviewed AI college students to identify characteristics of resilience to inform retention efforts in academic settings. Family support and community support in the form of encouragement from elders were prominent themes identified in the analysis of the narrative data. Concluding statements from this study focused on resilience as a reflection of internal and essentially personal characteristics shaped by the social environment and life events.

In the development of a suicide prevention program designed specifically for AI college students, Muehlenkamp et al25 also identified social support as important for this group who are disconnected from their families and home community. The suicide prevention program did yield a significant increase in AI students’ problem-solving skills. This increase in student capacity was ascribed to the building of on-campus social networks through an AI student support team and to identify campus-based mental health resources for students.

Elders.

In Grandbois and Sanders29 interviews with AI elders, respondents discussed the life lessons provided by their parents and highlighted social support provided by the family as key to resilience. Their own parents taught them to be responsible and accountable and established a strong sense of self that helped them face challenges.

Intergenerational groups.

Two articles described work with intergenerational groups and explored age-related differences in perceptions of social behaviors and resilience in AIAN populations. Goodkind et al27 conducted interviews with Diné (Navajo) adolescents, parents, and grandparents residing on the reservation. Grandparents spoke of historical trauma and colonization as resulting in current poor physical and mental health, including high rates of substance abuse, diabetes, violence, and depression. Grandparents identified once more prominent social behaviors as having contributed to resilience in the past: they talked to each other in a good manner, and visited one another; respected one another. They even took care of one another, from these things they thought clearly, they had good lives, and they felt good about themselves. The respect they had for their relations was important to them, so they spoke and related to one another in a respectful manner. Today, it is different. Even though the people live close to one another or even if they are relatives, they seem to be jealous of one another, and they do not talk to one another. Because of the past, this is probably why today our people are struggling or have really hard lives.27(p1028,1029)

Grandparents identified family support as central to coping with stress. They mentioned family gatherings and financial support but emphasized talking to family members who needed help, a behavior also mentioned by parents and youth.

Parents in this same study less frequently perceived historical events affecting them or their families but thought current trauma and violence occurring in their communities were more salient. Echoing the strategy of the grandparents, parents identified intergenerational communication as being effective in avoiding negative behaviors or recovering from negative circumstances.

Adolescents did not mention historical trauma in discussion of challenges and resilience and relied primarily on family or household support to cope with stressors. While this included financial support, “talking to” family members was again emphasized. Youth also identified friends as a way to cope: “We just talked to each other. Calm each other down, that stuff.”27(p1032)

Wexler28 conducted focus groups and in-depth interviews with Inupiaq (AN) elders, adults, and youth with questions and protocols adapted from the Roots of Resilience Study.30 Similar to the findings of Goodkind et al,27 AN elders identified colonialism, historical trauma, and boarding schools as elements of significant adversity that tested their people’s resilience. Alaska Native elders identified their own parents teaching them to work hard to survive and to gain back what was lost. One AN elder summarized the sentiment as “do well, despite discrimination.”28(p82)

The adult cohort in this study engaged in collective politicization as one way to deal with historically embedded inequities, essentially a unique culturally grounded form of peer support. This expression of group identity politics offered adults a space to resist dominant society and forms of colonialism while regaining cultural assets denied in their childhood and adolescence.

Similar to the work of Goodkind and colleagues,27 AN youth in Wexler’s28 research did not identify historical trauma as a salient factor in current challenges. Instead, family problems, depression, and addiction arose as personal stressors, and lack of jobs or opportunities for adolescents exacerbated these challenges. While the environment served as a stressor for AI youth participants, Wexler28 found that AN resilience was linked to a literal return to home after time spent away and receiving family support while reconnecting with community and the culture.

Cultural Engagement

Adolescents.

Adolescent resilience is linked primarily to a multifaceted social support system including family, peers, school, and community, yet cultural engagement and strong cultural identity were attributes repeated in the literature. Waller et al21 designed an urban high school-based program that nurtured AI students’ indigenous worldview and spiritual understanding as the basis for academic achievement and protection from negative influences. All (100%) program participants graduated from high school and college matriculation were 90% compared to 61% of AI students who did not participate.21 Educational resilience was linked to the mobilization of cultural and social resources. Intervention strategies aimed to strengthen cultural identity and establish a network of AI faculty, peers, families, and staff, which mirrored tribal support in traditional communities.

In contrast, Stumblingbear-Riddle and Romans23 found that cultural engagement was only modestly significant in its correlation with resilient outcomes measured by academic success. The authors explain that although cultural identity may be an important resource in youth resilience, urban-dwelling AI adolescents have limited opportunities to engage in cultural activities. The respondents had limited cultural experiences to report.

College students.

Both Montgomery et al24 and Muehlenkamp et al25 report that AI college students perceive that a strong cultural identity in an academic setting contributes to success. American Indian students described “education as part of the journey of life and knowing and remembering one’s Indianness through this journey is important” to coming back to work with your own people.24(p393,394) The AI students interviewed by Montgomery et al24(p393) were acutely aware of the need to become competent in 2 worlds described as “riding the fence.” Students created a tapestry yielding a third world existing between the Indian culture and the predominantly white Western culture of academia.24(p393)

The suicide prevention program of Muehlenkamp et al25 targeting AI college students emphasized spiritual, mental, physical, and emotional resources to enhance resilience. Based on the program’s outcome of increased problem-solving skills of AI students, the authors cited enhanced cultural connectedness established through on-campus cultural programming and spiritual ceremonies as key strategies to AI suicide prevention.

Elders.

Grandbois and Sanders26,29 assert that the prominence of the native holistic world view of the interconnectedness and interdependence of life systems and the strength derived from the survival of the ancient ones emerged as meaningful attributes of resilience from elders’ narratives. Grandbois and Sanders26 identified strategies used by AI elders to remain resilient in the face of discrimination and to avoid assuming a victim identity. “Bridging cultures” aforementioned by AI college students was also identified by elders highlighting the ability to navigate distinct values, customs, beliefs, and behaviors to survive and thrive in both AI and non-AI settings. One elder man describes his experience of attending a “mostly White public high school” after completing primary education on a reservation: “It was probably like going to the moon (laughing) … it was an entirely new experience … like going between worlds, you had to live in two worlds.”26(p392)

Strong cultural identity was an attribute of AI elders linked to resilience:

When a child is given their name in the traditional way they receive great strength (resilience). It helps us to know who we are, to know that we are connected to our people, even those who have gone before us.26(p393)

Intergenerational groups.

In the work spirituality of Goodkind et al,27 religion and traditional beliefs were associated with resilience and integral to the coping strategies of AI grandparents and parents. One grandmother spoke of spiritual protection as helping the family unit: “Our family has a Dzil Leezh (sacred mountain soil bundle) which protects, brings good to, or takes care of a home or a person or a family.”27(p1029)

Wexler28 noted that AN elders relied on cultural connectedness to offset ecosocial stressors outside their control, particularly as culture related to god, family, and traditional values. Traditions as passed down from the elders’ parents and ancestors served 2 main purposes: the first, to root elders in their culture and, the second, to provide wisdom and guidance to navigate 2 cultures. The latter was particularly salient as participants explained they avoided assuming a victim identity by relying on cultural values. One elder summarized this sentiment, “so, when you are up against something, you got to dwell on your values, [the ones] that you learned when you were growing up.”28(p81)

Discussion

To date, studies of AIAN resilience are limited in scope and number; collective resilience is absent from the AIAN literature. The 3 studies21–23 that examined resilience among AI adolescents and youth used school competence and behavior as an indicator of resilience linking academic achievement to future success. Academic achievement may be too narrow as an indicator of success. The work of Bottrell and Armstrong31 argues that coping strategies deemed risky or maladaptive by dominant society, for example, gang involvement, and even abstaining from academic success may be resilient in alternate contexts. Ungar states that, “empirical evidence that young people’s problematic behavior and peer group ‘delinquency’ may be health enhancing ways of coping in problematic environments.”13(p249) Bottrell and Armstrong31(p249) assert that “academic performance, school attainment, and prosocial behavior and relationships” have become outcome measures for resilience because these are societally acceptable definitions of success. They advocate for a broader social ecological conceptualization of resilience, incorporating “school and institutional cultural features and the impact of systemic processes on schools, such as resource allocations, national testing, and accountability regimes.”31(p250) Waller et al21 provide some insight at the programmatic level documenting the success of an urban, school-based program that promotes AI youth resilience by reducing structural and financial barriers and replicating traditional support systems through educators, school staff, and local government.

The inconclusive role of cultural connectedness in influencing adolescent resilience suggests that urban- and reservation-based AIs have differential access to activities that sustain meaningful engagement with cultural activities. As increasing number of AIs are being raised in urban environment, this difference in cultural and social contexts warrants further exploration relative to health indicators relevant to youth.

There is a dearth of resilience research pertaining to AIAN young and middle-aged adults. The studies in this review that addressed adult populations did so in college settings.24,25 These studies highlight the significance of cultural connectedness and social support from family, peers, and community in contributing to resilience and subsequent academic achievement among college students. Yet, if resilience is considered critical to healthy growth and development throughout the life course, a glaring absence is the resilience of AIAN adults, particularly those who have children. Adults are in a unique position to potentially serve as caregivers for both children and community elders and serve as a generational and cultural bridge. Identifying attributes of resilience at this life stage is critical to promoting resilience in the larger population.

The work of Grandbois and Sanders26,29 with AI elders high-lights that successfully negotiating 2 cultures, strong cultural and self-identity, parenting that teaches responsibility and accountability, and education and employment foster resilience. These outcomes echo the work of Wild et al32 with nonnative populations, who stress the importance of “gerontological resilience,” emphasizing that resilience research with older individuals should more explicitly focus on exploring the experience of rather than the avoidance of vulnerability.

Literature on strength-based research with AIAN communities is limited. The public health literature continues to emphasize structural and collective deficits.33 Yet, strength-based research could inform discourses of AIAN health as well as the creation and implementation of programs and policies intended to improve health outcomes with this population.

Antonovsky34 proposes a theoretical shift in field of health promotion criticizing the ubiquitous use of risk factors to discuss health and positing a greater emphasis on factors that enhance health. He cites the importance of disentangling health promotion research and practice from disease prevention frameworks, advocating the advancement of strength-based approaches. Antonovsky’s34 work creates a space for resilience research within the health sciences, begging the questions: how and why are individuals, families, and communities adjusting and even thriving in times of hardship?

Attributes identified in this review as promoting resilience in AIAN populations have been identified in work with nonnative communities; these include prosocial attitudes and behaviors, strong supportive networks, and cultural adaptability and flexibility.13 Yet, the 8 studies discussed in this review lend insight into resilience attributes unique to AIANs specifically bound to social and cultural assets. These findings elicit the social determinants of health by moving resilience research toward an “ecosocial resilience” model. Ungar13 argues that resilience research should focus on the socioecological conditions that contribute to positive growth and development under adversity and proposes a definition of resilience that emphasizes the environmental antecedents. Kirmayer et al15 also situate resilience within the social determinants of health framework, citing public health strategies with indigenous populations:

Specific social determinants of health point to particular sources or processes of resilience. In the case of indigenous peoples, some of these strategies of resilience draw from traditional knowledge, values, and practices, but they also reflect ongoing responses to the new challenges posed by evolving relationships with the dominant society and emerging global networks of indigenous peoples pursuing common cause.15(p85)

Goodkind et al27 embrace this social–ecological framing of resilience in their study, positing that “if social injustice is one of the root causes of distress, healing must be explicitly guided by transformative social change efforts that build on individual, family, and community strengths.”(p1019)

Limitations

The limitations of this review are the few number of articles that met the inclusion criteria and the heterogeneity in the interpretation of resilience. For younger participants, resilience was ascribed as an outcome of academic success or low incidence of high-risk behaviors. In contrast with elder and intergenerational groups, participants self-identified as resilient and described strategies used in the face of adversity. The absence of a similar definition of resilience and different methods of inquiry is indicative of exploring an emerging concept, and in this case, lack of agreement on the precursors and conditions that support resilience.

Conclusion

Nine articles analyzed in this review identified social support and cultural engagement as attributes of individual AIAN resilience. The paucity of literature calls for an expansion of resilience research with AIAN populations and reflects the general prevalence of the deficit approach used in health research and in particular with underserved populations often described as lacking sufficient resources to achieve optional health. Furthermore, the absence of studies exploring AIAN collective resilience ignores the salutogenic potential of social and cultural capital. As suggested by Antonovsky34 who advocates focusing on social, cultural, and physical resources that maintain and improve health, public health promotion might embrace a theoretical shift away from the risk factors to health-enhancing factors. Models of AIAN resilience need to be further developed, tested, and if effective, integrated into public health interventions. For AIANs, a paradigm grounded in resilience is evidence based and draws us back to the coyote, whose antics embody the shared realities and collective ability to thrive in a context of persistent adversity.

So What? Implications for Health Promotion Practitioners and Researchers.

What is already known on this topic?

Current literature examines protective factors associated with young AIANs’ academic accomplishments and older AIANs’ retrospection on reaching elder status. This small body of literature has contributed to a recognition that social support and culture are key to individual well-being and resilience in AIANs; application of these concepts has been limited.

What does this article add?

This article illustrates the trends in attributes linked to AIAN resilience. Social support was identified by AIANs of all ages. In contrast, predominantly elders mention cultural engagement as providing strength in reaching life goals. This review reveals that collective resilience has not been adequately discussed in the AIAN health literature.

What are the implications for health promotion practice or research?

Given the marginal success of health promotion efforts that seek to reduce risk factors and the limited focus on AIAN resilience, the implications for health promotion practice and research are to focus on healthy AIANs and AIAN communities to identify local assets that have contributed to AIAN resilience and well-being.

Funding

The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This research was supported under by the Center for American Indian Resilience funded by the National Institute on Minority Health Disparities of the National Institutes of Health under award number P20MD006872.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- 1.Lincoln K. Sing With the Heart of a Bear: Fusions of Native and American Poetry, 1890–1999. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 2.King T. Green Grass, Running Water. New York, NY: Houghton Mifflin; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hodge FS, Pasqua A, Marquez CA, Geishirt-Cantrell B. Utilizing traditional storytelling to promote wellness in American Indian communities. J Transcult Nurs. 2002;13(1):6–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Struthers R. The artistry and ability of traditional women healers. Health Care Women Int. 2003;24(4):340–354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Researching Ungar M. Researching and theorizing resilience across cultures and contexts. Prev Med. 2012;55(5):387–389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ungar M. The social ecology of resilience: addressing contextual and cultural ambiguity of a nascent construct. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 2011;81(1):1–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.World Health Organization, Commission on Social Determinants of Health Closing the Gap in One Generation. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kirmayer LJ, Sedhev M, Whitely R, et al. Community resilience: model, metaphors and measures. J Aborig Health. 2009;7(1): 62–117. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Walsh F. Strengthening Family Resilience. 2nd ed, New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shelton and Kaiser Family. 2004. Web site: https://kaiserfamilyfoundation.files.wordpress.com/2013/01/legal-and-historical-roots-of-health-care-for-american-indians-and-alaska-natives-in-the-united-states.pdf. Accessed February 22, 2014.

- 11.Danziger E. A new beginning or the last hurrah: American Indian response toreformlegislationofthe 1970s. AICRJ. 1984;7(4):69–84. [Google Scholar]

- 12.US Bureau of Census. Characteristics of American Indians and Alaska Native by Tribe and Language: 2000 Part 1. Washington, DC: U.S. Bureau of the Census; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ungar M. Social ecologies and their contribution to resilience In: Ungar M, ed. The Social Ecology of Resilience: A Handbook of Theory and Practice. New York, NY: Springer; 2012:13–32. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Norris FH, Stevens SP, Pfefferbaum B, Wyche KF, Pfefferbaum RL. Community resilience as a metaphor, theory, set of capacities, and strategy for disaster readiness. Am J Community Psychol. 2008;41(1–2):127–150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kirmayer LJ, Dandeneau S, Marshall E, Phillips MK, Williamson KJ. Rethinking resilience from indigenous perspectives. Can J Psychiatry. 2011;56(2):84–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Magis K. Community resilience: an indicator of social sustainability. Soc Natur Resour. 2010;23(5):401–416. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kahn-John M, Koithan M. Living in health, harmony, and beauty: the Diné (Navajo) hózhó wellness philosophy. Glob Adv Health Med. 2015;4(3):24–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG; PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151(4):264–269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gone JP, Trimble JE. American Indian and Alaska Native mental health: diverse perspectives on enduring disparities. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2012;8:131–160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Walker LO, Avant KC. Strategies for Theory Construction in Nursing. 4th ed. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Education; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Waller M, Okamoto S, McAllen-Walker R, et al. The hoop of learning: a holistic, multisystemic model for facilitating educational resilience among indigenous students. J Sociol Soc Welfare. 2002;29(1):97. [Google Scholar]

- 22.LaFromboise TD, Hoyt DR, Oliver L, Whitbeck LB. Family, community, and school influences on resilience among American Indian adolescents in the upper midwest. J Community Psychol. 2006;34(2):193–209. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stumblingbear-Riddle G, Romans JS. Resilience among urban American Indian adolescents: exploration into the role of culture, self-esteem, subjective well-being, and social support. Am Indian Alsk Native Ment Health Res. 2012;19(2):1–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Montgomery D, Miville ML, Winterowd C, Jeffries B, Baysden MF. American Indian college students: an exploration into resiliency factors revealed through personal stories. Cultur Divers Ethnic Minor Psychol. 2000;6(4):387–398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Muehlenkamp JJ, Marrone S, Gray JS, Brown DL. A college suicide prevention model for American Indian students. Prof Psychol Res Pr. 2009;40(2):134–140. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Grandbois DM, Sanders GF. Resilience and stereotyping: the experiences of Native American elders. J Transcult Nurs. 2012; 23(4):389–396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Goodkind JR, Hess JM, Gorman B, Parker DP. “We’re still in a struggle”: Diné resilience, survival, historical trauma, and healing. Qual Health Res. 2012;22(8):1019–1036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wexler L. Looking across three generations of Alaska Natives to explore how culture fosters indigenous resilience. Transcult Psych. 2014;51(1):73–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Grandbois DM, Sanders GF. The resilience of Native American elders. Issues Ment Health Nurs. 2009;30(9):569–580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dow S, Dandeneau S, Phillips M, Kirmayer LJ, McCormick RI. Stories of Resilience Project: Manual for Researchers, Interviewers & Focus Group Facilitators (Part 1: Project Overview; Part 2: Checklists & Templates). Montreal, Canada: Culture and Mental Health Research Unit, Jewish General Hospital; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bottrell D, Armstrong D. Local resources and distal decisions: the political ecology of resilience In: Ungar M, ed. The Social Ecology of Resilience: A Handbook of Theory and Practice. New York, NY: Springer; 2012:247–264. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wild K, Wiles JL, Allen RES. Resilience: thoughts on the value of the concept for critical gerontology. Ageing Soc. 2013;33(1): 137–158. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cobb N, Espey D, King J. Health behaviors and risk factors among American Indians and Alaska Natives, 2000–2010. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(S3):S481–S489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Antonovsky A. The salutogenic model as a theory to guide health promotion. Health Promot Int. 1996;11(1):11–18. [Google Scholar]