Abstract

Dispatcher assisted cardiopulmonary resuscitation (DACPR) by Emergency medical services has been shown to improve rates of early out of hospital cardiac arrest (OHCA) recognition and early cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) for OHCA. This study measures the impact of introducing DACPR on OHCA recognition, CPR rates and on patient outcomes in a pilot region in Kuwait.

EMS treated OHCA data over 10 months period (February 21–December 31, 2017) before and after the intervention was prospectively collected and analyzed.

Comprehensive DACPR in the form of: a standardized dispatch protocol, 1-day training package and quality assurance and improvement measures were applied to Kuwait EMS central Dispatch unit only for pilot region. Primary outcomes: OHCA recognition rate, CPR instruction rate, and Bystander CPR rate. Secondary outcome: survival to hospital discharge.

A total of 332 OHCA cases from the EMS archived data were extracted and after exclusion 176 total OHCA cases remain. After DACPR implementation OHCA recognition rate increased from 2% to 12.9% (P = .037), CPR instruction rate increased from 0% to 10.4% (P = .022); however, no significant change was noted for bystander CPR rates or prehospital return of spontaneous circulation. Also, survival to hospital discharge rate did not change significantly (0% before, and 0.8% after, P = .53)

In summary, DACPR implementation had positive impacts on Kuwait EMS system operational outcomes; early OHCA recognition and CPR instruction rates in a pilot region of Kuwait. Expanding this initiative to other regions in Kuwait and coupling it with other OHCA system of care interventions are needed to improve OHCA survival rates.

Keywords: dispatcher-assisted cardiopulmonary resuscitation, Kuwait, out of hospital cardiac arrest, return of spontaneous circulation, survival to hospital discharge

1. Introduction

Out-of-hospital cardiac arrest (OHCA) is a time-sensitive emergency condition with low survival rates.[1] Currently, OHCA recognition and management strategies are summarized by the American Heart Association (AHA) chain of survival; early recognition, early cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR), early defibrillation, and early advanced care.[2,3] Furthermore, OHCA has long term and short-term outcomes. Return of spontaneous circulation (ROSC) is the short-term OHCA outcome and survival to hospital discharge is the long-term outcome. Subsequently enhancing any link of the OHCA chain of survival, by emergency medical services (EMS), requires assessment of these outcomes.[4]

Global OHCA survival to hospital discharge rates remain low (7%)[1] with few EMS systems in some regions of the United States and Europe reporting high OHCA long-term outcomes, survival to hospital discharge rates (24.3% and 21.4%, respectively).[5–7] Paying closer attention to these EMS systems’ strategies reveals a trend towards customizing OHCA chain of survival recognition and management elements according to the local community structure and available resources.[7–9] And while all the OHCA chain of survival links are important, great emphasis on the early links have been also observed in these systems.[10,11]

One element of the early links is dispatcher-assisted cardiopulmonary resuscitation (DACPR). The 2015 AHA Guideline Update for CPA and Emergency Cardiovascular Care indicates that DACPR in OHCA resuscitation is beneficial as a Class 1 recommendation (the benefits greatly outweigh the risk), based on the scale established by the consensus on CPR and emergency cardiac care science with treatment recommendations.[12] In fact, center of excellence, Seattle's King County EMS database, recommends DACPR implementation in EMS systems that want to initiate the OHCA chain of survival but have limited resources.[8,9]

And despite these recommendations, many emergency dispatch centers have DACPR protocol in place but frequently fail to offer DACPR instructions.[4] This makes DACPR implementation in developing EMS system not straight forward process. Determining the presence of cardiac arrest and providing CPR instructions over the phone can be difficult and stressful.[4] Therefore, DACPR has been previously evaluated in the current literature. The present study's literature review revealed that more than 30 studies on DACPR were published in 2017 alone with no studies from the Middle East region. This is the first regional study to examine the impact of DACPR implementation on: OHCA recognition rate, CPR instruction rate, bystander CPR rate, (primary outcomes), and on survival to hospital discharge (secondary outcome) in a pilot region in Kuwait.

2. Method

2.1. Study design and setting

This was a prospective before and after interventional study in pilot region of Kuwait. Kuwait has 6 provinces: Al-Asimah, Hawali, Al-Ahmedi, Al-Farwanya, and Al-Jahra. Hawali province was selected as the pilot region. Hawali province is a heterogeneous urban area with 192,778 Kuwaitis and 480,132 non-Kuwaitis.[13,14] Its ratio of Kuwaitis to non-Kuwaitis (1:2.5) is similar to the overall ratio in the country. Hawali's population demographics are also similar to those of the population of Kuwait.[15]

The EMS service in Kuwait is a public service entity and a 2-tiered system. Hawali province has 8 ambulance stations, with 30 ambulances, 65 EMTs, and 24 paramedics. The EMS level of service is equivalent to North America's Basic and Advanced Life Support levels.

Cardiac arrest calls initially activate ambulances that are geographically nearest to the patient. Treatment protocol for Cardiac arrest is based on the Kuwait Ministry of Health EMS protocol. EMTs are trained to perform 1 cycle of CPR at the scene as per the 2010 AHA CPR guidelines, with a 30:2 compression-to-ventilation rate, using bag-valve-mask ventilation and defibrillation. However, the protocol states that EMTs cannot remain at the scene beyond 1 CPR cycle and rhythm analysis and they must transport the patient to an emergency department while continuing to perform CPR during ambulance transport.[16]

Kuwait has a single, centralized dispatch center for all ambulance services; this is Arabic-based system and receives calls for EMS and inter-hospital transportation. For emergency calls, Kuwait follows a European emergency response system.

The average number of calls per year is approximately 90,244, including 9427 cardiac cases.[17] All calls are taken by a primary call taker. The call-taker first locates the patient and then enters a primary report of the patient's complaint into the ProQA software system (Emergency Priority Dispatch version 12.1). The call limit is 2 minutes. The patient's details are then transferred to a secondary call taker, who dispatches the nearest ambulance to the patient location, providing the ambulance crew only with the patient's primary complaint and location.

To establish the impact of DACPR on OHCA outcomes a comparison was made between 2 groups: pre-intervention period (February 21–May 31, 2017) and post-intervention period (June 1–December 31, 2017) in Hawali province.

2.2. Intervention

DACPR was implemented as a lone tool that consists of:

-

(1)

A standardized dispatch protocol that will guide interventional call takers to systematically question callers to accurately and rapidly determine whether the patient is in OHCA When a cardiac arrest patient is identified, the protocol will guide the dispatcher to give hands only-CPR instructions.

-

(2)

A training package consisting of 1-day intensive training course. The training course include: a workshop, a lecture and the completion of save heart Arizona registry and education online course.[18]

-

(3)

Quality assurance and improvement measures: audio recording, personal and organizational feedback, call taker work assessment sheet, supervisors monitoring sheet, and investigation of poor call handling.

The comprehensive DACPR was implemented in the pilot region, Hawali province, through 75 trained call takers. The trained call takers were asked to implement DACPR study protocol to OHCA calls from Hawali province. The pre-set DACPR program goal was set for OHCA recognition rate of 70% and to give CPR instructions for the recognized arrests in >75% of cases.[19] OHCA was considered recognized when a patient report form had documented cardiac arrest by a field EMS provider and was submitted to EMS audit department and matched to the call taker's intervention as follows:

-

(1)

Submitted DACPR sheet for the OHCA case.

-

(2)

Dispatch code “cardiac arrest,” “death suspicion,” or “heart” documented in dispatch electronic code.

-

(3)

Audio recording review confirms OHCA recognition or giving CPR instructions.

The DACPR was implemented live on May 31, 2017.

2.3. Participants

We prospectively identified OHCA patients that activated Kuwait EMS directly and were transported to regional hospital in Hawali province during the study period.

2.4. Eligibility criteria

Only adult (>18 years old) reporting cardiac arrest related complaints (unresponsiveness, apnoea, agonal breathing, and snoring) and documented with OHCA of cardiac etiology by field EMS providers were included. Exclusion criteria includes; unknown cause of death, rigor mortis, lividity, pronounced dead on scene, women with late pregnancies, and cardiac arrest due to; drowning, trauma, intoxication, drug overdose and electrocution.

2.5. Outcomes

Primary outcomes were defined as: OHCA recognition rate, CPR instruction rate, Bystander CPR rate, and prehospital ROSC. Secondary outcome was survival to hospital discharge.

2.6. Data source/measurement

Data elements were collected prospectively for the both groups from 3 data sources: dispatch unit electronic records, audit department archival data and Hospital medical records. Survival to hospital discharge was collected from hospital records and prehospital ROSC and Bystander CPR rate were obtained from patient record form. Dispatch code, chief complaint, patient demographics, caller demographics, hands-only CPR instruction rate were collected from Dispatch unit electronic records.

2.7. Sample size

Convenient sampling was used in this study. All eligible EMS treated OHCAs during the study period were included.

2.8. Statistical method

Using Excel and the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS version 22), a comparison for OHCA patient groups in the pilot region, pre-intervention period and post-intervention study period in terms of; bystander demographics, patient demographics, and EMS resuscitation practice and OHCA patients’ outcomes using Chi-square test to categorical variable and analysis of variance test for continuous variables.

2.9. Ethical approval

Ethical approval was granted by the Ministry of Health, State of Kuwait on 26 August 2016 (No. 448). No informed consent was sought from participants.

2.10. Consent for publication

There are no individual details included in this study.

3. Results

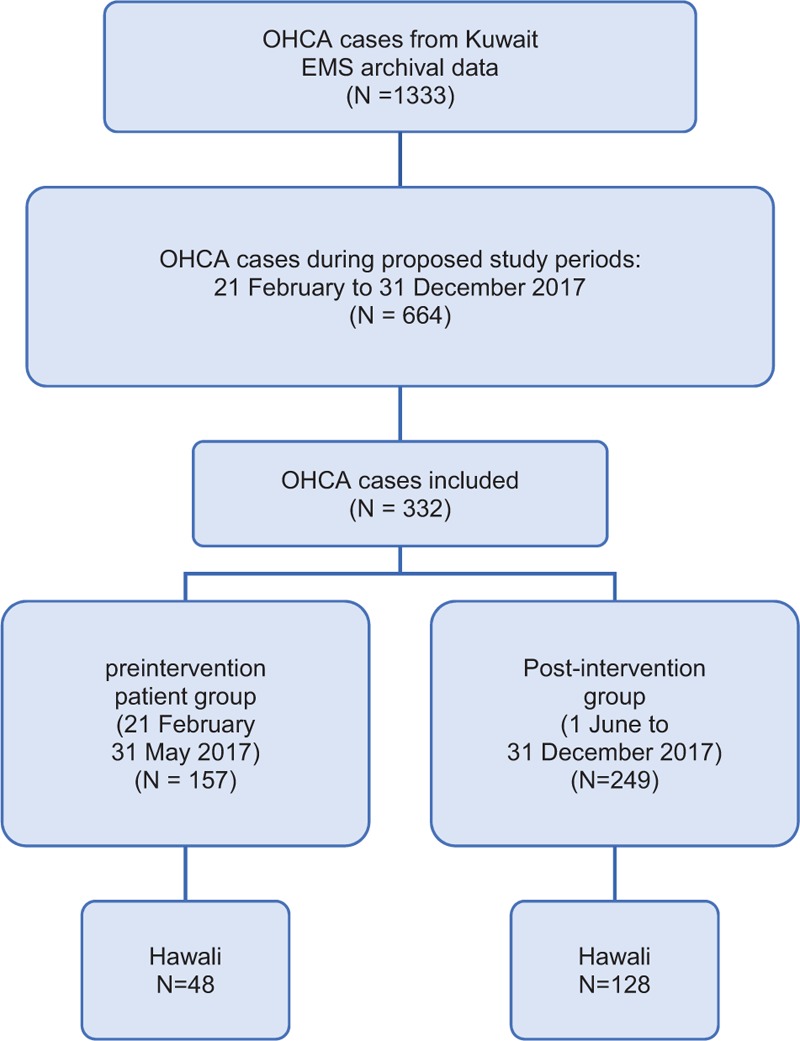

Only 176 OHCA cases met the inclusion criteria and the study periods (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

OHCA patient's selection and inclusion in the study periods; pre-intervention (February 21–May 31, 2017) and post-intervention (June 1–December 31, 2017). OHCA = out of hospital cardiac arrest.

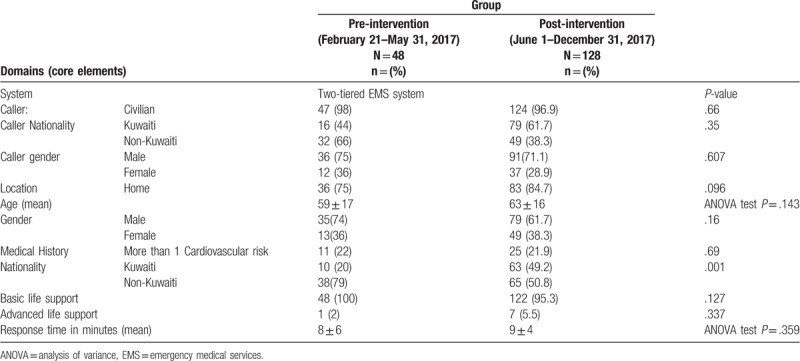

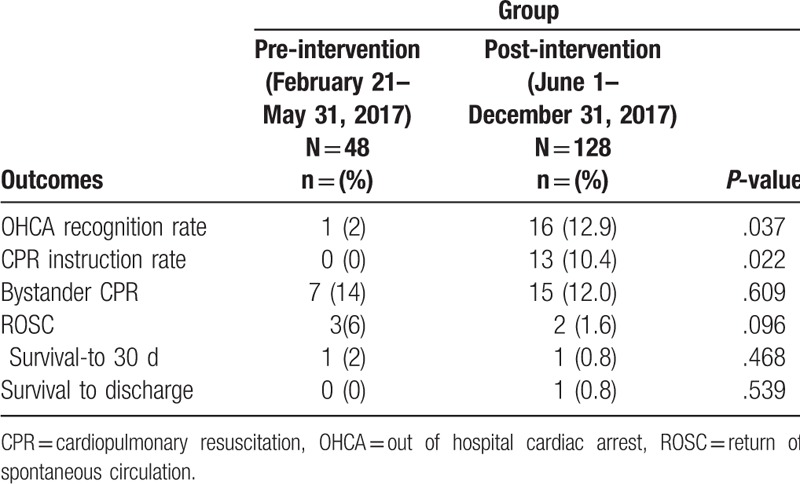

Demographic and arrest characteristics before and after the intervention (Table 1). Overall the study population of both groups was the same. OHCA patients were mostly Middle-aged males; preintervention mean age 59 ± 17 years, 74% males and 63 ± 16 years, 61.7% males. Table 2 illustrates OHCA patients’ outcomes before and after the intervention. DACPR increased OHCA recognition rate to 12.9% and CPR instruction rate 10.7% in the post-intervention group. No significant improvement was reported in Bystander CPR rate or survival to discharge.

Table 1.

Comparison between pre-intervention and post-intervention groups in pilot region, Hawali province.

Table 2.

OHCA patients’ outcomes before and after the intervention.

4. Discussion

This study examined the outcomes of DACPR implementation in Kuwait. This is the first study to report DACPR impact on OHCA outcomes on OHCA victims in the Middle East and more specifically from a pilot region of Kuwait. The enhancement of OHCA chain of survival early links, namely early OHCA recognition and early CPR is thought to have most impact on OHCA survival.[20] DACPR is a tool to improve early OHCA recognition and early CPR.[3,12] This study identified DACPR as a solo tool had positive impacts on OHCA operational outcomes; OHCA recognition and CPR-instruction rates (Table 2). Yet no significant change was recorded on Bystander CPR rate or prehospital ROSC. And although similar studies in more developed countries recorded different results,[21–24] more recently Franek et al (2019) confirmed that DACPR impact on bystander CPR rate is a long-term outcome. The author reports a significantly positive DACPR impact on Bystander CPR rates best recorded after 5 years of DACPR implementation.[25] In terms of prehospital ROSC non-significant change, the provision of audio DACPR although it increases CPR initiation, it does not ensure CPR high quality.[26] High-quality CPR is essential to Achieve ROSC.[27]

This study did not record significant improvement in prehospital ROSC and OHCA survival to hospital discharge with DACPR implementation (Table 2). These findings are in line with recently published literature.[28,29] Furthermore, the current literature reports DACPR positive impacts on OHCA survival if implemented in communities with high CPR public awareness or if applied in bundle fashion, namely public campaigns or first-responder systems.[7,30,31] This confirms that DACPR's capacity is limited to improving operational outcomes only on the short term; early-OHCA recognition and CPR instruction rates, and that it cannot act as a replacement for a fully active OHCA survival chain to improve OHCA outcomes, namely survival to hospital discharge. In the pilot region of Kuwait, DACPR raised early OHCA recognition and CPR instruction rates, but the lack of CPR public awareness, early defibrillation, and post-resuscitation care, are some potential factors resulting in low OHCA survival to hospital discharge.

Collectively, this cohort adds to the literature that DACPR is only a tool that can improve operational outcomes; early OHCA recognition and CPR instruction rates. Bystander CPR rate should be viewed as a long-term outcome of DACPR. In EMS systems that look to improve early OHCA recognition link, DACPR is an important first step in an overall comprehensive strategy to improve OHCA outcomes.

4.1. Limitation

This study has some limitations. It compared OHCA outcomes before and after DACPR implementation. Consequently, it did not have a randomized, controlled design. Thus, the possibility that the associations identified were related to other factors linked to both the intervention and outcome could not be fully eliminated. Another limitation is the small sample size, which might increase the likelihood of a Type II error. Yet the study sample size is comparable to regional studies’ sample sizes (ranging between 447 and 96 participants).[32–35] Furthermore, the present study was carried in 1 geographical location of Kuwait, and although Hawali province population is representative of Kuwait, further research on all Kuwait provinces can give more transparent results. One more limitation of this study is that DACPR was in the form of hands-only CPR only, with no instructions on defibrillation. This is because public access defibrillation is absent in Kuwait. Other limitations include; the absence of evaluation of public awareness and post-cardiac arrest care, both could influence the results of this study.

5. Conclusion

In summary, DACPR implementation had positive impacts on Kuwait EMS system operational outcomes; early OHCA recognition and CPR instruction rates in pilot region of Kuwait Expanding this initiative to other regions in Kuwait and coupling it with other OHCA system of care interventions are needed to improve OHCA survival rates.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge and thank Mr. Mohmmad Al Sharah and Mr. Soud Al Asfoor from Kuwait EMS Dispatch and their teams for their enormous help and support rendered in the course of gathering the necessary data for the study.

Author contributions

Data curation: Dalal Al Hasan, Salim Al Mahmid, Haitham Ahmad, Mohmmad Ameen.

Formal analysis: Dalal Al Hasan.

Investigation: Dalal Al Hasan.

Methodology: Dalal Al Hasan, Jonathan Drennan, Eloise Monger.

Project administration: Dalal Al Hasan.

Validation: Dalal Al Hasan.

Visualization: Dalal Al Hasan.

Writing – original draft: Dalal Al Hasan, Mazen El Sayed.

Writing – review and editing: Mazen El Sayed.

Footnotes

Abbreviations: AHA = American Heart Association, CPR = cardiopulmonary resuscitation, DACPR = dispatcher assisted cardiopulmonary resuscitation, EMS = emergency medical services, OHCA = out of hospital cardiac arrest, ROSC = return of spontaneous circulation.

How to cite this article: Hasan DA, Drennan J, Monger E, Mahmid SA, Ahmad H, Ameen M, Sayed ME. Dispatcher assisted cardiopulmonary resuscitation implementation in Kuwait: A before and after study examining the impact on outcomes of out of hospital cardiac arrest victims. Medicine. 2019;98:44(e17752).

The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the paper.

The database generated during the present study are summarized in the technical appendix and available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

The authors have no funding and conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- [1].Sasson C, Rogers M, Dahl, et al. Predictors of survival from out-of-hospital cardiac arrest: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes 2010;3:63–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Fischera MS Kamp##J. Comparing emergency medical service systems—a project of the European Emergency Data (EED) Project. Resuscitation 2010;82:285–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].McCarthy J, Carr B, Sasson C, et al. AHA scientific statement; out-of-hospital cardiac arrest resuscitation systems of care: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2018;137:1–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Global Resuscitation Alliance. Improving Survival of Out-of-Hospital Cardiac Arrest; Acting on the Call. 2018 Update from the Global Resuscitation Alliance. Including 27 Case Reports. United States. 2018. Available at: https://www.cercp.org/images/stories/recursos/articulos_docs_interes/doc_GRA_Acting_on_the_call_1.2018.pdf [Accessed on September 20, 2018] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Arizona Department of Health Services. Save Hearts in Arizona Registry and Education. Arizona; Save Hearts in Arizona Registry and Education Training Resources. 2017. Available at: https://www.azdhs.gov/preparedness/emergency-medical-services-trauma-system/save-hearts-az-registry-education/index.php, [Accessed on March 1, 2018] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Boyce L, Vlietvlieland T, Bosch J, et al. High survival rate of 43% in out-of-hospital cardiac arrest patients in an optimised chain of survival. Netherland Heart J 2015;23:20–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Bobrow B, Spaite D, Vadeboncoeur T, et al. Implementation of a regional telephone cardiopulmonary resuscitation program and outcomes after out-of-hospital cardiac arrest. J Am Med Assoc Cardiol 2016;1:294–302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Public Health Seattle and King County. Citizen Cardio Pulmonary Resuscitation (CPR). Public Health Seattle and King county, King County Medic One, 2018. Available at: https://www.kingcounty.gov/depts/health/emergency-medical-services/medic-one/citizen-cpr.aspx Accessed September 20, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- [9].Seattle & King County Emergency Medical Services. 2015 Annual Report to the King County Council’ Seattle & King County Emergency Medical Services. King County Reports and Publications, 2015. Available at: https://www.skagitcounty.net/EmergencyMedicalServices/Documents/Advisory/Documents/06-27-16%202015%20King%20County%20EMS%20Annual%20Report.pdf Accessed September 20, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- [10].King County Emergency Medical Services. Emergency Medical Dispatch (EMD) Program Basic Criteria-based Dispatch Training, Continuing Education Instructor Development Course. King County; Emergency Medical Dispatch, 2018. Available at: https://www.kingcounty.gov/depts/health/emergency-medical-services/emd.aspx Accessed September 20, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- [11].Resuscitation Academy. The Road to Recognition and Resuscitation; The Role of Telecommunicators and Telephone CPR Quality Improvement in Cardiac Arrest Survival. Resuscitation Academy 2017. [Google Scholar]

- [12].American Heart association, American Heart Association. American Heart Association Recommends Standards to Improve Dispatcher-Assisted CPR. 2016;Available at: https://newsroom.heart.org/news/american-heart-association-recommends-standards-to-improve-dispatcher-assisted-cpr [Accessed on March 1, 2018]. [Google Scholar]

- [13].General Population Census. Kuwait Population. Kuwait: General Population Census Office; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- [14].Kuwait Central Statistical Bureau. Population Statistics. Kuwait: Kuwait Central Statistical Bureau Office; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- [15].The Public Authority of Civil Information. Distribution of the Population by Gender and Nationality in each Governorate. Kuwait: Statistics Services System; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- [16].Kuwait Emergency Medical Services Training Department. Cardiac Arrest Refreshment Program; Instructor in Field Kuwait. Kuwait: Kuwait Emergency Medical Services; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- [17].Kuwait Operation Unit, Kuwait Emergency Medical Services. Operation Department Annual Report. 2013. [Google Scholar]

- [18].Arizona Department of Health Services. Save Hearts in Arizona Registry and Education. Arizona; Save Hearts in Arizona Registry and Education Training Resources. 2017. Available at: https://www.azdhs.gov/preparedness/emergency-medical-services-trauma-system/save-hearts-az-registry-education/index.php [Accessed on March 1, 2018] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Deakin C, England S, Diffey D. Ambulance telephone triage using ‘NHS pathways’ to identify adult cardiac arrest. Heart BMJ 2017;103:738–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Deakin C. The chain of survival: not all links are equal. Resuscitation 2018;126:80–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Harjnato SN, MX N, Hoa Y, et al. A before-after interventional trial of dispatcher-assisted cardio-pulmonary resuscitation for out-of-hospital cardiac arrests in Singapore. Resuscitation 2016;102:85–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Huang C, Fan H, Chein C, et al. Validation of a dispatch protocol with continuous quality control for cardiac arrest: a before-and-after study at a city fire department-based dispatch center. J Emerg Med 2017;53:697–707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Ro Y, Shin S, Lee Y, et al. Effect of dispatcher-assisted cardiopulmonary resuscitation program and location of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest on survival and neurologic outcome. Ann Emerg Med 2017;69:52–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Song K, Shin S, Park C, et al. Dispatcher-assisted bystander cardiopulmonary resuscitation in a metropolitan city: a before-after population-based study. Resuscitation 2014;85:34–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Franěk O, Pekara J, Sukupova P, et al. 16 long term effects of dispatcher- assisted CPR – did we touch the ceiling? BMJ Open 2019;9:A1–6. [Google Scholar]

- [26].Asai H, FuKuShima H, Bolstad F, et al. Quality of dispatcher-assisted cardiopulmonary resuscitation by lay rescuers following standard protocol in Japan; observational simulation study. Acute Med Surg 2018;5:133–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].American Heart Association, Doshi A, Pinchalk M, Roberts R. High quality CPR demonstration and analysis. 2017;Available at: https://www.heart.org/-/media/data-import/downloadables/high-quality-cpr-ucm_497293.pdf?la=en&hash=0BBC2BC5991D6F531A3F76E03D0CEABA4AC34395. [Accessed on Sept 20, 2018]. [Google Scholar]

- [28].Hardeland C, Skare C, Kramer-Johnson J, et al. Targeted simulation and education to improve cardiac arrest recognition and telephone assisted CPR in an emergency medical communication centre. Resuscitation 2017;114:21–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Shah M, Bartram C, Irwin K, et al. Evaluating dispatch-assisted CPR using the CARES registry. Prehospital Emerg Care 2018;22:222–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Viereck S, Moller T, Ersball A, et al. Recognising out-of-hospital cardiac arrest during emergency calls increases bystander cardiopulmonary resuscitation and survival. Resuscitation 2017;115:141–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Tanaka Y, Taniguchi J, Wato Y, et al. The continuous quality improvement project for telephone- assisted instruction of cardiopulmonary resuscitation increased the incidence of bystander CPR and improved the outcomes of out-of-hospital cardiac arrests. Resuscitation 2012;83:1235–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Wu Z, Panczyk M, Spaite D, et al. Telephone cardiopulmonary resuscitation is independently associated with improved survival and improved functional outcome after out-of-hospital cardiac arrest. Resuscitation 2018;122:135–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Batt A, Alhajeri A, Cummins F. A profile of out-of-hospital cardiac arrests in Northern Emirates, United Arab Emirate. Saudi Med J 2016;37:1206–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Bin Salleeh H, Gabralla K, LEggio W, et al. Out-of-hospital adult cardiac arrests in a university hospital in central Saudi Arabia. Saudi Med J 2015;36:1071–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Irfan F, Bhtta Z, Castren M, et al. Epidemiology and outcomes of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest in Qatar: a nationwide observational study. Int J Cardiol 2016;223:1007–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]