Abstract

During prolonged exposure to antigens, such as chronic viral infections, sustained TCR signaling can result in T cell exhaustion mediated in part by expression of Programmed cell death-1 (PD-1) encoded by the Pdcd1 gene. Here, dynamic changes in histone H3K4 modifications at the Pdcd1 locus during ex vivo and in vivo activation of CD8 T cells, suggested a potential role for the histone H3 lysine 4 demethylase LSD1 in regulating PD-1 expression. CD8 T cells lacking LSD1 expressed higher levels of Pdcd1 mRNA following ex vivo stimulation, as well as increased surface levels of PD-1 during acute but not chronic infection with lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus (LCMV). Blimp-1, a known repressor of PD-1, recruited LSD1 to the Pdcd1 gene during acute but not chronic LCMV infection. Loss of DNA methylation at Pdcd1’s promoter proximal regulatory regions is highly correlated with its expression. However, following acute LCMV infection where PD-1 expression levels return to near base line, LSD1-deficient CD8 T cells failed to remethylate the Pdcd1 locus to the levels of wild-type cells. Finally, in a murine melanoma model, the frequency of PD-1 expressing tumor infiltrating LSD1-deficient CD8 T cells was greater than in wild type. Thus, LSD1 is recruited to the Pdcd1 locus by Blimp-1, downregulates PD-1 expression by facilitating the removal of activating histone marks, and is important for remethylation of the locus. Together, these data provide insight into the complex regulatory mechanisms governing T cell immunity and the regulation of a critical T cell checkpoint gene.

Introduction

Programmed cell death-1 (PD-1) is an immunoinhibitory protein that is expressed on lymphocytes following the engagement of their antigen specific receptor (1). During the course of an acute infection, PD-1 expression is transient on the surface of CD8 T cells, peaking during the height of an infection and returning to near baseline levels in the resulting memory T cell pool (1–5). During chronic exposure to antigen, such as that from a chronic viral infection or in certain cancers, PD-1 expression is sustained at high levels and a state of T cell exhaustion is induced that is characterized by severe curtailment in effector functions, including the ability to proliferate, produce cytokines, and carry out cytotoxic responses (6). T cell exhaustion is in part mediated by signaling through PD-1’s intracellular tyrosine immunoinhibitory domains following PD-1’s surface engagement with its ligands PD-L1 or PD-L2 on target cells (1, 7–9). Although antibody blockade of PD-1/PD-L1 interactions can temporarily reinvigorate immune function from the exhausted state (1), PD-1 remains stably expressed on T cells during a chronic infection (10), and is expressed even upon removal of the cell from a chronic stimulatory environment (11). The stability of PD-1 expression and inhibition of effector functions across generations of cell division suggests that an epigenetic program stably regulates the transcriptional state of the Pdcd1 locus.

PD-1 is encoded by the Pdcd1 gene. In CD8 T cells, Pdcd1 is regulated by the direct actions of transcription factors and epigenetic mechanisms (2, 10, 12). Upon T cell receptor engagement, Pdcd1 is directly activated by a combination of transcription factors (NFATc1 and AP-1) that bind to a series of promoter proximal elements termed Conserved Regions (CR)-B and CR-C (12, 13), respectively. NFAT also binds to sites at −3.7 and +17.1 kb with respect to the transcription start site (14). Additional transcription factors appear to sustain Pdcd1 during chronic infection and include the binding of NUR77 and FOXN1 to sites located at −23 kb and CR-C, respectively (15–18). Cytokine stimulation that results in STAT3 and STAT4 activation can further induce or sustain Pdcd1 expression in mouse CD8 T cells by binding to the distal −3.7 and +17.1 sites (14). Following the cessation of the TCR signaling (e.g., via antigen/viral clearance), Pdcd1 is silenced through the binding of B lymphocyte induced maturation protein-1 (Blimp-1) to a region between CR-C and CR-B (19). Blimp-1 binding results in the eviction of NFATc1 from CR-C (19). In addition to these mechanisms, epigenetic regulation through DNA methylation occurs across CR-C and near CR-B in CD8 T cells in both mice and humans (2, 10). In naïve CD8 T cells, CpGs in the above DNA regions are consistently methylated. Upon CD8 T cell activation, the methylation is lost in a time course that parallels Pdcd1 expression. In an acute infection setting, the locus is remethylated as the infection is cleared and PD-1 levels return to the baseline as mentioned above. By contrast, during chronic infection, DNA methylation is permanently lost and is not regained (2, 10).

In a similar manner, the accumulation and removal of activating and repressing histone modifications correlate completely with Pdcd1 expression in mouse CD 8 T cells. For example, both H3K27ac and H3K9ac activation modifications at CR-B and CR-C correlate with Pdcd1 expression when driven by ex vivo TCR stimulation (19, 20), and H3K4me1 is enriched when the above stimulation is coupled with IL-6 and IL-12 (STAT3/STAT4) treatment (14). However, as expression wanes during ex vivo stimulation, the repressive modifications H3K9me3, H3K27me3, and H4K20me3 appear at CR-B and CR-C (19). Using the EL4 T cell line, exogenous expression of the transcriptional repressor Blimp-1 induced the appearance of all three of these repressive modifications at the Pdcd1 locus and subsequently silenced PD-1 expression (19). Surprisingly, Blimp-1 is also expressed during a chronic infection in exhausted CD8 T cells where PD-1 levels are at their highest, yet fails to repress PD-1 (21). The molecular mechanism for how Blimp-1 could function to repress Pdcd1 exclusively following acute inflammation is not fully clear.

As a repressor, Blimp-1 is known to recruit additional transcriptional repressors that result in silencing the local chromatin environment (22–24). Along with histone deacetylases HDAC1 and HDAC2 and the histone methyltransferase G9a, Blimp-1 can recruit the lysine-specific demethylase 1a (LSD1) encoded by Kdm1a (23–25). LSD1 catalyzes the removal of mono and dimethylation modifications of H3K4 that are associated with transcriptional activation (26–28), thereby facilitating an epigenetic state of gene silencing. Given the ability of Blimp-1 to repress genes through recruitment of histone modifiers such as LSD1, we set out to test the hypothesis that LSD1 contributes to the regulation of Pdcd1 in a Blimp-1-dependent manner. Indeed, we found that Blimp-1 was necessary to recruit LSD1 to the Pdcd1 locus, and that when bound, LSD1 actively downregulates PD-1 transcription and expression. Furthermore, we found that Blimp-1 was bound to the Pdcd1 locus in both acute and chronic settings; however, LSD1 was only recruited following an acute stimulation, correlating with removal of proximal H3K4me1/me2 modifications and appearance of a repressive epigenetic profile concurrent with Pdcd1 silencing and DNA remethylation of the locus following acute viral infection. We also found that greater frequency of PD-1 expressing tumor infiltrating CD8 T cells in LSD1-deficient compared to LSD1-sufficient mice in a melanoma model. Thus, LSD1 and Blimp1 together are responsible for resetting the epigenetic programming of the Pdcd1 locus to a resting state.

Material and Methods

Animals

C57BL/6J mice were obtained from Jackson laboratories. Kdm1afl/fl mice (29) (provided by D. Katz at Emory University) were crossed to mice containing a Granzyme B promoter-driven Cre recombinase (B6;FVB-Tg(GMB-cre)1Jcb) (provided by J. Jacob at Emory University) (30), and subsequently back-crossed to the C57BL/6 mouse line for 4–5 generations. Prdm1fl/fl mice were provided by K. Calame (Columbia University) and similarly crossed to Granzyme B-cre mice (19). Equal numbers of male and female mice were used in all experiments. The numbers of animals used in each experiment are provided in the figure legends. All experiments were performed in accordance with approved protocols by the Emory University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Virus Infection

Viral stocks of lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus (LCMV) strains Armstrong and Clone-13 were generated as previously described (31) and kindly provided by Dr. Rafi Ahmed (Emory University). Mice were infected with 2×105 pfu of LCMV Armstrong intraperitoneally or with 2×106 pfu LCMV Clone-13 intravenously as described (32). Viral titers were determined by plaque assay using Vero cells (ATCC CCL-81) as previously described (32, 33)

Cell isolation and ex vivo cell activation

For analysis or ex vivo cell culture, CD8 T cells were isolated from single-cell splenocyte suspensions using the Miltenyi CD8a+ T cell isolation kit (Miltenyi Biotec, Inc. Cat.130-104-075) according the manufacture’s protocol. Where indicated, LCMV tetramer specific cells (see below) were further purified by FACS on a BD FACSAria II (Emory SOM Flow Cytometry Core) following infection as indicated and biochemically/molecularly analyzed immediately. For some experiments, isolated cells were cultured ex vivo in RPMI supplemented with 5% FBS, 5% bovine calf serum, 4.5 g/l glucose, 1.0 mM sodium pyruvate, 10 mM HEPES and 100 U/ml Penicillin/streptomycin. For ex vivo activation, isolated CD8 T cells were stimulated using Dynabeads Mouse T-activator CD3/CD28 kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific (Gibco) Cat. 11453D) according to the manufacture’s protocol at a ratio 2:1 beads/cell for the indicated time (24–96 hours).

Flow cytometry

Cells were stained for flow cytometry in FACS buffer (PBS, 1% BSA, 1 mM EDTA) for 30 m, and subsequently fixed using 1% paraformaldehyde for 30 m. Events were collected on a BD LSR II and analyzed using FloJo 9 software. Antibodies used to stain cells included: CD4 PerCP-Cy5.5 (clone RM4.5); CD8 FITC (clone 53-6.7); CD44 APC-Cy7 (clone IM7); CD62L Alexa Fluor 700 (clone MEL-14); CD69 PE-Cy7 (Clone H1.2F3); CD127 BV510 (Clone SB/199); PD-1 PE (clone RMP1-30). Biotinylated H-2Db MHC tetramers specific for LCMV peptides for gp33 var C41M (KAVYNFATM), gp276 (SGVENPGGYCL), and np396 (FQPQNGQFI) were obtained from the NIH Tetramer Core facility at Emory University and subsequently tetramerized to streptavidin-APC (Prozyme) following their protocols (tetramers.yerkes.emory.edu).

Quantitative Real-time PCR

RNA was isolated from at least three independent preparations of cells using the RNAeasy kit (Qiagen, Inc.), and cDNA was prepared from RNA libraries using SuperScript II reverse transcriptase (Life Technologies Co). RT-PCR was used to quantitate mRNA levels in technical duplicates, and values were normalized using 18s ribosomal RNA as previously described (34).

Chromatin Immunoprecipitation

Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assays were performed as previously described (19, 35). Briefly, purified cell populations were crosslinked for 10 minutes in 1% formaldehyde, and subsequently lysed in cell lysis buffer (5mM PIPES pH 8.0, 85 mM KCl, 0.5% NP-40). Chromatin was extracted using nuclei lysis buffer (50 mM TRIS pH 8.1, 10 mM EDTA, 1% SDS) and sonicated to an average length of 400–600 bp. Chromatin (5 μg) was used for immunoprecipitation reactions on Protein A beads with 0.5 μg of polyclonal antibodies for H3K4me1 (Millipore Sigma Cat. 07-436), H3K4me2 (Millipore Sigma Cat. 07-030), H3K4me3 (Millipore Sigma Cat. 07-473), H3K27ac (Millipore Sigma. Cat. 07-360), IgG (Millipore Sigma, Cat. 12-370), Blimp-1 (Rockland Cat. 600-401-B52) and LSD1 (Santa Cruz Cat. SC-271720). Precipitates were quantitated by quantitative PCR and calculated as a percent of input. (Supplemental Table 1).

DNA methylation analysis

The DNA methylation content of the CR-B associated region was determined by clonal bisulfite sequencing as previously described (2). Briefly, genomic DNA purified from CD8 T cells and bisulfite converted using the EpiTect Bisulfite Kit as per the manufacturer’s instructions (Qiagen, Inc.). Bisulfite-converted DNA was PCR amplified and cloned with the TOPO TA cloning kit (Life Technologies). Clones were isolated and the plasmid DNA regions were sequenced and changes in CpG DNA methylation were determined. Data were aligned in silico using the R / Bioconductor Biostrings package and custom scripts as previously described (36). A Fisher exact test was used to determine significance.

Protein purification and Western blot

To quantify the levels of LSD1 protein in CD8 T cells from naïve and LCMV infected mice, CD8 T cells were isolated from single-cell splenocyte suspensions using the Miltenyi CD8a+ T cell isolation kit (Miltenyi Biotec, Inc. Cat.130-104-075) according the manufacture’s protocol. Post isolation, cells were washed in PBS and pelleted by centrifugation at 3000 RPM for 5 minutes at 4° C. Cells were then lysed in 1X volume of RIPA buffer (20% glycerol, 50mM Tris (pH 8.0), 150mM NaCl, 0.1% SDS, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 1% NP-40 and 1mM PMSF) for 20 minutes at 4° C. The cells were then pelleted at 15,000 RPM for 10 minutes at 4° C and the resulting supernatant representing the protein lysate was stored at −80° C.

For western blotting, 60μg of CD8 T cell lysate from naïve, day 8 Clone-13 infected and day 8 Armstrong infected C57BL/6 mice were resolved on a 9% SDS-PAGE gel and then transferred to a PVDF membrane. The membrane was cut in half and incubated overnight at 4° C in TBS-T (150 mM NaCl, 2mM Tris pH 7.4, 2mM KCl and 0.1% Tween-20) containing 5% Non-fat dry milk with the primary antibody. The primary antibodies used were LSD1 (B-9X) (1:75 dilution) (Santa Cruz Biotechnology Cat. sc-271720X) and β-actin (AC-15) (1:3000 dilution) (Santa Cruz Biotechnology Cat. sc-69879). Membranes were then incubated in TBS-T containing 5% non-fat dry milk with an HRP-conjugated sheep anti-mouse secondary antibody (1:3300 dilution) (Sigma-Aldrich Cat. A6782). To develop, membranes were treated with ECL (GE Cat. RPN2106) and visualized with the Chemi Hi Resolution setting on a ChemiDoc MP imagining system (Bio-Rad Laboratories).

Intracellular cytokine staining

Single cell splenocyte suspensions were prepared from the spleens of day 8 LCMV Armstrong infected LcKO and WT control mice. 2 × 106 splenocytes were incubated for 5 hours at 37° C in the presence of phorbol myristate acetate (PMA), Ionomycin and Brefeldin A (BFA) (5μg/ml). After stimulation, cells were stained for surface markers for flow cytometry. The cells were then fixed and permeabilized using the Cytofix/Cytoperm kit (BD Bioscience Cat. 555028) according the manufacturer’s protocol. The antibodies used for intracellular cytokine staining were: IL-2 PE (clone JES6-5H4), TNFα FITC (clone MP6-XT22) and IFNγ APC (clone XMG1.2).

Results

Pdcd1 histone modifications differ between acute and chronic infection

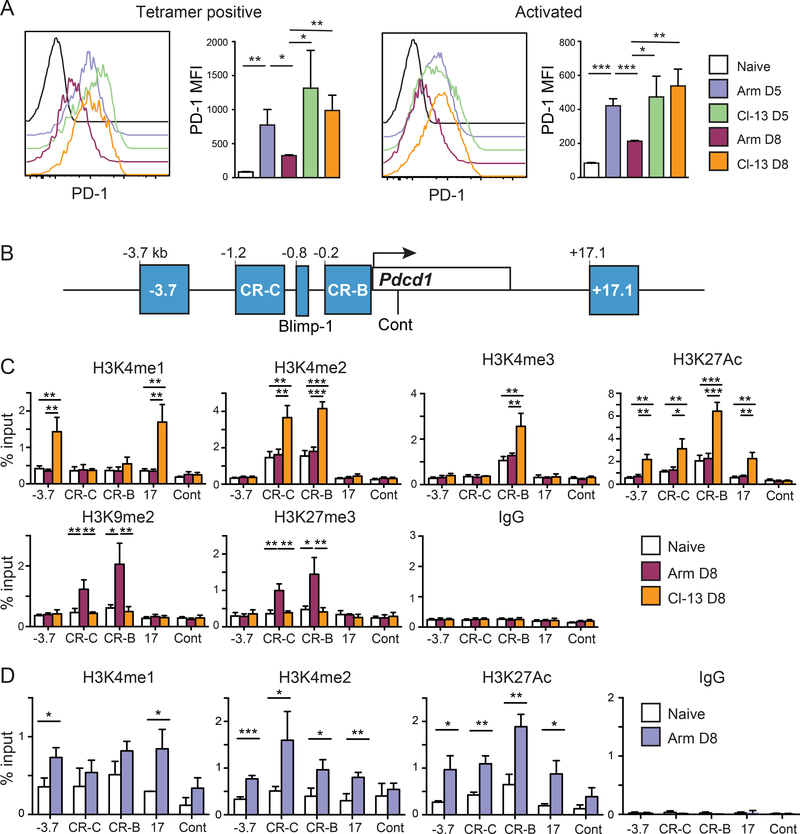

As previously shown (1, 2), infection with LCMV Armstrong induces an acute infection that results in CD8 T cells expressing high surface levels of PD-1 on day 5 post-infection, but this ultimately decreases to near naïve T cell levels 8 days following infection when virus is no longer detectable (Fig.1A). Conversely, infection with the chronic LCMV strain Clone-13 results in PD-1 surface (Fig. 1A) and mRNA levels (2) that remain elevated during the course of the infection. To gain additional insight into epigenetic mechanisms that may be driving the above changes and differences in PD-1 expression between acute and chronic infections, we examined activating and repressive histone modifications at key regulatory elements (37) across the Pdcd1 locus (Fig. 1B). At day 8, splenic CD8 T cells were isolated and analyzed by chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP). We observed that the −3.7 and 17.1 regions were enriched for the active H3K4 mono-methylated histone mark (H3K4me1) in antigen specific CD8 T cells of chronically infected mice compared to both acutely infected and naïve mice (Fig. 1C). Another active histone mark, H3K4me2, was also enriched in chronically infected mice at both the CR-B and CR-C regulatory regions of the Pdcd1 locus. H3K27ac enrichment, a mark associated with active promoters/enhancer regions (38) was higher at all sites in CD8 T cells from Clone-13 infected mice compared to those from Armstrong infected or naïve mice. ChIP for the repressive histone marks H3K9me2 and H3K27me3 were enriched at both CR-B and CR-C but only in Armstrong infected mice (Fig.1C). Taken together, these data demonstrate that at day 8 post infection, CD8 T cells from chronically infected mice have active histone marks in the Pdcd1 locus whereas the acutely infected mice have an enrichment for repressive marks. Moreover, these histone modifications correspond with PD-1 expression on CD8 T cells from chronically and acutely infected mice (Fig. 1A, C).

Figure 1. Activating histone marks are dynamically regulated and correlate with Pdcd1 expression.

C57Bl/6 mice were infected with either LCMV Armstrong (Arm) or Clone-13 (Cl-13) for 5 or 8 days as indicated. (A) Representative flow cytometry plots showing the surface PD-1 levels on CD8 T cells. Plots were gated on CD8 T cells and show combined LCMV gp33, gp276 and np396 tetramer positive cells (day 8) or total activated CD8 T cells defined as CD44hi and CD62Llow (day 5). Bar graphs represent combined averages of 3 mice. (B) Schematic highlighting regulatory elements of the Pdcd1 locus where ChIP assays were performed. (C) ChIP assay for both activating and repressive histone marks on CD8 T cells isolated from day 8 Armstrong or Clone-13 infected mice. (D) ChIP on activated CD44hi CD62Llow isolated from day 5 infected Armstrong mice and naïve uninfected mice for activating histone marks. Data are representative of two independent experiments containing 3 to 4 mice per group. A two tailed Student’s t tests was used to determine significance in the experiments from A and D. For part C, significance was determined by analysis of variance with Tukey’s post-hoc correction. *, P < 0.05 **, P < 0.01 ***, P < 0.001.

The above data raise the question as to whether active histone marks examined appear at an earlier timepoint during an in vivo response to an Armstrong infection that would correlate with the increased surface expression. To test this, cells were isolated at day 5 following LCMV Armstrong infection, a time point in which PD-1 expression was high (Fig. 1A) and enough activated CD8 T cells (CD44hi CD62Llow) could be isolated for ChIP. In these experiments, H3K4me2 and H3K27ac were enriched over control naïve CD8 T cells at all four key regulatory elements; whereas H3K4me1 was only significantly enriched at −3.7 and 17.1 (Fig 1D). Thus, active histone modifications at key regulatory elements are associated with PD-1 expression and during the course of an acute infection, these marks are replaced by repressive histone modifications as expression is silenced. This raises the question of how the dynamics of histone modifications at the Pdcd1 locus are regulated.

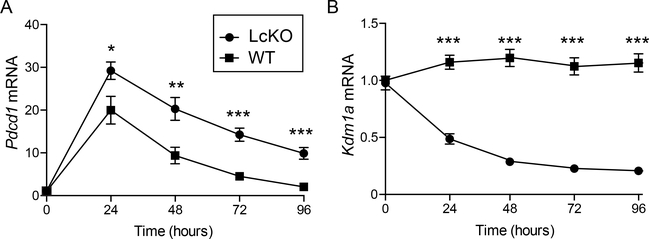

LSD1 represses PD-1 following ex vivo stimulation

LSD1 encoded by Kdm1a is responsible for catalyzing the removal of both H3K4me2 and H3K4me1 marks to an unmethylated state, a process that has been dubbed enhancer decommissioning as it can lead to gene silencing (26, 27). To test the hypothesis that LSD1 is actively recruited and responsible for down regulation of Pdcd1 gene expression following an acute infection, we crossed an Kdm1afl/fl mouse (29) with the CreGranzB mouse (30). The Kdm1afl/fl allele allows for Cre-mediated deletion of LSD1’s amine oxidase catalytic domain (29). The CreGranzB allele is induced in CD8 T cells upon T cell activation (19, 30) leading to a conditional deletion of LSD1 in activated CD8 T cells. Using the Kdm1afl/flCreGranzB mouse (designated LcKO henceforth), we first determined whether an LSD1 deficiency could alter the kinetics of Pdcd1 expression in an ex vivo activation system. Here splenic CD8 T cells from littermate Kdm1afl/flCre− controls (termed WT) and LcKO mice were purified and stimulated in culture using αCD3/CD28 beads over a 4-day period and expression of Pdcd1 mRNA was measured by qRT-PCR at daily intervals. CD8 T cells from LcKO animals displayed significantly higher levels of Pdcd1 mRNA compared to WT littermate controls at 24 hours, the peak of Pdcd1 expression by this method of stimulation (Fig. 2A). Moreover, whereas WT Pdcd1 mRNA levels decayed over the 96 h time course, Pdcd1 mRNA levels remained significantly higher in the LcKO CD8 T cells at all time points after initial stimulation. Additionally, qRT-PCR for Kdm1a mRNA levels showed that the LcKO animals had a significant reduction in LSD1 mRNA compared to WT controls, confirming efficient deletion of the floxed Kdm1a alleles following stimulation (Fig. 2B). The lag phase prior to complete deletion of Kdm1a may account for the slight, although significantly less than in WT, decrease in Pdcd1 expression after peak. While PD-1 levels were higher at all time points in CD8 T cells from LcKO mice, the rate at which PD-1 decreased was similar between LcKO at WT cells. This could be due to additional mechanisms that have been shown to downregulate PD-1 expression such as the loss of the PD-1 activator, NFATc1, binding to its cognate site in the Pdcd1 locus or the binding of the PD-1 repressor, Tbet (18, 19). However, despite the similar rate of PD-1 downregulation, these results demonstrate that LSD1 acts as a negative regulator of PD-1 expression in CD8 T cells following ex vivo stimulation.

Figure 2. LSD1 acts as a repressor of Pdcd1 expression in ex vivo stimulated CD8 T cells.

CD8 T cells were isolated from Kdm1afl/fCre− (WT) and Kdm1afl/flCreGranzB (LcKO) by magnetic separation and then stimulated for up to 96 hours using αCD3/CD28 beads at a 2:1 bead:cell ratio. Every 24 hours, cells were collected for RNA and analyzed by qRT-PCR. (A) qRT-PCR showing Pdcd1 expression. (B) qRT-PCR showing Kdm1a (LSD1) expression and that it was efficiently deleted from LcKO CD8 T cells. Data are representative of groups of 3 to 4 mice from two independent experiments. A two tailed Student’s t test was used to determine significance at each time point. *, P < 0.05 **, P < 0.01 ***, P < 0.001.

LSD1 represses PD-1 following acute viral infection

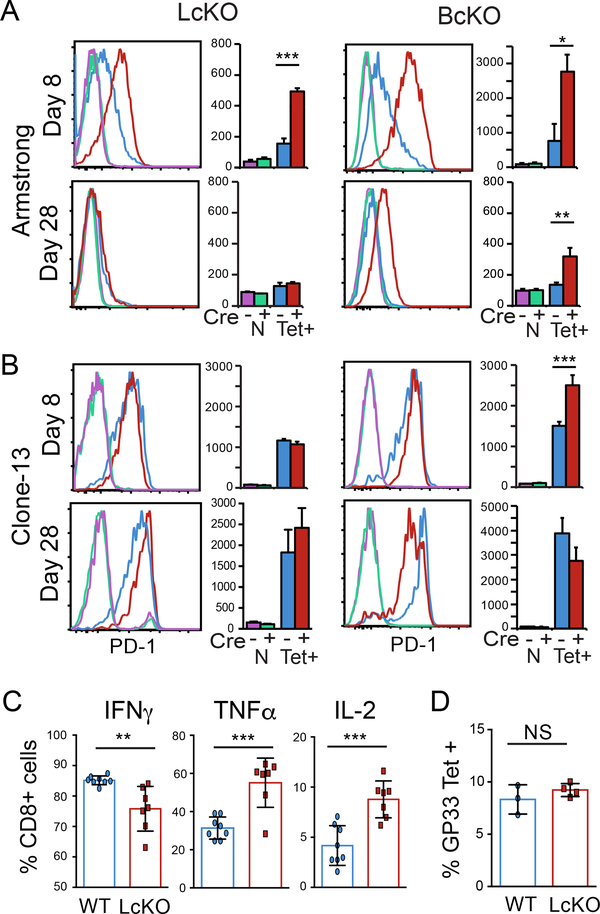

To test if PD-1 expression is modulated by LSD1 during an acute viral infection, WT and LcKO mice were infected with LCMV Armstrong and PD-1 expression on LCMV antigen-specific CD8 T cells was monitored by flow cytometry. At day 8 post infection, when viral loads have been cleared and WT mice have downregulated surface PD-1 expression on LCMV antigen-specific CD8 T cells (Fig. 3A, blue), LcKO CD8 T cells retained high levels of PD-1 expression (Fig. 3A red). Previously (19), we found that conditional deletion of Blimp-1, a transcriptional repressor that has been suggested to interact with LSD1 (23), produced a similar phenotype to LcKO mice, which is reconfirmed here (Fig. 3A) using CreGranzBPrdm1fl/fl (BcKO) mice. The similar phenotype suggests that these enzymes may operate along the same pathway, in line with the hypothesis that Blimp-1 recruits LSD1 in order to mediate Pdcd1 repression. By 28 days post infection with Armstrong, LSD1 knockout antigen-specific CD8 T cells no longer showed an increase in PD-1 expression, unlike cells from Blimp-1 knockout mice, which still showed some level of PD-1 expression over their littermate (Cre−) controls (Fig. 3A). This suggests that while LSD1 is an important determinant in the pathway responsible for decreasing PD-1 expression it does not account for the entire level of PD-1 repression mediated by Blimp-1.

Figure 3. LSD1 represses PD1 during acute viral infection.

LcKO, BcKO and WT control mice were infected with LCMV Armstrong (A) or Clone-13 (B) for 8 or 28 days. Cells were isolated and subject to flow cytometry to assay surface PD-1 expression. Plots show naïve (N) CD8 T cells gated as CD8+CD44low CD62Lhi; and LCMV-specific cells gated as CD8+, CD44hi and gp33 tetramer positive (Tet+). (C) LcKO and WT control mice were infected with LCMV Armstrong for 8 days. Splenocytes were collected and stimulated in presences of PMA, Ionomycin and BFA for 5 hours at 37° C. Cells were then stained for intracellular cytokines IFNγ, TNFα and IL-2. Cells are gated on CD8+ and the respective cytokine +. (D) LcKO ant WT mice were infected with LCMV Armstrong for 8 days and then assessed for the frequency of GP33 tetramer specific CD8 T cells. Cells are gated on CD8+, CD44+ and GP33 tetramer +. Data are representative of groups of 3 to 4 mice from two independent experiments. A two tailed Student’s t test was used to determine the significance at each time point. *, P < 0.05 **, P < 0.01 ***, P < 0.001.

To determine if LSD1 affected PD-1 expression during a chronic LCMV infection, antigen specific cells were isolated from WT and LcKO mice following LCMV Clone-13 infection and analyzed by flow cytometry. At day 8, WT and LcKO CD8 T cells expressed moderate levels of PD-1 (Fig. 3B), while at day 28 post infection, no difference in MFIs were observed between WT and LcKO (Fig. 3, bottom). During chronic infection, BcKO CD8 T cells at day 8 had an overall mean fluorescent intensity that was higher, but the histogram patterns overlap with WT cells to a significant degree. Thus, at this early stage, Blimp-1 may not be contributing to Pdcd1 regulation. At the chronic infection time point (day 28), BcKO CD8 T cells expressed slightly lower levels of PD-1, which was in agreement with previous reports (21). The differential roles performed by Blimp-1 and LSD1 at day 28 of a chronic infection may indicate that their activities may be dissociated under these conditions and at these late time points.

Since LcKO cells have increased levels of PD-1 at day 8 post LCMV Armstrong infection, we sought to determine whether LSD1-deficient CD8 T cells displayed markers of an exhausted phenotype. To test this, cytokine expression for these cells were compared to WT. CD8 T cells from LcKO mice produced increased levels of TNFα and IL-2 but had decreased levels of IFNγ (Fig. 3C). This demonstrates that despite the increased levels of PD-1 expressed by LcKO cells, these cells do not appear to be exhausted. To rule out the possibility that the observed increase in PD-1 levels was not due to persistent antigen, we measured the viral titers from LcKO and WT mice at day 8 following Armstrong infection and found that both LSD1-deficient and sufficient mice cleared the infection by this time point (data not shown). In line with this, there was no difference in the frequency of antigen specific cells between the LcKO and WT mice (Fig. 3D). Taken together, these results demonstrate that despite increased levels of PD-1, LSD1 deficient CD8 T cells are functional and capable of clearing virus effectively and that elevated PD-1 levels are not a result of persistent antigen.

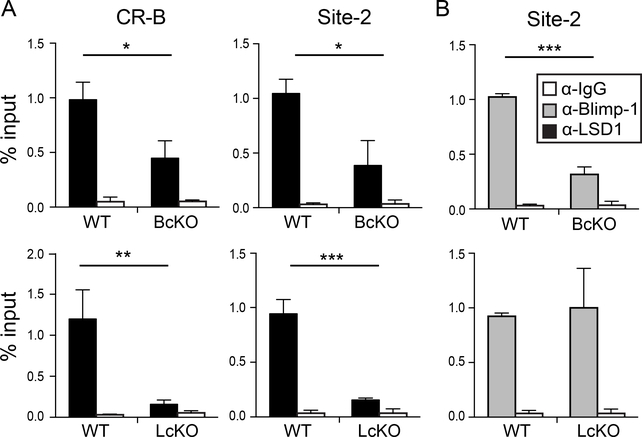

Blimp-1 recruits LSD1 to Pdcd1

To determine if LSD1 interacts directly with the Pdcd1 locus concurrent with PD-1 downregulation, and whether it is recruited there by Blimp-1, ChIP was performed on ex vivo αCD3/CD28 stimulated splenic CD8 T cells isolated from LcKO and BcKO animals, as well as the corresponding Cre− controls (WT). At day 4, when PD-1 expression has nearly returned to baseline levels (Fig. 2A), LSD1 was bound to Site 2 (Blimp-1 binding site(39)) and CR-B region in WT mice (Fig. 4A). This indicates a direct interaction with the locus and suggests that LSD1 itself directly represses Pdcd1 transcription. However, LSD-1 binding was not observed in BcKO mice concurrent with a loss of Blimp-1 at the Pdcd1 locus (Fig. 4A, B), indicating that Blimp-1 is necessary to recruit LSD1 to the region. Importantly, LSD1 binding was minimally observed at the locus in LcKO cells, indicating that the conditional deletion was efficient (Fig. 4A). However, Blimp-1 was still bound in LcKO mice (Fig. 4B), indicating that Blimp-1 is capable of independently interacting with Pdcd1. These data demonstrate that LSD1 interacts directly with the Pdcd1 locus, corresponding with suppression of Pdcd1 expression ex vivo, and requires Blimp-1.

Figure 4. Blimp-1 recruits LSD1 to the Pdcd1 locus.

CD8 T cells from LcKO, BcKO, and WT control mice were isolated by magnetic separation and then stimulated with αCD3/CD28 beads for 96 hours. Chromatin was prepared from collected cells and then subject to ChIP. (A) Binding of LSD1 to the CR-B and site-2 regions of the Pdcd1 locus. (B) Binding of Blimp-1 to site 2 of the Pdcd1 locus. An α-IgG antibody was used as a control for ChIP experiments. Data are representative of three independent experiments containing 3 to mice per group. A two tailed Student’s t test was used to determine statistical significance. **, P < 0.01 ***, P < 0.001.

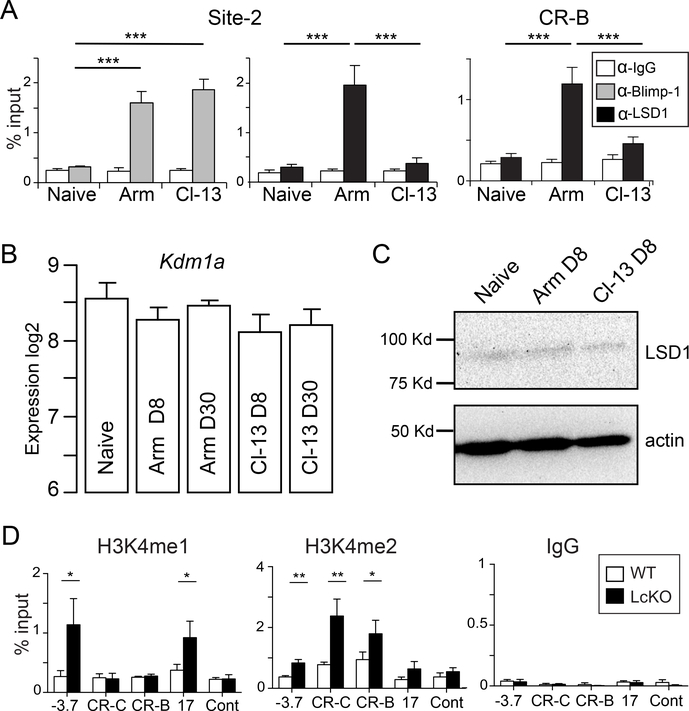

LSD1 interacts with Pdcd1 following an acute but not chronic infection

Blimp-1 binds directly to Pdcd1 following an acute infection, and acts as a transcriptional repressor (19). However, during a chronic infection, Blimp-1 is expressed at even higher levels, and was correlated with maximal PD-1 expression (21). To determine if Blimp-1 interacted directly with Pdcd1 during chronic inflammation in vivo, ChIP was performed on virus-specific CD8 T cells from naïve, day 8 acutely-infected (Armstrong), or day 8 chronically-infected (Clone-13) mice. As we previously reported, Blimp-1 was bound to Pdcd1 following acute infection (19). LSD1 was also bound at both site-2 and CR-B, correlating with its repressive role (Fig. 5A). Blimp-1 was also bound at day 8 during a chronic infection (Fig. 5A). Importantly, in this setting, LSD1 was not recruited to the region even though Blimp-1 was bound. To rule out the possibility of differential expression levels of LSD-1 between viral infections, we analyzed previously published (40) RNA microarray data and observed no differences (Fig. 5B). In agreement with the RNA data, there was also no observed difference in LSD1 protein level between acute and chronic viral infections at day 8 (Fig. 5C). This suggests that although Blimp-1 interacts with the Pdcd1 locus in CD8 T cells during a chronic infection setting, it fails to downregulate PD-1 levels because LSD1 is not recruited.

Figure 5. LSD1 is recruited to the Pdcd1 locus only during an acute infection.

(A) C57BL/6 mice were infected with either LCMV Armstrong (Arm) or Clone-13 (Cl-13) for 8 days. CD8 T cells were isolated by magnetic separation and subject to ChIP to assess LSD1 binding at CR-B and site-2 and Blimp-1 binding at site 2 of the Pdcd1 locus. Naïve CD8 T cells were also magnetically isolated (See Methods) from uninfected mice were used as a control, as was an α-IgG antibody. (B) Microarray RNA expression data from (40) was analyzed for Kdm1a expression (LSD1). (C) Western blot for LSD1 from lysates prepared from CD8 T cells isolated from naïve, Armstrong day 8 or Clone-13 day 8 infected C57BL/6 mice. Actin is also shown as a loading control. (D) LcKO and littermate control WT mice were infected with LCMV Armstrong. At day 8, gp33-, gp276-, and np396-specific CD8 T cells were isolated, pooled, and subjected to ChIP with α-H3K4me1 and H3K4me2 antibodies at the indicated regions of the Pdcd1 locus. For (A) and (D), data represent groups of 3 to 4 mice from two independent experiments. A two tailed Student’s t test was used to determine statistical significance between samples. *, P < 0.05 ***, P < 0.001.

LSD1 is responsible for the decommissioning of Pdcd1 enhancer elements

As LSD1 is responsible for removing the histone marks H3K4me1 and H3K4me2, we set out to determine if LcKO mice possessed increased levels of these marks at the Pdcd1 locus. To test this, LcKO and Cre− control (WT) mice were infected with LCMV Armstrong for 8 days. Antigen specific (pooled gp33, gp276, np396) CD8 T cells were isolated by FACS and subjected to ChIP for H3K4me1 and H3K4me2 at key regulatory regions across the Pdcd1 locus. CD8 T cells from LcKO mice showed enrichment for H3K4me1 at the −3.7 and +17.1 regions compared to WT cells (Fig. 5D). Enrichment for H3K4me2 was also observed in the LcKO CD8 T cells at the CR-B, CR-C, and −3.7 regulatory elements. The increased levels of these active histone marks correlated with the elevated levels of PD-1 expressed by LcKO CD8 T cells and mirrors the histone pattern observed in the PD-1 expressing cells at day 8 during chronic infection (Fig. 1C). Together, these results demonstrate that LSD1 is responsible for removing the activating histone marks H3K4me1 and H3K4me2 from the Pdcd1 locus and suggest that LSD1 downregulates PD-1 expression by facilitating the removal of active histone marks after being recruited to locus by Blimp-1 during an acute viral infection.

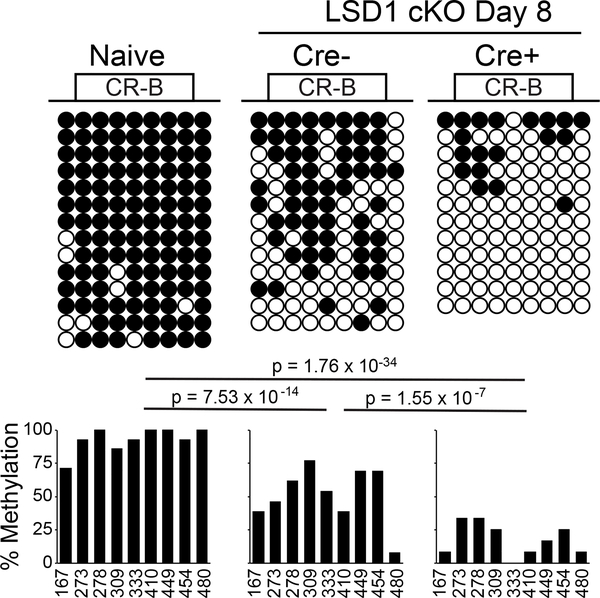

Epigenetic silencing of the locus following acute infection is enforced by LSD1

We previously showed that during the course of LCMV Armstrong infection antigen specific CD8 T cells initially lose CpG methylation at a region near CR-B (2). As the infection wanes and PD-1 levels return to near baseline, DNA methylation in that region reappears. Thus, loss of CpG methylation at the Pdcd1 locus is correlated with gene expression, and reappearance of methylation is concurrent with gene silencing. Since de novo DNA methylation is dependent on an H3K4me0 methylation state (41, 42) and LSD1 has been shown to catalyze the removal of H3K4me1 and H3K4me2 (Fig. 5C), as well as being important for global DNA methylation (43), we sought to determine if remethylation of the Pdcd1 was altered in LcKO mice during an acute infection. In accordance with the remethylation observed in WT animals at day 8 after LCMV Armstrong infection (2), WT control mice showed a relative abundance of CpG methylation across the CR-B region of Pdcd1 (Fig. 6). In contrast, LSD1-deficient CD8 T cells, which have elevated levels of PD-1 expression at this time (Fig. 3), showed minimal remethylation of the locus with a majority of alleles analyzed exhibiting either no methylation or only a handful of methylated CpGs across the region (Fig. 6). This suggests that the inability to remove H3K4 methylation in LSD1-deficient CD8 T cells inhibits the acquisition of DNA methylation, which leads to a failure to fully silence PD-1, thereby providing a further mechanism for retaining prolonged gene expression.

Figure 6. LSD1 deficient CD8 T cells fail to remethylate the Pdcd1 locus during acute infection.

LcKO and and LSD1fl/fCre− (WT) control mice were infected with LCMV Armstrong for 8 days. CD8 T cells from these mice or naïve, uninfected Cre- mice were isolated by MACS, and tetramer-specific cells were sorted by FACS. DNA from each population was bisulfite converted and PCR amplified. 8 clones from each mouse were sequenced, and incomplete sequences were discarded. At each CpG site across the CR-B region, the presence of DNA methylation within each clone is indicated by a closed circle and unmethylated CpG sites are indicated by an open circle. Frequency of methylation at each site across all clones is indicated in the corresponding bar graph. Data are combined from 2 biological replicates. Statistical significance was determined using a Fisher’s Exact Test and the P values are indicated.

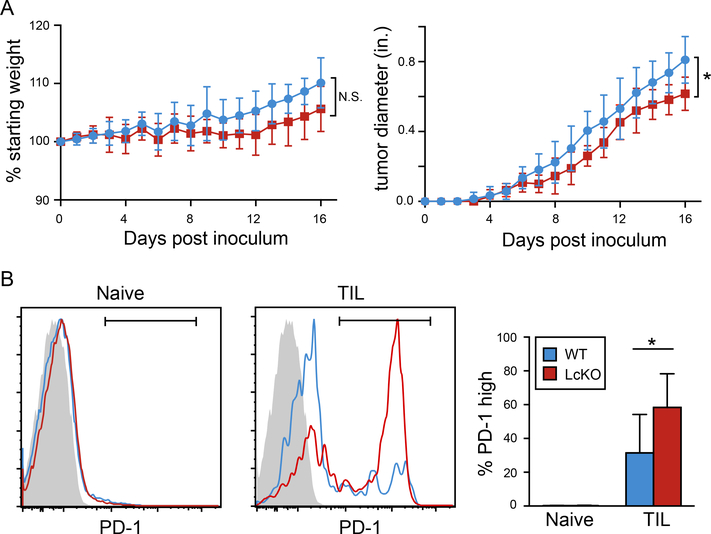

Increased frequency of PD-1 expressing CD8 T cells in the absence of LSD1 during melanoma

In order to investigate whether LSD1 deletion had an effect on PD-1 expression and disease progression in another model, we employed the B16 melanoma model (44). LcKO and Cre− littermate controls were injected with 1×106 tumor cells and mice were checked for weight and tumor size daily. Compared to each other, LcKO and WT mouse weights mice did not statistically differ throughout the course of the experiment; however, tumor growth appeared to be statistically lower in the mice with LSD-deficient CD8 T cells (Fig. 7A). Examination of the tumor infiltrating CD8+ T cells (TILs) showed that the LcKO mice had a higher frequency of PD-1hi cells compared to WT control animals, suggesting that LSD1 deficiency plays a role in the expression of PD-1 in a non-viral inflammatory model (Fig. 7B).

Figure 7. Percent PD-1 positive cells is increased in tumors from mice with LSD1-deficient CD8 T cells.

LcKO and LSD1fl/fCre− (WT) control were injected with 1×106 tumor cells and analyzed at days 16 or 17 post inoculation. (A) Percent starting weight and tumor diameter (inches) from mice during the 16-day time course. (B) At the end of the experiment, cells were collected from the tumor and subjected to flow cytometry. Activated CD8 T cells (CD44hi CD62Llow) were gated on for their percentage of PD-1hi cells in both the spleen and tumor (TIL). The summary graph in B shows the average of two independent experiments where the end points were day 16 and 17 post tumor cell inoculation. Significance was calculated in A using a two-way ANOVA (P = 0.015) and a Student’s t test in B. *, P < 0.05.

Discussion

Multiple recent studies have highlighted the important effects of dynamic epigenetic regulation in driving immune responses (45–48). Here, we demonstrate that LSD1 is a novel epigenetic repressor of PD-1 expression. Ex-vivo stimulated LSD1-deficient CD8 T cells displayed increased levels of PD-1 expression compared to WT cells. LCMV-specific CD8 T cells also displayed increased PD-1 expression levels at day 8 following acute infection, but not chronic. Blimp-1 was identified as necessary to recruit LSD1 to Pdcd1 regulatory regions using LSD1 and Blimp-1 conditional knockout mice. Our results show that LSD1 is capable of binding at the CR-B region as well as the Blimp-1 biding site located 575 base pairs upstream. These data could suggest that LSD1 is recruited to the locus through multiple factors binding to discrete sites or that LSD1 accumulates across a locus once it is recruited. In both cases, such an event could result in the decommissioning of the active histone marks as shown here for Pdcd1. Although Blimp-1 associates with Pdcd1 in both acute (PD-1 silencing) and chronic (PD-1 permissive) inflammatory environments, LSD-1 is only recruited to the locus in the acute infection, providing a mechanistic epigenetic switch for the differential expression of PD-1 in the two infectious systems. Furthermore, the association of LSD1 with Pdcd1 during resolution of an acute infection correlates with and is necessary for the disappearance of the active histone modifications targeted by LSD1: H3K4me1 and H3K4me2. Additionally, the actions of LSD1 and the removal these histone marks correlate with the remethylation of the CR-B upstream, regulatory region and the silencing of PD-1 protein expression.

The results from this work also show that in a melanoma cancer model, the tumor infiltrating CD8 T cells from the LcKO mice displayed higher PD-1 levels compared to wild-type controls. This matches the observation seen in the acute viral infection where activated CD8 T cells deficient in LSD1 expressed higher levels of PD-1. Despite the increased presence of PD-1hi cells, the overall health (as measured by weight loss) of the conditional knockout animals was not significantly different than in the wild-type mice. However, LcKO mice had smaller tumors across the time course. This could be due to LSD1 controlling other genes that also show enhanced expression when LSD1 is deleted in this model. In line with this, deletion of LSD1 in plasmablasts resulted in the upregulation of 471 genes compared to wild-type cells (28). Pharmacological inhibition of epigenetic modifiers, including LSD1 are effective in treating some cancers as a method to directly inhibit genes aberrantly expressed in the cancer itself (49). Thus, although the model used in our research does not affect LSD1 within the tumor cells, the higher PD-1 on TILs and potential subsequent cellular exhaustion could complicate this treatment strategy.

Blimp-1, a protein associated with B cell maturation into antibody-secreting plasma cells, is a critical inhibitor of Pdcd1 transcription following acute T cell stimulation (19). Increases in Blimp-1 mRNA and protein following antigen clearance are associated with concurrent decreases in PD-1. Paradoxically, if antigen persists and stimulation through the TCR continues, Blimp-1 levels nonetheless increase further (21). Whereas in an acute infection the CD8 T cells from BcKO mice showed increased PD-1, suggesting an inhibitory function, the same deletion resulted in modestly lower levels of PD-1 in a chronic infection, suggesting Blimp-1 acted as an activator. In this study, Blimp-1 was shown to be bound at Pdcd1 in both infection modalities, thereby precluding the possibility that the changing function of Blimp-1 was mediated indirectly through binding to other target genes. Instead, recruitment of LSD1, which was dependent on the presence of Blimp-1, was found to be unique to acute infections.

Many mechanisms could potentially explain the failure of Blimp-1 to recruit LSD1 in a chronic infection setting. Splice variants of Blimp-1 have been shown both to be involved in different timing of expression (50) and to have alternative functions (51). These include variants that alter Blimp-1’s ability to recruit additional transcription factors while preserving its ability to bind DNA (21, 52). Other biochemical mechanisms could also be involved, including posttranslational modifications of either Blimp-1 or LSD1. Furthermore, other factors binding to locus could sterically hinder or aid LSD1 recruitment. Another mechanism explaining the differential binding of LSD1 during acute and chronic infection could be expression levels of LSD1, however analysis of published transcriptomics data sets (40) suggest that this is not the case.

For Pdcd1, LSD1 provides an important mechanistic link between the dynamics of histone code modifications, DNA methylation, and gene expression of this critical immune regulatory locus. Dynamic molecular events at the Pdcd1 locus are mirrored in chromatin accessibility patterns and DNA methylation patterns that change as CD8 T cells differentiate from naïve to effector, memory, and exhausted cells at both Pdcd1, as well as many other T cell expressed genes (2, 10, 15, 46–48). While this study focused on the effects of epigenetics on determining the expression of a single immune-related gene, LSD1 is most likely to have additional consequences on regulating CD8 T cell differentiation and gene expression. Irrespective of LSD1’s additional roles in modulating CD8 T cell gene expression, the work presented in this study establishes a clear mechanism for LSD1 to differentially regulate the expression levels of PD-1 during acute and chronic viral infections.

Supplementary Material

Key Points.

LSD1 suppress PD-1 expression following acute infection or ex vivo induction.

Blimp-1 binding to the Pdcd1 locus is required to recruit LSD1.

LSD1 is required to fully remethylate the Pdcd1 proximal promoter region.

Acknowledgments

We thank members of the lab for helpful critical and comments during the course of this work. We thank Royce Butler for expert animal husbandry. We thank Dr. Rafi Ahmed for helpful discussions regarding our work and for providing LCMV viral strains; the National Institute of Health Tetramer Core Facility for providing LCMV specific tetramers; and also R. Karaffa and K. Fife for cell sorting from the Emory University School of Medicine Flow Cytometry Core.

This work was supported by National Institute of Health grants: R01 AI113021 and T32 GM0008490 to J.M.B; and F31 AI112261 to B.G.B.

Abbreviations

- Blimp-1

B lymphocyte induced maturation protein-1

- ChIP

Chromatin immunoprecipitation assay

- CR-B

Conserved region B

- CR-C

Conserved region C

- LCMV

Lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus

- LSD1

Lysine specific demethylase 1

- PD-1

Programmed cell death 1

Footnotes

Disclosures

The authors have no financial conflicts of interest.

Literature Cited

- 1.Barber DL, Wherry EJ, Masopust D, Zhu B, Allison JP, Sharpe AH, Freeman GJ, and Ahmed R. 2006. Restoring function in exhausted CD8 T cells during chronic viral infection. Nature 439: 682–687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Youngblood B, Oestreich KJ, Ha SJ, Duraiswamy J, Akondy RS, West EE, Wei Z, Lu P, Austin JW, Riley JL, Boss JM, and Ahmed R. 2011. Chronic virus infection enforces demethylation of the locus that encodes PD-1 in antigen-specific CD8(+) T cells. Immunity 35: 400–412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Day CL, Kaufmann DE, Kiepiela P, Brown JA, Moodley ES, Reddy S, Mackey EW, Miller JD, Leslie AJ, DePierres C, Mncube Z, Duraiswamy J, Zhu B, Eichbaum Q, Altfeld M, Wherry EJ, Coovadia HM, Goulder PJ, Klenerman P, Ahmed R, Freeman GJ, and Walker BD. 2006. PD-1 expression on HIV-specific T cells is associated with T-cell exhaustion and disease progression. Nature 443: 350–354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Trautmann L, Janbazian L, Chomont N, Said EA, Gimmig S, Bessette B, Boulassel MR, Delwart E, Sepulveda H, Balderas RS, Routy JP, Haddad EK, and Sekaly RP. 2006. Upregulation of PD-1 expression on HIV-specific CD8+ T cells leads to reversible immune dysfunction. Nature medicine 12: 1198–1202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Freeman GJ, Wherry EJ, Ahmed R, and Sharpe AH. 2006. Reinvigorating exhausted HIV-specific T cells via PD-1-PD-1 ligand blockade. J Exp Med 203: 2223–2227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wherry EJ, Blattman JN, Murali-Krishna K, van der Most R, and Ahmed R. 2003. Viral persistence alters CD8 T-cell immunodominance and tissue distribution and results in distinct stages of functional impairment. J Virol 77: 4911–4927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Freeman GJ, Long AJ, Iwai Y, Bourque K, Chernova T, Nishimura H, Fitz LJ, Malenkovich N, Okazaki T, Byrne MC, Horton HF, Fouser L, Carter L, Ling V, Bowman MR, Carreno BM, Collins M, Wood CR, and Honjo T. 2000. Engagement of the PD-1 immunoinhibitory receptor by a novel B7 family member leads to negative regulation of lymphocyte activation. J Exp Med 192: 1027–1034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Blank C, Brown I, Peterson AC, Spiotto M, Iwai Y, Honjo T, and Gajewski TF. 2004. PD-L1/B7H-1 inhibits the effector phase of tumor rejection by T cell receptor (TCR) transgenic CD8+ T cells. Cancer Res 64: 1140–1145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chemnitz JM, Parry RV, Nichols KE, June CH, and Riley JL. 2004. SHP-1 and SHP-2 associate with immunoreceptor tyrosine-based switch motif of programmed death 1 upon primary human T cell stimulation, but only receptor ligation prevents T cell activation. J Immunol 173: 945–954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Youngblood B, Noto A, Porichis F, Akondy RS, Ndhlovu ZM, Austin JW, Bordi R, Procopio FA, Miura T, Allen TM, Sidney J, Sette A, Walker BD, Ahmed R, Boss JM, Sekaly RP, and Kaufmann DE. 2013. Cutting edge: Prolonged exposure to HIV reinforces a poised epigenetic program for PD-1 expression in virus-specific CD8 T cells. Journal of immunology 191: 540–544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Utzschneider DT, Legat A, Fuertes Marraco SA, Carrie L, Luescher I, Speiser DE, and Zehn D. 2013. T cells maintain an exhausted phenotype after antigen withdrawal and population reexpansion. Nat Immunol 14: 603–610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Oestreich KJ, Yoon H, Ahmed R, and Boss JM. 2008. NFATc1 regulates PD-1 expression upon T cell activation. J Immunol 181: 4832–4839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Xiao G, Deng A, Liu H, Ge G, and Liu X. 2012. Activator protein 1 suppresses antitumor T-cell function via the induction of programmed death 1. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 109: 15419–15424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Austin JW, Lu P, Majumder P, Ahmed R, and Boss JM. 2014. STAT3, STAT4, NFATc1, and CTCF regulate PD-1 through multiple novel regulatory regions in murine T cells. J Immunol 192: 4876–4886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Scott-Browne JP, Lopez-Moyado IF, Trifari S, Wong V, Chavez L, Rao A, and Pereira RM. 2016. Dynamic Changes in Chromatin Accessibility Occur in CD8(+) T Cells Responding to Viral Infection. Immunity 45: 1327–1340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sen DR, Kaminski J, Barnitz RA, Kurachi M, Gerdemann U, Yates KB, Tsao HW, Godec J, LaFleur MW, Brown FD, Tonnerre P, Chung RT, Tully DC, Allen TM, Frahm N, Lauer GM, Wherry EJ, Yosef N, and Haining WN. 2016. The epigenetic landscape of T cell exhaustion. Science 354: 1165–1169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Staron MM, Gray SM, Marshall HD, Parish IA, Chen JH, Perry CJ, Cui G, Li MO, and Kaech SM. 2014. The transcription factor FoxO1 sustains expression of the inhibitory receptor PD-1 and survival of antiviral CD8(+) T cells during chronic infection. Immunity 41: 802–814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kao C, Oestreich KJ, Paley MA, Crawford A, Angelosanto JM, Ali MA, Intlekofer AM, Boss JM, Reiner SL, Weinmann AS, and Wherry EJ. 2011. Transcription factor T-bet represses expression of the inhibitory receptor PD-1 and sustains virus-specific CD8+ T cell responses during chronic infection. Nat Immunol 12: 663–671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lu P, Youngblood BA, Austin JW, Rasheed Mohammed AU, Butler R, Ahmed R, and Boss JM. 2014. Blimp-1 represses CD8 T cell expression of PD-1 using a feed-forward transcriptional circuit during acute viral infection. The Journal of experimental medicine 211: 515–527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McPherson RC, Konkel JE, Prendergast CT, Thomson JP, Ottaviano R, Leech MD, Kay O, Zandee SE, Sweenie CH, Wraith DC, Meehan RR, Drake AJ, and Anderton SM. 2015. Epigenetic modification of the PD-1 (Pdcd1) promoter in effector CD4(+) T cells tolerized by peptide immunotherapy. eLife 4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shin H, Blackburn SD, Intlekofer AM, Kao C, Angelosanto JM, Reiner SL, and Wherry EJ. 2009. A role for the transcriptional repressor Blimp-1 in CD8(+) T cell exhaustion during chronic viral infection. Immunity 31: 309–320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shin HM, Kapoor VN, Guan T, Kaech SM, Welsh RM, and Berg LJ. 2013. Epigenetic modifications induced by Blimp-1 Regulate CD8(+) T cell memory progression during acute virus infection. Immunity 39: 661–675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Su ST, Ying HY, Chiu YK, Lin FR, Chen MY, and Lin KI. 2009. Involvement of histone demethylase LSD1 in Blimp-1-mediated gene repression during plasma cell differentiation. Mol Cell Biol 29: 1421–1431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yu J, Angelin-Duclos C, Greenwood J, Liao J, and Calame K. 2000. Transcriptional repression by blimp-1 (PRDI-BF1) involves recruitment of histone deacetylase. Mol Cell Biol 20: 2592–2603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gyory I, Wu J, Fejer G, Seto E, and Wright KL. 2004. PRDI-BF1 recruits the histone H3 methyltransferase G9a in transcriptional silencing. Nat Immunol 5: 299–308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jenuwein T, and Allis CD. 2001. Translating the histone code. Science 293: 1074–1080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shi Y, Lan F, Matson C, Mulligan P, Whetstine JR, Cole PA, Casero RA, and Shi Y. 2004. Histone demethylation mediated by the nuclear amine oxidase homolog LSD1. Cell 119: 941–953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Haines RR, Barwick BG, Scharer CD, Majumder P, Randall TD, and Boss JM. 2018. The Histone Demethylase LSD1 Regulates B Cell Proliferation and Plasmablast Differentiation. J Immunol 201: 2799–2811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang J, Scully K, Zhu X, Cai L, Zhang J, Prefontaine GG, Krones A, Ohgi KA, Zhu P, Garcia-Bassets I, Liu F, Taylor H, Lozach J, Jayes FL, Korach KS, Glass CK, Fu XD, and Rosenfeld MG. 2007. Opposing LSD1 complexes function in developmental gene activation and repression programmes. Nature 446: 882–887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jacob J, and Baltimore D. 1999. Modelling T-cell memory by genetic marking of memory T cells in vivo. Nature 399: 593–597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Matloubian M, Somasundaram T, Kolhekar SR, Selvakumar R, and Ahmed R. 1990. Genetic basis of viral persistence: single amino acid change in the viral glycoprotein affects ability of lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus to persist in adult mice. The Journal of experimental medicine 172: 1043–1048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ahmed R, Salmi A, Butler LD, Chiller JM, and Oldstone MB. 1984. Selection of genetic variants of lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus in spleens of persistently infected mice. Role in suppression of cytotoxic T lymphocyte response and viral persistence. J Exp Med 160: 521–540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bally AP, Tang Y, Lee JT, Barwick BG, Martinez R, Evavold BD, and Boss JM. 2017. Conserved Region C Functions To Regulate PD-1 Expression and Subsequent CD8 T Cell Memory. Journal of immunology 198: 205–217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yoon HS, Scharer CD, Majumder P, Davis CW, Butler R, Zinzow-Kramer W, Skountzou I, Koutsonanos DG, Ahmed R, and Boss JM. 2012. ZBTB32 is an early repressor of the CIITA and MHC class II gene expression during B cell differentiation to plasma cells. J Immunol 189: 2393–2403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Beresford GW, and Boss JM. 2001. CIITA coordinates multiple histone acetylation modifications at the HLA-DRA promoter. Nature immunology 2: 652–657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Scharer CD, Barwick BG, Youngblood BA, Ahmed R, and Boss JM. 2013. Global DNA methylation remodeling accompanies CD8 T cell effector function. J Immunol 191: 3419–3429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bally AP, Austin JW, and Boss JM. 2016. Genetic and Epigenetic Regulation of PD-1 Expression. J Immunol 196: 2431–2437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Creyghton MP, Cheng AW, Welstead GG, Kooistra T, Carey BW, Steine EJ, Hanna J, Lodato MA, Frampton GM, Sharp PA, Boyer LA, Young RA, and Jaenisch R. 2010. Histone H3K27ac separates active from poised enhancers and predicts developmental state. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 107: 21931–21936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nanou A, Toumpeki C, Lavigne MD, Lazou V, Demmers J, Paparountas T, Thanos D, and Katsantoni E. 2017. The dual role of LSD1 and HDAC3 in STAT5-dependent transcription is determined by protein interactions, binding affinities, motifs and genomic positions. Nucleic Acids Res 45: 142–154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Doering TA, Crawford A, Angelosanto JM, Paley MA, Ziegler CG, and Wherry EJ. 2012. Network analysis reveals centrally connected genes and pathways involved in CD8+ T cell exhaustion versus memory. Immunity 37: 1130–1144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ooi SK, Qiu C, Bernstein E, Li K, Jia D, Yang Z, Erdjument-Bromage H, Tempst P, Lin SP, Allis CD, Cheng X, and Bestor TH. 2007. DNMT3L connects unmethylated lysine 4 of histone H3 to de novo methylation of DNA. Nature 448: 714–717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jia D, Jurkowska RZ, Zhang X, Jeltsch A, and Cheng X. 2007. Structure of Dnmt3a bound to Dnmt3L suggests a model for de novo DNA methylation. Nature 449: 248–251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wang J, Hevi S, Kurash JK, Lei H, Gay F, Bajko J, Su H, Sun W, Chang H, Xu G, Gaudet F, Li E, and Chen T. 2009. The lysine demethylase LSD1 (KDM1) is required for maintenance of global DNA methylation. Nat Genet 41: 125–129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Prevost-Blondel A, Zimmermann C, Stemmer C, Kulmburg P, Rosenthal FM, and Pircher H. 1998. Tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes exhibiting high ex vivo cytolytic activity fail to prevent murine melanoma tumor growth in vivo. Journal of immunology 161: 2187–2194. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Scharer CD, Blalock EL, Barwick BG, Haines RR, Wei C, Sanz I, and Boss JM. 2016. ATAC-seq on biobanked specimens defines a unique chromatin accessibility structure in naive SLE B cells. Sci Rep 6: 27030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Scharer CD, Bally AP, Gandham B, and Boss JM. 2017. Cutting Edge: Chromatin Accessibility Programs CD8 T Cell Memory. J Immunol 198: 2238–2243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sen DR, Kaminski J, Barnitz RA, Kurachi M, Gerdemann U, Yates KB, Tsao HW, Godec J, LaFleur MW, Brown FD, Tonnerre P, Chung RT, Tully DC, Allen TM, Frahm N, Lauer GM, Wherry EJ, Yosef N, and Haining WN. 2016. The epigenetic landscape of T cell exhaustion. Science. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pauken KE, Sammons MA, Odorizzi PM, Manne S, Godec J, Khan O, Drake AM, Chen Z, Sen D, Kurachi M, Barnitz RA, Bartman C, Bengsch B, Huang AC, Schenkel JM, Vahedi G, Haining WN, Berger SL, and Wherry EJ. 2016. Epigenetic stability of exhausted T cells limits durability of reinvigoration by PD-1 blockade. Science. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mohammad H, Smitheman K, Cusan M, Liu Y, Pappalardi M, Federowicz K, Van Aller G, Kasparec J, Tian X, Suarez D, Rouse M, Schneck J, Carson J, McDevitt P, Ho T, McHugh C, Miller W, Johnson N, Armstrong SA, and Tummino P. 2013. Inhibition Of LSD1 As a Therapeutic Strategy For The Treatment Of Acute Myeloid Leukemia. 122: 3964–3964. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Morgan MA, Magnusdottir E, Kuo TC, Tunyaplin C, Harper J, Arnold SJ, Calame K, Robertson EJ, and Bikoff EK. 2009. Blimp-1/Prdm1 alternative promoter usage during mouse development and plasma cell differentiation. Mol Cell Biol 29: 5813–5827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Morgan MA, Mould AW, Li L, Robertson EJ, and Bikoff EK. 2012. Alternative splicing regulates Prdm1/Blimp-1 DNA binding activities and corepressor interactions. Mol Cell Biol 32: 3403–3413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Keller AD, and Maniatis T. 1992. Only two of the five zinc fingers of the eukaryotic transcriptional repressor PRDI-BF1 are required for sequence-specific DNA binding. Mol Cell Biol 12: 1940–1949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.