Abstract

Specific deletion of the tumor suppressor TRAF3 from B lymphocytes in mice leads to the prolonged survival of mature B cells and expanded B cell compartments in secondary lymphoid organs. In the present study, we investigated the metabolic basis of TRAF3-mediated regulation of B cell survival by employing metabolomic, lipidomic and transcriptomic analyses. We compared the polar metabolites, lipids and metabolic enzymes of resting splenic B cells purified from young adult B cell-specific Traf3−/− (B-Traf3−/−) and littermate control (LMC) mice. We found that multiple metabolites, lipids and enzymes regulated by TRAF3 in B cells are clustered in the choline metabolic pathway. Using stable isotope labeling, we demonstrated that phosphocholine and phosphatidylcholine biosynthesis was markedly elevated in Traf3−/− mouse B cells and decreased in TRAF3-reconstituted human multiple myeloma cells. Furthermore, pharmacological inhibition of choline kinase α (Chkα), an enzyme that catalyzes phosphocholine synthesis and was strikingly increased in Traf3−/− B cells, substantially reversed the survival phenotype of Traf3−/− B cells both in vitro and in vivo. Taken together, our results indicate that enhanced phosphocholine and phosphatidylcholine synthesis supports the prolonged survival of Traf3−/− B lymphocytes. Our findings suggest that TRAF3-regulated choline metabolism has diagnostic and therapeutic value for B cell malignancies with TRAF3 deletions or relevant mutations.

Introduction

Aberrant B cell survival is an important contributing factor to the pathogenesis of B cell malignancies, which comprise >50% of blood cancers and >80% of lymphomas (1–3). We and others have recently identified TRAF3, a cytoplasmic adaptor protein, as a critical regulator of cell survival and tumor suppressor in mature B lymphocytes (4–9). Deletions and inactivating mutations of the TRAF3 gene are one of the most frequently occurring genetic alterations in a variety of human B cell malignancies (9, 10), including multiple myeloma (MM, 17%) (6, 11), gastric and splenic marginal zone lymphoma (G-MZL, 21%; S-MZL, 10%) (12, 13), diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL, 14%) (14), B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia (B-CLL, 13%) (15), Hodgkin lymphoma (HL, 15%) (16) and Waldenstrom’s macroglobulinemia (WM, 5%) (17).

TRAF3, a member of the tumor necrosis factor receptor-associated factor (TRAF) family, regulates the signal transduction pathways of a diverse array of immune receptors, including the tumor necrosis factor receptor (TNF-R) superfamily, Toll-like receptors (TLRs), NOD-like receptors (NLRs), RIG-I-like receptors (RLRs) and cytokine receptors (10, 18, 19). Specifically in B lymphocytes, TRAF3 directly binds to two receptors pivotal for B cell physiology, the BAFF receptor (BAFF-R) and CD40, which are required for B cell survival and activation, respectively (20, 21). Specific deletion of the Traf3 gene in B lymphocytes results in severe peripheral B cell hyperplasia in mice due to the prolonged survival of mature B cells independent of the principle B cell survival factor BAFF (4, 5). This effect of TRAF3 deficiency in B cells eventually leads to spontaneous development of splenic MZL and B1 lymphomas at high incidence by 18 months of age (8). These in vivo findings are consistent with the frequent deletions and inactivating mutations of the TRAF3 gene identified in human B cell neoplasms, demonstrating the tumor suppressive role of TRAF3 in mature B lymphocytes.

The signal transduction pathway underlying TRAF3-mediated regulation of B cell survival has been elucidated in previous studies. It was found that in the absence of stimulation, TRAF3 constitutively binds to NIK (the upstream kinase of the NF-κB2 pathway) and TRAF2, while TRAF2 also constitutively associates with cIAP1/2 (18, 22). In this complex, cIAP1/2 induces K48-linked polyubiquitination of NIK, thereby targeting NIK for proteasomal degradation and thus inhibiting NF-κB2 activation (23–26). Upon BAFF or CD154 stimulation, trimerized BAFF-R or CD40 recruits TRAF3, TRAF2 and cIAP1/2 to the plasma membrane, releasing NIK from the TRAF3-TRAF2-cIAP1/2 complex and allowing NIK to accumulate in the cytoplasm (26–28). Accumulated NIK protein subsequently induces the activation of IKKα and NF-κB2, and activated NF-κB2 in turn promotes the expression of anti-apoptotic proteins of the Bcl-2 family (such as Bcl-2, Bcl-xL and Mcl-1) to induce B cell survival (18, 22, 29). Specific deletion of TRAF3, TRAF2 or cIAP1/2 in B cells all results in similar phenotype in mice, with BAFF-independent constitutive NF-κB2 activation and prolonged survival of mature B lymphocytes (4, 5, 28). However, it remains unclear whether this pathway regulates cellular metabolism to control B cell survival.

In the present study, we aimed to investigate the metabolic basis of the tumor suppressor TRAF3-mediated regulation of B cell survival. To address this, we first employed unbiased metabolome and lipidome screening approaches to compare the metabolism of resting splenic B cells purified from young adult B cell-specific Traf3−/− (B-Traf3−/−) and littermate control (LMC) mice. To understand how TRAF3 regulates B cell metabolism, we performed transcriptome profiling to identify metabolic enzymes downstream of TRAF3 signaling. Our results revealed that multiple metabolites, lipids and enzymes regulated by TRAF3 in B cells are clustered in the choline metabolic pathway. Using stable isotope labeling, we demonstrated the increased biosynthesis of phosphocholine and phosphatidylcholine in Traf3−/− B cells. To assess the functional importance of elevated choline metabolism, we examined the effects of two choline kinase α (Chkα) inhibitors, MN58B and RSM932A. We found that both MN58B and RSM932A inhibited the survival of Traf3−/− B cells both in vitro and in vivo. Taken together, we have identified phosphocholine and phosphatidylcholine biosynthesis as a TRAF3-regulated metabolic pathway critical for B cell survival.

Materials and methods

Mice and cell lines

Traf3flox/floxCD19+/Cre (B-Traf3−/−) and Traf3flox/flox (littermate control, LMC) mice were generated as previously described (4). All experimental mice for this study were produced by breeding of Traf3flox/flox mice with Traf3flox/floxCD19+/Cre mice. All mice were kept in specific pathogen-free conditions in the Animal Facility at Rutgers University, and were used in accordance with NIH guidelines and under an animal protocol (Protocol # 08–048) approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of Rutgers University. Equal numbers of male and female mice were used in this study.

Traf3−/− mouse B lymphoma cell lines 27–9.5.3 (27–9) and 105–8.1B6 (105–8) were generated and cultured as described previously (8, 30). Human multiple myeloma (MM) cell lines 8226 (contains bi-allelic TRAF3 deletions), KMS11 (contains bi-allelic TRAF3 deletions), and LP1 (contains inactivating TRAF3 frameshift mutations) were kindly provided by Dr. Leif Bergsagel (Mayo Clinic, Scottsdale, AZ), and were cultured as previously described (30). TRAF3-sufficient mouse B lymphoma cell line A20.2J was generously provided by Dr. Gail Bishop (University of Iowa, Iowa City, IA) (30). TRAF3-sufficient mouse B lymphoma cell line m12.4.1 as well as human Burkitt’s B lymphoma cell lines Ramos and Daudi were purchased from American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Manassas, VA) (30). All mouse and human B lymphoma cell lines were cultured as previously described (30).

Reagents and antibodies

Tissue culture supplements including stock solutions of sodium pyruvate, L-glutamine, non-essential amino acids, and HEPES (pH 7.55) were from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA). Trimethyl-D9-choline ([2H]9-Cho) was purchased from Cambridge Isotope Laboratories (Tewksbury, MA). MN58B and RSM932A were obtained from Aobious (Gloucester, MA). Antibodies (Abs) against Chkα were from Abcam (Cambridge, MA). Polyclonal rabbit Abs to TRAF3 (H122) were from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA). Anti-actin Ab was from Chemicon (Temecula, CA). HRP-labeled secondary Abs were from Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, Inc. (West Grove, PA).

Splenic B cell purification, culture and stimulation

Mouse splenic B cells were purified using anti-mouse CD43-coated magnetic beads and a MACS separator (Miltenyi Biotec Inc.) following the manufacturer’s protocols as previously described (4). The purity of the isolated B cell population was monitored by FACS analysis, and cell preparations of >98% purity were used for metabolomic, lipidomic and transcriptomic analyses as well as protein preparation. An aliquot of purified splenic B cells were cultured ex vivo in mouse B cell medium (4) for 24 h before metabolomic and lipidomic analyses.

Water-soluble polar metabolite and lipid profiling using Liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry (LC-MS)

Traf3−/− and LMC splenic B cells were quickly washed twice with PBS. 10 million Traf3−/− and LMC splenic B cells were centrifuged at 12,000 rpm at 4°C for 5 minutes to obtain a pellet. Separate pellets were used to extract water-soluble polar metabolites and lipids, respectively. To extract water-soluble metabolites, 184 μL of methanol:H2O (80:20) + 0.5% formic acid at dry ice temperature was added to the pellet, vortexed for 5 seconds and let sit on dry ice for 10 minutes. Then 16 μL of 15% NH4HCO3 was added to neutralize the solution. The final solution was kept at −20°C for 15 minutes and the resulting mixture was transferred into an Eppendorf tube and centrifuged at 13,200 rpm at 4°C for 15 minutes. The supernatant was taken for LC-MS analysis. LC separation was achieved using a Vanquish UHPLC system (Thermo Fisher Scientific, San Jose, CA) and an Xbridge BEH Amide column (150×2mm, 2.5 μm particle size; Waters, Milford, MA). Solvent A is water: acetonitrile (95:5) with 20 mM ammonium acetate and 20 mM ammonium hydroxide at pH 9.4, and solvent B is acetonitrile. The gradient is 0 min, 90% B; 2 min, 90% B; 3 min, 75% B; 7 min, 75% B; 8 min, 70% B, 9 min, 70% B; 10 min, 50% B; 12 min, 50% B; 13 min, 25% B; 14 min, 25% B; 16 min, 0% B, 21 min, 0% B; 21.5 min, 90% B; 25 min, 90% B (31). Total running time is 25 min at a flow rate of 150 μL/min. For all experiments, 5 μL of extract was injected with column temperature at 25°C. The Q-Exactive Plus mass spectrometer was operated in both negative and positive mode scanning m/z 70–1000 with a resolution of 140,000 at m/z 200. MS parameters were as follows: sheath gas flow rate, 28 (arbitrary units); aux gas flow rate, 10 (arbitrary units); sweep gas flow rate, 1 (arbitrary unit); spray voltage, 3.3 kV; capillary temperature, 320°C; S-lens RF level, 65; AGC target, 3E6 and maximum injection time, 500 ms.

To extract lipids, 1 mL of 0.1M HCl in methanol:H2O (50:50) was added to the pellet and set in a −20°C freezer for 30 minutes. Then 0.5 mL chloroform was added to the mixture and vortexed, then set on ice for 10 min. Samples were centrifuged at 13,200 rpm for 10 min and the chloroform phase at the bottom was transferred to a glass vial as the first extract using a Hamilton syringe. Another 0.5 mL chloroform was added to the remaining material and the extraction was repeated to get a second extract. The combined extract was dried under nitrogen flow and re-dissolved in 200 μL of methanol:chloroform:2-propanol (1:1:1). Lipids were analyzed on a Q-Exactive Plus mass spectrometer coupled to a Vanquish UHPLC system (ThermoFisher Scientific). Each sample was analyzed twice using the same LC gradient but a different ionization mode on the mass spectrometer to cover both positively and negatively charged species. The LC separation was achieved on an Agilent Poroshell 120 EC-C18 column (150 × 2.1 mm, 2.7 μm particle size) at a flow rate of 150 μL/min. The gradient was 0 min, 25% B; 2 min, 25% B; 4 min, 65% B; 16 min, 100 % B; 20 min, 100% B; 21 min, 25% B; 27 min, 25% B (32). Solvent A is 1 mM Ammonium acetate + 0.2% acetic acid in methanol:H2O (10:90). Solvent B is 1 mM Ammonium acetate + 0.2% acetic acid in Methanol:2-propanol (2:98). Other MS parameters were the same as above.

Data analyses were performed using MAVEN software which allows for sample alignment, feature extraction and peak picking (33). Extracted ion chromatograms for each metabolite were manually examined to obtain its signal, using a custom-made metabolite library.

Stable isotope labeling analysis using LC-MS

To analyze kinetic choline flux into metabolic pathways, purified splenic B cells were cultured in RPMI medium containing 80 μg/mL of trimethyl-D9-choline ([2H]9-Cho). At the indicated time points, cells were centrifuged at 12,000 rpm at 4°C for 5 minutes to obtain a pellet. To extract water-soluble metabolites, 184 μL of methanol:H2O (80:20) + 0.5% formic acid at dry ice temperature was added to the pellet, vortexed for 5 seconds and set on dry ice for 10 minutes. Then 16 μL of 15% NH4HCO3 was added to neutralize the solution. The final solution was set at −20°C for 15 minutes and the resulting mixture was transferred into an Eppendorf tube and centrifuged at 13,200 rpm at 4°C for 15 minutes. The supernatant was taken for LC-MS analysis of water-soluble metabolites and their labeled forms as described above. In addition, phosphocholine (P0378, Sigma) standards in 80% methanol at concentrations of 0.5, 1.5, 5 μM were run separately to estimate the concentrations of phosphocholine in biological samples.

To extract lipids, 1 mL of chloroform was added to the remaining pellet and vortexed, then set on ice for 10 min. Samples were centrifuged at 13,200 rpm for 10 min and the chloroform phase was transferred to a glass vial. The extract was dried under nitrogen flow and re-dissolved in 200 μL of methanol:chloroform:2-propanol (1:1:1) and taken for LC-MS analysis of lipids as described above. In addition, 1,2-dipalmitoyl-rac-glycero-3-phosphocholine (P5911, Sigma) standards in the same solvent at concentrations of 0.5, 1.5, 5 μM were run separately to estimate the concentrations of phosphatidylcholine species in biological samples.

Data analyses were performed using MAVEN software (33) as described above, examining both the unlabeled and 2H-labeled forms of choline-containing water-soluble metabolites and lipids (34).

ATP measurement using an ATP Determination Kit

To specifically measure ATP concentrations, fresh lysates of purified splenic B cells were prepared using ice-cold 1.5% trichloroacetic acid (TCA) in Mammalian Cell PE LB™ Lysis Buffer (G-Biosciences, St. Louis, MO), and subsequently neutralized with 20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5 (35). ATP concentrations in lysates were determined using a luciferase-luciferin-based bioluminescence assay with an ATP Determination Kit (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) following the manufacturer’s protocol. Briefly, 10 μL of lysates was added into 90 μL of luciferase reagent and measured immediately based on the maximal light intensity of the resulting bioluminescence in a luminometer (GloMax 20/20, Promega, Fitchburg, WI) (35). A calibration curve with serial dilutions of ATP standards was prepared in each experiment. Data were normalized as nanomoles of ATP/106 cells (35).

Transcriptomic microarray analysis

Total cellular RNA was extracted from splenic B cells purified from young adult (8–12 week old) LMC and B-Traf3−/− mice using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. RNA quality was assessed on an RNA Nano Chip using an Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies, Palo Alto, CA) (36). The mRNA was amplified with a TotalPrep RNA amplification kit with a T7-oligo(dT) primer following the manufacturer’s instructions (Ambion), and microarray analysis was carried out with the Illumina Sentrix MouseRef-8 24K Array at the Burnham Institute (La Jolla, CA). Results were extracted with Illumina GenomeStudio v2011.1, background corrected and variance stabilized in R/Bioconductor using the lumi package (37, 38) and modeled in the limma package (39). The microarray analysis results have been deposited in the NIH Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database under the accession number GSE113920 (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/).

Taqman assays of the transcript expression of identified enzyme-encoding genes

Complementary DNA (cDNA) was prepared from RNA using High Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit (Applied Biosystems, Carlsbad, CA). Quantitative real-time PCR of specific genes was performed using corresponding TaqMan Gene Assay kit (Applied Biosystems) as previously described (36, 40). Briefly, real-time PCR was performed using TaqMan primers and probes (FAM-labeled) specific for mouse Chka, Lpcat1, Faah, Gdpd3, Plcd3 or Dgka. Each reaction also included the probe (VIC-labeled) and primers for mouse Actb, which served as an endogenous control. Reactions were performed on a 7500 Fast Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems). Relative mRNA expression levels of each gene were analyzed using the Sequence Detection Software (Applied Biosystems) and the comparative Ct method (ΔΔCt) as previously described (36, 40).

Protein extraction and immunoblot analysis

Total protein lysates were prepared as described (36). Proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted with antibodies to Chkα, TRAF3 and actin. Immunoblot analysis was performed as previously described (8, 30). Images of immunoblots were acquired using a low-light imaging system (LAS-4000 mini, FUJIFILM Medical Systems USA, Inc., Stamford, CT) (8, 30).

MTT assay

Mouse B lymphoma cell lines (1 × 105 cells/well) and human MM or B lymphoma cell lines (3 × 104 cells/well) were plated in 96-well plates in the absence or presence of serial dilutions of Chkα inhibitors. At the indicated time point after treatment, cell viability and proliferation were measured using the MTT (3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide) assay as described (41). Possible influences caused by direct MTT-inhibitor interactions were excluded by studies in a cell-free system.

Transduction of human MM cells with a lentiviral TRAF3 expression vector

The full-length coding cDNA sequence of human TRAF3 was cloned from the 293T cell line using reverse transcription PCR. Primers used for the cloning of human TRAF3 are hTRAF3-F (5’- CCT AAA ATG GAG TCG AGT AAA AAG-3’) and hTRAF3-R (5’- TTA TCA GGG ATC GGG CAG A-3’). The TRAF3 cDNA was subcloned into the lentiviral expression vector pUB-eGFP-Thy1.1 (42) (generously provided by Dr. Zhibin Chen, the University of Miami, Miami, FL) by replacing the eGFP coding sequence with the TRAF3 coding sequence. The resultant pUB-TRAF3-Thy1.1 lentiviral vector was verified by DNA sequencing. Lentiviruses of pUB-TRAF3-Thy1.1 and an empty vector pUB-Thy1.1 were packaged and lentiviral titers were determined as previously described (30, 43). Human MM 8226 cells were transduced with the packaged lentiviruses at an MOI of 1:5 (cell:virus) in the presence of 8 μg/mL polybrene (30, 43). Transduction efficiency of cells was analyzed at day 3 post transduction using Thy1.1 immunofluorescence staining followed by flow cytometry. Transduced cells were subsequently analyzed for cell cycle distribution, Chkα expression, and choline metabolism. For cell cycle analysis, transduced cells were fixed at day 4 or day 7 post-transduction with ice-cold 70% ethanol. Cell cycle distribution was subsequently determined by propidium iodide (PI) staining followed by flow cytometry as previously described (4, 44).

In vivo administration of MN58B and RMS932A

Gender-matched, young adult LMC and B-Traf3−/− mice were injected intraperitoneally (i.p.) with a Chkα inhibitor MN58B or RSM932A at 2 mg/kg/mouse, or vehicle control, three times a week for 4 weeks. Mouse spleen size was subsequently determined and splenic B cell populations were analyzed by flow cytometry.

Flow cytometry

Single cell suspensions were made from mouse spleens. Immunofluorescence staining and FACS analyses were performed as previously described (4, 8). Erythrocytes from spleens were depleted with ACK lysis buffer. Cells (1 × 106) were blocked with rat serum and FcR blocking Ab (2.4G2), and incubated with various Abs conjugated to FITC, PE, PerCP, or APC for multiple color fluorescence surface staining. Analyses of cell surface markers included antibodies to CD45R (B220), CD3, CD21 and CD23 (BioLegend, San Diego, CA). Listmode data were acquired on a FACSCalibur (Becton Dickinson, Mountain View, CA). The results were analyzed using the FlowJo software (TreeStar, San Carlos, CA).

Statistics

Statistical analyses were performed using Prism software (GraphPad, La Jolla, CA). For direct comparison of the levels of polar metabolites, lipids or transcripts between LMC and Traf3−/− B cells, statistical significance was determined with the unpaired t test for two-tailed data. P values less than 0.05 are considered significant, P values less than 0.01 are considered very significant, and P values less than 0.001 are considered highly significant.

Results

TRAF3-mediated regulation of polar metabolites

To explore the metabolic basis of the prolonged survival of Traf3−/− B cells, we performed a metabolomic screening by LC-MS. We compared the steady-state levels of water-soluble polar metabolites in littermate control (LMC) and Traf3−/− splenic B cells purified from gender-matched young adult (8–12-week-old) mice by magnetic sorting, either directly ex vivo or after culture for 1 day. Comparison of direct ex vivo B cells revealed the metabolic differences between the two genotypes in the presence of endogenous B cell survival factor BAFF, while comparison of post-culture B cells allowed us to identify the metabolic changes of the two genotypes in response to in vitro culture in the absence of BAFF. Our results showed that 16 metabolites were significantly up-regulated in Traf3−/− B cells (Supplementary Fig. 1A and 1B). We have analyzed splenic B cells derived from 3 female and 3 male mice of each genotype and did not detect significant gender difference in the effects of TRAF3 ablation on polar metabolites. Both female and male Traf3−/− B cells exhibited consistent elevation of these 16 metabolites.

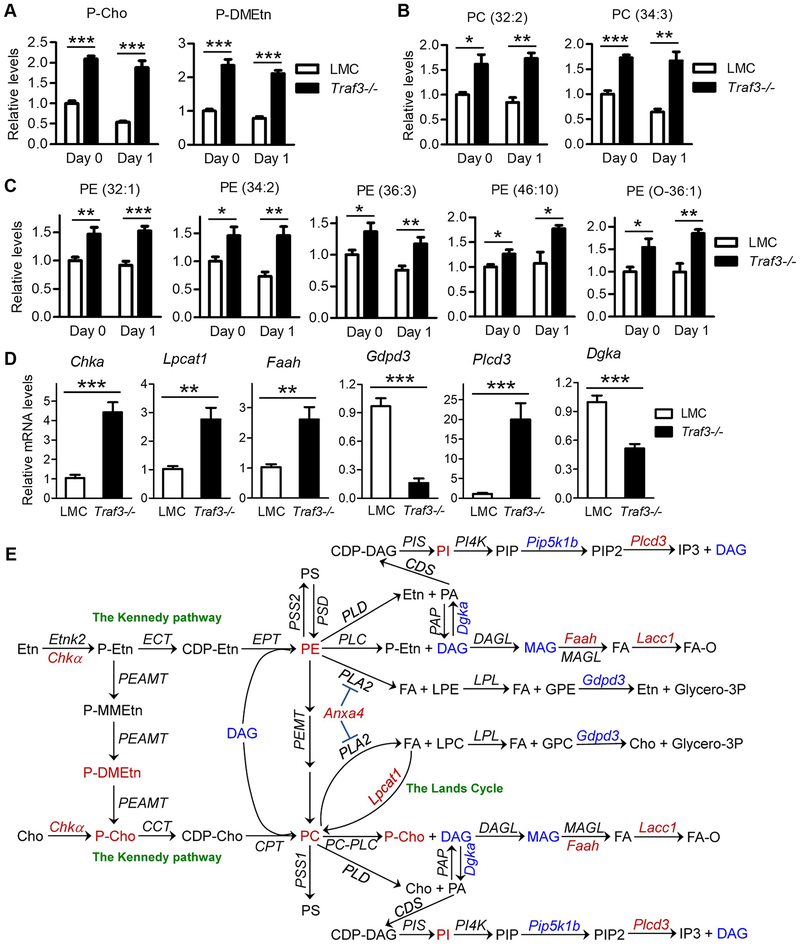

Interestingly, we found that phosphocholine (P-Cho) and phosphodimethylethanolamine (P-DMEtn), 2 precursors of phospholipids, were significantly increased in Traf3−/− B cells both directly ex vivo (day 0) and at day 1 after culture (Fig. 1A). Five glucose metabolic intermediates were also significantly up-regulated in Traf3−/− B cells, including glucose-6-phosphate (G6P), dihydroxyacetone phosphate (DHAP), glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate (GA3P), ribose-5-phosphate (Ribose-5-P), and sedoheptoluse-7-phosphate (S7P) (Supplementary Fig. 1C). Surprisingly, although G6P is the convergence point of the glycolytic and pentose phosphate pathways (PPP) (45), we only detected an increase in metabolites of the nonoxidative PPP. In contrast, metabolites of the aerobic glycolysis (such as 3-phosphoglyceric acid [3PG], pyruvate [PYR] and lactate), the TCA cycle (such as citrate, α-ketoglutarate and malate), and the oxidative PPP (such as 6-phosphogluconolactone [6PGL], 6-phosphogluconic acid [6PG] and NADPH) were not significantly different between Traf3−/− and LMC B cells (Supplementary Fig. 1C). It is possible that some changes in metabolites may have been missed in our metabolomic study, especially given the evidence that some metabolites are unstable during the LC-MS run time (46, 47). However, it is notable that the primary role of the nonoxidative PPP is to generate Ribose-5-P, the molecular backbone of ribonucleotide biosynthesis (45, 48–50). Consistent with this notion, we detected an increase of 9 ribonucleotides in Traf3−/− B cells, including UMP, CMP, GMP, AMP, CDP, UDP, GDP, ADP and inosine (Supplementary Fig. 1C). It is intriguing that no significant differences were observed in the concentrations of the ribonucleotide triphosphates (Supplementary Fig. 1C). Based on the adenylate energy charge (AEC) index (51), LMC B cells had an increased AEC at day 1 after culture due to drastically decreased AMP concentrations (Supplementary Fig. 1D). This increased AEC might predispose LMC B cells to apoptosis as a similar increase of AEC was observed in cerebellar granule cells en route to apoptosis (52). We also directly measured ATP concentrations in splenic B cells using an ATP Determination kit. Our results showed that ATP concentrations were slightly lower in LMC B cells than in Traf3−/− B cells at day 1 after culture, but this difference is not statistically significant (Supplementary Fig. 1D). Taken together, our results of polar metabolites indicate that TRAF3 regulates the choline metabolism, nonoxidative PPP and ribonucleotide metabolic pathways in B cells.

Figure 1. TRAF3 inhibited PC and PE metabolic pathways in B cells.

Splenic B cells were purified from gender-matched, young adult (8–12-week-old) LMC or B-Traf3−/− mice. Water-soluble polar metabolites (A) or lipids (B and C) were extracted from cells directly ex vivo (day 0) or after cultured in vitro in mouse B cell medium for 1 day, and then analyzed by LC-MS as described in Methods. (A) Increased levels of P-Cho and P-DMEtn in Traf3−/− B cells. (B and C) Elevated levels of PC and PE species in Traf3−/− B cells. (D) Verification of transcript regulation of selected metabolic enzymes identified by the microarray analysis. Total cellular RNA was prepared from purified splenic B cells and cDNA was synthesized by reverse transcription. Quantitative real-time PCR was performed using TaqMan assay kits specific for mouse Chka, Lpcat1, Faah, Gdpd3, Plcd3 or Dgka. Relative mRNA levels were analyzed using the ΔΔCt method and normalized using b-actin mRNA as an endogenous control. Results shown in (A-D) are mean ± SD (n=6, including 3 female and 3 male samples for each genotype). *, significantly different (t test, p < 0.05); **, very significantly different (t test, p < 0.01); ***, highly significantly different (t test, p < 0.001) between LMC and Traf3−/− B cells. (E) Pathway schematics showing TRAF3-mediated regulation of the interconnected PC and PE metabolism in B cells. Enzymes are denoted in Italic font in the schematics. Metabolites, lipids and metabolic enzymes that were regulated by TRAF3 are indicated in red (for those up-regulated in Traf3−/− B cells) or blue (for those down-regulated in Traf3−/− B cells).

Regulation of lipid metabolism by TRAF3

In light of the observed up-regulation of 2 precursors of phospholipids and the known pivotal importance of phospholipids in maintaining cell survival (53, 54), we sought to identify lipids and phospholipids that are regulated by TRAF3 in B cells. We performed an LC-MS-based lipidomic screening to compare the steady-state levels of lipids between LMC and Traf3−/− splenic B cells purified from gender-matched young adult mice. We detected 169 lipid species, among which 11 lipids were significantly elevated and 8 lipids were significantly decreased in Traf3−/− B cells as compared to LMC B cells (Supplementary Fig. 2A and 2B). Interestingly, 2 phosphatidylcholine (PC) species (32:2 and 34:3) and 5 phosphatidylethanolamine (PE) species (32:1, 34:2, 36:3, 46:10, and O-36:1) were markedly elevated in Traf3−/− B cells both directly ex vivo and at day 1 after culture (Fig. 1B and 1C). Three phosphatidylinositol (PI) species (36:4, 38:4, and 38:5) and one galactosylceramide (Gal-Cer 18:3) were increased in Traf3−/− B cells only at day 1 after culture but not directly ex vivo (Supplementary Fig. 2C). In contrast, 4 diacylglycerol (DAG) species (DAG_NH4 34:0, 36:0, 38:0, and 40:1) and 2 monoacylglycerol (MAG) species (MAG_Na 16:0 and 18:0) were significantly decreased in Traf3−/− B cells at day 0 but not at day 1 after culture, while two ceramides (d18:1/26:4 and d18:1/26:5) were moderately decreased in Traf3−/− B cells only at day 1 after culture (Supplementary Fig. 2C). Given the prolonged survival phenotype of Traf3−/− B cells both in vivo in mice and in vitro in culture (4, 5), the consistent elevation of the 2 PC species and 5 PE species in Traf3−/− B cells both directly ex vivo and at day 1 after culture highlights the potential importance of these phospholipids in Traf3−/− B cell survival.

Metabolic enzymes regulated by TRAF3

To understand how TRAF3 regulates cellular metabolism in B cells, we set out to identify metabolic enzymes regulated by TRAF3. We performed a transcriptome profiling using LMC and Traf3−/− splenic B cells purified from gender-matched young adult mice. We identified 101 genes differentially expressed between LMC and Traf3−/− splenic B cells, including 65 up-regulated genes and 36 down-regulated genes in Traf3−/− B cells (cut-off fold of changes: 2-fold up or down, p < 0.05) (NCBI GEO accession number: GSE113920) (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/). Functional clustering and signaling pathway analyses by Ingenuity (http://www.ingenuity.com) revealed that 17 metabolic enzymes were up- or down-regulated at least 2-fold in Traf3−/− B cells (Supplementary Fig. 3A). These include 8 enzymes involved in choline and phospholipid metabolism, 4 enzymes in nucleotide and DNA metabolism, 3 enzymes in glycolysis and glycosylation, and 2 enzymes in amino acid metabolism (Supplementary Fig. 3B). Moreover, we detected additional 29 metabolic enzymes that were up- or down-regulated 1.5 to 2-fold in Traf3−/− B cells (p < 0.05; Supplementary Fig. 3C and 3D). By integrating information across our metabolomic, lipidomic and transcriptomic datasets, we identified a major clustering of TRAF3-mediated regulation of B cell metabolism in the interconnected choline and ethanolamine metabolic pathways (Fig. 1E).

We prioritized the metabolic enzymes identified by the microarray analysis according to their potential importance in the choline and ethanolamine metabolic pathways. We selected 6 enzyme-encoding genes altered in Traf3−/− B cells for further verification by quantitative real time PCR (qRT-PCR). Our results verified the transcript changes of the examined enzyme genes in Traf3−/− B cells (Fig. 1D). Most relevant to the up-regulation of PC and PE was increased Chka (choline kinase) and Lpcat1 (lysophosphatdiylcholine acyltransferease) as well as decreased Gdpd3 (glycerophosphodiester phosphodiesterase). The decreased DAG and MAG may relate to lower Dgka (diacylglycerol kinase) and up-regulated Faah (fatty acid amide hydrolase) (Fig 1D and 1E). These results suggest that TRAF3 regulates the expression of metabolic enzymes in B cells to control PC and PE metabolism.

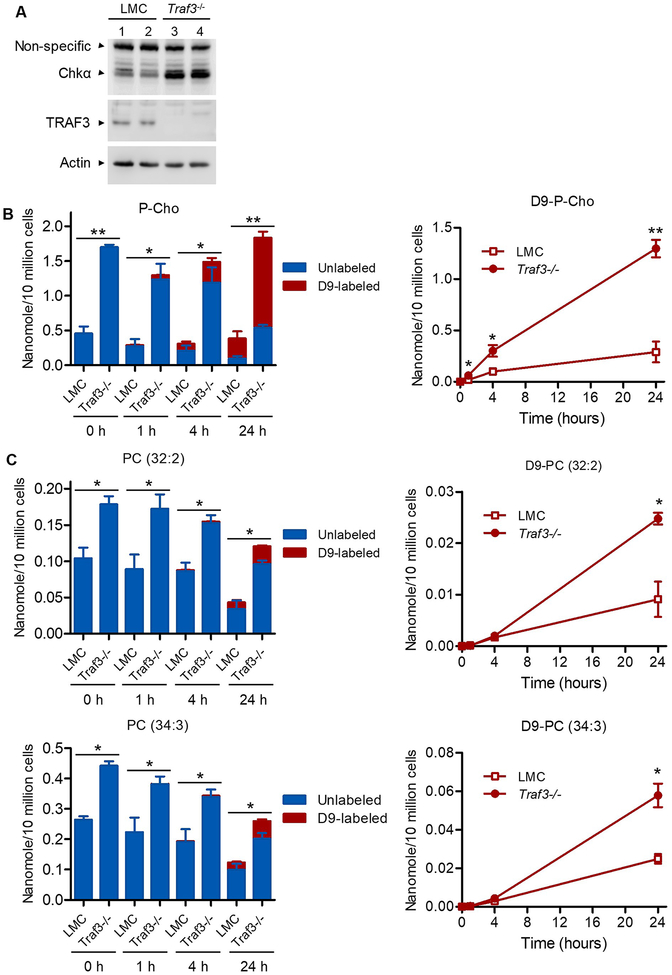

TRAF3-mediated regulation of the Kennedy pathway of the P-Cho-PC synthesis

The two major pathways of the phospholipid PC synthesis are de novo biosynthesis (also termed the Kennedy pathway) and sequential methylation of PE (Fig. 1E) (54–56). Chkα, also called ethanolamine kinase (EtnK), is the first enzyme of the Kennedy pathway. It directly phosphorylates both choline (Cho) and ethanolamine (Etn) with higher activity on choline (Fig. 1E) (54–56). Here we demonstrated that Chkα was remarkably enhanced at the protein level in Traf3−/− splenic B cells by Western blot analysis (Fig. 2A). Chkα overexpression is thought to be responsible for the elevated P-Cho and PC phenotype in most cases of human breast, lung and prostate cancers (55, 57). We likewise detected significantly elevated levels of P-Cho and PC in premalignant Traf3−/− B cells (Fig. 1A and Fig. 1B). In this context, we next performed stable isotope labeling to determine if the increased P-Cho is generated from de novo synthesis or from catabolism of choline-containing metabolites and if the Kennedy pathway contributes to the elevation of PC species. We cultured LMC and Traf3−/− splenic B cells purified from gender-matched young adult mice in mouse B cell medium containing the stable isotope tracer trimethyl-D9-choline ([2H]9-Cho) (58). We subsequently analyzed the labeled and unlabeled polar metabolites of cultured cells at different time points using LC-MS. We found that Traf3−/− splenic B cells exhibited significantly increased incorporation of the stable isotope tracer D9-choline into P-Cho (Fig. 2B). We also compared the labeled and unlabeled lipids of the cells at different time points using LC-MS (58). We detected a significantly higher levels of D9-choline-labeled PC species (32:2 and 34:3) in Traf3−/− B cells than in LMC B cells at 24 h after culture (Fig. 2C). Collectively, these stable isotope labeling data indicate that the biosynthesis of P-Cho-PC is elevated in Traf3−/− B cells.

Figure 2. Elevated Chkα and choline metabolism in Traf3−/− B cells.

Splenic B cells were purified from gender-matched, young adult LMC and B-Traf3−/− mice. (A) Up-regulation of Chkα protein in Traf3−/− B cells analyzed by Western blot analysis. Total cellular proteins were prepared from purified splenic B cells, separated by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted for Chkα, followed by TRAF3 and β-actin. Results shown are representative of three independent experiments. (B and C) Analysis of choline metabolism by stable isotope labeling. Purified splenic B cells were cultured in mouse B cell medium containing 80 μg/mL of trimethyl-D9-choline ([2H]9-Cho) for the indicated time periods. The D9-labeled and unlabeled water-soluble metabolites (B) and lipids (C) of cultured splenic B cells were subsequently analyzed using LC-MS. (B) Increased incorporation of D9-choline into P-Cho in Traf3−/− B cells. (C) Elevated incorporation of D9-choline into PC species in Traf3−/− B cells. The composition of the D9-labeled and unlabeled P-Cho or PC species of each sample is shown in the bar graphs (left panel), and the kinetic increase of the D9-labeled P-Cho or PC species of each genotype of cells is shown in the curves (right panel). *, significantly different (t test, p < 0.05); **, very significantly different (t test, p < 0.01); ***, highly significantly different (t test, p < 0.001) between LMC and Traf3−/− B cells.

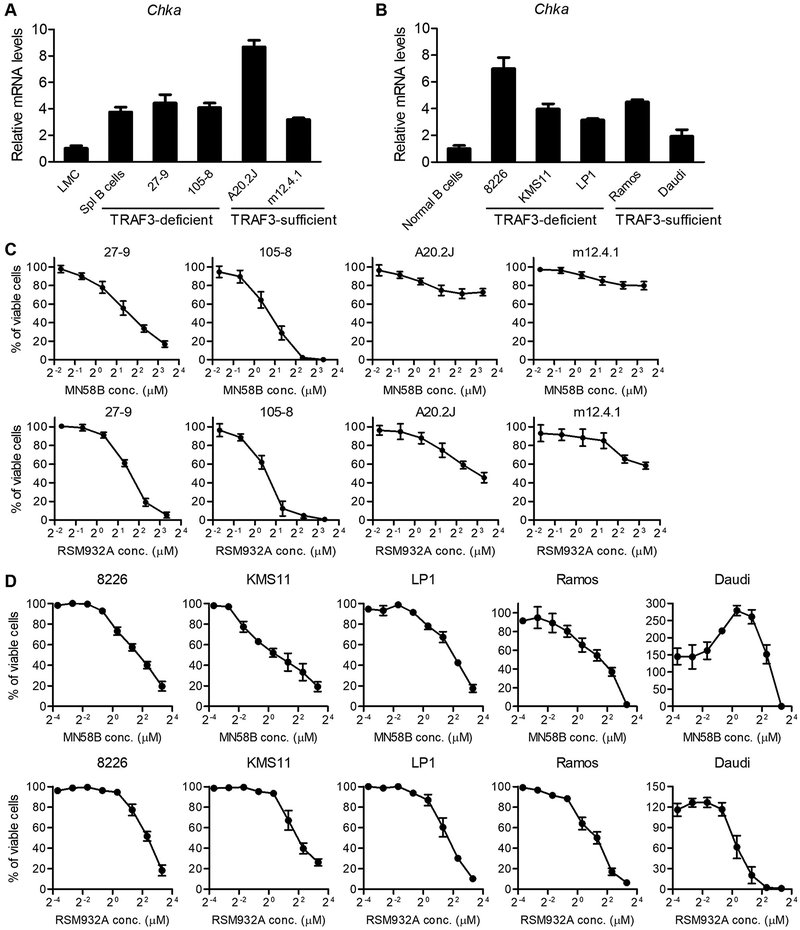

Chkα inhibitors suppressed the survival of TRAF3-deficient B cells in culture

We next asked if Chka expression is consistently up-regulated in TRAF3-deficient malignant B cells and if elevated Chkα-mediated choline metabolism is important for oncogenic B cell survival. To address this, we analyzed Chka expression levels in two Traf3−/− mouse B lymphoma cell lines 27–9 and 105–8 that were previously derived from aging B-Traf3−/− mice (8, 30). Our results showed that up-regulation of Chka expression was maintained in these two Traf3−/− mouse B lymphoma cell lines at a similarly high level as that detected in premalignant Traf3−/− splenic B cells (Fig. 3A). To investigate the functional importance of elevated choline metabolism, we tested the effects of two pharmacological inhibitors of Chkα, MN58B (IC50: 1.4 μM) and RSM932A (IC50: 1 μM) (59–61), on the survival of these Traf3−/− mouse B lymphoma cells. Our results obtained by MTT assay demonstrated that both MN58B and RSM932A potently inhibited the survival and proliferation of TRAF3-deficient mouse B lymphoma cell lines 27–9 and 105–8 cells in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 3C). These results suggest that TRAF3 inactivation-induced Chka upregulation is important for the survival of cultured TRAF3-deficient mouse B lymphoma cells.

Figure 3. Chkα inhibitors MN58B and RSM932A suppressed the survival of TRAF3-deficient mouse and human malignant B cells in culture.

(A) Up-regulation of Chka expression in TRAF3-deficient mouse B lymphoma cell lines 27–9 and 105–8 as well as TRAF3-sufficient mouse B lymphoma cell lines A20.2J and m12.4.1. (B) Up-regulation of Chka expression in TRAF3-deficient human MM cell lines 8226, KMS11 and LP1 as well as TRAF3-sufficient human Burkitt’s lymphoma cell lines Ramos and Daudi. Chka expression was determined by qRT-PCR using Taqman assays specific for mouse (A) and human (B) Chka, respectively, and results shown are mean ± SD (n=4). (C) Mouse B lymphoma cell lines 27–9, 105–8, A20.2J and m12.4.1 cells were treated with various concentrations (1:2 serial dilutions) of MN58B or RSM932A for 24 h. (D) Human MM or Burkitt’s lymphoma cell lines 8226, KMS11, LP1, Ramos and Daudi cells were treated with various concentrations (1:2 serial dilutions) of MN58B or RSM932A for 72 h. Total viable cell numbers were subsequently determined by MTT assay. Viable cell curves shown (C and D) are the results of at least three independent experiments with duplicate samples in each experiment (mean ± SEM).

To strengthen the clinical relevance of our findings obtained from TRAF3-deficient mouse B cells, we next examined the expression of CHKA in three patient-derived MM cell lines that contain bi-allelic deletions or inactivating mutations of TRAF3, including 8226, KMS11 and LP1 (6). Our results revealed that the expression of CHKA was up-regulated in all the three TRAF3-deficient human MM cell lines to a varied extent (3–7 fold as compared to normal B cells) (Fig. 3B), suggesting that TRAF3 inactivation also up-regulates CHKA expression in human B cells. Of particular interest, the two CHKα inhibitors MN58B and RSM932A also suppressed the survival and proliferation of all these TRAF3-deficient human MM cell lines in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 3D). Thus, elevated Chkα-mediated choline metabolism appears to play an indispensable and causal role in the survival phenotype of both mouse and human TRAF3-deficient malignant B cells in culture.

To determine if elevation of Chkα-mediated choline metabolism is ubiquitously critical for malignant B cell survival, we also examined several TRAF3-sufficient B cell lines for comparison. We found that Chka expression was ubiquitously up-regulated (approximately 2–9-fold increase as compared to normal B cells) in all the TRAF3-sufficient B cell lines examined, including the mouse B lymphoma cell lines A20.2J and m12.4.1 as well as human Burkitt’s lymphoma cell lines Ramos and Daudi (Fig. 3A and 3B). Thus, Chka expression may be up-regulated in malignant B cells via either TRAF3 inactivation-dependent or TRAF3-independent pathways. Interestingly however, inhibition of Chkα by MN58B was not effective and RSM932A had minimal effects on suppressing the survival and proliferation of TRAF3-sufficient mouse B lymphoma cell lines A20.2J and m12.4.1 cells (Fig. 3C). In contrast, both MN58B and RSM932A were effective in inhibiting the survival and proliferation of TRAF3-sufficient human Burkitt’s lymphoma cell line Ramos cells. Furthermore, it is perplexing that MN58B failed to inhibit the survival and proliferation of another Burkitt’s lymphoma cell line Daudi, although this cell line was susceptible to RSM932A treatment (Fig. 3D). Taken together, the responses of different TRAF3-sufficient malignant B cell lines to the Chkα inhibitors varied considerably from cell line to cell line, which likely reflect the differences in their oncogenic mutation landscapes and the presence or absence of redundant Chkα-independent choline metabolic pathways.

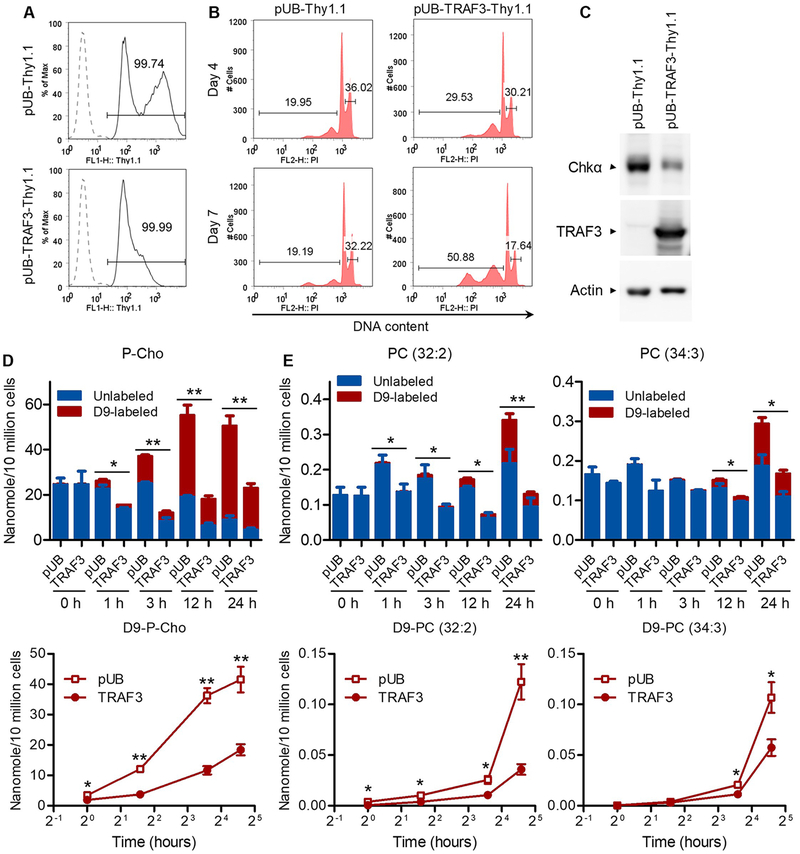

Reconstitution of TRAF3 inhibits the Kennedy pathway of the P-Cho-PC biosynthesis in human MM cells

To further verify that TRAF3 regulates Chkα-mediated choline metabolism in human B cells, we selected a patient-derived MM cell line 8226 that contains bi-allelic deletions of the TRAF3 gene to conduct TRAF3 reconstitution experiments (6). We transduced 8226 cells using a lentiviral expression vector, pUB-TRAF3-Thy1.1, to reconstitute the expression of TRAF3 proteins. Cells transduced with an empty lentiviral vector, pUB-Thy1.1, were used as a negative control in these experiments. Transduction efficiency of the lentiviral vectors was over 99% in human MM 8226 cells, as demonstrated by FACS analysis (Fig. 4A). Reconstitution of TRAF3 expression induced cellular apoptosis in approximately 50% of the transduced 8226 cells at day 7 post transduction as revealed by cell cycle analysis (Fig. 4B). Interestingly, reconstitution of TRAF3 expression markedly decreased the protein levels of CHKα in the transduced 8226 cells at day 3 post transduction as shown by Western blot analysis (Fig. 4C).

Figure 4. Reconstitution of TRAF3 expression inhibited the P-Cho-PC biosynthesis in human MM cells.

The human MM cell line 8226 cells were transduced with a lentiviral expression vector of TRAF3 (pUB-TRAF3-Thy1.1) or an empty lentiviral expression vector (pUB-Thy1.1). (A) Transduction efficiency. Transduced 8226 cells were analyzed by Thy1.1 staining and flow cytometry at day 3 post transduction. Dashed profiles show the untransduced cells (a negative control of the Thy1.1 staining), and gated populations (Thy1.1+) indicate cells that were successfully transduced with the lentiviral expression vector. (B) Representative FACS histograms of cell cycle analysis. Cell cycle distribution of transduced 8226 cells was analyzed by PI staining and flow cytometry at day 4 and day 7 post transduction. Gated populations indicate apoptotic cells (sub-G0: DNA content < 2n) and proliferating cells (S/G2/M phase: 2n < DNA content ≤ 4n). (C) Expression of Chkα and TRAF3 determined by Western blot analysis. Total cellular proteins were prepared at day 3 post transduction, and then immunoblotted for Chkα, TRAF3 and actin. (D and E) Analysis of choline metabolism by stable isotope labeling. At day 3 post transduction, transduced 8226 cells were cultured in human B cell medium containing 80 μg/mL of trimethyl-D9-choline. D9-labeled and unlabeled P-Cho (D) and PC species (E) were analyzed at the indicated time points by LC-MS. (D) Decreased incorporation of D9-choline into P-Cho in pUB-TRAF3-Thy1.1 (TRAF3)-transduced 8226 cells. (E) Reduced incorporation of D9-choline into two PC species in TRAF3-transduced 8226 cells. The composition of the D9-labeled and unlabeled P-Cho or PC species of each sample is shown in the bar graphs (top panel), and the kinetic increase of the D9-labeled P-Cho or PC species of each transduce cell type is shown in the curves (bottom panel). Results shown are mean ± SEM (n=3). *, significantly different (t test, p < 0.05); **, very significantly different (t test, p < 0.01) between TRAF3-transduced and the control vector pUB-transduced cells.

We next performed stable isotope labeling to assess if reconstitution of TRAF3 expression inhibits the Kennedy pathway of P-Cho-PC biosynthesis. We cultured the transduced 8226 cells in human B cell medium containing the stable isotope tracer trimethyl-D9-choline at day 3 post transduction. We subsequently analyzed the labeled and unlabeled polar metabolites as well as phospholipids at different time points using LC-MS. Similar to that observed in mouse splenic B cells, reconstitution of TRAF3 expression significantly decreased the pool size of P‐Cho and two downstream phospholipid PC species (32:2 and 34:3). This was associated with slower production of labeled P-Cho and PC lipids (32:2 and 34:3) from the D9‐labeled choline tracer (Fig. 4D and 4E). We noticed that the labeling fractions of both P-Cho and the two PC species did not significantly change between TRAF3-transduced and the control vector-transduced cells, suggesting that the same metabolic pathways are being used in both cases. Therefore, the differences that we detected in the pool size of P-Cho and the two PC species were due to different production rates of these molecules between TRAF3-transduced and the control vector-transduced cells. Together, our results demonstrate that reconstitution of TRAF3 inhibited Chkα expression and the Kennedy pathway of P-Cho-PC biosynthesis, and also induced apoptosis in transduced human MM 8226 cells.

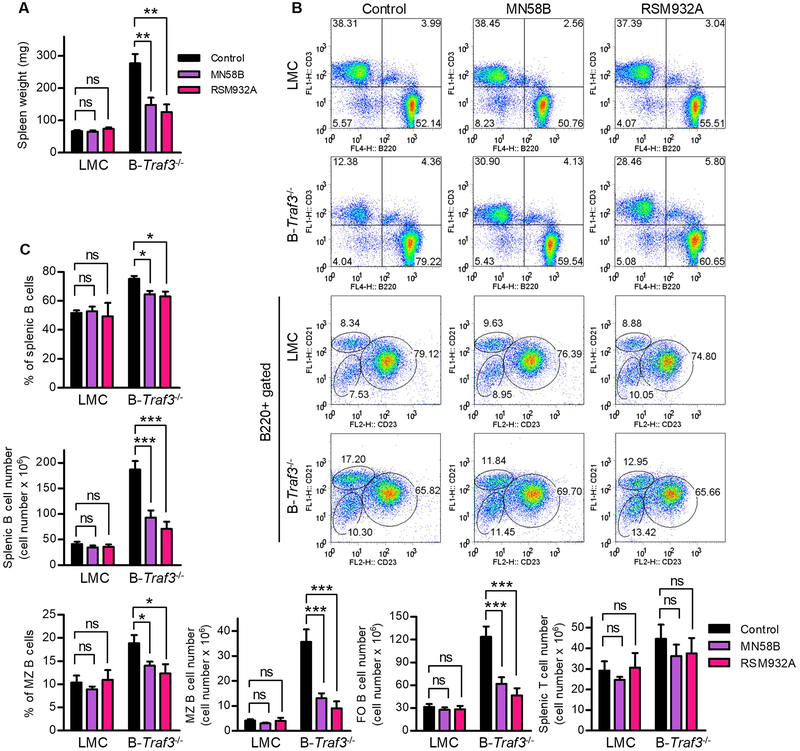

Pharmacological inhibitors of Chkα reversed the phenotype of the B cell compartment in B-Traf3−/− mice

Our in vitro data regarding the roles of TRAF3 in Chkα-mediated choline metabolism in human MM cells (Fig. 4) and the effects of Chkα inhibitors on the survival of TRAF3-deficient mouse B lymphoma and human MM cells (Fig. 3) prompted us to further evaluate the in vivo effects of these inhibitors on the B cell hyperplasia phenotype in B-Traf3−/− mice. We administered MN58B or RSM932A to gender-matched, young adult LMC and B-Traf3−/− mice via i.p. injection at 2 mg/kg/mouse three times a week for 4 weeks, and then analyzed the spleen size and splenic B cell compartment of the treated mice. Our results demonstrated that in vivo administration of either MN58B or RSM932A substantially decreased the spleen size as measured by spleen weight in B-Traf3−/− mice but not in LMC mice (Fig. 5A). Flow cytometric analysis revealed that treatment with MN58B or RSM932A partially reduced the percentage and drastically decreased the numbers of splenic B cells in B-Traf3−/− mice but not in LMC mice (Fig. 5B and 5C). Furthermore, treatment with MN58B or RSM932A remarkably decreased the percentage and numbers of the splenic marginal zone (MZ) B cell subset and also dramatically reduced the numbers of the follicular (FO) B cell subset in B-Traf3−/− mice, which was not observed in LMC mice (Fig. 5B and 5C). In contrast, MN58B or RSM932A did not significantly affect splenic T cell numbers in B-Traf3−/− or LMC mice (Fig. 5C). In summary, administration of pharmacological inhibitors of Chkα substantially reversed the B cell hyperplasia phenotype observed in B-Traf3−/− mice, suggesting that elevated Chkα-mediated phosphocholine and PC biosynthesis contributes to the prolonged survival of Traf3−/− B cells in vivo.

Figure 5. Chkα inhibitors MN58B and RSM932A substantially reversed the B cell hyperplasia phenotype in B-Traf3−/− mice.

Gender-matched, young adult LMC and B-Traf3−/− mice were administered i.p. with a Chkα inhibitor MN58B or RSM932A at 2 mg/kg/mouse, or vehicle control, three times a week for 4 weeks. Spleen size and B cell compartment were analyzed at 2 days after the last injection. (A) Chkα inhibitors reduced the spleen weights of B-Traf3−/− mice. (B) Representative FACS profiles of mouse splenocytes. B cells and T cells were identified by B220 and CD3 staining, respectively. Splenic B cell subsets were further differentiated by the markers CD21 and CD23. MZ B cell subset was identified as B220+CD21+CD23low, and FO B cell subset was identified as B220+CD21intCD23+. (C) The percentages and numbers of splenic B cells, B cell subsets and T cells analyzed by FACS. Effects of MN58B or RSM932A treatment were compared to the vehicle control group for each genotype. Results shown are mean ± SD (n=6, including 3 female and 3 male samples for each genotype). *, significantly different (t test, p < 0.05); **, very significantly different (t test, p < 0.01); ***, highly significantly different (t test, p < 0.001); ns, not significantly different (t test, p ≥ 0.05) between MN58B or RSM932A treated and the vehicle control group.

Discussion

Targeted therapies are currently the focus of anticancer research and are the core concept of precision medicine. Interestingly, targeting cancer metabolism has recently emerged as a promising strategy for the development of selective and effective anticancer drugs (62). Defining metabolic pathways regulated by critical oncogenes and tumor suppressor genes is required for such therapeutic exploitation. In the present study, we elucidated the metabolic pathways regulated by a new tumor suppressor, TRAF3, in B lymphocytes using metabolomic, lipidomic and transcriptomic analyses. We found that multiple polar metabolites, lipids and enzymes regulated by TRAF3 in B cells are clustered in the P-Cho, PC and PE biosynthesis pathways (Fig. 1E).

Aberrant choline metabolism has been recognized as a cancer hallmark associated with oncogenesis, invasion and metastasis as well as responsiveness to therapy in human cancers (55, 57). The metabolic pathways of PC and PE are closely interconnected, and moderate perturbations of PC and PE metabolism have profound effects on cell viability and apoptosis (63). Consistent with these previous findings, our results showed that premalignant Traf3−/− B cells contained markedly elevated levels of P-Cho, P-DMEtn, PC and PE as well as Chkα, the first enzyme of de novo PC and PE biosynthesis (the Kennedy pathway). Interestingly, Chka expression was ubiquitously up-regulated in a variety of TRAF3-deficient as well as TRAF3-sufficient malignant B cell lines examined in the present study, including mouse B lymphoma cell lines, human MM and Burkitt’s lymphoma cell lines. We also surveyed the public gene expression databases of human cancers at Oncomine (http://www.oncomine.org) and learned that the expression of CHKA is significantly increased in human DLBCLs (64–66). Overexpression of Chkα has been shown to cause an elevated P-Cho and PC phenotype and thus has been identified as a therapeutic target in breast, lung and prostate cancers as well as T-cell lymphoma and leukemia (55, 57, 67, 68). In this study, our stable isotope labelling experiments demonstrated increased biosynthesis of P-Cho and PC in Traf3−/− mouse B cells as well as decreased biosynthesis of P-Cho and PC in TRAF3-reconstituted human MM cells. Interestingly, pharmacological inhibition of Chkα reversed the survival phenotype of TRAF3-deficient B cells both in vitro and in vivo. Taken together, our findings indicate that elevated Chkα-mediated choline metabolism supports the aberrantly prolonged survival of Traf3−/− B cells. Therefore, our study established a novel connection between the tumor suppressor TRAF3 and the known oncogenic Chkα-P-Cho-PC metabolic pathway in premalignant and malignant B cells.

PC and PE are the most abundant phospholipids in cell membranes, and play a dual role as structural components and as substrates for lipid second messengers such as phosphatidic acid (PA) and diacylglycerol (DAG) (69). We detected significantly increased levels of multiple species of PC and PE but decreased levels of their catabolic products such as DAG and MAG in Traf3−/− B cells. In addition to Chkα, we also discovered TRAF3-mediated regulation of several other enzymes that catalyze the anabolic or catabolic pathways of phospholipids in B cells, including Lpcat1, Faah, Gdpd3, Plcd3, Dgka, Lacc1 and Pip5k1b. Among these, up-regulation of LPCAT1 and FAAH as well as down-regulation of DGKA and PIP5K1B has been documented in human cancers (70–75). In particular, the key enzyme of an alternative pathway of PC synthesis, LPCAT1 of the Lands Cycle that converts lysophosphatidyl-choline (LPC) to PC, has been shown to play important roles in cancer pathogenesis and progression (70–72). Interestingly, Anxa4, a gene robustly up-regulated in Traf3−/− B cells, has been recognized as an inhibitor of phospholipase A2 (PLA2) (76), the catabolic enzyme of the Lands Cycle that mediates the breakdown of PC and PE (Fig. 1E). Thus, simultaneous up-regulation of both Lpcat1 and Anxa4 would likely promote the synthesis of PC and inhibit the breakdown of PC and PE, which may also contribute to the increased PC and PE levels detected in Traf3−/− B cells. Collectively, our results revealed the complex interactions between TRAF3 and phospholipid metabolic pathways associated with survival regulation in B cells.

We noticed that another major effect of TRAF3 on B cell metabolism was clustered in the nonoxidative-PPP and ribonucleotide metabolic pathways (Supplementary Fig. 4). In line with the increased levels of G6P, nonoxidative PPP metabolites and ribonucleotides, we detected up-regulation of the key enzyme of glycogen breakdown Pygl and two enzymes of ribonucleotide biosynthesis (Mthfd1 and Adssl1) as well as down-regulation of two enzymes involved in ribonucleotide catabolism (Upb1 and Pde2a) in Traf3−/− B cells. Relevant to our observation, Mambetsariev et al. reported that a glucose transporter (Glut1) and an enzyme hexokinase II (HKII) that converts glucose to G6P are up-regulated in Traf3−/− B cells (77), although not detected in our microarray analysis. Therefore, both elevated glycogen breakdown and increased glucose uptake and conversion may lead to increased nonoxidative-PPP metabolism in Traf3−/− B cells. Corroborating our finding, MTHFD1, an enzyme of one-carbon metabolism that is essential for de novo purine biosynthesis, is up-regulated in a variety of human B cell malignancies, including DLBCL, follicular Lymphoma (FL), B cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (B-ALL), B-CLL, BL, HL and MM (Oncomine) (65, 66, 78, 79). A common polymorphism of MTHFD1 R653Q (c.1958 G > A) in the synthetase domain impairs purine synthesis and the AA genotype of MTHFD1 G1958A is associated with a decreased risk of B-ALL and NHL (80, 81). It is thus likely that the increased nonoxidative-PPP metabolism and ribonucleotide biosynthesis may also contribute to the prolonged survival of Traf3−/− B cells.

In summary, our study has contributed to a better understanding of the metabolic mechanisms underlying aberrant survival of B lymphocytes induced by inactivation of the tumor suppressor TRAF3. We demonstrated that elevated choline metabolism via the Chkα-driven de novo Kennedy pathway plays an important causal role in the survival phenotype of Traf3−/− B cells. Our findings support that the Chkα-P-Cho-PC metabolic pathway has diagnostic and therapeutic value for B cell malignancies. For example, changes in P-Cho cellular levels can be non-invasively monitored in patients by in vivo imaging using choline analog tracers [18F]-choline or [11C]-choline in positron emission tomography/computed tomography (PET/CT) (82). Our study supports the use of such choline metabolism-based approach for early detection of B cell malignancies and for the assessment of malignant B cell responses to therapy. Furthermore, inhibition of choline metabolism by Chkα inhibitors or other drugs has the potential to improve the efficacy of standard chemotherapy, radiation therapy and immunotherapy in B cell malignancies, especially in patients with TRAF3 deletion or relevant mutations.

Supplementary Material

Key points:

Chkα and choline metabolism are up-regulated in mouse TRAF3-deficient B cells.

Reconstitution of TRAF3 in human malignant B cells inhibits choline metabolism.

Inhibition of Chkα reverses the survival phenotype of TRAF3-deficient B cells.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Dr. Jianjun Feng, Peter Zhang, Jemmie Tsai, Eris Spirollari and Kyell Schwartz for technical assistance of this study.

This study was supported by the National Institutes of Health grant R01 CA158402 (P. Xie), the Department of Defense grant W81XWH-13-1-0242 (P. Xie), a Pilot Award of Cancer Institute of New Jersey through Grant Number P30CA072720 from the National Cancer Institute (P. Xie and J. Rabinowitz), and a Busch Biomedical Grant (P. Xie); supported in part by grants from NCI R50 CA211437 (W. Lu) and NIH R01 ES026057 (R. Hart). The metabolomic and lipidomic analyses were supported by the Rutgers Cancer Institute of New Jersey Metabolomics Shared Resource and FACS analyses were supported by the Flow Cytometry Core Facility with funding from NCI-CCSG P30CA072720.

Footnotes

Disclosures

The authors declare that they have no competing financial interests.

Abbreviations used in this paper: ADSSL1, adenylosuccinate synthase like 1; Anxa4, annexin A4; BAFF, B-cell activating factor; BAFF-R, BAFF receptor; B-CLL, B cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia; B-Traf3−/− mice, B cell-specific TRAF3-deficient mice; CDP-Cho, cytidine 5’-diphosphocholine; CDP-DAG, cytidine diphosphate diacylglycerol; CDP-Etn, cytidine 5’-diphosphoethanolamine; Chkα, choline kinase α?; Cho, choline; Ct, cycle threshold; DAG, diacylglycerol; Dgka, diacylglycerol kinase α DHAP, dihydroxyacetone phosphate; DLBCL, diffuse large B-cell lymphoma; Etn, ethanolamine; FA, fatty acid; FA-O, oxidized fatty acid; Faah, fatty acid amide hydrolase; FL, follicular lymphoma; G6P, glucose-6-phosphate; GA3P, glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate; Gdpd3, glycerophosphodiester phosphodiesterase domain containing 3; Glycero-3P, glycerol-3-phoshphate; GPC, sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine; GPE, sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine; HKII, hexokinase II; HL, Hodgkin lymphoma; i.p., intraperitoneally; IP3, inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate; LACC1, laccase domain containing 1; LC-MS, liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry/mass spectrometry; LMC, littermate control; LPC, lysophosphatidylcholine; Lpcat1, lysophosphatidylcholine acyltransferase 1; LPE, lysophosphatidylethanolamine; MAG, monoacylglycerol; MM, multiple myeloma; Mthfd1, methylenetetrahydrofolate dehydrogenase 1; MTT, 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide; MZL, splenic marginal zone lymphoma; NF-κB, nuclear factor κ light chain enhancer of activated B cells; NF-κB2, noncanonical NF-κB; NHL, non-Hodgkin lymphoma; NIK, NF-κB-inducing kinase; NLRs, NOD-like receptors; P-Cho, phosphocholine; P-DMEtn, phosphodimethyl-ethanolamine; P-Etn, phosphoethanolamine; PA, phosphatidic acid; PC, phosphatidyl-choline; Pde2a, cGMP-dependent 3’,5’-cyclic phosphodiesterase 2A; PE, phosphatidyl-ethanolamine; PEMT, phosphatidylethanolamine methyl transferase; PET, positron emission tomography; PI, phosphatidylinositol; PIP, phosphatidylinositol-4-phosphate; PIP2, phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate; Pip5k1b, phosphatidylinositol-4-phosphate 5-kinase type 1β?; PLA2, phospholipase A2; Plcd3, phospholipase Cδ3; PS, phosphotidyl-serine; Pygl, glycogen phosphorylase, liver form; P value, probability value calculated by a statistical method; qRT-PCR, quantitative real time polymerase chain reaction; Ribose-5-P, ribose-5-phosphate; RLRs, RIG-I-like receptors; S7P, sedoheptoluse-7-phosphate; SD, standard deviation; SEM, standard deviation of the mean; TLRs, Toll-like receptors; TNF-R, tumor necrosis factor-receptor; TRAF3, TNF-R associated factor 3; Upb1, β-ureidopropionase 1; WM, Waldenström’s macroglobulinemia

References

- 1.Morton LM, Wang SS, Devesa SS, Hartge P, Weisenburger DD, and Linet MS. 2006. Lymphoma incidence patterns by WHO subtype in the United States, 1992–2001. Blood. 107: 265–276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ruddon R 2007. The Epidemiology of Human Cancer In Book: Cancer Biology. Edited by Ruddon RW. Fourth edition Oxford University Press; Pages: 62–116. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Horner MJ, Ries LAG, Krapcho M, Neyman N, Aminou R, Howlader N, Altekruse SF, Feuer EJ, Huang L, Mariotto A et al. November 2008. Sub. Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975–2006, National Cancer Institute; Bethesda, MD, Public-Use, www.seer.cancer.gov. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Xie P, Stunz LL, Larison KD, Yang B, and Bishop GA. 2007. Tumor necrosis factor receptor-associated factor 3 is a critical regulator of B cell homeostasis in secondary lymphoid organs. Immunity. 27: 253–267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gardam S, Sierro F, Basten A, Mackay F, and Brink R. 2008. TRAF2 and TRAF3 signal adapters act cooperatively to control the maturation and survival signals delivered to B cells by the BAFF receptor. Immunity. 28: 391–401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Keats JJ, Fonseca R, Chesi M, Schop R, Baker A, Chng WJ, Van Wier S, Tiedemann R, Shi CX, Sebag M et al. 2007. Promiscuous mutations activate the noncanonical NF-kappaB pathway in multiple myeloma. Cancer Cell. 12: 131–144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Annunziata CM, Davis RE, Demchenko Y, Bellamy W, Gabrea A, Zhan F, Lenz G, Hanamura I, Wright G, Xiao W et al. 2007. Frequent engagement of the classical and alternative NF-kappaB pathways by diverse genetic abnormalities in multiple myeloma. Cancer Cell. 12: 115–130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Moore CR, Liu Y, Shao CS, Covey LR, Morse HC 3rd,, and Xie P. 2012. Specific deletion of TRAF3 in B lymphocytes leads to B lymphoma development in mice. Leukemia. 26: 1122–1127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Moore CR, Edwards SK, and Xie P. 2015. Targeting TRAF3 Downstream Signaling Pathways in B cell Neoplasms. J. Cancer Sci. Ther 7: 67–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhu S, Jin J, Gokhale S, Lu A, Shan H, Feng J, and Xie P. 2018. Genetic Alterations of TRAF Proteins in Human Cancers. Front. Immunol 9: 2111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Walker BA, Boyle EM, Wardell CP, Murison A, Begum DB, Dahir NM, Proszek PZ, Johnson DC, Kaiser MF, Melchor L et al. 2015. Mutational Spectrum, Copy Number Changes, and Outcome: Results of a Sequencing Study of Patients With Newly Diagnosed Myeloma. J. Clin. Oncol 33: 3911–3920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hyeon J, Lee B, Shin SH, Yoo HY, Kim SJ, Kim WS, Park WY, and Ko YH. 2018. Targeted deep sequencing of gastric marginal zone lymphoma identified alterations of TRAF3 and TNFAIP3 that were mutually exclusive for MALT1 rearrangement. Mod. Pathol 31: 1418–1428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rossi D, Deaglio S, Dominguez-Sola D, Rasi S, Vaisitti T, Agostinelli C, Spina V, Bruscaggin A, Monti S, Cerri M et al. 2011. Alteration of BIRC3 and multiple other NF-kappaB pathway genes in splenic marginal zone lymphoma. Blood. 118: 4930–4934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang B, Calado DP, Wang Z, Frohler S, Kochert K, Qian Y, Koralov SB, Schmidt-Supprian M, Sasaki Y, Unitt C et al. 2015. An oncogenic role for alternative NF-kappaB signaling in DLBCL revealed upon deregulated BCL6 expression. Cell Rep.. 11: 715–726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nagel I, Bug S, Tonnies H, Ammerpohl O, Richter J, Vater I, Callet-Bauchu E, Calasanz MJ, Martinez-Climent JA, Bastard C et al. 2009. Biallelic inactivation of TRAF3 in a subset of B-cell lymphomas with interstitial del(14)(q24.1q32.33). Leukemia. 23: 2153–2155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Otto C, Giefing M, Massow A, Vater I, Gesk S, Schlesner M, Richter J, Klapper W, Hansmann ML, Siebert R et al. 2012. Genetic lesions of the TRAF3 and MAP3K14 genes in classical Hodgkin lymphoma. Br. J. Haematol 157: 702–708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Braggio E, Keats JJ, Leleu X, Van Wier S, Jimenez-Zepeda VH, Valdez R, Schop RF, Price-Troska T, Henderson K, Sacco A et al. 2009. Identification of copy number abnormalities and inactivating mutations in two negative regulators of nuclear factor-kappaB signaling pathways in Waldenstrom’s macroglobulinemia. Cancer Res. 69: 3579–3588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Xie P 2013. TRAF molecules in cell signaling and in human diseases. J. Mol. Signal 8: 7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lalani AI, Zhu S, Gokhale S, Jin J, and Xie P. 2018. TRAF molecules in inflammation and inflammatory diseases. Curr. Pharmacol. Rep 4: 64–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bishop GA, and Xie P. 2007. Multiple roles of TRAF3 signaling in lymphocyte function. Immunol. Res 39: 22–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Xie P, Kraus ZJ, Stunz LL, and Bishop GA. 2008. Roles of TRAF molecules in B lymphocyte function. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev 19: 199–207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hacker H, Tseng PH, and Karin M. 2011. Expanding TRAF function: TRAF3 as a tri-faced immune regulator. Nat. Rev. Immunol 11: 457–468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vince JE, Wong WW, Khan N, Feltham R, Chau D, Ahmed AU, Benetatos CA, Chunduru SK, Condon SM, McKinlay M et al. 2007. IAP antagonists target cIAP1 to induce TNFalpha-dependent apoptosis. Cell. 131: 682–693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Varfolomeev E, Blankenship JW, Wayson SM, Fedorova AV, Kayagaki N, Garg P, Zobel K, Dynek JN, Elliott LO, Wallweber HJ et al. 2007. IAP antagonists induce autoubiquitination of c-IAPs, NF-kappaB activation, and TNFalpha-dependent apoptosis. Cell. 131: 669–681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zarnegar BJ, Wang Y, Mahoney DJ, Dempsey PW, Cheung HH, He J, Shiba T, Yang X, Yeh WC, Mak TW et al. 2008. Noncanonical NF-kappaB activation requires coordinated assembly of a regulatory complex of the adaptors cIAP1, cIAP2, TRAF2 and TRAF3 and the kinase NIK. Nat. Immunol 9: 1371–1378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vallabhapurapu S, Matsuzawa A, Zhang W, Tseng PH, Keats JJ, Wang H, Vignali DA, Bergsagel PL, and Karin M. 2008. Nonredundant and complementary functions of TRAF2 and TRAF3 in a ubiquitination cascade that activates NIK-dependent alternative NF-kappaB signaling. Nat. Immunol 9: 1364–1370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Matsuzawa A, Tseng PH, Vallabhapurapu S, Luo JL, Zhang W, Wang H, Vignali DA, Gallagher E, and Karin M. 2008. Essential cytoplasmic translocation of a cytokine receptor-assembled signaling complex. Science. 321: 663–668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gardam S, Turner VM, Anderton H, Limaye S, Basten A, Koentgen F, Vaux DL, Silke J, and Brink R. 2011. Deletion of cIAP1 and cIAP2 in murine B lymphocytes constitutively activates cell survival pathways and inactivates the germinal center response. Blood. 117: 4041–4051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rickert RC, Jellusova J, and Miletic AV. 2011. Signaling by the tumor necrosis factor receptor superfamily in B-cell biology and disease. Immunol. Rev 244: 115–133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Edwards SK, Moore CR, Liu Y, Grewal S, Covey LR, and Xie P. 2013. N-benzyladriamycin-14-valerate (AD 198) exhibits potent anti-tumor activity on TRAF3-deficient mouse B lymphoma and human multiple myeloma. BMC Cancer. 13: 481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang L, Xing X, Chen L, Yang L, Su X, Rabitz H, Lu W, and Rabinowitz JD. 2019. Peak Annotation and Verification Engine for Untargeted LC-MS Metabolomics. Anal. Chem 91: 1838–1846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Papazyan R, Sun Z, Kim YH, Titchenell PM, Hill DA, Lu W, Damle M, Wan M, Zhang Y, Briggs ER et al. 2016. Physiological Suppression of Lipotoxic Liver Damage by Complementary Actions of HDAC3 and SCAP/SREBP. Cell Metab. 24: 863–874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Melamud E, Vastag L, and Rabinowitz JD. 2010. Metabolomic analysis and visualization engine for LC-MS data. Anal. Chem 82: 9818–9826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kamphorst JJ, Fan J, Lu W, White E, and Rabinowitz JD. 2011. Liquid chromatography-high resolution mass spectrometry analysis of fatty acid metabolism. Anal. Chem 83: 9114–9122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chida J, Yamane K, Takei T, and Kido H. 2012. An efficient extraction method for quantitation of adenosine triphosphate in mammalian tissues and cells. Anal. Chim. Acta 727: 8–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Edwards S, Baron J, Moore CR, Liu Y, Perlman DH, Hart RP, and Xie P. 2014. Mutated in colorectal cancer (MCC) is a novel oncogene in B lymphocytes. J. Hematol. Oncol 7: 56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Du P, Kibbe WA, and Lin SM. 2007. nuID: a universal naming scheme of oligonucleotides for illumina, affymetrix, and other microarrays. Biol. Direct 2: 16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Du P, Kibbe WA, and Lin SM. 2008. lumi: a pipeline for processing Illumina microarray. Bioinformatics. 24: 1547–1548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Smyth G Limma: linear models for microarray data., vol. Bioinformatics and Computational Biology Solutions using R and Bioconductor. : New York: Springer; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lalani AI, Moore CR, Luo C, Kreider BZ, Liu Y, Morse HC 3rd, and Xie P. 2015. Myeloid Cell TRAF3 Regulates Immune Responses and Inhibits Inflammation and Tumor Development in Mice. J. Immunol 194: 334–348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Edwards SK, Han Y, Liu Y, Kreider BZ, Grewal S, Desai A, Baron J, Moore CR, Luo C, and Xie P. 2016. Signaling mechanisms of bortezomib in TRAF3-deficient mouse B lymphoma and human multiple myeloma cells. Leuk. Res 41: 85–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhou S, Kurt-Jones EA, Cerny AM, Chan M, Bronson RT, and Finberg RW. 2009. MyD88 intrinsically regulates CD4 T-cell responses. J. Virol 83: 1625–1634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Edwards SK, Desai A, Liu Y, Moore CR, and Xie P. 2014. Expression and function of a novel isoform of Sox5 in malignant B cells. Leuk. Res 38: 393–401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Xie P, Kraus ZJ, Stunz LL, Liu Y, and Bishop GA. 2011. TNF Receptor-Associated Factor 3 Is Required for T Cell-Mediated Immunity and TCR/CD28 Signaling. J. Immunol 186: 143–155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hay N 2016. Reprogramming glucose metabolism in cancer: can it be exploited for cancer therapy? Nat. Rev. Cancer 16: 635–649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Siegel D, Permentier H, Reijngoud DJ, and Bischoff R. 2014. Chemical and technical challenges in the analysis of central carbon metabolites by liquid-chromatography mass spectrometry. J. Chromatogr. B Analyt. Technol. Biomed. Life Sci 966: 21–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Al Kadhi O, Melchini A, Mithen R, and Saha S. 2017. Development of a LC-MS/MS Method for the Simultaneous Detection of Tricarboxylic Acid Cycle Intermediates in a Range of Biological Matrices. J. Anal. Methods Chem 2017: 5391832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Stincone A, Prigione A, Cramer T, Wamelink MM, Campbell K, Cheung E, Olin-Sandoval V, Gruning NM, Kruger A, Tauqeer Alam M et al. 2015. The return of metabolism: biochemistry and physiology of the pentose phosphate pathway. Biol. Rev. Camb. Philos. Soc 90: 927–963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cairns RA, Harris IS, and Mak TW. 2011. Regulation of cancer cell metabolism. Nat. Rev. Cancer 11: 85–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Jiang P, Du W, and Wu M. 2014. Regulation of the pentose phosphate pathway in cancer. Protein Cell. 5: 592–602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Teo Z, Sng MK, Chan JSK, Lim MMK, Li Y, Li L, Phua T, Lee JYH, Tan ZW, Zhu P et al. 2017. Elevation of adenylate energy charge by angiopoietin-like 4 enhances epithelial-mesenchymal transition by inducing 14-3-3gamma expression. Oncogene. 36: 6408–6419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Atlante A, Giannattasio S, Bobba A, Gagliardi S, Petragallo V, Calissano P, Marra E, and Passarella S. 2005. An increase in the ATP levels occurs in cerebellar granule cells en route to apoptosis in which ATP derives from both oxidative phosphorylation and anaerobic glycolysis. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1708: 50–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mayr JA 2015. Lipid metabolism in mitochondrial membranes. J. Inherit. Metab. Dis 38: 137–144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mejia EM, and Hatch GM. 2016. Mitochondrial phospholipids: role in mitochondrial function. J. Bioenerg. Biomembr 48: 99–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Glunde K, Bhujwalla ZM, and Ronen SM. 2011. Choline metabolism in malignant transformation. Nat. Rev. Cancer 11: 835–848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ridgway ND 2013. The role of phosphatidylcholine and choline metabolites to cell proliferation and survival. Crit. Rev. Biochem. Mol. Biol 48: 20–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Arlauckas SP, Popov AV, and Delikatny EJ. 2016. Choline kinase alpha-Putting the ChoK-hold on tumor metabolism. Prog. Lipid Res 63: 28–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ecker J, and Liebisch G. 2014. Application of stable isotopes to investigate the metabolism of fatty acids, glycerophospholipid and sphingolipid species. Prog. Lipid Res 54: 14–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lacal JC, and Campos JM. 2015. Preclinical characterization of RSM-932A, a novel anticancer drug targeting the human choline kinase alpha, an enzyme involved in increased lipid metabolism of cancer cells. Mol. Cancer Ther 14: 31–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Rodriguez-Gonzalez A, Ramirez de Molina A, Fernandez F, Ramos MA, del Carmen Nunez M, Campos J, and Lacal JC. 2003. Inhibition of choline kinase as a specific cytotoxic strategy in oncogene-transformed cells. Oncogene. 22: 8803–8812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Sanchez-Lopez E, Zimmerman T, Gomez del Pulgar T, Moyer MP, Lacal Sanjuan JC, and Cebrian A. 2013. Choline kinase inhibition induces exacerbated endoplasmic reticulum stress and triggers apoptosis via CHOP in cancer cells. Cell Death Dis. 4: e933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Rahman M, and Hasan MR. 2015. Cancer Metabolism and Drug Resistance. Metabolites. 5: 571–600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.van der Veen JN, Kennelly JP, Wan S, Vance JE, Vance DE, and Jacobs RL. 2017. The critical role of phosphatidylcholine and phosphatidylethanolamine metabolism in health and disease. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Biomembr 1859: 1558–1572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Rosenwald A, Wright G, Chan WC, Connors JM, Campo E, Fisher RI, Gascoyne RD, Muller-Hermelink HK, Smeland EB, Giltnane JM et al. 2002. The use of molecular profiling to predict survival after chemotherapy for diffuse large-B-cell lymphoma. N. Engl. J. Med 346: 1937–1947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Alizadeh AA, Eisen MB, Davis RE, Ma C, Lossos IS, Rosenwald A, Boldrick JC, Sabet H, Tran T, Yu X et al. 2000. Distinct types of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma identified by gene expression profiling. Nature. 403: 503–511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Rosenwald A, Alizadeh AA, Widhopf G, Simon R, Davis RE, Yu X, Yang L, Pickeral OK, Rassenti LZ, Powell J et al. 2001. Relation of gene expression phenotype to immunoglobulin mutation genotype in B cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia. J. Exp. Med 194: 1639–1647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Xiong J, Bian J, Wang L, Zhou JY, Wang Y, Zhao Y, Wu LL, Hu JJ, Li B, Chen SJ et al. 2015. Dysregulated choline metabolism in T-cell lymphoma: role of choline kinase-alpha and therapeutic targeting. Blood Cancer J. 5: 287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Mariotto E, Bortolozzi R, Volpin I, Carta D, Serafin V, Accordi B, Basso G, Navarro PL, Lopez-Cara LC, and Viola G. 2018. EB-3D a novel choline kinase inhibitor induces deregulation of the AMPK-mTOR pathway and apoptosis in leukemia T-cells. Biochem. Pharmacol 155: 213–223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Mori N, Wildes F, Kakkad S, Jacob D, Solaiyappan M, Glunde K, and Bhujwalla ZM. 2015. Choline kinase-alpha protein and phosphatidylcholine but not phosphocholine are required for breast cancer cell survival. NMR Biomed. 28: 1697–1706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Abdelzaher E, and Mostafa MF. 2015. Lysophosphatidylcholine acyltransferase 1 (LPCAT1) upregulation in breast carcinoma contributes to tumor progression and predicts early tumor recurrence. Tumour Biol. 36: 5473–5483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Grupp K, Sanader S, Sirma H, Simon R, Koop C, Prien K, Hube-Magg C, Salomon G, Graefen M, Heinzer H et al. 2013. High lysophosphatidylcholine acyltransferase 1 expression independently predicts high risk for biochemical recurrence in prostate cancers. Mol. Oncol 7: 1001–1011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Uehara T, Kikuchi H, Miyazaki S, Iino I, Setoguchi T, Hiramatsu Y, Ohta M, Kamiya K, Morita Y, Tanaka H et al. 2016. Overexpression of Lysophosphatidylcholine Acyltransferase 1 and Concomitant Lipid Alterations in Gastric Cancer. Ann. Surg. Oncol 23 Suppl 2: S206–213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Endsley MP, Thill R, Choudhry I, Williams CL, Kajdacsy-Balla A, Campbell WB, and Nithipatikom K. 2008. Expression and function of fatty acid amide hydrolase in prostate cancer. Int. J. Cancer 123: 1318–1326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Kong Y, Zheng Y, Jia Y, Li P, and Wang Y. 2016. Decreased LIPF expression is correlated with DGKA and predicts poor outcome of gastric cancer. Oncol. Rep 36: 1852–1860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Caprini E, Cristofoletti C, Arcelli D, Fadda P, Citterich MH, Sampogna F, Magrelli A, Censi F, Torreri P, Frontani M et al. 2009. Identification of key regions and genes important in the pathogenesis of sezary syndrome by combining genomic and expression microarrays. Cancer Res. 69: 8438–8446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Zhang F, Sha J, Wood TG, Galindo CL, Garner HR, Burkart MF, Suarez G, Sierra JC, Agar SL, Peterson JW et al. 2008. Alteration in the activation state of new inflammation-associated targets by phospholipase A2-activating protein (PLAA). Cell Signal. 20: 844–861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Mambetsariev N, Lin WW, Wallis AM, Stunz LL, and Bishop GA. 2016. TRAF3 deficiency promotes metabolic reprogramming in B cells. Sci. Rep 6: 35349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Andersson A, Ritz C, Lindgren D, Eden P, Lassen C, Heldrup J, Olofsson T, Rade J, Fontes M, Porwit-Macdonald A et al. 2007. Microarray-based classification of a consecutive series of 121 childhood acute leukemias: prediction of leukemic and genetic subtype as well as of minimal residual disease status. Leukemia. 21: 1198–1203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Zhan F, Barlogie B, Arzoumanian V, Huang Y, Williams DR, Hollmig K, Pineda-Roman M, Tricot G, van Rhee F, Zangari M et al. 2007. Gene-expression signature of benign monoclonal gammopathy evident in multiple myeloma is linked to good prognosis. Blood. 109: 1692–1700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Lautner-Csorba O, Gezsi A, Erdelyi DJ, Hullam G, Antal P, Semsei AF, Kutszegi N, Kovacs G, Falus A, and Szalai C. 2013. Roles of genetic polymorphisms in the folate pathway in childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia evaluated by Bayesian relevance and effect size analysis. PLoS One. 8: e69843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Weiner AS, Beresina OV, Voronina EN, Voropaeva EN, Boyarskih UA, Pospelova TI, and Filipenko ML. 2011. Polymorphisms in folate-metabolizing genes and risk of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Leuk. Res 35: 508–515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Cuccurullo V, Di Stasio GD, Evangelista L, Castoria G, and Mansi L. 2017. Biochemical and Pathophysiological Premises to Positron Emission Tomography With Choline Radiotracers. J. Cell. Physiol 232: 270–275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.