Abstract

Renal cell carcinoma (RCC) is associated with various genetic alterations. Although whole-genome/exome sequencing analysis has revealed that nuclear genome alterations are associated with clinical outcomes, the association between nucleotide alterations in the mitochondrial genome and RCC clinical outcomes remains unclear. In this study, we analyzed somatic mutations in the mitochondrial D-loop region, using RCC samples from 61 consecutive patients with localized RCC. Moreover, we analyzed the relationship between D-loop mutations and NADH dehydrogenase subunit 1 (MT-ND1) mutations, which we previously found to be associated with clinical outcomes in localized RCC. Among the 61 localized RCCs, 34 patients (55.7%) had at least one mitochondrial D-loop mutation. The number of D-loop mutations was associated with larger tumor diameter (>32 mm) and higher nuclear grade (≥ISUP grade 3). Moreover, patients with D-loop mutations showed no differences in cancer-specific survival when compared with patients without D-loop mutations. However, the co-occurrence of D-loop and MT-ND1 mutations improved the predictive accuracy of cancer-related deaths among our cohort, increasing the concordance index (C-index) from 0.757 to 0.810. Thus, we found that D-loop mutations are associated with adverse pathological features in localized RCC and may improve predictive accuracy for cancer-specific deaths when combined with MT-ND1 mutations.

Keywords: mitochondrial DNA, D-loop mutations, NADH dehydrogenase subunit 1, renal cell carcinoma, cancer-specific survival, prognostic factor

1. Introduction

In renal cell carcinoma (RCC), representative gene mutations and chromosomal hyperploidy have been shown to depend on the histological subtype of the RCC, e.g., clear cell, papillary, chromophobe, or other subtypes [1]. Mutations in the von Hippel–Lindau gene have been extensively studied in clear cell RCC (ccRCC) and have been shown to play a critical role in the initiation and progression of this disease [2]. Papillary RCC is the second most common histological subtype of RCC and is characterized genetically by trisomy and tetrasomy of chromosome 7, trisomy of chromosome 17, and loss of the Y chromosome [3]. Chromophobe RCC accounts for approximately 5% of all RCCs and is characterized by loss of chromosomes 1, 2, 6, 10, 13, 17, and 21 [4,5]. Gene mutations in RCC do not only affect the tumor histological phenotype but also alter clinical behaviors or outcomes. Recent large-scale whole-exome and targeted sequencing studies have revealed frequent recurrent mutations in ccRCC [6,7] and have reported that specific gene mutations, such as BAP1 or SETD2 mutations, are associated with shorter overall survival and higher relapse rates [8]. A comprehensive genome analysis of RCC is currently underway to assess nuclear DNA (nDNA) mutations in RCC; however, the mutational profiles of mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) in patients with RCC have not been sufficiently elucidated, and the associations of mtDNA mutations with clinicopathological features and prognoses among patients with localized RCC are poorly understood.

MtDNA is a circular, double-stranded DNA consisting of 16,569 bp and has a more compact DNA structure than nDNA. MtDNA has 13 protein-coding regions and a displacement loop (D-loop) region that controls the replication and transcription of mtDNA. In various types of cancers, somatic mutations in mtDNA were identified using tumor and paired nontumor tissues [9]. Moreover, several studies have reported that mtDNA mutations may have applications as prognostic markers [10,11]. In a previous study, we analyzed mutations in the mitochondrial NADH dehydrogenase subunit 1 (MT-ND1) gene to determine their associations with clinicopathological parameters and postoperative recurrence of RCC in 62 Japanese patients [12]. Our previous results suggested a significant association between the presence of MT-ND1 mutations and the postoperative recurrence of localized RCC. Accordingly, mtDNA mutations may have applications in predicting malignant behaviors that cannot be explained by clinicopathological findings alone [12,13].

The D-loop region, a noncoding region of approximately 1120 bp that is responsible for the regulation of the replication and transcription of mtDNA, is a known mutational hot spot and accumulates mutations at higher rates than other coding regions of mtDNA [14,15,16,17]. The D-loop region has been reported to have a high mutation for various cancers, such as skin basal cell carcinoma, urothelial carcinoma, and colorectal carcinoma [18,19,20]. In addition, mutations in the D-loop region in cancer tissues are predictive of clinical outcome. The presence of D-loop mutations in pediatric acute leukemia, esophageal squamous cell carcinoma, oral squamous cell carcinoma, and hepatocellular carcinoma has been reported to be a risk factor for poor prognosis. Moreover, in RCC, a previous study reported a relationship between single nucleotide polymorphisms in the D-loop region and survival rates [21]. However, no studies have reported the association between somatic mutations in the D-loop region and cancer-specific survival (CSS).

Accordingly, in this study, we investigated mutation profiles of the D-loop region in RCC, the association of D-loop mutations with clinical outcomes, and the impact of D-loop mutations combined with MT-ND1 mutations on predictive accuracy for clinical outcomes. Overall, we found that D-loop mutations are associated with adverse pathological features in localized RCC, which may improve the prediction of cancer-specific deaths when used in combination with MT-ND1 mutations.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Populations and Tissues

In total, 61 consecutive patients with localized RCC who underwent curative surgery (nephrectomy or partial nephrectomy) between January and December 2010 at a single institution were enrolled in this study. Demographic and pathological data were obtained from medical records and pathological reports. Formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tissue specimens were collected from these 61 patients. This study was approved by the institutional review board for clinical research of Tokai University (Approval No. 15R-065).

2.2. RCC Tissue Sampling

The sampling method for representative cancerous tissues and corresponding noncancerous renal tissues from FFPE tissue specimens was described previously [12]. Briefly, the locations of cancerous tissues and the corresponding noncancerous tissues within the FFPE tissue specimens were recorded by two pathologists (C.I. and H.Ka); subsequently, the tissues were obtained with an 18-G needle.

2.3. DNA Extraction, Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR), and Sanger Sequencing

FFPE tissue punch samples were washed three times with 500 μL lemosol and three times with 99.5% ethanol to remove lemosol. Tissues were next incubated with 200 μg proteinase K in HMW Buffer (10 mM Tris-Cl [pH 8.0], 150 mM NaCl, 10 mM ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid [EDTA], 0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate) at 60 °C overnight, followed by extraction with phenol–chloroform (phenol/chloroform/isoamyl alcohol, 25:24:1) twice at 11,000 rpm for 10 min at room temperature. DNA was precipitated by the addition of 0.1 volume of 3 M Na-AcOH and 2.5 volumes of ice-cold ethanol. After centrifugation at 15,000 rpm at 4 °C for 20 min, DNA pellets were rinsed with 70% cold ethanol, dried, and dissolved in TE buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.0] and 1 mM EDTA). Total mtDNA was amplified by PCR with the following primer sets, which were designed to cover the entire 1120-bp mtDNA D-loop region: HUMmt-148F, 5′-ATCCCATTATTTATCGCACCT-3′; homoR1, 5′-AAATAATAGGATGAGGCAGGAATCAAAGA-3′; Homo_mt_Gap_3F, 5′-TCGGAGGACAACCAGTAAGC-3′; Homo_mt_Gap_3R, 5′-GCACTCTTGTGCGGGATATT-3′; homoF2, 5′-GCACTCTTGTGCGGGATATT-3′; F376, 5′-TAACACCAGCCTAACCAGATTTC-3′; R505, 5′-TGTGTGTGCTGGGTAGGATGG-3′; F320, 5′-GCTTCTGGCCACAGCACTTAAAC-3′; R465, 5′-GATGAGATTAGTAGTATGGGAGTGGG-3′; F16137, 5′-CCATAAATACTTGACCACCTGTAG-3′; R16269, 5′-AGGTTTGTTGGTATCCTAGTGGGTGA-3′; F16137, 5′-CCATAAATACTTGACCACCTGTAG-3′; and R16231, 5′-GAGTTGCAGTTGATGTGTGATAGTTG-3′.

PCR was performed by KOD FX Neo (Toyobo, Osaka, Japan) under the following conditions: melting at 98 °C for 5 s, annealing at 63–66 °C for 15 s, and extension at 68 °C for 20 s, for a total of 35 cycles. PCR products were treated with EXOSAP-IT (Affimetrix, Santa Clara, CA, USA) and directly sequenced using a Big Dye Terminator v3.1 Reaction Kit (Applied Biosystems, Torrance, CA, USA) and an ABI 3500xL DNA sequencer (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA). We also evaluated sequences in the D-loop region from one to five times to confirm the mutations. D-loop sequence data were assembled using ATCG software (Genetyx, Tokyo, Japan). Accession numbers for the nucleotide sequences of the D-loop obtained from 61 patients included in the present study are as follows: LC 491360–LC 491420.

2.4. Somatic Mutations in the D-loop Region

The alignment of the nucleotide sequence of the D-loop region was performed by Clustal W using Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis (MEGA, version 6; Tempe, AZ, USA; Pennsylvania, USA; Tokyo, Japan) [22]. NC_012920.1 was selected as the reference sequence for the D-loop region. As previously described, the determination of somatic mutations in the D-loop region by comparative sequence analysis was divided into two steps [12]. Initially, we extracted the D-loop sequences of 61 healthy Japanese individuals from DDBJ/EMBL/GenBank databases and then extracted candidates for mutation sites in the D-loop region. Next, candidate mutation sites were compared with the sequence data of corresponding noncancerous renal tissue, and finally, somatic mutations in the RCC tissue were determined.

2.5. Somatic Mutations in the MT-ND1 Gene

MT-ND1 sequence data for 61 Japanese patients with localized RCC were extracted from DDBJ/EMBL/GenBank databases, as described in our previous study [12]. Accession numbers were LC178840.1–LC178883.1 and LC178885.1–LC178901.1. Mutation sites were determined based on NC_012920.1 as the reference sequence for the MT-ND1 gene.

2.6. Statistical Analysis

All statistical analyses were performed with JMP version 12.0.1 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA), R (The R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria), and EZR (Saitama Medical Center, Jichi Medical University, Saitama, Japan), a graphical user interface for R that adds statistical functions frequently used in biostatistics [23]. Seven demographic and pathological variables were selected to evaluate their associations with the presence/absence of D-loop mutations, the number of D-loop mutations, and CSS. Categorical variables were calculated using Fisher’s exact tests and Chi-square tests. Mann–Whitney U tests were used for continuous variables. CSS was calculated using the Kaplan–Meier method as the time from surgery to death caused by RCC, and results were compared using log-rank tests. Seven variables were binarized as follows: age (≤ 62 years versus > 62 years), sex (women versus men), tumor diameter (≤ 32 mm versus > 32 mm), histology type (ccRCC versus non-ccRCC), pT stage (≤ pT2 versus ≥ pT3), International Society of Urological Pathology (ISUP) grade (1/2 versus 3/4), and microvascular invasion (MVI) (absence or presence). Age and tumor diameter were separated using median values. The other variables were binarized according to our previous study [12]. We also evaluated the association of CSS with D-loop mutations with or without MT-ND1 mutations identified in our previous study. The C-index was calculated to discriminate the predictive accuracy for CSS between a model, including only MT-ND1 mutations and D-loop mutations added to the MT-ND1 model [24]. The C-index ranged from 0 to 1.0, with 1.0 indicating a perfect model and 0.5 indicating a random model or no discrimination. Results with p values of less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. Demographic and Pathological Features of the Study Population

The characteristics of the study population with and without D-loop mutations are shown in Table 1. Overall, the median age of patients was 62 years (range: 39–80 years). The cohort contained 47 men and 14 women and comprised 42 patients with nephrectomy and 19 patients with partial nephrectomy. The median observation period was 95 months (range: 29–112 months). As of August 2019, recurrence had occurred in 10 patients, and five patients had died of cancer-related causes. Pathological findings showed that the excised specimens had a median tumor diameter of 32 mm (range: 12–105 mm), and there were 54 patients with ccRCC and seven patients with RCC of other tissue types. The pathological T stage was T1 in 53 patients, T2 in three patients, T3 in four patients, and T4 in one patient. The nuclear grade was grade 1 in two patients, grade 2 in 50 patients, grade 3 in seven patients, and grade 4 in two patients, according to the International Society of Urological Pathology (ISUP) classification. Microvascular invasion (MVI) was observed in 13 patients. There were no significant differences in demographic and pathological data between patients with or without D-loop mutations.

Table 1.

Characteristics of patients with localized renal cell carcinoma (RCC) with or without D-loop mutations.

| Variable | Overall (N = 61) | With D-Loop Mutations (N = 34) | Without D-Loop Mutations (N = 27) | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years), median (range) | 62 (39–80) | 67 (39–80) | 60 (39–79) | 0.188 |

| Sex | ||||

| Female | 14 | 10 (16.4) | 4 (6.6) | 0.228 |

| Male | 47 | 24 (39.3) | 23 (37.7) | |

| Histological subtype | ||||

| Clear cell subtype | 54 | 28 (45.9) | 26 (42.6) | 0.121 |

| Non clear subtype | 7 | 6 (9.8) | 1 (1.6) | |

| Tumor diameter (mm), median (range) | 32 (12–105) | 36.5 (13–100) | 28 (12–105) | 0.069 |

| Pathological T stage | 0.156 | |||

| T1a | 39 | 18 | 21 | |

| T1b | 14 | 11 | 3 | |

| T2a | 3 | 1 | 2 | |

| T2b | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| T3a | 1 | 1 | 0 | |

| T3b | 3 | 2 | 1 | |

| T4 | 1 | 1 | 0 | |

| ISUP grade | 0.156 | |||

| 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | |

| 2 | 50 | 25 | 25 | |

| 3 | 7 | 6 | 1 | |

| 4 | 2 | 2 | 0 | |

| MVI | ||||

| Absence | 48 | 25 (41.0) | 23 (37.7) | 0.352 |

| Presence | 13 | 9 (14.8) | 4 (6.6) |

RCC, renal cell carcinoma; MVI, microvascular invasion.

3.2. Mitochondrial D-loop Mutations

In total, 79 mutations were identified at 51 sites in the D-loop region of 34 patients (55.7%, 34/61 patients). The mean and median number of mutation sites per patient were 1.3 and 1 (SD: 1.75, range: 0–8) sites, respectively, whereas the mean and median number of patients per mutation site was 1.5 and 1 (SD: 1.07, range: 1–7) patients, respectively. Specifically, patients hk370 and hk407 contained eight mutations in the D-loop region, which accounted for the highest number of mutations per patient. The mutation profiles of the D-loop region and ND1 gene are shown in Table 2. The D-loop mutation rate was 1.295 (79 mutations/61 patients), and the ND1 mutation rate, as determined in our previous study, was 0.475 (29 mutations/61 patients) [12]. The D-loop mutation rate was approximately 2.7 times higher than the MT-ND1 mutation rate. The number of mutation sites per patient was associated with age (> 62 years), histological subtype (non-clear subtype), tumor diameter (> 32 mm), and ISUP grade (grades 3 and 4), as shown in Table 3. Of the 51 mutation sites, 17 mutation sites were found in more than two patients. Mutation at position 16295 was found in seven patients (hk362, 377, 379, 384, 407, 415, and 416), at position 249 in five patients (hk384, 388, 404, 413, and 418), and at position 310 in three patients (hk376, 400, and 403).

Table 2.

Mutation profiles of the D-loop region and the NADH dehydrogenase subunit 1 (MT-ND1) gene.

| Patient | Base Change in the D-Loop | Number of Mutations | Base Change in MT-ND1 | Number of Mutations | Sum of Mutations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| hk346 | None | 0 | None | 0 | 0 |

| hk347 | None | 0 | C4197Y | 2 | 2 |

| T4248Y | |||||

| hk348 | None | 0 | None | 0 | 0 |

| hk350 | C16260Y | 1 | None | 0 | 1 |

| hk352 | None | 0 | None | 0 | 0 |

| hk354 | C146Y | 2 | None | 0 | 2 |

| T152Y | |||||

| hk355 | A16183C | 4 | C3497T | 1 | 5 |

| T16189Y | |||||

| T16217Y | |||||

| T16223Y | |||||

| hk356 | None | 0 | None | 0 | 0 |

| hk357 | T16189Y | 1 | C4197Y | 1 | 2 |

| hk358 | None | 0 | None | 0 | 0 |

| hk359 | G94R | 1 | None | 0 | 1 |

| hk361 | C146Y | 3 | None | 0 | 3 |

| T152Y | |||||

| C16261Y | |||||

| hk362 | T16209Y | 2 | C3970Y | 1 | 3 |

| C16291Y | |||||

| hk363 | None | 0 | T4248Y | 1 | 1 |

| hk364 | C16527T | 1 | C3497T | 2 | 3 |

| G3635A | |||||

| hk365 | None | 0 | None | 0 | 0 |

| hk366 | None | 0 | None | 0 | 0 |

| hk367 | G16390R | 1 | None | 0 | 1 |

| hk368 | None | 0 | C4197Y | 2 | 2 |

| T4248Y | |||||

| hk369 | C16290Y | 2 | None | 0 | 2 |

| G16319R | |||||

| hk370 | A202R | 8 | None | 0 | 8 |

| 309insCC | |||||

| T16136C | |||||

| A16183C | |||||

| T16217Y | |||||

| T16223Y | |||||

| C16261Y | |||||

| C16527T | |||||

| hk371 | None | 0 | None | 0 | 0 |

| hk372 | T16311Y | 2 | A4200W | 2 | 4 |

| A16316R | T4216Y | ||||

| hk374 | None | 0 | None | 0 | 0 |

| hk375 | None | 0 | None | 0 | 0 |

| hk376 | 8C 303 2C | 2 | None | 0 | 2 |

| T310Y | |||||

| hk377 | T60W | 3 | None | 0 | 3 |

| C16261T | |||||

| T16368C | |||||

| hk379 | C16291T | 1 | None | 0 | 1 |

| hk380 | None | 0 | None | 0 | 0 |

| hk382 | None | 0 | A4200W | 2 | 2 |

| T4216Y | |||||

| hk383 | None | 0 | C3572ins | 1 | 1 |

| hk384 | 249Adel | 3 | None | 0 | 3 |

| A16203G | |||||

| C16291Y | |||||

| hk385 | G68A | 2 | G3496T | 3 | 5 |

| G16390R | C4141Y | ||||

| T4248Y | |||||

| hk387 | None | 0 | C4197Y | 2 | 2 |

| T4248Y | |||||

| hk388 | 249Adel | 3 | None | 0 | 3 |

| T485C | |||||

| C16344Y | |||||

| hk389 | C16245Y | 1 | None | 0 | 1 |

| hk390 | None | 0 | None | 0 | 0 |

| hk391 | None | 0 | None | 0 | 0 |

| hk392 | T16195C | 3 | G4048R | 2 | 5 |

| T16297C | C4071Y | ||||

| T16298C | |||||

| hk393 | T60C | 2 | T3368Y | 1 | 3 |

| G263A | |||||

| hk394 | None | 0 | A4200W | 2 | 2 |

| T4216Y | |||||

| hk395 | None | 0 | None | 0 | 0 |

| hk397 | None | 0 | None | 0 | 0 |

| hk398 | None | 0 | None | 0 | 0 |

| hk400 | T72Y | 2 | None | 0 | 2 |

| T310Y | |||||

| hk401 | A202G | 1 | T4117Y | 1 | 2 |

| hk402 | None | 0 | None | 0 | 0 |

| hk403 | G73R | 4 | C3328Y | 2 | 6 |

| C194Y | C3970T | ||||

| T204C | |||||

| T310Y | |||||

| hk404 | 249Adel | 2 | None | 0 | 2 |

| A16203G | |||||

| hk405 | C16320A | 1 | G4113R | 1 | 2 |

| hk407 | G73A | 8 | None | 0 | 8 |

| T131C | |||||

| C16111Y | |||||

| T16140Y | |||||

| C16234Y | |||||

| T16243Y | |||||

| C16291Y | |||||

| A16463G | |||||

| hk408 | None | 0 | None | 0 | 0 |

| hk410 | C6 568 C8 | 1 | None | 0 | 1 |

| hk411 | G251R | 2 | None | 0 | 2 |

| C194Y | |||||

| hk412 | None | 0 | None | 0 | 0 |

| hk413 | 249Adel | 2 | None | 0 | 2 |

| T16172Y | |||||

| hk414 | None | 0 | None | 0 | 0 |

| hk415 | C16291T | 1 | None | 0 | 1 |

| hk416 | C16291Y | 1 | None | 0 | 1 |

| hk417 | A16254G | 1 | None | 0 | 1 |

| hk418 | 249Adel | 5 | None | 0 | 5 |

| G16129R | |||||

| C16232M | |||||

| T16249Y | |||||

| C16344Y |

Table 3.

Association between the number of D-loop mutations and demographic/pathological factors.

| Variables | Overall (N = 61) | Number of D-Loop Mutations Median (IQR) | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 0.012 | ||

| ≤62 | 31 | 0 (0–1) | |

| >62 | 30 | 1.5 (0–2.75) | |

| Sex | 0.311 | ||

| Female | 14 | 1 (0.25–2) | |

| male | 47 | 1 (0–2) | |

| Histological subtype | 0.045 | ||

| Clear cell subtype | 54 | 1 (0–2) | |

| Non-clear cell subtype | 7 | 2 (1–4) | |

| Tumor diameter | 0.029 | ||

| ≤32 | 31 | 0 (0–1.5) | |

| >32 | 30 | 1 (0.25–2.0) | |

| Pathological T stage (pT) | 0.197 | ||

| ≤pT2 | 56 | 1 (0–2) | |

| ≥pT3 | 5 | 2 (1–3) | |

| ISUP grade | 0.029 | ||

| ≤ISUP2 | 52 | 0.5 (0–2) | |

| ≥ISUP3 | 9 | 2.0 (1–3) | |

| MVI | 0.257 | ||

| Absencee | 48 | 1 (0–2) | |

| Presence | 13 | 1 (0–2) |

3.3. Survival Analysis for Integration of Mutations in the MT-ND1 Gene and D-loop Region

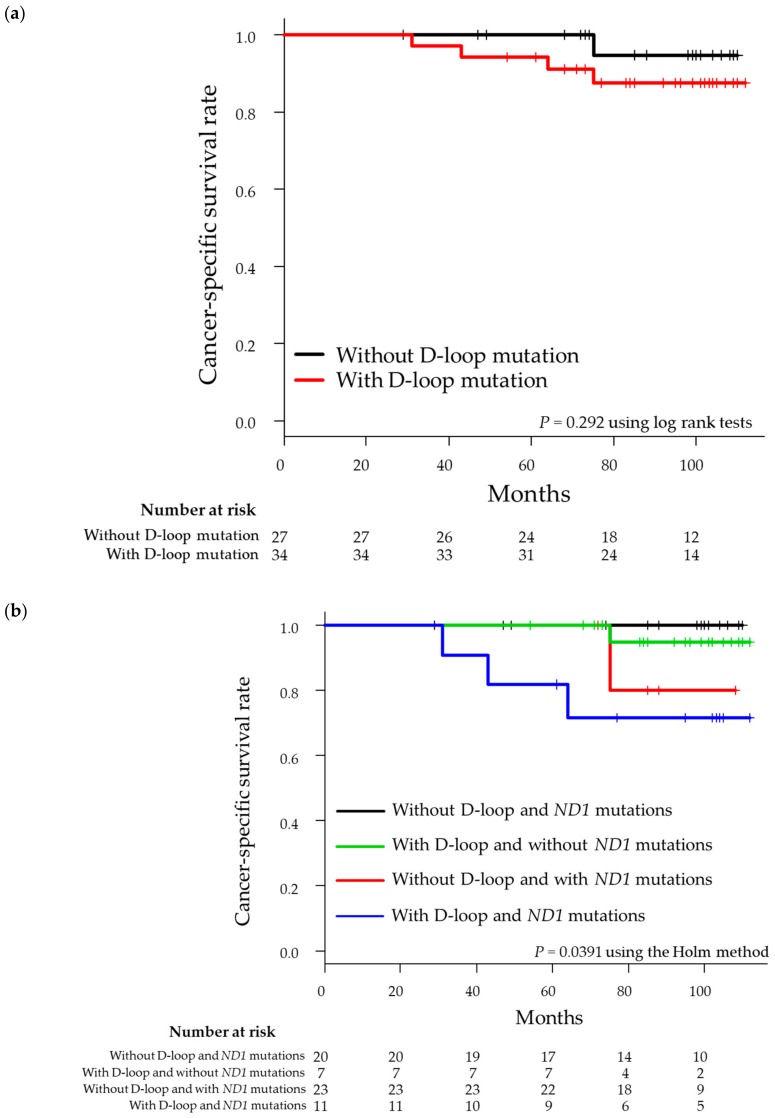

As shown in Figure 1a, CSS did not significantly differ according to the presence (94.1%) or absence of D-loop mutations (100%; p = 0.292). After the integration of mutation data for the D-loop region and MT-ND1 gene, 41 patients were found to have mutations in the D-loop region and/or MT-ND1 gene. Of these 41 patients, 11 patients had mutations in both the D-loop region and the MT-ND1 gene, 23 patients had mutations only in the D-loop region, and seven patients had mutations only in the MT-ND1 gene, whereas 20 patients did not have mutations in either the D-loop region or the MT-ND1 gene. Log-rank tests further showed that CSS was worse in patients with both D-loop and MT-ND1 mutations (Figure 1b). After integrating the data for D-loop mutations and MT-ND1 mutations, we found that the concordance index (C-index) increased from 0.757 to 0.810 (Table 4).

Figure 1.

Kaplan–Meier plot of cancer-specific survival in 61 patients with localized renal cell carcinoma. (a) Patients were stratified into tumors with or without D-loop mutations. (b) Patients were stratified according to the presence of D-loop and/or MT-ND1 mutations.

Table 4.

C-index of a predictive model for CSS.

| Model | C-Index | Lower | Upper |

|---|---|---|---|

| 95% CI | 95% CI | ||

| ND1 | 0.757 | 0.419 | 1.000 |

| ND1 and D-loop | 0.810 | 0.527 | 1.000 |

3.4. Relationship Between Mutation Site and Other Cancers Based on Database Analysis

We focused on mutation sites from five patients (hk385, hk392, hk394, hk400, and hk403) who had died from RCC. Among these patients, three (hk385, hk392, and hk403) had mutations in both the D-loop region and MT-ND1. In addition, we found that patient hk394 had mutations only in the MT-ND1 gene, whereas patient hk400 had mutations only in the D-loop region. Therefore, we examined related studies using the MITOMAP and PubMed (NCBI) databases to determine whether these mutation sites may be related to other types of malignant tumors as well (Table 5). We found that previous reports had described associations of mutations in the D-loop region with esophageal cancer, nasopharyngeal carcinoma, breast cancer, and ovarian cancer. Additional reports described associations between mutations in the MT-ND1 gene and thyroid tumors, ovarian carcinoma, colorectal cancer, and prostate cancer.

Table 5.

Database analysis of specific mutation sites in the D-loop region and MT-ND1 gene in five patients who died from RCC.

| Patient | D-Loop | MT-ND1 | Sites of Recurrence | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Our study Polymorphisms |

Cancer Types | MITOMAP Polymorphisms |

Our study Polymorphisms |

Cancer Types | MITOMAP Polymorphisms |

Cancer Types | |

| hk385 | G68A | Esophageal cancer PMID: 14639607 |

G68A | T4248Y | Thyroid tumors PMID: 10803467 |

T4248C | Liver Lung |

| G16390R | 1. Nasopharyngeal carcinoma PMID: 18376149 |

G16390A | None | None | |||

| 2. Breast cancer PMID: 16568452 |

G16390 A/G | ||||||

| 3. Ovarian cancer PMID: 18842121 |

G16390A | ||||||

| hk392 | T16195C | None | G4048R | 1. Ovarian carcinoma PMID: 11507041 |

G4048A | Local Lung |

|

| 2. Colon cancer PMID: 29842994 |

G4048A | ||||||

| T16297C | Nasopharyngeal carcinoma (PMID: 18376149) |

T16297C | C4071Y | Ovarian carcinoma PMID: 11507041 |

C4071T | ||

| T16298C | 1. Nasopharyngeal carcinoma PMID: 18376149 |

T16298C | None | None | |||

| 2. Ovarian cancer PMID: 18842121 |

T16298C | ||||||

| hk394 | None | None | T4216Y | 1. Thyroid tumors PMID: 10803467 |

T4216C | Lung | |

| 2. Prostate cancer PMID: 11526508 |

T4216C | ||||||

| 3. Colorectal cancer PMID: 19050702 |

T4216C | ||||||

| hk400 | T72Y | Ovarian cancer PMID: 18842121 |

T72C | None | None | Bone Local Lung |

|

| T310Y | Nasopharyngeal carcinoma PMID: 18376149 |

T310C | |||||

| hk403 | A73R | 1. Ovarian cancer PMID: 16942794, 18842121 |

A73G | C3970T | 1. Ovarian carcinoma PMID: 11507041 |

C3970T | Bone |

| 2. Nasopharyngeal carcinoma PMID: 18376149 |

A73G | ||||||

| 2. Colorectal cancer PMID: 19050702 |

C3970T | ||||||

4. Discussion

In the current study, we identified somatic D-loop mutations among 55.7% of patients with localized RCC. The mutation number per patient in the D-loop region was approximately 2.7-fold higher than that in the MT-ND1 gene, as determined in our previous study [12]. A recent large-scale study analyzing the whole mitochondrial genome in prostate cancer using next-generation sequencing showed that the D-loop region was the most frequently mutated region, with mutations present in 15.4% of tumors [25]. However, no studies have evaluated the full range of sequences of the D-loop region from localized RCC tissue using formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded (FFPE) specimens. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study demonstrating a high mutation rate in the D-loop region in Japanese patients with localized RCC.

In our RCC cohort, larger tumor diameter (>32 mm) and higher ISUP grade (≥grade 3) were associated with larger numbers of D-loop mutations. Several previous studies have also reported associations between the number of D-loop mutations in various cancerous tissues and an adverse pathological state, such as tumor differentiation and advanced T-status [17,26]. These results suggested that the accumulation of mutations in the D-loop region may be related to an aggressive cancer phenotype. Combination therapy with immune checkpoint inhibitors has recently been recommended as first-line treatment by the International Metastatic RCC Database Consortium for patients with metastatic ccRCC with intermediate to poor risk [27,28]. Tumor mutation burden (TMB) is a known biomarker that serves as a predictive factor for the effectiveness of immune checkpoint inhibitors in multiple cancers [29,30,31]. Thus, mutations in the D-loop region, which occur more frequently than mutations in nDNA, may act in a similar way to TMB and function as potential biomarkers for predicting the effectiveness of immune checkpoint inhibitors.

The association between the presence of D-loop mutations and clinical prognosis is controversial. A recent study analyzing somatic mutations in the D-loop region of 120 patients with oral squamous cell carcinoma showed that the 5-year survival rate in patients with somatic mutations was significantly higher than that in patients without mutations [32]. Alternatively, the esophageal squamous cell carcinoma survival rate of patients with D310 mutations was lower than that in patients without this mutation [33]. In our RCC cohort, the presence of D-loop mutations was not significantly associated with CSS when considered alone; however, when integrating mutations in the MT-ND1 gene and D-loop region, there was a clear separation of the CSS curve. Indeed, 11 patients with both MT-ND1 and D-loop mutations showed worse CSS, and the 5-year CSS was 81.8%. Furthermore, our results revealed that the 5-year CSS rate in 20 patients without mutations in the D-loop region or MT-ND1 gene was 100%. This result indicates that patients without any mutations in the MT-ND1 gene and D-loop region may have a favorable prognosis.

Analysis of D-loop mutations, together with MT-ND1 gene mutations, may improve the accuracy of predictive models for the CSS of localized RCC. To further examine the accuracy of these models, we evaluated the predictive power of each model by calculating the C-index [24]. The results showed that the C-index for predicting CSS improved from 0.757 to 0.810 by integrating MT-ND1 mutations and D-loop mutations. To the best of our knowledge, only a few studies have previously reported the ability of mtDNA mutations to predict clinical outcome in patients with RCC [12,21,34]. Moreover, this is the first study to report the ability of D-loop mutations to improve the prediction accuracy for CSS in localized RCC.

Database analysis revealed that mutation sites related to poor prognosis in patients in this study were found in other types of malignant tumors, such as nasopharyngeal carcinoma, papillary thyroid carcinoma, and ovarian cancer. Thus, these findings suggested that these mutation sites may be candidates for predicting the survival of patients with localized RCC and other malignant tumors. Indeed, patients with mutations in both regions showed a higher risk of recurrence or death, and three patients (hk385, hk392, and hk403), who had both of these mutations, died during our study.

Our study had several limitations. First, the study was conducted at a single center, and patient data, including outcomes and pathological data, were collected retrospectively. Therefore, there may have been some bias to the results. In addition, our study cohort was small. Thus, further studies with larger cohorts and a multicenter center setting are needed. Second, we did not evaluate smoking or alcohol habits, which may affect mtDNA mutations. Moreover, we did not analyze nDNA mutations, which may be correlated with mtDNA for evaluating clinical outcomes.

5. Conclusions

The present study was retrospective in its design, and the study cohort was small; therefore, prospective and larger cohort studies are required to validate our results. Nevertheless, we showed that there were high mutation rates in the mitochondrial D-loop region and that accumulation of D-loop mutations was associated with adverse pathological tumor features in localized RCC. Furthermore, we found that patients with RCC with both D-loop and MT-ND1 mutations exhibited more advanced CSS than patients with either D-loop mutations or MT-ND1 mutations. The C-index improved following the inclusion of D-loop mutations in the ND1 risk model. Thus, we established an improved predictive model using genetic markers of mtDNA mutations.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Hiroshi Kamiguchi (the Support Center for Medical Research and Education, Tokai University).

Author Contributions

H.K. (Hakushi Kim) and T.K. contributed equally to this study. H.K. (Hakushi Kim) and T.K. conceptualized the study. H.K. (Hakushi Kim), C.I., H.K. (Hiroshi Kajiwara), and T.K. carried out the experimental protocols. T.K. assisted with software analysis; M.N., Y.K., M.H., S.S., N.N., H.K. (Hiroyuki Kobayashi), and A.M. performed data validation. Y.O. and H.K. (Hiroyuki Kobayashi) performed the statistical analysis. H.K. (Hakushi Kim) and T.K. completed data curation. H.K. (Hakushi Kim) and T.K. wrote the original manuscript draft; N.N., H.K. (Hiroyuki Kobayashi), and A.M. contributed to the writing, editing, and revising of the manuscript. N.N., H.K. (Hiroyuki Kobayashi), and A.M. supervised the project.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Inamura K. Renal cell tumors: Understanding their molecular pathological epidemiology and the 2016 WHO classification. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017;18:2195. doi: 10.3390/ijms18102195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schraml P., Struckmann K., Hatz F., Sonnet S., Kully C., Gasser T., Sauter G., Mihatsch M.J., Moch H. VHL mutations and their correlation with tumour cell proliferation, microvessel density, and patient prognosis in clear cell renal cell carcinoma. J. Pathol. 2002;196:186–193. doi: 10.1002/path.1034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Moch H., Humphrey P.A., Ulbright T.M., Reuter V.E. WHO Classification of Tumours. 4th ed. Volume 8 WHO Press; Geneva, Switzerland: 2016. WHO classification of tumours of the urinary system and male genital organs. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Speicher M.R., Schoell B., du Manoir S., Schrock E., Ried T., Cremer T., Störkel S., Kovacs A., Kovacs G. Specific loss of chromosomes 1, 2, 6, 10, 13, 17, and 21 in chromophobe renal cell carcinomas revealed by comparative genomic hybridization. Am. J. Pathol. 1994;145:356–364. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brunelli M., Eble J.N., Zhang S., Martignoni G., Delahunt B., Cheng L. Eosinophilic and classic chromophobe renal cell carcinomas have similar frequent losses of multiple chromosomes from among chromosomes 1, 2, 6, 10, and 17, and this pattern of genetic abnormality is not present in renal oncocytoma. Mod. Pathol. 2005;18:161–169. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3800286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Varela I., Tarpey P., Raine K., Huang D., Ong C.K., Stephens P., Davies H., Jones D., Lin M.L., Teague J., et al. Exome sequencing identifies frequent mutation of the SWI/SNF complex gene PBRM1 in renal carcinoma. Nature. 2011;469:539–542. doi: 10.1038/nature09639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dalgliesh G.L., Furge K., Greenman C., Chen L., Bignell G., Butler A., Davies H., Edkins S., Hardy C., Latimer C., et al. Systematic sequencing of renal carcinoma reveals inactivation of histone modifying genes. Nature. 2010;463:360–363. doi: 10.1038/nature08672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sato Y., Yoshizato T., Shiraishi Y., Maekawa S., Okuno Y., Kamura T., Shimamura T., Sato-Otsubo A., Nagae G., Suzuki H., et al. Integrated molecular analysis of clear-cell renal cell carcinoma. Nat. Genet. 2013;45:860–867. doi: 10.1038/ng.2699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Larman T.C., De Palma S.R., Hadjipanayis A.G., The Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network. Protopopov A., Zhang J., Gabriel S.B., Chin L., Seidman C.E., Kucherlapati R., et al. Spectrum of somatic mitochondrial mutations in five cancers. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2012;109:14087–14091. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1211502109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lata S., Neeru S., Neelam P., Sameer B., Seema S., Tapas C.N., Seema K. Mutational analysis of the mitochondrial DNA displacement-loop region in human retinoblastoma with patient outcome. Pathol. Oncol. Res. 2018;25:503–512. doi: 10.1007/s12253-018-0391-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lian L., Rui X., Jiantao C., Wenmei L., Youyong L. Investigation of frequent somatic mutations of MTND5 gene in gastric cancer cell lines and tissues. Mitochondrial DNA B. 2018;3:1002–1008. doi: 10.1080/23802359.2018.1501287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kim H., Komiyama T., Inomoto C., Kamiguchi H., Kajiwara H., Kobayashi H., Nakamura N., Terachi T. Mutations in the mitochondrial ND1 gene are associated with postoperative prognosis of localized renal cell carcinoma. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2016;17:2049. doi: 10.3390/ijms17122049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Felix A.U., Felipe M., Alenka L., Cesar C. The mitochondrial complex(I)ty of cancer. Front. Oncol. 2017;7 doi: 10.3389/fonc.2017.00118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Taanman J.W. The mitochondrial genome: Structure, transcription, translation and replication. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1999;1410:103–123. doi: 10.1016/S0005-2728(98)00161-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sanchez-Cespedes M., Parrella P., Nomoto S., Cohen D., Xiao Y., Esteller M., Jeronimo C., Jordan R.C., Nicol T., Koch W.M., et al. Identification of a mononucleotide repeat as a major target for mitochondrial DNA alterations in human tumors. Cancer Res. 2001;61:7015–7019. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yoneyama H., Hara T., Kato Y., Yamori T., Matsuura E.T., Koike K. Nucleotide sequence variation is frequent in the mitochondrial DNA displacement loop region of individual human tumor cells. Mol. Cancer Res. 2005;3:14–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nishikawa M., Nishiguchi S., Shiomi S., Tamori A., Koh N., Takeda T., Kubo S., Hirohashi K., Kinoshita H., Sato E., et al. Somatic mutation of mitochondrial DNA in cancerous and noncancerous liver tissue in individuals with hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Res. 2001;61:1843–1845. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Boaventura P., Pereira D., Mendes A., Batista R., da Silva A.F., Guimaraes I., Honavar M., Teixeira-Gomes J., Lopes J.M., Maximo V., et al. Mitochondrial D310 D-loop instability and histological subtypes in radiation-induced cutaneous basal cell carcinomas. J. Dermatol. Sci. 2014;73:31–39. doi: 10.1016/j.jdermsci.2013.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Duberow D.P., Brait M., Hoque M.O., Theodorescu D., Sidransky D., Dasgupta S., Mathies R.A. High-performance detection of somatic D-loop mutation in urothelial cell carcinoma patients by polymorphism ratio sequencing. J. Mol. Med. 2016;94:1015–1024. doi: 10.1007/s00109-016-1407-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Akouchekian M., Houshmand M., Hemati S., Ansaripour M., Shafa M. High rate of mutation in mitochondrial DNA displacement loop region in human colorectal cancer. Dis. Colon Rectum. 2009;52:526–530. doi: 10.1007/DCR.0b013e31819acb99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bai Y., Guo Z., Xu J., Liu S., Zhang J., Cui L., Zhang H., Zhang S. Single nucleotide polymorphisms in the D-loop region of mitochondrial DNA is associated with renal cell carcinoma outcome. Mitochondrial DNA. 2015;26:224–226. doi: 10.3109/19401736.2013.825772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tamura K., Stecher G., Peterson D., Filipski A., Kumar S. MEGA6: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis version 6.0. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2013;30:2725–2729. doi: 10.1093/molbev/mst197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kanda Y. Investigation of the freely available easy-to-use software “EZR” for medical statistics. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2013;48:452–458. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2012.244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Uno H., Cai T., Pencina M.J., D’Agostino R.B., Wei L.J. On the C-statistics for evaluating overall adequacy of risk prediction procedures with censored survival data. Stat. Med. 2011;30:1105–1117. doi: 10.1002/sim.4154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hopkins J.F., Sabelnykova V.Y., Weischenfeldt J., Simon R., Aguiar J.A., Alkallas R., Heisler L.E., Zhang J., Watson J.D., Chua M.L.K., et al. Mitochondrial mutations drive prostate cancer aggression. Nat. Commun. 2017;8:656. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-00377-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lin C.S., Chang S.C., Ou L.H., Chen C.M., Hsieh S.S., Chung Y.P., King K.L., Lin S.L., Wei Y.H. Mitochondrial DNA alterations correlate with the pathological status and the immunological ER, PR, HER-2/neu, p53 and Ki-67 expression in breast invasive ductal carcinoma. Oncol. Rep. 2015;33:2924–2934. doi: 10.3892/or.2015.3887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Motzer R.J. NCCN Guidelines®. NCCN; Pennsylvania, PA, USA: 2019. NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Powles T., Albiges L., Staehler M., Bensalah K., Dabestani S., Giles R.H., Hofmann F., Hora M., Kuczyk M.A., Lam T.B., et al. Updated European Association of Urology Guidelines Recommendations for the Treatment of First-line Metastatic Clear Cell Renal Cancer. Eur. Urol. 2018;73:311–315. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2017.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rizvi N.A., Hellmann M.D., Snyder A., Kvistborg P., Makarov V., Havel J.J., Lee W., Yuan J., Wong P., Ho T.S., et al. Cancer immunology. Mutational landscape determines sensitivity to PD-1 blockade in non-small cell lung cancer. Science. 2015;348:124–128. doi: 10.1126/science.aaa1348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Johnson D.B., Frampton G.M., Rioth M.J., Yusko E., Xu Y., Guo X., Ennis R.C., Fabrizio D., Chalmers Z.R., Greenbowe J., et al. Targeted next generation sequencing identifies markers of response to PD-1 blockade. Cancer Immunol. Res. 2016;4:959–967. doi: 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-16-0143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Samstein R.M., Lee C.H., Shoushtari A.N., Hellmann M.D., Shen R., Janjigian Y.Y., Barron D.A., Zehir A., Jordan E.J., Omuro A., et al. Tumor mutational load predicts survival after immunotherapy across multiple cancer types. Nat. Genet. 2019;51:202–206. doi: 10.1038/s41588-018-0312-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lin J.C., Wang C.C., Jiang R.S., Wang W.Y., Liu S.A. Impact of somatic mutations in the D-loop of mitochondrial DNA on the survival of oral squamous cell carcinoma patients. PLoS ONE. 2015;10:e0124322. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0124322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lin C.S., Chang S.C., Wang L.S., Chou T.Y., Hsu W.H., Wu Y.C., Wei Y.H. The role of mitochondrial DNA alterations in esophageal squamous cell carcinomas. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2010;139:189–197. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2009.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bai Y., Guo Z., Xu J., Zhang J., Cui L., Zhang H., Zhang S. The 9-bp deletion at position 8272 in region V of mitochondrial DNA is associated with renal cell carcinoma outcome. Mitochondrial DNA A DNA Mapp. Seq. Anal. 2016;27:1973–1975. doi: 10.3109/19401736.2014.971312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]