Abstract

Background

Sodium zirconium cyclosilicate (SZC; formerly ZS-9) is a selective potassium (K+) binder for treatment of hyperkalemia. An open-label extension (OLE) of the HARMONIZE study evaluated efficacy and safety of SZC for ≤11 months.

Methods

Patients from HARMONIZE with point-of-care device i-STAT K+ 3.5–6.2 mmol/L received once-daily SZC 5–10 g for ≤337 days. End points included achievement of mean serum K+ ≤5.1 mmol/L (primary) or ≤5.5 mmol/L (secondary).

Results

Of 123 patients who entered the extension (mean serum K+ 4.8 mmol/L), 79 (64.2%) completed the study. The median daily dose of SZC was 10 g (range 2.5–15 g). The primary end point was achieved by 88.3% of patients, and 100% achieved the secondary end point. SZC was well tolerated with no new safety concerns.

Conclusion

In the HARMONIZE OLE, most patients maintained mean serum K+ within the normokalemic range for ≤11 months during ongoing SZC treatment.

Keywords: Extension, HARMONIZE, Hyperkalemia, Sodium zirconium cyclosilicate

Introduction

Hyperkalemia (serum potassium [K+] >5.0 or >5.5 mmol/L) [1, 2] has an adverse prognosis, and severe hyperkalemia can be life threatening [3]. Oral K+ binders, which lower serum K+ by binding K+ in the colon, reducing K+ absorption and increasing K+ fecal excretion [4], are potential therapeutic options for long-term hyperkalemia management. Sodium zirconium cyclosilicate (SZC; formerly ZS-9) is a K+ binder approved for the treatment of hyperkalemia in the United States and Europe [5, 6, 7]. In clinical trials, including HARMONIZE [8], SZC reduced serum K+ to within the normokalemic range within 48 h, which was maintained over 29 days in most patients [9, 10, 11]. The long-term efficacy and safety of SZC in patients with hyperkalemia (n = 746) have also been examined in a 12-month, open-label study [11]. Here, we evaluate the efficacy and safety of open-label SZC up to 11 months in the extension phase of HARMONIZE.

Materials and Methods

Study Design

Details of the HARMONIZE study (NCT02088073) have been reported previously [8]. Briefly, outpatients with hyperkalemia entered an open-label correction phase (HARMONIZE-CP), during which they received SZC 10 g 3 times daily (TID), and were subsequently randomized to placebo or SZC 5, 10, or 15 g once daily (QD) during a maintenance phase (HARMONIZE-MP). The current single-arm open-label extension (OLE; NCT021070920) was conducted at 30 sites across Australia, South Africa, and the United States (online suppl. Table S1; for all online suppl. material, see www.karger.com/doi/10.1159/000504078). The study was completed in accordance with US Title 21 CFR, the ICH E6 (R1) Guidelines of Good Clinical Practice, and the Declaration of Helsinki.

Patients were eligible for the OLE if they (1) completed HARMONIZE-MP and had plasma K+ 3.5–6.2 mmol/L by a point-of-care device (i-STAT, Abbott Point of Care) or (2) discontinued during HARMONIZE-MP because of hypo- or hyperkalemia and had mean i-STAT K+ 3.5–6.2 mmol/L from 2 consecutive measurements at 0 and 60 min on day 1 of the OLE. All patients provided written consent. Full inclusion and exclusion criteria are shown in online supplementary Table S2.

On day 1 of the OLE, patients with i-STAT K+ >5.5 mmol/L entered the extension correction phase (Extension-CP) where they received SZC 10 g TID for 24 (3 doses) or 48 h (6 doses), depending on their daily i-STAT K+. Patients with i-STAT K+ 3.5–5.5 mmol/L immediately entered the extension maintenance phase (Extension-MP) and began SZC 10 g QD (online suppl. Fig. S1). No dietary restrictions were mandated. Concomitant medications, including renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system inhibitors (RAASis) and diuretics, were not restricted. Details of protocol-mandated reasons for discontinuation are in the online supplementary Methods.

Study Drug Administration

SZC was administered orally with meals (Extension-CP) or just before breakfast (Extension-MP) or at the clinic on scheduled clinic visit days (online suppl. Fig. S2A). During the Extension-MP, SZC was initiated at 10 g QD and titrated in 5-g increments or decrements to maintain i-STAT K+ 3.5–5.0 mmol/L (minimum 5 g every other day; maximum 15 g QD; online suppl. Fig. S2B).

Laboratory Assessments

Fasting K+ in whole blood was measured via 2 methods: (1) i-STAT was used to measure plasma K+ to determine study eligibility, continuation from the Extension-CP to the Extension-MP, and SZC dose titrations and (2) central-laboratory serum K+ was measured to assess efficacy. Measurement schedules are shown in online supplementary Figure S2A. Details of additional assessments are in the online supplementary Methods.

Study End Points

The primary and secondary efficacy end points were the proportion of patients achieving mean serum K+ ≤5.1 and ≤5.5 mmol/L, respectively, during Extension-MP days 8–337. Additional efficacy end points included the proportions of patients with normokalemia (serum K+ 3.5–5.0 mmol/L), hypokalemia (serum K+ <3.5 mmol/L), or hyperkalemia (>5.0 mmol/L) at each scheduled visit. Details of other efficacy end points are in the online supplementary Methods. Safety end points included solicited adverse events (AEs; by Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities version 17.0 preferred terms and Standardised Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities Queries for hemodynamic edema, effusions, and fluid overload [SMQ edema; spontaneously reported by investigators]). Modifications in SZC dosing were recorded.

Statistical Considerations

Safety outcomes were evaluated in the OLE safety population (patients who received ≥1 SZC dose with any post-Extension-CP baseline safety data). Efficacy outcomes were evaluated in the intent-to-treat population (patients in the safety population with any post-Extension-MP serum K+ measurements). Extension-CP outcomes were evaluated only if >20 patients required treatment with Extension-CP dosing.

The primary end point was analyzed using logistic regression, including fixed effects of estimated glomerular filtration rate at HARMONIZE-CP baseline and serum K+ level at both HARMONIZE-CP and at Extension-MP baselines and age category (<55, 55–64, and ≥65 years), RAASi use, chronic kidney disease (CKD), heart failure, and diabetes status at HARMONIZE-CP baseline. Additionally, whether the observed proportion of patients achieving the primary and secondary end points was significantly higher than the expected proportion of 50 or 60%, respectively, was evaluated using an exact binomial test. A longitudinal mixed model was used to derive the back-transformed geometric least squares mean serum K+ values through days 8–337. Descriptive statistics expressed the nominal and percent change in serum K+ and serum aldosterone from HARMONIZE-CP and Extension-MP baselines, with significance of changes evaluated using paired t tests. Full details, including sample-size calculations, are in the online supplementary Methods.

Results

Study Population

Overall, 215 patients were eligible for the OLE, including 208 patients who completed HARMONIZE-MP and 7 of 20 patients who withdrew from HARMONIZE because of hypokalemia (n = 6) or hyperkalemia (n = 14). Of these 215 patients, 123 entered the OLE (online suppl. Fig. S3 for reasons for exclusion). Forty-eight patients had previously received placebo, 21 SZC 5 g QD, 21 SZC 10 g QD, and 33 SZC 15 g QD in HARMONIZE-MP. At HARMONIZE-MP end, 121 patients (98%) entered the Extension-MP on SZC 10 g QD, and 2 patients initially entered the Extension-CP on SZC 10 g TID. These 2 patients each achieved normokalemia within 1 day and subsequently entered the Extension-MP. Extension-CP data for these 2 patients were not summarized; however, these patients were included in Extension-MP analyses. Overall, 79 patients (64.2%) completed the 11-month OLE and 44 (35.8%) discontinued therapy before study completion (online suppl. Fig. S3). Most patients in the intent-to-treat population were male, white, had CKD and diabetes, and received concomitant RAASis (Table 1); 67 patients (55.4%) had serum K+ ≥5.5 mmol/L at HARMONIZE-CP baseline.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics and demographics as measured at HARMONIZE-CP and extension-MP base lines for patients who entered the extension-MP (ITT population)

| HARMONIZE-CP baseline (n = 121) | Extension-MP baseline (n = 121) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age, years, mean (SD) | 63.7 (12.3) | 63.7 (12.3) |

| Gender, male, n (%) | 70 (57.9) | 70 (57.9) |

| Race, n (%) | ||

| White | 107 (88.4) | 107 (88.4) |

| Black/African American | 11 (9.1) | 11 (9.1) |

| Asian | 2 (1.7) | 2 (1.7) |

| Other | 1 (0.8) | 1 (0.8) |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | ||

| Hispanic | 48 (39.7) | 48 (39.7) |

| Non-Hispanic | 73 (60.3) | 73 (60.3) |

| Geographic region, n (%) | ||

| United States | 94 (77.7) | 94 (77.7) |

| Australia | 11 (9.1) | 11 (9.1) |

| South Africa | 16 (13.2) | 16 (13.2) |

| Weight, kg, mean (SD) | 88.7 (22.0) | 89.0 (22.1) |

| BP, mm Hg, mean (95% CI) | ||

| Systolic | 139.4 (135.7–143.2) | 137.9 (134.8–141.0) |

| Diastolic | 79.3 (77.3–81.2) | 78.1 (76.5–79.7) |

| Serum K+, mmol/L, mean (min–max) | 5.6 (4.8–6.6) | 4.8 (3.6–6.6) |

| Serum K+, mmol/L, n (%) | ||

| <5.5 | 54 (44.6) | 108 (89.3) |

| 5.5 to <6.0 | 53 (43.8) | 11 (9.1) |

| ≥6.0 | 14 (11.6) | 2 (1.7) |

| i-STAT K+, mmol/L, mean (min–max) | 5.4 (5.1–6.3) | 4.5 (3.5–5.5) |

| i-STAT K+, mmol/L, n (%) | ||

| <5.5 | 67 (55.4) | 118 (97.5) |

| 5.5 to <6.0 | 50 (41.3) | 3 (2.5) |

| ≥6.0 | 4 (3.3) | 0 (0.0) |

| eGFR, mL/min/1.73 m2, mean (SD) | 46.2 (31.8) | 47.0 (32.6) |

| eGFR, mL/min/1.73 m2, n (%) | ||

| <15 | 18 (14.9) | 14 (11.6) |

| 15 to <30 | 25 (20.7) | 25 (20.7) |

| 30 to <45 | 25 (20.7) | 32 (26.4) |

| 45 to <60 | 22 (18.2) | 18 (14.9) |

| ≥60 | 31 (25.6) | 32 (26.4) |

| Serum bicarbonate, mmol/L, mean (SD) | 23.0 (3.9) | 24.1 (3.8) |

| Serum bicarbonate, mmol/L, n (%) | ||

| <22 | 42 (34.7) | 27 (22.3) |

| ≥22 | 79 (65.3) | 94 (77.7) |

| Serum urea, mmol/La, mean (SD) | 13.2 (8.2) | 13.0 (8.7) |

| Aldosterone, nmol/Lb, mean (SD) | 0.28 (0.27) | 0.18 (0.18) |

| Plasma BNP, pg/mLc, mean (SD) | 129.9 (159.0) | 145.6 (155.0) |

| Medical history, n (%)d | ||

| CKD | 74 (61.2) | 78 (64.5) |

| HF | 15 (12.4) | 16 (13.2) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 80 (66.1) | 81 (66.9) |

| Concomitant medication use, n (%) | ||

| RAASi therapies | 82 (67.8) | 83 (68.6) |

| ACE inhibitors | 58 (47.9) | 58 (47.9) |

| ARBs | 27 (22.3) | 29 (24.0) |

| MRAs | 5 (4.1) | 6 (5.0) |

| Diuretic usee | 47 (38.8) | 51 (42.1) |

| Loop | 35 (28.9) | 42 (34.7) |

| Thiazide | 7 (5.8) | 7 (5.8) |

| Other | 3 (2.5) | 3 (2.5) |

| Calcium-channel blockers | 43 (35.5) | 49 (40.5) |

| Sodium bicarbonatef | 10 (8.3) | 10 (8.3) |

Normal range 2.9–8.2 mmol/L.

North American sites only. n = 94 (HARMONIZE-CP baseline) and n = 93 (Extension-MP baseline). Normal range: 0.11–0.86 nmol/L.

North American sites only. n = 93 (HARMONIZE-CP baseline) and n = 92 (Extension-MP baseline). Upper limit of normal: 100 pg/mL.

Defined by SMQ narrow terms.

2 patients (HARMONIZE-CP baseline) and 1 patient (Extension-MP baseline) received both “other” diuretics and aldosterone antagonists and were therefore counted in both the RAASi and diuretic categories.

No patients commenced oral sodium bicarbonate during the Extension-MP.

ACE, angiotensin-converting enzyme; ARB, angiotensin II receptor blocker; BNP, brain natriuretic peptide; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; Extension-MP, extension maintenance phase; HARMONIZE-CP, HARMONIZE correction phase; ITT, intent to treat; K+, potassium; max, maximum; min, minimum; MRA, mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist; RAASi, renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system inhibitor; SMQ, Standardised Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities Query; BP, blood pressure; CKD, chronic kidney disease; HF, heart failure.

Efficacy

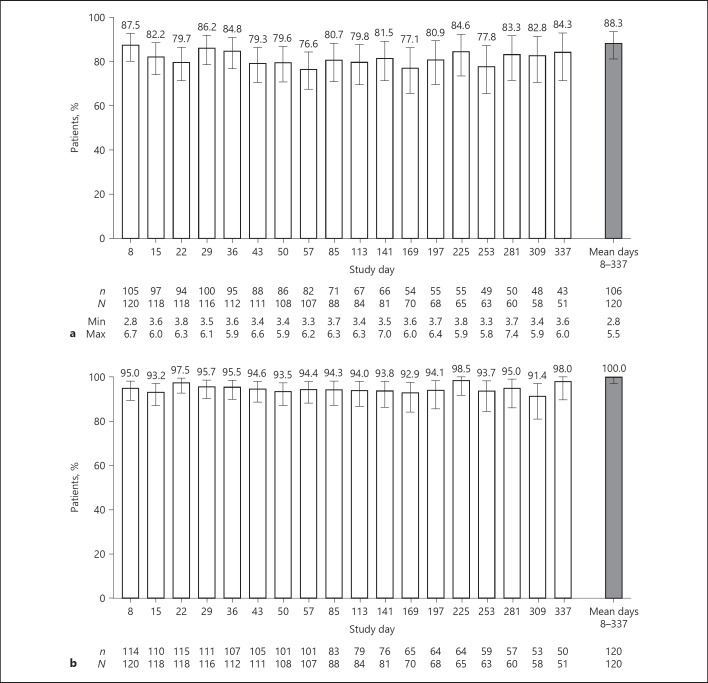

Mean (SD) serum K+ at Extension-MP baseline was 4.8 (0.5) mmol/L. Across days 8–337, the adjusted proportion of patients achieving mean serum K+ ≤5.1 mmol/L (primary end point) was 92.8% (95% CI 84.7–96.8%); the unadjusted proportion was 88.3% (95% CI 81.2–93.5%; p < 0.001 vs. the expected 50%). Mean serum K+ ≤5.1 mmol/L was achieved and maintained by 76.6–87.5% of patients across study visits (Fig. 1a). All patients achieved the secondary end point (mean serum K+ ≤5.5 mmol/L) through days 8–337 (unadjusted proportion 100.0% [95% CI 97.0–100.0%]; p < 0.001 vs. the expected 60%). Across study visits, 91.4–98.5% of patients had serum K+ ≤5.5 mmol/L (Fig. 1b). Across days 8–337, 79.2% (95% CI 70.8–86.0%) of patients achieved normokalemic serum K+ levels.

Fig. 1.

Proportion of patients in the intent-to-treat population with mean serum K+ (a) ≤5.1 mmol/L and (b) ≤5.5 mmol/L with SZC by study visit and overall (days 8–337) in the maintenance phase. Error bars represent 95% CIs. Gray bar represents the proportion of patients across all visits in the maintenance phase. n, the number of patients meeting serum K+ threshold; N, the total number of evaluable patients; Min and Max, minimum and maximum serum K+ values, respectively, in mmol/L. K+, potassium.

The proportion of patients with any hypokalemia ranged from 0 to 1.9% across study visits; no hypokalemia-related echocardiogram abnormalities were reported. One patient had severe hypokalemia (K+ <3.0 mmol/L; actual serum K+ value 2.8 mmol/L) and withdrew from the study after 8 days of SZC 10 g QD. Across days 8–337, 20.0% (95% CI 13.3–28.3%) of patients had mean serum K+ in the hyperkalemic range, with 15.0–28.8% of patients having serum K+ >5.0 mmol/L at each study visit.

Mean serum K+ was within the normokalemic range through days 8–337, ranging from 4.5 to 4.7 mmol/L (online suppl. Fig. S4), and serum K+ values appeared normally distributed (online suppl. Fig. S5). Using a longitudinal mixed model, the least squares mean serum K+ was 4.7 mmol/L (95% CI 4.6–4.7 mmol/L) through days 8–337. After SZC discontinuation, mean serum K+ increased significantly from 4.6 mmol/L on day 337 to 5.0 mmol/L at study end (p < 0.001); serum K+ levels were 5.0–5.5 mmol/L in 20.7% of patients and >5.5 mmol/L in 17.4% at the end-of-study visit. Mean decreases in serum K+ from HARMONIZE-CP baseline were observed at every time point during the OLE, ranging from −1.0 to −0.8 mmol/L (−17.8 to −14.4%; p ≤ 0.001 for all), while decreases in serum K+ from Extension-MP baseline were generally small (≤0.2 mmol/L; ≤2.9%).

Serum aldosterone initially decreased from HARMONIZE-CP baseline to day 29 (mean change, −0.12 nmol/L; p < 0.001) and stabilized over time (online suppl. Fig. S6A). Normal serum aldosterone (range 0.11–0.86 nmol/L) was observed in 43.2% of patients by day 29, 84.7% by day 141, and remained within this range across the remaining study visits (range 73.0–84.2%). Sustained increases in serum bicarbonate were observed during the Extension-MP (online suppl. Fig. S6B). Mean serum bicarbonate increased from HARMONIZE-CP baseline (23.0 mmol/L [95% CI 22.3–23.7 mmol/L]) to Extension-MP baseline (24.1 mmol/L [95% CI 23.4–24.8 mmol/L]) and was maintained throughout the OLE (24.1 mmol/L at day 337 [95% CI 23.0–25.2 mmol/L]). After SZC cessation, mean serum bicarbonate was 23.6 mmol/L (95% CI 22.8–24.4 mmol/L).

Of the 83 patients receiving RAASis at Extension-MP baseline, 65 (78.3%) continued a stable dose through days 8–337, 7 (8.4%) increased the dose, 3 (3.6%) added another RAASi, 3 (3.6%) had multiple dose decreases and increases, 2 (2.4%) switched RAASis, and 3 (3.6%) discontinued RAASis. RAASis were initiated in 4 patients who were not receiving RAASis at Extension-MP baseline.

Dosing

During the OLE, most patients received SZC 10 g QD (online suppl. Fig. S7A), and the median daily dose of SZC was 10.0 g (range 2.5–15.0 g). Mean (SD) treatment duration was 212.9 (129.1) days. The mean SZC dose was 10 g QD in 90 of 123 patients (73.2%), >10 g in 16 (13.0%), and <10 g in 17 (13.8%). Thirty-two patients (26.0%) had ≥1 dose modification, 29 (90.6%) required 1 dose modification, and 3 (9.4%) required 2 dose modifications (online suppl. Fig. S7B).

Safety

Overall, AEs were reported by 82 patients (66.7%); 23 (18.7%) reported gastrointestinal disorders, the most common being constipation (5.7%) and nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea (3.3% for each). AEs reported in ≥5% of patients were hypertension (12.2%), urinary tract infection (8.9%), and peripheral edema (8.1%; online suppl. Table S3). In 15 patients with hypertension, severity was either mild (n = 7; 46.7%) or moderate (n = 8; 53.3%); only 1 case was considered by the investigator to be related to SZC. No patients discontinued SZC because of hypertension.

Sixteen patients (13.0%) reported 17 SMQ edema events; 11 of whom had significant risk factors for fluid overload-related events, including history of heart failure, diastolic dysfunction, CKD, edema, lymphedema, or venous insufficiency. One SMQ edema event was classified as serious (pulmonary edema) and one was considered severe in intensity (peripheral edema), with both occurring in the context of comorbid congestive cardiac failure, hypertension and chronic renal failure. Three events (n = 1 each of mild peripheral edema, moderate pulmonary edema, and moderate peripheral edema) were considered possibly related to SZC; most (76.5%) were reported resolved or resolving, and 64.7% required treatment. No edema event led to discontinuation.

Serious AEs (SAEs) developed in 24 patients (19.5%); the most common were chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, congestive cardiac failure, pneumonia, and urinary tract infection (n = 2 for each; online suppl. Table S3). Six patients (4.9%) discontinued SZC because of SAEs, including cardiac failure, acute myocardial infarction, hyperkalemia, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, localized infection, and diabetic foot infection. No SAEs were considered related to SZC.

AEs led to discontinuation in 11 patients (online suppl. Table S3); these were severe in 6 patients, moderate in 3, and mild in 2. Three patients discontinued because of nonserious AEs considered possibly related to SZC, including QT interval prolongation (n = 2; neither patient had hypokalemia) and drug hypersensitivity (n = 1). No deaths occurred. No clinically meaningful changes in either weight (online suppl. Fig. S8A) or blood pressure (BP; online suppl. Fig. S8B) were observed. However, a decrease in BP from HARMONIZE-CP baseline (mean 139.4/79.4 mm Hg) was observed at the end-of-study visit (mean [SD] change, −6.8 [21.4]/–2.6 [10.4] mm Hg).

Discussion

The HARMONIZE study demonstrated rapid attainment of normokalemia in most patients following SZC 10 g TID for 48 h, which was maintained for up to 29 days with SZC at 5–15 g QD [8]. In this long-term OLE of HARMONIZE, normokalemia was maintained for up to 11 months during ongoing SZC QD treatment in 79% of patients, and treatment was generally well tolerated. RAASi use either remained stable or increased for most patients (90.3%), and few patients (3.6%) discontinued RAASis.

Results from this OLE contribute to the growing body of evidence, involving 1,175 patients, for the clinical utility of the newer K+ binders, such as SZC and patiromer, for the long-term management of hyperkalemia. In the 52-week open-label AMETHYST-DN study among patients with hyperkalemia and diabetic kidney disease receiving RAASis and treated with patiromer (n = 306), mean serum K+ (˜4.6 mmol/L), and proportions maintaining normokalemia (˜77 to 95%) at each study visit from 4 through 52 weeks [12] were similar to the findings with SZC in the current OLE (n = 123) and in another larger 12-month study (n = 746) [11].

Changes in serum aldosterone in the current OLE were consistent with the expected response to a decrease in serum K+ [1]. The initial decrease in serum aldosterone from HARMONIZE-CP baseline to day 29 mirrored the reduction in serum K+ during this period and led to more patients achieving normal aldosterone. Notably, serum aldosterone was subsequently maintained in the normal range with continued SZC treatment, which may have positively affected the observed decrease in end-of-study BP. Increases in serum bicarbonate previously observed in HARMONIZE [8] were also maintained throughout the OLE. Serum bicarbonate increases may be clinically relevant in patients with CKD because low serum bicarbonate may increase the risk of CKD progression and mortality [13, 14, 15].

SZC was generally well tolerated in this OLE, and no new safety concerns were identified. Although edema is an acknowledged potential adverse reaction to SZC [5, 6] and some sodium absorption occurs with SZC therapy, the open-label design of the extension and the fact that 11 of the 16 patients with edema had significant baseline risk factors for fluid overload-related events precludes firm conclusions on causality.

This study has several limitations, including its open-label design and lack of control group and the exclusion of 92 patients from the OLE (77 of whom for study drug unavailability). In addition, follow-up after the last SZC dose was only 7 ± 1 days, at which time total body K+ would likely not have returned to baseline. Last, although Black/African Americans experience a high burden of CKD, they were underrepresented in this study (9.1%) relative to the study center populations (˜23%); however, a similar limitation extends to other trials of novel potassium binders (e.g., patients enrolled in AMETHYST-DN were exclusively white).

Conclusions

In this long-term OLE of HARMONIZE among patients with hyperkalemia, normokalemia was maintained during ongoing SZC QD treatment for up to 11 months. SZC was well tolerated, with no new safety signals, and RAASi use remained stable or increased in most patients.

Statement of Ethics

The study protocol, all applicable amendments, and informed consent documentation were reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board or independent Ethics Committee at each of the investigational centers participated in the study. Signed informed consent was obtained from all the patients prior to study start.

Disclosure Statement

S.D.R. has received travel fees for investigator meetings and honoraria for serving on advisory boards for AstraZeneca, Vifor Pharma, and ZS Pharma. B.S.S. has received grant support and has served as a consultant for AstraZeneca and ZS Pharma. E.V.L. is a subinvestigator with Research by Design and has received grant support from ZS Pharma. B.S. is a former employee of AstraZeneca, PLC. D.K.P. has received travel fees for investigator meetings and honoraria for serving on advisory boards for AstraZeneca and ZS Pharma. A.A-S. is an employee of AstraZeneca. M.K. has served as a consultant and advisory board member to ZS Pharma and AstraZeneca, was an investigator for clinical trials sponsored by ZS Pharma, and has received research grant support from AstraZeneca.

Funding Source

The study was initiated and performed by ZS Pharma, Inc., a subsidiary of AstraZeneca. Funding for editorial support was provided by AstraZeneca.

Author Contributions

S.D.R., B.S.S., E.V.L., D.K.P., and M.K. enrolled study participants. B.S.S. contributed to conception and design of the study and analyzed and interpreted data. S.D.R., B.S.S., E.V.L., B.S., D.K.P., A.A-S., and M.K. contributed to writing and revising the manuscript. All authors reviewed the manuscript and approved the final version for publication.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary data

Acknowledgments

We thank the investigators and patients who participated in this study. We also thank Philip T. Lavin and J. Han for the contributions to the study design and analyses. Sarah Greig, PhD, and Julian Martins, MA, of inScience Communications, Springer Healthcare (Philadelphia, PA, USA) provided editorial support funded by AstraZeneca. Authors did not receive compensation for their contribution to this publication.

References

- 1.Kovesdy CP, Appel LJ, Grams ME, Gutekunst L, McCullough PA, Palmer BF, et al. Potassium homeostasis in health and disease a scientific workshop cosponsored by the National Kidney Foundation and the American Society of Hypertension. Am J Kidney Dis. 2017 Dec;70((6)):844–58. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2017.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rosano GM, Tamargo J, Kjeldsen KP, Lainscak M, Agewall S, Anker SD, et al. Expert consensus document on the management of hyperkalaemia in patients with cardiovascular disease treated with renin angiotensin aldosterone system inhibitors coordinated by the Working Group on Cardiovascular Pharmacotherapy of the European Society of Cardiology. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Pharmacother. 2018 Jul;4((3)):180–8. doi: 10.1093/ehjcvp/pvy015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chen Y, Chang AR, McAdams DeMarco MA, Inker LA, Matsushita K, Ballew SH, et al. Serum potassium and kidney outcomes in the atherosclerosis risk in communities study. Mayo Clin Proc. 2016 Oct;91((10)):1403–12. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2016.05.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chaitman M, Dixit D, Bridgeman MB. Potassium-binding agents for the clinical management of hyperkalemia. P T. 2016 Jan;41((1)):43–50. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.US Food and Drug Administration Lokelma (sodium zirconium cyclosilicate) prescribing information. Available from: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2018/207078s000lbl.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 6.European Medicines Agency Lokelma summary of product characteristics. Available from: http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/EPAR_-_Product_Information/human/004029/WC500246774.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stavros F, Yang A, Leon A, Nuttall M, Rasmussen HS. Characterization of structure and function of ZS-9 a K+ selective ion trap. PLoS One. 2014 Dec;9((12)):e114686. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0114686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kosiborod M, Rasmussen HS, Lavin P, Qunibi WY, Spinowitz B, Packham D, et al. Effect of sodium zirconium cyclosilicate on potassium lowering for 28 days among outpatients with hyperkalemia the HARMONIZE randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2014 Dec;312((21)):2223–33. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.15688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ash SR, Singh B, Lavin PT, Stavros F, Rasmussen HS. A phase 2 study on the treatment of hyperkalemia in patients with chronic kidney disease suggests that the selective potassium trap is safe and efficient. Kidney Int. 2015 Aug;88((2)):404–11. doi: 10.1038/ki.2014.382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Packham DK, Rasmussen HS, Lavin PT, El-Shahawy MA, Roger SD, Block G, et al. Sodium zirconium cyclosilicate in hyperkalemia. N Engl J Med. 2015 Jan;372((3)):222–231. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1411487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Spinowitz BS, Fishbane S, Pergola PE, Roger SD, Lerma EV, Butler J, et al. ZS-005 Study Investigators Sodium zirconium cyclosilicate among individuals with hyperkalemia a 12-month phase 3 study. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2019 Jun;14((6)):798–809. doi: 10.2215/CJN.12651018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bakris GL, Pitt B, Weir MR, Freeman MW, Mayo MR, Garza D, et al. AMETHYST-DN Investigators Effect of Patiromer on Serum Potassium Level in Patients With Hyperkalemia and Diabetic Kidney Disease The AMETHYST-DN Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2015 Jul;314((2)):151–61. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.7446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dobre M, Yang W, Chen J, Drawz P, Hamm LL, Horwitz E, et al. CRIC Investigators Association of serum bicarbonate with risk of renal and cardiovascular outcomes in CKD a report from the Chronic Renal Insufficiency Cohort (CRIC) study. Am J Kidney Dis. 2013 Oct;62((4)):670–8. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2013.01.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Goldenstein L, Driver TH, Fried LF, Rifkin DE, Patel KV, Yenchek RH, et al. Health ABC Study Investigators Serum bicarbonate concentrations and kidney disease progression in community-living elders the Health, Aging, and Body Composition (Health ABC) Study. Am J Kidney Dis. 2014 Oct;64((4)):542–9. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2014.05.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kovesdy CP, Anderson JE, Kalantar-Zadeh K. Association of serum bicarbonate levels with mortality in patients with non-dialysis-dependent CKD. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2009 Apr;24((4)):1232–7. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfn633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary data