Abstract

Background: Noninvasive prenatal screening (NIPS) utilization has grown dramatically and is increasingly offered to the general population by nongenetic specialists. Web-based technologies and telegenetic services offer potential solutions for efficient results delivery and genetic counseling.

Introduction: All major guidelines recommend patients with both negative and positive results be counseled. The main objective of this study was to quantify patient utilization, motivation for posttest counseling, and satisfaction of a technology platform designed for large-scale dissemination of NIPS results.

Methods: The technology platform provided general education videos to patients, results delivery through a secure portal, and access to telegenetic counseling through phone. Automatic results delivery to patients was sent only to patients with screen-negative results. For patients with screen-positive results, either the ordering provider or a board-certified genetic counselor contacted the patient directly through phone to communicate the test results and provide counseling.

Results: Over a 39-month period, 67,122 NIPS results were issued through the platform, and 4,673 patients elected genetic counseling consultations; 95.2% (n = 4,450) of consultations were for patients receiving negative results. More than 70% (n = 3,370) of consultations were on-demand rather than scheduled. A positive screen, advanced maternal age, family history, previous history of a pregnancy with a chromosomal abnormality, and other high-risk pregnancy were associated with the greatest odds of electing genetic counseling. By combining web education, automated notifications, and telegenetic counseling, we implemented a service that facilitates results disclosure for ordering providers.

Discussion: This automated results delivery platform illustrates the use of technology in managing large-scale disclosure of NIPS results. Further studies should address effectiveness and satisfaction among patients and providers in greater detail.

Conclusions: These data demonstrate the capability to deliver NIPS results, education, and counseling—congruent with professional society management guidelines—to a large population.

Keywords: cell-free DNA analysis, genetic counseling, noninvasive prenatal screening, prenatal screening, results delivery, telehealth

Introduction

Noninvasive prenatal screening (NIPS) through cell-free DNA analysis represents a recent development in fetal aneuploidy risk assessment. The utilization landscape has shifted from solely the high-risk population to include the general prenatal population.1,2 As NIPS usage grows, there is a need for a scalable and robust protocol for education regarding benefits and limitations of test results. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) underscores the importance of communicating results to patients in a timely manner and in the context of genetic counseling, adding that a policy of “no news is good news” does not represent high-quality care.3

Nongenetics providers play a critical role in educating patients about genetic testing, but they often lack confidence in their genetics knowledge, impacting their ability to have comprehensive discussions with patients.4–6 Although obstetricians are often involved in counseling patients about genetic testing, a gap in genetics knowledge still remains for many providers.6,7 Therefore, additional mechanisms of providing genetic screening information and results are essential.

The integration of genomics and technology enables efficient results delivery and genetic counseling. Patients are comfortable receiving health information online through patient portals rather than waiting for a provider to communicate test results.8 The noninferiority of web-based return of results and education compared with traditional genetic counseling has been demonstrated for carrier testing.9 Patient outcomes assessed at 1 and 6 months posttesting showed no difference in knowledge, test-specific distress, and decisional conflict about choosing to learn results between the two groups.9 Other studies have shown that web-based education tools and telegenetic services are viewed as valuable by patients and providers, effective in disseminating information to patients, and increase access to genetic clinicians while reducing patient costs.10,11 Previous studies have demonstrated the value and efficacy of alternative models of service delivery and education, but do not consider automatic results delivery to patients and providers or track patient interaction and usage with the results portal. Furthermore, these studies have been completed in the hereditary cancer screening population that may have different needs compared to the prenatal pregnant population with patients undergoing other testing such as carrier or non-invasive prenatal screening.

This study is the first to describe patient utilization and satisfaction of an automated results delivery system in conjunction with telegenetic counseling for NIPS. We describe the implementation of a service combining web-based education, automated results notifications, and telegenetic counseling that addresses two challenges: adequate education and results disclosure and tracking of large-scale genetic testing in a methodical, robust, and timely fashion. We sought to explore patient motivation for posttest genetic counseling and whether this technology platform of results delivery and genetic counseling achieves both high patient utilization and high patient satisfaction regardless of result type. This information would provide motivation for focused future studies on the satisfaction and effectiveness of patients and providers using the platform.

Methods

Institutional Review Board Review

This study was reviewed and designated as exempt by Western Institutional Review Board.

Platform

The technology platform (Counsyl Complete™), developed by Counsyl (South San Francisco), a molecular genetic testing laboratory, was developed to deliver education and results, and facilitate genetic counseling scheduling. The platform comprised two components: (1) a provider-facing Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA)-compliant online portal that logged key events (e.g., test ordering, completion of laboratory testing) and interactions between the patient and laboratory-employed genetic counselors, and (2) a patient-facing HIPAA-compliant portal that displayed test- and results-specific educational information and facilitated genetic counseling. Physician agreement was required to use the software platform. Providers had the option of ordering testing through the platform; however, this was not required. Results of all tests ordered were delivered through the platform, with exceptions described in the Inconclusive Results section hereunder.

Automated Results Delivery System

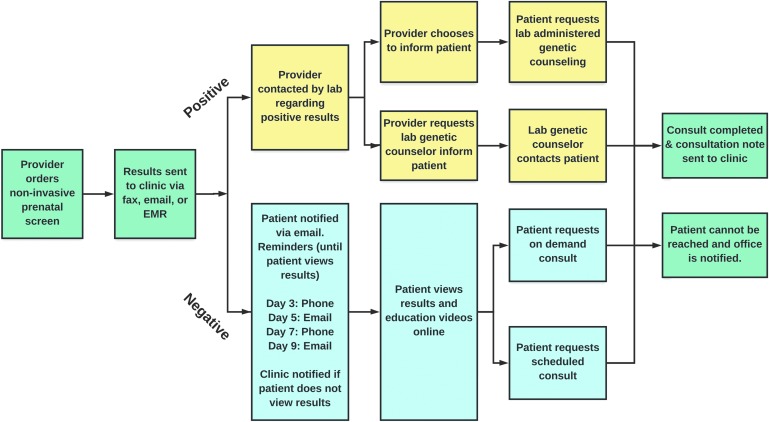

Genetic counselors employed by Counsyl utilized guidelines from ACOG, clinical expertise, and provider feedback to develop results notification, reminder, and tracking protocols.12,13 American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACMG) and ACOG guidelines were utilized for the creation of posttest education and counseling elements to develop a protocol for the delivery of NIPS results.14 Figure 1 illustrates the automated results delivery system workflow.

Fig. 1.

Automated results delivery workflow: Providers are notified upon results availability. If results are screen negative, patients are contacted and reminded to access results and educational resources, as well as request genetic counseling, through the portal. If results are screen positive, providers are contacted by the laboratory about preferred method of results delivery: (1) the provider may request that the laboratory inform the patient and provide counseling, or (2) the provider may inform the patient directly and release results to the patient through the portal, and advise the patient to schedule a genetic consultation with the laboratory. Regardless of result type, if genetic counseling is elected, a consultation report is sent to the ordering provider through fax, e-mail, or EMR. EMR, electronic medical record.

Provider-Facing Portal

Ordering providers were notified through fax, e-mail, or electronic medical record upon results availability. The online portal contained an activity log of patient interactions, including scheduling of genetic consultations and all reminders sent throughout the results delivery process. Regardless of result type, if a patient elected a genetic consultation, a report was sent to the ordering provider and patient.

Patient-Facing Portal

Upon laboratory receipt of a test requisition, patients received an e-mailed link to a 6-min NIPS general education video (Supplementary Video S1) created by genetic counselors at Counsyl in accordance with previously published recommendations.15,16 Patients had the option of canceling the test at any point before release of results with no financial penalty.

Negative results

Figure 1 describes the return of negative results to patients through the portal. Posttest education—presented in video and text format and accompanied by a downloadable clinical report—for screen-negative results summarized that no chromosomal abnormalities were detected, indicating a low residual risk for the tested conditions. All communication formats stated the possibility of false-positive and false-negative results. The clinical report included patient-specific residual risks for trisomies 13, 18, and 21, and also stated the necessity of chorionic villus sampling (CVS) or amniocentesis if definitive diagnosis was desired.

Positive results

Screen-positive results were not automatically released to the patient (Fig. 1). Rather, the ordering provider's office was contacted by a genetic counselor and informed of the screen-positive result. The provider could opt to disclose the result to the patient directly through phone call or in-person appointment, through the portal, or by requesting that a genetic counselor contact the patient by phone. All communication formats stated the possibility of false-positive and false-negative results and discussed individualized positive predictive value, when available. Similar to the reporting of screen-negative results, screen-positive results also stated the necessity of CVS or amniocentesis if definitive diagnosis was desired.

Inconclusive results

A minority of results (n = 61) were of high complexity, such as test failures because of sequencing error or suspected maternal aneuploidy. These were routed outside of the platform and were individually managed with the ordering provider. These results were not included in this study.

Telegenetic counseling

The patient portal enabled patients to elect a posttest consultation by phone with a genetic counselor regardless of result type and at no additional cost. All genetic counselors were laboratory-employed, board-certified, and licensed in the state of California, as well as licensed in the state in which they provided counseling, if required. Herein, when describing election of genetic counseling, we are referring specifically to the election of laboratory-delivered genetic counseling.

For screen-positive results, patients could request a consultation even if the provider disclosed the results directly to the patient. Patients requesting on-demand counseling were entered into a virtual queue and were contacted by telephone by a genetic counselor in the order the requests were received. Those requesting scheduled counseling could make an appointment for a future telephone consultation. The results delivery platform and education videos were in English, but certified medical interpreters for >200 languages were available if needed.

Following standard practice protocol and ACOG recommendations, genetic consultations included an overview of NIPS, a discussion of patient's results, and appropriateness of future diagnostic procedures.12,15 For patients who wished to pursue or further consider diagnostic testing, consultation with the ordering or other local provider was recommended. Consultation reports were made available to both the patient and provider upon completion. Patients were permitted to have unlimited sessions with no time limit, and counseling sessions were included in the cost of testing.

Patient feedback

A feedback survey was sent through e-mail to every patient who completed a genetic consultation. The survey included a five-point star scale and open-ended comments section. An average of the five-point scale responses was calculated to determine patient satisfaction with the genetic counseling service.

Data Analysis

Eligible patients' data were extracted from internal databases. Ethnicity was self-reported. Because of state regulations, samples from New York State were not included in data analyses. All statistical analyses were completed using Python version 2.7.13. Jeffrey's Bayesian interval and Goodman's method were used to compute binomial and multinomial proportion confidence intervals, respectively. The multivariate logistic regression was used to analyze which factors affected likelihood of electing genetic counseling. For this analysis, we excluded screen-positive patients that required a laboratory-administered genetic consultation (n = 32); a chi-squared test was used to calculate statistical significance. A one-tailed proportion z-test was used to calculate whether the proportion of patients with positive test results that elected on-demand genetic counseling was significantly higher than that of patients with negative test results. A nonparametric Mann–Whitney test was used to determine statistical significance of differences in durations for genetic consultations for patients with negative versus positive test results.

Noninvasive Prenatal Screen

NIPS analyses were conducted at Counsyl (Prelude™ Prenatal Screen) or Illumina (Verifi, Illumina, San Diego, CA) using the whole-genome sequencing method described by Fan et al.17 Patients from both high risk (e.g., advanced maternal age, other abnormal aneuploidy screen) and general prenatal populations were included. Chromosome analysis results could be reported as no aneuploidy detected (“screen negative”), aneuploidy detected (“screen positive”), or aneuploidy suspected (also “screen positive”).

Results

Cohort

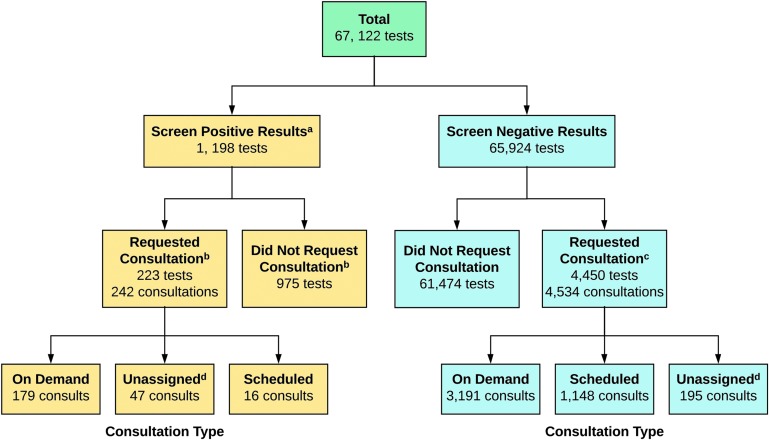

Over a 39-month period, 67,122 NIPS results were issued through the platform to 66,475 unique and eligible patients (Fig. 2). These results included 1,198 screen-positive tests and 65,924 screen-negative tests. Of the 1,198 screen-positive results, 18.6% (n = 223) of patients requested a genetic consultation. Median patient age was 34 years (interquartile range [IQR]: 30–37 years). Ethnicity was reported for 50,127 patients (75.4%), and represented 14 different ethnicities (Table 1).

Fig. 2.

Results delivered and consultation types scheduled through the automated delivery platform. aScreen-positive results include both aneuploidy suspected and aneuploidy detected. bFor screen-positive results, 204 patients had one consultation and 19 had two consultations. cFor screen-negative results, 4,373 patients had one consultation, 70 had two consultations, and seven had three consultations. dOn-demand versus scheduled consultation status was unassigned for 47 screen-positive and 195 screen-negative consultations as they occurred when a patient requested a genetic counseling appointment to discuss the results of different test offered by Counsyl (e.g., carrier screening) and also wished to discuss their NIPS result. NIPS, noninvasive prenatal screening.

Table 1.

Patient Ethnicities of Diverse Patient Cohort

| ETHNICITY | TESTED | % (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|

| African/African American | 4,461 | 6.7 (6.4–7.0) |

| Ashkenazi Jewish | 852 | 1.3 (1.1–1.4) |

| East Asian | 2,290 | 3.4 (3.2–3.7) |

| French Canadian/Cajun | 118 | 0.18 (0.1–0.2) |

| Finnish | 11 | 0.02 (.007–0.04) |

| Hispanic | 6,606 | 10.0 (9.6–10.3) |

| Middle Eastern | 803 | 1.2 (1.1–1.3) |

| Mixed/other Caucasian | 23,046 | 34.7 (34.7–35.2) |

| Native American | 225 | 0.3 (0.3–0.4) |

| Northern European | 7,213 | 10.9 (10.5–11.2) |

| Pacific Islander | 166 | 0.2 (0.2–0.3) |

| South Asian | 1,986 | 3.0 (2.8–3.2) |

| Southeast Asian | 1,412 | 2.1 (2.0–2.2) |

| Southern European | 938 | 1.4 (1.3–1.6) |

| Unknown/not reported | 16,348 | 24.6 (24.1–25.1) |

CI, confidence interval.

The basic panel assessed aneuploidy risk for chromosomes 13, 18, and 21 only (n = 2,946). In addition to screening for the basic panel, 57,654 screens assessed sex chromosome aneuploidy (SCA) risk (no microdeletions), 345 screens assessed microdeletions risk (no SCA), and 6,167 assessed both SCA and microdeletions risk. Median turnaround time for test results was 4 days (IQR: 3–5 days). Screen-positive result types are listed in Table 2.

Table 2.

Screen-Positive Results

| CONDITION SCREENED | SCREEN-POSITIVE RESULTS |

|---|---|

| Trisomy 13a | 110 |

| Trisomy 18a | 176 |

| Trisomy 21a | 458 |

| Monosomy 13 | 22 |

| Monosomy 18a | 12 |

| Monosomy 21 | 9 |

| Monosomy X | 253 |

| XXX | 56 |

| XXY | 53 |

| XYY | 28 |

| del1p36 | 7 |

| del5p | 8 |

| del4p | 6 |

| del15q11.2 | 12 |

| del22q | 8 |

| Total | 1,218b |

Includes both aneuploidy-suspected and aneuploidy-detected results.

Some tests were positive for multiple conditions: 1,180 tests were positive for one condition, 16 tests were positive for two conditions and 2 tests were positive for three conditions.

Portal Use

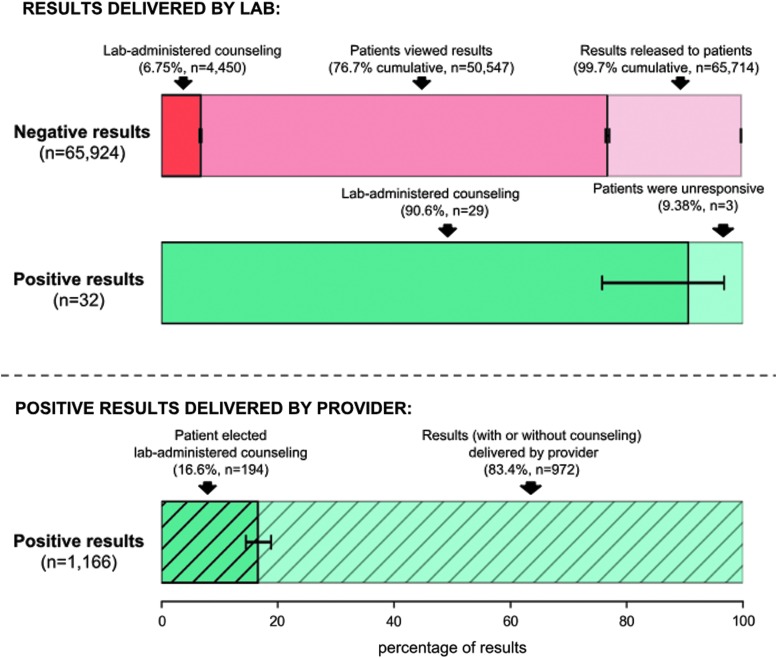

Results were successfully delivered to 99.7% (n = 65,714) of patients who screened negative; remaining results were undeliverable because of incomplete or incorrect e-mail addresses (Fig. 3). Of those receiving screen-negative results, 76.7% (n = 50,547) viewed their test results in the portal and 6.75% (n = 4,450) completed a genetic consultation (Fig. 3). More than 97% (n = 1,166) of screen-positive results were delivered by the patient's provider. Providers requested that the laboratory deliver screen-positive results for 32 patients (2.67%). More than 90% (n = 29) of these individuals completed a genetic consultation; the remaining three (9.38%) were unresponsive to requests for counseling. Of screen-positive patients whose provider delivered their results, 16.6% (n = 194) requested genetic counseling (Fig. 3). Eighty-seven percent of all screen-positive genetic consultations were for patients whose results were delivered by the provider.

Fig. 3.

Patient utilization of automated results workflow. Results delivery for screen-negative and screen-positive results, with positive screens stratified by provider and laboratory delivery. In each horizontal bar, shading denotes the percentage of patients with the specified result type that completed the action denoted in the automated results workflow described in Figure 1. The pink bar denotes screen-negative results, stratified by results released (light pink), patient viewing of results (medium pink), and laboratory-delivered genetic counseling (dark pink). The solid green bar denotes screen-positive results delivered by the laboratory, stratified by the percentage of patients that did (dark green) and did not (light green) elect genetic counseling. The hatched green bar denotes screen-positive results delivered by the provider, stratified by the percentage of patients that did (dark green) and did not (light green) elect genetic counseling; 95% confidence intervals are given.

Factors Affecting Likelihood Of Laboratory-Delivered Genetic Counseling

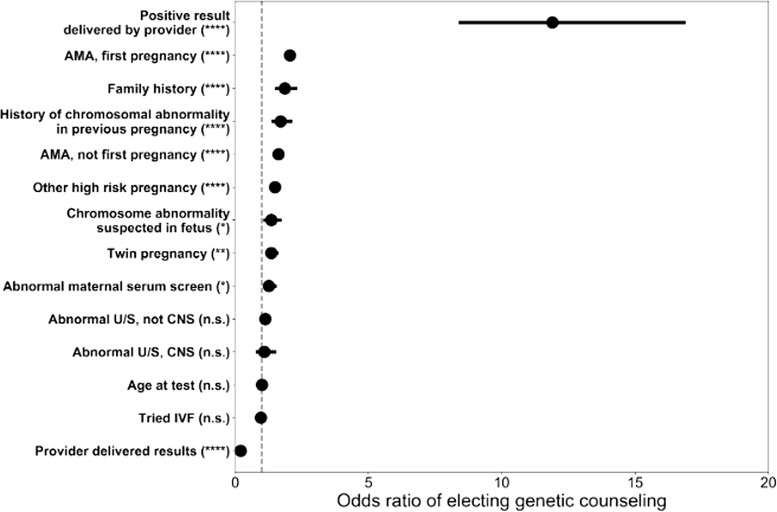

Odds of choosing a genetic consultation were 11.9 times greater among those with screen-positive test results compared with those without a screen-positive test result (p < 0.0001) (Fig. 4). Other significant factors associated with increased odds of electing genetic counseling included advanced maternal age (age at test of 35 years or older, both first and subsequent pregnancy), family history, history of a chromosomal abnormality in a previous pregnancy, and other high-risk pregnancy (p < 0.0001) (Fig. 4). Specific year of birth, whether a patient used in vitro fertilization, and abnormal ultrasound were not significantly associated with increased odds of electing genetic counseling (Fig. 4). An ordering provider delivering test results was significantly associated with decreased odds of electing genetic counseling (p < 0.0001). The number of patients electing genetic counseling by testing indication are provided in Table 3.

Fig. 4.

Factors most associated with electing laboratory-delivered genetic counseling. Odds ratios of factors associated with higher propensity of seeking laboratory-delivered genetic counseling. An odds ratio >1 indicates that a patient with the factor of interest is at increased odds to elect genetic counseling. An odds ratio <1 indicates that a patient with the factor of interest is at decreased odds to elect genetic counseling. Circles show point estimates of odds ratios; 95% confidence intervals are given with horizontal lines. Statistical significance is given with asterisks. ****p < 0.0001; ***p < 0.001; **p < 0.01; *p < 0.05; n.s.: not significant at the p = 0.05 significance level. AMA, advanced maternal age; CNS, central nervous system; IVF, in vitro fertilization; U/S, ultrasound.

Table 3.

Factors Affecting Genetic Counseling Election

| POSITIVE TEST RESULTS DELIVERED BY PROVIDER | POSITIVE TEST RESULT DELIVERED BY PROVIDER AND ELECTED GENETIC COUNSELING | NEGATIVE TEST RESULTS | NEGATIVE TEST RESULT AND ELECTED GENETIC COUNSELING | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AMA, first pregnancy | 137 | 19 (13.8%) | 7,427 | 746 (10.0%) |

| AMA, not first pregnancy | 517 | 75 (14.5%) | 21,562 | 1,765 (8.2%) |

| Abnormal U/S, central nervous system | 33 | 3 (9.1%) | 504 | 36 (7.1%) |

| Abnormal U/S, other | 113 | 14 (12.4%) | 2,180 | 144 (6.6%) |

| Chromosome abnormality suspected in fetus | 57 | 8 (14.0%) | 785 | 68 (8.6%) |

| Other high-risk pregnancy | 55 | 11 (22.0%) | 3,027 | 262 (8.7%) |

| Family history | 10 | 1 (10.0%) | 860 | 89 (10.3%) |

| History of chromosomal abnormality in previous pregnancy | 11 | 3 (27.3%) | 831 | 86 (10.3%) |

| Abnormal maternal serum screen | 48 | 8 (16.7%) | 1,413 | 100 (7.1%) |

| Twin pregnancy | 15 | 1 (6.7%) | 1,388 | 134 (9.7%) |

| Tried IVF | 58 | 11 (19.0%) | 3,240 | 243 (7.5%) |

| Provider delivered results | 1,166 | 194 (16.6%) | 2,172 | 40 (1.8%) |

| Positive test results | 1,166 | 194 (16.6%) | 0 | 0 (0%) |

AMA, advanced maternal age; IVF, in vitro fertilization; U/S, ultrasound.

Consultations

Of the total study population of 66,475 unique patients, 4,655 (7.0% overall; range of 4.2–11.3% by ethnicity) elected genetic counseling. These 4,655 unique patients accounted for 4,673 total tests and 4,776 genetic consultations (Fig. 2), and had a median age of 35 years (IQR: 31–38 years). Median age among those who did not speak with a genetic counselor was 34 years (IQR: 30–37 years, n = 61,820). Individuals of 14 ethnicities completed consultations (not given). For 96 tests, multiple consultations were completed (Fig. 2). The average wait time for patients seeking an on-demand genetic consultation was 11 min (IQR: 3–24 min).

An additional unassigned 242 genetic consultations were completed for 47 screen-positive results and 195 screen-negative results (Fig. 2). On-demand versus scheduled consultation status was not available for these 242 consultations as they occurred when a patient requested a genetic counseling appointment to discuss the results of a different test offered by the laboratory (e.g., carrier screening) and wished to discuss their NIPS result concurrently.

Negative results

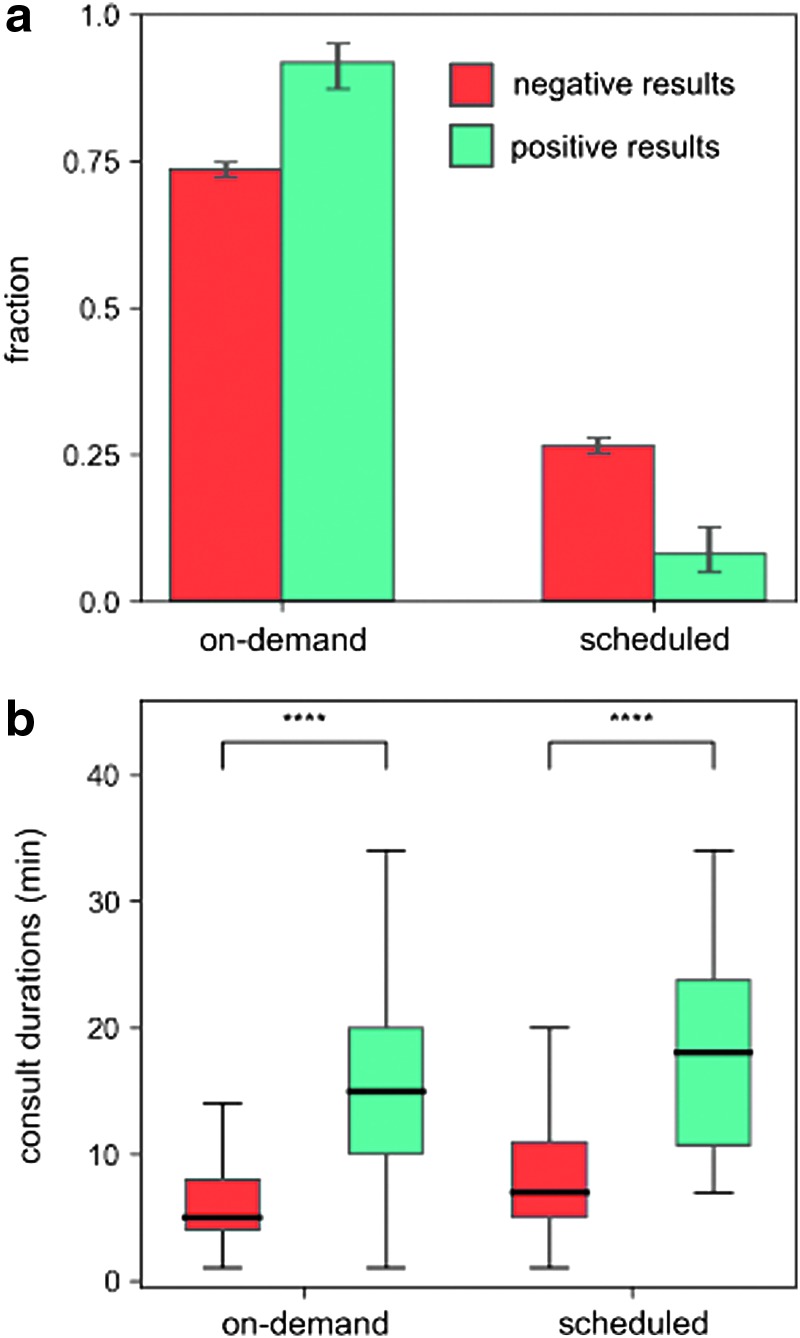

Of the 65,924 individuals with screen-negative test results, 6.75% (n = 4,450) elected a genetic consultation. Consultations with individuals with negative screens accounted for 94.9% (n = 4,534) of all consultations; 70.4% (n = 3,191) of these consultations were on-demand and 25.3% (n = 1,148) were scheduled (Fig. 5a).

Fig. 5.

Utilization of genetic counseling. (a) Fraction of on-demand and scheduled genetic counseling sessions, stratified by result type (screen negative or screen positive), with 95% confidence intervals. Unassigned consultations are not reflected. (b) Consultation durations stratified by reservation type and result type. Consultation duration times are significantly lower for screen-negative results compared with screen-positive results at the p < 0.001 significance level (indicated by “****”) for both on-demand and scheduled consults. Bolded lines show median values and the boxes show IQR. Vertical lines show 1.5 times the IQR. For (a) and (b), 242 unassigned consultations (n = 47 screen-positive results and n = 195 screen-negative results) are not included. IQR, interquartile range.

Positive results

Genetic counseling was elected by 18.6% (n = 223) of individuals with screen-positive results. Of the consultations for screen-positive results, 74.0% (n = 179) were for on-demand genetic counseling and 6.6% (n = 16) were scheduled (Fig. 5a). A significantly higher proportion of patients with screen-positive test results sought on-demand counseling over scheduled counseling compared with patients with screen-negative test results (p < 0.001). There were no statistical differences in factors associated with increased odds of electing genetic counseling for screen-positive results.

Consultation durations

Regardless of the type of consultation (scheduled vs. on-demand), consultations for screen-positive test results had significantly longer durations than those for screen-negative test results (p < 0.001) (Fig. 5b). The median consultation time for an individual with a positive screen was 14 min (IQR: 10–20 min), whereas the median time for an individual with a negative screen was 6 min (IQR: 4–9 min) (Fig. 5b).

Patient satisfaction rating

Patients rated their satisfaction for 21.9% (n = 1,048) of genetic consultations. This included 42 patients with screen-positive test results and 1,006 patients with screen-negative test results. The mean satisfaction rating was 4.9/5.0 (range: 1–5). Among individuals with negative screens that provided a satisfaction rating, 93.7% (n = 943) rated their satisfaction as 5/5. Of 42 patients with positive screens, 1 rated satisfaction as 2/5, 1 rated satisfaction as 4/5, and 40 rated satisfaction as 5/5.

Discussion

This study demonstrates high patient utilization of a results delivery platform that distributed 67,122 NIPS results and provided 4,776 genetic consultations. The platform is unique in several respects: it has served a large and diverse population of 66,475 patients, has been in sustained clinical usage for 3 years, and delivers automated and technology-driven results, counseling, and patient education.

Patients reported a high rate of satisfaction and comfort with telegenetic counseling,18,19 and online education systems have been shown to have a positive impact on patient understanding and clinical outcomes.10,11,20 Web-based delivery platforms have been found to be noninferior to in-person counseling, suggesting that alternative delivery models should be considered in the face of limited resources, the need to reduce health care spending, and potentially help facilitate the interpretation of genetic testing by nongenetic professionals.9

Our platform allowed for both screen-negative and screen-positive patients to request telegenetic counseling. In this cohort, 18.6% of patients with screen-positive results elected to speak with a genetic counselor through the automated results delivery platform. This number may be lower than expected because 97% of screen-positive results were delivered by the ordering provider and many of these patients may have been automatically referred for follow-up counseling and education with a local high-risk specialist or genetic counselor.

Although patients with positive results were most likely to elect genetic consultations, the vast majority of consultations were for screen-negative patients. Interestingly, patients with preexisting risk factors, such as advanced maternal age and family history, even among patients with negative results, were more likely to elect laboratory-provided genetic counseling than patients without these risk factors. As the majority of NIPS results are screen negative, these data demonstrate that screen-negative patients desire education and genetic counseling.

This study demonstrated that patients were significantly more likely to opt for on-demand genetic counseling compared with a scheduled appointment regardless of result type, suggesting that patients desire to receive education concurrent with results. Unsurprisingly, median consultation duration was more than twice as long for patients with positive results than those with negative results, likely because of the need to discuss diagnostic testing and other options in greater detail after a positive result.

The study cohort included only patients whose providers chose to use the automated platform for NIPS results delivery and laboratory-based genetic counseling services. Therefore, we cannot definitively conclude that our results would be applicable to all prenatal patient populations. However, the cohort was large and diverse in terms of ethnicity and age, and was representative of our total tested population. This study did not include data on patient motivators for using the platform, nor did it assess anxiety or knowledge gain and retention among patients interacting with the portal. Pretest counseling (not addressed in this study) may have impacted patient use of the portal or election of posttest counseling. In addition, potential effects of the service on the ordering providers' patient-management practices, such as reductions in time spent delivering results and additional posttest counseling, were not addressed in this study. These limitations lend themselves to important directions for future research such as patients' and professionals' satisfaction, effectiveness, preferences, knowledge, and experiences with the service.

Conclusion

The desire for on-demand genetic counseling, regardless of result type, demonstrated in this study suggests that alternative counseling and education platforms will be necessary as genetic testing becomes more widespread in the clinical setting, and as practices attempt to follow guidelines recommending timely results delivery and counseling. Critically, clinicians have a responsibility to provide support, education, and counseling to patients when ordering testing.3 Laboratories offering testing have an opportunity to support this need by working with ordering providers to improve patient access to accurate, personalized, and timely information and counseling.

By combining web-based education, automated notification protocols, and telegenetic counseling, we demonstrated high patient utilization of a service that efficiently manages NIPS results disclosure. Providing large-scale results delivery, education, and counseling—congruent with clinical guidelines—is imperative to quality clinical care as genetic testing uptake grows among the general obstetric population.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Jaclyn Eng, and Harris Naemi, both employees of Counsyl, for editorial assistance. This study was funded by Counsyl.

Disclosure Statement

All authors are employees of Counsyl.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1. Palomaki GE, Kloza EM, Lambert-Messerlian GM, et al. DNA sequencing of maternal plasma to detect Down syndrome: An international clinical validation study. Genet Med 2011;13:913–920 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Gregg AR, Skotko BG, Benkendorf JL, et al. Noninvasive prenatal screening for fetal aneuploidy, 2016 update: A position statement of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics. Genet Med 2016;18:1056–1065 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Counseling about genetic testing and communication of genetic test results. ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 693. Obstet Gynecol 2017;129:e96–e101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Klitzman R, Chung W, Marder K, et al. Attitudes and practices among internists concerning genetic testing. J Genet Couns 2013;22:90–100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Houwink EJ, van Luijk SJ, Henneman L, et al. Genetic educational needs and the role of genetics in primary care: A focus group study with multiple perspectives. BMC Fam Pract 2011;12:5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Mikat-Stevens NA, Larson IA, Tarini BA. Primary-care providers' perceived barriers to integration of genetics services: A systematic review of the literature. Genet Med 2015;17:169–176 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Menzin AW, Anderson BL, Williams SB, Schulkin J. Education and experience with breast health maintenance and breast cancer care: A study of obstetricians and gynecologists. J Cancer Educ 2010;25:87–91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Johnson AJ, Easterling D, Nelson R, et al. Access to radiologic reports via a patient portal: Clinical simulations to investigate patient preferences. J Am Coll Radiol 2012;9:256–263 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Biesecker BB, Lewis KL, Umstead KL, et al. Web platform vs in-person genetic counselor for return of carrier results from exome sequencing: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med 2018;178:338–346 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Lewis D. Computer-based approaches to patient education: A review of the literature. J Am Med Inform Assoc 1999;6:272–282 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Otten E, Birnie E, Ranchor AV, van Langen IM. Online genetic counseling from the providers' perspective: Counselors' evaluations and a time and cost analysis. Eur J Hum Genet 2016;24:1255–1261 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Invasive prenatal testing for aneuploidy. ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 88. Obstet Gynecol 2007;110:e1459–e1467 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Tracking and reminder systems. ACOG Committee Opinion No. 461. Obstet Gynecol 2010;116:e464–e466 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Gregg AR, Gross SJ, Best RG, et al. ACMG statement on noninvasive prenatal screening for fetal aneuploidy. Genet Med 2013;15:395–398 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Sachs A, Blanchard L, Buchanan A, et al. Recommended pre-test counseling points for noninvasive prenatal testing using cell-free DNA: A 2015 perspective. Prenat Diagn 2015;35:968–971 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Prenatal diagnostic testing for genetic disorders. ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 162. Obstet Gynecol 2016;127:e108–e122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Fan HC, Blumenfeld YJ, Chitkara U, et al. Noninvasive diagnosis of fetal aneuploidy by shotgun sequencing DNA from maternal blood. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2008;105:16266–16271 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Schwartz MD, Valdimarsdottir HB, Peshkin BN, et al. Randomized noninferiority trial of telephone versus in-person genetic counseling for hereditary breast and ovarian cancer. J Clin Oncol 2014;32:618–626 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Sutphen R, Davila B, Shappell H, et al. Real world experience with cancer genetic counseling via telephone. Fam Cancer 2010;9:681–689 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kuppermann M, Pena S, Bishop JT, et al. Effect of enhanced information, values clarification, and removal of financial barriers on use of prenatal genetic testing. JAMA 2014;312:1210–1217 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.