Abstract

Cementoblastoma, a benign mesenchymal odontogenic neoplasm is derived from ectomesenchymal cells of the periodontium. Cementoblastomas associated with primary teeth are extremely rare as permanent mandibular first molars are mostly affected. Only 17 cases of those associated with deciduous dentition have been reported so far. The present case report describes a true cementoblastoma of an 8-year-old male child in relation to the left first primary mandibular molar along with emphasis on differential diagnosis.

Keywords: Cementoblastoma, deciduous dentition, differential diagnosis, odontogenic neoplasm

INTRODUCTION

Cementoblastoma is a slow-growing, benign odontogenic neoplasm of mesenchymal origin, with unlimited growth potential and is derived from ectomesenchymal cells of the periodontium including cementoblasts.[1] Cementoblastoma was first described by Dewey in 1927[2] and was recognized first by Noeberg[1] in 1930. They are commonly seen in children and young adults; males are more frequently affected than females, with more occurrences in mandible than maxilla. Radiographically, benign cementoblastoma appears as a well-defined radio-opacity with a radiolucent peripheral zone. The growth rate for cementoblastoma is estimated to be 0.5 cm/year.[3] The histological features of cementoblastoma include cementum-like tissue with numerous reversal lines, and between these mineralized and trabecular hard tissues, fibrovascular tissue with cementoblast-like cells is present along with multinucleated giant cells.[4] The treatment of choice is complete removal of the lesion with extraction of associated tooth, followed by thorough curettage and peripheral ostectomy. The recurrence rate is 21.7%–37.1%.[3] It is a rare tumor with <300 cases ever reported in literature.[5] Cementoblastoma is more commonly associated with permanent mandibular first molars with deciduous teeth being rarely involved.[6] So far, only 17 cases[6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22] involving deciduous dentition have been reported [Table 1]. The present case report describes a true cementoblastoma in relation to the left first primary mandibular molar in an 8-year-old child along with emphasis on differential diagnosis.

Table 1.

Demographic factors of cementoblastoma cases reported from 1965 to 2018

| Author and years | Age | Gender | Site | Teeth affected | Treatment | Recurrence | Follow-up |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chaput and Marc 1965[6] | 10 | Female | Lower posterior mandible | Right mandibular first premolar and second deciduous molar | ND | ND | ND |

| Vilasco et al., 1969[7] | 8 | Female | Lower posterior mandible | Right mandibular second deciduous molar | ND | ND | ND |

| Zachariades et al., 1985[8] | 7 | Female | Lower posterior mandible | Deciduous first and second molars and first permanent molar | Enucleation | Absent | LTF |

| Herzog 1987[9] | 7 | Female | Posterior mandible | Deciduous first and second molars | ND | ND | ND |

| Cannell 1991[10] | 8 | Female | Posterior mandible | Deciduous second molar | ND | ND | ND |

| Schafer et al., 2001[11] | 8 | Female | Posterior mandible | Deciduous second molar | Excision | ND | LTF |

| Ohki et al., 2004[12] | 12 | Male | Posterior mandible | Right maxillary second deciduous molar, first premolar and the first and second permanent molars Both the crown and the root of the un-erupted second premolar | Excision | Absent | FOD |

| Lemberg et al., 2007[13] | 10 | Female | Posterior mandible | Deciduous second molar | Excision | Absent | FOD |

| Vieira et al., 2007[14] | 7 | NM | Posterior mandible | Deciduous second molar | Excision | Absent | ND |

| de Noronha Santos Netto et al., 2012[15] | 4 | Female | Posterior mandible | Deciduous first molar | Excision | Absent | FOD |

| Solomon et al., 2012[16] | 7 | Female | Posterior maxilla | Deciduous second molar | Sub totalmaxillectomy | Present | FOD |

| Monti et al., 2013[17] | 11 | Female | Posterior mandible | Deciduous second molar | En bloc resection | ND | ND |

| Urs et al., 2016[18] | 10 | Male | Posterior maxilla | Deciduous first and second molar | Excision | Absent | FOD |

| Nuvvula et al., 2016[19] | 7 | Female | Posterior mandible | Deciduous second molar | Excision | Absent | FOD |

| Javed and Hussain Shah 2017[20] | 10 | Female | Anterior and posterior maxilla | Deciduous canine to second molar with permanent first molar | Ostectomy with chemical cauterization | Absent | FOD |

| Nagvekar et al., 2017[21] | 12 | Male | Posterior maxilla | Deciduous second molar | Excision | Absent | FOD |

| Mohammadi et al., 2018[22] | 4.5 | Male | Posterior mandible | Deciduous second molar and first permanent molar | Excision | Present | FOD |

| Present case | 8 | Male | Posterior mandible | Deciduous second molar | Excision | Absent | FOD |

ND: No data, LTF: Lost to follow up, FOD: Free of disease, NM: Not mentioned

CASE REPORT

An 8-year-old healthy male child reported to the Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Pathology of our institute with a chief complaint of pain and mild swelling in the left body of the mandible which had been increasing in size for the past 2 months. On clinical examination, no extraoral swelling was present in lower one-third of the face. Mild intraoral swelling with obliteration of the vestibular space was associated with deciduous mandibular left first molar. The swelling was diffuse and hard in consistency, with expansion of buccal cortex. Tenderness on palpation was noticed. Overlying mucosa was normal with no ulceration or purulent discharge. No carious teeth were seen in the region.

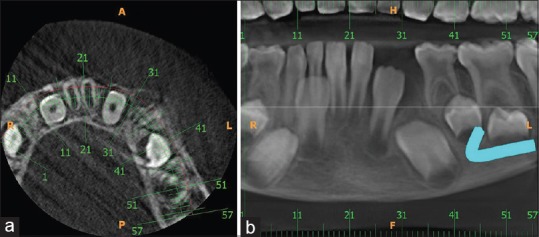

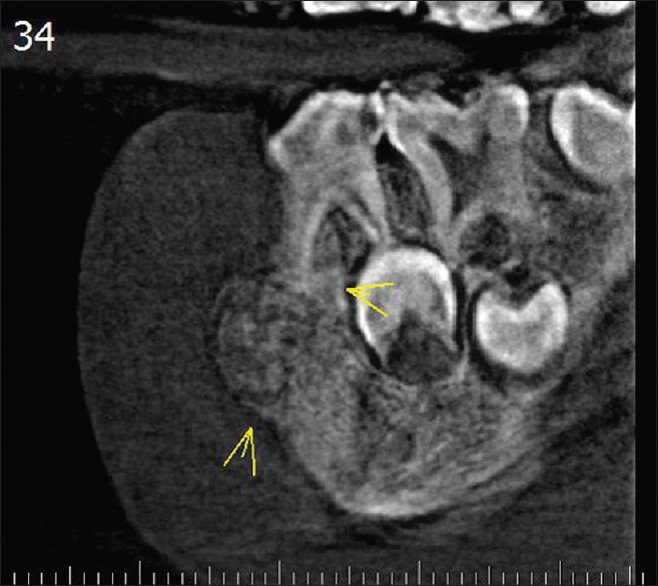

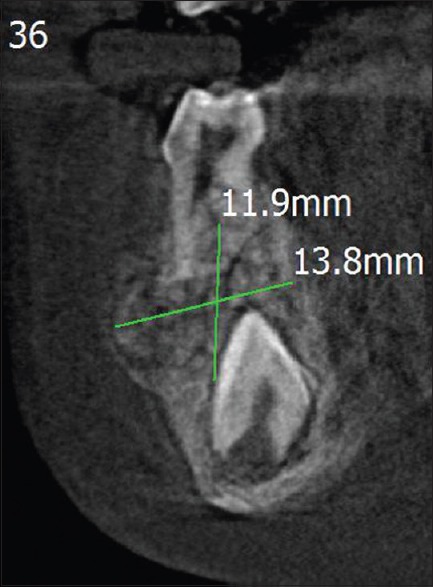

Radiological examination using cone beam computed tomography revealed a localized mixed radio-opaque–radiolucent lesion in the buccal aspect extending from the distal aspect of 32 to the mesial aspect of developing 34 [Figure 1a and 1b]. The lesion was surrounded by a thin, uniform radiolucent line [Figure 2]. It was involving the periapices of 74 and was in continuity with the roots of the same [Figure 3]. It extended inferiorly up to the middle third level of the coronal portion of the developing 33. The approximate maximum dimensions of the lesion were 11.9 mm × 13.8 mm × 16 mm [Figure 4]. Considering the clinical and radiographical findings, differential diagnosis of the lesion included odontogenic tumor, fibro-osseous lesion or hypercementosis. An excisional biopsy was performed for final diagnosis.

Figure 1.

Cone beam computed tomography showing localized mixed radio-opaque–radiolucent lesion in the buccal aspect extending from the distal aspect of 32 to the mesial aspect of developing 34. (a) Axial view (b) Panoramic view

Figure 2.

Cone beam computed tomography showing lesion surrounded by a peripheral radiolucency (yellow arrows)

Figure 3.

Cone beam computed tomography radio-opacity involving the periapices of 74 and is in continuity with the roots of the same (yellow arrows)

Figure 4.

Cone beam computed tomography approximate maximum dimensions of the lesion (11.9 mm × 13.8 mm)

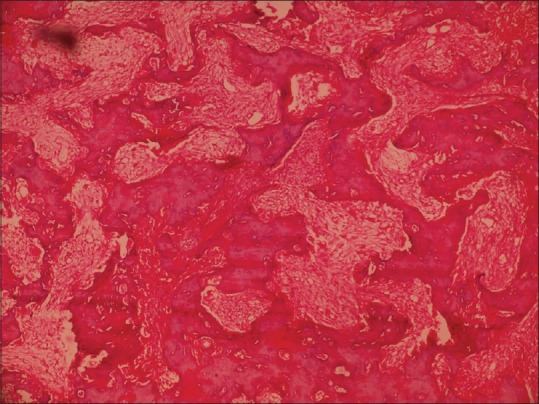

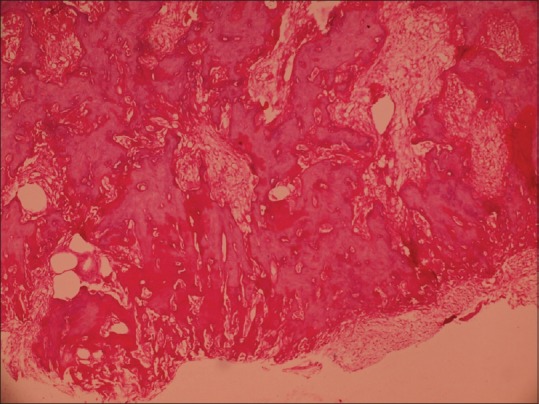

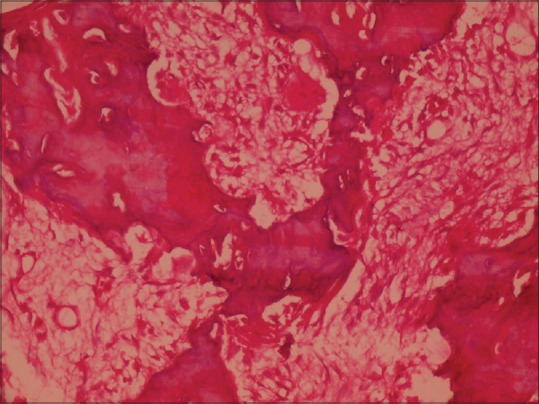

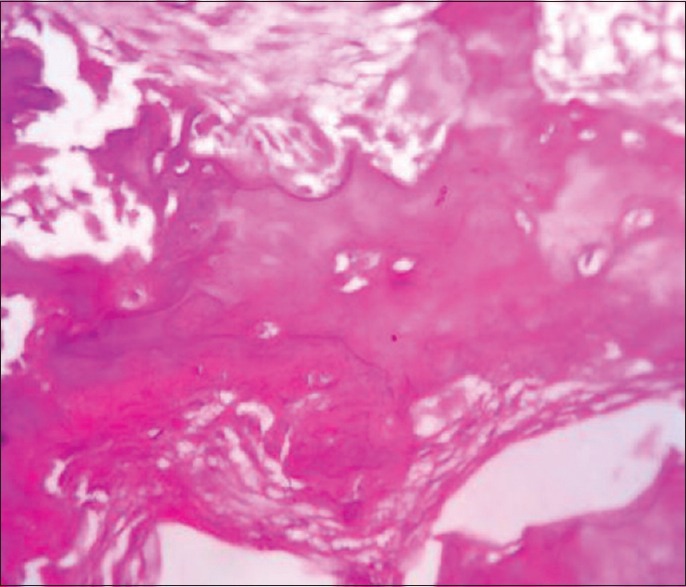

The gross specimen included multiple bits of hard tissues and deciduous mandibular first molar. Hematoxylin and eosin stained sections showed sheets of cementum-like tissue with prominent reversal lines [Figure 5]. Areas of fibrovascular connective tissue interspersed between cementum like masses [Figure 6]. At the periphery of the lesion, radiating columns of cellular unmineralized cementoid tissue was evident [Figure 7]. Multinucleated giant cells and plump cementoblasts were also seen [Figure 8]. Prominent and numerous basophilic reversal lines were appreciable [Figure 9]. On basis of clinical, radiological and histopathological correlation, a diagnosis of cementoblastoma was given. The patient is on follow up since last 6 months and is free of disease.

Figure 5.

Photomicrograph of hematoxylin and eosin stained decalcified sections show sheets of cementum like tissue with prominent reversal lines (H&E stain, ×4)

Figure 6.

Photomicrograph of hematoxylin and eosin stained decalcified sections show areas of fibrovascular connective tissue interspersed between cementum like masses (H&E stain, ×10)

Figure 7.

Photomicrograph of hematoxylin and eosin stained decalcified sections show radiating columns of cellular unmineralized cementoid tissue at the periphery of the lesion (H&E stain, ×10)

Figure 8.

Photomicrograph of hematoxylin and eosin stained decalcified sections show multinucleated giant cells and plump cementoblasts (H&E stain, ×40)

Figure 9.

Photomicrograph of hematoxylin and eosin stained decalcified sections show prominent and numerous basophilic reversal lines (H&E stain, ×40)

DISCUSSION

Cementoblastoma is a rare lesion that represents <1% of the odontogenic tumors.[6] Their prevalence among all odontogenic tumors has been reported to vary from 0.69% to 8%.[18,19,20,21,22,23] It is more common in young patients, with about 50% of them arising under the age of 20 years. Females (78.5%) are more commonly affected than males (21.5%). Most cementoblastomas are closely allied to and partly surround a root or roots of a single erupted permanent tooth.[24] It most commonly occurs in the mandibular molar–premolar region.[25] Primary teeth are very rarely affected. Mandibular arch (93%) is more commonly involved than the maxillary arch (7%). Cementoblastoma was commonly seen on the right side (71.5%) of mandibular arch, followed by the left side of the mandibular arch (21.5%) and the right side of the maxillary molar region (7%), the most common tooth affected being right mandibular second molar (71%).[19] The present case is in accordance with the literature and is only the 18th case report so far, associated with the primary molar.

Painful swelling at the buccal and lingual/palatal aspect of the alveolar ridges is the most common symptom associated with cementoblastoma. Occasionally, it may be asymptomatic. The involved tooth remains vital. Cortical expansion and facial asymmetry are also common findings. Lower lip paresthesia or a pathologic fracture of the mandible is rarely reported.[26] In the present case, the patient complained of pain and mild swelling in the lower left posterior region.

Cementoblastoma is derived from the functional cementoblasts of odontogenic ectomesenchyme that lay down cementum on the tooth root. Cementoblastoma is continuous with the cemental layer of the apical third of the tooth root and remains separated from bone by a continuation of the periodontal ligament (PDL), all of which supports an odontogenic origin.[27] Pathogenesis of cementoblastoma progresses in three stages with first stage being periapical osteolysis followed by cementoblastic stage and finally with calcification and maturation.[28] Radiographically, it appears as a well-defined radio-opacity surrounded by a radiolucent periphery and is continuous with the apical one-third of the root and PDL. The histopathological features of cementoblastoma include sheets of cementum-like material continuous with the tooth root. The proliferating cementum is lined by numerous plump cementoblasts. Cementoblasts are also present along with prominent reversal lines. Some of the cemental material maybe noncalcified, particularly at the periphery of the mass the tumor and often arranged in struts perpendicular to the capsule. The fibrous stroma is highly vascular.[29] The present case meets the radiological and histopathological criteria of a benign cementoblastoma.

Osteoblastoma, odontoma, focal cement osseous dysplasia (FCOD), condensing osteitis and hypercementosis could be considered in differential diagnosis of benign cementoblastoma.[30,31,32] An attempt has been made to compare and contrast aforementioned lesions with benign cementoblastoma on clinical, radiological and histopathological features [Table 2].

Table 2.

Compare and contrast benign cementoblastoma with other lesions

| Common features | Osteoblastoma | Cementoblastoma |

|---|---|---|

| Clinical features | Clinical features | Clinical features |

| Arises in young adults | Not associated with tooth roots | Intimately associated with the tooth roots |

| Slowly progressive | Arises in the medullary cavity | Arises from the cementoblasts in the PDL |

| Shows bony expansion | ||

| Radiographic features | Radiographic features | |

| Absence of peripheral radiolucent rim | Radiopaque masses attached to teeth and surrounded by a radiolucent periphery | |

| Histopathological features | Histopathological features | Histopathological features |

| Cellular and vascular stroma with sheets of bone/cemental tissue and multinucleated giant cells | Reversal lines absent | Reversal lines present |

| Common features | Odontomes | Cementoblastoma |

| Radiographic features | Radiographic features | Radiographic features |

| Both are usually sharply marginated, and sclerotic, with a low-attenuation halo | They are usually pericoronal | Appear periapically directly fusing to the root of the tooth |

| Histopathological features | Histopathological features | Histopathological features |

| Cemental tissue with reversal lines | Presence of dentin and pulp also | Presence of only cemental tissue |

| Common features | FCOD | Cementoblastoma |

| Clinical features | Clinical features | Clinical features |

| Both cementoblastoma and FCOD are periapical, sclerotic, sharply marginated lesions with a low-attenuation halo | Reactive lesion usually asymptomatic More common in the 4th or 5th decade of life Does not fuse to tooth roots | Neoplastic lesion that maybe associated with pain and bony expansion More common in children and young adults Fuses with the tooth roots |

| Radiographic features | Radiographic features | |

| Mature stage is radio-opaque with poorly defined margins | Lesion is radio-opaque with well-defined radiolucent margins | |

| Histopathological features Bone and cementum like tissue |

Histopathological features Only cemental tissue |

|

| Common features | Condensing Osteitis | Cementoblastoma |

| Clinical features | Radiographic features | Radiographic features |

| Both occur in younger age group Both are usually seen in premolar molar region Both are sclerotic lesions |

Periapical, poorly marginated, nonexpansile, sclerotic lesion associated with a carious nonvital tooth, and it may be unifocal or multifocal It does not show a peripheral radiolucent rim |

Periapical, sharply marginated, expansile and sclerotic lesion Shows a peripheral radiolucent rim No thickening of the PDL space Tooth is vital |

| The adjacent tooth usually has a thickened PDL space or periapical inflammatory lesion (e.g., granuloma, cyst or abscess) | ||

| Common features | Hypercementosis | Cementoblastoma |

| Clinical features | Clinical features | Clinical features |

| Both appear as periapical radiopacities | No clinical signs or symptoms | Painful swelling at the buccal and lingual/palatal aspect of the alveolar ridges; occasionally, it may be asymptomatic |

| Radiographic features | Radiographic features | |

| The radiolucent shadow of the periodontal membrane and the radiopaque lamina dura are always seen on the outer border of hypercementosis, enveloping it as seen in normal cementum | The calcified mass is attached to the tooth root, with loss of root contour due to root resorption and fusion with the tumor | |

| Histopathological features | Histopathological features | Histopathological features |

| Disproportional acellular cementum deposit attached to the root of the tooth, associated with a thin connective tissue | Absence of active cementoblasts | Presence of active cementoblasts |

FCOD: Focal cemento-osseous dysplasia, PDL: Periodontal ligament

The treatment includes removal of the tumor en masse with the affected tooth. If the tumor is incompletely removed, the recurrence rate is as high as 37.1%.[4] The prognosis of the tumor is excellent if it is removed in toto as then there are very minimal chances of recurrence.[33] In the present case also, the lesion was excised along with the extraction of primary first molar and a 6-month follow-up showed no recurrence. There are no reported cases of malignant transformation in benign cementoblastoma till date.

CONCLUSION

The occurrence of cementoblastoma in association with primary teeth is extremely rare (seriously rare). However, it is important to include these lesions in the differential diagnosis of bony lesions in association with tooth roots. Although there are no reported cases of malignant transformation of benign cementoblastoma (rarely serious), there are reported cases in literature exhibiting signs of local aggressiveness and destruction.[34] Also, there seems to be difficulty many a times in differentiating bone from cementum and hence distinguishing cementum-related lesions (benign cementoblastoma, hypercementosis and cement ossifying fibroma) from those related to bone (FCOD, condensing osteitis, cement ossifying fibroma and osteoblastoma). Thus, previous study showing modified Gallego Stain in distinguishing cementum (brilliant red) from bone (green) maybe valuable in concluding the diagnosis where dilemma exists so as to render appropriate treatment and have better patient compliance.[35]

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent forms. In the form the patient(s) has/have given his/her/their consent for his/her/their images and other clinical information to be reported in the journal. The patients understand that their names and initials will not be published and due efforts will be made to conceal their identity, but anonymity cannot be guaranteed.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Pynn BR, Sands TD, Bradley G. Benign cementoblastoma: A case report. J Can Dent Assoc. 2001;67:260–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Subramani V, Narasimhan M, Ramalingam S, Anandan S, Ranganathan S. Revisiting cementoblastoma with a rare case presentation. Case Rep Pathol. 2017;2017:8248691. doi: 10.1155/2017/8248691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brannon RB, Fowler CB, Carpenter WM, Corio RL. Cementoblastoma: An innocuous neoplasm? A clinicopathologic study of 44 cases and review of the literature with special emphasis on recurrence. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2002;93:311–20. doi: 10.1067/moe.2002.121993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Neville BW, Damm DD, Allen CM, Bouquot JE. Oral and Maxillofacial Pathology. 2nd ed. Ch. 14. Philadelphia, Pa, USA: W.B. Saunders; 2002. Bone pathology; pp. 570–1. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chrcanovic BR, Gomez RS. Cementoblastoma: An updated analysis of 258 cases reported in the literature. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2017;45:1759–66. doi: 10.1016/j.jcms.2017.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chaput A, Marc A. Un cas de cementome localize sur une molaire temporaire. SSO Schweiz Monatsschr Zahnheilkd. 1965;75:48–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vilasco J, Mazère J, Douesnard JC, Loubière R. A case of cementoblastoma. Rev Stomatol Chir Maxillofac. 1969;70:329–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zachariades N, Skordalaki A, Papanicolaou S, Androulakakis E, Bournias M. Cementoblastoma: Review of the literature and report of a case in a 7 year-old girl. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1985;23:456–61. doi: 10.1016/0266-4356(85)90031-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Herzog S. Benign cementoblastoma associated with the primary dentition. J Oral Med. 1987;42:106–8. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cannell H. Cementoblastoma of deciduous tooth. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1991;71:648. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(91)90379-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schafer TE, Singh B, Myers DR. Cementoblastoma associated with a primary tooth: A rare pediatric lesion. Pediatr Dent. 2001;23:351–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ohki K, Kumamoto H, Nitta Y, Nagasaka H, Kawamura H, Ooya K. Benign cementoblastoma involving multiple maxillary teeth: Report of a case with a review of the literature. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2004;97:53–8. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2003.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lemberg K, Hagström J, Rihtniemi J, Soikkonen K. Benign cementoblastoma in a primary lower molar, a rarity. Dentomaxillofac Radiol. 2007;36:364–6. doi: 10.1259/dmfr/58249657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vieira AP, Meneses JM, Jr, Maia RL. Cementoblastoma related to a primary tooth: A case report. J Oral Pathol Med. 2007;36:117–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.2007.00465.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.de Noronha Santos Netto J, Marques AA, da Costa DO, de Queiroz Chaves Lourenço S. A rare case of cementoblastoma associated with the primary dentition. Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2012;16:399–402. doi: 10.1007/s10006-011-0309-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Solomon MC, Rehani SH, Valiathan M, Rao L, Raghu AR, Rao NN, et al. Benign cementoblastoma involving multiple deciduous and permanent teeth of maxilla-a case report. Oral Maxillofac Pathol J. 2012;3:258–63. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Monti LM, Souza AM, Soubhia AM, Jorge WA, Anichinno M, Da Fonseca GL. Cementoblastoma: A case report in deciduous tooth. Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2013;17:145–9. doi: 10.1007/s10006-012-0347-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Urs AB, Singh H, Rawat G, Mohanty S, Ghosh S. Cementoblastoma solely involving maxillary primary teeth – A rare presentation. J Clin Pediatr Dent. 2016;40:147–51. doi: 10.17796/1053-4628-40.2.147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nuvvula S, Manepalli S, Mohapatra A, Mallineni SK. Cementoblastoma relating to right mandibular second primary molar. Case Rep Dent. 2016;2016:2319890. doi: 10.1155/2016/2319890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Javed A, Hussain Shah SM. Giant cementoblastoma of left maxilla involving A deciduous molar. J Ayub Med Coll Abbottabad. 2017;29:145–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nagvekar S, Syed S, Spadigam A, Dhupar A. Rare presentation of cementoblastoma associated with the deciduous maxillary second molar. BMJ Case Rep 2017. 2017 doi: 10.1136/bcr-2017-221977. pii: bcr-2017-221977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mohammadi F, Aminishakib P, Niknami M, Razi Avarzamani A, Derakhshan S. Benign cementoblastoma involving deciduous and permanent mandibular molars: A case report. Iran J Med Sci. 2018;43:664–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tamme T, Soots M, Kulla A, Karu K, Hanstein SM, Sokk A, et al. Odontogenic tumours, a collaborative retrospective study of 75 cases covering more than 25 years from Estonia. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2004;32:161–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jcms.2003.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Papageorge MB, Cataldo E, Nghiem FT. Cementoblastoma involving multiple deciduous teeth. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1987;63:602–5. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(87)90236-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kumar S, Prabhakar V, Angra R. Infected cementoblastoma. Natl J Maxillofac Surg. 2011;2:200–3. doi: 10.4103/0975-5950.94482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sumer M, Gunduz K, Sumer AP, Gunhan O. Benign cementoblastoma: A case report. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2006;11:E483–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sapp JP, Eversole LR, Wysocki GP. Contemporary Oral and Maxillofacial Pathology. Ch. 5. St Louis: Mosby; 2004. Odontogenic tumors; pp. 153–4. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kalburge JV, Kulkarni MV, Kini Y. Cementoblastoma affecting the mandibular first molar-a case report. Pravara Med Rev. 2010;5:33–7. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Marx R, Stern D. 2nd ed. Ch. 15. II. Illinois: Quintessence Publishing House; 2012. Odontogenic Tumours, In: Oral and Maxillofacial Pathology: A Rationale for Diagnosis and Treatment; pp. 704–6. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Monks FT, Bradley JC, Turner EP. Central osteoblastoma or cementoblastoma? A case report and 12 year review. Br J Oral Surg. 1981;19:29–37. doi: 10.1016/0007-117x(81)90018-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Curé JK, Vattoth S, Shah R. Radiopaque jaw lesions: An approach to the differential diagnosis. Radiographics. 2012;32:1909–25. doi: 10.1148/rg.327125003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Napier Souza L, Monteiro Lima Júnior S, Garcia Santos Pimenta FJ, Rodrigues Antunes Souza AC, Santiago Gomez R. Atypical hypercementosis versus cementoblastoma. Dentomaxillofac Radiol. 2004;33:267–70. doi: 10.1259/dmfr/30077628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cundiff EJ., 2nd Developing cementoblastoma: Case report and update of differential diagnosis. Quintessence Int. 2000;31:191–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sharma N. Benign cementoblastoma: A rare case report with review of literature. Contemp Clin Dent. 2014;5:92–4. doi: 10.4103/0976-237X.128679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mudhiraj PV, Vanje MM, Reddy BN, Ahmed SA, Suri C, Taveer S, et al. Nature of hard tissues in oral pathological lesions – Using modified Gallego's stain. J Clin Diagn Res. 2017;11:ZC13–5. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2017/25244.9566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]