Abstract

Background:

One justification for marijuana legalization has been to reduce existing disparities in marijuana-related arrests for African Americans.

Objective:

Describe changes in adult marijuana arrest rates and disparities in rates for African Americans in Washington State (WA) after legalization of possession of small amounts of marijuana for 21+ year olds in December 2012, and after marijuana retail market opening in July 2014.

Methods:

We used 2012–2015 National Incident Based Reporting System data to identify marijuana-related arrests. Negative binomial regression models were fit to examine monthly marijuana arrest rates over time, and to test for differences between African Americans and Whites, adjusting for age and sex.

Results:

Among those 21+ years old overall, marijuana arrest rates were dramatically lower after legalization of possession, and did not change significantly after the retail market opened. The marijuana arrest rates for African Americans did drop markedly and the absolute disparities decreased, but the relative disparities grew: from a rate 2.5 times higher than Whites to 5 times higher after the retail market opened. Among 18–20 year olds overall, marijuana arrest rates dropped, but not as dramatically as among older adults; the absolute disparities decreased, but the relative disparities did not change significantly.

Conclusions:

Marijuana arrest rates among both African American and White adults decreased significantly with legalization of possession, and stayed at a dramatically lower rate after the marijuana retail market opened. However, relative disparities in marijuana arrest rates for African Americans increased for those of legal age, and remained unchanged for younger adults.

Keywords: Cannabis use, marijuana use, criminal justice, inequities, marijuana law, cannabis law, policy research, race

Background

In 2012, Washington State (WA) legalized the production, sale, and adult (21 years and older) possession of small amounts of marijuana for recreational use through Initiative 502 (I-502). One argument in support of I-502 was its potential to reduce disproportionate marijuana arrest rates for African Americans (Levinson, Pflaumer, & Alsdorf, 2011). Indeed, the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) and its Washington State affiliate reported marijuana possession arrests consistently overrepresented African Americans nationally and in WA (ACLU, 2013; ACLU WA, 2014). Beyond possible conviction and punishment, the indirect consequences of arrest can include major collateral effects such as reduced prospects for employment, housing, education, and public benefits (Berson, 2013; Chin, 2002).

After implementation of I-502, arrests were expected to drop for marijuana possession, as well as for manufacturing and selling, given an illegal marijuana business could now be legal. How I-502 would affect disparities in arrests, however, was less clear. To our knowledge, no studies examining changes in racial disparities in marijuana arrests after legalizing marijuana to this extent have been published in the peer-reviewed literature, but several online reports do exist. Two reports from Colorado (Gettman, 2015; Reed, 2018) found large decreases in marijuana arrests after legalization of adult possession and the opening of the marijuana retail market, but the overall disparities for African Americans persisted. The State of Oregon published a report examining data on adults booked for arrests after legalization of possession and after the opening of the retail market – they found persistent age-adjusted disparities for African Americans (Oregon Public Health Division, 2016). WA ACLU analyzed court data on prosecutions for misdemeanor marijuana possession and found persistent disparities for African Americans in the year after legalization of possession (ACLU WA, 2014).

In the current study, we describe changes in adult marijuana arrest rates in WA after legalization of possession of small amounts of marijuana in December 2012, as well as after the opening of a marijuana retail market in July 2014. We also assess changes in disparities in arrest rates for African Americans relative to Whites.

Methods

Study population

We used 2012–2015 National Incident Based Reporting System (NIBRS) data to identify marijuana-related arrests (FBI, n.d.; NACJD, 2018) for WA. NIBRS includes detail for reported criminal incidents, including violations/infractions and more serious offenses, which are submitted by local law enforcement agencies to the FBI. We chose 2012 as the baseline because about 70% of agencies reported to NIBRS then; in 2011, only 52% did (WASPC, n.d.). WA NIBRS data did not include traffic incidents during this time. We included only WA agencies that reported for all four years (154 of 221 agencies who ever reported). These 154 agencies report for approximately 64% of the state population, excluding tribal government-controlled land.

Measures

Crime incidents

I-502 eliminated crimes for adult (21+) possession of small amounts of marijuana, possession of marijuana paraphernalia, and licensed manufacture, delivery, and sale of marijuana. Unlicensed trafficking and marijuana-impaired driving remained prohibited; new prohibitions against public consumption and consumption in a vehicle were introduced.

A marijuana-specific incident was identified in NIBRS by selecting police incidents that: 1) contained at least one drug or narcotic violation; 2) had marijuana listed as the suspected drug type in the property segment; and, 3) resulted in at least one arrest.

We identified 9,428 marijuana-related incidents in NIBRS that resulted in at least one arrest (which included citations). These included arrests for violations/infractions and more serious offenses. Twenty percent of incidents resulted in more than one arrest (n = 1,868). We randomly selected one arrestee per incident, and used their demographics for analyses to avoid artificially inflating arrest rates. Up to nine crime types are listed for each NIBRS incident, but these are not linked to a specific arrestee within that incident.

Records were excluded that were missing race and ethnicity or demographic data (n = 129), or were reported by tribal law enforcement agencies (n = 108) or from unidentified law enforcement (n = 7). We were left with 9,184 marijuana-related arrestees. We further restricted analysis to arrestees over age 18. The final numbers for analyses were 3,299 arrestees over 21 years old and 2,451 arrestees 18–20 years old. While our study focused on comparing Whites and African Americans, we included all arrestees in the analyses to add stability to our trend estimates.

Population denominators

We used unbridged annual 2012–2015 small-area population estimates (Washington State OFM, 2016) for a given sex, race/ethnicity, and age group linked to law enforcement coverage areas in NIBRS. If someone identified their ethnicity as Latino, they were excluded from the race categories. We used population estimates for people who reported being of any race alone, or in combination with other races, since the census is believed to undercount the number of people from communities of color (U.S. Census Bureau, 2012).

Policy

We examined two marijuana policy measures: legalization of possession of small amounts of marijuana (referred to as ‘legalization of possession’) and market opening. Legalization of possession was coded as ‘1’ starting in December 2012 and ‘0’ before. Similarly, retail market opening was coded as ‘1’ starting in July 2014 and ‘0’ before.

Supplemental data

We used data from the 2012–2015 WA Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS), a statewide survey of adults 18 years and older (CDC, 2018), to estimate the prevalence of marijuana use. Current use was defined as use on one or more of the last 30 days. Race was self-reported, and based on ‘preferred race’ for adults who reported multiple races.

Statistical methods

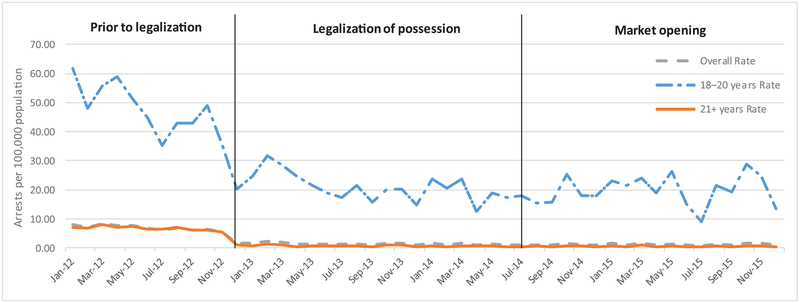

To describe overall trends combined across race, we plotted monthly marijuana arrest rates over time for adults of legal age (21+) and those younger (18–20).

Negative binomial regression models were fit to examine monthly marijuana arrest rates over time. We fit one model for adults of legal age and one for those younger. For the model among those of legal age, the outcome was monthly number of arrests within each race, gender, and age group (defined by 21–24, 25–44, 45–64, 65+). We used as an offset the natural log of the population count for each group for the NIBRS coverage area. Independent variables included the main effects for pre/post legalization of possession and the retail market opening. We also adjusted for race, age, gender, and a linear time trend by including these traits as independent variables. The model for younger adults (18–20) was similar except we did not include age group as an independent variable.

To examine changes in racial disparities over time between African Americans and Whites, we fit one additional negative binomial regression model for adults of legal age and one for those younger. Specifically, we added race effects specific to each of the three time periods: 1) pre-legalization; 2) post-legalization and pre-market opening; and, 3) post-market opening. We used linear contrasts to see if these race effects changed across the time periods.

As part of exploratory analyses, we provide descriptive statistics on crime type for 2012 and 2015 by race.

Results

Examining data from 2012 to 2015, we found marijuana arrest rates among adults dropped dramatically after legalization of possession (Figure 1). Our models indicated that among 21+ year olds, marijuana arrest rates dropped by 87% after legalization of possession (p < .001) and did not change significantly after the retail market opened (p = .73). Among 18–20 year olds, the marijuana arrest rates dropped by 46% after legalization of possession (p < .001); they then increased by about 21% after the retail market opening, but this increase did not quite reach statistical significance (p = .10).

Figure 1.

Marijuana-related arrests among adults over time for those of legal age (21+) and those underage (18–20), Washington State,* 2012–2015.

Notes. Arrests include citations. We included only one arrestee per incident. Data are limited to those areas of the state reporting to the National Incident Based Reporting System.

Additional models examining disparities over time suggested the changes in marijuana arrests rates varied considerably by race (Table 1). Marijuana arrest rates for African Americans 21+ years old dropped after legalization of possession and the absolute disparities decreased, but the relative disparities grew: from a rate 2.5 times higher than Whites to 5 times higher after the retail market opened. For underage adults, marijuana arrest rates for African Americans dropped after legalization of possession and the absolute disparities decreased, but remained nearly twice as high as for Whites.

Table 1.

Disparities in arresta rates for African Americans compared to Whites over timeb, stratified by age, 2012–2015, Washington State.

| Time period | Population group | No. of Arrests | Average monthly arrest rate | Adjusted RR for African Americans vs. Whites (95% CI)c | p-value comparing to RR before legalization of possession |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 21 + year olds (legal age) | |||||

| Before legalization of possession (January 2012–November 2012) | African Americans | 342 | 22.4/100,000 | 2.5 (2.1–2.8) | — |

| Whites | 1814 | 6.3/100,000 | — | ||

| After legalization of possession and before marijuana retail market opened (December 2012–June 2014) | African Americans | 73 | 2.7/100,000 | 3.3 (2.5–4.3) | .064 |

| Whites | 300 | 0.6/100,000 | — | ||

| After marijuana retail market opened (July 2014–December 2015) | African Americans | 77 | 2.9/100,000 | 5.2 (3.9–6.8) | <.001 |

| Whites | 193 | 0.4/100,000 | |||

| 18–20 year olds (underage use) | |||||

| Before legalization of possession (January 2012–November 2012) | African Americans | 112 | 89.5/100,000 | 1.7 (1.4–2.1) | — |

| Whites | 700 | 50.9/100,000 | |||

| After legalization of possession and before marijuana retail market opened (December 2012–June 2014) | African Americans | 88 | 40.7/100,000 | 1.9 (1.5–2.4) | .534 |

| Whites | 483 | 21.0/100,000 | |||

| After marijuana retail market opened (July 2014–December 2015) | African Americans | 71 | 34.0/100,000 | 1.7 (1.3–2.2) | .932 |

| Whites | 431 | 20.0/100,000 |

Note: RR, rate ratio; CI, confidence interval.

Arrests include citations. We included only one arrestee per incident.

Those who were identified as Latino were not included in the African American or White racial/ethnic categories.

RR from a negative binomial regression model, adjusting for gender, time, and the main effects of policies.

Descriptive statistics on crime type (Table 2) suggest the relative decline between 2012 and 2015 in the number of arrestees associated with an incident for possessing/concealing and using/consuming were similar for African Americans and Whites. In contrast, the number of arrestees associated with an incident for distributing/selling dropped among Whites by 67%, but showed little change among African Americans.

Table 2.

Number of arrestees associated with incidents having specific crime types,a over time, by race, among adults 18 years and over, Washington State.

| Crime typeb | Non-Latino White | Non-Latino African American | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of arrestees 2012 (n = 2564) | No. of arrestees 2015 (n = 416) | Percentage change from 2012 to 2015 | No. of arrestees 2012 (n = 465) | No. of arrestees 2015 (n = 106) | Percentage change from 2012 to 2015 | |

| Possessing/concealing | 2238 | 343 | −85% | 390 | 80 | −79% |

| Using/consuming | 440 | 100 | −77% | 56 | 11 | −80% |

| Buying/receiving | 16 | 9 | −44% | 2 | 1 | −50% |

| Cultivating/manufacturing | 40 | 11 | −73% | 3 | 0 | −100% |

| Transporting/transmitting | 36 | 7 | −81% | 10 | 2 | −80% |

| Distributing/selling | 124 | 41 | −67% | 43 | 41 | −5% |

| Other | 47 | 14 | −70% | 9 | 9 | 0% |

Up to 9 crime types can be listed for each incident in NIBRS. In 2012 (and 2015), 1228 (193) White and 145 (44) Black arrestees were associated with incidents having >1 crime type specified. All crime types associated with an incident are listed in this table.

Other includes ‘operating/promoting’, ‘other gang’ and ‘none/unknown gang’.

The prevalence of current marijuana use in WA during 2012–2015 was not significantly different between non-Latino African Americans (11.3%, n = 807) and non-Latino Whites (10.3%, n = 40,657; p = .49) The results were consistent after direct age-adjustment.

Discussion

Marijuana legalization in WA was expected by advocates of I-502 to reduce racial disparities in marijuana arrest rates. We found marijuana arrests rates among adults dropped dramatically after legalization of possession among both African Americans and Whites, and the absolute disparities decreased. However, the magnitude of relative disparities grew for African Americans among those of legal age (21+), and the prior relative disparities disadvantageous to African American did not change significantly among 18–20 year olds.

The large reductions in marijuana arrests in WA demonstrate how drug policy reform can indeed have a substantial positive social impact. The American Public Health Association recognizes that substance abuse is primarily a public health issue, and holds the official position that drug possession and use should not be criminalized (APHA, 2017). Indeed, because of marijuana legalization, many Washingtonians today – both African American and White – no longer experience the consequences from a marijuana drug arrest and collateral consequences.

Our findings also suggest, however, that marijuana legalization is not a sufficient public policy action to accomplish the elimination of racial inequities in arrests. They provide evidence of persistent disparities in marijuana arrests for African Americans after legalization, as found in reports from other states (Gettman, 2015; Oregon Public Health Division, 2016). The disparities persisted in the current study despite reported marijuana use being similar for African Americans and Whites. Some research suggests that African Americans may be less likely to report substance use on surveys than Whites (Fendrich & Johnson, 2005). However, to account for the disparities in arrest rates documented in the current study, the true marijuana prevalence among African Americans would need to be five times higher than Whites; this is extremely unlikely.

There are several limitations to this study. First, our results are only generalizable to areas in WA reporting to NIBRS, comprising about two thirds of the state’s population. Second, about 5% of the WA population is African American (U.S. Census Bureau, 2015); results could be different in more diverse states. Third, denominator data for arrest rates were based on census counts for races ‘alone or in combination with another racial group’ so the rates here could be lower than the true value. Fourth, arrest rates are likely underestimates because we randomly selected one arrestee per incident for analyses to be conservative. Last, we focused on statewide effects of the marijuana policies, but about 30% of the population lived in areas still banning retail sales of marijuana as of June 2016 (Dilley, Hitchcock, McGroder, Greto, & Richardson, 2017).

The underlying cause of the disparities in marijuana-related arrests – even after marijuana legalization – is an area for further study. While our numbers on specific crime types by race and year were rather small, exploratory analyses were suggestive that racial disparities are present. Specifically, there was little reduction between 2012 and 2015 in the number of African American arrestees associated with an incident for distributing/selling, even though there was a large reduction for Whites during this period. The reason that racial disparities increased after marijuana legalization appears to be due to the fact that African Americans were more likely to be arrested for marijuana distribution/selling than Whites. The illegal marijuana market could be a contributing factor. Growing, manufacturing and selling retail marijuana has become a profitable industry, but concerns have been raised about communities of color being underrepresented in this industry (Young, 2016). Advocates are working for more equality in the industry (MCBA, 2018), and related policies to promote equity have been passed in other states (City of Oakland, 2019).

Reasons for the long-standing disproportionality in drug-related arrests for African Americans examined in prior research include differences in drug of choice, location and visibility of crime, and bias in enforcement (Beckett, Nyrop, & Pfingst, 2006). Efforts are under way nationally to address bias in enforcement. For example, implicit bias trainings are being conducted among police (Yates, 2016). In addition, Ferrer and Connolly (2018) highlight the importance of addressing disparities in drug-related arrests not only by fixing our criminal justice system, but also by addressing system issues perpetuating social inequities in our society.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Clyde Dent, PhD, for his advice on the statistical methods; Joan Smith and Lynn Addington, PhD, for providing guidance on using the NIBRS dataset; Curtis Mack, BA, and Susan Richardson, MPH, for creating files with population counts; and Erik Everson, MPH, for analyzing the BRFSS data.

Funding

This study was supported by the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) of the National Institutes of Health under award number 1R01DA039293. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU). (2013). The war on marijuana in black and white. Retrieved from https://www.aclu.org/report/report-war-marijuana-black-and-white

- American Civil Liberties Union Washington (ACLU WA). (2014). Court filings for adult marijuana possession plummet. Retrieved from https://www.aclu-wa.org/news/court-filings-adult-marijuana-possession-plummet

- American Public Health Association (APHA). (2017). Defining and implementing a public health response to drug use and misuse. Retrieved from https://www.apha.org/policies-and-advocacy/public-health-policy-statements/policy-database/2014/07/08/08/04/defining-and-implementing-a-public-health-response-to-drug-use-and-misuse

- Beckett K, Nyrop K, & Pfingst L (2006). Race, drugs, and policing: Understanding disparities in drug delivery arrests. Criminology, 44(1), 105–137. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-9125.2006.00044.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Berson SB (2013). Beyond the sentence: Understanding collateral consequences. National Institute of Justice Journal, 272, 25–28. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). (2018). Behavioral risk factor surveillance system. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/brfss/index.html

- Chin GJ (2002). Race, the war on drugs, and the collateral consequences of criminal conviction. Journal of Gender, Race, & Justice, 6, 253–275. [Google Scholar]

- City of Oakland. (2019). Become an equity application or incubator. Retrieved from http://www2.oaklandnet.com/government/o/CityAdministration/cannabis-permits/OAK068455

- U.S. Census Bureau. (2012). Census Bureau releases estimates of undercount and overcount in the 2010 Census. Retrieved from https://www.census.gov/newsroom/releases/archives/2010_census/cb12-95.html

- U.S. Census Bureau. (2015). Selected demographic characteristics, 2011–2015 American Community Survey 5-year estimates. Retrieved from https://factfinder.census.gov/faces/tableservices/jsf/pages/productview.xhtml?pid=ACS_15_AIA_DP05&prodType=table

- Dilley JA, Hitchcock L, McGroder N, Greto L, & Richardson SM (2017). Community-level policy responses to state marijuana legalization in Washington State. International Journal of Drug Policy, 42, 102–108. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2017.02.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI). (n.d.). NIBRS overview. Retrieved from https://ucr.fbi.gov/nibrs-overview

- Fendrich M, & Johnson TP (2005). Race/ethnicity differences in validity of self-reported drug use: Results from a household survey. Journal of Urban Health, 82(Suppl 3), ii67–ii81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrer B, & Connolly JM (2018). Racial inequities in drug arrests: Treatment in lieu of and after incarceration. American Journal of Public Health, 108(8), 968–969. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2018.304575 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gettman J (2015). Marijuana arrests in Colorado after the passage of Amendment 64. Retrieved from The Drug Policy Alliance website: https://www.drugpolicy.org/sites/default/files/Colorado_Marijuana_Arrests_After_Amendment_64.pdf

- Levinson A, Pflaumer K, & Alsdorf R (2011, November 11). Sign Initiative 502 to put marijuana legalization before state Legislature. Seattle Times; Retrieved from https://www.seattletimes.com/opinion/sign-initiative-502-toput-marijuana-legalization-before-state-legislature/ [Google Scholar]

- Minority Cannabis Business Association (MCBA). (2018). What we do. Retrieved from https://minoritycannabis.org/what-we-do/

- National Archive of Criminal Justice Data (NACJD). (2018). Resource guide: National Incident-Based Reporting. Retrieved from https://www.icpsr.umich.edu/icpsrweb/NACJD/NIBRS/

- Oregon Public Health Division. (2016). Marijuana report: Marijuana use, attitudes and health effects in Oregon, December 2016. Portland, OR: Oregon Health Authority; Retrieved from https://apps.state.or.us/Forms/Served/le8509b.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Reed J (2018). Impacts of marijuana legalization in Colorado: A report pursuant to senate bill 13–283. Retrieved from http://cdpsdocs.state.co.us/ors/docs/reports/2018-SB-13-283_report.pdf

- Washington Association of Sheriffs and Police Chiefs (WASPC). (n.d.). The Crime in Washington 2011 Annual Report. Retrieved from https://www.waspc.org/assets/CJIS/2011_ciw.pdf

- Washington State Office of Financial Management, Forecasting Division (Washington State OFM). (2016). Small area demographic estimates: Block groups [data file]. Retrieved from https://www.ofm.wa.gov/washington-data-research/population-demographics/population-estimates/estimates-april-1-population-age-sex-race-and-hispanic-origin

- Yates S (2016). Memorandum for all department law enforcement agencies and prosecutors. Washington, DC: Retrieved from U.S. Department of Justice website: https://www.justice.gov/opa/file/871116/download [Google Scholar]

- Young B (2016, July 1). Minorities, punished most by war on drugs, underrepresented in legal pot. Seattle Times; Retrieved from https://www.seattletimes.com/seattle-news/marijuana/blacks-latinos-underrepresented-in-pot-shop-ownership/ [Google Scholar]