Article summary:

Antibiotic prescribing has become viewed as a patient safety and quality of care issue. We analyzed quality measures related to appropriate antibiotic prescribing and testing.

Introduction

Antibiotic resistance has become one of the most pressing public health issues of our time. In 2013, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) published a report that quantified the dangers of antibiotic resistance in the United States. This report revealed a staggering statistic: at least 2 million illnesses and 23,000 deaths can be attributed each year to serious bacterial infections that are resistant to one or more antibiotics[1]. It is well documented that antibiotic use is a main driver of antibiotic resistance [2–4]. Antibiotics are life-saving drugs that are essential for treating bacterial illnesses, but unnecessary antibiotic use for viral illnesses increases selective pressure that contributes to antibiotic resistance. Though antibiotic prescribing for children has improved since the 1990s, over half of all antibiotic prescriptions in the outpatient setting are still written for mild respiratory infections, many of which are caused by viruses [5, 6]. Antibiotic overprescribing also contributes to avoidable adverse drug events, such as Clostridium difficile infections [7, 8].

Antibiotic prescribing has become increasingly viewed as a patient safety and quality of care issue. The Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set (HEDIS) contains many healthcare quality measures. According to the National Committee for Quality Assurance (NCQA), HEDIS measures are used by more than 90 percent of U.S. health plans to measure performance on important dimensions of care and service and are also used by public health policy makers, the public, and the health plans themselves to identify high performing plans and to focus improvement efforts[9]. HEDIS measures cover a wide variety of health care performance issues such as asthma medication use, breast cancer screening and childhood and adolescent immunization status. Participating health plans report HEDIS data annually through surveys, medical chart reviews and insurance claims and results are audited by an NCQA approved auditing firm prior to public reporting [9].

We analyzed two HEDIS measures related to appropriate antibiotic prescribing (upper respiratory infection in children and acute bronchitis in adults) and a measure related to appropriate testing to guide antibiotic prescribing (pharyngitis testing). The primary objectives of this study were to assess overall health plan performance on the three HEDIS measures for 2008–2012 and explore potential variation between health plans. Prior studies in the United States have shown geographic variation in antibiotic prescribing [10, 11], therefore we also wanted to explore whether health plan performance on these three measures varied geographically.

Methods

We analyzed the following three HEDIS measures: 1) Appropriate Testing for Children with Pharyngitis (pharyngitis testing), defined as the proper diagnosis of streptococcal pharyngitis for children between 2 and 18 years of age. This requires a diagnosis of pharyngitis, an antibiotic prescribed and a group A streptococcus (strep) test administered for the episode in eligible children; 2) Appropriate Treatment for Children with Upper Respiratory Infections (URI), defined as the percent of antibiotic prescriptions for eligible children between 3 months and 18 years of age who were diagnosed with URI (common cold) and not prescribed an antibiotic on or within three days of the episode date; and 3) Avoidance of Antibiotic Treatment in Adults with Acute Bronchitis (bronchitis), defined as the percent of eligible adults diagnosed with acute bronchitis and not prescribed an antibiotic. For all three measures, a higher percent indicates better performance. The technical specifications for the measures, including how eligible populations are determined and reported by participating health plans, have been previously published by NCQA [12].

We obtained a dataset from NCQA containing the three measures for the years 2008–2012. This dataset included commercial health plans only (excluded Medicaid and Medicare) and all lines of business (Health Maintenance Organization (HMO), Preferred Provider Organization (PPO) and Point of Service (POS)) [13]. The data included confidence intervals for each measure and for each year according to health plan. We also received national, U.S. Census division [14] and state means and medians for each measure. Not every health plan reported data for each relevant measure for each year; therefore some health plans and states are missing data for one or more measures in any given year. No identifying characteristics related to the individual health plans were included in this analysis, as the intent was to learn more about the overall performance on the measures of interest and not to identify specific health plans by name or to provide a ranking of individual plans based on performance.

We first assessed whether there were extreme observations, or outliers, in the data at the individual health plan level. We computed simple statistics describing the variation of the individual plan rates using mean and standard deviation by year. We determined if there was a decreasing or increasing linear trend in the average of each relevant HEDIS measure from 2008 to 2012 and explored variability between and within health plans over time. We also performed descriptive statistics based on whether the reporting product was HMO, PPO, POS or a combination of these to determine if this had an impact on performance. However, we did not perform descriptive statistics for plans with sample sizes of less than 10, so the reporting products included in these analyses were HMO, HMO/POS combined, and PPO. We also determined whether there were differences in mean rates among these three reporting products for each HEDIS measure by year using SAS Proc GLM to account for unequal sample sizes. For multiple comparisons, we also adjusted means using Tukey method. We also explored geographic variation in HEDIS measure performance by census division for all years (2005–2012) using the mean for each measure in each census division for each year. Data management and all analyses were performed using SAS 9.3.

Results

During 2008–2012, an average of 373 (347–394) individual plans reported on the three measures to NCQA (Table 1). Wide variations were observed at the individual health plan level within measures for years 2008–2012. Across all years and all reporting health plans, the overall mean of children tested for group A Streptococcus and prescribed an antibiotic (pharyngitis testing) was 77.0% (range: 2.23–96.6%). For URI, the mean percent of children treated appropriately was 84.0% (range: 31.1–99.4%). The avoidance of antibiotic treatment for adults with bronchitis was 24.0% (range: 7.4–90.5%).

Table 1.

Health plan performance (%) on selected HEDIS measures, 2008–2012

| Year | Number of participating health plans |

Mean % | Median % | Minimum % | Maximum% |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Appropriate Testing for Children with Pharyngitis | |||||

| 2008 | 375 | 74.6 | 76.1 | 35.2 | 96.0 |

| 2009 | 371 | 75.7 | 77.2 | 37.8 | 95.2 |

| 2010 | 392 | 76.9 | 77.8 | 41.0 | 96.4 |

| 2011 | 347 | 78.0 | 78.7 | 39.1 | 96.1 |

| 2012 | 375 | 79.9 | 81.1 | 2.23 | 96.6 |

| Appropriate Treatment for Children with Upper Respiratory Infection | |||||

| 2008 | 374 | 83.8 | 84.7 | 49.9 | 98.5 |

| 2009 | 372 | 84.0 | 85.3 | 47.0 | 99.1 |

| 2010 | 393 | 83.6 | 85.0 | 31.1 | 97.8 |

| 2011 | 350 | 85.0 | 86.2 | 44.5 | 98.5 |

| 2012 | 376 | 83.4 | 84.7 | 44.7 | 99.4 |

| Avoidance of Antibiotic Treatment in Adults with Acute Bronchitis | |||||

| 2008 | 375 | 26.6 | 24.9 | 14.5 | 85.6 |

| 2009 | 375 | 25.4 | 23.5 | 9.9 | 90.5 |

| 2010 | 394 | 23.2 | 21.7 | 12.8 | 87.7 |

| 2011 | 349 | 22.1 | 20.7 | 8.5 | 75.0 |

| 2012 | 375 | 22.7 | 20.7 | 7.4 | 71.6 |

Testing for pharyngitis improved over time (p<0.01), with the lowest average of 74.6% in 2008 and the highest of 79.9% in 2012. The proportion of children not prescribed antibiotics for URI did not change significantly over the study period (p=0.93), the highest average was 85.0% in 2011 and the lowest was 83.4% in 2012. The bronchitis measure did not improve over the time period; in fact, there was a decreasing trend in antibiotic avoidance for bronchitis (p=0.03), with the highest (best) average of 26.6% in 2008 and the lowest (worst) of 22.1% in 2011, with no improvement in 2012 (22.7%).

Health plans that performed well on one measure often performed well on the other two measures. For example, the highest performing health plan for the adult bronchitis measure (71.7%) was also in the top five performing plans for both pharyngitis testing (95.6%) and URI (98.7%) in 2012.

We further examined the available descriptive statistics of the health plans for the three HEDIS measures by the product reported (HMO, PPO, POS, etc.) to determine if there were any differences in performance (Appendix A). For the adult bronchitis measure, in all years, a majority of the plans reported PPO (45%−48%), followed by HMO/POS combined (37%−40%), and HMO (12%−13%). Analyses on differences of mean rates show that in all years, HMO rates were significantly higher than ‘HMO/POS combined’ rates (p<0.001). Also, HMO rates were higher than PPO rates in 2010 to 2012 (p<0.001) but PPO rates were higher than ‘HMO/POS combined’ rates in 2008 and 2009 (p<0.001).

For pharyngitis testing, the distribution of health plans show a similar pattern to that of the adult bronchitis measure. Comparisons of mean rates show no statistically significant differences between HMO, PPO or HMO/POS combined. A similar distribution was also observed for children diagnosed with upper respiratory infections. Comparisons of mean rates show HMO rates were higher than PPO in all years (p<0.01). HMO rates were also higher than ‘HMO/POS combined’ rates in 2008 (p=0.04) and 2009 (p=0.03).

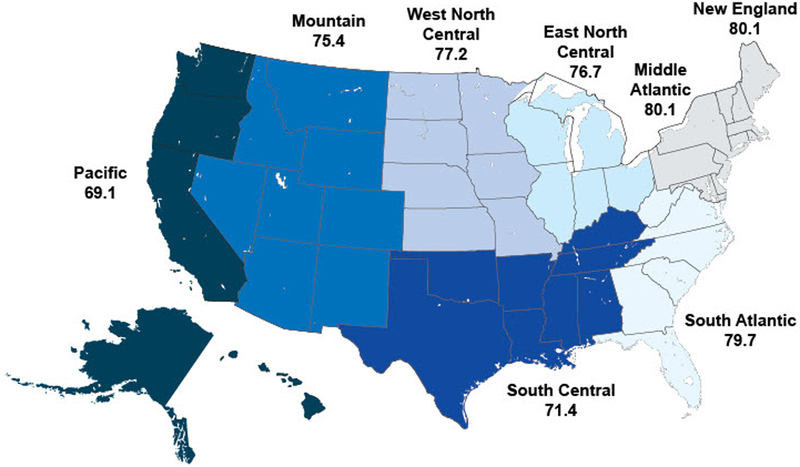

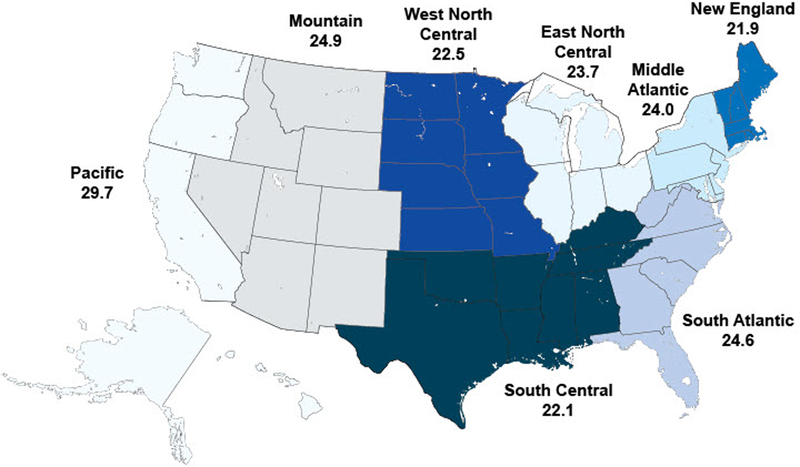

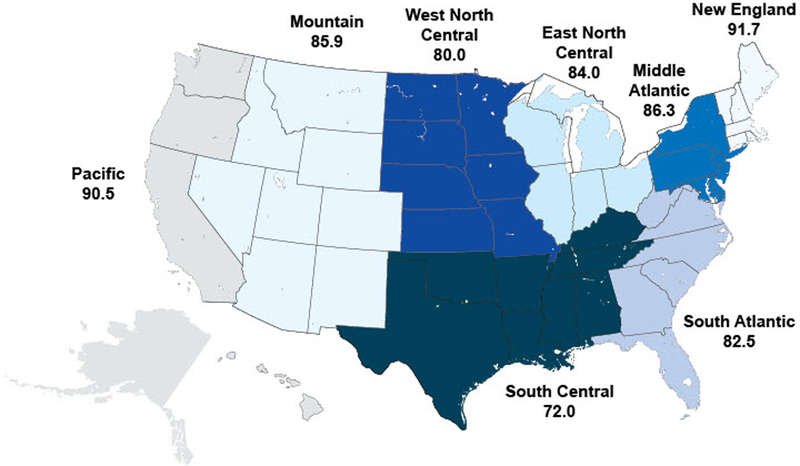

We also saw geographic variation between measures when looking at U.S. Census divisions across all years (Figure 1a-c). For pharyngitis testing, the highest performing division was New England (80.1%) and the lowest performing division was the Pacific (69.1%), followed by the South Central (71.4%). For children with upper respiratory infections, the highest performing division was New England (91.7%) and the worst performing division was South Central (72.0%). For bronchitis, all divisions performed poorly, ranging from a high of 29.7% in the Pacific division to a low of 21.9% in the New England division.

Figure 1.

a) Appropriate testing for children with pharyngitis (average), by Census division, 2008–2012

b) Appropriate testing for children with upper respiratory infection (average), by Census division, 2008–2012

c) Avoidance of antibiotic treatment in adults with acute bronchitis (average), by Census division, 2008–2012

DISCUSSION

Out of the three measures of interest, health plans consistently performed poorly on the adult bronchitis measure. In 2012, health plans reported an average antibiotic avoidance of 20.6% for adults with bronchitis. In other words, adults diagnosed with acute bronchitis were prescribed an antibiotic nearly 80% of the time even though antibiotics are not indicated for this diagnosis. Other studies using other datasets have shown that approximately 70% of visits for acute bronchitis result in antibiotic prescription [15, 16]. Health plans performed better on the two measures focused on the pediatric population (URI and pharyngitis testing). One reason for this could be because of programs and organizations promoting appropriate antibiotic use in the community such as CDC’s Get Smart: Know When Antibiotics Work program (www.cdc.gov/getsmart/community) and the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP). Both have provided appropriate antibiotic use guidance and education for parents of young children as well as resources for pediatric health care providers. In spite of the seemingly high rates of performance associated with these two pediatric measures, there is room for improvement. Common cold (URI) is always viral in nature, so an antibiotic is never necessary and the goal should be 100% antibiotic avoidance for common cold diagnoses.

We also observed differences in rates by line of business for both the adult bronchitis measure and the URI measure. For both measures, plans reporting HMO lines of business were in most instances reporting significantly higher rates than those by PPO or HMO/POS combined. It is unclear as to why we see these differences as antibiotic prescriptions are written by individual providers who may see many patients with varied insurance types and other payment methods over the course of a year. We believe it would be unlikely for a provider to prescribe differently based on the specific type of health insurance product (HMO, PPO, or some variation), though at least one study has found that among older adults, antibiotic prescribing increased when insurance coverage improved [17]. As the data for this analysis was commercial only and did not include Medicare or Medicaid patients, it is unclear if differences in insurance coverage are impacting HEDIS rates and this may be one area where further study is warranted.

We also observed wide geographic variation in health plan performance for the three measures. Previous studies have shown that antibiotic prescribing rates are higher in the South than in other parts of the country. Specifically, prescribing rates in some states in the South and through the Appalachian region of the country were more than double state prescribing rates in the Pacific Northwest [10, 11]. However, because these reports don’t contain diagnosis or visit-based data, it is difficult to assess whether providers in the South were more likely to prescribe inappropriately. Because the HEDIS quality measures are direct indicators of appropriate treatment and prescribing, our study confirms that inappropriate prescribing is higher in the South. This is important to both the understanding of this complex issue as well as to the planning of future antibiotic stewardship activities in the South. Improving antibiotic use is a national priority[18] and this information is useful for identifying where antibiotic stewardship programs are most needed. [10, 11].

In general, the highest performing plans tended to do well across all three measures and were consistent over time, leading us to conclude that there may be lessons learned that could be shared with plans that are not performing as well. There may then be opportunities to expand existing measures (e.g. measuring URI prescribing for all ages, not only the pediatric population) or creating new measures focused on appropriate antibiotic use (e.g. appropriate prescribing for sinusitis). Public health, advocacy groups, foundations, professional societies and others interested in improving antibiotic use in the outpatient setting should consider how existing quality measures and multi-stakeholder collaborations could be used to impact prescribing. One example of multi-stakeholder collaborations is California AWARE (http://www.thecmafoundation.org/Programs/AWARE), a joint effort between the California Medical Association Foundation, the California Department of Health Services, health plans in the state and others. The California AWARE program has focused on improving antibiotic prescribing rates in the state for many years using a number of different strategies, including educational tools and resources targeting providers as well as the general public and also by working closely with health plans to identify high prescribing providers to target for interventions.

Finally, interventions to improve antibiotic use should target providers that treat adults, specifically for the diagnosis of acute bronchitis, as progress has been minimal. Health care providers cite diagnostic uncertainty, time limitations (e.g. not enough time to communicate about appropriate use with patients), and patient demand as reasons for prescribing antibiotics even when they are not clinically indicated [19, 20]. Because guidelines and information on management of bronchitis have been available for many years, it may take more focused and deliberate efforts to engage adult providers. We are hopeful, however, that progress can be made based on the improvements seen in prescribing for children after a concerted effort was made to engage pediatric providers around this issue. Interventions at the clinician-level, such as audit and feedback, clinical decision support tools and active education strategies such as academic detailing may be useful for improving prescribing practices.

There were limitations associated with this analysis. As shown in Table 1, not every health plan reported data for every measure or for every year. Health plans may go out of business, relocate or choose not to report on these measures. Also, these data only include commercial lines of business within health plans and do not include Medicare or Medicaid lines of business, which may differ due to the unique populations represented. Additionally, the measures associated with antibiotic prescribing rely on data gathered from medical chart reviews, and specifically diagnostic codes. Diagnostic coding can be unreliable and is another limitation associated with this study.

With antibiotic resistant infections on the rise, and a strong interest and support by the White House to improve antibiotic stewardship with the release of the National Strategy for Combating Antibiotic-Resistant Bacteria[18], the National Action Plan for Combating Antibiotic-Resistant Bacteria[21]and a Presidential Executive Order[22], the time to focus efforts on improving prescribing practices in the outpatient setting is now. Armed with the knowledge of where inappropriate prescribing is most common and support for this topic on a national level, public health professionals, health plans, provider groups and other stakeholders invested in antibiotic stewardship can begin to deliberately focus interventions where improvement is most needed.

Supplementary Material

Take-away points:

Antibiotic prescribing has become viewed as a patient safety and quality of care issue. With antibiotic resistant infections on the rise, and national support to improve antibiotic use, the time to focus efforts on improving prescribing practices in the outpatient setting is now.

Explore opportunities to expand existing quality measures or create new measures focused on appropriate antibiotic use.

Share lessons learned from high performing plans with lower-performing plans.

Implement proven interventions to improve antibiotic use especially with providers that treat adults, as progress has been minimal in decreasing inappropriate antibiotic prescribing in the adult population.

Acknowledgments

No external funding was received.

References

- 1.Antibiotic Resistance Threats in the United States. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2013; CDC Website.

- 2.Hicks LA, Chien YW, Taylor TH Jr., Haber M, Klugman KP, Active Bacterial Core Surveillance T. Outpatient antibiotic prescribing and nonsusceptible Streptococcus pneumoniae in the United States, 1996–2003. Clinical infectious diseases : an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America 2011; 53(7): 631–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bronzwaer SL, Cars O, Buchholz U, et al. A European study on the relationship between antimicrobial use and antimicrobial resistance. Emerging infectious diseases 2002; 8(3): 278–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Costelloe C, Metcalfe C, Lovering A, Mant D, Hay AD. Effect of antibiotic prescribing in primary care on antimicrobial resistance in individual patients: systematic review and meta-analysis. Bmj 2010; 340: c2096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Grijalva CG, Nuorti JP, Griffin MR. Antibiotic prescription rates for acute respiratory tract infections in US ambulatory settings. JAMA : the journal of the American Medical Association 2009; 302(7): 758–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McCaig LFH LA; Roberts RM; Fairlie T A Office-Related Antibiotic Prescribing for Persons Aged ≤ 14 years - United States, 1993–1994 to 2007–2008. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 2011; 60(34): 1153–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shehab N, Patel PR, Srinivasan A, Budnitz DS. Emergency department visits for antibiotic-associated adverse events. Clinical infectious diseases : an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America 2008; 47(6): 735–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lessa FC, Mu Y, Bamberg WM, et al. Burden of Clostridium difficile infection in the United States. The New England journal of medicine 2015; 372(9): 825–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.NCQA. HEDIS and Quality Compass. Available at: http://www.ncqa.org/HEDISQualityMeasurement/WhatisHEDIS.aspx. Accessed November 5, 2014.

- 10.Hicks LA, Taylor TH, Jr., Hunkler RJ. U.S. outpatient antibiotic prescribing, 2010. The New England journal of medicine 2013; 368(15): 1461–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hicks LA, Bartoces MG, Roberts RM, et al. US Outpatient Antibiotic Prescribing Variation According to Geography, Patient Population, and Provider Specialty in 2011. Clinical infectious diseases : an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.NQF-Endorsed™ National Voluntary Consensus Standards for Physician-Focused Ambulatory Care APPENDIX A –NCQA Measure Technical Specifications. Available at: http://www.ncqa.org/Portals/0/HEDISQM/NQF_Posting_Appendix.pdf. Accessed December 1.

- 13.Understanding the difference between HMO, PPO and POS. Available at: http://www.insurance.com/health-insurance/health-insurance-basics/understanding-the-difference-between-hmo-ppo-and-pos.aspx. Accessed December 22, 2014.

- 14.Census Bureau Regions and Divisions Available at: http://www.census.gov/geo/maps-data/maps/pdfs/reference/us_regdiv.pdf Accessed December 22, 2014.

- 15.Albert RH. Diagnosis and treatment of acute bronchitis. American family physician 2010; 82(11): 1345–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Barnett ML, Linder JA. Antibiotic prescribing for adults with acute bronchitis in the united states, 1996–2010. JAMA : the journal of the American Medical Association 2014; 311(19): 2020–2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhang Y, Lee BY, Donohue JM. Ambulatory antibiotic use and prescription drug coverage in older adults. Archives of internal medicine 2010; 170(15): 1308–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.National Strategy to Combat Antibiotic Resistant Bacteria. Available at: https://www.whitehouse.gov/sites/default/files/docs/carb_national_strategy.pdf.

- 19.Teixeira Rodrigues A, Roque F, Falcão A, Figueiras A, Herdeiro MT. Understanding physician antibiotic prescribing behaviour: a systematic review of qualitative studies. International journal of antimicrobial agents 2013; 41(3): 203–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vanden Eng J, Marcus R, Hadler JL, et al. Consumer attitudes and use of antibiotics. Emerging infectious diseases 2003; 9(9): 1128–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.National Action Plan for Combating Antibiotic Resistant Bacteria. Available at: https://www.whitehouse.gov/sites/default/files/docs/national_action_plan_for_combating_antibotic-resistant_bacteria.pdf. Accessed November 20, 2015.

- 22.Executive Order -- Combating Antibiotic Resistant Bacteria. Available at: https://www.whitehouse.gov/the-press-office/2014/09/18/executive-order-combating-antibiotic-resistant-bacteria.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.