Abstract

Background and Aims

Whole-genome duplication (WGD) events are considered important driving forces of diversification. At least 11 out of 52 Brassicaceae tribes had independent mesopolyploid WGDs followed by diploidization processes. However, the association between mesopolyploidy and subsequent diversification is equivocal. Herein we show the results from a family-wide diversification analysis on Brassicaceae, and elaborate on the hypothesis that polyploidization per se is a fundamental driver in Brassicaceae evolution.

Methods

We established a time-calibrated chronogram based on whole plastid genomes comprising representative Brassicaceae taxa and published data spanning the entire Rosidae clade. This allowed us to set multiple calibration points and anchored various Brassicaceae taxa for subsequent downstream analyses. All major splits among Brassicaceae lineages were used in BEAST analyses of 48 individually analysed tribes comprising 2101 taxa in total using the internal transcribed spacers of nuclear ribosomal DNA. Diversification patterns were investigated on these tribe-wide chronograms using BAMM and were compared with family-wide data on genome size variation and species richness.

Key Results

Brassicaceae diverged 29.9 million years ago (Mya) during the Oligocene, and the majority of tribes started diversification in the Miocene with an average crown group age of about 12.5 Mya. This matches the cooling phase right after the Mid Miocene climatic optimum. Significant rate shifts were detected in 12 out of 52 tribes during the Mio- and Pliocene, decoupled from preceding mesopolyploid WGDs. Among the various factors analysed, the combined effect of tribal crown group age and net diversification rate (speciation minus extinction) is likely to explain sufficiently species richness across Brassicaceae tribes.

Conclusions

The onset of the evolutionary splits among tribes took place under cooler and drier conditions. Pleistocene glacial cycles may have contributed to the maintenance of high diversification rates. Rate shifts are not consistently associated with mesopolyploid WGD. We propose, therefore, that WGDs in general serve as a constant ‘pump’ for continuous and high species diversification.

Keywords: Angiosperm, BAMM, BEAST, Brassicaceae, diversification, genome size, ITS, plastome, polyploidization, speciation rate, species richness

INTRODUCTION

With the establishment of high-throughput sequencing technology and the release of the first reference land plant genomes such as arabidopsis, rice and tomato (Arabidopsis Genome Initiative, 2000; Yu et al., 2002), genome-wide analyses of land plants turned into a powerful tool not only to study phylogenetics and evolutionary history per se, but also to elucidate evolutionary principles of chromosome and genome evolution (Wendel et al., 2016). A major advantage of the use of high-throughput sequencing data is that now past polyploidization events can be identified and followed with high resolution (e.g. Mandáková and Lysak, 2018). The phenomenon of polyploidization in plants has for long been accepted to play an important role in plant diversification and evolution (Stebbins, 1950; Ehrendorfer, 1980; Soltis et al., 2003), and nowadays we can assume that any lineage of extant angiosperms most probably underwent multiple polyploidization events with a severe impact on subsequent diversification (Tank et al., 2015; Landis et al., 2018).

Whole-genome duplication (WGD) is a ubiquitous genetic mechanism throughout the history of angiosperms (Soltis et al., 2009). Depending on the age and progress of the diploidization processes, those past polyploidization events are classified as neopolyploid, mesopolyploid and paleopolyploid (Lysak and Koch, 2011; Mandáková and Lysak, 2018). Paleopolyploid and mesopolyploid WGDs were obscured by chromosomal and genetic diploidization processes including chromosome rearrangements, leading to chromosome number reduction, genome downsizing and diploid-like inheritance. Therefore, paleopolyploidization events are dozens and hundreds of million years old, and the most recent event in Brassicaceae (called At-α-duplication, Vision et al., 2000) dates back approx. 50 million years ago (Mya; Ren et al., 2018). Mesopolyploidization events are found in the range of 10–20 Mya (Mandáková and Lysak, 2018). Diploid-like genomes give rise to neopolyploid cytotypes and species via autopolyploidy and hybridization-driven allopolyploidy. Since neopolyploids, in particular, are easier to identify based on chromosome numbers, the frequency of polyploidy in angiosperms has been calculated to vary between 30 and 70 % (Müntzing, 1936; Darlington, 1937; Stebbins, 1950; Grant, 1981). Nowadays it is accepted, based on genome and transcriptome analyses (Jiao et al., 2011; Amborella Genome Project, 2013), that the ancestor of all extant angiosperms experienced a paleopolyploidization event, and that an increasing number of WGDs have been detected and are assumed to foster angiosperm evolution and diversification (e.g. Vanneste et al., 2014).

Whole-genome duplication is generally thought to provide potential evolvability that may be triggered by changing environmental conditions, to set the genetic background to evolve new key traits and characters (e.g. glucosinolate pathways in Brassicaceae; Hofberger et al., 2013) and thereby drive species diversification (Schranz et al., 2012; Clark and Donoghue, 2018). However, the connection between WGD and diversification is still equivocal. WGD followed by gene loss and diploidization has long been considered a prominent driving force for species diversification (Doyle et al., 2008; Soltis et al., 2009; Jiao et al., 2011), and comparisons of diversification rates suggested that polyploidy may have led to a dramatic increase in species richness in several angiosperm lineages (Soltis et al., 2009). Tank et al. (2015) demonstrated that increased diversification rates usually follow paleopolyploidization events but are delayed for many millions of years, which was explained by the proposed WGD Radiation Lag-Time Model considering cyclic rounds of WGDs followed by a phase of diploidization (Schranz et al., 2012). Landis et al. (2018) suggested that younger WGDs are more likely to be followed by a diversification upshift than older WGDs. In contrast, data on recent polyploids showed little evidence of elevated diversification following polyploidy (Estep et al., 2014; Kellogg, 2016), and neopolyploid lineages actually exhibited significantly reduced rates of diversification compared with their diploid congeners (Mayrose et al., 2011). The ‘rate hypothesis’ and ‘time hypothesis’ are the two main hypotheses in explaining patterns of species richness (Wiens, 2011; Marin et al., 2018; Yan et al., 2018). The ‘rate hypothesis’ says that faster net diversification rates (speciation rate minus extinction rate) drive higher diversity in some clades, which are affected by ecological and biological factors that increase speciation, reduce extinction or both (Marin et al., 2018; Yan et al., 2018). Alternatively, under the ‘time hypothesis’, clades with higher species richness simply have had more time to accumulate species through speciation (Scholl and Wiens, 2016).

The Brassicaceae are among the 20 most species-rich families (rank 15) of angiosperms, accounting for 46 % of all vascular plants, and represent the most diverse family of Brassicales (Christenhusz and Byng, 2016). The Brassicaceae comprise 52 tribes, 351 genera and 3977 species according to the newest species checklist (http://brassibase.cos.uni-heidelberg.de;Koch et al., 2018), and are most abundant in the temperate regions of the Northern Hemisphere, especially the Irano-Turanian and Mediterranean regions and western North America (Salariato et al., 2018). There is no generally accepted taxonomic grouping above tribal level, but several major and presumably monophyletic evolutionary lineages (i.e. Aethionemeae; Lineages I, II and III) have been defined earlier (Beilstein et al., 2006; Franzke et al., 2011) and have been confirmed and slightly modified during the following years (Huang et al., 2016; Nikolov et al., 2019) (Fig. 1).

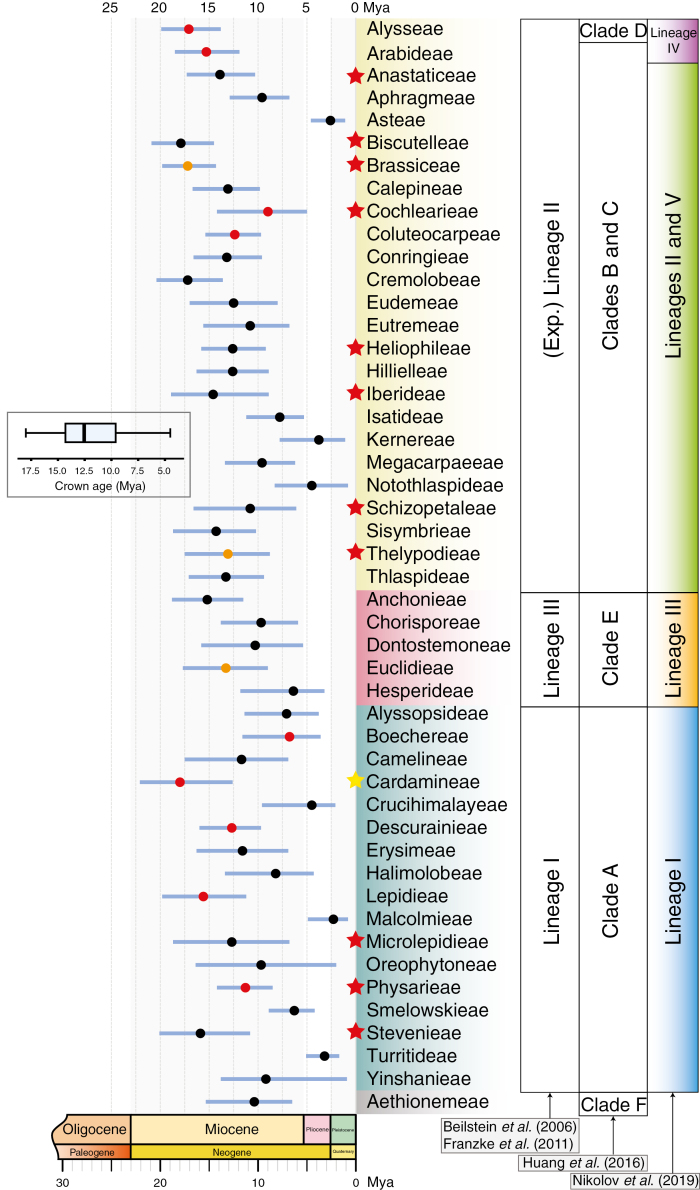

Fig. 1.

Illustration of crown group ages of 48 tribes in the Brassicaceae family (numbers given in millions of years). Crown group ages are compiled from each of the 48 tribal-wise BEAST analyses based on ITS data sets. The blue lines indicate 95 % HPD. Lineage and clade classifications follow Franzke et al. (2011), Huang et al. (2016) and Nikolov et al. (2019), respectively. Tribes showing at least a rate shift in ‘best shift configuration’ and in ‘95 % credible shift’ sets (excluding the first shift configuration) are denoted with red and orange dots, respectively (the position of the dots does not correspond to the timing of the shifts). Red stars indicate tribes for which mesopolyploidization events have been documented. In Cardamineae (yellow star), WGD was found in Leavenworthia (Mandáková et al., 2017b, and reference therein) only. The box plot diagram summarizes the mean crown group age over the entire data set.

The evolutionary history of Brassicaceae is characterized by a preceding WGD (paleopolyploidization) called At-α WGD (Schranz et al., 2012). Subsequently, within Brassicaceae, several tribe-specific post-At-α mesopolyploidy events have been identified, and a combined analysis of cytogenomic and transcriptomic data found that 11 out of 52 Brassicaceae tribes (plus one mesopolyploid WGD within tribe Cardamineae) had independent mesopolyploidizations followed by different degrees of diploidization (Mandáková et al., 2017b). This high number is contrasted by 106 confirmed WGDs found within the entire angiosperms (Landis et al., 2018). Recurrent polyploidization has played an essential role in the evolutionary history of Brassicaceae, and nearly half (approx. 43.3 %) of Brassicaceae taxa are neopolyploids (Hohmann et al., 2015), which also falls into the upper limits of angiosperm ploidy level variation. However, in Brassicaceae, no conclusive evidence of a causal link between mesopolyploidy and diversification has been demonstrated yet, since mesopolyploid WGDs pre-date not only some species-rich groups, but also small tribes and genera (Mandáková et al., 2017b). Given the idea that paleo- and mesopolyploidization are recognized as important driving forces of past genome evolution in angiosperms and considering neopolyploids as a potential source of future lineage diversification (Hohmann et al., 2015), Brassicaceae might represent an excellent model system to study diversification driven by polyploidization. Mean net diversification rates for angiosperms (approx. 0.15 species per million years) and rosids (approx. 0.19 species per million years) have been calculated in a highly dynamic evolutionary context of 334–530 rate shifts and 106 confirmed WGDs (Landis et al., 2018). Among Brassicaceae clades, however, diversification estimates are largely missing. One study focused on the species-rich tribe Arabideae with >400 species and showed a high rate (net diversification rate = 0.381) (Karl and Koch, 2013). With limited taxon sampling and in accordance with Couvreur et al. (2010), Tank et al. (2015) estimated a net diversification rate for Brassicaceae as a whole of 0.202, which also exceeds mean values for Rosids and angiosperms.

Past diversification processes are often discussed within an environmental context (Davies et al., 2004; Parmesan and Hanley, 2015), and it is a crucial aspect for our understanding of past evolutionary processes to unravel the effect of changing environmental parameters on adaptation and diversification. On a family and tribal level, there is little environmental information studied in Brassicaceae that can explain its past evolutionary dynamics. All deep major splits giving rise to main evolutionary lineages were placed not earlier than the onset of the Oligocene at about 32 Mya (e.g. Huang et al., 2016), indicating a correlation of early diversification with cooling global climate. Long before phylogenetic reconstructions contributed to our understanding of Brassicaceae evolution, it was hypothesized that Brassicaceae originated in the Irano-Turanian region (Hedge, 1976). This region is extremely diverse ecologically, altitudinally and geologically, and most of the species diversity is found in this region (Koch and Kiefer, 2006). This might also fit the idea that diversification was promoted by decreasing global temperatures and increasing drought during the Miocene (e.g. Karl and Koch, 2013).

Here, we used the model plant family Brassicaceae to study the disparities of species richness across the entire family, compiling DNA sequence data from nearly 50 % of all species and elaborating on a comprehensive temporal framework. For most of the tribes there are phylogenetic–systematic–taxonomic contributions available, often comparing DNA data sets and respective phylogenetic trees from different genomes and critically discussing systematics and taxonomy. A comprehensive list of these studies is given in Supplementary Data Table S1. This allows us to rely on critically discussed phylogenies on a tribal level and take advantage of the most often used marker in those studies, the internal transcribed spacer of nuclear encoded ribosomal DNA (named ITS hereafter).

With our study, (1) we attempt to present accurate time estimates for all tribal crown group splits. Entire plastid genomes were sequenced and analysed in the context of the Rosidae clade to calculate a set of respective node ages used to calibrate and align analyses from individual tribes. (2) Phylogenetic analyses based on ITS data for all tribes provide the information on modes of diversification in a temporal context. (3) Finally, we correlate various data sets (species richness, genome size and its variation, diversification rates, WGDs and crown group ages) to test the association of WGDs and diversification, eventually explaining the disparities of species richness across the Brassicaceae family and elaborating on the idea that WGDs may explain subsequent diversification.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The general experimental strategy of the project is outlined here in summary and is explained in more detail in the following sections. The largest available data set of Brassicaceae phylogenetic diversity is based on DNA sequence information of the ITS. Currently, those data sets comprise >2000 species and results have been published most often with critically evaluated phylogenetic systematic–taxonomic contributions (Supplementary Data Table S4). However, ITS sequence data in Brassicaceae cannot be aligned unambiguously on the entire family level (for details, refer to Bailey et al., 2006; Warwick et al., 2010) and, therefore, studies are most often focused on the level of tribes or groups of related genera. Another crucial consequence is that ITS sequence data cannot be used to calculate a family-wide phylogeny with reliable support for relationships among tribes. It has been shown that family-wide analyses are able to recognize main evolutionary Lineages I, II and III (Bailey et al., 2006; Warwick et al., 2010), but with little bootstrap support (BS) among tribes within these linages. Consequently, herein we rely on newly generated ITS sequence alignments on the tribal level. Selection of multiple outgroups for all of those tribal alignments aimed to maximize the number of shared outgroups among them. Outgroup taxa selection and respective temporal splits (important for subsequent analyses of diversification and divergence time estimates) have been selected from a backbone temporal framework phylogeny based on the entire plastid genome (see also Hohmann et al., 2015) and selecting outgroup taxa from Lineages I, II and III and basal Aethionema consistently found in recent phylogenetic studies (e.g. Huang et al., 2016; Nikolov et al., 2019). Our two-step approach was developed to estimate divergence times for every tribe in Brassicaceae, thus bypassing the problems associated with unresolved intertribal relationships analysing ITS data on a family level. First, a time-calibrated tree of the Rosidae clade was reconstructed based on a plastome data set, including representative taxa from all major lineages of Brassicaceae (Hohmann et al., 2015; Huang et al., 2016; Nikolov et al., 2019). This step allowed us to obtain an accurate timeline for Brassicaceae evolution in a fossil-calibrated chronogram, where reliable fossil calibrations outside of Brassicaceae can be used. The most recently presented backbone phylogeny based on data from the nuclear genome did not provide divergence time estimates that can be considered herein (Nikolov et al., 2019), and earlier studies (e.g. Huang et al., 2016) did not resolve the phylogeny sufficiently.

Secondly, to obtain crown age estimates for every tribe in Brassicaceae, the divergence times of Brassicaceae lineage splits from the plastome-based chronogram were subsequently used as secondary calibration points in the molecular dating analyses for each of 48 tribe-wide ITS data sets comprising >2000 taxa in total. The use of secondary calibration points provided useful temporal anchor points to guide the intertribal comparisons that are otherwise impossible to conduct.

Taxon sampling and data set composition

A total of 45 Brassicaceae plastid genomes were used in this study, covering all major evolutionary lineages (Lineage I, expanded II and III, and ancestral tribe Aethionemeae; see Fig. 1; according to Franzke et al., 2011; Huang et al., 2016: Nikolov et al., 2019) of Brassicaceae (Supplementary Data Table S1). Forty-eight taxa from all main lineages of the Rosidae were included as outgroups to enable consideration of reliable calibration points outside of Brassicaceae for molecular dating (Hohmann et al., 2015).

According to a recently proposed comprehensive species checklist (Koch et al., 2018), the family Brassicaceae comprises 52 tribes, 351 genera and 3977 species. ITS sequence alignments were compiled from BrassiBase (http://brassibase.cos.uni-heidelberg.de;Koch et al., 2012; Kiefer et al., 2014); further data were retrieved from recent publications and GenBank according to the above-mentioned species checklist focusing on accepted names of taxa (Supplementary Data Table S2). This study analysed 2101 taxa (Supplementary Data Table S2) from a currently recognized total of 4446 taxa comprising the family Brassicaceae. In total, the data sets represented approx. 47.3 % of known Brassicaceae diversity at the level of species and subspecies.

Genomic DNA extraction and plastome de novo assembly

Genomic DNA was extracted from either silica-dried or fresh material using the Invisorb Spin Plant Mini Kit (STRATEC Molecular). Total genomic DNA libraries were prepared with a library insert size of 200–400 bp and sequenced at the CellNetworks Deep Sequencing Core Facility (Heidelberg) using the NEBNext Ultra DNA Library Prep Kit for Illumina sequencing (New England Biolabs Inc., Ipswich, MA, USA) with the NEBNext Multiplex Oligos for Illumina sequencing. Samples were multiplexed per lane and sequenced in 100 bp paired-end mode on an Illumina HiSeq 2000 sequencer.

Complete plastid genomes were assembled in CLC Genomics Workbench v6.0.4 (CLC Bio). Adaptor trimming was conducted using a minimum per base quality of 0.001 (corresponding to a phred score of 30) and minimum sequence length of 50 bp. Trimmed paired reads were assembled using the legacy version of the CLC de novo assembly algorithm (length fraction 0.9, similarity 0.9 and appropriate distance settings). Contigs were identified using BLASTn (with default parameters), and details of the procedure and parameters were described by Hohmann et al. (2015). The newly assembled and annotated plastid genomes of Hesperis matronalis and Clausia aprica were submitted to GenBank under accession numbers LN877374 and LN877375, respectively.

Time-calibrated backbone of Brassicaceae evolutionary history based on complete plastome sequences

In Brassicaceae, past divergence time estimates have been discussed controversially (summarized in Franzke et al., 2016). Since then and due to using more sophisticated approaches, divergence time estimates from both nuclear and plastid genomes converged significantly (e.g. Hohmann et al., 2015; Huang et al., 2016, and references therein). Past incongruencies were mostly due to: (1) a general lack of reliable fossils within the Brassicaceae and reliance on synonymous substitution rates from single genes (Koch et al., 2000; Kagale et al., 2014); (2) differences in taxon sampling, selected genes and genomes (plastid, mitochondrial and nuclear); or (3) usage of different software for molecular dating, model choices and fossil calibrations, which resulted in earlier studies with substantially different estimates for the crown age of Brassicaceae and up to 3.62-fold variation among studies [15 Mya from Franzke et al. (2009) vs. 54.3 Mya from Beilstein et al. (2010)]. Actually the crown age estimates for Brassicaceae have converged among studies and genomes or genes sequenced towards 32.4–37.1 Mya (Edger et al., 2015; Hohmann et al., 2015; Huang et al., 2016).

For all plastid genomes used herein, the coding gene space was obtained (Hohmann et al., 2015); DNA sequence information was retrieved from 73 genes and aligned using MAFFT v7.017 (Katoh and Standley, 2013) as implemented in Geneious v7.1.7 (Biomatters). The FFT-NS-ix1000 algorithm was used with default option for all other parameters. Start and stop codons of protein-coding genes were excluded due to high potential for homoplasy. Indels from sequence alignments were trimmed using Gblocks v0.91b (Castresana, 2000) under the following conditions: the minimum length of a block was set to 2 bp, and gap positions were all removed; otherwise, the default settings were accepted. Afterward, the trimmed sequences of all 73 plastid genes were concatenated in Geneious v7.1.7. The alignment of plastomes is shown in Supplementary Data File S1.

To account for rate heterogeneity among genes, PartitionFinder V1.1.1 (Lanfear et al., 2012) was used to determine the best-fit partitioning schemes and substitution models. Pre-defined data blocks for the partitioning schemes search were designated according to genes. Branch lengths were allowed to be unlinked, and best-fit partitioning schemes and sub-set models were selected using the greedy search with Beast models. Model selection and partitioning scheme comparison was performed using the corrected Akaike information criterion (AICc) (Supplementary Data Table S3).

Phylogenetic trees were reconstructed with maximum likelihood (ML) using RAxML v8.1.16 (Stamatakis, 2014) based on the nine partitioned sequence alignments as suggested in PartitionFinder under the AICc. A rapid bootstrap analysis and search for the best-scoring ML tree was conducted with 1000 bootstrap replicates. The partitioned data set with per-partition estimation of branch lengths was used with GTR + I + G as the substitution model. Vitis vinifera was selected to root the tree since the order Vitales was found in a sister position to the remaining Rosidae clade (Magallon et al., 2015).

By applying a χ2 test to lnL values of distance trees with Enforced Clock and Without Clock, likelihood ratio tests in the PAUP* v4.0b10 (Swofford, 2003) suggested that a strict molecular clock hypothesis was not statistically supported (P < 0.001) in the plastome data bset (45 Brassicaceae taxa + 48 outgroups). Therefore, an uncorrelated log-normal relaxed clock was applied to estimate the divergence times as implemented in BEAST v1.7.5 (Drummond et al., 2012).

The partitioning schemes and substitution models were set under the previous results from PartitionFinder v1.1.1 (Supplementary Data Table S3). Vitis vinifera was set as outgroup. The plastome ML tree was used as a starting tree after it was made ultrametric with node ages fitted constraints in R package APE (Paradis et al., 2004). The tree model was set to a birth–death speciation process with incomplete sampling (Stadler, 2009). Appropriate calibrations are fundamental for molecular dating (Ho and Phillips, 2009), but few reliable fossils are known for the crown group of the Brassicaceae. The available fossil from the Brassicaceae (i.e. Thlaspi primaevum) (Beilstein et al., 2010) was not included herein, since this fossil evidence is still under debate (Franzke et al., 2016). Magallón et al. (2015) used this fossil to set a minimum age for the Brassicaceae crown group of approx. 25 Mya. However, all recent time-calibrated analyses of Brassicaceae (Hohmann et al., 2015; Cardinal-McTeague et al., 2016; Huang et al., 2016; Guo et al., 2017; Mandáková et al., 2017a) demonstrated higher crown ages than that for the radiation of the family. Consequently, this internal Brassicaceae fossil had to be excluded. Four fossil calibrations were chosen to calibrate divergence times in this study [in accordance with an angiosperm-wide analysis presented by Magallón et al. (2015)]: the minimum age for the Prunus/Malus split was set to 48.4 Mya and the Castanea/Cucumis split to 84 Mya, the minimum age for Mangifera/Citrus was set to 65 Mya and for Oenothera/Eucalyptus to 88.2 Mya.

A uniform distribution (uniformPrior) was used for all four fossil calibrations with a maximum age of 125 million years; the tree root height was constrained with a minimum age of 92 million years and a maximum of 125 million years (a uniform distribution) (Hohmann et al., 2015).

Two independent Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) runs were conducted with 500 million generations each and sampling every 50 000 generations. Convergence and effective sample size (>200) of parameters were evaluated in Tracer 1.7 (Rambaut et al., 2018). LogCombiner v1.7.5 (Drummond et al., 2012) was used to combine trees from these two runs and remove 10 % of generations as burn in. The resulting 18 002 trees were combined to a maximum clade credibility tree in TreeAnnotator v1.7.5 (Drummond et al., 2012) with the posterior probability limit set to 0.5 and mean node heights summarized.

Tribe-wide dated phylogenies based on 48 ITS sequence data sets in Brassicaceae

For each tribe, two taxa from two immediate lineages were chosen consistently as outgroups (only arabidopsis was chosen as outgroup for the basal Aethionemeae) in tribe-wide ITS trees, rather than including family-wide sequences in a single alignment. By doing so, we could avoid using alignments which are overloaded with gaps of varying lengths and thereby hindering reliable downstream analyses. Subsequently, divergence times of major Brassicaceae lineage splits from the dated plastome phylogeny were employed as secondary calibration points to calibrate nodes in each ITS tree individually. The detailed and consistent outgroup settings for tribes in each lineage were as follows: (1) Lineage I, Aethionema grandiflorum + Brassica napus; (2) (expanded) Lineage II, Arabidopsis thaliana + Clausia aprica; (3) Lineage III, Arabidopsis thaliana + Brassica napus; and (4) basal lineage, Arabidopsis thaliana.

Each tribe was initially aligned using webPRANK (https://www.ebi.ac.uk/goldman-srv/webprank/), which in our experience performs better in optimizing positioning of gaps compared with MAFFT (Löytynoja and Goldman, 2008) using default settings and with subsequent manual adjustments in PhyDE v0.9971 (http://www.phyde.de). The best-fit models for the resulting 48 tribe-wide ITS data sets (the remaining four tribes were left unaligned because of the presence of only one ingroup taxon/sequence) were identified with jModeltest 2.1.10 (Darriba et al., 2012) based on the AICc.

These ITS phylogenies represent the most comprehensive estimates of tribe-wide relationships using a single marker. In the present study, our interests were to estimate divergence times for every tribe, and not to re-assess respective phylogenetic hypotheses. However, tree topologies of individual tribes were not significantly different from previous phylogenetic–systematic–taxonomic studies (Supplementary Data Table S4), with most of them being based on a commonly used combination of nuclear-encoded ITS and plastid trnL–F markers as well as a few additional loci from all three plant genomes.

BEAST v1.7.5 was used to estimate divergence time based on ITS data sets, incorporating an uncorrelated relaxed log-normal clock model. For the tree priors, the birth–death speciation process was selected, since the Yule model is likely to be inappropriate for most data sets because it excludes the possibility of extinction (Ho and Duchene, 2014). Ages of three nodes representing four major lineage splits were obtained from the plastome chronogram as temporal anchor points for the molecular dating analyses of all 48 tribes (Table 1), in which the normal distribution priors were used.

Table 1.

Secondary calibrations obtained from the plastome chronogram and further used for tribe-wide molecular dating as a normal distribution prior (in Mya)

| Node | Mean | s.d. | 95 % CI |

|---|---|---|---|

| A | 29.94 | 1.96 | 26.72–33.16 |

| B | 21.26 | 1.02 | 19.58–22.94 |

| C | 20.57 | 1.00 | 18.93–22.21 |

See Supplementary Data Fig. 2 for the detailed locations of these nodes.

Two independent MCMC runs for each data set were conducted with 50 million generations each and sampling every 5000 generations (for approx. 50 sequences, 10 million generations with sampling every 1000 steps; for approx. 100 sequences, 50 million generations with sampling every 5000 steps; and for approx. 300 sequences, 100 million generations with sampling every 10 000 steps). LogCombiner v1.7.5 (Drummond et al., 2012) was used to combine trees from two runs, and the first 25 % generations were discarded as burn in. For each of 48 tribes, the resulting 15 002 trees were combined to a maximum clade credibility tree in TreeAnnotator v1.7.5 (Drummond et al., 2012) with the posterior probability limit set to 0.5 and mean node heights summarized. All ITS alignments and corresponding BEAST output tree files (Supplementary Data File S2) have been deposited in the DRYAD repository under doi:10.5061/dryad.kr4rf80.

Diversification analyses

Bayesian Analysis of Macroevolutionary Mixtures (BAMM) (Rabosky, 2014; Rabosky et al., 2017) was employed for ITS data set analyses: (1) to estimate rates of speciation (λ), extinction (μ) and net diversification (γ) for all Brassicaceae tribes; (2) to conduct rate-through-time analysis of these rates; and (3) to identify and visualize shifts in speciation rates across these tribe-wide trees. BAMM implements reversible jump MCMC, and allows for both time-dependent speciation rates and discrete shifts in the rate and pattern of diversification.

After pruning outgroups, each of 48 time-calibrated tribal trees was used for BAMM analyses [six out of the 48 tribes had to be finally excluded because of the small number of taxa (≤3 sequences)]. To account for non-random and incomplete taxon sampling, we determined the percentage of species sampling per genus when a monophyletic genus was recovered; otherwise, the total number of taxa for a given tribe was assigned (Supplementary Data Table S2). Species numbers were obtained from the most recent and comprehensive species checklist (Koch et al., 2018).

For each tribe, BAMM priors were generated from R package BAMMtools (Rabosky et al., 2014) with the function setBAMMpriors by providing the pruned BEAST tree and total taxa number. Due to a small number of tips (<500 tips) in the tribe-wide ITS trees, we assigned the prior on the expected number of shifts to 1.0. MCMC chains were run for 20 million generations with default settings. Convergence of the runs was assessed by the log-likelihood trace and effective sample sizes (ESSs; >200) of the log-likelihood using R package CODA (Plummer et al., 2006) after discarding 10 % of samples as burn in. The 95 % credible rate shift configuration was estimated using Bayes factors. The 95 % credible set of shift configuration, the best shift configuration [i.e. the rate shift configuration with the highest maximum a posteriori (MAP) probability], macroevolutionary cohort analyses and rate-through-time plots were summarized and plotted using the package BAMMtools in R.

It has to be noted that the herein estimated rates of diversification with BAMM are potentially affected by our approach using tribal alignments rather than a family-wide phylogeny (Rabosky, 2019). However, reconstruction of a family-wide phylogeny is not possible, as outlined before, with the general experimental strategy, and we have to rely on a compensating effect analysing >50 % of all species of the entire family. It is also important to notice that alternative methods such as method-of-moments (MS; Magallón and Sanderson, 2001) are superior if stem group ages are available (Meyer and Wiens, 2018), which is not the case in this study. Unfortunately, the only available and nearly complete backbone phylogeny based on genomic information (Nikolov et al., 2019) did not provide a fully reliably resolved phylogeny of the Brassicaceae nor are there any time calibrations performed. Therefore, it cannot be used as backbone phylogeny for any supermatrix approach generating a family-wide and time-calibrated ultrametric tree. However, with our approach, we can at least provide crown group ages of tribes that allow comparisons across tribes. Therefore, we prefer a method such as BAMM estimating parameters from the given data (Meyer et al., 2018; Rabosky, 2019). There are few diversification rates calculated for Brassicaceae or subclades, and in the Results section previous studies are briefly compared with herein presented rate estimates to provide some evidence for comparability across different studies.

Statistical analysis and coherence among data sets

Genome size data of Brassicaceae were retrieved from Hohmann et al. (2015). This data set comprises information from 331 species out of the total of 3977. Information from mesopolyploid WGD in the various tribes (11 in total) was also used as a test variable. The same contribution also provided an overview on chromosome numbers and ploidy levels available for 1653 taxa (Hohmann et al., 2015). The curated data can be found at BrassiBase (https://brassibase.cos.uni-heidelberg.de/; Koch et al., 2012, 2018; Kiefer et al., 2014).

We tested the hypothesis that net diversification rates explained major variation in species richness among Brassicaceae tribes, and analysed the impact of mesopolyploid WGDs on rate shifts and diversification. Genome size data and their variation were used as a measure of genome dynamics.

SPSS v19.0 (IBM Corp. Released 2017. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 25.0) was used for statistical analyses. Statistical significance was considered if P < 0.05. Normally distributed and independent data were analysed by unpaired two-tailed Student’s t-test and non-parametric independent data by the Mann–Whitney U-test if only two groups were compared. Multiple groups (not normally distributed data) were analysed by the Kruskal–Wallis test. Linear regression analyses and correlation analyses (Spearman’s ρ and Kendall’s τ; **P < 0.01, *P < 0.05, two-tailed) were also performed with SPSS. Variables were graphically investigated for deviations from normality using QQ-plots and also tested for normality by Shapiro–Wilk test.

RESULTS

Plastome-based evolutionary time scale of Brassicaceae evolution

The majority of supra-genus relationships across Brassicaceae were well supported (BS >90), except for the position of Lepidium (tribe Lepidieae; BS = 62) (Supplementary Data Fig. S1). The placement of Lepidieae was unstable among analyses of plastomes. Lepidium was recovered in a sister relationship with Cardamineae species (Hohmann et al., 2015; Mandáková et al., 2017a), whereas an alternative topology was retrieved in the present study (Supplementary Data Fig. S1) as well as in Guo et al. (2017). Interestingly, the same topology has also been demonstrated, with the most recent backbone phylogeny derived from the nuclear genome (Nikolov et al., 2019). Tribe Aethionemeae diverged early from the rest of the Brassicaceae family (core Brassicaceae) (Supplementary Data Figs S1 and S2), forming a basal clade as confirmed in various studies using different markers or genome-scale data sets (Franzke et al., 2011; Hohmann et al., 2015; Huang et al., 2016; Guo et al., 2017; Mandáková et al., 2017a). The core Brassicaceae taxa were divided into three well-resolved clades as defined earlier by Franzke et al. (2011): Lineage I, Lineage II + expanded lineage II (hereafter referred to as Lineage II) and Lineage III (Fig. 1; Supplementary Data Figs S1 and S2). It has to be noted here that Lineage II was split by Nikolov et al. (2019) into two related clades (Lineage II and Lineage V), leaving four tribes from the original Lineage II unassigned with an intermediate position. Therefore, this grouping is not in contradiction to previous concepts. The most important incongruence among studies is the recognition of a separate Lineage IV (Nikolov et al., 2019) with tribes, which have been separated from Lineage II. This affects tribes Arabideae and Alysseae, and we followed this grouping concept accordingly. Inclusion of tribe Stevenieae in Lineage IV was erroneously performed by Nikolov et al. (2019), because Pseudoturritis turrita is considered as a member of tribe Arabideae (Koch et al., 2018), and tribe Stevenieae remains with Lineage I. Finally, the phylogenetic position of tribe Biscutelleae has not been resolved (Nikolov et al., 2019) and, therefore, we kept the tribe in Lineage II as defined earlier (Franzke et al., 2011; Huang et al., 2016).

The Bayesian relaxed-clock method was used to estimate the time frame of Brassicaceae evolution based on whole-plastome sequences. Forty-eight plastid genomes of outgroups were included, enabling us to use four non-Brassicales fossil calibrations. According to the BEAST chronogram using 73 plastid genes, tribe Aethionemeae and core Brassicaceae split at 29.94 Mya with the 95 % highest posterior density (HPD) of 26.78–33.16 Mya during the Oligocene (Supplementary Data Fig. S2; Table 2). The core Brassicaceae were estimated to have diverged at 21.26 Mya (95 % HPD = 19.6–22.93) during the Miocene, and subsequent but almost immediate separation of Lineage II and Lineage III was dated to 20.57 Mya (95 % HPD = 18.93–22.17). Radiation of all these major lineages in core Brassicaceae occurred over a short interval of time in the early Miocene (Supplementary Data Fig. S2).

Table 2.

Comparison of divergence time estimates (Mya) for Brassicaceae from past studies

| Studies | Crown Brassicaceae | Crown ‘core Brassicaceae’* | Method | Data set | Calibration |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Koch et al. (2000) | NA | 23.1–25.9 | Synonymous substitution rate | Adh and Chs | Synonymous substitution rate |

| Franzke et al. (2009) | 1.0–15.0–35.0 | 1.0–11.0–28.0 | BEAST | nad4 | One secondary calibration |

| Beilstein et al. (2010) | 45.2–54.3–64.2 | 39.4–46.9–54.3 | BEAST | ndhF and PHYA | Four fossils |

| Couvreur et al. (2010) | 24.2–37.6–49.4 | 20.9–32.3–42.8 | BEAST | Eight genes from nuclei, chloroplasts and mitochindria | One fossil |

| Kagale et al. (2014) | NA | 26.6 | Synonymous substitution rate | 213 nuclear orthologues | Synonymous substitution rate |

| Edger et al. (2015) | 16.8–31.8–45.9 | NA | BEAST | 1155 single-copy nuclear genes | Two fossils |

| Hohmann et al. (2015) | 27.1–32.4–38.6 | 19.9–23.4–27.3 | BEAST | Plastomes | Four fossils |

| Huang et al. (2016) | 36.3–37.1–37.8 | 29.1–29.7–30.3 | r8s | 113 low-copy nuclear orthologues | 18 fossils† |

| Cardinal-McTeague et al. (2016) | 31.4–37.7–44.1 | NA | BEAST | cpDNA (ndhF, matK, rbcL) and mtDNA (matR, rps3) | Three fossils† |

| Mohammadin et al. (2017) | 37.5–48.0–58.94 | 35.4 | BEAST | Plastomes | One secondary calibration |

| Guo et al. (2017) | 29.0–34.9–41.8 | 21.3–25.1–29.8 | MCMCTree | Plastomes | 14 fossils‡ |

| Mandáková et al. (2017b) | 29.4–40.1–54.7 | 30.6 | BEAST | Plastomes | Four fossils |

| This study | 26.8–29.9–33.2 | 19.6–21.3–22.9 | BEAST | Plastomes | Four fossils |

*Brassicaceae excluding basal tribe Aethionemeae.

†Dating results using Thlaspi primaevum are not shown.

‡Only results that exclude Brassicales fossils are shown.

BEAST-derived chronograms based on 48 tribe-wide ITS data sets

Molecular-clock analyses on 48 of all currently recognized 52 tribes were conducted based on respective tribal ITS data sets. The remaining four tribes were not included because of the presence of only one (or two in the case of Buniadeae) ingroup taxon, and are as follows: Bivonaeeae (Bivonaea lutea), Scoliaxoneae (Scoliaxon mexicanus), Shehbazieae (Shehbazia tibetica) and Buniadeae (Bunias erucago and Bunias orientalis). Ages of all major lineage splits in Brassicaceae obtained from this plastome BEAST analysis were used as the temporal anchor points to calibrate divergence times on 48 tribe-wide ITS data sets comprising >2000 taxa in total. Respective 95 % HPD intervals of tribal crown group ages are summarized in Fig. 1 and Supplementary Data Table S5. Comparing and combining all crown group ages revealed that the majority of tribes started diversification between 8.6 and 14.3 Mya (box plot in Fig. 1: lower quartile Q1 = 8.6, median quartile Q2 = 11.9, upper quartile Q3 = 14.3; Supplementary Data Table S5), lagging a little behind the Middle Miocene disruption (Middle Miocene extinction) roughly 14.5 Mya with a relatively steady period of global cooling and Miocene Climatic Temperature Optimum (approx. 17–15 Mya; Zachos et al., 2001, 2008).

Diversification speed of Brassicaceae

Across the 42 finally analysed tribal phylogenetic trees in Brassicaceae, BAMM analyses identified 12 tribes with significant shift(s) in their tempo of diversification. Specifically, nine out of these 12 tribes with rate shift(s) with the MAP probability shift configuration, which is the distinct shift configuration with the highest posterior probability, were identified. These tribes showed strong evidence for evolutionary rate heterogeneity (Fig. 2). Detailed information about diversification patterns of the 42 tribes is given with Supplementary Data File 3.

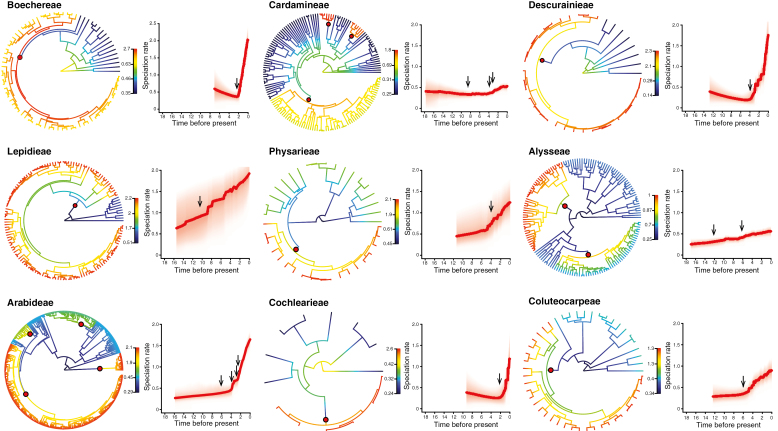

Fig. 2.

BAMM analyses on tribes in Brassicaceae. Nine tribes exhibiting rate shift(s) in the best shift configuration are shown. Red circles denote significant increases of speciation rates for respective tribes. Shift locations in the rate through time plots are indicated by arrows. Time scale numbers are given in Mya.

All of the nine tribes showed increases in net diversification rates through time, with the majority rising rapidly with several fluctuations (Fig. 2). These rate shifts did not centre around the few discrete climatic events introduced before (Middle Miocene extinction, Miocene Climatic Optimum) but occur randomly between roughly 12 and 2.5 Mya (Fig. 2).

Analyses of all tribe-wide ITS trees revealed significant disparities in net diversification rates across Brassicaceae tribes. The global mean speciation (λ), extinction (μ) and net diversification (γ) rates for the family Brassicaceae were calculated as 0.5493 (s.d. = 0.3088), 0.2947 (s.d. = 0.2249) and 0.2546 (s.d. = 0.2130) species per million years, respectively (Table 3). For speciation rate, the maximum and minimum values were found in tribe Lepidieae (1.6492 species per million years) and tribe Conringieae (0.1838 species per million years), respectively. Concerning the net diversification rate, however, the maximum and minimum values were shifted to tribe Boechereae (1.0177 species per million years) and tribe Hillielleae (–0.0319 species per million years), respectively.

Table 3.

Estimated speciation, extinction and diversification rates (with 95 % CI) for tribes in Brassicaceae based on BAMM analyses

| Lineage | Tribe | Speciation | Extinction | Net diversification | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | 95 % CI | Mean | 95 % CI | Mean | 95 % CI | |||||

| I | Alyssopsideae | 0.4435 | 0.1818 | 0.8532 | 0.3890 | 0.0310 | 1.0070 | 0.0545 | –0.8253 | 0.8223 |

| Boechereae | 1.2219 | 1.0035 | 1.4807 | 0.2042 | 0.0351 | 0.5026 | 1.0177 | 0.5008 | 1.4456 | |

| Camelineae | 0.5371 | 0.3063 | 0.9486 | 0.3079 | 0.0193 | 0.8645 | 0.2291 | –0.5582 | 0.9293 | |

| Cardamineae | 0.4324 | 0.3674 | 0.5178 | 0.1154 | 0.0404 | 0.2277 | 0.3170 | 0.1397 | 0.4774 | |

| Crucihimalayeae | 0.7850 | 0.3807 | 1.4075 | 0.5734 | 0.0460 | 1.4842 | 0.2116 | –1.1035 | 1.3615 | |

| Descurainieae | 0.6524 | 0.4529 | 0.9179 | 0.2990 | 0.0646 | 0.6462 | 0.3534 | –0.1933 | 0.8533 | |

| Erysimeae | 0.5095 | 0.4281 | 0.6227 | 0.0809 | 0.0048 | 0.2341 | 0.4285 | 0.1940 | 0.6180 | |

| Halimolobeae | 0.7683 | 0.4375 | 1.2697 | 0.4654 | 0.0333 | 1.1912 | 0.3029 | –0.7537 | 1.2364 | |

| Lepidieae | 1.6492 | 1.0710 | 2.2301 | 1.1816 | 0.3712 | 1.9002 | 0.4677 | –0.8292 | 1.8589 | |

| Microlepidieae | 0.3096 | 0.2087 | 0.4343 | 0.0822 | 0.0052 | 0.2254 | 0.2274 | –0.0167 | 0.4292 | |

| Physarieae | 1.0268 | 0.6390 | 1.6934 | 0.5757 | 0.0893 | 1.4357 | 0.4511 | –0.7967 | 1.6041 | |

| Smelowskieae | 0.6325 | 0.3772 | 1.0133 | 0.3256 | 0.0254 | 0.8590 | 0.3069 | –0.4818 | 0.9879 | |

| Stevenieae | 0.2301 | 0.1059 | 0.4438 | 0.1713 | 0.0119 | 0.4611 | 0.0587 | –0.3551 | 0.4319 | |

| Yinshanieae | 0.2743 | 0.0972 | 0.5552 | 0.2648 | 0.0188 | 0.6881 | 0.0096 | –0.5909 | 0.5364 | |

| Lineage I total | 0.6766 | s.d. = 0.3967 | 0.3597 | s.d. = 0.2870 | 0.3169 | s.d. = 0.2485 | ||||

| II | Anastaticeae | 0.3699 | 0.2453 | 0.5607 | 0.1213 | 0.0059 | 0.3936 | 0.2486 | –0.1484 | 0.5548 |

| Aphragmeae | 0.4669 | 0.1899 | 0.9121 | 0.4202 | 0.0452 | 1.0056 | 0.0468 | –0.8157 | 0.8669 | |

| Biscutelleae | 0.2990 | 0.1753 | 0.5040 | 0.1403 | 0.0089 | 0.3944 | 0.1587 | –0.2191 | 0.4951 | |

| Brassiceae | 0.4197 | 0.3687 | 0.4789 | 0.0370 | 0.0033 | 0.0950 | 0.3826 | 0.2736 | 0.4757 | |

| Calepineae | 0.1992 | 0.0726 | 0.4011 | 0.1712 | 0.0131 | 0.4511 | 0.0279 | –0.3785 | 0.3880 | |

| Cochlearieae | 0.4552 | 0.2632 | 0.7449 | 0.2606 | 0.0401 | 0.6507 | 0.1946 | –0.3875 | 0.7048 | |

| Coluteocarpeae | 0.6869 | 0.5129 | 0.9240 | 0.2337 | 0.0446 | 0.5499 | 0.4531 | –0.0370 | 0.8794 | |

| Conringieae | 0.1838 | 0.0707 | 0.3594 | 0.1370 | 0.0086 | 0.3774 | 0.0468 | –0.3068 | 0.3507 | |

| Cremolobeae | 0.4314 | 0.2326 | 0.7325 | 0.3251 | 0.0426 | 0.7239 | 0.1063 | –0.4913 | 0.6898 | |

| Eudemeae | 0.5636 | 0.2903 | 1.0302 | 0.4146 | 0.0301 | 1.0553 | 0.1490 | –0.7650 | 1.0001 | |

| Eutremeae | 0.4184 | 0.2574 | 0.6733 | 0.2142 | 0.0181 | 0.5597 | 0.2042 | –0.3023 | 0.6552 | |

| Heliophileae | 0.3415 | 0.2609 | 0.4517 | 0.0843 | 0.0057 | 0.2382 | 0.2572 | 0.0227 | 0.4460 | |

| Hillielleae | 0.4718 | 0.2120 | 0.8656 | 0.5038 | 0.1158 | 1.0387 | –0.0319 | –0.8267 | 0.7497 | |

| Iberideae | 0.2701 | 0.1024 | 0.5076 | 0.2408 | 0.0379 | 0.5509 | 0.0293 | –0.4485 | 0.4697 | |

| Isatideae | 0.9297 | 0.5566 | 1.5273 | 0.5280 | 0.0528 | 1.2768 | 0.4017 | –0.7202 | 1.4746 | |

| Megacarpaeeae | 0.4434 | 0.1671 | 0.8960 | 0.4753 | 0.0608 | 1.0934 | –0.0318 | –0.9264 | 0.8352 | |

| Schizopetaleae | 0.7217 | 0.3634 | 1.3121 | 0.6616 | 0.1507 | 1.4785 | 0.0601 | –1.1150 | 1.1613 | |

| Sisymbrieae | 0.3906 | 0.2399 | 0.6274 | 0.1955 | 0.0165 | 0.4996 | 0.1951 | –0.2597 | 0.6109 | |

| Thelypodieae | 0.3577 | 0.3034 | 0.4312 | 0.0530 | 0.0033 | 0.1497 | 0.3046 | 0.1537 | 0.4279 | |

| Thlaspideae | 0.2632 | 0.1536 | 0.4440 | 0.1229 | 0.0074 | 0.3568 | 0.1403 | –0.2033 | 0.4366 | |

| Lineage II total | 0.4342 | s.d. = 0.1814 | 0.2670 | s.d. = 0.1774 | 0.1672 | s.d. = 0.1419 | ||||

| III | Anchonieae | 0.3678 | 0.2402 | 0.5778 | 0.1783 | 0.0129 | 0.4592 | 0.1895 | –0.2189 | 0.5649 |

| Chorisporeae | 0.4434 | 0.3416 | 0.5691 | 0.0771 | 0.0044 | 0.2299 | 0.3663 | 0.1118 | 0.5647 | |

| Dontostemoneae | 0.3271 | 0.1745 | 0.5606 | 0.1956 | 0.0139 | 0.5202 | 0.1314 | –0.3457 | 0.5467 | |

| Euclidieae | 0.3449 | 0.2866 | 0.4120 | 0.0264 | 0.0013 | 0.0784 | 0.3185 | 0.2081 | 0.4106 | |

| Hesperideae | 0.8791 | 0.4647 | 1.5625 | 0.4760 | 0.0325 | 1.2747 | 0.4031 | –0.8100 | 1.5299 | |

| Lineage III total | 0.4725 | s.d. = 0.2316 | 0.1907 | s.d. = 0.1743 | 0.2818 | s.d. = 0.1166 | ||||

| IV | Alysseae | 0.5046 | 0.4205 | 0.6140 | 0.1041 | 0.0114 | 0.2405 | 0.4005 | 0.1800 | 0.6025 |

| Arabideae | 1.1809 | 1.0375 | 1.3621 | 0.3040 | 0.1227 | 0.5598 | 0.8769 | 0.4777 | 1.2394 | |

| Lineage IV total | 0.8428 | s.d. = 0.4782 | 0.2041 | s.d. = 0.1414 | 0.6387 | s.d. = 0.3369 | ||||

| Basal | Aethionemeae | 0.8681 | 0.4322 | 1.5881 | 0.6388 | 0.1083 | 1.4904 | 0.2294 | –1.0582 | 1.4798 |

| Total | 0.5493 | s.d. = 0.3088 | 0.2947 | s.d. = 0.2249 | 0.2546 | s.d. = 0.2130 |

Rates are species per million years.

Tribes with significant shifts in speciation rates are indicated in bold.

Six tribes, i.e. Malcolmieae, Oreophytoneae, Turritideae, Asteae, Kernereae and Notothlaspideae had no data because of the small number of taxa (≤3 sequences); another four tribes, i.e. Bivonaeeae, Scoliaxoneae, Buniadeae and Shehbazieae were not included because of the presence of only one (two in case of Buniadeae) ingroup taxons/sequences.

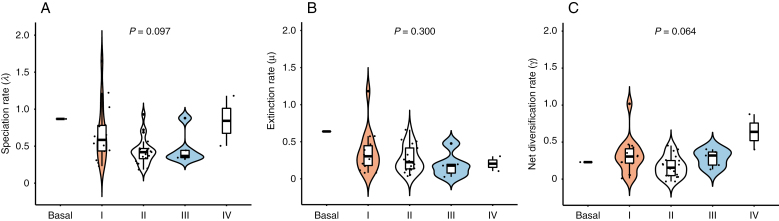

We found a striking amount of homogeneity (using Kruskal–Wallis test) in speciation (P = 0.097), extinction (P = 0.300) and net diversification (P = 0.064) rates among the major Brassicaceae lineages (Fig. 3), with no significant differences among them.

Fig. 3.

Comparisons of speciation rate (A), extinction rate (B) and net diversification rate (C) among lineages. No significant differences (P > 0.05, Kruskal–Wallis test) were observed among major Brassicaceae lineages (according to Nikolov et al., 2019; Fig. 1) on all three types of rates (A–C).

The herein presented diversification rates are largely in congruence with data from earlier studies. These studies are family wide (Couvreur et al., 2009) or even order wide (Capparales) (Cardinal-McTeague et al., 2016), but comprise a limited number of taxa and tribes. Cardinal-McTeague et al. (2016) used BAMM and detected one single significant rate shift in Brassicaceae, pre-dating the origin of tribes Brassiceae and Sisymbrieae. Our approach cannot detect this, but it showed that our analysis and increased sample size is sensitive enough to detect rate shifts within tribes accurately. Another family-wide study (Couvreur et al., 2010) also characterized a single shift at the early onset of core Brassicaceae lineages. The average net diversification rate for Brassicaceae was estimated as up to 0.223 (Couvreur et al., 2010) using Laserpackage v. 2.2 (Rabosky, 2006), which is close to the estimate presented herein (0.254; see Table 3). The BAMM analysis of tribes Cremolobeae, Eutremeae and Schizopetaleae (Salariato and Zuloaga, 2017) also revealed no rate shifts within and among those tribes, and net diversification rates were in a similar and comparable relative range to our estimates (0.16, 0.20 and 0.06 vs. 0.11, 0.20 and 0.06, respectively; Table 3).

Relationships between crown age, diversification rate and species richness

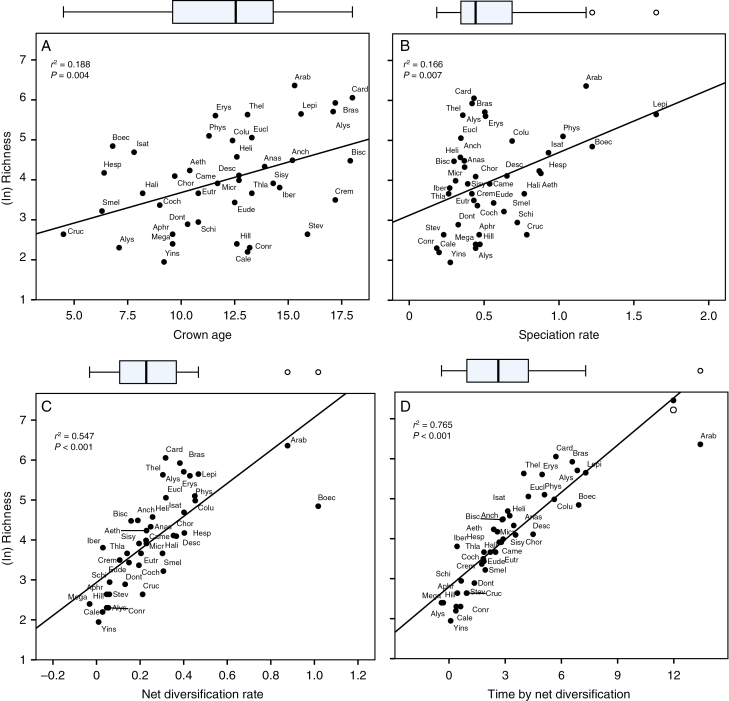

To test the two hypotheses of increased species richness (‘rate hypothesis’ and ‘time hypothesis’) and explain heterogeneity in species richness observed among Brassicaceae tribes, linear regression analyses between species richness (log-transformed) and clade age/diversification rate were used to quantify how much variation in species richness among tribes is explained by these factors. Across all tribes, we found only a weak positive relationship between crown ages and species richness of tribes (r2 = 0.188, P = 0.004; Spearman’s ρ = 0.408**, P = 0.007; Kendall’s τ = 0.294**, P = 0.006; Fig. 4A). Speciation rate and species richness were correlated, and a positive but weak correlation (r2 = 0.166, P = 0.007; Spearman’s ρ = 0.334*, P = 0.031; Kendall’s τ = 0.232*, P = 0.031; Fig. 4B) was observed. In contrast, a positive strong correlation was observed between the net diversification rate and species richness (r2 = 0.547, P < 0.001; Spearman’s ρ = 0.842**, P < 0.001; Kendall’s τ = 0.653**, P < 0.001; Fig. 4C). Thus, net diversification rates per se did explain major variation in species richness among Brassicaceae tribes.

Fig. 4.

Linear regression analyses of clade crown age, speciation rate, net diversification rate and time by net diversification rate vs. tribe species richness (log-transformed) in Brassicaceae.

The combined effect of clade age and the net diversification rate was examined in explaining species richness of Brassicaceae tribes using the ‘new index’ (i.e. clade age × diversification rate) (Yan et al., 2018) for each tribe. A strong positive relationship was observed between the combined effect of time (crown age) and net diversification rate vs. species richness (r2 = 0.765, P < 0.001; Spearman’s ρ = 0.942**, P < 0.001; Kendall’s τ = 0.801**, P < 0.001; Fig. 4D). This indicates that high species richness of Brassicaceae tribes is probably attributable to a combination of older crown age and faster net diversification rate.

Mesopolyploid WGDs did not a priori explain species diversification in Brassicaceae

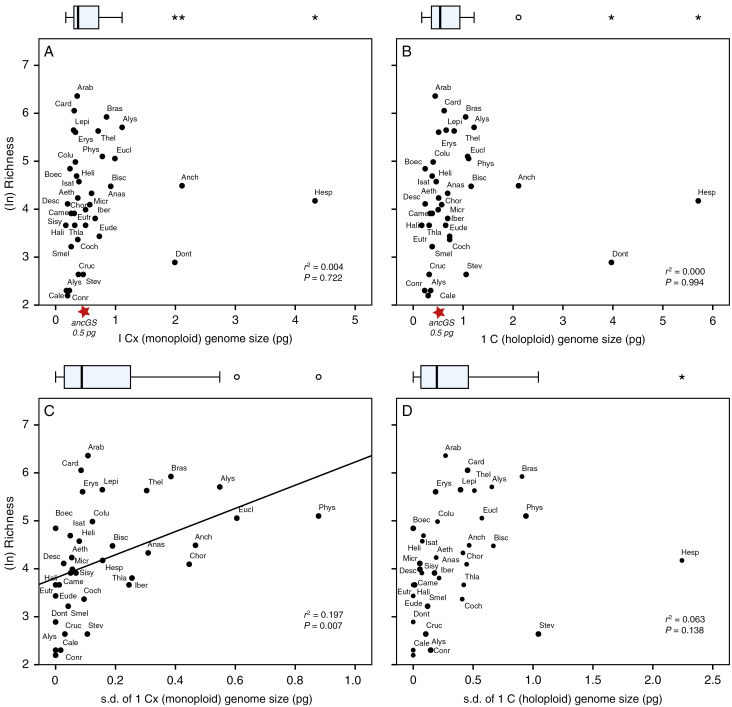

The relationships between the mean tribal genome size (GS) and species richness (log-transformed) were investigated. Neither monoploid GS nor holoploid GS (i.e. as a possible indicator of past polyploidization events) showed a positive relationship with species richness (P > 0.05; Fig. 5A, B). Conversely, all tribes tend to reduce their GS close to or even lower than the inferred ancestral genome size of Brassicaceae (approx. 0.5 pg; Lysak et al., 2009), as also revealed by Hohmann et al. (2015).

Fig. 5.

Relationships of genome size and species richness across Brassicaceae tribes. ancGS: hypothesized ancestral monoploid genome size of Brassicaceae (Lysak et al., 2009).

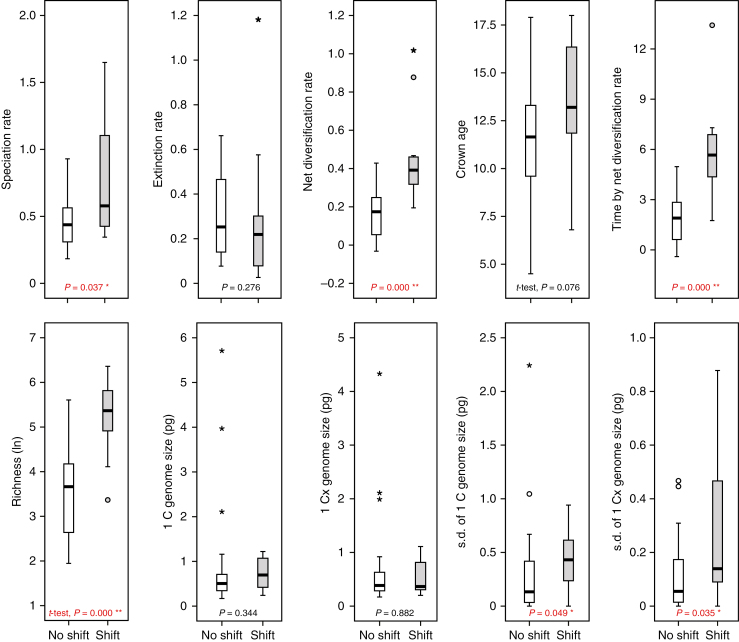

To test if genome size variation (as an indicator of dynamic genome evolution within tribes) contributed to species diversification in the various tribes, correlations between s.d. of GS and species richness were conducted (Fig. 5C, D). Here we found indeed that some variation of monoploid GS is correlated with higher species number (r2 = 0.197, P = 0.007; Spearman’s ρ =0.588**, P < 0.001; Kendall’s τ = 0.421**, P < 0.001). Across Brassicaceae, rate shifts seem to drive diversification. These shifts explained well the significant increases in speciation rates (P = 0.037, Mann–Whitney U-test) and net diversification rates (P < 0.001, Mann–Whitney U-test), and led to highly significant increases in species richness (P < 0.001, Student’s t-test) (Fig. 6). No significant difference was found in extinction rate. This is to be expected because under the birth–death process model all lineages have the same extinction probability, not being affected by the presence of speciation rate shifts elsewhere in the tree. Non-significant differences were found among genome sizes compared between tribes with and without a shift in diversification (P > 0.05; Fig. 6). Nonetheless, the GS variation showed significant differences between these two groups (P < 0.05; Fig. 6), indicating that increased dynamics of genome evolution do play a significant role in speciation and further differentiation.

Fig. 6.

Comparisons between tribes exhibiting no shift and shift of diversification rate, respectively. The symbols (*) and (**) indicate a significant group difference (P < 0.05 and P < 0.001, respectively) (two-tailed Mann–Whitney U-test, unless otherwise indicated).

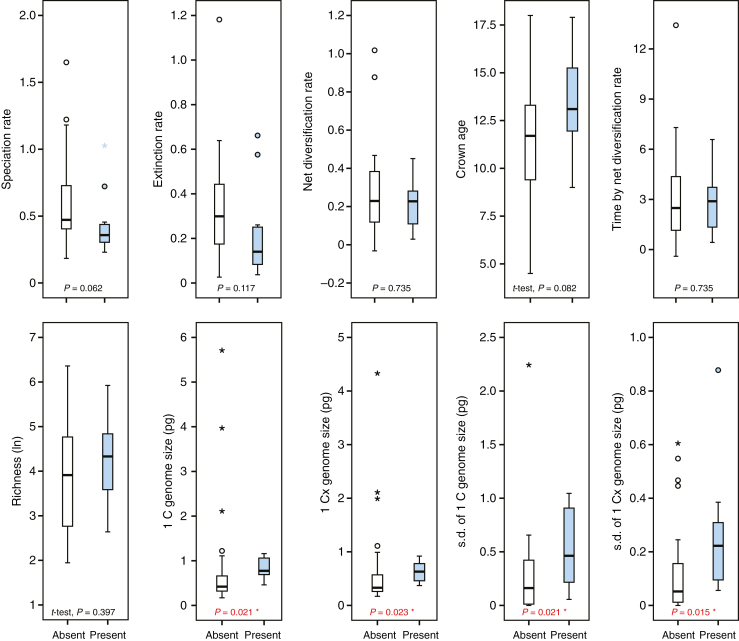

To test further if mesopolyploid WGDs promote species diversification, Brassicaceae tribes were divided into two groups (i.e. with vs. without mesopolyploid WGDs), comparing them at ten factors (Fig. 7). As expected, both GS and GS variation showed significant differences (P < 0.05, Mann–Whitney U-test), with WGD group having a larger GS and higher GS variation (an indicator of higher dynamics of genome evolution after polyploidization); however, non-significant differences in diversification rate (including speciation and extinction rate), crown age and species richness were found between these two groups (Fig. 7).

Fig. 7.

Comparisons between tribes with absent and present mesopolyploid WGDs (preceding tribal diversification). The symbols (*) indicate a significant group difference (P < 0.05) (two-tailed Mann–Whitney U-test, unless otherwise indicated).

With Supplementary Data Fig. S3, we provided a family-wide phylogeny extracting a bracket notation of tribal relationships from Nikolov et al. (2019). We excluded all tribes not analysed consistently across studies, we corrected for the erroneous position of tribe Stevenieae and included tribe Hillielleae using phylogenetic information from previous studies (see Supplementary Data Table S4). This tree has no branch lengths or are nodes calibrated, since both types of information were not accessible. Occurrence of rate shifts, WGDs and net diversification rates are presented, but it is not possible to further analyse the impact of phylogenetic distance on character and trait distribution across the entire family.

DISCUSSION

Oligocene divergence and subsequent Miocene–Pliocene radiation of Brassicaceae

Over the last decade, substantial progress has been made in reconstructing a phylogenetic framework and dating the crown age of Brassicaceae (Koch et al., 2000; Beilstein et al., 2010; Couvreur et al., 2010; Hohmann et al., 2015; Cardinal-McTeague et al., 2016; Huang et al., 2016; Guo et al., 2017; Mandáková et al., 2017a). With the most recent contribution studying >1400 nuclear exons and covering almost all tribes, there is the first family-wide phylogeny available providing most often significant relationships among tribes (Nikolov et al., 2019); however, it is lacking a dated chronogram and timeline of evolutionary history. Our time-calibrated chronogram is based on whole-plastome sequences of Rosidae, including 43 Brassicaceae species from all known major evolutionary lineages in Brassicaceae and is fully in congruence with earlier studies based on plastome sequence information (Hohmann et al., 2015; Guo et al., 2017). Therefore, ages of all major lineage splits in Brassicaceae obtained from this plastome-based timeline were used as temporal anchor points to calibrate divergence times on 48 tribe-wide ITS data sets. Notably, this ‘nested’ approach is necessary, since ITS- (as any other single or even multilocus) based phylogenies were not reliably resolving family-wide relationships (e.g. Bailey et al., 2006). Such an approach is conceptually close to super-network approaches (Huson et al., 2004; Koch et al., 2007; Lysak et al., 2009). Dating split times within Brassicaceae is difficult, because there are no reliably defined Brassicaceae fossils due to the enormous convergent evolution of any morphological character used in tribal and generic circumscriptions (Koch et al., 2003; Koch and Al-Shehbaz, 2009; Al-Shehbaz, 2012). One of those fossils, Thlaspi primaerum (Beilstein et al., 2010), has meanwhile been tested for its effect in divergence time estimates (Huang et al., 2016). Without using this contentious Brassicaceae fossil T. primaerum, previous studies provided varying estimates for Brassicaceae crown age based on disparate taxa, data sets and molecular dating software: approx. 32 Mya (Edger et al., 2015; Hohmann et al., 2015), approx. 35 Mya (Guo et al., 2017), approx. 38 Mya (Couvreur et al., 2010; Cardinal-McTeague et al., 2016; Huang et al., 2016) and approx. 40 Mya (Mandáková et al., 2017a) (Table 2). More important is the fact that plastome- and nuclear genome-derived divergence time estimates are converging (e.g. Hohmann et al., 2015; Huang et al., 2016). In this study, the onset of Brassicaceae crown group radiation was estimated as approx. 30 Mya (Supplementary Data Fig. S2). Since this estimate is based on plastome data, it accordingly constrains any individual ITS-based analysis. Hence, our study cannot be directly compared with solely ITS-based phylogenetic analyses providing crown group ages of Brassicaceae tribes (e.g. 15 Mya for Arabideae; Karl and Koch, 2013); and our plastome-derived estimates might slightly underestimate the divergence time of the respective evolutionary lineages because of a limited taxon sampling (e.g. Schulte, 2013; Marin and Hedges, 2018). However, it is important to mention that other plastome-derived divergence time estimates provide congruent age estimates (Hohmann et al., 2015; Guo et al., 2017); and various crown group age estimates of former ITS-based studies correspond well with our presented and family-wide calibrated data (e.g. Couvreur et al., 2010).

The major lineages (except Aethionemeae) evolved a little earlier than 20 Mya, within a very short preceding time span of approx. 0.69 million years, leading to the divergence of main Lineages I, II, III and IV (between nodes B = 21.26 and C = 20.57 Mya; Supplementary Data Fig. S2). This timing correlates with the onset of the Miocene, which also corresponds with a transient transition in Central Eurasia from densely forested regions with warm-temperate deciduous trees and shrubs (Bruch and Zhilin, 2007) towards more open vegetation types with abundant members of temperate plant families accompanied by some degree of climate cooling (Akgün et al., 2007; Syabryaj et al., 2007). The Brassicaceae do not contain any trees, and shrubs are very rare. Furthermore, Central Asia and the Irano-Turanian region are considered the cradle of Brassicaceae diversity (Karl and Koch, 2013), which also might correspond to this spatio-temporal evolutionary scenario. Brassicaceae are most often found in open vegetation types, and environmental conditions are often more extreme, but there are tribes in any of the three lineages with numerous mesophytic perennial species often adapted to woodland habitats (e.g. tribes Cardamineae, Yinshanieae, Hillielleae and Hesperideae).

Generally, Brassicaceae evolution appears to be correlated with major geological and climatic transitions during the Oligocene–Miocene–Pliocene. Brassicaceae crown group diversification started approx. 30 Mya with separation of tribe Aethionemeae from the remaining family representatives. This is also correlated with globally decreasing temperatures and permanent appearance of the Antarctic ice sheet during the Early Oligocene (Zachos et al., 2001). However, it was not until another significant drop in mean temperature after the Middle Miocene Climatic Optimum (MMCO; 18–14 Mya) that the majority of tribal diversification arose (Fig. 1). These findings may lead to the hypothesis that diversification and radiation of Brassicaceae seem to be driven by a general trend of global cooling and increasing aridity.

The combination of crown age and net diversification rate explains species richness patterns in tribal lineages

Major shifts in Brassicaceae diversification rates over time did not coincide with the above-discussed major geological and climatic transitions (Fig. 2). In total we detected 15 significant shifts with increasing rates in nine tribes, which mostly occurred during the Late Miocene and Pliocene. Generally, evolutionary diversification rates can be considered to be affected by various biotic and abiotic factors (Marin et al., 2018, and references therein). Therefore, it is obvious that there is no single causal explanation for Brassicaceae species radiation, and varying specific climatic and ecological factors may have influenced the evolutionary rates of the different tribes in a different way. However, it is remarkable that significant shifts as detected in our analyses are placed into an epoch (Late Miocene–Pliocene towards the Pleistocene) with further decreasing temperatures and increasing aridity (e.g. Messinian Salinity Crisis at around 6–5.3 Mya at the end of the Miocene).

Diversification patterns at greater taxonomic depth may provide the opportunity to gain deeper insights into the early cladogenetic events during the evolutionary history of the family Brassicaceae. In previous studies, a diversification rate shift was detected at the onset of the ‘core Brassicaceae’ (see above, a time window between 20.5 and 21.5 Mya) coinciding with the origin of novel structures of glucosinolates unique to the core Brassicaceae lineage (Edger et al., 2015), which may play a key role in the evolution of herbivory defence. Total taxon sampling was very small, so that no further shifts were detected. Similarly, with a sampling of 35 species from 26 genera, Cardinal-McTeaque et al. (2016) identified one single rate shift in Lineage II (among tribes Brassiceae and Sisymbrieae). In our study, we are capable of providing information of diversification shifts within tribes and thereby filling an important gap of knowledge. The ‘rate hypothesis’ and ‘time hypothesis’ are the two major hypotheses used to explain patterns of species richness (Wiens, 2011; Marin et al., 2018; Yan et al., 2018). Here, we used our data from Brassicaceae on a tribal level to test whether high and varying species richness is explained by age, increased diversification rates or both. The species circumscription of Brassicaceae taxa has been checked previously from a taxonomical and phylogenetic point of view, and a first checklist of the entire Brassicaceae has been released recently (Koch et al., 2018) which is used herein. Stadler et al. (2014) have demonstrated that the absence of a positive age–diversity relationship, or even a negative relationship, may occur when taxa are defined based on time (or correlated values, such as genetic distance, accumulation of morphological distinctness, etc.). In such cases it has been shown that crown age is superior to stem age as a measure of clade age (Stadler et al., 2014) as used in our study, also.

The differences in Brassicaceae species diversity among tribes (millions of years old monophyletic lineages with up to >500 species, Supplementary Data Table S2) appear to have been mainly impacted by heterogeneity in diversification rates (Table 3; Fig. 4). Although clade age alone failed to explain species richness patterns among Brassicaceae tribes, we cannot dismiss the importance of clade ages to species richness patterns (Scholl and Wiens, 2016), and a combined effect of time and net diversification rate has been discussed earlier for global richness patterns in Myrsinaceae (Yan et al., 2018). This scenario is also true for Brassicaceae. The combined effect of clade age and net diversification rate explains species richness of Brassicaceae tribes in a highly significant way (Fig. 4).

Positive relationships between richness and diversification rate are not inevitable, since the pattern of younger clades having faster rates of diversification (or older clades with slower rates) leads to weaker positive relationships between species richness and diversification rates (Kozak and Wiens, 2016; Scholl and Wiens, 2016). Studies among other systems revealed differing results, e.g. McPeek and Brown (2007) concluded for animal taxa that richness patterns were explained by clade age instead of diversification rates. However, Rabosky et al. (2012) examined stem group ages of clades across the eukaryotic tree of life and found no relationship between clade ages and spec ies richness; they concluded that there is no evidence that clade age can predict species richness at the analysed scale. Interestingly, Ricklefs (2006) found that tribes of passerine birds showed no relationship between age and diversity, but, when several tribes were sub-divided into younger subclades, diversity was positively related to age. This also highlights that the considered phylogenetic scale does matter and may influence the results obtained. As mentioned above, non-significant or even negative age–diversity relationship may be also attributable to taxonomic classifications (Stadler et al., 2014). These varying findings are also exemplified in this study by young Brassicaceae tribes with fast diversification rates (e.g. Boechereae; young tribal crown group age of 7.1 million years and highest total net diversification of 1.02), although species richness from over half of tribes (54.7 %) was explained sufficiently by net diversification rates (Fig. 4C).

Polyploidization serves as a constant ‘pump’ for species diversification

The combination of clade age and overall net diversification rate explains the species richness pattern on a tribal level throughout the past 22 million years. Although there is some congruence of Brassicaceae major diversification events with geological epochs and, thereby, environmental changes, we found no evidence to directly link those with diversification and species richness. However, one remarkable feature of Brassicaceae is its high percentage of polyploids. This means that polyploids in Brassicaceae have always been generated continuously and with high frequency. Past polyploidization events may even be traceable in the genome after many millions of years and effective diploidization (e.g. referred to as paleo- and mesopolyploids). After an ancestral polyploidization event at the onset of Brassicaceae evolution at about 40 Mya (Schranz et al., 2012), a series of mesopolyploidizations occurred in the ancestry of the following Brassicaceae tribes: Anastaticeae, Biscutelleae, Brassiceae, Cochlearieae, Heliophileae, Iberideae, Schizopetaleae, Thelypodieae, Microlepidieae, Physarieae (Mandáková et al., 2017b) and Stevenieae (K. Schneeberger, unpubl. data). These old polyploidization events were manifested with subsequent diversification, and they are randomly found over the Brassicaceae family tree. This fits very well with the frequency distribution of neopolyploids (Hohmann et al., 2015), which is also not following any pattern on a family level. This may be seen as the first evidence that in Brassicaceae polyploidization is a general phenomenon and may be considered an important intrinsic feature. As shown in Fig. 1, no tight link is observed between mesopolyploid whole-genome duplications and speciation rate shifts. Only five of the identified 12 mesopolyploid events (Cardamineae’s WGD event was only found in Leavenworthia) appear to be associated with upshifts in speciation rate. Mesopolyploid WGDs not only pre-date the origins of some species-rich tribes, but also occur in the ancestry of comparatively small tribes (Mandáková et al., 2017b). This suggests that there is no causal link between mesopolyploidy and diversification. However, we do see a signature of dynamic genome size evolution associated with shifts in diversification rates (Fig. 6). Shifts are not associated with genome size per se, but increased genome size variation within a given tribe (probably as a result of neopolyploidization followed by diploidization processes) is associated with a shift towards higher speciation rates. This association indicates the dynamic speciation processes via polyploidization, which is consistent with our finding that higher variation of monoploid GS is correlated with higher species number (Fig. 5C).

There is no ultimate consequence of increased species richness or elevated diversification simply because of mesopolyploid WGDs in Brassicaceae. The relationship between diversification and WGD has been explored at various levels across angiosperms, but support for a correlation remains equivocal (Clark and Donoghue, 2018). WGD often pre-dates the origins of many major clades of angiosperms and thus has been considered as the driving force for species diversification (Van de Peer et al., 2009; Landis et al., 2018; Ren et al., 2018), or acquisition of key innovations and complex traits (e.g. Huminiecki and Conant, 2012), although diversification rate shifts may be delayed for many millions of years (Tank et al., 2015), which was described as the WGD Radiation Lag-Time Model (Schranz et al., 2012).

Stebbins (1950) formulated decades ago that polyploidy may be only a minor primary force in diversification and that ‘polyploidy has been important in the diversification of species and genera within families, but not in the origin of the families and orders themselves’ (Stebbins, 1971). The Brassicaceae is an excellent example that this perspective changed significantly with increasing knowledge and reliable identification of past WGD (e.g. Mandáková et al., 2017b). It is not only that a WGD at the base of this family may have triggered diversification on the family level (e.g. compared with its sister lineage without WGD, Cleomaceae; Ren et al., 2018), but WGDs continuously contribute to diversification processes within a changing environmental context. Interestingly, Ren et al. (2018) found over the angiosperm clade not only a correlation of increased occurrence of WGD with epochs of global climate change, but the detected WGDs also supported a model of exponential gene loss during evolution with an estimated half-life of approx. 21.6 million years. This indicates the relevance of environmental factors in shaping selection and adaptation regimes by favouring lineages that underwent WGD, but also highlights the time span to be considered and during which the effect of WGDs can be detected (>10–20 million years; Estep et al., 2014).

The ‘lag phase’ between polyploidization events and subsequent diversification is the time for genome adjustments (i.e. post-polyploid diploidization) (Dodsworth et al., 2016; Mandáková and Lysak, 2018). Genome doubling per se is not responsible for the initiation of diversifications; rather, post-polyploid genome diploidization often associated with descending dysploidy may contribute to subsequent speciation and cladogenetic events (Hohmann et al., 2015; Mandáková and Lysak, 2018). Brassicaceae are continuously affected by WGDs (i.e. neopolyploidization), having approx. 43.3 % neopolyploids (Hohmann et al., 2015). Neopolyploidization can thus be considered a major mode of speciation, as it facilitates the generation of new combinations of genomes repeatedly and frequently (Estep et al., 2014). The Brassicaceae are a generally fast-evolving family, and most probably polyploidization per se serves as a constant ‘pump’ for a reservoir for species diversification in changing environments. In summary, mesopolyploid WGDs also contributed to the increased diversification rate in Brassicaceae, but they must be seen as remnant footprints of the process of ‘polyploidization and diploidization’ cycles (Baduel et al., 2018) rather than individual trigger events of increased speciation.

Conclusions

Molecular dating revealed that Brassicaceae diverged 29.94 Mya (95 % HPD = 26.78–33.16) during the Oligocene, and the majority of tribes started to diversify during the Miocene. The framework presented herein provides a temporal perspective for understanding the evolutionary history of the Brassicaceae and should also provide a useful guide in further studies of intertribal relationships, estimations of tribal stem ages, genome evolution and trait evolution in this model plant family. We acknowledge that molecular dating accuracy might influence specific results, but should not overturn the major conclusions drawn herein. Three main findings emerge from the presented analyses on Brassicaceae diversification. (1) Significant rate shifts are seen in 12 out of 52 tribes across Brassicaceae, which are decoupled from mesopolyploid WGDs. Shifts that were detected within tribes were randomly distributed over the time span, indicating no single epoch contributing to a major burst in Brassicaceae diversification. However, the Pliocene–Pleistocene is playing a major role for present-day Brassicaceae diversity and highlights that diversification of Brassicaceae is generally favoured by cooler and drier conditions. Pleistocene glacial/deglaciation cycles may have contributed to the maintenance of the high diversification rate in Brassicaceae. (2) The combined effect of older crown age and faster net diversification rate is sufficient to explain the high species richness across Brassicaceae tribes. (3) Brassicaceae species have approx. 43.3 % neopolyploids, suggesting WGD as a constant driving force for species diversification. With the passage of time, neopolyploids turn into mesopolyploids and are the source for future diversification. Our results demonstrate that shifts in diversification rate are not consistently associated with mesopolyploid WGDs detected retrospectively, and WGDs (either meso- or neopolyploid) serve as a constant ‘pump’ for species diversification.

SUPPLEMENTARY DATA

Supplementary data are available online at https://academic.oup.com/aob and consist of the following. Table S1: species and data description of plastid genomes used in this study. Table S2: sampled Brassicaceae taxa, accession numbers, best-fit models and sampling fractions for ITS data sets. Table S3: best-fit models of sequence evolution and partitioning schemes selected by PartitionFinder for phylogenetic reconstruction and divergence time estimation. Table S4: references of previous phylogenetic studies on each tribe. Table S5: mean and 95 % HPD age estimates of the crown nodes of 48 tribes in Brassicaceae. Figure S1: maximum likelihood tree for the Rosidae based on whole plastome sequences. Figure S2: time-calibrated phylogeny inferred from whole plastome sequences for the Rosidae using BEAST with four fossil calibrations and tree root height. Figure S3: summarizing illustration of Brassicaceae phylogeny and distribution of selected characters. File S1: alignment of Rosidae plastome phylogeny. File S2: ITS alignments and BEAST trees for every tribe. Available from DRYAD doi:10.5061/dryad.kr4rf80. File S3: BAMM results of 42 Brassicaceae tribes.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Markus Kiefer for continuous support for inhouse IT infrastructure and software.

Present address: South-Siberian Botanical Garden, Altai State University, Lenina 61, 656049 Barnaul, Russia

FUNDING

This project was funded by DFG grant KO2302-13 (Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft) to M.A.K. X.C.H. was supported by a scholarship from the China Scholarship Council (CSC) (201406820012).

LITERATURE CITED

- Akgün F, Kayseri MS, Akkiraz MS. 2007. Palaeoclimatic evolution and vegetational changes during the Late Oligocene–Miocene period in Western and Central Anatolia (Turkey). Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology 253: 56–90. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Shehbaz IA. 2012. A generic and tribal synopsis of the Brassicaceae (Cruciferae). Taxon 61: 931–954. [Google Scholar]