Abstract

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is a serious neurodegenerative condition that affects millions of people across the world. Recently machine learning models have been used to predict the progression of AD, although they frequently do not take advantage of the longitudinal and structural components associated with multi-modal medical data. To address this, we present a new algorithm that uses the multi-block alternating direction method of multipliers to optimize a novel objective that combines multi-modal longitudinal clinical data of various modalities to simultaneously predict the cognitive scores and diagnoses of the participants in the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative cohort. Our new model is designed to leverage the structure associated with clinical data that is not incorporated into standard machine learning optimization algorithms. This new approach shows state-of-the-art predictive performance and validates a collection of brain and genetic biomarkers that have been recorded previously in AD literature.

Keywords: Alzheimer’s Disease, Biomarker Identification, Multi-Modal, Regression, Classification, the Alternating Direction Method of Multipliers

1. Introduction

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is a neurodegenerative disorder that has serious mental and financial consequences for those affected and their families. AD is characterized by progressive declines of memory and cognitive capabilities. According to the Alzheimer’s Association1 5.7 million people in the United States are currently suffering from AD-related dementia. In 2018 alone, the total financial cost associated with health care, long-term care, and hospice services for patients suffering from dementia was estimated to be $277 billion. It is forecasted that by 2050, the number of people suffering from AD will surpass 13.8 million. Furthermore, the Alzheimer’s Association emphasizes that early detection and diagnosis of individuals with AD could save up to $7.9 trillion in associated medical costs. With the projected increase in individual hardship and financial burden caused by AD, it is essential that the scientific community develop computational methods for early diagnosis and treatment of AD.

A central research component, designed to assist in early identification of dementia, has focused on discovering characteristic biomarkers that are closely associated with the development of AD. This branch of research has been driven by the successful development and deployment of a variety of non-invasive clinical observations such as positron emission tomography (PET), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans, and genetic analysis through the identification of single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs). By way of public-private partnerships, such as the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI),39 clinical data from each of theses modalities have been made publicly available to the scientific community. Through the effective analyses of these AD data sources, we are able to build models that have the potential to help clinical researchers narrow down the array of phenotypic and genetic measures that are predictive of cognitive decline. Given the complexity and size of these clinical datasets, there has been a concerted effort to design new machine learning methods to assist in the discovery of AD-related biomarkers.

In recent years, various computational methods18,27,40,41 have been proposed to identify biomarkers associated with AD. Although these methods have shown good predictive performance, they only incorporate clinical data that is collected at a single time-point. Since these approaches rely on a single point in time, they are unable to identify longitudinal patterns found across patient data. Recent works3,15,33,34 explored using longitudinal data to predict an AD diagnosis, which validated that specific regions of the brain (derived from neuroimaging modalities) are the most useful for diagnosing AD over time.

With the above recognitions, in this work we aim to develop a principled approach to incorporate longitudinal data from multiple data sources that the ADNI provides. Through extensive empirical studies, our new approach has shown great promise in predicting cognitive scores, diagnoses and identifying AD-relevant genetic and phenotypic biomarkers. Specifically, we present the following:

-

-

A principled strategy for incorporating tensor data (e.g. longitudinal) collected from multiple data sources, which leads to a new objective that is able to combine multimodal longitudinal clinical data of various modalities to simultaneously predict the cognitive scores and diagnoses of the participants in the ADNI cohort.

-

-

An effective optimization algorithm, using the multi-block alternating direction method of multipliers, to optimize the proposed objective.

-

-

A collection of phenotypic biomarkers, some of which have been shown by previous research to be predictive of cognitive decline, identified by our model.

2. Methods

In this manuscript, we write tensors as cursive uppercase letters (A, B, C,...), matrices as bold uppercase letters (A, B, C,...), vectors as bold lowercase letters (a, b, c,...), and scalars as lowercase letters (a, b, c,...). Given a matrix M, its i-th row and j-th column are denoted as mi and mj respectively. We define the Frobenius norm of the m × n matrix A as .

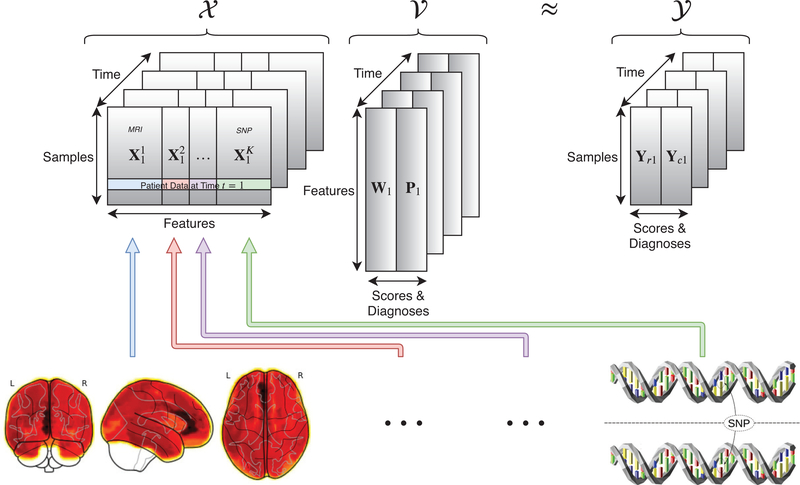

The input imaging features are represented by the tensor: Each Xt represents the input observations for n patients with d features at a given time t. Each Xt can be further broken down into K modalities: . The output diagnoses and cognitive scores are represented by another tensor:. Each is a concatenation of the cognitive scores (for regression) and diagnosis (for classification) for n patients at time t. The goal of our proposed new machine learning model is to learn a joint regression and classification model represented by the tensor where and are the learned coefficient matrices for the respective regression and classification tasks. The input output , and learned coefficient tensors are illustrated in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Visualization of the input (X), coefficient (V) and output (Y) tensors. In each time-point of X the K modalities (MRI, SNP, etc.) are explicitly defined to facilitate the calculation of the group l1-norm. The goal of the proposed method is to learn a joint model V that can effectively map X to the cognitive scores and diagnoses encoded in Y.

2.1. The Longitudinal Joint Learning Model

A key idea behind our approach is to perform the regression and classification tasks at the same time. Joint regression and classification can help discover more robust patterns than those discovered when classification and regression are performed separately.3,31,35 In order to link the regression and classification tasks, following the large body of previous works3,31,35 we introduce the following regularized joint learning model:

| (1) |

where and are the prescribed loss functions associated with the regression and classification tasks respectively. Here the regularization function is applied to the matrix unfolded from tensor , i.e., we construct by taking the (Wt, Pt) matrix pairs at each time-point and joining them along their columns.33,34 This joint regularization scheme in Eq. (1) is designed to identify features in that are predictive of both clinical diagnoses and cognitive scores. This approach reasonably assumes that there exists a relationship between the classification and regression tasks. For example, if a patient does poorly on a given cognitive test then they are more likely to be diagnosed with AD. Regularizing the joint coefficient matrices allows us to discover biomarkers that are strongly associated with the two related tasks. We design the regularization function as following.

First, in order to associate the longitudinal imaging and genetic markers to predict cognitive scores and diagnoses over time, we apply the widely used l2,1-norm20,32 to the unfolded coefficient matrix .

Second, as we combine K different modalities (MRI, SNP, FreeSurfer, etc.) together, it is critical for our model to differentiate the impact that each modality has on the joint model. In order to capture the impact of each modality, we leverage the group l1-norm (G1 -norm):3,35–37 , where Vj is a matrix constructed of the rows in V that corresponds to the j-th modality in.

Finally, we know that as AD develops, many cognitive measures are related to one another within the same modality. In order to account for this inter-modal relationship, we leverage the trace norm regularization21,24,33,34,38 of , where σi (V) are the singular values of V.

Bringing together these three regularizations, we present our new objective as following:

| (2) |

where the first term is the multivariate regression loss at each longitudinal time-point; and the second term represents the loss of cC × T one-vs-all multi-class support-vector machine (SVM) penalized via the hinge-loss, where is the class label associated with i-th patient at time t, and is the bias associated with the (k × t)-th SVM. The notation (·)+ is defined as (a)+ = max(0, a).

2.2. The Solution Algorithm Using the Multi-Block ADMM

While the objective of our new method in Eq. (2) is clearly and reasonably motivated, all its terms are dependent on . Thus, it is difficult to optimize this objective in general. To solve the proposed objective, we derive an efficient iterative algorithm using the multi-block extension8 of the alternating direction method of multipliers (ADMM).2

The ADMM aims to decouple a larger and more difficult problem into a series of smaller sub-problems that are easier to solve.2 An extension to ADMM, known as multi-block ADMM,8 is designed to extend the ADMM framework to optimize functions of the following form:

| (3) |

Equation. (3) can be solved by minimizing the following unconstrained objective:2,8

| (4) |

where y is a Lagrangian multiplier and μ > 0 is a constant. The objective in Eq. (4) can be solved by the following iterative procedure that updates each xk (primal) and the Lagrangian variable y (dual):

| (5) |

where ρ > 1 is a constant. The process described above in Eq. (5) is repeated until the algorithm converges. In order to decouple the terms containing in Eq. (2), we introduce four new variables and a set of corresponding equality constraints as following:

| (6) |

Since each yikt in the second term must be equal to either −1 or 1, we can use the following to move from Eq. (2) to Eq. (6):. 22 Then we can solve Eq. (6) by minizing the following ojective:

| (7) |

where λikt, Σ, Θ, and Ω are the Lagrangian multipliers. The updates for each of the primal variables can be calculated by taking the derivative of Eq. (7), with respect to each of the primal variables, setting the resulting equation equal to zero, and solving for the associated primal variable. Due to space considerations, we will provide the detailed mathematical derivation for each variable in an extended journal version of this paper. The derived parameter updates are provided in Algorithm 1.

3. Experiments

Data.

We downloaded MRI scans, SNP genotypes, and demographic information for 821 ADNI-1 participants. We performed FreeSurfer automated parcellation on the MRI data by following Risacher et al.25 and extracted mean modulated gray matter measures for 90 target regions of interest. We followed the SNP quality control steps discussed in Shen et al.26 We also downloaded the longitudinal scores of the participants’ Rey’s Auditory Verbal Learning Test (RAVLT) and their clinical diagnosis: Alzheimer’s disease (AD), mild cognitive impairment (MCI), and healthy control (HC). All the participants with no missing Baseline/Month 6/Month 12/Month 24 MRI measurements, SNP genotypes, and cognitive measures were included in this study, resulting in a set of 412 subjects (79 AD, 190 MCI, 143 HC at Baseline, 86 AD, 180 MCI, 155 HC at Month 6, 111 AD, 155 MCI, 146 HC at Month 12, and 155 AD, 110 MCI, 147 HC at Month 24).

Settings.

The performance and standard deviation results reported in Table 1 and Table 2 are calculated from ten five-fold cross validation experiments applied to and ; in-between each cross validation experiment and are randomly shuffled. Each method reported in the following experiments were tuned via a reasonable hyper parameter search to guarantee a fair comparison. The optimal tuning parameters are chosen by the model that provides the best regression or classification performance during a single five-fold cross validation experiment. In choosing the parameters for our new method, we fine tuned the parameters, described in Eq. (7), by applying powers of 10 between 10−5 and 105 and choosing the best model based on the average multitask performance. Following the search, we achieve the best performance at and ρ = 1.2, which we use in all our experiments.

Table 1.

Root mean-squared error values and standard deviations between the true and predicted RAVLT scores for the proposed method compared against an array of widely used machine learning algorithms. RAVLT scores vary between 0 and 74.

| Model | RAVLTTOT | RAVLT30 | RAVLT30-RECOG |

|---|---|---|---|

| Linear | 4.19e11±7.20e11 | 1.06e12±1.34e12 | 8.85e11±1.06e12 |

| Ridge | 18.9±0.888 | 20.5±1.17 | 19.6±0.872 |

| Lasso | 19.4±0.913 | 21.1±1.29 | 20.0±0.957 |

| MLP | 19.2±0.961 | 20.7±1.25 | 19.8±1.05 |

| Our method | 12.7±1.05 | 19.7±1.30 | 19.8±0.928 |

Table 2.

Multi-class F1 scores and their standard deviations, of the iterated five-fold cross validation experiments, for predicting the cognitive status of ADNI participants averaged over each time-point.

| Model | F1(AD) | F1 (MCI) | F1 (HC) | F1 (All) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Logistic | 0.265±0.0276 | 0.500±0.0353 | 0.313±0.0562 | 0.396±0.0299 |

| RandomForest | 0.325±0.0201 | 0.415±0.0466 | 0.401±0.0308 | 0.386±0.0325 |

| SVM | 0.289±0.0341 | 0.474±0.0450 | 0.363±0.0254 | 0.396±0.0286 |

| KNN | 0.330±0.0415 | 0.472±0.0524 | 0.410±0.0388 | 0.420±0.0332 |

| MLP | 0.312±0.0588 | 0.475±0.0523 | 0.341±0.0737 | 0.400±0.0366 |

| ElasticNet4 | 0.255±0.070 | 0.447±0.0485 | 0.405±0.0655 | 0.390±0.0284 |

| LinearSVM13 | 0.308±0.038 | 0.448±0.0381 | 0.332±0.0364 | 0.378±0.0311 |

| Our method | 0.496±0.0419 | 0.415±0.0222 | 0.477±0.0308 | 0.459±0.0125 |

3.1. Performance

Regression.

We compare our algorithm against multivariate linear regression (Linear), l2- regularized linear regression (Ridge), l1-regularized linear regression (Lasso),29 and multi-layer perception regression (MLP).7 In Table 1, our new method shows superior regression performance when compared to the aforementioned methods. This is likely because our method incorporates information provided by the longitudinal regularizations across both tasks.

Algorithm 1:

The solution algorithm to optimize Eq. (2).

|

Classification.

We report the iterated five-fold cross validation results on the classification task of our method compared to a variety of popular machine learning algorithms for classification in Table 2. We compare our method against logistic regression (Logistic), random forest classifier (RandomForest), support vector machine using a sigmoid-kernel (SVM), k-nearest neighbors classifier (KNN), logistic regression with elastic net regularization (ElasticNet),4 and a linear support vector machine (LinearSVM).13 Both ElasticNet and LienarSVM have been used in the past to classify patients with AD vs. HC. From Table 2 we can see that our algorithm shows significant improvement when predicting AD and HC diagnoses. This improvement does not appear to extend to MCI diagnoses, where logistic regression improves upon our model. This disparity is likely because the cc one-vs-all multi-class SVMs constructed in are not normalized against one another. Nonetheless outperforms the detection of HC and AD in ADNI participants when compared to the methods in Table 2.

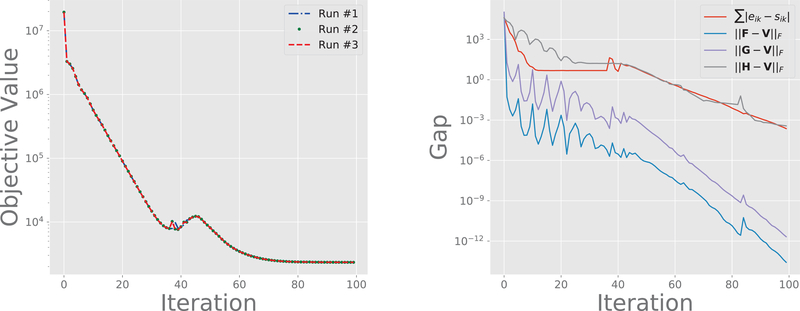

3.2. Empirical Convergence

It is well known that the multi-block ADMM approach described in Algorithm 1 does not necessarily converge.5 So, in order to determine convergence properties of the proposed algorithm, we perform the following empirical analyses. First, we want to determine whether the initialization of the model has a significant effect on the convergence of Algorithm 1. Second, we want to determine whether our multi-block optimization scheme actually matches the constraints incorporated by the augmented Lagrangian after a reasonable number of iterations.

To analyze the first issue we apply our algorithm to the same dataset three times and plot the objective on the left-hand-side of Fig. 2. This plot shows that, even with random initialization, our algorithm converges to a similar solution after only one-hundred iterations. To analyze the second issue, we plot the difference between the introduced variables (eik, F, G, H) designed to decouple the original objective in Eq. (2). As can be seen on the right-hand-side of Fig. 2, once the objective has converged the difference between the decoupled variables and the variables that they replaced are within 10−3 after one-hundred iterations of the proposed method. The convergence of the overall objective across differently initialized runs, and the eventual gap decrease, provide empirical evidence for the convergence of the proposed multi-block ADMM algorithm.

Fig. 2.

Left: The proposed objective in Eq. 7 plotted over one-hundred iterations of Algorithm 1. In each run the primal and dual variables are randomly re-initialized. Right: The difference between the introduced variables designed to decouple the terms in Eq. (2).

3.3. Biomarker Identification

In addition to predictive performance, our method is easily interpreted and can assist in the identification of AD-related biomarkers.

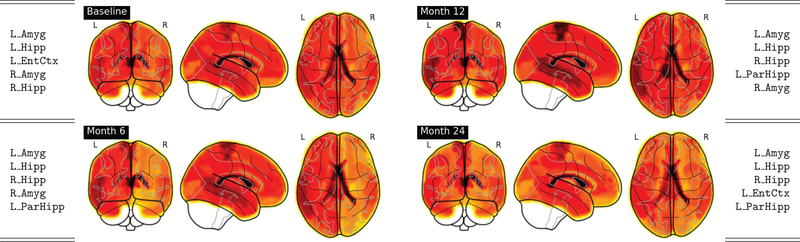

MRI.

In Fig. 3 we plot the magnitudes, derived from , of coefficients associated with the FreeSurfer features contained in . We can clearly see that the biomarkers discovered across all four time-points are all longitudinally consistent. Visually, the brain heat-map images from Baseline to Month 24 look almost identical; this illustrates the power of the l2,1-norm regularization that provides our algorithm with the ability to identify longitudinally consistent biomarkers. This consistency is especially important from the clinical perspective. We find that the biomarkers identified by our method are strongly supported by previous research. For example, Mu et al.19 provide a review documenting how the hippocampus is affected by the early stages of AD; this part of the brain is one of the top-5 regions discovered by our model in Fig. 3. Van Hoesen et al.30 provide strong evidence that a severely damaged entorhinal cortex (Broadmann’s area 28) is observed in patients suffering from AD; the thickness of the entorhinal cortex is also identified by our method. Furthermore, Poulin et al.23 analyzed the impact of amygdala atrophy and determined that it was highly predictive of AD severity during the early clinical stages of AD; this finding is also supported by the FreeSurfer brain regions identified by our model.

Fig. 3.

Top-5 ordered biomarkers in the FreeSurfer modality at each time-point. The identified biomarkers, listed on the far-left and far-right, are ordered from largest coefficient (top) to smallest (bottom) derived from V.

SNP.

In Table 3 we rank the top-30 SNPs discovered by our algorithm. As we expect, the highest impact SNP discovered by our algorithm is rs429358; this SNP, known frequently as the APOE-ε4 allele, has been found12 to be highly predictive of early-onset AD. The authors’ note that approximately one third of the SNPs identified by our new method have previously been linked to AD; this further validates the utility of our approach in discovering well-known, as well as possibly-novel, AD biomarkers.

Table 3.

The top-30 SNPs identified by our algorithm.

| 1. rs42935811,12 | 7. rs17477673 | 13. rs7894245 | 19. rs2994978 | 25. rs2125256 |

| 2. rs7870463 | 8. rs11218301 | 14. rs431044610 | 20. rs6746923 | 26. rs17477827 |

| 3. rs9461735 | 9. rs11687624 | 15. rs43940111 | 21. rs18011339 | 27. rs2177828 |

| 4. rs6139494 | 10. rs40550911,16 | 16. rs1556758 | 22. rs794593117 | 28. rs703678114 |

| 5. rs17561 | 11. rs17123514 | 17. rs2248478 | 23. rs4631890 | 29. rs2627641 |

| 6. rs74900828 | 12. rs10512186 | 18. rs6037894 | 24. rs471343214 | 30. rs17209374 |

4. Conclusion

In this work we present a multi-block alternating direction method of multipliers approach to optimize the proposed new model that incorporates the l2,1 -norm, group l1-norm and trace-norm regularizations to discover important features contained in the ADNI dataset. This work illustrates a principled approach to combine multi-modal data using clinical time series data. The presented optimization algorithm is able to identify clinically relevant biomarkers and shows state-of-the-art predictive performance when jointly predicting the cognitive scores and diagnoses of ADNI participants.

Acknowledgements

L. Brand, K. Nichols and H. Wang were partially supported by the National Science Foundation (NSF) under the grants of IIS 1652943, IIS 1849359 and CNS 1932482; H. Huang was partially supported by the NSF under the grants of IIS 1836938, DBI 1836866, IIS 1845666, IIS 1852606, IIS 1838627 and IIS 1837956 and by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) under the grant of R01 AG049371; L. Shen was partially supported by the NSF under the grant of IIS 1837964 and by the NIH under the grants of R01 EB022574 and RF1 AG063481.

Footnotes

Data used in preparation of this article were obtained from the ADNI database (adni.loni.usc.edu). As such, the investigators within the ADNI contributed to the design and implementation of ADNI and/or provided data but did not participate in analysis or writing of this report. A complete listing of ADNI investigators can be found at: adni.loni.usc.edu/wp-content/uploads/how_to_apply/ADNI_Acknowledgement_List.pdf

Contributor Information

Lodewijk Brand, Department of Computer Science, Colorado School of Mines, Golden, CO 80401, USA.

Kai Nichols, Department of Computer Science, Colorado School of Mines, Golden, CO 80401, USA.

Hua Wang, Department of Computer Science, Colorado School of Mines, Golden, CO 80401, USA.

Heng Huang, Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA 15206, USA.

Li Shen, Department of Biostatistics Epidemiology and Informatics, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA 19104, USA.

References

- 1.Association, A., et al. : 2018 alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. Alzheimer’s & Dementia 14(3), 367–429 (2018) [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boyd S, et al. : Distributed optimization and statistical learning via the alternating direction method of multipliers. Foundations and Trends® in Machine learning 3(1), 1–122 (2011) [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brand L, et al. : Joint high-order multi-task feature learning to predict the progression of alzheimer’s disease. In: International Conference on Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention pp. 555–562. Springer; (2018) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Casanova R, et al. : High dimensional classification of structural mri alzheimer’s disease data based on large scale regularization. Frontiers in neuroinformatics 5, 22 (2011) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen C, et al. : The direct extension of admm for multi-block convex minimization problems is not necessarily convergent. Mathematical Programming 155(1–2), 57–79 (2016) [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hamilton G, et al. : The role of ece1 variants in cognitive ability in old age and alzheimer’s disease risk. American Journal of Medical Genetics Part B: Neuropsychiatric Genetics 159(6), 696–709 (2012) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hinton GE: Connectionist learning procedures. In: Machine learning, pp. 555–610 (1990) [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hong M, Luo ZQ: On the linear convergence of the alternating direction method of multipliers. Mathematical Programming 162(1–2), 165–199 (2017) [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hua Y, et al. : Association between the mthfr gene and alzheimer’s disease: a meta-analysis. International journal of neuroscience 121(8), 462–471 (2011) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jones L, et al. : Genetic evidence implicates the immune system and cholesterol metabolism in the aetiology of alzheimer’s disease. PloS one 5(11), e13950 (2010) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jun G, et al. : Comprehensive search for alzheimer disease susceptibility loci in the apoe region. Archives of neurology 69(10), 1270–1279 (2012) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kamboh M, et al. : Genome-wide association study of alzheimer’s disease. Translational psychiatry 2(5), e117 (2012) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Klöppel S, et al. : Automatic classification of mr scans in alzheimer’s disease. Brain 131(3), 681–689 (2008) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kundu S, Kang J.: Semiparametric bayes conditional graphical models for imaging genetics applications. Stat 5(1), 322–337 (2016) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li K, et al. : Prediction of conversion to alzheimer’s disease with longitudinal measures and time-to-event data. Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease 58(2), 361–371 (2017) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ma C, et al. : The tt allele of rs405509 synergizes with apoe 4 in the impairment of cognition and its underlying default mode network in non-demented elderly. Current Alzheimer Research 13(6), 708–717 (2016) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McCarthy JJ, et al. : The alzheimer’s associated 5’ region of the sorl1 gene cis regulates sorl1 transcripts expression. Neurobiology of aging 33(7), 1485–e1 (2012) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Moradi E, et al. : Machine learning framework for early mri-based alzheimer’s conversion prediction in mci subjects. Neuroimage 104, 398–412 (2015) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mu Y, Gage FH: Adult hippocampal neurogenesis and its role in alzheimer’s disease. Molecular neurodegeneration 6(1), 85 (2011) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nie F, et al. : Efficient and robust feature selection via joint l2,1-norms minimization. In: Advances in neural information processing systems. pp. 1813–1821 (2010) [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nie F, et al. : Robust matrix completion via joint schatten p-norm and lp-norm minimization. In: 2012 IEEE 12th International Conference on Data Mining pp. 566–574. IEEE; (2012) [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nie F, et al. : New primal svm solver with linear computational cost for big data classifications. In: Proceedings of the 31st International Conference on International Conference on Machine Learning-Volume 32 pp. II–505. JMLR.org; (2014) [Google Scholar]

- 23.Poulin SP, et al. : Amygdala atrophy is prominent in early alzheimer’s disease and relates to symptom severity. Psychiatry Research: Neuroimaging 194(1), 7–13 (2011) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Recht B, et al. : Guaranteed minimum-rank solutions of linear matrix equations via nuclear norm minimization. SIAM review 52(3), 471–501 (2010) [Google Scholar]

- 25.Risacher SL, et al. : Longitudinal mri atrophy biomarkers: relationship to conversion in the adni cohort. Neurobiology of aging 31(8), 1401–1418 (2010) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shen L, et al. : Whole genome association study of brain-wide imaging phenotypes for identifying quantitative trait loci in mci and ad: A study of the adni cohort. Neuroimage 53(3), 1051–1063 (2010) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shen L, et al. : Identifying neuroimaging and proteomic biomarkers for mci and ad via the elastic net. In: International Workshop on Multimodal Brain Image Analysis pp. 27–34. Springer; (2011) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Silverman D, et al. : Value of amyloid imaging for predicting conversion to dementia in mci subjects with initially indeterminate fdg-pet scans. Alzheimer’s & Dementia: The Journal of the Alzheimer’s Association 10(4), P18–P19 (2014) [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tibshirani R.: Regression shrinkage and selection via the lasso. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society: Series B (Methodological) 58(1), 267–288 (1996) [Google Scholar]

- 30.Van Hoesen GW, et al. : Entorhinal cortex pathology in alzheimer’s disease. Hippocampus 1(1), 1–8 (1991) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang H, et al. : Identifying ad-sensitive and cognition-relevant imaging biomarkers via joint classification and regression. In: International Conference on Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention pp. 115–123. Springer; (2011) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang H, et al. : Sparse multi-task regression and feature selection to identify brain imaging predictors for memory performance. In: 2011 International Conference on Computer Vision pp. 557–562. IEEE; (2011) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang H, et al. : From phenotype to genotype: an association study of longitudinal phenotypic markers to alzheimer’s disease relevant snps. Bioinformatics 28(18), i619–i625 (2012) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang H, et al. : High-order multi-task feature learning to identify longitudinal phenotypic markers for alzheimer’s disease progression prediction. In: Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems. pp. 1277–1285 (2012) [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wang H, et al. : Identifying disease sensitive and quantitative trait-relevant biomarkers from multidimensional heterogeneous imaging genetics data via sparse multimodal multitask learning. Bioinformatics 28(12), i127–i136 (2012) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wang H, et al. : Heterogeneous visual features fusion via sparse multimodal machine. In: Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition pp. 3097–3102 (2013) [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wang H, et al. : Multi-view clustering and feature learning via structured sparsity. In: International Conference on Machine Learning pp. 352–360 (2013) [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wang H, et al. : Low-rank tensor completion with spatio-temporal consistency. In: Twenty-Eighth AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence (2014) [Google Scholar]

- 39.Weiner MW, et al. : The alzheimer’s disease neuroimaging initiative: a review of papers published since its inception. Alzheimer’s & Dementia 9(5), e111–e194 (2013) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yan J, et al. : Cortical surface biomarkers for predicting cognitive outcomes using group l2, 1 norm. Neurobiology of aging 36, S185–S193 (2015) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhang D, et al. : Multimodal classification of alzheimer’s disease and mild cognitive impairment. Neuroimage 55(3), 856–867 (2011) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]