Abstract

Background

This study was performed to identify genes related to acquired trastuzumab resistance in gastric cancer (GC) and to analyze their prognostic value.

Methods

The gene expression profile GSE77346 was downloaded from the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database. Differentially expressed genes (DEGs) were obtained by using GEO2R. Functional and pathway enrichment was analyzed by using Gene Ontology (GO) and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG). Search Tool for the Retrieval of Interacting Genes (STRING), Cytoscape, and MCODE were then used to construct the protein-protein interaction (PPI) network and identify hub genes. Finally, the relationship between hub genes and overall survival (OS) was analyzed by using the online Kaplan-Meier plotter tool.

Results

A total of 327 DEGs were screened and were mainly enriched in terms related to pathways in cancer, signaling pathways regulating stem cell pluripotency, HTLV-I infection, and ECM-receptor interactions. A PPI network was constructed, and 18 hub genes (including one upregulated gene and seventeen downregulated genes) were identified based on the degrees and MCODE scores of the PPI network. Finally, the expression of four hub genes (ERBB2, VIM, EGR1, and PSMB8) was found to be related to the prognosis of HER2-positive (HER2+) gastric cancer. However, the prognostic value of the other hub genes was controversial; interestingly, most of these genes were interferon- (IFN-) stimulated genes (ISGs).

Conclusions

Overall, we propose that the four hub genes may be potential targets in trastuzumab-resistant gastric cancer and that ISGs may play a key role in promoting trastuzumab resistance in GC.

1. Introduction

Gastric cancer is the fifth most commonly diagnosed cancer and the third leading cause of cancer-related deaths [1]. The majority of gastric cancer cases are associated with lifestyle factors [2] and infectious agents, including the bacterium Helicobacter pylori [2, 3] and Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) [4, 5]. Although many biomarkers (including HER2, E-cadherin, fibroblast growth factor receptor, PD-L1, and TP53) have been studied as prognostic markers, the 5-year survival rate of gastric cancer remains low [6].

The human epidermal growth factor receptor-2 (HER-2) gene, a proto-oncogene mapped to chromosome 17 (17q12–q21), is frequently found to be amplified and/or overexpressed in gastric cancer [7]. Additionally, HER2 positivity is often associated with a worse prognosis [8, 9]. A phase III trial (the ToGA trial) confirmed that trastuzumab, a HER-2 monoclonal antibody, markedly improved the outcome of HER-2-positive (HER2+) gastric cancer patients [10]. However, a large proportion of patients developed resistance to trastuzumab after continuous treatment despite the effectiveness of this therapeutic [11]. Thus, there is an urgent need to explore the molecular mechanisms of trastuzumab resistance in gastric cancer and to identify effective biomarkers.

Bioinformatics analysis has been widely used to identify key genes in cancer. Interestingly, Piro et al. obtained the gene expression profiles of trastuzumab-sensitive and trastuzumab-resistant cell lines and found that fibroblast growth factor receptor 3 (FGFR3) was associated with trastuzumab resistance in gastric cancer [12]. In the present study, we aimed to further screen DEGs and predict their underlying function by utilizing the same data. More importantly, hub genes affecting trastuzumab resistance in GC patients were identified by a using protein-protein interaction (PPI) network, PPI network modules, and survival analyses.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Microarray Data

The microarray data for GSE77346 deposited by Piro et al. into the GEO database were obtained on the GPL10558 platform (Illumina HumanHT-12 v4.0 Expression BeadChip). The expression profiles are provided for five samples, including one sample of a trastuzumab-sensitive cell line (NCI-N87) and four samples of trastuzumab-resistant cell lines (N87-TR1, N87-TR2, N87-TR3, and N87-TR4).

2.2. Identification of DEGs

The web tool GEO2R (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/geo2r/) was utilized to screen differentially expressed genes (DEGs) between trastuzumab-resistant and trastuzumab-sensitive gastric cancer cells. These DEGs were identified as important genes that may play an important role in the development of gastric cancer. The cutoff criterion were ∣log fold change (FC)∣ > 3.0 and P < 0.01.

2.3. Functional and Pathway Enrichment Analysis

We performed Gene Ontology (GO) and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway enrichment analyses by using the Database for Annotation, Visualization, and Integrated Discovery (DAVID), which is a comprehensive set of functional annotation tools. A P value of <0.05 was set as the cutoff criterion.

2.4. PPI Network and Module Selection

The Search Tool for the Retrieval of Interacting Genes (STRING) database was used to analyze the PPI network of DEGs. Then, the results were visualized by Cytoscape software. The cutoff criterion for the combined score was >0.4. Subsequently, the degrees of genes in the PPI network and the MCODE plugin in Cytoscape were used to identify hub genes. Genes with degree ≥ 13 or MCODE score ≥ 10 were identified as hub genes. Furthermore, MCODE was used to screen modules in the PPI network.

2.5. mRNA Expression of the Hub Genes

UALCAN (http://ualcan.path.uab.edu/index.html) [13], an interactive web portal, can be used to analyze the relative expression of a query gene across tumor and normal samples. The expression levels of the 18 hub genes were analyzed in gastric cancer and normal samples. The calculated P value is shown.

2.6. Survival Analysis Based on the Hub Genes

The Kaplan-Meier plotter (KM plotter) tool (http://kmplot.com/analysis/index.php?p=background) was used to predict the prognostic value of the hub genes in gastric cancer patients [14]. The patients were divided into two groups according to the particular gene expression level (high vs. low expression). The OS of the two patient groups was then analyzed based on these categories. The hazard ratios (HRs) with 95% confidence intervals and log rank P values are shown.

3. Results

3.1. Identification of DEGs

After data preprocessing, a total of 327 genes were identified, including 128 upregulated genes and 199 downregulated genes.

3.2. GO and KEGG Pathway Enrichment Analyses

We conducted GO and KEGG pathway enrichment analyses by using DAVID software. The top five GO terms of the DEGs are shown in Table 1. Regarding biological processes, DEGs were significantly involved in the type I interferon signaling pathway, negative regulation of viral genome replication, cell proliferation, positive regulation of the apoptotic process, and extracellular matrix organization. Regarding the cellular component, DEGs were enriched in the extracellular exosome, intermediate filament, cytoplasm, proteinaceous extracellular matrix, and basolateral plasma membrane. For molecular function, DEGs were enriched in structural molecule activity, calcium ion binding, protein homodimerization activity, 2′-5′-oligoadenylate synthetase activity, and fibronectin binding. The most enriched KEGG pathways included pathways in cancer, signaling pathways regulating stem cell pluripotency, HTLV-I infection, ECM-receptor interaction, and central carbon metabolism in cancer.

Table 1.

Functional and pathway enrichment analyses of the DEGs in trastuzumab-resistant gastric cancer.

| Category | Description | Count | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GO function | BP | Type I interferon signaling pathway | 13 | 1.04E − 09 |

| BP | Negative regulation of viral genome replication | 10 | 2.46E − 08 | |

| BP | Cell proliferation | 23 | 5.99E − 07 | |

| BP | Positive regulation of apoptotic process | 18 | 2.51E − 05 | |

| BP | Extracellular matrix organization | 13 | 1.92E − 04 | |

| CC | Extracellular exosome | 90 | 1.28E − 09 | |

| CC | Intermediate filament | 11 | 2.26E − 05 | |

| CC | Cytoplasm | 122 | 3.98E − 05 | |

| CC | Proteinaceous extracellular matrix | 16 | 5.65E − 05 | |

| CC | Basolateral plasma membrane | 13 | 5.98E − 05 | |

| MF | Structural molecule activity | 17 | 8.93E − 06 | |

| MF | Calcium ion binding | 27 | 4.52E − 04 | |

| MF | Protein homodimerization activity | 26 | 1.31E − 03 | |

| MF | 2′-5′-oligoadenylate synthetase activity | 3 | 1.83E − 03 | |

| MF | Fibronectin binding | 4 | 1.06E − 02 | |

|

| ||||

| KEGG pathway | ||||

| hsa05200 | Pathways in cancer | 18 | 5.47E − 04 | |

| hsa04550 | Signaling pathways regulating pluripotency of stem cells | 8 | 1.22E − 02 | |

| hsa05166 | HTLV-I infection | 11 | 1.56E − 02 | |

| hsa04512 | ECM-receptor interaction | 6 | 1.91E − 02 | |

| hsa05230 | Central carbon metabolism in cancer | 5 | 2.68E − 02 | |

Note: top five terms were selected according to P value. Abbreviation: DEGs: differentially expressed genes; GO: gene ontology; BP: biological process; CC: cellular component; MF: molecular function; HTLV-I: human T lymphocyte virus-I; ECM: extracellular matrix.

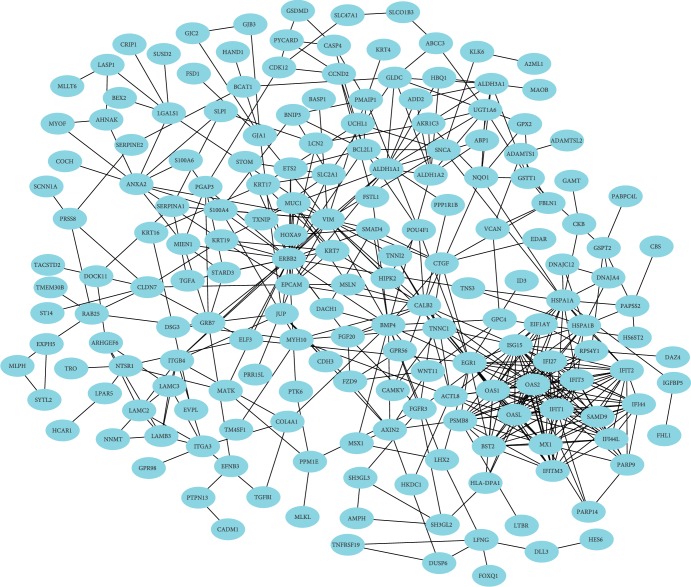

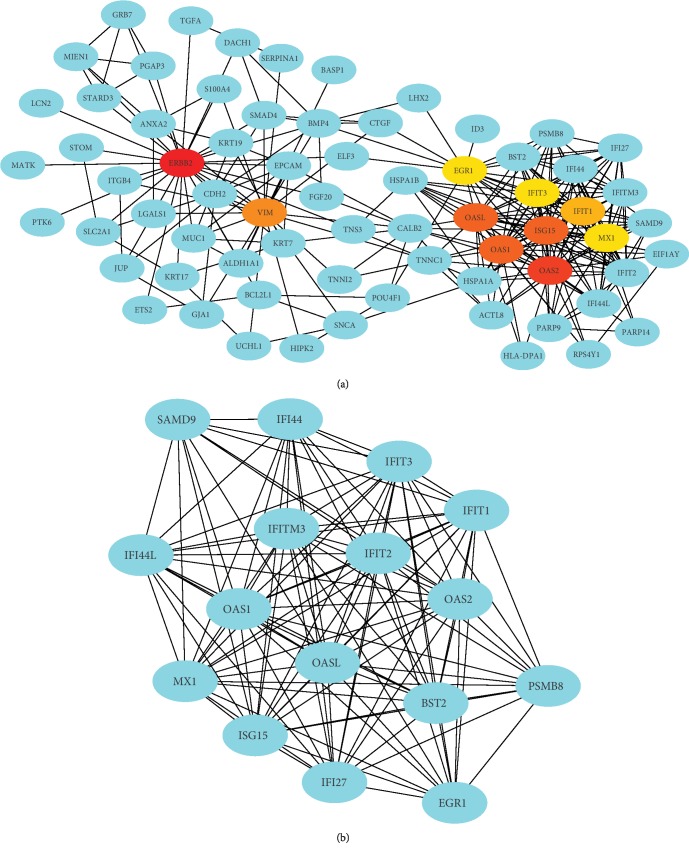

3.3. Construction of the PPI Network and Module Identification

The PPI network of the DEGs was constructed with 186 nodes and 480 edges by using the STRING database (Figure 1). Degrees ≥ 13 was set as the cutoff criterion. The top 16 genes were ERBB2, OAS2, OASL, ISG15, OAS1, VIM, IFIT1, IFIT2, IFIT3, MX1, EGR1, IFI27, IFI44L, IFITM3, IFI44, and BST2 (Figure 2(a) and Table 2). Subsequently, a significant module with an MCODE score ≥ 10 was selected; this module had 16 nodes and 111 edges, and the included genes were PSMB8, OAS2, OASL, ISG15, OAS1, IFIT1, IFIT2, IFIT3, MX1, EGR1, IFI27, IFI44L, IFITM3, IFI44, BST2, and SAMD9 (Figure 2(b) and Table 2). Thus, 18 genes were identified as hub genes.

Figure 1.

PPI network of the DEGs. Abbreviation: DEGs: differentially expressed genes.

Figure 2.

The genes identified by degree (a) and MCODE score (b) in the PPI network.

Table 2.

The hub genes in the PPI network.

| Gene | Regulation | Degree | MCODE scores |

|---|---|---|---|

| ERBB2 | Down | 29 | — |

| OAS2 | Down | 24 | 11.54 |

| OASL | Down | 23 | 11.54 |

| ISG15 | Down | 23 | 11.54 |

| OAS1 | Down | 23 | 11.54 |

| VIM | Up | 21 | — |

| IFIT1 | Down | 19 | 11.54 |

| IFIT2 | Down | 18 | 11.54 |

| IFIT3 | Down | 18 | 11.54 |

| MX1 | Down | 18 | 11.54 |

| EGR1 | Down | 18 | 12.00 |

| IFI27 | Down | 14 | 11.54 |

| IFI44L | Down | 14 | 12.00 |

| IFITM3 | Down | 14 | 11.54 |

| IFI44 | Down | 14 | 12.00 |

| BST2 | Down | 14 | 11.54 |

| PSMB8 | Down | — | 12.00 |

| SAMD9 | Down | — | 10.00 |

3.4. mRNA Expression and Survival Analysis

UALCAN database was used to analyze the expression levels of the 18 hub genes. Compared with normal samples, primary gastric cancer samples had higher expression of ERBB2, PSMB8, IFI44, IFI44L, IFIT2, IFIT3, ISG15, OAS1, BST2, IFIT1, IFITM3, MX1, and OAS2. The expression of EGR1 was lower in primary gastric cancer samples than in normal samples. However, no significant difference in VIM, OASL, SAMD9, or IFI27 expression was observed between primary gastric cancer samples and normal samples ().

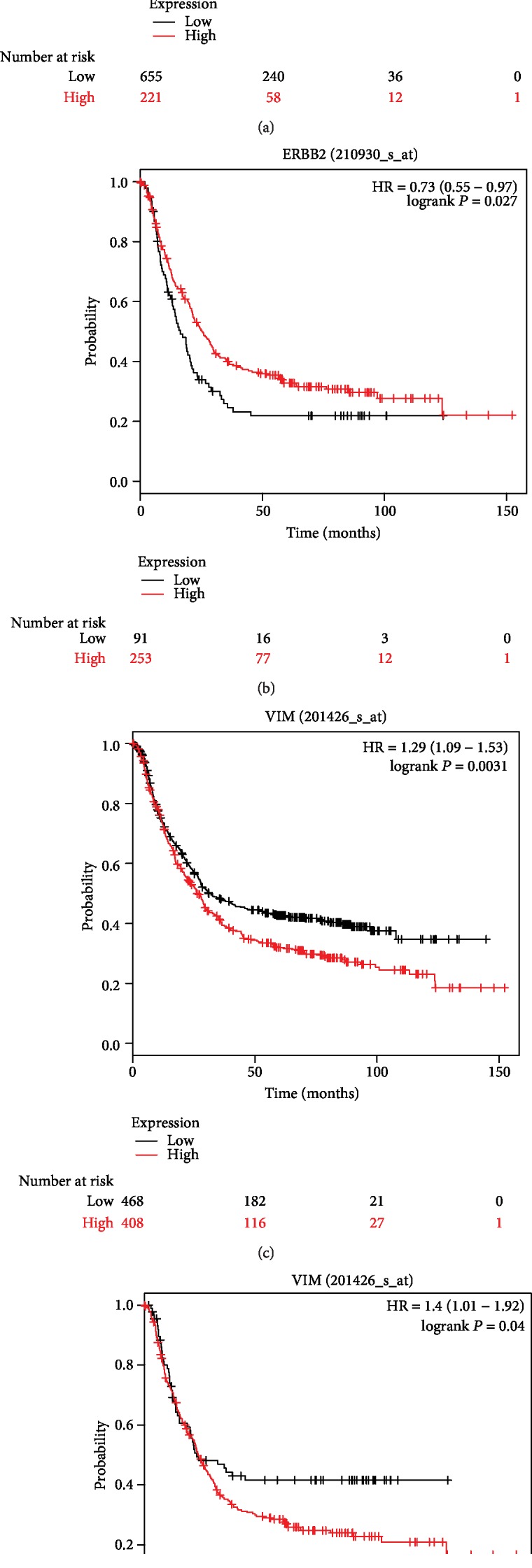

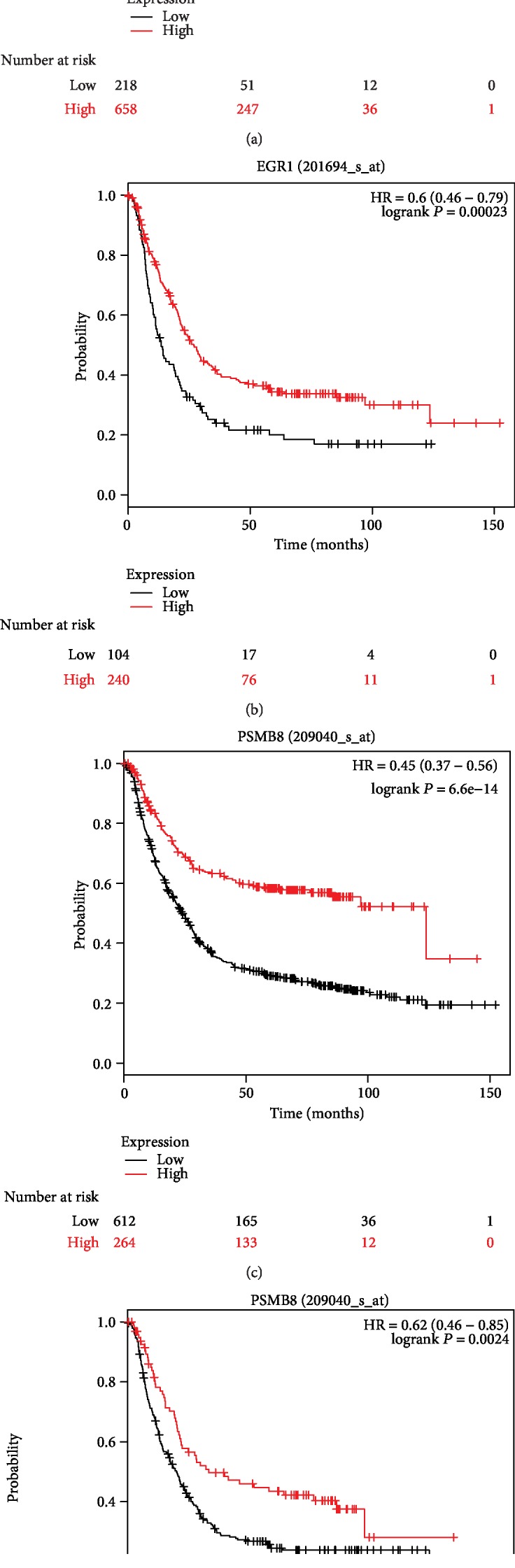

Kaplan-Meier plotter was used to predict the prognostic value of the 18 hub genes. For all gastric cancer cases, our results showed that high ERBB2 expression was associated with the worse overall survival of GC patients, VIM, IFI44, IFIT2, and MX1 showed similar associations (P < 0.05) (Figures 3(a) and 3(c) and Table 3). Additionally, low EGR1 expression was associated with the poorer overall survival of GC patients, and similar associations were found for PSMB8, ASMD9, BST2, IFI27, and IFIT1 (P < 0.05) (Figures 4(a) and 4(c) and Table 3). For HER2-gastric cancer, the high expression of ERBB2, VIM, or IFI44 was associated with worse overall survival (P < 0.05) (Table 3). In addition, the low expression of PSMB8, IFI44L, IFIT3, ISG15, OAS1, SAMD9, BST2, IFI27, IFIT1, or OAS2 was associated with the poorer overall survival of HER2-GC patients (P < 0.05) (Table 3). However, the expression of EGR1, IFIT2, OASL, IFITM3, and MX1 was not associated with the overall survival of HER2-GC patients. For HER2+ gastric cancer, the high expression of VIM, IFI44, IFI44L, IFIT2, IFIT3, ISG15, OAS1, or OASL was associated with worse overall survival (P < 0.05) (Figure 3(d) and Table 3). In addition, the low expression of ERBB2, EGR1, or PSMB8 was associated with the poorer overall survival of HER2+ GC patients (P < 0.05) (Figures 3(b), 4(b), and 4(d) and Table 3). However, the expression of ASMD9, BST2, IFI27, IFIT1, IFITM3, MX1, and OAS2 was not associated with the overall survival of HER2+ GC patients (Table 3).

Figure 3.

Kaplan-Meier curves depicting the overall survival of all patients with gastric cancer (GC) (a) or HER2-positive (HER2+) gastric cancer (b) with high or low expression of ERBB2 or VIM ((c) GC, (d) HER2+ GC).

Table 3.

Overall survival analysis based on the expression of the hub genes.

| Gene name | ID | OS (all) | OS (HER2-) | OS (HER2+) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) | P value | HR (95% CI) | P value | HR (95% CI) | P value | ||

| ERBB2 | 210930_s_at | 1.37 (1.14-1.65) | 0.00088 | 1.33 (1.06-1.66) | 0.013 | 0.73 (0.55-0.97) | 0.027 |

| VIM | 201426_s_at | 1.29 (1.09-1.53) | 0.0031 | 1.52 (1.21-1.9) | 0.00027 | 1.4 (1.01-1.92) | 0.04 |

| EGR1 | 201694_s_at | 0.63 (0.52-0.76) | 8.5E − 07 | 0.78 (0.61-1) | 0.052 | 0.6 (0.46-0.79) | 0.00023 |

| PSMB8 | 209040_s_at | 0.45 (0.37-0.56) | 6.6E − 14 | 0.39 (0.3-0.5) | 1.7E − 13 | 0.62 (0.46-0.85) | 0.0024 |

| IFI44 | 214059_at | 1.46 (1.22-1.74) | 0.000028 | 1.39 (1.1-1.75) | 0.0056 | 1.67 (1.28-2.19) | 0.00015 |

| IFI44L | 204439_at | 0.85 (0.71-1.03) | 0.1 | 0.75 (0.58-0.98) | 0.037 | 1.59 (1.16-2.19) | 0.0037 |

| IFIT2 | 217502_at | 1.26 (1.04-1.53) | 0.018 | 0.84 (0.67-1.05) | 0.12 | 1.7 (1.24-2.33) | 0.00075 |

| IFIT3 | 204747_at | 1.14 (0.95-1.36) | 0.16 | 0.75 (0.59-0.95) | 0.017 | 1.54 (1.15-2.07) | 0.0037 |

| ISG15 | 205483_s_at | 0.86 (0.71-1.03) | 0.094 | 0.73 (0.56-0.93) | 0.012 | 1.5 (1.1-2.05) | 0.01 |

| OAS1 | 202869_at | 1.15 (0.97-1.37) | 0.1 | 0.79 (0.63-0.99) | 0.039 | 1.39 (1.07-1.8) | 0.013 |

| OASL | 210797_s_at | 1.16 (0.98-1.37) | 0.09 | 0.84 (0.67-1.05) | 0.12 | 1.41 (1.04-1.92) | 0.028 |

| SAMD9 | 219691_at | 0.73 (0.61-0.88) | 0.00065 | 0.57 (0.44-0.74) | 0.00002 | 1.23 (0.94-1.6) | 0.14 |

| BST2 | 201641_at | 0.7 (0.58-0.85) | 0.00027 | 0.55 (0.42-0.7) | 1.9E − 06 | 1.28 (0.94-1.73) | 0.12 |

| IFI27 | 202411_at | 0.7 (0.59-0.84) | 0.000096 | 0.58 (0.46-0.73) | 1.8E − 06 | 0.85 (0.63-1.13) | 0.26 |

| IFIT1 | 203153_at | 0.73 (0.61-0.87) | 0.00061 | 0.63 (0.49-0.81) | 0.00025 | 1.23 (0.95-1.6) | 0.12 |

| IFITM3 | 212203x_at | 1.09 (0.91-1.29) | 0.36 | 0.89 (0.71-1.12) | 0.32 | 1.27 (0.96-1.69) | 0.096 |

| MX1 | 202086_at | 1.27 (1.05-1.54) | 0.015 | 1.15 (0.9-1.47) | 0.26 | 1.32 (0.99-1.76) | 0.056 |

| OAS2 | 204972_at | 0.91 (0.77-1.08) | 0.3 | 0.77 (0.61-0.96) | 0.021 | 1.25 (0.93-1.67) | 0.13 |

Abbreviation: OS: overall survival; HER2-: human epidermal growth factor receptor-2 negative; HER2+: human epidermal growth factor receptor-2 positive.

Figure 4.

Kaplan-Meier curves depicting the overall survival of all patients with gastric cancer (GC) (a) or HER2-positive (HER2+) gastric cancer (b) with high or low expression of EGR1 or PSMB8 ((c) GC, (d) HER2+ GC).

We also analyzed the prognostic value of the expression of the 18 hub genes in gastric cancer with different clinicopathological characteristics, including gender, stage, differentiation, and treatment. As shown in , not all the hub genes had the prognostic value in gastric cancer with different parameters, but some had prognostic value in gastric cancer with specific clinicopathological characteristics. For example, the expression of VIM had prognostic value in almost all categories of gastric cancer. The expression of PSMB8, IFIT2, and IFIT1 had prognostic value in gastric cancer at different stages.

4. Discussion

In this study, a total of 327 DEGs were screened, including 128 upregulated genes and 199 downregulated genes. Eighteen genes were identified as hub genes, including one upregulated gene (VIM) and seventeen downregulated genes (ERBB2, PSMB8, OAS2, OASL, ISG15, OAS1, IFIT1, IFIT2, IFIT3, MX1, EGR1, IFI27, IFI44L, IFITM3, IFI44, BST2, and SAMD9). However, survival analysis based on the expression of these genes indicated that only one overexpressed gene (VIM) and three downregulated genes (ERBB2, EGR1, and PSMB8) were significantly associated with the poorer overall survival of HER2+ GC patients.

The data showed that the overexpression of ERBB2 (or HER2) was associated with the worse overall survival of GC patients. Some studies have confirmed that ERBB2 positivity is correlated with a worse prognosis [8, 9], but others have found no relationship between ERBB2 status and prognosis [15, 16]. Therefore, the relationship between ERBB2 status and the prognosis of GC patients remains controversial. However, ERBB2 was found to be downregulated in trastuzumab-resistant cells in the present study, and low ERBB2 expression was associated with a poorer prognosis of HER2+ GC patients. Interestingly, HER2 loss was observed in GC patients treated with trastuzumab in the clinic [17]. This phenomenon indicates that ERBB2 may play an important role in promoting resistance to trastuzumab. The present study found that the overexpression of VIM (vimentin) was correlated with a poorer prognosis of all GC patients, including HER2-GC patients and HER2+ GC patients. Importantly, high VIM expression was associated with a poorer prognosis of almost all categories of GC patients. VIM expression is required for epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) [18]. Some studies have indicated that VIM overexpression is associated with a poorer prognosis among GC patients [19, 20]; this finding is consistent with our results and indicates that VIM may be involved in the development of trastuzumab resistance. The roles of proteasome subunit beta type-8 (PSMB8) and EGR1 in trastuzumab-resistant gastric cancer are controversial. We found that low expression of PSMB8 and EGR1 was associated with a poorer prognosis in all GC patients, including HER2-GC patients and HER2+ GC patients. However, the expression level of PSMB8 was higher in gastric cancer patients than in control patients. A previous study found that increased PSMB8 expression was associated with a lower survival rate of GC patients [21]. Similarly, increased expression of EGR1 was found to be significantly correlated with the depth of invasion and poorer survival of GC patients [22, 23]. Therefore, the roles of PSMB8 and EGR1 in trastuzumab-resistant gastric cancer need to be further investigated. More importantly, many drugs that target ERBB2, including lapatinib [24], trastuzumab [25], and pertuzumab [26], have been investigated. In addition, the ToGA trial confirmed that trastuzumab markedly improves the outcome of HER2+ gastric cancer patients [10]. Moreover, inhibitors of PSMB8 [27] or VIM [28] have been investigated. Carfilzomib, a novel, irreversible proteasome inhibitor, was shown to have potent activity against preclinical models of multiple myeloma [27]. Phenethyl isothiocyanate has been evaluated in trials studying the prevention and treatment of leukemia, lung cancer, tobacco use disorder, and lymphoproliferative disorders [28]. Together, ERBB2, VIM, and PSMB8 may be effective targets in gastric cancer, but more experimental investigations and clinical trials are needed.

IFI44, IFI44L, IFIT2, IFIT3, ISG15, OAS1, and OASL were identified in the subnetwork module. All of these genes are interferon- (IFN-) stimulated genes (ISGs) [29], which mediate the antiviral action of interferon. The interferon-induced protein 44 (IFI44) and interferon-induced protein 44-like (IFI44L) genes belong to the IFI44 family [30]. A previous study found that overexpression of IFI44L decreased doxorubicin chemoresistance and was associated with the better survival of hepatocellular carcinoma patients [31]. The IFN-induced protein with tetratricopeptide repeats (IFITs) family (including IFIT1, IFIT2, IFIT3/4, and IFIT5) is among hundreds of ISGs [32, 33]. Studies have shown that IFIT2 depletion induces cell migration and is associated with poor prognosis in patients with oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC) [34, 35]. Similarly, decreased IFIT2 expression predicted poor therapeutic outcomes of GC patients [36]. However, a previous study found that high IFIT3 expression could enhance the chemotherapeutic resistance of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) cells and was independently associated with the poor survival of PDAC patients [37].

Another previous study demonstrated that interferon-stimulated gene 15 (ISG15) downregulation could enhance cisplatin resistance via the DNA damage/repair pathway in A549/DDP cells [38]. However, ISG15 was found to be overexpressed in breast carcinoma, and ISG15 overexpression was associated with an unfavourable prognosis [39]. OAS1 and OASL belong to the 2′,5′-oligoadenylate synthetase (2-5OAS) gene family [40]. Many ISGs, including the OASL gene, have been tested for their antiviral specificity [41]. A previous study showed that OASL gene upregulation is involved in the inhibition of lung cancer cell proliferation and apoptosis [42]. Therefore, we propose that ISGs may play an important role in promoting GC resistance to trastuzumab, but the roles of these genes are controversial and need to be further investigated.

EBV plays an important role in gastric carcinogenesis [4, 5]. EBV latent membrane protein (LMP1) and latent membrane protein 2A (LMP2A) regulate the expression of the hub gene EGR1 [43, 44]. LMP2A has been found to suppress the expression of HER2 via the TWIST/YB-1 axis in EBV-associated gastric carcinoma [45]. Importantly, EBV and HER2 may exhibit crosstalk during human gastric carcinogenesis [46]. Interestingly, LMP1 can establish an antiviral state via the induction of ISGs, including OAS [47]. The EBV microRNA BART16 suppresses type I IFN signaling [48]. Thus, EBV may play a key role in gastric carcinogenesis, including in trastuzumab-acquired resistance, by regulating some of the identified hub genes or ISGs.

5. Conclusions

In summary, the current study identified genes related to acquired trastuzumab resistance in gastric cancer and analyzed their prognostic value. We found that four hub genes, including ERBB2, VIM, EGR1, and PSMB8, may participate in the development of chemoresistance to trastuzumab. However, the data in the present study were obtained by bioinformatics analysis, and the findings remain to be confirmed by further investigations. Therefore, more experiments are required to ascertain the clinical value of the identified genes as biomarkers and the underlying mechanism.

Acknowledgments

We thank all the doctors in our department for their help with patient care so that we had sufficient time to conduct this study.

Data Availability

The data used to support the findings of this study are included within the article and the supplementary information files.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no potential conflicts of interest.

Authors' Contributions

Guangda Yang, Liumeng Jian, and Xiangan Lin contributed equally to this work.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1: the expression levels of ERBB2 (a), VIM (b), EGR1 (c), PSMB8 (d), IFI44 (e), IFI44L (f), IFIT2 (g), IFIT3 (h), ISG15 (i), OAS1 (j), OASL (k), SAMD9 (l), BST2 (m), IFI27 (n), IFIT1 (o), IFITM3 (p), MX1 (q), and OAS2 (r) in gastric cancer (UALCAN database). Red represents primary gastric cancer and blue represents normal samples. Table S1: survival analyses of the hub genes in gastric cancer with different parameters.

References

- 1.Bray F., Ferlay J., Soerjomataram I., Siegel R. L., Torre L. A., Jemal A. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians. 2018;68(6):394–424. doi: 10.3322/caac.21492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.den Hoed C. M., Kuipers E. J. Gastric cancer: how can we reduce the incidence of this disease? Current Gastroenterology Reports. 2016;18(7):p. 34. doi: 10.1007/s11894-016-0506-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gao L., Michel A., Weck M. N., Arndt V., Pawlita M., Brenner H. Helicobacter pylori infection and gastric cancer risk: evaluation of 15 H. pylori proteins determined by novel multiplex serology. Cancer Research. 2009;69(15):6164–6170. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-0596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Akiba S., Koriyama C., Herrera-Goepfert R., Eizuru Y. Epstein-Barr virus associated gastric carcinoma: epidemiological and clinicopathological features. Cancer Science. 2008;99(2):195–201. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2007.00674.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen X., Chen H., Castro F. A., Hu J. K., Brenner H. Epstein–Barr virus infection and gastric cancer: a systematic review. Medicine. 2015;94(20, article e792) doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000000792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baniak N., Senger J.-L., Ahmed S., Kanthan S. C., Kanthan R. Gastric biomarkers: a global review. World Journal of Surgical Oncology. 2016;14(1):p. 212. doi: 10.1186/s12957-016-0969-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boku N. HER2-positive gastric cancer. Gastric Cancer. 2014;17(1):1–12. doi: 10.1007/s10120-013-0252-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Geng Y., Chen X., Qiu J., et al. Human epidermal growth factor receptor-2 expression in primary and metastatic gastric cancer. International Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2014;19(2):303–311. doi: 10.1007/s10147-013-0542-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bayrak M., Olmez O. F., Kurt E., et al. Prognostic significance of c-erbB2 overexpression in patients with metastatic gastric cancer. Clinical and Translational Oncology. 2013;15(4):307–312. doi: 10.1007/s12094-012-0921-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bang Y. J., van Cutsem E., Feyereislova A., et al. Trastuzumab in combination with chemotherapy versus chemotherapy alone for treatment of HER2-positive advanced gastric or gastro-oesophageal junction cancer (ToGA): a phase 3, open-label, randomised controlled trial. The Lancet. 2010;376(9742):687–697. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61121-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nahta R., Esteva F. J. HER2 therapy: molecular mechanisms of trastuzumab resistance. Breast Cancer Research. 2006;8(6):p. 215. doi: 10.1186/bcr1612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Piro G., Carbone C., Cataldo I., et al. An FGFR3 autocrine loop sustains acquired resistance to trastuzumab in gastric Cancer patients. Clinical Cancer Research. 2016;22(24):6164–6175. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-16-0178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chandrashekar D. S., Bashel B., Balasubramanya S., et al. UALCAN: a portal for facilitating tumor subgroup gene expression and survival analyses. Neoplasia. 2017;19(8):649–658. doi: 10.1016/j.neo.2017.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nagy Á., Lánczky A., Menyhárt O., Győrffy B. Validation of miRNA prognostic power in hepatocellular carcinoma using expression data of independent datasets. Scientific Reports. 2018;8(1, article 9227) doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-27521-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Janjigian Y. Y., Werner D., Pauligk C., et al. Prognosis of metastatic gastric and gastroesophageal junction cancer by HER2 status: a European and USA international collaborative analysis. Annals of Oncology. 2012;23(10):2656–2662. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mds104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Matsubara J., Yamada Y., Hirashima Y., et al. Impact of insulin-like growth factor type 1 receptor, epidermal growth factor receptor, and HER2 expressions on outcomes of patients with gastric cancer. Clinical Cancer Research. 2008;14(10):3022–3029. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-1898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pietrantonio F., Caporale M., Morano F., et al. HER2 loss in HER2-positive gastric or gastroesophageal cancer after trastuzumab therapy: implication for further clinical research. International Journal of Cancer. 2016;139(12):2859–2864. doi: 10.1002/ijc.30408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Richardson A. M., Havel L. S., Koyen A. E., et al. Vimentin is required for lung adenocarcinoma metastasis via heterotypic tumor cell-cancer-associated fibroblast interactions during collective invasion. Clinical Cancer Research. 2018;24(2):420–432. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-17-1776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Iwatsuki M., Mimori K., Fukagawa T., et al. The clinical significance of vimentin-expressing gastric cancer cells in bone marrow. Annals of Surgical Oncology. 2010;17(9):2526–2533. doi: 10.1245/s10434-010-1041-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Utsunomiya T., Yao T., Masuda K., Tsuneyoshi M. Vimentin-positive adenocarcinomas of the stomach: co-expression of vimentin and cytokeratin. Histopathology. 1996;29(6):507–516. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2559.1996.d01-538.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kwon C. H., Park H. J., Choi Y. R., et al. PSMB8 and PBK as potential gastric cancer subtype-specific biomarkers associated with prognosis. Oncotarget. 2016;7(16):21454–21468. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.7411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sun T., Tian H., Feng Y.-G., Zhu Y.-Q., Zhang W.-Q. Egr-1 promotes cell proliferation and invasion by increasing β-catenin expression in gastric cancer. Digestive Diseases and Sciences. 2012;58 doi: 10.1007/s10620-012-2356-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Myung E., Park Y. L., Kim N., et al. Expression of early growth response-1 in human gastric cancer and its relationship with tumor cell behaviors and prognosis. Pathology - Research and Practice. 2013;209(11):692–699. doi: 10.1016/j.prp.2013.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Johnston S. R., Leary A. Lapatinib: a novel EGFR/HER2 tyrosine kinase inhibitor for cancer. Drugs Today. 2006;42(7):441–453. doi: 10.1358/dot.2006.42.7.985637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Treish I., Schwartz R., Lindley C. Pharmacology and therapeutic use of trastuzumab in breast cancer. American Journal of Health-System Pharmacy. 2000;57(22):2063–2076. doi: 10.1093/ajhp/57.22.2063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Franklin M. C., Carey K. D., Vajdos F. F., Leahy D. J., de Vos A. M., Sliwkowski M. X. Insights into ErbB signaling from the structure of the ErbB2-pertuzumab complex. Cancer Cell. 2004;5(4):317–328. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(04)00083-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kuhn D. J., Chen Q., Voorhees P. M., et al. Potent activity of carfilzomib, a novel, irreversible inhibitor of the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway, against preclinical models of multiple myeloma. Blood. 2007;110(9):3281–3290. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-01-065888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mi L., Hood B. L., Stewart N. A., et al. Identification of potential protein targets of isothiocyanates by proteomics. Chemical Research in Toxicology. 2011;24(10):1735–1743. doi: 10.1021/tx2002806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hertzog P., Forster S., Samarajiwa S. Systems biology of interferon responses. Journal of Interferon & Cytokine Research. 2011;31(1):5–11. doi: 10.1089/jir.2010.0126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.McDowell I. C., Modak T. H., Lane C. E., Gomez-Chiarri M. Multi-species protein similarity clustering reveals novel expanded immune gene families in the eastern oyster Crassostrea virginica. Fish & Shellfish Immunology. 2016;53:13–23. doi: 10.1016/j.fsi.2016.03.157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Huang W.-C., Tung S.-L., Chen Y.-L., Chen P.-M., Chu P.-Y. IFI44L is a novel tumor suppressor in human hepatocellular carcinoma affecting cancer stemness, metastasis, and drug resistance via regulating met/Src signaling pathway. BMC Cancer. 2018;18(1):p. 609. doi: 10.1186/s12885-018-4529-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhou X., Michal J. J., Zhang L., et al. Interferon induced IFIT family genes in host antiviral defense. International Journal of Biological Sciences. 2013;9(2):200–208. doi: 10.7150/ijbs.5613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wacher C., Muller M., Hofer M. J., et al. Coordinated regulation and widespread cellular expression of interferon-stimulated genes (ISG) ISG-49, ISG-54, and ISG-56 in the central nervous system after infection with distinct viruses. Journal of Virology. 2006;81(2):860–871. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01167-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lai K. C., Liu C. J., Chang K. W., Lee T. C. Depleting IFIT2 mediates atypical PKC signaling to enhance the migration and metastatic activity of oral squamous cell carcinoma cells. Oncogene. 2013;32(32):3686–3697. doi: 10.1038/onc.2012.384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lai K. C., Chang K. W., Liu C. J., Kao S. Y., Lee T. C. IFN-induced protein with tetratricopeptide repeats 2 inhibits migration activity and increases survival of oral squamous cell carcinoma. Molecular Cancer Research. 2008;6(9):1431–1439. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-08-0141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chen L., Zhai W., Zheng X., et al. Decreased IFIT2 expression promotes gastric cancer progression and predicts poor prognosis of the patients. Cellular Physiology and Biochemistry. 2018;45(1):15–25. doi: 10.1159/000486219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhao Y., Altendorf-Hofmann A., Pozios I., et al. Elevated interferon-induced protein with tetratricopeptide repeats 3 (IFIT3) is a poor prognostic marker in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Journal of Cancer Research and Clinical Oncology. 2017;143(6, article 2351):1061–1068. doi: 10.1007/s00432-017-2351-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Huo Y., Zong Z., Wang Q., Zhang Z., Deng H. ISG15 silencing increases cisplatin resistance via activating p53-mediated cell DNA repair. Oncotarget. 2017;8(64):107452–107461. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.22488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bektas N., Noetzel E., Veeck J., et al. The ubiquitin-like molecule interferon-stimulated gene 15 (ISG15) is a potential prognostic marker in human breast cancer. Breast Cancer Research. 2008;10(4, article R58) doi: 10.1186/bcr2117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kakuta S., Shibata S., Iwakura Y. Genomic structure of the mouse 2′,5′-oligoadenylate synthetase gene family. Journal of Interferon & Cytokine Research. 2002;22(9):981–993. doi: 10.1089/10799900260286696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schoggins J. W., Wilson S. J., Panis M., et al. A diverse range of gene products are effectors of the type I interferon antiviral response. Nature. 2011;472(7344):481–485. doi: 10.1038/nature09907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lv J., Wang L., Shen H., Wang X. Regulatory roles of OASL in lung cancer cell sensitivity to Actinidia chinensis planch root extract (acRoots) Cell Biology and Toxicology. 2018;34(3):207–218. doi: 10.1007/s10565-018-9422-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Vockerodt M., Wei W., Nagy E., et al. Suppression of the LMP2A target gene, EGR-1, protects Hodgkin’s lymphoma cells from entry to the EBV lytic cycle. The Journal of Pathology. 2013;230(4):399–409. doi: 10.1002/path.4198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kim J. H., Kim W. S., Kang J. H., Lim H. Y., Ko Y. H., Park C. Egr-1, a new downstream molecule of Epstein-Barr virus latent membrane protein 1. FEBS Letters. 2007;581(4):623–628. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2007.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhang Y., Zhao X., Tan C., et al. Epstein-Barr virus latent membrane protein 2A suppresses the expression of HER2 via a pathway involving TWIST and YB-1 in Epstein-Barr virus-associated gastric carcinomas. Oncotarget. 2015;6(1):207–220. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.2702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cyprian F. S., al-Antary N., al Moustafa A.-E. HER-2/Epstein-Barr virus crosstalk in human gastric carcinogenesis: a novel concept of oncogene/oncovirus interaction. Cell Adhesion & Migration. 2017;12(1):1–4. doi: 10.1080/19336918.2017.1330244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhang J., Das S. C., Kotalik C., Pattnaik A. K., Zhang L. The latent membrane protein 1 of Epstein-Barr virus establishes an antiviral state via induction of interferon-stimulated genes. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2004;279(44):46335–46342. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M403966200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hooykaas M. J. G., van Gent M., Soppe J. A., et al. EBV microRNA BART16 suppresses type I IFN signaling. Journal of Immunology. 2017;198(10):4062–4073. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1501605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1: the expression levels of ERBB2 (a), VIM (b), EGR1 (c), PSMB8 (d), IFI44 (e), IFI44L (f), IFIT2 (g), IFIT3 (h), ISG15 (i), OAS1 (j), OASL (k), SAMD9 (l), BST2 (m), IFI27 (n), IFIT1 (o), IFITM3 (p), MX1 (q), and OAS2 (r) in gastric cancer (UALCAN database). Red represents primary gastric cancer and blue represents normal samples. Table S1: survival analyses of the hub genes in gastric cancer with different parameters.

Data Availability Statement

The data used to support the findings of this study are included within the article and the supplementary information files.