Abstract

The success of cancer immunotherapy with immune checkpoint blockade (ICB) has demonstrated the importance of targeting a preexisting immune response in a broad spectrum of tumors. This is particularly novel and relevant for less immunogenic tumors, such as breast cancer (BC), where the efficacy of ICB was more evident in the triple-negative (TNBC) subtype, in earlier stages, and in association with chemotherapy. Tumors harboring homologous recombination DNA repair (HRR) deficiency (HRD) are supposed to have a higher number of mutations, hence a higher tumor mutational burden, which could potentially make them more sensitive to immunotherapy. However, the mechanisms involved in ICB sensitivity and patient selection are still yet to be defined in BC: whether the innate system could play a role and how the adaptive immunity could be linked with HRR pathways are the two key points of debate that we will discuss in this article. The aim of this review was to close the loop between what was found in clinical trial results so far, go back to laboratory theory and preclinical results and point out what needs to be clarified from now on.

Introduction

The success of cancer immunotherapy with immune checkpoint blockade (ICB) has increasingly demonstrated the importance of targeting the immune system in a broad spectrum of tumors [[1], [2], [3], [4]]. Not surprisingly, early studies showed that responses to ICB are most frequently observed in those tumors that are characterized by an extensive baseline immune infiltration [5]. Later on, a variety of novel biomarkers were shown to be associated with ICB benefit, such as the expression of programmed cell death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) by tumor cells or by immune cells [6], the presence of a high extent of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs), the expression of immune gene signatures, detection of other circulating biomarkers, such as the levels of lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) [7,8], and markers of systemic immune dysfunction such as the neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio [9].

Furthermore, one of the well-recognized predictive factors of response to ICB is the high number of somatic mutations, defined as tumor mutational burden (TMB) [10]. Tumors that harbor an impairment in the DNA damage repair (DDR) are characterized by an increase in the number of somatic mutations and a high TMB. Somatic mutations may lead to the transcription of altered proteins and some of them result in the formation of immunogenic neoantigens (neo-Ags) ([11,12]. Neo-Ags elicit the antitumoral immune response as they can be recognized by and activate antigen-specific T lymphocytes. Tumors with mismatch-repair (MMR) deficient status are known to present a dysfunctional DDR. Based on these considerations, Le et al. [13] tested the efficacy of pembrolizumab in patients with advanced MMR-deficient cancers across 12 different tumor types. Objective radiographic responses were observed in 53% of patients, and complete responses were achieved in 21% of patients. Responses were durable, with median progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS) still not reached. These results have led to the approval of ICB in MMR-deficient tumors by the United States (US) Food and Drug Administration (FDA) [13]. MMR-deficient status is known to be the hallmark of Lynch syndrome (LS), a familial clustering of colorectal and endometrial cancers. LS is caused by several germline mutations in MMR genes, resulting in a defective MMR and is inherited as dominant autosomal character [14].

LS is just a form of inherited cancer susceptibility; even if notoriously only about 5–10% of all cancers result directly from germline mutations, we can hypothesize that much about family cancer syndromes and cancer predisposition is still unknown. ICB can also be effective in hereditary tumors associated with other mechanisms of DDR, generating a high number of somatic mutations (consequently a high TMB). A recent study revealed that a positive family history of cancer was significantly associated with a better objective response rate (ORR), disease control rate (DCR), median time to treatment failure (TTF) and median OS in patients treated with ICB, raising the question whether this effect on hereditary tumors could also be seen in breast cancers (BC) associated with a defective DNA damage response [15]. In particular, the hereditary breast and ovarian cancer syndrome is associated with the presence of germline mutations in BRCA1 or BRCA2 genes [16]. BRCA1 and BRCA2 (BRCA1/2) act in the homologous recombination DNA repair (HRR) pathway, which is a mechanism aiming to repair double strand breaks (DBSs). Several other genes are involved in HRR and they could be also mutated in BC, such as PALB2. The impairment of HRR activity is known as HRR deficiency (HRD). HRD may drive tumorigenesis, increasing the number of tumor mutations and, potentially, the neo-Ag rate in BC [17]. Thus, HRD tumors may hold the biological prerequisites for eliciting neo-Ag–directed adaptive immune response. Based on these considerations, prospective clinical trials with anti–PD-1 for patients with germline BRCA1/2 mutations are currently ongoing [20].

ICB has already been used in BC, with interesting results. Nanda et al. [7] published the results of a phase Ib trial with the anti–PD-1, pembrolizumab, in a cohort of PD-L1 (>1%)–positive patients reporting an ORR of 18.5% with a median duration of response not reached. Results of the IMpassion130 phase III trial demonstrated the efficacy and safety of pembrolizumab plus chemotherapy in the PD-L1+ cohort of patients with metastatic TNBC, improving survival outcomes as compared with chemotherapy alone, becoming the new standard of care in this subgroup of patients [89].

Based on this consideration, it is crucial to better identify a subgroup of patients with BC that may benefit from ICB. In this context, it is worth of note that at least 50% of triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) harbor HRD and may be the ideal candidate for ICB treatment [18,19]. Indeed, all the mechanisms involved in ICB sensitivity are still unclear: apart from the known role played by the adaptive immunity (mainly by T cells) [9], it would be important to understand whether the innate immunity (i.e., macrophages, myeloid derived suppressor cells [MDSCs], natural killer [NK] cells, dendritic cells [DCs], etc) could play a role in the response to ICB or how the adaptive immunity could be linked with DDR pathways. These are some of the topics that we would like to discuss in this article.

In this work, we aim to close the loop between what was found in clinical trial results so far, go back to laboratory theory and preclinical results and point out what needs to be clarified from now on.

Homologous Recombination Repair Deficiency and Breast Cancer

HRD in Germline BRCA1/2-mutated and Sporadic BC

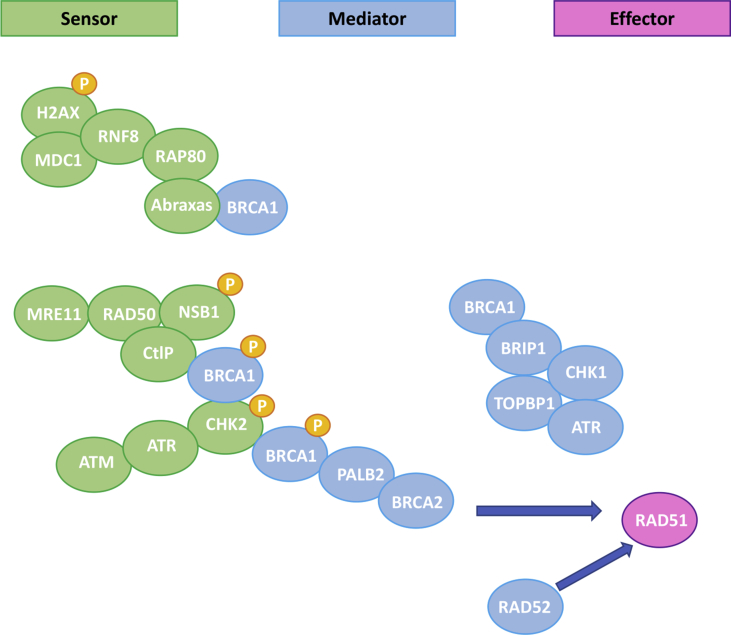

Among the numerous mechanisms that are involved in the repair of DNA damage, with the aim to preserve the integrity of genome information, the HRR pathway plays a key role in processing DSBs [1]. HRR is an accurate, error-free pathway that makes use of the sister chromatid as a template to repair the genomic sequence of the broken DNA ends [20]. Several steps are necessary to complete the HRR pathway; they are depicted in Figure 1 [21]. The final step of HRR involves a small nuclear protein called RAD51 that polymerizes around the single-stranded DNA to promote strand invasion into the sister chromatid to enable error-free repair (Figure 1) [22]. Breast tumors with HRD were first described in patients with germline BRCA1/2 (gBRCA1/2) mutations [23]. HRD attributable to gBRCA1/2 mutations represents approximately up to 4% and 22% of BC and patients with TNBC, respectively [16,24,25]. Furthermore, at least 40% of sporadic (namely non-gBRCA1/2 mutation carriers) TNBC are HRR-deficient because of: (1) somatic mutations in BRCA1 or BRCA2 genes, that is., sporadic mutations occurring in almost 29% of tumor cells in TNBC [19] or (2) genetic or epigenetic modifications that may inactivate other molecules involved in the HRR pathway [19,26].

Figure 1.

Homologous recombination repair pathway (adapted from De Picciotto et al.) [117]. Several proteins are involved, such as BRCA1 and BRCA2 that if mutated in the germline, are responsible for the hereditary breast and ovarian cancer syndrome (HBOCS). Almost 50% of triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) harbors a mutation in the genes involved in HRR pathway. HRR = homologous recombination repair pathway

Different Approaches to Identify HRD

Several preclinical and clinical data suggested that sporadic BRCA1/2 wild type (wt) tumors harboring HRD may also benefit from platinum chemotherapy and poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase inhibitor (PARPi) because they cannot repair the DNA damage induced by these treatments [[27], [28], [29], [30]]. For this reason, a major challenge is to identify HRR-deficient tumors beyond gBRCA1/2 mutations and several attempts have been made in clinical trials to validate tools able to reveal HRD. HRR-deficient tumors can be identified by point mutations in HRR genes using DNA sequencing panels, including the Myriad's BRACAnalysis CDx (FDA approved) [31]. These methods have been tested in preclinical studies, and they are currently being used in two trials as prospective recruitment strategy (NCT03367689 and NCT02401347) [27,32]. The major limitations of this method are the incapability to identify all the genes that are involved in the HRR pathway and to reveal reversion mutations that may restore the HRR functionality [33]. To overcome these issues, new assays have been introduced, that is, the "genomic scars" that can capture large genomic aberrations typically developed by HRD tumors, such as gBRCA1/2-mutated cells [[34], [35], [36], [37]]. These aberrations remain as a "tattoo" onto tumor DNA and can be identified by the "genomic scars". Two commercial genomic scar assays have been tested to identify tumors with HRD in clinical trials: (1) the "myChoice HRD" assay by Myriad and (2) the "FoundationFocus™ CDx BRCA LOH" from Foundation Medicine. These assays lack specificity, and none has been routinely included in clinical practice. In particular, the NOVA trial and ARIEL trials in ovarian cancer (OvC) showed that HRD status according to "myChoice HRD" assay by Myriad and the "FoundationFocus™ CDx BRCA LOH", respectively, could predict the magnitude of benefit derived from PARPi treatment but could not identify resistant tumors. A different approach consists of analyzing mutational signatures that are characteristic patterns left on the cancer genome by each mutational process: for example, the "signature 3" described by Alexandrov et al.[39] has been associated with HRD but still needs to be validated in clinical trials [38,40].

Prognostic and Predictive Role of HRD in BC

The prognostic and predictive role of HRD in BC has been extensively discussed by Pellegrino et al. [21] in a recent editorial. To summarize, in early-stage BC, HRD genomic scars have shown a high correlation with the response to DNA-damaging chemotherapy (i.e., platinum chemotherapy), but not with survival rates [19]. In the neoadjuvant setting, Telli et al. [41] retrospectively assessed the predictive value of the "myChoice HRD" assay in three single-arm trials testing platinum-based therapy [19]. Patients who were HRD-positive had a higher probability to achieve a complete pathological response or minimal residual disease (RCB 0-I) after platinum chemotherapy, even among BRCA1/2 wt tumors [19,41]. Moreover, the GeparSixto trial evaluated the benefit of the addition of carboplatin to anthracycline/taxane-based neoadjuvant chemotherapy in TNBC and analyzed the predictive and prognostic value of testing for HRD by the composite biomarker including germline/somatic BRCA1/2 mutations and the "myChoice" assay [19,41]. Among all patients with TNBC, addition of carboplatin resulted in a marked increment in pCR rates in HRD-positive tumors (from 33.9 to 63.5%, P = 0.001), and in HRD-negative tumors (from 20 to 29.6%, P = 0.399) [19,41]. No improvement in disease-free survival (DFS) with the administration of carboplatinum was observed according to the HRD status. Moreover, BRCA1/2-mutated tumors (either germline or somatic) are sensitive to PARPis, small molecules that interfere with the mechanisms of DNA repair by blocking single strand break repair and increasing DNA damage. PARPis induce the accumulation of DSBs that HRD cells cannot repair [34] thus possibly leading to a higher TMB and neo-Ag expression. The phase 3 randomized OlympiA trial showed that the PARPi olaparib increased the PFS compared with the standard of care in pretreated gBRCA1/2-mutated metastatic BC. The phase 3 randomized EMBRACA trial demonstrated the activity of the PARPi talazoparib in the same population with an increase in PFS of 3 months, compared with the standard of care. Based on these results, the PARPis olaparib and talazoparib have been approved by the European Medicines Agency (EMA) and by the FDA for patients with advanced BC and harboring gBRCA1/2 mutations who have been previously treated with chemotherapy [[42], [43], [44]]. In metastatic TNBC, the predictive role for response of Myriad's HRD test was not confirmed by the TNT study, a randomized phase 3 trial comparing the efficacy of 1st line carboplatin versus docetaxel in patients with advanced TNBC [45]. In this trial, the HRD test was performed on archival samples and these results could be partially explained by the fact that the genomic scars tested in the primary tumor may have lower prediction power for response in the advanced settings. It has been postulated that metastatic tumors may have restored the HRR function and thus may become resistant to platinum agents. Indeed, a current limitation of the genomic scar assays, to date, is the impossibility to capture tumor evolution processes, such as the restoration of the HRR function in response to therapy-selective pressure [35]. As an alternative option, a variety of studies suggests that it could be useful to incorporate functional biomarkers based on dynamic assays assessing the activity of the HRR pathway, such as the RAD51 assay [27,[46], [47], [48]]. In cells that experience DNA damage, the presence of RAD51 nuclear foci, in S-phase cycling cells, indicates a functional HRR pathway, whereas the absence of RAD51 foci, unveils HRD. Several preclinical and clinical data showed that the RAD51 assay could be performed in formalin-fixed and paraffin-embedded samples and its prognostic and predictive role is now under evaluation in retrospective trials [27,[46], [47], [48]].

Role of the Host Immune System in Breast Cancer: the Innate Immunity

The presence of tumor cells can elicit an antitumor or a protumor immune response from the host immune system. This response can be mediated by cells from both the innate and adaptive immunity and mostly differs in timing (fast versus slow) and in Ag recognition. Indeed, the innate immune response does not require Ag restriction by the human leukocyte antigen (HLA) complex to induce the recruitment of NK cells, monocytes/macrophages, DCs, and neutrophils. The innate immune response coadjuvates and integrates the adaptive immune response that rises against specific tumor Ags presented by the HLA molecules and that consists in T- and B-lymphocyte recruitment and activation.

Innate Immunity

NK cells

NK cells are a key component of the innate antitumor immune response as they can recognize and attack cells with absent/low expression of class I major histocompatibility complex (MHC-I), representing one of the mechanisms of tumor immune escape. NK cells derive from bone marrow and are large granular effector lymphocytes [49], classified according to the variable membrane expression of cluster of differentiation (CD)56 and of CD16, the low-affinity fragment crystallizable (Fc)-γ receptor [50]. CD56dimCD16+ NK cells represent about 90–95% of peripheral blood NK cells and they can release high quantities of perforin and granzymes. Their cytotoxic activity is enhanced by cells with high-activating ligands (i.e., MHC class I polypeptide–related sequence A [MIC-A] or MIC-B which are markers of stressed cells [51]) and absent/low class I MHC expression or by binding the Fc fragment of opsonizing antibodies (Abs) [49]. The latter mechanism explains one of the immune effects of monoclonal Abs used in the clinic (i.e., the anti–human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2) trastuzumab, whose benefit has been associated with high baseline immune infiltration [52,53]): the Ab-dependent cellular cytotoxicity (ADCC) [49]. CD56brightCD16−/low represent about 5–10% of peripheral blood NK cells [50]. They are poorly cytotoxic, but they can release several antitumor and chemoattractive cytokines, such as interferon (IFN)-γ, tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α, and granulocyte monocyte–colony stimulating factor (GM-CSF) [50]. Interestingly, both subtypes of mature NK cells can express PD-1 (and are classified as PD-1pos), thus being inactivated after binding to their ligand, PD-L1, that can be upregulated on epithelial, cancer, stromal, and immune cells [54,55].

Preclinical studies reveal that alloreactive NK cells are able to cure mice from 4T1 BC and that both NK and CD8+ T cells are required for an antitumor response in TNBC models [56]. Watkins-Schulz [56] demonstrated by immune cell depletion studies that NK cell and CD8+ T cells were both required for early antitumor function in a TNBC mouse model.

Further, it has been demonstrated that they could prevent the development of bone metastases. In vitro experiments reveal that human-derived BC cells expressing CD1d can be killed by a subset of NK cells (invariant NK T cells), suggesting a potentially effective immunotherapeutic approach to be explored in the future in patients with BC [57].

In humans, it was shown that IL-18 induced PD-1pos CD56dimCD16dim/- NK cells are immunosuppressive and associated with a worse prognosis in TNBC. Reduction in the serum levels of NK cells (rather than T and B lymphocytes) after radiotherapy was associated with a worse prognosis in early-stage BC, probably due to the release of damage-associated molecular patterns [58]. Anyway, the latter study was conducted only in 40 patients and the analysis of the lymphocytes subpopulation was conducted on peripheral blood samples instead of tissue biopsies. Based on these considerations, further studies are needed to confirm these results.

Macrophages

A number of studies suggests that tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) are involved in tumor progression and can confer resistance to anticancer treatments [59]. In BC, TAMs are derived from resident macrophages and from the recruitment of circulating monocytes [59]. The latter develop into nonpolarized (M0) macrophages following exposure to the monocyte colony–stimulating factor-1 (CSF-1). M0 macrophages eventually polarize under the influence of environmental signals into M1-like (antitumor) and M2-like macrophages (protumor) [59]. The type 1 helper T-cell (Th1) cytokines, such as interferon-gamma (IFN-γ) or tumor necrosis factor-alfa (TNF-α), induce a M1-like activation. M1-like macrophages can release proinflammatory cytokines (i.e., TNF-α and interleukin [IL]-2) and reactive nitrogen and oxygen intermediates [59]. The type 2 helper T-cell (Th2) cytokines such as IL-4, IL-10, and IL-13 lead to a M2-like polarization, and M2-like macrophages are associated with tumor angiogenesis and progression [59]. Of note, in BC most of TAMs have a M2-like phenotype [50]. In addition, the high density of CD68pos (a macrophage-associated marker) cells seems to be an unfavorable prognostic factor in primary BC [59]. CD68pos cells correlate with larger tumor size, higher tumor grade, lymph node metastasis, vascular invasion, hormone receptor negativity, HER2 overexpression and basal phenotype [60,61]. However, most of the studies failed to demonstrate that it represents an independent predictor of prognosis probably because it is a pan-macrophage marker and cannot distinguish TAM subpopulations [59]. To overcome this issue, CD163, a validated marker for protumor M2-like macrophages, was introduced and several data demonstrated that, in early-stage BC, CD163pos TAMs were strongly associated with adverse clinicopathological characteristics and were independently prognostic for worse DFS, BC specific survival (BCSS), or OS in both TNBC and HER2-positive BC [[61], [62], [63], [64], [65]].

HRD and Innate Immunity: the STING and RIG Pathways

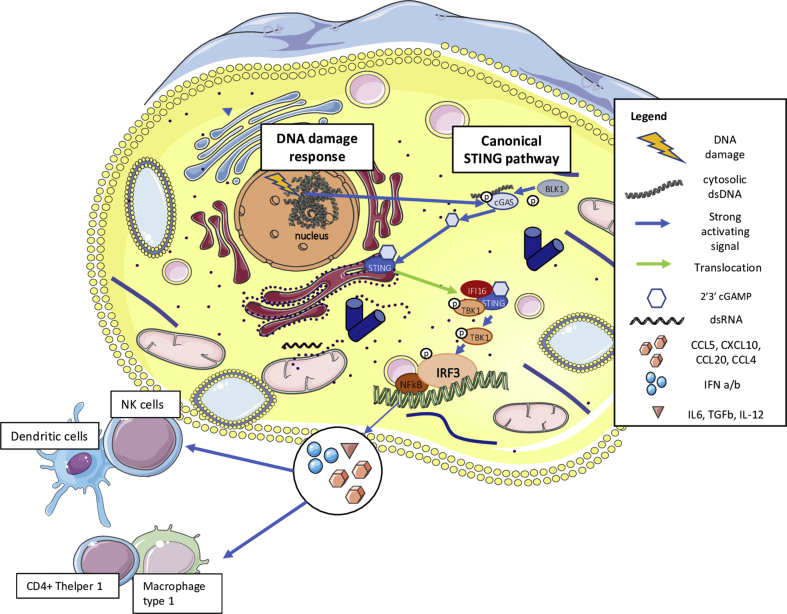

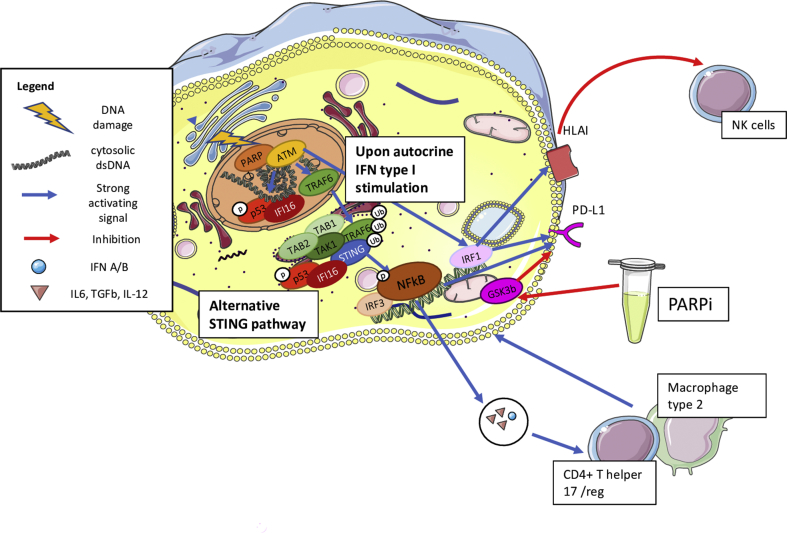

Several preclinical and clinical data suggest the importance of the innate immune system in the response to HRR-deficient tumors. Remarkably, an emerging role appears to be played by the stimulator of interferon genes (STING) pathway, primarily known as an innate immune pathway involved in the response to viral infections [66]. Elevated levels of basal DNA damage results in the increase of cytosolic DNA (cDNA) which induces an activation of cyclic GMP-AMP Synthase (cGAS) and, consequently, the translocation of STING from the endoplasmic reticulum to the nucleus (Figure 2) [67]. There, the STING leads to the transcription of several IFN type I–related genes by IRF3 activation [67], thus inducing the production of IFN type I and chemoattractive cytokines, that is, chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand 10 (CXCL10) and chemokine (C–C motif) ligand 5 (CCL5). This leads to NK cell, M1-like macrophage and both T and B-lymphocyte recruitment in an Ag-independent manner (Figure 2) [67]. Nonetheless, high levels of DNA damage also activate the so called "alternative STING pathway" by ATM-TRAF6, inducing the production of IL-6 and Transforming Growth Factor (TGF)-β generating the recruitment of protumor M2-like macrophages and regulatory T cells (Tregs) [67]. Furthermore, ATM-TRAF6 activates the transcription factor Nuclear Factor kB (NFkB) and induces tumor cell upregulation of PD-L1 that may elicit immune-escape (Figure 3) [66]. Besides this mechanism, IFN type I itself (secreted upon STING activation) is the main factor inducing transcription and expression of PD-L1. We and others recently showed that treatment with PARPi and platinum chemotherapy increases DNA damage and, consequently, enhances the STING pathway activation, inducing the recruitment of immune cells [66,[68], [69], [70]]. In particular, Pellegrino et al. [69] recently demonstrated that in HRR-deficient tumors, PARPi increases the percentage of micronuclei-positive cells, that is a marker of cytosolic DNA, resulting in a recruitment of innate and adaptive immune cells in both TNBC Patient-derived Xenografts (PDXs) and in a BRCA1-deleted transgenic mouse model. Furthermore, we demonstrated that olaparib upregulates PD-L1 on T lymphocytes in the HRR-deficient transgenic mouse. This observation has a great clinical potential application as the IMpassion130 trial demonstrated that the combination of atezolizumab and nab-paclitaxel improved the OS in TNBC tumors expressing PD-L1 on immune cells (IC). Indeed, in BC PD-L1 expression is almost found on immune cells (i.e., macrophages, NK cells, DCs and rarely by TILs) rather than tumor cells [6,17,71]. Furthermore, in the IMpassion130 PD-L1 expression on IC was found in around 40% of cases, whereas PD-L1 expression on tumor cells was observed in 9% of TNBC. In addition, 78% of cases that were PD-L1pos in tumor cells had also a positive staining in IC [6]. In this context, treatment of PARPi may sensitize PD-L1-negative HRR-deficient tumors to anti–PD-L1 treatment, paving the basis for promising combinations with PARPi and ICB targeting the PD-1/PD-L1 pathway [66,69,70].

Figure 2.

Canonical STING pathway activation. Elevated levels of basal DNA damage results in the increase of cytosolic DNA (cDNA) which induces an activation of cGAS and, consequently, the translocation of STING from the endoplasmic reticulum to the nucleus. There, STING pathway leads to the transcription of several IFN type I–related genes by IRF3 activation, thus inducing the production of IFN type I and chemoattractive cytokines, that is, chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand 10 (CXCL10) and chemokine (C–C motif) ligand 5 (CCL5). This leads to NK cell, M1-like macrophage and both T- and B-lymphocyte recruitment in an Ag-independent manner. STING = stimulator of interferon genes; cGAS = cyclic GMP-AMP synthase; IFN = interferon.

Figure 3.

Alternative STING pathway activation. High levels of DNA damage also activate the so called "alternative STING pathway" by ATM-TRAF6, inducing the production of IL-6 and transforming growth factor (TGF)-β generating the recruitment of protumor M2-like macrophages and regulatory T cells (Tregs). Furthermore, ATM-TRAF6 activates the transcription factor nuclear factor kB (NFkB) and induces tumor cell upregulation of PD-L1 that may elicit immune escape. Besides this mechanism, IFN type I itself (secreted upon STING activation) is the main factor inducing transcription and expression of PD-L1. STING = stimulator of interferon genes; PD-L1 = programmed cell death-ligand 1; IFN = interferon.

Role of the Host Immune System in Breast Cancer: the Adaptive Immunity

Adaptive Immunity

Tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes

TILs are mononuclear immune cells that are observed on hematoxylin and eosin (H&E)–stained tumor tissue sections. In BC they are mostly represented by T lymphocytes followed by B lymphocytes and cells from the innate immunity [72]. Their scoring on H&E slides can be performed by well-trained pathologists through a semiquantitative approach [73,74]. TILs can be classified as intratumoral (itTIL), lymphocytes localized in tumor nests having direct cell-to-cell contact, and stromal (sTIL), present in the stroma between tumor cells [75].

Indeed other semiquantitative, quantitative, and qualitative techniques, such as immunohistochemistry (IHC) and gene expression have been used to further investigate TIL composition and organization in tertiary lymphoid structures (TLS) in BC [71,[76], [77], [78], [79]]. Depending on the type and phenotype of the infiltrating immune cells, TILs can have an antitumor or protumor role [73]. An efficient antitumor immune response may be elicited by CD8+ cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTL), Th1, and NK cells, whereas Th2 and FoxP3+ Tregs have a predominant immunosuppressive effect. Plasma cells can have both antitumor and protumor activities depending on the protumor or antitumor balance of the tumor microenvironment (TME) [73]. A recent study revealed that immunoglobulins (Igs) produced by tumor-infiltrating B cells (TIL-B) are Ag-specific, linked with the presence of germinal centers inside BC-TLS, associated with an early memory B-cell maturation and with the presence of TLS, suggesting that these TIL-B are activated.

Prognostic and Predictive Role of TIL in BC

Despite having traditionally being considered nonimmunogenic, a number of studies revealed that BC can be characterized by a high expression of immune gene signatures and a high extent of TILs. This is particularly true for the TNBC and HER2-positive subtypes [53]. Notably, high TIL extent is associated with improved survival and with better responses to standard treatments, particularly in early-stage TNBC (reviewed in Refs. [53,80,81]). The finding, linking TIL extent and outcome, was consistent for either early and advanced stages of the disease, although TIL extent in metastases is usually lower [78,82].

TILs reflect a preexisting baseline antitumor immune response. So far, a variety of trials has been performed and is ongoing to evaluate the relationships between TIL and benefit from ICB in BC, particularly in TNBC, showing a positive association between TIL extent and response [78]. The potential value of TILs in TNBC has been widely investigated in patients with early-stage disease. For example, in the adjuvant setting, the first prospective-retrospective analysis was conducted in a subgroup of 256 patients with node-positive TNBC enrolled in the BIG-02-98 trial [83]. These data demonstrated a 15% (p = 0.025) and 17% (p = 0.023) relative reduction of risk of recurrence and a 17% (p = 0.1) and 27% (p = 0.035) relative reduction of risk of death for each 10% increase in sTIL and itTIL, respectively. The favorable prognostic role of TIL in TNBC was confirmed by the retrospective analysis of two phase III randomized trials (Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group 2197 and 1199) [84]. At a median follow-up of over 10 years, each 10% increase in sTIL was significantly associated with DFS (hazard ratio [HR] 0.84, p = 0.005) and OS (HR 0.79, p = 0.003). Furthermore, the meta-analysis by Carbognin et al. [85] estimated that, in the context of TNBC, each 10% increment of sTIL was significantly associated with an improvement in OS (HR 0.84, p < 0.0001). Recently, at last ESMO Congress 2019, a retrospective study of early-stage TNBC not treated with adjuvant chemotherapy, revealed the instrinsic prognostic role of TIL, strengthening the clinical significance of high baseline TIL infiltration in this BC subtype [118]. In the metastatic setting, few data are available concerning the prognostic and predictive role of TIL in TNBC. It has to be considered that a retrospective analysis suggested that the percentage of sTIL in secondary TNBC lesions was lower than in the primary tumors (p = 0.06) [86]. A preliminary analysis including 52 HER2-positive and 42 TNBC reported low sTIL level in tumor samples from metastases and a better prognosis in TNBC with high TIL (>10%) [87]. However, the role of TILs for advanced TNBC needs to be further investigated. Noteworthy, from a qualitative point of view, TILs are represented predominantly by activated memory T cells [74] and, apart from their extent, it is important to point out that the importance and clinical relevance of TIL composition and organization in TLS, are yet to be fully understood in BC in both early and advanced settings [76,88].

Enhance the Adaptive Immune Response in BC

Clinical Trial Results

In TNBC treatment, the hot topic is now to find new strategies to enhance the antitumoral immune response. Of note, recently the anti–PD-L1 atezolizumab has been approved as the first immunotherapeutic agent for the treatment of patients with PD-L1+ IC metastatic TNBC in the 1st line setting, in association with chemotherapy (nab-paclitaxel), following the impressive results obtained in the IMpassion130 trial [89]. This study demonstrated that atezolizumab plus nab-paclitaxel prolonged PFS in the entire TNBC group, particularly in the PD-L1–positive subgroup, suggesting that PD-L1 expression by IC represents an important biomarker for patient selection in TNBC [6]. These findings led to US FDA approval of PD-L1 expression assessed with the SP142 assay (cut-off >1% for positive IC) for the use of atezolizumab in metastatic TNBC. The KEYNOTE-522 trial recently demonstrated that the combination of pembrolizumab with neoadjuvant chemotherapy increased the pathologic Complete Response (pCR) rate in patients with TNBC, independently of the PD-L1 status [90].

Chemotherapy Enhances Tumor Immunogenicity

Moreover, it has to be considered that, besides the intended direct cytotoxic activity, chemotherapy itself may also affect tumor immunogenicity. Intriguing recent preclinical evidence reported that chemotherapeutic agents (including carboplatin, doxorubicin, gemcitabine, or paclitaxel), prompted immune evasion of TNBC cells by inducing the expression of "don't eat me signals", such as CD47, CD73, and PD-L1. Such mechanism seems to be regulated by the hypoxia-inducible factor 1α (HIF 1α), and it may sustain the rationale to combine ICB with chemotherapy in TNBC and explore the therapeutic potential of HIF inhibitors in this context [91]. Indeed, the KEYNOTE-119 trial showed that pembrolizumab alone did not improve PFS and OS compared with chemotherapy alone, except for patients with high PD-L1 expression (combined positive score (CPS) > 20) [92].

Thus, to improve the efficacy of ICB in BC, it is mandatory to better define the ideal candidates to these expensive and potentially toxic treatments and identify the ideal combination strategies, such as radiotherapy (RT) [93] or chemotherapy [119] or targeted therapies. One of the best predictors of benefit from single agent ICB was sTIL assessed on H&E tissue sections [[94], [95], [96]] and CD8+ TIL by IHC [95]. Remarkably, efforts are being performed to standardize TIL scoring on H&E tissue slides, not only in BC (primary tumors, metastases, and residual disease after neoadjuvant therapy) [97,98] but also in other solid tumors to render this biomarker more reproducibly assessable by pathologists [19,20].

HRD and Adaptive Immunity in Breast Cancer: TMB and TILs

BC is a tumor with a low versus intermediate TMB, if compared with melanoma and non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) [39]. However, BC subgroups with a higher TMB could be represented by TNBC [99] and gBRCA1/2-mutated tumors, similar to what was observed with microsatellite unstable high (MSI-H) cases in colorectal cancer [100]. It is worth of note that up to 25% of TNBC harbors a gBRCA1/2 mutation and at least 75% and 25% of gBRCA1-and gBRCA2-mutated tumors, respectively, are TNBC [101,102].

Indeed, it is thought that pathogenic gBRCA1/2 mutations could increase the likelihood of immunogenic somatic mutations (and consequently of neo-Ags), which are generated for the essential role played by BRCA in repairing DSBs [103]. Although BC has a relatively low number of nonsynonymous mutations compared with melanoma and NSCLC [39], a study of 560 breast tumor genomes found numerous somatic mutations [104] particularly in the 90 tumors with alterations in the BRCA1/2 genes. Further, the presence of gBRCA1 mutations was associated with TP53 mutations and a high sensitivity to DNA cross-linking agents [105]. Nolan et al. [106] also revealed that gBRCA1/2-mutated TNBC had a higher TMB with respect to the gBRCA1/2 wt counterpart. In terms of benefit from ICB, no associations with TMB was shown in BC [107].

However, it is important to highlight that the lack of a clear relationship between TILs and TMB in all BC subtypes in an analysis performed in the The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) BC series was previously shown [99].

A pooled analysis of five clinical trials, including patients with TNBC undergoing neoadjuvant platinum-based treatment was conducted to evaluate the association between TILs, HRD status, and somatic BRCA1/2 mutational status [41]. TIL infiltration rate and HRD status independently predicted benefit from neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Noteworthy, there were differences in the extent of sTIL and itTIL neither between HRR-deficient and HRR-proficient tumors nor between BRCA1/2-mutated and wt tumors [41]. These results suggest that TIL presence is not driven by mutations (neo-Ags) induced by the HRD status. Furthermore, in the GeparSixto trial, lymphocyte-predominant breast cancer (LPBC), that is, tumors with a sTIL or itTIL infiltration higher than 60% was equally distributed between HRR-deficient and HRR-proficient samples [108,109]. These results are in line with data from a retrospective study by Solinas et al. [17], showing that the extent of TIL, TLS, the expression of PD-1 and PD-L1 is similar between gBRCA1/2-mutated and wt high-risk TNBC. However, the gBRCA1/2-mutated group presented a smaller number of TILneg tumors (<10% stTIL) compared with wt samples, suggesting that gBRCA1/2-mutated tumors may have a higher TIL set point than their wt counterparts [106]. However, when comparing sporadic versus gBRCA1/2-mutated TNBC from the TCGA, Nolan et al. [106] found that the extent of TIL resulted higher in the latter group. As such, the relationship between TIL and HRD represents an unresolved issue because different studies measured these variables in different ways, and considering that functional assays have not been studied as of yet, that is RAD51, to better define and identify specific subgroups of patients.

Indeed, in a recent study where somatic aberrations, TME characteristic, and survival of patients with tumors from different origins were considered, highly mutated BRCA1/2 tumors clustered in the IFN-γ dominant (C2) immune subtype [110]. This BRCA1/2-mutated phenotype was characterized by a better prognosis; the highest extent of the lymphocytic infiltrate, a CD8+ T-cell–associated signature; the highest M1-like macrophage content; the highest proliferation signature; the lowest TAMs/lymphocyte ratio; the highest Th1/Th2 ratio; the highest M1/M2-like macrophage polarization; the greatest T-cell receptor (TCR) diversity [111].

Therapeutic Implications in BC: ICB and PARPi Combinations

As already mentioned, the PARPis olaparib and talazoparib have been recently approved by EMA and FDA for patients with advanced BC and gBRCA1/2 mutations who have been previously treated with chemotherapy. Nonetheless, PARPi-induced hypoxia has been shown to selectively upregulate the expression of PD-L1 by protumor myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs) [112] and by HIF-related mechanisms [91]. Thus, PARPi primary/acquired resistance is supposed to be associated with the development of immuneevasion mechanisms. Furthermore, PARPi may also upregulate PD-L1 expression in tumor cells, by inhibiting GSK3b and activating the STING pathway (Figure 3) [113]. For this reason, there can be synergy between therapeutic strategies against PARP (through PARPi) and PD-L1 (through ICB) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Ongoing Trials Testing PARP-Inhibitors in Combination With Immune Checkpoint Blockade in Breast Cancer

| Reference | Drug(s) | Phase | Breast cancer subtype | Selection (HRD or BRCA status or others) | Status |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NCT02657889 (TOPACIO) | Niraparib and pembrolizumab | I/II | TNBC | Selection will not be restricted based on these variables | Active, not recruiting |

| NCT03307785 | Niraparib, TSR-022 (anti-TIM3), bevacizumab, and platinum based-doublet chemotherapy plus TSR-042 (anti-PD-1) | I | Advanced solid tumors | Selection will not be restricted based on these variables | Recruiting |

| NCT03565991 | Talazoparib and avelumab | II | Locally advanced or metastatic solid tumors with a BRCA or ATM defect | BRCA or ATM gene defect | Recruiting |

| NCT03330405 | Talazoparib and avelumab | I/II | TNBC; HR + BC DDR Defect + Assay | BRCA or ATM gene defect | Recruiting |

| NCT03061188 | Veliparib and nivolumab | I/Ib | Advanced solid tumors | Genomically profiled tumors (BRCA1 pathway, Fanconi's proteins pathway, and RAD51 pathway) | Recruiting |

| NCT02734004 (MEDIOLA) | Olaparib and durvalumab | I/II | BRCAm HER2-negative BC | Cohorts distinguished based on gBRCA; mBRCA, HRD | Recruiting |

| NCT03842228 | Olaparib, durvalumab, and copanlisib (PI3K-inhibitor) | I | Advanced solid tumors | Molecularly selected solid tumors: germline or somatic mutations of DDR genes (BRCA1/2, RAD51 B/C/D, PALB2, etc) | Not yet recruiting |

| NCT03544125 | Olaparib and durvalumab | I | TNBC | Molecular profiling will be performed in pretreatment biopsies | Recruiting |

| NCT03167619 (DORA) | Olaparib and durvalumab | II | TNBC | Selection was not restricted based on these variables | Recruiting |

| NCT02849496 | Olapariband atezolizumab | II | Non-HER2-positive BC | HRD | Recruiting |

| NCT03594396 | Olaparib and durvalumab | I/II | TNBC or Low ER+ | Selection was not restricted based on these variables | Recruiting |

| NCT02484404 | Olaparib, cediranib and durvalumab | I/II | TNBC | gBRCAm | Recruiting |

| NCT03801369 | Olaparib and durvalumab | II | TNBC | Patients with gBRCAm TNBC will be excluded | Recruiting |

| NCT03740893 | Olaparib, durvalumab, AZD6738 | II | TNBC | Selection was not restricted based on these variables | Not yet recruiting |

| NCT03772561 | Olaparib and durvalumab, AZD5363 (MEDIPAC) |

I | Advanced or metastatic solid tumor malignancies | NA | Recruiting |

| NCT01042379 | Olaparib and durvalumab | II | Breast cancer | Selection will be done based on biomarker signature | Recruiting |

| NCT03101280 | Rucaparib and atezolizumab | I | TNBC | tBRCA mutation [tBCRA(mut)] or BRCA-like molecular signature [tBRCA (wt)/LOH(high)] | Recruiting |

TNBC = triple-negative breast cancer; PARP = poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase; NA = not applicable.

Several clinical studies have evaluated the activity of PARPi with agents targeting the PD-1/PD-L1 axis. For example, a phase I study evaluated olaparib in association with the anti–PD-L1 durvalumab (MEDI4736) in patients with metastatic TNBC and ovarian cancer and demonstrated that this combination was safe and active (NCT02484404) [114]. In the MEDIOLA study (NCT02734004), whose latest results were presented at the 2019 ESMO Congress, olaparib was administered in combination with durvalumab in patients with HER2-negative metastatic BC with gBRCA1/2 mutations [115] (setting: 1st-3rd line of treatment). Eleven and fourteen patients had BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations, respectively; 13 patients had a hormone receptor–positive disease. Median duration of response was 9.2 months, ORR equaled 63%, median PFS was 8.2 months and median OS was 21.5 months; these results are comparable with the olaparib efficacy, as monotherapy, reported in the OlympiAD trial [42]. Responses were seen regardless of hormone receptor status, BRCA1/2 mutation type, or prior platinum-based chemotherapy.

The same combination has been tested in different stages of TNBC: in the neoadjuvant setting (NCT03594396) and in the metastatic setting (the DORA trial, NCT03167619; NCT03544125; NCT03801369). Interestingly, in the NCT03740893 trial, olaparib and durvalumab have been delivered with an ataxia telangiectasia and Rad3–related (ATR) inhibitor (AZD6738) to test the possible synergy with other DDR agents. The safety of olaparib with different anti–PD-L1 Abs is under investigation, for example, in the NCT02849496 trial.

In addition, the anti–PD-1 pembrolizumab is being evaluated with niraparib in advanced TNBC or recurrent ovarian cancer in a phase I/II study (KEYNOTE-162, NCT02657889). The TOPACIO study [116] enrolled 47 patients with metastatic TNBC (1st-3rd line) with a platinum resistant disease. Highest responses were seen in tumor (t)BRCA1/2 mutants, but also in tHRR mutants and in other patients lacking these mutations (either tBRCA1/2 or tHRR). ORR reached 21%, similar to the results observed in TNBC populations included in previous studies and the clinical benefit (i.e., complete response or partial response or stable disease) equaled around 40% (10 with tBRCA1/2 mutations; 8 with no tBRCA1/2 mutations) [8].

The safety of rucaparib in combination with the anti–PD-L1 atezolizumab and of talazoparib in combination with the anti–PD-L1 avelumab is now being tested in two phase Ib trials (NCT03101280 and the NCT03330405, respectively).

Conclusions

Deficiencies in DNA repair may not only modulate tumor immunogenicity and promote immune evasion but also provide rationale for synergism with ICB-based immunotherapy. The genomic instability, with consequent DNA fragments and enhanced somatic mutations, may contribute to the activation of inflammasome pathways, such as the expression of PD-L1 and the generation of potentially immunogenic neo-Ags. Such biological dynamics may be enhanced by the therapeutic PARP inhibition that can also contribute to PD-L1 expression by tumor cells. These promising premises have prompted several clinical trials currently investigating synergistic combinations of PARPi with ICB in BC. Preliminary results of the combination trials showed similar response rate compared with PARPi alone but encouraging median duration of response suggests that a better selection of patients will be crucial to improve patients’ outcomes. In this sense, clinical data are expected to be paralleled by important translational research efforts. It would be crucial to better elucidate the modulatory activities of PARPi on tumor immunogenicity and on circulating immune effectors, even considering the possible integration of conventional chemotherapy. As HRD may be the ideal candidate to select patients who may benefit from combination of PARPi and ICB, further studies are needed to validate novel functional biomarkers in the clinic.

Acknowledgments

B.P. was supported by European Society of Medical Oncology (ESMO) with the aid of a grant from Roche. Any views, opinions, findings, conclusions, or recommendations expressed in this material are those solely of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of ESMO or Roche.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tranon.2019.10.010.

Contributor Information

B. Pellegrino, Email: benedettapellegrino89@gmail.com.

C. Solinas, Email: czsolinas@gmail.com.

Conflict of interest

A.M. reports grants and personal fees from Roche, grants and personal fees from Novartis, personal fees from Macrogenics, grants and personal fees from Pfizer, personal fees from Lilly, grants and personal fees from EISAI, outside the submitted work. V.S. declares a noncommercial research agreement with AstraZeneca and Tesaro. D.S. was in part supported by grants from AIRC IG 20259 and FPRC ONLUS 5 × 1000 MS 2015.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Bianco A., Malapelle U., Rocco D., Perrotta F., Mazzarella G. Targeting immune checkpoints in non small cell lung cancer. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2018;40:46–50. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2018.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Castellano T., Moore K.N., Holman L.L. An Overview of Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors in Gynecologic Cancers. Clin Ther. 2018;40:372–388. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2018.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Marciscano A.E., Madan R.A. Targeting the Tumor Microenvironment with Immunotherapy for Genitourinary Malignancies. Curr Treat Options Oncol. 2018;19:16. doi: 10.1007/s11864-018-0523-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Marconcini R., Spagnolo F., Stucci L.S., Ribero S., Marra E., De Rosa F., Picasso V., Di Guardo L., Cimminiello C., Cavalieri S. Current status and perspectives in immunotherapy for metastatic melanoma. Oncotarget. 2018;9:12452–12470. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.23746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tumeh P.C., Harview C.L., Yearley J.H., Shintaku I.P., Taylor E.J.M., Robert L., Chmielowski B., Spasic M., Henry G., Ciobanu V. PD-1 blockade induces responses by inhibiting adaptive immune resistance. Nature. 2014;515:568–571. doi: 10.1038/nature13954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Emens L, Loi S, Rugo H. Impassion130: Efficacy in immune biomarker subgroups from the global, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase III study of atezolizumab plus nab paclitaxel in patients with treatment-naive, locally advanced or metastatic triple negative breast . Clin Cancer Res

- 7.Nanda R., Chow L.Q.M., Dees E.C., Berger R., Gupta S., Geva R., Pusztai L., Pathiraja K., Aktan G., Cheng J.D. Pembrolizumab in Patients With Advanced Triple-Negative Breast Cancer: Phase Ib KEYNOTE-012 Study. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34:2460–2467. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.64.8931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Solinas C., Gombos A., Latifyan S., Piccart-Gebhart M., Kok M., Buisseret L. Targeting immune checkpoints in breast cancer: an update of early results. ESMO Open. 2017;2 doi: 10.1136/esmoopen-2017-000255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Blank C., Haanen J., Ribas A., Schumacher T. The “cancer immunogram. Science. 2016;352(80-):658–660. doi: 10.1126/science.aaf2834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rizvi N.A., Hellmann M.D., Snyder A., Kvistborg P., Makarov V., Havel J.J., Lee W., Yuan J., Wong P., Ho T.S. Mutational landscape determines sensitivity to PD-1 blockade in non–small cell lung cancer. Science. 2015;348(80-):124–128. doi: 10.1126/science.aaa1348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Le D.T., Durham J.N., Smith K.N., Wang H., Bartlett B.R., Aulakh L.K., Lu S., Kemberling H., Wilt C., Luber B.S. Mismatch repair deficiency predicts response of solid tumors to PD-1 blockade. Science. 2017;357:409–413. doi: 10.1126/science.aan6733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ciombor K.K., Goldberg R.M. Hypermutated Tumors and Immune Checkpoint Inhibition. Drugs. 2018;78:155–162. doi: 10.1007/s40265-018-0863-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Le D.T., Uram J.N., Wang H., Bartlett B.R., Kemberling H., Eyring A.D., Skora A.D., Luber B.S., Azad N.S., Laheru D. PD-1 Blockade in Tumors with Mismatch-Repair Deficiency. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:2509–2520. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1500596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pino M.S., Mino-Kenudson M., Wildemore B.M., Ganguly A., Batten J., Sperduti I., Iafrate A.J., Chung D.C. Deficient DNA mismatch repair is common in Lynch syndrome-associated colorectal adenomas. J Mol Diagn. 2009;11:238–247. doi: 10.2353/jmoldx.2009.080142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cortellini A., Bersanelli M., Buti S., Gambale E., Atzori F., Zoratto F., Parisi A., Brocco D., Pireddu A., Cannita K. Family history of cancer as surrogate predictor for immunotherapy with anti-PD1/PD-L1 agents: preliminary report of the FAMI-L1 study. Immunotherapy. 2018;10:643–655. doi: 10.2217/imt-2017-0167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Musolino A., Cavanna L., Boggiani D., Zamagni C., Frassoldati A., Caldara A., Rocca A., Gori S., Piacentini F., Berardi R. Abstract P1-14-05: Phase II study of eribulin in combination with gemcitabine for the treatment of patients with locally advanced or metastatic triple negative breast cancer (ERIGE Trial). Clinical and pharmacogenetic results on behalf of the Gruppo Oncol. Cancer Res. 2019;79 doi: 10.1016/j.esmoop.2020.100019. P1-14-05 LP-P1-14–05. https://doi.org/10.1158/1538-7445.SABCS18-P1-14-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Solinas C., Marcoux D., Garaud S., Vitória J.R., Van den Eynden G., de Wind A., De Silva P., Boisson A., Craciun L., Larsimont D. BRCA gene mutations do not shape the extent and organization of tumor infiltrating lymphocytes in triple negative breast cancer. Cancer Lett. 2019;450:88–97. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2019.02.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Telli M., McMillan A., Ford J., Richardson A., Silver D., Isakoff S., Kaklamani V., Gradishar W., Stearns V., Connolly R. Abstract P3-07-12: Homologous recombination deficiency (HRD) as a predictive biomarker of response to neoadjuvant platinum-based therapy in patients with triple negative breast cancer (TNBC): A pooled analysis. Cancer Res. 2016;76 P3-07-12-P3-07–12. https://doi.org/10.1158/1538-7445.SABCS15-P3-07-12. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Loibl S., Weber K.E., Timms K.M., Elkin E.P., Hahnen E., Fasching P.A., Lederer B., Denkert C., Schneeweiss A., Braun S. Survival analysis of carboplatin added to an anthracycline/taxane-based neoadjuvant chemotherapy and HRD score as predictor of response – final results from GeparSixto. Ann Oncol. 2018 doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdy460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ciccia A., Elledge S.J. The DNA Damage Response: Making It Safe to Play with Knives. Mol Cell. 2011;40:179–204. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.09.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pellegrino B, Mateo J, Serra V, Balmaña J. Controversies in Oncology: homologous recombination repair deficiency (HRD) is useful for treatment decision making? ESMO Open [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 22.Murai J., Huang S.N., Das B.B., Renaud A., Zhang Y., Doroshow J.H., Ji J., Takeda S., Pommier Y. Trapping of PARP1 and PARP2 by Clinical PARP Inhibitors. Cancer Res. 2012;72:5588–5599. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-2753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hoppe M.M., Sundar R., Tan D.S.P., Jeyasekharan A.D. Biomarkers for Homologous Recombination Deficiency in Cancer. JNCI J Natl Cancer Inst. 2018;110:704–713. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djy085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Baretta Z., Mocellin S., Goldin E., Olopade O.I., Huo D. Effect of BRCA germline mutations on breast cancer prognosis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore) 2016;95 doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000004975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Akashi-Tanaka S., Watanabe C., Takamaru T., Kuwayama T., Ikeda M., Ohyama H., Mori M., Yoshida R., Hashimoto R., Terumasa S. BRCAness Predicts Resistance to Taxane-Containing Regimens in Triple Negative Breast Cancer During Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy. Clin Breast Cancer. 2015;15:80–85. doi: 10.1016/j.clbc.2014.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.The Cancer Genome Atlas Network Integrated Genomic Analyses of Ovarian Carcinoma. Nature. 2011;474:609–615. doi: 10.1038/nature10166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Castroviejo-Bermejo M., Cruz C., Llop-Guevara A., Gutiérrez-Enríquez S., Ducy M., Ibrahim Y.H., Gris-Oliver A., Pellegrino B., Bruna A., Guzmán M. A RAD51 assay feasible in routine tumor samples calls PARP inhibitor response beyond BRCA mutation. EMBO Mol Med. 2018 doi: 10.15252/emmm.201809172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Coleman R.L., Oza A.M., Lorusso D., Aghajanian A.O., Dean A.C., Scambia G., Leary A., Holloway R.W., Gancedo M.A., Fong P.C. Rucaparib maintenance treatment for recurrent ovarian carcinoma after response to platinum therapy (ARIEL3): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2018;390:1949–1961. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32440-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Swisher E.M., Lin K.K., Oza A.M., Scott C.L., Giordano H., Sun J., Konecny G.E., Coleman R.L., Tinker A.V., O’Malley D.M. Rucaparib in relapsed, platinum-sensitive high-grade ovarian carcinoma (ARIEL2 Part 1): an international, multicentre, open-label, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2017;18:75–87. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(16)30559-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mirza M.R., Monk B.J., Herrstedt J., Oza A.M., Mahner S., Redondo A., Fabbro M., Ledermann J.A., Lorusso D., Vergote I. Niraparib Maintenance Therapy in Platinum-Sensitive, Recurrent Ovarian Cancer. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:2154–2164. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1611310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Polak P., Kim J., Braunstein L.Z., Karlic R., Haradhavala N.J., Tiao G., Rosebrock D., Livitz D., Kübler K., Mouw K.W. A mutational signature reveals alterations underlying deficient homologous recombination repair in breast cancer. Nat Genet. 2017;49:1476–1486. doi: 10.1038/ng.3934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.www.clinicaltrials.gov

- 33.Ganesan S. Tumor Suppressor Tolerance: Reversion Mutations in BRCA1 and BRCA2 and Resistance to PARP Inhibitors and Platinum. JCO Precis Oncol. 2018:1–4. doi: 10.1200/PO.18.00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Connor M.J.O. Targeting the DNA Damage Response in Cancer. Mol Cell. 2015;60:547–560. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2015.10.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Watkins J.A., Irshad S., Grigoriadis A., Tutt A.N.J. Genomic scars as biomarkers of homologous recombination deficiency and drug response in breast and ovarian cancers. Breast Cancer Res. 2014:16. doi: 10.1186/bcr3670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hodgson D.R., Dougherty B., Lai Z., Grinsted L., Spencer S., O’Connor M.J., Ho T.W., Robertson J.D., Lanchbury J., Timms K. Candidate biomarkers of PARP inhibitor sensitivity in ovarian cancer beyond the BRCA genes. Eur J Cancer. 2015;51:S90. doi: 10.1038/s41416-018-0274-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Abkevich V., Timms K.M., Hennessy B.T., Potter J., Carey M.S., Meyer L.A., Smith-Mccune K., Broaddus R., Lu K.H., Chen J. Patterns of genomic loss of heterozygosity predict homologous recombination repair defects in epithelial ovarian cancer. Br J Cancer. 2012;107:1776–1782. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2012.451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Helleday T., Eshtad S., Nik-Zainal S. Mechanisms underlying mutational signatures in human cancers. Nat Rev Genet. 2014;15:585–598. doi: 10.1038/nrg3729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Alexandrov L.B., Nik-Zainal S., Wedge D.C., Aparicio S.A., Behjati S., Biankin A.V., Bignell G.R., Bolli N., Borg A., Borresen-Dale A.L. Signatures of mutational processes in human cancer. Nature. 2013;500:415–421. doi: 10.1038/nature12477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Peng G., Chun-Jen Lin C., Mo W., Dai H., Park Y.-Y., Kim S.M., Peng Y., Mo Q., Siwko S., Hu R. Genome-wide transcriptome profiling of homologous recombination DNA repair. Nat Commun. 2014;5:3361. doi: 10.1038/ncomms4361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Telli M.L., Timms K.M., Reid J., Hennessy B., Mills G.B., Jensen K.C., Szallasi Z., Barry W.T., Winer E.P., Tung N.M. Homologous Recombination Deficiency (HRD) Score Predicts Response to Platinum-Containing Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy in Patients with Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2016;22:3764–3773. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-15-2477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Robson M., Im S.-A., Senkus E.E., Xu B., Domchek S.M., Masuda N., Delaloge S., Li W., Tung N., Armstrong A. Olaparib for Metastatic Breast Cancer in Patients with a Germline BRCA Mutation. N Engl J Med. 2017 doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1706450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Litton J.K., Rugo H.S., Ettl J., Hurvitz S.A., Gonçalves A., Lee K.-H., Fehrenbacher L., Yerushalmi R., Mina L.A., Martin M. Talazoparib in Patients with Advanced Breast Cancer and a Germline BRCA Mutation. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:753–763. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1802905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.https://www.ema.europa.eu/medicines/human/

- 45.Tutt A., Tovey H., Cheang M.C.U., Kernaghan S., Kilburn L., Gazinska P., Owen J., Abraham J., Barrett S., Barrett-Lee P. Carboplatin in BRCA1/2-mutated and triple-negative breast cancer BRCAness subgroups: The TNT Trial. Nat Med. 2018;24:628–637. doi: 10.1038/s41591-018-0009-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cruz C., Castroviejo-Bermejo M., Gutiérrez-Enriquez S., Llop-Guevara A., Ibrahim Y., Gris-Oliver A., Bonache S., Morencho B., Bruna A. RAD51 foci as a functional biomarker of homologous recombination repair and PARP inhibitor resistance in germline BRCA mutated breast cancer. Ann Oncol. 2018;29:1203–1210. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdy099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Naipal K.A.T., Verkaik N.S., Ameziane N. 2014. Functional Ex Vivo Assay to Select Homologous Recombination − Deficient Breast Tumors for PARP Inhibitor Treatment Functional Ex Vivo Assay to Select Homologous Recombination – De fi cient Breast Tumors for PARP; pp. 4816–4826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Graeser M., Mccarthy A., Lord C.J. 2011. A Marker of Homologous Recombination Predicts Pathologic Complete Response to Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy in Primary Breast Cancer. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cooper M.A., Fehniger T.A., Caligiuri M.A. The biology of human natural killer-cell subsets. Trends Immunol. 2001;22:633–640. doi: 10.1016/s1471-4906(01)02060-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Albini A., Bruno A., Noonan D.M., Mortara L. Contribution to tumor angiogenesis from innate immune cells within the tumor microenvironment: Implications for immunotherapy. Front Immunol. 2018:9. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.00527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Campbell K.S., Hasegawa J. Natural killer cell biology: An update and future directions. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2013;132:536–544. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2013.07.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Loi S., Michiels S., Salgado R., Sirtaine N., Jose V., Fumagalli D., Kellokumpu-Lehtinen P.-L.L., Bono P., Kataja V., Desmedt C. Tumor infiltrating lymphocytes are prognostic in triple negative breast cancer and predictive for trastuzumab benefit in early breast cancer: results from the FinHER trial. Ann Oncol. 2014;25:1544–1550. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdu112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Solinas C., Ceppi M., Lambertini M., Scartozzi M., Buisseret L., Garaud S., Fumagalli D., de Azambuja E., Salgado R., Sotiriou C. Tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes in patients with HER2-positive breast cancer treated with neoadjuvant chemotherapy plus trastuzumab, lapatinib or their combination: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Cancer Treat Rev. 2017;57:8–15. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2017.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Della Chiesa M., Pesce S., Muccio L., Carlomagno S., Sivori S., Moretta A., Marcenaro E. Features of Memory-Like and PD-1(+) Human NK Cell Subsets. Front Immunol. 2016;7:351. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2016.00351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Del Zotto G., Marcenaro E., Vacca P., Sivori S., Pende D., Della Chiesa M., Moretta F., Ingegnere T., Mingari M.C., Moretta A. Markers and function of human NK cells in normal and pathological conditions. Cytom Part B Clin Cytom. 2017;92:100–114. doi: 10.1002/cyto.b.21508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Watkins-Schulz R., Tiet P., Gallovic M.D., Junkins R.D., Batty C., Bachelder E.M., Ainslie K.M., Ting J.P.Y. A microparticle platform for STING-targeted immunotherapy enhances natural killer cell- and CD8+ T cell-mediated anti-tumor immunity. Biomaterials. 2019;205:94–105. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2019.03.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Seki T., Liu J., Brutkiewicz R.R., Tsuji M. A Potent CD1d-binding Glycolipid for iNKT-Cell-based Therapy Against Human Breast Cancer. Anticancer Res. 2019;39:549–555. doi: 10.21873/anticanres.13147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Rothammer A., Sage E.K., Werner C., Combs S.E., Multhoff G. Increased heat shock protein 70 (Hsp70) serum levels and low NK cell counts after radiotherapy – potential markers for predicting breast cancer recurrence? Radiat Oncol. 2019;14:78. doi: 10.1186/s13014-019-1286-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Qiu S.-Q., Waaijer S.J.H., Zwager M.C., de Vries E.G.E., van der Vegt B., Schröder C.P. Tumor-associated macrophages in breast cancer: Innocent bystander or important player? Cancer Treat Rev. 2018;70:178–189. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2018.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Mahmoud S.M.A., Lee A.H.S., Paish E.C., Macmillan R.D., Ellis I.O., Green A.R. Tumour-infiltrating macrophages and clinical outcome in breast cancer. J Clin Pathol. 2012;65:159–163. doi: 10.1136/jclinpath-2011-200355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Tiainen S., Tumelius R., Rilla K., Hämäläinen K., Tammi M., Tammi R., Kosma V.-M., Oikari S., Auvinen P. High numbers of macrophages, especially M2-like (CD163-positive), correlate with hyaluronan accumulation and poor outcome in breast cancer. Histopathology. 2015;66:873–883. doi: 10.1111/his.12607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Sousa S., Brion R., Lintunen M., Kronqvist P., Sandholm J., Mönkkönen J., Kellokumpu-Lehtinen P.-L., Lauttia S., Tynninen O., Joensuu H. Human breast cancer cells educate macrophages toward the M2 activation status. Breast Cancer Res. 2015;17:101. doi: 10.1186/s13058-015-0621-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Liu H., Wang J., Liu Z., Wang L., Liu S., Zhang Q. Jagged1 modulated tumor-associated macrophage differentiation predicts poor prognosis in patients with invasive micropapillary carcinoma of the breast. Medicine (Baltimore) 2017;96 doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000006663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Zhang W.-J., Wang X.-H., Gao S.-T., Chen C., Xu X.-Y., Sun Q., Zhou Z.-H., Wu G.-Z., Yu Q., Xu G. Tumor-associated macrophages correlate with phenomenon of epithelial-mesenchymal transition and contribute to poor prognosis in triple-negative breast cancer patients. J Surg Res. 2018;222:93–101. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2017.09.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Klingen T.A., Chen Y., Aas H., Wik E., Akslen L.A. Tumor-associated macrophages are strongly related to vascular invasion, non-luminal subtypes, and interval breast cancer. Hum Pathol. 2017;69:72–80. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2017.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Parkes E.E., Walker S.M., Taggart L.E., Mccabe N., Knight L.A., Wilkinson R., Mccloskey K.D., Buckley N.E., Savage K.I., Salto-tellez M. Activation of STING-Dependent Innate Immune Signaling By S-Phase-Specific DNA Damage in Breast Cancer. 2017;109:1–10. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djw199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Dunphy G., Flannery S.M., Almine J.F., Connolly D.J., Paulus C., Jønsson K.L., Jakobsen M.R., Nevels M.M., Bowie A.G., Unterholzner L. Non-canonical Activation of the DNA Sensing Adaptor STING by ATM and IFI16 Mediates NF-κB Signaling after Nuclear DNA Damage. Mol Cell. 2018;71:745–760. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2018.07.034. e5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Pantelidou C., Sonzogni O., de Oliveira Taveira M., Mehta A.K., Kothari A., Wang D., Visal T., Li M.K., Pinto J., Castrillon J.A. PARP inhibitor efficacy depends on CD8+ T cell recruitment via intratumoral STING pathway activation in BRCA-deficient models of triple-negative breast cancer. Cancer Discov. 2019 doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-18-1218. CD-18-1218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Pellegrino B., Llop-Guevara A., Cruz C., Castroviejo M., Cedro-Tanda A., Fasani R., Nuciforo P.G., Gros A., Balmaña J., O’Connor M.J. 18PDissecting the antitumor immune response upon PARP inhibition in homologous recombination repair (HRR)-deficient tumors. Ann Oncol. 2018:29. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Pellegrino B., Llop-Guevara A., Pedretti F., Cruz C., Castroviejo M., Cedro-Tanda A., Fasani R., Mateo F., Musolino A., Pujana M.A. 1873OPARP inhibition increases immune infiltration in homologous recombination repair (HRR)-deficient tumors. Ann Oncol. 2019:30. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Solinas C., Garaud S., De Silva P., Boisson A., Van den Eynden G., de Wind A., Risso P., Rodrigues Vitória J., Richard F., Migliori E. Immune Checkpoint Molecules on Tumor-Infiltrating Lymphocytes and Their Association with Tertiary Lymphoid Structures in Human Breast Cancer. Front Immunol. 2017;8:1412. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2017.01412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Criscitiello C., Bayar M.A., Curigliano G., Symmans F.W., Desmedt C., Bonnefoi H., Sinn B., Pruneri G., Vicier C., Pierga J.Y. A gene signature to predict high tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes after neoadjuvant chemotherapy and outcome in patients with triple-negative breast cancer. Ann Oncol. 2018;29:162–169. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdx691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Hendry S., Salgado R., Gevaert T., Russell P.A., John T., Thapa B., Christie M., Van De Vijver K., Estrada M.V., Gonzalez-Ericsson P.I. Assessing Tumor-infiltrating Lymphocytes in Solid Tumors: A Practical Review for Pathologists and Proposal for a Standardized Method from the International Immunooncology Biomarkers Working Group: Part 1: Assessing the Host Immune Response, TILs in Invasi. Adv Anat Pathol. 2017;24:235–251. doi: 10.1097/PAP.0000000000000162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Salgado R., Denkert C., Demaria S., Sirtaine N., Klauschen F., Pruneri G., Wienert S., Van den Eynden G., Baehner F.L., Penault-Llorca F. 2015. The evaluation of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILS) in breast cancer: Recommendations by an International TILS Working Group 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Garaud S., Zayakin P., Buisseret L., Rulle U., Silina K., de Wind A., Van den Eyden G., Larsimont D., Willard-Gallo K., Linē A. Antigen Specificity and Clinical Significance of IgG and IgA Autoantibodies Produced in situ by Tumor-Infiltrating B Cells in Breast Cancer. Front Immunol. 2018:9. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.02660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Buisseret L., Garaud S., de Wind A., Van den Eynden G., Boisson A., Solinas C., Gu-Trantien C., Naveaux C., Lodewyckx J.-N., Duvillier H. Tumor-infiltrating lymphocyte composition, organization and PD-1/ PD-L1 expression are linked in breast cancer. Oncoimmunology. 2017;6 doi: 10.1080/2162402X.2016.1257452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Sautès-Fridman C., Lawand M., Giraldo N.A., Kaplon H., Germain C., Fridman W.H., Dieu-Nosjean M.-C. Tertiary Lymphoid Structures in Cancers: Prognostic Value, Regulation, and Manipulation for Therapeutic Intervention. Front Immunol. 2016;7:407. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2016.00407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Solinas C., Carbognin L., De Silva P., Criscitiello C., Lambertini M. Tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes in breast cancer according to tumor subtype: Current state of the art. The Breast. 2017;35:142–150. doi: 10.1016/j.breast.2017.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Hendry S., Salgado R., Gevaert T., Russell P.A., John T., Thapa B., Christie M., van de Vijver K., Estrada M.V., Gonzalez-Ericsson P.I. Assessing Tumor-infiltrating Lymphocytes in Solid Tumors. Adv Anat Pathol. 2017;24:235–251. doi: 10.1097/PAP.0000000000000162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Denkert C., von Minckwitz G., Darb-Esfahani S., Lederer B., Heppner B.I., Weber K.E., Budczies J., Huober J., Klauschen F., Furlanetto J. Tumour-infiltrating lymphocytes and prognosis in different subtypes of breast cancer: a pooled analysis of 3771 patients treated with neoadjuvant therapy. Lancet Oncol. 2018;19:40–50. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(17)30904-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Salgado R., Loi S. Tumour infiltrating lymphocytes in breast cancer: increasing clinical relevance. Lancet Oncol. 2018;19:3–5. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(17)30905-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Luen S., Salgado R., Fox S., Savas P., Eng-Wong J., Clark E., Kiermaier A., Swain S., Baselga J., Michiels S. Tumour-infiltrating lymphocytes in advanced HER2-positive breast cancer treated with pertuzumab or placebo in addition to trastuzumab and docetaxel: a retrospective analysis of the CLEOPATRA study. Lancet Oncol. 2016;93:292–297. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(16)30631-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Loi S., Sirtaine N., Piette F., Salgado R., Viale G., Van Eenoo F., Rouas G., Francis P., Crown J.P.A., Hitre E. Prognostic and Predictive Value of Tumor-Infiltrating Lymphocytes in a Phase III Randomized Adjuvant Breast Cancer Trial in Node-Positive Breast Cancer Comparing the Addition of Docetaxel to Doxorubicin With Doxorubicin-Based Chemotherapy: BIG 02-98. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:860–867. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.41.0902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Adams S., Gray R.J., Demaria S., Goldstein L., Perez E.A., Shulman L.N., Martino S., Wang M., Jones V.E., Saphner T.J. Prognostic Value of Tumor-Infiltrating Lymphocytes in Triple-Negative Breast Cancers From Two Phase III Randomized Adjuvant Breast Cancer Trials: ECOG 2197 and ECOG 1199. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:2959–2966. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.55.0491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Carbognin L., Pilotto S., Nortilli R., Brunelli M., Nottegar A., Sperduti I., Giannarelli D., Bria E., Tortora G. Predictive and Prognostic Role of Tumor-Infiltrating Lymphocytes for Early Breast Cancer According to Disease Subtypes: Sensitivity Analysis of Randomized Trials in Adjuvant and Neoadjuvant Setting. Oncologist. 2016;21:283–291. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2015-0307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Ogiya R., Niikura N., Kumaki N., Bianchini G., Kitano S., Iwamoto T., Hayashi N., Yokoyama K., Oshitanai R., Terao M. Comparison of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes between primary and metastatic tumors in breast cancer patients. Cancer Sci. 2016;107:1730–1735. doi: 10.1111/cas.13101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Dieci M, Giaratano T, Miglietta F, Griguolo G, Orvieto E, Falci C, Giorgi C, Mioranza E, Tasca G, Cappellesso R, et al. Abstract P2-05-20: Tumor infiltrating lymphocytes in recurrent HER2+ and triple negative breast cancer: Prognostic value according to tumor phenotype. in Poster Session Abstracts (American Association for Cancer Research), P2-05-20-P2-05–20. doi:10.1158/1538-7445.SABCS16-P2-05-20

- 88.Gu-Trantien C., Loi S., Garaud S., Equeter C., Libin M., Wind A de, Ravoet M., Buanec H Le, Sibille C., Manfouo-Foutsop G. Vol. 123. 2013. pp. 2873–2892. (CD4+ follicular helper T cell infiltration predicts breast cancer survival). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Schmid P., Adams S., Rugo H.S., Schneeweiss A., Barrios C.H., Iwata H., Diéras V., Hegg R., Im S.-A., Shaw Wright G. Atezolizumab and Nab-Paclitaxel in Advanced Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:2108–2121. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1809615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Schmid P., Cortés J., Dent R., Pusztai L., McArthur G.A., Kuemmel S., Bergh J., Denkert C. KEYNOTE-522: Phase III study of pembrolizumab (pembro) + chemotherapy (chemo) vs placebo (pbo) + chemo as neoadjuvant treatment, followed by pembro vs pbo as adjuvant treatment for early triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) Ann Oncol. 2019;30(suppl_):851–934. [Google Scholar]

- 91.Samanta D., Park Y., Ni X., Li H., Zahnow C.A., Gabrielson E., Pan F., Semenza G.L. Chemotherapy induces enrichment of CD47+/CD73+/PDL1+ immune evasive triple-negative breast cancer cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2018;115:E1239–E1248. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1718197115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Cortés J., Lipatov O.N., Im S.-A., Gonçalves A., Lee S.K., Schmid P., Tamura K., Testa L. KEYNOTE-119: Phase 3 study of pembrolizumab (pembro) versus single-agent chemotherapy (chemo) for metastatic triple-negative breast cancer (mTNBC) Ann Oncol. 2019;30(suppl_):851–934. [Google Scholar]

- 93.Kok M., Voorwerk L., Horlings H., Sikorska K., van der Vijver K., Slagter M., Warren S., Ong S., Wiersma T., Russell N. Adaptive phase II randomized trial of nivolumab after induction treatment in triple negative breast cancer (TONIC trial): Final response data stage I and first translational data. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36:1012. [Google Scholar]

- 94.Loi S., Giobbe-Hurder A., Gombos A., Bachelot T., Hiu R., Curigliano G., Campone M., Biganzoli L., Bonnefoi H., Jerusalem G. Phase Ib/II study evaluating safety and efficacy of pembrolizumab and trastuzumab in patients with trastuzumab-resistant HER2-positive metastatic breast cancer: Results from the PANACEA (IBCSG 45-13/BIG 4-13/KEYNOTE-014) study. Cancer Res. 2017;78(4 Suppl) [Google Scholar]

- 95.Schmid P., Cruz C., Braiteh F.S., Eder J.P., Tolaney S., Kuter I., Nanda R., Chung C., Cassier P., Delord J.-P. Abstract 2986: Atezolizumab in metastatic TNBC (mTNBC): Long-term clinical outcomes and biomarker analyses. Cancer Res. 2017;77:2986. [Google Scholar]

- 96.Loi S., Giobbe-Hurder A., Gombos A., Bachelot T., Hui R., Curigliano G., Campone M., Biganzoli L., Bonnefoi H., Jerusalem G. Abstract GS2-06: Phase Ib/II study evaluating safety and efficacy of pembrolizumab and trastuzumab in patients with trastuzumab-resistant HER2-positive metastatic breast cancer: Results from the PANACEA (IBCSG 45-13/BIG 4-13/KEYNOTE-014) study. Cancer Res. 2018;78 GS2-06-GS2-06. [Google Scholar]

- 97.Denkert C., Wienert S., Poterie A., Loibl S., Budczies J., Badve S., Bago-Horvath Z., Bane A., Bedri S., Brock J. Standardized evaluation of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes in breast cancer: results of the ring studies of the international immuno-oncology biomarker working group. Mod Pathol. 2016;29:1155–1164. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2016.109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Dieci M., Radosevic-Robin N., Fineberg S., van den Eynden G., Ternes N., Penault-Llorca F., Pruneri G., D’Alfonso T., Demaria S., Castaneda C. Seminars in Cancer Biology Update on tumor-in fi ltrating lymphocytes ( TILs ) in breast cancer , including recommendations to assess TILs in residual disease after neoadjuvant therapy and in carcinoma in situ : A report of the International Immuno- Oncol. Semin Cancer Biol. 2017:1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2017.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Luen S., Virassamy B., Savas P., Salgado R., Loi S. The genomic landscape of breast cancer and its interaction with host immunity. The Breast. 2016;29:241–250. doi: 10.1016/j.breast.2016.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Schumacher T.N., Schreiber R.D. Neoantigens in cancer immunotherapy. Science. 2015;348:69–74. doi: 10.1126/science.aaa4971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Song Y., Barry W.T., Seah D.S., Tung N.M., Garber J.E., Lin N.U. Patterns of recurrence and metastasis in BRCA1/BRCA2-associated breast cancers. Cancer. 2019:32540. doi: 10.1002/cncr.32540. cncr. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Pellegrino B., Bella M., Michiara M., Zanelli P., Naldi N., Porzio R., Bortesi B., Boggiani D., Zanoni D., Camisa R. Triple negative status and BRCA mutations in contralateral breast cancer: a population-based study. Acta Biomed. 2016;87:54–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Stoppa-Lyonnet D. The biological effects and clinical implications of BRCA mutations: where do we go from here? Eur J Hum Genet. 2016;24:S3–S9. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2016.93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Nik-Zainal S., Davies H., Staaf J., Ramakrishna M., Glodzik D., Zou X., Martincorena I., Alexandrov L.B., Martin S., Wedge D.C. Landscape of somatic mutations in 560 breast cancer whole-genome sequences. Nature. 2016;534:47–54. doi: 10.1038/nature17676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Turner N., Tutt A., Ashworth A. Hallmarks of “BRCAness” in sporadic cancers. Nat Rev Cancer. 2004;4:814–819. doi: 10.1038/nrc1457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Nolan E., Savas P., Policheni A.N., Darcy P.K., Vaillant F., Mintoff C.P., Dushyanthen S., Mansour M., Pang J.B., Fox S.B. Combined immune checkpoint blockade as a therapeutic strategy for BRCA1-mutated breast cancer. Sci Transl Med. 2017;4922:1–13. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aal4922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Samstein R.M., Lee C.-H., Shoushtari A.N., Hellmann M.D., Shen R., Janjigian Y.Y., Barron D.A., Zehir A., Jordan E.J., Omuro A. Tumor mutational load predicts survival after immunotherapy across multiple cancer types. Nat Genet. 2019;51:202–206. doi: 10.1038/s41588-018-0312-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]