Abstract

Accumulation of lysosomal storage material and late-stage neurodegeneration are hallmarks of lysosomal storage disorders (LSDs) affecting the brain. Yet, for most LSDs, including CLN3 disease, the most common form of childhood dementia, it is unclear what mechanisms drive neurologic symptoms. Do deficits arise from loss of function of the mutated protein or toxicity from storage accumulation? Here, using in vitro voltage-sensitive dye imaging and in vivo electrophysiology, we find progressive hippocampal dysfunction occurs before notable lysosomal storage and neuronal loss in 2 CLN3 disease mouse models. Pharmacologic reversal of lysosomal storage deposition in young mice does not rescue this circuit dysfunction. Additionally, we find that CLN3 disease mice lose an electrophysiologic marker of new memory encoding — hippocampal sharp-wave ripples. This discovery, which is also seen in Alzheimer’s disease, suggests the possibility of a shared electrophysiologic signature of dementia. Overall, our data describe new insights into previously unknown network-level changes occurring in LSDs affecting the central nervous system and highlight the need for new therapeutic interventions targeting early circuit defects.

Keywords: Metabolism, Neuroscience

Keywords: Genetic diseases

Dysfunctional neuronal circuit activity arises before detectable histopathology in a lysosomal storage disease and mirrors abnormalities seen in more common adult-onset neurodegenerative disorders.

Introduction

Lysosomal storage disorders (LSDs) are a collection of over 70 multiorgan, progressive diseases affecting approximately 1 in 5000 individuals (1). The biochemical basis of many LSDs is well understood, with most genetic changes leading to alteration of enzymatic activity in lysosomes. Over the last decade advances in enzyme replacement have led to treatments that stabilize progression or reverse many of the somatic symptoms of LSDs. However, two-thirds of LSD patients have neurologic symptoms, and currently available therapies do not improve central nervous system (CNS) disease manifestations (2). Further, despite understanding the biochemical basis of most LSDs, the mechanisms driving neurologic symptoms, such as seizures or dementia, are largely unknown. Although it has been proposed that cell death drives symptoms, recent work highlights that cellular dysfunction begins long before cell loss in some LSDs (3).

One such neuronopathic LSD, CLN3 disease or juvenile neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis (NCL), arises from biallelic mutations in CLN3. This is the most common subtype of the NCL disorders, which collectively are the leading cause of childhood dementia (4, 5). Typical disease progression begins with vision loss in early childhood, and subsequently patients experience neurocognitive regression (6), psychiatric symptoms, seizures (7), and in most cases, death by the third decade. Despite the identification of CLN3 as the causative gene for CLN3 disease 20 years ago (8) and the publication of many papers probing cellular mechanisms of CLN3 mutations or loss (9), the exact protein function and disease pathophysiology remain poorly understood.

Cytoplasmic accumulation of autofluorescent storage material, inflammation, and neurodegeneration occur throughout the brains of both CLN3 patients and mouse models. The hippocampus appears to be particularly vulnerable to disease with relatively early pathologic changes (10–14). Consistent with this, CLN3 patients suffer from progressive memory impairment, and 1 mouse model demonstrates deficits in hippocampal-mediated learning and memory (11, 15), along with functional defects in specific hippocampal cell types in late-stage disease (11, 16).

We hypothesize that neurologic symptoms in LSDs arise because loss of protein function or enzyme activity alters neuronal activity, ultimately inducing activity-dependent changes in functional neuronal circuits, such as the hippocampus. The corollary of this hypothesis is that delayed correction of the underlying deficiency may be insufficient to restore circuit function and improve symptoms. To date, the lack of meaningful clinical benefit of several brain-directed LSD therapeutic trials, despite improving biochemical markers of disease in the CNS, supports this possibility (17–21).

As an important investigation into the role of circuit dysfunction in the pathogenesis of LSDs, we used in vivo electrophysiology and in vitro voltage-sensitive dye imaging (VSDI) techniques in 2 mouse models of CLN3 disease (10, 22, 23). We found that alterations in hippocampal dynamics arise very early in the disease course, before lysosomal storage or neuronal loss, and progress with age. Furthermore, CLN3 disease mice display network alterations reported previously in epilepsy and dementia models, suggesting that disorders arising from disparate molecular mechanisms may progress to have shared circuit pathology.

Results

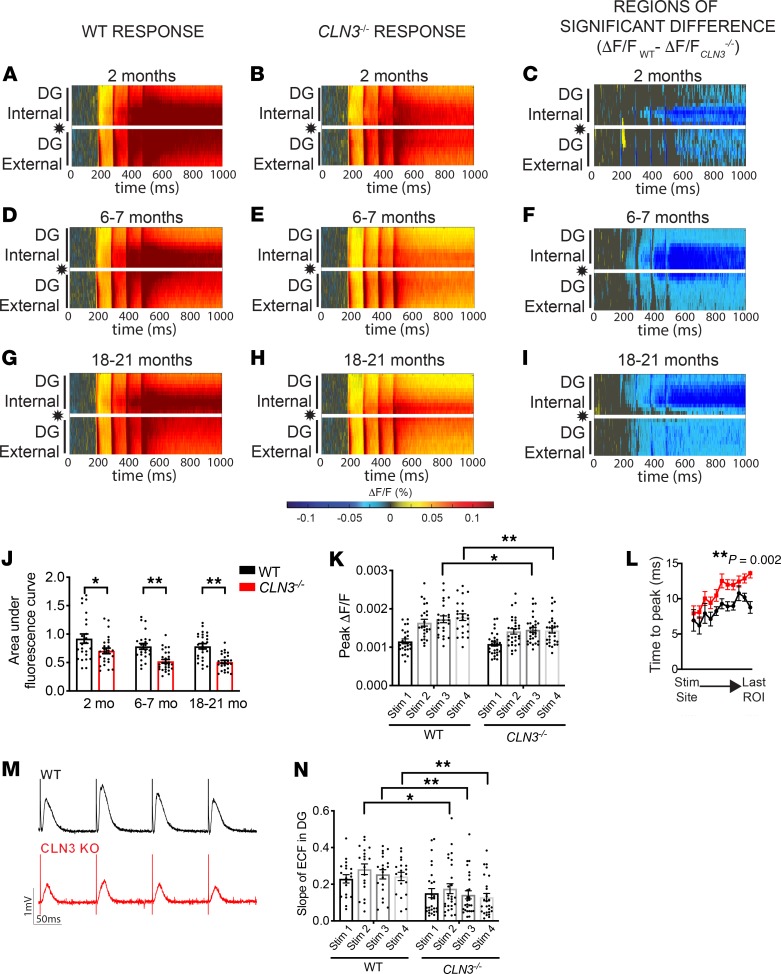

The CLN3–/– hippocampus shows progressive network hypoexcitability after perforant path stimulation.

To understand the hippocampal circuit dynamics contributing to CLN3-associated symptoms such as seizures and dementia, we performed VSDI in hippocampal slices from WT and CLN3LacZ/LacZ (CLN3–/–) mice across the life span. Fluorescence change in the entire hippocampus was quantified using our previously reported VSDI statistical toolbox (24).

At 2 months of age (very early–stage disease, see Supplemental Figure 1A for disease timeline; supplemental material available online with this article; https://doi.org/10.1172/jci.insight.131961DS1), CLN3–/– mice begin to show subtle motor defects on rotorod testing; however, at this age mice show no other notable behavioral phenotypes (10, 23); there is limited storage accumulation and no neuronal loss (Supplemental Figure 1, B–I). To investigate whether functional circuit-level defects precede neuropathologic changes, VSDI of the hippocampus was completed in hippocampal slices from 2-month-old WT and CLN3–/– mice (Supplemental Figure 1J). In very early–stage disease the dentate gyrus (DG) of CLN3–/– mice was hypoexcitable to perforant path (PP) stimulation as compared with WT (Figure 1, A–C and Supplemental Figure 2A). In the DG, there were multiple statistically significant regions of decreased fluorescence change evident on the raster plots at this young age. The internal blade of the DG appeared more hypoexcitable, with 39.5% of the regions of interest (ROIs) demonstrating a P value less than 0.05, as compared with 29% of ROIs in the external blade.

Figure 1. Activation of the DG after PP stimulation is significantly decreased in CLN3–/– mice by 2 months of age.

(A–I) Raster plots of average fluorescence change (ΔF/F; warm colors, excitation; cool colors, inhibition) over time (x axis) and location within the hippocampus (y axis). PP stimulation location indicated by star. (A) Stimulation of the PP in 2-month-old animals reveals robust excitation of the DG in WT mice. (B) CLN3–/– DG is hypoexcitable as compared with WT after PP stimulation. (C) WT vs. CLN3–/– rasters were compared using a permutation sampling method. Pixels with P > 0.05 are masked in gray. For regions of significance with P < 0.05, the difference in fluorescence change (ΔF/FWT – ΔF/FCLN3KO) is shown. (D–F) The CLN3–/– DG continues to be hypoexcitable at 6–7 months and (G–I) 18–21 months. (J) Quantification of total fluorescence change in the entire DG supports hypoexcitability in CLN3–/– mice (2-way ANOVA, followed by Tukey’s multiple-comparisons test). (K) Peak fluorescence is also decreased in CLN3–/– mice (1-way ANOVA, followed by Holm-Šídák multiple-comparisons test). (L) Signal propagation is slowed in the 2-month-old CLN3–/– DG, as measured by time to peak response in regions of interest moving from the stimulation site to the distal end of the DG (2-way ANOVA). (M and N) The magnitude and slope of the extracellular field response recorded during VSD experiments in 6-month-old WT and CLN3–/– DG supports hypoexcitability in CLN3–/– DG (1-way ANOVA, followed by Holm-Šídák multiple-comparisons test). For all panels: *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01. Group sizes (n = slices, N = mice): 2-month WT n = 24, N = 6; 2-month CLN3–/– n = 26, N = 5; 6- to 7-month WT n = 23, N = 5; 6- to 7-month CLN3–/– n = 30, N = 8; 18- to 21-month WT n = 25, N = 7; 18- to 21-month CLN3 n = 26, N = 7. For all graphs mean ± SEM shown.

By 6 months of age (early-stage disease), there was a progressive decrease in DG response to PP stimulation in the CLN3–/– hippocampus (Figure 1, D–F and Supplemental Figure 2B). This change persisted through late-stage disease (Figure 1, G–I, and Supplemental Figure 2C). Decreased activity of the DG reached its nadir by 6 months and did not progress further (Figure 1J), despite the progressive hippocampal storage accumulation that has been described to occur over this time frame in CLN3 disease mice (10, 25).

In addition to a reduction in total excitation, peak excitation levels (Figure 1K) and the rate of signal propagation through the CLN3–/– DG were reduced (Figure 1L). Extracellular field recordings from the granule cell layer of the DG recapitulated and supported the DG network hypoexcitability found by VSDI. Field responses from CLN3–/– mice showed decreased magnitude and slope as compared with WT by 6 months of age (Figure 1, M and N).

VSDI investigations were also completed in a second model of CLN3 disease, specifically, the Cln3Δex7/8 B6.129(Cg)-Cln3tm1.1Mem/J (CLN3Δex7/8) mouse. This model harbors the most common human CLN3 disease mutation. Similar to knockout mice, CLN3Δex7/8 mice accumulate storage material, have measurable neurodegeneration, and develop motor deficits (22). As in the CLN3–/– model, CLN3Δex7/8 mice show hypoexcitability of the DG in response to PP stimulation (Supplemental Figure 3). Cumulatively, the data demonstrate that DG hypoexcitability is a feature of CLN3 deficiency and not specific to a particular model.

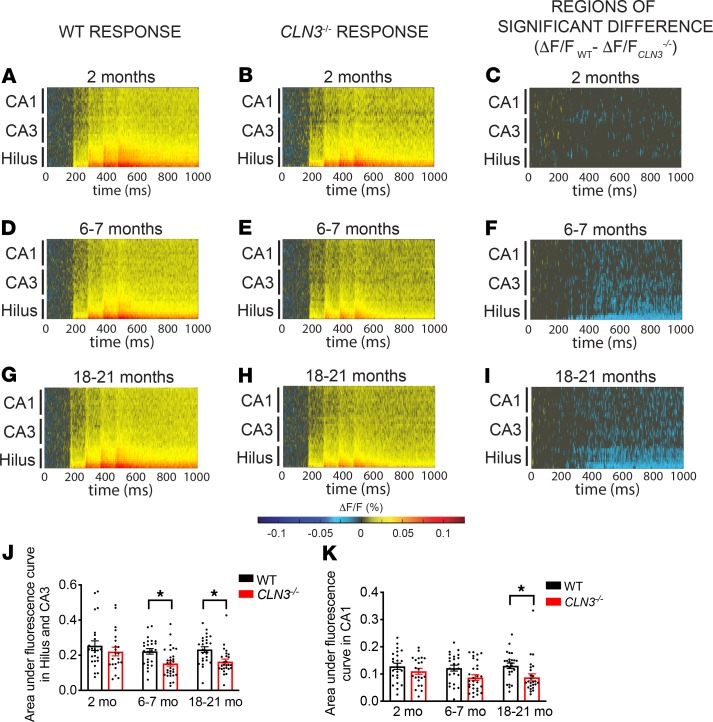

Measurement of the VSDI response in the CA proper region after PP stimulation also revealed a progressive decrease in activity. At 2 months of age, there were only subtle differences between the WT and CLN3–/– excitation patterns (Figure 2, A–C, and Supplemental Figure 4A). However, by 6 months of age the hilus and CA3 regions showed decreased activity (Figure 2, D–F, and Supplemental Figure 4B). By 18 months of age, all regions of the hippocampus had decreased activity after PP stimulation (Figure 2, G–I, and Supplemental Figure 4C). Quantification of the difference in total fluorescence further confirmed these findings (Figure 2, J and K).

Figure 2. Activation of the CA3 and CA1 after perforant path stimulation are significantly decreased in CLN3–/– mice by 6 and 18 months of age, respectively.

(A and B) Raster plots reveal that PP stimulation results in moderate excitation of both WT and CLN3–/– stratum radiatum of the hilus, CA3, and CA1 at 2 months of age. (C) Permutation sampling analysis at 2 months demonstrates minimal differences in excitability between WT and CLN3–/–. Pixels with P > 0.05 are masked in gray. For regions of significance with P < 0.05, the difference in fluorescence change (ΔF/FWT – ΔF/FCLN3KO) is shown. Cooler colors indicate relative hypoexcitability of the CLN3–/– CA proper. (D–F) At 6–7 months and (G–I) 18–21 months of age, there is progressive hypoexcitability throughout the CA proper. (J) Quantification of total fluorescence change in the hilus and CA3 regions supports hypoexcitability in CLN3–/– mice at 6 and 18 months. (K) The CA1 region demonstrates a significant decrease in excitability by 18 months. (J and K, 2-way ANOVA, followed by Tukey’s multiple-comparisons test). For all panels: *P < 0.05. Group sizes (n = slices, N = mice): 2-month WT n = 24, N = 6; 2-month CLN3–/– n = 26, N = 5; 6- to 7-month WT n = 23, N = 5; 6- to 7-month CLN3–/– n = 30, N = 8; 18- to 21-month WT n = 25, N = 7; 18- to 21-month CLN3 n = 26, N = 7. For all graphs mean ± SEM shown.

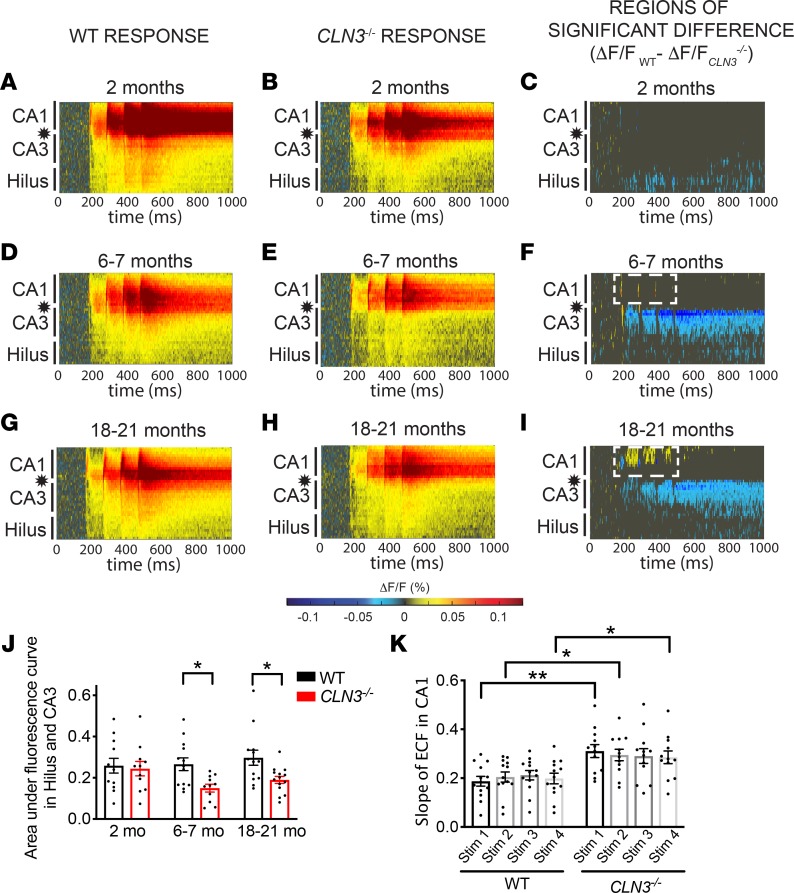

The CLN3–/– CA1 region becomes hyperexcitable in response to Schaffer collateral stimulation in very late–stage disease.

Next, VSDI responses in the CLN3–/– hippocampus were measured after Schaffer collateral (SC) stimulation to directly evaluate CA1 region excitability. Similar to the findings after PP stimulation, there were only minimal differences in the response of the CA proper after SC stimulation at 2 months of age (Figure 3, A–C, and Supplemental Figure 4D). Also, as was seen after PP stimulation, the hilus and CA3 regions showed decreased activity after SC stimulation by 6 months (Figure 3, D–F, and Supplemental Figure 4E) and continued to show decreased activity at 18 months (Figure 3, G–J, and Supplemental Figure 4F). However, unlike the response seen after PP stimulation, direct stimulation of the CA1 revealed network hyperexcitability that was first noted as an increase in the VSDI peak response (Figure 3, D–F) and the extracellular field response measured in CA1 stratum oriens (Figure 3K) at 6 months of age. CA1 hyperexcitability increased with disease progression (Figure 3, G–I).

Figure 3. As CLN3 disease progresses, CA1 becomes hyperexcitable in response to SC stimulation.

(A and B) Raster plots of VSDI signal after SC stimulation (location indicated by star) reveals robust excitation of the stratum radiatum of the CA proper in 2-month-old WT and CLN3–/– hippocampal slices. (C) Permutation sampling analysis shows hypoexcitability of the hilus after SC stimulation at 2 months of age. (D–F) By 6–7 months, the CLN3–/– hippocampus demonstrates hypoexcitability of the hilus and CA3 regions as compared with WT. However, in CA1 there is emerging increased peak fluorescence in response to SC stimulation (area of warm-colored peaks, demarcated by dashed, white line in F). (G–I) By late-stage disease (18–21 months) the CA1 region of the CLN3–/– hippocampus is hyperexcitable after SC stimulation as compared with WT (region of increased activation outlined by white, dashed line). (J) Quantification of total fluorescence change in the hilus and CA3 regions confirms hypoexcitability in CLN3–/– mice at 6 and 18 months (2-way ANOVA, followed by Tukey’s multiple-comparisons test). (K) Analysis of extracellular field responses recorded in CA1 during VSD experiments confirms an increase in peak excitability in CLN3–/– slices as compared with WT at 6 months of age (1-way ANOVA, followed by Holm-Šídák multiple-comparisons test). For all panels: *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01. Group sizes (n = slices, N = mice): 2-month WT n = 13, N = 5; 2-month CLN3–/– n = 11, N = 5; 6- to 7-month WT n = 13, N = 4; 6- to 7-month CLN3–/– n = 11, N = 3; 18- to 21-month WT n = 13, N = 4; 18- to 21-month CLN3–/– n = 14, N = 4. For all graphs mean ± SEM shown.

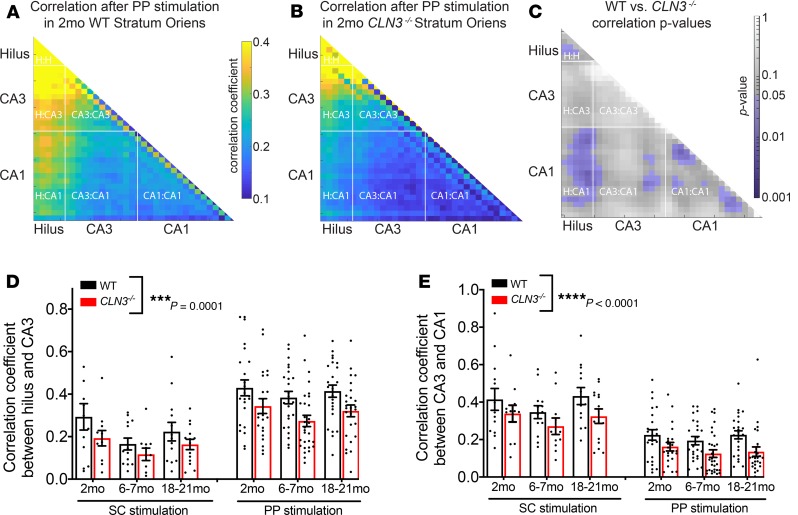

CLN3–/– mice have decreased coordination of hippocampal network activity.

We subsequently examined whether CLN3 deficiency alters network coordination throughout the circuit as quantified using VSDI. To examine this prospect, the correlation coefficient of the VSDI signal in each region of interest in each slice was calculated, and an average correlation map for the whole circuit was created (Figure 4, A and B). As early as 2 months of age, there was a widespread decrease in the network coordination in most of the hippocampus after PP stimulation, with the hilus-to-hilus, hilus-to-CA1, CA3-to-CA1, and CA1-to-CA1 correlations reaching statistical significance (Figure 4C). Interestingly, this decreased correlation occurred before widespread differences in excitability of the CA proper (Figure 2, A–C, J, and K). Quantification of the average correlation coefficient in response to both PP and SC stimulation confirmed that the CLN3–/– hippocampus had decreased synchronization of activity in all regions investigated (Figure 4, D and E).

Figure 4. All regions of the hippocampus have a decrease in correlation of activity that begins in early-stage CLN3 disease.

The correlation coefficient between activity levels in each region of interest in the CA proper was calculated to evaluate network coordination. (A and B) At 2 months of age, the CLN3–/– hippocampus demonstrates a global decrease in correlation. (C) Regions of statistical differences in correlation coefficients in WT and CLN3–/– slices were identified using a permutation sampling method. Areas of statistical significance with P < 0.05 are shown in purple. (D) Regional correlation levels between the hilus and CA3 were calculated in response to PP (top) and SC (bottom) stimulation. In response to both stimulation protocols and at all ages, network activity was less correlated in CLN3–/– slices (2-way ANOVA, P value for genotype factor WT vs. CLN3–/– ***P = 0.0001). (E) A similar CLN3 disease–associated decrease in regional correlation coefficients was noted between CA3 and CA1 (2-way ANOVA, P value for genotype factor WT vs. CLN3–/– ****P < 0.0001). Group sizes as listed in Figures 1–3. For all graphs mean ± SEM shown.

Carbenoxolone, a drug that reduces storage burden in CLN3–/– mice, worsens disease-induced network differences as measured by VSDI.

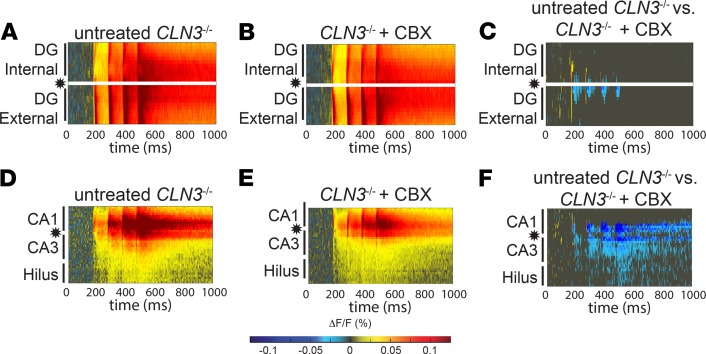

To evaluate whether a therapy that corrects blood-brain barrier (BBB) deficits and storage burden could improve network dynamics, mice were treated with carbenoxolone (CBX). This small molecule corrected endocytosis defects in vitro and BBB deficits and lysosomal storage burden in vivo in CLN3–/– mice (25, 26). Two-month-old control and CLN3–/– mice were treated with 20 mg CBX for 2 weeks, a dose shown previously to reduce storage accumulation (25). CBX did not improve DG hypoexcitability after PP stimulation (Figure 5, A–C, and Supplemental Figure 5, A–C). Furthermore, CBX exacerbated hypoexcitability of the hippocampal hilus and CA3 regions after SC stimulation (Figure 5, D–F, and Supplemental Figure 5, D–F), relative to untreated 2-month-old mice. These data suggest that correction of storage burden may be insufficient to restore hippocampal function in CLN3–/– mice.

Figure 5. CBX, a drug that reduces storage burden, cannot correct hypoexcitability of the DG and worsens hypoexcitability of the hilus and CA3 in early-stage CLN3 disease.

(A–C) Hippocampal slices from 2-month-old CLN3–/– mice treated with 2 weeks of 20 mg CBX, a dose that reduces storage burden and normalizes endocytosis in vivo, show residual hypoexcitability of the DG after PP stimulation, as measured by VSDI response as compared with untreated CLN3–/– slices. (D–F) CBX treatment worsened hypoexcitability of the hilus and CA3 after SC stimulation as compared with untreated CLN3–/–. Group sizes (n = slices, N = mice): 2-month PP stimulation untreated n = 26, N = 5; CBX-treated n = 25, N = 5; 2-month SC stimulation untreated n = 11, N = 5; CBX-treated n = 20, N = 5. Areas of statistical significance identified using a permutation sampling method; for regions of significance with P < 0.05, the difference in fluorescence change (ΔF/FUntreated – ΔF/FCBX) is shown. Panel A reproduced from Figure 1B. Panel D reproduced from Figure 3B.

CLN3–/– mice have increased spiking activity on EEG.

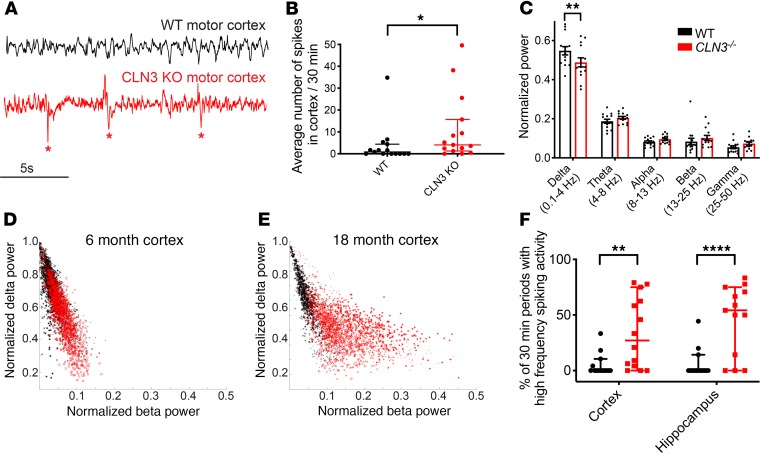

Most patients with CLN3 disease experience seizures and neurocognitive regression and manifest abnormalities on EEG (7). To investigate whether CLN3–/– mice demonstrate EEG abnormalities, 8-electrode intracranial EEG recordings were obtained from 14 WT and CLN3–/– adult mice. Electrodes were implanted into the cortex (barrel field, motor, and visual cortex) and into the hippocampal CA1 region, bilaterally. CLN3–/– mice had epileptiform discharges with high-frequency spiking activity (Figure 6, A and B) in both the cortex and hippocampus. An overt generalized tonic-clonic seizure was observed in only 1 CLN3–/– mouse (and never observed in WT mice); however, very late–stage mice (18 months and older) displayed frequent freezing behavior, which was often associated with brief runs of spiking activity on EEG.

Figure 6. CLN3–/– mice have increased spiking activity on EEG.

(A) EEG recordings from the motor cortex of CLN3–/– (red) mice demonstrate increased frequent spiking activity (marked by asterisk), as compared with WT (black) animals. (B) Quantification of spikes from all adult animals (≥6 months of age) demonstrates increased spiking activity in CLN3–/– animals (median ± 95% CI shown). (C) Quantification of power in the major EEG frequency bands in WT and CLN3–/– animals reveals that CLN3–/– mice have decreased slow delta activity (0.1–4.0 Hz) (mean ± SEM shown). (D and E) Further evaluation of the power in the fast beta and slow delta frequency ranges shows no major difference in the ratio of delta to beta power at 6 months. However, by late-stage disease CLN3–/– mice have increased fast beta and decreased slow delta power on EEG. (F) Adult CLN3–/– mice have increased percentage of recording periods with both increased fast and high spiking activity (median ± 95% CI shown). Group sizes: n = 14 mice per genotype (4–5 per age group of 6 months, 11 months, and 18+ months). For spike quantification and quantification of spiking/high-frequency periods in panels B and F, groups were compared using Mann-Whitney U test. For frequency band analysis in panel C, groups were compared using 2-way ANOVA followed by Holm-Šídák multiple-comparisons test. For all panels: *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ****P < 0.0001.

Patients with epilepsy often demonstrate shifts in background EEG frequency composition (27); to evaluate whether CLN3 disease mice replicated this finding, quantitative EEG analysis was completed. Specifically, analysis of the frequency content of the baseline EEG using fast Fourier transform analysis revealed that CLN3–/– mice have a decrease in relative power in the slow activity delta frequency band (0.1–4.0 Hz) (Figure 6C). This is associated with a trend toward increased fast activity in the beta (13–25 Hz) and gamma (25–50 Hz) bands. Plotting the instantaneous ratio of the fast beta activity to slow delta activity in 6-month-old (early-stage disease) animals (Figure 6D) demonstrated no major differences. However, with disease progression, by 18 months of age (Figure 6E), there was increased fast beta frequency power with decreased slow delta activity, as shown by the separation between the measures from control (shown in black) and CLN3–/– mice (shown in red). CLN3–/– mice also had a significantly higher percentage of recording periods with both increased fast activity and spiking activity in the cortex and hippocampus (Figure 6F).

Hippocampal sharp-wave ripple abundance decreases with CLN3 disease progression.

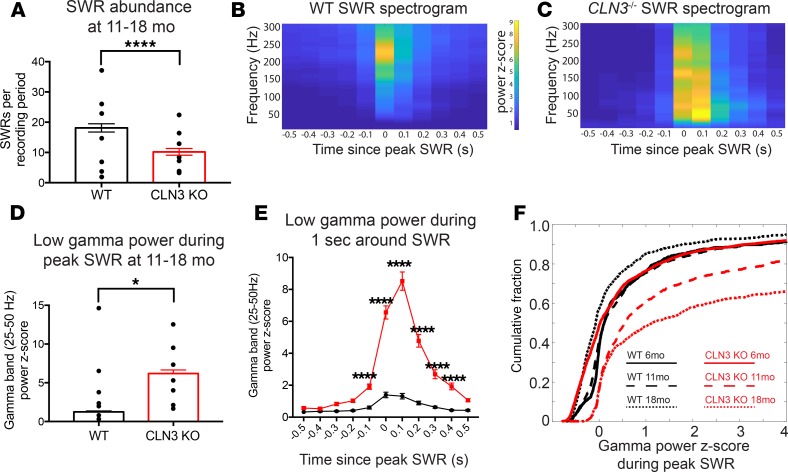

To further investigate disease-induced changes in hippocampal network dynamics that may be related to the progressive dementia found in the patients and mice, we quantified sharp-wave ripples (SWRs), oscillations important for memory consolidation that are disrupted in Alzheimer’s disease (AD) (28–33). SWRs during low theta periods were identified in EEGs recorded from the CA1 region of the hippocampus of WT and CLN3–/– mice (Supplemental Figure 6). The abundance of SWRs decreased in CLN3–/– hippocampus over the course of disease. In early-stage disease (6 months), there was no difference in SWR rate (Supplemental Figure 7). However, similar to reports of AD mouse models (31–33), late-stage animals (11 months or older) had a reduction in the number of hippocampal SWRs (Figure 7A).

Figure 7. Like AD mouse models, late-stage CLN3–/– mice have fewer SWRs than WT. Ripples that do occur trigger an exaggerated gamma frequency response.

(A) Quantification of SWRs per 30-minute recording from the hippocampal EEGs of WT (shown in black) and CLN3–/– (shown in red) mice reveals decreased SWR abundance in CLN3–/– mice. Group sizes in A: WT n = 118 thirty-minute recordings, N = 7 mice; CLN3–/– n = 142 thirty-minute recordings, N = 7 mice. Bar graphs show mean ± SEM and SWR number from all recordings; black points show mean SWR abundance for each mouse. Statistical analysis was completed 2 ways (Mann-Whitney U test comparing the SWR number between all WT and CLN3–/– recording periods and 2-way ANOVA to capture variation because of both individual mice and genotype); both demonstrated a difference between genotypes with ****P < 0.0001. (B and C) Average spectrogram of the 1 second surrounding SWRs detected in WT and CLN3–/– hippocampus shows that in WT animals there is a brief increase in power in the ripple frequency band (150–250 Hz), while in CLN3–/– animals there is a prolonged increase in power in multiple frequency bands. (D) Peak power in the low gamma range after an SWR is increased in CLN3–/– mice as compared with WT. (E) Gamma power is increased in CLN3–/– (red) mice for several hundred milliseconds surrounding the peak SWR as compared with WT (black) (2-way ANOVA followed by Holm-Šídák multiple-comparisons test). Group sizes for D and E: WT n = 2059 SWRs, N = 7 mice; CLN3–/– n = 1363 SWRs, N = 7 mice. Bar graphs show mean ± SEM gamma power from all SWRs; black points show mean peak gamma power during SWRs by mouse. Statistical analysis was completed 2 ways: Mann-Whitney U testing comparing peak gamma power in all WT and CLN3–/– SWRs gave ****P < 0.0001; while 2-way ANOVA to capture variation because of both individual mice and genotype showed a genotype effect with *P = 0.03. (F) In CLN3–/– hippocampus, the cumulative fraction of SWRs triggering a high-power gamma frequency response increases with disease progression from 6 months (solid line, WT n = 1334 SWRs, CLN3–/– n = 2040 SWRs, N = 4 mice/genotype), to 11 months (large dashed line, WT n = 1114 SWRs, CLN3–/– n = 833 SWRs, N = 4 mice/genotype), to 18 months (small dashed line, WT n = 947 SWRs, CLN3–/– n = 942 SWRs, N = 3 mice/genotype).

SWRs trigger an increase in power in multiple frequency bands in the CLN3–/– hippocampus.

Physiologic SWRs in the hippocampus are coupled with a power spectral peak in the slow gamma (25–50 Hz) frequency range (34, 35). This oscillation is thought to arise from the entrainment of the CA1 region of the hippocampus by the CA3 region during a SWR (34, 36–38). Spectral analysis of the 1-second period surrounding SWRs in control mice revealed an increase in the Z-score gamma oscillation power (Figure 7B) that is comparable to previously reported data (33). CLN3–/– mice demonstrated increased power in multiple frequency bands, not just increased gamma power, during SWRs (Figure 7C and Supplemental Figure 8). Furthermore, the magnitude of the gamma power elevation triggered by SWRs was higher in the CLN3–/– hippocampus as compared with controls (mean low gamma Z-score at peak SWR 1.3 ± 0.1 vs. 6.2 ± 0.5) (Figure 7, D–F).

This exaggerated increase in gamma frequency power during SWRs was a progressive feature of CLN3–/– mice. During SWRs 6-month-old control and CLN3–/– mice had similar distributions of their low gamma power Z-scores (Figure 7F, solid lines). However, in middle-stage disease (11-month-old, Figure 7F, long dashed lines) and late-stage disease (18- month-old, Figure 7F, short dashed lines) there was a progressive absolute and relative increase in gamma power Z-score during SWRs as compared with controls.

It has been proposed that increased gamma power during physiologic SWRs may be due to an artifact arising from the overlap of multiple SWRs or prolongation of SWR duration (39) rather than a true gamma frequency oscillation. Prolongation of ripple duration is not the mechanism of exaggerated increased gamma power in CLN3–/– mice because SWR duration did not differ between control and CLN3–/– groups (Supplemental Figure 9).

In summary, CLN3–/– mice demonstrate progressive abnormalities in physiologic hippocampal high-frequency oscillations on EEG.

Discussion

In this study, we provide the first comprehensive evaluation of how a neuronopathic LSD progressively disrupts a functional neuronal circuit through in vitro and in vivo studies of mouse models of CLN3 disease. Consideration of neuronopathic LSDs as disorders of functional networks provides a potentially novel framework for understanding pathogenesis and can help inform therapy development.

Non-neurologic complications of many LSDs, such as hepatic and cardiac symptoms, can be treated through enzyme replacement or gene therapy strategies (for a review, see ref. 2). Conversely, correction of biochemical defects in the CNS has failed to improve neurocognitive outcomes in most therapeutic trials (17–21). Among the 12 LSD enzyme replacement or small molecule therapies approved in the United States as of 2018 (40), only 1, intraventricular cerliponase alfa therapy for CLN2 disease, is approved for a neurologic indication (41). This medication has been shown to slow the rate of neurologic progression but cannot reverse symptoms. Failure to improve neurologic features may be due to residual circuit-level pathology that remains after biochemical correction.

Through VSDI investigations, we found that all regions of the hippocampus in CLN3–/– mice show progressive hypoexcitability in response to perforant path stimulation. This hypoexcitability may contribute to the learning difficulties and dementia that arise in patients early in the disease course. In late-stage animals, the CA1 region becomes hyperexcitable to SC stimulation. CA1 hyperexcitability is a known epileptogenic trigger (42) and may contribute to the late-onset epilepsy seen in CLN3 disease patients.

Future patch-clamp electrophysiology studies of multiple cell types in the hippocampus in CLN3 disease mice across the life span could help delineate whether network differences arise from intrinsic differences in neuronal excitation, alterations in network connectivity, or a combination of both factors. It is also possible that alterations in perforant path myelination or structure could contribute to DG hypoexcitability. Detailed histologic evaluation of the perforant path across the life span of CLN3 disease mice is lacking; however, MRI studies in late-stage CLN3 disease mice suggest that white matter generally appears less affected than gray matter (43).

In this work we began our studies in very early–stage disease (2 months of age); at this time point CLN3–/– mice show very subtle differences on rotorod testing (10) but have no storage accumulation or neuronal loss in the hippocampus. Our VSDI findings of altered excitability in 2-month-old CLN3–/– hippocampal slices suggest that lysosomal defects can disrupt CNS function well before cell death occurs (10, 11, 23). Increased axonal excitability has been reported previously in very early–stage CLN3Δex7/8 mice (16). Early changes in intrinsic or synaptic properties of CLN3–/– neurons and/or glia may establish abnormal electrical networks that cannot be corrected through reversal of the lysosomal defect alone. This is supported by our findings that early treatment with CBX, a drug that corrects endocytosis defects and clears storage material in CLN3–/– mice (25, 26), cannot rescue circuit physiology.

In vivo EEG analysis of CLN3–/– mice also demonstrated progressive abnormalities. Like other seizure models, middle- and late-stage CLN3–/– mice (aged 6 months and older) had frequent epileptiform discharges with increased spiking activity in both cortical and hippocampal electrodes. The presence of an epileptiform EEG phenotype in CLN3–/– mice suggests it is a suitable model for investigations of disease-associated circuit alterations.

Clinically validated, reliable, noninvasive biomarkers of CLN3 disease progression are lacking in both mouse models and human patients (44). The progressive quantifiable shift toward increased power in high-frequency EEG bands (i.e., an increase in the ratio of beta to delta power) in these longitudinal CLN3–/– mice EEG studies suggests that this may be a biomarker of disease progression. Similar studies in humans or in mice are needed to evaluate whether quantitative analysis of serial EEG recordings could be used to monitor CLN3 disease severity, progression, and response to potential therapies.

Circuit-level analysis also allows for comparisons among neurodegenerative disorders that share common symptoms, such as dementia, but arise from unique molecular mechanisms. We identified that late-stage CLN3–/– mice, like several mouse models of AD, have a decrease in the absolute number of hippocampal SWRs, a physiologic oscillation important for memory consolidation (31–33). Identification of shared network features could motivate future studies of network-targeted therapies, which are under development for AD (45–48), in CLN3 disease. Studies of hippocampal-mediated learning and memory in CLN3–/– mice across the life span are needed to fully characterize the impact of these network alterations.

Unlike in AD, when a SWR occurs in late-stage CLN3–/– mice, it triggers a pathogenic oscillatory response in the hippocampus with an exaggerated increase in the power of multiple EEG frequency bands. This may be related to the CA1 hyperexcitability noted in late-stage disease or the alterations in coordinated network activity identified through VSDI. Regardless of specific mechanism, this abnormal oscillatory response likely reflects generalized hippocampal circuitry pathology that may contribute to the epileptiform discharges identified on EEG in the setting of CLN3 deficiency.

It is difficult to extrapolate directly from in vitro VSDI studies of the ventral hippocampus to in vivo EEG recordings, which capture activity in the dorsal hippocampus and cortical structures. However, the identification of network-level differences on both recording modalities strongly supports the presence of dysfunctional neuronal circuits throughout the brain in CLN3 disease.

In summary, in vitro and in vivo electrophysiology studies of preclinical models of CLN3 disease revealed early and progressive hippocampal network alterations that arose before substantial storage accumulation or cell death occurred. Treatment with a drug that improves cellular phenotypes and reduces storage accumulation could not reverse hippocampal circuit pathology. The increased spiking activity seen on EEG and increased excitability of the CA1 on VSDI are consistent with the known seizure phenotype of CLN3 disease. CLN3–/– mice also demonstrated a progressive loss of SWRs, physiologic oscillations underlying memory consolidation. This mirrors findings in mouse models of AD, providing the intriguing possibility that different forms of dementia share common network deficits. These data highlight the need for novel therapies for neuronopathic LSDs that correct both cellular-level biochemistry and the primary circuit-level dysfunction.

Methods

Mice

CLN3LacZ/LacZ (i.e., CLN3–/–), CLN3LacZ/WT (both generated in-house, ref. 10), CLN3Δex7/8 (Jackson Laboratories, 017895), and WT mice were bred, housed, maintained, and genotyped in our laboratory as previously described (10, 23, 25). All mice were maintained on a C57BL/J6 background. Male and female mice were used for all experiments.

For CBX studies, as previously published (25), a 0.5-M CBX disodium salt (Abcam) stock solution was prepared in ethanol. The stock was further diluted in saline to a final concentration of 2.0 mg/mL for gavage. Mice were administered 20 mg/kg CBX by gavage each morning for 14 days.

Slice preparation for VSDI

For VSDI studies, 400-μm hippocampal-entorhinal cortical slices, which preserve the hippocampal trisynaptic circuit (49–53), were prepared as per our standard protocols (24). Slices were cut in a high-sucrose cutting solution containing, in mM, 192 sucrose, 2.5 KCl, 1.25 NaH2PO4, 26 NaHCO3, 12.2 glucose, 3 sodium pyruvate, 5 sodium ascorbate, 2 thiourea, 10 MgSO4, and 0.5 CaCl2. Slices were allowed to recover for 45 minutes at 37°C and 45 minutes at room temperature before recordings. During recovery the slices were maintained in a artificial cerebrospinal fluid (ACSF) containing, in mM, 115 NaCl, 2.5 KCl, 1.4 NaH2PO4, 24 NaHCO3, 12.5 glucose, 3 sodium pyruvate, 5 sodium ascorbate, 2 thiourea, 1 MgSO4, and 2.5 CaCl2. For recording, slices were maintained in a standard ACSF solution containing, in mM, 128 NaCl, 2.5 KCl, 1.4 NaH2PO4, 26.2 NaHCO3, 12.2 glucose, 1 MgSO4, and 2.5 CaCl2.

VSDI acquisition

The VSD di-3-ANEPPDHQ (Invitrogen, Thermo Fisher Scientific) was solubilized in 95% ethanol (0.020 mg/μL) and stored at –20°C. Slices were stained with the di-3-ANEPPDHQ (0.1 mg/mL, in ACSF) for 14–16 minutes. Slices were then transferred to a humidified interface chamber (BSC2, Scientific Systems Design), maintained at 30°C for recording.

VSD experiments were completed as previously published (24). In short, excitation light was provided by 7 high-power green LEDs (Luxeon Rebel LXML-PM01-0100, Philips) coupled to a 535 ± 25–nm filter and 565-nm dichroic mirror. A 610-nm longpass filter further isolated the emitted fluorescence. Fluorescence was recorded at 1000 frames per second with a fast video camera with 80 × 80 pixel resolution (NeuroCCD, Redshirt Imaging).

For each condition the perforant pathway and SC pathways were stimulated (Supplemental Figure 1J). Four stimuli were delivered as 0.1-ms pulses at 10 Hz through a bipolar tungsten electrode (ME12206, World Precision Instruments). Pathway stimulus strength was set at the current required to produce a saturating field potential response in the granule cell layer of the DG using a glass electrode pulled to a 2- to 8-MΩ tip and filled with ACSF. Field potential recordings were acquired using an Axoclamp 900A amplifier and pClamp 10 software (Molecular Devices). All recordings were 1.5 seconds long, with a 10-second delay between recordings to allow fluorescence to recover from photobleaching. Thirteen recordings of evoked activity were interleaved with 13 VSDI runs where no stimulus was delivered. Runs without delivered stimuli were used for offline subtraction to correct for any baseline drift over a recording. Simultaneous extracellular field potentials were recorded to further support VSDI findings.

VSDI analysis

Postcollection VSDI analysis was completed using the previously published VSDI toolbox (24). The software facilitates inspection of VSDI data and allows for robust statistical analysis across both spatial and temporal dimensions. Unlike traditional VSDI protocols, which analyze only a small number of user-selected ROIs, this toolbox allows for an unbiased evaluation of the dynamics of the entire hippocampus.

In short, a computational algorithm is used to create an unbiased ROI covering the entire hippocampus for each slice. The fluorescence response in each ROI for each image is calculated. As previously published (24), to compare between and average slices, linear interpolation was used to “stretch” rasters to be the same size. For all studies, a final stretched DG raster size was 22 ROIs, and a final stretched CA proper raster size was 36 ROIs.

Recordings from each condition per slice were averaged. A 2-dimensional raster plot showing the location, time, and fluorescence change for each recording protocol in each slice was generated. In addition to individual rasters for each slice, an average raster plot per condition was generated. The raster plots from different genotypes were compared using a permutation sampling method with n = 1000 permutations. A heatmap showing regions of the network with statistically significant (P < 0.05) differences was created. The average regional fluorescence response (DG, hilus, CA3, CA1) was calculated for each slice. This allows for further statistical comparisons of total and peak excitation.

To evaluate correlation of hippocampal network activity over space throughout the CA proper regions, a Pearson correlation coefficient matrix comparing fluorescence change in each ROI with every other ROI was calculated in Matlab (MathWorks, version 2018a, corr function), and a correlation map was created. Regional correlations were also compared by averaging the correlation coefficients from the hilus (ROIs 1–5), CA3 (ROIs 6–18), and CA1 (ROIs 19–36).

Histology

Immunohistochemical analysis of fixed brains was carried out as previously described (54). Briefly, mice were anesthetized with isoflurane and transcardially perfused with saline followed by 4% paraformaldehyde in 0.1 M phosphate buffer (MilliporeSigma), pH 7.4. The brains were removed and postfixed in 4% phosphate-buffered paraformaldehyde at 4°C overnight and then cryoprotected with 30% sucrose buffer, embedded in OCT, and stored at –80°C. Coronal sections (20 μm) were cut using a cryostat (Microm HM 500) and stored at –80°C until staining.

For measurement of autofluorescence, unstained immunofluorescence images of the DG region were acquired using a Leica DMR microscope coupled with a CoolSNAP camera (Leica Microsystems). For NeuN staining, sections were washed with PBS, permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100 in PBS for 7 minutes, incubated in 3% H2O2/10% methanol in PBS for 5 minutes, washed again with PBS 3 times, and blocked in 10% normal goat serum in PBS, all at room temperature. Sections were incubated with an antibody against NeuN (MilliporeSigma MAB377, 1:100) at 4°C overnight. To detect the primary antibody, sections were incubated with a biotinylated goat antimouse secondary antibody (Jackson ImmunoResearch 115-065-062, 1:500) at room temperature for 30 minutes. After PBS washes, sections were incubated in avidin-biotin complex (Vectastain, Vector Laboratories) at room temperature for 1 hour. Slices were incubated in DAB solution for visualization. Images of the hippocampus, original magnification ×10, were acquired and stitched. All images were analyzed using ImageJ (NIH). ROIs covering the entire DG, CA3, or CA1 regions were drawn, and the mean integral density of the region was calculated. Staining intensity from n = 4 animals per condition was measured.

EEG acquisition

Recording electrodes were constructed by connecting 6 cortical leads, 1 reference lead placed over the cerebellum, 1 ground (0.004 inches, formvar-coated silver wire, California Fine Wire), and 2 hippocampal leads (0.005 inches bare, 0.008 inches coated, stainless steel wire, AM-Systems) to a micro connector (Omnetics). Electrodes were placed while mice were under inhaled isoflurane anesthesia after premedication with intramuscular injection of ketamine/xylazine. Electrodes were implanted using the following stereotaxic coordinates (measurements relative to bregma): bilateral motor cortices: 0.5 mm rostral, 1 mm lateral, and 0.6 mm deep; bilateral barrel field cortices: 0.7 mm caudal, 3 mm lateral, and 0.6 mm deep; bilateral visual cortex: 3.5 mm caudal, 2 mm lateral, and 0.6 mm deep; and bilateral hippocampus (CA1 region): 2.2 mm caudal, 2 mm lateral, and 1.7 mm deep. The cerebellar reference lead was implanted posterior to lambda. The ground wire was wrapped tightly around a 1/8-inch self-tap screw (Precision Screws and Parts), which was inserted into the skull rostral to the motor cortex leads. A second screw was inserted caudal to lambda to help secure the recording headcap. The recording electrodes were secured with dental cement, and the animal was allowed to recover for at least 18 hours before recording.

For recording sessions, the implanted connector was attached to a lightweight RHD2000 low-noise amplifier chip (Intan Technologies), which was connected to a data acquisition board by a lightweight cable, which allowed the animal to move freely around the recording cage. Electrophysiologic data was acquired at 2 kHz using the Intan RHD2000 Recording System Software (http://intantech.com/downloads.html). Mice were recorded for at least 12 consecutive hours per animal. Recordings were saved in 30-minute files.

Fourteen animals per genotype group (WT and CLN3–/–) were recorded. Each genotype group contained five 6-month-old, five 11-month-old, and four 18-month-old animals. Twenty-four 30-minute recording periods per animal were analyzed.

EEG analysis

All analysis was completed in MATLAB with software designed by members of the laboratory (55). Code is available at https://github.com/ahrensnicklasr/EEG-analysis-JCI-Insight Steps of analysis included the following.

Detection of poor-quality recording channels.

Before analysis, each recording channel for each 30-minute recording period was analyzed using an automated artifact detector. Detection of a bad or noisy recording channel was completed by calculating the average of the root mean squared amplitude and skew of the voltage for each second of the recording. Although several EEG features and algorithms can be used for artifact detection, many approaches use these 2 features (56). Channels were excluded from further analysis if they had a root mean squared amplitude less than 30 μV or more than 200 μV or a skew greater than 0.4. These parameters led to an accuracy of 90% on a test data set as compared to an expert physician trained to evaluate EEGs.

Spike detection.

Spikes were detected using a spike detector algorithm designed to detect voltage deflections that were greater than 5 standard deviations above the mean with a full width at half maximum amplitude of 5–200 ms. Spikes were eliminated if they occurred within 10 s of a deflection found to be an artifact (i.e., it had a half width outside the 5- to 200-ms range). This algorithm was shown to have an accuracy of 74% on a training data set, as compared to an expert physician trained to evaluate EEGs (consistent with accuracy rates of previously reported spike detector algorithms; ref. 57). For spike quantification 12 hours of recording were evaluated for each animal.

Power analysis.

To analyze mutation-induced differences in background EEG frequency composition, recordings were divided into 5-second epochs for power analysis. Epochs containing large amplitude artifacts, likely because of movement (defined as a peak Z-score of the root mean squared voltage amplitude greater than 3), were excluded from frequency analysis. Fast Fourier transform analysis was then completed on artifact-free epochs. Quantification of the power in each of the major EEG frequency bands (delta 0.1–4.0 Hz, theta 4–8 Hz, alpha 8–13 Hz, beta 13–25 Hz, and gamma 25–50 Hz) was completed. Power in each band was normalized to total power. Power in each band across all epochs was averaged. The epoch-by-epoch distribution of delta and beta power was also calculated. Finally, the proportion of 30-minute recording periods with both high average beta activity (beta power Z-score greater than 1 standard deviation above the mean) and spikes were calculated.

SWR analysis.

To detect hippocampal high-frequency oscillations during low theta periods, i.e., hippocampal SWRs, data were analyzed using methods adapted from published studies (33). Recordings from hippocampal channels were bandpass filtered at 1–300 Hz, divided into 5-second epochs, and the root mean squared voltage for each epoch was calculated. Epochs with a root mean square voltage Z-score greater than 2 were eliminated to remove epochs with high-voltage artifacts that could obscure SWRs, which are brief (50–100 ms) events.

The artifact-free recording was bandpass filtered to capture activity in the delta, theta, beta, and ripple (150–250 Hz) frequency ranges. To identify low theta time points, the theta ratio was calculated for each time point by dividing the envelope amplitude of the theta-filtered signal by the sum of the envelope amplitude of the beta and delta signals. Low theta was defined as a point where the theta ratio Z-score was less than –0.5. Time points with possible ripple activity were identified when the envelope amplitude of the ripple-filtered signal had a Z-score greater than 4.

True SWR periods were identified using a 30-ms moving window; if 10 out of 30 milliseconds in the window had both a low theta Z-score (<–0.5) and a high ripple frequency Z-score (>4), a ripple was identified. Discrete ripple events had to be separated by at least 5 seconds. The number of ripple events per 30-minute recording period was calculated.

To evaluate features of the SWRs, the 1 second surrounding the ripple peak was captured. Using a Z-scored spectrogram calculated for the entire artifact-free recording, the peak and average Z-scored powers in each of the major frequency bands were calculated for 100-ms bins covering the 1-second ripple period. The Z-scored amplitude of the ripple-filtered voltage signal during the 1-second period was used to calculate ripple duration. Ripple start time was defined as the time when the Z-score of the ripple-filtered signal first reached a Z-score of 3, and end time was marked when the Z-score returned to less than 2.

Statistics

All statistical analysis of VSDI rasters was completed using the VSDI toolbox (24) (code available at https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0108686). For summary statistics of regions or groups, GraphPad Prism was also used. In graphs, data are expressed as mean ± SEM. The statistical significance of the observed differences between 2 groups was assessed by 2-tailed t test (for normally distributed data) or Mann-Whitney U test (for non-normally distributed data). For data sets with more than 1 time point or group, 1-way or 2-way ANOVA followed by Holm-Šídák or Tukey’s multiple-comparisons test was completed as detailed in each figure legend. Results were considered significant when P < 0.05.

Study approval

All animal protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia.

Author contributions

RCAN, LT, BLD, and EDM designed research studies. RCAN performed statistical analysis. RCAN, AFH, and EL conducted experiments. RCAN, BLD, and EDM analyzed data. RCAN wrote the manuscript. RCAN, LT, AFH, EL, ASC, BLD, and EDM revised the manuscript.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Almedia McCoy and Donald Joseph for their technical advice and guidance. This work was supported by NCL Stiftung Research Award, Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia Research Institute, and NIH/ National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS) K08 NS105865-02 to RCAN; NS084424, NS068099, and Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia Research Institute to BLD; and NIH/NINDS R01 NS082761-01A1 to EDM.

Version 1. 10/01/2019

In-Press Preview

Version 2. 11/01/2019

Electronic publication

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: BLD is a founder of Spark Therapeutics and Talee Bio and is on the senior advisory board of Intellia Therapeutics, Sarepta Therapeutics, Homology Medicines, Prevail Therapeutics, Axovant, and Panorama Medicines.

Copyright: © 2019, American Society for Clinical Investigation.

Reference information: JCI Insight. 2019;4(21):e131961.https://doi.org/10.1172/jci.insight.131961.

Contributor Information

Rebecca C. Ahrens-Nicklas, Email: ahrensnicklasr@email.chop.edu.

Luis Tecedor, Email: tecedorl@email.chop.edu.

Elena Lysenko, Email: lysenkoe@email.chop.edu.

Akiva S. Cohen, Email: cohena@email.chop.edu.

Beverly L. Davidson, Email: davidsonbl@email.chop.edu.

Eric D. Marsh, Email: marshe@email.chop.edu.

References

- 1.Kingma SD, Bodamer OA, Wijburg FA. Epidemiology and diagnosis of lysosomal storage disorders; challenges of screening. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2015;29(2):145–157. doi: 10.1016/j.beem.2014.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Platt FM. Emptying the stores: lysosomal diseases and therapeutic strategies. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2018;17(2):133–150. doi: 10.1038/nrd.2017.214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fiorenza MT, Moro E, Erickson RP. The pathogenesis of lysosomal storage disorders: beyond the engorgement of lysosomes to abnormal development and neuroinflammation. Hum Mol Genet. 2018;27(R2):R119–R129. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddy155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Haltia M. The neuronal ceroid-lipofuscinoses. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2003;62(1):1–13. doi: 10.1093/jnen/62.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rider JA, Rider DL. Batten disease: past, present, and future. Am J Med Genet Suppl. 1988;5:21–26. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.1320310606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Adams HR, Mink JW, University of Rochester Batten Center Study Group Neurobehavioral features and natural history of juvenile neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis (Batten disease) J Child Neurol. 2013;28(9):1128–1136. doi: 10.1177/0883073813494813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Augustine EF, et al. Standardized assessment of seizures in patients with juvenile neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2015;57(4):366–371. doi: 10.1111/dmcn.12634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Isolation of a novel gene underlying Batten disease, CLN3. The International Batten Disease Consortium. Cell. 1995;82(6):949–957. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90274-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cárcel-Trullols J, Kovács AD, Pearce DA. Cell biology of the NCL proteins: what they do and don’t do. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2015;1852(10 Pt B):2242–2255. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2015.04.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Eliason SL, et al. A knock-in reporter model of Batten disease. J Neurosci. 2007;27(37):9826–9834. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1710-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Grünewald B, et al. Defective synaptic transmission causes disease signs in a mouse model of juvenile neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis. Elife. 2017;6:e28685. doi: 10.7554/eLife.28685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tyynelä J, Cooper JD, Khan MN, Shemilts SJ, Haltia M. Hippocampal pathology in the human neuronal ceroid-lipofuscinoses: distinct patterns of storage deposition, neurodegeneration and glial activation. Brain Pathol. 2004;14(4):349–357. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3639.2004.tb00077.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mitchison HM, Lim MJ, Cooper JD. Selectivity and types of cell death in the neuronal ceroid lipofuscinoses. Brain Pathol. 2004;14(1):86–96. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3639.2004.tb00502.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Haltia M, Herva R, Suopanki J, Baumann M, Tyynelä J. Hippocampal lesions in the neuronal ceroid lipofuscinoses. Eur J Paediatr Neurol. 2001;5 Suppl A:209–211. doi: 10.1053/eipn.2000.0464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wendt KD, Lei B, Schachtman TR, Tullis GE, Ibe ME, Katz ML. Behavioral assessment in mouse models of neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis using a light-cued T-maze. Behav Brain Res. 2005;161(2):175–182. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2005.02.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Burkovetskaya M, Karpuk N, Kielian T. Age-dependent alterations in neuronal activity in the hippocampus and visual cortex in a mouse model of Juvenile Neuronal Ceroid Lipofuscinosis (CLN3) Neurobiol Dis. 2017;100:19–29. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2016.12.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Whitley C, et al. Final results of the first-in-human open-label study of intravenous SBC-103 in children with mucopolysaccharidosis type IIIB. Mol Genet Metab. 2018;123(2):S147–S148. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2018.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Olivier S, Le Meur A, Deiva K. Five years of clinical data in a direct to CNS gene therapy trial to address the severe lethal neurological manifestations of MPS IIIA. Mol Genet Metab. 2018;123(2):S110 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sevin C, et al. Intracerebral gene therapy in children with metachromatic leukodystrophy: results of a phase I/II trial. Mol Genet Metab. 2018;123(2):S129 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Muenzer J, et al. Efficacy and safety of intrathecal idursulfase in pediatric patients with mucopolysaccharidosis type II and early cognitive impairment: design and methods of a controlled, randomized, phase II/III multicenter study. Mol Genet Metab. 2018;123(2):S99–S100. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wijburg FA, et al. Intrathecal heparan-N-sulfatase in patients with Sanfilippo syndrome type A: a phase IIb randomized trial. Mol Genet Metab. 2019;126(2):121–130. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2018.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cotman SL, et al. Cln3(Deltaex7/8) knock-in mice with the common JNCL mutation exhibit progressive neurologic disease that begins before birth. Hum Mol Genet. 2002;11(22):2709–2721. doi: 10.1093/hmg/11.22.2709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ding SL, Tecedor L, Stein CS, Davidson BL. A knock-in reporter mouse model for Batten disease reveals predominant expression of Cln3 in visual, limbic and subcortical motor structures. Neurobiol Dis. 2011;41(2):237–248. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2010.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bourgeois EB, Johnson BN, McCoy AJ, Trippa L, Cohen AS, Marsh ED. A toolbox for spatiotemporal analysis of voltage-sensitive dye imaging data in brain slices. PLoS One. 2014;9(9):e108686. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0108686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schultz ML, Tecedor L, Lysenko E, Ramachandran S, Stein CS, Davidson BL. Modulating membrane fluidity corrects Batten disease phenotypes in vitro and in vivo. Neurobiol Dis. 2018;115:182–193. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2018.04.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Burkovetskaya M, et al. Evidence for aberrant astrocyte hemichannel activity in Juvenile Neuronal Ceroid Lipofuscinosis (JNCL) PLoS One. 2014;9(4):e95023. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0095023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Díaz GF, et al. Generalized background qEEG abnormalities in localized symptomatic epilepsy. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol. 1998;106(6):501–507. doi: 10.1016/S0013-4694(98)00026-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Eschenko O, Ramadan W, Mölle M, Born J, Sara SJ. Sustained increase in hippocampal sharp-wave ripple activity during slow-wave sleep after learning. Learn Mem. 2008;15(4):222–228. doi: 10.1101/lm.726008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.van de Ven GM, Trouche S, McNamara CG, Allen K, Dupret D. Hippocampal offline reactivation consolidates recently formed cell assembly patterns during sharp wave-ripples. Neuron. 2016;92(5):968–974. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2016.10.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jadhav SP, Kemere C, German PW, Frank LM. Awake hippocampal sharp-wave ripples support spatial memory. Science. 2012;336(6087):1454–1458. doi: 10.1126/science.1217230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cayzac S, Mons N, Ginguay A, Allinquant B, Jeantet Y, Cho YH. Altered hippocampal information coding and network synchrony in APP-PS1 mice. Neurobiol Aging. 2015;36(12):3200–3213. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2015.08.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gillespie AK, et al. Apolipoprotein E4 causes age-dependent disruption of slow gamma oscillations during hippocampal sharp-wave ripples. Neuron. 2016;90(4):740–751. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2016.04.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Iaccarino HF, et al. Gamma frequency entrainment attenuates amyloid load and modifies microglia. Nature. 2016;540(7632):230–235. doi: 10.1038/nature20587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Carr MF, Karlsson MP, Frank LM. Transient slow gamma synchrony underlies hippocampal memory replay. Neuron. 2012;75(4):700–713. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.06.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pfeiffer BE, Foster DJ. Autoassociative dynamics in the generation of sequences of hippocampal place cells. Science. 2015;349(6244):180–183. doi: 10.1126/science.aaa9633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Csicsvari J, Jamieson B, Wise KD, Buzsáki G. Mechanisms of gamma oscillations in the hippocampus of the behaving rat. Neuron. 2003;37(2):311–322. doi: 10.1016/S0896-6273(02)01169-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fernández-Ruiz A, Makarov VA, Benito N, Herreras O. Schaffer-specific local field potentials reflect discrete excitatory events at gamma frequency that may fire postsynaptic hippocampal CA1 units. J Neurosci. 2012;32(15):5165–5176. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4499-11.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schomburg EW, et al. Theta phase segregation of input-specific gamma patterns in entorhinal-hippocampal networks. Neuron. 2014;84(2):470–485. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2014.08.051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Oliva A, Fernández-Ruiz A, Fermino de Oliveira E, Buzsáki G. Origin of gamma frequency power during hippocampal sharp-wave ripples. Cell Rep. 2018;25(7):1693–1700.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2018.10.066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Beck M. Treatment strategies for lysosomal storage disorders. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2018;60(1):13–18. doi: 10.1111/dmcn.13600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schulz A, et al. Study of Intraventricular cerliponase alfa for CLN2 disease. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(20):1898–1907. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1712649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.El-Hassar L, Esclapez M, Bernard C. Hyperexcitability of the CA1 hippocampal region during epileptogenesis. Epilepsia. 2007;48 Suppl 5:131–139. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2007.01301.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Greene ND, Lythgoe MF, Thomas DL, Nussbaum RL, Bernard DJ, Mitchison HM. High resolution MRI reveals global changes in brains of Cln3 mutant mice. Eur J Paediatr Neurol. 2001;5(Suppl A):103–107. doi: 10.1053/ejpn.2000.0444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Timm D, et al. Searching for novel biomarkers using a mouse model of CLN3-Batten disease. PLoS One. 2018;13(8):e0201470. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0201470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hao S, et al. Forniceal deep brain stimulation rescues hippocampal memory in Rett syndrome mice. Nature. 2015;526(7573):430–434. doi: 10.1038/nature15694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Xia F, et al. entorhinal cortical deep brain stimulation rescues memory deficits in both young and old mice genetically engineered to model Alzheimer’s disease. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2017;42(13):2493–2503. doi: 10.1038/npp.2017.100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Perusini JN, et al. Optogenetic stimulation of dentate gyrus engrams restores memory in Alzheimer’s disease mice. Hippocampus. 2017;27(10):1110–1122. doi: 10.1002/hipo.22756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pohodich AE, et al. Forniceal deep brain stimulation induces gene expression and splicing changes that promote neurogenesis and plasticity. Elife. 2018;7:e34031. doi: 10.7554/eLife.34031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Xiong G, Metheny H, Johnson BN, Cohen AS. A comparison of different slicing planes in preservation of major hippocampal pathway fibers in the mouse. Front Neuroanat. 2017;11:107. doi: 10.3389/fnana.2017.00107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rafiq A, DeLorenzo RJ, Coulter DA. Generation and propagation of epileptiform discharges in a combined entorhinal cortex/hippocampal slice. J Neurophysiol. 1993;70(5):1962–1974. doi: 10.1152/jn.1993.70.5.1962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Jones RS, Heinemann U. Synaptic and intrinsic responses of medical entorhinal cortical cells in normal and magnesium-free medium in vitro. J Neurophysiol. 1988;59(5):1476–1496. doi: 10.1152/jn.1988.59.5.1476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Stanton PK, Jones RS, Mody I, Heinemann U. Epileptiform activity induced by lowering extracellular [Mg2+] in combined hippocampal-entorhinal cortex slices: modulation by receptors for norepinephrine and N-methyl-D-aspartate. Epilepsy Res. 1987;1(1):53–62. doi: 10.1016/0920-1211(87)90051-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Walther H, Lambert JD, Jones RS, Heinemann U, Hamon B. Epileptiform activity in combined slices of the hippocampus, subiculum and entorhinal cortex during perfusion with low magnesium medium. Neurosci Lett. 1986;69(2):156–161. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(86)90595-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Marsh E, et al. Targeted loss of Arx results in a developmental epilepsy mouse model and recapitulates the human phenotype in heterozygous females. Brain. 2009;132(Pt 6):1563–1576. doi: 10.1093/brain/awp107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Yun S, et al. Stimulation of entorhinal cortex-dentate gyrus circuitry is antidepressive. Nat Med. 2018;24(5):658–666. doi: 10.1038/s41591-018-0002-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Daly I, et al. What does clean EEG look like? Conf Proc IEEE Eng Med Biol Soc. 2012;2012:3963–3966. doi: 10.1109/EMBC.2012.6346834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wilson SB, Emerson R. Spike detection: a review and comparison of algorithms. Clin Neurophysiol. 2002;113(12):1873–1881. doi: 10.1016/S1388-2457(02)00297-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.