SUMMARY

BACKGROUND:

We describe the outcomes of a program in which antiretroviral therapy (ART) is offered to human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infected patients in South Africa admitted with tuberculosis (TB) or other opportunistic infection (OI) as part of in-patient care.

METHODS:

Patients admitted with HIV and concurrent TB or other OI were initiated on early in-patient ART. The primary and secondary endpoints were respectively 24-week mortality and 24-week virologic suppression. Multivariable logistic regression modeling explored the associations between baseline (i.e., pre-hospital discharge) characteristics and mortality at 24 weeks.

RESULTS:

A total of 382 patients were prospectively enrolled (48% women, median age 37 years, median CD4 count 33 cells/mm3). Acute OIs were pulmonary TB, 39%; extra-pulmonary TB, 25%; cryptococcal meningitis (CM), 10%; and chronic diarrhea, 9%. The median time from admission to ART initiation was 14 days (range 4–32, IQR 11–18). At 24 weeks of follow-up, as-treated and intention-to-treat virologic suppression were respectively 57% and 93%. Median change in CD4 cell count was +100 cells/mm3, overall 24-week mortality was 25% and loss to follow-up, 5%. Excess mortality was not observed among patients with CM who initiated early ART. A longer interval between admission and ART was associated with mortality (>21 days vs. <21 days after admission OR 2.1, 95%CI 1.2–4.0, P = 0.016).

CONCLUSIONS:

For HIV-infected in-patients with TB or an acquired immune-deficiency syndrome defining OI, we demonstrate the operational feasibility of early ART initiation in in-patients.

Keywords: resource-limited settings, antiviral therapy, operational research

RÉSUMÉ

CONTEXTE:

Nous décrivons les résultats d’un programme en Afrique du Sud où l’on offre aux patients admis pour tuberculose (TB) ou d’autres infections opportunistes (OI) et infectés par le virus de l’immunodéficience humaine (VIH), un traitement antirétroviral (ART) comme élément des soins hospitaliers.

MÉTHODES:

On a mis en route une ART précoce chez les patients hospitalisés pour VIH et TB ou autres OI simultanées. Les résultats primaires et secondaires ont été respectivement la mortalité à 24 semaines et la négativation virologique à 24 semaines. On a exploré grâce à une modélisation de régression logistique multivariée l’association entre les caractéristiques de départ (c’est à dire préalables à la sortie de l’hôpital) et la mortalité à la 24ème semaine.

RÉSULTATS:

On a recruté de manière prospective 382 patients (48% de femmes ; âge médian, 37 ans ; décompte médian des cellules CD4 33 cellules/mm3). Les OI aiguës ont été la TB pulmonaire (39%), la TB extra-pulmonaire (25%), la méningite à cryptocoques (CM ; 10%) et la diarrhée chronique (9%). La durée médiane entre l’admission et la mise en route de l’ART a été de 14 jours (extrêmes 4–32 ; IQR 11–18). A 24 semaines de suivi, la négativation virologique a été respectivement de 57% pour les patients traités et de 93% selon la méthode intention-to-treat (intention à traiter). La modification médiane des décomptes de cellules CD4 a été de +100 cellules/mm3 ; la mortalité globale à 24 semaines a été de 25% et la perte de suivi de 5%. Un excès de mortalité n’a pas été observé chez les patients atteints de CM qui avaient commencé précocement l’ART. Un intervalle plus long entre l’admission et l’ART a été en association avec la mortalité (>21 jours comparés à <21 jours après l’admission OR 2,1 ; IC95% 1,2–4,0 ; P = 0,016).

CONCLUSIONS:

Chez les patients infectés par le VIH et atteints de TB ou d’une OI définissant le syndrome de l’immunodéficience acquise, nous avons démontré la faisabilité opérationnelle d’une mise en route précoce de l’ART chez les patients hospitalisés.

RESUMEN

MARCO DE REFERENCIA:

En el presente estudio se describieron los desenlaces clínicos de un programa de suministro del tratamiento antirretrovírico (ART) a los pacientes infectados por el virus de la inmunodeficiencia humana (VIH), que se hospitalizaban por la tuberculosis (TB) u otras infecciones oportunistas (OI), como parte del tratamiento intrahospitalario en Suráfrica.

MÉTODO:

En todos los pacientes hospitalizados con infección por el VIH que presentaban en forma simultánea TB u otra OI se inició un ART precoz intrahospitalario. El principal criterio de valoración fue la mortalidad a las 24 semanas y el criterio secundario fue la supresión del virus a las 24 semanas. Mediante un modelo de regresión logística multifactorial se analizaron las asociaciones entre las características de base (es decir antes de la alta hospitalaria) y la mortalidad a las 24 semanas.

RESULTADOS:

Se incluyeron en forma prospectiva 382 pacientes (48% mujeres; la mediana de la edad fue 37 años; la mediana del recuento de linfocitos CD4 fue 33 células/mm3). Las OI agudas que se observaron fueron: la TB pulmonar 39%; la TB extrapulmonar 25%; la meningitis por criptococo (CM) 10%; y la diarrea crónica 9%. La mediana del lapso entre la admisión y el comienzo del ART fue 14 días (entre 4 y 32 días; IQR 11 a 18). La supresión vírica a las 24 semanas de seguimiento en el análisis por tratamiento administrado fue 57% y en el análisis por intención de tratar fue 93%. La mediana de la modificación del recuento de células CD4 fue +100 células/mm3; globalmente, la mortalidad a las 24 semanas fue 25% y la pérdida durante el seguimiento fue de 5%. No se observó un exceso de mortalidad en los pacientes con CM que comenzaron el ART precoz. El factor asociado con la mortalidad fue un intervalo más prolongado entre la hospitalización y el comienzo del ART (>21 días comparado con <21 días después del ingreso, OR 2,1; IC95% 1,2 a 4,0; P = 0,016).

CONCLUSIÓN:

Se demostró la factibilidad operativa de iniciar un ART temprano en los pacientes infectados por el VIH que se hospitalizan por TB o por una de las OI que definen el síndrome de inmunodeficiencia adquirida.

A SUBSTANTIAL PROPORTION of patients with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection in South Africa present initially for HIV care as in-patients with tuberculosis (TB) or other acute opportunistic infection (OI) and advanced HIV disease, typically with a CD4 cell count <100 cells/mm3. Under routine conditions, short-term antiretroviral therapy (ART) uptake after hospitalization with an acute OI is low and mortality is high. A previous study by this research group showed that in South Africa, 6 months after hospital discharge, more than half of the patients had not initiated ART. Moreover, patients with the most advanced disease (CD4 count <50 cells/mm3) were least likely to initiate ART.1 Following discharge from hospital, HIV-infected patients with TB or other acute OI in resource-limited settings face several potential barriers to timely initiation of ART, potentially placing them at increased risk for a poor outcome. These barriers include the loss of functional capacity associated with hospitalization, as well as structural hurdles to engaging in the often lengthy pre-ART readiness-assessment processes.2

Additional mechanisms are needed to expedite ART access for patients presenting as in-patients with advanced HIV disease.3 The strategy of initiating ART early during the treatment of acute OI is supported by several studies. For example, the AIDS Clinical Trial Group (ACTG) Study 5164 showed that, compared to deferring ART initiation to a later time point, a significant reduction in mortality could be achieved by initiating ART early during hospitalization, within 14 days of acute OI.4 Two recent studies suggest a considerable mortality benefit associated with early initiation of ART in patients with HIV and TB, with the mortality benefit concentrated among patients with a CD4 cell count of <50 cells/mm3.5–7 However, it has been underappreciated that a large proportion of such patients present to the in-patient unit as acutely ill, non-ambulatory patients, and documented experiences from routine in-patient settings involving the initiation of early ART among in-patients with acute OI are few.

The initiation of early ART in the setting of TB or other acute OI requires medical, psychosocial and nursing resources. Outcomes have not been uniformly positive. A cautionary note was struck by a study in Zimbabwe, which described an alarmingly high mortality rate (88%) associated with very rapid ART initiation (<72 h of diagnosis) with cryptococcal meningitis.8 However, this study was criticized for its small sample size, potential suboptimal patient management (including failure to manage intracranial pressure) and an inability to fully explain causes of death.9 Undoubtedly, patients with advanced HIV and concurrent OI present challenges to clinicians when initiating ART because of potential drug drug interactions, drug toxicities, immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome (IRIS) and high initial pill burden.8

It is to be noted that the South Africa Department of Health has published revised ART guidelines specifying that ART should be offered within 2 weeks of OI diagnosis in recently hospitalized adults.10 The current study describes the feasibility and effectiveness under routine program conditions of early supervised in-patient ART initiation in a high-prevalence HIV context in the setting of TB and other treatable OIs.

METHODS

McCord Hospital is a state-aided, 166-bed hospital in central Durban, where approximately 2400 patients with acquired immune-deficiency syndrome (AIDS) related illnesses are admitted to the acute care wards each year. HIV-infected patients with acute OI comprise approximately half of the hospital admissions on the medical side. As part of routine in-p atient care, HIV testing and CD4 count measurement are performed during in-patient stay.

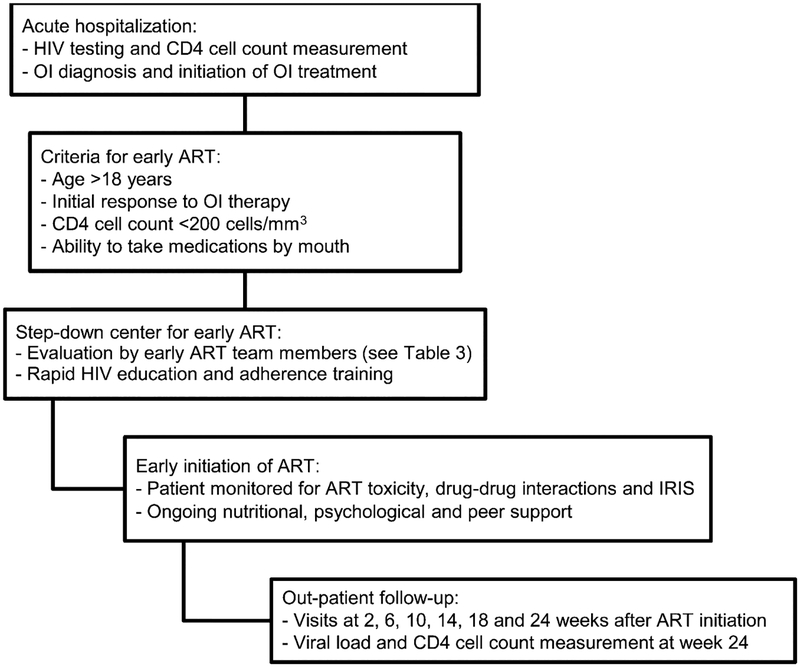

During the study period (November 2006–August 2007), HIV-infected, ART-naïve patients hospitalized at McCord Hospital with acute OI were consecutively enrolled for initiation of early ART as in-patients in a step-down center after initial OI diagnosis and treatment. Patients were required to self-finance the cost of additional days of hospitalization associated with the early ART program. Patients were initiated on the standard South African first-line ART regimen consisting of stavudine (d4T), lamivudine (3TC) and efavirenz (EFV). Clinicians were encouraged to initiate ART within 2 weeks of OI treatment. After discharge, patients were followed for 24 weeks after initiation of ART, which included clinic follow-up at the McCord Hospital Sinikithemba Clinic at weeks 2, 6, 10, 14, 18 and 24 after the initiation of ART (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Evaluation and referral for early ART initiation in South Africa. HIV = human immunodeficiency virus; OI = opportunistic infection; ART = antiretroviral therapy; IRIS = immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome.

Enrollment criteria

Patients were HIV-infected ART-naïve in-patients aged ⩾18 years with a CD4 cell count of <200 cells/mm3 who were admitted to McCord Hospital with an acute OI. Exclusion criteria were 1) patients aged <18 years, 2) patients unwilling to disclose their HIV status to a treatment supporter, 3) residence outside of the greater Durban area or eThekwini Municipality, 4) patients unable to swallow pills, or 5) presence of an AIDS-defining condition not amenable to medical or surgical therapy (Figure 1).

Data collection

Clinical, demographic and laboratory data were collected during admission, and clinical outcomeswere collected at month six. Data collected at admission and during ART initiation included age, sex, date of HIV diagnosis, CD4 cell count, hemoglobin and adverse drug events. Six months after hospital discharge, data collected included vital status, use of ART, other new clinical events (hospitalizations and OI), CD4 cell count and viral load.

Siyaphila center

Early ART was initiated at the Siyaphila center, a step-down facility associated with McCord Hospital, initially created to meet the need for palliative care for patients with AIDS. The name Siyaphila translates to ‘we are well’ in the Zulu language. The Siyaphila center is a 42-bed medical care facility where clinical care involves an interdisciplinary team consisting of a physician, a nurse, an adherence counselor, a psychologist, a social worker and a physiotherapist.11 Patients who received early ART were not excluded from interdisciplinary palliative care to control and alleviate symptoms and maximize quality of life.12 Patients who deteriorated clinically despite initiation of ART and OI-directed treatment were offered the terminal care aspect of palliative care.

OI definitions

OIs were diagnosed according to 2006 World Health Organization (WHO) Adult and Adolescent ART guidelines.13 Clinicians had access to chest radiography, acid-fast staining and mycobacterial culture, in addition to cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) studies, including CSF cell count, CSF protein, CSF glucose, CSF cryptococcal antigen testing and india ink staining. They could selectively obtain Toxoplasmosis gondii serology and brain computed tomography.

Study design

We conducted retrospective cohort analysis among consecutive patients who initiated ART as in-patients after OI diagnosis. The primary outcome was mortality at 24 weeks, and the secondary outcome was virologic suppression at 24 weeks. In this operation research study, we were unable to estimate precise rates of IRIS.

Statistical analysis

Multivariable logistic regression modeling explored the associations between baseline (i.e., pre-hospital discharge) characteristics and mortality at 24 weeks. All covariates were initially fit alone (univariate models), and covariates found to be significantly associated with 24-week mortality (independent variable) were fit in a multivariable model. Logistic regression was chosen instead of Cox regression for testing the association between covariates and the mortality outcome due to incomplete data on event times and the limited time period of study follow-up. Logistic regression analyses were performed using SPSS (Version 19.0, Statistical Package for the Social Sciences Inc, Chicago, IL, USA).

Categorical variables were compared using χ2 tests, and means were compared with t-tests. All tests of statistical significance were two-sided, without adjustment for multiple testing.

Ethical approval

The study was approved by the McCord Hospital Research Ethics Committee in Durban, South Africa.

RESULTS

Between November 2006 and August 2007, among 1182 patients eligible for early in-patient ART, 382 (32%) patients with acute OI initiated early in-patient ART (Figure 2). Among the 382 patients, 48% were women, the median age was 37 years, and the median CD4 cell count was 33 cells/mm3 (interquartile range [IQR] 12–78; Table 1); 62% of the patients had a CD4 count < 50 cells/mm3.

Figure 2.

HIV-infected patients with acute OI referred for early ART after OI in South Africa. ART = antiretroviral therapy; HIV = human immunodeficiency virus; OI = opportunistic infection.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of patients at hospital admission with acute OI in South Africa, N = 382

| Characteristics | n (%) or median [IQR] |

|---|---|

| Age, years | 37 [31–44] |

| Females | 184 (48) |

| Baseline CD4 count, cells/μl* | 33 [12–78] |

| Baseline CD4 cell count category, cells/mm3 | |

| 0–49 | 224 (62) |

| 50–99 | 65 (18) |

| 100–199 | 52 (15) |

| 200–349 | 18 (5) |

| Acute OI | |

| Pulmonary tuberculosis | 147 (39) |

| Extra-pulmonary tuberculosis (including meningitis) | 96 (25) |

| Cryptococcal meningitis | 40 (10) |

| Chronic diarrhea (>14 days) | 35 (9) |

| Bacterial pneumonia | 11 (3) |

| Toxoplasmosis gondii | 9 (2) |

| Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia | 5 (1) |

| HIV-associated kidney disease | 4 (1) |

| Other reason for admission in an ART-eligible patient† | 20 (5) |

| Undiagnosed Ol‡ | 15 (3) |

Twenty-three patients did not have baseline CD4 cell count measured.

Other reasons for admission were: drug-induced hepatitis (n = 5), esophageal candidiasis (n = 2), Kaposi’s sarcoma (n = 1), dysentery (n = 1), severe anemia (n = 1), liver abscess (n = 1), HIV dementia (n = 1), hypocalcemia (n = 1), hypoglycemia (n = 1), arrhythmia (n = 1), pressure ulcer (n = 1), diabetes mellitus (n = 1), sepsis (n = 1), deep venous thrombosis (n = 1) and pancreatitis (n =1).

Fifteen patients had an undiagnosed OI on admission.

OI = opportunistic infection; IQR = interquartile range; HIV = human i mmunodeficiency virus; ART = antiretroviral therapy.

TB was the most common OI, observed in 243/382 (64%) patients. Among those with TB, 147 (60%) had pulmonary TB and 96 (40%) had extra-pulmonary TB, including TB meningitis. Other OIs were cryptococcal meningitis (10%), chronic diarrhea (9%), bacterial pneumonia (3%), toxoplasmosis (2%), pneumocystis pneumonia (1%) and HIV-related kidney disease (1%).

The median time from admission to ART initiation was 14 days (IQR 11–18), with a mean of 16.0 days (standard deviation [SD] 7.5). The mean time from admission to ART initiation among patients with baseline cryptococcal meningitis (n = 40, 18.6 days, SD 8.6) was greater than the mean time among patients with other OI (15.7 days, SD 7.6, t = 2.03, P = 0.048). In total, 366/382 (96%) patients commenced the South African first-line ART regimen (d4T, 3TC and EFV), 6 (2%) commenced zidovudine (AZT), 3TC and EFV, 6 (2%) commenced d4T, 3TC and nevirapine (NVP), 2 (0.5%) commenced AZT, 3TC and NVP, and 2 (0.5%) commenced 3TC, d4T and lopinavir/ritonavir.

Total in-patient time was a median of 19 days (IQR 15–26). At 24 weeks, intention-to-treat (missing = failure) and as-treated virologic suppression to <50 copies/ml were respectively 57% and 93%. The median 24-week change in CD4 cell count was +100 cells/mm3 (IQR 48–128). We compared the rate of 24-week virologic suppression among patients in the lowest CD4 strata with all other patients. In as-treated analysis, virologic suppression was achieved by 122/135 (90%) patients with a baseline CD4 cell count of 0–49 cells/mm3, and by 84/86 (98%) patients with a baseline CD4 count of ⩾50 cells/mm3 (P = 0.052).

Over 24 weeks of follow-up, 97/382 (25%) patients died (Table 2). Among this group, 20 (5%) died as in-patients prior to hospital discharge and 77 (20%) died after hospital discharge prior to 24 weeks. Mortality was compared among patients with and those without baseline cryptococcal meningitis compared with other OI. Among patients with cryptococcal meningitis, 8/40 (20%) died by week 24, and among patients with OI other than cryptococcal meningitis 89/245 (26%) died (P = 0.4). Loss to follow-up was observed in 19/382 (5%) patients over the 24 weeks.

Table 2.

Outcomes 24 weeks after immediate ART among patients with an acute OI in South Africa

| Patients (N =382) n (%) or median [IQR] | |

|---|---|

| Timing of ART initiation | |

| Days from admission with OI to ART initiation* | 14 [11–18] |

| Days from admission with OI to ART by category | |

| 0–7 | 15 (4) |

| 8–14 | 181 (47) |

| 15–21 | 105 (26) |

| >21 | 62 (16) |

| Total in-patient days in in-patient care | |

| Days from hospital admission to discharge home | 19 [15–26] |

| ART regimen initiated | |

| d4T+3TC + EFV | 366 (95) |

| d4T+3TC + NVP | 6 (2) |

| AZT+3TC + EFV | 6 (2) |

| Other | 4 (1) |

| 24-week virologic outcomes | |

| ITT viral suppression <400 cells/ml† | 206 (57) |

| AT viral suppression <400 cells/ml‡ | 206 (93) |

| 24-week immunologic outcomes | |

| CD4 count improvement, cells/mm3§ | 100 [48–188] |

| 24-week mortality | |

| Overall mortality | 97 (25) |

| Mortality prior to discharge in the step-down facility | 20/97 |

| Mortality after discharge | 77/97 |

| Among patients who died, days to death | 33 [9–95] |

| 24-week program outcomes | |

| Loss to follow-up | 19 (5) |

| Changed service provider | 19 (5) |

Date of ART initiation unknown for a proportion (n = 19) of patients.

For ITT analysis, patients who died (n = 97), were lost to follow-up (n = 19) or were in care but missing 24-week viral load data were considered unsuppressed (n = 60). Only those who transferred care (n = 19) were excluded.

For the AT analysis, patients who died (n = 97), were lost to follow-up (n = 19), or who were in care but were missing 24-week data (n = 60) or transferred care (n = 19) were excluded.

Excludes patients who died, were lost to follow-up, were missing baseline or 24-week CD4 cell count (n = 23), or who transferred care.

ART = antiretroviral therapy; OI = opportunistic infection; IQR = inter quartile range; d4T = stavudine; 3TC = lamivudine; EFV = efavirenz; NVP = nevirapine; AZT = zidovudine; ITT = intent-to-treat; AT = as-treated.

In exploratory analysis we examined possible risk factors for mortality by 24 weeks. Patients who died within 24 weeks of follow-up were compared with those patients who survived (Table 3). The two groups did not differ by sex, baseline CD4 cell count (dichotomized as 0–49 cells/mm3 and ⩾50 cells/mm3) or by presence of baseline cryptococcal meningitis. In both the univariate and multivariate analyses, a longer interval between hospital admission and ART initiation was independently associated with 24-week mortality (>21 days after admission, odds ratio [OR] 2.1, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.2–4.0, P = 0.016), as was older age, with 24-week mortality being 32% among patients aged >40 years (OR 1.7, 95%CI 1.1–2.8, P = 0.026).

Table 3.

Analysis of factors associated with 24-week mortality after acute OI and early in-patient ART

| n | 24-week mortality n (%) | Univariate OR (95%CI) | Multivariate OR (95%CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All subjects | 382 | 97 (25) | ||

| Sex | ||||

| Female | 184 | 49 (26) | ||

| Male | 198 | 49 (25) | 0.9 (0.6–1.5) | |

| Age, years | ||||

| ≤39 | 234 | 50 (21) | ||

| >40 | 148 | 47 (32) | 1.7 (1.1–2.7) | 1.7 (1.1–2.8) |

| Admitting Ol | ||||

| Other | 342 | 89 (26) | ||

| Cryptococcal meningitis | 40 | 8 (20) | 0.7 (0.3–1.6) | |

| Initial CD4 cell count, cells/μl* | ||||

| 0–49 | 224 | 51 (23) | ||

| ≥50 | 135 | 29 (22) | 0.9 (0.6–1.6) | |

| Days to ART initiation† | ||||

| <21 | 301 | 68 (23) | ||

| ≥21 | 62 | 25 (40) | 2.3 (1.3–4.1) | 2.2 (1.3–4.0)‡ |

Twenty-three patients did not have baseline CD4 cell count measured.

Nineteen patients did not have the date of initial ART recorded.

Significant at P = 0.016.

OI = opportunistic infection; ART = antiretroviral therapy; OR = odds ratio; CI = confidence interval.

DISCUSSION

Although stable HIV-infected out-patients have remained the focus of the roll-out of ART in South Africa, a significant proportion of patients are diagnosed with HIV as in-patients in the setting of an acute OI. We previously showed that patients presenting for care as in-patients with HIV and TB or other acute OI have a very poor trajectory in South Africa, with low ART uptake and high 24-week mortality.1 For this patient group, we demonstrate the operational feasibility of early, supervised in-patient ART initiation with a median time between hospital admission and ART of 14 days, a high on-treatment rate of 24-week virologic suppression, and no evidence of excess mortality in key subgroups, including patients with a baseline CD4 cell count of <50 cells/mm3 or baseline cryptococcal meningitis.

Although overall cohort mortality was 25% by week 24, it is important to note that our patients were clinically advanced in-patients with an active opportunistic infection and a median baseline CD4 cell count of 33 cells/mm3 (Table 2). Among patients who initiated early in-patient ART in this novel program, we examined factors associated with 24-week mortality. Compared to patients beginning ART within 3 weeks of hospital admission, a longer interval between admission and ART initiation was independently associated with 24-week mortality (OR 2.1, 95%CI 1.2–4.0, P = 0.016), suggesting that patients who wait longer for ART are less likely to benefit from the intervention. However, we cannot exclude reverse causation, i.e., patients who were more clinically compromised may have been more likely to experience a delay between admission and ART initiation. Older age was also an independent risk factor for increased 24-week mortality, consistent with previous evidence from South Africa.14

There is currently little evidence to guide the appropriate timing of ART in patients with acute cryptococcal meningitis in resource-limited settings. Furthermore, recent data from Zimbabwe have raised concerns about early ART in the setting of cryptococcal meningitis when ART is initiated within 72 h of diagnosis.7 Our management of cryptococcal meningitis differed in important respects from the Zimbabwe study, in that 1) patients initially received amphotericin B (1 mg/kg/day) instead of fluconazole, 2) intracranial pressure was managed with repeated lumbar puncture, and 3) the median time between admission and ART initiation for patients with cryptococcal meningitis was longer, at 15 days. In our study, the 24-week mortality observed among patients with cryptococcal meningitis who received early, in-patient ART was 20%, which is not significantly higher than the mortality of our overall cohort and is in accordance with clinical trials performed in r esource-rich settings. The ideal strategy for this patient group remains to be defined by randomized clinic trials conducted in sub-Saharan Africa.

Among patients who completed 24 weeks of f ollow-up, virologic suppression was achieved by 93% (at a level of <50 copies/ml), with a regimen consisting of d4T, 3TC and EFV. The high rate of virologic suppression, despite a relatively poorly tolerated regimen containing d4T, provides reassurance given concerns that clinically compromised patients with large pill burdens might have difficulty maintaining a high level of adherence to treatment.

These data have several limitations. We were not able to estimate with precision the rate of IRIS among patients who received early ART. Although we cannot rule out a small impact of serious IRIS events on mortality, our observations among patients in the program suggested a very limited role of IRIS in early morbidity and mortality. Other reports from subS aharan Africa suggest that IRIS events are rarely lifethreatening and should not be considered a reason to delay ART in clinically advanced ART-eligible patients with OI.4–6 In addition, because our prior research showed poor outcomes among patients with acute OI discharged for ART initiation as out-patients, we did not include a control group assigned to routine care. We are therefore unable to show a relative benefit of early in-patient ART initiation compared to routine care in which ART initiation is relegated to the out-patient sector. Another limitation involved the issue of cost. Patients were required to pay for the costs of extended hospitalization, typically of 1–3 weeks’ duration. Although McCord Hospital offered a sliding fee scale, this created a financial barrier for some patients and a potential selection bias. Last, the site of the study, McCord Hospital, includes a semiprivate hospital and ART clinic with adequate human resources and medical resources. The outcomes of in-patient ART initiation at McCord may thus not be replicable in the public sector without additional financial investment. The multidisciplinary health team was a key component in the success of the program, providing crucial support required for the ART preparation and training and support of extremely ill patients (Table 4).

Table 4.

Early ART care team for patients with advanced HIV and acute OI in South Africa

| 1 | Trained HIV counselor |

| Rapid HIV education and ART adherence training | |

| Assistance with disease disclosure and identification of treatment supporter | |

| 2 | Psychologist |

| Identify concurrent mental illness, including acute stress reactions, anxiety, mood disorders and HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders | |

| 3 | Social worker |

| Provide patients with help managing the financial costs of illness, including hospitalization and loss of employment | |

| Discharge planning with emphasis on developing support in the home | |

| 4 | Nurse |

| Patient care and education, medication administration and chart maintenance | |

| 5 | Physician |

| Identify ART start date | |

| Manage drug toxicities and IRIS | |

| Identify need for palliative care | |

| 6 | Dietician |

| Nutritional assessment with focus on patients with a low body mass index, altered mental status or chronic diarrhea |

ART = antiretroviral therapy; HIV = human immunodeficiency virus; OI = opportunistic infection; IRIS = immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome.

For hospitalized patients with advanced HIV disease and TB or other OI, who have been shown under routine conditions to have low ART uptake and poor outcomes when discharged for out-patient ART, the early in-patient ART initiation strategy may offer a critical additional entrance point into care. The experience at McCord Hospital, and at other in-patient ART programs in South Africa, might provide the basis for the development of a broadly adoptable model for in-patient ART initiation in the South African public sector.15,16

References

- 1.Murphy RA, Sunpath H, Taha B, et al. Low uptake of antiretroviral therapy after admission with human immunodeficiency virus and tuberculosis in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 2010; 14: 903–908. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization/Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS/United Nations of International Children’s Emergency Fund. Towards universal access: scaling up priority interventions in the health sector. Progress report April 2007. http//www.who.int/hiv/mediacentre/universal_access_progress_report_en.pdf Accessed February 2012.

- 3.Coovadia A, Venter F. Criteria for expedited antiretroviral initiation and emergency triage. S Afr J HIV Med 2009; 33: 27–28. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zolopa AR, Andersen J, Komarow L, et al. Early antiretroviral therapy reduces aids progression/death in individuals with acute opportunistic infections: a multicenter randomized strategy trial. PLoS ONE 2009; 4: e5575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Havlir D, Ive P, Kendall M, et al. , and A5521 Team. International randomized trial of immediate vs. early ART in HIV+ patients treated for TB: ACTG 5221 STRIDE Study. Boston, MA, USA: 18th Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections, 27 February–2 March, 2011. [Abstract #38] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Abdool Karim SS, Naidoo K, Grobler A, et al. Integration of antiretroviral therapy with tuberculosis treatment. N Engl J Med 2011; 365: 1492–1501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Blanc FX, Sok T, Laureillard D, Borand L, et al. Earlier versus later start of antiretroviral therapy in HIV-infected adults with tuberculosis. N Engl J Med 2011; 365: 1471–1481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Makadzange AT, Ndhlovu CE, Takarinda K, et al. Early versus delayed initiation of antiretroviral therapy for concurrent HIV infection and cryptococcal meningitis in sub-Saharan Africa. Clin Infect Dis 2010; 50: 1532–1538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Grant PM, Aberg JA, Zolopa AR. Concerns regarding a randomized study of the timing of antiretroviral therapy in Zimbabweans with AIDS with acute cryptococcal meningitis [Letter]. Clin Infect Dis 2010; 51: 984–985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.US Department of Health and Human Services Panel on A ntiretroviral Guidelines for Adults and Adolescents. Guidelines for the use of antiretroviral agents in HIV-infected adults and adolescents, December 1, 2009. Washington DC, USA: US DHHS, 2011. http://www.aidsinfo.nih.gov/ContentFiles/AdultandAdolescentGL.pdf Accessed February 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Monty T, ed. McCord-Siyaphila Centre standard operating guidelines. Durban, South Africa: McCord Hospital, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 12.US Department of Health and Human Services Health Resources and Services Administration HIV/AIDS Bureau Working Group on HIV and Palliative Care. Palliative and supportive care. Washington DC, USA: HRSA Care Action, 2000. http://www.hab.hrsa.gov Accessed May 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Benson CA, Kaplan JE, Masur H, et al. Treating opportunistic infections among HIV infected adults and adolescents. MMWR 2004; 53 (RR-15): 1–112. http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/rr5315al.htm Accessed April 2012. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Maskew M, Brennan AT, Macphail AP, et al. Poorer ART outcomes with increasing age at a large public sector HIV clinic in Johannesburg, South Africa. J Int Assoc Physicians AIDS Care 2011; 53: 500–506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hofmeyer GP, Georgiou T, Baker CW, et al. The Keiskamma AIDS Treatment Programme: evaluation of a community based antiretroviral programme in a rural setting. S Afr J HIV Med 2009; 33: 38–41. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Eshun-Wilson M, Van der Plas H, Prozesky HW, et al. Combined antiretroviral treatment initiation during hospitalization: outcomes in South African adults. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2009; 51: 104–106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]