ABSTRACT

Formed by back splicing or back fusion of linear RNAs, circular RNAs (circRNAs) constitute a new class of non-coding RNAs of eukaryotes. Recent studies reveal a spliceosome-dependent biogenesis of circRNAs where circRNAs arise at the intron-exon junctions of mRNAs. In this study, using a novel de novo identification method, we show that circRNAs can originate from the interior regions of exons, introns, and intergenic transcripts in human, mouse and rice, which were referred to as interior circRNAs (i-circRNAs). Many i-circRNAs have some remarkable characteristics: multiple i-circRNAs may arise from the same genomic locus; their back fusion points may not be associated with the AG/GT splicing sites, but rather a new pair of motif AC/CT, their back fusion points are adjacent to complementary sequences; and they may circulate on short homologous sequences. We validated several i-circRNAs in HeLa cells by Polymerase Chain Reaction followed by Sanger sequencing. Our results combined showed that i-circRNAs are bona fide circRNAs, indicated novel biogenesis pathways independent of the splicing apparatus, and expanded our understanding of the origin, diversity, and complexity of circRNAs.

KEYWORDS: RNA, circular RNA, chimeric RNA, RNA sequencing, PCR, Sanger sequencing

Introduction

RNA typically exists in the linear form in the cell. As first reported decades ago, it may also appear in a single-stranded, covalently closed circular form, referred to as circular RNA or circRNA [1,2]. Recent genome-wide sequencing-based RNA profiling (i.e., RNA-seq) has revealed that circRNAs exist broadly in animals [3–5], plants [6–8] and nearly all eukaryotic species [9]. Functional analysis has suggested molecular functions of circRNAs, including promoting transcription [10], competing with canonical splicing [11], and influencing expression of mRNA [12] and protein [11]; some circRNAs may even be translated into polypeptides and proteins [13–15]. circRNAs exhibit expression patterns that are specific to cell types and tissues [16–20] as well as development stages [21–23]. Some circRNAs have been shown to have aberrant expression in complex diseases, such as cancer [24–26], osteoarthritis [27,28], and cardiovascular diseases [29,30].

Most of the reported circRNAs contain exclusively exons or exons and introns [31–33], and these circRNAs join at intron-exon junctions, suggesting that they are products of the splicing apparatus [34–37]. Indeed, formation of some of these circRNAs has been shown to require canonical splicing signals [37,38] and to involve exon skipping [39,40]. Furthermore, it has been shown that trans-acting RNA-binding proteins and complementary repeat sequences, e.g., Alu elements in human, in adjacent introns help bring the 3ʹ-end of an exon and the 5ʹ-end of the exon or an upstream exon to close proximity in the cell and subsequently join the two ends of the linear transcript to help form a circRNA [41–46].

It is important to highlight that intergenic regions have been indicated to host circRNAs [4,6,47]. Nevertheless, most recent studies have focused on circRNAs originated from intron-exon junctions. Particularly, the existing circRNA identification methods zoom onto genomic loci of intron-exon boundaries and capitalize on the annotated splicing signals of splicing donor and receptor sites on the genome [47–49]. However, it remains unresolved if intron-exon junctions are the only genomic origin for circRNA production and if splicing is the only mechanism underlying circRNA biogenesis.

Here, we report a large number of circRNAs that arise from inside of exons, introns, and intergenic transcripts in human (Homo sapiens), mouse (Mus musculus) and rice (Oryza sativa). To distinguish them from the reported circRNAs over intron-exon junctions, we named such novel circRNAs as interior circRNAs or i-circRNAs for short. We experimentally validated several i-circRNAs in HeLa cells using Polymerase Chain Reactions (PCR) followed by Sanger sequencing. The results revealed that 1) multiple i-circRNAs may arise from the same genomic loci, 2) the back fusion points of i-circRNAs may not be adjacent to splicing signals but rather a new pair of motif, 3) the back fusion points of a substantial number of i-circRNAs may be adjacent to some new characteristic sequence motifs, and 4) many i-circRNAs have short homologous sequences at their back fusion points, suggesting their possible role in circRNA biogenesis. All of these findings provided novel insights into the diversity and biogenesis of circRNAs.

Results

Interior circRNAs – diverse circRNAs of distinct genomic origins

A large number of circRNAs, particularly i-circRNAs, were detected by a new circRNA identification method (see Methods and Fig. 1). The method does not rely on splicing signals of donor and receptor sites or genome annotation, but instead extensively searches for all possible RNA back fusion points, regardless of their origins, that are sampled by RNA-seq profiling experiments (Fig. 1A). To increase the accuracy and confidence of expected results, the search focuses on those candidate back fusion events in both genic and intergenic regions supported by RNA-seq data with little ambiguity (Fig. 1B). While there certainly exist circRNAs spanning across more than one exon or intron, it is difficult to infer such circRNAs with certainty based on RNA-seq data alone, particularly on data collected from an RNA library preparation protocol that does not enrich circular RNAs (Fig. 1B). Therefore, we focused on candidate circRNAs from single introns, single exons, pairs of adjacent introns and exons (Fig. 1B) and intergenic noncoding transcripts that were treated as if they were intronless transcripts. Furthermore, we only considered RNA-seq reads that were uniquely split-mapped to candidate back fusion loci (Fig. 1A), and adopted a stringent criterion that a candidate back fusion event must be supported by at least k split-mapped reads in one of the RNA-seq libraries. The larger k is, the more stringent the circRNA detection criterion becomes. In summary, our new method is purely an RNA-seq data-driven approach that does not rely on information of gene annotation or splicing signals, and is able to identify candidate circRNAs regardless their genomic origins.

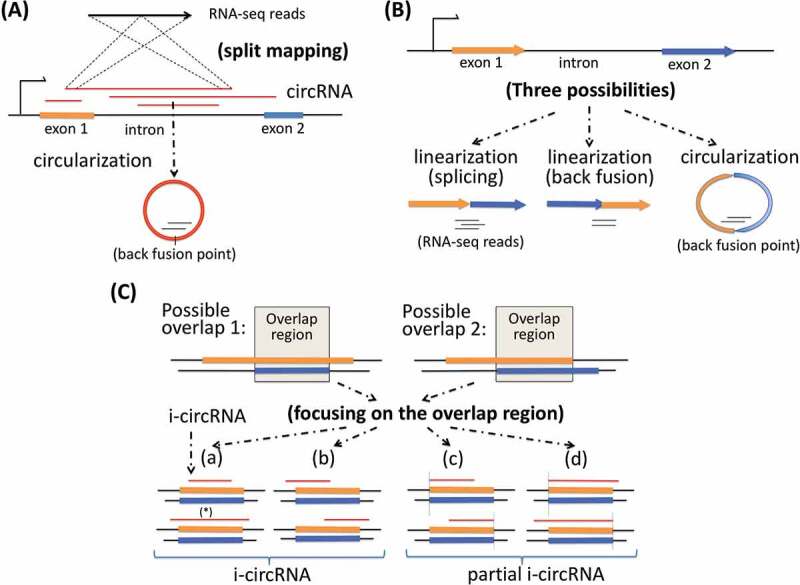

Figure 1.

Two key elements for identification of circRNAs and classification of circRNAs. (a) The first key element is split mapping of RNA-seq reads to candidate circRNAs, particularly i-circRNAs, which may originate from an interior region of an exon, an intron or a pair of adjacent exon and intron. (b) The second key element is to avoid ambiguity in distinguishing a canonical circRNA or i-circRNA spanning over more than one exon using RNA-seq data alone, particularly data from an RNA library preparation protocol where circRNAs are not enriched. Shown here are two exons from which two possible linear RNAs, one from splicing and the other from back splicing, and a circular RNA may be produced independently. It is difficult to distinguish the circRNA from the linear RNAs when they appear together using RNA-seq data alone. To this end, the analysis here focuses on candidate circRNAs from one exon, one intron, or an adjacent exon and intron pair. (c) Classification of i-circRNAs. An i-circRNA may have four possible positions relative to the intron-exon boundaries of its originating transcript. A more elaborate scenario involves an i-circRNA from locus with more than one gene annotation. Two types of gene annotation may appear, one where an exon encompasses another exon and the other where two exons are partially overlapped. Regardless which of the two types occurs, it is sufficient to consider only the overlapping region. Based on the relative position of the i-circRNA and the overlapping region, the i-circRNA can be classified into a complete i-circRNA (or i-circRNA) or partial i-circRNA where one of the back fusion points of the i-circRNA is aligned to one of the boundaries of the overlapping region.

An i-circRNA may have a few possible positions relative to its originating RNA transcript (Fig. 1C). Consider a simple case of a transcript consisting of a single exon. In addition to possibly giving rise to a circRNA by circularization on its 5ʹ-end and 3ʹ-end, it may host an i-circRNA completely interior to the transcript, which is referred to as complete i-circRNA or simply i-circRNA. In addition, it may generate an i-circRNA starting from its 5ʹ-end and ending in the middle of the transcript or an i-circRNA starting in the middle and ending at its 3ʹ-end, any of which is referred to as a partial i-circRNA (Fig. 1C). It is more involved when the originating transcript is from a genomic locus that is annotated to have more than one gene structure. Regardless, it is sufficient to focus on the common region of two or multiple overlapping exons and/or introns (Fig. 1C), and reason about the position of the circRNA with respect to the common region following the same rules for classifying i-circRNAs into complete i-circRNAs and partial i-circRNAs (Fig. 1C). i-circRNAs from intergenic regions are analysed and classified in reference to the currently annotated intergenic noncoding transcripts, if available, and transcripts assembled using the same RNA-seq data that are employed to detect circRNAs (see Methods).

Interior circRNAs are ubiquitous in eukaryotes

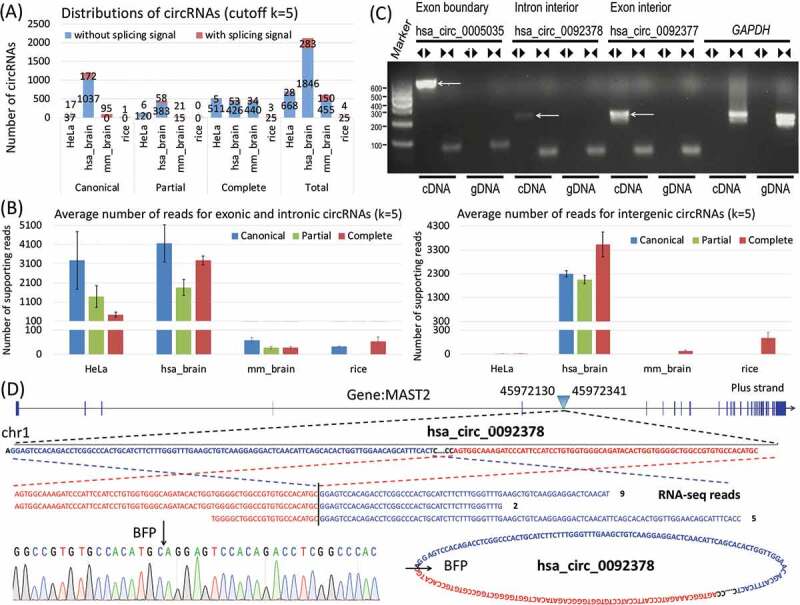

We applied the new circRNA identification method to four collections of RNA-seq data from human (brain and HeLa cells), mouse (brain) and rice (root) (Table S1). We identified a large number of circRNAs, many of which were i-circRNAs residing inside of introns, exons and intergenic regions (Fig. 2A & S1, Tables S2–S8). In HeLa cells, human brain, mouse brain and rice root, 642 (92.2% of the total), 920 (43.2%), 510 (84.3%) and 28 (96.6%) of the circRNAs that we detected were i-circRNAs, among which 516, 479, 474 and 28 were complete i-circRNAs, respectively (Fig. 2A). Interestingly, there exist more i-circRNAs than canonical circRNAs, and complete i-circRNAs constitute a large part of all circRNAs of the three organisms that we profiled (Fig. 2A, S1 & S2, Tables S2–S4). Note that in genic regions i-circRNAs and canonical circRNAs had compatible average expression abundances, measured by the number of RNA-seq reads, in human brain and mouse brain, whereas the former had a higher average expression level than the latter in intergenic transcripts in human brain; Surprisingly, in HeLa cells canonical circRNAs from genic regions were nearly an order of magnitude more abundant, measured by the number of RNA-seq reads, than complete i-circRNAs on average (3,276.6 reads versus 437.2 reads) from the same genomic regions (Fig. 2B). This observation suggested that expression of circRNAs was tissue and cell-specific and was also related to their genomic origins.

Figure 2.

Distribution of i-circRNAs and their average expression abundance in three species and experimental validation of i-circRNAs in HeLa cells. (a) Distributions of circRNAs and i-circRNAs in HeLa cells, human brain, mouse brain and rice roots when the minimal number of reads mapped to a back fusion point is set to k = 5. Additional criteria are applied to human brain, mouse brain and rice roots to accommodate genetic heterogeneity across libraries with more than 5 samples, that is, i-circRNAs are present in at least 191, 2 and 6 samples. Boundary circRNAs are canonical circRNAs, and i-circRNAs are further classified into partial and complete i-circRNAs. All circRNAs are further annotated as whether being adjacent to splicing signals or not. (b) Average expression levels (quantified by RNA-seq reads) of complete i-circRNAs, partial i-circRNAs and canonical circRNAs in genic regions (left) and from intergenic transcripts (right). (c) Validation of a canonical circRNA (has_circ_0005035) and two i-circRNAs in HeLa cells by PCR. The divergent and convergent arrows above the gel image represent, respectively, the divergent and convergent PCR primers used, and the white arrows in the gel image point to circRNAs. Here, hsa_circ_0005035, a canonical (exonic boundary) circRNA, was used as a positive control, hsa_circ_0092378 is an intronic i-circRNAs and hsa_circ_0092377 is an exonic i-circRNA. Gene GRAPDH was used as an internal control. (d) The genomic origin of intronic i-circRNA hsa_circ_0092378, its circular structure and back-fusion points (BFPs), and the results from RNA-seq and the Sanger sequencing.

Remarkably, most i-circRNAs do not carry splicing signals, i.e., their back fusion points are not adjacent to splicing signals of the major or minor splicing donor and receptor sites (Figs. 2A, S1 & S2, Tables S2–S8).

The circRNAs detected in HeLa cells were genuine circRNAs since a stranded RNA extraction method with a ribo-zero protocol (to preserve noncoding RNAs) plus RNase R treatment (to remove linear transcripts) was adopted in RNA-seq library preparation. To further confirm the i-circRNA candidates that we identified to be bona fide i-circRNAs, 14 complete i-circRNAs and 2 canonical circRNAs from HeLa cells were chosen for experimental validation (Figs. 2, 3 & S3). Divergent PCR primers were designed and applied separately to the RNA and DNA of the circRNAs to be validated. The circRNAs that were detected in RNA but not in DNA were further subjected to Sanger sequencing for confirmation (Figs. 2C, 2D, 3B, 3C, 3D & S3). Note that Sanger sequencing successfully recovered the full-length structure of an intronic i-circRNAs hsa_circ_0092378. In our experiments, we also included hsa_circ_0005035 and has_circ_0092379, a canonical circRNA from the second exon of gene IGF1R on human chromosome 15 and a canonical circRNA from the first exon of gene RMRP on human chromosome 9, respectively, as positive controls (Figs. 2C, 3B & S3A). In total, 5 (35.7% of 14) i-circRNAs and 2 (100% of 2) canonical circRNAs in HeLa cells were experimentally validated. One possible reason for not being able to detect all 14 i-circRNAs using PCR was the significantly lower expression abundance of i-circRNAs than canonical circRNAs in HeLa cells – the former was on average nearly one order of magnitude lower than the latter (Fig. 2B). Combined, the results showed that i-circRNAs exist in animal and plant species, which are in concordance with the previous results that circRNAs appear in nearly all branches of life [9].

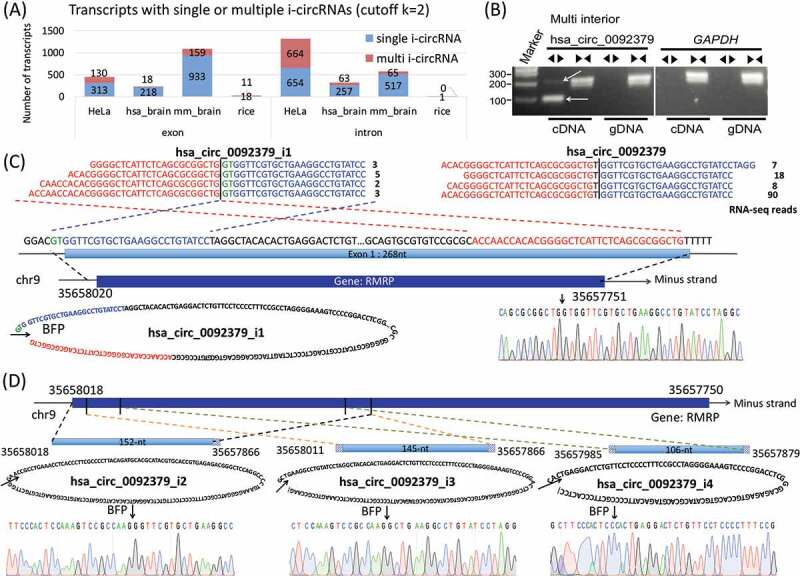

Figure 3.

Multiple i-circRNAs from the same loci. (a) Distributions of multiple and single i-circRNAs originated within a single exon or intron in the HeLa cells, human brain, mouse brain and rice roots when the minimal number of reads mapped to a back fusion point is set to k = 2. The human brain, mouse brain and rice roots data are analysed with one additional criterion that i-circRNAs must be present in at least 191 out of 953, 2 out of 7 and 6 out of 30 samples, respectively. (b) Detection of multiple i-circRNAs around the locus of the first exon of gene RMRP in the HeLa cells by PCR. The divergent and convergent arrows above the gel image represent divergent and convergent PCR primers used, respectively, and the white arrows in the gel image indicate detected i-circRNAs. Gene GRAPDH is used as an internal control. (c) The genomic origin of the largest i-circRNA hsa_circ_0092379-i1, its circular structure, the results from RNA-seq (the four lines of sequencing reads on the top left) and the Sanger sequencing (on the lower right). The two back fusion points of this circRNA are 2-bp before the exon and 1-bp before the end of the exon. Included here is the RNA-seq result of the canonical circRNA hsa_circ_0092379 from the exon (the four lines of reads on the top right). (d) The genomic origins of three smaller i-circRNAs hsa_circ_0092379_i2, _i3 and _i4, their circular structures, back-fusion points and the results from the Sanger sequencing. All of these i-circRNAs reside within the largest i-circRNA hsa_circ_0092379-i1 shown in (C).

More than one interior circRNA from the same genomic locus

Our results also revealed that more than one i-circRNA may originate from inside of the same intron or exon for the three species we analysed (Fig. 3A). Interestingly, one transcript may even host multiple circRNAs, some of which share some common sequences. Specifically, 794 (45.1%), 81 (14.6%), 224 (13.4%) and 11 (36.7%) of all i-circRNA generating transcripts may produce more than one i-circRNA in HeLa cells, human brain, mouse brain and rice roots, respectively. For example, four i-circRNAs emerge from the locus of the first exon of gene RMRP in the HeLa cells, and the exon itself produces a canonical circRNA hsa_circ_0092379 (Figs. 3B, 3C & 3D). The largest i-circRNA from this locus, hsa_circ_0092379_i1, spans across the 5ʹUTR and the first exon of RMRP (Fig. 3C). This i-circRNA (hsa_circ_0092379_i1) and the canonical circRNA (hsa_circ_0092379) from the first exon were identified by RNA-seq profiling experiments, and the i-circRNA was also detected by the Sanger sequencing, even though its expression level was relatively lower than the canonical circRNA. Interestingly, the PCR assay and Sanger sequencing detected three additional smaller i-circRNAs, all of which are embedded within the largest i-circRNA (Fig. 3D). The smallest i-circRNA (i.e., hsa_circ_0092379_i4) also resides completely inside the other two i-circRNAs (hsa_circ_0092379_i2 and has_circ_0092379_i3, Fig. 3D).

Note that some i-circRNAs were not initially detected by RNA-seq profiling, but rather by subsequent PCR and/or the Sanger sequencing. For example, the back-fusion points of the three smaller i-circRNAs hsa_circ_0092379_i2 to hsa_circ_0092379_i4 (Fig. 3D) were not recorded in the RNA-seq data, but were serendipitously discovered by PCR using the same pairs of divergent primers designed to validate their companion canonical circRNA, hsa_circ_0092379, and the largest i-circRNA, hsa_circ_0092379_i1.

Novel sequence motifs AC/CT associated with i-circRNAs

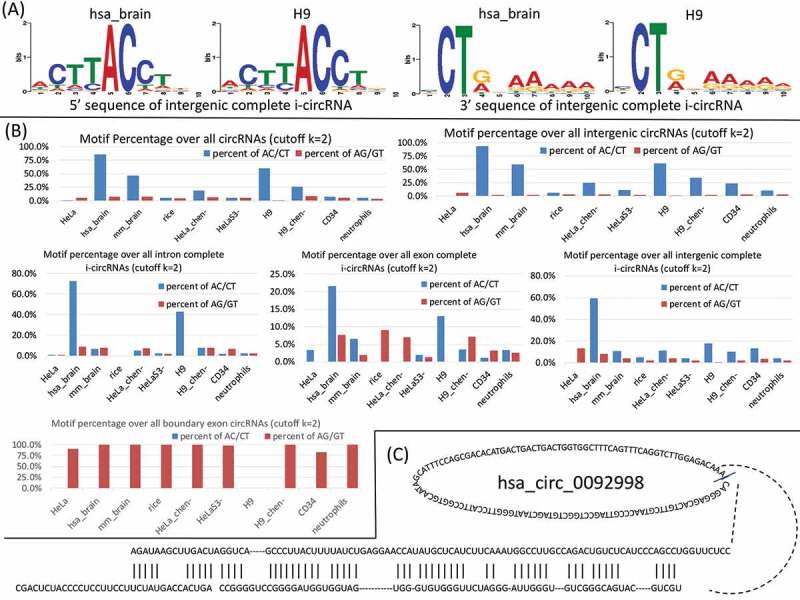

To further characterize the i-circRNAs that we discovered, the motif finding method MEME (multiple EM for motif elicitation) [50,51] was applied separately to the linear sequences of 15-nt long that are adjacent to the 5ʹ-end and 3ʹ-end back fusion points of the i-circRNAs detected in 10 datasets (Table S1, see Methods). These linear sequences were 5-nt inside and 10-nt outside of i-circRNAs. The 10 datasets cover different organisms (human, mouse and rice), different tissues and cell types (brain, root, HeLa, H9, HeLaS3, CD34, neutrophils) and different sequencing libraries (poly(A)-, ribominus, ribo-zero and RNase R treated). A pair of motif, AC on the 5ʹ-end and CT on the 3ʹ-end of intergenic complete i-circRNAs, was found in human brain (ribo-zero RNA-seq data) and H9 cell lines (stranded and RNase R treated poly(A)-/ribo-zero RNA-seq data) (Fig. 4A & Table S1). These two short motifs are immediately adjacent to the 5ʹ-end and 3ʹ-end of i-circRNAs where the AG and GT splicing signals normally appear for canonical splicing. A search of the AC/CT motif pair was performed over all circRNAs and i-circRNAs in the four datasets that we analysed plus additional RNA-seq data from HeLa, H9, and CD34 cells as well as neutrophils (Fig. 4B & Table S1). Not surprisingly, in human brain and H9 cells, 3553 (85.6%) and 3661 (60.3%) of the total circRNAs had the AC/CT motif. A higher abundance was observed in intergenic circRNAs, among which 3440 (93.7%) and 3538 (61.4%) carried the AC/CT motif in human brain and H9, respectively. In addition, mouse brain (ribo-depletion RNA-seq data), HeLa_chen- (poly(A)- RNA-seq data) and H9_chen- (poly(A)- RNA-seq data) also exhibited an enrichment of this novel motif in intergenic circRNAs with respective percentages of 59.8% (1983 out of 3317), 24.7% (112 out of 454) and 34.2% (118 out of 345). In intronic complete i-circRNAs, 67 (72.8%), 7 (6.7%), 97 (42.7%) and 3 (7.7%) of the total had the AC/CT in human brain, mouse brain, H9 and H9_chen- (poly(A)- RNA-seq data), respectively. In accordance with intergenic circRNAs, human brain, mouse brain, HeLa_chen-, H9 and H9_chen- also had an enrichment of the AC/CT motif in intergenic complete i-circRNAs, of which 157 (59.0%), 81 (10.5%), 18 (11.0%), 191 (17.7%) and 11 (10.2%) of the total had the novel motif. While this pair of motif is not always significantly enriched in all sequencing libraries, it appears more abundantly in intergenic and intronic complete i-circRNAs than the other circRNAs.

Figure 4.

Sequence and structural features characteristic of i-circRNAs. (a) A novel motif pair AC/CT residing immediately adjacent to the back fusion points of intergenic complete i-circRNAs in human brain and H9. (b) Distributions of the AC/CT signals in i-circRNAs in various genomic regions and the AC/CT signals in boundary circRNAs of 10 tissues and cell types in human, mouse and rice with at least 2 reads mapped to a back fusion point. Note that the human brain, mouse brain and rice roots data are restricted with one additional criterion that i-circRNAs must be present in at least 191 out of 953, 2 out of 7 and 6 out of 30 samples, respectively. (c) An example of RNA folding structure and complementary sequences flanking an intronic i-circRNA, hsa_circ_0092998.

Complementary sequences flanking i-circRNAs

RNA folding structures over the flanking sequences near the back splicing or back fusion points of circRNAs constitute constructs for the production of some canonical circRNAs [41–45]. To test if this is also the case for some of the i-circRNAs identified, we fold the 100-bp sequences up- and down-stream of the back fusion points of canonical and interior circRNAs with RNAfold [52]. The resulting secondary structures that have at least 50% sequence complementarity were retained. A total of 7 (8.8%of 80), 24 (1.8% of 1299), 10 (5.6% of 179) and 0 (0.0% of 1) canonical circRNAs (k = 2) have paired flanking sequences in HeLa, human brain, mouse brain and rice roots, respectively (Tables S5–S8). A total of 40 (3.9% of 1038), 30 (3.0% of 985), 83 (9.1% of 916) and 2 (3.9% of 51) i-circRNAs (k = 2) in HeLa, human brain, mouse brain and rice roots, respectively, have paired flanking sequences (Tables S5–S8, see Fig. 4C for an example). This suggested that some i-circRNAs might be generated through fold back structures of complementary sequences.

Short homologous sequences at the back fusion points

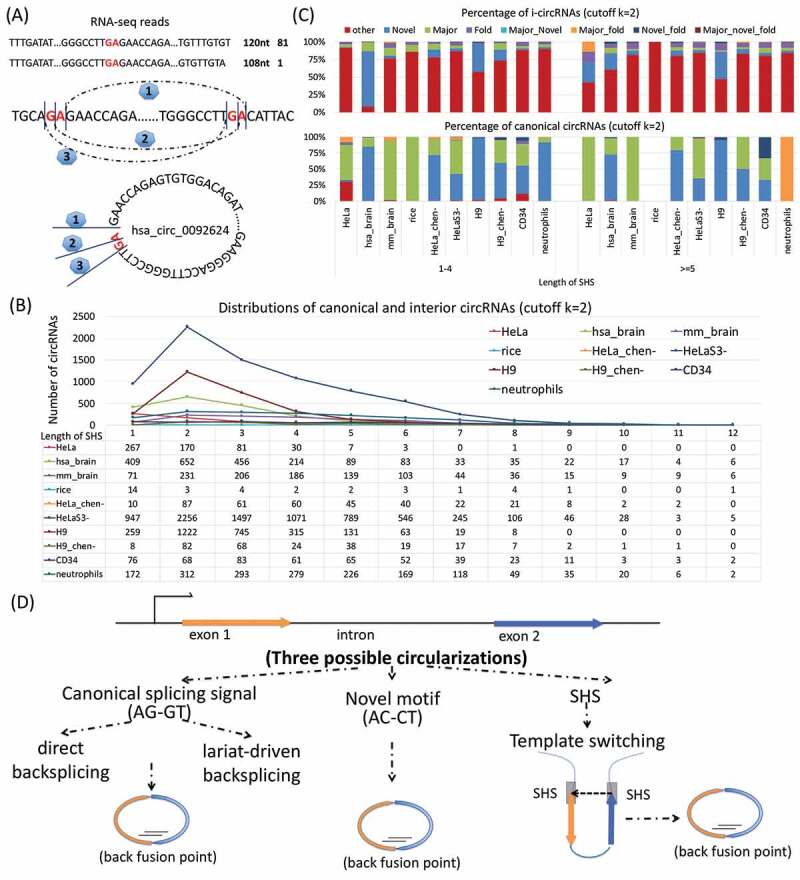

Another interesting finding was short homologous sequences (SHSs) at the back fusion points of canonical circRNAs and i-circRNAs (Fig. 5A). The lengths of SHS vary from 1- to 34-nt with the majority in the range of 1- to 6-nt and peaked at 2-nt (Fig. 5B). SHSs are overall abundant, with the percentage of circRNAs with SHSs ranging from 50.0% (559 out of 1117 in HeLa) to 98.6% (359 out of 364 in HeLa_chen-) and the abundance is more pronounced in i-circRNAs (Fig. 5C), indicating a potential role that SHSs may play in the formation of circRNAs.

Figure 5.

Short homologous sequences (SHSs) associated with circRNAs. (a) An example of the effect of SHS on possible back fusion points on i-circRNA hsa_circ_0092624, where, due to dinucleotides GA and sequencing reads across GA, there may exist three candidate back fusion points, marked as 1, 2 and 3. (b) Distributions of canonical and interior circRNAs with SHSs of different lengths in 10 tissues and cell types in human, mouse and rice. Shown are circRNAs with SHSs shorter than 14-nt. (c) Percentages of canonical and interior circRNAs with major splicing signal (AG/GT), novel motif (AC/CT), folding structure or combinations of them. Here, Novel = circRNAs with novel motif (AC/CT), Major = circRNAs with major splicing signal (AG/GT), Fold = circRNAs with folding structures of complementary sequences, Major_Novel = circRNAs with major splicing signal (AG/GT) and novel motif (AC/CT), Major_fold = circRNAs with major splicing signal (AG/GT) and folding structures, Novel_fold = circRNAs with novel motif (AC/CT) and folding structures, Major_novel_fold = circRNAs with major splicing signal (AG/GT), novel motif (AC/CT) and folding structures, other = all the other circRNAs. (d) Three possible circular RNA biogenesis mechanisms, (left) splicing apparatus that uses splicing signal AG/GT for production of canonical circRNAs, (middle) an unknown RNA circulation mechanism that utilizes the novel motif AC/CT, and (right) RNA template switching due to SHS which is known to generate chimeric transcripts.

A close examination of the other characteristics surrounding the back fusion points of circRNAs, including the splicing signal (AG/GT), the novel motif (AC/CT), complementary sequences and folding structures, provided additional information of SHS. In particular, the major splicing signal (AG/GT) and the novel motif (AC/CT) predominate in canonical circRNAs; in contrast, SHSs prevail in i-circRNAs (Fig. 5C), indicating canonical and interior circRNAs may be generated by distinct biogenesis mechanisms (Fig. 5D). Complementary sequences and fold-back structures also appear in some of i-circRNAs, which may assist the formation of i-circRNAs.

Discussion

Although a few cases of circRNAs were reported decades ago, the recent genome-wide discovery of circRNAs as a ubiquitous form of RNA in eukaryotic organisms was surprising. The most important result reported here – interior circRNAs from interior regions of introns, exons, and intergenic transcripts – added a new member to the circRNA family. Not replying on splicing signals was our new circRNA identification method able to detect candidate circRNAs that exist in all regions of the genome. Furthermore, in supporting and extending the early observation that circRNA may emerge from intergenic regions [4,6,47], we further recognized that circRNAs may arise from interior regions of intergenic transcripts (Fig. S2, Tables S2–S8). In short, our results showed that circRNAs could be produced from interior of transcripts that have diverse genomic origins.

It was unexpected to discover more i-circRNAs than canonical circRNAs residing over intron and exon junctions. It was also surprising to detect more than one i-circRNAs from one genomic locus. It is interesting to note that additional multiple i-circRNAs can be identified by PCR followed by Sanger sequencing, which were initially missed by RNA-seq profiling. This must be primarily because RNA-seq profiling was often not sufficiently deep enough. It is critical to highlight that multiple i-circRNAs that we identified are different from multiple circRNAs from an ORF [53] because the latter are products of alternative splicing that contains different exons or introns.

We need to mention that the success rate of the complete i-circRNAs being PCR validated in HeLa cells is not high, at 35.7% (5 out of 14), comparing to the 100% success rate on canonical circRNAs (2 out of 2), primarily because the expression levels of the former are nearly an order of magnitude lower than that of the latter (Fig. 2B). Despite this relatively low success rate, the validation of the 5 complete i-circRNAs is sufficient to demonstrate that they are bona fide circRNAS, the central theme of the current study. Moreover, a complete i-circRNA has also been previously discovered by PCR from an oncogenic chimeric transcript fusing two genes PML and RARα [54]. In addition, we also identified i-circRNAs in human normal and psoriatic skin as well as the brain of Alzheimer’s disease, and experimentally validated several of them using disease-related cell lines and PCR followed by Sanger sequencing (to be reported elsewhere). Combined, all these results showed that i-circRNAs are not only genuine circRNAs, but also functional, particularly in diseases.

The numbers of all types of circRNAs that we detected varied significantly across different species (i.e., human, mouse and rice) and across tissues and cell lines (e.g., human brain versus HeLa cells). In addition to diverse species and tissues profiled, different sequencing protocols adopted in RNA-seq data collection seemed to be a leading factor contributing to the different numbers of circRNAs detected (e.g., RNaseR treated ribo-zero RNA-seq in HeLa versus poly(A)- RNA-seq in HeLa_chen-, and RNaseR treated ribominus RNA-seq in H9 versus poly(A)- RNA-seq in H9_chen-).

i-circRNAs are more prevalent than what we reported here. We restricted ourselves to those i-circRNAs that were within individual introns and exons and ignored i-circRNAs spanning across more than one intron or exon. As a result, we only identified a portion of the overall candidate i-circRNAs, and the landscape of circRNAs must be much greater than what we currently detected.

Unexpected, our result revealed that a large portion of canonical circRNAs and most i-circRNAs were not adjacent to the major splicing signal AG/GT. Interestingly, instead of carrying the AG/GT splicing signal, many i-circRNAs from intergenic regions in human brain as well as HeLa and H9 cells have a pair of short sequence motif AC/CT next to their 5ʹ- and 3ʹ-end back fusion points. This strongly suggested that a new mechanism different from splicing may be responsible for the production of these i-circRNAs (Fig. 5D).

It was a big surprise to discover short homologous sequences (SHSs) at the back fusion points of most i-circRNAs and some canonical circRNAs. This result was thought-provoking regarding the currently elusive mechanisms of circRNA biogenesis. It has been well established that canonical circRNAs can be derived from canonical splicing sites [34,36,38]. On the other hand, there are evidences suggesting the existence of novel circRNA biogenesis pathways independent of the canonical splicing apparatus – blocking components of spliceosome in Drosophila melanogaster results in a higher ratio of circular RNAs to linear RNAs [55,56]. The SHSs that we reported here may provide a missing piece to this puzzle. It is known that SHSs are involved in production of chimeric transcripts through template switching in RNA processing [57,58]. It is then viable to hypothesize that template switching is involved in or responsible for the biogenesis of many circRNAs, particularly i-circRNAs (Fig. 5D). The complete i-circRNA F-Circ2 from an oncogenic chimeric transcript in human discovered in an early study [54] provides a direct evidence supporting this hypothesis. F-Circ2 arises from a chimeric transcript that fuses two genes PML and RARα [54]. Remarkably, our close examination of the sequence of F-Circ2 revealed that one of the fusion points of F-Circ2 resides within an SHS (GCTGCCAG) inside of two exons, which starts at the 32-nt from the 5ʹ-end of the 4-th exon of PML and at the 88-nt from the 5ʹ-end of the 4-th exon of RARα. In addition, the early results and our analysis also suggested that RNA fold-back structures due to inverse complementary sequences or RNA-binding proteins at the two ends of the fusion points of a circRNA can bring the two ends into a close neighbourhood; subsequently the SHSs at the back fusion points of the circRNA can trigger template switching, resulting in RNA circulation (Fig. 5D).

In short, the results that we presented suggested two novel circRNA biogenesis pathways independent of the canonical splicing mechanism (Fig. 5D), a topic of interest for further investigation.

Materials and methods

Deep sequencing of RNA transcripts in HeLa cells

Total RNA of HeLa cells, supplied in the Ion Total RNA-Seq Kit v2, 12-Reaction Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific), was used to construct the whole-transcriptome libraries. RNA-seq libraries were constructed with the Ion Total-RNA Seq Kit v2 according to the manufacturer’s instructions and were sequenced on the Ion Proton System using the Ion PI Hi-Q Sequencing 200 Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific).

RNA-seq data from other sources

Besides the in-house sequencing data, we also analysed 9 other RNA-seq datasets (Table S1). These datasets include three different species, human (Homo sapiens), mouse (Mus musculus) and rice (Oryza sativa), and four different RNA library preparation protocols, poly(A)-, ribominus, ribo-zero and RNase R.

The data on human were collected from two human tissues, brain and blood (syn3157743, GSE33772), and three cell lines, HeLa (GSE24399), HeLaS3 (GSE30567) and H9 (GSE48003, GSE24399). The human brain data for AD study (Table S1) were retrieved from the Accelerating Medicines Partnership (AMP) AD Knowledge Portal (https://www.synapse.org/#!Synapse:syn2580853/wiki/66722). In particular, MSBB RNA-seq data (https://www.synapse.org/#!Synapse:syn3157743) were analysed, which were sequenced from tissue samples from four brain regions BM10, BM22, BM36 and BM44 of 100 normal subjects, 172 definite AD subjects, 49 probable AD subjects and 42 possible AD subjects measured by CERAD, for a total of 363 subjects and 953 RNA-seq samples.

The data on mouse were collected from four brain regions, hippocampus, cerebellum, prefrontal cortex and olfactory bulb, and 3 fractions, brain lysate, synaptoneurosomes and cytoplasm (GSE65926).

The data on rice were retrieved from GenBank accession PRJNA215013 under two conditions of Pi-sufficient and Pi-starvation at five time points, 6 h, 24 h, 3 d, 7 d and 21 d.

Identification of circRNAs

A new circRNA identification method was developed based on find_circ [4] to search for all possible back fusion points (BF points) that are captured in RNA-seq data without using any information of the major and minor splicing signals.

The RNA-seq reads are first aligned to the reference genome with Bowtie2 [59]. The mappable reads are discarded since they are from linear RNAs. The search of circRNAs starts with those RNA-seq reads that cannot directly map to the reference genome, i.e., those that are declared as unmappable reads by Bowtie2 [59]. For an unmapped read, the method takes a left and a right x-mer on the 5ʹ-end and 3ʹ-end of the read, called the left and right anchors, respectively (Fig. 1A). It then attempts to split-map the read to the genome, i.e., map the anchors to the genome where the two mapped genomic loci are dis-oriented with the two anchors. This means that the left anchor (the 5ʹ-end x-mer) maps to a genomic locus that is downstream to the genomic locus that the right anchor (the 3ʹ-end x-mer) maps to (Fig. 1A). If successful, it then searches for a split point within the sequence between the two anchors so that when the read is split at a split point, the two split segments of the read can be aligned to the genomic loci that the anchors determine (Fig. 1A). In the current implementation of the method on RNA-seq data with read length of 100 bp, x was initially set to 20, and no more than two mismatches were allowed in mapping.

To increase accuracy, only those BF points that are supported by at least k (e.g., k> 2 in most of our analyses) RNA-seq reads in one of the RNA-seq libraries that can be exclusively split-mapped to one pair of unique genomic loci are retained. Furthermore, only unambiguous candidate BF points are considered. Specifically, while there certainly exist circRNAs spanning across more than one exon, it is difficult to infer such circRNAs with certainty based on RNA-seq data alone, particularly on those RNA-seq data from an RNA preparation protocol that is not enriched for circRNAs (Fig. 1B). Therefore, candidate circRNAs from individual introns, exons, intergenic regions and pairs of adjacent introns and exons are considered in the present study.

To be consistent with circRNAs reported in circBase [60], we used the same ID format as in circBase but starting from hsa_circ_0092376 in human and mmu_circ_0001904 in mouse since the largest ID in circBase is hsa_circ_0092375 for human and mmu_circ_0001903 for mouse [60].

Validation of circRNAs in HeLa cells

HeLa cells were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC). The cells were cultured in Eagle’s Minimum Essential Medium (EMEM) (ATCC) supplemented with 10% foetal bovine serum (FBS) (ATCC) and 100 ug/mL streptomycin (Sigma-Aldrich, USA) and 100 units/mL penicillin (Sigma-Aldrich, USA) at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2. Total RNA was extracted from HeLa cells with a RNA extraction kit (Bio Teke Corporation, China), and reverse transcription was performed using a PrimeScript® RT reagent Kit (Takara, Japan), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Expression of a circRNA was verified using the polymerase chain reaction (PCR). The PCR products were ligated into the plasmid pEASY-T1 (Transgen, China) using the ClonExpress Entry One Step Cloning Kit (Vazyme Biotech, China). The constructs were verified by sequencing.

Discovery of novel motifs adjacent to the back fusion points of i-circRNAs

The popular motif finding method MEME [50,51] is used to discover ungapped motifs in the sequences extracted from the two ends of circRNAs, which include 5-nt inside and 10-nt outside of circRNAs. These sequences are first divided into the 5ʹ-end and 3ʹ-end groups of circRNAs. Each group is further classified as boundary, intron interior, exon interior and intergenic interior according to the originating loci of the circRNAs. These small groups of sequences are analysed by MEME separately to look for up to 3 motifs in each up to 10-nt long, with E-value threshold of 10 and position p-value of 0.0001.

Folding of flanking sequences

For each circRNA, 100-nt sequences outside of the 5ʹ-end and 3ʹ-end of the back fusion point are extracted separately. The two sequences are concatenated together in the 5ʹ- to 3ʹ-end order, and RNAfold [52] is then applied to the concatenated sequence to find the secondary structure of the merged sequence with the minimum free energy. The secondary structure is divided into two equal parts from the centre. The two parts are filtered with the following criteria: 1) at least 50-nt (i.e., 50% of the 100-nt sequence) are paired with nucleotides from the other part, and 2) no more than 10-nt are paired with nucleotides from the same part. The sequences passing through these criteria are considered to have complementary structures that may favour the generation of circRNAs.

Classification of intergenic circRNAs

The circRNAs that originate from intergenic regions are classified as boundary (or canonical) circRNAs, partial i-circRNAs and complete i-circRNAs according to the annotation of the assembled transcripts and two non-coding RNA databases, LNCipedia [61] for human and NONCODE2016 [62] for human and mouse. The assembled transcripts are obtained by merging the novel and known linear isoforms with cuffmerge [63] from the same RNA-seq data of circRNAs.

Data and software availability

Our RNA-seq data on HeLa cells are available in NCBI GEO databases under Recession number GSE119938. The software of our new circRNA identification method written in python is freely available in the public software repository github at https://github.com/xiaoxin8712/find_circ_any.

Funding Statement

This work was supported in part by National Natural Science Foundation of China [grants 31601995 and 31601090] and United States National Institutes of Health [grant R01 GM100364].

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

References

- [1].Hsu M-T, Coca-Prados MJN.. Electron microscopic evidence for the circular form of RNA in the cytoplasm of eukaryotic cells. Nature. 1979;280:339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Nigro JM, Cho KR, Fearon ER, et al. Scrambled exons. Cell. 1991;64:607–613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Salzman J, Gawad C, Wang PL, et al. Circular RNAs are the predominant transcript isoform from hundreds of human genes in diverse cell types. PloS One. 2012;7:e30733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Memczak S, Jens M, Elefsinioti A, et al. Circular RNAs are a large class of animal RNAs with regulatory potency. Nature. 2013;495:333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Lu C, Sun X, Li N, et al. CircRNAs in the tree shrew (tupaia belangeri) brain during postnatal development and aging. Aging (Albany NY). 2018;10:833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Ye CY, Chen L, Liu C, et al. Widespread noncoding circular RNAs in plants. New Phytol. 2015;208:88–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Lu T, Cui L, Zhou Y, et al. Transcriptome-wide investigation of circular RNAs in rice. Rna. 2015;21:2076–2087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Lai X, Bazin J, Webb S, et al. CircRNAs in plants. In: Xiao J, editors. Circular RNAs. Advances in experimental medicine and biology. Singapore: Springer; 2018. p. 329–343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Wang PL, Bao Y, Yee M-C, et al. Circular RNA is expressed across the eukaryotic tree of life. PloS One. 2014;9:e90859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Li Z, Huang C, Bao C, et al. biology m: exon-intron circular RNAs regulate transcription in the nucleus. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2015;22:256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Ashwal-Fluss R, Meyer M, Pamudurti NR, et al. circRNA biogenesis competes with pre-mRNA splicing. Mol Cell. 2014;56:55–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Zhong Y, Du Y, Yang X, et al. Circular RNAs function as ceRNAs to regulate and control human cancer progression. Mol Cancer. 2018;17:79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Legnini I, Di Timoteo G, Rossi F, et al. Circ-ZNF609 is a circular RNA that can be translated and functions in myogenesis. Mol Cell. 2017;66:22–37.e29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Yang Y, Fan X, Mao M, et al. Extensive translation of circular RNAs driven by N 6-methyladenosine. Cell Res. 2017;27:626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Pamudurti NR, Bartok O, Jens M, et al. Translation of circRNAs. Mol Cell. 2017;66):9–21e27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Salzman J, Chen RE, Olsen MN, et al. Cell-type specific features of circular RNA expression. PLoS Genet. 2013;9:e1003777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Filippenkov IB, Sudarkina OY, Limborska SA, et al. Circular RNA of the human sphingomyelin synthase 1 gene: multiple splice variants, evolutionary conservatism and expression in different tissues. RNA Biol. 2015;12:1030–1042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Rybak-Wolf A, Stottmeister C, Glažar P, et al. Circular RNAs in the mammalian brain are highly abundant, conserved, and dynamically expressed. Mol Cell. 2015;58:870–885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Memczak S, Papavasileiou P, Peters O, et al. Identification and characterization of circular RNAs as a new class of putative biomarkers in human blood. PloS One. 2015;10:e0141214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Stoll L, Sobel J, Rodriguez-Trejo A, et al. Circular RNAs as novel regulators of β-cell functions in normal and disease conditions. Mol Metab. 2018;9:69–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].You X, Vlatkovic I, Babic A, et al. Neural circular RNAs are derived from synaptic genes and regulated by development and plasticity. Nat Neurosci. 2015;18:603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Venø MT, Hansen TB, Venø ST, et al. Spatio-temporal regulation of circular RNA expression during porcine embryonic brain development. Genome Biol. 2015;16:245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Chen BJ, Huang S, Janitz MJG. Changes in circular RNA expression patterns during human foetal brain development. Genomics. 2019;111:753–758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Hansen TB, Kjems J, Damgaard C. Circular RNA and miR-7 in cancer. Cancer Res. 2013;73:5609–5612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Jiang L-H, Sun D-W, Hou J-C, et al. CircRNA: a novel type of biomarker for cancer. Breast Cancer. 2018;25:1–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Zhang H, Zhu L, Bai M, et al. Exosomal circRNA derived from gastric tumor promotes white adipose browning by targeting the miR‐133/PRDM16 pathway. Int J Cancer. 2019;144:2501–2515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Liu Q, Zhang X, Hu X, et al. Circular RNA related to the chondrocyte ECM regulates MMP13 expression by functioning as a MiR-136 ‘Sponge’in human cartilage degradation. Sci Rep. 2016;6:22572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Zhou Z-B, Huang G-X, Fu Q, et al. circRNA. 33186 contributes to the pathogenesis of osteoarthritis by sponging miR-127-5p. Mol Ther. 2019;27:531–541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Wang K, Long B, Liu F, et al. A circular RNA protects the heart from pathological hypertrophy and heart failure by targeting miR-223. Eur Heart J. 2016;37:2602–2611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Wang K, Gan T-Y, Li N, et al. Differentiation: circular RNA mediates cardiomyocyte death via miRNA-dependent upregulation of MTP18 expression. Cell Death Differ. 2017;24:1111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Liu Y-C, Li J-R, Sun C-H, et al. CircNet: a database of circular RNAs derived from transcriptome sequencing data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;44:D209–D215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Li J-H, Liu S, Zhou H, et al. starBase v2. 0: decoding miRNA-ceRNA, miRNA-ncRNA and protein–RNA interaction networks from large-scale CLIP-Seq data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;42:D92–D97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Ghosal S, Das S, Sen R, et al. Circ2Traits: a comprehensive database for circular RNA potentially associated with disease and traits. Front Genet. 2013;4:283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Ebbesen KK, Kjems J, Hansen TB. Circular RNAs: identification, biogenesis and function. Biochimica Et Biophysica Acta (bba)-gene Regulatory Mechanisms. 2016;1859:163–168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Jeck WR, Sharpless NE. Detecting and characterizing circular RNAs. Nat Biotechnol. 2014;32:453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Petkovic S, Müller S. RNA circularization strategies in vivo and in vitro. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43:2454–2465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Li X, Yang L, Chen -L-L. The biogenesis, functions, and challenges of circular RNAs. Mol Cell. 2018;71:428–442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Starke S, Jost I, Rossbach O, et al. Exon circularization requires canonical splice signals. Cell Rep. 2015;10:103–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Zaphiropoulos PG. Exon skipping and circular RNA formation in transcripts of the human cytochrome P-450 2C18 gene in epidermis and of the rat androgen binding protein gene in testis. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:2985–2993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Kelly S, Greenman C, Cook PR, et al. Exon skipping is correlated with exon circularization. J Mol Biol. 2015;427:2414–2417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Liang D, Wilusz JE. Short intronic repeat sequences facilitate circular RNA production. Genes Dev. 2014;28:2233–2247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Wilusz JE. Repetitive elements regulate circular RNA biogenesis. Mob Genet Elements. 2015;5:39–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Zhang X-O, Wang H-B, Zhang Y, et al. Complementary sequence-mediated exon circularization. Cell. 2014;159:134–147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Ivanov A, Memczak S, Wyler E, et al. Analysis of intron sequences reveals hallmarks of circular RNA biogenesis in animals. Cell Rep. 2015;10:170–177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Conn SJ, Pillman KA, Toubia J, et al. The RNA binding protein quaking regulates formation of circRNAs. Cell. 2015;160:1125–1134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Dai X, Zhang N, Cheng Y, et al. RNA-binding protein trinucleotide repeat-containing 6A regulates the formation of circular RNA circ0006916, with important functions in lung cancer cells. Carcinogenesis. 2018;39:981–992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Gao Y, Wang J, Zhao F. CIRI: an efficient and unbiased algorithm for de novo circular RNA identification. Genome Biol. 2015;16:4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Szabo L, Morey R, Palpant NJ, et al. Statistically based splicing detection reveals neural enrichment and tissue-specific induction of circular RNA during human fetal development. Genome Biol. 2015;16:126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Szabo L, Salzman JJNRG. Detecting circular RNAs: bioinformatic and experimental challenges. Nat Rev Genet. 2016;17:679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Bailey TL, Boden M, Buske FA, et al. Noble WSJNar: MEME SUITE: tools for motif discovery and searching. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:W202–W208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Bailey TL, Elkan C. Fitting a mixture model by expectation maximization to discover motifs in bipolymers. Proc Int Conf Intell Syst Mol Biol. 1994;2:28–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Lorenz R, Bernhart SH, Zu Siederdissen CH, et al. ViennaRNA package 2.0. Algorithms Mol Biol. 2011;6:26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].L-LJNrMcb C. The biogenesis and emerging roles of circular RNAs. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2016;17:205–211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Guarnerio J, Bezzi M, Jeong JC, et al. Oncogenic role of fusion-circRNAs derived from cancer-associated chromosomal translocations. Cell. 2016;165:289–302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Liang D, Tatomer DC, Luo Z, et al. The output of protein-coding genes shifts to circular RNAs when the pre-mRNA processing machinery is limiting. Mol Cell. 2017;68:940–954. e943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Kramer MC, Liang D, Tatomer DC, et al. Combinatorial control of Drosophila circular RNA expression by intronic repeats, hnRNPs, and SR proteins. Genes Dev. 2015;29:2168–2182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Li X, Zhao L, Jiang H, et al. Short homologous sequences are strongly associated with the generation of chimeric RNAs in eukaryotes. J Mol Evol. 2009;68:56–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Yang W, Wu J-M, Bi A-D, et al. Possible formation of mitochondrial-RNA containing chimeric or trimeric RNA implies a post-transcriptional and post-splicing mechanism for RNA fusion. PLoS One. 2013;8:e77016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Langmead B, Trapnell C, Pop M, et al. Ultrafast and memory-efficient alignment of short DNA sequences to the human genome. Genome Biol. 2009;10:R25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Glažar P, Papavasileiou P, Rajewsky NJR. circBase: a database for circular RNAs. RNA. 2014;20:1666–1670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Volders P-J, Verheggen K, Menschaert G, et al. An update on LNCipedia: a database for annotated human lncRNA sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;43:D174–D180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Zhao Y, Li H, Fang S, et al. NONCODE 2016: an informative and valuable data source of long non-coding RNAs. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;44:D203–D208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Trapnell C, Roberts A, Goff L, et al. Differential gene and transcript expression analysis of RNA-seq experiments with tophat and cufflinks. Nat Protoc. 2012;7:562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Our RNA-seq data on HeLa cells are available in NCBI GEO databases under Recession number GSE119938. The software of our new circRNA identification method written in python is freely available in the public software repository github at https://github.com/xiaoxin8712/find_circ_any.