Abstract

In many birds and mammals, the size and sex composition of litters can have important downstream effects for individual offspring. Primates are model organisms for questions of cooperation and conflict, but the factors shaping interactions among same-age siblings have been less-studied in primates because most species bear single young. However, callitrichines (marmosets, tamarins, and lion tamarins) frequently bear litters of two or more, thereby providing the opportunity to ask whether variation in the size and sex composition of litters affects development, survival, and reproduction. To investigate these questions, we compiled a large dataset of 9 species of callitrichines (n= 27,080 individuals; Callithrix geoffroyi, Callithrix jacchus, Cebuella pygmaea, Saguinus imperator, Saguinus oedipus, Leontopithecus chrysomelas, Leontopithecus chrysopygus, Leontopithecus rosalia, and Callimico goeldii) from zoo and laboratory populations spanning 80 years (1938 to 2018). Through this comparative approach, we found several lines of evidence that litter size and sex composition may impact fitness. Singletons have higher survivorship than litter-born peers and they significantly outperform litter-born individuals on two measures of reproductive performance. Further, for some species, individuals born in a mixed-sex litter outperform isosexually-born individuals (i.e., those born in all-male or all-female litters), suggesting that same-sex competition may limit reproductive performance. We also document several interesting demographic trends. All but one species (Cebuella pygmaea) has a male-biased birth sex ratio (BSR) with higher survivorship from birth to sexual maturity among females (although this was significant in only two species). Isosexual litters occurred at the expected frequency (with one exception: Cebuella pygmaea), unlike other animals, where isosexual litters are typically over-represented. Taken together, our results indicate a modest negative effect of same-age sibling competition on reproductive output in captive callitrichines. This study also serves to illustrate the value of zoo and laboratory records for biological inquiry.

Keywords: callitrichine, sibling competition, litter size, studbook, birth sex ratio

INTRODUCTION

Variation in the size and sex composition of litters can have important implications for the developmental, survival, and reproductive outcomes of individual offspring. Sibling number—i.e., litter size—often matters because individuals compete for a limited pool of parental resources. For example, Northern quoll (Dasyurus hallucatus) mothers have only eight teats but give birth to seventeen neonates, inevitably generating winners and losers within each litter (Nelson & Gemmell, 2003). Wild European starling (Sturnus vulgaris) chicks raised in larger clutches weigh less than chicks raised in smaller clutches, and these disparities have important implications for immune functioning (Nettle et al., 2016). The sex composition of litters also can impose lasting outcomes, but the direction of these effects differs across taxa. In spotted hyenas (Crocuta crocuta), a species which exhibits facultative siblicide, all-female and all-male litters exhibit higher rates of aggression than do mixed-sex litters during infancy (Golla, Hofer, & East, 1999). In contrast, among humans, females born with male co-twins exhibit socioeconomic and reproductive shortcomings compared to females born with twin sisters (Bütikofer, Figlio, Karbownik, Kuzawa, & Salvanes, 2019). Thus, comparative study of litter composition may provide insight about the complex interplay of proximate and ultimate factors shaping variation in these traits.

Within primates, several lineages routinely produce litters (Leutenegger, 1979), thereby providing the opportunity to investigate the 1) mechanisms responsible for, 2) constraints associated with, and 3) consequences of varying litter size and sex composition. The callitrichines – marmosets, tamarins, and lion tarmains – are Neotropical monkeys that produce small litters (ranging from 1 – 5 in captivity; with the exception of the singleton-producing genus, Callimico) with twins being the most common litter size (Digby, Ferrari, & Saltzman, 2011; Rutherford & Tardif, 2008; Tardif et al., 2003). Characteristics associated with litter composition can have lasting impacts on survival and reproduction. Indeed, triplets are unusual in the wild (Digby et al., 2011), and they often exhibit higher mortality than do offspring from smaller cohorts (Box & Hubrecht, 1987; Tardif et al., 2003; Ward, Buslov, & Vallender, 2014). However, in some species (i.e., C. jacchus), captive mothers routinely produce larger litters because of excess energy stores, which impacts ovulation dynamics (Tardif, Layne, & Smucny, 2002). The sex composition of litters also may mediate individuals’ developmental outcomes – e.g., via exposure to sex hormones produced by males in utero – but the overall evidence of such sex-related effects on development remains mixed (Bradley et al., 2016; De Moura, 2003; French et al., 2016; Frye, Rapaport, Melber, Sears, & Tardif, 2019; Rutherford, DeMartelly, Layne Colon, Ross, & Tardif, 2014).

Several other aspects of callitrichine biology may provide clues to the evolution and maintenance of particular litter compositions. Callitrichines breed cooperatively, whereby a dominant pair typically monopolizes reproduction and group members delay or forgo reproduction to rear offspring that are not necessarily their own (Digby et al., 2011). Breeding opportunities are thus a limited resource for which close relatives may compete (Henry, Hankerson, Siani, French, & Dietz, 2013; Saltzman, Digby, & Abbott, 2009). Broadly, male-male competition (often between brothers) is very low, while many reports cite high levels of female-female competition (Abbott, 1993; Bicca-Marques, 2003; French & Inglett, 1989; Garber, Ón, Moya, & Pruetz, 1993; Haig, 1999; Kleiman, 1979; Roda & Pontes, 1998). Callitrichines are unusual among mammals for this intense female-female competition relative to males, accompanied by relatively larger reproductive skews in females (French, Mustoe, Cavanaugh, & Birnie, 2013). Further, callitrichines are genetic chimeras because they share placental circulation that allows for exchange of cells with their siblings in utero; this has uncertain implications for the interplay of conflict and cooperation within callitrichine groups (Haig, 1999). For all their unusual characteristics, members of this lineage present an opportunity to investigate the causes and consequences of variation in litter composition (i.e., sex composition and sizes).

Herein, we evaluated large demographic datasets (n=27,080 individuals) of 9 species of callitrichines living in captivity to examine multiple features that may be relevant to these traits: birth sex ratios, litter sizes, distributions of isosexual (i.e., all-male and all-female) versus mixed-sex litters, survivorship, and several measures of reproductive potential. Across these analyses, we explored the relationships between sibling sex, litter size, and phenotypic outcomes. We asked whether same- versus opposite-sex siblings impacted each other’s phenotypic outcomes. Further, we investigated whether litter size itself, and thus potential sibling competition, shapes survival and reproductive outcomes. Taken together, this examination of the links between litter composition and later life outcomes may advance our understanding of sibling interactions and intra-familial relationships writ large.

METHODS

Study Subjects

We analyzed longitudinal demographic records of 9 species of captive callitrichine primates: marmosets (i.e., Callithrix geoffroyi, Callithrix jacchus, and Cebuella pygmea), tamarins (Saguinus imperator and Saguinus oedipus), lion tamarins (Leontopithecus chrysopygus, Leontopithecus chrysomelas, and Leontopithecus rosalia), and Callimico goeldii. We obtained these data from international studbooks, national studbooks, university research programs, and national primate research centers (Table 1). Collectively, these records provide demographic information for captive callitrichines spanning an 80-year period (January 1938 to January 2018). These datasets included detailed demographic information about individuals’ births, deaths, parentage, location, and causes of death; from this, we inferred litter sex composition, litter sizes, litter orders, and parity (i.e., primiparous or multiparous).

Table 1.

Basic demographic information (i.e., numbers of male = M, female = F, animals of unknown sex = U, and proportions of each sex) for each species.

| Species | Common Name | Studbook Source | F | M | U | Prop. F | Prop. M |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Callimico goeldii | Goeldi’s marmoset | Chicago Zoological Society | 1427 | 1534 | 504 | 0.482 | 0.518 |

| Callithrix geoffroyi | White-headed marmoset | Chicago Zoological Society | 1160 | 1283 | 575 | 0.475 | 0.525 |

| Callithrix jacchus | Common marmoset | University of Zurich, Southwest National Primate Research Center, Massachusetts Institute of Technology | 1731 | 1800 | 1857 | 0.490 | 0.510 |

| Cebuella pygmaea | Pygmy marmoset | Australasian Species Management Program | 148 | 147 | 73 | 0.502 | 0.498 |

| Leontopithecus chrysomelas | Golden-headed lion tamarin | European Association of Zoos and Aquaria | 1625 | 1795 | 405 | 0.475 | 0.525 |

| Leontopithecus chrysopygus | Black lion tamarin | International Studbook | 187 | 244 | 83 | 0.434 | 0.566 |

| Leontopithecus rosalia | Golden lion tamarin | Association of Zoos & Aquariums | 1136 | 1370 | 616 | 0.453 | 0.547 |

| Saguinus imperator | Emperor tamarin | Chicago Zoological Society | 179 | 217 | 86 | 0.452 | 0.548 |

| Saguinus oedipus | Cotton top tamarin | Australasian Species Management Program | 2553 | 2892 | 1453 | 0.469 | 0.531 |

| Overall | 10146 | 11282 | 5652 | 0.473 | 0.527 |

Much of these data come from zoo populations, which are typically managed through, for example, separating pairs or contraception. When animals are group-living, estimations of paternity are not always certain. Here, for the variables we are interested in, we assume that management practices would not bias our results. In our analyses using litter composition, we designated litters as isosexual (i.e., same-sex) or mixed sex. We had some data points where one individual in a litter was of “unknown” sex, but the litter could still be designated as “mixed sex” (e.g., a litter with sexes male, female, and unknown is designated MFU; see Supplementary Table 1 for the numbers and sexes of individuals included in these analyses). We did not include animals born as singletons in our analyses of litter sex composition, because they likely gestated as twin or triplet litters of which we could not determine sibling sex (Jaquish, Tardif, Toal, & Carson, 1996). Callimico predominantly gives birth to singletons (Digby et al., 2011), so we excluded Callimico from all analyses of within-cohort sibling competition.

For our analyses of litter size, we compare offspring across four litter size categories: singletons, twins, triplets, and quad+ (quadruplets, quintuplets, and sextuplets). We note that the production of triplet and larger litters probably represents an artifact of captivity: heavier, captive mothers ovulate more eggs, leading to the production of supernumerary offspring in energy-rich environments (Tardif et al., 2002). However, while callitrichine mothers rarely raise more than two infants (Digby et al., 2011), surviving infants exhibit phenotypes that provide clues to the potential constraints stemming from early environments (e.g., Rutherford et al., 2014). Thus, we included triplet and quad+ animals in our sample to provide a complete accounting of reproductive outcomes.

Since our data consisted of archival data, we did not perform an Institutional Care and Use Committee review. However, all the institutions from which the data were sources adhered to all national, international, and American Society of Primatologists’ guidelines for the ethical treatment of nonhuman primates.

Population Birth Sex Ratios & Litter Sizes

To investigate whether sex ratios at birth diverged from an overall 1:1 BSR, we employed a Chi-square Goodness-of-Fit test. To calculate effect size, we used the function ES.chisq.gof in the R package “powerAnalysis” (Fan, 2017). We used the same procedure to investigate whether sex ratios differed by litter size.

To supplement these analyses, we examined interspecific variation in BSR and litter sizes using an ancestral state phylogenetic reconstruction, a method which can uncover the likely ancestral state of a continuous trait (Revell, 2012, 2013). We used the maximum-likelihood Callitrichine tree from Garbino and Martins-Junior (2018) as our reference phylogeny, which included all the species studied except Leontopithecus chrysopygus. Therefore, we added a tip for Leontopithecus chrysopygus, relying on the pairwise genetic distances reported from a phylogeny of lion tamarins (Mundy & Kelly, 2001). We then reconstructed the evolutionary history of population BSR (expressed as the proportion of males in the dataset by species) and mean litter sizes via the contMap and fastAnc functions in phytools v. 0.6-44 (Revell, 2012, 2013), including a 95% confidence interval for all inferred node states. Briefly, this program estimates the ancestral value of characters (i.e., how big were litters in the common ancestor of two species?), using maximum likelihood to estimate states at internal nodes, and interpolates these states along internal branches (Felsenstein, 1985).

For our ancestral state reconstruction of litter sizes, we included four non-callitrichine platyrrhine species with singleton births as outgroups (to represent that most New World monkeys give birth to singletons); these were Saimiri sciureus, Cebus apella, Aotus azarai, and Callicebus nigrifrons (Mittermeier, Rylands, & Wilson, 2013).

Litter Distributions: Sex Composition

To investigate whether the distribution of litter sex compositions differed from that which was expected, we first used the overall BSR of each callitrichine species to calculate the expected proportions of each litter type (excluding litters with offspring of unknown sex). Then we used a Chi-square Goodness-of-Fit test to inspect the distributions of both twin (i.e., FF, MF, MM) and triplet (MMM, MMF, MFF, FFF) litters. We hypothesized that divergence between the observed and expected proportions may indicate sex-mediated competition in utero: e.g., disproportionate production of isosexual litters suggests a selective advantage. Callimico was excluded from these analyses.

Survivorship

We explored how litter composition (sex of siblings) and litter size (number of siblings) impacted survivorship profiles. We restricted our analyses to the period prior to full-adulthood (sexual maturity), the stage at which both captive and free-ranging callitrichines face the highest risk of death (Kohler, Preston, & Lackey, 2006; Soini, 1982; Ward et al., 2014). Additionally, both male and female callitrichines may disperse from natal groups around the time of sexual maturation (Digby et al., 2011). As such, interactions among same-aged siblings may become less important determinants of fitness once siblings have dispersed from natal groups. Finally, for captive monkeys specifically, husbandry and management decisions to transfer animals around the time of sexual maturity (EAZA Husbandry Guidelines, 2010) may confound any findings of survivorship disparities because of transfer-associated mortality. Based on each of the callitrichine genera’s different pace of development, we identified life stages and thus ages at which we censored data (Supplementary Table 2). Despite these stages differing in absolute lengths (in days), each period is a conserved period of ontogenetic development across the callitrichine lineage (Díaz-Muñoz & Bales, 2015; Digby et al., 2011; Garber, Porter, Spross, & Di Fiore, 2015).

We constructed Cox proportional hazards regressions (Cox, 1972; Lee & Wang, 2003) using the “coxph” function in the R package “survival” (Therneau & Grambsch, 2000, 2013). We compared survivorship profiles of callitrichines for males and females that were born into isosexual and mixed-sex litters. We included litter size as a predictor variable to examine possible differences in the survivorship among infants born into singleton, twin, triplet, or larger-sized litters (Box & Hubrecht, 1987; Rothe, Darms, & Koenig, 1992; Ward et al., 2014). Finally, we clustered individuals by dams to control for non-independence among siblings, and we included the term “cluster(ID)” to account for any violations of the assumptions of proportional hazards. For post hoc analysis of the groups, we conducted multiple pairwise comparisons of the Kaplan-Meier survival curves using log rank tests via the “pairwise.survdiff” function in the R package “survminer” (Kassambara & Kosinski, 2018). In these post hoc analyses, we used the Benjamini & Hochberg correction to minimize the risk of Type I errors while maintaining statistical power (Benjamini & Hochberg, 1995).

Intergenerational Effects

It is likely that a given callitrichine’s litter composition at birth impacts its downstream reproductive output, due to developmental or social factors (e.g., Rutherford et al. 2014). To investigate this, we explored the relationships between a monkey’s litter size and sex composition at birth and subsequent reproductive performance (measured as (i) whether or not an individual becomes a parent and (ii) total number of offspring produced). First, we asked whether litter size matters: are singletons at an advantage compared to individuals born to larger litters, due to reduced competition for parental investment? Second, we asked whether litter composition matters: are animals born into a mixed-sex litter at an advantage compared to those in same-sex litters, due to reduced competition among littermates for reproductive opportunities? To answer these questions, for each species we calculated (i) the proportion of singletons in the female population (“Expected Proportion Singletons”) and (ii) the proportion of isosexual individuals (rather than mixed-sex) in the female population (“Expected Proportion Isosexual”). We did so for males as well. By the null hypothesis, assuming equal reproductive outputs for every individual, the observed proportion of singletons among dams should equal the expected proportion of singletons in the entire female population. Likewise, observed proportions should equal expected proportions for isosexual dams, singleton sires, and isosexual sires. We hypothesized that isosexuals would be underrepresented and singletons overrepresented among parents. To test our hypothesis, we performed Chi-square Goodness of Fit analyses to compare observed versus expected proportions of singletons and isosexual individuals for both dams and sires. To calculate effect size, we used the function ES.chisq.gof in the R package “powerAnalysis” (Fan, 2017). Finally, we performed these analyses once for unique dams and unique sires (i.e., testing the binary outcome of whether or not an individual became a parent), and once for all dams and all sires allowing double-counting of individual dams and sires (i.e., testing the numerical outcome of number of offspring produced).

RESULTS

We compiled demographic records for a total of 27,080 individuals from 11 sources (research laboratories and zoos), representing 5 genera and 9 species of Callitrichinae (Table 1). Within each species, we conducted several analyses of the demographic, survival, and reproductive consequences of sibling competition. The exact sample sizes for each analysis differed, though, because not all animals were reproductively active. We also note that this dataset likely contains some variability stemming from data management protocols across institutions. We therefore discuss the outcomes of sibling interactions with the caveat that stochastic processes, including under-reporting of birth events, may impact these results. Supplementary Table 1 outlines the numbers and sexes of individuals included in each analysis.

Population Birth Sex Ratios & Litter Sizes

All species except the pygmy marmoset (Cebuella pygmaea) exhibited an overall male-biased birth sex ratio (BSR), with between 51 and 56 males being born for every 100 individuals (Table 2). However, the male bias was not statistically different from 1:1 for common marmosets (Callithrix jacchus) and emperor tamarins (Saguinus imperator). We did not find significant differences in sex ratios (compared to the overall BSR) among different litter sizes (Supplementary Table 3).

Table 2.

Birth sex ratios and sex ratios for animals that lived at least 14 days. Chi-squared goodness-of-fit tests indicate divergence from an overall 1:1 birth sex ratio. We also provide (W) effect size estimates where values of 0.10, 0.30, and 0.50 indicate small, medium, and large effects, respectively (Cohen 1988).

| Birth | ≥ 14 Days | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Species | F | M | Prop. F | Prop. M | χ2 | p | W | F | M | Prop. F | Prop. M | χ2 | p | W |

| Callimico goeldii | 1427 | 1534 | 0.482 | 0.518 | 3.867 | 0.049 | 0.036 | 1140 | 1195 | 0.488 | 0.512 | 1.296 | 0.255 | 0.024 |

| Callithrix geoffroyi | 1160 | 1283 | 0.475 | 0.525 | 6.193 | 0.013 | 0.050 | 1014 | 1052 | 0.491 | 0.509 | 0.699 | 0.403 | 0.018 |

| Callithrix jacchus | 1731 | 1800 | 0.490 | 0.510 | 1.348 | 0.246 | 0.020 | 1507 | 1508 | 0.500 | 0.500 | 0.000 | 0.999 | 0.00 |

| Cebuella pygmaea | 148 | 147 | 0.502 | 0.498 | 0.003 | 0.954 | 0.003 | 146 | 137 | 0.516 | 0.484 | 0.286 | 0.593 | 0.032 |

| Leontopithecus chrysomelas | 1625 | 1795 | 0.475 | 0.525 | 8.450 | 0.004 | 0.050 | 1493 | 1583 | 0.485 | 0.515 | 2.633 | 0.105 | 0.029 |

| Leontopithecus chrysopygus | 187 | 244 | 0.434 | 0.566 | 7.538 | 0.006 | 0.132 | 144 | 192 | 0.429 | 0.571 | 6.857 | 0.009 | 0.143 |

| Leontopithecus rosalia | 1136 | 1370 | 0.453 | 0.547 | 21.85 | <0.001 | 0.093 | 908 | 1027 | 0.469 | 0.531 | 7.318 | 0.007 | 0.061 |

| Saguinus imperator | 179 | 217 | 0.452 | 0.548 | 3.647 | 0.056 | 0.096 | 124 | 135 | 0.479 | 0.521 | 0.467 | 0.494 | 0.042 |

| Saguinus oedipus | 2553 | 2892 | 0.469 | 0.531 | 21.106 | <0.001 | 0.062 | 2185 | 2411 | 0.475 | 0.525 | 11.113 | <0.001 | 0.049 |

| Overall | 10146 | 11282 | 0.473 | 0.527 | 8661 | 9240 | 0.484 | 0.516 | ||||||

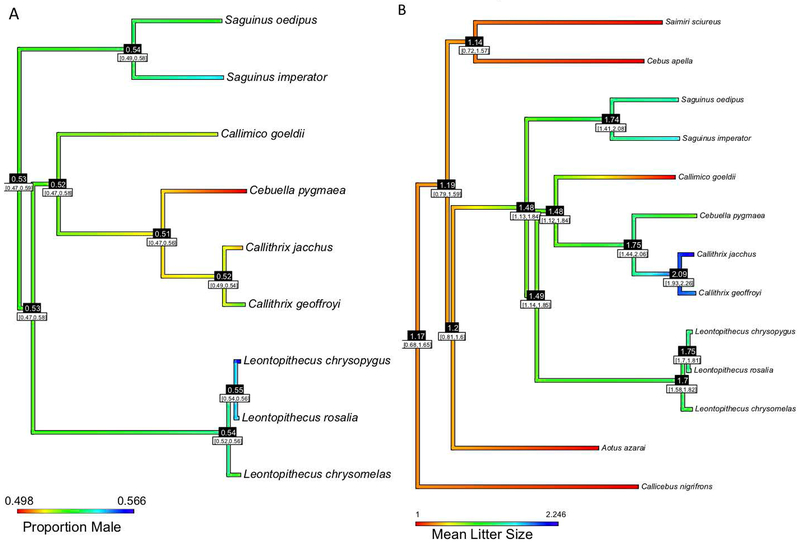

We also performed ancestral state reconstructions to investigate and visualize the variation in population BSR (Figure 1a) and mean litter sizes (Figure 1b) across the callitrichine lineage. This technique can provide information about the inferred evolutionary history of traits. Two lion tamarin species (i.e., Leontopithecus rosalia and Leontopithecus chrysomelas) seemed to have evolved a high skew in overall sex ratio from an evolutionary history of a more equal distribution. In contrast to the more divergent Leontopithecus spp., Callithrix species were closer to 50%.

Figure 1.

Ancestral state reconstruction of (A) sex ratios and (B) mean litter sizes in Callitrichine species on a maximum likelihood tree from (Garbino and Martins-Junior, 2018), with L. chrysopygus added from information in (Mundy & Kelly, 2001). (A) warmer colors indicate birth sex ratios (BSR) that are closer to equality (1:1), whereas cooler colors indicate a male-biased sex ratio. (B) Warmer colors indicate a greater likelihood of producing singletons, whereas cooler colors represent larger litters. Numbers at nodes indicate inferred ancestral states, with a 95% confidence interval in brackets.

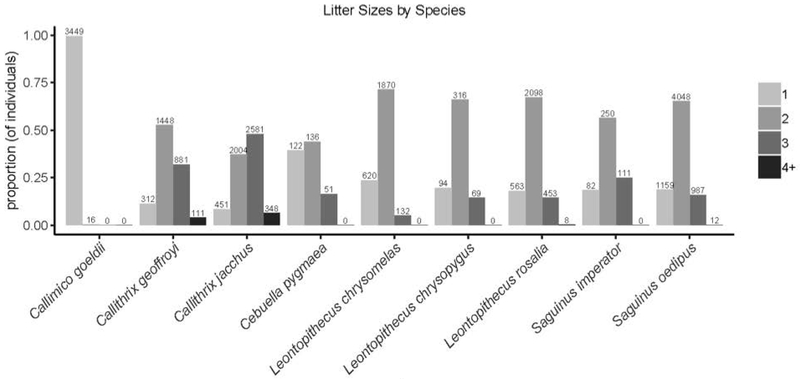

Regarding litter sizes, callitrichines gave birth to litters ranging from 1-6 individuals (Figure 2; Supplementary Table 4). At one end of this spectrum, Callimico births were predominantly represented by singletons, whereas, Callithrix species exhibited the largest litter sizes, with 2.25 representing the average litter size in these genera. The Saguinus and Leontopithecus spp. fell between these two extremes. The modal litter size was two in all species except Callimico and Cebuella pygmaea, for both of whom singleton litters were most common (i.e., in counting litters, litters of one offspring were more common than litters with two offspring).

Figure 2.

Callitrichines frequently have litters of 2-4 offspring. Proportions and counts for individuals born into litter sizes categories (i.e., singleton, twins, triplets, and quad+) by species. “4+” category includes individuals born into quadruplet, quintuplet, and sextuplet litters. Y-axis is proportion of individuals born (i.e., not proportion of litters birthed).

Litter Distributions: Sex Composition

The sex distributions of neither twin nor triplet litters (i.e., MM:MF:FF or MMM:MMF:MFF:FFF) differed from the expected values based on the overall BSR observed in each callitrichine species (Table 3).

Table 3.

Chi-squared goodness-of-fit test comparing the observed versus the expected counts of twin (i.e., FF, MF, MM) and triplet (i.e., MMM:MMF:MFF:FFF) litters based on the overall birth sex ratios for each species. Litter distributions in callitrichines did not diverge from the expected values.

| Species | Prop. Males | Prop. Females | Twin Litters | Triplet Litters | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| χ2 | df | p | χ2 | df | p | |||

| Callithrix geoffroyi | 0.525 | 0.475 | 0.793 | 2 | 0.673 | 2.069 | 3 | 0.558 |

| Callithrix jacchus | 0.510 | 0.490 | 1.343 | 2 | 0.511 | 1.059 | 3 | 0.787 |

| Cebuella pygmaea | 0.498 | 0.502 | 2.794 | 2 | 0.247 | 3.269 | 3 | 0.352 |

| Leontopithecus chrysomelas | 0.525 | 0.475 | 0.610 | 2 | 0.737 | 1.285 | 3 | 0.733 |

| Leontopithecus chrysopygus | 0.566 | 0.434 | 0.765 | 2 | 0.682 | 1.637 | 3 | 0.651 |

| Leontopithecus rosalia | 0.547 | 0.453 | 2.253 | 2 | 0.324 | 0.380 | 3 | 0.944 |

| Saguinus imperator | 0.548 | 0.452 | 0.695 | 2 | 0.706 | 0.193 | 3 | 0.979 |

| Saguinus oedipus | 0.531 | 0.469 | 2.879 | 2 | 0.237 | 1.996 | 3 | 0.573 |

Survivorship

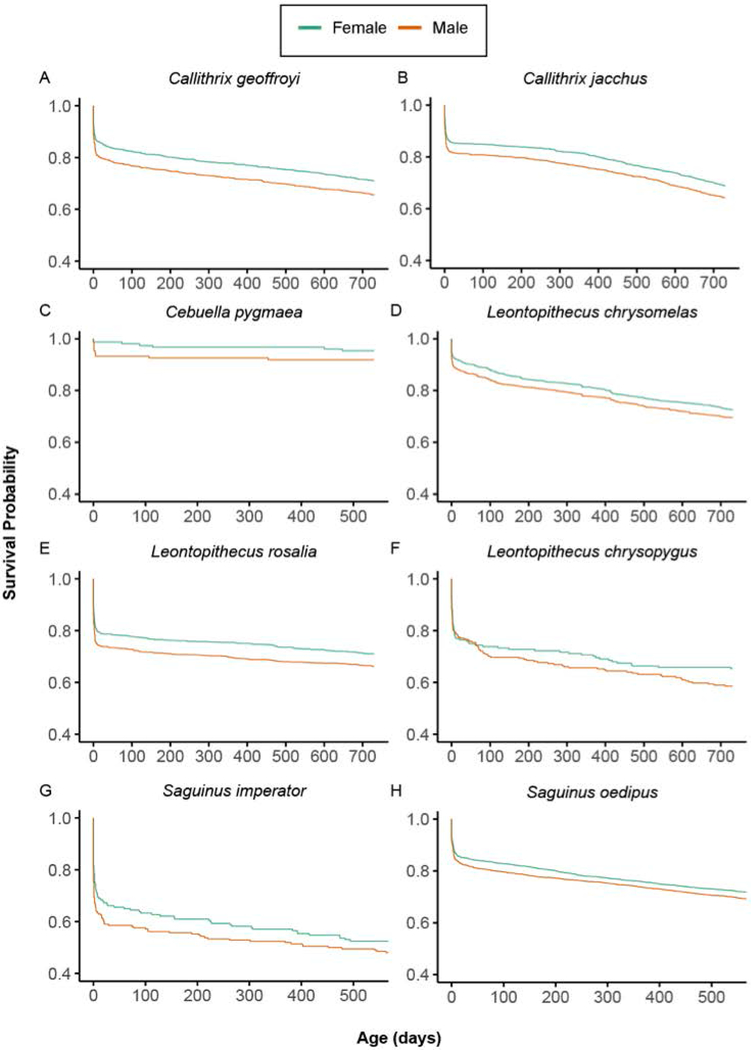

Litter type (same-sex or mixed-sex) significantly impacted survivorship in a single species – Leontopithecus chrysomelas (Supplementary Table 5; Supplementary Figure 1). For members of this species, isosexual females exhibited significantly higher survivorship than all other groups. Survivorship based on litter types did not differ for the other species. However, while not statistically significant, isosexual females exhibited the highest survivorship probabilities for all the species (Supplementary Table 6; Supplementary Figure 1). Irrespective of litter type, males and females, exhibited differences in the survival in the following species: Callithrix geoffroyi and Leontopithecus rosalia. By contrast, survivorship profiles between males and females were indistinguishable for Callithrix jacchus, Leontopithecus chrysomelas, Leontopithecus chrysopygus, Cebuella pygmaea, Saguinus imperator, and Saguinus oedipus (Supplementary Table 7; Figure 3). In the species in which significant differences in survivorship between the sexes existed, females exhibited a higher probability of surviving to sexual maturity than did males. Litter size was the strongest predictor of survivorship across the callitrichines (Supplementary Table 5; Supplementary Figure 2). In all species surveyed, mortality increased with litter size (Supplementary Table 8; Supplementary Figure 2). Histograms with age at death for each species are shown in Supplementary Figure 3. The pygmy marmoset (Cebuella pygmaea) had unusually high survivorship (Figure 3C), which may be an artefact of the studbook records or of life in captivity.

Figure 3.

Females tend to have higher survivorship than males. Survivorship profiles of males and females from birth to sexual maturity for each callitrichine species. Females exhibited significantly higher survival probabilities to sexual maturity in Callithrix geoffroyi and Leontopithecus rosalia, whereas survivorship profiles between males and females were statistically indistinguishable for Callithrix jacchus, Leontopithecus chrysopygus, Leontopithecus chrysomelas, Cebuella pygmaea, Saguinus imperator, and Saguinus oedipus.

Intergenerational Effects

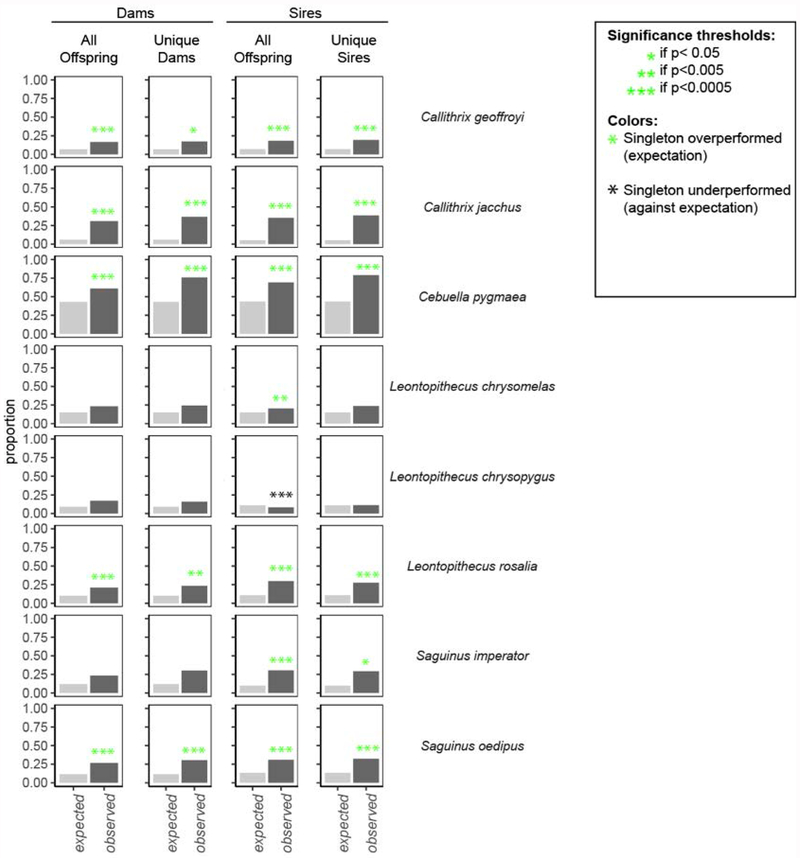

For the majority of callitrichine species, singletons outperformed individuals born in a litter on two measures of reproductive output. In both males and females, singletons gave rise to a disproportional percentage of all offspring and were overrepresented among unique sires and dams compared to litter-born peers (Chi-square Goodness of Fit; Figure 4; Supplementary Table 9).

Figure 4.

For most species, singletons had a better reproductive performance than litter-born individuals. (A) Singleton dams bore more offspring than expected for five species: Callithrix geoffroyi, Callithrix jacchus, Cebuella pygmaea, Leontopithecus rosalia, and Saguinus oedipus. (B) Singletons were overrepresented among unique dams for five species: Callithrix geoffroyi, Callithrix jacchus, Cebuella pygmaea, Leontopithecus rosalia, and Saguinus oedipus. (C) Singleton sires fathered more offspring than expected 7 of 8 species, with the opposite trend in Leontopithecus chrysopygus. (D) Singletons were overrepresented among unique sires for 6 of 8 species: Callithrix geoffroyi, Callithrix jacchus, Cebuella pygmaea, Leontopithecus rosalia, Saguinus imperator, and Saguinus oedipus. For p-values, χ2 statistics, counts, and effect sizes see Supplementary Table 9.

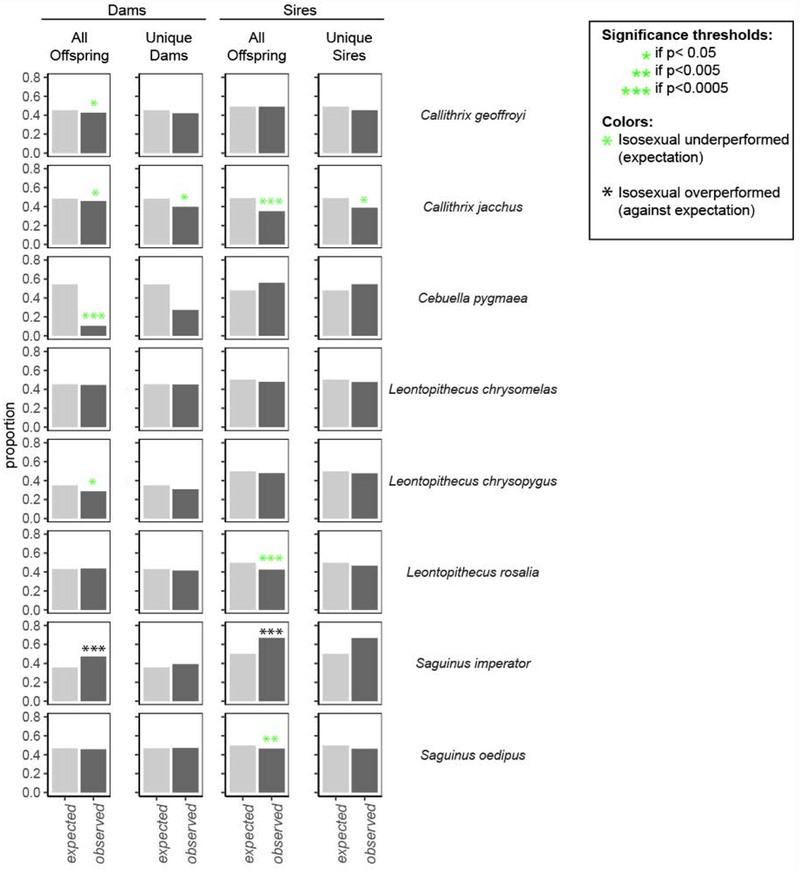

For some, but not all, callitrichine species, isosexually-born individuals significantly underperformed on two measures of reproductive output (Chi-square Goodness of Fit; Figure 5; Supplementary Table 10). Isosexual parents gave rise to fewer offspring than expected for 4 species (dams) and 3 species (sires), more offspring than expected for Saguinus imperator (both sires and dams), and otherwise did not differ from expectations. We looked at all individuals and whether or not they became parents; we found that the proportion of parents who were born into isosexual litters was lower than expected for C. jacchus for both sires and dams. Taken together, this suggests a reproductive disadvantage for individuals born into isosexual litters. In cases where the observed proportion did not significantly deviate from expected, trends in the majority of cases supported this hypothesis.

Figure 5.

For some species, parents born into an isosexual litter had a worse reproductive performance than parents born into a mixed-sex litter. (A) Isosexual dams bore fewer offspring than expected for four species – Callithrix geoffroyi, Callithrix jacchus, Cebuella pygmaea, and Leontopithecus chrysopygus – but more than expected for one species, Saguinus imperator. (B) Isosexual females became dams at the expected rate for all species except Callithrix jacchus, where they were underrepresented. (C) Isosexual sires bore fewer offspring than expected for three species – Callithrix jacchus, Leontopithecus rosalia, and Saguinus oedipus but more than expected for Saguinus imperator. (D) Isosexual males became sires at the expected rate for all species except Callithrix jacchus, for which they were underrepresented. For p-values, χ2 statistics, counts, and effect sizes see Supplementary Table 10.

DISCUSSION

Results Summary

We analyzed whether litter size and sex composition impact survivorship and reproduction in callitrichine primates, using a large dataset of captive animals from 9 species (n=27,080 individuals). Litter size, irrespective of sibling sex, showed the strongest effect on callitrichine survival and reproduction: individuals born as singletons are more likely to survive and reproduce, perhaps due to the absence of sibling competition with litter-born peers or variation in processes associated with maternal energy allocation. In addition to litter size, we found small effects of litter sex composition (isosexual vs. mixed-sex) on reproductive outcomes: isosexual parents gave rise to a significantly lower proportion of offspring than expected for 4 species (dams) and 3 species (sires). The majority of nonsignificant trends supported this observation, but in one species with a low sample size (Saguinus imperator) isosexual sires and dams significantly overperformed reproductively. Unlike litter size, litter sex composition generally did not impact survivorship from birth to sexual maturity. Although most mammals have more isosexual litters than expected, here we found that all but one species (Cebuella pygmaea) have the expected distributions of litter sex compositions. In addition to analyses of litter characteristics, we confirmed a male-biased BSR for all but three species and found that females had higher probabilities of survival to sexual maturity (although these differences were statistically significant for only two species: Callithrix geoffroyi and Leontopithecus rosalia).

Taken together, these data illuminate cross-species patterns in callitrichine diversity and reveal that sibling interactions may impose lasting effects in litter-bearing primates (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Sibling competition shapes survival and reproductive outcomes in captive callitrichine monkeys. (A) Phylogeny of callitrichine species included in this study. (B) Individuals born in a mixed-sex litter outperformed isosexually-born individuals (i.e., those born in all-male or all-female litters): i.e., isosexual monkeys were significantly underrepresented among parents. (C) Singletons significantly outperformed litter-born individuals in two metrics of reproductive performance: i.e., singletons produced more offspring and were overrepresented as parents compared to their litter-born peers. (D) From birth to adulthood, the risk of mortality increases with litter size. (E) In contrast to the clear relationship between litter size and mortality risk, the sex composition of litters does not impact survivorship in the majority of captive callitrichines.

Population Sex Ratios & Litter Sizes

All but one species in our sample exhibited male-biased BSR, although three species did not significantly diverge from the expected 1:1 BSR (Callithrix jacchus, Cebuella pygmaea, and Saguinus imperator; Table 2). Biased birth sex ratios are typical in mammals (Clutton-Brock & Iason, 1986; Faust & Thompson, 2000; Thogerson et al., 2013), including callitrichines (e.g., Leontopithecus rosalia (Rapaport, Kloc, Warneke, Mickelberg, & Ballou, 2013); Saguinus oedipus (Boulton & Fletcher, 2015), Callithrix jacchus (Poole & Evans, 1982); but see (Rothe et al., 1992)). Some of the callitrichine species surveyed here, though, exhibited skews of relatively large magnitude (Figure 1A; Table 2). Evolutionary processes, including optimal sex allocation strategies (Clark, 1978; Clutton-Brock & Iason, 1986; Fisher, 1930; Hamilton, 1967; Silk, 1984), higher expected fitness returns from males due to male alloparenting (Emlen, 1982; Emlen, Emlen, & Levin, 1986; Silk & Brown, 2008), or higher male mortality (thus selecting for an overproduction of males at birth; (Clutton-Brock & Iason, 1986)) could be evoked to explain instances of such pronounced skews. However, future surveys exploring the adaptive value of producing sons versus daughters (e.g., via multi-generation pedigrees (Thogerson et al., 2013)) are needed to assess whether the skews observed here actually represent adaptive sex allocation strategies rather than conserved mammalian traits.

Altogether, the ancestral state reconstruction on litter size including four outgroup species supported the commonly held notion that callitrichines evolved twinning from singleton-bearing ancestors and that Callimico evolved singleton births secondarily from twinning ancestors (Figure 1B).

Relaxation of Mixed-Sex Constraints

Unlike many mammals, isosexual litters are not over-represented in callitrichines; it is interesting to speculate that this might be evidence that there are few, if any, monozygotic twins (which are necessarily same-sex). We did not detect survival or reproductive costs of being born into a mixed-sex litter for either males or females (Supplementary Figure 1). This finding recapitulates a growing literature which espouses that callitrichines, unlike other litter-bearing mammals (Hackländer & Arnold, 2012; Korsten, Clutton-Brock, Pilkington, Pemberton, & Kruuk, 2009; Monclús & Blumstein, 2012; Ryan & Vandenbergh, 2002), have evolved mechanisms which shield females from brother-derived masculinization (Bradley et al., 2016; French et al., 2016). This is true even in wild golden lion tamarins (Leontopithecus rosalia): individuals from mixed-sex litters were indistinguishable from those from isosexual litters in several morphological (growth to maturity and adult body size), survival (lifetime survivorship), and reproductive metrics (age at first reproduction, reproductive rates, and reproductive tenures; (Frye, B.M., Hankerson, Sears, Tardif, & Dietz, n.d.). Taken together, these results suggest that selection has enabled callitrichines to circumvent the detriments of female masculinization that are characteristic of other litter-bearing mammals.

Other work outlines that callitrichines may exhibit subtle, while not necessarily deleterious, differences based on the sex composition of their litters. For example, Callithrix jacchus infants from mixed-sex litters weighed less than isosexual monkeys, and both males and females born with brothers exhibit delayed developmental trajectories (Frye et al., 2019). Further, mature Callithrix jacchus females born into mixed-sex litters produce proportionally more stillborns than do females born into isosexual litters (Rutherford et al., 2014). Additional research investigating developmental trajectories and fine-scaled measures of reproductive performance (e.g., fetal reabsorption, abortions, and stillbirth) might reveal how such early effects pose lasting constraints across callitrichine species.

Intergenerational Effects on Reproductive Output

In general, we found that singletons produced more offspring, and were overrepresented among parents, compared to litter-born peers (Figure 4; Supplementary Figure 4; Supplementary Table 9). Management practices are unlikely to explain these results. That is, while it is true that many protocols rarely allow more than one individual per litter to breed, owing to genetic or logistical reasons (Ballou, 1996), we cannot identify any reason why singletons would be preferentially selected as breeders. Instead, competition within a group may mean that individuals born with siblings have a lower chance of reproducing than do singletons. Sibling competition for resources and reproduction could explain the relative reproductive advantages of singletons, who do not have to compete with same-aged littermates at any ontogenetic stage. Additionally, singletons tend to be heavier at birth than individuals born with littermates especially triplets and above (Saguinus spp. and Callithrix jacchus: (Jaquish, Gage, & Tardif, 1991); Callithrix jacchus: (Lunn, 1983; Tardif & Bales, 2004).

Two additional factors may explain the difference between singletons and their litter-born peers. First, singletons may receive significantly more resources from family members than do young that are raised alongside littermates. If so, singleton offspring may enjoy developmental advantages that ultimately translate into superior reproductive performance. Second, perhaps singletons are relatively more robust and high-quality, and thus more reproductively successful. Such “robustness” of singletons may stem from variation in maternal energy allocation. For example, Tardif et al. (2001) discovered that common marmoset twins born to smaller-than-average dams received relatively poorer milk (i.e., lower milk fat and lower gross energy) than twins born to heavier dams (Tardif, Power, Oftedal, Power, & Layne, 2001). This disparity translated into slower growth for twins. However, maternal size did not impact growth in singletons. These findings suggest that singleton offspring may be less-restricted by maternal energy allocation limitations than offspring born with one or more siblings.

In some cases, we found that individuals born in isosexual litters were significantly underrepresented among parents (and all nonsignificant trends were in this direction; Figure 5; Supplementary Table 10). Callithrix jacchus, the species for which we had the largest dataset, exhibited the strongest effect: isosexual individuals were underrepresented for both dams and sires (Figure 5). There is one exception: isosexual individuals of Saguinus imperator significantly overperformed reproductively (Figure 5). While stochastic variation may explain reproductive underperformance by isosexuals, it also is possible that competition between same-sex siblings limits the reproductive potential of individuals born in isosexual litters compared to those born in mixed-sex litters. There is some evidence from other species for enhanced competition among isosexual litters (hyenas: (Golla et al., 1999), humans: (Ji et al., 2013; Nitsch, Faurie, & Lummaa, 2012). Through either prenatal biological competition or postnatal social competition, perhaps marmosets born in isosexual litters are disadvantaged. If sibling competition explains why isosexual animals underperform reproductively, why do isosexual male and female Saguinus imperator individuals overperform? Is this merely random variation, potentially due to a low sample size for this species (N(unique isosexual sires) = 18; N(unique isosexual dams) = 11; Supplementary Table 10), or does some aspect of Saguinus imperator reproduction favor isosexuals? This is a fascinating topic for future research.

Limitations and Future Directions

There are several potential limitations to this study that merit consideration and could be addressed in future work. Foremost, this demographic study is based on captive animals from zoos and laboratories, which are relatively benign environments. These animals may be well-fed and sedentary compared to wild populations where selective forces are different. For example, litter sizes may be smaller in the wild due to food constraints and the threat of predation. Additionally, selective breeding may have impacted reproductive performance for these animals. Future work validating our findings in wild populations is needed to more fully understand the fitness consequences of sibling interactions.

Further, this is a broad-scale demographic analysis, rather than a fine-scale mechanistic analysis. Adding information about individuals’ physical traits, health, and social grouping to these data likely would provide additional insights into the mechanisms mediating survival and reproduction.

Other questions may explore whether subtle competition among same-sex litters is driving down the proportion of isosexual litters (compared to what is seen in most other animals). Social grouping data could clarify the differences between same-aged sibling relationships and old-to-young relationships. Further, detailed analysis of survivorship during specific ontogenetic stages may reveal shifts in mortality risks between the sexes across the life course. Lastly, marmosets have a high degree of microchimerism between siblings; documenting the extent of chimerism and correlating this with measures of reproductive output and lifetime health may answer unresolved questions about the evolutionary impact of extensive chimerism among siblings (Haig, 1999).

Altogether, we document broad demographic trends using an unusually large dataset of captive animals. This adds to a robust literature on captive breeding programs in zoos, which is critical for conservation programs. Further, this work illustrates that carefully kept zoo and laboratory records represent a largely untapped treasure for biological inquiry. Callitrichines are an excellent clade for future investigations of parental allocation strategies and intra-familial cooperation and conflict.

Supplementary Material

RESEARCH HIGHLIGHTS.

Singletons have higher survivorship than litter-born monkeys and outperform their litter-born peers on two measures of reproductive success.

Offspring born into mixed-sex litters reproductively outperform those born in all-male or all-female litters in many species, suggesting that same-sex competition may limit fitness outcomes.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We are very grateful to Rahel Brügger, who assisted with extracting data from the University of Zurich dataset. We would also like to extend our sincere thanks to the animal care staffs and zookeepers who provided and continue to provide excellent care to marmosets, tamarins, and lion tamarins living in captivity. We would also like to thank the Writers Guild at Clemson University for their comments on previous versions of this manuscript. We also extend our thanks to Kathy West for providing the beautiful photo that accompanies this work. DEM conducted this research with Government support under and awarded by DoD, Air Force Office of Scientific Research, National Defense Science and Engineering Graduate (NDSEG) Fellowship, 32 CFR 168a. DEM. is also supported by a Theodore H. Ashford Graduate Fellowship in the Sciences.

Grant Number: P51 OD011133

REFERENCES

- Abbott DH (1993). Comparative aspects of the social suppression of reproduction in female marmosets and tamarins. Marmosets and Tamarins: Systematics, Behaviour and Ecology, 152–163. [Google Scholar]

- Ballou JD (1996). Small population management: contraception of golden lion tamarins Contraception in Wildlife. Edwin Mellen Press, New York, New York, 349–358. [Google Scholar]

- Benjamini Y, & Hochberg Y (1995). Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society. Series B (Methodological), 289–300. [Google Scholar]

- Bicca-Marques JC (2003). Sexual selection and foraging behavior in male and female tamarins and marmosets. Sexual Selection and Reproductive Competition in Primates: New Perspectives and Directions, 455–475. [Google Scholar]

- Boulton RA, & Fletcher AW (2015). Do mothers prefer helpers or smaller litters? Birth sex ratio and litter size adjustment in cotton-top tamarins (Saguinus oedipus). Ecology and Evolution, 5(3), 598–606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Box HO, & Hubrecht RC (1987). Long-term data on the reproduction and maintenance of a colony of common marmosets (Callithrix jacchus jacchus) 1972-1983. Laboratory Animals, 21(3), 249–260. 10.1258/002367787781268747 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradley BJ, Snowdon CT, McGrew WC, Lawler RR, Guevara EE, McIntosh A, & O’Connor T (2016). Non-human primates avoid the detrimental effects of prenatal androgen exposure in mixed-sex litters: combined demographic, behavioral, and genetic analyses. American Journal of Primatology, 78(12), 1304–1315. 10.1002/ajp.22583 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bütikofer A, Figlio DN, Karbownik K, Kuzawa CW, & Salvanes KG (2019). Evidence that prenatal testosterone transfer from male twins reduces the fertility and socioeconomic success of their female co-twins. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 10.1073/pnas.1812786116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark AB (1978). Sex ratio and local resource competition in a prosimian primate. Science, 201(4351), 163–165. 10.1126/science.201.4351.163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clutton-Brock TH, & Iason GR (1986). Sex ratio variation in mammals. The Quarterly Review of Biology, 61(3), 339–374. 10.1086/415033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox DR (1972). Regression Models and Life-Tables. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society: Series B (Methodological), 34(2), 187–202. 10.1111/j.2517-6161.1972.tb00899.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- De Moura ACA (2003). Sibling Age and Intragroup Aggression in Captive Saguinus midas midas. International Journal of Primatology, 24(3), 639–652. 10.1023/a:1023748616043 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Díaz-Muñoz SL, & Bales KL (2015). “Monogamy” in Primates: Variability, Trends, and Synthesis: Introduction to special issue on Primate Monogamy. American Journal of Primatology, 78(3), 283–287. 10.1002/ajp.22463 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Digby LJ, Ferrari SF, & Saltzman W (2011). The role of competition in cooperatively breeding species Primates in Perspective. Oxford University Press, New York, 85–106. [Google Scholar]

- EAZA Husbandry Guidelines. (2010). EAZA Husbandry Guidelines for Callitrichidae – 2 Taxon. Retrieved from http://www.marmosetcare.com/downloads/EAZA_HusbandryGuidelines.pdf

- Emlen ST (1982). The evolution of helping. I. An ecological constraints model. The American Naturalist, 119(1), 29–39. 10.1086/283888 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Emlen ST, Emlen JM, & Levin SA (1986). Sex-ratio selection in species with helpers-at-the-nest. The American Naturalist, 127(1), 1–8. 10.1086/284463 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan FY (2017). powerAnalysis: Power Analysis in Experimental Design. R package version 0.2.1. [Google Scholar]

- Faust LJ, & Thompson SD (2000). Birth sex ratio in captive mammals: Patterns, biases, and the implications for management and conservation. Zoo Biology. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Felsenstein J (1985). Phylogenies and the Comparative Method. The American Naturalist, 125(1), 1–15. 10.1086/284325 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher RA (1930). The Genetical Theory of Natural Selection: A Complete Variorum Edition. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- French JA, Frye B, Cavanaugh J, Ren D, Mustoe AC, Rapaport L, & Mickelberg J (2016). Gene changes may minimize masculinizing and defeminizing influences of exposure to male cotwins in female callitrichine primates. Biology of Sex Differences, 7(1), 28 10.1186/s13293-016-0081-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- French JA, & Inglett BJ (1989). Female-female aggression and male indifference in response to unfamiliar intruders in lion tamarins. Animal Behaviour. 10.1016/0003-3472(89)90095-X [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- French JA, Mustoe AC, Cavanaugh J, & Birnie AK (2013). The influence of androgenic steroid hormones on female aggression in “atypical” mammals. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 10.1098/rstb.2013.0084 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frye BM, Hankerson SJ, Sears MW, Tardif SD, & Dietz JM (n.d.). Beyond sibling sex: the role of sex allocation in a cooperatively breeding primate. In prep.

- Frye BM, Rapaport LG, Melber T, Sears MW, & Tardif SD (2019). Sibling sex, but not androgens, shapes phenotypes in perinatal common marmosets (Callithrix jacchus). Scientific Reports, 9(1), 1100 10.1038/s41598-018-37723-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garber PA, Ón FE, Moya L, & Pruetz JD (1993). Demographic and reproductive patterns in moustached tamarin monkeys (Saguinus mystax): Implications for reconstructing platyrrhine mating systems. American Journal of Primatology. 10.1002/ajp.1350290402 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garber PA, Porter LM, Spross J, & Di Fiore A (2015). Tamarins: Insights into monogamous and non-monogamous single female social and breeding systems. American Journal of Primatology, 78(3), 298–314. 10.1002/ajp.22370 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garbino GST, & Martins-Junior AMG (2018). Phenotypic evolution in marmoset and tamarin monkeys (Cebidae, Callitrichinae) and a revised genus-level classification. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution, 118, 156–171. 10.1016/j.ympev.2017.10.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golla W, Hofer H, & East ML (1999). Within-litter sibling aggression in spotted hyaenas: effect of maternal nursing, sex and age. Animal Behaviour, 58(4), 715–726. 10.1006/anbe.1999.1189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hackländer K, & Arnold W (2012). Litter sex ratio affects lifetime reproductive success of free-living female Alpine marmots Marmota marmota. Mammal Review, 42(4), 310–313. 10.1111/j.1365-2907.2011.00199.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Haig D (1999). What is a marmoset? American Journal of Primatology, 49(4), 285–296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton WJ (1967). Extraordinary sex ratios. Science, 156, 477–488. 10.1126/science.156.3774.477 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henry MD, Hankerson SJ, Siani JM, French JA, & Dietz JM (2013). High rates of pregnancy loss by subordinates leads to high reproductive skew in wild golden lion tamarins (Leontopithecus rosalia). Hormones and Behavior, 63(5), 675–683. 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2013.02.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaquish CE, Gage TB, & Tardif SD (1991). Reproductive factors affecting survivorship in captive Callitrichidae. American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 10.1002/ajpa.1330840306 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaquish CE, Tardif SD, Toal RL, & Carson RL (1996). Patterns of prenatal survival in the common marmoset (Callithrix jacchus). Journal of Medical Primatology, 25(1), 57–63. 10.1111/j.1600-0684.1996.tb00194.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ji T, Wu JJ, He QQ, Xu JJ, Mace R, & Tao Y (2013). Reproductive competition between females in the matrilineal Mosuo of southwestern China. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 368(1631). 10.1098/rstb.2013.0081 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kassambara A, & Kosinski M (2018). survminer: Drawing Survival Curves Using “ggplot2.” [Google Scholar]

- Kleiman DG (1979). Parent-Offspring Conflict and Sibling Competition in a Monogamous Primate. The American Naturalist. 10.2307/2678832 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kohler IV, Preston SH, & Lackey LB (2006). Comparative mortality levels among selected species of captive animals. Demographic Research, 15, 413–434. 10.4054/demres.2006.15.14 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Korsten P, Clutton-Brock T, Pilkington JG, Pemberton JM, & Kruuk LEB (2009). Sexual conflict in twins: male co-twins reduce fitness of female Soay sheep. Biology Letters, 5(5), 663–666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee ET, & Wang JW (2003). Statistical Methods for Survival Data Analysis Wiley Series in Probability and Statistics. John Wiley & Sons, Inc; 10.1002/0471458546 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Leutenegger W (1979). Evolution of Litter Size in Primates. The American Naturalist, 114(4), 525–531. 10.1086/283499 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lunn SF (1983). Body weight changes throughout pregnancy in the common marmoset Callithrix jacchus. Folia Primatologica. 10.1159/000156132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mittermeier RA, Rylands AB, & Wilson DE (2013). Handbook of the Mammals of the World Volume 3 Primates. (Mittermeier RA, Rylands AB, & Wilson DE, Eds.). Barcelona: Lynx Edicions. [Google Scholar]

- Monclús R, & Blumstein DT (2012). Litter sex composition affects life-history traits in yellow-bellied marmots. Journal of Animal Ecology, 81(1), 80–86. 10.1111/j.1365-2656.2011.01888.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mundy NI, & Kelly J (2001). Phylogeny of lion tamarins (Leontopithecus spp) based on interphotoreceptor retinol binding protein intron sequences. American Journal of Primatology, 54(1), 33–40. 10.1002/ajp.1010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson JE, & Gemmell RT (2003). Birth in the northern quoll, Dasyurus hallucatus (Marsupialia: Dasyuridae). Australian Journal of Zoology, 51(2), 187–198. 10.1071/ZO02016 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nettle D, Andrews C, Reichert S, Bedford T, Gott A, Parker C, … Bateson M (2016). Brood size moderates associations between relative size, telomere length, and immune development in European starling nestlings. Ecology and Evolution. 10.1002/ece3.2551 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nitsch A, Faurie C, & Lummaa V (2012). Are elder siblings helpers or competitors? Antagonistic fitness effects of sibling interactions in humans. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 280(1750), 20122313. 10.1098/rspb.2012.2313 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poole TB, & Evans RG (1982). Reproduction, infant survival and productivity of a colony of common marmosets (Callithrix jacchus jacchus). Laboratory Animals, 16(1), 88–97. 10.1258/002367782780908760 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rapaport LG, Kloc B, Warneke M, Mickelberg JL, & Ballou JD (2013). Do mothers prefer helpers? Birth sex-ratio adjustment in captive callitrichines. Animal Behaviour, 85(6), 1295–1302. 10.1016/j.anbehav.2013.03.018 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Revell LJ (2012). phytools: An R package for phylogenetic comparative biology (and other things). Methods in Ecology and Evolution, 3(2), 217–223. 10.1111/j.2041-210X.2011.00169.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Revell LJ (2013). Two new graphical methods for mapping trait evolution on phylogenies. Methods in Ecology and Evolution, 4(8), 754–759. 10.1111/2041-210X.12066 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Roda SA, & Pontes ARM (1998). Polygyny and infanticide in common marmosets in a fragment of the Atlantic forest of Brazil. Folia Primatologica, 69(6), 372–376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothe H, Darms K, & Koenig A (1992). Sex ratio and mortality in a laboratory colony of the common marmoset (Callithrix jacchus). Laboratory Animals, 26(2), 88–99. 10.1258/002367792780745922 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutherford JN, DeMartelly VA, Layne Colon DG, Ross CN, & Tardif SD (2014). Developmental origins of pregnancy loss in the adult female common marmoset monkey (Callithrix jacchus). PLoS ONE, 9(5), e96845 10.1371/journal.pone.0096845 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutherford JN, & Tardif SD (2008). Placental efficiency and intrauterine resource allocation strategies in the common marmoset pregnancy. American Journal of Physical Anthropology, 137(1), 60–68. 10.1002/ajpa.20846 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan BC, & Vandenbergh JG (2002). Intrauterine position effects. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 26(6), 665–678. 10.1016/S0149-7634(02)00038-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saltzman W, Digby LJ, & Abbott DH (2009). Reproductive skew in female common marmosets: what can proximate mechanisms tell us about ultimate causes? Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 276(1656), 389–399. 10.1098/rspb.2008.1374 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silk JB (1984). Local resource competition and the evolution of male-biased sex ratios. Journal of Theoretical Biology, 108(2), 203–213. 10.1016/S0022-5193(84)80066-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silk JB, & Brown GR (2008). Local resource competition and local resource enhancement shape primate birth sex ratios. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London B: Biological Sciences, 275(1644), 1761–1765. 10.1098/rspb.2008.0340 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soini P (1982). Ecology and population dynamics of the pygmy marmoset, Cebuella pygmaea. Folia Primatologica, 39(1–2), 1–21. 10.1159/000156066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tardif SD, & Bales KL (2004). Relations among birth condition, maternal condition, and postnatal growth in captive common marmoset monkeys (Callithrix jacchus). American Journal of Primatology, 62(2), 83–94. 10.1002/ajp.20009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tardif SD, Layne DG, & Smucny DA (2002). Can Marmoset Mothers Count to Three? Effect of Litter Size on Mother-Infant Interactions. Ethology, 108(9), 825–836. 10.1046/j.1439-0310.2002.00815.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tardif SD, Power M, Oftedal OT, Power RA, & Layne DG (2001). Lactation, maternal behavior and infant growth in common marmoset monkeys (Callithrix jacchus): effects of maternal size and litter size. Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology, 51(1), 17–25. 10.1007/s002650100400 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tardif SD, Smucny DA, Abbott DH, Mansfield K, Schultz-Darken N, & Yamamoto ME (2003). Reproduction in captive common marmosets (Callithrix jacchus). Comparative Medicine, 53(4), 364–368. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Therneau TM, & Grambsch PM (2000). Expected survival In Modeling Survival Data: Extending the Cox Model (pp. 261–287). Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Therneau TM, & Grambsch PM (2013). Modeling survival data: extending the Cox model. Springer Science & Business Media. [Google Scholar]

- Thogerson CM, Brady CM, Howard RD, Mason GJ, Pajor EA, Vicino GA, & Garner JP (2013). Winning the genetic lottery: biasing birth sex ratio results in more grandchildren. PLoS ONE. 10.1371/journal.pone.0067867 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward JM, Buslov AM, & Vallender EJ (2014). Twinning and survivorship of captive common marmosets (Callithrix jacchus) and cotton-top tamarins (Saguinus oedipus). Journal of the American Association for Laboratory Animal Science, 53(1), 7–11. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.