Abstract

Background and study aims The over-the-scope clip (OTSC) is a novel tool used to improve the maintenance of hemostasis for non-variceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding (NVUGIB); however, studies on the comparison with “conventional” techniques are lacking. In this study, we aimed to compare first-line endoscopic hemostasis achieved using conventional techniques with that achieved using OTSC placement for NVUGIB.

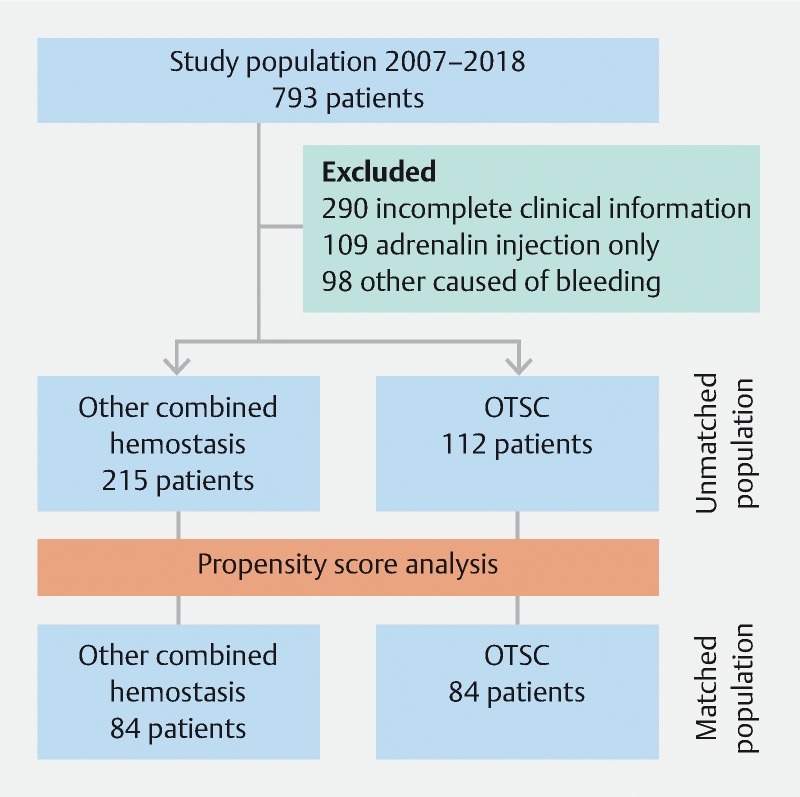

Patients and methods From January 2007 to March 2018, 793 consecutive patients underwent upper endoscopy with the hemostasis procedure. Among them, 327 patients were eligible for inclusion (112 patients had OTSC placement and 215 underwent conventional hemostasis). After propensity score matching and adjustment for confounding factors, 84 patients were stratified into the “conventional” group and 84 into the OTSC group. Patient characteristics and outcomes (rebleeding rate, mortality rate within 30 days, and adverse events) were compared between the two groups.

Results In the unmatched cohort, hemostasis with OTSC was more frequent in cases of duodenal ulcers with Forrest Ia to IIa and in patients with a higher Rockall score compared with the “conventional group”. In the matched cohort, 93 % of the patients in the “conventional group” underwent hemostasis with epinephrine + through-the-scope clip. Rebleeding events were significantly less frequent in the OTSC group (8 % vs 20 %, 95 %CI 3 – 16 vs 12 – 30; P = 0.02); however, the mortality rate in the two groups was not significantly different (6 % vs 2 %, 95 %CI 1 – 8 vs 2 – 13; P = 0.4).

Conclusions OTSC is a safe and effective tool for achieving hemostasis, and we recommend its use as the first-line therapy for lesions with a high risk of rebleeding and in patients with a high risk Rockall score.

Background

During previous decades, the treatment and management of non-variceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding (NVUGIB) have substantially improved, with endoscopic treatment being the first-line modality. After the index endoscopy, rebleeding occurs in up to 20 % of cases 1 , with a mortality rate of 10 % 2 . Recurrent bleeding after endoscopic therapy is associated with significant mortality, with a higher risk in older populations and those with multiple comorbidities. This trend may be attributable to the rising comorbidity in NVUGIB patients and the increasing use of antithrombotic drugs 3 .

Therefore, there is a need to develop additional medical therapies that will improve the maintenance of hemostasis. The European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) guidelines 4 recommend (strong recommendation, high-quality evidence) combining epinephrine injection with a second hemostasis modality (thermal contact, mechanical therapy, or injection of a sclerosing agent), especially for actively bleeding ulcers. The over-the-scope clip (OTSC ® , Ovesco Endoscopy GmbH, Tübingen, Germany) is a novel tool that can securely hold a larger volume of tissue and to a greater depth with respect to the standard through-the-scope clip (TTS) 5 6 7 . To the best of our knowledge, there are no comparative studies on the efficacy of OTSC and other hemostatic methods for first-line hemostasis. Thus, we aimed to compare first-line endoscopic hemostasis achieved using conventional techniques versus that obtained using OTSC placement for NVUGIB.

Materials and methods

Study population

From January 2007 to March 2018, 793 consecutive patients underwent upper endoscopy with the hemostasis procedure for NVUGIB. The inclusion criteria were as follows: age > 18 years, NVUGIB related to ulcers, Mallory Weiss lesion, Dieulafoy lesion, anastomotic bleeding, or angioectasia. The exclusion criteria were: incomplete clinical information, other causes of bleeding (post-sphincterotomy bleeding, post-polypectomy bleeding, malignancy, hemorrhagic gastritis, or watermelon stomach), or endoscopic hemostasis with only epinephrine injection because the ESGE recommends (strong recommendation and with high-quality evidence) that epinephrine injection therapy should not be used as endoscopic monotherapy. We collected data with regard to the following variables: age, sex, year of bleeding, number of major comorbidities (cardiac failure, ischemic heart disease, asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, diabetes mellitus, rheumatoid arthritis, liver failure, renal failure, disseminated malignancy, pneumonia, dementia, recent major operation, cerebrovascular disease, hematological malignancy, hypertension, trauma/burns, other cardiac disease, major sepsis, and/or other liver disease), anticoagulant/antithrombotic therapy, site of bleeding (esophagus, stomach, duodenum, and/or anastomosis), Forrest classification 8 , hemostasis technique (epinephrine with/without TTS, OTSC, thermic device, or sclerosing agent) for the most severe lesion according to the Forrest classification, adverse events related to the hemostasis technique used, Rockall Score 9 , Helicobacter pylori infection (assessed using biopsy or fecal antigen), rebleeding rate, rebleeding from a different site, rescue hemostasis technique (endoscopic, arterial embolization, or surgery), mortality rate within 30 days, and hospitalization (days). The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Modena on 10 May 2018 (Prot AOU 0011529/18).

Description of the procedure

All of the endoscopic procedures were performed in an inpatient setting, under anesthesia-assisted deep sedation by a single, skilled operator. Hemodynamically unstable patients were adequately resuscitated before they underwent upper endoscopy with crystalloid/colloid infusion and erythrocyte concentrate transfusion if needed. Patients with a non-cirrhosis related coagulopathy and with a prolonged prothrombin time with an international normalized ratio (INR) > 2.0 were transfused with fresh frozen plasma. The use of prothrombin complex concentrate infusions was preferred for patients with serious/life-threatening bleeding. We performed upper endoscopy once the INR was < 2.5. Before endoscopy, the patients received an intravenous bolus of proton pump inhibitor (pantoprazole 80mg), followed, if needed, by constant infusion (8 mg/hour).

Early endoscopy (within 24 hours) was performed in all cases with either a diagnostic (9.2-mm) or a therapeutic (10-mm) endoscope (Pentax Medical, Tokyo, Japan). In order to achieve endoscopic hemostasis, in addition to epinephrine injection, we used thermal modalities (argon plasma coagulation, ERBE, VIO ® , Tuebingen, Germany), mechanical therapy with TTS clip (QuickClip2, Olympus ® , Tokyo, Japan; Resolution Clip, Boston Scientific ® , Natick MA, USA; DuraClip, ConMed ® , Greenwood, USA; SureClip, Micro-Tech ® , Anna Arbor, Mi, USA) and sclerosing agents, based on the choice of the endoscopist.

When we used the OTSCs, the endoscope was extracted and equipped with the OTSC system. The OTSC size (11 or 12 mm) and type were chosen by the endoscopist. The 11-mm and 12-mm OTSCs were used with both “diagnostic” (9.2 mm, working channel 2.8 mm) gastroscope and “therapeutic” (10 mm, working channel 3.7 mm) gastroscope. The OTSC was deployed on the lesion either with suction or after tissue retraction into the cap with an anchor device. In addition, an injection of epinephrine solution was allowed (but not mandatory) before or after OTSC deployment.

Outcomes and clinical data

All of the data were retrospectively collected from medical records. The primary outcome was the rebleeding rate (defined as occurrence of hematemesis, aspiration of blood from the nasogastric tube, instability of arterial blood pressure of cardiac frequency, and a fall of > 2 g/dL in the hemoglobin level) within 24 hours or within 30 days after hemostasis (immediate or late bleeding). Secondary outcomes were the mortality rate within 30 days and adverse events related to the hemostasis technique used.

Statistical analyses

A univariable analysis was conducted for all of the baseline characteristics presented in Table 1 and Table 2 . Variables that differed significantly between other hemostasis techniques and OTSC were used to create a propensity score so as to match the “conventional” group patients with the OTSC group (1:1). A propensity score is the probability that a unit with certain characteristics will be assigned to the treatment group (as opposed to the control group). The scores can be used to reduce or eliminate selection bias in observational studies by balancing the covariates between the treatment and control groups. Propensity score matching 10 creates sets of participants for the treatment and control groups. A matched set consists of at least one participant in the treatment group and one in the control group with similar propensity scores. The goal is to approximate a random experiment. Covariates to be included in the model were related to the outcome but not to the exposure so as to increase the precision of the estimated exposure effect without increasing the bias 11 . Calculating a propensity score is an iterative process. The t test (Stata statistical software, version 13, StataCorp, College Station, TX, United States) was used to determine whether each covariate was balanced within each block. Patients were matched using the nearest-neighbor method without replacement and with a caliper width equal to 0.1.

Table 1. Characteristics of the patients in the unmatched and matched cohorts.

| Unmatched cohort | Matched cohort | |||||||||

| Characteristics | Other (215) | OTSC (112) | P value | Other (84) | OTSC (84) | P value | ||||

| n 1 | 95 %CI | n 1 | 95 %CI | n 1 | 95 %CI | n 1 | 95 %CI | |||

| Age | 71 ± 15 | 69 – 73 | 72 ± 14 | 69 – 75 | 0.5 | 70 ± 14 | 67 – 73 | 70 ± 14 | 67 – 73 | 0.8 |

| Sex (male) | 151 (70) | 63 – 86 | 88 (79) | 70 – 86 | 0.1 | 66 (79) | 68 – 87 | 66 (79) | 68 – 87 | 1 |

| Year of bleeding | 2012 ± 3 | 2015 ± 1 | 0.0001 | 2012 ± 3 | 2015 ± 1 | 0.0001 | ||||

| Major comorbidities | 0.06 | 0.1 | ||||||||

|

39 (18) | 13 – 24 | 14 (13) | 10 – 20 | 14 (17) | 9 – 26 | 14 (17) | 9 – 26 | ||

|

37 (17) | 12 – 23 | 12 (11) | 6 – 18 | 20 (24) | 15 – 34 | 9 (11) | 5 – 19 | ||

|

60 (28) | 22 – 34 | 28 (25) | 17 – 34 | 20 (24) | 15 – 34 | 18 (21) | 13 – 32 | ||

|

36 (17) | 12 – 22 | 28 (25) | 17 – 34 | 16 (18) | 11 – 29 | 23 (27) | 18 – 38 | ||

|

43 (20) | 15 – 26 | 30 (26) | 19 – 36 | 14 (17) | 9 – 26 | 20 (24) | 15 – 34 | ||

| Antithrombotics/anticoagulants | 0.3 | 0.8 | ||||||||

|

58 (27) | 21 – 33 | 26 (23) | 16 – 32 | 21 (26) | 16 – 36 | 24 (29) | 19 – 39 | ||

|

64 (29) | 24 – 36 | 40 (34) | 27 – 45 | 26 (32) | 21 – 42 | 28 (35) | 23 – 44 | ||

|

12 (6) | 3 – 9 | 3 (3) | 1 – 8 | 5 (6) | 2 – 13 | 2 (2) | 1 – 8 | ||

|

6 (3) | 1 – 6 | 3 (3) | 1 – 8 | 1 (2) | 1 – 6 | 3 (4) | 1 – 10 | ||

|

15 (7) | 4 – 11 | 2 (2) | 1 – 6 | 4 (5) | 1 – 12 | 2 (2) | 1 – 8 | ||

|

31 (14) | 10 – 20 | 22 (20) | 13 – 29 | 13 (15) | 8 – 25 | 13 (15) | 8 – 25 | ||

|

25 (12) | 8 – 17 | 14 (13) | 10 – 20 | 12 (12) | 8 – 24 | 11 (11) | 7 – 22 | ||

|

4 (2) | 1 – 5 | 2 (2) | 1 – 6 | 2 (2) | 1 – 8 | 1 (2) | 1 – 6 | ||

| Cause of bleeding | 0.0001 | 0.8 | ||||||||

|

31 (14) | 10 – 20 | 4 (4) | 1 – 9 | 7 (8) | 3 – 16 | 4 (5) | 1 – 12 | ||

|

116 (54) | 47 – 60 | 88 (79) | 70 – 86 | 61 (73) | 62 – 82 | 63 (75) | 64 – 84 | ||

|

35 (16) | 12 – 22 | 10 (9) | 4 – 16 | 9 (11) | 5 – 19 | 10 (12) | 6 – 21 | ||

|

15 (7) | 4 – 11 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

|

18 (9) | 5 – 13 | 10 (9) | 4 – 16 | 7 (8) | 3 – 16 | 7 (8) | 3 – 16 | ||

| Site of bleeding | 0.02 | 0.9 | ||||||||

|

39 (18) | 13 – 24 | 12 (11) | 6 – 18 | 9 (11) | 5 – 19 | 11 (11) | 7 – 22 | ||

|

66 (31) | 25 – 37 | 25 (22) | 15 – 31 | 26 (31) | 21 – 42 | 23 (28) | 18 – 38 | ||

|

92 (43) | 36 – 50 | 67 (60) | 51 – 69 | 42 (50) | 39 – 61 | 44 (54) | 41 – 63 | ||

|

18 (8) | 5 – 13 | 8 (7) | 3 – 14 | 7 (8) | 3 – 16 | 6 (7) | 3 – 15 | ||

| Forrest classification | 0.0001 | 0.2 | ||||||||

|

10 (5) | 2 – 8 | 11 (10) | 5 – 17 | 4 (5) | 1 – 12 | 10 (12) | 6 – 21 | ||

|

100 (47) | 40 – 53 | 48 (43) | 33 – 53 | 42 (50) | 39 – 61 | 35 (42) | 31 – 53 | ||

|

68 (32) | 25 – 38 | 53 (47) | 39 – 57 | 38 (45) | 34 – 57 | 39 (46) | 36 – 58 | ||

|

30 (13) | 10 – 19 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

|

5 (2) | 1 – 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

|

2 (1) | 1 – 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Other hemorrhagic lesions | 71 (33) | 27 – 40 | 38 (34) | 25 – 43 | 0.9 | 31 (37) | 27 – 48 | 29 (35) | 24 – 46 | 0.7 |

| Rockall score | 6.3 ± 1.7 | 6.1 – 6.5 | 7.0 ± 1.7 | 6.7 – 7.3 | 0.0007 | 6.3 ± 1.5 | 5.9 – 6.6 | 6.8 ± 1.7 | 6.4 – 7.2 | 0.06 |

ASA, acetylsalicylic acid; NSAID, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs; OTSC, over-the-scope clip; DAPT, dual antiplatelet therapy; LMWH, low molecular weight heparin; NOAC, novel oral anticoagulants; VKA, vitamin K antagonist.

Values expressed as absolute number (%) or mean ± SD.

Table 2. Characteristics of the procedures and outcomes of the unmatched and matched cohorts.

| Unmatched cohort | Matched cohort | ||||||||||

| Characteristics | Other (n = 215) | OTSC (n = 112) | P value | Other (n = 84) | OTSC (n = 84) | P value | |||||

| n 1 | 95 %CI | n 1 | 95 %CI | n 1 | 95 %CI | n 1 | 95 %CI | ||||

| Hemostatic technique | |||||||||||

|

171 (80) | 78 (93) | |||||||||

|

44 (20) | 6 (7) | |||||||||

|

53 (47) | 44 (52) | |||||||||

|

49 (44) | 32 (38) | |||||||||

|

10 (9) | 8 (10) | |||||||||

| H. pylori infection | 0.6 | 0.2 | |||||||||

|

21 (10) | 6 – 14 | 30 (27) | 19 – 36 | 33 (39) | 29 – 51 | 22 (26) | 17 – 37 | |||

|

65 (30) | 24 – 37 | 14 (12) | 7 – 20 | 8 (10) | 4 – 18 | 12 (14) | 8 – 24 | |||

|

129 (60) | 53 – 67 | 68 (61) | 51 – 70 | 43 (51) | 40 – 62 | 50 (60) | 48 – 70 | |||

| Adverse events (procedure related) | 1 (1) | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0.3 | |||||

| Rebleeding | 32 (15) | 10 – 20 | 13 (12) | 6 – 19 | 0.5 | 17 (20) | 12 – 30 | 7 (8) | 3 – 16 | 0.02 | |

| Rebleeding from other site | 2 (1) | 0 – 3 | 4 (4) | 1 – 9 | 0.2 | 1 (1) | 0 – 6 | 3 (4) | 1 – 10 | 0.6 | |

| Rescue hemostasis | 0.8 | 0.2 | |||||||||

|

19 (59) | 41 – 76 | 8 (62) | 32 – 86 | 12 (70) | 44 – 90 | 3 (42) | 10 – 82 | |||

|

6 (19) | 7 – 36 | 2 (15) | 2 – 45 | 3 (18) | 4 – 43 | 2 (29) | 4 – 71 | |||

|

7 (22) | 9 – 40 | 3 (23) | 5 – 54 | 2 (12) | 2 – 37 | 2 (29) | 4 – 71 | |||

| Mortality (death within 30 days) | 20 (9) | 6 – 14 | 8 (7) | 3 – 14 | 0.6 | 5 (6) | 2 – 13 | 2 (2) | 1 – 8 | 0.4 | |

| Recovery, days | 13 ± 19 | 10 – 16 | 15 ± 12 | 13 – 17 | 0.4 | 11 ± 10 | 9 – 13 | 15 ± 3 | 14 – 16 | 0.03 | |

OTSC, over-the-scope clip.

Values expressed as absolute number (%) or mean ± SD.

Thermal modalities, sclerosing agent.

Continuous data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation values, while the categorical variables are presented as frequencies (%). Continuous variables were compared using the Student’s t test, and categorical variables were compared with the χ 2 or the Fisher’s exact test, as appropriate. Stata version 13 was used for the statistical analyses.

Results

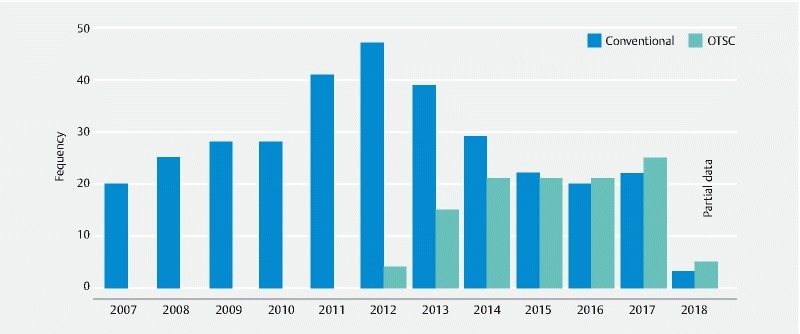

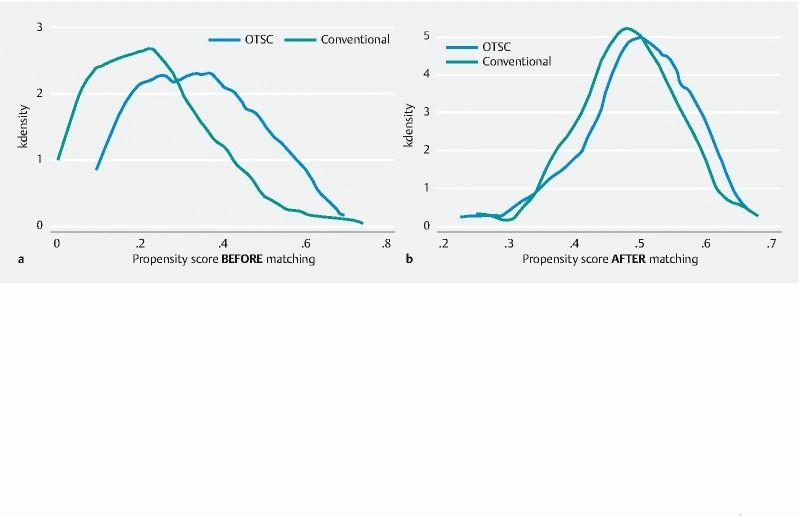

In total, 327 patients were eligible for inclusion. Of these, 112 patients had OTSC placement, and 215 underwent conventional hemostasis (epinephrine with/without TTS or thermic device or sclerosing agent). The OTSC group and the “conventional” group differed with respect to the year of bleeding, cause of bleeding, site of bleeding, Forrest classification, and Rockall score. The OTSC device was implemented in our endoscopic service ( Fig. 1 ) from 2012 with an increase in the percentage until 2017 (for 2018, there is only partial data until March 2018). Utilization of hemostasis with OTSC was more frequent in duodenal ulcers with Forrest Ia to IIa and in patients in the “conventional” group with a higher Rockall score. Adverse events related to the procedure were only reported in a case with thermal (APC) hemostasis that worsened the bleeding. In order to mitigate the effects of measurable baseline confounders, patients were matched into 84 pairs using propensity score matching. Covariates included in the model were age, sex, number of comorbidities, cause of bleeding, site of bleeding, Forrest classification, and Rockall score. The population flow chart is presented in Fig. 2 , and the baseline patient characteristics of the matched cohort are summarized in Table 1 and Table 2 . The kernel distribution of propensity scores before and after matching is shown in Fig. 3a,b .

Fig. 1.

Number of procedures performed per study year. Only partial data available for 2018. OTSC, over-the-scope clip.

Fig. 2.

Flow chart for the enrolled patients. OTSC, over-the-scope clip.

Fig. 3.

Kernel distribution of propensity scores: a before matching; b after matching.

Matched cohort

The majority of the patients in both groups were men (79 %) aged 70 ± 14 years (mean ± SD). At the time of bleeding, antithrombotics or anticoagulants were being used by most of the patients (74 % of the conventional group and 71 % of the OTSC group). The mean Rockall scores were 6.3 ± 1.5 and 6.8 ± 1.7 for the conventional and OTSC groups, respectively.

The most frequent site of bleeding was the duodenum, with the bleeding mainly being related to peptic ulcers with Forrest class Ia to IIa. Other hemorrhagic lesions with minor significance compared with the main bleeding source were diagnosed in 37 % and 35 % of cases in the “conventional” and OTSC groups, respectively. Among traditional hemostatic procedures, epinephrine + TTS was used in 93 % of cases. On the other hand, OTSC was applied alone in 52 % of all of the cases and in 38 % of cases after the injection of epinephrine. No adverse events were reported. The H.pylori status was not assessed in > 50 % of patients in both groups. Rebleeding events were less common in the OTSC group (20 % vs 8 %, 95 % confidence interval (CI) 12 – 30 vs 3 – 16; P = 0.02); however, the mortality rate of the two groups was not significantly different (6 % vs 2 %; 95 %CI 2 – 13 vs 1 – 8; P = 0.4). Rescue hemostasis was mainly managed with another endoscopic procedure (42 % vs 70 %) and less frequently with arterial embolization (29 % vs 18 %) or surgery (29 % vs 12 %) in the OTSC and “conventional” groups, respectively. Rescue hemostasis achieved with a second endoscopic procedure was managed with epinehprine + TTS, except for three patients, managed with other modalities (epinehprine + sclerosing agent) . The length of hospital stay (days) was longer in the OTSC group than in the “conventional” group (15 ± 3 vs 11 ± 10 days, 95 %CI 14 – 16 vs 9 – 13; P value 0.03).

Discussion

Despite the major advances in NVUGIB management over the past decade, including the prevention of peptic ulcer bleeding and high-dose proton pump inhibition, considerable morbidity, mortality, and health economic burdens persist. Of particular note are the rebleeding rates, one of the most crucial predictive factors of morbidity and mortality that has not significantly improved as evident from longitudinal data in the past 15 years 12 13 14 . Although several types of endoscopic treatment for NVUGIB have been described, including injection therapy, thermal coagulation, hemostatic clips, fibrin sealant (or glue), argon plasma coagulation, and combination therapy (typically injection of epinephrine combined with another treatment modality), relatively few comparative trials have been performed. Currently, most patients are being treated with either thermal coagulation therapy or hemostatic clips, with or without the addition of injection therapy.

In this study, we aimed to compare first-line endoscopic hemostasis, achieved using conventional techniques, with OTSC placement for NVUGIB in a matched cohort of patients. The OTSC system as a preliminary experience has been successfully used in patients with severe bleeding or deep wall lesions, or perforations of the gastrointestinal tract 14 .

To date, clinical data on OTSC treatment for upper gastrointestinal bleeding is limited to case series and retrospective studies 5 7 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 . The technical success rate varies from 77.8 % to 100 % when OTSC is used as first-line therapy, with a rebleeding rate of 7.4 – 13.6 %. However, patient populations differ widely with respect to the bleeding source, bleeding severity, and previous therapy. Most studies include a limited sample size and lack a control group. In our study, we tried to overcome these limitations by using propensity score analysis to balance the confounding factors between the two groups. Our study showed the efficacy of OTSC as a first-line therapy in the management of NVUGIB. The rebleeding rate was acceptably low (8 %) in the OTSC group and was lower than that in the “conventional” group ( P = 0.02). This finding is consistent with the previously reported rebleeding rates of 0 – 22 % 24 and with the observation that rebleeding following OTSC placement occurs in up to 35 % of patients receiving antithrombotic therapy 14 . In addition, data from the first randomized study found that OTSC application was more effective than standard hemostasis (TTS or thermal plus epinephrine) techniques as a rescue therapy in patients with recurrent bleeding peptic ulcer 6 . The bleeding-related mortality rate was 2 % in the OTSC group, lower than that (8 %) in the control group and occurred in patients with important comorbidities. In our experience, death occurred in patients in whom the OTSC placement was impossible or who experienced rebleeding. Unfortunately, the fatal events occurred despite the interventional radiology or surgical approaches that were performed. This would appear consistent with mortality reported in other recent studies 7 19 23 25 .

In this study, we found and confirmed that, because of their lower rebleeding rate, OTSC devices are suitable for patients with duodenal ulcers with high Forrest classification status (Forrest Ia to IIa) and a high Rockall score.

The OTSC system, being a very contractile, super-elastic nickel titanium alloy, provides tissue apposition that is far superior to that of traditional clipping. Hemostasis is achieved by a combination of the following two mechanisms: (1) sealing the blood vessel; and (2) closing off an ulcer. However, the main mechanism appears to be that of “tissue compression” that occurs by compressing the surrounding tissue around the vessel. Although it is possible to close an ulcer by applying the OTSC directly on a bleeding vessel, it is believed that the above-mentioned “tissue compression” mechanism better explains the hemostatic mechanisms.

These characteristics enable us to overcome the limitations of TTS used in the compression of limited amounts of tissue, especially in the presence of scarred and hardened tissue or inflammatory mucosa with a hemostatic effect not sufficient for large-sized vessels. In addition, standard clips often detach from these lesions and induce more bleeding by lacerating the vessel. Nevertheless, we acknowledge the limitations of the OTSC system and agree with Asokkumar et al. 26 who have identified the following three common patterns that result in OTSC failure: (1) delayed closure of OTSC occurring in lesions with large caliber arteries and those with a deep fibrotic base; (2) shallow placement of OTSC resulting from inadequate suction or premature clip deployment; and (3) misplacement of OTSC because of poor visualization, difficult anatomy, and unstable endoscope position.

This study has certain limitations. First, because of the retrospective design, selection bias and confounding factors could affect the study validity. In order to limit the selection bias, all of the consecutive patients who underwent a hemostasis procedure for NVUGIB were considered for enrollment. However, owing to the retrospective nature of the study, complete information for all of the eligible patients was not available. Thus, 30 % of the eligible patients were excluded. In order to reduce the confounding factors in the two cohorts, propensity score analysis was applied to the study design. This strategy to reduce the confounding has an unavoidable limitation because it reduces the sample size. In our study, the post-hoc power (84 patients in each group, with a 0.05 alpha error and rebleeding rates of 20 % in the conventional group and 8 % in the OTSC group) is 61.2 %, which is slightly underpowered in comparison to the standard reference value (80 %). Second, propensity score matching may lead to increased covariate imbalance called the propensity score paradox 27 . Despite progressive pruning of the matched sets, the application of a caliper width of 0.1 should avoid pruning near the lowest region of the imbalance trend. However, it is possible that the nested variables influence the outcome. For example, it was not possible to assess the severity of the comorbidities, and this could affect the outcome. Moreover, the difference between the length of recovery in the two groups could be associated with the severity of comorbidities in the patients which was not scored in this study. Furthermore, the temporal relationship with the rebleeding rate was difficult to assess because, after the introduction of the OTSC device in our center in 2012, we preferred OTSC over TTS because of its observed, although empiric, major efficacy in hemostasis. Thus, most of the control patients were those treated before 2012, and during the study period, the skill level of the operators could have changed. Thus, we suggest using OTSC as the first-line treatment for lesions with a high risk of rebleeding in patients with a high risk Rockall score. Finally, randomized controlled trials and a formal cost-effectiveness analysis are needed to determine the impact of the first-line use of OTSC in patients with high risk NVUGIB.

Footnotes

Competing interests None

References

- 1.Sostres C, Lanas A. Epidemiology and demographics of upper gastrointestinal bleeding: prevalence, incidence and mortality. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 2011;21:567–581. doi: 10.1016/j.giec.2011.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Palmer K, Atkinson S, Donnelly Met al. Acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding: management UK: National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence; 2011. Available athttps://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg141/documents/acute-upper-gi-bleeding-full-guideline2

- 3.Barada K, Abdul-Baki H, El Hajj I I et al. Gastrointestinal bleeding in the setting of anticoagulation and antiplatelet therapy. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2009;43:5–12. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0b013e31811edd13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Karstensen J G, Ebigbo A, Asbakken L et al. Nonvariceal upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage: European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) Cascade Guideline. Endosc Int Open. 2018;06:E1256–E1263. doi: 10.1055/a-0677-2084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Manno M, Mangiafico S, Caruso A et al. First-line endoscopic treatment with OTSC in patients with high-risk non-variceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding: preliminary experience in 40 cases. Surg Endosc. 2016;30:2026–2029. doi: 10.1007/s00464-015-4436-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schmidt A, Golder S, Goetz M et al. Over-the-scope clips are more effective than standard endoscopic therapy for patients with recurrent bleeding of peptic ulcers. Gastroenterology. 2018;155:674–686. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2018.05.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wedi E, Fischer A, Hochberger J et al. Multicenter evaluation of first-line endoscopic treatment with the OTSC in acute non-variceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding and comparison with the Rockall cohort: the FLETRock study. Surg Endosc. 2018;32:307–314. doi: 10.1007/s00464-017-5678-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Forrest J A, Finlayson N D, Shearmen D J. Endoscopy in gastrointestinal bleeding. Lancet. 1974;17:394–397. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(74)91770-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rockall T A, Logan R F, Devlin H B et al. Risk assessment after acute upper gastrointestinal haemorrhage. Gut. 1996;38:316–321. doi: 10.1136/gut.38.3.316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rosenbaum P R, Rubin D B. The central role of the propensity score in observational studies for causal effects. Biometrika. 1983;70:41–55. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brookhart M A, Patrick A R, Dormuth C et al. Adherence to lipid-lowering therapy and the use of preventive health services: an investigation of the healthy user effect. Am J Epidemiol. 2007;166:348–354. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwm070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jairath V, Barkun A N. Improving outcomes from acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Gut. 2012;61:1246–1249. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2011-300019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rockall T A, Logan R F, Devlin H B et al. Incidence of and mortality from acute upper gastrointestinal haemorrhage in the United Kingdom. Steering Committee and members of the National Audit of Acute Upper Gastrointestinal Haemorrhage. BMJ. 1995;311:222–226. doi: 10.1136/bmj.311.6999.222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hearnshaw S A, Logan R F, Lowe D et al. Acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding in the UK: patient characteristics, diagnoses and outcomes in the 2007 UK audit. Gut. 2011;60:1327–1335. doi: 10.1136/gut.2010.228437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kirschniak A, Subotova N, Zieker D et al. The Over-The-Scope Clip (OTSC) for the treatment of gastrointestinal bleeding, perforations, and fistulas. Surg Endosc. 2011;25:2901–2905. doi: 10.1007/s00464-011-1640-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wedi E, Gonzalez S, Menke D et al. One hundred and one over-the-scope-clip applications for severe gastrointestinal bleeding, leaks and fistulas. World J Gastroenterol. 2016;22:1844–1853. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v22.i5.1844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mönkemüller K, Peter S, Toshniwal J et al. Multipurpose use of the “bear claw” (over-the-scope-clip system) to treat endoluminal gastrointestinal disorders. Dig Endosc. 2014;26:350–357. doi: 10.1111/den.12145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Skinner M, Gutierrez J P, Neumann H et al. Over-the-scope-clip is an effective rescue therapy for severe acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Gastrointest Endosc. 2014;79:AB143. doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1365282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Richter-Schrag H-J, Glatz T, Walker C et al. First-line endoscopic treatment with over-the-scope clips significantly improves the primary failure and rebleeding rates in high-risk gastrointestinal bleeding: a single-center experience with 100 cases. World J Gastroenterol. 2016;22:9162–9171. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v22.i41.9162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Manta R, Galloro G, Mangiavillano B et al. Over-the-scope clip (OTSC) represents an effective endoscopic treatment for acute GI bleeding after failure of conventional techniques. Surg Endosc. 2013;27:3162–3164. doi: 10.1007/s00464-013-2871-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Baron T H, Song L M, Ross A et al. Use of an over-the-scope clipping device: multicenter retrospective results of the first U.S. experience (with videos) Gastrointest Endosc. 2012;76:202–208. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2012.03.250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lamberts R, Koch A, Binner C et al. Use of over-the-scope clips (OTSC) for hemostasis in gastrointestinal bleeding in patients under antithrombotic therapy. Endosc Int Open. 2017;05:E324–E330. doi: 10.1055/s-0043-104860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Manta R, Mangiafico S, Zullo A et al. First-line endoscopic treatment with over-the-scope clips in patients with either upper or lower gastrointestinal bleeding: a multicenter study. Endosc Int Open. 2018;6:E1317–E1321. doi: 10.1055/a-0746-8435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chan S M, Lau J YW. Can we now recommend OTSC as first-line therapy in case of non-variceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding? Endosc Int Open. 2017;5:E883–E885. doi: 10.1055/s-0043-111722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brandler J, Buttar N, Baruah A et al. Efficacy of over-the-scope clips in management of high-risk gastrointestinal bleeding. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;16:690–696. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2017.07.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Asokkumar R, Soetikno R, Sanchez-Yague A et al. Use of over-the-scope-clip (OTSC) improves outcomes of high-risk adverse outcome (HR-AO) non-variceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding (NVUGIB) Endosc Int Open. 2018;6:E789–E796. doi: 10.1055/a-0614-2390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ripollone J E, Huybrechts K F, Rothman K J et al. Implications of the propensity score matching paradox in pharmacoepidemiology. Am J Epidemiol. 2018;187:1951–1961. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwy078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]