Abstract

Objectives:

Parkinson’s disease (PD) is a progressive neurodegenerative disease that often impedes activities of daily living (ADL) and social functioning. Impairment in these areas can alter social roles by interfering with employment status, household management, friendships and other relationships. Understanding how PD affects social functioning can help clinicians choose management strategies that mitigate these changes.

Methods:

We conducted a mixed-methods systematic review of existing literature on social roles and social functioning in PD. A tailored search strategy in 5 databases identified 51 full-text reports that fulfilled the inclusion criteria and passed the quality appraisal. We aggregated and analyzed the results from these studies and then created a narrative summary.

Results:

Our review demonstrates how PD causes many people to withdraw from their accustomed social roles and experience deficits in corresponding activities. We describe how PD symptoms (e.g. tremor, facial masking, neuropsychiatric symptoms) interfere with relationships (e.g. couple, friends, family) and precipitate earlier departure from the workforce. Additionally, several studies demonstrated that conventional PD therapy has little positive effect on social role functioning.

Conclusions:

Our report presents critical insight into how PD affects social functioning and gives direction to future studies and interventions (e.g. couple counseling, recreational activities).

Keywords: Parkinson’s disease, quality of life, social roles, caregiver

1. Introduction

Parkinson’s disease (PD) is a progressive neurodegenerative disease characterized by motor and non-motor symptoms that impair functioning in activities of daily living (ADL) and cause changes in social functioning 1,2. Social functioning encompasses performance in specific social roles, or “expected ways of behaving,” which are established by both an individual’s personal goals and societal norms 3. In chronic illnesses, symptoms impact the ability to fulfill social roles such as employment, household management, friendships, and other relationships 4. Changes in social role functioning are particularly troublesome because satisfaction with social role performance is related to overall happiness and quality of life 5. Additionally, social isolation and loneliness is a risk factor for depression, cognitive decline, increased health care costs, and overall mortality6–9.

Quality of life (QoL) has become a frequent outcome of interest in clinical trials and is one of the most important factors for determining clinical care for people with chronic diseases 10,11. In the PD field, research on quality of life has increased and several systematic reviews describe the determinants of quality of life, economic impact of decreased quality of life in PD, how to measure quality of life, and prognostic factors related to QoL 12–15. Van Uem et al. recently published a review on health-related quality of life in patients with PD using the International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health (ICF) developed by the World Health Organization as a framework. The ICF model was designed to represent health and disability at individual and population lesvels, using the following domains: body functions and structures, activities of daily living, participation in social roles, personal features, and environmental factors 16. This review found that poor health-related quality of life was most strongly associated with social role functioning; however, there is a significant dearth of research conducted in this area compared to the other domains 17. Because no review has examined specific aspects of social functioning in PD, we conducted a mixed methods systematic review, incorporating studies estimating the association of social function with PD employing statistical methods and qualitative studies seeking to understand the construct of social functioning in PD. Because no review has examined specific aspects of social functioning in PD, we conducted a mixed-methods systematic review. We aim to describe what is currently known about social role functioning in PD.

2. Methods

2.1. Search strategy and study selection

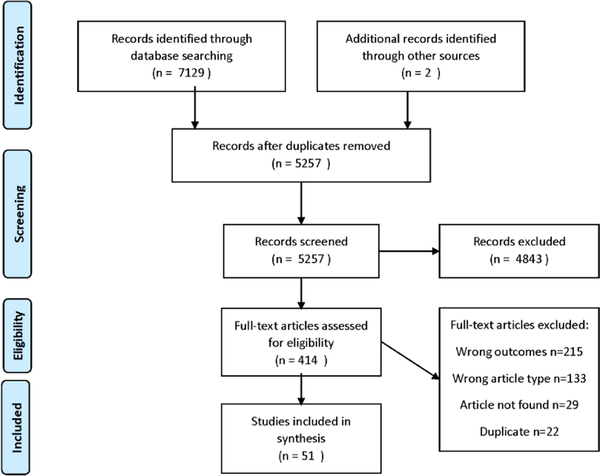

A literature search was performed in March 2018, using several MeSH terms related to social roles (Supplementary Table 1). All articles published before March 1, 2018 were included in the search, yielding 7129 articles from Pubmed (2257), Embase (3300), PsychINFO (1078), CINAHL (373) and Cochrane (121). After removing duplicates (n=1872), the titles and abstracts of the remaining 5257 articles were screened by two reviewers (JH, KP). Inclusion criteria for the full-text screening were: (1) Parkinson’s disease participants and (2) at least one outcome of the paper focused on social functioning or a social role. Articles were excluded from the review if they were not available in English or if they did not present original research. In order to provide the most comprehensive review of papers investigating social functioning we included studies employing a variety of instruments and data collection methods; due to the heterogeneity of instruments used we were unable to conduct a meta-analysis. However, as the first review conducted on a rarely studied area in PD, we believe that a review including quantitative and qualitative studies with a narrative summary of the results was most appropriate.

After the initial screening, 4843 articles were excluded, leaving 414 articles in the full text evaluation (Figure 1). The full texts were then read to confirm they met inclusion criteria. A third reviewer (MS) served as an adjudicator when there was disagreement about inclusion in the full-text evaluation. After full text review, 344 articles were excluded, leaving 70 articles for quality appraisal and data extraction. We also searched the reference sections of the articles that were included after full-text review for any additional papers that may have been missed in the database search (2 additional articles were identified).

Figure 1.

Consort diagram of the review process

2.2. Data extraction and quality appraisal of included studies

One reviewer (KP) used a quality appraisal checklist to independently evaluate the quality of the 70 articles remaining after the full-text assessment. We used the Critical Appraisal of Programme checklist for the quality appraisal 18. The checklist type was selected based on the study design. The appraisal resulted in the inclusion of 51 articles and the exclusion of 19 articles after the quality appraisal. One reviewer (KP) extracted data from the 51 articles that remained after the quality appraisal. Articles were then divided based on the type of analysis used – quantitative or qualitative.

2.3. Data Synthesis

Our mixed-methods methodology facilitated a synthesis of published results and enabled us to produce a narrative summary of existing work. Using the Cochrane procedure for narrative summary, one reviewer (KP) read through each paper and first developed a preliminary composition of the results (Supplementary Tables 2– 7)19. A combination of inductive and deductive reasoning was applied for the analysis. We employed deductive synthesis to first divide articles based on the type of social role described: couple relationship, parent/family role, work role, friendship role, social/leisure role or grouped into a general social functioning category if no specific role was described. Some papers discussed multiple roles; the information relevant to each role was extracted from the paper and categorized in the appropriate section. Then, within each group, we applied an inductive synthesis to identify patterns of topics discussed and further divide papers into a sub-theme. The data from studies were then translated using thematic analysis to describe common conclusions across different papers (within the previously defined social roles) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Summary of results from review papers

| Social Role | Sub-theme | Summary of results |

|---|---|---|

| General Social Functioning | Clinical Observations/PD Symptoms |

|

| Treatment/ Intervention Effect |

|

|

| Quality of Life/ Life Changes after PD |

|

|

| Primary Relationships/ Couple |

Clinical/PD symptoms |

|

| Relationship Satisfaction (non-sexual aspects) |

|

|

| Sexual Satisfaction |

|

|

| Treatment Effect |

|

|

| Parent/ Family Role |

Treatment/Intervention |

|

| Sharing disease/Communication |

|

|

| Relationship Satisfaction |

|

|

| Friendship Role | Number of social contacts/social connectedness |

|

| Quality of Life |

|

|

| Relationship Quality |

|

|

| Work Role | Clinical/PD Symptoms/Predictors |

|

| Housework |

|

|

| Work Unavailability/Leaving the workforce |

|

|

| Treatment/Intervention |

|

|

| Social and Leisure Role | Activity Type |

|

| Treatment/Intervention Effect |

|

|

| Clinical/PD Symptoms |

|

3. Results

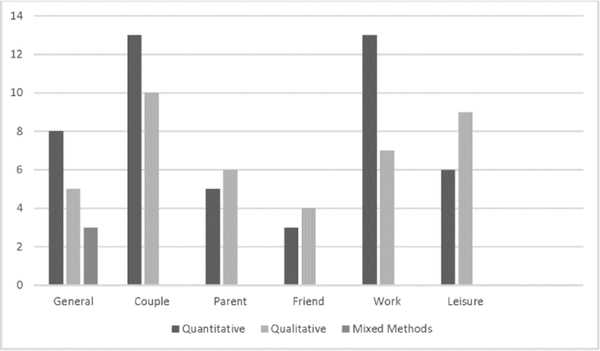

We identified 51 papers to include in our analysis, all published between 1973 and 2018. Of these, 23 papers employed primarily quantitative methods, 23 were qualitative, and 4 used a mixed-methods approach. Most study designs were cross-sectional (n=44) and the remaining articles were longitudinal (n=7). The papers included in this review either covered general social functioning (n=30) or discussed a specific social role, including the couple relationship (n=36), parent/family role (n=14), friendship role (n=9), work role (n=19), and/or social/leisure role (n=6) (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Distribution of articles based on social role examined and analysis performed

3.1. Quantitative Studies: Instruments

A wide variety of instruments were used to measure social role functioning. Some studies included full questionnaires such as the Marital Adjustment Test. Other studies included questionnaires that assessed social functioning in a subsection of the full scale, for example the Nottingham Health Profile.

3.2. Qualitative Studies: Data collection methods

All of the qualitative studies employed in-depth interviews as the main data collection method. Questions that were included in the interviews were generally open-ended (e.g. “Can you tell me what your life is like with Parkinson’s disease?”), some focused on specific social roles (e.g. “Can you describe how the disease has affected your relationship with family, friends, and your community?”), while others were broad (e.g. “How has your ‘usual state of health’ changed after diagnosis?”).

3.4. Narrative analysis of papers by social role category

3.4.1. General social functioning

General social functioning included papers (n=30) that described overall socialization or social functioning but didn’t discuss a specific social role. These articles were categorized into three sub-themes - clinical observations/PD symptoms (n=3), treatment/intervention effect (n= 9), and quality of life/life changes after PD (n=4). The quantitative study described that facial masking was associated with social functioning problems such as social rejection, although this finding was attenuated after controlling for depression 20. The qualitative studies described how communication problems (i.e. voice problems) were associated with changes in socialization such as social withdrawal 21. People living with Parkinson’s felt that PD restricted their activity, decreased their socialization, and limited their ability to have a “meaningful” social contribution 21–23. Papers describing treatments and interventions for improving Parkinson’s symptoms included “typical” PD treatments (i.e. medication and deep brain stimulation (DBS) surgery), exercise interventions (e.g. tango class), and educational programs (e.g. psychoeducation). Quantitative studies describing DBS and levodopa frequently reported no change in social functioning following surgery or in some cases a detrimental change 24–26. It is unclear why social functioning inconsistently improves post-DBS; however, a qualitative study revealed that expectations of surgery outcomes influenced relationships (couple and work) after surgery (see corresponding sections for more details) 27. A psychoeducation class for DBS participants was found to significantly improve postsurgical social adjustment 28. The Stanford Chronic Disease Self-Management Program, which aimed to improve social functioning, did not significantly improve social support scores, however, there were some positive correlations between changes in social support and changes in self-management outcomes after program participation 29.

Another class of PD therapy was behavioral interventions, including a dance class, a support group, and a self-management training program. These interventions had a positive effect on social functioning, by increasing social engagement directly through the activity 29–34. Papers describing quality of life or life changes after PD found that cognitive functioning related to participation 35,36. Additionally, Farhadi et al. found that females reported worse psychosocial functioning and social support 37.

3.4.2. Couple Relationship

The couple relationship has been measured by concordance with partner, dependence on partner, feelings about partner, relationship satisfaction, and sexual adjustment (i.e. frequency and enjoyment of intercourse) 38. Articles discussing this social role focused on the effect of clinical/PD symptoms (n=7), relationship satisfaction (nonsexual) (n=6), sexual satisfaction (n=5), and the effect of treatment (n=5). The quantitative papers that described clinical/PD symptoms affecting the couple relationship reported that facial masking and Hoehn & Yahr stage were correlated to an impaired couple relationship, while speech problems had no significant impact (20,43). Older couples and those who were able to better cope with the disease reported better relationships 39. The qualitative studies revealed positive and negative impacts on the couple relationship. A positive change people living with Parkinson’s and their spouses reported was the affirmation of their commitment to each other after the diagnosis 41,42. Some negative changes reported included shifting relational roles (with more responsibility falling on the care partner changes in sexual intimacy, engaging in fewer activities together, and financial burden 41–45. Ten papers described the impact of PD on non-sexual aspects (e.g. communication, attention, shared activities) of relationship satisfaction. Buhmann et al found that people living with Parkinson’s, especially women, believed these non-sexual aspects of their relationship became more important after PD diagnosis 46. Eleanor Singer compared marriage satisfaction between people living with Parkinson’s and age-matched controls and found no significant difference 47. Three studies found that depression, anxiety, negative social exchanges, and alexithymia were associated with reduced relationship satisfaction 48–50. Mavandadi et al. measured relationship satisfaction from the care partner perspective and found that satisfaction was related to the care partner’s “benefit finding”, or ability to experience positive change when faced with a stressor like PD 50. Karlstedt et al. investigated relationship mutuality, “the positive quality of a relationship”, and found that having a male care partner was associated with higher mutuality score for the people living with Parkinson’s. Care partner mutuality score was associated with the people living with Parkinson’s mutuality score and the people living with Parkinson’s cognitive ability 51. Qualitative papers in this sub-theme reported that uncertainty about the future and role changes that placed a greater burden on the care partner were strongly associated with relationship quality 41,43,52. Five papers described sexual functioning in PD and how it affects the couple relationship. Lower sexual satisfaction was more common among younger-onset people living with Parkinson’s, males, and those with worse motor scores (MDS-UPDRS), fatigue, and rigidity53,54. Papers also reported that sex life satisfaction was significantly associated with marital satisfaction 48,55. Fleming et al. elucidated this issue, listing dramatic increases or decreases in libido, as well as a shift in relationship roles from partner to carer to be the main reasons for sex life dissatisfaction 41. Five papers described how different interventions or therapies impacted the couple relationship. DBS was found to diminish sexual desire and, in some cases, worsen marital satisfaction 26,47,56. Agid et al. provided an explanation for this worsened marital quality following surgery: either people living with Parkinson’s rejected their spouse after they felt “cured” or they were rejected by their spouse who expected them to be able to return to their premorbid level of functioning following surgery 26. Similarly, higher doses of levodopa were associated with more frequent thoughts about breaking up with a partner and with relationship termination 46. However, support group attendance had a positive influence on the relationship by providing a way for couples to have a shared social activity 57.

3.4.3. Family Role

The family role has been defined by feelings about family interactions, the ability to handle family financial needs, the frequency and quality of interactions with family members, interest in a child’s activities and quality of interaction with children 38. Two mixed-methods papers described how treatments/interventions influenced the family relationship 27,31. People living with Parkinson’s who participated in a tango intervention reported improved family role functioning after the classes 31. Schüpbach et al. reported improved family relationships after DBS surgery were more common than strained relationships 27. Another common theme related to the family role was discussing or sharing the disease with family members. Five papers described that communication early in the disease was crucial for facilitating understanding of the disease among family members and reducing its burden 39,41,54,58,59. Fleming et al. provided more information about why communication was a struggle for some people living with Parkinson’s. People living with Parkinson’s reported the need to “protect” their families and did not want their children to “miss out” on anything because of the diagnosis 41. Navarta-Sanchez described how health care providers and family members influenced the way people living with Parkinson’s handled their disease 39. Receiving support from their family helped make people living with Parkinson’s feel more secure and motivated to maintain their treatment regimen 39.

Four papers described family relationship satisfaction in PD. A quantitative study comparing people living with Parkinson’s to age-matched controls found no difference in parental role satisfaction 24. There were three qualitative papers that discussed the importance of family relationships for QoL in people living with Parkinson’s 23,42,60. Additionally, for some people living with Parkinson’s who were unable to work, parenting or family relationships became a higher priority.

3.4.4. Friendship Role

The friendship role has been measured by how frequently contact (e.g. telephone, email, in person) is initiated with friends and the quality of these interactions 38. Most people living with Parkinson’s reported the number of social contacts they had remained stable after diagnosis and following some treatments for PD (e.g. DBS surgery) 4,56,61,62. Rubenstein et al. noted that although the number of visits friends made to people living with Parkinson’s remained the same, people living with Parkinson’s were less likely to initiate social outings with friends 61. Soleimani et al. revealed that people living with Parkinson’s were concerned about losing social connectedness because of their disease (preventing them from leaving the house or increasing their desire to remain isolated to conceal symptoms) 62. Reduced social outings were found to greatly influence QoL as well as functioning in other relationships (e.g. couple, family) 23,63. Fleming et al. (2004) reported a divide in how friendships changed with PD. Some friendships were strengthened while others ended 41. There was no consensus on factors that predicted relationship outcome following diagnosis.

3.4.5. Work Role

The work role has previously been measured by incorporating both paid and unpaid work (e.g. house work). Work role is defined by the duration of work, any changes to employment (e.g. full-time to part-time), respondent’s feelings about the quality of their work, and relationships with co-workers 38. Nineteen papers described the work role and how it was impaired by PD. Three quantitative papers found factors that contributed to leaving the workforce included anxiety, older age, longer disease duration, female sex, cognitive performance, depression, and ability to perform ADL (e.g. dressing, hygiene) 36,64,65. Several papers described that people living with Parkinson’s decreased their work outside of the home and at home. Decreased employment was more evident in the young-onset group, with reasons for leaving the workforce often tied to the inability to meet job demands 42,43,54,56,61,66,67. Habermann (1996) reported that people living with Parkinson’s who remained in the workforce described goal adjustment, e.g., changing their focus from career advancement to maintaining their current position 43. Qualitative studies also revealed that leaving the workforce impacted other social roles and overall QoL due to perceived loss of societal contribution and social contacts from work 23,52,62. Two papers described the impact of DBS and levodopa on work roles. There was no evidence that levodopa led people to rejoin the workforce 24. Professional activity following DBS was more often worsened than improved 27.

3.4.6. Social and Leisure Role

The social and leisure role has been measured by the frequency, duration and quality of social activities (e.g. hobbies, membership in organizations) 38. Four papers described that the types of activities in which people living with Parkinson’s engaged tended to be more solitary and sedentary, such as reading or watching TV 4,24,41,68. Two qualitative papers provided reasons for this shift to more sedentary activities, including people living with Parkinson’s giving up more physically demanding hobbies because of the disease or favoring more solitary activities because of the unpredictability of symptoms and embarrassment about symptoms 41,68. People living with Parkinson’s mentioned that planning ahead was crucial for maintaining social activities and navigating symptom demands 68. Six papers described the impact of treatment/interventions on social activities. Social and leisure role performance was improved for people living with Parkinson’s who participated in activities with other people living with Parkinson’s (e.g. tango class) (73). These classes naturally provided an opportunity for socialization, as well as the ability to meet with people with similar challenges. Two papers evaluated the effect of DBS on social and leisure roles. Boel et al. described no change in membership to organizations following DBS 56. Liddle et al. found that people living with Parkinson’s reported improved leisure performance after DBS 71.

4. Discussion

4.1. Summary of findings

The aim of this review was to describe the effect of PD on social role functioning. Our work integrates research on how PD affects various social roles, including the couple relationship, family, friendship, work, and social/leisure roles. Our analysis uncovered three central findings: (1) PD can affect performance in different social roles or may cause withdrawal from these roles; (2) standard pharmacologic and surgical interventions have little positive effect on social role functioning in PD; and (3) a wide variety of instruments and data collection methods were used in the reviewed studies, demonstrating a pressing need for a more uniform method to evaluate social role functioning in PD. The primary focus of this review was on the patient related factors that are associated with social functioning. However, the patient’s functioning is also dependent on how partners or caregivers cope with the disease of their loved one and the extent to which this influences their own lives. Some studies focusing on this issue have been published, but we considered caregiver outcomes to be beyond the scope of this review 72,73.

4.2. Strengths and limitations

Our systematic review is the first to summarize social functioning in PD, using a mixed-methods approach. We applied Cochrane’s robust methodological procedures during the review process and had more than one reviewer at each stage to reduce bias. We also acknowledge that we could have missed some potentially relevant articles in other databases or the grey literature. However, we do feel that the five databases we have selected provide relevant sources for papers that would be included in our review.

Furthermore, our review only addressed social functioning from the perspective of the person with Parkinson’s disease. Social functioning is important to study in a network sense as well because it is a group concept and an individual concept. However, the focus of our review was to describe the impact of Parkinson’s disease on the person with Parkinson’s disease and therefore we restricted our inclusion criteria to focus on this topic. We feel that another review would better tackle the caregiver side of the equation.

4.3. Implications for research, policy, and practice

Social role performance is a priority for people with chronic diseases and the clinicians who treat them. Hammarlund et al. researched which outcome measures were most important in PD trials from the perspectives of healthcare professionals and people living with Parkinson’s 74. Study participants (people living with Parkinson’s and health care professionals) most frequently ranked aspects related to social involvement (i.e. quality of life, control of disease processes, ability to be on visiting terms, socializing, and participating in society) as the most important outcome. Additionally, the WHO emphasizes participation in social roles and social role performance among people with chronic disease or disability as a crucial method in which to prevent physical and mental health problems 16. Our review demonstrates that social functioning is an expanding area of research in clinical practice. Although some papers were published in more academic research-oriented journals (n=20), there were several papers in neurology journals (n=8), nursing journals (n=7) and rehabilitation journals (n=12), and occupational therapy journals (n=4). Additionally, publications related to social functioning have been increasing in popularity, with most of the papers included in this review published in the last 4 years.

Our review identified several correlates of impaired social role performance in PD, including disease severity, anxiety, depression, and cognitive impairment. However, less attention has been paid to interventions or methods of preserving or improving social role functioning. In fact, standard therapies for the motor symptoms of Parkinson’s disease (DBS and levodopa) have not been shown to reliably improve social functioning and in some cases even worsen social role performance. Therefore, other approaches, such as non-pharmacologic therapies, should be investigated. A few studies found that activities like dancing or support groups improved social role functioning and quality of life 31,32,43,75. Future research should focus on a broader range of interventions to improve social role functioning in PD.

This review provides several targets related to social role functioning, which could be used to develop interventions. Poor general social functioning was associated with drooling, facial masking, communication problems, and cognitive impairment 20,21,30,35,76–80. Impaired couple relationships were related to facial masking, higher Hoehn and Yahr stage, lack of coping responses (i.e. spouse “benefit finding”), and sexual dysfunction 20,39,40. Earlier departure from the workforce was associated with female sex, older age, longer disease duration, anxiety, ADL performance, depression, and cognitive impairment 33,42,54,56,61,66,67. The breadth of factors that contribute to impaired functioning signals a variety of plausible intervention targets. Although some factors are fixed, such as sex, age of onset, disease duration, age, and disease severity, there are many that can be targeted with treatment, including neuropsychiatric symptoms, sexual dysfunction, and motor function. Additionally, fixed factors can serve as markers to identify people living with Parkinson’s at greater risk problems in social role functioning. Certain current interventions and treatments address some of the modifiable factors associated with impaired social functioning. A variety of medications, therapies, and complementary strategies exist to address the neuropsychiatric and motor symptoms in PD. However, research on how these approaches affect social functioning is limited. Additionally, treatments for modifiable symptoms, such as sexual dysfunction, have been less thoroughly explored despite the strong association with QoL in many patients with chronic diseases and the couple relationship in PD 81. One review of managing sexual dysfunction in PD promoted several methods, including discussing sexual function in regular neurologist visits, managing medications with sexual side effects, sexual counseling, and timing medications to improve sexual function 82. Incorporating these methods into regular care could greatly improve the couple relationship and overall QoL for people living with Parkinson’s and their spouses. Additionally, understanding how these treatments affect the couple relationship would be beneficial to people living with Parkinson’s, care partners, and clinicians. Of note, within the couple relationship role dysfunction is not exclusively related to patient variables or patient coping, but also depends on caregiver coping and support. This stresses the importance of involving caregivers in (non-pharmacological) supportive treatments.

Social support is another potential target for interventions to improve social functioning in PD. Previous studies have found that positive affect in PD is increased by the number of social contacts maintained 83. Our summary revealed that some friendships are maintained while others are terminated after people living with Parkinson’s received their diagnosis 41. However, the friendship role did not have specific factors associated with changes. Future research could further explore if clinical factors can predict changes in these roles. Beyond friendships, this review described activities that provided socialization, resulting in an increase in social support for people living with Parkinson’s (e.g. support groups, tango classes). This approach to socialization has been supported in other diseases as well, such as dementia and serious mental illness 84,85. Several other exercise classes have been researched in Parkinson’s disease, including Tai Chi, boxing, aerobic exercise, and Qigong 4,63,86,87. Exercise classes have been shown to improve motor symptoms and QoL; however, direct impact on social functioning requires further investigation. Despite the improvement in health status that social support can provide, many patients view social support utilization as an indicator of functional decline and described actively avoiding the need for social support by adopting behaviors to maintain their independence 29. It is important to consider stigma as a potential barrier to participating in interventions to increase social support.

In addition to informing directions for future interventions to improve social role functioning, this review also revealed the lack of PD-specific social functioning measures available to researchers. The quantitative studies included 24 different questionnaires or activities to assess aspects of social role functioning, however, only 3 questionnaires were used in more than one study: the 39-Item Parkinson’s Disease Questionnaire (n=3), Social Adjustment Scale (n=2), and Golombok Rust Inventory of Marital State (n=2). The 39-Item Parkinson’s Disease Questionnaire is a PD specific questionnaire; however, it does not assess social functioning exclusively and includes only 3 questions that address social function. The Social Adjustment Scale focuses on social roles; however, itis not validated in people living with Parkinson’s 38. Finally, the Golombok Rust Inventory only measures the couple relationship and has not been validated in PD 88. There are some factors that could be specific to social functioning in PD (e.g. embarrassment caused by symptoms leading to isolation) that may not be adequately assessed in general questionnaires. A benefit of conducting this mixed-methods review was that the qualitative studies addressed some questions that arose from the quantitative assessments. For example, several studies of DBS revealed that social functioning in the couple relationship was often worsened following surgery; however, family role functioning was improved. This discrepancy could not be clarified by these questionnaires alone, but qualitative interviews uncovered that expectations from patients and spouses play a role in relationship satisfaction following surgery. In order to better measure social role functioning in PD it would be important to develop assessments that are validated in this population and can capture the nuances of the disease that are not currently ascertained from existing questionnaires. Furthermore, new studies should consider incorporating mixed methods to better understand individual experience with PD.

1. Conclusion

Successful aging involves engagement in social and productive activities 89. Furthermore, reduced social participation is a risk factor for depression, cognitive decline, increased health care costs, and overall mortality. Our review reveals how PD impairs general social functioning and the ability to fulfill specific roles. A number of symptoms associated with reduced social functioning can be targeted in order to improve function and QoL. However, current PD treatments and interventions have not been shown to adequately improve social functioning. Patients’ social participation should be considered as soon as minor losses or changes are detected to prevent isolation and promote successful aging.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

K. Perepezko: Has nothing to disclose

J.T. Hinkle: Receives tuition and stipend support through the Medical Scientist Training

Program at the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine (NIH/NIGMS 5 T32 GM007309).

M. Shepard: Has nothing to disclose.

N. Fischer: Has nothing to disclose.

M.P.G. Broen: Has nothing to disclose.

A.F.G. Leentjens: Receives payment from Elsevier Inc. as Editor-in-Chief of the Journal of Psychosomatic Research. He has received research grants from the Michael J Fox

Foundation and the Stichting Internationaal Parkinson Fonds, as well as royalties from Reed-Elsevier, de Tijdstroom and Van Gorcum publishers.

J. Gallo: Has received research grants from the National Institutes of Health.

G.M. Pontone: Has received research grants from the Michael J Fox Foundation and the National Institutes of Health.

References

- 1.Jankovic J Parkinson’s disease: clinical features and diagnosis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2008;79(4):368–376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schrag A, Jahanshahi M, Quinn N. How does Parkinson’s disease affect quality of life? A comparison with quality of life in the general population. Mov Disord. 2000;15(6):1112–1118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cohen F Lazarus RS(1979). Coping with the stresses of illness. Heal Psychol A Handb. 1979:217–254. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Singer E Social costs of Parkinson’s disease. J Chronic Dis. 1973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bettencourt B, Sheldon K. Social roles as mechanism for psychological need satisfaction within social groups. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2001;81(6):1131. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Holt-Lunstad J, Smith TB, Baker M, Harris T, Stephenson D. Loneliness and Social Isolation as Risk Factors for Mortality. Perspect Psychol Sci. 2015. doi: 10.1177/1745691614568352 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shaw JG, Farid M, Noel-Miller C, et al. Social Isolation and Medicare Spending: Among Older Adults, Objective Isolation Increases Expenditures while Loneliness Does Not. J Aging Health. 2017. doi: 10.1177/0898264317703559 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cornwell EY, Waite LJ. Social disconnectedness, perceived isolation, and health among older adults. J Health Soc Behav. 2009. doi: 10.1177/002214650905000103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cacioppo John, Hawkley Louise and Twisted R Perceived Social Isolation Makes me Sad. Psychol Aging. 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wood-Dauphinee S Assessing quality of life in clinical research: from where have we come and where are we going? J Clin Epidemiol. 1999;52(4):355–363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Deuschl G, Schade-Brittinger C, Krack P, et al. A randomized trial of deep-brain stimulation for Parkinson’s disease. N Engl J Med. 2006;355(9):896–908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Den Oudsten BL, Van Heck GL, De Vries J. Quality of Life and Related Concepts in Parkinson’s Disease: A Systematic Review. Mov Disord. 2007. doi: 10.1002/mds.21567 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dowding CH, Shenton CL, Salek SS. A review of the health-related quality of life and economic impact of Parkinson’s disease. Drugs Aging. 2006. doi: 10.2165/00002512-200623090-00001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Post B, Merkus MP, De Haan RJ, Speelman JD. Prognostic factors for the progression of Parkinson’s disease: A systematic review. Mov Disord. 2007. doi: 10.1002/mds.21537 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Soh S-E, Morris ME, McGinley JL. Determinants of health-related quality of life in Parkinson’s disease: a systematic review. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2011;17(1):1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dube KC and Kumar N- read on this. An international perspective: A report from the WHO Collaborative Project, the international study of schizophrenia- Recovery from Schizophrenia: An International Perspective : a Report from the WHO Collaborative Project, The International Study of Sch. 2007:370. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61415-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.van Uem JMT, Marinus J, Canning C, et al. Health-related quality of life in patients with Parkinson’s disease—a systematic review based on the ICF model. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2016;61:26–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Critical Appraisal Skills Programme. 2018.

- 19.F S, C A, K WG, et al. Palliative care for Parkinson’s disease: Patient and carer’s perspectives explored through qualitative interview. Palliat Med. 2017;31(7 PG-634–641):634–641. doi: 10.1177/0269216316669922 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gunnery SD, Habermann B, Saint-Hilaire M, Thomas CA, Tickle-Degnen L. The Relationship between the Experience of Hypomimia and Social Wellbeing in People with Parkinson’s Disease and their Care Partners. J Parkinsons Dis. 2016;6(3):625–630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Miller N, Noble E, Jones D, Burn D. Life with communication changes in Parkinson’s disease. Age Ageing. 2006. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afj053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wressle E, Engstrand C, Granérus A. Living with Parkinson’s disease: elderly patients’ and relatives’ perspective on daily living. Aust Occup Ther J. 2007;54(2 PG-131–139):131–139. http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=rzh&AN=105743000&site=ehost-live&scope=siteNS −. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dauwerse L, Hendrikx A, Schipper K, Struiksma C, Abma TA. Quality-of-life of patients with Parkinson’s disease. Brain Inj. 2014. doi: 10.3109/02699052.2014.916417 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Singer E The effect of treatment with levodopa on parkinson patients’ social functioning and outlook on life. J Clin Epidemiol. 1974;27(11):581–594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Volkmann J, Albanese A, Kulisevsky J, et al. Long‐term effects of pallidal or subthalamic deep brain stimulation on quality of life in Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord. 2009;24(8):1154–1161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Agid Y, Schüpbach M, Gargiulo M, et al. Neurosurgery in Parkinson’s disease: the doctor is happy, the patient less so? J Neural Transm. 2006. doi: 10.1007/978-3-211-45295-0_61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schüpbach M, Gargiulo M, Welter ML, et al. Neurosurgery in Parkinson disease: A distressed mind in a repaired body? Neurology. 2006. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000234880.51322.16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Santos JFA Dos, Montcel ST Du, Gargiulo M, et al. Tackling psychosocial maladjustment in Parkinson’s disease patients following subthalamic deep-brain stimulation: A randomised clinical trial. PLoS One. 2017. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0174512 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pappa K, Doty T, Taff SD, Kniepmann K, Foster ER. Self-Management Program Participation and Social Support in Parkinson’s Disease: Mixed Methods Evaluation. Phys Occup Ther Geriatr. 2017;35(2):81–98. doi: 10.1080/02703181.2017.1288673 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fox S, Cashell A, Kernohan WG, et al. Palliative care for Parkinson’s disease: Patient and carer’s perspectives explored through qualitative interview. Palliat Med. 2017. doi: 10.1177/0269216316669922 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zafar M, Bozzorg A, Hackney ME. Adapted Tango improves aspects of participation in older adults versus individuals with Parkinson’s disease. Disabil Rehabil. 2017. doi: 10.1080/09638288.2016.1226405 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rocha PA, Slade SC, McClelland J, Morris ME. Dance is more than therapy: Qualitative analysis on therapeutic dancing classes for Parkinson’s. Complement Ther Med. 2017;34:1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Habermann B, Shin JY. Preferences and concerns for care needs in advanced Parkinson’s disease: a qualitative study of couples. J Clin Nurs. 2017;26(11–12):1650–1656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Choudhury TK, Harris C, Crist K, Satterwhite TK, York MK. Comparative Patient Satisfaction and Feasibility of a Pilot Parkinson’s Disease Enrichment Program. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol. 2017. doi: 10.1177/0891988717720299 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Vlagsma TT, Koerts J, Tucha O, et al. Objective Versus Subjective Measures of Executive Functions: Predictors of Participation and Quality of Life in Parkinson Disease? Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2017. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2017.03.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Meligrana L, Sgaramella Maria T, Bartolomei L, et al. The role of cognitive, functional and neuropsychiatric symptoms on community integration in ParkinsonLT<GT>LT<GT>GT<LT>GT<GT>‘s disease. Int J Child Heal Hum Dev. 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Farhadi F, Vosoughi K, Shahidi GA, Delbari A, L�kk J, Fereshtehnejad SM. Sexual dimorphism in Parkinson’s disease: Differences in clinical manifestations, quality of life and psychosocial functioning between males and females. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2017. doi: 10.2147/NDT.S124984 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Weissman M, Bothwell S. Self-report version of the Social Adjustment Scale. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1976;33:1111–1115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Navarta-Sánchez MV, Senosiain GarcÃa JM, Riverol M, et al. Factors influencing psychosocial adjustment and quality of life in parkinson patients and informal caregivers. Qual Life Res An Int J Qual Life Asp Treat Care Rehabil. 2016;(Journal Article PG-). doi: 10.1007/s11136-015-1220-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Greene SM, Griffin WA. Symptom study in context: Effects of marital quality on signs of Parkinson’s disease during patient-spouse interaction. Psychiatry. 1998. doi: 10.1080/00332747.1998.11024817 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fleming V, Tolson D, Schartau E. Changing perceptions of womanhood: Living with Parkinson’s Disease. Int J Nurs Stud. 2004. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2003.12.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hodgson JH, Garcia K, Tyndall L. Parkinson’s disease and the couple relationship: A qualitative analysis. Fam Syst Heal. 2004. doi: 10.1037/1091-7527.22.1.101 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Habermann B Day-to-Day Demands of Parkinson’s Disease. West J Nurs Res. 1996. doi: 10.1177/019394599601800403 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Martin SC. Relational issues within couples coping with Parkinson’s disease: Implications and ideas for family-focused care. J Fam Nurs. 2016;22(2):224–251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.O’Connor E J, McCabe MP, Firth L. The impact of neurological illness on marital relationships. J Sex Marital Ther. 2008;2008/01/29(2 PG-115–132):115–132. doi: 10.1080/00926230701636189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Buhmann C, Dogac S, Vettorazzi E, Hidding U, Gerloff C, Jürgens TP. The impact of Parkinson disease on patients’ sexuality and relationship. J Neural Transm. 2017. doi: 10.1007/s00702-016-1649-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Singer E Premature social aging: The social-psychological consequences of a chronic illness. Soc Sci Med. 1974. doi: 10.1016/0037-7856(74)90020–1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wielinski CL, Varpness SC, Erickson-Davis C, Paraschos AJ, Parashos SA. Sexual and relationship satisfaction among persons with young-onset parkinson’s disease. J Sex Med. 2010. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2009.01408.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ricciardi L, Pomponi M, Demartini B, et al. Emotional awareness, relationship quality, and satisfaction in patients with parkinson’s disease and their spousal caregivers. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2015;203(8):646–649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mavandadi S, Dobkin R, Mamikonyan E, Sayers S, Ten Have T, Weintraub D. Benefit finding and relationship quality in Parkinson’s disease: A pilot dyadic analysis of husbands and wives. J Fam Psychol. 2014. doi: 10.1037/a0037847 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Karlstedt M, Fereshtehnejad S- M, Aarsland D, Lökk J. Determinants of Dyadic Relationship and Its Psychosocial Impact in Patients with Parkinson’s Disease and Their Spouses. Parkinsons Dis. 2017. doi: 10.1155/2017/4697052 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ravenek M, Rudman DL, Jenkins ME, Spaulding S. Understanding uncertainty in young-onset Parkinson disease. Chronic Illn. 2017. doi: 10.1177/1742395317694699 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bronner G, Cohen OS, Yahalom G, et al. Correlates of quality of sexual life in male and female patients with Parkinson disease and their partners. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2014. doi: 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2014.07.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Schrag A, Hovris A, Morley D, Quinn N, Jahanshahi M. Young- versus older-onset Parkinson’s disease: Impact of disease and psychosocial consequences. Mov Disord. 2003. doi: 10.1002/mds.10527 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.O’Connor EJ, McCabe MP, Firth L. The impact of neurological illness on marital relationships. J Sex Marital Ther. 2008. doi: 10.1080/00926230701636189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Boel JA, Odekerken VJJ, Geurtsen GJ, et al. Psychiatric and social outcome after deep brain stimulation for advanced Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord. 2016. doi: 10.1002/mds.26468 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Smith LJ, Shaw RL. Learning to live with Parkinson’s disease in the family unit: an interpretative phenomenological analysis of well-being. Med Heal Care Philos. 2017. doi: 10.1007/s11019-016-9716-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Whetten-Goldstein K, Sloan F, Kulas E, Cutson T, Schenkman M. The burden of Parkinson’s disease on society, family, and the individual. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1997. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1997.tb01512.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kang MY, Ellis-Hill C. How do people live life successfully with Parkinson’s disease? J Clin Nurs. 2015. doi: 10.1111/jocn.12819 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Den Oudsten BL, Lucas-Carrasco R, Green AM, Whoqol-Dis Group T. Perceptions of persons with Parkinson’s disease, family and professionals on quality of life: an international focus group study. Disabil Rehabil. 2011;33(25/26 PG-2490–2508):2490–2508. doi: 10.3109/09638288.2011.575527 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Rubenstein LM, Chrischilles EA, Voelker MD. The impact of Parkinson’s disease on health status, health expenditures, and productivity. Pharmacoeconomics. 1997;12(4):486–498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.S MA, F. B RN, G. R Perceptions of people living with Parkinson’s disease: a qualitative study in Iran. Br J Community Nurs. 2016;21(4 PG-188–95):188–195. doi: 10.12968/bjcn.2016.21.4.188 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Lee KS, Merriman A, Owen A, Chew B, Tan TC. The medical, social, and functional profile of Parkinson’s disease patients. Singapore Med J. 1994. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Timpka J, Svensson J, Nilsson MH, Pålhagen S, Hagell P, Odin P. Workforce unavailability in Parkinson’s disease. Acta Neurol Scand. 2017;135(3):332–338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ray J, Das SK, Gangopadhya PK, Roy T. Quality of life in Parkinson’s disease-Indian scenario. Japi. 2006;54:17–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Wong SL, Gilmour H, Ramage-Morin PL. Parkinson’s disease: Prevalence, diagnosis and impact. Heal Reports. 2014. doi:82-003-X201401114112 [pii] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Valcarenghi RV. The daily lives of people with Parkinson’s disease. Rev Bras Enferm. 2018. doi: 10.1590/0034-7167-2016-0577 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Thordardottir B, Nilsson MH, Iwarsson S, Haak M. “You plan, but you never know” – participation among people with different levels of severity of Parkinson’s disease. Disabil Rehabil. 2014. doi: 10.3109/09638288.2014.898807 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Sabari JS, Ortiz D, Pallatto K, Yagerman J, Glazman S, Bodis-Wollner I. Activity engagement and health quality of life in people with Parkinson’s disease. Disabil Rehabil. 2015;37(16):1411–1415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.S. B AM. D CO, et al. More than just dancing: experiences of people with Parkinson’s disease in a therapeutic dance program. Disabil Rehabil. 2016;(PG-1–6):1–6. doi: 10.1080/09638288.2016.1175037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Liddle J, Phillips J, Gustafsson L, Silburn P. Understanding the lived experiences of Parkinson’s disease and deep brain stimulation (DBS) through occupational changes. Aust Occup Ther J. 2018;65(1):45–53. doi: 10.1111/1440-1630.12437 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Tessitore A, Marano P, Modugno N, et al. Caregiver burden and its related factors in advanced Parkinson’s disease: data from the PREDICT study. J Neurol. 2018:1–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Berger S, Chen T, Eldridge J, Thomas CA, Habermann B, Tickle-Degnen L. The self-management balancing act of spousal care partners in the case of Parkinson’s disease. Disabil Rehabil. 2017:1–9. doi: 10.1080/09638288.2017.1413427 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Hammarlund CS, Nilsson MH, Hagell P. Measuring outcomes in Parkinson’s disease: a multi-perspective concept mapping study. Qual Life Res. 2012;21(3):453–463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Vann-Ward T, Morse JM, Charmaz K. Preserving self: Theorizing the social and psychological processes of living with Parkinson disease. Qual Health Res. 2017;27(7):964–982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Kalf JG, Smit AM, Bloem BR, Zwarts MJ, Munneke M. Impact of drooling in Parkinson’s disease. J Neurol. 2007. doi: 10.1007/s00415-007-0508-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Anderson RJ, Simpson AC, Channon S, Samuel M, Brown RG. Social problem solving, social cognition, and mild cognitive impairment in Parkinson’s disease. Behav Neurosci. 2013;127(2):184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Shin JY, Pohlig RT, Habermann B. Self- Reported Symptoms of Parkinson’s Disease by Sex and Disease Duration. West J Nurs Res. 2016. doi: 10.1177/0193945916670904 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Marr JA. The experience of living with Parkinson’s disease. J Neurosci Nurs. 1991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Shaw ST, Vivekananda-Schmidt P. Challenges to Ethically Managing Parkinson Disease. J Patient Exp. 2017. doi: 10.1177/2374373517706836 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Clayton A, Ramamurthy S. The Impact of Physical Illness on Sexual Dysfunction. In: Sexual Dysfunction. ; 2008. doi: 10.1159/000126625 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Meco G, Rubino A, Caravona N, Valente M. Sexual dysfunction in Parkinson’s disease. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2008;14(6):451–456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Simpson J, Haines K, Lekwuwa G, Wardle J, Crawford T. Social support and psychological outcome in people with Parkinson’s disease: Evidence for a specific pattern of associations. Br J Clin Psychol. 2006. doi: 10.1348/014466506X96490 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Palo-Bengtsson L, Ekman S- L. Social dancing in the care of persons with dementia in a nursing home setting: a phenomenological study. Sch Inq Nurs Pract. 1997;11(2):23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Hackney ME, Earhart GM. Social partnered dance for people with serious and persistent mental illness: a pilot study. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2010;198(1):76–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Bridgewater KJ, Sharpe MH. Trunk muscle training and early Parkinson’s disease. Physiother Theory Pract. 1997;13(2):139–153. [Google Scholar]

- 87.Schmitz‐Hübsch T, Pyfer D, Kielwein K, Fimmers R, Klockgether T, Wüllner U. Qigong exercise for the symptoms of Parkinson’s disease: a randomized, controlled pilot study. Mov Disord. 2006;21(4):543–548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Rust J, Golombok S. The Golombok-Rust Inventory of Sexual Satisfaction (GRISS). Br J Clin Psychol. 1985. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8260.1985.tb01314.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Rowe JW, Kahn RL. Successful aging. Gerontologist. 1997. doi: 10.5054/tq.2010.215250 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.