Abstract

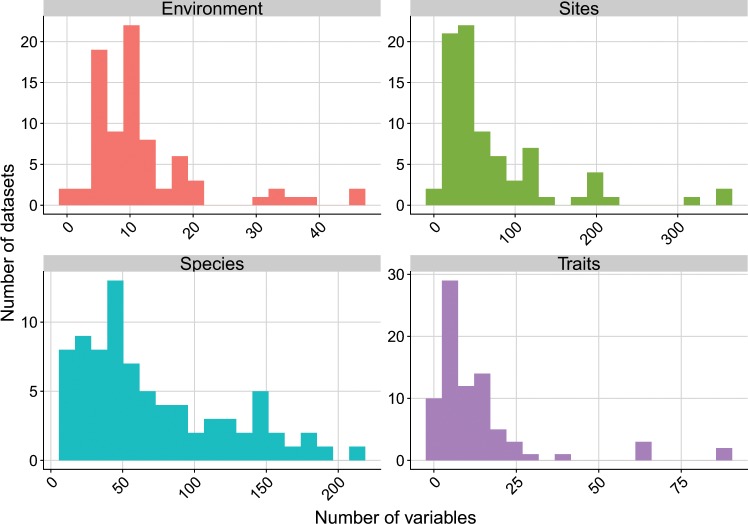

The use of functional information in the form of species traits plays an important role in explaining biodiversity patterns and responses to environmental changes. Although relationships between species composition, their traits, and the environment have been extensively studied on a case-by-case basis, results are variable, and it remains unclear how generalizable these relationships are across ecosystems, taxa and spatial scales. To address this gap, we collated 80 datasets from trait-based studies into a global database for metaCommunity Ecology: Species, Traits, Environment and Space; “CESTES”. Each dataset includes four matrices: species community abundances or presences/absences across multiple sites, species trait information, environmental variables and spatial coordinates of the sampling sites. The CESTES database is a live database: it will be maintained and expanded in the future as new datasets become available. By its harmonized structure, and the diversity of ecosystem types, taxonomic groups, and spatial scales it covers, the CESTES database provides an important opportunity for synthetic trait-based research in community ecology.

Subject terms: Community ecology, Macroecology, Biodiversity

| Measurement(s) | species abundance • species trait • environmental feature • latitude • longitude |

| Technology Type(s) | digital curation |

| Factor Type(s) | year of data collection • type of ecosystem • level of human disturbance |

| Sample Characteristic - Environment | terrestrial natural environment • fresh water • marine biome • anthropogenic terrestrial biome • natural environment • area of mixed forest • cultivated environment |

| Sample Characteristic - Location | Earth (planet) |

Machine-accessible metadata file describing the reported data: 10.6084/m9.figshare.11317790

Background & Summary

A major challenge in ecology is to understand the processes underlying community assembly and biodiversity patterns across space1,2. Over the three last decades, trait-based research, by taking up this challenge, has drawn increasing interest3, in particular with the aim of predicting biodiversity response to environment. In community ecology, it has been equated to the ‘Holy Grail’ that would allow ecologists to approach the potential processes underlying metacommunity patterns4–7. In macroecology, it is common to study biodiversity variation through its taxonomic and functional facets along gradients of environmental drivers8–10. In biodiversity-ecosystem functioning research, trait-based diversity measures complement taxonomic ones to predict ecosystem functions11 offering early-warning signs of ecosystem perturbation12.

The topic of Trait-Environment Relationships (TER) has been extensively studied across the globe and across the tree of life. However, each study deals with a specific system, taxonomic group, and geographic region and uses different methods to assess the relationship between species traits and the environment. As a consequence, we do not know how generalizable apparent relationships are, nor how they vary across ecosystems, realms, and taxonomic groups. In addition, while there is an emerging synthesis about the role of traits for terrestrial plant communities13,14, we know much less about other groups and ecosystem types.

To address these gaps, we introduce the CESTES database - a global database for metaCommunity Ecology: Species, Traits, Environment and Space. This database assembles 80 datasets from studies that analysed empirical multivariate trait-environment relationships between 1996 (the first multivariate study of TER15) and 2018. All considered datasets include four data matrices (Fig. 1): (i) community data (species abundances or presences/absences across multiple sites), (ii) species traits (sensu lato), (iii) environmental variables across sites, and (iv) spatial coordinates. The database is global in extent and covers different taxonomic groups, ecosystem types, levels of human disturbance, and spatial scales (Fig. 2).

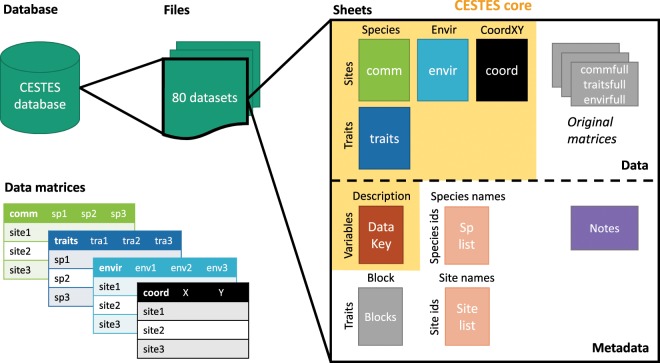

Fig. 1.

Structure of the CESTES database. The database includes 80 Excel files for 80 datasets. Each dataset is composed of four matrices of data stored in spreadsheets: comm (species abundances [n = 68] or presences/absences [n = 12]), traits (species traits), envir (environmental variables), and coord (spatial coordinates). Each dataset also includes a DataKey (description of the entries of the Data tables), a Notes sheet (contact information for the dataset, and, when relevant, processing information), a Species list, and a Site list. The grey components can be the original data matrices, and additional information and do not appear in all the datasets, depending on specific needs (see Methods - Data processing section).

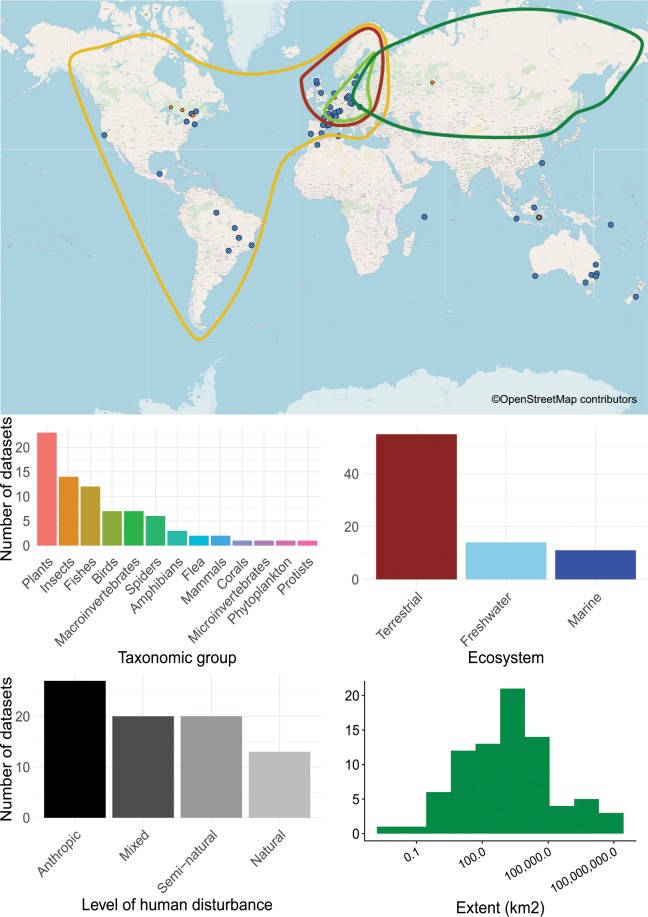

Fig. 2.

Overview of the CESTES database. Upper panel: Map of the 80 dataset locations over the globe (blue spots) (the orange smaller spots represent the 10 ancillary datasets from ceste, the non-spatial supplement of CESTES - see the Methods section); the four coloured polygons represent four datasets that are covering continental extents. The background world map is from OpenStreetMap contributors. Bottom panel: Bar plots and histogram describing the content of the database in terms of: study group, ecological realm, level of human disturbance, and spatial extent of the study.

Several global trait databases already exist or are emerging, such as the Open Traits working group16, the Freshwater Information Platform and its Taxa and Autecology Database for Freshwater Organisms17, the PREDICTS database for Projecting Responses of Ecological Diversity In Changing Terrestrial Systems18,19, and the TRY20 plant trait database for Quantifying and scaling global plant trait diversity. In comparison to these initiatives, the CESTES database has several unique features. Specifically, it maintains the original matching between the community, environmental, and spatial data that go along with the trait information. Keeping this original matching of the data ensures homogeneity in the data structure and allows for targeted analyses of TER. We include all taxonomic groups for which the appropriate matrices are available including groups poorly represented in most trait compilations (e.g., invertebrates and bats). The trait information is particularly diverse, ranging from life-history and morphological to trophic traits, dispersal abilities and tolerances, and covering various ecological mechanisms. CESTES only includes data where georeferenced coordinates, or relative coordinates of the sampling sites (hereafter: spatial coordinates) and environmental variables are available to enable spatial and scaling community analyses. We prioritized studies with abundance or biomass data (as opposed to presence/absence) to facilitate the calculation of a broad range of biodiversity metrics and the study of different facets of biodiversity. The data available in CESTES are open access without restriction, except via citation of this paper (and any original paper that plays a particularly important role in the analyses). Importantly, the CESTES database is meant to be a live database21: it will be maintained in the future and new datasets will be added as they become available.

The CESTES database aims to significantly contribute to research in biogeography, macroecology (including in complement with phylogenies), community and metacommunity ecology, and biodiversity-ecosystem functioning. On the one hand, the quality of its content and structure will allow meta-analyses and syntheses (e.g., the role of taxonomic and functional diversity in spatial patterns of communities). On the other hand, specific datasets will enable the exploration of new questions on a given group, realm, or type of ecosystem.

Methods

Data compilation

Database scoping

The rationale for developing the CESTES database is generally for the study of TER in relation to metacommunity ecology and/or macroecological questions. As such, we focussed on datasets that were appropriate within the metacommunity or macroecology context (i.e. species assemblages distributed across space) and that focussed on traits to understand biodiversity patterns and responses. This prerequisite led us to identify multivariate trait-based studies as the most relevant and rich source of datasets that could fulfil these two requirements.

Given the complexity that still pertains to trait typology13, we did not restrict ourselves to any specific definition of traits and integrated all possible species characteristics if they were used as “traits” in the original study. We thus included ecophysiological, functional, life-history and biological traits, as well as response and effects traits. CESTES users can select traits according to their study needs.

We identified eligible datasets based on two strategies: 1. Literature search, aiming to initiate the database construction along a structured workflow, 2. Networking, aiming to extend the database and open the sharing possibilities, if the datasets fulfilled the CESTES requirements.

The main condition for dataset eligibility was that the TER was the focus of the study and data use. This ensured that: 1. the trait and the taxonomic information were collected from similar biogeographic areas (minimizing mismatches between the geographic origins of trait and taxonomic data), 2. the sampled sites were associated with contextual environmental information that was relevant to the community and traits under study.

Literature search

We searched for multivariate trait-based studies published between 1996 and 2018 via a systematic literature search on the Clarivate Analytics Web of Science Core database. Following Leibold & Chase2, we focussed on studies that included (in any of their contents) the following terms (including spelling variations): “RLQ”15 and “fourth-corner”22,23 because both of them are the predominant methods of multivariate trait-based analyses in ecology24. The “RLQ” refers to a co-inertia analysis that summarizes the overall link between the three matrices of species abundances/presences-absences (L), species traits (Q) and environment (R). The “fourth-corner” refers to a permutation analysis of these three matrices that tests individual trait-environment relationships. The use of RLQ and fourth-corner analyses on the datasets ensures that all of them: 1. are multivariate and include both several species, several traits, and several sites (potentially including spatial information) to align with a metacommunity-like structure, 2. have a comparable structure and can be used in comparative analyses and syntheses.

The search query was:

ALL = (“fourth-corner” OR “fourth corner” OR “fourthcorner” OR “RLQ”)

This search resulted in 368 papers.

Note that the “fourth corner” term more generally and commonly refers to the widely studied question of the links between trait and environment variations22. Most studies that look at TER, regardless of the method of analysis they use, would often acknowledge the historical background of their question by referring in their paper to the “fourth corner problem”. Consequently, by including the “fourth corner” search term, we identified eligible multivariate datasets that were not necessarily analysed by fourth corner analysis/RLQ, but also by e.g. trait-based generalized linear/additive models25,26. However, although this literature search strategy was well suited for identifying sources of multivariate datasets, it could appear as too specific. In order to relax the constraints due to this specificity, we complemented the data search by a networking strategy (see Networking section).

Scanning strategy

Among the 368 studies resulting from the literature search, we scanned through the Introduction and Methods sections. We selected the studies that used at least the three matrices of species abundances, or presences/absences across multiples sites (“comm”), corresponding environment information across sites (“envir”), and species trait information (“traits”). At first, we prioritized datasets that had spatial coordinates of the sampling sites (“coord”) because the spatial aspect is crucial for metacommunity research2. Spatial coordinates, or the relative locations, could sometimes be reconstructed from the maps presented in the publications. Review and opinion papers, medical and simulation studies were not considered. Following this filter, we identified a subset of 105 eligible datasets.

Networking

The network strategy took place in parallel to the data search and relied on both formal and informal communications and exchanges with colleagues through conferences, workshops, group meetings, emails, etc. This allowed us to identify new data providers, or new datasets that we had not found via the earlier literature search. From this networking, we identified an additional set of 34 potentially eligible datasets.

Dataset collection and request

From the total of 139 eligible datasets, 7.2% of the datasets were available on the online supplementary materials of the publication. These were downloaded and formatted for CESTES’ purposes.

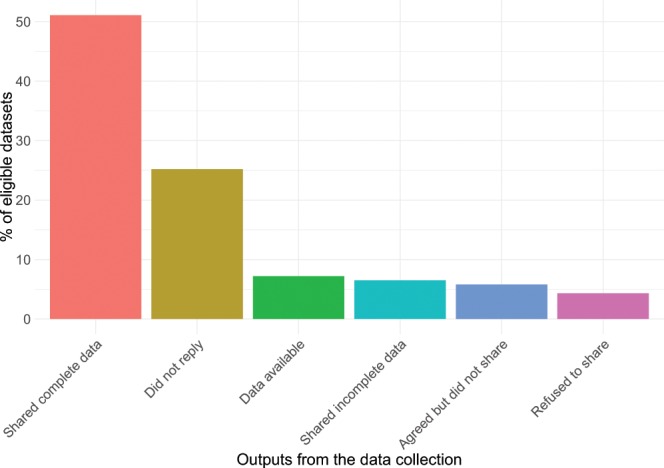

When the datasets were not directly available, we sent a data request via email. In order to launch the CESTES database in a reasonable amount of time, we had to set time limits for the request phase, namely between January and August 2018. As a result, in total 96 authors were contacted, of whom 58% shared their data. In terms of datasets, more than 50% of the eligible datasets were shared and complete (Fig. 3). We also received ‘spontaneous’ datasets that were not part of our initial request, but fulfilled CESTES’ requirements and were thus included in the database. Out of the final complete 80 datasets, 55 were obtained via the literature search, and 25 were obtained from the networking strategy.

Fig. 3.

Success rates of the data search and request. Barplot showing the percentage of the different outputs from the data collection process. Percentages are calculated from a total of 139 datasets identified as eligible for the CESTES database (based on literature search and networking). Incomplete data mainly refer to the datasets that had no spatial coordinates (ceste), included unsolved issues, or provided insufficient metadata information. (“Agreed but did not share” refers to authors who replied positively to the first request but then never sent their data despite reminders because e.g., they did not find time to prepare the data).

Because we received 10 valuable datasets that had no spatial coordinates, we decided to open the ceste subsection of the CESTES database and populate it with these specific datasets. Some of them could be upgraded to CESTES database when the authors are able to provide the coordinates.

Data processing

Dataset checking, cleaning and formatting

We downloaded and received datasets in various formats (.doc, .pdf, .csv, .RData, .txt, .shp, etc.). Following Broman & Woo27, we harmonized and gathered them in Excel files, one file per dataset. This was the most convenient storage format for creating multiple sheets (community, traits, environment, coordinates), handling heterogeneous types of information, and building metadata specific to each dataset. This storage solution also facilitated visual checking and cleaning of the data records.

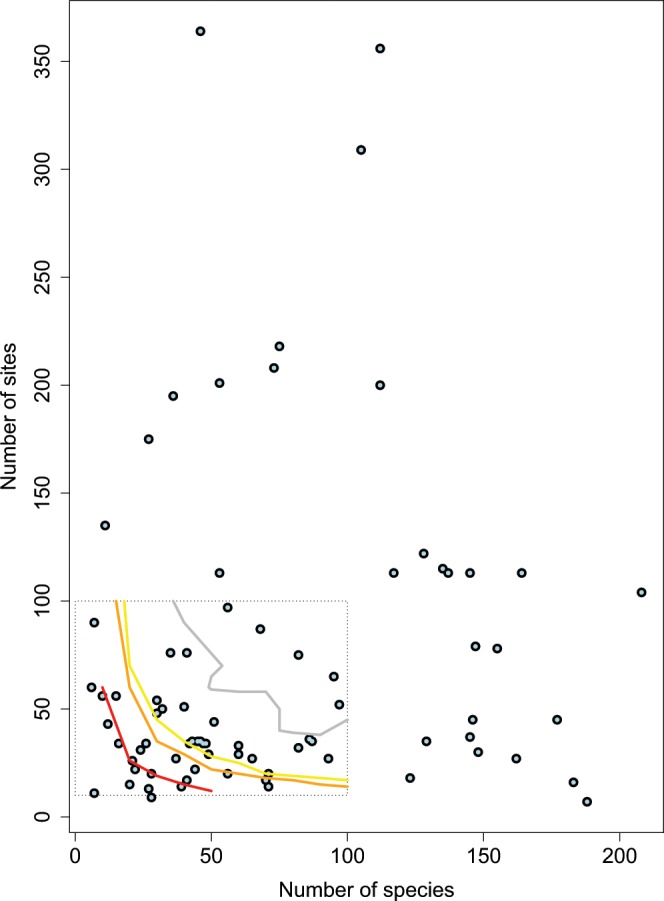

CESTES provides both the processed and the unprocessed (i.e. original) datasets. The processed datasets include “comm”, “traits” and “envir”, i.e. with no empty sites, no “ghost” species (i.e. species that are recorded in none of the sites of the study area), and no NAs (Not Available information) in the matrices. NA removal was based on a compromise in the relative frequency of NAs in the rows and columns of each table; when too many sites compared to the sample size (e.g. >50% of the sites) had NAs for one single variable, this variable was removed, whereas when there were some sites (e.g. <30% of the sites) showing NAs for more than one variable, we removed those sites instead of removing the variables. Since CESTES is primarily designed for trait-based analyses, we removed a trait when it included too many NAs across species (i.e. when the trait value was NA for more than 50% of the species in the community). Similarly, we removed species for which no, or too incomplete trait information was available (i.e. when keeping the species would have implied to lose several traits). This was the case for 29 datasets out of the 80. The number of species removed varied from 1 to 209 species (mean = 27, median = 10, sd = 45) that represented from 1 to 72% of the initial species pool (mean = sd = 17%). (Note that this high maximum value is due to only one single dataset where trait data were exceptionally limiting and implied to remove an important number of species without trait information).

When this overall cleaning procedure implied removing any of the species, traits, or environmental variables, we kept the information of the original unprocessed tables within the Excel file in separate sheets. We named these sheets “commfull”, “traitsfull” and “envirfull”, respectively. Thus, the user can either directly use the processed sheets (“comm”, “traits” and “envir”), or the original ones and apply any other filtering strategies. In doing so, we make sure that CESTES is flexible depending on the users’ goals and needs.

Cleaning steps that altered the original dataset (other than formatting) are reported in the “Notes” sheet so that the user can trace back what has been done over the data processing.

When the data included several temporal horizons (sampling years, or seasons treated as different replicates in the original publication), we split them into different datasets for each time horizon to facilitate further analyses. This explains why several datasets can correspond to one single study area (see Online-only Table 1 attached to this manuscript, and the Data Records section).

Online-only Table 1.

Overview of the CESTES database (name of the dataset, location, ecosystem type, spatial extent, number of sites, species, type of community data…).

| DatasetName | Ecosystem and location | Study id | Taxonomic group | Ecosystem type | Extent (km2) | Level of human disturbance | Sampling date(s)/period | nbEnv | nbTra | nbSpe | nbSit | Example of traits | Example of environmental variables | Type of community data | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bagaria2012 | Mediterranean semi-natural mountain grasslands, southern Catalonia, Spain | 1 | Plants | Terrestrial | 2000 | Semi-natural | 2007 | 8 | 13 | 49 | 29 | Seed size|Dispersal type|Corolla type|Flower/pseudanthium size|Resprouting ability after fire | Mean annual temperature|Mean annual precipitation|Past patch area|Current patch area|% of patch area reduction | number of individuals | Bagaria, G., Pino, J., Rodà, F., & Guardiola, M. (2012). Species traits weakly involved in plant responses to landscape properties in Mediterranean grasslands. Journal of Vegetation Science, 23(3), 432–442. doi:10.1111/j.1654-1103.2011.01363.x |

| Barbaro2009a | Intensive pine plantations, mosaic forest landscapes in south-western France | 2 | Beetles | Terrestrial | 32.16 | Forestry | 2002–2003 | 11 | 12 | 36 | 195 | European trend|European rarity|Regional rarity|Biogeographical position|Daily activity | Clearcut cover/Crop cover|Edge density|Mean patch area|Schrub land cover/ Clearcut cover/Crop cover|Shannon diversity index | number of individuals | Barbaro, L., & van Halder, I. (2009). Linking bird, carabid beetle and butterfly life‐history traits to habitat fragmentation in mosaic landscapes. Ecography, 32(2), 321–333. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0587.2008.05546.x |

| Barbaro2009b | Intensive pine plantations, mosaic forest landscapes in south-western France | 2 | Birds | Terrestrial | 32.16 | Forestry | 2002–2003 | 11 | 12 | 53 | 201 | National trend|Foraging technique|Diet|Nest location|Clutch size | Clearcut cover/Crop cover|Edge density|Mean patch area|Schrub land cover/ Clearcut cover/Crop cover|Shannon diversity index | abundance index | Barbaro, L., & van Halder, I. (2009). Linking bird, carabid beetle and butterfly life‐history traits to habitat fragmentation in mosaic landscapes. Ecography, 32(2), 321–333. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0587.2008.05546.x |

| Barbaro2012 | Fragmented native forests, volcanic banks peninsula, Canterbury, South Island, New Zealand | 3 | Birds | Terrestrial | 625 | Natural | 2010–2011 | 6 | 7 | 21 | 26 | Biogeographic origin|Foraging method|Body mass|Adult diet|Mobility | Plot location|Plot elevation|Patch area size|Forest percentage|Grassland precentage | number of individuals | Barbaro, L., Brockerhoff, E. G., Giffard, B., & van Halder, I. (2012). Edge and area effects on avian assemblages and insectivory in fragmented native forests. Landscape Ecology, 27(10), 1451–1463. doi:10.1007/s10980-012-9800-x |

| Barbaro2017 | Vineyards, Aquitaine, France | 4 | Birds | Terrestrial | 750 | Agricultural | 2013 | 6 | 8 | 56 | 20 | Diet in a breeding season|Foraging guild|Clutch size|Body mass|Nesting site | Grass cover|SNH in 100 meters buffer|SNH in 250 meters buffer|SNH in 500 meters buffer|SNH in 750 meters buffer | number of individuals | Barbaro, L., Rusch, A., Muiruri, E. W., Gravellier, B., Thiery, D., & Castagneyrol, B. (2017). Avian pest control in vineyards is driven by interactions between bird functional diversity and landscape heterogeneity. Journal of Applied Ecology, 54(2), 500–508. doi:10.1111/1365-2664.12740 |

| Bartonova2016 | National Nature Reserves and National Natural Monuments, Czech Republic | 5 | Butterflies | Terrestrial | 78866 | Natural | 2004–2006 | 11 | 13 | 128 | 122 | body size|mobility|density|voltinism|flight period lenght | Relative Perimeter (Perimeter/Area)|Average altitude [m a.s.l.]|range of altitudes [m]|prevailing biotope type|Reserve area [m2] | abundance class | Bartonova, A., Benes, J., Fric, Z. F., Chobot, K., & Konvicka, M. (2016). How universal are reserve design rules? A test using butterflies and their life history traits. Ecography, 39(5), 456–464. doi:10.1111/ecog.01642 |

| Bonada2007S | Mediterranean rivers, Catalonia, Spain | 6 | Macroinvertebrates | Freshwater | 96.3 | Natural | summer 1996 | 16 | 63 | 70 | 17 | Maximal size|Life cycle duration|Potential number of reproduction cycles per year|Aquatic stages|Reproduction | Discharge (l/s)|Temperature (ºC)|Conductivity (microS/cm)|pH|Oxygen (mg/l) | average number of individuals | Bonada, N., Rieradevall, M., & Prat, N. (2007). Macroinvertebrate community structure and biological traits related to flow permanence in a Mediterranean river network. Hydrobiologia, 589(1), 91–106. doi:10.1007/s10750-007-0723-5 |

| Bonada2007W | Mediterranean rivers, Catalonia, Spain | 6 | Macroinvertebrates | Freshwater | 96.3 | Natural | winter 1996 | 14 | 63 | 44 | 22 | Maximal size|Life cycle duration|Potential number of reproduction cycles per year|Aquatic stages|Reproduction | Discharge (l/s)|Temperature (ºC)|Conductivity (microS/cm)|pH|Oxygen (mg/l) | average number of individuals | Bonada, N., Rieradevall, M., & Prat, N. (2007). Macroinvertebrate community structure and biological traits related to flow permanence in a Mediterranean river network. Hydrobiologia, 589(1), 91–106. doi:10.1007/s10750-007-0723-5 |

| BrindAmour2011a | Drouin lake, Laurentian Shield Lakes, Quebec, Canada | 7 | Fishes | Freshwater | 0.31 | Semi-natural | 2001 | 19 | 24 | 7 | 90 | Type of diet|Feeding strata|Body morphology|Migration|Mouth position | Mean littoral slope|Riparian slope|Mean depth|Substrate: Sand|Substrate: Rock | abundance class | Brind’Amour, A., Boisclair, D., Dray, S., & Legendre, P. (2011). Relationships between species feeding traits and environmental conditions in fish communities: a three-matrix approach. Ecological Applications, 21(2), 363–377. doi:10.1890/09-2178.1 |

| BrindAmour2011b | Pare lake, Laurentian Shield Lakes, Quebec, Canada | 7 | Fishes | Freshwater | 0.23 | Semi-natural | 2001 | 17 | 24 | 6 | 60 | Type of diet|Feeding strata|Body morphology|Migration|Mouth position | Mean littoral slope|Riparian slope|Mean depth|Substrate: Sand|Substrate: Rock | abundance class | Brind’Amour, A., Boisclair, D., Dray, S., & Legendre, P. (2011). Relationships between species feeding traits and environmental conditions in fish communities: a three-matrix approach. Ecological Applications, 21(2), 363–377. doi:10.1890/09-2178.1 |

| Campos2018 | Tropical floodplain lakes, Upper Paraná River floodplain, Brazil | 8 | Ostracods | Freshwater | 700 | Mixed | 2011 | 7 | 2 | 37 | 27 | Swimming behavior|Body size | Water temperature|Acidity|Electrical condutivity|Dissolved oxygen|Lake perimeter | density | Campos, R. de, Lansac-Tôha, F. M., Conceição, E. de O. da, Martens, K., & Higuti, J. (2018). Factors affecting the metacommunity structure of periphytic ostracods (Crustacea, Ostracoda): a deconstruction approach based on biological traits. Aquatic Sciences, 80(2), 16. doi:10.1007/s00027-018-0567-2 |

| Carvalho2015 | Tocantins-Araguaia river basin, Amazonia, Brazil | 9 | Stream fishes | Freshwater | 180000 | Mixed | 2008 | 8 | 26 | 65 | 27 | BodyMass_grams|Trophic Guild|Parental Care|Water Column Position|Foragin Method | Altitude (m)|Channel_Depth (m)|Channel_Width (m)|Turbidity (NTU)|Dissolved Oxygen | presence/absence | Carvalho, R. A., & Tejerina-Garro, F. L. (2015). The influence of environmental variables on the functional structure of headwater stream fish assemblages: a study of two tropical basins in Central Brazil. Neotropical Ichthyology, 13(2), 349–360. doi:10.1590/1982-0224-20130148 |

| Castro2010 | Southern Portugal | 10 | Plants | Terrestrial | 1.9844 | Agricultural | NA | 8 | 6 | 28 | 9 | Surface leaf area|Leaf dry matter content|Leaf nitrogen content|Leaf carbon content|Leaf phosphorus content | Soil nitrogen contect|Soil carbon content|Soil phosphorous contect|Organic matter in soil|Soil Carbon | percentage cover | Castro, H., Lehsten, V., Lavorel, S., & Freitas, H. (2010). Functional response traits in relation to land use change in the Montado. Agriculture, Ecosystems & Environment, 137(1–2), 183–191. doi:10.1016/j.agee.2010.02.002 |

| Charbonnier2016a | Forests, Europe | 11 | Bats | Terrestrial | 4400000 | Forestry | 2012–2013 | 5 | 9 | 27 | 175 | Foraging behaviours|Diet type|Nest or roost site location|Migration status|Breeding date | Plot altitude|Forest compositoin|Mean temperature|Mean precipitation|Deciduous cover | number of individuals | Charbonnier, Y. M., Barbaro, L., Barnagaud, J.-Y., Ampoorter, E., Nezan, J., Verheyen, K., & Jactel, H. (2016). Bat and bird diversity along independent gradients of latitude and tree composition in European forests. Oecologia, 182(2), 529–537. doi:10.1007/s00442-016-3671-9 |

| Charbonnier2016b | Forests, Europe | 11 | Birds | Terrestrial | 4400000 | Forestry | 2012–2013 | 5 | 10 | 73 | 208 | Foraging behaviours|Diet type|Nest or roost site location|Migration status|Breeding date | Plot altitude|Forest compositoin|Mean temperature|Mean precipitation|Deciduous cover | number of individuals | Charbonnier, Y. M., Barbaro, L., Barnagaud, J.-Y., Ampoorter, E., Nezan, J., Verheyen, K., & Jactel, H. (2016). Bat and bird diversity along independent gradients of latitude and tree composition in European forests. Oecologia, 182(2), 529–537. doi:10.1007/s00442-016-3671-9 |

| Chmura2016 | Karkonosze Mts, Sudeten Mts, Poland | 12 | Plants | Terrestrial | 135.05 | Natural | NA | 10 | 17 | 46 | 364 | Species Leaf Area (mean value)|Plant height (mean value)|Seed mass|Seed dispersal type|Rosette (leaf arrangement) | Bryophytes cover|Decomposition stage|Length of a log |Area of a log surface|Moisture of a lo | number of individuals | Chmura, D., Żarnowiec, J., & Staniaszek-Kik, M. (2016). Interactions between plant traits and environmental factors within and among montane forest belts: A study of vascular species colonising decaying logs. Forest Ecology and Management, 379, 216–225. doi:10.1016/j.foreco.2016.08.024 |

| Choler2005 | Southwestern Alps, Aravo, Grand Galibier, France | 55 | Plants | Terrestrial | 0.02 | Semi-natural | 2001 | 7 | 8 | 82 | 75 | vegetative height|lateral spread|leaf elevation angle|Specific leaf area|leaf nitrogen | relative south aspects|slope|microtopographic landform index|physical disturbance|zoogenic disturbance | classes of percentage cover | Choler, P. (2005). Consistent Shifts in Alpine Plant Traits along a Mesotopographical Gradient. Arctic, Antarctic, and Alpine Research, 37(4), 444–453. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/4095863 |

| ChongSeng2012a | Seychelles archipelago | 13 | Coral reef fishes | Marine | 3600 | Semi-natural | 2010 | 17 | 2 | 147 | 79 | Fish functional group|Fishing pressure | Acropora coral|Crustose coralline algae|Leathery macroalgae|Non biological particles|Other benthic organisms | number of individuals | Chong-Seng, K. M., Mannering, T. D., Pratchett, M. S., Bellwood, D. R., & Graham, N. A. J. (2012). The Influence of Coral Reef Benthic Condition on Associated Fish Assemblages. PLOS ONE, 7(8), e42167. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0042167 |

| ChongSeng2012b | Seychelles archipelago | 13 | Coral reef fishes | Marine | 3600 | Semi-natural | 2012 | 12 | 2 | 155 | 78 | Fish functional group|Fishing pressure | Acropora coral|Crustose coralline algae|Leathery macroalgae|Non biological particles|Other benthic organisms | number of individuals | Chong-Seng, K. M., Mannering, T. D., Pratchett, M. S., Bellwood, D. R., & Graham, N. A. J. (2012). The Influence of Coral Reef Benthic Condition on Associated Fish Assemblages. PLOS ONE, 7(8), e42167. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0042167 |

| Cleary2007a | Mentaya river, Central Kalimantan province, Borneo, Indonesia | 14 | Birds | Terrestrial | 196 | Mixed | 1997–1998 | 36 | 4 | 145 | 37 | Feeding Guild|Global distribution|Size|Conservation status | Logging|Slope position|Elevation|Short saplings|Tall saplings | log transformed number of individuals | Cleary, Daniel F. R., Boyle, T. J. B., Setyawati, T., Anggraeni, C. D., Loon, E. E. V., & Menken, S. B. J. (2007). Bird species and traits associated with logged and unlogged forest in Borneo. Ecological Applications, 17(4), 1184–1197. doi:10.1890/05-0878 |

| Cleary2007b | Coral reefs, Spermonde Archipelago, Makassar, southwest Sulawesi, Indonesia | 15 | Foraminifera | Marine | 2418 | Mixed | 1997 | 10 | 3 | 24 | 31 | Species form|Symbiont-bearing foraminifera|Skeletal structure | Maximal sea depth|Maximal distance|Exposure to oceanic currents|Sedimentation|Coral formation | number of individuals | Cleary, Daniel F. R., & Renema, W. (2007). Relating species traits of foraminifera to environmental variables in the Spermonde Archipelago, Indonesia. MARINE ECOLOGY PROGRESS SERIES, 334, 73–82. doi:10.3354/meps334073 |

| Cleary2016 | Coral reefs, Jakarta, Indonesia | 16 | Fishes | Marine | 1764 | Fishing | 2005 | 21 | 15 | 162 | 27 | Trophic level?|Life expectancy?|Age maturity? | Water transparency|Temperature|Acidity|Dissolved oxygen|Macroalgae | number of individuals | Cleary, D. F. R., Polónia, A. R. M., Renema, W., Hoeksema, B. W., Rachello-Dolmen, P. G., Moolenbeek, R. G., … de Voogd, N. J. (2016). Variation in the composition of corals, fishes, sponges, echinoderms, ascidians, molluscs, foraminifera and macroalgae across a pronounced in-to-offshore environmental gradient in the Jakarta Bay–Thousand Islands coral reef complex. Marine Pollution Bulletin, 110(2), 701–717. doi:10.1016/j.marpolbul.2016.04.042 |

| Cornwell2009 | Jasper Ridge Biological Preserve, Coastal, California, USA | 17 | Woody plants | Terrestrial | 4.81 | Semi-natural | 2002–2003 | 3 | 3 | 42 | 34 | geometric mean of specific leaf area measurements|arithmetic mean of specific leaf area measurments|number of samples in the species meanpotential diurnal insolation | elevation above sea level|soil water content | percentage cover | Cornwell, W. K., & Ackerly, D. D. (2009). Community Assembly and Shifts in Plant Trait Distributions across an Environmental Gradient in Coastal California. Ecological Monographs, 79(1), 109–126. doi: 10.1890/07-1134.1 |

| Diaz2008 | Segura River basin,SE Spain | 18 | Macroinvertebrates | Freshwater | 6300 | Mixed | 1999–2001 | 39 | 62 | 208 | 104 | Maximal size|Life cycle duration|Potential No. reproductive cycles per year|Aquatic stages|Reproduction | sampling date (month year)|total suspended solids|Ammonium|Nitrite|Nitrate | number of individuals | Mellado-Diaz, A., Luisa Suarez Alonso, M., & Rosario Vidal-Abarca Gutierrez, M. (2008). Biological traits of stream macroinvertebrates from a semi-arid catchment: patterns along complex environmental gradients. FRESHWATER BIOLOGY, 53(1), 1–21. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2427.2007.01854.x |

| Doledec1996 | Urban-rural gradient, Lyon, France | 19 | Birds | Terrestrial | 96 | Mixed | 1981 | 11 | 4 | 40 | 51 | Feeding habit|Feeding stratum|Breeding stratum|Migratory strategy | Presence of farms or villages|Presence of small buildings|Presence of high buildings|Presence of industry|Presence of fields | abundance class | Dolédec, S., Chessel, D., Braak, C. J. F. ter, & Champely, S. (1996). Matching species traits to environmental variables: a new three-table ordination method. Environmental and Ecological Statistics, 3(2), 143–166. doi:10.1007/BF02427859 |

| Drew2017 | Archipelagos, Melanesia | 20 | Coral reef fishes | Marine | 15300000 | Mixed | NA | 1 | 3 | 188 | 7 | Schooling behavior|Maximal body size|Larvae development duration | Reef Area | presence/absence | Drew, J. A., & Amatangelo, K. L. (2017). Community assembly of coral reef fishes along the Melanesian biodiversity gradient. PLoS ONE, 12(10). doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0186123 |

| Dziock2011 | Dessau, Magdeburg, Elbe, Floodplain, Sachsen-Anhalt, Germany | 21 | Grasshopers | Terrestrial | 224 | Agricultural | 2006 | 5 | 6 | 16 | 34 | Dispersal ability|Passive dispersal ability|Ovarioles number|Body size|Oviposition in plant material | Elevation|Distance to the river|Class of litter cover|Vegetation height|Land use and intensity | abundance class | Dziock, F., Gerisch, M., Siegert, M., Hering, I., Scholz, M., & Ernst, R. (2011). Reproducing or dispersing? Using trait based habitat templet models to analyse Orthoptera response to flooding and land use. Agriculture, Ecosystems & Environment, 145(1), 85–94. doi:10.1016/j.agee.2011.07.015 Klaiber, J., Altermatt, F., Birrer, S., Chittaro, Y., Dziock, F., Gonseth, Y., … Bergamini, A. (2017). Fauna Indicativa (Report). Eidg. Forschungsanstalt für Wald, Schnee und Landschaft WSL, CH-Birmensdorf. Retrieved from http://orgprints.org/34497/ |

| Eallonardo2013 | Inland salt/marsh, New York State, USA, near Montezuma; Carncross, Howland Island and Fox Ridge | 54 | Plants | Mixed | 3.5 | Natural | 2007 | 14 | 14 | 41 | 76 | Perennial life span|Rhizomatous growth|Gramonoid growth form|C4 photosynthetic pathway|Succulence | Electrical conductivity|extractible cation concentration|pH|total nitrogen|flooding duration | relative percentage cover | Eallonardo, A. S., Leopold, D. J., Fridley, J. D., & Stella, J. C. (2013). Salinity tolerance and the decoupling of resource axis plant traits. Journal of Vegetation Science, 24(2), 365–374. doi:10.1111/j.1654-1103.2012.01470.x |

| Farneda2015 | Biological Dynamics of Forest Fragments Project (BDFFP) located ca. 80 km north of Manaus, Central Amazon, Brazil | 22 | Bats | Terrestrial | 680 | Natural | 2011–2013 | 9 | 8 | 41 | 17 | trophic_level|habitat_classification|body_mass|dietary_specialization|vertical_stratification | Average number of trees|Average tree diameter|Average vertical stratification|Average number of lianas|Average number of potential roosts | average number of individuals | Farneda, F. Z., Rocha, R., López-Baucells, A., Groenenberg, M., Silva, I., Palmeirim, J. M., … Meyer, C. F. J. (2015). Trait-related responses to habitat fragmentation in Amazonian bats. Journal of Applied Ecology, 52(5), 1381–1391. doi:10.1111/1365-2664.12490 |

| Frenette2012a | Arid steppes, Eastern Morocco | 23 | Plants | Terrestrial | 11765 | Mixed | 2009 | 5 | 18 | 32 | 50 | Leaf Area|Specific Leaf Area|Leaf Dry Matter Content|Leaf Carbon 13 Isotope Content|Leaf Nitrogen 15 Isotope Content | name of the regional site|Grazing|Aridity index |Duration of exclosures|Elevation | number of individuals | Frenette-Dussault, C., Shipley, B., Léger, J.-F., Meziane, D., & Hingrat, Y. (2012). Functional structure of an arid steppe plant community reveals similarities with Grime’s C-S-R theory. Journal of Vegetation Science, 23(2), 208–222. doi:10.1111/j.1654-1103.2011.01350.x |

| Frenette2012b | Arid steppes, Eastern Morocco | 23 | Plants | Terrestrial | 11765 | Mixed | 2010 | 5 | 18 | 32 | 50 | Leaf Area|Specific Leaf Area|Leaf Dry Matter Content|Leaf Carbon 13 Isotope Content|Leaf Nitrogen 15 Isotope Content | name of the regional site|Grazing|Aridity index |Duration of exclosures|Elevation | number of individuals | Frenette-Dussault, C., Shipley, B., Léger, J.-F., Meziane, D., & Hingrat, Y. (2012). Functional structure of an arid steppe plant community reveals similarities with Grime’s C-S-R theory. Journal of Vegetation Science, 23(2), 208–222. doi:10.1111/j.1654-1103.2011.01350.x |

| Frenette2013 | Arid steppes, Eastern Morocco | 23 | Ants | Terrestrial | 11765 | Mixed | 2010 | 5 | 6 | 22 | 22 | Feeding|Period of activity|Recoded period of activity|Color|Functional group | Site region|Grazing|Aridity index|Duration of exclosures|Elevation | number of individuals | Frenette-Dussault, C., Shipley, B., & Hingrat, Y. (2013). Linking plant and insect traits to understand multitrophic community structure in arid steppes. Functional Ecology, 27(3), 786–792. doi:10.1111/1365–2435.12075 |

| Fried2012 | Agriculture areas, France | 24 | Plants | Terrestrial | 386000 | Agricultural | 2003–2006 | 11 | 10 | 75 | 218 | Plant life form|Mode of species dispersal|Plant class|Plant height|Seed weight | Temperature|Preciptiation|Soil pH|Sowing date|Tillage depth | abundance class | Fried, G., Kazakou, E., & Gaba, S. (2012). Trajectories of weed communities explained by traits associated with species’ response to management practices. Agriculture, Ecosystems & Environment, 158, 147–155. doi:10.1016/j.agee.2012.06.005 |

| Gallardo2009 | Ebro river, Mediterranee, Spain | 25 | Macroinvertebrates | Freshwater | 11 | Agricultural | 2006 | 30 | 87 | 35 | 76 | Maximal size|Respiration|Life cycle duration|Potential number of reproduction cycles per year|Reproduction | Type of wetland|position in the watershed|sampling season|emergent vegetation|submerged vegetation | number of individuals | Gallardo, B., Gascon, S., Garcia, M., & Comin, F. A. (2009). Testing the response of macroinvertebrate functional structure and biodiversity to flooding and confinement. Journal of Limnology, 68(2), 315–326. doi: 10.3274/JL09-68-2-14 |

| Gibb2015 | Themeda grasslands, south-east Australia | 26 | Spiders | Terrestrial | 37.64970119 | Mixed | 2009–2011 | 7 | 10 | 86 | 36 | Sex|Body length|Abdomen length|Abdomen width|Cephalothorax widt | Elevation (m)|Temperature (ºC)|Precipitation (mm)|Grass height|Disturbance | number of individuals | Gibb, H., Muscat, D., Binns, M. R., Silvey, C. J., Peters, R. A., Warton, D. I., & Andrew, N. R. (2015). Responses of foliage-living spider assemblage composition and traits to a climatic gradient in Themeda grasslands: Spider Traits and Climatic Gradients. Austral Ecology, 40(3), 225–237. doi:10.1111/aec.12195 |

| Goncalves2010 | Santa Lucia Biological Station (SLBS), Santa Teresa County, Espirito Santo State, southeast Brazil | 27 | Spiders | Terrestrial | 0.44 | Natural | 2006–2007 | 1 | 4 | 146 | 45 | Prosoma height|Prosoma width|Prosoma length|Opistosoma length | Habitat type | number of individuals | Gonçalves-Souza, T., Brescovit, A. D., de C. Rossa-Feres, D., & Romero, G. Q. (2010). Bromeliads as biodiversity amplifiers and habitat segregation of spider communities in a Neotropical rainforest. The Journal of Arachnology, 38(2), 270–279. Retrieved from https://www.jstor.org/stable/20788618 |

| Goncalves2014a | Open restingas, Atlantic rainforest, Brazil | 28 | Spiders | Terrestrial | 220000 | Natural | 2009 | 10 | 22 | 105 | 309 | Guild|Prosoma height|Prosoma width|Prosoma length|Opistosoma length | Plant species|Crown height|Higher crown length|Lower crown length|Leaf length | number of individuals | Gonçalves-Souza, T., Brescovit, A. D., de C. Rossa-Feres, D., & Romero, G. Q. (2010). Bromeliads as biodiversity amplifiers and habitat segregation of spider communities in a Neotropical rainforest. The Journal of Arachnology, 38(2), 270–279. Retrieved from https://www.jstor.org/stable/20788618 |

| Goncalves2014b | Open restingas, Atlantic rainforest, Brazil | 28 | Spiders | Terrestrial | 220000 | Natural | 2010 | 10 | 22 | 112 | 356 | Guild|Prosoma height|Prosoma width|Prosoma length|Opistosoma length | Plant species|Crown height|Higher crown length|Lower crown length|Leaf length | number of individuals | Gonçalves-Souza, T., Romero, G. Q., & Cottenie, K. (2014). Metacommunity versus Biogeography: A Case Study of Two Groups of Neotropical Vegetation-Dwelling Arthropods. PLOS ONE, 9(12), e115137. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0115137 |

| Jamil2013 | Terschelling island, dune meadow, Netherlands | 29 | Plants | Terrestrial | 84 | Agricultural | 1982 | 5 | 5 | 28 | 20 | Specific Leaf Area|Canopy height of a shoot|Lead dry matter content|Seed mass|Life span | A1 horizon thickness|Moisture|Grassland management type|Use|Manure | abundance class | Jamil, T., Ozinga, W. A., Kleyer, M., & ter Braak, C. J. F. (2013). Selecting traits that explain species-environment relationships: a generalized linear mixed model approach. Journal of Vegetation Science, 24(6), 988–1000. doi:10.1111/j.1654-1103.2012.12036.x |

| Jeliazkov2013 | Ponds, agricultural areas, Brie, Seine-et-Marne, France | 30 | Macroinvertebrates | Freshwater | 430 | Agricultural | 2012 | 47 | 91 | 112 | 200 | Body size class|Body size class|Body size class|Body size class|Body size class | Pond habitat and context|Pond area|Agricultural gradient|Urban gradient|Fish or amphibian presence | number of individuals | Jeliazkov, A. (2013). Scale-effects in agriculture-environment-biodiversity relationships (Doctoral thesis). Université Pierre et Marie Curie, Paris, France. Retrieved from http://www.sudoc.fr/180446460 |

| Jeliazkov2014 | Ponds, agricultural areas, Brie, Seine-et-Marne, France | 30 | Amphibians | Freshwater | 430 | Agricultural | 2011–2012 | 9 | 16 | 11 | 135 | Vertical foraging stratum: fossorial|Vertical foraging stratum: terrestrial|Vertical foraging stratum: aquatic|Vertical foraging stratum: arboreal|Diet: Arthropods | Fish presence|Water Quality Index|Pond habitat and context|Proportion of wooded habitat|Pond density | number of individuals | Jeliazkov, A., Chiron, F., Garnier, J., Besnard, A., Silvestre, M., & Jiguet, F. (2014). Level-dependence of the relationships between amphibian biodiversity and environment in pond systems within an intensive agricultural landscape. Hydrobiologia, 723(1), 7–23. doi:10.1007/s10750-013-1503-z |

| Krasnov2015 | Palearctic area; Slovakia | 31 | Flea | Terrestrial | 33000000 | Mixed | 1958, 2008 | 17 | 13 | 177 | 45 | Abundance|Host number|Number of host exploted across region|Number of host exploted across continent|Host number correlaiton | Size of the area|Mean altitude|Minimal altitude|Maximal altitude|NDVI for autumn | presence/absence | Krasnov, B. R., Shenbrot, G. I., Khokhlova, I. S., Stanko, M., Morand, S., & Mouillot, D. (2015). Assembly rules of ectoparasite communities across scales: combining patterns of abiotic factors, host composition, geographic space, phylogeny and traits. Ecography, 38(2), 184–197. doi:10.1111/ecog.00915 |

| Lowe2018a | Urban gradient, Sydney, Australia | 32 | Spiders | Terrestrial | 1000 | Mixed | 2013 | 33 | 7 | 135 | 115 | Guild|Hunting style|Capture lines|Body Size|Period of activity | Land use type|Microhabitat (0–50 cm)|Microhabitat (50–100 cm)|Microhabitat (100–200 cm)|Leaf litter in microhabitat | number of individuals | Lowe, E. C., Threlfall, C. G., Wilder, S. M., & Hochuli, D. F. (2018). Environmental drivers of spider community composition at multiple scales along an urban gradient. Biodiversity and Conservation, 27(4), 829–852. doi:10.1007/s10531-017-1466-x |

| Lowe2018b | Urban gradient, focus on gardens, Sydney, Australia | 32 | Spiders | Terrestrial | 1000 | Mixed | 2013 | 20 | 7 | 95 | 65 | Guild|Hunting style|Capture lines|Body Size|Period of activity | Site region|Stoires number|Adjoining backyards|Distance between the bushes|Distance between fragments | number of individuals | Lowe, E. C., Threlfall, C. G., Wilder, S. M., & Hochuli, D. F. (2018). Environmental drivers of spider community composition at multiple scales along an urban gradient. Biodiversity and Conservation, 27(4), 829–852. doi:10.1007/s10531-017-1466-x |

| Marteinsdottir2014 | Grazed ex-arable fields and semi-natural grasslands, southeast Sweden | 33 | Plants | Terrestrial | 12 | Mixed | 2007–2008 | 7 | 3 | 39 | 14 | Specific leaf area|Leaf drymatter content|Seed mass | pH|Ammonium|Phosphorus|Moisture|Potassium | average percentage cover | Marteinsdóttir, B., & Eriksson, O. (2014). Plant community assembly in semi-natural grasslands and ex-arable fields: a trait-based approach. Journal of Vegetation Science, 25(1), 77–87. doi:10.1111/jvs.12058 |

| Meffert2013 | Urban wasteland, Berlin, Germany | 34 | Birds | Terrestrial | 892 | Urban | 2007 | 4 | 5 | 30 | 54 | Food type|Foraging technique|Adult survival|Innovation rate|Migration strategy | Population within 50 m|Population within 200 m|Sealing within 50 m|Sealing within 2000 m | density | Meffert, P. J., & Dziock, F. (2013). The influence of urbanisation on diversity and trait composition of birds. Landscape Ecology, 28(5), 943–957. doi:10.1007/s10980-013-9867-z |

| Ossola2015 | Urban habitat, south-eastern Melbourne, Australia | 35 | Ants | Terrestrial | 100 | Urban | 2013–2014 | 20 | 5 | 60 | 29 | Head width|Head lendth|Femur length|Pronotum width|Body size index | Habitat type |Understory volume total|Soil cover|Litter cover|Litter mass | number of individuals | Ossola, A., Nash, M. A., Christie, F. J., Hahs, A. K., & Livesley, S. J. (2015). Urban habitat complexity affects species richness but not environmental filtering of morphologically-diverse ants. PeerJ, 3, e1356. doi:10.7717/peerj.1356 |

| Pakeman2011 | Drumbuie, Scotland | 36 | Plants | Terrestrial | 35 | Agricultural | 2007 | 33 | 28 | 148 | 30 | Flowering start, month|Flowering end, month|log(seed mass)|variance in seed dimensions|leafing period, summer green | SoilN|SoilC|Soil_C:N|MoistureLoss|LossOnIgnition | relative abundances | Pakeman, R. J. (2011). Multivariate identification of plant functional response and effect traits in an agricultural landscape. Ecology, 92(6), 1353–1365. doi:10.1890/10-1728.1 |

| Pavoine2011 | Coastal marsh plain Mekhada in the east of Annaba, La Mafragh, Algeria | 37 | Plants | Terrestrial | 100 | Agricultural | 1979 | 8 | 14 | 56 | 97 | Anemogamous|Autogamous|Entomogamous|Annual|Biennial | Clay|Silt|Sand|K2O|Mg2+ | number of individuals | Pavoine, S., Vela, E., Gachet, S., de Bélair, G., & Bonsall, M. B. (2011). Linking patterns in phylogeny, traits, abiotic variables and space: a novel approach to linking environmental filtering and plant community assembly: Multiple data in community organization. Journal of Ecology, 99(1), 165–175. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2745.2010.01743.x |

| Pekin2011 | Walpole and Albany, SW Australia | 38 | Plants | Terrestrial | 1073 | Semi-natural | 2007 | 17 | 4 | 183 | 16 | Life cycle|Regeneration strategy|Root structure|N-fixing ability | Soil type|Fire interval sequence|Fire frequency|Mean annual precip.|Potential evapotrans. | number of individuals | Pekin, B. K., Wittkuhn, R. S., Boer, M. M., Macfarlane, C., & Grierson, P. F. (2011). Plant functional traits along environmental gradients in seasonally dry and fire-prone ecosystem. Journal of Vegetation Science, 22(6), 1009–1020. doi: 10.1111/j.1654-1103.2011.01323.x |

| Pomati2013 | peri-alpine mesotrophic Lake Zürich, Switzerland | 39 | Phytoplankton | Freshwater | 88.66 | Mixed | 2009 | 8 | 15 | 20 | 15 | Phytoplankton morphology|Phytoplankton fluorescence|Length by SWS|Total fluorescence, yellow|Total fluorescence, orange | Water depth|Water temperature|Water conductivity|Oxygen level|Dissolved organic carbon | concentration | Pomati, F., Kraft, N. J. B., Posch, T., Eugster, B., Jokela, J., & Ibelings, B. W. (2013). Individual Cell Based Traits Obtained by Scanning Flow-Cytometry Show Selection by Biotic and Abiotic Environmental Factors during a Phytoplankton Spring Bloom. PLoS ONE, 8(8), e71677. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0071677 |

| Purschke2012a | Semi-natural grasslands, Jordtorp area, Öland Baltic Island, Sweden | 40 | Plants | Terrestrial | 20.25 | Semi-natural | 2007 | 12 | 2 | 164 | 113 | Adult plant longevity|epizoochorous dispersal potential | percentage of grassland habitat in 1994|percentage of grassland habitat in 1938|percentage of grassland habitat in 1835|diversity of the landscape matrix in 1994|diversity of the landscape matrix in 1938 | presence/absence | Purschke, O., Sykes, M. T., Reitalu, T., Poschlod, P., & Prentice, H. C. (2012). Linking landscape history and dispersal traits in grassland plant communities. Oecologia, 168(3), 773–783. doi:10.1007/s00442-011-2142-6 |

| Purschke2012b | Semi-natural grasslands, Jordtorp area, Öland Baltic Island, Sweden | 40 | Plants | Terrestrial | 20.25 | Semi-natural | 2007 | 12 | 1 | 53 | 113 | Endozoochorous dispersal potential | percentage of grassland habitat in 1994|percentage of grassland habitat in 1938|percentage of grassland habitat in 1835|diversity of the landscape matrix in 1994|diversity of the landscape matrix in 1938 | presence/absence | Purschke, O., Sykes, M. T., Reitalu, T., Poschlod, P., & Prentice, H. C. (2012). Linking landscape history and dispersal traits in grassland plant communities. Oecologia, 168(3), 773–783. doi:10.1007/s00442-011-2142-6 |

| Purschke2012c | Semi-natural grasslands, Jordtorp area, Öland Baltic Island, Sweden | 40 | Plants | Terrestrial | 20.25 | Semi-natural | 2007 | 12 | 1 | 145 | 113 | Wind dispersal potential | percentage of grassland habitat in 1994|percentage of grassland habitat in 1938|percentage of grassland habitat in 1835|diversity of the landscape matrix in 1994|diversity of the landscape matrix in 1938 | presence/absence | Purschke, O., Sykes, M. T., Reitalu, T., Poschlod, P., & Prentice, H. C. (2012). Linking landscape history and dispersal traits in grassland plant communities. Oecologia, 168(3), 773–783. doi:10.1007/s00442-011-2142-6 |

| Purschke2012d | Semi-natural grasslands, Jordtorp area, Öland Baltic Island, Sweden | 40 | Plants | Terrestrial | 20.25 | Semi-natural | 2007 | 12 | 1 | 117 | 113 | Seed longevity index | percentage of grassland habitat in 1994|percentage of grassland habitat in 1938|percentage of grassland habitat in 1835|diversity of the landscape matrix in 1994|diversity of the landscape matrix in 1938 | presence/absence | Purschke, O., Sykes, M. T., Reitalu, T., Poschlod, P., & Prentice, H. C. (2012). Linking landscape history and dispersal traits in grassland plant communities. Oecologia, 168(3), 773–783. doi:10.1007/s00442-011-2142-6 |

| Purschke2012e | Semi-natural grasslands, Jordtorp area, Öland Baltic Island, Sweden | 40 | Plants | Terrestrial | 20.25 | Semi-natural | 2007 | 12 | 1 | 137 | 113 | number of seeds per ramet | percentage of grassland habitat in 1994|percentage of grassland habitat in 1938|percentage of grassland habitat in 1835|diversity of the landscape matrix in 1994|diversity of the landscape matrix in 1938 | presence/absence | Purschke, O., Sykes, M. T., Reitalu, T., Poschlod, P., & Prentice, H. C. (2012). Linking landscape history and dispersal traits in grassland plant communities. Oecologia, 168(3), 773–783. doi:10.1007/s00442-011-2142-6 |

| Rachello2007 | Coral reefs, Jakarta, Indonesia | 41 | Corals | Marine | 2242 | Mixed | 1995 | 47 | 5 | 93 | 27 | Shape category|Shape category b|Corallites-calice-valleys categoreis|Corallite size|Colony form | Distance to Jakarta|Distance to mainland|Algal assemblage cover|Coraline algae cover|Turf algae cover | number of colonies | Rachello-Dolmen, P. G., & Cleary, D. F. R. (2007). Relating coral species traits to environmental conditions in the Jakarta Bay/Pulau Seribu reef system, Indonesia. Estuarine, Coastal and Shelf Science, 73(3), 816–826. doi:10.1016/j.ecss.2007.03.017 |

| Raevel2012 | Montpellier district, Mediterranean vertical outcrops | 42 | Plants | Terrestrial | 1886 | Semi-natural | 2008–2009 | 3 | 7 | 97 | 52 | vegetative height|specific leaf area|seed mass|start of flowering|seed dispersal mode | AgeClass|Height|Slope | number of individuals | Raevel, V., Violle, C., & Munoz, F. (2012). Mechanisms of ecological succession: insights from plant functional strategies. Oikos, 121(11), 1761–1770. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0706.2012.20261.x |

| Ribera2001 | Scotland | 43 | Beetles | Terrestrial | 78772 | Mixed | 1995–1997 | 19 | 20 | 68 | 87 | diameter of the eye|length of the antenna|maximum width of the pronotum|maximum depth of the pronotum|maximum width of the elytra | Land use type|Texture|organic content|soil pH|available P | number of individuals | Ribera, I., Dolédec, S., Downie, I. S., & Foster, G. N. (2001). Effect of Land Disturbance and Stress on Species Traits of Ground Beetle Assemblages. Ecology, 82(4), 1112–1129. doi:10.1890/0012-9658(2001)082[1112:EOLDAS]2.0.CO;2 |

| Robinson2014 | Various habitats, protected reserves, Prague region, Czech Republic | 44 | Butterflies | Terrestrial | 260 | Semi-natural | 2003–2004 | 7 | 6 | 71 | 20 | Average wing length|Eggs per batch|Voltinism|Diapause strategy|Diet breadth|Fligth period | Habitat area|Shape complexity|Edge permeability|Area of open habitat|Proportion of open habitat | number of individuals | Robinson, N., Kadlec, T., Bowers, M. D., & Guralnick, R. P. (2014). Integrating species traits and habitat characteristics into models of butterfly diversity in a fragmented ecosystem. Ecological Modelling, 281, 15–25. doi:10.1016/j.ecolmodel.2014.01.022 Kadlec, T., Benes, J., Jarosik, V., & Konvicka, M. (2008). Revisiting urban refuges: Changes of butterfly and burnet fauna in Prague reserves over three decades. Landscape and Urban Planning, 85(1), 1–11. doi:10.1016/j.landurbplan.2007.07.007 Konvicka, M., & Kadlec, T. (2011). How to increase the value of urban areas for butterfly conservation? A lesson from Prague nature reserves and parks. European Journal of Entomology, 108(2), 219–229. doi:10.14411/eje.2011.030 |

| Robroek2017a | Peat bogs, Western Europe | 45 | Vascular plants | Terrestrial | 3800000 | Natural | 2010–2011 | 9 | 5 | 15 | 56 | SLA|Canopy_height|LDMC|Seed_mass|Seed_number | Altitude|Bioclimatic|Mean annual temperature|Seasonality in temperature|Mean annual precipitation | number of individuals | Robroek, B. J. M., Jassey, V. E. J., Payne, R. J., Martí, M., Bragazza, L., Bleeker, A., … Verhoeven, J. T. A. (2017). Taxonomic and functional turnover are decoupled in European peat bogs. Nature Communications, 8(1161). doi:10.1038/s41467-017-01350-5 |

| Robroek2017b | Peat bogs, Western Europe | 45 | Bryophytes | Terrestrial | 3800000 | Natural | 2010–2011 | 9 | 12 | 10 | 56 | SLA|Canopy_height|LDMC|Seed_mass|Seed_number | Altitude|Bioclimatic|Mean annual temperature|Seasonality in temperature|Mean annual precipitation | number of individuals | Robroek, B. J. M., Jassey, V. E. J., Payne, R. J., Martí, M., Bragazza, L., Bleeker, A., … Verhoeven, J. T. A. (2017). Taxonomic and functional turnover are decoupled in European peat bogs. Nature Communications, 8(1161). doi:10.1038/s41467-017-01350-5 |

| Shieh2012 | Wu Stream, central Taiwan | 46 | Macroinvertebrates | Freshwater | 696 | Mixed | 2005–2006 | 11 | 38 | 30 | 48 | Collector-gatherer|Shredder|maximum body size|body flexibility|Temporary attachment | Water temperature|Conductivity|Alkalinity|Sulfate|Elevation | number of individuals | Shieh, S.-H., Wang, L.-K., & Hsiao, W.-F. (2012). Shifts in functional traits of aquatic insects along a subtropical stream in Taiwan. Zoological Studies, 51(7), 1051–1065. |

| Spake2016 | Coniferous plantations, UK | 47 | Beetles | Terrestrial | 95000 | Forestry | 1995–1997 | 9 | 6 | 51 | 44 | Body length|Adult feeding guild|Hind-wing morphology|Activity pattern|Adult habitat affinity | Chronosequence stage|Crop type|Bioclimatic zone|Percentage cover of open semi-natural area|Field, 10 cm – 1.9 m high | number of individuals | Spake, R., Barsoum, N., Newton, A. C., & Doncaster, C. P. (2016). Drivers of the composition and diversity of carabid functional traits in UK coniferous plantations. Forest Ecology and Management, 359, 300–308. doi:10.1016/j.foreco.2015.10.008 |

| Stanko2014 | Slovakia | 48 | Flea | Terrestrial | 12000 | Agricultural | 1986, 1990 | 16 | 6 | 27 | 13 | Abundance|Host number|Continental phylogenetic distinctness|Regional phylogenetic distinctness|Place of living | Mean altitude|Minimal altitude|Maximal altitude|NDVI for autumn|NDVI for spring | number of individuals | Krasnov, B. R., Shenbrot, G. I., Khokhlova, I. S., Stanko, M., Morand, S., & Mouillot, D. (2015). Assembly rules of ectoparasite communities across scales: combining patterns of abiotic factors, host composition, geographic space, phylogeny and traits. Ecography, 38(2), 184–197. doi:10.1111/ecog.00915 |

| Urban2004a | Ponds, 200-ha section of the Yale-Myers Research Station in Union, Connecticut, USA | 49 | Macroinvertebrates | Freshwater | 2 | Mixed | 1999–2000 | 6 | 14 | 71 | 14 | dispersal mode|trophic category | Pond permanence|Loge Area|Max. Depth|Percent Vegetation structure|Percent canopy cover | presence/absence | Urban, M. C. (2004). Disturbance heterogeneity determines freshwater metacommunity structure. Ecology, 85(11), 2971–2978. Retrieved from http://www.esajournals.org/doi/abs/10.1890/03-0631 |

| Urban2004b | Ponds, 200-ha section of the Yale-Myers Research Station in Union, Connecticut, USA | 49 | Amphibians | Freshwater | 2 | Mixed | 1999–2000 | 6 | 2 | 7 | 11 | dispersal mode|trophic category | Pond permanence|Loge Area|Max. Depth|Percent Vegetation structure|Percent canopy cover | presence/absence | Urban, M. C. (2004). Disturbance heterogeneity determines freshwater metacommunity structure. Ecology, 85(11), 2971–2978. Retrieved from http://www.esajournals.org/doi/abs/10.1890/03-0631 |

| vanKlink2017 | Low intensity hay meadows, Swiss Plateau, Switzerland | 50 | Plants | Terrestrial | 12154 | Agricultural | 2014–2015 | 11 | 5 | 129 | 35 | Canopy mean size|Canopy maximal size|Flowering start|Flowering end|Flowering mean | Landscape unit|Treatment|Total annual precipitation|Elevation|Forest | percentage cover | van Klink, R., Boch, S., Buri, P., Rieder, N. S., Humbert, J.-Y., & Arlettaz, R. (2017). No detrimental effects of delayed mowing or uncut grass refuges on plant and bryophyte community structure and phytomass production in low-intensity hay meadows. Basic and Applied Ecology, 20, 1–9. doi:10.1016/j.baae.2017.02.003 |

| vanKlink2018a | Low intensity hay meadows, Swiss Plateau, Switzerland | 50 | Bees | Terrestrial | 12154 | Agricultural | 2014–2015 | 11 | 7 | 46 | 35 | Nesting guild|Larval substrate | Landscape unit|Treatment|Total annual precipitation|Elevation|Forest | Number of individuals | van Klink, R., Menz, M. H. M., Baur, H., Dosch, O., Kühne, I., Lischer, L., … Humbert, J.-Y. (2019). Larval and phenological traits predict invertebrate community response to mowing regime manipulations. Ecological Applications. |

| vanKlink2018b | Low intensity hay meadows, Swiss Plateau, Switzerland | 50 | Moths | Terrestrial | 12154 | Agricultural | 2014–2015 | 11 | 7 | 87 | 35 | Family|Minimal winspan|Maximal wingspan|Larval substrate | Landscape unit|Treatment|Total annual precipitation|Elevation|Forest | Number of individuals | van Klink, R., Menz, M. H. M., Baur, H., Dosch, O., Kühne, I., Lischer, L., … Humbert, J.-Y. (2019). Larval and phenological traits predict invertebrate community response to mowing regime manipulations. Ecological Applications. |

| vanKlink2018c | Low intensity hay meadows, Swiss Plateau, Switzerland | 50 | Ground beetles | Terrestrial | 12154 | Agricultural | 2014–2015 | 11 | 7 | 60 | 33 | Minimal size|Maximal size|Hind wing development|Trophic level|Hibernation | Landscape unit|Treatment|Total annual precipitation|Elevation|Forest | Number of individuals | van Klink, R., Menz, M. H. M., Baur, H., Dosch, O., Kühne, I., Lischer, L., … Humbert, J.-Y. (2019). Larval and phenological traits predict invertebrate community response to mowing regime manipulations. Ecological Applications. |

| vanKlink2018d | Low intensity hay meadows, Swiss Plateau, Switzerland | 50 | Rove beetles | Terrestrial | 12154 | Agricultural | 2014–2015 | 11 | 4 | 82 | 32 | Minimal body length|Maximal body length|Humidity preference | Landscape unit|Treatment|Total annual precipitation|Elevation|Forest | Number of individuals | van Klink, R., Menz, M. H. M., Baur, H., Dosch, O., Kühne, I., Lischer, L., … Humbert, J.-Y. (2019). Larval and phenological traits predict invertebrate community response to mowing regime manipulations. Ecological Applications. |

| vanKlink2018e | Low intensity hay meadows, Swiss Plateau, Switzerland | 50 | Hoverflies | Terrestrial | 12154 | Agricultural | 2014–2015 | 11 | 6 | 26 | 35 | Minimum body size|Maximum body size|Start of adult activitiy|End of activity|Larval substrate | Landscape unit|Treatment|Total annual precipitation|Elevation|Forest | Number of individuals | van Klink, R., Menz, M. H. M., Baur, H., Dosch, O., Kühne, I., Lischer, L., … Humbert, J.-Y. (2019). Larval and phenological traits predict invertebrate community response to mowing regime manipulations. Ecological Applications. |

| Villeger2012a | Estuarine ecosystem,Terminos Lagoon, Gulf of Mexico, Mexico | 51 | Fish | Marine | 3360 | Semi-natural | May-03 | 4 | 16 | 45 | 35 | Mass|Oral gape surface|Oral gape shape|Oral gape position|Gill raker length | Depth|Transparency|Salinity|Dissolved oxygen | biomass | Villéger, S., Miranda, J. R., Hernandez, D. F., & Mouillot, D. (2012). Low Functional β-Diversity Despite High Taxonomic β-Diversity among Tropical Estuarine Fish Communities. PLOS ONE, 7(7), e40679. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0040679 |

| Villeger2012b | Estuarine ecosystem,Terminos Lagoon, Gulf of Mexico, Mexico | 51 | Fish | Marine | 3360 | Semi-natural | Jul-03 | 4 | 16 | 48 | 34 | Mass|Oral gape surface|Oral gape shape|Oral gape position|Gill raker length | Depth|Transparency|Salinity|Dissolved oxygen | biomass | Villéger, S., Miranda, J. R., Hernandez, D. F., & Mouillot, D. (2012). Low Functional β-Diversity Despite High Taxonomic β-Diversity among Tropical Estuarine Fish Communities. PLOS ONE, 7(7), e40679. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0040679 |

| Villeger2012c | Estuarine ecosystem,Terminos Lagoon, Gulf of Mexico, Mexico | 51 | Fish | Marine | 3360 | Semi-natural | Nov-03 | 4 | 16 | 47 | 34 | Mass|Oral gape surface|Oral gape shape|Oral gape position|Gill raker length | Depth|Transparency|Salinity|Dissolved oxygen | biomass | Villéger, S., Miranda, J. R., Hernandez, D. F., & Mouillot, D. (2012). Low Functional β-Diversity Despite High Taxonomic β-Diversity among Tropical Estuarine Fish Communities. PLOS ONE, 7(7), e40679. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0040679 |

| Villeger2012d | Estuarine ecosystem,Terminos Lagoon, Gulf of Mexico, Mexico | 51 | Fish | Marine | 3360 | Semi-natural | May-06 | 4 | 16 | 43 | 35 | Mass|Oral gape surface|Oral gape shape|Oral gape position|Gill raker length | Depth|Transparency|Salinity|Dissolved oxygen | biomass | Villéger, S., Miranda, J. R., Hernandez, D. F., & Mouillot, D. (2012). Low Functional β-Diversity Despite High Taxonomic β-Diversity among Tropical Estuarine Fish Communities. PLOS ONE, 7(7), e40679. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0040679 |

| Villeger2012e | Estuarine ecosystem,Terminos Lagoon, Gulf of Mexico, Mexico | 51 | Fish | Marine | 3360 | Semi-natural | Jul-06 | 4 | 16 | 46 | 35 | Mass|Oral gape surface|Oral gape shape|Oral gape position|Gill raker length | Depth|Transparency|Salinity|Dissolved oxygen | biomass | Villéger, S., Miranda, J. R., Hernandez, D. F., & Mouillot, D. (2012). Low Functional β-Diversity Despite High Taxonomic β-Diversity among Tropical Estuarine Fish Communities. PLOS ONE, 7(7), e40679. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0040679 |

| Westgate2012 | Eucalypt forest, Booderee National Park, Australia | 52 | Amphibians | Terrestrial | 98 | Natural | 2007–2008 | 6 | 2 | 12 | 43 | Ability to climb|Ability to burrow | Hydroperiod|Logarithm of pond width|Logarithm of forest percentage|Logarithm of number of trees|Mean interval of fire return | presence/absence | Westgate, M. J., Driscoll, D. A., & Lindenmayer, D. B. (2012). Can the intermediate disturbance hypothesis and information on species traits predict anuran responses to fire? Oikos, 121(10), 1516–1524. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0706.2011.19863.x |

| Yates2014 | Pasture vs remnant vegetation, North east of New South Wales, Australia | 53 | Ants | Terrestrial | 45500 | Mixed | 2007 | 9 | 11 | 123 | 18 | Minimum inter-eye distance|eye width|head length|mandible length|top tooth length | habitat type|soil carbon-nitrogen ratio|soil p |herb cover|leaf litter cover|bare ground cover|Average ambient daily temperaturelong|lat | number of individuals | Yates, M. L., Andrew, N. R., Binns, M., & Gibb, H. (2014). Morphological traits: predictable responses to macrohabitats across a 300 km scale. PeerJ, 2, e271. doi:10.7717/peerj.271 |

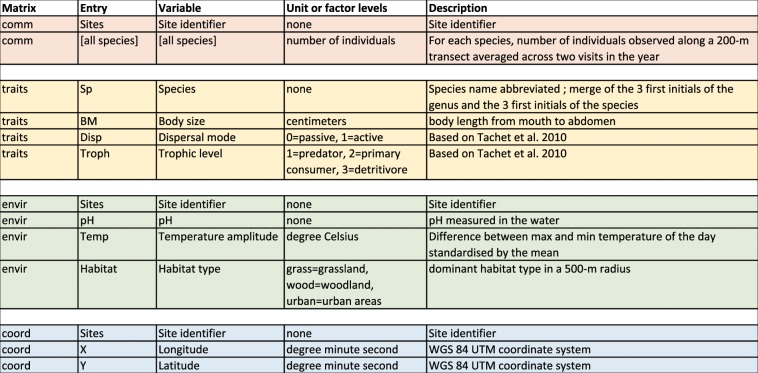

Metadata preparation

All the entries from the four data sheets - “comm”, “trait”, “envir” and “coord” - were listed and described in a “DataKey” sheet to describe the tables’ content (Fig. 4). This required a thorough examination of the original papers to extract the relevant information for every dataset. In several cases, we required additional exchanges with the data owners for clarifications. Any empty cell in the “DataKey” sheet reflects a lack of information. Importantly, this sheet should not substitute for reading of the original paper and we strongly recommend the users to thoroughly examine each paper before using the data (see Online-only Table 2).

Fig. 4.

“DataKey” structure and example of metadata information in CESTES datasets. A description is given when the variable full name is not self-explanatory or when potentially relevant information was available. Possible empty cells are due to lack of information that could not be recovered from the original publication nor from the data owners.

Online-only Table 2.

Original dataset citations.

| DatasetName | Database | References (original studies/original repository) |

|---|---|---|

| Bagaria2012 | CESTES | Bagaria, G., Pino, J., Rodà, F. & Guardiola, M. Species traits weakly involved in plant responses to landscape properties in Mediterranean grasslands. Journal of Vegetation Science 23, 432–442 (2012). |

| Barbaro2009a | CESTES | Barbaro, L. & van Halder, I. Linking bird, carabid beetle and butterfly life‐history traits to habitat fragmentation in mosaic landscapes. Ecography 32, 321–333 (2009). |

| Barbaro2009b | CESTES | Barbaro, L. & van Halder, I. Linking bird, carabid beetle and butterfly life‐history traits to habitat fragmentation in mosaic landscapes. Ecography 32, 321–333 (2009). |

| Barbaro2012 | CESTES | Barbaro, L., Brockerhoff, E. G., Giffard, B. & van Halder, I. Edge and area effects on avian assemblages and insectivory in fragmented native forests. Landscape Ecology 27, 1451–1463 (2012). |

| Barbaro2017 | CESTES | Barbaro, L. et al. Avian pest control in vineyards is driven by interactions between bird functional diversity and landscape heterogeneity. J Appl Ecol 54, 500–508 (2017). |

| Bartonova2016 | CESTES | Bartonova, A., Benes, J., Fric, Z. F., Chobot, K. & Konvicka, M. How universal are reserve design rules? A test using butterflies and their life history traits. Ecography 39, 456–464 (2016). |

| Bonada2007S | CESTES | Bonada, N., Rieradevall, M. & Prat, N. Macroinvertebrate community structure and biological traits related to flow permanence in a Mediterranean river network. Hydrobiologia 589, 91–106 (2007). |

| Bonada2007W | CESTES | Bonada, N., Rieradevall, M. & Prat, N. Macroinvertebrate community structure and biological traits related to flow permanence in a Mediterranean river network. Hydrobiologia 589, 91–106 (2007). |

| BrindAmour2011a | CESTES | Brind’Amour, A., Boisclair, D., Dray, S. & Legendre, P. Relationships between species feeding traits and environmental conditions in fish communities: a three-matrix approach. Ecological Applications 21, 363–377 (2011). |

| BrindAmour2011b | CESTES | Brind’Amour, A., Boisclair, D., Dray, S. & Legendre, P. Relationships between species feeding traits and environmental conditions in fish communities: a three-matrix approach. Ecological Applications 21, 363–377 (2011). |

| Campos2018 | CESTES | Campos, R. de, Lansac-Tôha, F. M., Conceição, E. de O. da, Martens, K. & Higuti, J. Factors affecting the metacommunity structure of periphytic ostracods (Crustacea, Ostracoda): a deconstruction approach based on biological traits. Aquat Sci 80, 16 (2018). |

| Carvalho2015 | CESTES | Carvalho, R. A. & Tejerina-Garro, F. L. The influence of environmental variables on the functional structure of headwater stream fish assemblages: a study of two tropical basins in Central Brazil. Neotropical Ichthyology 13, 349–360 (2015). |

| Castro2010 | CESTES | Castro, H., Lehsten, V., Lavorel, S. & Freitas, H. Functional response traits in relation to land use change in the Montado. Agriculture, Ecosystems & Environment 137, 183–191 (2010). |

| Charbonnier2016a | CESTES | Charbonnier, Y. M. et al. Bat and bird diversity along independent gradients of latitude and tree composition in European forests. Oecologia 182, 529–537 (2016). |

| Charbonnier2016b | CESTES | Charbonnier, Y. M. et al. Bat and bird diversity along independent gradients of latitude and tree composition in European forests. Oecologia 182, 529–537 (2016). |

| Chmura2016 | CESTES | Chmura, D., Żarnowiec, J. & Staniaszek-Kik, M. Interactions between plant traits and environmental factors within and among montane forest belts: A study of vascular species colonising decaying logs. Forest Ecology and Management 379, 216–225 (2016). |

| Choler2005 | CESTES |

Dray, S. & Dufour, A.-B. The ade4 package: implementing the duality diagram for ecologists. Journal of Statistical Software 1–20 (2007). Choler, P. Consistent Shifts in Alpine Plant Traits along a Mesotopographical Gradient. Arctic, Antarctic, and Alpine Research 37, 444–453 (2005). |

| ChongSeng2012a | CESTES | Chong-Seng, K. M., Mannering, T. D., Pratchett, M. S., Bellwood, D. R. & Graham, N. A. J. The Influence of Coral Reef Benthic Condition on Associated Fish Assemblages. PLOS ONE 7, e42167 (2012). |

| ChongSeng2012b | CESTES | Chong-Seng, K. M., Mannering, T. D., Pratchett, M. S., Bellwood, D. R. & Graham, N. A. J. The Influence of Coral Reef Benthic Condition on Associated Fish Assemblages. PLOS ONE 7, e42167 (2012). |

| Cleary2007a | CESTES |

Cleary, D. F. R. et al. Bird species and traits associated with logged and unlogged forest in Borneo. figshare 10.6084/m9.figshare.c.3293726.v1 (2016) Cleary, D. F. R. et al. Bird species and traits associated with logged and unlogged forest in Borneo. Ecological Applications 17, 1184–1197 (2007). |

| Cleary2007b | CESTES | Cleary, D. F. R. & Renema, W. Relating species traits of foraminifera to environmental variables in the Spermonde Archipelago, Indonesia. Marine Ecology Progress Series 334, 73–82 (2007). |

| Cleary2016 | CESTES | Cleary, D. F. R. et al. Variation in the composition of corals, fishes, sponges, echinoderms, ascidians, molluscs, foraminifera and macroalgae across a pronounced in-to-offshore environmental gradient in the Jakarta Bay–Thousand Islands coral reef complex. Marine Pollution Bulletin 110, 701–717 (2016). |

| Cornwell2009 | CESTES | Cornwell, W. K. & Ackerly, D. D. Community assembly and shifts in plant trait distributions across an environmental gradient in coastal California. Ecological Monographs 79, 109–126 (2009). |

| Diaz2008 | CESTES | Mellado-Diaz, A., Luisa Suarez Alonso, M. & Rosario Vidal-Abarca Gutierrez, M. Biological traits of stream macroinvertebrates from a semi-arid catchment: patterns along complex environmental gradients. Freshwater Biology 53, 1–21 (2008). |

| Doledec1996 | CESTES |

Dray, S. & Dufour, A.-B. The ade4 package: implementing the duality diagram for ecologists. Journal of Statistical Software 1–20 (2007). Dolédec, S., Chessel, D., Braak, C. J. F. ter & Champely, S. Matching species traits to environmental variables: a new three-table ordination method. Environ Ecol Stat 3, 143–166 (1996). |

| Drew2017 | CESTES |

Drew, J. A. & Amatangelo, K. L. Community assembly of coral reef fishes along the Melanesian biodiversity gradient. figshare 10.1371/journal.pone.0186123 (2017). Drew, J. A. & Amatangelo, K. L. Community assembly of coral reef fishes along the Melanesian biodiversity gradient. PLOS ONE 12, (2017). |

| Dziock2011 | CESTES |

Dziock, F. et al. Reproducing or dispersing? Using trait based habitat templet models to analyse Orthoptera response to flooding and land use. Agriculture, Ecosystems & Environment 145, 85–94 (2011). Klaiber, J. et al. Fauna Indicativa. (Eidg. Forschungsanstalt für Wald, Schnee und Landschaft WSL, CH-Birmensdorf, 2017). |

| Eallonardo2013 | CESTES | Eallonardo, A. S., Leopold, D. J., Fridley, J. D. & Stella, J. C. Salinity tolerance and the decoupling of resource axis plant traits. Journal of Vegetation Science 24, 365–374 (2013). |

| Farneda2015 | CESTES | Farneda, F. Z. et al. Trait-related responses to habitat fragmentation in Amazonian bats. Journal of Applied Ecology 52, 1381–1391 (2015). |

| Frenette2012a | CESTES | Frenette-Dussault, C., Shipley, B., Léger, J.-F., Meziane, D. & Hingrat, Y. Functional structure of an arid steppe plant community reveals similarities with Grime’s C-S-R theory. Journal of Vegetation Science 23, 208–222 (2012). |

| Frenette2012b | CESTES | Frenette-Dussault, C., Shipley, B., Léger, J.-F., Meziane, D. & Hingrat, Y. Functional structure of an arid steppe plant community reveals similarities with Grime’s C-S-R theory. Journal of Vegetation Science 23, 208–222 (2012). |

| Frenette2013 | CESTES | Frenette-Dussault, C., Shipley, B. & Hingrat, Y. Linking plant and insect traits to understand multitrophic community structure in arid steppes. Functional Ecology 27, 786–792 (2013). |

| Fried2012 | CESTES | Fried, G., Kazakou, E. & Gaba, S. Trajectories of weed communities explained by traits associated with species’ response to management practices. Agriculture, Ecosystems & Environment 158, 147–155 (2012). |

| Gallardo2009 | CESTES | Gallardo, B., Gascon, S., Garcia, M. & Comin, F. A. Testing the response of macroinvertebrate functional structure and biodiversity to flooding and confinement. Journal of limnology 68, 315–326 (2009). |

| Gibb2015 | CESTES | Gibb, H. et al. Responses of foliage-living spider assemblage composition and traits to a climatic gradient in Themeda grasslands: Spider Traits and Climatic Gradients. Austral Ecology 40, 225–237 (2015). |

| Goncalves2010 | CESTES | Gonçalves-Souza, T., Brescovit, A. D., de C. Rossa-Feres, D. & Romero, G. Q. Bromeliads as biodiversity amplifiers and habitat segregation of spider communities in a Neotropical rainforest. The Journal of Arachnology 38, 270–279 (2010). |

| Goncalves2014a | CESTES | Gonçalves-Souza, T., Romero, G. Q. & Cottenie, K. Metacommunity versus Biogeography: A Case Study of Two Groups of Neotropical Vegetation-Dwelling Arthropods. PLOS ONE 9, e115137 (2014). |

| Goncalves2014b | CESTES | Gonçalves-Souza, T., Romero, G. Q. & Cottenie, K. Metacommunity versus Biogeography: A Case Study of Two Groups of Neotropical Vegetation-Dwelling Arthropods. PLOS ONE 9, e115137 (2014). |

| Jamil2013 | CESTES | Jamil, T., Ozinga, W. A., Kleyer, M. & ter Braak, C. J. F. Selecting traits that explain species-environment relationships: a generalized linear mixed model approach. Journal of Vegetation Science 24, 988–1000 (2013). |

| Jeliazkov2013 | CESTES | Jeliazkov, A. Scale-effects in agriculture-environment-biodiversity relationships. (Université Pierre et Marie Curie, 2013). Retrieved from http://www.sudoc.fr/180446460 |

| Jeliazkov2014 | CESTES | Jeliazkov, A. et al. Level-dependence of the relationships between amphibian biodiversity and environment in pond systems within an intensive agricultural landscape. Hydrobiologia 723, 7–23 (2014). |

| Krasnov2015 | CESTES | Krasnov, B. R. et al. Assembly rules of ectoparasite communities across scales: combining patterns of abiotic factors, host composition, geographic space, phylogeny and traits. Ecography 38, 184–197 (2015). |

| Lowe2018a | CESTES | Lowe, E. C., Threlfall, C. G., Wilder, S. M. & Hochuli, D. F. Environmental drivers of spider community composition at multiple scales along an urban gradient. Biodivers Conserv 27, 829–852 (2018). |

| Lowe2018b | CESTES | Lowe, E. C., Threlfall, C. G., Wilder, S. M. & Hochuli, D. F. Environmental drivers of spider community composition at multiple scales along an urban gradient. Biodivers Conserv 27, 829–852 (2018). |

| Marteinsdottir2014 | CESTES | Marteinsdóttir, B. & Eriksson, O. Plant community assembly in semi-natural grasslands and ex-arable fields: a trait-based approach. Journal of Vegetation Science 25, 77–87 (2014). |

| Meffert2013 | CESTES | Meffert, P. J. & Dziock, F. The influence of urbanisation on diversity and trait composition of birds. Landscape Ecology 28, 943–957 (2013). |

| Ossola2015 | CESTES | Ossola, A., Nash, M. A., Christie, F. J., Hahs, A. K. & Livesley, S. J. Urban habitat complexity affects species richness but not environmental filtering of morphologically-diverse ants. PeerJ 3, e1356 (2015). |

| Pakeman2011 | CESTES | Pakeman, R. J. Multivariate identification of plant functional response and effect traits in an agricultural landscape. Ecology 92, 1353–1365 (2011). |

| Pavoine2011 | CESTES |