Abstract

Background:

Family Centered Care (FCC) is an approach to pediatric rehabilitation service delivery endorsing shared decision-making and effective communication with families. There is great need to understand how early intervention (EI) programs implement these processes, how EI caregivers perceive them, and how they relate to EI service use. Therefore, the purpose of this study is to examine 1) parent- and provider-perceptions about EI FCC processes and 2) the association between FCC perceptions and EI service intensity.

Methods:

In this cross-sectional study, parent perceptions of EI FCC were measured using the electronically administered Measures of Processes of Care (MPOC-56 and MPOC-SP; using 7-point scales). Participants included EI parents (n=29) and providers (n=9) from one urban EI program (1/1/18–6/1/18). We linked survey responses with child characteristics and service use ascertained through EI records. We estimated parent-provider MPOC score correlations and the association between EI service intensity (hours/month) and parent MPOC scores using adjusted linear regression accounting for child characteristics.

Results:

Parents [M=4.2, SD=1.1] and providers [M=5.8, SD=1.3] reported low involvement related to general information exchange. Parent and provider sub-scale scores were not correlated except that parent-reported receipt of specific information was inversely associated with provider-reported provision of general information (r=−0.4, p<.05). In adjusted models, parent perceptions related to respectful and supportive (b=1.57, SE=0.56) and enabling (b=1.42, SE=0.67) care were positively associated with EI intensity, whereas specific information exchange and general information exchange were not associated with intensity.

Conclusion:

We found that EI parents and providers reported high levels of investment in the family-centeredness of their EI care, with the exception of information sharing. Greater EI service intensity was associated with higher perception of involvement with some metrics of family-centeredness.

Keywords: child development, early intervention, family-centered care, caregiver perceptions of care

Introduction

Family Centered Care (FCC) is an approach to planning and delivering pediatric rehabilitation services that endorses shared decision-making and continuous, effective communication with families to ensure care is responsive to their needs and priorities (Chiarello, 2017; Constand, MacDermid, Dal Bello-Haas, & Law, 2014; Mroz, Pitonyak, Fogelberg, & Leland, 2015; “Patient- and family-centered care and the pediatrician’s role,” 2012). FCC is considered the “lynchpin” of high-value pediatric service delivery due, in part, to its link with more optimal outcomes (“Family Engagement and School Readiness,” 2013). Given the importance of family engagement, FCC is a federal mandate for services delivered through Part C early intervention (EI), a common source of rehabilitation services for infants and toddlers with developmental delays and disabilities in the United States (“Statute: Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA), as amended in 2004,” 2004). Moreover, promoting family centered care is a key facet of Early Intervention programs globally (Odom SL, 2003).

Previous literature suggests that there is scope to improve family engagement in service delivery for young children with developmental delays and disabilities. A meta-analysis of pediatric rehabilitation literature that included 9 studies from the United States, 20 from Canada, 20 rom Europe, and 1 from South Africa suggests that the majority of caregivers of children with disabilities perceive the quality of information exchange (i.e., parent-provider communication) as consistently low (Cunningham & Rosenbaum, 2014; Gillian King, Law, King, & Rosenbaum, 1998). Similarly, prior studies have shown that less than half of EI-enrolled families complete family assessment to communicate their needs and priorities for collaborative EI care planning (Mary A Khetani et al., 2018), one-third of families report dissatisfaction with the family-centeredness of their child’s EI plan (Ross, Smit, Twardzik, Logan, & McManus, 2018), and more than half report dissatisfaction with parent-provider communication (Ross et al., 2018).

In order to improve family engagement in EI, it is critical to understand how EI programs meet their FCC obligations, particularly care processes and varying service type(s), breadth, and intensity (G King, Williams, & Hahn Goldberg, 2017). Characterizing EI-FCC service delivery can link parent perceptions of FCC processes quality and rehabilitation service use metrics. In a nationally representative sample of EI-enrolled children, parents reported that their EI care fostered partnerships, yet only half reported knowing what to do if their child was receiving suboptimal service breadth or intensity (Hebbeler et al., 2007). Similarly, only two studies to date have examined EI FCC processes, both are nearly two decades old and only included children with motor delays (O’Neil M & Palisano, 2000; O’Neil, Palisano, & Westcott, 2001).

Understanding EI FCC processes and their association with EI service use is particularly urgent. Federal per child appropriations for EI have decreased (Lazara, Danaher, & Detwiler, 2018), resulting in a need to deliver high value EI: service provision with the greatest reach and most optimal outcomes at the lowest cost. While there is evidence that increased EI service intensity is associated with better functional gains in children at EI exit, (B. M. McManus, Richardson, Schenkman, Murphy, & Morrato, 2019) it is unknown whether it might also be associated with family engagement, which is also key in reaching higher value EI.

The purpose of this study was to examine parent- and provider-reported perceptions of EI FCC processes and then to estimate the association between FCC quality perceptions and observed EI service intensity. The findings of this study have important programmatic and policy implications: with a better understanding of FCC service delivery, approaches that improve gaps in EI care quality and incorporate EI service use can be developed.

Methods

Source Population.

This study was conducted within ENRICH EI program, which is housed within a University Center of Excellence for Developmental Disabilities and provides EI services to approximately 125 families annually. Although there is considerable within and between state variability with regard to EI programming (Spiker, Hebbeler, Wagner, Cameto, & McKenna, 2000), characteristics of ENRICH participants, where available for comparison, resemble state and national estimates of characteristics of EI-enrolled children (e.g., condition type, percent of minority children, and child’s sex) (“Child Count data available at the state and national levels, stratified by child’s age and child’s race and ethnicity,” 2005–2018; Hebbeler et al., 2007; M. A. Khetani, Richardson, & McManus, 2017{Hebbeler, 2007 #8091). This study was approved by the XXX (Blinded) Multiple Institutional Review Board.

Study Design.

In this cross-sectional study, we first collected survey data from EI parents about EI FCC, then linked the responses with data from EI service records on child EI service use, clinical, and socio-demographic information.

Study Sample.

Caregivers of children receiving EI services for at least 3 months and who could read English were invited by service providers to participate in the study via an informational flyer. Interested parents could agree to be contacted by the study team and subsequently provided informed consent and HIPAA authorization to allow the study team access to their child’s EI record. Parents then received a link to the online survey via email. In cases where parents or providers completed more than one survey regarding the same child due to multiple providers working with a child (n=6), one caregiver and/or provider survey was selected at random. All program service providers (n=12) had at least 1 year of EI experience and were invited to participate.

Measures.

Children’s EI service use, clinical, and socio-demographic information were ascertained by EI record abstraction from January 1, 2018-June 30, 2018. The EI program’s data manager has previously validated the process for identifying and ascertaining EI record variables, and we have previously published EI outcomes research using this program’s electronic records (M. A. Khetani et al., 2017).

Online Survey

Parent and provider perceptions of FCC were collected via the Measure of Processes of Care (MPOC), parent version (MPOC-56; 56 items) and service provider version (MPOC-SP; 27 items). The parent/caregiver MPOC asks a series of questions related to examples FCC practices in service provision for children with disabilities, each question can be answered on a 7-point scale ranging from to 1: Not at All to 7: To A Very Great Extent. The MPOC is scored with each question relating to one of the following FCC domains: enabling and partnership; providing general information; providing specific information about the child; coordinated and comprehensive care; and respectful and supportive care. The provider version of the MPOC includes interpersonal sensitivity in place of enabling and partnership and coordinated care. The MPOC takes approximately 45 minutes to complete, has been used extensively in research and has excellent psychometric properties (Cunningham & Rosenbaum, 2014).

EI Record Abstraction

EI service intensity.

To calculate service intensity (hours/month), total service hours were divided by months enrolled in EI (age at MPOC completion minus age at EI referral).

Clinical characteristics.

Child’s condition type was categorized as disability versus developmental delay to reflect the two primary diagnostic reasons for EI referral. In XXX (Blinded), children must be 1.5 SD below the mean in at least one developmental area (communication, cognitive, social, emotional, adaptive) to be considered developmentally delayed (“Developmental Disabilities Services (DDS),” 1995). Children were categorized as having a developmental delay in the absence of a diagnosed disability from the XXX (Blinded) Established Condition Database (“Established Condition Database – Early Intervention XXX (Blinded).,”).

Socio-demographic characteristics.

We collected information on child’s sex (male/female) and primary language (English/Spanish). Race and ethnicity was categorized as white, non-Hispanic (WNH), Hispanic, and two or more races, non-Hispanic. Parental education was grouped as less than a Bachelor’s degree, Bachelor’s degree, or graduate degree. Annual family income was categorized as less than $50,000 or $50,000 and greater. We also collected a measure of health insurance type, which we grouped as private or public (includes Medicaid and CHIP). We grouped age at EI referral as 12 months or less, 13–24 months, and greater than 24 months.

Data Analysis.

Social and clinical characteristics of children and families were first summarized using descriptive statistics.

MPOC Data

For the first aim of comparing parent and provider perceptions of EI care quality, mean MPOC sub-scale scores were estimated. Then, association between the five caregiver and four provider sub-scales were estimated using Pearson correlations.

Association Between Parent MPOC Scores and EI Service Use

For the second aim of linking parent perceptions of EI care quality with EI service intensity, we estimated linear regressions for each sub-scale of the parent MPOC with EI service intensity as the dependent variable. All models include a set of three dichotomous covariates: (1) Hispanic ethnicity, (2) primary language English, and (3) public insurance.

Results

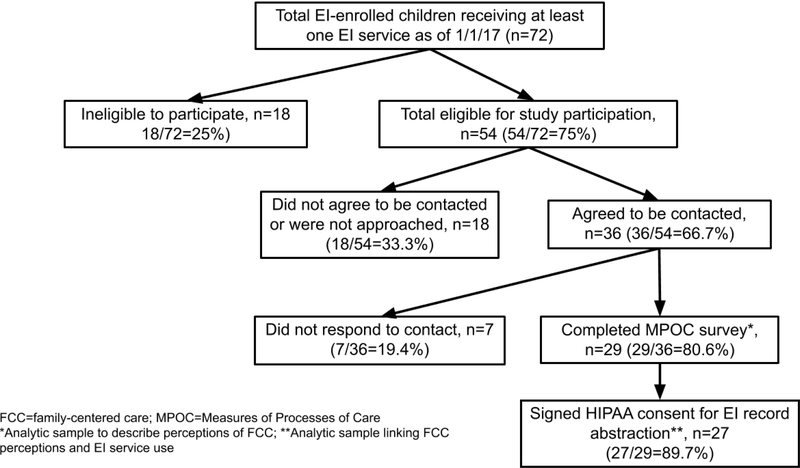

At the time of data collection, 72 families were currently receiving EI services from the study program and, of those, 54 were eligible to participate in the study. In total, 35 surveys were completed for 29 children by caregivers (overall response rate of 29/54=53.7%). See Figure 1 for full details; one child was excluded from analysis due to incomplete information. 31 surveys were completed by 9 EI providers (response rate of 9/12=75%), including three speech therapists, three physical therapists, two occupational therapists, and one developmental interventionist. Caregivers had high levels of formal education, with 56% of mothers and 26% of fathers holding a graduate degree. Two-thirds of the sample had an annual household income over $50,000, and 78% were privately insured. The sample was mostly white (74%) or Hispanic (19%). Nearly 19% of sample children had a developmental disability and 81% had a developmental delay. Mean (SD) service use intensity was 4.0 (2.84) hours per month (Table 1). Compared to using historical study program enrollment information to approximate non-responder demographics(M. A. Khetani et al., 2017), the caregivers participating in this study were more likely to have post high school education (100% versus 50%), income of $≥50,000 (66.7% versus 58.3%), and be white, non-Hispanic (74.1% versus 59.7%).

Figure 1.

CONSORT diagram of participant recruitment and participation

Table 1.

Sample Characteristics (n=27)

| Frequency | Percent | |

|---|---|---|

| Condition Type | ||

| Delay | 22 | 81.48 |

| Disability | 5 | 18.52 |

| Age at Referral | ||

| <=12 months | 14 | 51.85 |

| 13–24 months | 3 | 11.11 |

| >24 months | 7 | 25.93 |

| Unknown | 3 | 11.11 |

| Primary Language | ||

| English | 25 | 92.59 |

| Spanish | 2 | 7.41 |

| Race/Ethnicity | ||

| White | 20 | 74.07 |

| Hispanic | 5 | 18.52 |

| Two or More | 1 | 3.70 |

| Unknown | 1 | 3.70 |

| Insurance | ||

| Private | 21 | 77.78 |

| Public | 3 | 11.11 |

| Unknown | 3 | 11.11 |

| Gender | ||

| Female | 13 | 48.15 |

| Male | 14 | 51.85 |

| Family Income (yearly) | ||

| < 50,000 | 6 | 22.22 |

| ≥ 50,000 | 18 | 66.67 |

| Unknown | 3 | 11.11 |

| Maternal Education Level | ||

| Less than a Bachelor’s Degree | 3 | 11.11 |

| Bachelor’s Degree | 4 | 14.81 |

| Graduate Degree | 15 | 55.56 |

| Unknown | 5 | 18.52 |

| Paternal Education Level | ||

| Less than a Bachelor’s Degree | 6 | 22.22 |

| Bachelor’s Degree | 9 | 33.33 |

| Graduate Degree | 7 | 25.93 |

| Unknown | 5 | 18.52 |

| Mean | SD | |

| Intensity | 4.00 | 2.84 |

Providers gave lower scores on most subscales as compared to caregivers (Table 2). The lowest scoring subscale for both caregivers and providers was providing general information, with a mean (SD) of 5.8 (1.3) for caregivers and 4.2 (1.1) for providers. Respectful and supportive care was the highest scoring domain, with a mean (SD) of 6.8 (0.3) for caregivers, and 6.3 (0.6) for providers, although coordinated care and enabling and partnership was similarly high with 6.7 (0.4) for both subscales among parent reports (Table 2). Parent and provider subscale scores were not correlated except that parent-reported receipt of specific information was inversely associated with provider-reported provision of general information (r=−0.4, p<.05) (Table 3).

Table 2.

Measures of Processes of Care (MPOC) Subscale Means among a sample of EI-enrolled caregivers and service providers.

| Provider MPOC Categories | N | Mean | Std Dev | Min | Median | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Interpersonal Sensitivity | 31 | 5.7 | 0.6 | 3.9 | 5.8 | 6.9 |

| General Information | 31 | 4.2 | 1.1 | 2.2 | 4.2 | 7.0 |

| Specific Information | 31 | 5.4 | 0.8 | 3.3 | 5.3 | 7.0 |

| Respectful & Supportive Care | 31 | 6.3 | 0.6 | 5.1 | 6.2 | 7.0 |

| Parent MPOC Categories | ||||||

| Enabling and Partnership | 28 | 6.7 | 0.4 | 5.9 | 6.9 | 7.0 |

| General Information | 28 | 5.8 | 1.3 | 3.0 | 6.2 | 7.0 |

| Specific Information | 28 | 6.3 | 1.0 | 4.0 | 6.8 | 7.0 |

| Coordinated Care | 28 | 6.7 | 0.4 | 5.4 | 6.9 | 7.0 |

| Respectful & Supportive Care | 28 | 6.8 | 0.3 | 5.9 | 7.0 | 7.0 |

Table 3.

Correlation Between Parent and Provider MPOC Scores

| Provider MPOC Categories | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Interpersonal Sensitivity |

General Information |

Specific Information |

Respectful Care |

|

| Parent MPOC Categories | ||||

| Enabling and Partnership | −0.039 | −0.273 | 0.038 | −0.031 |

| General Information | −0.334 | −0.178 | −0.069 | 0.186 |

| Specific Information | −0.385 | −0.404* | 0.117 | 0.005 |

| Coordinated Care | 0.067 | −0.140 | 0.091 | −0.027 |

| Respectful & Supportive Care | 0.120 | −0.130 | 0.077 | −0.135 |

p<0.001,

p<0.01,

p<0.05

In the adjusted models, parent MPOC scores related to respectful and supportive care (b=1.57, SE=0.56) and enabling and partnership (b=1.42, SE=0.67) were positively associated with EI intensity. Moreover, both of the information exchange scales were smallest in magnitude and non-significant (Table 4).

Table 4.

Adjusted Associations Between Each Parent MPOC Domain Score and Child EI Intensity as β (SD)

| Enabling & Partnership |

General Information |

Specific Information |

Coordinated Care |

Respectful Care |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parent MPOC Categories | |||||

| Enabling and Partnership | 1.4243* | - | - | - | - |

| (0.6702) | |||||

| General Information | - | 0.3682 | - | - | - |

| (0.2103) | |||||

| Specific Information | - | - | 0.1437 | - | - |

| (0.1811) | |||||

| Coordinated Care | - | - | 0.8659 | - | |

| (0.4479) | |||||

| Respectful Care | - | - | - | - | 1.5676* |

| (0.5554) | |||||

| Characteristic Variables | |||||

| Hispanic | 0.1931 | 0.1132 | 0.1611 | 0.5260 | 0.4313 |

| (0.4532) | (0.5360) | (0.5565) | (0.6128) | (0.5358) | |

| Primary English | 1.5309 | 1.6401 | 1.5917 | 2.1785 | 1.8649 |

| (0.9408) | (0.9167) | (1.1223) | (1.1914) | (1.1129) | |

| Public Insurance | 0.2140 | 0.2832 | 0.3582 | 0.5154 | 0.3830 |

| (1.0375) | (0.8742) | (1.0841) | (1.0507) | (1.0626) | |

| Number of Observations | 24 | 24 | 24 | 24 | 24 |

p<0.05

Discussion

In this cross-sectional study, we found that EI parents and providers reported high provider investment in FCC, with the exception of information sharing. Moreover, greater EI service use intensity was associated with perceptions of better FCC quality in some areas. This advances our understanding of the strengths and opportunities to improve family engagement, a key component of value-based EI.

The first main finding of the study is that sample EI parents and providers both reported high perception of involvement in FCC constructs in EI care. EI caregivers, on average, reported enabling and partnership, specific information, respectful care, and coordinated care “to a great extent.” We found higher rates of these FCC processes in our study sample than described in a recent meta-analysis of studies examining outpatient rehabilitation services for school-aged children (N. A. Almasri, An, & Palisano, 2018). Another study (O’Neil et al., 2001) among EI-enrolled children with motor delays examined the role of parenting stress on parent FCC perceptions and found that caregivers reported that care fostered partnerships, provided specific information, and was respectful “to a great extent.” In comparison, our study findings extend previous knowledge about the full battery of FCC processes among an EI-enrolled sample with a variety of developmental conditions.

Our findings suggest opportunities for EI care quality improvement. Specifically, caregivers reported receiving general information only to a “moderate extent” and significantly less often than other FCC constructs. This finding is consistent with prior research (N. Almasri et al., 2012). Similarly, we found that EI providers, on average, reported providing interpersonal sensitivity, respectful care, and specific information “to a fairly great extent”, yet provided general information only to a “moderate extent.” While these findings are similar to previously published studies that have used the MPOC-SP (N. A. Almasri et al., 2018; O’Neil M & Palisano, 2000; O’Neil et al., 2001; Raghavendra, Murchland, Bentley, Wake-Dyster, & Lyons, 2007), to our knowledge this is the first study to measure all MPOC-SP subscales among EI service providers and to subsequently suggest bolstering general information sharing as an area of quality improvement.

Our findings have important clinical and programmatic implications related to bolstering general information exchange during EI care. General information pertains to strengthening parents’ knowledge about opportunities for family-to-family connections (e.g., websites, support groups, library groups); resources to assist with coping with the impact of their child’s diagnosis; opportunities for the whole family, including siblings, to obtain information; and external services (e.g., financial services and respite care). This area of quality improvement is particularly important in light of previous research suggesting that while parents cite access to information and resources as a top priority, caregivers prioritize provision of information specific to the child’s condition (Bamm & Rosenbaum, 2008).

Indeed, the second major finding of this study is that parent and service provider responses were not correlated with the exception of a significant inverse association between caregiver reported specific information and service provider reported general information. This suggests that higher receipt of information about the child’s condition was related to lower provision of general information from providers. This finding is consistent with differing parent and provider service delivery priorities and suggests that parents receive condition-specific information at the cost of provider capacity to provide general information. Factors related to low provision of general information may include provider discipline (Raghavendra et al., 2007) and relying more heavily on child characteristics than on family considerations in clinical decision-making (O’Neil M & Palisano, 2000). Study findings highlight an EI practice gap whereby family needs and priorities are not being appropriately solicited and addressed. Further research should investigate the effect of family interventions that foster meaningful, general information exchange on EI service use, parental satisfaction with care processes, and children’s functional outcomes.

The final major study finding is that greater service intensity was associated with parents perceiving more respectful care that fostered partnerships, yet was not associated with perceptions of specific or general information. On the one hand, greater service intensity could afford families and providers more opportunities for developing a trusting relationship and offering care and support. On the other hand, greater service intensity may contribute to fragmented care or disparate recommendations if more than one provider is involved. In this study, only about ¼ of study children had more than one EI service provider and greater service intensity was not associated with parent perceptions about coordinated care or general or specific information exchange, however, it was associated with clinically meaningful gains (i.e., 1 SD) in overall FCC perceptions, and respectful and supportive care. There is no agreed-upon recommendation for EI service use intensity, indeed, EI differs from a traditional medical model and employs primary coaching and parent education, both of which contribute to lower service intensity. However, previous literature suggests that current EI programming falls short of pediatric rehabilitation service delivery recommendations (Bailes, Reder, & Burch, 2008). In this sample, families were receiving, on average, only one hour of EI services per week. Further research is needed to better understand the role of service delivery type, breadth, and intensity on improving key child and family outcomes over time.

We acknowledge the study’s limitations. This was a cross-sectional study and therefore our results are associations and causal relationships between service use and parent perceptions of care quality cannot be inferred. This study recruited a small sample from a single EI program in Metro XXX (Blinded) and the sample included well-educated caregivers and non-poor families, which may limit the generalizability of our findings in more diverse EI populations. Future research should characterize FCC among larger population-based cohorts. Additionally, study participants were more likely to be educated and higher income than non-respondents (estimated by examining a historical program cohort), which could bias our study findings. Caregiver and provider responses may be less favorable in more socio-economically diverse samples, yet the role of more intensive service use on outcomes may be larger among low-income families (B. McManus, Richardson, Schenkman, & ... 2019). Additionally, we acknowledge the potential role of omitted variable bias as factors such as motivation and maternal well-being or parental stress, which has been shown to explain a small but significant amount of parental care perception variability (O’Neil et al., 2001). We chose not to include these to reduce response burden, but future research should explore salient EI child and family outcomes measures as well as the role of different packages of EI service delivery on EI service use and meaningful child and family outcomes.

Despite these limitations, this study has a number of strengths. To our knowledge, this is the first study to use all sub-scales of the parent and provider versions of the MPOC within an EI sample and highlight opportunities for care quality improvement relative to meaningful information exchange. Second, this was the first published study to examine the association between service use and parental perceptions of rehabilitation care processes. The results of this study have important implications for addressing the key knowledge gaps related to optimal EI service intensity; that is, an additional hour per month of EI services was associated with clinically meaningful gains in parent-reported FCC.

In this era of increased need for value-based care, it is essential to understand how EI service delivery addresses parent preferences and needs and related quality improvement gaps. Our findings suggest that parents and providers perceive that exchange of general information occurs sub-optimally. Further research should explore best-practice interventions to promote parent-provider communication and information sharing.

Key Messages.

Caregivers of children receiving early intervention services perceive that providers do not share information and resources about general child health and development topics often enough.

Increasing receipt of information about the child’s condition was related to decreasing provision of general information from providers, suggesting family needs and priorities are not always being solicited and addressed and that provider and caregivers intervention goals might not be well-aligned.

Greater service intensity appears to be linked with most areas of family centered care except information exchange.

Further research should explore best-practice interventions to promote parent-provider communication and information sharing.

Acknowledgements

BMM and MAK acknowledge funding from the Comprehensive Opportunities in Rehabilitation Research Training program (K12 HD05593). This funding source had no involvement in study design; in the collection, analysis and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; and in the decision to submit the article for publication.

Contributor Information

Beth M. McManus, Department of Health Systems, Management and Policy, Colorado School of Public Health,.

Natalie Murphy, Physical Therapy Program, University of Colorado School of Medicine.

Zachary Richardson, Data Science to Patient Value (D2V), University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus.

Mary A. Khetani, Department of Occupational Therapy, University of Illinois at Chicago.

Margaret Schenkman, Physical Therapy Program, University of Colorado School of Medicine.

Elaine H. Morrato, Department of Health Systems, Management and Policy, Colorado School of Public Health.

References

- Almasri N, Palisano RJ, Dunst C, Chiarello LA, O’Neil ME, & Polansky M (2012). Profiles of family needs of children and youth with cerebral palsy. Child: Care, Health and Development, 38(6), 798–806. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2214.2011.01331.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Almasri NA, An M, & Palisano RJ (2018). Parents’ perception of receiving family-centered care for their children with physical disabilities: a meta-analysis. Physical & Occupational Therapy in Pediatrics, 38(4), 427–443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailes AF, Reder R, & Burch C (2008). Development of guidelines for determining frequency of therapy services in a pediatric medical setting. Pediatric Physical Therapy, 20(2), 194–198. doi: 10.1097/PEP.0b013e3181728a7b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bamm EL, & Rosenbaum P (2008). Family-centered theory: origins, development, barriers, and supports to implementation in rehabilitation medicine. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 89(8), 1618–1624. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2007.12.034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiarello LA (2017). Excellence in Promoting Participation: Striving for the 10 Cs-Client-Centered Care, Consideration of Complexity, Collaboration, Coaching, Capacity Building, Contextualization, Creativity, Community, Curricular Changes, and Curiosity. Pediatric Physical Therapy, 29 Suppl 3, S16–s22. doi: 10.1097/pep.0000000000000382 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Child Count data available at the state and national levels, stratified by child’s age and child’s race and ethnicity. (2005-2018, 12/18/2018). Retrieved from https://www2.ed.gov/programs/osepidea/618-data/state-level-data-files/index.html.

- Constand MK, MacDermid JC, Dal Bello-Haas V, & Law M (2014). Scoping review of patient-centered care approaches in healthcare. BMC Health Services Research, 14, 271. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-14-271 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham BJ, & Rosenbaum PL (2014). Measure of processes of care: a review of 20 years of research. Developmental Medicine and Child Neurology, 56(5), 445–452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Developmental Disabilities Services (DDS), (1995).Established Condition Database – Early Intervention XXX (Blinded). Retrieved from https://docs.google.com/spreadsheets/d/14ZfUsdLaMiv4ULd9oP-xkUVaPkKQQ7KI_yhrPOiFwqA/edit#gid=0

- Family Engagement and School Readiness. (2013). Research to Practice Series. Retrieved from https://eclkc.ohs.acf.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/pdf/rtp-school-readiness.pdf

- Hebbeler K, Spiker D, Bailey D, Scarborough A, Mallik S, Simeonsson R, … Nelson L (2007). Final report of the national early intervention longitudinal study (NEILS). Retirado de: http://www.sri.com/neils/pdfs/NEILS_Final_Report_02_07. pdf .

- Khetani MA, McManus BM, Arestad K, Richardson Z, Charlifue-Smith R, Rosenberg C, & Rigau B (2018). Technology-based functional assessment in early childhood intervention: a pilot study. Pilot and feasibility studies, 4(1), 65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khetani MA, Richardson Z, & McManus BM (2017). Social Disparities in Early Intervention Service Use and Provider-Reported Outcomes. Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics, 38(7), 501–509. doi: 10.1097/DBP.0000000000000474 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King G, Law M, King S, & Rosenbaum P (1998). Parents’ and Service Providers’ Perceptions of the Family-Centredness of Children’s Rehabilitation Services. Physical & Occupational Therapy in Pediatrics, 18(1), 21–40. doi: 10.1080/J006v18n01_02 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- King G, Williams L, & Hahn Goldberg S (2017). Family‐oriented services in pediatric rehabilitation: a scoping review and framework to promote parent and family wellness. Child: Care, Health and Development, 43(3), 334–347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazara A, Danaher J, & Detwiler S (2018). Federal Appropriations and National Child Count 1987–2017. Retrieved from http://ectacenter.org/~pdfs/growthcompPartC-2018-04-17.pdf

- McManus B, Richardson Z, Schenkman M, & ... (2019). Timing and Intensity of Early Intervention Service Use and Outcomes Among a Safety-Net Population of Children. JAMA network …. Retrieved from https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamanetworkopen/article-abstract/2722579 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McManus BM, Richardson Z, Schenkman M, Murphy N, & Morrato EH (2019). Timing and Intensity of Early Intervention Service Use and Outcomes Among a Safety-Net Population of Children. JAMA network open, 2(1), e187529-e187529. Retrieved from https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamanetworkopen/articlepdf/2722579/mcmanus_2019_oi_180312.pdf [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mroz TM, Pitonyak JS, Fogelberg D, & Leland NE (2015). Client Centeredness and Health Reform: Key Issues for Occupational Therapy. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 69(5), 6905090010p6905090011–6905090018. doi: 10.5014/ajot.2015.695001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Neil M E, & Palisano RJ (2000). Attitudes toward family-centered care and clinical decision making in early intervention among physical therapists. Pediatric Physical Therapy, 12(4), 173–182. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Neil ME, Palisano RJ, & Westcott SL (2001). Relationship of therapists’ attitudes, children’s motor ability, and parenting stress to mothers’ perceptions of therapists’ behaviors during early intervention. Physical Therapy, 81(8), 1412–1424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Odom SL, H. M, Blackman JA, Kaual S (2003). Early Intervention Practices Around the World. Baltimore, MD: Brooks Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Patient- and family-centered care and the pediatrician’s role. (2012). Pediatrics, 129(2), 394–404. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-3084 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raghavendra P, Murchland S, Bentley M, Wake-Dyster W, & Lyons T (2007). Parents’ and service providers’ perceptions of family-centred practice in a community-based, paediatric disability service in Australia. Child: Care, Health and Development, 33(5), 586–592. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2214.2007.00763.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross SM, Smit E, Twardzik E, Logan SW, & McManus BM (2018). Patient-Centered Medical Home and Receipt of Part C Early Intervention Among Young CSHCN and Developmental Disabilities Versus Delays: NS-CSHCN 2009–2010. Matern Child Health J, 22(10), 1451–1461. doi: 10.1007/s10995-018-2540-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spiker D, Hebbeler K, Wagner M, Cameto R, & McKenna P (2000). A framework for describing variations in state early intervention systems. Topics in Early Childhood Special Education, 20(4), 195–207. [Google Scholar]

- Statute: Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA), as amended in 2004, Pub. L. No. 108–446 (2004 2004).