Abstract

The field of nanotechnology has been gaining great success due to its potential in developing new generations of nanoscale materials with unprecedented properties and enhanced biological responses. This is particularly exciting using nanofibers, as their mechanical and topographic characteristics can approach those found in naturally occurring biological materials. Electrospinning is a key technique to manufacture ultrafine fibers and fiber meshes with multifunctional features, such as piezoelectricity, to be available on a smaller length scale, thus comparable to subcellular scale, which makes their use increasingly appealing for biomedical applications. These include biocompatible fiber-based devices as smart scaffolds, biosensors, energy harvesters and nanogenerators for human body. This paper provides a comprehensive review of current studies focused on the fabrication of ultrafine polymeric and ceramic piezoelectric fibers specifically designed for, or with the potential to be translated towards, biomedical applications. It provides an applicative and technical overview of the biocompatible piezoelectric fibers, with actual and potential applications, an understanding of the electrospinning process and the properties of nanostructured fibrous materials, including the available modeling approaches. Ultimately, this review aims at enabling a future vision on the impact of these nanomaterials as stimuli-responsive devices in the human body.

Keywords: Poly(vinylidene fluoride), lead-free ceramics, biomaterials, biosensors, modeling, Piezoelectric

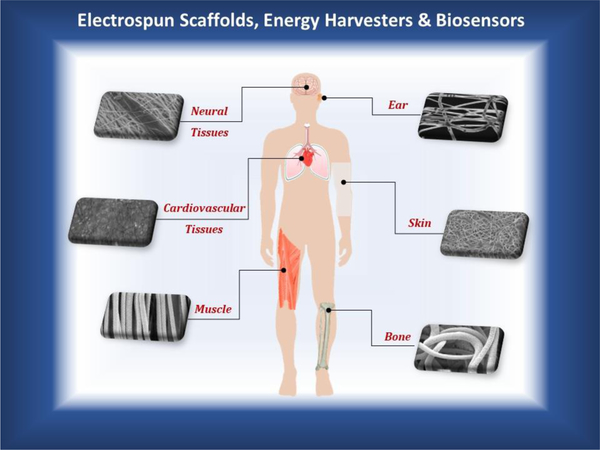

Graphical Abstract

Electrospinning enables the production of smart fibers, including piezoelectric, with a length scale comparable to subcellular scale, therefore relevant for biomedical applications. This paper provides a comprehensive review on the fabrication of piezoelectric ultrafine fibers by providing an understanding of the electrospinning process, the obtained piezoelectric properties, the available modeling approaches, and their current and future applications in healthcare field.

1. Introduction

The evidence of the piezoelectric effect was demonstrated in 1880 by the Curie brothers. They first used the term “piezoelectricity” since its original Greek meaning relates to pressure, namely “pressure electricity”.[1] Since then, with the term piezoelectricity, scientists have been referring to the generation of electrical charges induced by mechanical stress (i.e., direct effect) and vice versa (i.e., indirect or converse effect).[2] Although piezoelectricity is a phenomenon widely found in nature, some synthetic and natural materials that belong to the family of ceramics and polymers have shown significant piezoelectric effects. Perovskite-structured ceramics, such as lead titanate (PT), lead zirconate titanate ceramics (PZT), lead lanthanum zirconate titanate (PLZT), and lead magnesium niobate (PMN) possess the highest piezoelectric properties.[3] However, the concerns about the toxic effects of lead oxides have driven the research seeking other piezomaterials for biomedical uses.[4–6] Consequently, in the last few years, researchers have focused on lead-free piezoelectric materials, aiming to obtain properties comparable to their lead-based counterparts.[7,8] The most important lead-free piezoceramics still possess perovskite-like structures and are barium titanate (BaTiO3), alkaline niobates (K,Na,Li)NbO3, alkaline bismuth titanate (K,Na)0.5 Bi0.5 TiO3, barium zirconate titanate-barium calcium titanate (BZT-BCT) and (Ba,Ca)(Zr,Ti)O3(BCZT).[9–11] In contrast to the intrinsic fragility of these ceramics, with brittleness manifesting also at low tensile strains, piezoelectric polymers have lower density and are more flexible, stretchable, spinnable and, thus, ideal for wearable or implanted devices.[12,13]

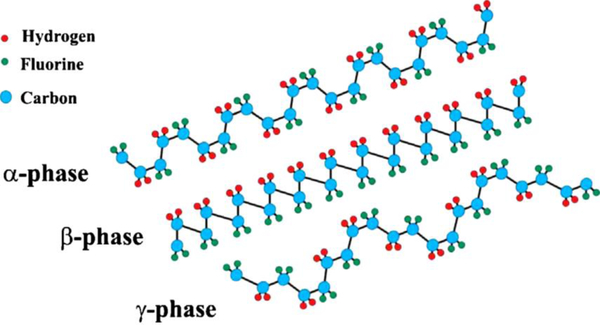

Polymers entitled with piezoelectric properties and usable in contact with the human body include polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF), polyamides, polyvinyl chloride (PVC), liquid crystal polymers (LCPs), Parylene-C, and some polyhydroxyalkanoates, such as poly-b-hydroxybutyrate (PHB),[14] (poly-3-hydroxybutyrate-3-hydroxy valerate) PHBV [15] and some natural biomaterials, such as silk, elastin, collagen and chitin.[16] Owing to their macromolecular nature, semi-crystalline polymers behave similarly to piezoelectric inorganic materials with the advantage of being much more processable and lightweight than piezoelectric ceramics.[4,17] Among the abovementioned polymers, PVDF and its copolymers, such as polyvinylidene fluoride-trifluoroethylene [P(VDF-TrFE)] and poly(vinylidene fluoride-co-hexafluoropropylene) (PVDF-HFP), show a high piezoelectric effect.[18] This character derives from the oriented molecular dipoles formed by a combination of mechanical deformation and electrical poling of the crystallographic phase β.[19] Indeed, the β-phase, which has fully trans-planar zig-zag conformation, is responsible for most of the obtained piezoelectric response due to its polar structure with oriented hydrogen and fluoride unit cells along with the carbon backbone. In addition, the remarkable properties of PVDF-based polymers (i.e., flexibility, transparency, good mechanical strength, and high chemical resistance due to the C-F bond) provide many advantages in a number of relevant healthcare applications, since PVDF is stable under the gamma radiation commonly used for sterilizing medical devices. Finally, similarly to piezoelectric ceramics, PVDF boasts chemical stability, biocompatibility and durability in the human body. Other less studied piezoelectric polymers such as PHB and PHBHV, are still biocompatible, but are biodegradable in the human body, thus being potentially ideal for transient bioimplants. PVDF, but also parylene-C for coating,PVC, Nylon, P4HB are among the ones already approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA).[4,20] P(VDF-TrFE) is a multifunctional copolymer of PVDF in which the β phase is promoted, and therefore the piezoelectricity, with respect to the homopolymer. In addition to the piezoelectric effect, P(VDF-TrFE) displays ferroelectric, pyroelectric and electro-cooling effects as well as superior dielectric permittivity. P(VDF-TrFE) can be handled to fabricate solid parts, films, textiles, and coatings. PVDF-HFP has a lower crystallinity when compared with PVDF, yet presents good ferroelectric and piezoelectric behavior. As the piezoelectric properties are highly dependent on the concerted organization of piezoelectric domains in the bulk materials, ceramics and polymers must be poled with approximately 2 kV∙mm−1 to maximize their performance.[21]

Owing to their specific characteristics, piezoelectric materials have been used in several fields: ultrasonics, robotics, energy harvesters, energy conversion, aerospace, domestic industries, damage detection, automotive engines, sensors and actuators. Yet they still represent a valuable class of materials for bioengineering.[22–25] Furthermore, driven by the growing interest in nanofabrication, researchers have been studying piezoelectric materials at the nanoscale in order to make them a real option for diverse and high performance applications. [26] In particular, piezoelectricity has become very attractive for new generation biomedical nanodevices, as the length scales at which the biological interactions take place approach those of cellular and extracellular components, thus revealing interesting modes for controlling and activating electro-mechanically sensitive cells and enabling innovative tools for nanomedicine. [27] Piezoelectric nanoceramics are being widely used and investigated, and consequently, the assessment of their possible toxic effects, is still a topic of debate. [28]

In view of this and due to the concerns over using toxic lead in health-related applications, scientists have been focused on how to apply new fabrication techniques to the production of lead-free and sustainable piezoelectric nanofibers.[23,29–31] Electrospinning, hence, is a relevant and flexible approach to easily manufacture one-dimensional (1D) nanostructures with a precise tuning of the main parameters (i.e., diameter, composition, and morphology). Electrospun piezoelectric fibers offer excellent properties as a consequence of their surface area-and size-dependent properties, so their employment in a large number of applications has been strongly encouraged.[32,33] However, it is noteworthy that the electrospinning of piezoelectric ceramics is more challenging if compared to their polymer counterparts because of the involvement of hydrolysis, condensation, and gelation reactions.[18] These issues have led to the development of a hybrid process combining electrospinning and sol-gel. This synergic approach allows different sizes, compositions, and morphologies of ceramic nanofibers to be exploited.[34] Similarly, piezoelectric polymers have received notable attention for numerous applications [13,35,36], including the case of electrospun composite fibers made of piezoelectric polymer matrices with nanoceramics as fillers, which can be obtained in a single-step process.[33]

The biomedical field has been taking advantage of these new approaches and scientific progress towards lead-free piezoelectric nanofibers: as examples, self-powered wearable or bio-implantable devices (e.g., nanosensors, energy harvesters, nano-generators), and bioactive scaffolds in tissue engineering.[22,37–40] New interesting approaches employing self-powered bio-implantable systems have also been investigated by integrating piezoelectric nanofiber-based devices inside the human body to convert biomechanical actions (i.e., cardiac/lung motions, muscle contraction/relaxation, and blood circulation) into electric power.[41–43]

Moreover, piezoelectric nanofibers have catalyzed interest for tissue engineering purposes due to their capability of providing electrical stimulation to promote tissue regeneration, thus acting as stimuli-responsive (known as “smart”) scaffolds.[40,44] Indeed, piezoelectric electrospun fibers can provide a number of stimuli for cell growth, cell differentiation, and ultimately tissue function repair, including mechano-electrical, topographical, and physico-chemical stimuli. Submicrometric fibers as obtained via electrospinning can mimic the architecture of extracellular matrix fibrous proteins, thus enabling contact signals and mechanical support for the cells. New researches are focusing on implementing nanodevices able to combine piezoelectricity with biocompatibility to produce piezoelectric scaffolds for electro-mechanically responsive cells.[45]

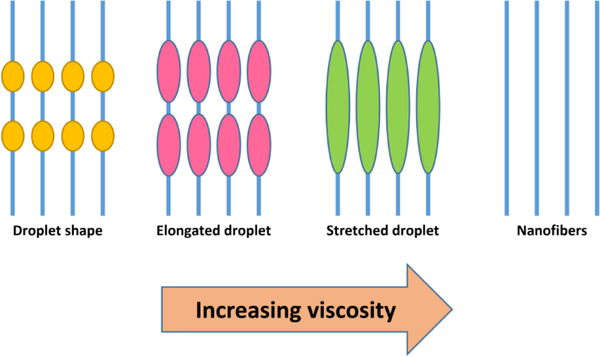

The first patents of the electrospinning process date back to the early 1900s.[46,47] However, its use has become popular in the 20th century, in particular in the biomedical sector.[48] Therefore, electrospinning is considered a relatively young technique that allows the fabrication of fibers offering specific properties useful in many fields (e.g., high surface area to volume ratio and tunable porosity). So far, more than 200 polymers have been processed for a large number of applications.[49,50] With this process, a polymeric solution is extruded from a needle in the presence of an electric field: once this latter overcomes the surface tension of the liquid, a continuous jet is projected onto a collector with a simultaneous evaporation of the solvent. A number of parameters (e.g., solvent properties, solution concentration and viscosity, applied voltage, geometrical and many other parameters) are thus implied in the final outcome, which make this technique as much versatile as complex. Depending on the collector used to deposit the material, it is possible to fabricate fibrous membranes with good mechanical properties such as high elasticity and high strain tolerance and both randomly oriented or aligned fibers, with diameters usually in the range of a few micron down to tens of nanometers, namely ultrafine to nanofibers.[51] These features make electrospun piezoelectric fibers key players health and human body, where such constructs can be used for self-powered wearable or implantable devices for environmental sensing, stimulating/rehabilitating and regenerating tissues, up to sustaining energy needs of any devices.

Highlighting and explaining the recent progress in electrospinning of different biocompatible piezoelectric materials, with a focus on their applications related to the human body, are the intent of this review (Figure 1). After a comprehensive review of biomedical applications of polymeric and lead-free ceramic electrospun piezoelectric fibers, the experimental procedures and techniques to clarify how the electrospinning process affects morphology and piezoelectric properties of the fiber mesh are presented and discussed. Then, mathematical and computational modeling to fabricate and optimize the properties of piezoelectric fibers and fiber meshes are reported. In the last section, this review encompasses the future prospects of electrospinning biocompatible piezoelectric fibers for biomedical applications.

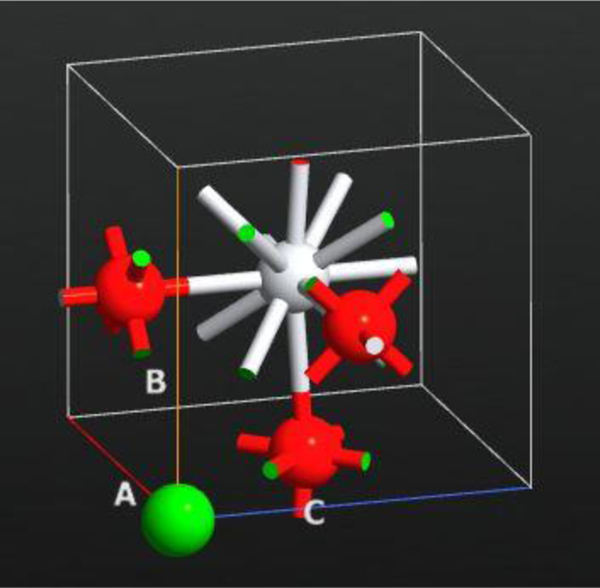

Figure 1.

Schematic depicting the topics covered in this review article: piezoelectric materials (ceramics and polymers) processed via electrospinning to produce piezoelectric nanofibers specific for different human body-related applications. Computational and mathematical modeling, ranging from atomistic to macroscale, represent very useful tools to tune the several parameters involved in the electrospinning of piezoelectric materials by modeling the electrospinning process, as well as the mechanical and electrical properties of the produced piezoelectric fibers and fiber meshes, thus greatly helping in reducing the experimental campaigns to achieve the desired goal.

2. Bio-applications of electrospun polymer-based piezo-fibers

Within the biomedical field, the applications of piezopolymers are much better developed and differentiated according to various tissues and devices than those of piezoceramics, in particular in the form of ultrafine fibers (Figure 2). In particular, the use of the fluoropolymers belonging to the PVDF family in human body application is largely approved for their chemical inertia and stability, as well as their processability. It is a fact that PVDF is not a biodegradable polymer: as a consequence, its natural uses concern flexible permanent devices, recently including those where a transduction function is requested. In fact, due to its piezoelectric properties and biocompatibility, PVDF has become a potential material also as a stimuli-responsive scaffolds for tissue engineering.

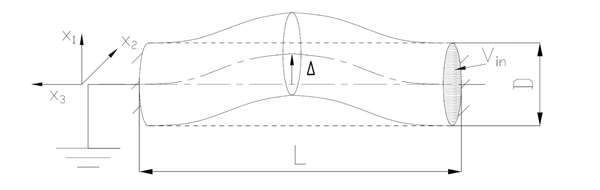

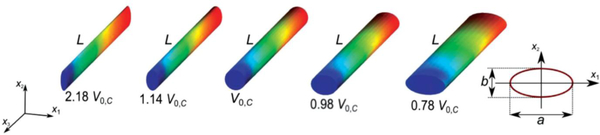

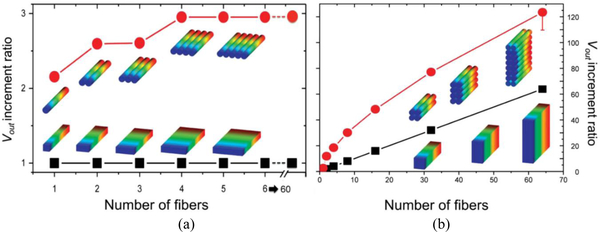

Figure 2.

Current studies on biomedical applications of electrospun tissue engineering scaffolds, energy harvesters and biosensors based on piezoelectric polymer fibers produced via electrospinning. Electrically responsive tissues targeted by researches are neural (brain), sensorineural (inner ear), cardiovascular (heart), skin (epidermis), musculoskeletal (striated muscle and bone). The piezoelectric fibrous materials serve for mechanical support and electrical stimulation of biological tissues and smart devices.

2.1. Tissue engineering scaffolds

Because of some specific functional properties, piezoelectric materials have found many current and potential bio-applications. Tissue engineering approach aims to restore faulty organs and tissues which cannot self-regenerate by developing biomaterial-aided biological substitutes. Biocompatible scaffolds are key components for tissue engineering, because they can guide tissue growth and regeneration across a three dimensional (3D) space. As many parts of the human body, such as bone, dentin, tendon, ligaments, cartilage, skin, collagen, deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA), conceivably have bioelectrical activity and even piezoelectricity, new and challenging research fields are emerging based on the application of biocompatible piezoelectric polymers in active tissue engineering, so as to properly regenerate these specific tissues or heal/support injured functions by giving physiologically relevant bio-signals, such as the electric ones.[52–54]

Under the application of mechanical stress, piezoelectric biomaterials generate transient surface charge variations and subsequently electrical potential variations to the material without the requirement of additional energy sources or wired electrodes. PVDF and its co-polymers (e.g., PVDF-HFP, PVDF-TrFE) in the form of 3D scaffolds can thus provide electrical stimulation to cells to promote tissue regeneration. Since topography of the scaffold has a significant effect on cell behavior and cell morphology, selecting the most suitable design is essential.[55] Several piezoelectric structures including films, nanofibers, porous membranes and 3D porous bioactive scaffolds have been used for bone, muscle and nerve regeneration.[56] In these cases, electrospun piezoelectric nanofiber webs have shown great advantages due to the high surface to volume ratios, high porosity, but reduced pore size with respect to other scaffolding techniques.[57] Because of the fibrous nature of these meshes, pore interconnectivity is maximal; moreover, the internal and external morphology of fibers can be adjusted by controlling the processing parameters. Table 1 shows a comprehensive list of piezoelectric polymer-based fiber meshes fabricated by conventional and customized electrospinning techniques, which have been used or proposed for tissue engineering applications, as grouped by tissue type.

Table 1.

A comprehensive list of piezoelectric polymeric fibers fabricated by electrospinning techniques for tissue engineering applications.

| Polymer | Solvent | Additives | Comments | Fiber properties | Ref. | Potential applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PVDF (MW= 275 000) | DMF:acetone (1:1 v/v) | - | C = 20% (w/w), V = 25 kV, d = 20 cm, flow rate = 0.5 ml h−1 | Fiber diameter: 177 ± 84 nm, β-phase fraction: 72% | [36] | Scaffold for bone tissue engineering |

| PVDF | DMF | - | C = 20% (w/w), V = 25 kV, d=15 cm, flow rate = 0.5 ml h−1 | Fiber diameter: 500 nm | [58] | Scaffold for bone tissue engineering |

| PVDF | DMF:acetone (40/60) | - | C=15%, V= 25 kV, d=15 cm, flow rate = 600 μl h−1 | - | [59] | Scaffold for bone tissue engineering |

| PVDF (Mm= 275000 g mol−1) | DMF:acetone (1:1 v/v) | - | C = 22 w%, V = ±15 kV, d = 18 cm, flow rate = 1.5 ml h−1 | Fiber diameters: PVDF(+) = 1.39 ± 0.58 μm and PVDF(−) = 1.37 ± 0.57 μm. Surface potential of PVDF(−) = −95 mV | [60] | Scaffolds for bone regeneration |

| PVDF (Mw = 275000 g mol−1) | DMF/THF (1:1 v/v) | POSS–EGCG Conjugate | C = 18 w/v%, V= 18 kV, d = 15 cm, flow rate = 2 ml h−1 | Fiber diameter= from 936 ± 223 nm to 1094± 394 nm | [61] | Scaffold for bone tissue engineering |

| PVDF–TrFE (65:35) | MEK | - | C= 25% (w/v), V= 25–28 kV, d= 35 cm, flow rate: 15 ml h−1, Annealing at 135 °C for 96 h followed by ice water quenching for few seconds | Fiber diameter: 6.9 ± 1.7 μm, porosity (%) = 92 ± 5.5, % relative β-phase fraction: 75 ± 3.2% | [62] | Scaffold for bone tissue engineering |

| PVDF–TrFE (70:30 mol%) | MEK | - | C = 20% (w/v), V = 35 kV, d = 15 cm, flow rate: 0.016 ml min−1, rotating speed: 0 to 2500 rpm | Fiber diameter: 1.40 – 2.37 μm | [63] | Scaffold for bone tissue engineering |

| P(VDF-TrFE) (75/25 mol%) | DMF:acetone (6:4 v/v) | - | C = 20 w/v%, V = 15 kV, d = 10 cm, flow rate = 1 ml h−1 | d31 =22.88 pC/N,Maximum Voltage = −1.7 V,current output 41.5 nA | [64] | Scaffold for bone tissue engineering |

| PHB | Chloroform | Polyaniline (PANi) | C=6%, V= 6.5 kV, d = 8 cm, flow rate = 1.5 ml h−1 | - | [65] | Scaffold for bone tissue engineering |

| PVDF | DMF:acetone (3:1 v/v) | - | C=15% (w/v), V=30 kV, d=15 cm, flow rate = 10 ml h−1, rotation speed = 50, 1000, 2000, and 3000 rpm | Fiber diameter: 1.51–1.98 μm | [66] | Scaffold for neural tissue engineering (NTE) |

| PVDF | DMF | - | C = 18% (w/w), V= 8 kV, d= 5 cm | Fiber diameter: 350 nm | [67] | Scaffold for neural tissue engineering |

| PVDF, MW=584,000 | DMAc/acetone (1:1 v/v) | Gold colloidal nanoparticles (Au NPs) | C = 30% (w/v), V=15 kV, d=18 cm, flow rate: 0.5 ml h−1, rotating speed: 2500 rpm | Fiber diameter: 324 ± 18 nm | [68] | Scaffold for nerve tissue engineering |

| PVDF | DMF: acetone (1:1 v/v) | BaTiO3 | C= 20% (w/v), V=20 kV, d=15 cm, Flow rate: 1 ml h−1, rotating speed: 500 to 3000 rpm | Fiber diameter: 400nm, d31=130 ± 30 pmV−1 | [69] | Scaffold for nerve tissue engineering |

| PVDF–TrFE (65/35) | MEK | - | C = 15% and 25% (w/v) | Crystallinity (%): as-spun aligned fiber: 64.39%; annealed aligned fiber: 70.64% | [70,71] | Scaffold for neural tissue engineering |

| P(VDF-TrFE) | MEK | - | - | Average fiber diameter: 3.32 ± 0.2 μm | [72] | Scaffold for nervous tissue repair |

| PVDF-TrFE (70/30) | MEK | ... | C = 20% (w/v), V =2 5 kV, flow rate: 3 ml h−1, rotating speed: 2500 rpm, d = 30 cm, annaling at 135ºC for 96 h | Average fiber diameter: 1.53 ± 0.39 μm | [73] | Scaffold for nerve tissue engineering |

| PVDF | DMF | - | C = 20 w%, V = 25 kV, d= 15 cm, flow rate = 0.5 ml h−1 | Fiber diameter: 200 ± 96 nm | [74] | Skeletal muscle tissue engineering (muscle regeneration) |

| P(VDF-TrFE) (65/35%) | MEK | - | C = 12%–18% (w/v), V= 15–35 kV | Average fiber diameter of 970 ± 480 nm, mean pore diameter of 1.7 μm | [75] | Scaffolds for skin tissue engineering |

| polyurethane/polyvinylidene fluoride (PU/PVDF) (1/1) | THF/DMF (1:1 v/v) | - | C= 12% (w/v, g ml−1), V = 15 kV, d = 20 cm, flow rate = 0.8 ml h−1 | Fiber diameter: 1.41 ± 0.32 μm, pore size of the scaffolds: 11.47 ± 1.14 μm, d33 = 11.24 ± 1.2 pC N−1 | [76] | Skin tissue engineering, wound healing application |

| P(VDF-TrFE) (65:35) | MEK | - | C = 15% and 25% (w/v) | Fiber diameter: 575 ± 139 nm, fiber alignments: 89% ± 10%, elastic modulus: 359.77 MPa, tensile strength: 21.42 MPa | [77] | Cardiovascular tissues using stem cells |

| P(VDF-TrFE) | MEK:DMF (1:2 v/v) | - | C = 3%, 5%, 7%, 9%, 11% (w/w), V= 20 kV, d = 16 cm, flow rate = 10 ml h−1 | Fiber diameter: 0.38 – 1.71 μm, tensile strength:15.3 MPa, Relative elongation %= 122 | [78] | Tissue engineering |

| P(VDF-TrFE) (60:40 molar ratio, MW = 500,000 g mol−1) | Acetone | ZnO: 0%,−4% (w/w) | C = 14% (w/v), V =1 8 kV, d = 10 cm, flow rate: 1.5 ml h−1 | Average diameter: 1035 – 1227 nm | [79] | Tissue engineering scaffold |

| PVDF, Mw = 700000 g mol−1 | DMF | Ionic liquid [C2mim][NTf2] = 0, 5 and 10 (w/w) | C =15/85 (w/v), V= 1.3 kV cm−1, d=15 cm, flow rate = 0.5 ml min−1, collector speed = 1000 rpm | Fiber diameter: 500–700 nm | [80] | Tissue engineering scaffold |

| P(VDF-TrFE) | DMF | Fe3O4 NPs (size 15 nm) | C = 18% (w/w), V = 10 kV, d = 5 cm, flow rate: 1 ml h−1 | Fiber diameter: 288 nm | [67] | Tissue engineering |

[Mw = molecular weight; d = working distance; C = concentration (polymer/solvent), v = volume, w = weight, V = potential, NP = nanoparticles, rpm =rounds per minute; Methyl ethyl ketone (MEK); Dimethylformamide (DMF); Tetrahydrofuran (THF); Dimethylacetamide (DMAc)].

Orthopedic surgery accounts for an increasing market, as over two million bone grafting procedures are annually performed worldwide. However, the optimal bone regeneration and repair remains a challenge, especially in the cases of complicated healing and large defects. Innovative approaches try to mimic tissue physiology with new materials or growth factors. Bone is a tissue with piezoelectric constants similar to those of quartz, primarily by virtue of collagen type I, the main component of the bone organic extracellular matrix (ECM). For this reason, the application of piezoelectric materials in bone tissue engineering has been invoked to support tissue function. [81] Since the role of electric signals in bone is still poorly understood, several studies have investigated the effect of piezoelectric materials, by their properties and structure, in the osteogenic process.

For example, Timin et al. demonstrated that piezoelectric properties of PHB and polyaniline (PANi)-loaded PHB scaffolds promoted adhesion of human mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) compared to that of the non-piezoelectric polycaprolactone (PCL) scaffolds.[65] Ribeiro et al. [58] investigated the osteogenic properties of PVDF fiber meshes, and poled and non-poled β-PVDF films by analyzing new bone formation in vivo. They concluded that bone regeneration does require mechano-electrical stimuli. In comparison to the film, the piezoelectric fibrous structure enhanced bone regeneration with evidence of inflammatory cell infiltration. The process parameters of electrospinning may also affect the piezoelectric output and thus biological response. Damaraju et al. [36] have prepared PVDF fibers by electrospinning at different voltages (12 kV and 25 kV) for bone tissue engineering. Human MSCs cultured on PVDF produced at −25 kV scaffolds revealed the maximum alkaline phosphatase activity, an early marker of osteogenesis, in comparison to PVDF produced at −12 kV scaffolds and the tissue culture polystyrene (TCP) and also showed early mineralization by day 10, thus clearly indicating its potential for bone regeneration. 3D fibrous scaffolds of P(VDF-TrFE) with the greatest piezoelectric activity have also been shown to stimulate cell function in a variety of cell types.[62]

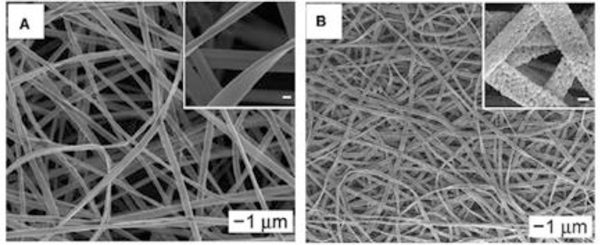

Moreover, different cells and tissues have revealed different sensitivity to piezoelectric signals. By mimicking the physiological loading conditions in structural tissues through dynamic loading of piezoelectric P(VDF-TrFE) fibrous scaffolds cultured with MSCs, it was interestingly demonstrated that lower levels of piezoelectricity promoted chondrogenesis (i.e., cartilage formation), whereas higher levels promoted osteogenesis (i.e., bone formation). This work is meaningful as it would allow stem cell fate to be controlled in difficult body settings, such as the osteo-chondral interface, by acting on the differential piezo-properties of the scaffolds. Scaffold topography, including surface texture, is also very important as it enhances the surface area for cell adhesion and ECM deposition, including bone matrix. Shifting from smooth to nanoporous surface in P(VDF-TrFE) ultrafine fibers can be obtained during electrospinning by changing the environmental conditions, such as relative humidity [82]. By using methyl ethyl ketone (MEK) as a solvent, the nanoporous structure of ultrafine fibers was obtained (Figure 3).

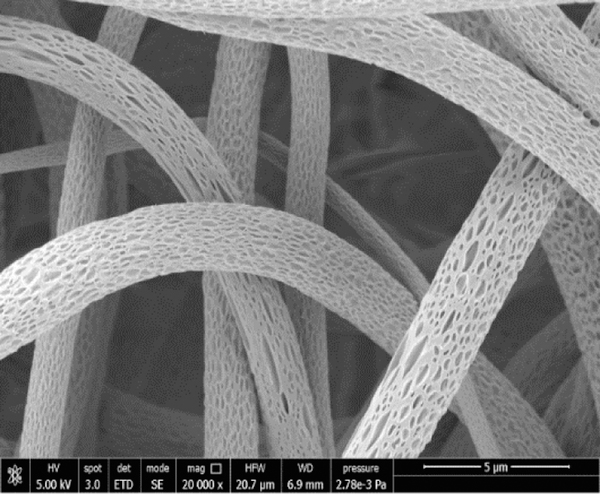

Figure 3.

SEM micrograph of nanoporous surface of P(VDF-TrFE) electrospun ultrafine fibers obtained by using MEK as a solvent and > 40% humidity. Unpublished original picture by the authors.

The cell culture results revealed that this piezoelectric polymeric scaffold induces human MSC growth and accelerates osteogenic differentiation. PVDF is a hydrophobic polymer. To improve the epiezoelectric properties and wettability of PVDF, Kitsara et al. [59] employed electrospinning and oxygen plasma post-modification for obtaining PVDF nanofibrous scaffolds. Osteoblast cultures showed better cell spreading and scaffold colonization in plasma-treated electrospun scaffolds with highly piezoelectric and hydrophilic properties (Figure 4). They also induced intracellular calcium transients and could stimulate excitable cells, namely, osteoblasts, without the need for an external power source, thus demonstrating the versatility of these devices for biological interactions. [59]

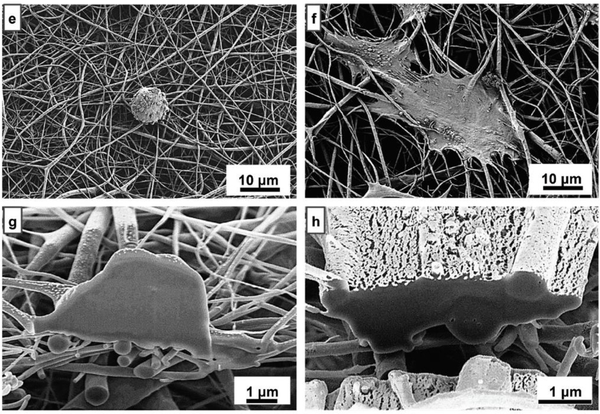

Figure 4.

Saos-2 cells cultured on PVDF electrospun samples: (e, f ) hydrophobic and hydrophilic PVDF electrospun scaffolds, respectively; (g, h) SEM-FIB cross-sections of Saos-2 cells grown on hydrophobic and hydrophilic electrospun scaffolds, respectively. Adapted with permission.[59] Copyright 2019, The Royal Society of Chemistry.

The electric properties of the scaffold surface also give signals influencing cell behavior, therefore several scientists are studying diverse ways to improve them. By applying positive and negative voltage polarities during electrospinning, Szewczyk et al. prepared two types of scaffolds, i.e., PVDF(+) and PVDF(−), to control their surface potential. They demonstrated that surface potential has a significant effect on cell shape and adhesion via filopodia and lamellipodia formation. Increased cell viability/proliferation was found in the PVDF(−) samples and they also exhibited a much higher cellularity in comparison with the PVDF(+) samples, since their surface potential (i.e., −95 mV) was very close to the membrane potential of MG63 osteosarcoma cells (−60 mV). Collagen mineralization was enhanced by tuning the surface potential of the fibers. After 7 days in osteoblasts culture, PVDF(−) scaffolds showed well-mineralized osteoid formation, therefore, it is entitled for the most efficient application in bone regeneration.[60]

Wang et al. investigated the effect of dynamic electrical stimulation on mouse osteoblastic cell (MC3T3-E1) adhesion and proliferation on annealed P(VDF-TrFE) and electrically poled P(VDF-TrFE) scaffolds. The results highlighted that the cells were elongated and oriented along the direction of nanofibers. Electrical poling led to a higher β-phase content of the fiber meshes (69.2%) than annealing (46%) and subsequently higher cell proliferation rate [64]

To improve antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties which are important for the regeneration of damaged bone, Jeong et al. developed composite PVDF nanofibers including polyhedral oligomeric silsesquioxane–epigallocatechin gallate (POSS–EGCG) conjugate. The presence of POSS–EGCG conjugate led to formation of 3D interconnected porous structures with improved piezoelectric and mechanical properties, which in turn enhaced the proliferation and differentiation of osteoblasts (MC3T3-E1) on the scaffold. [61]

As a part of the musculoskeletal system, also muscles can be affected by several damages. Among them, heart is a semi-striated muscle that plays a vital role, thus being the leading cause of death together with cancer. Electroactive polymers displayed an innovative potential for muscle tissue regeneration, since muscle reacts to electrical and/or mechanical stimulation and retains a hierarchical fibrillar structure.[83] Accordingly, Martins et al. [74] investigated the effect of polarization and morphology of electroactive PVDF nanofibers on the biological response of myoblasts. It has been shown that the negative surface charge on aligned PVDF scaffolds provided suitable stimuli for proper muscle regeneration.

Hitscherich et al. [77] demonstrated the potential application of electrospun P(VDF-TrFE) scaffold for cardiovascular tissue engineering. Their outcomes showed the desirable adhesion of cells that initiated spontaneous contraction within 24–48 h post seeding. Live/dead assay also revealed 99.90% cell viability on day 3 and 99.70% cell viability on day 6 with no significant changes. To improve cell adhesion, Augustine et al. [79] generated a novel nanocomposite scaffold composed of ZnO NPs and P(VDF-TrFE) fibers to elicit hMSC proliferation and angiogenesis by exploiting the piezoelectric properties of its components and the reactive oxygen species (ROS)-mediated proliferation induced by ZnO NPs. By applying 2% w/w ZnO, the scaffolds were cytocompatible and supported cell adhesion. In vivo studies in rats have confirmed the nontoxicity of the P(VDF-TrFE)/ZnO scaffolds and their ability to promote angiogenesis. In another study, [67] Fe3O4 magnetic NPs have been added into P(VDF-TrFE) nanofibers. Under optimal conditions, the incorporated NPs were homogeneously dispersed inside the fibers without altering the piezoelectric crystalline phase of the P(VDF-TrFE) nanofibers. The results of a preliminary cell culture showed a good cytocompatibility of these composite fibers.

Gouveia et al. produced scaffold based on a PCL magnetic nanofilm (MNF) covered with P(VDF-TrFE) microfibers to preserve the contractility of cardiomyocytes and promote cell–cell communication. The maximum piezoelectric constant that was reached is d14 = 11.1 pm V−1. The scaffold indeed promoted rat and human cardiac cell attachment and the presence of MNF increased contractility of the cardiac cells cultured in the scaffold.[84]

Piezoelectric fibrous scaffolds have also received considerable interest for neural tissue engineering, where electric signals are of utmost importance for nerve function.[66–72] Indeed, it is widely known that nerve damage, by traumatic, congenital and degenerative diseases, often has a dismal prognosis for which many efforts are currently in place. Neural tissue engineering aims to restore nerve function by reducing the fibrous scar and connecting nerve segments, also aided by transplantation of neural stem cells. The particular micro/nanofibrous architecture of electrospun scaffolds, together with electrical activity, has appeared of great importance for such a challenge. Electrospun scaffolds can have random up to aligned fibers to simplify neurite extension via contact guidance. It has been verified that PVDF nanofibers may serve as instructive scaffolds for monkey neural stem cell (NSC) survival and differentiation, thus disclosing great potential for neural repair. Fiber alignment, which governs the stiffness and piezoelectric character of the scaffolds, had a significant effect on the growth and differentiation capacity of NSCs into neuronal and glial cells. This study also indicates that fiber anisotropy plays an important role in designing desirable scaffolds for tissue engineering.[66] Moreover, Lhoste et al. [67] demonstrated that the neurons cultured on aligned and plasma treated PVDF nanofibers showed an enhanced outgrowth of neurites in comparison to that observed on random nanofibers or aligned fibers without plasma treatment, which concur to support the fact that PVDF hydrophobicity/hydrophilicity ratio should be balanced to improve cell ingrowth within the fibers. [59]

The importance of fiber alignment in neural tissue engineering was confirmed by other studies, which have investigated the effect of fiber orientation and annealing process on neurite outgrowth.[70,71] Lee et al. [70] demonstrated that P(VDF-TrFE) aligned fibers directed the neurite outgrowth, while they extended radially on the randomly oriented P(VDF-TrFE) fibers. Annealing the scaffolds above the Curie temperature led to an increase of the amount of β-phase crystals, thereby enhancing their piezoelectric properties. Annealed aligned P(VDF-TrFE) fibers revealed the maximum neurite extension in comparison with annealed and as-spun random P(VDF-TrFE) scaffolds. Arinzeh et al. [71] concluded that the differentiation of human neural stem/precursor cells (hNSC/NPC) on electrospun piezoelectric fibrous scaffolds mostly induced the expression of neuron-like β-III tubulins, while on nonpiezoelectric laminin-coated plates, mainly nestin. Fiber morphology and contact guidance, crystallinity and consequently the piezoelectricity of the P(VDF-TrFE) scaffolds, alignment, and annealing of the microfibers had a significant effect on neurite extension and differentiation of hNSC/NPCs to neuron-like β-III tubulins.

In another study, Motamedi et al. [68] successfully prepared fully aligned PVDF nanofibrous high-surface area mat with enhanced piezoelectric properties by doping laser ablated Au nanoparticles (Au NPs) and investigated the application of these fibers in nerve tissue engineering. Their results showed that Au NPs/PVDF composite nanofibers have the ability to encourage the growth and adhesion of cells without any toxicity. Results also demonstrated normal proliferation beside elongated and spread out morphology after culturing for 24 h.

Differently, Lee et al. [72] reported that fiber alignment had no significant effect on the differentiation of neural stem/progenitor cells (hNPCs) into the neuronal lineage while annealing led to enhancement of neuronal differentiation which displays higher piezoelectricity, as indicated by the higher fraction of cells expressing β-III tubulin.

Recently, Wu et al. demonstrated aligned PVDF-TrFE fibrous scaffolds supported Schwann Cells (SCs) growth and neurite extension and myelination. SCs were oriented and neurites extended along the length of the aligned fiber. They concluded that aligned PVDF-TrFE fibers might play a significant role in directional axon regeneration and they might be a promising scaffold to restore the aligned anatomical structure of damaged spinal cord tissue.[73]

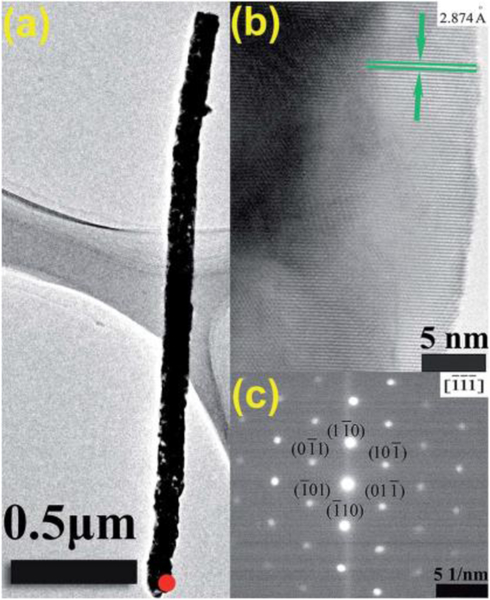

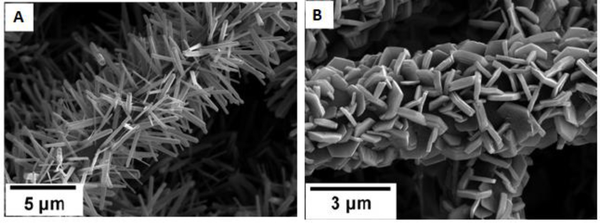

To improve piezoelectric properties, which could be useful in cochlear nerve stimulation in deaf persons, Mota et al. [69] added BaTiO3 NPs inside the ultrafine PVDF fibers and showed that piezoelectric coefficients proportionally increased with BaTiO3 concentration, namely about 2 times with 20% BaTiO3 weight content (Figure 5). Preliminary in vitro tests using SHSY-5Y neural cells displayed increased viability under physiology-simulated culture conditions, thus implying efficiency of these composite as a suitable interface for neurites. The potential use of fibrous P(VDF-TrFE) as a scaffold for nerve stimulation is thus suggested.

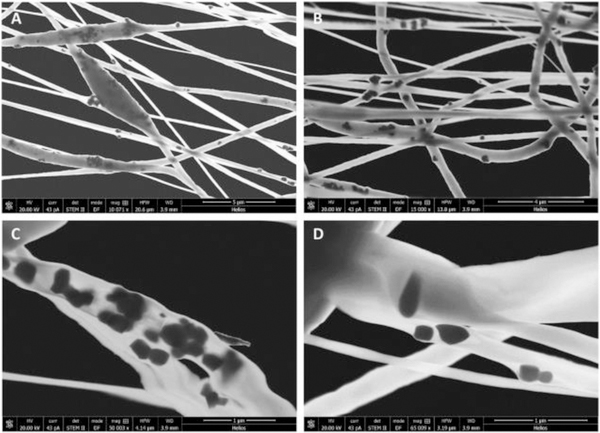

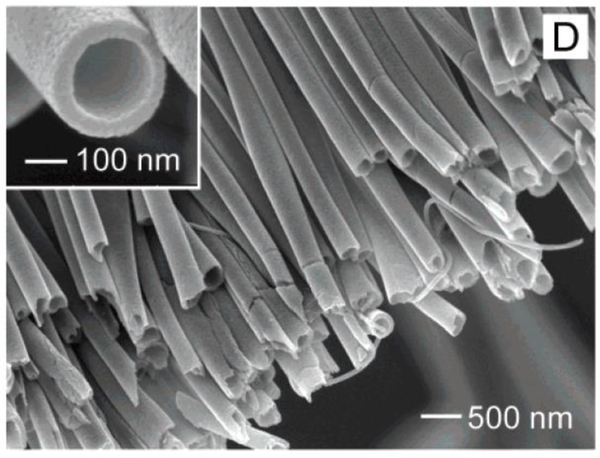

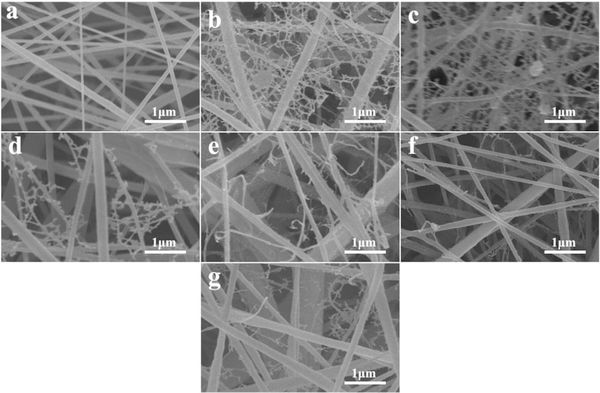

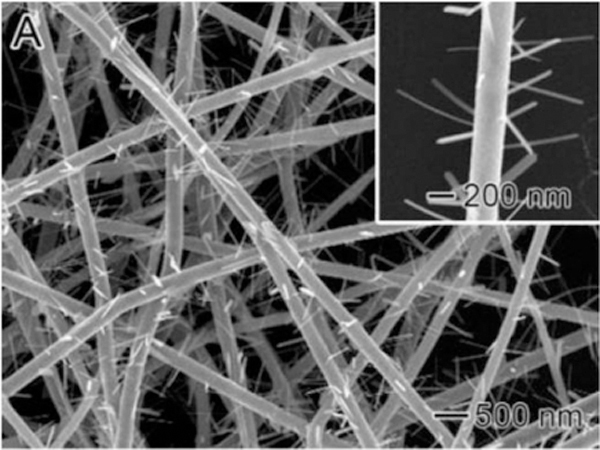

Figure 5.

STEM micrographs of BTNP/PVDF 10/90 electrospun fibers obtained with a collector tangential velocity of 3.7m·s−1 at different magnifications in the range of 10,000x to 65,000x. (A, B) dispersion of BTNPs inside the electrospun fibers; (A) beads induced by the presence of BTNP aggregates; (C) BTNP aggregates inside an electrospun fiber; and (D) BTNP dispersed inside an electrospun fiber. Reproduced with permission. [69] Copyright 2017, Elsevier.

Skin is a tissue rich in collagen type I fibers, which also contains mechanoceptors as sensorial cells. Therefore, it was considered for tissue engineering using electrospun piezoelectric polymers. Skin is in fact our main barrier towards the external world and can be damaged by wounds, burns and sores, which hamper its protective effect from infections, water content and temperature control in the human body. Human skin fibroblasts were cultured on a 3D fibrous scaffolds of P(VDF-TrFE), observing perfectly spindle shaped cells on day 7, which may hold promise for skin regeneration (Figure 6). [75] The efficacy of electrospun polyurethane/PVDF piezoelectric composites for wound healing application has been investigated. [76] The scaffolds were exposed to alternative deformation and shown higher migration, adhesion, and secretion in comparison to the pure polyurethane which led to faster wound healing. In vivo assays indicated that mechanical deformation of scaffold induced by animal movements led to enhancement of fibroblast activities due to the piezoelectric stimulation.

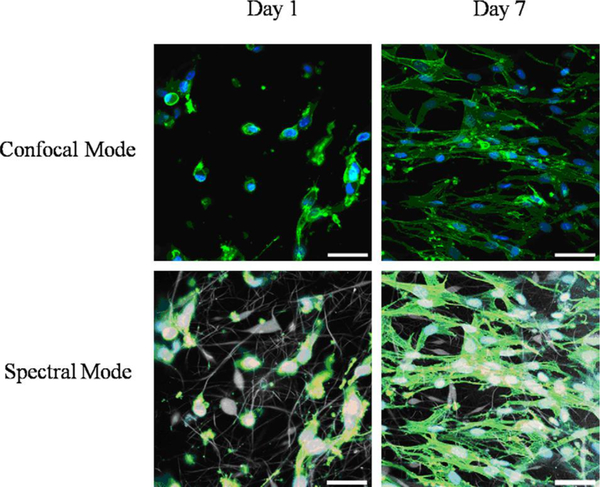

Figure 6.

Confocal fluorescence microscopy images of human skin fibroblasts attached to P(VDF-TrFE) fibers after 1 and 7 days of cell culture (40x objective; cytoskeleton, green; nucleus, blue; scale bar 50 μm). Reproduced with permission. [75] Copyright 2010, Elsevier.

As shown, the applications of polymeric piezoelectric fibers in tissue engineering are many and include non-bioresorbable piezoelectric polymers, such as those of PVDF family, to take advantage of the highest piezoelectric properties. Electrospinning approaches are being developed to this purpose, in order to downscale electric signals to cellular level by means of ultrafine and nanometric fibers. In tissue engineering, the fiber orientation and surface properties may play key aspects, which are still under investigation. On the other hand, the importance of piezoelectric and electric signals in normal and pathologic states and their presence in biologic tissues is a topic of recent studies. As a consequence, even though the applications of piezoelectric fibrous materials have not reached the bedside yet, they are tremendously helping in comprehending the role of bioelectricity and the possibility to use it to induce, control, inhibit and accelerate tissue regeneration. It is expected that this topic would greatly increase, and even become dominant in the research of the near future.

2.2. Biosensors

A transducer is a device that can convert two different forms of energy due to its inherent properties. If energy is transformed to measure or detect a signal or stimulus in the environment, the transducer properly functions as a sensor.[85] A biosensor is an analytical device, which is able to detect the chemical substance that incorporates a biological component with a physicochemical detector. Recently, novel biosensors that are based on biocompatible piezoelectric materials have received considerable attention. Polymer-based piezoelectric materials are flexible and can deform under smaller applied forces which makes them suitable candidate for detecting many mechanical-like signals in the human body, such as pressure sensing applications.[86] They are also able to detect and react to an electrical stimulus that can be used to perform a correction by deformations generated by mechanical actions (e.g., forces from pressures or vibrations).[87] Some outstanding applications include healthcare, health monitoring, motion detection, among others,[88–91] since they can detect human physiological signals, such as pulse and breathing.[92] Such signals will give information enabling vital function monitoring and life style awareness. For their flexibility, piezoelectric polymers are, indeed, suitable candidates for mechanical (pressure) sensors if applied onto skin or integrated inside wearable/portable electronics. Moreover, due to their piezoelectric effect, the polymer is able to change its polarization state under small external stimulation, and the response of the sensor is sufficiently fast.[93]

Biosensors using surface acoustic waves (SAWs) are also used to perform detection activities to find dangerous agents, both infectious and poisonous agents. [87] Piezoelectric polymeric devices with different structures have been proposed to get high sensitivity, flexibility, repeatability, and wide working range. In recent years, nano-/micro-structures, such as nanofibers, have been implemented into the basic polymeric structure to improve the performance of these transducers. Electrospun piezoelectric fibers have been reported to be biocompatible and have been considered promising for biological sensor applications (Table 2).

Table 2.

Comprehensive list of piezoelectric polymeric fibers fabricated by electrospinning techniques for biological sensor applications.

| Polymer | Solvent | Additive | Comments | Fiber properties | Ref. | Potential applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PVDF (Mw =534,000 g∙mol−1 | DMF:acetone (2:3 w/w) | - | C = 12% (w/w), V = 9–18 kV, d = 15 cm, flow rate = 0.01–0.04 ml min−1, T = 22°C, humidity = 50% −60% | Fiber diameter: 20–800 nm | [94] | Flexible force sensors for sensing garment pressure, blood pressure, heartbeat rate, respiration rate and accidental impact on the human body |

| PVDF (Mw: 275,000) | DMF:acetone (8:2 v/v) | - | C = 15% (w/w), V = 13 kV, d = 15 cm, flow rate = 50 μL min−1 | Fiber diameter: 150 nm | [95] | Nanosensors |

| PVDF (MW=141,000 g∙mol−1) | DMF:acetone (3:2 w/w) | - | C = 18%, V = 6 kV, d = 4 cm, flow rate= 100 μl h−1 | Fiber diameter: 332 nm, maximal piezoelectric output voltage: 100–300 mV | [96] | Vibration sensor |

| PVDF (Mw~180 kDa) | DMF:acetone (7:3 v/v) | - | C = 27% (w/w), V = 15 kV, d = 15 cm, flow rate = 0.3 ml h−1, rotating speed = 800 rpm | Average diameter: 417 ± 88 nm | [97] | Piezoelectric Sensors |

| PVDF (MW: 275,000 g∙mol−1) | DMF:acetone (4:6 v/v) | - | C = 20% (w/w), V = 15 kV, d = 15 cm, flow rate = 1 ml h−1, speed = 100 rpm | Fiber diameter: 310 ± 60 nm | [98] | High-sensitivity acoustic sensors |

| P(VDF-TrFE) (55:45 and 77:23 molar ratios) | DMF:acetone (3:2 w/w) | - | C = 12% (w/v), V = 12 kV, flow rate = 1.6 ml h−1 | - | [99] | Flexible pressure sensors |

| P(VDF-TrFE) (65:35%) | MEK | - | C = 15% (w/w), V = 10 kV, d= 10 cm, flow rate = 0.5–0.9 ml h−1 | Fiber diameter: 360 nm, voltage response sensitivity = 50 V N−1 | [100] | Biosensor |

| P(VDF-TrFE) (75:25 w/w) | DMF:acetone (3:2 v/v) | - | C = 21% (w/w), V=30 kV, d= 6 cm, flow rate = 1 ml h−1, speed = 4000 rpm | Fiber diameter: 260 nm, overall porosity of 65% | [101] | Flexible piezoelectric sensors |

| P(VDF-TrFE) (77:23 mol%) | - | - | V = 20 kV, flow rate = 1 ml h−1, rotational speed = 1000 rpm | - | [102] | Flexible nano-generators and nano-pressure sensors |

| P(VDF-TrFE) (70:30 mol%) | DMF:acetone (40:60 v/v) | - | C = 14%, 18%, and 22% (w/v), V = 15 kV, d = 20 cm, flow rate = 0.2 ml min−1 | Fiber diameter= 520 nm to 1.5 μm | [103] | Flexible and stretchable piezoelectric sensor for wearable devices, medical monitoring systems, and electronic skin |

| P(VDF-TrFE) | MEK | - | V = 5 kV, d = 10 cm, flow rate = 300 μl h−1 | Average fiber diameter = 500 nm | [104] | Transducer for sensing application |

| PVDF (Mw=100,000 g∙mol−1) | DMF | hydrated salt NiCl2.6H2O (NC) 0.5 (w/w) | C = 25% (w/w), V = 15 kV, d= 15 cm, flow rate = 0.9 ml h−1 | β phase fraction of (PVDF NC): 0.92 | [105] | Sensors which can be used in health monitoring and, biomedical applications |

| PVDF | DMF:acetone (60:40 w/w) | BaTiO3 NPs | C = 20% (w/w), V = 8 kV, d = 22 cm, rotating speed = 162 rpm | Fiber diameter: 200 nm | [106] | Wearable smart textiles and implantable biosensors |

| P(VDF-TrFE) (75:25) | DMF:acetone (1:1 v/v) | (0.78Bi0.5Na0.5TiO3–0.22SrTiO3) ceramic | V = 10 ∼ 15 kV, d =10 cm, flow rate = 1.0 ml h−1 | Fiber diameter: 100–300 nm. | [107] | Frequency sensor applications |

| P(VDF–TrFE) (60:40) (Mw= 500,000 g∙mol−1) | Acetone | ZnO NPs (1%, 2% and 4% w/w) | C = 14% (w/w), V = 18 kV d= 10 cm, flow rate = 1.5 ml h−1, rotating velocity = 1000 rpm | Incorporation of ZnO NPs enhanced the formation of β phase | [108] | Acoustic biosensors |

| PVDF (Mn=543,600) | DMF:acetone (2:3 w/w) | Silver nanowires (1.5%) | C = 15% (w/v), V = 12 kV, d = 16 cm, flow rate = 1 ml h−1 | Fiber diameter: 200–500 nm, d33 = 29.8 pC N−1 | [109] | Human-related applications such as force sensors |

| PVDF | DMSO:acetone (1:1 w/w) | MWCNTs (0.03% and 0.05% w/w) | C =1 6%, 18%, 20% (w/w), V = 1×107 V m−1, flow rate = 0.001 ml min−1, rotating velocity = 900 rpm | Fiber diameter: from 200 nm to few μm | [110] | Highly durable wearable sensor applications |

| P(VDF-TrFE) | DMF:acetone (1:1 v/v) | Grapheme (rGO) (80:20 w/w) | C = 20% (w/w), V = 10 kV, d = 10 cm | High sensitivity (15.6 kPa−1), low detection limit (1.2 Pa) | [111] | Highly sensitive piezo-resistive pressure sensors |

| Composite of (PVDF) and poly(aminophenylboronic acid) (PAPBA) | DMF:acetone (7:3 v/v) | - | Flow rate = 10 ml h−1, V = 25 kV, d = 15 cm | Fiber diameter 150 nm | [112] | Biosensor |

| Core-shell: The core = (poly(3,4-ethylene dioxy thiophene) poly(styrene sulfonate) and poly vinyl pyrrolidone (PVP), The shell: P(VDF-TrFE) (70:30) | DMF for core and DMF:MEK (25:75) for shell | - | The core and shell solutions were kept at flow rates of 1 and 3 ml h−1, respectively. Shell concentration: 14% (w/v) | - | [113] | Sensors for endovascular applications |

| P(VDF-TrFE) (75:25), polyaniline-polystyrene sulfonic acid Marı (PEDOT-PSS) | DMF | - | C = 1%, 3%, 5%, 7%, 9%, 11%, 13%, 15% (w/w), V = 10 kV and d = 15 cm. | - | [114] | Sensor |

| PVF2-TrFE (75:25), poly(3,4-thylenedioxthiophene)-poly(styrene sulfonate), (PEDOT-PSS) | DMF | - | C = 13%, 10%, 7%, 5%, 3% (w/w), V= 8–10 kV | - | [115] | Supersensitive sensors |

| PVDF | DMF:acetone (3:1 v/v) | - | C = 15 w%, d = 3 cm, V = 10 kV, rotating velocity = 60 rpm | Open-circuit voltage generated from active sensor was around 70 mV | [116] | Wearable self-powered sensor |

[Mw = molecular weight; d = working distance; C = concentration (polymer/solvent), v = volume, w = weight, V = potential, NP = nanoparticles, rpm =rounds per minute; Methyl ethyl ketone (MEK); Dimethylformamide (DMF); Dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO)].

For their durability, chemical inertia and piezoelectric response, PVDF and its copolymers have easily found application as sensors. The key advantage of electrospinning relies on the possibility of maximizing the surface area within a flexible support, suitable for being in contact with the human body.

By using a mixture of DMF and acetone as solvents, Wang et al. [94] developed a force sensor based on electrospun PVDF nanofibers, meeting high flexibility and breathability, able to be exploited as a dedicated human-specific sensor. Furthermore, by adding a solvent with a low boiling point (e.g., acetone), it was observed also an increase of the β-phase structures. It has been demonstrated that electrospun PVDF fibrous membranes with high β-phase content and excellent piezoelectricity may be used as nanosensors.[95]

In another study,[97] a highly durable PVDF nanofiber-based sensor was fabricated on printed electrodes with silver nanostructures without any additional poling processes. Results revealed that the voltage and current were strongly influenced by the actual contact areas between the electrodes themselves and the PVDF nanofibers. Lang et al. [98] produced high-sensitivity acoustic sensors from PVDF nanofiber webs and results showed a sensitivity of 266 mV∙Pa−1, which was five times higher than the sensitivity of a commercial PVDF film device. In another research,[117] the assembled PVDF piezoelectric nano/micro-fibers were used to develop a sensor-embedded garment able to identify specific human motions (e.g., skin wrinkle/eye blink and knee/elbow bending) (Figure 7).

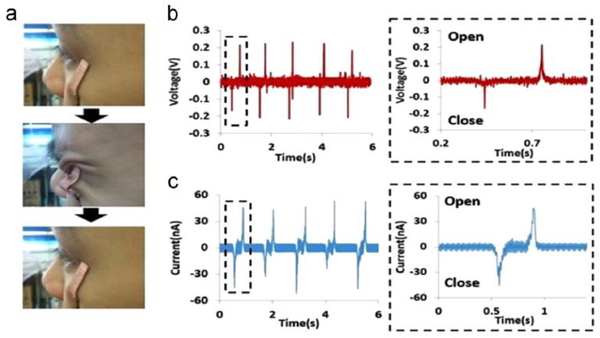

Figure 7.

Performance of the highly flexible self-powered sensing elements (SSE) to detect skin movement. Picture of the SSE on face skin (a). (b) Output voltage and (c) current generation of the sensors induced by one eye blinking. Adapted with permission. [117] Copyright 2015, Elsevier.

Ren et al. [99] fabricated a pressure sensor using a P(VDF-TrFE) nanofiber web with several different concentrations of TrFE in the copolymer. As a result, the authors improved sensitivity reaching 60.5 mV∙N−1 with the P(VDF-TrFE; 77/23) specimen. Finally, they also demonstrated that a P(VDF-TrFE; 77/23) sensor based allows a reliable measure for dynamic forces up to 20 Hz.

Beringer et al. [100] used aligned P(VDF-TrFE) nanofibers interfaced with a flexible plastic substrate to create a device able to evaluate the voltage response. This biosensor was capable of producing from −0.4 V to +0.4 V when loaded by cantilever force of 8 mN at 2 Hz and 3 Hz. This equipment can be also used to assess the electromechanical behavior of cellular-powered nanodevices. In another work, Persano et al. [101] developed bendable piezoelectric sensors based on P(VDF-TrFE) electrospun aligned nanofibrous arrays in a flexible piezoelectric nano-generator (PENG). The device had special piezoelectric properties and enabled high sensitivity to measure pressures up to about 0.1 Pa. Mandal et al. [102] studied the piezoelectricity in an electrospun P(VDF-TrFE) web by using polarized FTIR spectroscopy and electric signals from the pressure sensors based on the electrospun mesh. Furthermore, the feasibility of the electrospun P(VDF-TrFE) mesh was demonstrated for applications concerning both sensors and actuators.

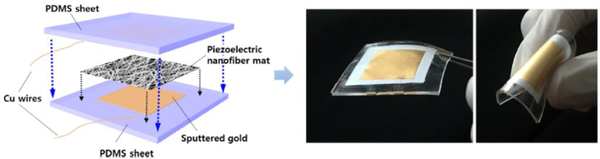

Park et al. [103] have proposed a bendable and stretchable P(VDF-TrFE) sensor able to identify the movement of the skin on the neck induced by the pulsed behavior of the carotid, with a resolution of about 1 mm. P(VDF-TrFE) nanofiber meshes were drowned into an elastomeric matrix of polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS), which ensured the bendability and stability of the apparatus (Figure 8). Besides single PVDF and its copolymer P(VDF-TrFE), the polymeric nanofiber may be developed with other nanostructures, such as salts [105], ceramic nanoparticles [106–108,118], nanowires [109] and carbon nanotubes [110], aiming at boosting the piezoelectric properties. Accordingly, Dhakras et al. [105] studied the effect induced by the addition of a hydrated salt, NiCl2.6H2O, to an electrospun PVDF on the piezoelectricity. By using hydrated salt, the authors found an increase of the polar β-phase of about 30% and the device exhibited also a remarkable enhancing of the dynamic response.

Figure 8.

The concept of a bendable piezoelectric sensor. Reproduced with permission. [103] Copyright 2016, American Chemical Society.

Lee et al. [106] reported an electrospun uniaxially-aligned matrix of PVDF nanofibers (average diameter of 200 nm) with BaTiO3 nanoparticles. It was noticed that the alignment enhanced remarkably the piezoelectricity. Moreover, the addition of the nanoparticles showed an increase in the output voltage when loaded with similar loads. In another attempt, the authors characterized (0.78Bi0.5Na0.5TiO3–0.22SrTiO3) (BNT-ST) ceramic particles loaded in P(VDF-TRFE) nanofibers with various BNT-ST concentrations (from 0 to 80 w%), highlighting that contents of 60 w% of BNT-ST had improved homogeneity and enhanced piezoelectric performances.[107]

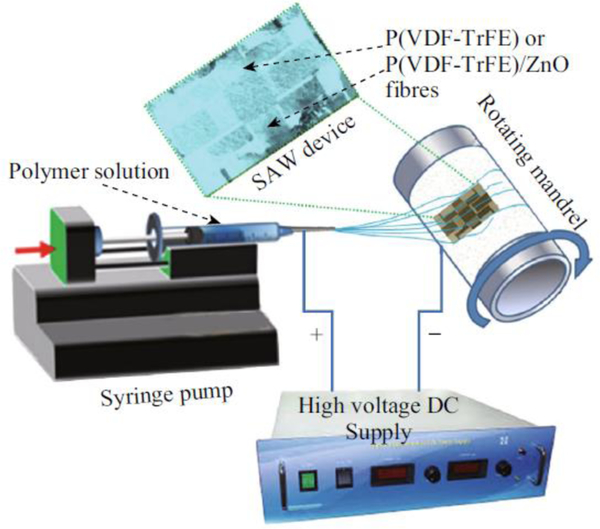

Augustine et al. [108] deposited ZnO loaded P(VDF-TrFE) nanofibers on LiNbO3 surface acoustic wave (SAW) device to identify and estimate the cell proliferation in cultures used as acoustic biosensors (Figure 9). Their results showed that the dispersion of ZnO NPs increased the β-phase in the electrospun biomaterials.

Figure 9.

Electrospinning process for P(VDF–TrFE) and P(VDF–TrFE)/ZnO nanocomposites on the SAW device. Reproduced with permission under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. [108]. Copyright 2019, Published by Springer.

Another example of force sensor application used silver nanowires (AgNWs) that were dispersed in PVDF nanofibers to enrich the β-phase. [109] The AgNWs showed a good dispersion due to the good matching between the polymeric chain and the AgNW surfaces. This interaction led to an increase of the polar β-phase during electrospinning, which was imputed to the local field-dipole close to the AgNW surfaces inducing TTT structure stabilization.

Composite of the PVDF and carbon nanotubes (MWCNTs) have been electrospun on a hollow cylindrical near-field electrospinning (HCNFES) without any further treatment. [110] The improvement on the mechanical properties and on the piezoelectric features of the PVDF/MWCNT nonwovens revealed that the connection between the PVDF structures and MWCNTs can make the nucleation of β-phase content easier. The PVDF nanofibers owing high crystallinity have been manufactured into a highly long-life bendable wearable transducer, to be exploited for long-term care. In a similar fashion, Lou et al. [111] used graphene oxide (rGO) inside P(VDF-TrFE) nanofibers to form a pressure transducer, which can be used to monitor human pulse waves and muscle movements. They demonstrated that a platform where several aligned sensors can be used as a device to finely mapping pressures on a surface. Some further studies have used the composition of different polymers to produce nanofibers for biosensors applications.[112–115] For instance, Manesh et al. [112] developed a transducer composed of nanofibers of PVDF and poly(aminophenyl boronic acid) (PAPBA) able to detect little concentrations of glucose (1 – 15 mM) in less than 6 s.

Sharma et al. [113] have developed pressure sensors by using P(VDF-TrFE) nanoweb fibers for endovascular applications validating them in vitro with dedicated physiological conditions. By using core–shell electrospun fibers, significant improvements in signal intensity gain were observed when compared to PVDF nanofibers and, also, nearly 40-fold higher sensitivity was achieved with respect to P(VDF-TrFE) thin-film structures. They reported that these flexible nanofibers have a great potential to fabricate more durable and bendable pressure sensors for innovative treatments in surgery (e.g., catheters).

Abreu et al. [114] reported the fabrication of P(VDF-TrFE) nanofibers embedding a water-soluble polyaniline mixed with polystyrene sulfonic acid (PANi-PSSA) owing fibers up to ~ 6 nm in diameter. Furthermore, by adding the conducting polymer PANi-PSSA the surface tension can be reduced and, at the same time, the charge density of the solution increased. This addition allowed the uniformity of the fabrication and bead-free nanofibers at lower P(VDF-TrFE) concentrations which are more desired for sensor applications. In another attempt,[115] P(VF2-TrFE)/poly(3,4-thylenedioxthiophene)-poly(styrene sulfonate), composite nanofibers were generated by electrospinning with fibers up to ~15 nm in diameter. The use of conducting PEDOT-PSS for the fabrication of slender PVF2-TrFE nanofibers, with reduced concentrations of polymeric chains, makes these constructs ideal candidates for supersensitive biosensor applications.

Liu et al. fabricated a wearable self-powered sensor based on a flexible piezoelectric PVDF nanogenerator and placed it in different parts of body to monitor human respiration, subtle muscle movement, and sound frequency (i.e., voice) recognition. A physiological signal recording system was used to measure the electrical signals of the sensor corresponded to the respiration signals with good reliability and feasibility. Results showed that this active sensor has promising applications in evaluating the pulmonary function, monitoring of respiratory, and detecting of gesture and vocal cord vibration for in the recovery of stroke patients who have suffered paralysis.[116]

The diversified and high performing biosensor applications of electrospun fibrous meshes all in all disclose the great versatility of piezopolymer-based nanoscale approaches for detecting human body signals and/or molecules of interest. Wearable and personal technologies have become emerging scenarios for monitoring patient’s vital functions and life style. Indeed, the ultimate purpose of wearable sensor devices is to connect via smartphone to domotics and telecommunication facilities for point-of-care medicine. Pervasive, miniaturized and smart sensing applications will thus represent the future of personalized healthcare and rehabilitation.

2.3. Energy harvesters

Implantable medical electronics (IMEs) can improve the quality of human life as diagnostic tools (e.g., heart beat, temperature monitoring, and blood pressure) for different pathologies affecting body organs, while supporting treatment (e.g., stimulation of brain and muscles). There is a strong interest to design smaller, lighter and more flexible IMEs to minimize the impact on human activities. One oft the most important features is flexibility such IMEs can be applied and the cyclic expansion–contraction movements of human body can be easily matched. Batteries are the most common power source for IMEs but they face some limitations such as achieving the maximum miniaturization and limited lifetime.[119]

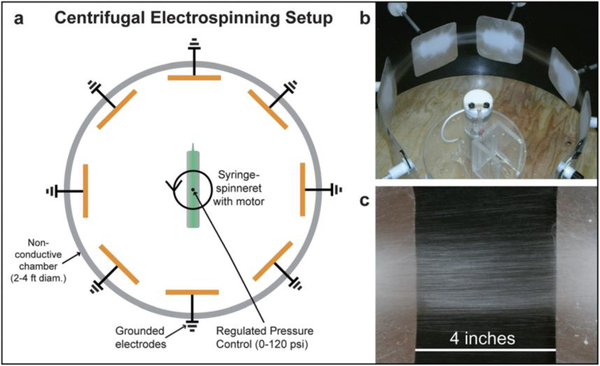

Harvesting energy from intrinsic human body motions has been intensely studied in the recent years: furthermore, self-powered implantable devices able to scavenge energy from different natural sources have been developed to convert biomechanical energy into other usable energies.[42] Piezoelectric polymers are the most widely used generators to collect human-related biomechanical energy. Unlike electrostatic and electromagnetic materials, piezoelectric materials permit simple architectures for energy harvesters to be obtained, which, in turn, are desirable for micro-electromechanical system (MEMS) electronic devices. Accordingly, different piezoelectric harvesters have been developed.[20,120] However, only few attempts have been made to develop bulky piezoelectric energy-harvesters for implantable energy sources, due to specific requirements to meet when coupled with the human organs (e.g., non-regular and rough surfaces).[121]

Recently, some advancement for harvesters based on piezoelectric nanofibers has significantly helped to fix such issues. To meet the requirements of wearable electronics, flexible and large surface area PVDF and P(VDF-TrFE) fibers were obtained via electrospinning technology (Table 3). These fiber-based electronics are capable of being woven into textiles and integrated into cloths to harvest energy during human activities.[19,122–129]

Table 3.

Comprehensive list of piezoelectric polymeric fibers fabricated by electrospinning techniques for energy harvesting applications.

| Polymer | Solvent | Additive | Comments | Fiber properties |

Ref. | Potential applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PVDF(Mw = 172,000) | DMF:acetone (4:6 v/v) | - | C = 16% (w/w), V = 40–60 kV, d = 16 cm, rotating speed = 100 rpm | Fiber diameter: 539 nm | [19] | Energy harvesting application |

| PVDF (Mw = 275,000) | DMF:acetone (4:6 v/v) | - | C = 16%, 20%, 26%, V=9, 15, 21 kV, d = 15 and 17 cm, flow rate = 1 ml h−1 | Fiber diameter: 230–810 nm | [122] | Energy harvesting application |

| PVDF | DMF:acetone (6:4 w/w) | - | C = 12%, 18%, 22% (w/w), V=15 kV, d = 20 cm, feed rate = 0.05 ml min−1. | Fiber diameter: 70– 400 nm | [123] | Energy generators and harvesters |

| PVDF (Mw = 46,000 g∙mol−1) | DMF:acetone | - | V = 18 kV, d = 15 cm, flow rate = 0.5 ml h−1, speed = 400 rpm | Fiber diameter: 124 nm | [124] | Energy harvesting application |

| PVDF | DMAC:acetone (4:6 v/v) | - | C = 16% (w/w), V = 30 kV, d = 12 cm, flow rate = 1.0 ml h−1 | PVDF | [125,126] | In vivo biomechanical energy harvesting and human motion monitoring |

| P(VDF-TrFE) (70:30) | DMF:acetone | - | P(VDF-TrFE):DMF:acetone 20:56:24 (w/w/w), V = 28 kV, d = 14 cm, flow rate = 150 μl h−1, speed= 4100 rpm | Fiber diameter: 509 nm | [12] | Energy harvesting devices |

| P(VDF–TrFE) (70:30) | DMF:acetone (3:7 v/v) | - | C = 20%, V= 25 kV, d = 25 cm, speed: 120 and 4300 rpm | Fiber diameter: 200−600 nm, coil diameter: 306 μm, yarn diameter: 175 μm, d33 = 37−48 pmV−1 | [128] | Energy harvesting application |

| P(VDF–TrFE) (70:30) | - | - | C = 20 w%, V = 28 kV, d = 20 cm, flow rate = 170 μl h−1, rotational speed: 5500 rpm | - | [129] | Energy harvesting application |

| P(VDF–TrFE) (70:30) | DMF:acetone (8:2) | - | Electrospinning + hot-pressing, C = 12% and 18% (w/w), V = 15 kV, d = 15 cm | Porous membranes with d33: 13.7 for C = 18% (w/w) and d33: 11.2 for C = 12% (w/w) | [127] | Energy harvesting application |

| PVDF | DMF:acetone (6:4 w/w) | Inorganic salts | C = 10% (w/w), V = 18 kV, d = 15 cm, flow rate = 1 ml h−1 | - | [130] | Energy-scavenging devices and portable sensors |

| PVDF | DMF | BaTiO3/PVDF 1:10 (w/w) | V = 15 kV, d = 10–15 cm, feeding rate = 0.5 ml h−1 | Fiber diameter: 110.4 ± 48.2 nm | [131] | Energy harvesting application |

| PVDF | DMF | BaTiO3 30% (w/w) of the total PVDF | C = 18% (w/w), V = 18 kV, d = 15 cm, flow rate= 0.12 ml min−1 | Fiber diameter of BaTiO3: 110 ± 40 nm, d33: 50 pmV−1 | [132] | Energy harvesting application |

| PVDF (Mw = 172,000) | DMF:acetone (8:2 w/w) | NaNbO3 (mass ratio 5:100) | C = 18% (w/w), V = 25 kV, d = 15 cm | - | [133] | Energy harvesting application |

| PVDF | DMSO | (Na0.5K0.5)NbO3 (NKN) 50wt% | V = 18 kV, d = 10 cm, flow rate: 1.5 ml h−1 | d33 after poiling:25 pC N−1 | [118] | Sensors in ubiquitous networks |

| P(VDF-TrFE) (70:30) | DMF:MEK (7:3 v/v) | 0 up to 20% ceramic content (w/w) | C = 15% (w/w), V = 20 and 35 kV, d = 10–30 cm, flow rate: 0.5–8.0 ml h−1 | Fiber diameter: 469 ± 136 nm | [134] | Energy harvesting application |

| PVDF (Mw = 495,000 g∙mol−1) | DMF | Cellulose nanocrystal PVDF/CN (C = 0%, 1%, 3%, 5% w/w) | C = 13% (w/w), V = 15 kV, d = 15 cm, flow rate = 1 ml h−1 | Average diameter: 0.439–0.559 μm, electrical conductivity: 5.82–60.17 μS | [135] | Energy harvester application |

| P(VDF-TrFE) 65:35 (w/w%) | DMF | MWNTs | V = 20 kV, d = 7 cm | Fiber diameter: 500 nm to 1 μm, of MWNTs | [136] | Smart fabric with applications in energy harvesting |

| PVDF (Mw = 534,000 g∙mol−1) | DMF:acetone (4:6) | ZonylUR as fluoro surfactant | C = 4%, 16%, 80% (w/w), V = 15 kV, d = 15 cm, flow rate = 0.5 ml h−1, rotating speed = 800 rpm | Fiber diameter: 84.6 ± 23.5 nm, β-phase fraction:80%, d33 = −33 pC N−1 | [137] | Energy generator |

| PVDF (Mw = 46,000) | DMF:acetone (70:30 v/v) | - | C = 20 % w/w, V = 15 kV, d = 15 cm, flow rate = 0.5 ml h−1, rotational speed = 180 rpm | Fiber diameter: 124 nm, electrical output: 1 V | [138] | Nano generator for designing flexible power source for smart and wearable electronic textiles applications |

| PVDF | DMF:acetone (6:4 w/w) | - | C = 10% (w/w), V = 20 kV, d: 15 cm, flow rate = 1 ml h−1 | - | [139] | Nano-generator |

| PVDF (Mw = 46,000 g.mol−1) | Acetone:DMF (4:6 v/v) | - | C = 26% (w/w), V=20 kV, d = 15 cm, flow rate = 0.5 ml h−1, rotating speed: 216 rpm | Fiber diameter: 812 ± 123 nm, output voltage: 0.028 V | [140] | Nano-generator |

| PVDF | DMF | - | - | Fiber diameter: 183 ± 37 nm, voltage output: 4 V | [141] | Nano-generator |

| PVDF (Mw = 534000) | DMF:acetone (3:7 v/v) | - | C = 15% (w/w), V = 12 kV, d = 15 cm, feed rate: 50 ml min−1 | - | [142] | Nano-generator for concurrently harvesting biomechanical and biochemical Energy |

| P(VDF-TrFE) (55:45) | DMF:acetone (45:55 w/w) | - | C = 15% (w/w), V = 10 kV, d = 10 cm, flow rate = 0.4 ml h−1. | - | [143] | Nano-generator |

| PVDF (Mw = 534,000 g∙mol−1) | DMF:acetone (4:6 v/v) | (ZnO, CNT, LiCl, PANI) | C = 16% (w/w), d = 20 cm, flow rate= 0.3 ml h−1, rotational speed: 180 rpm | Fiber diameter: 504.89 nm-39.69 μm | [144] | Nano-generator |

| PVDF (Mw = 534,000 g mol−1) | DMF:Acetone (6:4 v/v) | LiCl | C = 16% (w/w), V = 20 kV, d = 20 cm, flow rate = 0.3 ml h−1 | Coupling coefficient e31 = 189.68 and e33= 534.36 | [145] | Nano-generator |

| PVDF | - | - | Near-field electrospinning | Fiber diameter: 500 nm to 6.5 μm | [146] | Nano-generator |

| PVDF | - | - | Near-field electrospinning | Fiber diameter: 900 nm to 2.5 μm | [147] | Nano-generator |

| PVDF/PMLG (poly (γ-methyl L-glutamate)) | - | - | Near-field electrospinning V=10–16 kV, d= 1–2 mm | Output voltage: 0.019–0.185 V, energy conversion efficiency is 3.3% | [148] | Energy harvester |

| PVDF | DMF | - | Hollow cylindrical near-field electrospinning (HCNFES), C = 18% (w/w), V = 10–16 kV, d = 0.5 mm, rotational speed = 900 and 1900 rpm | 200 nm to 1.16 μm | [146] | Energy harvester |

[Mw = molecular weight; d = working distance; C = concentration (polymer/solvent), v = volume, w = weight, V = potential, NP = nanoparticles, rpm =rounds per minute; Dimethylformamide (DMF); Dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO)].

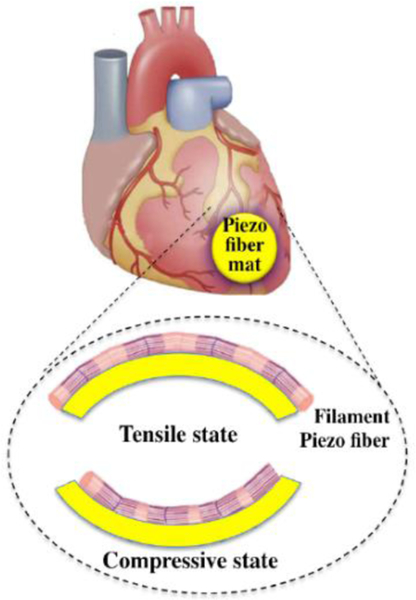

The effect of electrospinning parameters on the β-crystal phase of the PVDF structures and piezoelectric energy conversion of randomly-orientated PVDF nanofiber constructs have been investigated by different studies.[122,123] In general, PVDF fibers with a uniform and fine structure displayed a higher β-crystal phase content and better piezoelectric performances. Liu et al. [125,126] demonstrated a cell-pattern method on random and aligned PVDF nanofiber meshes for energy harvesting applications (Figure 10). This study showed that PVDF nanofibers, when aligned, could be shaped into a bendable monolayer by using a dedicated collector which ultimately enriched the piezoelectric β-content without any other post-processing. This device gave rise to a remarkable contractile response at cardiac level. It was reported that this cell-based energy harvester is versatile to several applications concerning biomechanical energy scavenging from, for instance, heartbeat, blood flow, muscle stretching, or irregular vibrations.

Figure 10.

Schematic of cell-dependent energy harvester including piezoelectric fiber mat applied on heart tissue. Reproduced with permission under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. [126]. Copyright 2019, Published by IOP Publishing.

Baniasadi et al. [12] quantitatively investigated how the annealing process affects the piezoelectric features of P(VDF-TrFE) nanofibers performing dedicated experimental tests on both meshes of nanofibers and on individual nanofibers.

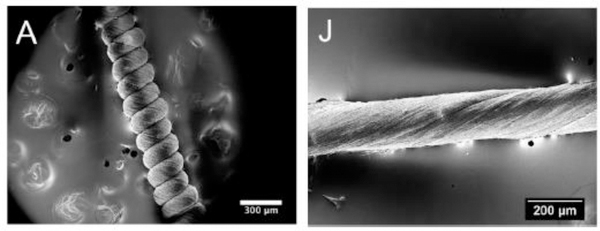

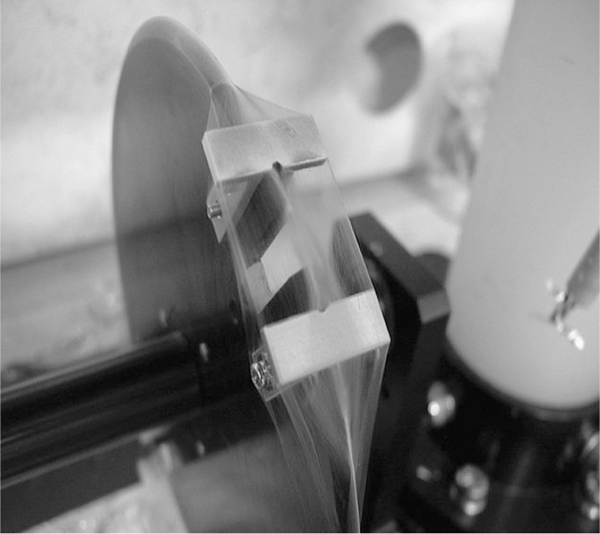

Results revealed that the annealing process enhances the stiffness (i.e., Young modulus) and the piezoelectric constants of single nanofibers up to 50% - 60%, which may have relevant consequences for these applications. Furthermore, they showed the fabrication of highly deformable piezoelectric P(VDF-TrFE) polymeric constructs through twisting electrospun P(VDF-TrFE) nanofibers (Figure 11), finally getting a noticeable boost of the mechanical properties. The application of twisted fibers in piezoelectric constructs has also been demonstrated in other publications.[128,129]

Figure 11.

Pictures from SEM of A) a coil and J) a twisted construct made of aligned nanofibers. Reproduced with permission. [128] Copyright 2015. American Chemical Society

He et al. [127] used electrospinning and subsequent hot pressing to produce P(VDF-TrFE) porous membranes for energy harvesting employment. Despite the high quantity of β-crystallites, the P(VDF-TrFE) electrospun membranes have not shown any piezoelectric behavior because of the random distribution of dipoles. As a matter of fact, the alignment of the dipoles in the crystallites, due a poling process, leads to the effective piezoelectricity. A recent study demonstrated that a hot pressed P(VDF-TrFE) electrospun membrane with beads revealed higher piezoelectric constant value (d33 = 24.7) if compared to bead-free membrane before hot-pressing (d33 = 3.2) which may be related to the easier poling of beads with respect to nanofibers. There have been several attempts to improve energy harvesting efficiency of PVDF and its copolymers nanofibers. In some previous work, some additives like inorganic salt,[130] inorganic piezoelectric nanoparticles and nanowires,[118,131–133] cellulose nanocrystals,[135] and multi-walled carbon nanotubes,[136] have been used into polymer solutions to form composites with attractive properties for energy harvesting devices.

Kato et al. [118] generated novel vibration energy harvester by using lead-free piezoelectric (Na0.5K0.5)NbO3 (NKN) ceramic particles dispersed in PVDF nanofibers. They demonstrated that this energy harvester can be used as power sources for transducers in omnipresent networks. The piezoelectric coefficient d33 of the harvester increased by using the highest amount of NKN particles (50%) and after corona poling which demonstrated that the particles were sufficiently polarized.

In one report, [130] twenty-six inorganic salts were doped into the PVDF nanofibers and their piezoelectric properties were studied to investigate the positive and negative influences of the salts on the electrospinning process. The obtained outcomes indicated that the optimum amount of unionized salt molecules with low dipole moments induced amorphous polymer phases to be transformed into a piezoelectric phase. The optimized piezoelectric voltage of a device made of FeCl3·6H2O doped nanofibers was 700% higher than that of a device with undoped nanofibers. Pereira et al. [134] have prepared electrospun PVDF, P(VDF-TrFE) and composite fibers of P(VDF-TrFE) with different sizes of BaTiO3 on top of an interdigitated circuit in order to investigate the effect of ceramic filler on the efficiency of the scavenging process. Another study showed that the best energy scavenging performances were reached for pure P(VDF-TrFE) fibers which had less mechanical stiffness if compared to the copolymers and the composites. An average piezo-potential of 100 mV could be measured for constructs made of fibers and BaTiO3 particles. This value is higher than the one achieved for the pure polymer matrix, along with a strong decrease in the piezo-potential by applying bigger fillers which acted as a defect and led to damping of the composite fibers. They have demonstrated that the reduction of the electromechanical efficiency affected by the intensification of the damping had a stronger implication with respect to the positive effect of the larger coupling coefficient of the fillers: the global result is a reduction of the power output.

Many studies have reported their flexible piezoelectric energy scavengers, i.e., nano-generators (PENGs), which have used lead-free piezoelectric nanofibers. [137,139–145,149] Due to their shape and their structural properties, PVDF nanofibers are excellent candidates as active building blocks in such nano-generators. Both single PVDF nanofibers and uniaxially aligned arrays can be used to produce these nano-generators. Single fibers can be directly positioned between pre-defined metal electrodes with high precision by near-field electrospinning.

Discussing the PVDF nano-generators, manufactured using conventional far-field electrospinning, Gheibi et al. [140] showed a direct manufacturing process for piezoelectric PVDF nanofiber meshes able to convert mechanical into electrical energy. In this case, the outputs are directly proportional to the technical features of the electronic devices used to store the electrical energy. They reported that many factors (e.g., polymer solution characteristics, shape of the collector) affect the fabrication of the electrospun constructs for wearable electronic textile applications. Fang et al. [141] developed nano-generators based on PVDF electrospun fibers, which achieved voltage output between 0.43 V and 6.3 V when subjected to vibrations with frequency content from 1 Hz to 10 Hz. Hansen et al. [142] published an energy scavenger, developed from the combination of a PVDF nano-generator and a biofuel cell, capable of collecting biomechanical energy from breathing or heartbeat. Moreover, they developed a compliant enzymatic biofuel cell to harvest energy from glucose/O2 in biofluids. Results showed 20 mV and 0.3 nA with a fixed strain rate of 1.67%/s.

Wang et al. [143] proposed a bendable triboelectric and piezoelectric coupling a nano-generator based on P(VDF-TrFE) nanofibers with excellent flexibility. The sandwich-shaped nano-generator delivered peak output voltage, energy power, and energy volume power density at 30 V, 9.74 μW, and 0.689 mW∙cm−3 when stressed with a load of 5 N, respectively. The nano-generator has itself several advantages such as bendability, thickness tuning, and double coupling mechanisms. Mokhtari et al. [144,145] have introduced a compliant and lightweight nano-generator device based on PVDF nanofibers containing various additives (ZnO, CNT, LiCl, PANi). Researchers studied the influence of each different addition to the matrix to maximize the mechanical and piezoelectric properties, highlighting that the LiCl is definitely the best option.

In some studies, authors have fabricated a piezoelectric fiber-based nano-generator and energy harvesters by using a direct-write technique via near-field electrospinning (NFES).[146–150] A direct-write and in situ poled PVDF nanofiber-based nano-generator was developed and validated for wearable applications[147]. Wide PVDF nanofiber arrays were manufactured on a compliant PVC substrate via NFES. When the piezoelectric device was coupled on a human finger, the electrical results reached 0.8 V and 30 nA under bending-releasing at ~ 45°C. Moreover, a hybrid energy cell-based on the nanofibers was also generated to scavenge mechanical energy. This device could provide a renewable energy source with the ability of energy collecting from human-based mechanical motion. In another study [148], the researchers developed a flexible PVDF/PMLG [poly (γ-methyl L-glutamate)] energy harvester with the power of 637.81 pW and an efficiency of 3.3% generated by NFES process. Results showed that NFES process had a positive influence on the piezoelectric and mechanical properties of composite fibers.

Liu et al. [146] published a modified hollow cylindrical near-field electrospinning (HCNFES) to make PVDF energy harvesters with outstanding output properties. The advantage of HCNFES relies on both the strong mechanical stress generated from the rotation of the collector and the high voltage that synergistically promoted the alignment of the dipoles along a single direction, thus assuring the PVDF fibers good piezoelectric properties. Repeated mechanical strain of 0.05% at 7 Hz on PVDF nonwoven fiber fabric with a strain of 0.05% at 7 Hz produced a 76 mV and 39 nA (maximum peaks).

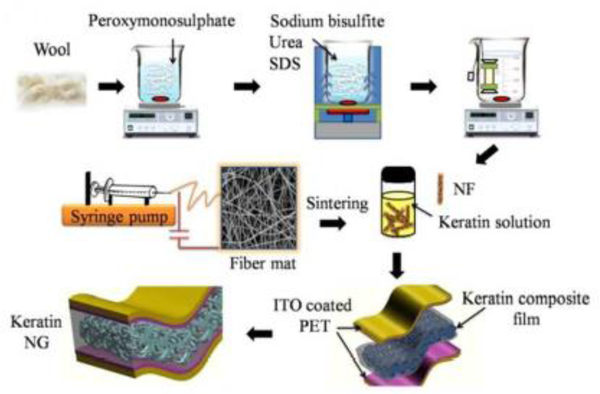

3. Bio-applications of electrospun ceramic-based piezo-fibers

The Restriction of Hazardous Substances Directive 2002/95/EC, namely, RoHS-1, adopted by the Member States in 2006, limited the use of some hazardous substances, such as lead, in electrical and electronic equipment. The life cycle assessment of lead-containing electronics is a subject of current studies, for example by the United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA).

In addition to the high-tech waste problem, RoHS reflects the contemporary research in biological toxicology assessing the long-term effects of low-level chemical exposure on population, which has been associated with neurological, developmental, and reproductive changes. Therefore, there is much concern about the use of lead-containing ceramics in biomedical applications. In fact, even if the lead atoms are fixed in the crystalline structure, the possibility of debris, contact toxicity and, most of all, occupational diseases for workers, are discouraging the practical use of such ceramics, which are entitled with the best piezoelectric properties. Lead-free piezoelectric ceramics can be processed in the form of fibers and also obtained as meshes by using specific technologies. This exciting possibility renders them versatile for many applications where membrane-shape devices are suitable to exploit target properties, such as filtration, support for catalysts, sensing, storage, or bioactive scaffolding. For their fully crystalline structure, ordered at atomic level, ceramics possess the best piezoelectric properties if compared with polymers. However, electrospun ceramic fibers are less known and for this reason their bio-application are still limited. A comprehensive panel of piezoelectric ceramic fibers fabricated by electrospinning, with their main employment in the biomedical field is presented in Table 4.

Table 4.

Overview of piezoelectric ceramic nanofibers for bio-applications.

| Ceramic | Precursor, polymer | Fabrication method | Fiber properties | Ref. | Potential applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BaTiO3 | Barium titanium, ethylhexano-propoxide, acetyl acetone, PVP | Sol-gel calcination in air at 500 °C and 700 °C for 3 h | Ribbon-like nanofibers ~200 nm in width and ~75 nm in thickness with grain sizes < 30 nm | [151] | Ferroelectric and piezoelectric sensors |