Abstract

The 2018 Pacific Region Indigenous Doctors Congress (PRIDoC) conference featured a student track curriculum that was developed by students at the John A. Burns School of Medicine. Activities were designed around the student track theme, ho‘oku‘ikahi, meaning “unity” or “unify,” as well as the overarching conference theme ‘Oi Ola Wai Honua meaning “life is better while the earth has water.” Following the conference, surveys were distributed among the trainees who had participated in the student track. The survey feedback was used to evaluate the student track curriculum, as well as its execution. Learning objectives developed for the Student Track were (1) to build formal professional networks, (2) to build a knowledge economy with shared knowledge among participants, and (3) to engage in cultural experiences. Analysis of qualitative data suggest that all learning objectives were satisfactorily fulfilled through planned conference activities. The data will be used to facilitate student tracks at future PRIDoC conferences. The student track at PRIDoC aims to establish and contribute to an ever-growing international network of indigenous students that will extend into professional practice.

Keywords: Hawaiian, End-of-Life

Introduction

The Pacific Region Indigenous Doctors Congress (PRIDoC) originated in 2002 with three indigenous physician organizations in the Pacific; ‘Ahahui o nā Kauka (the Association of Native Hawaiian Physicians); Te Ohu Rata o Aotearoa or Te ORA (the Maori Medical Practitioners Association); and the Australian Indigenous Doctors Association (AIDA). Since organizing, they have been joined by the Indigenous Physicians Association of Canada (IPAC), the Medical Association of Indigenous People of Taiwan (MAIPT), and the Association of American Indian Physicians (AAIP). The Pacific Basin Medical Association (PBMA) is invited to participate in the gatherings as an affiliate member.

PRIDoC holds a bi-annual conference that is hosted by one of the member organizations. The conference is attended by physicians, medical students, researchers, and other health professionals who exchange collective knowledge and discuss pertinent issues regarding indigenous health and wellness. PRIDoC provides a vehicle for indigenous Pacific physicians and medical students to network, discuss scientific and professional issues of mutual interest, and to share scientific advances with a focus on issues of medical and public health significance to the various peoples of the Pacific region.1 The conferences strive to help indigenous communities throughout the Pacific “thrive physically, emotionally, spiritually, socially, and culturally.”2

Nearly every PRIDoC conference since 2006 (with the exception of 2010 and 2012) has had a lālā haumāna (student track) that focuses on fostering relationships between indigenous medical students. The lālā haumāna is a collection of student-focused activities and organized discussions designed to enhance indigenous student networking, education, and development. It provides an avenue for participants to meet and network with other indigenous students and trainees from around the Pacific. Participants are afforded opportunities to foster friendships, to share experiences and knowledge, and to build relationships. All the activities are focused on enriching student learning and development, and emphasize the importance of indigenous student participation in advocating for indigenous health in ways that are appropriate to meet the needs and realities of the indigenous populations from which they belong.3 Furthermore, indigenous students need to navigate challenges such as integrating contemporary and traditional knowledge bases while functioning within dominant mainstream institutional cultures.3–6 Previous research demonstrated that students' positive attitudes toward health and research endeavors may be cultivated through interactions with cultural leaders, role models, and diverse peer groups within professional conference settings.6

The 2018 student track curriculum and learning objectives were established by members of Ka Lama Kukui (the indigenous medical student interest group at the University of Hawai‘i John A. Burns School of Medicine [UH JABSOM]), as well as members of the 2018 PRIDoC conference host organization, ‘Ahahui o nā Kauka. The benefit of a student-led conference includes a non-intimidating environment for professional networking as well as a program tailored to students' needs and topics of interest.7 Inclusion of cultural experiences of the host culture help to facilitate knowledge sharing, personal connection, and pride in culture that is beneficial to the well-being of the knowledge holders.8-11 The goal of establishing learning objectives and a curriculum for the student track is to provide resources for future PRIDoC conference organizers to create similar student tracks at their conferences.

2018 Student Track Background

The 2018 PRIDoC conference was hosted by ‘Ahahui o nā Kauka and held on Hawai‘i island. The theme for the conference was ‘Oi Ola Wai Hōnua, (life is better while the earth has water). The theme was chosen by Native Hawaiian cultural practitioner Pualani Kanahele to remind participants of the importance of caring for natural resources as well as individuals who function as resources for their people.2

The 2018 PRIDoC student track co-advisor, Dr. Marcus Iwane shared his thoughts regarding the theme; “This year's theme reminds us of how we, as indigenous kauka “physicians” and kauka haumāna (medical students,) need to take care of ourselves before we can care for others. Mālama ola (self-care / wellness) speaks of caring for our resources, including mind, body, and soul.”

The first two PRIDoC student tracks occurred in 2006 and 2008 followed by a hiatus until 2014. Due to the meaningful impact this experience has had on JABSOM students including three of this articles authors, Drs. Kong, Beckwith and Witten, the 2018 PRIDoC conference organizers invited prior student track participants to work with medical students in Ka Lama Kukui to create the 2018 curriculum. Having taken part in the first student track in New Zealand, in 2006, Dr. Kehau Kong was chosen as a co-advisor for the PRIDoC 2018 student track.

In 2007, after being inspired at PRIDoC 2006, then medical students, Dr. Iwane and Dr. Kong founded Ka Lama Kukui as a special interest group for indigenous medical students and like-minded fellow medical students to gather and share ideas. Since its inception, Ka Lama Kukui has facilitated opportunities for indigenous medical students and those interested in indigenous health to attend PRIDoC and to benefit from the fellowship and networking provided through the student track.

The theme for the 2018 PRIDoC student track was ho‘oku‘ikahi “to unite or unify.” Dr. Iwane remarks that ho‘oku‘ikahi “speaks of bringing indigenous physicians, providers, and students together to promote health and wellness and discuss indigenous issues in medicine. The PRIDoC conference gives us the opportunity to build relationships and unify together to help uplift the health of our people by discussing medicine in a culturally-relevant way.”

Methods

Curriculum Development

The Student Track curriculum was developed by medical student members of Ka Lama Kukui, and past participants in PRIDoC student tracks. The 2018 PRIDoC student track co-advisors held multiple meetings leading up to the 2018 PRIDoC conference with the goal of establishing a purpose, learning objectives and the curriculum for the 2018 conference.

The purpose of the 2018 student track was to enhance student and trainee learning, development, and leadership in the indigenous health community; to provide a space for students to foster professional relationships; to build and contribute to a fund of knowledge; and to engage in cultural experiences with the visions of a diverse group of indigenous leaders who strive to improve the health and well-being of indigenous peoples. The overall goal was to inspire students and trainees to broaden their understanding of indigenous health and to integrate the knowledge and skills gained at the conference into their educational experiences and clinical practices within their home indigenous communities.

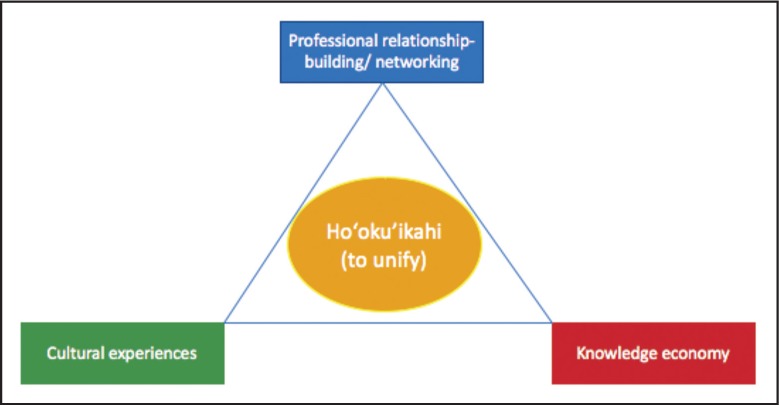

The student track curriculum was formulated around three learning objectives (shown in Figure 1): (1) to build formal professional networks, (2) to build a knowledge economy with shared knowledge among participants, and (3) to engage in cultural experiences. In addressing and exploring these learning objectives, the intent was that the student track would ho‘oku‘ikahi (unify) the different groups of indigenous medical students and trainees with each other as well as with their respective communities. The planning team designed specific elements of the curriculum to address each learning objective. The first learning objective would be met with activities centered around student engagement and included opportunities to foster professional relationships in a safe, professional environment where indigenous values and ways of knowing were discussed, honored, and respected. Opportunities for participants to discuss indigenous health as a group addressed the second learning objective. Activities focused around the third learning objective would engage participants in various cultural practices, protocols, and processes in regard to the Native Hawaiian, hosting, indigenous culture for the 2018 PRIDoC conference. Participants would be asked to demonstrate traditional practices, protocols, and processes during the conference, and to identify how these things might enhance clinical competence when working in indigenous health.

Social and cultural activities included casual visits to Wailuku River State Park and the Hilo Farmers Market allowing students time to explore on their own, while organized trips to Hale o Lono Fishpond, Makali‘i at Kawaihae, and Maunakea were designed to provide a more structured learning experience. Although not exhaustive, the selected sites and activities showcased a variety of cultural experiences important to Hawai‘i. Specifically, these sites were chosen to demonstrate different land and water resources throughout the island. Activities included in the PRIDoC 2018 student tract curriculum are listed in Table 1, whereas Table 2 lists activities as they relate to the learning objectives.

Table 1.

2018 PRIDoC Student Track Curriculum Activities

| Student Specific Social Activities |

|

| PRIDoC Conference Activities |

|

| Traditional Native Hawaiian Cultural Activities |

|

| Breakout Sessions |

|

| Mentoring |

|

Table 2.

2018 PRIDoC Student Track Curriculum Learning Objectives and Corresponding Activities.

| Student Social Activities | PRIDoC conference Activities | Traditional Cultural Practices | Break out sessions | Mentorship | |

| Objective 1 – To build formal professional networks | |||||

| Objective 1a: to engage in opportunities that foster professional relationships | X | X | X | X | |

| Objective 1b: To contribute to a safe, professional environment where indigenous health values and ways of knowing were valued and respected. | X | X | |||

| Objective 1c: To engage in opportunities to identify appropriate mentors/mentees and attributes for future professional relationships. | X | X | X | ||

| Objective 2- To build a knowledge economy | |||||

| Objective 2a: To engage in opportunities to discuss indigenous health | X | X | |||

| Objective 2b: To engage and contribute to activities that support an indigenous health knowledge economy | X | X | |||

| Objective 3- To engage in cultural experiences | |||||

| Objective 3a: Identify how cultural practices, protocols, & processes can enhance clinical competence when working in indigenous health. | X | X | X | ||

| Objective 3b: To demonstrate an ability to enact appropriate cultural practices, protocols, and processes when required during the conference. | X | X | |||

In order to evaluate the curriculum activities an evaluation tool was distributed to all student track participants, in both electronic and paper forms, at the end of the conference, as seen in Appendix 1. Paper copies of the form were collected at the conference and electronic forms were collected through December 2018. Student demographic information was collected and the curriculum was evaluated using Likert rating scales to assess the applicability of the activities to their training programs, and qualitative feedback to assess the overall program. Survey data was deidentified, digitized and analyzed to determine if the participants viewed the student track as a meaningful and worthwhile endeavor. Thematic analysis of the qualitative responses was done by four individuals on the 2018 PRIDoC student track leadership team. Once individuals identified primary or prominent themes from the open-ended or qualitative feedback items, the group was able to reach consensus over the primary themes.

Results

A total of 99 students and trainees participated in the student track including 39 residents, 55 medical students, and 5 nonmedical university students. Due to participants being from both American and British style academic settings, all those trainees in post medical school training programs (eg, registrars and above in the British system) were grouped together under the American graduate medical education term “resident.” Thirty-four percent of participants in the student track completed the survey. Of the 34 completed surveys, 11 were completed by residents, 21 by medical students, and 2 by non-medical university students. Of the 55 surveys distributed to the medical students, 21, 38.2%, completed surveys were returned.

Quantitative Analysis: Learning Objectives and Participant Impressions

The questions asked in the evaluation tool aimed to assess if the learning objectives were supported through student track activities. Based on the survey, the majority of respondents either agreed or strongly agreed with the first 8 questions in the survey instrument, as seen in Table 3; no respondents strongly disagreed with any of the first 8 questions. The majority of respondents also felt that their participation in the student track was applicable to their medical training and that they would recommend it to students at future PRIDoC conferences, as seen in Table 4. None of the participants felt that the student track was too short; although 20% felt it was too long, as seen in Table 5.

Table 3.

Post-Conference Survey Results Evaluating Fulfillment of Curriculum Learning Oobjectives. *Frequency of Response Followed by the Percentage (%) of the 30 Participants Who Provided an Answer for the Following Items.

| Strongly Agree | Agree | Neutral | Disagree | Strongly Disagree | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I was provided the opportunity to: | Frequency n = 30 (%) * | ||||

| Engage in opportunities that foster professional relationships | 15 (50%) | 11 (37%) | 3 (10%) | 1 (3%) | 0 (0%) |

| Contribute to a safe, professional environment where indigenous health paradigms are normed | 23 (77%) | 6 (20%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (3%) | 0 (0%) |

| Engage in opportunities to identify appropriate mentors/mentees and attributes for future professional relationships | 14 (47%) 8 (27%) 7 (23%) 1 (3%) 0 (0%) | ||||

| Engage in opportunities to discuss indigenous health | 21 (70%) | 6 (20%) | 2 (7%) | 1 (3%) | 0 (0%) |

| Engage and contribute to activities that support an indigenous health knowledge economy | 19 (63%) | 9 (30%) | 1 (3%) | 1 (3%) | 0 (0%) |

| Engage in cultural opportunities, including cultural practices, protocols, and processes with a special focus on Native Hawaiian culture | 25 (83%) | 5 (17%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| Demonstrate an ability to enact appropriate cultural practices, protocols, and processes when required during the conference | 19 (63%) | 10 (33%) | 1 (3%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| Identify how cultural practices, protocols, and processes can enhance clinical competence when working in indigenous health | 18 (60%) | 11 (37%) | 1 (3%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

Table 4.

Post-Conference Survey Results Evaluating Execution and Relevance of the Student Track.

| Strongly Agree | Agree | Neutral | Disagree | Strongly Disagree | |

| Frequency, n = 30 (%) * | |||||

| I would recommend the student track to other students in future years | 20 (67%) | 7 (23%) | 2 (7%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (3%) |

| The student track was applicable to my medical training | 13 (44%) | 9 (30%) | 7 (23%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (3%) |

Table 5.

Post-Conference Survey Results Evaluating the Length of Student Track Activities.

| Too Short | Appropriate Length | Too Long | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Frequency, n = 30 (%) * | |||

| The student track activities were: | 0 (0%) | 24 (80%) | 6 (20%) |

Qualitative Analysis:

Thematic analysis of the results revealed three major themes; professional networking, unity and camaraderie, and cultural engagement.

1. Professional Networking

Qualitative reflections from the students highlighted their appreciation for the opportunities for participants to expand their social, clinical, and professional networks. Participants described enjoying being able to build connections with other indigenous students in the medical field. Many participants also expressed gratitude toward Hawaii Permanente Medical Group (HPMG) for sponsoring the welcome dinner for students and providing a casual meet and greet with Native Hawaiian HPMG providers throughout the state. One respondent stated, “I appreciated connecting with other indigenous medical students from around the world. I developed new friendships that I plan to take advantage of when I plan to travel around to various indigenous communities.”

2. Unity and Camaraderie

Participant reflections described feelings of unity and camaraderie that resulted in connecting with other students and trainees from indigenous backgrounds. The gathering allowed for the sharing of ideas and experiences concerning diversity in the medical field, advocacy for indigenous health, and reflecting on indigenous identity in one's practice. Although numerous indigenous groups from across the Pacific Basin were represented, participants were able to find common ground through shared experiences as indigenous people with great pride in their culture.

One participant detailed, “One thing I appreciated most [about the student track] was the camaraderie with other students from indigenous cultures and hearing about their personal experiences that may have been similar to mine.”

Another stated, “I enjoyed being able to facilitate and participate in discussions on indigenous issues and appreciated those who shared specific challenges they have faced thus far in their careers. I valued being able to brainstorm solutions and hear from the perspective of other students with an indigenous background.”

3. Cultural Engagement

The most prominent theme was an appreciation for other indigenous cultures and for the opportunity to learn about the Hawaiian culture through various student track activities. The student track provided an experiential learning opportunity to learn about and engage in Hawaiian cultural practices and protocols. Some of these activities included learning ‘oli (chants), hula (traditional dance), hei (string figures), and how to prepare ho‘okupu (tribute) and makana (gifts). Additionally, participants visited several sites that taught about different cultural practices. One of these sites was Hale o Lono Fishpond in Honohononui, Keaukaha where students and trainees participated in a servicelearning project. Many of the survey responses included positive feedback regarding the Hale o Lono activity and described the workday as a rewarding and unforgettable experience.

A participant response stated, “The fishpond day was amazing. It was both interesting and rewarding to do something different and to help out the community, particularly the indigenous people. Awesome!”

Another participant wrote, “I loved all of the cultural learning. The fishponds were my favourite experience, being a part of working Hawaiian lands was an honour, I am grateful to have been invited to restore the fishponds.”

In another student track activity, participants were also able to sail on Hawai‘i Island's voyaging canoe, Makali.i. In addition to experiencing sailing on the Makali‘i in Kawaihae, participants were also taught how to tie knots and how to preserve food for voyages. A participant remarked that “One of the most valuable experiences was getting to sail on the voyaging canoe and learn from prominent crew members. This experience has made me appreciate indigenous knowledge and our ancestor's ingenuity.”

Finally, participants were asked to provide suggestions on how the student track could be improved for future PRIDoC conferences. Answers ranged from asking for more integration with the main conference as well as increasing the time available to network with senior health care providers in attendance.

Discussion

The responses received from the post-conference student surveys were overwhelmingly positive and contained valuable feedback that will be considered for the improvement of future PRIDoC conference student tracks. The quantitative data collected indicated that the majority of respondents felt that the learning outcomes were addressed through various activities throughout the conference. Furthermore, narrative feedback expressed success in providing networking opportunities and exposure to the Hawaiian culture through experiential learning.

Much of the success of the 2018 PRIDoC conference student track stemmed from the opportunities for professional networking with other indigenous students and students interested in indigenous health. Connecting with other indigenous students and trainees that are incorporating their culture into their profession as well as others who are interested in promoting indigenous health allows for the development of both personal and professional relationships that may be beneficial in the future. Through a shared background and interest in indigenous health, attendees could facilitate meaningful conversations around indigenous topics related to navigating the healthcare field.

An overarching theme of appreciation for the host culture was emphasized by the participants. Having a cultural and historical understanding of place helped to orient students to their surroundings. However, having a very dense schedule with little to no passing time between activities presented some challenges of time management throughout the 2018 PRIDoC conference. Although time allotted for each activity in the student track was optimized to fit as many quality experiences as possible, the lack of adequate time to transition activities made students feel rushed to move to the next activity. Despite this, leadership and participants adapted well to a flexible schedule that allowed students to partake in a wide variety of experiences.

When considering the suggestions for improvement of the student track for future PRIDoC conferences, we looked at the issues around increasing integration with the main conference as well as dedicating more time to network with the physicians and other senior health care providers in attendance. Aside from plenary speakers and evening events, the student track activities occurred at the same time as other scheduled events of the main conference. Although student track participants were not restricted from participating in main conference events, it may have been unclear if they were required to attend all student track activities. Participants also expressed the desire for clinical skills workshops and exposure to more specialty medicine vs. primary care, which is the general focus of the PRIDoC conference. Additionally, participants requested more information on career opportunities for those interested in focusing on indigenous health. Finally, participants wished for more leisure time to explore the host community independently.

Limitations

This study is not without limitations. Limitations of the study included the number of completed and returned surveys included in the analysis. Furthermore, four of the surveys that were returned only provided qualitative feedback through comments and an additional two surveys were returned with only demographic information completed and, thus, were not included in the analysis. The study was also limited since there was no pre-survey to collect data regarding participants' knowledge and attitudes of professional networks, shared fund of knowledge, and cultural experience prior to the conference.

Conclusion

The 2018 PRIDoC conference student track overall appears to have been a successful venture with the curriculum learning objectives fulfilled through various programming. The student track at PRIDoC was created to foster relationships between indigenous medical students and to promote student-focused activities and organized discussions with the mission to enhance student and trainee learning, development, and leadership in the indigenous health community by providing a space to foster professional networks, contribute to a shared fund of knowledge, and to engage in cultural experiences. It is the authors' intention that this report will serve as a tool for future PRIDoC student track organizers to perpetuate the vision of growing a diverse group of indigenous leaders in their respective communities who strive to improve the health and well-being of indigenous people. Through continuous progress and change, the student track at PRIDoC conferences will continue to establish and contribute to an ever-growing international network of indigenous students that will extend into professional practice.

Future Directions

Having considered both the quantitative and qualitative feedback from student track evaluation, the following should be considered for inclusion in future PRIDoC conference student tracks:

Indigenous space for health professional students to discuss shared issues concerning the well-being of the many indigenous communities in the Pacific Basin;

Education about the traditions, protocol, and practices of the host culture: this may include but is not limited to chant, dance, song, art, food, and other traditional practices;

Exploration of other cultures represented by the student population through a cultural exchange;

Lectures, skills-workshops, or other activities that enrich conference material: this may include discussion surrounding indigenous health in practice and career development;

Service-learning or volunteer activity that will directly benefit the community in which PRIDoC is being hosted (eg,fishpond workday, beach clean-up, blood drive);

Formal and informal opportunities to network with other students as well as physicians, researchers, and other health professionals in attendance at PRIDoC; and

Pre- and post-conference evaluations to record the progress of the student track and to provide both quantitative and qualitative feedback: feedback should be compiled into a formal report and shared with participants as well as future PRIDoC conference student track planning leadership.

Figure 1.

Interconnectedness of the 2018 PRIDoC Student Track Goals as Related to the Theme of ho‘oku‘ikahi “To Unify”

Acknowledgements

Marcus Iwane MD, Natalie Kehau Kong MD, and Vanessa Wong MD, for help with developing the PRIDoC 2018 student track curriculum. Thank you to Hale o Lono and Na Kalai Wa‘a for hosting our students during cultural learning and service-learning activities. Kumu Paul Neves and Halau Ha‘a o Kea for teaching our students a hula as well as makana preparation. Papa Ola Lokahi for financial assistance with student track swag. Finally, a special thanks to Hawaii Permanente Medical Group (HPMG) for financial support of student track activities.

Abbreviations

- AAIP

Association of American Indian Physicians

- AIDA

Australian Indigenous Doctors Association

- HPMG

Hawai‘i Permanente Medical Group

- IPAC

Indigenous Physicians Association of Canada

- MAIPT

Medical Association of Indigenous People of Taiwan

- PBMA

Pacific Basin Medical Association

- PRIDoC

Pacific Region Indigenous Doctors Conference

- Te ORA

Maori Medical Practitioners Association

- UH JABSOM

University of Hawai‘i John A. Burns School of Medicine

Contributor Information

Nina Leialoha Beckwith, University Health Partners of Hawaii, Family Medicine Residency Program, Honolulu, HI (NLB).

Ashley Morisako, Kaiser Permanente Internal Medicine Residency Program, Honolulu, HI (AM).

Conflict of Interest

None of the authors identify any conflict of interest.

Appendix 1

2018 PRIDoC conference student track survey instrument. Qualitative Questions

What did you most appreciate or enjoy about the student track?

Is there anything you wish you had more exposure to during the student track?

Is there anything that you wish you had more exposure to?

Are there other areas for improvement?

References

- 1.Leslie HY. Pacific region indigenous doctors' congress 2002. Pacific Health Dialog. 2002;9((1)):115–118. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Carpenter DL, Aluli NE. Pacific region indigenous doctors congress 2018. PRIDOC 2018. 2018 Pridoc2018.org/information. Accessed October 2018. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chino M, DeBruyn L. Building true capacity: indigenous models for indigenous communities. Am J Public Health. 2006;96((4)):596–599. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.053801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Smith LT. New York, NY: Zed Books; 1999. Decolonizing methodologies: research and indigenous peoples. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hill SM. Ottawa: Indigenous Physicians Association of Canada and The Association of Faculties of Medicine of Canada; 2007. Best Practices to Recruit Mature Aboriginal Students to Medicine. [Google Scholar]

- 6.James RD, West KM, Madrid TM. Launching Native health leaders: reducing mistrust of research through student peer mentorship. Am J Public Health. 2013;103((12)):2215–2219. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Funston G. The promotion of academic medicine through student-led initiatives. Int J of Med Edu. 2015;6:155–157. doi: 10.5116/ijme.563a.5e29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kamaka ML, Paloma DSL, Maskarinec GG. Recommendations for medical training: a Native Hawaiian patient perspective. Hawaii Med J. 2011;70((11, Suppl 2)):20–24. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kamaka ML. Designing a cultural competency curriculum: asking the stakeholders. Hawaii Med J. 2010;69((6 Suppl 3)):31–34. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Benyei P, Arreola G, Reyes-García V. Storing and sharing: A review of indigenous and local knowledge conservation initiatives. Ambio. 2019;10:1–13. doi: 10.1007/s13280-019-01153-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kumahai AK, Lypson ML. Beyond cultural competence: critical consciousness, social justice, and multicultural education. Academic Med. 2009;84((6)):782–787. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181a42398. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181a42398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]