Abstract

Education and health are vital for children to thrive, especially for those from rural and disparate communities. For Native Hawaiians, the indigenous people of the State of Hawai‘i, lokahi (balance) frames the concept of ola (health), consisting of physical, emotional, and spiritual health. The foundation of ola is embedded in the cultural values — kupuna (ancestors), ‘āina (land), environment, and ‘ohana (family). Unfortunately, since westernization, Native Hawaiians have significant health disparities that begin in early childhood and often continue throughout their lifetime. Native Hawaiians also have a history of educational disparities, such as lower high school an college graduation rates compared to other ethnic groups. Social and economic determinants, such as poverty, homelessness, and drug addiction, often contribute to these educational disparities. In rural O‘ahu, the Waianae Coast Comprehensive Health Center recently established two school-based health centers at the community's high and intermediate schools to improve student access to comprehensive health services. Recognizing the need to improve student health literacy and address specific health issues impacting the community and students, two health educators were added to the school-based health team. This article describes: 1) the initial steps taken by the health educators to engage and empower students as a means to assess their needs, interests and facilitate student lokahi, ola, and wellness and; 2) the results of this initial needs assessment.

Keywords: Community Health, Community Health Centers, Culture, Hawai‘i Public School, Health, Health Education, Indigenous Health, Indigenous Public Health, Public Health, Native Hawaiian, Native Hawaiian Health, Rural Health, Rural Community Health, School Based Health Centers, Student Driven, Student Health, Student Health Needs, Waianae Coast Comprehensive Health Center

Introduction

Optimal health is essential for children to succeed academically. Healthy children are better learners and do better on standardized tests.1-3 For many children, however, especially those from impoverished and/or rural communities, optimal health and academic achievement are difficult to attain. In Hawai‘i, children from these communities experience higher rates of chronic disease like obesity.4 They also have higher rates of high-risk behaviors such as smoking and drug use, as well as high rates of academic underachievement.5 This includes Native Hawaiians who experience significant health disparities that begin in early childhood and often continue throughout their lifetime. For example, obesity in Native Hawaiians often begins very early in childhood and increases the risk for chronic diseases such as diabetes and cardiovascular disease.4,6 Native Hawaiian children also have a history of educational disparities, such as lower high school and college graduation rates compared to other ethnic groups.5

For Native Hawaiians, lōkahi (balance) frames the concept of ola (health), including physical, emotional, and spiritual health. The foundation of ola is embedded in cultural values including kupuna (ancestors), ‘āina (land), environment, and ‘ohana (family).7 Unfortunately, for many Native Hawaiian children and adolescents, social and economic determinants of health, including poverty and poor housing,9,10 continue the cycle of school failure and poor health making lōkahi and ola difficult to achieve.

School-based health centers (SBHC) can reduce barriers to health care by providing health services to students, including those who might otherwise not seek or receive health services.11,12 This is especially true for adolescents, who often avoid conventional clinic-based services. SBHC have been shown to improve access to healthcare.13 They have also been shown to improve school attendance in those who utilize the services, especially those accessing mental health services.12 Thus, SBHCs may be an important component in addressing youth health disparities, especially for children and adolescents from rural and underserved communities.

Unlike many states, Hawai‘i has few SBHCs.13 However, in 2016, at the request of the Hawai‘i Department of Education (DOE) and community members, the Waianae Coast Comprehensive Health Center (WCCHC) established two SBHCs at Wai‘anae High School (WHS) and Wai‘anae Intermediate School (WIS). In Fall 2018, again, at the request of the community and the DOE, WCCHC opened a SBHC at Nānākuli High and Intermediate School. The Empowering ‘Ōpio (next generation) Project aims to improve healthcare access and health literacy as a means to enhance student lōkahi. The objective of this article is to describe the initial steps taken by WCCHC SBHC team, to engage and empower high school students to assess their health needs and community interests.

The Wai‘anae Community and the WCCHC School Based Health Centers

The Wai‘anae Coast is located on the rural, northwest side of O‘ahu and is composed of eight ahupua‘a (land divisions). It is home to one of the largest populations of Native Hawaiians, many of whom have lived on the coast for generations. Unfortunately, community members have some of Hawai‘i's highest levels of poverty, homelessness, unemployment, and crime.14 Health statistics are poor, with high levels of chronic physical and mental health conditions beginning early in life.15,16 WCCHC is Hawai‘i's largest federally qualified community health center and has served Wai‘anae communities for over 45 years. In 2017, WCCHC served 37,204 patients, the majority Native Hawaiians (44%) and living at, or below, the poverty level (65%).

The WCCHC SBHCs serve all students, regardless of insurance status, providing comprehensive primary care, acute care, health education, and behavioral health services. Students are seen at SBHCs once parental consent is obtained. Visit summaries are sent to the adolescent's primary care provider after every visit. Since opening in 2016, healthcare providers at the three SBHCs have cared for over 2,795 students; 95% of them were able to return to class after treatment.

Soon after opening, the school principals, together with the WCCHC SBHC team, recognized the need to address specific health issues (ex: prescription drug abuse) impacting the community and the school. They also recognized the need to improve student health literacy and health-seeking behavior. While school health education courses may address these needs, in Hawai‘i, the DOE health education requirements are minimal. Students are not required to take health education courses in intermediate school (7th and 8th grade) and only need one semester of a health education course to graduate from high school (9–12th grade).17 To address these needs, in September 2017, the WCCHC SBHC added two health educators to its team, both of whom are Native Hawaiian, from the community, and graduates of Wai‘anae Coast public schools and the University of Hawai‘i at Manoa. The health educators' central focus is the ‘ōpio or the children. Both educators have training and experience using community participatory methods in research and health programming. These methods apply a range of strategies to facilitate active participation by community members to characterize problems and explore potential solutions. Participatory methods have been found to empower participants and are a method to effectively address health disparities.18 The WCCHC SBHC health educators sought to facilitate student lōkahi, health, and wellness by understanding the needs of students, providing health education on a broad array of topics, as well as connecting students to services and each other.18

Methods

To begin the Empowering ‘Ōpio Project, the two WCCHC SBHC health educators explored participatory strategies with stakeholders including students, school principals, school administration, teachers and staff, along with the SBHC team. Participatory strategies that empower youth to think critically, solve problems and become socially active in issues that they are concerned about, have been shown to promote positive health behaviors and community action.18 The health educators were then invited by some teachers, including math and health education teachers, to use regular class time to meet with students.

With the goal of empowering the students, the health educators held sessions with the students that included a formal presentation on WCCHC SBHC services and community health. A “talk story” followed the formal presentations where the health educators shared their own personal stories about growing up in the community and the challenges they faced. The students were invited to ask questions and talk about their own concerns and challenges. The presentation concluded with a voluntary, confidential, open-ended paper survey that asked the students to describe the meaning of community, what it means to be from the Wai‘anae Coast, and the students’ needs and concerns about health issues for themselves and ‘ohana. To analyze the results, the health educators extracted the common themes then met with the SBHC team to reach consensus on the main themes. The health educators then reviewed the surveys to identify quotes and subthemes, or topics that cut across several main themes.

Results

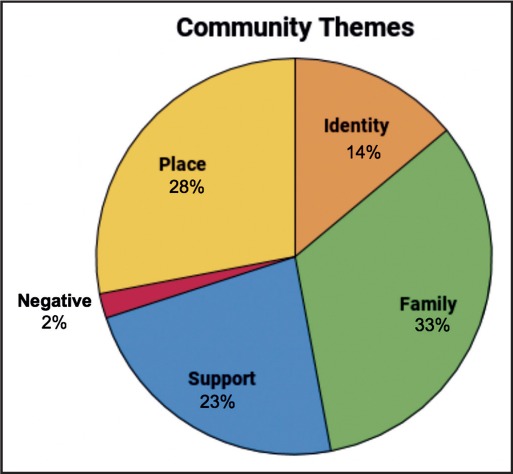

Health educators held eight sessions at WHS and WIS with 133 students; all students present on the day of the class presentation opted to complete the voluntary, open-ended paper survey. However, survey questions were not mandatory to answer, thus the number (n) answering each question varied. Main themes related to the meaning of community included family, place, support, identity, and negativity. (see Figure 1). Sub themes related to the meaning of community were defined as topics that crossed over several of the main themes. The sub theme topics included kindness, peace, responsibility, knowing and respecting each other, pride, strength, humility, resilience, helpfulness, and Native Hawaiian cultural values. Selected quotes for each main theme are provided in Table 1.

Figure 1.

Community Themes Iidentified by Students (N = 129)

Table 1.

Community Theme Quotes (As Written by Students)

| Identity Quotes | |

| “To be from Waianae means we are strong, we don't give up… What community means to me is people who are strong together.” | “We have strong pride for who we our. Stronghold is our Native Hawaiian culture.” |

| Place Quotes | |

| “Its community is my home. Being from Waianae is something to (be) proud about. Its where my roots lie. And people in Waianae always support the Waianae high school.” | “I feel that it means that you have had a privilege to be able to be in one of the most beautiful places for education.” |

| Family Quotes | |

| “What community means to me is when I hear Waianae I want to hear positive things and we also represent Waianae. And we in Waianae are all family.” | “Community to me is the whole of waianae coast. I think as people of “waianae” we should strive to be better, is your ohana, friends, aloha, and culture.” |

| Support Quotes | |

| “To be from Waianae means to be strong. It's not all seasons. We're all nice and help each other out. We aren't druggies and we don't all have criminal records.” | “Community means to me is the people you live around the area your around is your kuliana, where we live helping each other out and move forward to help your peers and elders and everyone working together as ohana.” |

| Negative Quotes | |

| “It means that everyone has stereotypes against us. Being from Waianae means its really hard, a lot of struggling you have to be tough, because there is a lot of negative in Waianae.” | “It means that I always have to try my best because there's people out there who think we aren't good enough.” |

Family: Students strongly value the connection within their ‘ohana and the aloha they have for one another between the Wai‘anae Coast communities.

Place: For students, the Wai‘anae Coast is more than just a physical location or a community of families; it provides students with a sense of place, a sense of connection to their roots, and a generational connection to the community that is profoundly important to them.

Support: Students value working together to support and improve their ‘ohana, and their community.

Identity: Thoughts about cultural and community identity were most frequently expressed by the students. The students expressed strong cultural identity and their passion about being from Wai‘anae. They conveyed the importance of supporting, influencing, and motivating one another to surpass struggles they may face.

Negative: Negative themes were expressed by a few students. These included “too many bad things”, “we're stereotyped”, and “struggling”. Students often felt they were “being judged,” and expressed the need to build a hard exterior. Some students expressed feeling that they are unable to be better because of these negative stereotypes against them.

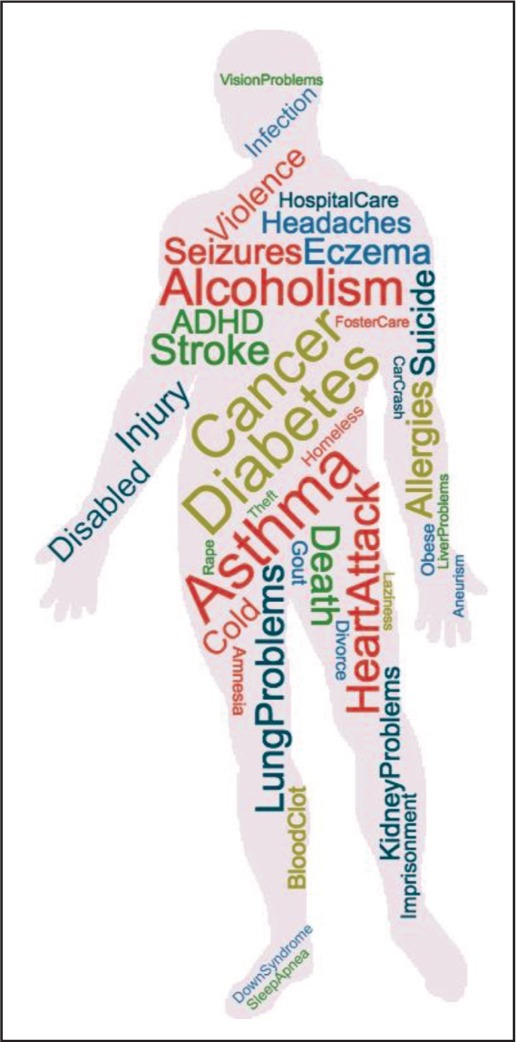

Students identified several health concerns related to themselves and their family members including asthma, allergies, diabetes, cancer, drug use, alcohol abuse, heart disease, trauma, and suicide among many more (see Figure 2). With the open-ended question format, students often listed descriptive terms, such as “breathing problems”, “heart problems” and “bad kidney”, rather than disease names, making frequency counts difficult. Other health topics of interest to students were cancer, sports/physical health, diabetes, prevention and management of chronic diseases afflicting family members. During the discussions, students openly shared how these health issues impact their lives. Students and families frequently have to adapt their schedules and ways of doing things, to care for ailing family members, including extended family members. Some students expressed that they could not do extracurricular activities, or spend time with friends because they had to help care for family members. Students expressed interest in learning how to prevent these health problems and how to help their family members manage these conditions.

Figure 2.

Health Concerns that 114 Students Identified from within Their Family and Community. Larger Words in the Word Cloud Represent Most Common Identified Health Concerns.

Conclusion and Next Steps

Student engagement and participatory strategies introduced by two young adult health care workers from the community yielded rich information from the students on the importance and strengths of the Native Hawaiian community, culture and ‘ohana. Despite facing many negative stereotypes, students have strong pride about their community, culture, ‘ohana and each other. The information gathered has been mapped to understand how the themes and health concerns align with community and school public health priorities. It is also being used to educate our SBHC providers and inform next steps that consider the importance of community and culture as a means to improve SBHC services. Community and culture are essential as the health educators and SBHC team develop new health education and health promotion initiatives for community ‘ōpio. The project is forming the basis for further discussions with students to inform the development of student-centered peer counseling and group support strategies aimed at improving student wellness and academic achievement.

We recognize several limitations to the project description presented. The initial steps described above have been taken in student engagement. Long-term outcomes demonstrating the work of the health educators are not yet known. Not all students were surveyed and we lack demographic details to know if the project is truly representative of all the students attending the schools. We also recognize the need to obtain input from teachers, school administration and staff, parents, grandparents, and others that work and care for community youth. Nonetheless, we are confident about the processes of student engagement and have subsequently built on these processes, over the last year, to successfully implement health education initiatives to increase student awareness, literacy, and action, about reproductive health, suicide prevention, and prescription drug abuse in the community.

Discussion

Community involvement in health programs have been shown to improve health outcomes and reduce health disparities.20,21 Such programs increase efficacy of community members, including students, as communicators, and build participant confidence to tackle local health concerns. Participatory strategies have been used to effectively engage students and school staff in many different initiatives including community needs assessments, community food programs, student wellness, and environmental issues.22,23

The consideration of cultural factors, community building capacity, and community empowerment may be especially important in reducing the health and educational disparities so common in indigenous communities.24 Researchers working with Native Hawaiian and Other Pacific Islander youth have used community participatory methods to successfully develop and implement interventions to prevent drug and alcohol use, as well as suicide.25 WCCHC is now successfully working with community members, including school staff and community leaders, using community-engaged participatory methods to understand the needs of youth of the Wai‘anae Coast, and develop more effective programming to address these needs.

Data gathered from community engagement has been used successfully as leverage points to change policies, programs, and systems that can lead to more sustainable improvement in health and educational outcomes.20,25 This may be especially important in data gathered from and by non-conventional partners, such as students from indigenous communities. Additional resources will undoubtedly be needed to develop new health education strategies and programs based on this information. However, for communities faced with health and educational disparities, programs implementing similar participatory strategies may, in the long run, be more effective and efficient than those based on conventional models.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Wai‘anae Coast Intermediate and High public-school principals, teachers, staff, and Wai‘anae community for their continued efforts and support in empowering the ‘opio of the Wai‘anae Coast. Most importantly we would like to thank the ‘opio for sharing their stories with us, as each student voice is so valued and appreciated.

Abbreviations

- DOE

Department of Education

- SBHC

School Based Health Center

- WCCHC

Waianae Coast Comprehensive Health Center

- WHS

Wai‘anae High School

- WIS

Wai‘anae Intermediate School

Conflict of Interest

None of the authors identify a conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Ickovics JR, Carroll-Scott A, Peters SM, Schwartz M, Gilstad-Hayden K, McCaslin C. Health and academic achievement: cumulative effects of health assets on standardized test scores among urban youth in the United States. J Sch Health. 2014;84((1)):40–8. doi: 10.1111/josh.12117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fiscella K, Kitzman H. Disparities in academic achievement and health: the intersection of child education and health policy. Pediatrics. 2009 Mar;123((3)):1073–80. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-0533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gase LN, Kuo T, Coller K, Guerrero LR, Wong MD. Assessing the connection between health and education: identifying potential leverage points for public health to improve school attendance. Am J Public Health. 2014 Sep;104((9)):e47–54. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2014.301977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hawaii Health Data Warehouse Youth Risk Behavior Survey. Available at: http://hhdw.org/health-reports-data/data-source/yrbs-reports/. Accessed on 02/07/2019.

- 5.Haliniak C. L. 1. Vol. 2017. Honolulu, HI: Office of Hawaiian Affairs, Research Division, Special Projects; 2017. A Native Hawaiian Focus on the Hawai‘i Public School System, SY2015. (Ho‘ona‘auao (Education) Fact Sheet. Accessed on 02/08/2019. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Okihiro M, Pillen M, Ancog C, Inda C, Sehgal V. Implementing the Obesity Care Model at a Community Health Center in Hawaii to Address Childhood Obesity. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2013 May;24((2 Suppl)):1–11. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2013.0108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Office of Hawaiian Affairs Mauli Ola and the Determinants of Health. Available at: https://www.oha.org/health. Accessed on 02/01/2019.

- 8.Okihiro M, Davis J, White L, Derauf C. Rapid growth from 12 to 23 months of life predicts obesity in a population of Pacific Island children. Ethn Dis. 2012 Autumn;22((4)):439–44. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liu DM, Alameda CK. Social determinants of health for Native Hawaiian children and adolescents. Hawaii Med J. 2011;70((11 Suppl 2)):9–14. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kana‘iaupuni S, Malone N, Ishibashi K. Summary of Ka Huaka'i Findings. Honolulu: Kamehameha Schools--PASE; Income and Poverty Among Native Hawaiians. 05-06:5 Available at: http://www.ksbe.edu/_assets/spi/pdfs/reports/demography_well-being/05_06_5.pdf. Accessed on 02/07/2019. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kisker EE, Brown RS. Do school-based health centers improve adolescents' access to health care, health status, and risk-taking behavior? J Adolesc Health. 1996 May;18((5)):335–43. doi: 10.1016/1054-139X(95)00236-L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Walker SC, Kerns SE, Lyon AR, Bruns EJ, Cosgrove TJ. Impact of School-Based Health Center use on academic outcomes. J Adolesc Health. 2010 Mar;46((3)):251–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2009.07.002. Epub 2009 Aug 28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Love H, Soleimanpour S, Panchal N, Schlitt J, Behr C, Even M. Washington, D.C.: School-Based Health Alliance; 2018. 2016-17 National School-Based Health Care Census Report. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Allison M, Crane L, Beaty B, Davidson A, Melinkovich P, Kempe A. School-Based Health Centers: Improving Access and Quality of Care for Low-Income Adolescents. Pediatrics. 2007 Oct;120((4)):e887–e894. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-2314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.U.S. Census Bureau QuickFacts: Waianae CDP, Hawaii. https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/waianaecdphawaii/LND110210. Accessed on 02/08/2019.

- 16.Office of Hawaiian Affairs Native Hawaiian Health Fact Sheet 2015. Volume 1 Chronic Diseases. Available at: https://www.oha.org/wp-content/uploads/Volume-I-Chronic-Diseases-FINAL.pdf. Accessed on 02/06/2019.

- 17. Hawaii Health Data Warehouse. http://ibis.hhdw.org/ibisph-view/query/builder/brfss/DXDiabetes/DXDiabetesAA11_.html. Accessed on 02/07/2019.

- 18.Wilson N., Minkler M., Dasho S., Wallerstein N., Martin A. C. Getting to Social Action: The Youth Empowerment Strategies (YES!) Project. Health Promotion Practice. 2008;9((4)):395–403. doi: 10.1177/1524839906289072. ,Behr. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hawaii State Department of Education Health and Nutrition Education Guidelines. http://www.hawaiipublicschools.org/TeachingAndLearning/HealthAndNutrition/WellnessGuidelines/Pages/NHS.aspx. Accessed on 02/07/2019.

- 20.Israel G, Coleman D, Ilvento T. Student Involvement in Community Needs Assessment. Journal of the Community Development Society. 1993;24(2):249–269. doi: 10.1080/15575339309489911. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Allison J, Khan T, Reese E, Dobias BS, Struna J. Lessons from Labor Organizing Community and Health Project: Meeting the Challenges of Student Engagement in Community Based Participatory Research. J Public Scholarship in Higher Education. 5((2015)):5–23. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rifkin SB. Examining the links between community participation and health outcomes: a review of the literature. Health Policy Plan. 2014;29 Suppl 2((Suppl 2)):ii98–106. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czu076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Margolis PA, Stevens R, Bordley WC, Stuart J, Harlan C, Keyes-Elstein L, Wisseh S. From concept to application: the impact of a community-wide intervention to improve the delivery of preventive services to children. Pediatrics. 2001 Sep;108((3)):E42. doi: 10.1542/peds.108.3.e42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Allison J, Khan T, Reese E, Dobias BS, Struna J. Lessons from Labor Organizing Community and Health Project: Meeting the Challenges of Student Engagement in Community Based Participatory Research. J Public Scholarship in Higher Education. 5((2015)):5–23. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Helm S, Okamoto SK, Medeiros H, et al. Participatory drug prevention research in rural Hawai‘i with native Hawaiian middle school students. Prog Community Health Partnersh. 2008;2((4)):307–313. doi: 10.1353/cpr.0.0042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Aseron J, Wilde S, Miller A, Kelly S. Indigenous Student Participation In Higher Education: Emergent Themes And Linkages. Contemporary Issues in Education Research (CIER) 2013;6(417) doi: 10.19030/cier.v6i4.8110. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Luluquisen M, Pettis L. Community engagement for policy and systems change. Community Development. 2014;45(3):252–262. doi: 10.1080/15575330.2014.905613. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Weiss H, Lopez ME, Rosenberg H. Beyond Random Acts: Family, School, and Community Engagement as an Integral Part of Education Reform. National Policy Forum for Family, School, & Community Engagement. Available at: https://www.sedl.org/connections/engagement_forum/beyond_random_acts.pdf. Accessed on 02/09/2019.