Abstract

Purpose: We evaluated the expression of autotaxin-lysophosphatidate signaling-related proteins and the clinical implications for metastatic breast cancer. Methods: We constructed tissue microarrays (TMA) with 126 cases of metastatic breast cancer [31 (24.6%) bone metastases, 36 (28.6%) brain metastases, 11 (8.7%) liver metastases, and 48 (38.1%) lung metastasis], and we conducted immunohistochemical staining for the autotoxin-lysophosphatidate signaling-related proteins ATX, LPA1, LPA2, and LPA3. Results: Stromal ATX (P = 0.006) and LPA1 (P < 0.001) were differently expressed according to their metastatic organ; stromal ATX showed high expression in bone metastasis, and LPA1 showed high expression in liver and lung metastases. Stromal ATX positivity was higher than others in luminal A type tumors (P = 0.035), and stromal LPA3 positivity was correlated with a high Ki-67 labeling index (LI) (P = 0.005). In univariate analysis, tumoral LPA3 negativity was correlated with shorter overall survival (OS) (P = 0.015) in metastatic breast cancer. When analyzed according to the metastatic sites, tumoral LPA3 negativity was correlated with shorter OS (P = 0.010) in lung metastasis, whereas stromal LPA3 negativity was correlated with shorter OS (P = 0.026) in brain metastasis. In multivariate Cox analysis, tumoral LPA3 negativity was an independent poor prognostic factor (HR = 2.311, 95% CI: 1.029-5.191, P = 0.043). Conclusion: Among autotoxin-lysophosphatidate signaling-related proteins, stromal ATX was highly expressed in bone metastases, and LPA1 was highly expressed in liver and lung metastases. Tumoral LPA3 might be a prognostic factor in metastatic breast cancer.

Keywords: Autotaxin, breast cancer, lysophosphatidate receptor, metastasis

Introduction

Autotaxin (ATX) is a glycoprotein transcribed by the ENPP2 gene on chromosome 8 [1]. ATX is the same molecule as lysophospholipase D, so it converts lysophosphatidylcholine (LPC) to the bioactive lipid mediator lysophosphatidate (LPA). LPA, after binding to the appropriate receptor, activates phospholipase C, the MAPK pathway, the PI3K pathway, and the PhoA pathway, and it is involved in various cellular processes [2,3]. The LPA receptor is a G-protein coupled receptor. There are at least 6 LPA receptors, LPA1-LPA6. LPA1-LPA3 belong to the EGD family (LPA1-EDG2, LPA2-EDG4, LPA3-EDG7), and LPA4-LPA6 are similar to the P2Y nucleotide receptor [4]. ATX-LPA signaling is involved in tumor formation, progression, and metastasis [5,6]. The expression of ATX and LPA1-3 has been reported to be especially high in breast cancer, and ATX, LPA, and LAP receptors in breast cancer are involved in angiogenesis, tumor cell invasion, and migration [7].

Breast cancer has both high morbidity and mortality, which is mainly attributed to distant metastasis. The main metastatic sites of breast cancer are the lung, brain, liver, and bones [8,9]; however, most current studies have involved brain and bone metastases [10-15]. The general pathogenesis of tumor metastasis involves a reciprocal interaction between tumor cells and host tissue, consisting of adhesion, proteolysis, invasion, and angiogenesis [9,16]. As has been reported previously, metastatic breast cancer shows specific tumor characteristics according to the metastatic site, young age, ER negativity, prior lung metastasis, HER-2 overexpression, EGFR overexpression, and basal subtype [12-14]. Lower histologic grade, ER positivity, ER positivity/PR negativity, strand growth pattern, and the presence of fibrotic foci in invasive ductal carcinoma are associated with bone metastasis [11,17,18]. Consequently, it is easily presumed that metastatic breast cancer can have different tumor characteristics according to the metastatic site. ATX-LPA signaling in breast cancer has been reported to be involved in metastasis, and the expression of ATX and LPAR in breast cancer is especially associated with advanced metastatic disease [19]. The overexpression of ATX or LPA1-3 in transgenic mice results in lung metastasis [20]. However, studies on autotaxin-lysophosphatidate signaling-related proteins in metastatic breast cancer according to the metastatic sites have not yet been reported, so we aimed to assess the expression of autotaxin-lysophosphatidate signaling-related proteins and related clinical implications in metastatic breast cancer according to the metastatic site.

Materials and methods

Patient selection and histologic evaluation

Cases of metastatic breast cancer to the liver, lung, brain, and bone were selected from the data files of the Department of Pathology, Severance Hospital. Only patients who were diagnosed with invasive ductal carcinoma were included. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Severance Hospital. A total of 126 cases were retrieved and all the slides that were prepared per case were reviewed. Pathologic diagnoses were confirmed by 2 pathologists (JSK and WJ), and the histological grade was assessed using the Nottingham grading system [21].

Tissue microarray (TMA)

A representative area showing tumor and tumor stroma was selected on an H&E-stained slide, and a corresponding spot was marked on the surface of the paraffin block. Using a biopsy needle, the selected area was punched out, and a 3-mm tissue core was transferred to a 6 x 5 recipient block. Two tissue cores from each invasive tumor were extracted to minimize extraction bias. Each tissue core was assigned a unique tissue microarray location number that was linked to a database containing other clinicopathologic data.

Immunohistochemistry

The antibodies used for immunohistochemistry are shown in Table 1. Formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissue sections were used for immunohistochemistry, and 3-μm-thick tissue sections were deparaffinized and rehydrated in xylene and graded alcohol. We used a Ventana Discovery XT automated stainer (Ventana Medical System, Tucson, AZ, USA). CC1 buffer (Cell Conditioning 1; citrate buffer Ph 6.0, Ventana Medical System) was used for antigen retrieval. Appropriate positive and negative controls were used for each antibody. The positive controls were used according to the manufacturer’s instructions (ATX; human tonsil tissue, LPA1; human thyroid tissue, LPA2; Breast cancer tissue, LPA3; Human prostate carcinoma). A negative control was used with a secondary antibody alone and the primary antibody omitted.

Table 1.

Source, clone, and dilution of antibodies

| Antibody | Company | Clone | Dilution |

|---|---|---|---|

| Autotaxin-related proteins | |||

| ATX | Abcam, Cambridge, UK | Polyclonal | 1:1000 |

| LPA1 | Abcam, Cambridge, UK | EPR9710 | 1:100 |

| LPA2 | Abcam, Cambridge, UK | Polyclonal | 1:100 |

| LPA3 | Abcam, Cambridge, UK | Polyclonal | 1:250 |

| Molecular subtype-related proteins | |||

| Estrogen receptor | Thermo Scientific, San Diego, CA, USA | SP1 | 1:100 |

| Progesterone receptor | DAKO, Glostrup, Denmark | PgR | 1:50 |

| Human epidermal growth factor receptor-2 | DAKO, Glostrup, Denmark | Polyclonal | 1:1500 |

| Ki-67 | Abcam, Cambridge, UK | SP6 | 1:100 |

Autotaxin (ATX), also known as ectonucleotide pyrophosphatase/phosphhodesterase 2 (ENPP2), LPA1-EDG2, LPA2-EDG4, and LPA3-EDG7.

Interpretation of immunohistochemical staining

All immunohistochemical markers were assessed by light microscopy. A cut-off value of 1% or more positively stained nuclei was used to define ER and PR positivity [22]. HER-2 staining was analyzed according to the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO)/College of American Pathologists (CAP) guidelines using the following categories: 0 = no immunostaining; 1+ = weak incomplete membranous staining, less than 10% of tumor cells; 2+ = complete membranous staining, either uniform or weak in at least 10% of tumor cells; and 3+ = uniform intense membranous staining in at least 30% of tumor cells [23]. HER-2 immunostaining was considered positive when strong (3+) membranous staining was observed, but cases with 0 to 1+ were regarded as negative. Cases showing 2+ HER-2 expression were evaluated for HER-2 amplification by fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH). The Ki-67 labeling index (LI) was defined as the percentage of tumor cells showing positive nuclear staining.

All stained slides were semi-quantitatively evaluated [24]. Tumor and stromal cell staining were assessed as 0: negative or weak immunostaining in < 1% of the tumor/stroma, 1: focal expression in 1-10% of tumor/stroma, 2: positive in 11-50% of tumor/stroma, and 3: positive in 51-100% of tumor/stroma. Entire tumor areas included in the TMA were evaluated in all cases, and a score of 0 was considered negative, while a score of 1 to 3 was considered as positive.

Western blotting

Deparaffinization and protein extraction of the FFPE tissue was carried out using a Qproteome FFPE Tissue Kit (Qiagen, 1042481) following the manufacturer’s instructions. Extracted proteins were determined using a Bradford assay (BIO-RAD, 5000205). Quantified proteins were mixed with 5X SDS-PAGE loading buffer (Biosesang, S2002) at a concentration of 2 μg/μl and boiled at 95°C for 5 min. Equal quantities of protein were separated to SDS-PAGE gel and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes (Bio-Rad 1704158). Membranes were blocked by incubation in 5% skim milk in Tris-buffered saline (TBS) with 0.1% Tween-20 and probed with antibody against ATX (1:1000, Abcam, ab140915), LPA1 (1:2000, Abcam, ab166903), and LPA2 (1:1000, Abcam ab38322) diluted in 1% BSA in TBS, 0.1% Tween 20, and 0.02% NaN3. The membranes were washed and then incubated with secondary antibodies (HRP conjugated anti-mouse IgG, or anti-rabbit IgG) (1:20000, Santa Cruz) for 1 h at room temperature. The bands were visualized using WesternBright ECL (advansata, K-12045-D50) after washing the membrane and exposed to x-ray film.

Tumor phenotype classification

In this study, we classified breast cancer phenotypes according to the immunohistochemistry results for ER, PR, HER-2, Ki-67, and FISH results for HER-2 as follows [25]: luminal A type, ER or/and PR positive, HER-2 negative and Ki-67 LI < 14%; Luminal B type, (HER-2 negative) ER or/and PR positive, HER-2 negative and Ki-67 LI ≥ 14%; (HER-2 positive) ER or/and PR positive and HER-2 overexpressed or/and amplified; HER-2 overexpression type, ER and PR negative and HER-2 overexpressed or/and amplified; TNBC type: ER, PR, and HER-2 negative.

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using SPSS for Windows, Version 23.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). For the determination of statistical significance, Student’s t and Fisher’s exact tests were used for continuous and categorical variables, respectively. On multiple comparisons, a corrected p-value from Bonferroni multiple comparisons was used. Statistical significance was set to P < 0.05. Kaplan-Meier survival curves and log-rank statistics were employed to evaluate time to tumor recurrence and overall survival. Multivariate regression analysis was performed using the Cox proportional hazards model.

Results

Basal characteristics of metastatic breast cancer

A total of 126 cases of metastatic breast cancer were assessed and categorized as 31 (24.6%) bone metastases, 36 (28.6%) brain metastases, 11 (8.7%) liver metastases, and 48 (38.1%) lung metastases. ER (P < 0.001), PR (P < 0.001), HER-2 (P = 0.032), Ki-67 LI (P = 0.008), and molecular subtype (P < 0.001) showed significantly different results according to the metastatic site. Brain metastases, for example, showed higher rates of ER negativity, PR negativity, and HER-2 positivity as well as higher Ki-67 LI when compared with tumors metastatic to other sites. Luminal A type tumors were more frequently observed in bone and liver metastases, HER-2 and TNBC in brain metastases, and TNBC in lung metastases (Table 2).

Table 2.

Basal characteristics of patients with metastatic breast cancer

| Parameter | Total | Metastatic site | P-value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||||

| N = 126 (%) | Bone | Brain | Liver | Lung | ||

| N = 31 (%) | N = 36 (%) | N = 11 (%) | N = 48 (%) | |||

| Age (years) | 0.605 | |||||

| ≤ 50 | 65 (51.6) | 17 (54.8) | 17 (47.2) | 4 (36.4) | 27 (56.3) | |

| > 50 | 61 (48.4) | 14 (45.2) | 19 (52.8) | 7 (63.6) | 21 (43.8) | |

| ER | < 0.001 | |||||

| Negative | 59 (46.8) | 6 (19.4) | 25 (69.4) | 2 (18.2) | 26 (54.2) | |

| Positive | 67 (53.2) | 25 (80.6) | 11 (30.6) | 9 (81.8) | 22 (45.8) | |

| PR | < 0.001 | |||||

| Negative | 86 (68.3) | 16 (51.6) | 35 (97.2) | 3 (27.3) | 32 (66.7) | |

| Positive | 40 (31.7) | 15 (48.4) | 1 (2.8) | 8 (72.7) | 16 (33.3) | |

| HER-2 | 0.032 | |||||

| Negative | 86 (68.3) | 25 (80.6) | 18 (50.0) | 9 (81.8) | 34 (70.8) | |

| Positive | 40 (31.7) | 6 (19.4) | 18 (50.0) | 2 (18.2) | 14 (29.2) | |

| Ki-67 LI | 0.008 | |||||

| < 14 | 84 (66.7) | 27 (87.1) | 18 (50.0) | 9 (81.8) | 30 (62.5) | |

| ≥ 14 | 42 (33.3) | 4 (12.9) | 18 (50.0) | 2 (18.2) | 18 (37.5) | |

| Molecular subtype | < 0.001 | |||||

| Luminal A | 44 (34.9) | 21 (67.7) | 3 (8.3) | 6 (54.5) | 14 (29.2) | |

| Luminal B | 24 (19.0) | 5 (16.1) | 8 (22.2) | 3 (27.3) | 8 (16.7) | |

| HER-2 | 25 (19.8) | 3 (9.7) | 12 (33.3) | 1 (9.1) | 9 (18.8) | |

| TNBC | 33 (26.2) | 2 (6.5) | 13 (36.1) | 1 (9.1) | 17 (35.4) | |

| Patient death | 41 (32.5) | 16 (51.6) | 11 (30.6) | 4 (36.4) | 10 (20.8) | 0.041 |

ER, estrogen receptor; PR, progesterone receptor; HER-2, human epidermal growth factor receptor-2; LI, labeling index; TNBC, triple-negative breast cancer.

The expressions of autotaxin-lysophosphatidate signaling-related proteins in metastatic breast cancer according to the metastatic site

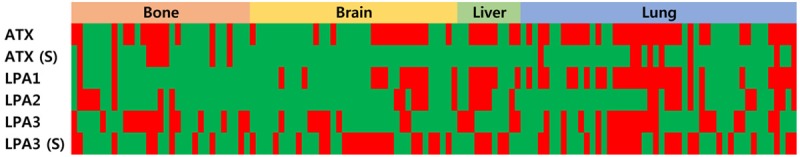

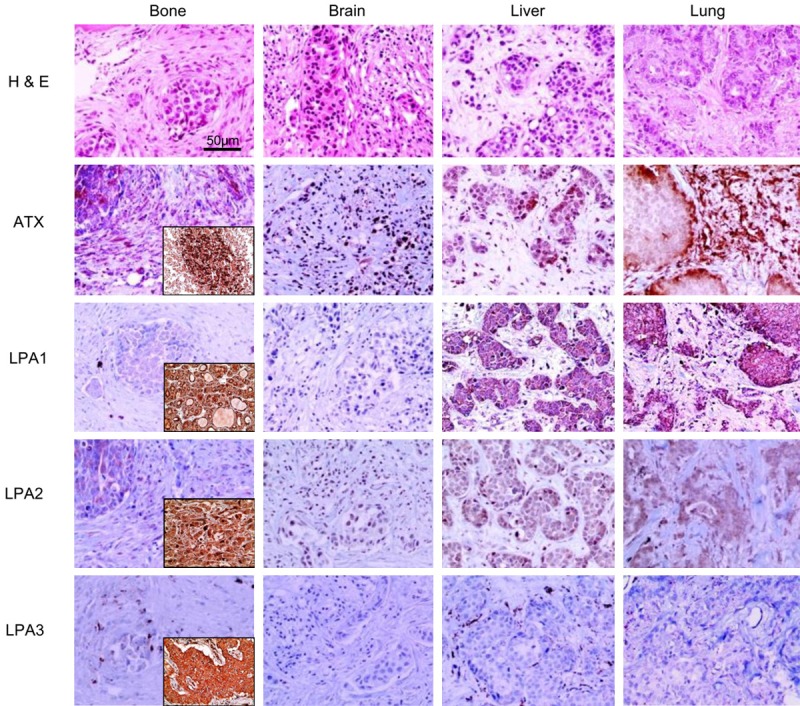

Results on the differential expressions of autotaxin-lysophosphatidate signaling-related proteins in metastatic breast cancer according to metastatic site showed that the expressions of stromal ATX (P = 0.006) and LPA1 (P < 0.001) were statistically different (Table 3 and Figure 1). The expression rate of stromal ATX was the highest in bone metastases, whereas that of LPA1 in tumor cells was the highest in liver and lung metastases (Figure 2). The interpretation of positive and negative expressions was relatively clear-cut because none showed score 1 (1-10% positive) in ATX, LPA1, LPA2, or LPA3 staining. Also, none of the cases showed LPA1 or LPA2 expressions in the stromal cells. Those that stained positively on ATX and LPA3 staining in stromal compartment were identified as immune cells and fibroblasts. In Western blot, just as in IHC, the expression rate of stromal ATX was the highest in the bone metastases and the expression rate of LPA1 in tumor cells was the highest in the liver and lung metastases (Figure 3).

Table 3.

Expression of autotaxin-lysophosphatidate signaling-related proteins according to the metastatic site in breast cancer metastases

| Parameter | Total | Metastatic site | P-value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||||

| N = 126 (%) | Bone | Brain | Liver | Lung | ||

| N = 31 (%) | N = 36 (%) | N = 11 (%) | N = 48 (%) | |||

| ATX (T) | 0.061 | |||||

| Negative | 61 (48.4) | 18 (58.1) | 22 (61.1) | 4 (36.4) | 17 (35.4) | |

| Positive | 65 (51.6) | 13 (41.9) | 14 (38.9) | 7 (63.6) | 31 (64.6) | |

| ATX (S) | 0.006 | |||||

| Negative | 110 (87.3) | 23 (74.2) | 36 (100.0) | 11 (100.0) | 40 (83.3) | |

| Positive | 16 (12.7) | 8 (25.8) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 8 (16.7) | |

| LPA1 | < 0.001 | |||||

| Negative | 79 (62.7) | 29 (93.5) | 25 (69.4) | 5 (45.5) | 20 (41.7) | |

| Positive | 47 (37.3) | 2 (6.5) | 11 (30.6) | 6 (54.5) | 28 (58.3) | |

| LPA2 | 0.271 | |||||

| Negative | 96 (76.2) | 24 (77.4) | 30 (83.3) | 6 (54.5) | 36 (75.0) | |

| Positive | 30 (23.8) | 7 (22.6) | 6 (16.7) | 5 (45.5) | 12 (25.0) | |

| LPA3 (T) | 0.124 | |||||

| Negative | 78 (61.9) | 16 (51.6) | 28 (77.8) | 6 (54.5) | 28 (58.3) | |

| Positive | 48 (38.1) | 15 (48.4) | 8 (22.2) | 5 (45.5) | 20 (41.7) | |

| LPA3 (S) | 0.237 | |||||

| Negative | 70 (55.6) | 22 (71.0) | 17 (47.2) | 6 (54.5) | 25 (52.1) | |

| Positive | 56 (44.4) | 9 (29.0) | 19 (52.8) | 5 (45.5) | 23 (47.9) | |

The p-value was calculated using Student’s t-test.

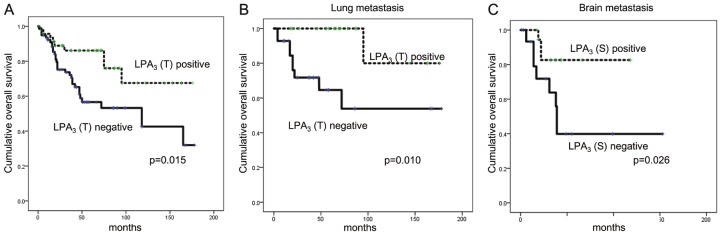

Figure 1.

Heat map of the expression of autotaxin-lysophosphatidate signaling-related proteins according to the metastatic site in metastatic breast cancer. S, stroma.

Figure 2.

Expressions of autotaxin-lysophosphatidate signaling-related proteins according to the metastatic site in metastatic breast cancer. Stromal ATX is highly expressed in bone and lung metastases, and tumoral LPA1 is highly expressed in liver and lung metastases. The insets represent the positive controls.

Figure 3.

Western blot for autotaxin-lysophosphatidate signaling-related proteins according to the metastatic site in metastatic breast cancer. Stromal ATX is highly expressed in bone and lung metastases, and tumoral LPA1 is highly expressed in liver and lung metastases.

The correlation between clinicopathologic factors and the expression of autotaxin-lysophosphatidate signaling-related proteins

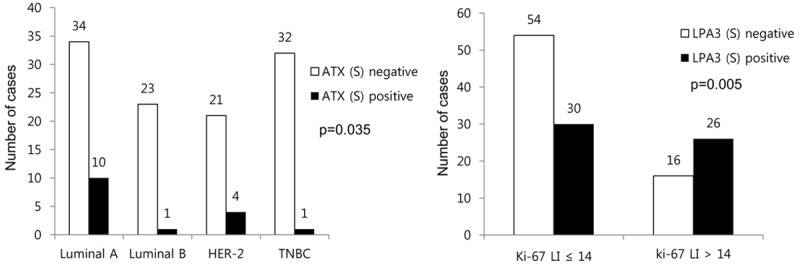

The correlation analysis on the expression of autotaxin-lysophosphatidate signaling-related proteins and clinicopathologic factors revealed that stromal ATX positivity was higher in luminal A tumors than in other tumor subtypes (P = 0.035), and stromal LPA3 positivity was correlated with a high Ki-67 LI (P = 0.005, Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Correlation between clinicopathologic factors and the expression of autotaxin-lysophosphatidate signaling-related proteins.

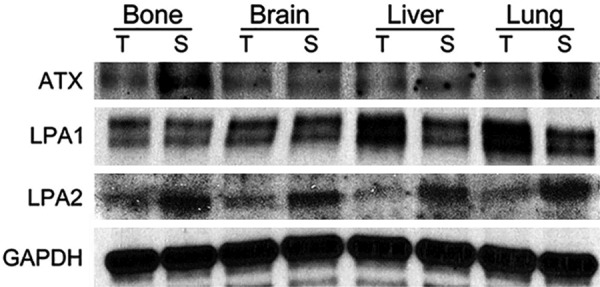

The impact of autotaxin-lysophosphatidate signaling-related protein expression on the prognosis of metastatic breast cancer

Univariate analysis of the impact of autotaxin-lysophosphatidate signaling-related protein expression on the prognosis of metastatic breast cancer showed that tumoral LPA3 negativity was correlated with shorter OS (P = 0.015, Figure 5). According to the metastatic site, tumoral LPA3 negativity was correlated with shorter OS in lung metastasis (P = 0.010) and stromal LPA3 negativity with shorter OS in brain metastasis (P = 0.026, Table 4). Multivariate Cox analysis showed that tumoral LPA3 negativity is a poor independent prognostic factor (HR = 2.311, 95% CI: 1.029-5.191, P = 0.043, Table 5).

Figure 5.

The impact of tumoral LPA3 on prognosis in overall metastatic breast cancer (A), lung metastasis (B), and stromal LPA3 in brain metastasis (C).

Table 4.

Univariate analysis of the association between expressions of autotaxin-lysophosphatidate signaling-related proteins in metastatic breast cancers and overall survival on a log-rank test

| Parameters | Total, N = 149 (%) | Metastatic site | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||||

| Bone, N = 31 (%) | Brain, N = 36 (%) | Liver, N = 11 (%) | Lung, N = 48 (%) | |||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||

| Mean survival (95% CI) months | P-value | Mean survival (95% CI) months | P-value | Mean survival (95% CI) months | P-value | Mean survival (95% CI) months | P-value | Mean survival (95% CI) months | P-value | |

| ATX (T) | 0.055 | 0.522 | 0.129 | 0.460 | 0.787 | |||||

| Negative | 100 (79-120) | 79 (47-111) | 71 (49-93) | 47 (47-47) | 140 (103-177) | |||||

| Positive | 127 (104-149) | 68 (49-87) | 131 (103-158) | 85 (52-117) | 127 (95-158) | |||||

| ATX (S) | 0.807 | 0.514 | N/A | N/A | 0.420 | |||||

| Negative | 113 (97-129) | 89 (58-119) | N/A | N/A | 126 (96-155) | |||||

| Positive | 113 (76-149) | 52 (29-74) | N/A | N/A | 144 (106-183) | |||||

| LPA1 | 0.159 | 0.211 | 0.307 | 0.843 | 0.917 | |||||

| Negative | 105 (86-124) | 86 (60-112) | 75 (54-96) | 61 (38-85) | 139 (106-172) | |||||

| Positive | 122 (100-145) | 16 (16-16) | 125 (91-159) | 80 (44-117) | 119 (87-151) | |||||

| LPA2 | 0.896 | 0.969 | 0.416 | 0.761 | 0.208 | |||||

| Negative | 114 (97-131) | 85 (55-115) | 99 (73-125) | 80 (47-112) | 137 (109-166) | |||||

| Positive | 109 (81-137) | 65 (43-86) | 84 (59-110) | 61 (28-93) | 114 (73-155) | |||||

| LPA3 (T) | 0.015 | 0.191 | 0.132 | N/A | 0.010 | |||||

| Negative | 100 (81-120) | 72 (39-105) | 87 (69-104) | N/A | 111 (76-146) | |||||

| Positive | 136 (113-159) | 86 (62-110) | 82 (26-139) | N/A | 159 (131-188) | |||||

| LPA3 (S) | 0.609 | 0.089 | 0.026 | N/A | 0.629 | |||||

| Negative | 111 (92-131) | 94 (64-124) | 76 (42-110) | N/A | 133 (103-164) | |||||

| Positive | 107 (83-130) | 41 (16-65) | 101 (83-118) | N/A | 111 (68-153) | |||||

CI, confidence interval; n/a, not applicable.

Table 5.

Multivariate Cox analysis of the association between expressions of autotaxin-lysophosphatidate signaling-related proteins in metastatic breast cancers and overall survival

| Included parameters | Metastatic breast cancer | ||

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Overall survival | |||

|

| |||

| HR | 95% CI | P-value | |

| ER status | 0.522 | ||

| Negative vs. positive | 1.634 | 0.363-7.354 | |

| PR status | 0.904 | ||

| Negative vs. positive | 0.943 | 0.360-2.466 | |

| HER-2 status | 0.147 | ||

| Negative vs. positive | 0.379 | 0.102-1.407 | |

| Molecular subtype | 0.735 | ||

| TNBC vs. non-TNBC | 1.337 | 0.249-7.173 | |

| ATX (T) | 0.459 | ||

| Negative vs. positive | 1.308 | 0.642-2.663 | |

| LPA3 (T) | 0.043 | ||

| Negative vs. positive | 2.311 | 1.029-5.191 | |

HR, hazard ratio; CI, confidential interval; ER, estrogen receptor; PR, progesterone receptor; HER-2, human epidermal growth factor-2; TNBC, triple-negative breast cancer.

Discussion

We assessed the expression of ATX-LPA signaling-related proteins in metastatic breast cancer according to the metastatic site. First of all, ATX and LPA3 were expressed not only in the tumor cells but also in the tumor stroma. ATX is often expressed in cells other than tumor cells [19,26], such as platelets, endothelial cells, fibroblasts, and adipocytes [27-30]. Therefore, it is plausible that ATX is found in breast cancer stromal cells [19]. In addition, LPA3 is expressed in breast cancer stromal cells [19]. Our results demonstrated ATX expression in the stroma of metastatic breast cancer to the lung and bone, and the stromal expression of ATX was especially high in the latter. A previous study reported that inflammatory mediators secreted by breast cancer cells activate ATX secretions from adipocytes adjacent to the breast cancer tumor cells, which activates LPA signaling. Activated LPA signaling then increases the secretion of inflammatory mediators from the breast cancer cells [31]. This suggests a possibility that ATX secreted from breast cancer stromal cells enables tumor-stroma interaction, which leads to the hypothesis that ATX expressed in the stroma of metastatic breast cancer in the lung and bones may influence tumor progression. Wannecq et al. reported that ATX is involved in the formation of bone metastasis through the activation of osteoclasts by LPA signaling [32], thereby explaining the high expression of stromal ATX in bone metastasis.

In this study, LPA1 was highly expressed in liver and lung metastases. An overexpression of LPA1 in transgenic mice results in lung metastasis [20], and lung metastasis of basal breast cancer result from the LPA1/ZEB1/miR-21-activation pathway. These results are in concordance with our study results [33].

The clinical implication of our study is that the ATX-LPA signaling axis may be a possible therapeutic target in metastatic breast cancer. Ki16425, a non-lipid competitive inhibitor of LPA1 and LPA3, actually suppresses bone metastases of breast cancer in a mouse model [30], and Debio0719, an R-stereoisomer of Ki16425, inhibits lung and bone metastases [34] and liver and lung metastasis [35] of breast cancer in a mouse model. BrP-LPA, which is a dual ATX and pan-LPAR inhibitor, inhibited cell migration and invasion in a breast cancer cell line, and also suppressed primary tumor formation and angiogenesis in a mouse xenograft study [36]. In addition, the new ATX inhibitor ONO-843050 decreases tumor growth in a breast cancer mouse model and also decreases lung metastatic nodules up to 60% [37]. Therefore, the ATX-LPA signaling axis may be an effective therapeutic target for metastatic breast cancer, and further study is necessary.

In conclusion, among autotoxin-lysophosphatidate signaling-related proteins, stromal ATX is highly expressed in bone metastases, and LPA1 is highly expressed in liver and lung metastases. Furthermore, tumor LPA3 is an independent prognostic factor in metastatic breast cancer.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Science, Information and Communications Technology (ICT) and Future Planning (MSIP) (2015R1A1A1A05001209).

Disclosure of conflict of interest

None.

References

- 1.Jansen S, Stefan C, Creemers JW, Waelkens E, Van Eynde A, Stalmans W, Bollen M. Proteolytic maturation and activation of autotaxin (NPP2), a secreted metastasis-enhancing lysophospholipase D. J Cell Sci. 2005;118:3081–3089. doi: 10.1242/jcs.02438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.van Meeteren LA, Moolenaar WH. Regulation and biological activities of the autotaxin-LPA axis. Prog Lipid Res. 2007;46:145–160. doi: 10.1016/j.plipres.2007.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Choi JW, Herr DR, Noguchi K, Yung YC, Lee CW, Mutoh T, Lin ME, Teo ST, Park KE, Mosley AN, Chun J. LPA receptors: subtypes and biological actions. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2010;50:157–186. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.010909.105753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chun J, Hla T, Lynch KR, Spiegel S, Moolenaar WH. International union of basic and clinical pharmacology. LXXVIII. Lysophospholipid receptor nomenclature. Pharmacol Rev. 2010;62:579–587. doi: 10.1124/pr.110.003111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Houben AJ, Moolenaar WH. Autotaxin and LPA receptor signaling in cancer. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2011;30:557–565. doi: 10.1007/s10555-011-9319-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Willier S, Butt E, Grunewald TG. Lysophosphatidic acid (LPA) signalling in cell migration and cancer invasion: a focussed review and analysis of LPA receptor gene expression on the basis of more than 1700 cancer microarrays. Biol Cell. 2013;105:317–333. doi: 10.1111/boc.201300011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Teo K, Brunton VG. The role and therapeutic potential of the autotaxin-lysophosphatidate signalling axis in breast cancer. Biochem J. 2014;463:157–165. doi: 10.1042/BJ20140680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Weil RJ, Palmieri DC, Bronder JL, Stark AM, Steeg PS. Breast cancer metastasis to the central nervous system. Am J Pathol. 2005;167:913–920. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)61180-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Woodhouse EC, Chuaqui RF, Liotta LA. General mechanisms of metastasis. Cancer. 1997;80:1529–1537. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(19971015)80:8+<1529::aid-cncr2>3.3.co;2-#. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Abali H, Celik I. High incidence of central nervous system involvement in patients with breast cancer treated with epirubicin and docetaxel. Am J Clin Oncol. 2002;25:632–633. doi: 10.1097/00000421-200212000-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Colleoni M, O’Neill A, Goldhirsch A, Gelber RD, Bonetti M, Thurlimann B, Price KN, Castiglione-Gertsch M, Coates AS, Lindtner J, Collins J, Senn HJ, Cavalli F, Forbes J, Gudgeon A, Simoncini E, Cortes-Funes H, Veronesi A, Fey M, Rudenstam CM. Identifying breast cancer patients at high risk for bone metastases. J. Clin. Oncol. 2000;18:3925–3935. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2000.18.23.3925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Evans AJ, James JJ, Cornford EJ, Chan SY, Burrell HC, Pinder SE, Gutteridge E, Robertson JF, Hornbuckle J, Cheung KL. Brain metastases from breast cancer: identification of a high-risk group. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol) 2004;16:345–349. doi: 10.1016/j.clon.2004.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gaedcke J, Traub F, Milde S, Wilkens L, Stan A, Ostertag H, Christgen M, von Wasielewski R, Kreipe HH. Predominance of the basal type and HER-2/neu type in brain metastasis from breast cancer. Mod Pathol. 2007;20:864–870. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3800830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hicks DG, Short SM, Prescott NL, Tarr SM, Coleman KA, Yoder BJ, Crowe JP, Choueiri TK, Dawson AE, Budd GT, Tubbs RR, Casey G, Weil RJ. Breast cancers with brain metastases are more likely to be estrogen receptor negative, express the basal cytokeratin CK5/6, and overexpress HER2 or EGFR. Am J Surg Pathol. 2006;30:1097–1104. doi: 10.1097/01.pas.0000213306.05811.b9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lorincz T, Toth J, Badalian G, Timar J, Szendroi M. HER-2/neu genotype of breast cancer may change in bone metastasis. Pathol Oncol Res. 2006;12:149–152. doi: 10.1007/BF02893361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nicolson GL. Organ specificity of tumor metastasis: role of preferential adhesion, invasion and growth of malignant cells at specific secondary sites. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 1988;7:143–188. doi: 10.1007/BF00046483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hasebe T, Imoto S, Yokose T, Ishii G, Iwasaki M, Wada N. Histopathologic factors significantly associated with initial organ-specific metastasis by invasive ductal carcinoma of the breast: a prospective study. Hum Pathol. 2008;39:681–693. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2007.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wei B, Wang J, Bourne P, Yang Q, Hicks D, Bu H, Tang P. Bone metastasis is strongly associated with estrogen receptor-positive/progesterone receptor-negative breast carcinomas. Hum Pathol. 2008;39:1809–1815. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2008.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Popnikolov NK, Dalwadi BH, Thomas JD, Johannes GJ, Imagawa WT. Association of autotaxin and lysophosphatidic acid receptor 3 with aggressiveness of human breast carcinoma. Tumour Biol. 2012;33:2237–2243. doi: 10.1007/s13277-012-0485-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liu S, Umezu-Goto M, Murph M, Lu Y, Liu W, Zhang F, Yu S, Stephens LC, Cui X, Murrow G, Coombes K, Muller W, Hung MC, Perou CM, Lee AV, Fang X, Mills GB. Expression of autotaxin and lysophosphatidic acid receptors increases mammary tumorigenesis, invasion, and metastases. Cancer Cell. 2009;15:539–550. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2009.03.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Elston CW, Ellis IO. Pathological prognostic factors in breast cancer. I. The value of histological grade in breast cancer: experience from a large study with long-term follow-up. Histopathology. 1991;19:403–410. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.1991.tb00229.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hammond ME, Hayes DF, Dowsett M, Allred DC, Hagerty KL, Badve S, Fitzgibbons PL, Francis G, Goldstein NS, Hayes M, Hicks DG, Lester S, Love R, Mangu PB, McShane L, Miller K, Osborne CK, Paik S, Perlmutter J, Rhodes A, Sasano H, Schwartz JN, Sweep FC, Taube S, Torlakovic EE, Valenstein P, Viale G, Visscher D, Wheeler T, Williams RB, Wittliff JL, Wolff AC. American Society of Clinical Oncology/College of American Pathologists guideline recommendations for immunohistochemical testing of estrogen and progesterone receptors in breast cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2010;28:2784–2795. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.25.6529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wolff AC, Hammond ME, Schwartz JN, Hagerty KL, Allred DC, Cote RJ, Dowsett M, Fitzgibbons PL, Hanna WM, Langer A, McShane LM, Paik S, Pegram MD, Perez EA, Press MF, Rhodes A, Sturgeon C, Taube SE, Tubbs R, Vance GH, van de Vijver M, Wheeler TM, Hayes DF. American Society of Clinical Oncology/College of American Pathologists guideline recommendations for human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 testing in breast cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2007;25:118–145. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.09.2775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Choi J, Jung WH, Koo JS. Clinicopathologic features of molecular subtypes of triple negative breast cancer based on immunohistochemical markers. Histol Histopathol. 2012;27:1481–1493. doi: 10.14670/HH-27.1481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Goldhirsch A, Wood WC, Coates AS, Gelber RD, Thurlimann B, Senn HJ Panel members. Strategies for subtypes--dealing with the diversity of breast cancer: highlights of the St. Gallen International Expert Consensus on the Primary Therapy of Early Breast Cancer 2011. Ann Oncol. 2011;22:1736–1747. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdr304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Noh DY, Ahn SJ, Lee RA, Park IA, Kim JH, Suh PG, Ryu SH, Lee KH, Han JS. Overexpression of phospholipase D1 in human breast cancer tissues. Cancer Lett. 2000;161:207–214. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3835(00)00612-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ferry G, Tellier E, Try A, Gres S, Naime I, Simon MF, Rodriguez M, Boucher J, Tack I, Gesta S, Chomarat P, Dieu M, Raes M, Galizzi JP, Valet P, Boutin JA, Saulnier-Blache JS. Autotaxin is released from adipocytes, catalyzes lysophosphatidic acid synthesis, and activates preadipocyte proliferation. Up-regulated expression with adipocyte differentiation and obesity. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:18162–18169. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M301158200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nikitopoulou I, Oikonomou N, Karouzakis E, Sevastou I, Nikolaidou-Katsaridou N, Zhao Z, Mersinias V, Armaka M, Xu Y, Masu M, Mills GB, Gay S, Kollias G, Aidinis V. Autotaxin expression from synovial fibroblasts is essential for the pathogenesis of modeled arthritis. J Exp Med. 2012;209:925–933. doi: 10.1084/jem.20112012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mao Y, Keller ET, Garfield DH, Shen K, Wang J. Stromal cells in tumor microenvironment and breast cancer. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2013;32:303–315. doi: 10.1007/s10555-012-9415-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Boucharaba A, Serre CM, Gres S, Saulnier-Blache JS, Bordet JC, Guglielmi J, Clezardin P, Peyruchaud O. Platelet-derived lysophosphatidic acid supports the progression of osteolytic bone metastases in breast cancer. J Clin Invest. 2004;114:1714–1725. doi: 10.1172/JCI22123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Benesch MG, Tang X, Dewald J, Dong WF, Mackey JR, Hemmings DG, McMullen TP, Brindley DN. Tumor-induced inflammation in mammary adipose tissue stimulates a vicious cycle of autotaxin expression and breast cancer progression. FASEB J. 2015;29:3990–4000. doi: 10.1096/fj.15-274480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.David M, Wannecq E, Descotes F, Jansen S, Deux B, Ribeiro J, Serre CM, Gres S, Bendriss-Vermare N, Bollen M, Saez S, Aoki J, Saulnier-Blache JS, Clezardin P, Peyruchaud O. Cancer cell expression of autotaxin controls bone metastasis formation in mouse through lysophosphatidic acid-dependent activation of osteoclasts. PLoS One. 2010;5:e9741. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0009741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sahay D, Leblanc R, Grunewald TG, Ambatipudi S, Ribeiro J, Clezardin P, Peyruchaud O. The LPA1/ZEB1/miR-21-activation pathway regulates metastasis in basal breast cancer. Oncotarget. 2015;6:20604–20620. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.3774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.David M, Ribeiro J, Descotes F, Serre CM, Barbier M, Murone M, Clezardin P, Peyruchaud O. Targeting lysophosphatidic acid receptor type 1 with Debio 0719 inhibits spontaneous metastasis dissemination of breast cancer cells independently of cell proliferation and angiogenesis. Int J Oncol. 2012;40:1133–1141. doi: 10.3892/ijo.2011.1309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Marshall JC, Collins JW, Nakayama J, Horak CE, Liewehr DJ, Steinberg SM, Albaugh M, Vidal-Vanaclocha F, Palmieri D, Barbier M, Murone M, Steeg PS. Effect of inhibition of the lysophosphatidic acid receptor 1 on metastasis and metastatic dormancy in breast cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2012;104:1306–1319. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djs319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhang H, Xu X, Gajewiak J, Tsukahara R, Fujiwara Y, Liu J, Fells JI, Perygin D, Parrill AL, Tigyi G, Prestwich GD. Dual activity lysophosphatidic acid receptor pan-antagonist/autotaxin inhibitor reduces breast cancer cell migration in vitro and causes tumor regression in vivo. Cancer Res. 2009;69:5441–5449. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-0302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Benesch MG, Tang X, Maeda T, Ohhata A, Zhao YY, Kok BP, Dewald J, Hitt M, Curtis JM, McMullen TP, Brindley DN. Inhibition of autotaxin delays breast tumor growth and lung metastasis in mice. FASEB J. 2014;28:2655–2666. doi: 10.1096/fj.13-248641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]