Abstract

Epithelioid inflammatory myofibroblastic sarcoma (EIMS) is a rare entity and a novel variant of the inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor (IMT). We report the occurrence and specific characteristics of EMIS in an adult woman. Eleven months after the operation, the patient had a recurrence and multiple metastases in the abdominal cavity. Since the tumor was spreading all over the abdominal cavity and ALK staining of the tumor was positive, crizotinib was suggested as adjuvant therapy. But she failed to respond to the crizotinib treatment and died of organ failure three months later.

Keywords: Epithelioid inflammatory myofibroblastic sarcoma, ALK, crizotinib

Introduction

Inflammatory myofibroblastoma (IMT) is an interstitial neoplasm composed of myofibroblast spindle cells in a mucoid stroma. Its inflammatory infiltration mainly consists of plasma cells and lymphocytes, occasionally mixed with eosinophils and neutrophils [1]. Epithelioid inflammatory myofibroblastic sarcoma (EIMS) is a rare entity and a novel variant of the inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor (IMT), as it has similar malignant characteristics and mainly consists of round-to-epithelioid cells [2] with a pattern of nuclear membrane or perinuclear immunostaining for ALK receptor tyrosine kinase (hereafter ALK). EMIS is a rare disease. To the best of our knowledge, only 30 cases have been reported in the English-language medical literature. Herein, we report the occurrence and specific characteristics of EMIS in an adult woman, and the relevant literature is reviewed. Our report provides further information on EMIS.

Case report

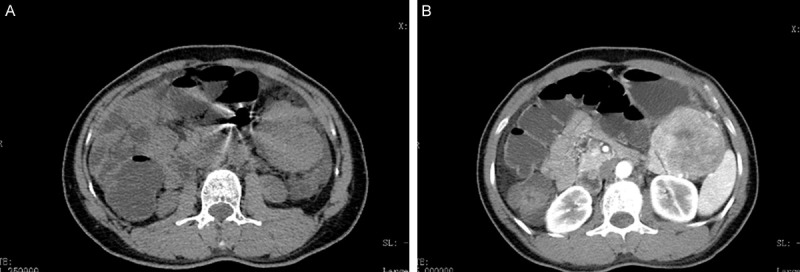

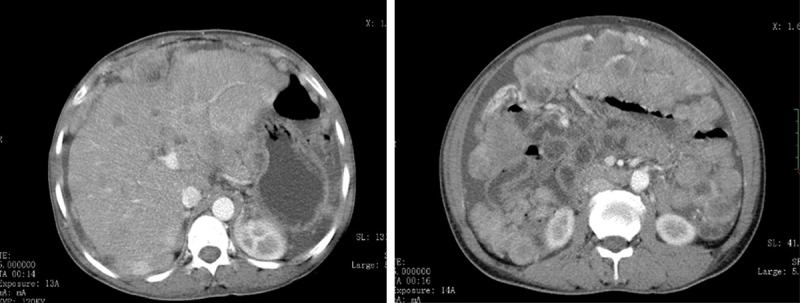

The report involves a 46-year-old female who was hospitalized due to left upper abdominal pain lasting for 3 months and abdominal distention lasting for 2 months. A CT examination showed a solid mass in the left upper intra-abdomen, which could not be distinguished from the stomach. When a strengthening scan was performed, the mass showed non-uniform intensification (Figure 1A and 1B). A few irregular nodules were seen below the mass, and some were fused into a mass. The larger one was about 5.6 cm×4.0 cm×5.2 cm in size. The mass also showed non-uniform intensification when a strengthening scan was performed.

Figure 1.

Computed tomography (CT) revealing a solid mass in the left upper intra-abdomen (A). When a strengthening scan was performed, the mass showed non-uniform intensification (B).

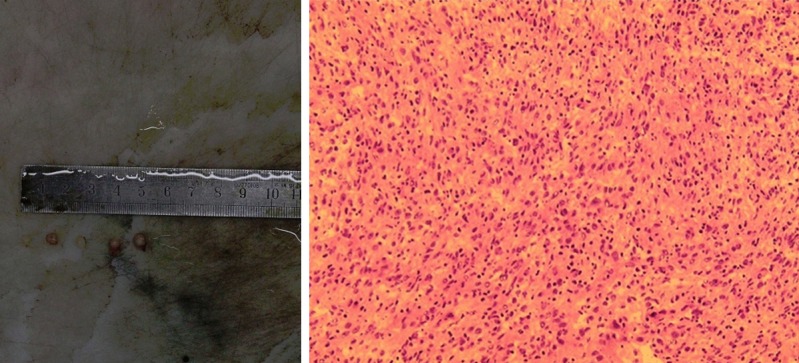

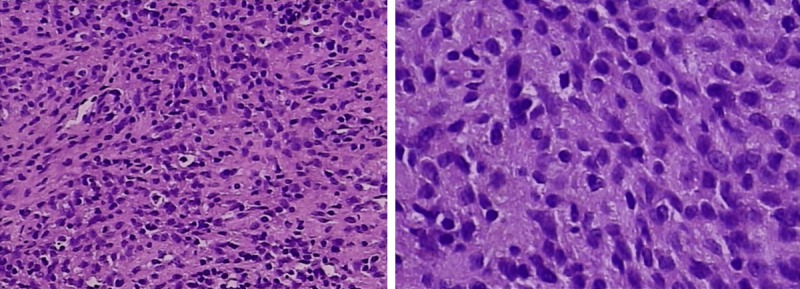

A laparotomy indicated that a tumor was detected in the left upper intra-abdomen with a size of 11 cm×6.5 cm×7 cm. It was nodular, encapsulated, and with moderate hardness and gray-white in the cut surface. Microscopically, the tumor cells were spindle-shaped or round like, with mitotic figures of 4/10 HPF. There was a large number of inflammatory cells infiltrated in the background, with more collagen bundles, and pleomorphic hyalinizing angiectasia. A small area of mucoid degeneration was found (left inferior phrenic). Multiple lymph nodes were involved by the tumor (Figure 2). Immunohistochemically, GFAP, vimentin, SMA, and CD163 were positive. The Ki67 index was approximately 20%. CD56, S-100, CDla, NF, NSE, Calponin, CD21, CD23, CD117, CD34, and Dog-1 were negative. This primary pathology finding provided a convincing diagnosis of the inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor (Figure 3). The tumor showed a sheet and nodular growth pattern, and the stromal mucus changed together with prominent infiltrated lymphocytes, neutrophils and eosinophils.

Figure 2.

Grossly, the huge tumor located in the left upper intra-abdomen, nodular, encapsulated, and with moderate hardness and gray-white in the cut surface. Microscopically, the tumor cells are spindle-shaped or round like.

Figure 3.

Immunohistochemically, GFAP, vimentin, SMA, and CD163 are positive. The Ki67 index was approximately 20%.

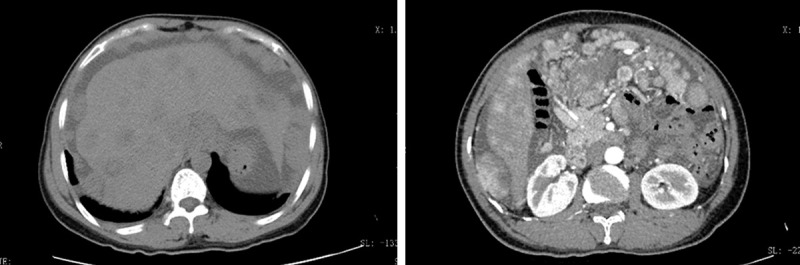

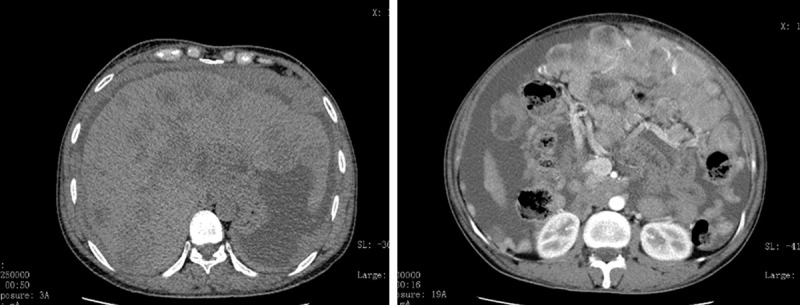

The patient did not have any additional treatment after the operation. Eleven months after the operation, because of abdominal pain, she received CT imaging, which displayed a recurrent intra-abdominal tumor, and multiple metastases were observed in her liver, ventral wall, abdominal cavity, pelvic cavity, and uterine appendages (Figure 4). Since the tumor was spreading all over the abdominal cavity and ALK staining of the tumor was positive (2p23 ALK gene rearrangement by immunohistochemistry), crizotinib was suggested as adjuvant therapy. Then crizotinib (200 mg) was administered to the patient twice a day orally. The patient’s previous clinical symptoms were significantly relieved, and the response evaluation reached a partial response (PR) (Figure 5). However, two months later, a CT examination revealed the progression of the disease (Figure 6). The patient failed to respond to the treatment with crizotinib. Accordingly, there was little guidance on how to treat EIMS after progression on crizotinib. According to the results of genetic testing, antiangiogenic therapy may be effective. Thus, we started treatment of giving anlotinib 12 mg qd for the full two weeks, and three weeks for a period. Unfortunately, the antivascular therapy achieved little effect. Due to the poor general condition of the patient, the follow-up treatment gave priority to symptomatic supportive treatment. The patient died of organ failure three months later.

Figure 4.

The tumor recurrence eleven months after the operation, and multiple metastases are observed in the liver, ventral wall, abdominal cavity, pelvic cavity, and uterine appendages.

Figure 5.

The response evaluation reached a partial response (PR) one month after crizotinib administration.

Figure 6.

CT examination reveals the progression of the disease (PD) three months after crizotinib.

Discussion

In 2011, Marino Enriquez et al. [2] described in detail the clinicopathological, immunohistochemical and genetic characteristics of 11 additional cases and named them EIMS to highlight both the distinct morphology and malignant behavior of this aggressive form of IMT. Clinically, EIMS mainly occurs among children and adolescents, although the overall age range varies greatly. Previous studies reported that the patients’ ages ranged from 7 months to 65 years, with an average age of 33.4 years [2-11]. As a rare malignant mesenchymal neoplasm, it is often found in the lung, abdominal/pelvic and retroperitoneal cavity, regardless of age [10].

In clinical practice, EIMS is a rapidly growing abdominal mass or thoracic nodule, which attracts medical attention when abdominal pain, ascites or pleural effusion occur. Cases of reported EIMS have ranged in size from 6 to 26 cm [2,5,12]. In some cases, general fatigue and weight loss are the primary clinical manifestations instead of abdominal pain and a palpable nodular lesion [13].

Since cases of EIMS are so rare, the diagnosis should be only made through a strict histological and clinical manifestation. Based on the previously reported cases, the common histological features of EIMS are abundant myxoid stroma with inflammatory infiltrating and plump round-to-epithelioid cell morphology. In most of the cases, frequent immunopositivity for ALK [2,5,12] and the RANBP2-ALK fusion gene [13] have also been identified.

ALK is a receptor tyrosine kinase gene located on chromosome 2p23. The rearrangement of the gene usually results in the high activity of the ALK protein, which is closely related to the expression of the ALK protein through immunohistochemistry [14]. In previous reports, RANBP2, tropomyosin 3 (TPM3), tropomyosin 4 (TPM4), clathrin heavy chain (CLTC), cysteinyl-tRNA synthetase (CARS), 5-aminoimidazole-4-carboxamide ribonucleotide for myltransferase/IMP cyclohydrolase (ATIC), and SEC31L1 have been identified to fuse with the ALK gene, and provide active promoters for the fusion gene [15-17]. Several reports have suggested that IMTs with RANBP2-ALK fusion usually exhibit an epithelioid/round cell morphology and follow a more aggressive clinical course [18,19]. In this case, we identified a 2p23 ALK gene rearrangement by immunohistochemistry.

The optimal therapy for EIMS has not been well established. Surgical resection is considered to be the mainstay of treatment. In view of the postoperative adjuvant therapy, the available experience is very limited. Most of the reported cases were treated with post-operative chemotherapy or radiotherapy, which seemed to have no significant effect in controlling the rapid recurrence [2,3,12,20,21]. Recently, an ALK inhibitor, crizotinib, has been applied in the treatment of EIMS with a certain effectiveness [2,5,12,21,22].

Thus, in the present case, crizotinib (200 mg) was administered to the patient twice a day orally.

The patient’s previous clinical symptoms were significantly relieved, and the response evaluation reached a partial response (PR), according to the Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST) version 1.1 (http://recist.eortc.org/recist-1-1-2/) (Figure 2) with slight adverse events. However, acquired resistance to the ALK inhibitor crizotinib seemed to be unavoidable. The patient was resistant to crizotinib after 2 months. Reportedly, in NSCLC, ALK-positive patients developed disease progression after receiving crizotinib for 8-10 months [23]. Gainor et al. [24] described the mechanisms of resistance in ALK-positive patients and found that many of the resistant samples had ALK resistant domain mutations. Chromophilicity is described as a resistance mechanism. Multiple closed chain rearrangements lead to the loss of the tumor suppressor’s gene function and the enhancement of carcinogenic fusion function [25]. Most mutations in ALK-positive cancers involve an ALK tyrosine kinase domain that targets drug resistance patterns [27]. In fact, each ALK tyrosine kinase inhibitor is associated with a particular pattern of ALK resistance mutations [26,27]. Another less common resistance is to amplify ALK [27].

A key problem is how to prevent the development of drug resistance to ALK inhibitors. Further studies are needed to be conducted among EIMS patients. Additionally, further drug development is imperative for both patient life expectancy and disease remission. PD-L1 expression in tumor cells is considered to be a predictive index of the tumor response to immunomodulatory therapies targeting the PD-1/PD-L1 pathway [28], as staining for the programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) is diffusely positive in the case of EIMS [29].

The expression of PD-L1 in EIMS indicates an immune check-point blockade, representing a novel anti-EIMS therapy.

Disclosure of conflict of interest

None.

References

- 1.Silva WPPD, Zavarez LB, Zanferrari FL, Schussel JL, Faverani LP, Jung JE, Sassi LM. Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor: rare manifestation in face. J Craniofac Surg. 2017;28:e751–e752. doi: 10.1097/SCS.0000000000003954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mariño-Enríquez A, Wang WL, Roy A, Lopez-Terrada D, Lazar AJ, Fletcher CD, Coffin CM, Hornick JL. Epithelioid inflammatory myofibroblastic sarcoma: an aggressive intra-abdominal variant of inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor with nuclear membrane or perinuclear ALK. Am J Surg Pathol. 2011;35:135–44. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e318200cfd5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Li J, Yin WH, Takeuchi K, Guan H, Huang YH, Chan JK. Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor with RANBP2 and ALK gene rearrangement: a report of two cases and literature review. Diagn Pathol. 2013;8:147. doi: 10.1186/1746-1596-8-147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Liu Q, Kan Y, Zhao Y, He H, Kong L. Epithelioid inflammatory myofibroblastic sarcoma treated with ALK inhibitor: a case report and review of literature. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2015;8:15328–32. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kimbara S, Takeda K, Fukushima H, Inoue T, Okada H, Shibata Y, Katsushima U, Tsuya A, Tokunaga S, Daga H, Okuno T, Inoue T. A case report of epithelioid inflammatory myofibroblastic sarcoma with RANBP2-ALK fusion gene treated with the ALK inhibitor, crizotinib. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2014;44:868–71. doi: 10.1093/jjco/hyu069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kurihara-Hosokawa K, Kawasaki I, Tamai A, Yoshida Y, Yakushiji Y, Ueno H, Fukumoto M, Fukushima H, Inoue T, Hosoi M. Epithelioid inflammatory myofibroblastic sarcoma responsive to surgery and an ALK inhibitor in a patient with panhypopituitarism. Intern Med. 2014;53:2211–4. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.53.2546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhou J, Jiang G, Zhang D, Zhang L, Xu J, Li S, Li W, Ma Y, Zhao A, Zhao Z. Epithelioid inflammatory myofibroblastic sarcoma with recurrence after extensive resection: significant clinicopathologic characteristics of a rare aggressive soft tissue neoplasm. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2015;8:5803–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wu H, Meng YH, Lu P, Ning HY, Hong L, Kang XL, Duan MG. Epithelioid inflammatory myofibroblastic sarcoma in abdominal cavity: a case report and review of literature. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2015;8:4213–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bai Y, Jiang M, Liang W, Chen F. Incomplete intestinal obstruction caused by a rare epithelioid inflammatory myofibroblastic sarcoma of the colon: a case report. Medicine (Baltimore) 2015;94:e2342. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000002342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yu L, Liu J, Lao IW, Luo Z, Wang J. Epithelioid inflammatory myofibroblastic sarcoma: a clinicopathological, immunohistochemical and molecular cytogenetic analysis of five additional cases and review of the literature. Diagn Pathol. 2016;11:67. doi: 10.1186/s13000-016-0517-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jiang Q, Tong HX, Hou YY, Zhang Y, Li JL, Zhou YH, Xu J, Wang JY, Lu WQ. Identification of EML4-ALK as an alternative fusion gene in epithelioid inflammatory myofibroblastic sarcoma. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2017;12:97. doi: 10.1186/s13023-017-0647-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kozu Y, Isaka M, Ohde Y, Takeuchi K, Nakajima T. Epithelioid inflammatory myofibroblastic sarcoma arising in the pleural cavity. Gen Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2014;62:191–4. doi: 10.1007/s11748-013-0204-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fu X, Jiang J, Tian XY, Li Z. Pulmonary epithelioid inflammatory myofibroblastic sarcoma with multiple bone metastases: case report and review of literature. Diagn Pathol. 2015;10:106. doi: 10.1186/s13000-015-0358-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cook JR, Dehner LP, Collins MH, Ma Z, Morris SW, Coffin CM, Hill DA. Anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK) expression in the inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor: a comparative immunohistochemical study. Am J Surg Pathol. 2001;25:1364–71. doi: 10.1097/00000478-200111000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lawrence B, Perez-Atayde A, Hibbard MK, Rubin BP, Dal Cin P, Pinkus JL, Pinkus GS, Xiao S, Yi ES, Fletcher CD, Fletcher JA. TPM3-ALK and TPM4-ALK oncogenes in inflammatory myofibroblastic tumors. Am J Pathol. 2000;157:377–84. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64550-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cools J, Wlodarska I, Somers R, Mentens N, Pedeutour F, Maes B, De Wolf-Peeters C, Pauwels P, Hagemeijer A, Marynen P. Identification of novel fusion partners of ALK, the anaplastic lymphoma kinase, in anaplastic large-cell lymphoma and inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2002;34:354–62. doi: 10.1002/gcc.10033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Debiec-Rychter M, Marynen P, Hagemeijer A, Pauwels P. ALK-ATIC fusion in urinary bladder inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2003;38:187–90. doi: 10.1002/gcc.10267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gleason BC, Hornick JL. Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumours: where are we now? J Clin Pathol. 2008;61:428–37. doi: 10.1136/jcp.2007.049387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chen ST, Lee JC. An inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor in liver with ALK and RANBP2 gene rearrangement: combination of distinct morphologic, immunohistochemical, and genetic features. Hum Pathol. 2008;39:1854–8. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2008.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ma Z, Hill DA, Collins MH, Morris SW, Sumegi J, Zhou M, Zuppan C, Bridge JA. Fusion of ALK to the Ran-binding protein 2 (RANBP2) gene in inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2003;37:98–105. doi: 10.1002/gcc.10177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Butrynski JE, D’Adamo DR, Hornick JL, Dal Cin P, Antonescu CR, Jhanwar SC, Ladanyi M, Capelletti M, Rodig SJ, Ramaiya N, Kwak EL, Clark JW, Wilner KD, Christensen JG, Jänne PA, Maki RG, Demetri GD, Shapiro GI. Crizotinib in ALK-rearranged inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:1727–33. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1007056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tothova Z, Wagner AJ. Anaplastic lymphoma kinase-directed therapy in inflammatory myofibroblastic tumors. Curr Opin Oncol. 2012;24:409–13. doi: 10.1097/CCO.0b013e328354c155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gainor JF, Shaw AT. Emerging paradigms in the development of resistance to tyrosine kinase inhibitors in lung cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2013;31:3987–96. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.45.2029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gainor JF, Dardaei L, Yoda S, Friboulet L, Leshchiner I, Katayama R, Dagogo-Jack I, Gadgeel S, Schultz K, Singh M, Chin E, Parks M, Lee D, DiCecca RH, Lockerman E, Huynh T, Logan J, Ritterhouse LL, Le LP, Muniappan A, Digumarthy S, Channick C, Keyes C, Getz G, Dias-Santagata D, Heist RS, Lennerz J, Sequist LV, Benes CH, Iafrate AJ, Mino-Kenudson M, Engelman JA, Shaw AT. Molecular mechanisms of resistance to first- and second-generation ALK inhibitors in ALK-rearranged lung cancer. Cancer Discov. 2016;6:1118–1133. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-16-0596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Parker BM, Parker JV, Lymperopoulos A, Konda V. A case report: pharmacology and resistance patterns of three generations of ALK inhibitors in metastatic inflammatory myofibroblastic sarcoma. J Oncol Pharm Pract. 2019;25:1226–1230. doi: 10.1177/1078155218781944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rotow J, Bivona TG. Understanding and targeting resistance mechanisms in NSCLC. Nat Rev Cancer. 2017;17:637–658. doi: 10.1038/nrc.2017.84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Attarian S, Rahman N, Halmos B. Emerging uses of biomarkers in lung cancer management: molecular mechanisms of resistance. Ann Transl Med. 2017;5:377. doi: 10.21037/atm.2017.07.18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Berger R, Rotem-Yehudar R, Slama G, Landes S, Kneller A, Leiba M, Koren-Michowitz M, Shimoni A, Nagler A. Phase I safety and pharmacokinetic study of CT-011, a humanized antibody interacting with PD-1, in patients with advanced hematologic malignancies. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:3044–51. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-4079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Du X, Gao Y, Zhao H, Li B, Xue W, Wang D. Clinicopathological analysis of epithelioid inflammatory myofibroblastic sarcoma. Oncol Lett. 2018;15:9317–9326. doi: 10.3892/ol.2018.8530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]