Abstract

Aim

This paper integrates clinical expertise to earlier research about the behaviours of the healthy, alert, full‐term infant placed skin‐to‐skin with the mother during the first hour after birth following a noninstrumental vaginal birth.

Method

This state‐of‐the‐art article forms a link within the knowledge‐to‐action cycle, integrating clinical observations and practice with evidence‐based findings to guide clinicians in their work to implement safe uninterrupted skin‐to‐skin contact the first hours after birth.

Results

Strong scientific research exists about the importance of skin‐to‐skin in the first hour after birth. This unique time for both mother and infant, individually and in relation to each other, provides vital advantages to short‐ and long‐term health, regulation and bonding. However, worldwide, clinical practice lags. A deeper understanding of the implications for clinical practice, through review of the scientific research, has been integrated with enhanced understanding of the infant's instinctive behaviour and maternal responses while in skin‐to‐skin contact.

Conclusion

The first hour after birth is a sensitive period for both the infant and the mother. Through an enhanced understanding of the newborn infant's instinctive behaviour, practical, evidence‐informed suggestions strive to overcome barriers and facilitate enablers of knowledge translation. This time must be protected by evidence‐based routines of staff.

Keywords: Breastfeeding, Clinical practice, Maternal behaviour, Newborn infant behaviour, Skin‐to‐skin contact

Key notes.

A lag exists between research knowledge and clinical practice surrounding skin‐to‐skin in the first hour after birth.

A mutual early sensitive period includes preprogrammed behaviours for bonding and other survival mechanisms, for example through the eye contact, suggesting long‐term implications.

The framework of the newborn infant's 9 stages creates an opportunity to understand the biological and physiological situation for the dyad, and clinical implications of practice during this sensitive time.

Introduction

The evidence supporting the practice of skin‐to‐skin contact after birth is robust, indicating multiple benefits for both mother and baby. The 2016 Cochrane Review supports using immediate or early skin‐to‐skin contact to promote breastfeeding 1. Advantages for the mother include earlier expulsion of the placenta 2, 3, reduced bleeding 3, increased breastfeeding self‐efficacy 4 and lowered maternal stress levels 5. It has been suggested that the rise in the mother's oxytocin during the first hour after birth is related to the establishment of mother–infant bonding 6, 7. Advantages for the baby include a decrease of the negative consequences of the ‘stress of being born’ 8, more optimal thermoregulation 9, continuing even in the first days 8 and less crying 10. Skin‐to‐skin contact has been shown to increase breastfeeding initiation and exclusive breastfeeding while reducing formula supplementation in hospital, leading to an earlier successful first breastfeed 2, 11, 12, as well as more optimal suckling 3, 13. The evidence supporting skin‐to‐skin the first hour is so compelling that the 2018 revision of the World Health Organization (WHO)/United Nations International Children's Emergency Fund (UNICEF) Ten Steps to Successful Breastfeeding that form the basis of the Baby‐Friendly Hospital Initiative. Step 4 states ‘Facilitate immediate and uninterrupted skin‐to‐skin contact and support mothers to initiate breastfeeding as soon as possible after birth’ 14 with the understanding that the newborn infant will self‐attach.

During this first hour after childbirth, both mother and newborn infant experience a special and unique time, a sensitive period 15, 16, which has been biologically predetermined, especially after vaginal birth. This is aided by the physiological state of each: the mother's high oxytocin levels and newborn infant's extremely high catecholamine levels.

Being in skin‐to‐skin contact with the mother after birth elicits the newborn infant's internal process to go through what could be called 9 instinctive stages: birth cry, relaxation, awakening, activity, rest, crawling, familiarization, suckling and sleeping 17 (Table 1).

Table 1.

Shows the nine stages

| Stages | Behaviours |

|---|---|

| 1. Birth cry | Intense cry just after birth, transition to breathing air. |

| 2. Relaxation stage | Infant rests. No activity of mouth, head, arms, legs or body. |

| 3. Awakening stage | Infant begins to show signs of activity. Small thrusts of head: up, down, from side‐to‐side. Small movements of limbs and shoulders. |

| 4. Active stage | Infant moves limbs and head, more determined movements. Rooting activity, ‘pushing’ with limbs without shifting body. |

| 5. Resting stage* | Infant rests, with some activity, such as mouth activity, sucks on hand. |

| 7. Familiarization | Infant has reached areola/nipple with mouth positioned to brush and lick areola/nipple. |

| 8. Suckling stage | Infant has taken nipple in mouth and commences suckling. |

| 9. Sleeping stage | Infant closes eyes and falls asleep. |

The Resting Stage could be interspersed with all the stages.

This process is suggested to contribute to an early coordination of infant's five senses: sight, hearing, touch, taste and smell, as well as movement 17, 18.

Whereas prolactin is the most important milk‐producing hormone, oxytocin plays a key role in maternal behaviour and bonding immediately after birth. In animal studies, for example, if an ewe is separated from her lamb soon after birth, she will reject the lamb when they later are reunited. Interestingly, it has been shown that simulating a birth through the birth channel at reunion of mother and lamb enhances oxytocin release in the mother ewe, resulting in her acceptance of her lamb. This illustrates that natural oxytocin facilitates the bonding between the ewe and the lamb during the first hour after birth 19.

In the human mother, a surge of oxytocin is released in the mother's blood vessels during the first hour after birth to contract the uterus, facilitate placental discharge and to decrease blood loss 6. Oxytocin released to the blood stream in this situation is likely to be paralleled by an intense firing of parvocellular oxytocin neurons in the brains, as Theodosis has shown in animal experiments 20, causing an increased maternal sensitivity for the young. In humans, this has been illustrated through the mother's desire to keep her infant close to her throughout the hospital stay if the newborn infant suckled or even just touched her nipple during the first hour while skin‐to‐skin 21.

The mother is attracted to the infant's smell, facilitating a chemical communication between the two 22, 23. This highlights the importance of a new mother's access to her newborn infant's bare head to smell her baby. This is an example of the early symbiotic biological relationship between the dyad 24, 25.

The newborn infant has high levels of catecholamine immediately after a normal, vaginal birth 10. These are highest closest to the time of birth, especially for the first thirty minutes. Catecholamines strengthen memory and learning.

In newborn infants less than 24 hours old, the odour of the mother's colostrum increases the amount of oxygenated haemoglobin over the olfactory cortex, as measured by near‐infrared spectroscopy. In addition, the closer to birth, the more oxygenated haemoglobin was observed over the olfactory cortex 26. This increased sensitivity for the odour of breastmilk, especially soon after the birth, indicates a physiologically based early sensitive period in the newborn infant. This reaction matches the mother's biologically based enhancements of the breast odour through the increase of the surface of the areola and Montgomery gland secretions during the corresponding time 27. Thus, the increased early sensitivity for the odour of breastmilk, in the presence of high levels of catecholamine which strengthens this memory, is indication of a physiologically based early sensitive period in the newborn infant.

Aim

The aim of this paper is to integrate clinical expertise to earlier research about the behaviours of the healthy, alert, full‐term infant placed skin‐to‐skin with the mother during the first hour after birth following a noninstrumental vaginal birth.

Method

This is a state‐of‐the‐art article integrating clinical observations and practice with evidence‐based findings to guide clinicians in their work to implement safe uninterrupted skin‐to‐skin contact the first hours after birth. This paper, presented from the nurse clinician perspective, is informed by the scientific literature around newborn infant behaviour and mother‐to‐infant interaction, in order to translate existing knowledge and facilitate clinician behaviour change. In this way, it forms a link within the knowledge‐to‐action cycle and offers the underlying implications of this important behaviour change to enhance the translation between the evidence and implementation through a deeper understanding of the newborn infant's instinctive behaviour while skin‐to‐skin immediately after birth.

This paper is organised around nine developmental stages of the newborn infant during skin‐to‐skin contact in the first hours after birth 17. It expands the understanding of each of these through the lens of the authors’ clinical expertise and research experience from direct observation of newborn infant behaviour. Expertise comes from experience as well as analysis of hundreds of hours of videotapes of newborn infants’ developing feeding behaviour in skin‐to‐skin contact 12, 17, 18, 21, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42. Additionally, the authors had the opportunity to improve skin‐to‐skin care after birth, both in vaginal and caesarean delivery at 10 hospitals in Egypt and the United States according to a 5‐day video‐ethnographic intervention. This methodology has five features: (i) a lecture educating staff (obstetricians, paediatricians, midwives, nurses and other staff at the delivery – and neonatal wards) about the theory behind the procedure of skin‐to‐skin care; (ii) practical application of the skin‐to‐skin procedure, with the American and Swedish team and staff working at the delivery ward together, to continue the educational process; (iii) videotaping the evolving process as the hospital staff work to implement the new procedures; (iv) conducting an interaction analysis workshop to review videotapes and discuss barriers and solutions; and (v) administering the continuing application of the procedure 12, 28.

Results

Before labour

Ideally, education related to the placement of the baby skin‐to‐skin with the mother should also have occurred as part of her antenatal care. When the mother and her companion(s) arrive at the birthing facility, a review of their understanding of the newborn infant's instinctive behaviours and the process of safe skin‐to‐skin immediately after birth should take place (Table 1). It has been our experience that parents are captivated by the newborn infant's instinctive behaviours and respond positively when they learn about the 9 stages and can identify the newborn infant's actions 32. Parents should also have an understanding about the importance of monitoring the newborn infant's position, breathing and safety. Providing the parents with a pamphlet or tear sheet or having a poster of the 9 instinctive stages somewhere in the birthing suite has been found to be helpful for the parents to follow the baby throughout the stages and recognise their newborn infant's ability. This also gives a clear role to the companion and provides both motivation to remain with the mother and newborn infant, and an additional opportunity for the baby's safety. Parents thereby have this additional knowledge and can prioritise focus on the newborn infant rather than distractive actions such as phone calls 43, 44, posting on the Internet, talking to friends or family in the room, which are behaviours that are best postponed until after this unique time.

Staff have the opportunity to protect this important, small window of time for the parents to follow their newborn infant's behavioural development. This creates a shelter for the mother and baby's right to not be separated 45, to stay skin‐to‐skin after birth until the newborn infant has suckled and/or fallen asleep. Interruption of skin‐to‐skin contact during the first two hours reduces the infant's chances of early breastfeed 13, 46.

Staff should also assure practical arrangements have been made for the experience of skin‐to‐skin. This includes ensuring that the mother's clothing has been arranged so it will be easy to remove and will allow access to the mother's chest immediately after the birth, being aware of any intravenous lines in relation to the sleeves of the mother's gown, etc. Regardless of the birthing position, the mother needs a comfortable and supportive position during the first hours while skin‐to‐skin with the newborn infant. Hospital protocol should be reviewed to ensure it reflects best practice.

The 9 Stages – A breastfeeding start led by the newborn infant

Stage 1 – The birth cry

This first stage is characterised by the initial birth cry, when the lungs expand for the first time as the newborn infant transitions to breathing, and other survival instincts (Fig. 1A). These behaviours could include the moro reflex, grimacing, coughing, lifting the full body from the mother's torso, abruptly opening the eyes and tension in the body. The baby's motions during the birth cry stage emanates from the drive to survive. During this extremely alert period, the newborn infant is able to make defensive movements with the hands to protect their airway, for example against a suction catheter or bulb.

Figure 1.

(A–I): Pictures of the 9 stages ©Healthy Children Project, Inc. Used with permission.

The initial birth cry, and the subsequent crying during the first minutes after the birth, has the effect of expectorating the airways of the amniotic fluid 47. In addition, extremely high catecholamine levels at birth help in absorbing liquid from the airways 48. The American Association of Pediatrics 49 and Academy of Gynecologists and Obstetricians (ACOG) 50 have strong statements about the ability of healthy full‐term babies to clear their own airways and successfully transition without the need of any form of suctioning. Research has shown that suctioning may disrupt the inborn sequential behaviours of the newborn infant 34. Interruption of the natural newborn behaviours immediately after birth could affect cell proliferation in the locus coeruleus in rats 51, with consequences of impaired locus coeruleus connected autism 52 and to stress‐induced fear‐circulatory disorders 53.

While transitioning the baby to the mother's chest, it is important to avoid compressing the baby's thorax, which could hamper breathing. Clinical practice should include gentle hands to hold the newborn infant in the drainage position (tilted with the head lower than the torso and the head slightly to the side) immediately after the birth, allowing the fluid to flow freely from the mouth and nose.

The comfortably positioned, semi‐reclined mother receives the baby, to hold prone, skin‐to‐skin. The mother's semi‐reclined position is conducive to the baby's breathing adaptation, in contrast to a horizontal position 54. If possible, the baby should be in a lengthwise position on the mother's body, with the head on the mother's chest, and above her breasts. The lengthwise mid‐chest position also emphasises the importance of the upcoming stages. Positioning the baby's mouth close to the mother's nipple would put the focus on immediate breastfeeding, which the newborn infant is not ready to do now.

Standard practice includes drying the baby's head and body with a clean, dry cloth to help maintain body temperature. The baby's face should initially be turned to the side, which facilitates free airways and monitoring of the baby's breathing. After settling in the skin‐to‐skin position with the mother, the baby's body should be covered with a dry cloth, leaving the face uncovered.

During a caesarean surgery, the newborn infant might be positioned horizontally above the drape instead of vertically. In this case, the newborn infant is placed across the mother's breasts. This position requires additional attention from the staff to watch the baby's breathing and to ensure that the newborn infant does not push or jump‐off of the mother.

Placement of the newborn infant skin‐to‐skin increases uterine contraction immediately after birth, increases the completeness of the delivered placenta and decreases uterine atony and excessive blood loss 3. Skin‐to‐skin also significantly decreases the duration of the third stage of labour 3.

Delayed cord clamping (>180 seconds after delivery) is recommended when compared to early cord clamping (>10 seconds after delivery). Delayed cord clamping reduced the risk of anaemia at 8 and 12 months in a group of high‐risk children. In addition, there was a possible positive effect in infant's health and development 55, 56. ‘From a physiological point of view the appropriate time for umbilical cord clamping in healthy full‐term infants is after the infant has aerated its lungs, commenced breathing and the pulmonary blood flow has increased to sustain ventricular preload and cardiac output’ 57. Deferred cord clamping is in line with recommendations from the World Health Organization 58.

Clinical practice shows that the umbilical cord should be left long, not clamped close to the newborn infant's belly, so that the newborn infant is not disturbed by the clamp, since clamps, and hard clamps especially, can be uncomfortable in a prone position. This can result in the babies lifting their body from the mother's chest, which reduces skin‐to‐skin contact and thus compromises the newborn infant's temperature. It can also cause a cry of discomfort.

Staff should create a teaching situation at their routine frequent observations of the baby during skin‐to‐skin contact, involving the parents in unobtrusive, gentle, close observation, ‘helping them understand and avoid potentially hazardous positions’ 59 during the first few hours after the birth. In addition, the nine stages offer an opportunity for staff to discuss the progress of the newborn infant and to ensure continued observation by the parents or attendants. The focus on following the newborn infant's progress through the nine instinctive stages results in a close examination of the baby by the mother's companion(s) and staff throughout the vulnerable first two hours. This may help to illuminate the capabilities and limitations of a specific baby, and thereby increase the safety during this important time. The safety of the newborn infant and mother is always the highest priority (Table 2).

Table 2.

Safe skin‐to‐skin care

| Safe Interactive Skin‐to‐Skin Contact in the First Hour After Birth |

|---|

| 1. Make sure that the mother is in a comfortable semi‐reclined position with support under her arms. |

| 2. After drying the newborn infant, lift the newborn infant gently to avoid compression of the thorax when placing the baby skin‐to‐skin. Put the baby prone, in a lengthwise position with the head on the mother's chest above the breast. |

| 3. Cover the baby with a dry blanket/towel. Leave the face visible. |

| 4. Make sure that the nose and mouth are not enveloped by the mother's breast or body or obscured by the blanket. Initially, the baby's head should be turned to the side. |

| 5. The newborn infant must have the opportunity to use its reflexes to lift the head so the nose and mouth can be free. This is of special concern if the mother has large and/or very soft breasts. |

| 6. The nipple must be accessible to the newborn infant. For some mothers, this may require positioning a towel or pillow under or on the side of the mother's breast. |

| 7. Show the parents how to support the breast to secure free airways especially during the time the baby starts searching for the breast. Verify understanding. |

| 8. Remind the parents to focus on the newborn infant and follow the newborn infant's early behavior, making sure that the parents follow the 9 stages. The other parent should be observant, not distracted by mobile phones, etc., during skin‐to‐skin. |

| 9. Extra attention may be required if the mother is affected by sedation after childbirth as well as during possibly postpartum suturing. The other parent should be aware of the situation and watch for the safety of the infant. |

| 10. Labor medications can affect the newborn infant, and hamper reflexes. The medications may impair the newborn infant's reflexes enough to prevent the ability to lift the head to protect itself from suffocation. Babies affected by labor medications must be constantly monitored. |

Adapted from The Swedish‐American Team for Baby Adapted Care of Health Infants in the First Hours after Birth, Widström, Svensson and Brimdyr, for Kom Ombo Hospital, Egypt, 2007 and from http://www.lof.se/patientsakerhet.

We have seen that when an unmedicated mother receives her newborn infant into her arms immediately after birth, she grasps the baby with confidence. She will often hold the baby gently around the torso, look at the baby and then bring the baby to her heart, allowing the newborn infant to lie quietly skin‐to‐skin with her, as both relax. When the mother has the newborn infant immediately after birth on her naked chest, it has a profound impact on her. A systematic review of mother's experiences of skin‐to‐skin contact includes overwhelming feelings of love, a natural experience that taught them how to be a mother, improved self‐esteem, and a way of knowing and understanding the infant 60. We have noticed that this simple act of the staff handing over the newborn infant to the mother supports early parental confidence.

If the mother has received analgesics during labour, special care must be taken to watch for free airways. For example, pethidine can cross the placenta and affect the newborn infant's breastfeeding behaviour negatively 33 and may specifically hamper the newborn infant's ability to lift the head 38 as well as infant's temperature and crying 39. Fentanyl given in the epidural space passes rapidly into maternal blood. A placental transfer of 90% has been measured by Moises 61. Fentanyl has been measured in the newborn infant's urine for at least 24 hours postpartum 62. Fentanyl exposure can depress the newborn infant's behaviour during the first hours after birth, especially the suckling behaviour in a dose‐dependent manner 29.

Stage 2 – Relaxation

During the relaxation stage (Fig. 1B), the newborn infant is still and quiet, making no movements (Fig. 1B). Clinical experience shows it is not possible to elicit a rooting reflex during the relaxation stage. The baby's sensory system seems to be depressed. From an evolutionary perspective, this silent and motionless period may be a way to hide from predators during a vulnerable time 17. When lying quietly on the mother's chest, the baby can hear the mother's heartbeat. This familiar sound from in utero seems to comfort the newborn infant after the rapid transition to extra‐uterine life.

It is suggested that the pressure on the head through the birth canal is the cause of extremely high catecholamine level after birth, a level 20 times higher than that of a resting adult 63. This high catecholamine concentration might partly be the cause of the higher pain threshold in the baby close to birth 64 and be a mirror of nature's way to relieve pain in the baby when passing through the birth canal. Consequently, the baby's temporarily impaired sensation at birth causes the relaxation stage – the baby has decreased sensitivity to the surroundings.

We have noticed that staff members exhibit concerns about the newborn infant's silent and relaxed state during this time. This stems from a lack of understanding of the baby's stage, often resulting in rubbing or massaging the newborn infant in a disruptive and vigorous manner, repositioning or lifting the baby from the mother. If, during the relaxation stage, the newborn infant is disturbed by the actions of the staff, the baby will react with crying, grimacing and protective reflexes.

If separated from their mother, babies exhibit a distinct separation distress call. This separation distress vocalisation in mammalian species that stops at reunion may be nature's way of keeping newborn infants warm with maternal body temperature. The baby's call at separation is thus a survival mechanism 65, 66.

Mammalian species, including human mothers, react to these separation distress calls and intuitively attempt to retrieve the newborn infant. In hospital settings, where the mother has limited control over her environment, we have noticed her straining to look at the infant who has been taken away and asking others about the state of the infant. (Fig. 2)

Figure 2.

Caesarean mother looking towards her baby ©Healthy Children Project, Inc. Used with permission.

It is possible to conduct the assessment of the APGAR score, as well as any other necessary assessments, on a healthy full‐term newborn infant without disturbing the infant, allowing skin‐to‐skin to continue uninterrupted. It is more effective and advantageous to assess the newborn infant when skin‐to‐skin with mother since babies are less likely to cry; they are more likely to remain warm and not waste energy.

If administration of vitamin K shot is a routine, this should occur soon after birth while the catecholamine levels are highest 10, preferably with the newborn infant skin‐to‐skin with the mother, as skin‐to‐skin contact has been shown to lower the baby's reaction to pain in the postpartum 67.

Stage 3 – Awakening

The awakening stage (Fig. 1C) is a transition from the relaxation stage to the activity stage. The baby makes small motions. Small movements of the head, face and shoulders gently ripple down through the arms to the fingers. The baby makes small mouth movements. They will gradually open their eyes during this stage, blinking repeatedly until the eyes are stable and focused (Fig. 1C).

Stage 4 – Activity

During the activity stage (Fig. 1D), the baby exhibits a greater range of motion throughout the head, body, arms and hands. The limbs move with greater determination; the baby may root and lift the head from the mother's chest. The fingers often begin the stage as fisted but may expand to massage, transfer tastes with a hand‐to‐nipple‐to‐mouth movement, catch the nipple and explore the mother's chest 17. Rooting also becomes more obvious during this stage 34.

The successive protrusion of the tongue continues throughout this stage. At the beginning of this stage, the newborn infant may have only moved the tongue within the mouth. During the activity stage, the baby will bring the tongue to the edge of the lips, then protrude beyond the lips, then protrude repeatedly beyond the lips 40. These tongue exercises, which may pave the way for later tongue behaviours, specifically suckling, can be affected by medications, such as pethidine 33.

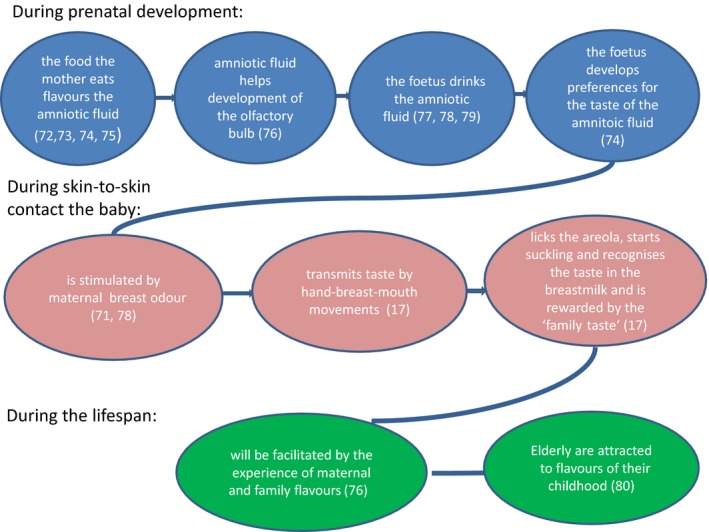

During pregnancy, the nipple has become more pigmented 68 and is easy for the newborn infant to discover (Fig. 1C). We have observed that soon after birth, the areola expands and takes a bulb‐like shape (Fig. 1G). The Montgomery glands also become more pronounced (Fig. 1G). The scent of areolar secretions has been linked to behavioural responses, such as head turning 69 and directional crawling in newborn infants 70. This release of the breast odour by the Montgomery glands is known to help the newborn infant find the nipple 17, 27, 69. The newborn infant recognises the scent of the mother's breast from the amniotic fluid 71, touches the breast and transmits the taste of the breast to the mouth (hand‐to‐breast‐mouth movements) 17. This stimulates rooting and crawling movements in the newborn infant to reach the nipple. The connection between the taste of amniotic fluid and the scent of the breast from the Montgomery glands highlights a biological survival mechanism – a pathway of flavour with lifelong consequences. (Fig. 3) (17, 71, 72, 73, 74, 75, 76, 77, 78, 79, 80) When knowing of this sensitive odour‐dependent mechanism, it might be wise not to interfere with unfamiliar hands.

Figure 3.

Pathway of flavours.

The infant has learned to recognise the mother's voice during intrauterine life 81.The infant's learning and memory skills are quite sophisticated; the foetus can learn to recognise a vowel from the surrounding language and is some days after birth able to discriminate this vowel from a vowel from a foreign language 82.

After the newborn infant has located the nipple by sight, the mother's voice will attract the baby's attention to her face. Arousal transfer between mother and 4‐ to 6‐month‐old babies is likely to happen through pupillary contagion (respond to pupil size with changes in one's own) is fundamental for social and emotional development 83. Interestingly, it is described in a paediatric essay that ‘immediately after birth the newborn's eyes become wide open, usually with large pupils’ 63. When skin‐to‐skin with the mother after birth and free to safely move, the newborn infant searches for eye contact with the mother around half an hour after birth 17 (Fig. 1E). We suggest that infant–maternal bonding through pupillary contagion may start early after birth as our clinical experience is that mothers often recall the first moment of eye‐to‐eye contact as unforgettable. The complex experiences of the newborn infant during the first hour encompass more than simply a journey to the breast; the opportunity for eye contact emphasises the importance of parents and staff valuing instinctive behaviour during this time, and the avoidance of interruptions.

Stage 5 – Resting

The resting stage (Fig. 1E) is intertwined with all of the other stages. A baby may stop or start during any of the stages to rest, and then continue with that same stage, or move on to the next 12, 84. The baby could be lying still sucking on fingers or just gazing at the nipple. The eyes may be open or closed.

It is important to value the resting stage and not worry that the baby is done and has not been successful with the process of the first hour. We have seen this stage being misinterpreted by parents or staff, resulting in the newborn infant being removed from skin‐to‐skin with the mother in favour of other routine care. It is vital to allow the newborn infant to take these pauses throughout the first hour or so without being interrupted or separated, remembering that this stage is naturally interspersed throughout other stages. Research about adult ‘awake rest’ points to the importance of this time to the consolidation of memories, and it's contribution to learning 85. This could be applicable to the newborn infant's rest during the first hour as well 41. Separation causes a critical break of the stages 31. If the newborn infant is separated from the mother, even if the infant is returned, the newborn infant might need to begin again at the first stage – crying and relaxing before beginning to progress through the stages again, which might take some time. The likelihood increases that the newborn infant may not be able to go through all the stages before needing to sleep, compromising the possibility to suckle, Stage 8.

Stage 6 – Crawling

The crawling stage (Fig. 1F) could include crawling, leaping, sliding, bulldozing or many other interesting names of ways to move from the position between the breasts to a position very close to the nipple. Sometimes this process is so subtle that parents and staff are surprised to notice that the baby has made its way over to the breast. Other times, the baby may make strong and overt motions, collecting the attention of everyone in the room. The evolutionary purpose behind the newborn infant's innate so‐called stepping reflex becomes clear as the newborn infant crawls to the mother's breast. The movements of these steps of the feet over the mother's uterus may contribute to the contractions of the uterus, and the decreased time to expel the placenta 2, 3 and decreased blood loss 3 during skin‐to‐skin.

During this process, it is important to protect the newborn infant's effort to reach the breast, with the intention not to lift or turn the baby's body. Placing a towel or pillow under the mother's arms is important during this stage, since the newborn infant will be travelling over to one side of the chest and therefore (in many settings) close to the edge of the bed 18. This support can help the newborn infant to reach the nipple without becoming exhausted by unnecessary sliding in the wrong direction. It is also important for parents to be aware of the travelling process, since they may try to reorient the baby back to the middle of the chest, to keep the newborn infant from the edges of the bed. Support under the mother's arms may also allow the nipple to remain in an area easy for the baby to find and grasp. A mother might use her own palm to arrange the breast as well. A baby needs to use the feet to achieve crawling, and sometimes the feet are in a less than ideal position. They may be off the side of the mother's body or pushing in the air. In those cases, it may be helpful if the mother puts her hand under the newborn infant's foot to give the baby something to push against in order to move towards the breast.

Stage 7 – Familiarization

Since the baby is prone on a semi‐reclined mother, the alert newborn infant has the control over their experience, rather than being placed in a dependent position by the mother Fig. 1G). To reach the breast, it must be possible for the baby to manoeuvre into an appropriate position. When approaching the breast the newborn infant performs specific soliciting calls to mother – a short clinging call that usually results in a gentle response from the mother. The frequency of these sounds increases as the newborn infant gets closer to the mother's nipple 17. The odours from the mother's breast are likely to be inducing this response. Parents respond to the newborn infant's soliciting 42.

During the familiarization stage (Fig. 1G), the baby becomes familiar with the breast by licking the nipple and areola. This period could last 20 minutes or more. The newborn infant massages the breast, which increases the mother's oxytocin levels 35 and shapes the nipple by licking. During this stage, it is evident that the baby is smelling and tasting, and previous actions become more vigorous and more coordinated. Therefore, it is important not to interfere or introduce odours from unfamiliar hands.

The baby continues with tongue activity during this stage, now more overtly related to eventual breastfeeding, by licking above and below the nipple. The baby may make noises with the mouth and lips, like smacking sounds, during this stage. The breast and nipple are shaped by the massaging and licking actions of the newborn infant. The newborn infant is preparing the tongue, breast and nipple for the moment of attachment and suckling.

The actions of the tongue inform the staff of the newborn infant's coordination of the tongue with the rooting reflex, and the ability to move the tongue to the bottom of the mouth, curved and thin. The newborn infant needs to practice this coordination of the rooting‐tongue reflex 36. Staff and parents should allow the baby the time needed to practice this coordination during this stage; the newborn infant is perfecting many important oral‐motor functions. This learning is vital as the newborn infant initiates the suckling process.

There is often a resting stage between the familiarization stage and the suckling stage, which unfortunately can make parents and staff prone to (so‐called) help the newborn infant to the breast.

It is also common for the baby to attach, suck once or twice, and then disengage. The newborn infant will be conducting a normal step of the familiarization Stage, but it may look to staff like the newborn infant is unable to attach. The baby must thus be allowed to do these moves to adjust into an instinctive position. This is conducive to the newborn infant's chin making an initial contact with the mother's breast as the baby endeavours to catch the nipple. ‘Chin‐first contact’ is associated with sustained deep, rhythmical suckling 86.

In a study of babies who had later been diagnosed with significant latch problems, the majority of mothers reported that the newborn infant had been forced to latch to his mother's breast. According to the mothers, the babies screamed, acted in a panicky way, exhibited avoidance behaviours and had other strong reactions against the forceful treatment 87. It has also been shown that mothers who had this type of so‐called help have a more negative experience of the first breastfeeding 88 and breastfeed for a shorter time 88, 89.

If infants with an aversive behaviour are allowed to peacefully go through the stages in skin‐to‐skin contact at a later time, they may successfully reach the nipple, attach to the nipple by themselves and start suckling. This could happen even weeks after birth if not possible earlier 87. This is a promising way to calmly solve breastfeeding problems, especially since a new study shows that breastfeeding is associated with decreased childhood maltreatment 90.

Stage 8 – Suckling

The newborn infant attaches to the nipple during this stage and successfully breastfeeds (Fig. 1H). When babies self‐attach, they are positioning the wide‐open mouth appropriately on the areola and nipple, protecting against sore nipples. It is interesting to note that the hands, which have been so busy, often stop moving once suckling begins 35; the eyes, which have been looking at the breast, the mother and the room, often become focused after attaching.

During this first hour, when the unmedicated baby self‐attaches, it is a perfect first breastfeeding, although the infant will continue to readjust until satisfied with the latch. The newborn infant does not need help to adjust the latch. Babies who self‐attach during the first hour after birth have few problems with breastfeeding, latch and milk transfer 13. Skin‐to‐skin in the first hour strengthens the mother's self‐confidence, including decreasing the concerns about having enough milk 4. When babies are placed skin‐to‐skin with the mother, they have more optimal blood glucose levels. Both skin‐to‐skin and the suckling contribute to this effect 91. Thus, this reduces the risk of supplementation.

Medicated babies can successfully go through the nine stages and self‐attach. However, there is increasing evidence concerning the negative consequences of certain medications such as fentanyl and oxytocin, on success with breastfeeding 29. Parents and staff must take into account the consequences when considering amount, timing and choice of specific labour medications.

Stage 9 – Sleeping

Towards the end of suckling, about an hour and a half after birth, the newborn infant becomes drowsy and falls asleep (Fig. 1I). The oxytocin, released in both mother and infant by suckling, triggers the release of gastrointestinal (GI) hormones, including cholecystokinin (CCK) and gastrin. The high level of CCK in both mother and newborn infant will cause a relaxing and satisfying postprandial sleep 37. The GI activity will also improve maternal and infant nutritional absorption. The advantages, and the feel‐good effect, will continue at each breastfeeding session.

If the mother and newborn infant were unable to experience these first hours together, or if the newborn infant did not self‐attach before falling asleep, the dyad should have the opportunity to stay skin‐to‐skin as much as possible. If separation occurs, hand expression of milk within the first hour after birth enhances milk production 92. The partner can also spend time skin‐to‐skin with a new baby if separation from the mother is necessary 42.

When the baby is alert and shows signs of readiness to feed, the processes of finding the mother's breast when skin‐to‐skin usually happen more quickly in the postpartum period than soon after birth. One reason for this is that the initial stages of a birth cry, relaxation and awakening are associated with the situation and hormonal status unique to the time immediately after birth. Later after birth, the baby has more control over his body and movements.

Understanding the stages, and the breastfeeding behaviours of the newborn infant, is indeed, reassuring to the parents, even in the postpartum ward.

There have been discussions about a possible relationship between skin‐to‐skin contact and Sudden Unexpected Postnatal Collapse (SUPC) 43. The background to SUPC is multifactorial. However, one of the common causes of the collapse seems to be respiratory distress 44, 93, 94, 95. The possibility of labour medications affecting the newborn infant adversely is not highlighted in the Sudden Unexpected Postnatal Collapse (SUPC) literature. 43, 96, 97. The majority of the cases occur in early skin‐to‐skin care, without observance of the child, or when sleeping with accidentally covered respiratory tract 98, 99. A review of Sudden Unexpected Early Neonatal Deaths (SUENDs) in Sweden shows that a higher incidence of SUENDs was reported before the practice of early skin‐to‐skin contact was introduced 100, 101. Staff need to be aware of the importance of safe skin‐to‐skin, including the close observation of the newborn infant's airways (Table 2).

Possible long‐term benefits of skin‐to‐skin contact

Immediate skin‐to‐skin contact provides the initial colonisation of the baby's microbiome outside of the mother, a swarming of the mother's skin bacteria. The microbial colonisation of the infant begins before birth and continues through the birth canal. This is one of the reasons the newborn infant should not be washed during this time. Colonisation after caesarean surgery does not match vaginal colonisation 102; skin‐to‐skin may be of extra importance in these cases. As the hour progresses, the first tastes of colostrum will provide vital sustenance to the infant's developing gut microbiota, which has been implicated in the expression of genes 103. Evolving research on epigenetics and the microbiome highlights the importance of the optimal microbiome 104, enhanced by breastfeeding, which has been implicated in long‐term health, including decreased obesity and metabolic diseases 103.

In a longitudinal study, it was found that the mother's breast temperature increases when mother and newborn infant are in skin‐to‐skin contact, resulting in an increase of newborn infant's foot temperature 8. The warmer foot temperature is an indication of the decrease of the negative effect of the ‘stress of being born’ that is associated with skin‐to‐skin. Those mothers who hold their babies skin‐to‐skin after birth were rated as ‘less rough’ when latching and stimulating their babies during breastfeeding at day 4 postpartum 105. Skin‐to‐skin was also linked to improved mother/infant mutuality one year later. Skin‐to‐skin after birth also positively influenced the infant's self‐regulation at one year 106. Self‐regulation is a part of the concept of self‐control.

Interestingly, Moffitt et al. showed that if a child has good self‐control at the age of 4, this has consequences into adulthood, in terms of increased education and income and decreased drug addiction and criminal behaviours as measured at 30 years of age, compared to those with low self‐control at four years of age, among a cohort of 1,000 children 107. Thus, skin‐to‐skin contact after birth may contribute to positive long‐term consequences.

From the beginning, biological processes during the first hour after birth ensure survival of the mother and infant. This sensitive period has an emotional consequence on the mother's understanding of the newborn infant, enhancing bonding. Humans are resilient, and there are opportunities to bond and breastfeed even when the experience immediately after the birth is less than optimal. For example, even days and months after the birth, the infant will exhibit these same instinctive breastfeeding behaviours, with the potential to overcome early breastfeeding problems. But this sensitive period immediately after birth must be recognised and valued, both by parents and staff, to provide the opportunity for this unique experience. It is vital not to interrupt these natural behaviours, as they form nature's basis for attachment, and support the mother's confidence in her infant's inborn capability. This may have significant consequences for the parent's understanding of the baby throughout childhood, protecting the child from parental roughness and laying a foundation for the child's self‐regulation and self‐control.

Conclusion

A sensitive period of the newborn infant coincides with mother's sensitive period during the first hour after birth. This is a unique situation for both, individually and in relation to each other, and must be protected by evidence‐based routines of hospital staff. Clinical expertise, together with systematic evidence, combines to enhance the understanding of the best practice of skin‐to‐skin care in the first hours after birth. Hospital guidelines must support and enhance this important time.

Funding

The study did not receive any specific funding.

Conflicts of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- 1. Moore ER, Bergman N, Anderson GC, Medley N. Early skin‐to‐skin contact for mothers and their healthy newborn infants. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2016; 11: CD003519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Marín Gabriel MA, Llana Martín I, López Escobar A, Fernández Villalba E, Romero Blanco I, Touza Pol P. Randomized controlled trial of early skin‐to‐skin contact: effects on the mother and the newborn. Acta Paediatr Oslo Nor 1992; 2010: 1630–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Essa RM, Abdel Aziz Ismail NI. Effect of early maternal/newborn skin‐to‐skin contact after birth on the duration of third stage of labor and initiation of breastfeeding. J Nurs Educ Pract 2015; 5 Available from: http://www.sciedu.ca/journal/index.php/jnep/article/view/5698 [Google Scholar]

- 4. Aghdas K, Talat K, Sepideh B. Effect of immediate and continuous mother‐infant skin‐to‐skin contact on breastfeeding self‐efficacy of primiparous women: a randomised control trial. Women Birth J Aust Coll Midwives 2014; 27: 37–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Handlin L, Jonas W, Petersson M, Ejdebäck M, Ransjö‐Arvidson A‐B, Nissen E, et al. Effects of sucking and skin‐to‐skin contact on maternal ACTH and cortisol levels during the second day postpartum‐influence of epidural analgesia and oxytocin in the perinatal period. Breastfeed Med Off J Acad Breastfeed Med 2009; 4: 207–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Nissen E, Lilja G, Widström AM, Uvnäs‐Moberg K. Elevation of oxytocin levels early post partum in women. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 1995; 74: 530–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Winberg J. Mother and newborn baby: mutual regulation of physiology and behavior–a selective review. Dev Psychobiol 2005; 47: 217–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Bystrova K, Widström AM, Matthiesen AS, Ransjö‐Arvidson AB, Welles‐Nyström B, Wassberg C, et al. Skin‐to‐skin contact may reduce negative consequences of “the stress of being born”: a study on temperature in newborn infants, subjected to different ward routines in St. Petersburg. Acta Paediatr Oslo Nor 1992; 2003: 320–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Beiranvand S, Valizadeh F, Hosseinabadi R, Pournia Y. The effects of skin‐to‐skin contact on temperature and breastfeeding successfulness in full‐term newborns after cesarean delivery. Int J Pediatr 2014; 2014: 1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Hägnevik K, Faxelius G, Irestedt L, Lagercrantz H, Lundell B, Persson B. Catecholamine surge and metabolic adaptation in the newborn after vaginal delivery and caesarean section. Acta Paediatr Scand 1984; 73: 602–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Bramson L, Lee JW, Moore E, Montgomery S, Neish C, Bahjri K, et al. Effect of early skin‐to‐skin mother–infant contact during the first 3 hours following birth on exclusive breastfeeding during the maternity hospital stay. J Hum Lact Off J Int Lact Consult Assoc 2010; 26: 130–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Crenshaw JT, Cadwell K, Brimdyr K, Widström A‐M, Svensson K, Champion JD, et al. Use of a video‐ethnographic intervention (PRECESS Immersion Method) to improve skin‐to‐skin care and breastfeeding rates. Breastfeed Med Off J Acad Breastfeed Med 2012; 7: 69–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Righard L, Alade MO. Effect of delivery room routines on success of first breast‐feed. Lancet 1990; 336: 1105–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. World Health Organization . Implementation guidance: protecting, promoting and supporting breastfeeding in facilities providing maternity and newborn services – the revised Baby‐friendly Hospital Initiative. Geneva; 2018. Report No.: CC BY‐NC‐SA 3.0 IGO.

- 15. Klaus MH, Jerauld R, Kreger NC, McAlpine W, Steffa M, Kennell JH. Maternal attachment: importance of the first post‐partum days. N Engl J Med 1972; 286: 460–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kennell JH, Trause MA, Klaus MH. Evidence for a sensitive period in the human mother In: Porter R, O'Connor M, editos. Novartis Foundation Symposia. Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, 2008: 87–101. Available at: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/9780470720158.ch6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Widström A‐M, Lilja G, Aaltomaa‐Michalias P, Dahllöf A, Lintula M, Nissen E. Newborn behaviour to locate the breast when skin‐to‐skin: a possible method for enabling early self‐regulation. Acta Paediatr Oslo Nor 1992; 2011: 79–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Brimdyr K, Wiström AM, Svensson K. Skin to Skin in the First Hour after Birth: Practical advice for staff after vaginal and cesarean birth [DVD]. Sandwich, MA, USA: Healthy Children Project, Inc., 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Keverne EB, Levy F, Poindron P, Lindsay DR. Vaginal stimulation: an important determinant of maternal bonding in sheep. Science 1983; 219: 81–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Theodosis DT, Chapman DB, Montagnese C, Poulain DA, Morris JF. Structural plasticity in the hypothalamic supraoptic nucleus at lactation affects oxytocin‐, but not vasopressin‐secreting neurones. Neuroscience 1986; 17: 661–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Widström AM, Wahlberg V, Matthiesen AS, Eneroth P, Uvnäs‐Moberg K, Werner S, et al. Short‐term effects of early suckling and touch of the nipple on maternal behaviour. Early Hum Dev 1990; 21: 153–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Fleming AS, Corter C, Franks P, Surbey M, Schneider B, Steiner M. Postpartum factors related to mother's attraction to newborn infant odors. Dev Psychobiol 1993; 26: 115–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Corona R, Lévy F. Chemical olfactory signals and parenthood in mammals. Horm Behav 2015; 68: 77–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Nelson EE, Panksepp J. Brain substrates of infant‐mother attachment: contributions of opioids, oxytocin, and norepinephrine. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 1998; 22: 437–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Raineki C, Pickenhagen A, Roth TL, Babstock DM, McLean JH, Harley CW, et al. The neurobiology of infant maternal odor learning. Braz J Med Biol Res Rev Bras Pesqui Medicas E Biol 2010; 43: 914–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Bartocci M, Winberg J, Ruggiero C, Bergqvist LL, Serra G, Lagercrantz H. Activation of olfactory cortex in newborn infants after odor stimulation: a functional near‐infrared spectroscopy study. Pediatr Res 2000; 48: 18–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Varendi H, Porter RH, Winberg J. Does the newborn baby find the nipple by smell? Lancet Lond Engl 1994; 344: 989–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Brimdyr K, Widström A‐M, Cadwell K, Svensson K, Turner‐Maffei C. A realistic evaluation of two training programs on implementing skin‐to‐skin as a standard of care. J Perinat Educ 2012; 21: 149–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Brimdyr K, Cadwell K, Widström A‐M, Svensson K, Neumann M, Hart EA, et al. The association between common labor drugs and suckling when skin‐to‐skin during the first hour after birth. Birth Berkeley Calif 2015; 42: 319–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Cadwell K, Brimdyr K, Phillips R. Mapping, measuring, and analyzing the process of skin‐to‐skin contact and early breastfeeding in the first hour after birth. Breastfeed Med Off J Acad Breastfeed Med 2018; 13(7): 485–492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Brimdyr K, Cadwell K, Stevens J, Takahashi Y. An implementation algorithm to improve skin‐to‐skin practice in the first hour after birth. Matern Child Nutr 2018; 14: e12571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Brimdyr K, Widström A‐M. The Magical Hour: Holding your baby skin to skin for the first hour after birth [DVD]. Sandwich, MA, USA: Healthy Children Project, Inc., 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Nissen E, Lilja G, Matthiesen AS, Ransjö‐Arvidsson AB, Uvnäs‐Moberg K, Widström AM. Effects of maternal pethidine on infants’ developing breast feeding behaviour. Acta Paediatr Oslo Nor 1992; 1995: 140–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Widström AM, Ransjö‐Arvidson AB, Christensson K, Matthiesen AS, Winberg J, Uvnäs‐Moberg K. Gastric suction in healthy newborn infants. Effects on circulation and developing feeding behaviour. Acta Paediatr Scand 1987; 76: 566–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Matthiesen AS, Ransjö‐Arvidson AB, Nissen E, Uvnäs‐Moberg K. Postpartum maternal oxytocin release by newborns: effects of infant hand massage and sucking. Birth Berkeley Calif 2001; 28: 13–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Widström AM, Thingström‐Paulsson J. The position of the tongue during rooting reflexes elicited in newborn infants before the first suckle. Acta Paediatr Oslo Nor 1992; 1993: 281–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Uvnäs‐Moberg K, Widström AM, Marchini G, Winberg J. Release of GI hormones in mother and infant by sensory stimulation. Acta Paediatr Scand 1987; 76: 851–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Nissen E, Widström AM, Lilja G, Matthiesen AS, Uvnäs‐Moberg K, Jacobsson G, et al. Effects of routinely given pethidine during labour on infants’ developing breastfeeding behaviour. Effects of dose‐delivery time interval and various concentrations of pethidine/norpethidine in cord plasma. Acta Paediatr Oslo Nor 1992 1997; 86: 201–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Ransjö‐Arvidson AB, Matthiesen AS, Lilja G, Nissen E, Widström AM, Uvnäs‐Moberg K. Maternal analgesia during labor disturbs newborn behavior: effects on breastfeeding, temperature, and crying. Birth Berkeley Calif 2001; 28: 5–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Brimdyr K, Widström AM, Cadwell K, Svensson K. Analysis of newborn tongue behavior as related to intrapartum epidural fentanyl exposure. 16th ISRHML Conference Breastfeeding and the Use of Human Milk, Science and Practice; 2012; Trieste, Italy.

- 41. Cadwell K, Brimdyr K. Intrapartum administration of synthetic oxytocin and downstream effects on breastfeeding: elucidating physiologic pathways. Ann Nurs Res Pr 2017; 2: 1024. [Google Scholar]

- 42. Velandia M, Matthisen A‐S, Uvnäs‐Moberg K, Nissen E. Onset of vocal interaction between parents and newborns in skin‐to‐skin contact immediately after elective cesarean section. Birth Berkeley Calif 2010; 37: 192–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Herlenius E, Kuhn P. Sudden unexpected postnatal collapse of newborn infants: a review of cases, definitions, risks, and preventive measures. Transl Stroke Res 2013; 4: 236–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Feldman‐Winter L, Goldsmith JP, Committee on fetus and newborn, Task force on sudden infant death syndrome . Safe sleep and skin‐to‐skin care in the neonatal period for healthy term newborns. Pediatrics 2016; 138: e20161889–e20161889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Convention on the Rights of the Child [Internet]. UN General Assembly; 1989 Nov. (United Nations, Treaty Series, vol. 1577, p. 3). Available at: http://www.refworld.org/docid/3ae6b38f0.html

- 46. Robiquet P, Zamiara P‐E, Rakza T, Deruelle P, Mestdagh B, Blondel G, et al. Observation of skin‐to‐skin contact and analysis of factors linked to failure to breastfeed within 2 hours after birth. Breastfeed Med 2016; 11: 126–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Faxelius G, Hägnevik K, Lagercrantz H, Lundell B, Irestedt L. Catecholamine surge and lung function after delivery. Arch Dis Child 1983; 58: 262–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Lagercrantz H. The stress of being born. Sci Am 1986; 254: 100–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Wyckoff MH, Aziz K, Escobedo MB, Kapadia VS, Kattwinkel J, Perlman JM, et al. Part 13: Neonatal Resuscitation: 2015 American Heart Association Guidelines Update for Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care (Reprint). Pediatrics 2015; 136: S196–218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Committee Opinion No. 689. Delivery of a Newborn With Meconium‐Stained Amniotic Fluid [Internet]. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists; 2017 p. 129:e33–4. Available at: https://www.acog.org/Clinical-Guidance-and-Publications/Committee-Opinions/Committee-on-Obstetric-Practice/Delivery-of-a-Newborn-With-Meconium-Stained-Amniotic-Fluid. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 51. Duarte ECW, de Azevedo MS, Pereira GAM, Fernandes MD, Lucion AB. Intervention with the mother–infant relationship reduces cell proliferation in the Locus Coeruleus of female rat pups. Behav Neurosci 2017; 131: 83–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Mehler MF, Purpura DP. Autism, fever, epigenetics and the locus coeruleus. Brain Res Rev 2009; 59: 388–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Bracha HS, Garcia‐Rill E, Mrak RE, Skinner R. Postmortem locus coeruleus neuron count in three american veterans with probable or possible war‐related PTSD. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 2005; 17: 503–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Erlandsson K, Christensson K, Dsilna A, Jnsson B. Do caregiving models after cesarean birth influence the infants’ breathing adaptation and crying? A pilot study. J Child Young Peoples Nurs 2008; 2: 7–12. [Google Scholar]

- 55. Andersson O, Hellström‐Westas L, Andersson D, Domellöf M. Effect of delayed versus early umbilical cord clamping on neonatal outcomes and iron status at 4 months: a randomised controlled trial. BMJ 2011; 343: d7157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Kc A, Rana N, Målqvist M, Jarawka Ranneberg L, Subedi K, Andersson O. Effects of delayed umbilical cord clamping vs early clamping on anemia in infants at 8 and 12 months: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Pediatr 2017; 171: 264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Kluckow M, Hooper SB. Using physiology to guide time to cord clamping. Semin Fetal Neonatal Med 2015; 20: 225–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Guideline: Delayed Umbilical Cord Clamping for Improved Maternal and Infant Health and Nutrition Outcomes [Internet]. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2014. (WHO Guidelines Approved by the Guidelines Review Committee). Available at: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK310511/ [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Fleming PJ. Unexpected collapse of apparently healthy newborn infants: the benefits and potential risks of skin‐to‐skin contact. Arch Dis Child ‐ Fetal Neonatal Ed 2012; 97: F2–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Anderzén‐Carlsson A, Lamy ZC, Eriksson M. Parental experiences of providing skin‐to‐skin care to their newborn infant—Part 1: A qualitative systematic review. Int J Qual Stud Health Well‐Being 2014; 9: 24906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Moisés ECD, de Barros Duarte L, de Carvalho Cavalli R, Lanchote VL, Duarte G, da Cunha SP. Pharmacokinetics and transplacental distribution of fentanyl in epidural anesthesia for normal pregnant women. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 2005; 61: 517–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Moore A, el‐Bahrawy A, Hatzakorzian R, Li‐Pi‐Shan W. Maternal epidural fentanyl administered for labor analgesia is found in neonatal urine 24 hours after birth. Breastfeed Med 2016; 11: 40–1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Lagercrantz H. The good stress of being born. Acta Paediatr 2016; 105: 1413–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Bergqvist LL, Katz‐Salamon M, Hertegård S, Anand KJS, Lagercrantz H. Mode of delivery modulates physiological and behavioral responses to neonatal pain. J Perinatol 2009; 29: 44–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Christensson K, Cabrera T, Christensson E, Uvnäs‐Moberg K, Winberg J. Separation distress call in the human neonate in the absence of maternal body contact. Acta Paediatr Oslo Nor 1992; 1995: 468–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Michelsson K, Christensson K, Rothgänger H, Winberg J. Crying in separated and non‐separated newborns: sound spectrographic analysis. Acta Paediatr Oslo Nor 1992; 1996: 471–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Olsson E, Ahlsén G, Eriksson M. Skin‐to‐skin contact reduces near‐infrared spectroscopy pain responses in premature infants during blood sampling. Acta Paediatr 2016; 105: 376–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Stone K, Wheeler A. A review of anatomy, physiology, and benign pathology of the nipple. Ann Surg Oncol 2015; 22: 3236–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Doucet S, Soussignan R, Sagot P, Schaal B. The secretion of areolar (Montgomery's) glands from lactating women elicits selective, unconditional responses in neonates. PLoS ONE 2009; 4: e7579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Varendi H, Porter RH. Breast odour as the only maternal stimulus elicits crawling towards the odour source. Acta Paediatr Oslo Nor 1992; 2001: 372–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Varendi H, Christensson K, Porter RH, Winberg J. Soothing effect of amniotic fluid smell in newborn infants. Early Hum Dev 1998; 51: 47–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Schaal B, Marlier L, Soussignan R. Human foetuses learn odours from their pregnant mother's diet. Chem Senses 2000; 25: 729–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Mennella JA, Jagnow CP, Beauchamp GK. Prenatal and postnatal flavor learning by human infants. Pediatrics 2001; 107: E88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Delaunay‐El Allam M, Soussignan R, Patris B, Marlier L, Schaal B. Long‐lasting memory for an odor acquired at the mother's breast: Memory for odor acquired at the mother's breast. Dev Sci 2010; 13: 849–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Mennella JA. Flavour Programming during Breast‐Feeding In: Goldberg G, Prentice A, Prentice A, Filteau S, Simondon K, editors. Breast‐feeding: early influences on later health. Dordrecht, the Netherlands: Springer , 2009: 113–20. Available at: http://link.springer.com/10.1007/978-1-4020-8749-3_9 [Google Scholar]

- 76. Todrank J, Heth G, Restrepo D. Effects of in utero odorant exposure on neuroanatomical development of the olfactory bulb and odour preferences. Proc R Soc B Biol Sci 2011; 278: 1949–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Einspieler C, Marschik PB, Prechtl HF. Prenatal origin and early postnatal development. J Psychol 2008; 216: 148–54. [Google Scholar]

- 78. Prechtl . Prenatal and early postnatal development of human motor behavior In: Kalverboer AF, Gramsbergen AA, editors. Handbook of brain and behavior in human development. Dordrecht, the Netherlands: Kluwer, 2001: 415–28. [Google Scholar]

- 79. Marlier L, Schaal B, Soussignan R. Bottle‐fed neonates prefer an odor experienced in utero to an odor experienced postnatally in the feeding context. Dev Psychobiol 1998; 33: 133–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Tellström R. Sommar & Vinter i P1. Sweden: Sveriges Radio, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 81. DeCasper AJ, Fifer WP. Of human bonding: newborns prefer their mothers’ voices. Science 1980; 208: 1174–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Moon C, Lagercrantz H, Kuhl PK. Language experienced in utero affects vowel perception after birth: a two‐country study. Acta Paediatr 2013; 102: 156–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Fawcett C, Arslan M, Falck‐Ytter T, Roeyers H, Gredebäck G. Human eyes with dilated pupils induce pupillary contagion in infants. Sci Rep 2017; 7 Available from: http://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-017-08223-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Dani C, Cecchi A, Commare A, Rapisardi G, Breschi R, Pratesi S. Behavior of the Newborn during Skin‐to‐Skin. J Hum Lact 2015; 31: 452–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Tambini A, Ketz N, Davachi L. Enhanced brain correlations during rest are related to memory for recent experiences. Neuron 2010; 65: 280–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Cantrill RM, Creedy DK, Cooke M, Dykes F. Effective suckling in relation to naked maternal‐infant body contact in the first hour of life: an observation study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2014; 14: 20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Svensson KE, Velandia MI, Matthiesen A‐ST, Welles‐Nyström BL, Widström A‐ME. Effects of mother‐infant skin‐to‐skin contact on severe latch‐on problems in older infants: a randomized trial. Int Breastfeed J 2013; 8: 1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Cato K, Sylvén SM, Skalkidou A, Rubertsson C. Experience of the first breastfeeding session in association with the use of the hands‐on approach by healthcare professionals: a population‐based Swedish study. Breastfeed Med Off J Acad Breastfeed Med 2014; 9: 294–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Fletcher D, Harris H. The implementation of the HOT program at the Royal Women's Hospital. Breastfeed Rev Prof Publ Nurs Mothers Assoc Aust 2000; 8: 19–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Kremer KP, Kremer TR. Breastfeeding is associated with decreased childhood maltreatment. Breastfeed Med 2018; 13: 18–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Christensson K, Siles C, Moreno L, Belaustequi A, De La Fuente P, Lagercrantz H, et al. Temperature, metabolic adaptation and crying in healthy full‐term newborns cared for skin‐to‐skin or in a cot. Acta Paediatr Oslo Nor 1992; 1992: 488–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Parker LA, Sullivan S, Krueger C, Mueller M. Association of timing of initiation of breastmilk expression on milk volume and timing of lactogenesis stage II among mothers of very low‐birth‐weight infants. Breastfeed Med Off J Acad Breastfeed Med 2015; 10: 84–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Pejovic NJ, Herlenius E. Unexpected collapse of healthy newborn infants: risk factors, supervision and hypothermia treatment. Acta Paediatr 2013; 102: 680–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Poets A, Urschitz MS, Steinfeldt R, Poets CF. Risk factors for early sudden deaths and severe apparent life‐threatening events: Table 1. Arch Dis Child ‐ Fetal Neonatal Ed 2012; 97: F395–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Ludington‐Hoe SM, Morgan K. Infant assessment and reduction of sudden unexpected postnatal collapse risk during skin‐to‐skin contact. Newborn Infant Nurs Rev 2014; 14: 28–33. [Google Scholar]

- 96. Becher J‐C, Bhushan SS, Lyon AJ. Unexpected collapse in apparently healthy newborns – a prospective national study of a missing cohort of neonatal deaths and near‐death events. Arch Dis Child ‐ Fetal Neonatal Ed 2012; 97: F30–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Matthijsse PR, Semmekrot BA, Liem KD. Skin to skin contact and breast‐feeding after birth: not always without risk!. Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd 2016; 160: D171. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Meek JY, Noble L. Implementation of the ten steps to successful breastfeeding saves lives. JAMA Pediatr 2016; 170: 925–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Bass JL, Gartley T, Kleinman R. Unintended consequences of current breastfeeding initiatives. JAMA Pediatr 2016; 170: 923–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100. Lehtonen L, Gimeno A, Parra‐Llorca A, Vento M. Early neonatal death: A challenge worldwide. Semin Fetal Neonatal Med 2017; 22: 153–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101. Bartick M, Feldman‐Winter L. Skin‐to‐skin care cannot be blamed for increase in suffocation deaths. J Pediatr 2018. Available at: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0022347618307790 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102. Chu DM, Ma J, Prince AL, Antony KM, Seferovic MD, Aagaard KM. Maturation of the infant microbiome community structure and function across multiple body sites and in relation to mode of delivery. Nat Med 2017; 23: 314–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103. Indrio F, Martini S, Francavilla R, Corvaglia L, Cristofori F, Mastrolia SA, et al. Epigenetic matters: the link between early nutrition, microbiome, and long‐term health development. Front Pediatr 2017; 5 Available at: http://journal.frontiersin.org/article/10.3389/fped.2017.00178/full [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104. Schlinzig T, Johansson S, Gunnar A, Ekström T, Norman M. Epigenetic modulation at birth ‐ altered DNA‐methylation in white blood cells after Caesarean section. Acta Paediatr 2009; 98: 1096–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105. Dumas L, Lepage M, Bystrova K, Matthiesen A‐S, Welles‐Nyström B, Widström A‐M. Influence of skin‐to‐skin contact and rooming‐in on early mother‐infant interaction: a randomized controlled trial. Clin Nurs Res 2013; 22: 310–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106. Bystrova K, Ivanova V, Edhborg M, Matthiesen A‐S, Ransjö‐Arvidson A‐B, Mukhamedrakhimov R, et al. Early contact versus separation: effects on mother‐infant interaction one year later. Birth Berkeley Calif 2009; 36: 97–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107. Moffitt TE, Arseneault L, Belsky D, Dickson N, Hancox RJ, Harrington H, et al. A gradient of childhood self‐control predicts health, wealth, and public safety. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2011; 108: 2693–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]