Abstract

Case series summary

Two cats were presented for investigation of bradyarrhythmia detected by their referring veterinarians during routine examination. Both cats had extensive investigations, including haematology, serum biochemistry with electrolytes and thyroxine concentrations, systolic blood pressure measurement, echocardiography, electrocardiography and infectious disease testing. Infectious disease testing included serology for Toxoplasma gondii, Ehrlichia canis, Anaplasma phagocytophilum and Borrelia burgdorferi, and PCR for B burgdorferi antigen in both cats. Case 1 was also assessed by PCR for Bartonella henselae antigen and case 2 was assessed for Dirofilaria immitis by serology. All infectious disease tests, other than for B burgdorferi, were negative. Case 1 was diagnosed with Lyme carditis based on marked bradydysrhythmia, positive B burgdorferi serology, a structurally normal heart and clinical resolution with appropriate treatment with a 4-year follow-up. Case 2 was diagnosed with Lyme carditis based on marked bradydysrhythmia and positive B burgdorferi PCR; however, this cat had structural heart disease that did not resolve with treatment.

Relevance and novel information

This small case series describes two B burgdorferi positive cats presenting with newly diagnosed cardiac abnormalities consistent with those found in humans and dogs with Lyme carditis. Both cats were asymptomatic as perceived by their owners; the arrhythmia was detected by their veterinarians.

Keywords: Borrelia burgdorferi, Lyme disease, Lyme carditis, bradyarrhythmia

Introduction

Lyme borreliosis is caused by a group of Gram negative spirochete bacteria in the Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato complex. Pathogens in this group are an important cause of morbidity and mortality in humans, with a wide geographical distribution.1–4 Dogs and cats are frequently seropositive, but clinical disease is rare and most commonly reported in dogs.5

Transmission of B burgdorferi requires Ixodes species ticks.6,7 Ixodes ticks live for 2 years, with a three-stage life cycle, where they feed on a variety of different-sized animals, giving them ample opportunity to be infected with and transmit Borrelia organisms.8

In the UK, ticks on cats are usually Ixodes species, predominantly I ricinus (57%) and I hexagonus (41%), with 1.8% of all ticks found to harbour B burgdorferi, although in certain areas the prevalence of infection in ticks is as high as 67%.7,9 These findings are echoed worldwide, with geographical variation in seroprevalence.10–12

Clinical disease in cats with Lyme borreliosis is poorly characterised. Experimentally infected cats have most commonly been asymptomatic.13–15 To our knowledge, there has previously only been one case series of clinical Lyme borreliosis in cats in the USA, and one report of suspected clinical Lyme borreliosis in two cats in the UK.16,17 The former publication reported positive serology for B burgdorferi in cats with clinical signs, including lethargy, lameness, anorexia and hindlimb ataxia, with response to treatment with doxycycline.16 The report from the UK describes recurrent pyrexia in two cats that were identified as PCR-positive for the organism, although treatment and outcome are not reported.17

Lyme carditis is an uncommon clinical manifestation of Lyme borreliosis in people, occurring in approximately 1–10% of cases, depending on geographical location.18,19 The hallmark of Lyme carditis in people is bradydysrhythmia (most commonly second- or third-degree atrioventricular block) and, less commonly, perimyocarditis.18 In dogs, reports of suspected Lyme carditis are rare and the most common presentations are sudden death due to myocarditis, and by dilated cardiomyopathy, although a positive response to treatment has yet to be demonstrated in dogs with Lyme carditis.20–22

Here we present two cases of suspected Lyme carditis, one of which is the first case of a cat with Lyme carditis with resolution of clinical signs demonstrated after treatment.

Case series description

Case 1

A 7-year-old male neutered Maine Coon cat was presented to the Royal (Dick) School of Veterinary Studies (RDSVS), for assessment of a newly detected arrhythmia. The cat had outdoor access and was fully vaccinated (against feline calicivirus [FCV], feline herpes virus [FeHV], feline panleucopenia virus [FPV] and feline leukaemia virus [FeLV]). The cat was fed a commercial dry food. It had been more than 1 year since any parasite treatment. The arrhythmia was identified during a routine physical examination. There was no significant previous medical history, other than chronic osteoarthritis (OA) of the hips. The owners reported a circular erythematous lesion resembling a tick bite target lesion of about 1 cm diameter on the cat’s ventral abdomen 10 months previously, following a camping trip with the owners in the Scottish Highlands.

Physical examination revealed the cat to be bright, alert and responsive (body weight 6.97 kg; body condition score [BCS] 6/9). Respiratory rate and character were normal (32 breaths per min), oral mucus membranes were pink and moist, and capillary refill time (CRT) was <2 s. Heart rate was variable, ranging between bradycardia at 60 beats per min (bpm) and 140 bpm; no murmurs were evident. Heart rhythm was irregular, with multiple suspected ectopic beats audible; pulse strength was strong, but pulse deficits were present. Rectal temperature was normal. Both hips had reduced mobility, with some discomfort (consistent with chronic OA of the hip), but no other joints were painful or swollen, and the remainder of the physical examination was unremarkable.

Electrocardiography (ECG) was performed using a standard six-lead technique, revealing periods of sinus rhythm at 160 bpm, interspersed with periods of bradydysrhythmia with ventricular bigeminy and ventricular ectopic beats. There were multiple rhythm abnormalities – including triplets (relatively malignant as R on T in the central beat), singular ectopy, ventricular ectopy from different foci, periods of sinus, and periods of bigeminy and trigeminy.

Blood pressure was normal (130 mmHg, Doppler method). Atropine (0.04 mg/kg IV) resulted in a sustained sinus rhythm for 30 mins, followed by a sustained idioventricular rhythm.

Echocardiography (ECHO) revealed no myocardial changes and no gross structural disease. There was a mild decrease in systolic function based on a decreased fractional shortening (27%, reference >30%) and borderline left ventricular internal diameter in systole (14.1 mm, reference interval [RI] 6.1–14.1 mm).

A 24 h ECG (Holter monitor) was fitted and revealed marked dysrhythmia, including a third-degree atrioventricular (AV) block, plus multifocal ventricular ectopy occurring both singly and in triplets, with periods of bigeminy and trigeminy (Figures 1 and 2). Sustained sinus rhythm occurred only occasionally with a heart rate of 140–160 bpm.

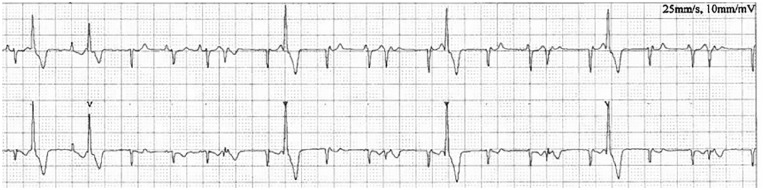

Figure 1.

Holter trace from case 1 illustrating an underlying sinus rhythm with a heart rate of 130 beats per min. There are frequent isolated monomorphic ventricular premature complexes and intermittent supraventricular complexes, some of which are prematures. Paper speed 25 mm/s, 10 mm/mV

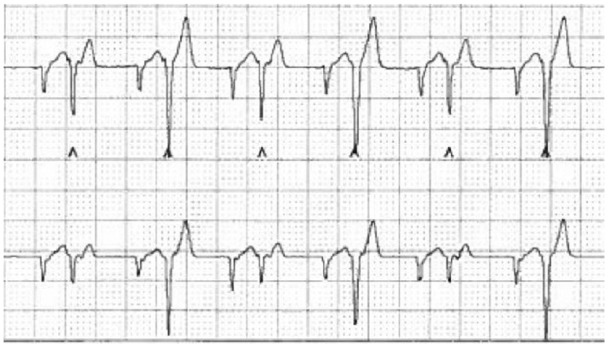

Figure 2.

Holter trace showing an underlying irregular rhythm with a rate of 200 beats per min. No sinus beats are observed. There are frequent isolated monomorphic ventricular premature complexes and supraventricular complexes, some of which are prematures, with some bigeminy noted. Paper speed 25 mm/s, 10 mm/mV

Routine haematology and serum biochemistry, including total thyroxine concentration and electrolytes, revealed no abnormalities. Serum cardiac troponin I (Beaufort) was within the reference interval (RI) (0.02; RI <0.03), as was taurine concentration (IDEXX). Urine analysis, including culture and urine protein:creatinine ratio, was unremarkable.

Our differentials for the cardiac arrhythmias were primary cardiomyopathy or cardiomyopathy secondary to systemic disease. Owing to sporadic reports of cardiomyopathy owing to infectious disease in humans (Lyme carditis in particular) and cats, we pursued further infectious disease testing.23–28 In-house blood testing for feline immunodeficiency virus and FeLV (SNAP FIV/FeLV Combo Test; IDEXX) was negative. Serology for Toxoplasma gondii (IgG and IgM antibodies; Biobest Laboratories) was negative. Serology for B burgdorferi was positive at 5.5 (RI <4.5 [IgG ELISA; LVPD, University of Liverpool]), with a test that has been validated for use in cats.29 Whole-blood PCR tests for Borrelia, Bartonella and Ehrlichia/Anaplasma species (Acarus) were negative for all three groups of pathogens.

Seropositivity in isolation is not diagnostic for clinical Lyme disease,12 and, as such, the presumptive diagnosis of Lyme carditis was made based on positive serology of B burgdorferi in conjunction with compatible clinical signs. The cat was treated with doxycycline (Ronaxan [Boehringer Ingelheim Animal Health UK], 10 mg/kg q24h PO) for 30 days. A home visit a month later by one of the authors (DGM) revealed a heart rate of 120 bpm, no obvious dysrhythmia and regular matched pulses.

The cat remained clinically asymptomatic, and was re-examined 1 year later; ECHO and ECG revealed a structurally normal heart with a heart rate of 140–160 bpm, and no dysrhythmia. At 17 months after initial presentation, B burgdorferi serology was repeated and found to be unchanged from previously (5; RI <4.5). Regular re-examination until euthanasia owing to a thymoma 2.5 years later consistently found a heart rate of 160–200 bpm, with a regular rhythm and good strength matching pulses. Post-mortem examination revealed a grossly and histologically normal heart, with no signs of remaining Lyme disease-associated interstitial myocarditis. This case demonstrates clinical resolution of bradydysrhythmia believed to have been caused by B burgdorferi infection, following treatment of doxycycline; the bradydysrhythmia did not return in the 4 years after treatment.

Case 2

A 15-year-old male neutered Siamese/Burmese cross cat was presented to the RDSVS, for assessment of bradycardia and erratic heart rhythm auscultated during a routine evaluation. The cat lived indoors, but had outdoor access when the owners visited their holiday home on the west coast of Scotland, last visiting 4 months previously. The cat was up to date with vaccinations (FCV, FeHV, FPV, FeLV) and treated for endoparasites. No treatments for ectoparasites were given. The cat lived with its biological sibling, a male on whom a tick had been found during their last visit to the same location; the area is endemic for ticks and deer were regularly seen in the garden.

On presentation, the cat was reported to be well, apart from mild weight loss. Physical examination revealed a quiet, alert and responsive cat (weight 3.67 kg, BCS 3/9). Oral mucous membranes were pink, with a normal CRT. Heart rate was 88 bpm, with a regular rhythm, no murmur and matching femoral pulses of good strength. Respiratory rate was 36 breaths per min; effort, pattern and auscultation were normal. The rest of the clinical examination was normal; there were no signs of joint swelling or discomfort, and rectal temperature was normal. Systolic blood pressure was normal (140 mmHg; Doppler method).

ECG revealed third-degree AV block with a ventricular escape rate of 88–90 bpm and an atrial rate of 120 bpm. Ventricular premature complexes of three different morphologies were interspersed within the ventricular escape rhythm, with a maximum of rate of 180 bpm. No sinus rhythm was evident.

ECHO revealed moderate/severe right ventricular dilation, left ventricular dilation with normal contractility, normal wall thickness, and prominent left and right atria consistent with an unclassified cardiomyopathy. Mild aortic, pulmonic, tricuspid and mitral insufficiencies were evident and were considered likely to be secondary to chamber dilation.

Further investigations were undertaken to determine a potential cause of the cardiac dysfunction. Haematology revealed mild lymphopenia, while serum biochemistry revealed mild increases in alanine aminotransferase (152 U/l; RI 6–83 U/l), urea (15 mmol/l; RI 2.8–9.8 mmol/l) and creatinine (187 µmol/l; RI 40–177µmol/l) concentrations; total thyroxine concentration was unremarkable. Urine protein was not evaluated. Serum cardiac troponin I concentration was slightly increased (0.08 ng/ml; RI <0.03 ng/ml). The reasons for pursuing infectious disease testing in case 2 were the same as in case 1. Serology for Anaplasma phagocytophilum, B burgdorferi, Ehrlichia canis and Dirofilaria immitis (IDEXX SNAP 4Dx) and Toxoplasma gondii (IgG and IgM antibodies; Biobest Laboratories) was negative, as was Ehrlichia/Anaplasma species DNA by PCR on whole blood (Acarus). Borrelia species PCR on blood was positive (Acarus).

A diagnosis was made of B burgdorferi infection suspected of causing Lyme carditis, and the cat was treated with doxycycline (Ronaxan [Boehringer Ingelheim Animal Health UK], 10 mg/kg q24h PO) for 3 weeks.

The cat was re-assessed after completing the antibiotic course. The cat was clinically well with a home respiratory rate of 20 breaths per min. In the clinic, the heart rate was 88 bpm, regular, with matched strong pulses. The rest of the physical examination was unremarkable. Systolic blood pressure was normal (130 mmHg). There were no significant changes from previously on ECG and ECHO.

Other possible causes of the arrhythmia were assessed by abdominal ultrasound and thoracic radiography, neither of which revealed any abnormalities. Serology for B burgdorferi (4; RI < 4.5; LVPD, University of Liverpool), and Borrelia species PCR on blood (Acarus) were both now negative.

The cat was assessed after 3 months and 10 months, and was still asymptomatic. The heart rate, ECG and ECHO findings were largely unchanged from the previous examination. Haematology and serum biochemistry, revealed chronic kidney disease (CKD) IRIS stage 3 (creatinine 255 µmol/l [RI 40–177 µmol/l]; urea 17.1 mmol/l [RI 2.8–9.8 mmol/l]); total thyroxine concentration was unremarkable. Urine protein quantification was not evaluated.

Fourteen months later, aged 17 years, the cat presented with tachypnoea and was diagnosed with congestive heart failure. ECHO revealed severe dilatation of the right-sided chambers, especially the right atrium. ECG revealed a third-degree AV block. The ECG and ECHO findings suggested advanced cardiomyopathy, with a phenotype suggestive of arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy.

Despite treatment, congestive heart failure progressed and the cat was euthanased.

Discussion

We present the first two feline cases of Lyme carditis, which include full case details, treatment and outcomes; case 1 is also the first case of feline Lyme carditis with clinical resolution on treatment.

Prior to diagnosis, the cats had been in the Scottish Highlands, a high-risk area for B burgdorferi in people.30 Neither of the cats had other clinical abnormalities that could be attributed to B burgdorferi, although case 2 was not evaluated for proteinuria, which would have been pertinent in relation to a potential concurrent Lyme nephritis (and as a part of a standard investigation of CKD). Both cats had third-degree AV block, which is the most common finding in humans with Lyme carditis.

Case 1 had a history of erythema migrans, positive B burgdorferi serology and a bradydysrhythmia that resolved upon treatment. While it could be argued that there may have been another pathogen present that responded to treatment with doxycycline, this seems unlikely considering the cat was clinically well and tested negative for Bartonella, Anaplasma, Ehrlichia and Toxoplasma species. Lyme carditis has been reported in dogs; however, there is no report of complete clinical resolution after treatment in dogs.20–22,31

In case 2, it is possible that while the cat was PCR positive for B burgdorferi, the cardiomyopathy and arrhythmia may not have been caused by this infection. However, the cat did have a third-degree AV block, which is the most common abnormality in human Lyme carditis, with dilation of all cardiac chambers, which is the second most common abnormality in canine Lyme carditis.19,20,22,31 In addition, as with all reported cases of canine Lyme carditis, this cat’s cardiac pathology did not resolve with appropriate treatment. This cat had not seroconverted a month after diagnoses; however, it can take more than 7 weeks for cats to develop seropositivity, and in some cats antibodies are only detectable for 1 week.14 This is in contrast to dogs, where seroconversion typically occurs 4–6 weeks postinfection and lasts for years.32 PCR positivity is rare with B burgdorferi as bacterial burden is low and the pathogen sequesters to tissue, which is also the reason why sensitivity is higher in body tissues than in body fluids.32

Of note, both cases had a normal and a slightly elevated troponin I. It may be expected that this would be more increased in myocarditis; however, human cases of Lyme carditis have also been reported where the troponin was within normal limits or only mildly elevated.33–35

There were a number of limitations to our study, particularly pertaining to case 2, including the lack of urine protein quantification, lack of a post-mortem examination and lack of response to treatment, although the latter is common in dogs with Lyme carditis.

It is likely that further cases of Lyme carditis may emerge in cats, as most practitioners currently do not test for B burgdorferi in cats with cardiac abnormalities, especially as the cats may be otherwise asymptomatic and many cats do not see a veterinarian regularly. In humans and dogs, Lyme carditis is reported to cause sudden death, which may also be the case in cats and could explain under recognition.19,22

Conclusions

Lyme carditis can affect cats and based on this small case series, a positive response to treatment with clinical resolution is achievable. Further investigations are needed to fully elucidate the nature of Lyme borreliosis in cats, but given the effect of climate change with globally increasing prevalence of ticks and tick-borne infections, we suspect further cases will emerge.36,37

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the owners of the cats, the referring veterinarians, and all staff and students who helped in the investigation, treatment and care of these two cats.

Footnotes

Accepted: 9 December 2019

Conflict of interest: The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Ethical approval: This work involved the use of non-experimental animal(s) only (owned or unowned), and followed established internationally recognised high standards (‘best practice’) of individual veterinary clinical patient care. Ethical approval from a committee was not necessarily required.

Informed consent: Informed consent (either verbal or written) was obtained from the owner or legal custodian of all animal(s) described in this work for the procedure(s) undertaken. For any animals or humans individually identifiable within this publication, informed consent for their use in the publication (verbal or written) was obtained from the people involved.

ORCID iD: Camilla Tørnqvist-Johnsen  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5544-4819

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5544-4819

References

- 1. Mead PS. Epidemiology of Lyme disease. Infect Dis Clin North Am 2015; 29: 187–210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Rizzoli A, Hauffe H, Carpi G, et al. Lyme borreliosis in Europe. Euro Surveill 2011; 16 DOI: 10.2807/ese.16.27.19906-en. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Masuzawa T. Terrestrial distribution of the Lyme borreliosis agent Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato in East Asia. Jpn J Infect Dis 2004; 57: 229–235. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Sprong H, Azagi T, Hoornstra D, et al. Control of Lyme borreliosis and other Ixodes ricinus-borne diseases. Parasit Vectors 2018; 11: 145 DOI: 10.1186/s13071-018-2744-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Littman MP, Goldstein RE, Labato MA, et al. ACVIM small animal consensus statement on Lyme disease in dogs: diagnosis, treatment, and prevention. J Vet Intern Med 2006; 20: 422–434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Rudenko N, Golovchenko M, Grubhoffer L, et al. Updates on Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato complex with respect to public health. Ticks Tick Borne Dis 2011; 2: 123–128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Davies S, Abdullah S, Helps C, et al. Prevalence of ticks and tick-borne pathogens: Babesia and Borrelia species in ticks infesting cats of Great Britain. Vet Parasitol 2017; 244: 129–135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Anderson JF. Epizootiology of Borrelia in Ixodes tick vectors and reservoir hosts. Rev Infect Dis 1989; 11 Suppl 6: S1451–S1459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Sorouri R, Ramazani A, Karami A, et al. Isolation and characterization of Borrelia burgdorferi strains from Ixodes ricinus ticks in the southern England. Bioimpacts 2015; 5: 71–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Magnarelli LA, Bushmich SL, JW IJ, et al. Seroprevalence of antibodies against Borrelia burgdorferi and Anaplasma phagocytophilum in cats. Am J Vet Res 2005; 66: 1895–1899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Pantchev N, Vrhovec MG, Pluta S, et al. Seropositivity of Borrelia burgdorferi in a cohort of symptomatic cats from Europe based on a C6-peptide assay with discussion of implications in disease aetiology. Berl Munch Tierarztl Wochenschr 2016; 129: 333–339. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. May C, Carter S, Barnes A, et al. Borrelia burgdorferi infection in cats in the UK. J Small Anim Pract 1994; 35: 517–520. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Burgess EC. Experimentally induced infection of cats with Borrelia burgdorferi. Am J Vet Res 1992; 53: 1507–1511. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Lappin MR, Chandrashekar R, Stillman B, et al. Evidence of Anaplasma phagocytophilum and Borrelia burgdorferi infection in cats after exposure to wild-caught adult Ixodes scapularis. J Vet Diagn Invest 2015; 27: 522–525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Gibson MD, Omran MT, Young CR. Experimental feline Lyme borreliosis as a model for testing Borrelia burgdorferi vaccines. Adv Exp Med Biol 1995; 383: 73–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hoyt K, Chandrashekar R, Beall M, et al. Evidence for clinical anaplasmosis and borreliosis in cats in Maine. 2018; 33: 40–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Shaw S, Binns S, Birtles R, et al. Molecular evidence of tick-transmitted infections in dogs and cats in the United Kingdom. Vet Rec 2005; 157: 645–648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Forrester JD, Meiman J, Mullins J, et al. Notes from the field: update on Lyme carditis, groups at high risk, and frequency of associated sudden cardiac death – United States. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2014; 63: 982–983. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Scheffold N, Herkommer B, Kandolf R, et al. Lyme carditis – diagnosis, treatment and prognosis. Dtsch Arztebl Int 2015; 112: 202–208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Levy SA, Duray PH. Complete heart block in a dog seropositive for Borrelia burgdorferi. Similarity to human Lyme carditis. J Vet Intern Med 1988; 2: 138–144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Janus I, Noszczyk-Nowak A, Nowak M, et al. Myocarditis in dogs: etiology, clinical and histopathological features (11 cases: 2007–2013). Ir Vet J 2014; 67: 28 DOI: 10.1186/s13620-014-0028-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Detmer SE, Bouljihad M, Hayden DW, et al. Fatal pyogranulomatous myocarditis in 10 Boxer puppies. J Vet Diagn Invest 2016; 28: 144–149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Shah SS, McGowan JPJFB. Rickettsial, ehrlichial and Bartonella infections of the myocardium and pericardium. Front Biosci 2003; 8: e197–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Havens NS, Kinnear BR, Mató SJCID. Fatal ehrlichial myocarditis in a healthy adolescent: a case report and review of the literature. Clin Infect Dis 2012; 54: e113–e114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Leak D, Meghji M. Toxoplasmic infection in cardiac disease. Am J Cardiol 1979; 43: 841–849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Rolim VM, Casagrande RA, Wouters ATB, et al. Myocarditis caused by feline immunodeficiency virus in five cats with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J Comp Pathol 2016; 154: 3–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Chomel BB, Kasten R, Williams C, et al. Bartonella endocarditis: a pathology shared by animal reservoirs and patients. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2009; 1166: 120–126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Simpson KE, Devine BC, Gunn-Moore D. Suspected toxoplasma-associated myocarditis in a cat. J Feline Med Surg 2005; 7: 203–208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. May C, Carter S, Barnes A, et al. Borrelia burgdorferi infection in cats in the UK. J Small Anim Pract 1994; 35: 517–520. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Mavin S, Watson EJ, Evans R. Distribution and presentation of Lyme borreliosis in Scotland – analysis of data from a national testing laboratory. J R Coll Physicians Edinb 2015; 45: 196–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Agudelo C, Schanilec P, Kybicova K, et al. Cardiac manifestations of borreliosis in a dog: a case report. Vet Med Czech 2011; 56: 85–92. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Krupka I, Straubinger RK. Lyme borreliosis in dogs and cats: background, diagnosis, treatment and prevention of infections with Borrelia burgdorferi sensu stricto. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract 2010; 40: 1103–1119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Rojas-Marte G, Chadha S, Topi B, et al. Heart block and Lyme carditis. QJM 2014; 107: 771–772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Michalski B, Umpierrez De, Reguero A. Lyme carditis buried beneath ST-segment elevations. Case Rep Cardiol 2017; 2017: 9157625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Afari ME, Marmoush F, Rehman MU, et al. Lyme carditis: an interesting trip to third-degree heart block and back. Case Rep Cardiol 2016; 2016: 5454160. DOI: 10.1155/2016/5454160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Ogden NH, Radojevic M, Wu X, et al. Estimated effects of projected climate change on the basic reproductive number of the Lyme disease vector Ixodes scapularis. Environ Health Perspect 2014; 122: 631–638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Medlock JM, Hansford KM, Bormane A, et al. Driving forces for changes in geographical distribution of Ixodes ricinus ticks in Europe. Parasit Vectors 2013; 6: 1 DOI: 10.1186/1756-3305-6-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]