Abstract

Oral Submucous fibrosis (OSMF) has traditionally been described as “a chronic, insidious, scarring disease of the oral cavity, often with involvement of the pharynx and the upper esophagus”. Millions of individuals are affected, especially in South and South East Asian countries. The main risk factor is areca nut chewing. Due to its high morbidity and high malignant transformation rate, constant efforts have been made to develop effective management. Despite this, there have been no significant improvements in prognosis for decades. This expert opinion paper updates the literature and provides a critique of diagnostic and therapeutic pitfalls common in developing countries and of deficiencies in management. An inter-professional model is proposed to avoid these pitfalls and to reduce these deficiencies.

Keywords: Oral submucous fibrosis, Global epidemiology, Areca nut, Management

Introduction

Oral Submucous Fibrosis (OSMF) is a potentially malignant disorder which was described by Schwartz in 1952 as “Atropica idiopathica mucosae oris” and later by Jens J. Pindborg in 1966 as “an insidious, chronic disease that affects any part of the oral cavity and sometimes the pharynx [1]. Although occasionally preceded by, or associated with, the formation of vesicles, it is always associated with a juxtaepithelial inflammatory reaction followed by fibroelastic change of the lamina propria and epithelial atrophy that leads to stiffness of the oral mucosa and causes trismus and an inability to eat” [1]. OSMF is also characterized by reduced movement and depapillation of the tongue, blanching and leathery texture of the oral mucosa, progressive reduction of mouth opening, and shrunken uvula [2–4]. Other terms used to describe OSMF include idiopathic scleroderma of the mouth, juxtaepithelial fibrosis, idiopathic palatal fibrosis, diffuse oral submucous fibrosis, and sclerosing stomatitis [5–8].

Epidemiology (Table 1) (Fig. 1)

Table 1.

Worldwide prevalence studies on Oral Submucous Fibrosis

| Year | Authors | Study type | Sample size | Country | City/district | State/Province | Prevalence (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1965 | Pindborg J. J. et al. [9] | Observational | 10,000 | India | Mumbai | Maharashtra | 0.50 |

| 1965 | Pindborg J. J. et al. [10] | Cross sectional | 10,000 | India | Lucknow | Uttar Pradesh | 4.1 |

| 1966 | Pindborg J. J. et al. [11] | Observational | 10,000 | India | Bengaluru | Karnataka | 0.18 |

| 1966 | Zachariah et al. [12] | Observational | 5000 | India | Thiruvananthapuram | Kerala | 1.22 |

| 1968 | Pindborg J. J. et al. [13] | Observational | 50,915 | India | Srikakulam | Andra Pradesh | 0.04 |

| Darbhanga | Bihar | 0.07 | |||||

| Bhavnagar | Gujarat | 0.16 | |||||

| Ernakulum | Kerala | 0.36 | |||||

| 1970 | Wahi et al. [14] | Observational | India | Mainpuri | Uttar Pradesh | 0.59 | |

| 1972 | Mehta F. S. et al. [15] | Survey | 101,761 | India | Pune | Maharashtra | 0.03 |

| 1982 | Lay K. M. et al. [16] | Cross sectional | 6000 | Myanmar | Bilugyun | Mon | 0.1 |

| 1988 | Seedat H. A. et al. [17] | Cross sectional | 2400 | South Africa | Durban | KwaZulu-Natal | 3.4 |

| 1997 | Tang J.G. et al. [18] | Cross sectional | 11,046 | China | Xiangtan | Hunan | 3.30 |

| 2006 | Patil P. B. et al. [19] | Cross sectional | 2400 | India | Dharwad | Karnataka | 7.8 |

| 2007 | Hazarey V. K. et al. [20] | Cross sectional | 1000 | India | Nagpur | Maharashtra | 6.42 |

| 2008 | Mathew A. L. et al. [21] | Observational | 1190 | India | Manipal | Karnataka | 2.01 |

| 2008 | Mehrotra R. et al. [22] | Retrospective | 1151 | India | Allahabad | Uttar Pradesh | 17.02 |

| 2012 | Sharma R. et al. [23] | Cross sectional survey | 6800 | India | Jaipur | Rajasthan | 3.39 |

| 2012 | Agarwal A. et al. [24] | Observational | 750 | India | Dehradun | Uttarakhand | 5.4 |

| 2013 | Bhatnagar P. et al. [25] | Survey | 8866 | India | Modinagar | Uttar Pradesh | 1.97 |

| 2014 | Burungale S. U. et al. [26] | Cross sectional | 800 | India | Jaitala, Nagpur | Maharashtra | 2.62 |

| 2014 | Nigam N. K. et al. [27] | Observational | 1000 | India | Moradabad | Uttar Pradesh | 6.3 |

| 2015 | Patil S. et al. [28] | Observational | 5100 | India | Jodhpur | Rajasthan | 30 |

| 2016 | Singh P. et al. [29] | Cross sectional survey | 132 | India | Nagpur | Maharashtra | 2.86 |

| 2018 | Tyagi V. N. et al. [30] | Cross sectional | 1167 | India | Nashik | Maharashtra | 3.51 |

| 2018 | Yang S. F. et al. [31] | Cross sectional | 23,373,51 | Republic of China | – | Taiwan | 16.2 |

| 2019 | More C. B, et al. [32] | Cross sectional | 13,874 | India | Vadodara | Gujarat | 7.21 |

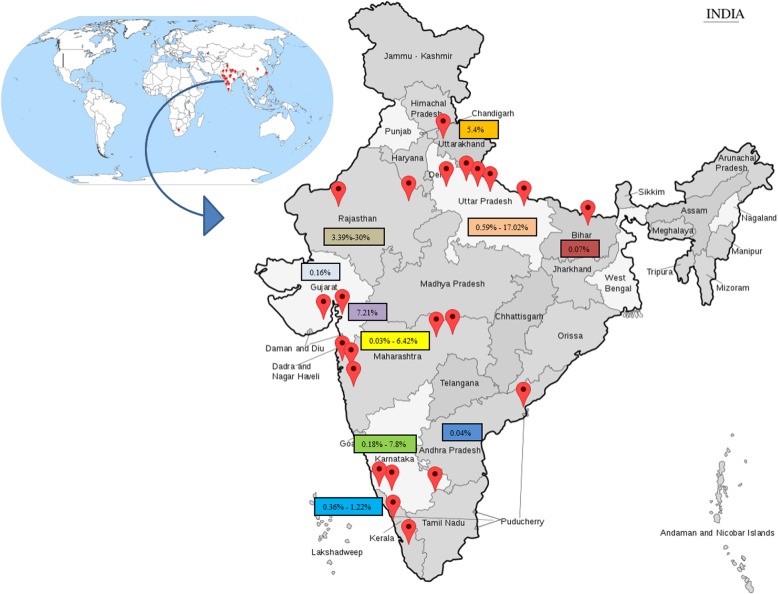

Fig. 1.

Global and Indian prevalence studies of Oral Submucous Fibrosis

Worldwide, the number of cases of OSMF was estimated to be 2.5 million in 1996 [33]. Although many case finding studies have been conducted, particularly in South and South East Asia, OSMF is not a notifiable disease and no population-based data are available [33]. The prevalence of OSMF in India has been estimated to range from 0.2–2.3% in males and 1.2–4.6% in females, with a broad age range from 11 to 60 years [34–36]. A marked increase in incidence has been observed after the widespread marketing of commercial tobacco and areca nut products, generally known as Gutkha, which is sold in single-use packets [33]. Currently, it is estimated that areca nut is consumed by 10–20% of the World’s population in a wide variety of formulations [37, 38]. The global South Asian diaspora also has a significant problem with cases reported from the United Kingdom, USA, South Africa, and many European countries.

Table 1 and Fig. 1 present published estimates of the prevalence of OSMF, which range from 0.1 to 30%, varying by geographical location, sample size, and sampling methodology. There is an urgent need for large well-designed epidemiological surveys to understand the true global and regional burden of OSMF.

Major etiology, contributing factors and etiopathogenesis (Tables 2 and 3) (Fig. 2)

Table 2.

Major aetiology of Oral Submucous Fibrosis

| Major aetiology | Description |

|---|---|

| Chewing of Areca nut (Baked or Raw) and/or derivatives such as Gutkha, Pan masala, Mawa, Betel quid, Sweet Supari and other formulations. | Arecoline and Arecaidine nitrosation causes DNA alkylation with proliferation of fibroblasts and elevated collagen synthesis [39]. |

Table 3.

Contributing risk factors for Oral Submucous Fibrosis

| Contributing factors | Description |

|---|---|

| Chewing smokeless tobacco | Dip, Snuff, Snus and chewing tobacco have been reported as major contributing factors [34, 35, 39, 40]. |

| Nutritional | Deficiencies of iron, folate & vitamin B12 result in mucosal atrophy, notably in the mouth. Increased levels of iron enhance hydroxylation of proline and lysine in the process of collagen synthesis [40]. |

| Chilies | Hypersensitivity reactions to capsaicin might contribute to fibrosis [41–43]. |

| Toxic levels of copper | Copper upregulates the enzyme lysyl oxidase, enhancing cross linking of collagen and elastin [35, 44, 45]. |

| Genetic predisposition | HLA-A10, HLA-B7, HLA-DR3, haplotypes A10/DR3, B3/DR3 and A10/B8 are found in increased frequency in OSMF patients [45]. |

| Immunological predisposition | Subjects with high endogenous expression of CD4 and HLA-DR on lymphocytes and Langerhans cells may have dysregulation of their immune-inflammatory response with bystander tissue injury [45]. |

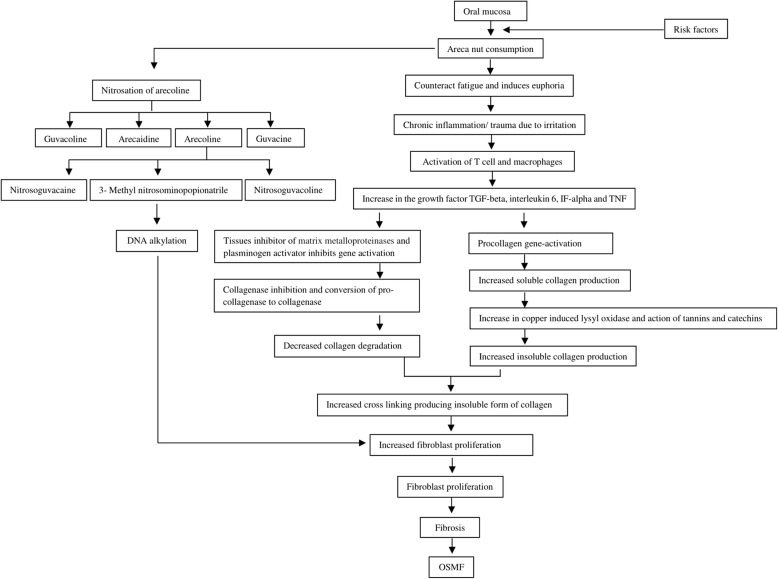

Fig. 2.

Etiopathogenesis [44]

Although the etiopathogenesis of this disease is multifactorial, areca nut-chewing in any formulation is considered the main causative agent. (Fig. 2) Contributory risk factors suggested includes chewing of smokeless tobacco, high intake of chilies, toxic levels of copper in foodstuffs and masticatories, vitamin deficiencies, and malnutrition resulting in low levels of serum proteins, anemia and genetic predisposition.

Diagnostic approach

Diagnosis of OSMF is based on clinical signs and symptoms that include burning sensation, pain, and ulceration (Table 4) [4, 46, 47]. Progressive restriction in mouth opening, blanching of the mucosa, depapillation of the tongue, and loss of pigmentation are other classic features (Fig. 3) [46]. Dysphonia and hearing impairment is also observed in advanced cases [48, 49]. Quality of life (QoL) is severely affected, worsening with increasing stage of the disease [50].

Table 4.

Intra- and extra- oral manifestations of OSMF at different stages

| Features | Early stage | Moderate stage | Advanced stage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intra oral | Stomatitis, excessive salivation, burning sensation, blanching of oral mucosa, blister formation, presence of thin palpable fibrous bands, sparse brown/black pigmentation. | Stomatitis, burning sensation, xerostomia, loss of taste sensation, gradual decrease in mouth opening, difficulty in whistling, vesicle formation, petechiae, rigid oral mucosa, difficulty in blowing the cheeks, defective gustatory sensation, blanching of oral mucosa – especially of soft palate, buccal mucosa, labial mucosa, tongue, floor of mouth, and faucial pillars. Presence of thick palpable fibrous bands, shrunken uvula with altered shape (inverted, hockey stick, bud like, deviated). | Stomatitis, burning sensation, xerostomia, reduction in mouth opening, restricted tongue movement, loss of taste sensation, Unable to blow the cheeks, defective gustatory sensation, inability to whistle, blanching of oral mucosa: esp. soft palate, buccal mucosa, labial mucosa, tongue, floor of mouth, and faucial pillars. Loss of suppleness of mucosa, mottled or opaque or white marble like appearance of oral mucosa, thick palpable fibrous bands on buccal and labial mucosa, de-papillation of tongue, shrunken uvula with altered shape (inverted, hockey stick, bud like, deviated), involvement of the pharyngeal and esophageal mucosa. |

| Extra oral | No Significant extra oral features are observed. | Prominent masseter muscle, nasal twang, sunken cheeks, thinning of lips, difficulty in deglutition, loss of naso-labial fold, prominent antegonial notch, hoarseness of voice, mild hearing impairment, weight loss. | Hypertrophic and stiff masseter muscle, nasal intonation of voice, sunken cheeks, multiple folds on cheeks when attempting wide opening of mouth, thinning of lips, difficulty in deglutition, loss of naso-labial fold, prominent antegonial notch, hoarseness of voice, severe hearing impairment, severe weight loss, hoarseness of voice, difficulty in deglutition, atrophy of facial musculature. In severe cases, radiographically, there is alteration in condylar form and fibrous ankylosis of the temporomandibular joints. |

Fig. 3.

Clinical expressions of Oral Submucous Fibrosis. Oral Submucous Fibrosis in a 27-year-old male with a history of gutkha chewing. Panel A shows sunken cheeks and prominent malar bone. Panel B shows significant blanching or marble-like appearance of the soft palate and faucial pillars. Note the altered, inverted shape of the uvula. Panels C & D show blanched bands of upper and lower labial mucosae and vestibule, which are stiff and palpable. Panels E, F & G: A 24-year-old female with a history of chewing baked areca nut. Panel E: significant blanching of soft palate and faucial pillars, and shrunken uvula. Panels F & G: thick fibrous bands and brown/black pigmentation on left & right buccal mucosae

OSMF progresses over time and management depends on the stage at clinical presentation. In 2012, More et al. proposed a disease progression-based classification (Table 5) which represents the clinical and functional staging of OSMF. This classification has been widely accepted/recommended as the closest fit for Indian population, especially to understand the disease progression/ clinical pattern [3, 35, 51]. In 2017, Passi D. et al. proposed a pathologically updated and treatment management-based classification. This classification chiefly focuses and recommends the treatment management based on the clinical stage of OSMF [52]. Later in 2018, Arakeri G. et al. proposed a three-component classification scheme (TFM) which can essentially be useful for effective communication amongst the care team, categorization of OSMF, recording data and disease prognosis, and treatment management. Additionally, this classification also describes OSMF malignant transformation in detail [53].

Table 5.

More et al. 2012 classification of OSMF

| Clinical staging | Interpretation |

|---|---|

| Stage 1 (S1) | Stomatitis and/or blanching of oral mucosa. |

| Stage 2 (S2) | Presence of palpable fibrous bands in buccal mucosa and/or oropharynx, with /without stomatitis. |

| Stage 3 (S3) | Presence of palpable fibrous bands in buccal mucosa and/or oropharynx, and in any other parts of oral cavity, with/ without stomatitis. |

| Stage 4 (S4) | Any one of the above stages along with other potentially malignant disorders (e.g. oral leukoplakia, oral erythroplakia) |

| Any one of the above stages along with oral squamous cell carcinoma. | |

| Functional staging | Interpretation |

| M1 Staging | Interincisal mouth opening up to or greater than 35 mm. |

| M2 Staging | Interincisal mouth opening between 25 and 35 mm. |

| M3 Staging | Interincisal mouth opening between 15 and 25 mm. |

| M4 Staging | Interincisal mouth opening less than 15 mm. |

Approaches to non-surgical management.

Although there is general agreement regarding clinical staging, approaches to management of patients vary widely [54]. Numerous interventions have been reported and are summarized in Table 6 [60, 68–70]. Supportive regimens, such as vitamin and iron supplements, a mineral-rich diet, red fruits, green leafy vegetables, and green tea consumption, are often recommended but there are no good quality studies confirming their efficacy.

Table 6.

Treatments for OSMF

| Treatment type | Agent | Authors | Study Type | Sample size (n) | Main findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Antioxidant treatments | Lycopene | Karemore T. V. and Motwani M [55]. | Single blinded prospective study | 92 | Ingestion of 8 g/QD of lycopene (n = 46) for three months was shown to be effective in the reduction of burning mouth and mouth opening (p < 0.05) in patients with OSMF when compared to the placebo group (n = 46). |

| Curcumin | Hazarey V. et al. [56] | Randomized control clinical trial | 30 | Sucking 2 g/QD of Curcumin lozenges (n = 15) with physiotherapy for three months showed a significant improvement in both mouth opening and in alleviating the burning sensation (p < 0.05) in comparison to the control group (clobetasol propionate 0.05%; (n = 15). | |

| Micronutrient therapy | Maher R. et al. [57] | Single arm preliminary prospective study | 117 | Swallowing micronutrient supplements: vitamins A, B complex, C, D, E; and minerals iron, calcium, copper, zinc, and magnesium was observed to be significantly effective (p < 0.05) in reduction of sign and symptoms of OSMF over 3 years. | |

| Spirulina and Aloe Vera | Patil S. et al. [58] | Double blinded prospective study | 42 | Ingestion of 500 mg/QD of Spirulina (n = 21) for 3 months was associated with a significant improvement in mouth opening and reduction in ulcers/erosions/vesicles (p < 0.05) in comparison to 5 mg of aloe vera (n = 21) for the same time. Improvement in burning sensation and pain associated with lesions was not found significant between two groups | |

| Alam S. et al. [59] | Double-blinded, placebo- controlled, parallel-group randomized controlled trial | 60 | Application of aloe vera gel over buccal mucosa, palate, retromolar region, and floor of the mouth twice daily during submucosal injection of hyaluronidase and dexamethasone (n = 15) and surgical treatment (buccal fat pad, nasolabial flap, or collagen membrane, (n = 15) treatment with 6 months of follow up was observed to be a significant adjuvant therapy in reduction of most of the symptoms of OSMF (p < 0.01), in comparison to a similar group of medicines alone, (n = 15) and surgical procedures (n = 15)] with no application of aloe vera. | ||

| Medicinal treatments | Steroids | Goel S. et al. [60] | Longitudinal prospective study | 270 | 4 mg/ml/biweekly injections of Betamethasone diluted in 1.0 ml of 2% xylocaine for 6 months given on buccal mucosa, bilaterally, using an insulin syringe, with a half dose on each side, was showed significant improvement of mouth opening and reduction in burning sensation in a stage II and stage III OSMF group (p < 0.0001), in comparison to a control group which received no treatment over two years. |

| Hyaluronidase | James L. et al. [61] | Retrospective study | 28 | Intralesional injection of Hyaluronidase 1500 IU mixed in 1.5 ml of dexamethasone and 0.5 ml of lignocaine hydrochloride biweekly for 4 weeks showed a significant improvement in mouth opening with net gain of 6 ± 2 mm (92%), reducing the burning sensation (89%), number of painful ulceration (78%) and blanching of oral mucosa (71%) for Grade III OSMF patients. | |

| Colchicine + Hyaluronidase | Krishnamoorthy B. & Khan M [62]. | Comparative prospective study | 50 | 1 mg/ day colchicine tablet and 0.5 ml intralesional Injection hyaluronidase 1500 IU/ once a week (group I, n = 25) for twelve weeks showed a significant improvement in mouth opening (p < 0.05) and reduced burning sensation (33% by second week) in comparison to subjects treated with 0.5 ml intralesional injection of hyaluronidase 1500 IU and 0.5 ml intralesional injection hydrocortisone acetate 25 mg/ml once a week alternatively (group II, n = 25). | |

| Placental extracts | Singh P. et al. [63] | Comparative prospective study | 10 | 2 ml intralesional placental extract mixed with 2 ml of 2% lignocaine HCL weekly for an interval of 8 weeks showed an average improvement in mouth opening by 8.02 mm (average pretreatment mouth opening = 18.49 mm, average posttreatment mouth opening = 26.51 mm) with average marked reduction in burning sensation by 4.9 (average pretreatment burning sensation = 8.0, average posttreatment burning sensation = 3.1). Burning sensation was assessed using visual analogue scale with 0–10, where 0 = no burning sensation and 10 = maximum burning sensation. | |

| Isoxupurine | Bhadage C. J. et al. [64] | Prospective study | 40 | 10 mg Isoxsuprine tablets/ QID with oral physiotherapy (Group A, n = 15) plus 2 ml dexamethasone by intralesional injection with 1500 IU hyaluronidase mixed with 1 ml of 2% lignocaine solution with adrenaline 1:80,000 (Group B, n = 15) for six weeks with a follow up of 4 months, showed a significant improvement in mouth opening (p < 0.05) and burning sensation (p < 0.00001) in comparison to the placebo group (only oral physiotherapy) (Group C, n = 10). | |

| Pentoxifylline | Rajendran R. et al. [65] | Randomized controlled clinical trial | 29 | 400 mg/ TID of Pentoxifylline tablets (n = 14) for seven months showed a significant improvement in mouth opening (p < 0.0001), tongue protrusion (p < 0.05), relief from perioral fibrotic bands (p < 0.0001), subjective symptoms of intolerance to spices (p < 0.0001), burning sensation of mouth (p < 0.0001), tinnitus (p < 0.0001), difficulty in swallowing (p < 0.0001) and difficulty in speech (p < 0.0001) in comparison to the control group (multivitamin with local heat therapy, n = 15). | |

| Oral physiotherapy | Ultrasound + Physiotherapy | Kumar V. et al. [66] | Single arm prospective study | 15 | Ultrasound therapy with 0.7–1.5 W/Cm2 with thumb kneading physiotherapy for six days/ week for two consecutive weeks showed significant improvement in mouth opening (p < 0.001) and reduction of burning sensation. |

| Surgical approaches | Surgery | Kamath V. V [67]. | Systematic Review | – | Lasers, tongue flap, palatal flap, buccal fat pad, nasolabial flap, thigh flaps, split skin grafts, collagen membrane, artificial dermis, human placenta grafts, coronoidectomies, muscle myotomies and oral stents. All surgeries have shown significant improvement in the symptoms of OSMF. However there exist no definite protocols and thus author comments that treatment remains subjective to the operating surgeon. |

Malignant transformation of OSMF

OSMF is classified as an oral potentially malignant disorder (OPMD) [3]. Patients with OSMF have been reported with higher risk of developing oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC), compared to other OPMD’s [71, 72]. Although 7.6% of OSMF cases transformed to oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC) in a 17-year follow up study reported in 1970 [73], other studies with smaller follow up periods report malignant transformation rates ranging from 1.9–9%, [74–76] depending on diagnostic criteria and duration of follow up [77].

Studies suggest that malignant transformation in patients with OSMF differs from those without OSMF. This difference is believed to arise from the mechanism of areca nut carcinogenesis. A retrospective study conducted in China reported that oral cancer originating from OSMF is clinically more invasive and exhibits higher metastasis and recurrence rates compared to “conventional” OSCC [78]. In contrast, Chaturvedi et al. found that OC arising in a background of OSMF represented a clinico-pathologically distinct entity, less aggressive than the “conventional” tobacco-related OC’s seen in India [46]. Better prognostic features associated with OC occurring in a background of OSMF included early tumor stage, thinner lesions, fewer neck metastases with less extra-capsular spread, and more highly differentiated neoplasms. It was suggested that fibrosis in the oral mucosa and tumor stroma, with reduced vascularity, inhibits lymphatic and vascular spread [46].

Studies have shown higher risk of malignant transformation of OSMF when observed with simultaneous oral leukoplakia [77]. A wide array of studies was implemented recently to determine the possible mechanisms involved in malignant transformation, and many have focused their attention on molecular markers which could be helpful for early diagnosis and have possible, helpful therapeutic implications [79–81].

Proposed diagnostic and management approach

As with other lifestyle related diseases, primary prevention at population and individual levels needs to be improved. Space does not permit an exhaustive discussion of the approaches here but, in the case of OSMF, this involves education of the public regarding the dangers of areca nut and tobacco, and legislation to restrict the sale of gutkha and similar products [82–84]. Several Indian states have had success in this regard. Since May 2013, gutkha is banned in 24 states and 5 union territories of India, under the provision of centrally enacted Food Safety and Regulation (Prohibition) Act 2011 [85]. The ban is enforced by the State public health ministry, Food and Drug Administration and the local police. Although there is a significant reduction in the legal purchase of gutkha, the Supreme Court and higher enforcement bodies are still chasing to cease the illegal sale [85, 86].

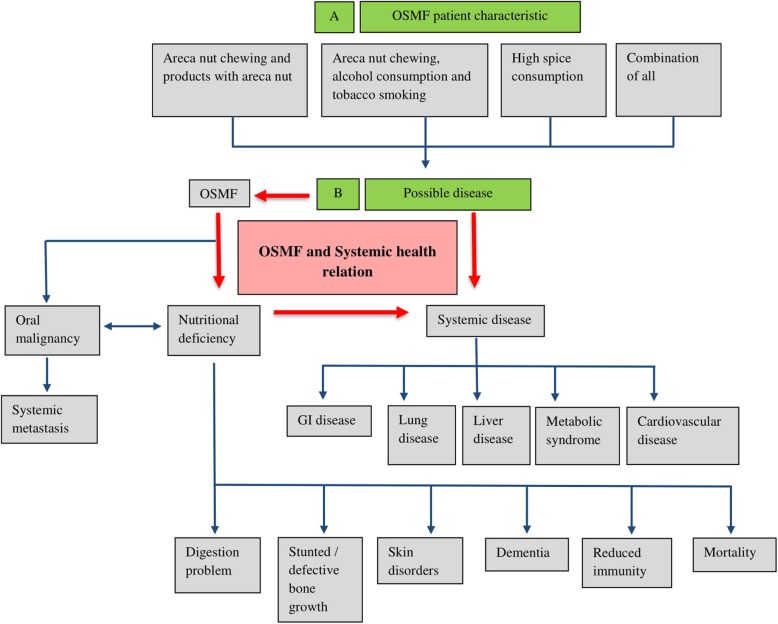

What of the many millions already afflicted? Despite efforts to improve the management of OSMF, many come so late to diagnosis that cure is impossible, and interventions are of limited efficacy. So early diagnosis is of great importance. Further, most OSMF patients chew tobacco as well as an areca nut product, may imbibe unhealthy amounts of alcohol, and abuse other drugs. They often have dietary deficiencies. Therefore, they are at high risk of co-morbidities, including metabolic syndromes, respiratory, gastrointestinal/liver and cardiovascular diseases. (Fig. 4) [87, 88].

Fig. 4.

Oral and Systemic outcomes of OSMF possible in the absence of holistic management

Dependent on their dominant symptoms, patients may seek consultation from either primary care physicians (PCP) or dentists. When examined by a dentist, the diagnostic and treatment approach is likely to be focused on the oral signs and symptoms. Conversely, when patients present to a PCP, the focus of management is likely to be general, with the oral condition under-investigated and under-managed. In most of the world, these patients are not managed by a multidisciplinary team.

We propose an inter-professional approach that may increase rates of early diagnosis of OSMF and potentially malignant disorders/OSCC, with integrated management of both oral and systemic symptoms, improving long-term prognosis, reducing suffering and improving quality of life.

When a patient presents to a dentist, and a clinical diagnosis of OSMF is made, he/she should be referred to their primary care physician with a note of planned dental management. If any underlying systemic disease is diagnosed, the medical treatment plan should be communicated back to the dentist. If no systemic disease is diagnosed, a written medical clearance letter, including an assessment of risks of developing any systemic condition, and recommendations for review visits, should be included.

When a patient presents to a physician, if he/she is a user of areca nut, and especially if restricted mouth opening is present, he/she should be immediately referred to a dentist detailing any planned management of other disease. The dentist should report back to the physician with a treatment plan for OSMF, if present, or dental clearance letter with a suggested risk of developing OSMF or any other oral disease.

This, after all, should be routine in any integrated health care system.

Conclusion

Although studied intensively over many decades, one might say centuries, especially in South Asia, OSMF is hardly recognized and is poorly understood across the globe. The incidence is rising; there has been no significant improvement in management, nor reduction in its high malignant transformation rate.

Better integration of medical and dental services, especially in developing countries, may reduce patients’ suffering and improve their life quality. All health care professions must work together in public education and primary prevention.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Authors’ contributions

This manuscript arises out of discussions between the authors, both at international scientific meetings and in private. All have considerable experience of treating and researching Oral Submucous Fibrosis and similar disorders. The first draft was written by Naman Rao and revised with input from all other authors. All authors have approved the final version.

Funding

Not applicable.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

The clinical photographs shown are from Department of Oral Medicine and Maxillofacial Radiology, K. M. Shah Dental College and Hospital, Sumandeep Vidyapeeth University, Vadodara, Gujarat state, India. The consent for publishing the photograph was taken from the patients.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Naman R. Rao, Email: naman_rao@hms.harvard.edu, Email: naman.rao0@gmail.com

Alessandro Villa, Email: avilla@bwh.harvard.edu.

Chandramani B. More, Email: drchandramanimore@gmail.com

Ruwan D. Jayasinghe, Email: ruwanduminda@yahoo.com

Alexander Ross Kerr, Email: ark3@nyu.edu.

Newell W. Johnson, Email: n.johnson@griffith.edu.au

References

- 1.Pindborg JJ, Sirsat SM. Oral submucous fibrosis. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1966;22(6):764–779. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(66)90367-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ahmad MS, Ali SA, Ali AS, Chaubey KK. Epidemiological and etiological study of oral submucous fibrosis among gutkha chewers of Patna, Bihar, India. J Indian Soc Pedod Prev Dent. 2006;24(2):84–89. doi: 10.4103/0970-4388.26022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.More CB, Das S, Patel H, Adalja C, Kamatchi V, Venkatesh R. Proposed clinical classification for oral submucous fibrosis. Oral Oncol. 2012;48(3):200–202. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2011.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.More CB, Rao NR. Proposed clinical definition for oral submucous fibrosis. J Oral Biol Craniofac Res. 2019;9(4):311–314. doi: 10.1016/j.jobcr.2019.06.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aziz SR. Coming to America: betel nut and oral submucous fibrosis. J Am Dent Assoc. 2010;141(4):423–428. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2010.0194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kerr AR, Warnakulasuriya S, Mighell AJ, Dietrich T, Nasser M, Rimal J, et al. A systematic review of medical interventions for oral submucous fibrosis and future research opportunities. Oral Dis. 2011;17(1 Suppl 1):42–57. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-0825.2011.01791.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Van der Waal I. Historical perspective and nomenclature of potentially malignant or potentially premalignant oral epithelial lesions with emphasis on leukoplakia-some suggestions for modifications. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol. 2018;125(6):577–581. doi: 10.1016/j.oooo.2017.11.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kiran Kumar K, Saraswathi TR, Ranganathan K, Uma Devi M, Elizabeth J. Oral submucous fibrosis: a clinico-histopathological study in Chennai. Indian J Dent Res. 2007;18(3):106–111. doi: 10.4103/0970-9290.33785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pindborg JJ, Kalapesi ILK, Kale SA, Singh B, Taleyarkhan BN. Frequency of oral leukoplakia and related conditions among 10,000 Bombayites. Preliminary Rep, J Ind Dent Assoc. 1965;37:228–229. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pindborg JJ, Chawla TN, Misra RK, Nagpaul RK, Gupta VK. Frequency of oral carcinoma, leukoplakia, leukokeratosis, leukoedema, sub mucous fibrosis and lichen planus in 10,000 Indians in Lucknow, Uttar Pradesh. India Preliminary J Dent Res. 1965;44(3):61. doi: 10.1177/00220345650440032901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pindborg JJ, Bhat M, Devnath KR, Narayan HR, Ramchandra S. Frequency of oral white lesions in 10,000 individuals in Bangalore, South India, preliminary report. Ind J Med Sci. 1966;2:349–352. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zachariah J, Mathew B, Varma NA, Iqbal AM, Pindborg JJ. Frequency of oral mucosal lesions among 5000 individuals in Trivandrum, South India. Preliminary Rep J Indian Dent Assoc. 1966;38(11):290–294. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pindborg JJ, Mehta FS, Gupta PC, Daftary DK. Prevalence of oral submucous fibrosis among 50,915 Indian villagers. Brit J Cancer. 1968;22:646–654. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1968.76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wahi PN, Mittal VP, Lahiri B, Luthera UK, Seth RK, Arma GD. Epidemiological study of precancerous lesions of the oral cavity: A preliminary report. Ind J Med Res. 1970;50:1361–1391. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mehta FS, Gupta PC, Daftary DK, Pindborg JJ, Choksi SK. An epidemiologic study of oral cancer and precancerous conditions among 101,761 villagers in Maharashtra. India Int J Cancer. 1972;10(1):134–141. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910100118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lay KM, Sein K, Myint A, Ko SK, Pindborg JJ. Epidemiologic study of 600 villagers of oral precancerous lesions in Bilugyun: preliminary report. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 1982;10(3):152–155. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.1982.tb01341.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Seedat HA, Vanwyk CW. Betelnut chewing and sub mucous fibrosis in Durban. South Africa Med J. 1988;74(3):568–571. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tang JG, Jian XF, Gao ML, Ling TY, Zhang KH. Epidemiological survey of oral submucous fibrosis in Xiangtan City, Hunan Province. China Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 1997;25(2):177–180. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.1997.tb00918.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Patil PB, Bathi R, Chaudhari S. Prevalence of oral mucosal lesions in dental patients with tobacco smoking, chewing, and mixed habits: a cross-sectional study in South India. J Fam Community Med. 2013;20(2):130–135. doi: 10.4103/2230-8229.114777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hazarey VK, Erlewad DM, Mundhe KA, Ughade SN. Oral submucous fibrosis: study of 1000 cases from Central India. J Oral Pathol Med. 2007;36(1):12–17. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.2006.00485.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mathew AL, Pai KM, Sholapurkar AA, Vengal M. The prevalence of oral mucosal lesions in patients visiting a dental school in southern India. Indian J Dent Res. 2008;19(2):99–103. doi: 10.4103/0970-9290.40461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mehrotra R, Pandya S, Chaudhary AK, Kumar M, Singh M. Prevalence of oral pre-malignant and malignant lesions at a tertiary level hospital in Allahabad. India Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2008;9(2):263–265. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sharma R, Raj SS, Miahra G, Reddy YG, Shenava S, Narang P. Prevalence of oral submucous fibrosis in patients visiting dental college in rural area of Jaipur, Rajasthan. J Indian Acad Oral Med Radiol. 2012;24(1):1–4. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Agarwal A, Chandel S, Singh N, Singhal A. Use of tobacco and oral sub mucous fibrosis in teenagers. J Dent Sci Res. 3(3):1–4.

- 25.Bhatnagar P, Rai S, Bhatnagar G, Kaur M, Goel S, Prabhat M. Prevalence study of oral mucosal lesions, mucosal variants, and treatment required for patients reporting to a dental school in North India: in accordance with WHO guidelines. J Fam Community Med. 2013;20(1):41–48. doi: 10.4103/2230-8229.108183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Burungale SU, Durge PM, Burungale DS, Zambare MB. Epidemiological study of premalignant and malignant lesions of the Oral cavity. J Acad Ind Res (JAIR) 2014;2(9):519–523. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kumar NN, Aravinda K, Dhillon M, Gupta S, Reddy S, Srinivas RM. Prevalence of oral submucous fibrosis among habitual gutkha and areca nut chewers in Moradabad district. J Oral Biol Craniofac Res. 2014;4:8–13. doi: 10.1016/j.jobcr.2013.10.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Patil S, Doni B, Maheshwari S. Prevalence and distribution of oral mucosal lesions in a geriatric Indian population. Can Geriatr J. 2015;18(1):11–14. doi: 10.5770/cgj.18.123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Singh P, Mittal R, Chandak S, Bhondey A, Rathi A, Chandwani M. Prevalence of oral submucous fibrosis in children of rural area of Nagpur, Maharashtra, India. Int J Prev Clin Dent Res. 2016;3(4):243–245. doi: 10.5005/jp-journals-10052-0054. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tyagi VN, More MD. Prevalence of Oral submucous fibrosis at OPD of ENT department of SMBT Institute of Medical Sciences, Nasik. J Appl Med Sci. 2018;6(1F):395–398. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yang S, Wang Y, Su N, Yu H, Wei C, Yu C, Chang Y. Changes in prevalence of precancerous oral submucous fibrosis from 1996 to 2013 in Taiwan: a nationwide population-based retrospective study. J Formos Med Assoc. 2018;117(2):147–152. doi: 10.1016/j.jfma.2017.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.More C, Rao NR, More S, Johnson NW. Reasons for initiation of areca nut and related products in patients with oral submucous fibrosis within an endemic area in Gujarat. India Subst Use Misuse. 10.1080/10826084.2019.1660678. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 33.Cox SC, Walker DM. Oral submucous fibrosis. Rev Aust Dent J. 1996;41(5):294–299. doi: 10.1111/j.1834-7819.1996.tb03136.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.More C, Peter R, Nishma G, Chen Y, Rao N. Association of Candida species with Oral submucous fibrosis and Oral leukoplakia: a case control study. Ann Clin Lab Res. 2018;06(3):248. doi: 10.21767/2386-5180.100248. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.More C, Gupta S, Joshi J, Varma S. Classification system of Oral submucous fibrosis. J Indian Acad Oral Med Radiol. 2012;24(1):24–29. doi: 10.5005/jp-journals-10011-1254. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.More C, Shilu K, Gavli N, Rao NR. Etiopathogenesis and clinical manifestations of oral submucous fibrosis, a potentially malignant disorder: an update. Int J Curr Res. 2018;10(07):71816–71820. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gupta PC, Warnakulasuriya S. Global epidemiology of areca nut usage. Addict Biol. 2002;7(1):77–83. doi: 10.1080/13556210020091437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Srinivasan M, Jewell SD. Evaluation of TGF-alpha and EGFR expression in oral leukoplakia and oral submucous fibrosis by quantitative immunohistochemistry. Oncol. 2001;61(4):284–292. doi: 10.1159/000055335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Anila Namboodiripad PC, Cystatin C. Cystatin C: its role in pathogenesis of OSMF. J Oral Biol Craniofac Res. 2014;4(1):42–46. doi: 10.1016/j.jobcr.2014.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hernandez BY, Zhu X, Goodman MT, Gatewood R, Mendiola P, Quinata K, et al. Betel nut chewing, oral premalignant lesions, and the oral microbiome. PLoS One. 2017;12(2):e0172196. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0172196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.More CB, Gavli N, Chen Y, Rao NR. A novel clinical protocol for therapeutic intervention in oral submucous fibrosis: an evidence based approach. J Oral Maxillofac Pathol. 2018;22(3):382–391. doi: 10.4103/jomfp.JOMFP_223_18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.More C, Shah P, Rao N, Pawar R. Oral submucous fibrosis: an overview with evidence-based management. Int J Oral Health Sci Adv. 2015;3(3):40–49. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pillai R, Balaram P, Reddiar KS. Pathogenesis of oral submucous fibrosis. Relationship to risk factors associated with oral cancer. Cancer. 1992;69(8):2011–2020. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19920415)69:8<2011::AID-CNCR2820690802>3.0.CO;2-B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Seedat HA, van Wyk CW. Submucous fibrosis in non-betel nut chewing subjects. J Biol Buccale. 1988;16(1):3–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rajalalitha P, Vali S. Molecular pathogenesis of oral submucous fibrosis—a collagen metabolic disorder. J Oral Pathol Med. 2005;34(6):321–328. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.2005.00325.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chaturvedi P, Vaishampayan SS, Nair S, Nair D, Agarwal JP, Kane SV, et al. Oral squamous cell carcinoma arising in background of oral submucous fibrosis: a clinicopathologically distinct disease. Head Neck. 2013;35(10):1404–1409. doi: 10.1002/hed.23143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.More C, Pawar R, Rao N, Shah P, Gavli N. Oral ulcer: an overview with an emphasis on differential diagnosis. Int J Oral Health Sci Adv. 2015;3(4):1–13. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Dyavanagoudar SN. Oral submucous fibrosis: review on etiopathogenesis. J Cancer Sci Ther. 2009;1(2):72–77. doi: 10.4172/1948-5956.1000011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lee CK, Tsai MT, Lee HC, Chen HM, Chiang CP, Wang YM, et al. Diagnosis of oral submucous fibrosis with optical coherence tomography. J Biomed Opt. 2009;14(5):054008. doi: 10.1117/1.3233653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tadakamadla J, Kumar S, Lalloo R, Gandhi Babu DB, Johnson NW. Impact of oral potentially malignant disorders on quality of life. J Oral Pathol Med. 2018;47(1):60–65. doi: 10.1111/jop.12620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hebbar PB, Sheshaprasad R, Gurudath S, Pai A, Sujatha D. Oral submucous fibrosis in India: are we progressing?? Indian J Cancer. 2014;51(3):222–226. doi: 10.4103/0019-509X.146724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Passi D, Bhanot P, Kacker D, Chahal D, Atri M, Panwar Y. Oral submucous fibrosis: newer proposed classification with critical updates in pathogenesis and management strategies. Natl J Maxillofac Surg. 2017;8(2):89. doi: 10.4103/njms.NJMS_32_17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Arakeri G, Brennan PA. TFM classification and staging of oral submucous fibrosis: A new proposal. J Oral Pathol Med. 2018;47(5):539. doi: 10.1111/jop.12700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gnanam A. Kannadasan Kamal, Venkatachalapathy S, David Jasline. Multimodal treatment options for oral submucous fibrosis, SRM University. J Dent Sci. 2010;1(1):26–29. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Karemore TV, Motwani M. Evaluation of the effect of newer antioxidant lycopene in the treatment of oral submucous fibrosis. Indian J Dent Res. 2012;23(4):524–528. doi: 10.4103/0970-9290.104964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hazarey VK, Sakrikar AR, Ganvir SM. Efficacy of curcumin in the treatment for oral submucous fibrosis - a randomized clinical trial. J Oral Maxillofac Pathol. 2015;19(2):145–152. doi: 10.4103/0973-029X.164524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Maher R, Aga P, Johnson NW, Sankaranarayanan R, Warnakulasuriya S. Evaluation of multiple micronutrient supplementation in the management of oral submucous fibrosis in Karachi. Pakistan Nutr Cancer. 1997;27(1):41–47. doi: 10.1080/01635589709514499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Patil S, Al-Zarea BK, Maheshwari S, Sahu R. Comparative evaluation of natural antioxidants spirulina and aloe vera for the treatment of oral submucous fibrosis. J Oral Biol Craniofac Res. 2015;5(1):11–15. doi: 10.1016/j.jobcr.2014.12.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Alam S, Ali I, Giri KY, Gokkulakrishnan S, Natu SS, Faisal M, et al. Efficacy of aloe vera gel as an adjuvant treatment of oral submucous fibrosis. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol. 2013;116(6):717–724. doi: 10.1016/j.oooo.2013.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Goel S, Ahmed J. A comparative study on efficacy of different treatment modalities of oral submucous fibrosis evaluated by clinical staging in population of southern Rajasthan. J Cancer Res Ther. 2015;11(1):113–118. doi: 10.4103/0973-1482.139263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.James L, Shetty A, Rishi D, Abraham M. Management of oral submucous fibrosis with injection of hyaluronidase and dexamethasone in grade III oral submucous fibrosis. J Int Oral Health. 2015;7(8):82–85. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Krishnamoorthy B, Khan M. Management of oral submucous fibrosis by two different drug regimens: a comparative study. Dent Res J (Isfahan) 2013;10(4):527–532. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Singh P, Pandey A, Shingh A, Ahuja T, Sharma S, Bhagalia S, Trehan M. Efficacy of intralesional placental extract, dexamethasone and hyaluronidase in treatment of oral submucous fibrosis: a comparative study. JK Pract. 2016;21(1–2):29–34. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Bhadage CJ, Umarji HR, Shah K, Välimaa H. Vasodilator isoxsuprine alleviates symptoms of oral submucous fibrosis. Clin Oral Investig. 2013;17(5):1375–1382. doi: 10.1007/s00784-012-0824-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Rajendran R, Rani V, Shaikh S. Pentoxifylline therapy: a new adjunct in the treatment of oral submucous fibrosis. Indian J Dent Res. 2006;17(4):190–198. doi: 10.4103/0970-9290.29865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Vijayakumar M, Priya D. Physiotherapy for improving mouth opening & tongue protrusion in patients with Oral submucous fibrosis (OSMF) – case series. Int J Pharm Sci Health Care. 2013;3(2):50–58. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kamath VV. Surgical interventions in Oral submucous fibrosis: a systematic analysis of the literature. J Maxillofac Oral Surg. 2015;14(3):521–531. doi: 10.1007/s12663-014-0639-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Koneru A, Hunasgi S, Hallikeri K, Surekha R, Nellithady GS. Vanishree M. Treat Modalities OSMF J Adv Clin Res Insights. 2014;1(2):64–72. doi: 10.15713/ins.jcri.18. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Arakeri G, Rai KK, Boraks G, Patil SG, Aljabab AS, Merkx MA, et al. Current protocols in the management of oral submucous fibrosis: an update. J Oral Pathol Med. 2017;46(6):418–423. doi: 10.1111/jop.12583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Warnakulasuriya S, Kerr AR. Oral submucous fibrosis: a review of the current management and possible directions for novel therapies. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol. 2016;122(2):232–241. doi: 10.1016/j.oooo.2016.02.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Heck JE, Marcotte EL, Argos M, Parvez F, Ahmed A, Islam T, et al. Betel quid chewing in rural Bangladesh: prevalence, predictors and relationship to blood pressure. Int J Epidemiol. 2012;41(2):462–471. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyr191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Aziz SR. Oral submucous fibrosis: case report and review of diagnosis and treatment. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2008;66(11):2386–2389. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2008.06.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Murti P, Bhonsle R, Pindborg JJ, Daftary D, Gupta P, Mehta FS. Malignant transformation rate in oral submucous fibrosis over a 17-year period. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 1985;13(6):340–341. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.1985.tb00468.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Paymaster JC. Cancer of the buccal mucosa; a clinical study of 650 cases in Indian patients. Cancer. 1956;9(3):431–435. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(195605/06)9:3<431::AID-CNCR2820090302>3.0.CO;2-T. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Hsue SS, Wang WC, Chen CH, Lin CC, Chen YK, Lin LM. Malignant transformation in 1458 patients with potentially malignant oral mucosal disorders: a follow-up study based in a Taiwanese hospital. J Oral Pathol Med. 2007;36(1):25–29. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.2006.00491.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Arakeri G, Patil SG, Aljabab AS, Lin KC, Merkx MA, Gao S, et al. Oral submucous fibrosis: an update on pathophysiology of malignant transformation. J Oral Pathol Med. 2017;46(6):413–417. doi: 10.1111/jop.12582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Ray JG, Ranganathan K, Chattopadhyay A. Malignant transformation of oral submucous fibrosis: overview of histopathological aspects. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol. 2016;122(2):200–209. doi: 10.1016/j.oooo.2015.11.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Guo F, Jian XC, Zhou SH, Li N, Hu YJ, Tang ZG. A retrospective study of oral squamous cell carcinomas originated from oral submucous fibrosis. Zhonghua Kou Qiang Yi Xue Za Zhi. 2011;46(8):494–497. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Shah JP, Batsakis JG, Johnson NW. Oral cancer. London: Dunitz; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 80.Shah JP, Johnson NW. Oral and oropharyngeal cancer. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 81.Bazarsad S, Zhang X, Kim K-Y, Illeperuma R, Jayasinghe RD, Tilakaratne WM, et al. Identification of a combined biomarker for malignant transformation in oral submucous fibrosis. J Oral Pathol Med. 2016;46(6):431–438. doi: 10.1111/jop.12483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.McKay Ailsa J., Patel Raju K. K., Majeed Azeem. Strategies for Tobacco Control in India: A Systematic Review. PLOS ONE. 2015;10(4):e0122610. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0122610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Arora M, Tewari A, Tripathy V, Nazar GP, Juneja NS, Ramakrishnan L, et al. Community-based model for preventing tobacco use among disadvantaged adolescents in urban slums of India. Health Promot Int. 2010;25:143–152. doi: 10.1093/heapro/daq008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Kumar MS, Sarma PS, Thankappan KR. Community-based group intervention for tobacco cessation in rural Tamil Nadu, India: a cluster randomized trial. J Subst Abus Treat. 2012;43:53–60. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2011.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Prabhu RV. A need to spread awareness regarding the ill effects of Arecanut and its commercial products on Oral health. Tropical Medicine & Surgery. 2014;02(03). Garg a, Chaturvedi P, Gupta PC. A review of the systemic adverse effects of areca nut or betel nut. Indian J Med Paediatr Oncol. 2014;35(1):3–9. doi: 10.4103/0971-5851.133702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Arora M, Madhu R. Banning smokeless tobacco in India: policy analysis. Indian J Cancer. 2012;49(4):336. doi: 10.4103/0019-509X.107724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Garg A, Chaturvedi P, Gupta PC. A review of the systemic adverse effects of areca nut or betel nut. Indian J Med Paediatr Oncol. 2014;35(1):3–9. doi: 10.4103/0971-5851.133702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Chakrabarti S, Mishra A, Agarwal JP, Garg A, Nair D, Chaturvedi P. Acute toxicities of adjuvant treatment in patients of oral squamous cell carcinoma with and without submucous fibrosis: a retrospective audit. J Cancer Res Ther. 2016;12(2):932–937. doi: 10.4103/0973-1482.174187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.