Abstract

Purpose:

We performed this study to determine the association between serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D [25(OH) D] level and myopia in adults.

Methods:

A total of 25,199 subjects aged ≥20 years were included from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2008–2012. Blood 25(OH)D levels were evaluated from blood samples. Refractive error was measured without cycloplegia. Myopia and high myopia were defined as ≥-0.50 diopters (D) and ≥-6.0 D, respectively. Other covariates such as education, physical activity, and economic status were obtained from interviews.

Results:

Linear regression analysis showed that as 25(OH) D level increased by 1 ng/mL, myopic refractive error significantly decreased by 0.01 D (P < 0.001) after adjusting for potential confounders including sex, age, height, education level, economic status, physical activity, and sunlight exposure time. The odds ratios for myopia was 0.75 (95% Confidence interval [CI]; 0.67–0.84, P < 0.001) in the highest 25(OH) D quintile compared to the lowest quintile. The odds ratios for high myopia was 0.63 (95% CI; 0.47–0.85, P < 0.001) in the highest 25(OH)D quintile compared to the lowest quintile.

Conclusion:

Serum 25(OH)D level was inversely associated with myopia in Korean adults.

Keywords: 25-hydroxyvitamin D, adults, high myopia, Korean, myopia

Myopia is a common ocular condition that leads to visual disturbance and affects 1.6 billion people worldwide.[1] Although it can be considered a benign condition, myopia causes severe public health problems and economic burdens.[2,3,4] For example, an economic burden for myopia in Singapore is 755 million US dollars.[5] The prevalence of myopia had increased over several decades at an epidemic rate, especially in East Asia.[6] High myopia which is more than – 6.0 diopters(D) may be associated with vision-threatening ocular diseases such as glaucoma, macular degeneration, and retinal detachment.[1,7] Recently, an increase of outdoor time showed a protective effect against myopia progression in both cross-sectional studies[8,9] and longitudinal studies.[10,11,12] Two intervention studies have reported a decrease in the progression of myopia by increasing outdoor time,[13] and a 3-year prospective cohort study has also reported positive effects.[10] It was postulated that increased intensity of sunlight outdoors induces an increase of dopamine release in the retina which reduces growth in the eye and this hypothesis has been demonstrated in a series of experimental animal studies.[14,15,16,17]

Vitamin D has a role not only in calcium regulation function but also other biological functions such as antioxidation or anti-inflammation.[18,19,20] Inverse associations between vitamin D and chronic inflammation were reported in several human studies.[21] Vitamin D was also found to be related to various ocular diseases, suggesting that vitamin D can be used as therapeutic potential.[22] Previous reports using a Korean representative population demonstrated that vitamin D was inversely associated with age-related macular disease,[23] diabetic retinopathy,[24] cataract,[25] and dry eye syndrome.[26] No studies have been conducted so far about the association between vitamin D levels and myopia in adults. Although a previous study has reported positive association between vitamin D and myopia in Korean National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (KNHANES), this study included adolescents aged 13–18 years, not adults.[27] The adolescents and adults would have different risk factors for myopia because eyes of adults do not show axial elongation.

Some authors documented that the prevalence of myopia is 96.5% in Seoul, a metropolitan city, and 83.3% in Jeju, a rural island, in 19-years-old male conscripts of South Korea.[28,29] In addition, they have reported an extreme increase in myopia over 40 years among Korean adults.[30] This is a complex mix of mechanisms. South Korea has changed from a poorly educated society 100 years ago to one which leads the world in educational outcomes according to the Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) surveys.[6] This combined with a tendency to spend less time outdoors, associated perhaps with both urbanization and intense study pressures, is likely to be the social cause of the increased prevalence of myopia in the younger generations. Older Koreans are less myopic because they are less educated; more likely to have spent a lot of time outdoors as a child, to have occupations that take them outdoors as adults but as they age, spend less time outdoors particularly when they cease working. People who spend less time outdoors have less opportunity for sunlight exposure, which is the stimulus for production of vitamin D up to about 90%. In this study, therefore, we examined the possible association between serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D [25(OH) D] levels and myopia in Korean adults using representative population-based data from KNHANES. In addition, the result of the present study was compared to those of our previous reports including other ocular diseases.

Methods

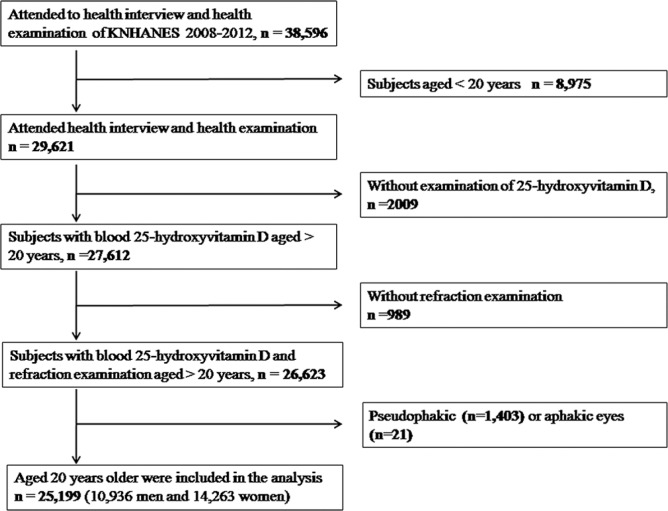

The present study adhered to the Declaration of Helsinki. In addition, our study was approved by the institutional review board. We used data from KNHANES. Study design and the methods used have been reported elsewhere.[31,32] KNHANES is a population-based cross-sectional and a nationwide study. For the present study, we included data obtained from KNHANES 2008–2012. For the current study, 38,596 individuals who participated in KNHANES were enrolled. 8,975 participants aged <20 years, 2,009 participants without blood 25(OH)D levels, and 989 participants without refraction examination were excluded from the study. Thus, 25,199 participants were used in the final analysis [Fig. 1].

Figure 1.

Flow diagram showing the selection of study participants

The analysis of blood 25(OH)D levels have been described in the other studies.[23,24,25,26] A radioimmunoassay kit (DiaSorin Inc., Stillwater, MN, USA) was used for measurement of 25(OH)D levels using a gamma counter (1470 Wizard, Perkin-Elmer, Finland), followed by the standardization of vitamin D procedure.[33] After an 8-h fast, blood samples were collected and they were transported to the Neodin Medical Institute after appropriate process. The detection limit of 25(OH) D was 1.2 ng/ml.

Refraction of the right eye without cycloplegia was measured using an auto-refractor (KR-8800®; Topcon, Tokyo, Japan) with spherical equivalents in both eyes being correlated (Pearson's correlation coefficient; 0.94, P <.001). We changed refractive error into spherical equivalents by adding spherical refractive error to the half of astigmatic refractive error. The definition of myopia and high myopia was spherical equivalent to be ≥-0.50 D and ≥-6.0 D, respectively.

The measurement of other covariates was described in detail in the previous report.[34] Body mass indices were calculated by dividing weight (kg) by height (m)2. The educational level of subjects was classified into 4 categories: ≤ elementary school graduate, middle school graduate, high school graduate, and ≥ university graduate. Economic status was grouped into quartiles according to annual individual earnings. Physical activity level was determined as actual days per week of vigorous-, moderate-, or mild-intensity activity over 20 min/day. Vigorous physical activity was one which led to be out of breath at least over 20 mins at a time. Moderate physical activity was one which led to be somewhat out of breath at least over 20 mins at a time. The mild-intensity activity was walking at least over 10 mins at a time. Sunlight exposure time was classified as less than 5 hrs/day or more.

The SPSS® version 18.0 (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA) was used for statistical analyses. Since KNHANES used a stratified, multistage sampling method, we incorporated sampling weights as well as strata, sampling units in the statistical analysis. Continuous variables were expressed with the mean and standard error (SE), and categorical variables were presented with the percentage and SE. To compare the patients' demographic characteristics, Chi-square tests or ANOVA were used. Logistic regression analyses were used after the categorization of 25(OH) D levels into quintiles. To evaluate the confounding effect by confounders, we calculated three odds ratio (OR); the crude OR (Model 1), age and sex-adjusted OR (Model 2), and sex, age, height, economic status, education level, and physical activity adjusted OR (Model 3). For the logistic regression analysis, we tested multicollinearity and exclude variables that have a variance inflation factor more than 5. P values less than 0.05 were regarded as statistical significance.

Results

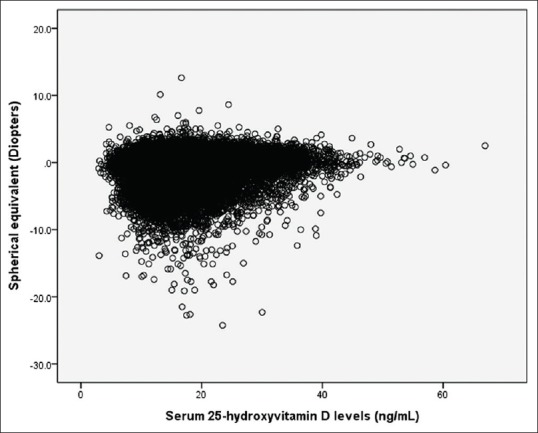

The average serum 25(OH) D level was 17.8 ng/mL (standard error [SE], 0.1 ng/mL). The prevalence of myopia and high myopia was 55.5% (SE; 0.4%, 95% confidence interval [CI]; 54.3–56.7) and 4.7% (SE; 0.2%, 95% CI; 4.4–5.1), respectively. Table 1 showed that subjects with myopia had tendency to have younger age (P < 0.001), taller height (P < 0.001), higher education levels (P < 0.001), higher income levels (P = 0.012), more vigorous physical activity (P = 0.032), more walk (P =0.002), a shorter sun exposure time (P < 0.001), and a lower serum vitamin D level (P < 0.001) than those without myopia. Vitamin D and refractive error was significantly correlated (Pearson correlation coefficient = 0.136, P < 0.001, Fig. 2).

Table 1.

Associations of baseline variables with myopia (< -0.5 D) and high myopia (< -6.0 D) among Korean adults

| Characteristics | Nonmyopia | Myopia | P | Participants | Pseudophakic or aphakic | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number (%) | 13052 (45.0) | 12147 (55.0 ) | 0.082 | 25199 | 1424 (3.7) | <.001 |

| Refractive error (diopters) | 0.4 (0.0) | -2.5 (0.0) | <.001 | -1.0 (0.0) | -0.4 (0.1) | <.001 |

| Age (yrs) | 51.4±0.2 | 38.2±0.1 | <.001 | 44.8±0.1 | 68.8±0.5 | <.001 |

| Male (%) | 50.1 (0.5) | 51.4 (0.5) | <.082 | 50.8 (0.3) | 39.4 (1.6) | <.001 |

| Height (cm) | 162.5±0.1 | 165.8±0.1 | <.001 | 164.2±0.1 | 157.0±0.3 | <.001 |

| Education level | <.001 | <.001 | ||||

| <Elementary school | 29.5 (0.6) | 6.6 (0.3) | 16.9 (0.4) | 62.9 (1.7) | ||

| Middle school | 15.2 (0.4) | 6.3 (0.3) | 10.3 (0.3) | 10.3 (1.0) | ||

| High school | 34.7 (0.6) | 44.1 (07) | 39.9 (0.5) | 18.2 (1.4) | ||

| >University | 20.6 (0.6) | 43.0 (0.7) | 33.0 (0.6) | 8.6 91.0) | ||

| Economic status | 0.012 | 0.870 | ||||

| 1st quartile(low) | 26.2 (0.6) | 25.6 (0.7) | 25.9 (0.5) | 26.7 (1.4) | ||

| 2nd quartile | 26.5 (0.6) | 24.6 (0.6) | 25.4 (0.5) | 25.7 (1.5) | ||

| 3rd quartile | 24.1 (0.5) | 25.4 (0.6) | 24.8 (0.4) | 24.7 (1.3) | ||

| 4th quartile | 23.2 (0.6) | 24.4 (0.7) | 23.9 (0.6) | 22.9 (1.4) | ||

| Physical activity | ||||||

| Vigorous (day/week) | 2.0 (0.0) | 2.1 (0.0) | 0.032 | 2.0 (0.0) | 1.6 (0.1) | <.001 |

| Moderate (day/week) | 2.3 (0.0) | 2.3 (0.0) | 0.797 | 2.3 (0.0) | 2.1 (0.1) | 0.001 |

| Walking (day/week) | 5.0 (0.0) | 5.1 (0.0) | 0.002 | 5.1 (0.0) | 4.8 (0.1) | 0.018 |

| Sun exposure time ( > 5 h) | 21.5 (0.7) | 12.9 (0.5) | <.001 | 16.8 (0.5) | 22.2 (1.5) | <.001 |

| Vitamin D (ng/mL) | 18.7 (0.1) | 17.0 (0.1) | <.001 | 17.8 (0.1) | 18.8 (0.1) | <.001 |

Data are expressed as means±standard deviation or frequency (%). The ANOVA was used for continuous variables, and the Chi-square test was used for categorical variables

Figure 2.

Correlation between 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels (ng/mL) and refractive error (diopters), Pearson correlation coefficient = 0.136, P < 0.001

In analysis for association between vitamin D and refractive error, linear regression analysis showed that as 25(OH) D level increased by 1 ng/mL, myopic refractive error significantly decreased by 0.02 D (P < 0.001) and 0.01 D (P < 0.001) before and after adjusting for potential confounders, respectively [Table 2].

Table 2.

Linear regression analysis between blood 25-Hydroxyvitamin D and refractive error (diopters) among adults

| Characteristics | Model 1 | Model 2 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β coefficient | 95% CI | P | β coefficient | 95% CI | P | |

| Vitamin D (ng/mL) | 0.02 | 0.01, 0.02 | <.001 | 0.01 | 0.01, 0.02 | <.001 |

| Sex (female) | 0.02 | -0.04, 0.08 | 0.532 | -0.09 | -0.19, -0.05 | 0.063 |

| Age (yrs) | 0.06 | 0.05, 0.06 | <.001 | 0.04 | 0.04, 0.05 | <.001 |

| Height (cm) | -0.00 | -0.01, 0.05 | 0.653 | |||

| Education level | -0.29 | -0.33, -0.25 | <.001 | |||

| Economic status | -0.02 | -0.05, 0.19 | <.001 | |||

| Physical activity | ||||||

| Vigorous (day/week) | 0.03 | 0.01, 0.05 | 0.001 | |||

| Moderate (day/week) | 0.01 | -0.01, 0.02 | 0.318 | |||

| Walking (day/week) | -0.02 | -0.02, -0.02 | 0.022 | |||

| Sunl exposure time (>5 h) | 0.13 | 0.05-0.21 | 0.001 | |||

Model 1: adjusted for sex and age. Model 2: adjusted for sex, age, height, education level, economic status, physical activity. Crude β coefficient (95% CI) was 0.05 (0.04-0.52)

In analysis for association between vitamin D and myopia, logistic regression analysis showed OR for myopia was 0.98 (95% confidence interval [CI], 0.97–0.98) before adjustment as 25(OH) D level increased by 1 ng/mL, and this association was not changed after adjustment (OR; 0.98, 95% CI, 0.98–0.99). For high myopia, OR was 0.97 (95% CI, 0.96–0.99) as 25(OH) D level increased by 1 ng/mL, and this association was not changed after adjustment (OR; 0.97, 95% CI, 0.96–0.99, Table 3).

Table 3.

Logistic regression for the association between blood 25-Hydroxyvitamin D and myopia (≤ -0.5 diopter [D]) or high myopia (≤ -6.0 D) among adults

| Characteristics | Myopia (< -0.5 D) | High myopia (< -6.0 D) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | P | Model 2 | P | Model 1 | P | Model 2 | P | |

| Vitamin D (ng/mL) | 0.98 (0.97-0.98) | <.001 | 0.98 (0.98-0.99) | <.001 | 0.97 (0.96-0.99) | 0.001 | 0.97 (0.96-0.99) | 0.009 |

| Sex (female) | 0.98 (0.92-1.05) | 0.703 | 1.11 (0.99-1.24) | 0.063 | 0.79 (0.68-0.92) | 0.003 | 1.35 (1.06-1.72) | 0.014 |

| Age (yrs) | 0.94 (0.93-0.94) | <.001 | 0.95 (0.94-0.95) | <.001 | 0.94 (0.94-0.95) | <.001 | 0.95 (0.95-0.96) | <.001 |

| Height (cm) | 1.00 (0.99-1.00) | 0.522 | 1.00 (0.99-1.01) | 0.535 | ||||

| Education level | <.001 | <.001 | ||||||

| <Elementary school | reference | reference | ||||||

| Middle school | 0.99 (0.87-1.12) | 1.12 (0.69-1.80) | ||||||

| High school | 1.53 (1.36-1.71) | 1.72 (1.21-2.44) | ||||||

| >University | 2.37 (2.09-2.68) | 2.51 (1.73-3.66) | ||||||

| Economic status | 0.104 | 0.472 | ||||||

| 1st quartile (low) | reference | reference | ||||||

| 2nd quartile | 0.90 (0.82-0.99) | 0.98 (0.78-1.24) | ||||||

| 3rd quartile | 0.96 (0.87-1.06) | 1.07 (0.85-1.35) | ||||||

| 4th quartile | 0.90 (0.81-1.00) | 1.17 (0.92-1.48) | ||||||

| Physical activity | ||||||||

| Vigorous (day/week) | 0.98 (0.96-1.01) | 0.324 | 0.96 (0.92-1.02) | 0.234 | ||||

| Moderate (day/week) | 1.00 (0.98-1.02) | 0.685 | 1.00 (0.96-1.04) | 0.826 | ||||

| Walking (day/week) | 1.00 (0.98-1.01) | 0.829 | 1.04 (1.00-1.07) | 0.021 | ||||

| Sun exposure time ( >5 h) | 0.84 (0.76-0.92) | 0.001 | 0.88 (0.68-1.13) | |||||

Model 1: adjusted for sex and age. Model 2: adjusted for sex, age, height, education level, economic status, physical activity, and sunlight exposure time. Crude odds ratios (ORs) for myopia and high myopia were 0.95 (0.95-0.96) and 0.95 (0.9--0.96). ORs were expressed with 95% confidence intervals

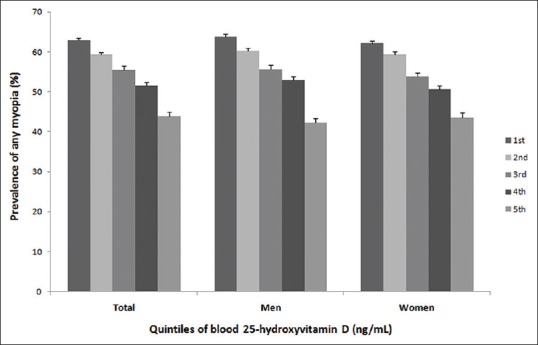

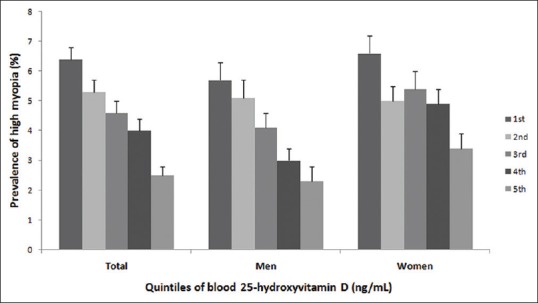

After the categorization of vitamin D levels into quintiles, the prevalence of myopia decreased from 62.9% in the lowest quintile to 43.8% in the highest quintile (P < 0.001, Fig. 3). The prevalence of high myopia decreased significantly from 6.4% in the lowest quintile to 2.5% in the highest quintile (P < 0.001, Fig. 4).

Figure 3.

The prevalence of myopia by blood vitamin D quintiles, P < 0.001

Figure 4.

The prevalence of high myopia by blood vitamin D quintiles, P < 0.001

The adjusted odds of myopia decreased as 25(OH)D quintiles increased after controlling potential confounders (P for trend <0.001, Table 4). The OR for myopia in the highest vitamin D quintile was 0.47 (95%CI; 0.42–0.52) compared with lowest vitamin D quintile. After adjustment of covariates, ORs for myopia increased to 0.75 (95%CI; 0.67–0.84). Stratified analysis by gender demonstrated that adjusted OR for myopia in highest versus lowest quintile was 0.70 (95% CI; 0.59–0.82) in men and 0.79 (95% CI; 0.68–0.91) in women.

Table 4.

Association between blood 25-hydroxyvitamin D and prevalence of myopia among adults

| Vitamin D quintiles (ng/mL) | Case/total number | Prevalence | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Both gender | 55.0 (0.4) | ||||

| Quintile 1 (<12.6) | 2911/5074 | 62.9 (0.8) | reference | reference | reference |

| Quintile 2 (12.6-15.6) | 2709/5074 | 59.4 (0.9) | 0.86 (0.78-0.95)* | 0.89 (0.80-1.00) | 0.89 (0.80-1.00) |

| Quintile 3 (15.6-18.8) | 2472/5059 | 55.5 (0.9) | 0.74 (0.67-0.82)* | 0.82 (0.74-0.92)* | 0.83 (0.75-0.93)* |

| Quintile 4 (18.8-23.2) | 2240/5018 | 51.6 (0.9) | 0.64 (0.58-0.70)* | 0.83 (0.75-0.93)* | 0.86 (0.77-0.95)* |

| Quintile 5 (> 23.2) | 1815/4974 | 43.8 (1.0) | 0.47 (0.42-0.52)* | 0.70 (0.63-0.78)* | 0.75 (0.67-0.84)* |

| P for trend | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | |

| Men | 55.7 (0.6) | ||||

| Quintile 1 (<13.8 ) | 1247/2198 | 63.8 (1.2) | reference | reference | reference |

| Quintile 2 (13.8-17.0) | 1186/2191 | 60.3 (1.3) | 0.85 (0.74-0.97)* | 0.93 (0.80-1.00) | 0.90 (0.77-1.05) |

| Quintile 3 (17.0-20.2) | 1057/2187 | 55.6 (1.3) | 0.71 (0.61-0.81)* | 0.85 (0.73-0.99)* | 0.83 (0.71-0.97)* |

| Quintile 4 (20.2-24.8) | 977/2191 | 52.9 (1.4) | 0.63 (0.55-0.73)* | 0.88 (0.75-1.03) | 0.90 (0.76-1.06) |

| Quintile 5(>24.8) | 758/2169 | 42.2 (1.4) | 0.42 (0.36-0.49)* | 0.65 (0.55-0.76)* | 0.70 (0.59-0.82)* |

| P for trend | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | |

| Women | 54.3 (0.5) | ||||

| Quintile 1(<11.9) | 1647/2881 | 62.1 (1.1) | reference | reference | reference |

| Quintile 2 (11.9-14.7) | 1554/2889 | 59.3 (1.1) | 0.89 (0.79-1.01) | 0.93 (0.81-1.06) | 0.92 (0.80-1.06) |

| Quintile 3 (14.7-17.6) | 1399/2864 | 53.8 (1.1) | 0.72 (0.63-0.81)* | 0.82 (0.71-0.94)* | 0.83 (0.72-0.96)* |

| Quintile 4 (17.6-21.8) | 1285/2849 | 50.6 (1.2) | 0.64 (0.57-0.73)* | 0.83 (0.72-0.95)* | 0.87 (0.75-0.99)* |

| Quintile 5 (> 21.8) | 1037/2780 | 43.5 (1.3) | 0.48 (0.42-0.55)* | 0.74 (0.65-0.85)* | 0.79 (0.68-0.91)* |

| P for trend | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | 0.001 |

Prevalence was expressed as weighted estimates [%] (standard errors [%], 95% confidence intervals). Model 1: crude. Model 2: adjusted for sex and age. Model 3: adjusted for sex, age, height, education level, economic status, physical activity, and sun exposure time. *P<0.05

For high myopia, the adjusted odds decreased as 25(OH)D quintiles increased after adjustment (P for trend <0.001, Table 5). The OR for high myopia in the highest vitamin D quintile was 0.36 (95%CI; 0.27–0.48) compared with the lowest vitamin D quintile. After adjustment of covariates, ORs for high myopia increased to 0.63 (95%CI; 0.47–0.85). Stratified analysis by gender demonstrated that adjusted OR for myopia in highest versus lowest quintile was 0.62 (95% CI; 0.39–0.98) in men and 0.81 (95% CI; 0.57–1.14) in women.

Table 5.

Association between blood 25-hydroxyvitamin D and prevalence of high myopia among Korean adults

| Vitamin D quintiles (ng/mL) | Case/total number | Prevalence | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Both gender | 4.7 (0.2) | ||||

| Quintile 1 (<12.6) | 283/5074 | 6.4 (0.4) | reference | reference | reference |

| Quintile 2 (12.6-15.6) | 241/5074 | 5.3 (0.4) | 0.81 (0.66-0.99)* | 0.88 (0.72-1.00) | 0.90 (0.73-1.10) |

| Quintile 3 (15.6-18.8) | 212/5059 | 4.6 (0.4) | 0.70 (0.57-0.88)* | 0.83 (0.67-1.04) | 0.86 (0.68-1.07) |

| Quintile 4 (18.8-23.2) | 175/5018 | 4.0 (0.4) | 0.60 (0.48-0.76)* | 0.83 (0.65-1.06) | 0.86 (0.67-1.10) |

| Quintile 5 (>23.2) | 110/4974 | 2.5 (0.3) | 0.36 (0.27-0.48)* | 0.58 (0.43-0.78)* | 0.63 (0.47-0.85)* |

| P for trend | <.001 | <.001 | 0.001 | 0.007 | |

| Men | 4.2 (0.2) | ||||

| Quintile 1 (<13.8 ) | 107/2198 | 5.7 (0.6) | reference | reference | reference |

| Quintile 2 (13.8-17.0) | 102/2191 | 5.1 (0.6) | 0.88 (0.63-1.23) | 0.96 (0.69-1.35) | 0.97 (0.68-1.37) |

| Quintile 3 (17.0-20.2) | 76/2187 | 4.1 (0.5) | 0.69 (0.49-0.98)* | 0.82 (0.58-1.17) | 0.82 (0.57-1.17) |

| Quintile 4 (20.2-24.8) | 64/2191 | 3.0 (0.4) | 0.49 (0.34-0.71)* | 0.66 (0.45-0.95) * | 0.68 (0.47-0.99)* |

| Quintile 5 (>24.8) | 38/2169 | 2.3 (0.5) | 0.38 (0.24-0.59)* | 0.57 (0.35-0.90)* | 0.62 (0.39-0.98)* |

| P for trend | <.001 | <.001 | 0.003 | 0.010 | |

| Women | 5.2 (0.3) | ||||

| Quintile 1 (<11.9) | 168/2881 | 6.6 (0.6) | reference | reference | reference |

| Quintile 2 (11.9-14.7) | 137/2889 | 5.0 (0.5) | 0.74 (0.57-0.97)* | 0.78 (0.60-1.03) | 0.78 (0.59-1.03) |

| Quintile 3 (14.7-17.6) | 130/2864 | 5.4 (0.6) | 0.79 (0.59-1.04) | 0.93 (0.70-1.23) | 0.96 (0.71-1.28) |

| Quintile 4 (17.6-21.8) | 118/2849 | 4.9 (0.5) | 0.70 (0.52-0.93)* | 0.93 (0.69-1.25) | 0.96 (0.71-1.30) |

| Quintile 5 (>21.8) | 81/2780 | 3.4 (0.5) | 0.48 (0.34-0.66)* | 0.75 (0.53-1.05) | 0.81 (0.57-1.14) |

| P for trend | 0.001 | <.001 | 0.350 | 0.634 |

Prevalence was expressed as weighted estimates [%] (standard errors [%], 95% confidence intervals). Model 1: crude. Model 2: adjusted for sex and age. Model 3: adjusted for sex, age, height, education level, economic status, physical activity, and sun exposure time. *P<0.05

Discussion

Our study demonstrated that the adjusted risk of myopia and high myopia decreased significantly as the increase of serum 25(OH) D levels in adults.

After adjusting for potentially confounding factors, subjects in the highest serum 25(OH) D quintile had a 19.1% lower risk of myopia compared with those in the lowest quintile. Our finding is supported by previous research of the Western Australian Pregnancy Cohort Study, in which the prevalence of myopia is significantly higher in individuals with vitamin D deficiency compared with those with sufficient levels.[35] Several studies have examined this association in adolescents or young adults. A case-control study of 22 adolescents reported that adolescents with myopic eyes had lower serum vitamin D levels than those with nonmyopic eyes.[36] Another study of 946 subjects aged 20 years and a study of 2,038 Korean adolescents reported that myopic participants had lower vitamin D levels.[27,35] However, longitudinal studies using prospectively collected data from an ongoing birth cohort study failed to discover an association between vitamin D levels and later myopia.[37,38] More recently, an epidemiologic study of 2,666 children aged 6 years demonstrated that lower vitamin D levels were associated with longer axial length and a higher risk of myopia.[39]

Although serum vitamin D level reflects sunlight exposure, which affects the prevalence of myopia in children through inhibition of eye growth, this effect may not be applied to adults, because eyeball growth is usually occurring in children or adolescents when the body grows. However, pathologic myopia showed that the axial length continues to increase with increasing age in adults period.[40,41] One possible explanation for this result is that polymorphisms within the vitamin D receptor are associated with myopia. A single nucleotide polymorphism, rs 1635529 on chromosome 12 region q13.11, which is in the vicinity of the gene encoding the vitamin D receptor, demonstrated significant over transmission in subjects in myopia.[42] In addition, proteomic and genetic associations were found between the vitamin D receptor and high myopia in previous studies.[43,44] Another explanation is due to the parallel effect of spending time outdoors in slowing the development of myopia and promoting vitamin D synthesis. The questionnaire assessment of sunlight-exposure variable in the present study was the binary variable containing only two levels, implicating that this variable was not well-quantified. Thus, we cannot assure that vitamin D has a causal role in relation to myopia. In addition, the reduction of the association after the inclusion of sunlight-exposure variable may suggest that the two variables may be, at least to some extent, covariates. The most plausible explanation is that children who are more active outside during childhood thus less likely to be myopic and are likely to have a tendency to spend more time outdoors later in life. This trend is probably reinforced by the fact that the children who become more myopic are those with better education and are thus more likely to have indoor jobs. However, the present study does not solve the causality issue, in which vitamin D might have a causal role for prevention of myopia.

We compared the results of the present study with those of previous studies for other ocular diseases from our previous reports based on same KNHANES data [Table 6].[23,24,25,26] In males, the OR of age-related macular degeneration, diabetic retinopathy, cataract, and dry eye syndrome were 0.32 (95% CI, 0.12–0.81), 0.37 (95% CI, 0.18–0.76), 0.76 (95% CI, 0.59–0.99), and 0.70 (95% CI, 0.30–1.64), respectively. The present study showed that OR for myopia was 0.70 (95% CI, 0.59–0.82). Interestingly, age-related macular degeneration and diabetic retinopathy whose pathology is located in posterior part of eyeball had relative lower OR, while cataract and dry eye syndrome whose pathologic location is in anterior eye showed relative higher OR. Main pathologic lesions of myopia occur in the sclera and are widely located from the anterior to the posterior part of the eyeball. We reasoned that association between vitamin D and myopia was more consistent than that between vitamin D and other ocular diseases by three findings. First, the 95% confidence interval of myopia was narrower than those of the other ocular diseases. Second, the association between vitamin D and myopia was found in both sexes, whereas the association between vitamin D and other ocular diseases was observed only in male. Finally, ORs of myopia were significantly decreased in those in the third, fourth, and fifth vitamin D quintiles. However, ORs of other ocular diseases were significantly decreased in only those in the fifth vitamin D quintile.

Table 6.

Comparison of strength in the association between serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D and various ocular pathologies in Korean adults

| Adjusted odds ratio of disease (highest versus lowest quintile) | Both gender | Men | Women |

|---|---|---|---|

| Diabetic retinopathy | 0.66 (0.38-1.13) | 0.37 (0.18-0.76)* | 1.58 (0.78-3.20) |

| Late age-related macular degeneration | 0.75 (0.33-1.58) | 0.32 (0.12-0.81)* | 1.90 (0.66-5.44) |

| Cataract | 0.86 (0.71-1.04) | 0.76 (0.59-0.99)* | 0.84 (0.66-1.07) |

| Dry eye syndrome | 0.85 (0.55-1.30) | 0.70 (0.30-1.64) | 0.92 (0.55-1.54) |

| Myopia | 0.75 (0.67-0.84)* | 0.70 (0.59-0.82)* | 0.79 (0.68-0.91)* |

*P<0.05

The differential effects of vitamin D may be due to different blood supply status at different location of the lesion. For example, blood supply in the macular and retina would be greater than in the lens and cornea. Thus, serum vitamin D affects less lens and cornea becomes small because of poor blood supply. The sclera is more vascularized than the retina, macula, lens, and cornea. This might be one of the reasons why vitamin D had a more consistent association with myopia in both men and women than the other ocular diseases evaluated by us.

The effect of vitamin D on myopia may differ in different parts of the world because vitamin D levels differ according to the latitude of the geography of study population.[45] Exposure to ultraviolet rays declines from the equator to the polar region, creating a gradient of vitamin D production in the skin. The latitude of South Korea is from 33 to 37 ° of the north. The main strengths of the present study are to enroll 25,199 participants and nationwide study design. Our study had some limitations. First, refractive error was evaluated without cycloplegia. It may cause the problem to overestimate myopia. However, main problem of measurement without cycloplegia may attenuate the probability of finding an association. Second, the current study design is a cross-sectional study, which made difficulties in reasoning causality. Third, seasonal variations of vitamin D levels were not considered, because KNHANES does not support information about sampling season. Fourth, although serum Vitamin D was inversely associated with myopia, the prevalence was still at 43.8% in the lowest quintile. This suggests that there are other significant factors that we did not deal with, in our study. Finally, some covariates such as outdoor activity or near work were not incorporated in this analysis, because these variables were not available in KNAHNES.

Conclusion

In conclusion, our study presented evidence of an association between serum 25(OH) D level and myopia in adults. We found a significant inverse association between serum 25(OH) D level and myopia in both men and women drawn from the general Korean population. However, our study has limitation of evidence on vitamin D as a causal agent given that the adjustment of time spent outdoors is insufficient, and study design is cross-sectional. Further study on therapeutic potential of vitamin D is needed such as randomized clinical trials.

Financial support and sponsorship

This study was supported by a grant from the National Research Foundation of Korea Grant funded by the Korean government (MSIP) (No. NRF 2016R1D1A1B03932606). The funders had no role in study design, data collection, and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Morgan IG, Ohno-Matsui K, Saw SM. Myopia. Lancet. 2012;379:1739–48. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60272-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lim MC, Gazzard G, Sim EL, Tong L, Saw SM. Direct costs of myopia in Singapore. Eye (Lond) 2009;23:1086–9. doi: 10.1038/eye.2008.225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Saw SM, Katz J, Schein OD, Chew SJ, Chan TK. Epidemiology of myopia. Epidemiol Rev. 1996;18:175–87. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.epirev.a017924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Choo V. A look at slowing progression of myopia. Lancet. 2003;361:1622–3. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)13315-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zheng YF, Pan CW, Chay J, Wong TY, Finkelstein E, Saw SM. The economic cost of myopia in adults aged over 40 years in Singapore. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2013;54:7532–7. doi: 10.1167/iovs.13-12795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Morgan IG, Rose KA. Myopia and international educational performance. Ophthalmic Physiol Opt. 2013;33:329–38. doi: 10.1111/opo.12040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pan CW, Ramamurthy D, Saw SM. Worldwide prevalence and risk factors for myopia. Ophthalmic Physiol Opt. 2012;32:3–16. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-1313.2011.00884.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rose KA, Morgan IG, Smith W, Burlutsky G, Mitchell P, Saw SM. Myopia, lifestyle, and schooling in students of Chinese ethnicity in Singapore and Sydney. Arch Ophthalmol. 2008;126:527–30. doi: 10.1001/archopht.126.4.527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rose KA, Morgan IG, Ip J, Kifley A, Huynh S, Smith W, et al. Outdoor activity reduces the prevalence of myopia in children. Ophthalmology. 2008;115:1279–85. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2007.12.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Guggenheim JA, Northstone K, McMahon G, Ness AR, Deere K, Mattocks C, et al. Time outdoors and physical activity as predictors of incident myopia in childhood: A prospective cohort study. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2012;53:2856–65. doi: 10.1167/iovs.11-9091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jones LA, Sinnott LT, Mutti DO, Mitchell GL, Moeschberger ML, Zadnik K. Parental history of myopia, sports and outdoor activities, and future myopia. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2007;48:3524–32. doi: 10.1167/iovs.06-1118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jones-Jordan LA, Mitchell GL, Cotter SA, Kleinstein RN, Manny RE, Mutti DO, et al. Visual activity before and after the onset of juvenile myopia. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2011;52:1841–50. doi: 10.1167/iovs.09-4997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wu PC, Tsai CL, Wu HL, Yang YH, Kuo HK. Outdoor activity during class recess reduces myopia onset and progression in school children. Ophthalmology. 2013;120:1080–5. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2012.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Feldkaemper M, Schaeffel F. An updated view on the role of dopamine in myopia. Exp Eye Res. 2013;114:106–19. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2013.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stone RA, Lin T, Iuvone PM, Laties AM. Postnatal control of ocular growth: Dopaminergic mechanisms. Ciba Found Symp. 1990;155:45–57. doi: 10.1002/9780470514023.ch4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McCarthy C, Megaw P, Devadas M, Morgan I. Dopaminergic agents affect the ability of brief periods of normal vision to prevent form-deprivation myopia. Exp Eye Res. 2007;84:100–7. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2006.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gao Q, Liu Q, Ma P, Zhong X, Ge J. Effects of directly intravitreal dopamine injections on development of lid-suture induced myopia in rabbits. Invest Ophtalmol Vis Sci. 2005;46:1987. doi: 10.1007/s00417-006-0254-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Alvarez JA, Chowdhury R, Jones DP, Martin GS, Brigham KL, Binongo JN, et al. Vitamin D status is independently associated with plasma glutathione and cysteine thiol/disulfide redox status in adults. Clin Endocrinol. 2014;81:458–66. doi: 10.1111/cen.12449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Uberti F, Lattuada D, Morsanuto V, Nava U, Bolis G, Vacca G, et al. Vitamin D protects human endothelial cells from oxidative stress through the autophagic and survival pathways. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2014;99:1367–74. doi: 10.1210/jc.2013-2103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mangge H, Weghuber D, Prassl R, Haara A, Schnedl W, Postolache TT, et al. The role of vitamin D in atherosclerosis inflammation revisited: More a bystander than a player? Curr Vasc Pharmacol. 2013;13:392–8. doi: 10.2174/1570161111666131209125454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Grant W, Strange R, Garland C. Sunshine is good medicine. The health benefits of ultraviolet-B induced vitamin D production. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2003;2:86–98. doi: 10.1111/j.1473-2130.2004.00041.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Reins RY, McDermott AM. Vitamin D: Implications for ocular disease and therapeutic potential. Exp Eye Res. 2015;134:101–10. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2015.02.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kim EC, Han K, Jee D. Inverse relationship between high blood 25-hydroxyvitamin D and late stage of age-related macular degeneration in a representative Korean population. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2014;55:4823–31. doi: 10.1167/iovs.14-14763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jee D, Han K, Kim EC. Inverse association between high blood 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels and diabetic retinopathy in a representative Korean population. PLoS One. 2014;9:e115199. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0115199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jee D, Kim EC. Association between serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels and age-related cataracts. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2015;41:1705–15. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrs.2014.12.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jee D, Kang S, Yuan C, Cho E, Arroyo JG. Serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels and dry eye syndrome: Differential effects of vitamin D on ocular diseases. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0149294. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0149294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Choi JA, Han K, Park YM, La TY. Low serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D is associated with myopia in Korean adolescents. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2014;55:2041–7. doi: 10.1167/IOVS.13-12853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jung SK, Lee JH, Kakizaki H, Jee D. Prevalence of myopia and its association with body stature and educational level in 19-year-old male conscripts in Seoul, South Korea. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2012;53:5579–83. doi: 10.1167/iovs.12-10106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lee JH, Jee D, Kwon JW, Lee WK. Prevalence and risk factors for myopia in a rural Korean population. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2013;54:5466–71. doi: 10.1167/iovs.13-12478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kim EC, Morgan IG, Kakizaki H, Kang S, Jee D. Prevalence and risk factors for refractive errors: Korean national health and nutrition examination survey 2008-2011. PLoS One. 2013;8:e80361. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0080361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kim Y, Park S, Kim NS, Lee BK. Inappropriate survey design analysis of the Korean national health and nutrition examination survey may produce biased results. J Prev Med Public Health. 2013;46:96–104. doi: 10.3961/jpmph.2013.46.2.96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Park HA. The Korea national health and nutrition examination survey as a primary data source. Korean J Fam Med. 2013;34:79. doi: 10.4082/kjfm.2013.34.2.79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sempos CT, Vesper HW, Phinney KW, Thienpont LM, Coates PM. Vitamin D status as an international issue: National surveys and the problem of standardization. Scand J Clin Lab Invest Suppl. 2012;243:32–40. doi: 10.3109/00365513.2012.681935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jee D, Morgan IG, Kim EC. relationship between sleep duration and myopia. Acta Ophthalmol. 2016;94:e204–10. doi: 10.1111/aos.12776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yazar S, Hewitt AW, Black LJ, McKnight CM, Mountain JA, Sherwin JC, et al. Myopia is associated with lower vitamin D status in young adults. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2014;55:4552–9. doi: 10.1167/iovs.14-14589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mutti DO, Marks AR. Blood levels of vitamin D in teens and young adults with myopia. Optom Vis Sci. 2011;88:377–82. doi: 10.1097/OPX.0b013e31820b0385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Guggenheim JA, Williams C, Northstone K, Howe LD, Tilling K, St Pourcain B, et al. Does vitamin D mediate the protective effects of time outdoors on myopia? Findings from a prospective birth cohort. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2014;55:8550–8. doi: 10.1167/iovs.14-15839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Morgan IG, Rose KA. ALSPAC study does not support a role for vitamin D in the prevention of myopia. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2014;55:8559. doi: 10.1167/iovs.14-15998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tideman JW, Polling JR, Voortman T, Jaddoe VW, Uitterlinden AG, Hofman A, et al. Low serum vitamin D is associated with axial length and risk of myopia in young children. Eur J Epidemiol. 2016;31:491–9. doi: 10.1007/s10654-016-0128-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Saka N, Moriyama M, Shimada N, Nagaoka N, Fukuda K, Hayashi K, et al. Changes of axial length measured by IOL master during 2 years in eyes of adults with pathologic myopia. Graefes Arch Clin Experim Ophthalmol. 2013;251:495–9. doi: 10.1007/s00417-012-2066-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Saka N, Ohno-Matsui K, Shimada N, Sueyoshi S, Nagaoka N, Hayashi W, et al. Long-term changes in axial length in adult eyes with pathologic myopia. Am J Ophthalmol. 2010;150:562–8e1. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2010.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mutti DO, Cooper ME, Dragan E, Jones-Jordan LA, Bailey MD, Marazita ML, et al. Vitamin D receptor (VDR) and group-specific component (GC, vitamin D-binding protein) polymorphisms in myopia. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2011;52:3818–24. doi: 10.1167/iovs.10-6534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Duan X, Lu Q, Xue P, Zhang H, Dong Z, Yang F, et al. Proteomic analysis of aqueous humor from patients with myopia. Mol Vis. 2008;14:370–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Annamaneni S, Bindu CH, Reddy KP, Vishnupriya S. Association of vitamin D receptor gene start codon (Fok1) polymorphism with high myopia. Oman J Ophthalmol. 2011;4:57–62. doi: 10.4103/0974-620X.83654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hagenau T, Vest R, Gissel T, Poulsen C, Erlandsen M, Mosekilde L, et al. Global vitamin D levels in relation to age, gender, skin pigmentation and latitude: An ecologic meta-regression analysis. Osteoporos Int. 2009;20:133–40. doi: 10.1007/s00198-008-0626-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]