Abstract

Purpose:

To evaluate the efficacy of intrastromal voriconazole for the management of fungal keratitis not responding to conventional therapy.

Methods:

Patients having microbiologically proven fungal keratitis with poor response to 2 weeks of conventional topical therapy were included in the study. After obtaining informed consent, an intrastromal injection of voriconazole was administered around the ulcer. Response to treatment in the form reduction in the size of the ulcer and infiltration was recorded on regular follow-ups.

Results:

Out of a total of 20 patients, 14 responded to intrastromal treatment and resolved, whereas six patients progressed to perforation. Mean resolution time was 35.5 ± 9.2 days. The most common organism isolated was Fusarium in six patients while Aspergillus and Mucor were isolated in two each. The causative organism could not be isolated in eight patients. The size of the ulcer at presentation and height of hypopyon were found to be significant risk factors associated with treatment outcomes.

Conclusion:

Intrastromal voriconazole as an adjuvant therapy appeared to be effective in treatment of fungal keratomycosis not responding to conventional therapy, thus, reducing the need for therapeutic or tectonic keratoplasty.

Keywords: Fungal keratitis, intrastromal voriconazole, recalcitrant ulcer

Microbial keratitis is one of the leading causes of ocular morbidity. Mycotic infections are responsible for nearly half of the cases of culture-positive infections in developing countries.[1,2] The treatment of fungal keratitis is difficult due to several limitations of currently available topical medications like poor penetration, surface toxicity, and limited spectrum.[3] Surgical modalities like therapeutic keratoplasty are often required for deep-seated fungal keratitis that is not responding to conventional treatment. However, the success rate of keratoplasty is limited by factors like graft rejection, reinfection, and limited availability of donor corneas in developing countries.[4] Targeted drug delivery in the form of intrastromal injection of antifungal agents has been described previously by few workers.[5,6,7] In this study, we evaluate the structural outcome of intrastromal voriconazole in recalcitrant fungal keratitis not responding to topical therapy.

Methods

A prospective interventional study was conducted on patients presenting in cornea outpatient department at a tertiary eye care center in Pune. The study was conducted over a period of one year from June 2017 to May 2018. Patients with a microbiologically proven fungal corneal ulcer that did not respond to conventional therapy over a period of 2 weeks were included in the study. The study was approved by the institutional ethics committee. Patients were explained in detail regarding the procedure and informed consent was obtained from all willing subjects.

Patients with microbiologically proven fungal keratitis not responding to topical natamycin (5%) and topical voriconazole (1%) after 2 weeks of treatment were included in the study. Ulcers with perforation, limbal involvement, size more than 6 mm, ulcers associated with endophthalmitis, and one-eyed patients were excluded from the study. Patients included in the study were between 18 and 80 years of age.

A detailed history of all patients was recorded, including mode of injury, duration of symptoms, and previous treatment history. A thorough slit lamp biomicroscopy was performed with documentation of the size of ulcer and infiltrate and height of the hypopyon. The area of the ulcer was calculated from its maximum diameter and the dimension perpendicular to the maximum diameter. Corneal scrapings were taken using no. 15 blade under topical anesthesia using proparacaine hydrochloride 0.5%. and were sent for microbiological investigations, including potassium hydroxide (10%) wet mount preparation, Gram-stained smear, and cultures on blood agar (BA) and Sabouraud dextrose agar (SDA).[8] Once the diagnosis was confirmed, patients were started on 5% natamycin sulfate and 1% voriconazole eye drops, instilled every hourly for two weeks, along with oral ketoconazole 200mg twice a day. On every visit, patients underwent therapeutic debridement for better penetration of the topical drug. The response to therapy was noted on slit lamp examination. If there was no change in the size and area of the ulcer or infiltrates, it was defined as “not improved;” an increase in the area, size and depth of the ulcer or infiltrate by 20% or perforation was defined as “worsened”. The ulcer was defined as 'healing' if the area and size of the ulcer and the infiltrate reduced by more than 20% from that at presentation. If no response to this combined therapy was observed after 2 weeks, the patients received intrastromal injection of voriconazole (50 μg/0.1 mL) around the fungal infiltrate.

Method of Intrastromal Injection

Injection voriconazole (VOZOLE PF; Aurolab, India) is available as 1 mg white, lyophilized powder in a glass vial. The powder was reconstituted with 2 mL of distilled water to a concentration of 0.5 mg/mL (50 μg/0.1 mL). The reconstituted solution was loaded in a 1 ml tuberculin syringe with a 30-gauge needle. After administration of the topical anesthetic drops, the patient was shifted to the operating table. Under full aseptic conditions, the preloaded drug was administered under the operating microscope. With the bevel up, the needle was inserted obliquely from the uninvolved, clear area to reach the infiltrate at the midstromal level (the intended level for drug deposit) in each case. The drug was then injected, and the amount of hydration of the cornea was used as a guide to assess the area covered. On achieving the desired amount of hydration, the plunger was withdrawn slightly to ensure discontinuation of the capillary column, thus, preventing back-leakage of the drug. This was repeated all around the infiltration in a circumferential manner to barrage the lesion.

After the intrastromal injection, as a follow-up, all patients were continued on the previously mentioned topical antifungal regimen. The patients were examined for 3 days and the response to therapy was recorded on slit lamp examination and the need for repeat injection was assessed. Once the infiltrate showed signs of healing, the patients were reviewed after 1 week, then once every 2 weeks for 3 months or until the ulcer had healed completely. At each follow-up, the size of the infiltrate, height of the hypopyon, and occurrence of any complications were noted by a slit lamp bio-microscopy. The infection was considered resolved when there was complete healing of the epithelial defect with the resolution of corneal infiltrate and scar formation. The patients were continued on topical antifungal therapy for at least 2 weeks after the complete resolution of the infection. In case of worsening or no response to the previous injection within 3 to 7 days, the intrastromal injection of voriconazole was repeated. Patients with impending perforation underwent application of cyanoacrylate glue with bandage contact lens after one intrastromal injection of voriconazole along with continuation of the topical antifungal regimen as mentioned previously. Patients with perforations and those with progression of infiltrate size by more than 20%, despite three intrastromal voriconazole injections, were considered as treatment failure, and they were taken up for tectonic and therapeutic penetrating keratoplasty (TPK) respectively. The final outcome was assessed in terms of anatomical success, which included patients in whom the ulcer healed with scar formation and treatment failure, which included nonhealing ulcers with progressive infiltrate and perforation.

Results

The study included 20 subjects. There were fifteen males (75%) and five females (25%). The age of the patients ranged from 28 years to 85 years, mean age being 48.94 ± 15.87 years. All patients had anterior (anterior one third) to midstromal (anterior two thirds) involvement on slit lamp examination. Fifteen patients (75%) had a preceding history of vegetative trauma. On examination, the mean infiltrate size was 49.5 mm2 ± 15.63 with hypopyon present in nine patients (45%). The mean time interval between onset of symptoms and presentation to the hospital was 14.8 ± 16.46 days. In all cases, on 10% KOH mount and Gram's staining, a septate or nonseptate fungal hyphae were seen. However, in only 60% of the cases, causative fungi could be identified on culture. The fungus species isolated are mentioned in Table 1. The predominant pathogen isolated was Fusarium, found in six (30%) patients. Of the 20 enrolled patients, 14 resolved after intrastromal injections, whereas six patients did not respond to the treatment. The average number of injections given to the patients was 2.65 ± 1.56 over a period of 13.2 ± 9.79 days, with minimum of one to maximum of seven injections required. Overall 15 patients required more than one injection, with nine requiring more than two injections. All treatment failure cases proceeded to perforation despite injections and required emergency tectonic keratoplasty. Organisms isolated from patients that progressed were Fusarium and Mucor in two patients each while the remaining two patients had unidentified fungus. The average resolution time was 35.5 ± 9.22 days. The relation between various risk factors and outcome of treatment is shown in Table 2. Few examples of clinical resolution of fungal ulcer after intrastromal voriconazole therapy from our study are shown in Figs. 1 and 2. The size of the ulcer at presentation and height of hypopyon were found to be significant risk factors associated with treatment outcomes. The deep ulcers required a greater number of injections, whereas the superficial ones required lesser number of injections. No procedure-related complication or drug-related systemic or local adverse effects were noted.

Table 1.

Fungal species isolated

| Fungal species | Total number (n=20) |

|---|---|

| Fusarium | 6 (30%) |

| Aspergillus | 2 (10%) |

| Mucor | 2 (10%) |

| Other Fungus | 2 (10%) |

| Unidentified | 8 (40%) |

Table 2.

Comparison between healed and perforated ulcer

| Characteristics | Epithelial outcome | n | Mean | SD | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (Years) | Healed | 14 | 49.07 | 17.49 | 0.832 |

| Perforated | 6 | 50.50 | 11.52 | ||

| Size of ulcer (mm^2) | Healed | 14 | 8.46 | 4.94 | 0.04 |

| Perforated | 6 | 18.35 | 11.77 | ||

| Number of injections | Healed | 14 | 2.79 | 1.76 | 0.485 |

| Perforated | 6 | 2.33 | 1.03 | ||

| Duration of treatment (days) | Healed | 14 | 12.79 | 10.12 | 0.782 |

| Perforated | 6 | 14.17 | 9.85 | ||

| Interval of presenting and injection (days) | Healed | 14 | 12.86 | 13.84 | 0.521 |

| Perforated | 6 | 19.50 | 22.25 | ||

| Size of hypopyon | Healed | 5 | 1.2 | 0.67 | 0.039 |

| Perforated | 4 | 3.12 | 1.03 |

P<0.05 was considered as significant. SD=Standard deviation

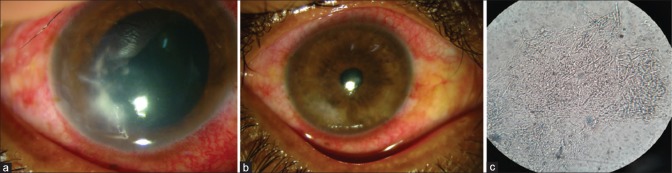

Figure 1.

Patient with non resolving corneal ulcer: (a) stromal infiltration before intrastromal injection; (b) complete resolution after intrastromal voriconazole; (c) KOH mount of the patient in (a) showing filamentous fungi

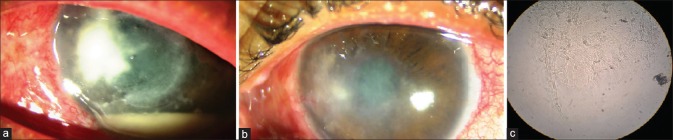

Figure 2.

Patient with long standing recalcitrant fungal ulcer: (a) large ulcer with infiltration and hypopyon; (b) resolution of ulcer and hypopyon after intrastromal voriconazole therapy; (c) fungal filaments seen on KOH mount

Discussion

Management of deep fungal keratitis is difficult because of factors like poor penetration, surface toxicity, and limited spectrum of topical antifungal agents.[3] Recently, modalities aimed at targeted drug delivery are being explored to overcome the problem of poor drug penetration. Injections of antifungal drugs via intrastromal route have been tried to attain optimal intracorneal concentrations.[5] Previously, intrastromal amphotericin b has been used to treat recalcitrant fungal ulcers.[9] However, several complications have been reported with amphotericin b like surface toxicity, retinal toxicity, and others. Newer agents like voriconazole have shown to have a better outcome due to lower mean inhibitory concentration (MIC) against filamentous fungi and better penetration.[3,10] Also, the systemic side effects are less in comparison to amphotericin b. Recent studies have advocated the use of intrastromal voriconazole for nonhealing mycotic infections.[11,12] In this study, the subjects who did not respond, even after 2 weeks of conventional topical antifungal therapy, were planned for an intrastromal injection. The drug was injected along the circumference of the infiltration, forming a barrage of drug deposits around the lesion. The concentration of the drug used was 50 mcg in 0.1 ml.

In our study, the mean time duration between the onset of symptoms and presentation to the hospital was 14.8 ± 16.46 days. This duration was similar to some of the studies done previously in the Indian scenario.[6] Various studies done in western and southern India have documented Fusarium as the most common fungal pathogen causing keratitis.[6,13] In our study also, Fusarium was the most common pathogen identified in 30% of the cases.

Previous case series have reported success with intrastromal voriconazole in recalcitrant deep mycosis. Prakash et al. demonstrated successful healing in all the three patients with deep nonhealing fungal ulcers.[5] Some other case series in the literature have similar findings.[14,15] Sharma N et al. did a prospective study on 12 eyes and reported a success rate of more than 80% (10/12).[7] Similarly, Kalaiselvi et al. reported a treatment success rate of 72% in Tamil Nadu, India. They found successful healing in 18 out of 25 eyes.[6] In this study, 14 out of the 20 patients responded to intrastromal treatment, giving a success rate of 70%. Although, we recommend randomized control trials (RCTs) with larger sample size for establishing benefit and success rate of the treatment.

A total of 15 patients (75%) required repeat injections. Ten of the 14 patients showing treatment success required reinjections. Need for reinjections for optimum resolution has been reported by previous studies.[6,7] Mean healing time of the patients in this study was 35.5 ± 9.22 days, which was comparable with other studies.[6,7] There was statistically a significant difference in the size of hypopyon between patients with successful treatment and treatment failures. The size of the ulcer at presentation significantly affected the treatment outcome. Larger ulcers were associated with increased risk of treatment failure. These findings were also observed in the study done by Kalaiselvi et al. in South India.[6] Other factors like the time interval of presentation and number of injections had no effect on the outcome [Table 2]. However, patients who presented early required lesser number of injections and healed earlier than those presenting later. Also, patients with smaller size of infiltrate required lesser number of injections, although a statistical correlation could not be found due to small sample size. Causative organisms might have an impact on the final outcome although discussion on that aspect would be out of scope of this study. In our series, six out of 20 (30%) of the patients progressed and developed perforation despite the therapy although none of them were due to intraoperative inadvertent corneal perforation. This is a relatively higher percentage of intervention failure. The exact reasons are difficult to ascertain and may be attributed to factors like deeper stromal involvement or large ulcers with more horizontal extent of infiltrate at presentation. Although no procedure-related complications were noted in our series, complications due to toxicity of voriconazole with possible endothelial damage, creation of new infective foci, and microperforations during injection should be borne in mind while using this modality of treatment.

Although intrastromal voriconazole has shown promising effects, the dosage and frequency of injections are yet to be determined. Large clinical trials with long-term follow-up might be required in determining the above factors.

Conclusion

Intrastromal voriconazole appears to be an effective treatment modality for recalcitrant deep fungal corneal ulcers. Hereby, we conclude that intrastromal voriconazole might be used as an adjuvant for nonhealing fungal ulcers in selected patients. It may help in reducing the risk of complications, such as corneal perforation, thus the need for therapeutic keratoplasty.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Singh DP, Verma RK, Singh A, Kumar S, Mishra V, Mishra A. A retrospective study of fungal corneal ulcer from the western part of Uttar Pradesh. Int J Res Med Sci. 2015;3:880–882. Available from: https://www.msjonline.org/index.php/ijrms/article/view/1399 . [Google Scholar]

- 2.Judy I. Ou NRA. Epidemiology and treatment of fungal corneal ulcers. Int Ophthalmol Clin. 2007;47:7–16. doi: 10.1097/IIO.0b013e318074e727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gubert Müller G, Kara-José N, Silvestre De Castro R. Antifungals in eye infections: Drugs and routes of administration. Rev Bras Oftalmol. 2013;72:132–41. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Panda A, Vajpayee RB, Kumar TS. Critical evaluation of therapeutic keratoplasty in cases of keratomycosis. Ann Ophthalmol. 1991;23:373–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Prakash G, Sharma N, Goel M, Titiyal JS, Vajpayee RB. Evaluation of intrastromal injection of voriconazole as a therapeutic adjunctive for the management of deep recalcitrant fungal keratitis. Am J Ophthalmol. 2008;146:56–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2008.02.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kalaiselvi G, Narayana S, Krishnan T, Sengupta S. Intrastromal voriconazole for deep recalcitrant fungal keratitis: A case series. Br J Ophthalmol. 2015;99:195–8. doi: 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2014-305412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sharma N, Agarwal P, Sinha R, Titiyal JS, Velpandian T, Vajpayee RB. Evaluation of intrastromal voriconazole injection in recalcitrant deep fungal keratitis: Case series. Br J Ophthalmol. 2011;95:1735–7. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2010.192815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sengupta S, Rajan S, Reddy PR, Thiruvengadakrishnan K, Ravindran RD, Lalitha P, et al. Comparative study on the incidence and outcomes of pigmented versus non pigmented keratomycosis. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2011;59:291–6. doi: 10.4103/0301-4738.81997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Garcia-Valenzuela E, Song CD. Intracorneal injection of amphothericin B for recurrent fungal keratitis and endophthalmitis. Arch Ophthalmol. 2005;123:1721–3. doi: 10.1001/archopht.123.12.1721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Clode AB, Davis JL, Salmon J, Michau TM, Gilger BC. Evaluation of concentration of voriconazole in aqueous humor after topical and oral administration in horses. Am J Vet Res. 2006;67:296–301. doi: 10.2460/ajvr.67.2.296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Neoh CF, Leung L, Vajpayee RB, Stewart K, Kong DC. Treatment of alternaria keratitis with intrastromal and topical caspofungin in combination with intrastromal, topical, and oral voriconazole. Ann Pharmacother. 2011;45:e24. doi: 10.1345/aph.1P586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sharma N, Chacko J, Velpandian T, Titiyal JS, Sinha R, Satpathy G, et al. Comparative evaluation of topical versus intrastromal voriconazole as an adjunct to natamycin in recalcitrant fungal keratitis. Ophthalmology. 2013;120:677–81. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2012.09.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kumar A, Pandya S, Kavathia G, Antala S, Madan M, Javdekar T. Microbial keratitis in Gujarat, Western India: Findings from 200 cases. Pan Afr Med J. 2011;10:48. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Siatiri H, Daneshgar F, Siatiri N, Khodabande A. The effects of intrastromal voriconazole injection and topical voriconazole in the treatment of recalcitrant Fusarium keratitis. Cornea. 2011;30:872–5. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0b013e3182100993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lekhanont K, Nonpassopon M, Nimvorapun N, Santanirand P. Treatment with intrastromal and intracameral voriconazole in 2 eyes with Lasiodiplodia theobromae keratitis: Case reports. Medicine (Baltimore) 2015;94:e541. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000000541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]