Abstract

Analysis of genomic data is often complicated by the presence of missing values, which may arise due to cost or other reasons. The prevailing approach of single imputation is generally invalid if the imputation model is misspecified. In this paper, we propose a robust score statistic based on imputed data for testing the association between a phenotype and a genomic variable with (partially) missing values. We fit a semiparametric regression model for the genomic variable against an arbitrary function of the linear predictor in the phenotype model and impute each missing value by its estimated posterior expectation. We show that the score statistic with such imputed values is asymptotically unbiased under general missing-data mechanisms, even when the imputation model is misspecified. We develop a spline-based method to estimate the semiparametric imputation model and derive the asymptotic distribution of the corresponding score statistic with a consistent variance estimator using sieve approximation theory and empirical process theory. The proposed test is computationally feasible regardless of the number of independent variables in the imputation model. We demonstrate the advantages of the proposed method over existing methods through extensive simulation studies and provide an application to a major cancer genomics study.

Keywords: Association tests, Imputation, Integrative analysis, Multiple genomics platforms, Semiparametric models, Sieve estimation

1. INTRODUCTION

Recent technological advances have made it possible to measure multiple genomics platforms on the same set of subjects. However, constraints regarding cost and other factors prohibit measurement of all platforms on all study subjects. For example, in The Cancer Genome Atalas (TCGA) (https://cancergenome.nih.gov/), over 10,000 subjects with 33 cancer types were measured on multiple genomics platforms, including somatic mutation, copy number variation, and expressions of microRNA, mRNA, and protein, but for a substantial number of subjects, data on RNA sequencing and protein expressions were not generated. As another example, in the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute’s Exome Sequencing Project (https://esp.gs.washington.edu/), only 7,000 subjects with specific diseases or conditions were selected for whole-exome sequencing from the tens of thousands of total subjects with genotyping array data (Lin et al. 2013). Finally, in the Trans-Omics for Precision Medicine (TOPMed) program (https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/researeh/resourees/nhlbi-precision-medicine-initiative/topmed) and the Genome Sequencing Program (GSP) (http://gsp-hg.org), whole-genome sequencing data will be available on hundreds of thousands of subjects, but other genomics platforms, such as RNA sequencing, methylation, and metabolites, will be available for only a few thousand subjects through ancillary studies of specific diseases.

It is desirable to infer missing data on one genomics platform using available data from other platforms. Indeed, this has become a routine practice with genotype data, where linkage disequilibrium allows one to impute, with great accuracy, sequencing data from genotyping array data (Li et al. 2010; Auer et al. 2012). A far greater challenge is to infer missing values for a quantitative measurement, such as the expression of RNA or protein, from other quantitative measurements or from SNP genotype data due to the complex and noisy relationships among those variables (Kim et al. 2005; Torres-García et al. 2009).

Several authors have considered missing data in the context of association testing, which is of primary interest in genomics studies. Specifically, Hu et al. (2015) studied the score test based on imputed genotype data and proposed a variance estimator that properly accounts for the differential quality between observed and imputed genotypes. The method requires that the imputation is unbiased and the genotype is independent of the other variables in the phenotype model. Derkach et al. (2015) and Lawless (2016) proposed to model the variable with missing values under outcome-dependent sampling and studied the score test based on the full likelihood. Derkach et al. (2015) assumed a nonparametric model for the variable with missing values and restricted covariates to only a few possible values. Lawless (2016) assumed a full parametric missing-data model. All existing methods require unbiased imputation or correct modeling of the variable with missing values. This is difficult to achieve, especially when the number of covariates in the missing-data model is not small.

In this paper, we investigate the validity of the score test with imputed data when the missing-data mechanism may depend on the phenotype and high-dimensional covariates. In particular, we show that a condition weaker than correct specification of the missing-data model is sufficient for the score statistic to be unbiased. Based on this finding, we propose a robust score test which, unlike existing methods, preserves the type I error under general missing-data mechanisms even when the imputation model is misspecified. The proposed score statistic is based on a semiparametric model for the variable with missing values, where covariates enter the model linearly and also through a one-dimensional nonparametric function. As a result, the test is feasible with a large number of covariates in the missing-data model. The proposed methodology is applicable to all common phenotype models and encompasses continuous, binary, and right-censored phenotypes.

In Section 2, we formulate the problem, investigate the validity of the standard score test under various missing-data mechanisms, and develop the robust score test. In Section 3, we report results from simulation studies that compare the proposed and existing methods. In Section 4, we provide an application to a dataset from TCGA. We make concluding remarks in Section 5 and relegate technical details to the Appendix.

2. METHODS

Consider a genomics study that involves phenotype Y, genomic variable of interest S, and vector of covariates X. For example, Y may represent disease status, S may represent the RNA expression of a gene, and X may include genomic variables associated with S, such as the mutation status and copy number of the gene, or non-genomic variables, such as tumor stage, age, and ancestry. Let f(·; βS + γTX, ζ) denote the density function of Y conditional on (S, X), where β and γ are regression parameters, and ζ is a set of nuisance parameters that may be infinite-dimensional; this is referred to as the phenotype model. In particular, ζ is the dispersion parameter in the generalized linear model and the baseline hazard function in the proportional hazards model. We allow S to be missing and let R indicate, by values of 1 versus 0, whether S is observed or not, respectively. Let Z be a set of predictors for S that includes X, as well as variables that are not present in the phenotype model. The extra variables in Z are exogenous variables that affect Y indirectly through S and X, such that Z is independent of Y conditional on X under β = 0. The observed data consist of (Yi, SiRi, Ri, Zi) for i = 1,…, n.

We are interested in testing the null hypothesis H0 : β = 0. Among the three common tests, namely the Wald’s test, the likelihood ratio test, and the score test, the first two require fitting the model under the alternative hypothesis, which involves estimation of the conditional distribution of S give X in the presence of missing values for S. If the model for S is misspecified (which is inevitable when the dimension of X is moderately high), then the estimators of the nuisance parameters may be inconsistent, such that the resulting tests are invalid. By contrast, the score test only requires fitting the model under the null hypothesis. As a result, the score test requires fewer assumptions on the missing-data model than the other two tests in order to yield correct type I error. Therefore, we focus on the score test in the rest of this paper.

The score statistic for β at β = 0 takes the form of A(Y, X; ψ)S, where A(Y, X; ψ) = ∂ log f(Y; t + γT X, ζ)/∂t∣t=0, and ψ = (γ, ζ). Note that E{A(Y, X; ψ0) | X} = 0, where ψ0 ≡ (γ0, ζ0) is the true value of ψ. This formulation includes many common models as special cases. For the linear model, A(Y, X; ψ) = σ−2(Y − γTX), where σ2 is the error variance. For the logistic model, A(Y, X; ψ) = Y − eγTX/(1 + Y − eγTX). For the proportional hazards model with right censoring, , where , , Δ = I(T ≤ C), T is the survival time of interest, C is the censoring time, I(·) is the indicator function, and ∧ is the cumulative baseline hazard function.

We consider the score statistic based on the imputed S. We specify an imputation model of S that depends on Z and a set of parameters ξ Let be the imputed value of Si, where is an estimator of ξ The (normalized) imputation “score” statistic is

where is an estimator of ψ under H0. At β = 0, the score statistic based on the full likelihood with a regression model of S on Z takes the form of . However, the proposed imputation score statistic is more general in that needs not be the posterior mean of S (given the observed data) evaluated at the maximum likelihood estimator of ξ Let ξ* be the limit of . The following proposition provides a general sufficient condition for the unbiasedness of the imputation score statistic under H0.

Proposition 1. Assume that there exists a projection of X, denoted by , such, that R is independent of(S, Z) conditional on (Y, ) and . Then, , under β = 0.

The proofs of this proposition and other technical results are provided in Appendix A.1.

Remark 1. The missing-data mechanism assumed in this proposition may arise from the extreme-tail sampling scheme, where only subjects with extreme values of Y are selected for measurements of S (Lin et al. 2013). In this case, the inverse probability weighting approach is not feasible because P(R = 1 | Y) is zero for some subjects, whereas the imputation approach is applicable.

Remark 2. The dependence of R on may be introduced by design, where the sampling of S is performed separately at different values of . In cancer genomics, may include risk factors such as tumor stage and tumor grade, and subjects with unusually high or unusually low risk may be more likely to be selected for measurements of S. In addition, may represent categories defined by (possibly continuous) demographic variables such as age. Although X may be high-dimensional and continuous, is typically a discrete, low-dimensional projection of X, such that nonparametric modeling of S on is feasible.

Remark 3. The condition in Proposition 1 requires that the true and imputed S variables have the same conditional expectation given and . This condition is trivially satisfied if S is independent of X and the imputed value has the same mean as S, as assumed by Hu et al. (2015). For the score statistic to be unbiased, we only need the expectation of the true and imputed S variables conditional on and a single index to be the same. This is practically achievable via nonparametric modeling of S given the low-dimensional covariates (), even though the whole set of covariates X may be high-dimensional. If the missing-data mechanism does not depend on covariates, then is absent, such that it is only necessary to correctly model the conditional expectation of S given the single index .

Proposition 1 implies that the imputation score statistic is unbiased under H0 if the conditional expectation of S given a specific projection of Z (but not necessarily the full set of Z) is correctly specified. To guarantee that this condition holds, we model the relationship between S and () nonparametrically when is discrete and takes a small number of values. Because the regression model of S on () may not be very predictive, we include other components of Z in the imputation model in order to improve the imputation accuracy. Given the nonparametric function of (), the inclusion of Z will not result in bias of the score statistic even if the imputation model is misspecificd. In the sequel, we assume that the missing-data mechanism specified in Proposition 1 holds and that is discrete with possible values (). For each (l = 1,…, L), we assume the working model , where gl is unspecified, and is a specific q-dimensional function of Z that is (asymptotically) orthogonal to (), Let ( almost surely, ξ = (g1,…, gL, η1,…, ηL), and . The following proposition states the unbiasedness of the resulting imputation score statistic.

Proposition 2. If , then

Proposition 2 motivates us to estimate gl and ηl using least-squares regression with the complete observations. We propose to approximate gl (l = 1,…, L) with B-spline functions of order m (De Boor 1978) and replace the true value γ0 by the estimator . For simplicity of presentation, we assume the same set of fixed B-spline functions for each gl, but we allow them to be chosen adaptively and separately for each gl in practice. Let m and Kn be integers, such that Kn ≥ m ≥ 2, and Kn depends on the sample size n. For a set of grid points τ ≡ (τ0,…, τKn−m+1), such that , let B (·) = (B1(·),…, BKn (·))T, where Bk is the kth m-order B-spline function on τ; the grid points at the two ends have multiplicity m. For l = 1,…, L, let

where αl = (αl1,…, αlKn)T. Effectively, we partition the data into L strata, with each stratum corresponding to a value of , and we perform separate least-squares regression for each stratum using subjects with observed S. Let , . The robust imputation score statistic is , where

and the third argument in corresponds to γ in the argument of gl.

Let ℓβ(ψ, ξ; γ) be for a single subject, ℓψ(ψ)[h1] be the derivative of log f (Y; γTX, ζ) along the path ψ = ψ0 + ϵh1, with h1 being a tangent vector for ψ, ℓβψ(ψ, ξ; γ)[h1] be the derivative of ℓβ(ψ; ξ; γ) along the same path, ℓψψ(ψ)[h1, h2] be the derivative of ℓψ(ψ)[h1] along the path ψ = ψ* + ϵh2, with h2 being a tangent vector for ψ, and ℓξ(ξ)[h3] be the derivative of along the path and ξ = ξ* + ϵh3, with h3being a tangent vector for ξ Let and P denote the empirical and true probability measures, respectively. We impose the following conditions.

(C1) For l = 1,…, L, and are unique, and has bounded fourth derivative.

(C2) The support of Z is bounded, and has a bounded continuous support. Conditional on Z, S has finite second moment.

(C3) The number of knots of the B-spline functions is such that and as n → ∞.

(C4) At β = 0, for a suitable norm, and the estimator satisfies

where is the efficient score function of γ, such that , and is non-zero and finite.

(C5) The functions , , , and are Donsker for (ψ, ξ) belonging to a neighborhood of (ψ0, ξ*) and (h1, h2) belonging to a bounded subset of a suitable metric space. In addition, the information operator for the phenotype model Plψψ(ψ0)[·, ·] is invertible under the null hypothesis H0.

Remark 4. Conditions (C1) and (C2) pertain to regularity conditions on the variable with missing values and covariates. For and to be unique, we require that and cannot be expressed as functions of linear terms of . In practice, we let be a linear combination of the components of Z not present in , such that , Condition (C3) pertains to the rate at which the number of knots of the B-spline functions increases to infinity; particularly, the condition is satisfied with Kn = O(n1/13). Conditions (C4) and (C5) are regularity conditions on the phenotype model, which are satisfied for common models, such as generalized linear models and proportional hazards models. For parametric models and the Cox proportional hazards model, the norm in condition (C4) is the Euclidean norm and the ℓ∞[0, t*]-norm, respectively, where t* is the end of the study, and the metric space for (h1, h2) in condition (C5) is the Euclidean space and the space of functions of bounded variation, respectively.

The asymptotic distribution of the robust imputation score statistic is given in the following theorem.

Theorem 1. Under conditions (C1)–(C5) and β = 0 is asymptotically zero-mean normal with variance

where hψ solves Pℓβψ(ψ0, ξ*; γ0)[·] = Pℓψψ(ψ0)[hψ, ·], hξ = (hg,1 …, hg,L, hη,1, …, hη,L), such that hη,l = 0 and

for l = 1, …, L,

and f′ denotes the first derivative of f for any function f.

Remark 5. The second and third terms in V are projections of the score funetion of (ψ, ξ), and hψ is the least-favorable direction of ψ for the phenotype model if the imputation model is assumed to be known. The fourth term in V is present because , instead of the true value, is used in the imputation model. The estimator affects the imputation both by directly entering the imputation function and by involving in the estimation of .

Motivated by Theorem 1, we propose an empirical variance estimator of the score statistic

where (ℓβ,i, ℓψ,i, ψξ,i) is (ℓβ, ℓψ, ℓξ) evaluated at the observations of the ith subject, M is the sample mean of the first term in and () is the empirical version of (hψ, hξ, Iγ, ) evaluated at (). Specifically, is obtained by performing the usual linear expansion of at ξ*, with the imputation model treated as a linear model with covariates . The explicit form of is given in the proof of Theorem 2 in Appendix A.1. We formulate the variance estimator under the linear model, the logistic model, and the Cox proportional hazards model in Appendix A.2. The resulting score test statistic is . The validity of the robust score test is stated below.

Theorem 2. Under conditions (C1)–(C5) and β = 0, the empirical variance estimator converges almost surely to the true variance V, and the test statistic converges in distribution to the chi-square distribution with one degree of freedom.

Remark 6. The empirical variance estimator is consistent regardless of the missing-data mechanism and the imputation model. By contrast, the standard model-based variance estimator with imputed data is generally biased if the missing-data mechanism depends on the phenotype. The bias of the standard variance estimator under generalized linear models is derived in Appendix A.3.

When the missing-data mechanism does not depend on the phenotype, the score statistic is unbiased under any imputation schemes; this result follows from the proof of Proposition 1. In this case, the proposed test is not required for bias correction, and one may wonder whether the inclusion of the B-spline terms and the stratification may lead to power loss. The comparison of power between the proposed test and the standard score test under general settings is difficult, because the power generally depends on the missing-data mechanism and high moments of S; the derivation for the power of the proposed test is given in Appendix A.4. When Y is normally distributed and S is missing completely at random, the asymptotic power of the proposed test is higher than or equal to that of the standard score test, because the imputation model with the B-spline terms, stratification, and linear predictors may have a better fit than the model with the linear predictors alone.

3. SIMULATION STUDIES

Let X = (X1, X2, X3)T, where X1, X2, and X3 are independent standard normal, Bernoulli(0.5), and Binomial(2, 0.25), respectively. Let G be a vector of other covariates that are used to predict S. In particular, G = (G1,…, G4), where Gj (j = 1,…, 4) is independent Binomial(2, 0.3). In cancer genomics, X1, X2, and X3 may represent (standardized) age, gender, and tumor stage, respectively, and G may represent genotypes at four loci. We generated the phenotype Y using the linear predictor r(S, X) = γ0+γTX + βS under the linear, logistic, and proportional hazards models. For all models, we set γ = (1, −1, 0.5)T. For the linear model, we generated Y ~ N{r(S, X), 1} with γ0 = 0. For the logistic model, we set logit−1 {P(Y = 1 ∣ S, X)} = r(S, X), where γ0 was chosen such that P(Y = 1) ≈ 0.15. For the proportional hazards model, we generated Y with the hazard function λ(t | S, X) = 0.5ter(S, X) and γ0 = 0. The censoring variable was generated independently from Unif(0, τ), where τ was chosen such that the censoring proportion was about 40%. We considered two models for S: with Model 1, S = X1+X2+0.3X3+0.4(G1 − G2 + G3 − G4)+N(0,1); and with Model 2, S = (X1 + X2) + 0.1(X1 + X2)2 + 0.3 I(X3 = 2) + 0.4(G1 − G2 + G3 − G4) + N(0,1).

We considered three missing-data mechanisms. Mechanism 1 is missing completely at random, where the missing-data status is independent of other variables. For Mechanism 2, the missing-data status was generated separately for two subsets of subjects: one subset consisted of all subjects with X2 = 1, and a random sample of subjects from the subset were selected for observation of S; the other subset consisted of all subjects with X2 = 0, and subjects from the subset were selected for observation of S based on the phenotype. For the continuous and survival phenotypes, an equal number of subjects at the two extreme tails of the phenotype distribution were selected. For the binary phenotype, all subjects with Y = 1 were selected, and a fraction of subjects with Y = 0 were selected to attain the desired missing proportion. The missing proportion was set to be the same between the two subsets of subjects. This setting mimics a study where two datasets with different sampling schemes are combined. For Mechanism 3, four strata were defined with denoting the stratum number, where is the zα is the α-quantile of the standard normal distribution. Subjects were selected for observation of S separately for each stratum using the sampling scheme adopted for the second subset of subjects in Mechanism 2. The missing proportion was set to be the same across strata. This setting was designed to evaluate the sensitivity of the proposed test to misspecification of .

We compared the performance of six tests: (1) the standard score test using complete data only; (2) the standard score test with missing values imputed under a linear model of S on Z = (XT, GT)T; (3) Lawless (2016)’s score test based on the same model of S as (2); (4) Hu et al. (2015)’s score test with the imputed data of (2); (5) the proposed score test with being that specified in Remark 4 and with stratification variable = for Mechanisms 1 and 2 or for Mechanism 3; and (6) the imputation score test with missing data imputed using a linear model of S on Z = (XT, , X1X2, I(X3 = 2), GT)T and the empirical variance estimator. We refer to methods (1)–(6) as the complete-case analysis, the simple imputation method, Lawless’ method, Hu’s method, the proposed imputation method, and the full-model imputation method, respectively. The last method is the gold standard but is not practical because it requires correct specification of a complex missing-data model. Derkach et al. (2015)’s method was not included because it requires the covariates in the imputation model to be discrete and is identical to Lawless (2016)’s method when a linear imputation model is assumed. Note that the missing-data models used by all the methods are correct under Model 1, but only the missing-data model used by the full-model imputation method is correct under Model 2. For the proposed imputation method, we chose the degree and number of knots of the B-spline functions using five-fold cross-validation separately for each stratum. For the lth stratum, the grid point τk (k = 1,…, Kn − m − 2) was set to be the empirical k/(Kn − m +1)-quantile of among subjects with Ri = 1 and , , and . Lawless’ and Hu’s methods are not applicable to the survival phenotype.

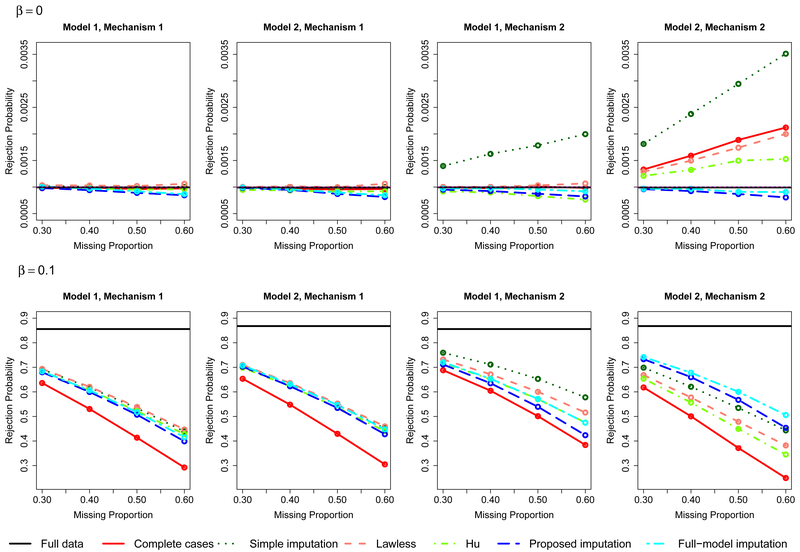

We considered a sample size of 1,500 and missing proportions ranging from 30% to 60%, For each setting, we simulated 1,000,000 and 100,000 replicates for β = 0 and β ≠ 0 respectively. The nominal significance level was set to 10−3. We plot the rejection probability against the missing proportion for the two models of S and the three missing-data mechanisms. For reference, the rejection probability of the score test based on the full data (i.e,, no missing values) is also shown. For Mechanisms 1 and 2, the results of the linear model are displayed in Figure 1, and the results of the logistic and Cox proportional hazards models are displayed in Figures S1–S2 of the Supplementary Materials. For Mechanism 3, the results are shown in Figures S3–S5 of the Supplementary Materials.

Figure 1.

Rejection Probabilities for the Continuous Phenotype Under the Null and Alternative Hypotheses for Mechanisms 1 and 2.

Under Mechanism 1, all methods have correct type I error. Under Model 1 and Mechanism 2, the simple imputation method has inflated type I error because the variance of the score statistic is underestimated. The complete-case analysis is also invalid except for the binary phenotype, but the type I error inflation is not as severe; the complete-case analysis for the binary phenotype has correct type I error because of the special structure of the logistic model (Prentice and Pyke 1979), Hu et al. (2015)’s variance estimator requires that both the actual and imputed S variables are independent of X, which does not hold under either Model 1 or Model 2. As a result, the variance is overestimated under Mechanism 2, which leads to type I error deflation. The remaining methods have consistent variance estimators and, therefore, have correct type I error. Under Model 2 and Mechanism 2, the score statistics of the complete-case analysis and the methods based on a model of S on linear terms of X are generally biased, giving rise to type I error inflation in most cases. Hu’s method exhibits type I error deflation under the logistic model because the bias of the score statistic is offset by the overestimation of the variance in this specific setting. (Because the absolute bias of the score statistic tends to infinity as n → ∞, Hu’s method would yield type I error inflation for large enough sample size.) The proposed imputation method is valid even though the imputation model is misspecified because the score statistic is unbiased. The full-model imputation method is also valid because the imputation model is correct. Note that the proposed imputation method and the full-model imputation method exhibit type I error deflation when the missing proportion is large. This is probably because the two methods involve a relatively large number of parameters, such that the normal approximations to the score statistics are inaccurate when the effective sample size is small.

The power of the complete-case analysis is generally low because it discards useful information. Under Model 1 or Mechanism 1, all valid methods that use the whole dataset have similar power. Under Model 2 and Mechanism 2, the full-model imputation method is the most powerful among the valid methods because a correct imputation model is assumed. However, this method cannot be used in practice because it requires knowledge of the true relationship between S and Z. The proposed imputation method is only slightly less powerful than the full-model imputation method. The bias of the score statistic of the other methods can lead to substantially low power.

Under Mechanism 3, the proposed imputation method preserves the type I error even though is misspecificd. The simple imputation method underestimates the variance of the score statistic and thus yields inflated type I error, whereas Hu’s method overestimates the variance and thys yields deflated type I error. For all phenotypes and models of S, the power of the proposed imputation method is similar to or higher than that of the other valid methods. Under Model 2 and the binary phenotype model, Lawless’ and Hu’s methods yield substantially lower power than the proposed imputation method due to the bias of the model-based score statistic. These results suggest that the proposed test is robust against misspecification of , so that strata with too few data points can be collapsed.

4. REAL DATA ANALYSIS

We analyzed a dataset of patients with serous ovarian cancer from TCGA (The Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network 2011). In the study, most subjects had available genomic data, including data on DNA copy number, somatic mutation, and levels of expression of mRNA measured by microarray platforms. Only a subset of subjects had enough tissue sample left for RNA sequencing, which was introduced after the study had begun. Demographic and clinical variables, including age at diagnosis, tumor stage, tumor grade, time to tumor progression, and time to death, were available for most subjects. The median followup time was about 2.5 years, and roughly 30% of the patients were lost to follow-up before tumor progression or death. The data are available at http://gdac.broadinstitute.org/.

We focused on testing the association between mRNA expression, measured by RNA sequencing, and progression-free survival time. We used the fragments per kilobase of transcript per million mapped reads values for the mRNA expression variable. The number of transcripts with RNA sequencing data was about 57,000. We considered a subset of 9,068 genes that were mutated in samples from more than five subjects. The number of subjects with available mutation, copy number, and clinical data was 407, approximately 30% of whom did not have RNA sequencing data.

We fit the Cox model for progression-free survival and included age, age squared, tumor stage, tumor grade, the interaction between age and (dichotomized) tumor stage, and the interaction between age and (dichotomized) tumor grade as covariates. Because the missing-data status is significantly associated with tumor stage (with a p-value of 4.83 × 10−6) but not with the other covariates, we set the stratification variable to be (dichotomized) tumor stage. The predictors in the imputation model of the RNA sequencing data included age, age squared, somatic mutation, copy number, and mRNA microarray expression; tumor stage and tumor grade were not included because their inclusion would render the estimation of the imputation model unstable. Microarray mRNA expression and somatic mutation were excluded from the imputation model if they were missing or too sparse. The B-spline functions were selected in the same way as in the simulation studies. For comparison, we performed the standard score test with only the complete cases and with the missing values imputed under a linear model. For further illustration, we performed the proposed test and the standard score test on the dataset with the missing proportion incr case d to 60%, where the RNA sequencing variables for subjects with inter-mediate survival or censoring time were treated as missing. The quantile-quantile plots are shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Quantile-Quantile Plots for the RNA-Seq Analysis of the TCGA Ovarian Cancer Data. The left plot shows the results for the original data, and the right plot shows the results with the missing proportion increcased to 60%. The p-values are truncated at 10−10.

For the original dataset, the p-values from the proposed method agree with the expectation that most gene expressions are not associated with progression-free survival. The complete-case analysis and the simple imputation method yielded excessive false-positive signals because the standard variance estimates of the score statistic are smaller than the empirical variance. With extra missing data, the inflation of type I error is more severe for the simple imputation method, whereas the type I error is preserved by the proposed method.

The top ten genes identified by the proposed method are presented in Table 1. Several of them have been previously known to be associated with ovarian cancer, with references given in Table 1. Among these genes, the associations between progression-free survival time and the expressions of all genes except SLC4A8 are more significant under the proposed method than under the complete-case analysis. The significance levels for the associations between progression-free survival time and the expressions of WDR91, SCEL, DUSP1, VMO1, PDLIM3, DCN, CNTN4, and MARK3 are lower under the simple imputation method than under the proposed method.

Table 1.

Top Genes in the RNA-Seq Analysis of the TCGA Ovarian Cancer Data.

| Gene | Proposed method |

Complete cases |

Simple imputation |

Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| WDR91 | 1.60E–05 | 3.20E–04 | 2.65E–05 | N/A |

| SLC4A8 | 1.06E–04 | 7.77E–05 | 1.08E–05 | N/A |

| SCEL | 3.82E–04 | 8.86E–04 | 6.29E–03 | N/A |

| DUSP1 | 6.73E–04 | 1.26E–03 | 2.63E–03 | Denkert et al. (2002) |

| VMO1 | 7.94E–04 | 9.06E–02 | 4.24E–03 | N/A |

| PDLIM3 | 9.25E–04 | 1.15E–02 | 3.19E–03 |

Mougeot et al. (2006) Bignotti et al. (2007) |

| PLAUR | 9.87E–04 | 5.38E–03 | 9.40E–04 | Arend et al. (2013) |

| DCN | 9.98E–04 | 1.67E–02 | 2.40E–03 | Sherman-Baust et al. (2003) |

| CNTN4 | 1.22E–03 | 1.22E–01 | 1.32E–02 | de Cristofaro et al. (2016) |

| MARK 3 | 1.38E–03 | 2.53E–03 | 3.80E–04 | N/A |

NOTE: The top 10 genes identified by the proposed method are given in the first column, and their p-values under the proposed method, the complete-case analysis, and the simple imputation method are given in the second to fourth columns. The references for studies that have identified an association between each gene and ovarian cancer, if available, are given in the last column. “N/A” means that no prior studies that identified such an association can be found.

5. DISCUSSION

In this paper, we propose a robust score test for the association between a phenotype and a genomic variable with partially missing values. The test is based on a semiparametric model for the genomic variable, where the semiparametric component ensures that under the null hypothesis, the score statistic with imputed values is unbiased for general missing-data mechanisms and arbitrary distributions of the genomic variable. Because each nonparametric function gl in the imputation model is a one-dimensional function of the covariates, the score test is computationally feasible with a large number of covariates provided that L is small. In addition to correcting for the bias of the score statistic, the semiparametric component results in a better fit of the imputation model, which leads to power gain even when data are missing completely at random. When the missing-data mechanism depends on the phenotype, the proposed test has correct type I error, whereas the standard score test is generally invalid. When the missing-data mechanism is independent of the phenotype, both the proposed and standard score tests have correct type I error, but the proposed test is asymptotically more powerful.

The validity of the proposed test follows from two special properties of the score statistic under the null hypothesis. First, the phenotype model does not involve the variable with missing values, and the score statistic derived under the full likelihood coincides with the imputation score statistic. Second, the score statistic is mean zero if the expectations of the actual and imputed values conditional on a low-dimensional function of the covariates are equal. As a result, single imputation yields a valid score statistic if the expectation of the variable with missing values conditional on the low-dimensional function of the covariates is correctly specified. These two properties do not hold under the alternative hypothesis, making parameter estimation with missing data a much more challenging problem than hypothesis testing. For estimation, single imputation generally yields underestimation of standard errors (Little 1992), and a correct specification of the missing-data model is required for valid inference.

Multiple imputation (Rubin 1987) is an alternative to single imputation. To perform multiple imputation, the distribution of S conditional on the observed data, including the phenotype, has to be correctly specificd. By contrast, correct specification of the distribution of S given a low-dimensional function of the covariate X is sufficient for the proposed test to be valid. Thus, multiple imputation requires much stronger assumptions than the proposed test. In fact, multiple imputation with the missing values imputed from the (correct) conditional distribution of S give X is invalid (Little 1992).

Our work can be extended in several directions. First, we have focused on a continuous genomic variable that is either exactly observed or missing. We may allow for a binary or categorical variable by incorporating the proposed semiparametric component into a generalized linear modeling framework. We may also consider genomic variables that are subject to censoring or detection limits, as in the case of metabolomics data (Yu et al. 2014). In this case, the conditional mean of the genomic variable cannot be consistently estimated using simple least-squares estimation, and additional assumptions on the distribution of the genomic variable are necessary.

Second, it would be of interest to perform a joint test for multiple genomic variables, where each variable may have a separate pattern of missing values. This extension can be applied to many existing testing procedures that involve a multivariate score statistic, such as the sequence kernel association test for rare variants (Wu et al. 2011), tests for meta analysis of sequencing data (Tang and Lin 2013), and the joint test for multiple genomic variables (Huang et al. 2014). Joint modeling of multiple variables with missing values is more challenging than modeling a single variable with missing value, when the pattern of the missing values for each variable do not overlap. Nevertheless, fitting a separate imputation model for each variable is not preferable, as it results in efficiency loss when the variables are correlated.

Finally, we have assumed that the missing-data mechanism depends only on the phenotype and a set of discrete covariates. The methodology can be extended to allow the missing-data mechanism to depend on continuous covariates by relating the variable with missing values to a nonparametric function of the phenotype and covariates. In addition, we may consider a missing-data mechanism that depends on a different phenotype; this scenario is common in the analysis of secondary phenotypes. In this case, the function through which the covariates affect the alternative phenotype must be estimated, and the variable with missing values should be modeled nonparametrically on that function.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the National Institutes of Health grants R01GM047845, R01HG009974, and P01CA142538.

APPENDIX

A.1. Proofs of Technical Results

In this section, we prove the two propositions and the two theorems put forth in the main text.

Proof of Proposition 1. The expected value of is

The second equality follows from the facts that Y is independent of Z conditional on X and that A(Y, X; ψ0) is a function of (Y, ). To derive the third equality, we note that R in the conditional expectation on the third line can be omitted, because R is independent of S, , and conditional on (Y, ). Thus, Y in the resulting conditional expectation can be omitted, because Y is independent of S, , and conditional on . We conclude that . □

Proof of Proposition 2. First, we establish the fact that R is independent of (S, Z) conditional on () when β = 0. To simplify the notation, for any sets of variables 𝑥 and 𝑦, we use f(𝑥 | 𝑦) to denote the conditional density function of 𝑥 given 𝑦 evaluated at (𝑥, 𝑦). The conditional joint density of (R, S, Z) given () is

where the first term on the fourth line follows from the conditional independence of R to S and Z (and subsequently ) given (Y, ), and the second term on the same line follows from the conditional independence of Y to S and Z (and subsequently ) given . The desired conditional independence follows.

Because S is independent of R conditional on (, ) under β = 0,

Therefore, (, ) satisfies . The mean of the imputed S is

The desired result follows from Proposition 1. □

Before proving Theorem 1, we present the following lemma, which pertains to the consistency of .

Lemma 1. Under conditions (C1)–(C4), , and for l = 1,…, L, where for any function h that has bounded first derivative, ∥h∥w1,∞ = ∥hℓ∞ + ∥h′∥ℓ∞, and .

Proof of Lemma 1. By Theorem 6.25 of Sehumaker (2007), there exists , such that and for each l = 1,… , L. Let . By the definition of and , ). By the concavity of φl,

where . Therefore,

| (A.1) |

Note that

where the first inequality follows because is bounded, and is some value between γ0 and . Likewise, because

for some c0 > 1,

Therefore, (A.1) implies that

| (A.2) |

By Theorem 2.6.15 of van der Vaart and Wellner (1996), referred to as VW hereafter, {} is a Vapnik-Chervonenkis (VC) class with VC index at most (Kn + q)2 + 2 for any M < ∞. By Theorem 2.6.7 of VW, we show that

for any 0 ≤ c1 ≤ 1, where N is the covering number, }, c2 is a constant, and F is an envelope function of that consists of second-order terms of (S, ). Therefore, the uniform entropy of the class of functions is . By Theorem 2.14.1 of VW and Markov’s inequality, the left-hand side of (A.2) is Op(Knn−1/2).

By the linear expansion of φl at , is equal to

where the first equality above follows because R and S are conditionally independent given and . Likewise,

We conclude that

Because , for some c3 > 0,

which implies that . Note that

Because , both and converge to zero in probability.

To establish the rate of convergence, we replace ε by 1 in (A.2). The left-hand side of the resulting inequality is op(n−1/2) because φl(gl, ; γ0) is Donsker in a neighborhood of . By the linear expansion on the right side,

The desired rate of convergence follows since . □

Proof of Theorem 1. The imputation score statistic is

| (A.3) |

The second equality above follows because the convergence rate of (, ) is at least n−1/4 and ℓβ(ψ, ξ; γ) is Donsker over a neighborhood of (ψ0, ξ*, γ0). By the linear expansion, the second term of (A.3) is equal to

up to an op(1) term. Let . Clearly, the first term of the above expression is by condition (C4). By condition (C5), hψ exists, and the second term of the above expression is equal to .

The third term of (A.3) is equal to

Let and be the score function for gl, and ηl, respectively. Let be the B-spline approximation of hg,l on the same grid as . By the definition of , and ,

Because and have bounded first derivatives and ℓg,l and ℓη,l are differentiable, ℓg,l(gl, ηl; β)[hg,l] and ℓη,l(gl, ηl; γ) are Donsker in a neighborhood of (, , γ0, hg,l). By the Donsker property of the ℓg,l and ℓη,l and the consistency results of Lemma 1,

Thus,

It is easy to see that hg,l and hη,l solve

| (A.4) |

for all has bounded fourth derivatives, . Therefore,

where . The desired result follows with . □

Proof of Theorem 2. Under condition (C5), , , , and are Glivenko-Cantelli classes over the space of (ψ, ξ, h1, h2). Thus, the variance estimator is consistent if () are consistent. The consistency of (, ) follows from Lemma 1 and condition (C4). A consistent estimator of hψ can be obtained by solving for all ψ. The estimator is obtained by solving the empirical version of (A.4) for the B-spline approximation of the function w. Specifically, for l = 1, … , L, such that and solve

for j = 1,…, Kn. By the Glivenko-Cantelli properties of the functions involved in the above equations and the consistency of and the B-spline approximations, . The asymptotic distribution of the test statistic follows from Slutsky’s theorem.

We show that the resulting projection is the same as that obtained by treating the B-spline terms as hxed covariates. Let and be matrices formed by stacking together for subjects with and , respectively, and let be a vector with elements A(Yi, Xi; ) for subjects with and Ri = 0. The estimators are

Let and Zl be the generic variable. The projection of the score statistic is equal to

which is the projection of the score of ξ with Zli treated as a set of fixed covariates. □

A.2. Explicit Forms of Variance Estimators

In this section, we formulate the variance estimators for the linear model, the logistic model, and the Cox proportional hazards model. Let Zi(γ) ≡ (Z1i(γ)T,…, ZLi(γ)T)T denote the vector of predictors of S, with Zi(γ) defined in the proof of Theorem 2. Let ξ denote the corresponding regression parameter and denote the least-squares estimator of ξ Let Z(γ) ≡ (Z1 (γ)T,…, ZL(γ)T)T be the generic version of Zi(γ). The robust imputation score statistic is

Let

where for l = 1,… L, the derivative B′ is defined component-wise, and 0q is a q-vector of zeros. First, we consider the linear and logistic models. For the linear model, we redefine A(Y, X; ψ) = Y − γT X, where the error variance is omitted because it only acts as a scaling factor. For the two models, there is no nuisance parameter ζ, and ψ = γ. Let

where A(1)(X; γ) = − X for the linear model, and A(1)(X; γ) = −eγTX/(1 + eγTX)2X for the logistic model. In the sequel, we may omit the arguments of the above functions. The variance estimator of is

where (, , ) is the sample mean of (ℓβ,i, , ℓξ,i), and (, , , , ) is the empirical version of (, Iξγ, Iξξ, , Iβξ).

For the Cox proportional hazards model, let

for r = 0, 1, and 2, where a⊗0 = 1, a⊗1 = a, and a⊗2 = aaT for any vector a. Partition with and and into , , , and . Let

where

The variance estimator of is

with (ψ, ξ) evaluated at (), where (, ) is the sample mean of (, ), and ( ) is the empirical version of ( ).

A.3. Bias of the Standard Variance Estimator

In this section, we evaluate the standard model-based variance estimator based on imputed data. Consider a generalized linear model with no nuisance parameter. The information matrix of (β, γ) under β = 0 is

where B(X; γ) = Var{A(Y, X; γ) | X}. The limit of the model-based variance estimator with the imputed data is equal to

where is equal to S if R = 1 and is equal to otherwise.

We derive the bias of the model-based variance estimator under a correct imputation model, i.e., , and a balanced sampling scheme of S, i.e., E{A(Y, X; γ0)R | X} = 0. Assume that . In this case, the imputation score statistic is

where the third equality follows from the rate of convergence of and the balanced sampling scheme. Therefore, the asymptotic variance of the imputation score statistic is

The bias of the model-based estimator is

| (A.5) |

Let υY, j(X) = Var{A(Y, X; γ) | R = j, X}, PR(X) = P(R =1 | X), υS(X) = E(S2 | X), and . The first term of (A.5) is . By the definition of B(X; γ0),

The second term of (A.5) is

To see that (A.5) is non-zero in general, consider the simple case of X = 1, vY,1 > υY,0, and , such that there is no covariate, the variance of the phenotype is larger among subjects with observed S, and the variance of the true S is larger than that of the imputed S. By Chebyshev’s sum inequality, the true variance is strictly larger than the limit of the model-based variance estimator . By contrast, if the missing-data mechanism does not depend on Y, then υY,1 and υY,0 are equal. As a result, (A.5) is equal to zero, and the model-based variance estimator is consistent.

A.4. Evaluation of Power

In this section, we evaluate the power of the imputation score test under the linear model: Y = γTX + βS + N(0,σ2). Assume the same imputation model for S as in Section A.2 with a general predictor Z(γ). Assume also that X is contained in Z(γ) and that , such that the score statistic is unbiased. The missing-data status can be expressed as , where for every fixed ω, Ω(ω) is a deterministic subset of the space of (Y, ), and ω is a random variable that is independent of (Y, Z(γ), S). Adopting the notation introduced in Section A.2, the score statistic can be expanded as , where , , and .

Under the contiguous alternative of βn = n−1/2b for some fixed b,

where . The first expectation on the far right side of the above expression is

The first term of the right side of the last equality is zero by assumption. Thus,

Simple algebraic manipulation yields . In addition,

Therefore, the asymptotic distribution of the score test statistic is non-central chi-square with non-centrality parameter

Because the conditional distribution of S given Z(γ0) may be misspecified, {S − ξ*TZ(γ0)} in ℓξ,i(γ0, ξ*) is generally dependent of Z(γ0). Thus, the non-centrality parameter is a function of high moments of Z(γ0), and it is difficult to evaluate the power for different choices of Z(γ0). Consider the case that S is missing completely at random. In this case, Iβγ = −E[{RS + (1 − R)ξ*T Z(γ0)}XT], and Iβξ = 0. The denominator of C is

where denotes the projection onto the orthogonal space of X, i.e., for any random variable T. The numerator of C is

where pR = P(R = 1), and the last equality follows from the definition of ξ* and the fact that X is contained in Z(γ0). As a result,

To show that the proposed test is more powerful than the imputation score test without stratification or the B-spline terms, we consider two sets of linear predictors and , where Z1(γ) is contained in Z2(γ), Let and be the imputed values of S using Z1(γ0) and Z2(γ0), respectively. The score test with in the imputation model is asymptotically more powerful if and only if

| (A.6) |

After some algebraic manipulation, the denominator on the left side of (A.6) can be expressed as

Compared to , is the projection of S onto a larger linear space. Thus,

and . It follows that (A.6) holds, and the test with a larger set of covariates in the imputation is more powerful.

Contributor Information

Kin Yau Wong, Email: kin-yau.wong@polyu.edu.hk, Department of Applied Mathematics, The Hong Kong Polytechnic University, Hong Kong.

Donglin Zeng, Email: dzeng@bios.unc.edu, Department of Biostatistics, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, NC 27599, USA.

D. Y. Lin, Email: lin@bios.unc.edu, Department of Biostatistics, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, NC 27599, USA.

REFERENCES

- Arend RC, Londoño-Joshi AI, Straughn JM, and Buchsbaum DJ (2013), “The Wnt/β-Catenin Pathway in Ovarian Cancer: A Review,” Gynecologic Oncology, 131, 772–779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Auer PL, Johnsen JM, Johnson AD, Logsdon BA, Lange LA, Nalls MA, Zhang G, Franceschini N, Fox K, Lange EM et al. (2012), “Imputation of Exome Sequence Variants Into Population-Based Samples and Blood-Cell-Trait-Associated Loci in African Americans: NHLBI GO Exome Sequencing Project,” The American Journal of Human Genetics, 91, 794–808, [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bignotti E, Tassi RA, Calza S, Ravaggi A, Bandiera E, Rossi E, Donzelli C, Pasinetti B, Pecorelli S, and Santin AD (2007), “Gene Expression Profile of Ovarian Serous Papillary Carcinomas: Identification of Metastasis-associated Genes,” American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology, 196, 245–el. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Boor C (1978), A Practical Guide to Splines, New York: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- de Cristofaro T, Di Palma T, Soriano AA, Monticelli A, Affinito O, Cocozza S, and Zannini M (2016), “Candidate Genes and Pathways Downstream of PAX8 Involved in Ovarian High-grade Serous Carcinoma,” Oncotarget, 7, 41929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denkert C, Schmitt WD, Berger S, Reles A, Pest S, Siegert A, Lichtenegger W, Dietel M, and Hauptmann S (2002), “Expression of Mitogen-activated Protein Kinase Phosphatase-1 (MKP-1) in Primary Human Ovarian Carcinoma,” International Journal of Cancer, 102, 507–513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derkach A, Lawless JF, and Sun L (2015), “Score Tests for Association Under Response-Dependent Sampling Designs for Expensive Covariates,” Biometrika, 102, 988–994. [Google Scholar]

- Hu YJ, Li Y, Auer PL, and Lin DY (2015), “Integrative Analysis of Sequencing and Array Genotype Data for Discovering Dis case Associations With Rare Mutations,” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 112, 1019–1024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang YT, VanderWeele TJ, and Lin X (2014), “Joint Analysis of SNP and Gene Expression Data in Genetic Association Studies of Complex Dis case s,” The Annals of Applied Statistics, 8, 352–376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim H, Golub GH, and Park H (2005), “Missing Value Estimation for DNA Microarray Gene Expression Data: Local Least Squares Imputation,” Bioinformatics, 21, 187–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawless J (2016), “Two-phase Outcome-Dependent Studies for Failure Times and Testing for Effects of Expensive Covariates,” Lifetime Data Analysis [online], DOI: 10.1007/s10985-016-9386-8. Available at https://link.springer.com/journal/10985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Willer CJ, Ding J, Scheet P, and Abecasis GR (2010), “MaCH: Using Sequence and Genotype Data to Estimate Haplotypes and Unobserved Genotypes,” Genetic Epidemiology, 34, 816–834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin DY, Zeng D, and Tang ZZ (2013), “Quantitative Trait Analysis in Sequencing Studies Under Trait-Dependent Sampling,” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 110, 12247–12252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Little RJ, (1992), “Regression With Missing X’s: A Review,” Journal of the American Statistical Association, 87, 1227–1237. [Google Scholar]

- Mougeot J-LC, Bahrani-Mostafavi Z, Vaehris JC, McKinney KQ, Gurlov S, Zhang J, Naumann RW, Higgins RV, and Hall JB, (2006), “Gene Expression Profiling of Ovarian Tissues for Determination of Molecular Pathways Reflective of Tumorigenesis,” Journal of molecular biology, 358, 310–329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prentice RL, and Pyke R (1979), “Logistic Dis case Incidence Models and Case-Control Studies,” Biometrika, 66, 403–411. [Google Scholar]

- Rubin DB (1987), Multiple Imputation for Nonresponse in Surveys, Wiley: New York. [Google Scholar]

- Schumaker L (2007), Spline Functions: Basic Theory, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sherman-Baust CA, Weeraratna AT, Rangel LB, Pizer ES, Cho KR, Schwartz DR, Shock T, and Morin PJ, (2003), “Remodeling of the Extracellular Matrix Through Overexpression of Collagen VI Contributes to Cisplatin Resistance in Ovarian Cancer Cells,” Cancer Cell, 3, 377–386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang ZZ, and Lin DY (2013), “MASS: Meta-Analysis of Score Statistics for Sequencing Studies,” Bioinformatics, 29, 1803–1805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network (2011), “Integrated Genomic Analyses of Ovarian Carcinoma,” Nature, 474, 609–615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torres-García W, Zhang W, Runger GC, Johnson RH, and Meldrum DR, (2009), “Integrative Analysis of Transcriptomic and Proteomic Data of Desulfovibrio Vulgaris: A Non-Linear Model to Predict Abundance of Undetected Proteins,” Bioinformatics, 25, 1905–1914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Vaart AW, and Wellner JA, (1996), Weak Convergence and Empirical Processes, New York: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Wu MC, Lee S, Cai T, Li Y, Boehnke M, and Lin X (2011), “Rare-variant Association Testing for Sequencing Data With the Sequence Kernel Association Test,” The American Journal of Human Genetics, 89, 82–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu B, Zheng Y, Alexander D, Morrison AC, Coresh J, and Boerwinkle E (2014), “Genetic Determinants Influencing Human Serum Metabolome Among African Americans,” PLoS Genetics, 10: e1004212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.